Abstract

Background:

Etrasimod is an oral, once-daily (QD), selective sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P)1,4,5 receptor modulator for the treatment of moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC). It is known that non-serious treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) may not lead to UC drug discontinuation but can affect treatment tolerability.

Objectives:

This post hoc analysis evaluated the incidence of specific, common, non-serious TEAEs reported in the etrasimod UC clinical programme and the characteristics of affected patients.

Design:

Data included patients from the Placebo-controlled UC cohort (phase II OASIS, and phase III ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 trials) receiving QD etrasimod (2 or 1 mg) or placebo.

Methods:

Proportions and incidence rates (IRs; the number of patients with a TEAE divided by the total exposure in patient-years (PYs), per 100 PY) of Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness TEAEs were reported. Changes in heart rate among patients with Dizziness TEAEs were also evaluated.

Results:

Among 943 patients (etrasimod 2 mg, N = 577 (276.7 PY); etrasimod 1 mg, N = 52 (11.4 PY); placebo, N = 314 (115.1 PY)), 48, 34, 27 and 21 patients experienced events of Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness, respectively. All events were non-serious; one patient treated with etrasimod was discontinued due to a Pyrexia TEAE. Numerically, IRs of Headache and Dizziness TEAEs were higher, and Nausea slightly higher, with etrasimod versus placebo (13.45 vs 8.63 per 100 PY, 6.52 vs 1.69 and 7.18 vs 5.13 per 100 PY, respectively); IRs were similar for Pyrexia. The duration of most TEAEs was 1–10 days.

Conclusion:

In the etrasimod UC clinical programme, all Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness events were non-serious. Headache and Dizziness were more frequent, and Nausea slightly more frequent, among patients receiving etrasimod versus placebo. The post hoc nature of this analysis is a limitation. These results reiterate the favourable safety profile and tolerability of etrasimod.

Trial registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02447302; NCT03945188; NCT03996369.

Keywords: adverse event; dizziness; etrasimod; headache; nausea; pyrexia, sphingosine 1-phosphate; ulcerative colitis

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, immune-mediated disease, characterised by inflammation of the colonic and rectal mucosa.1,2 The rapid development of novel treatment options for UC has highlighted the need to better understand their safety profiles and allow clinicians to perform accurate assessments of treatment risk/benefit profiles prior to treatment initiation.1,3 Serious adverse events (SAEs) associated with the use of a medical product, defined as serious undesirable experiences (e.g. resulting in hospitalisation, life-threatening events or death), 4 have been discussed in the context of UC therapies.5,6 However, non-SAEs (AEs that do not meet the criteria for SAEs) are generally under-reported across indications and therapeutic areas. 7 In patients with UC receiving long-term advanced targeted therapies, common non-SAEs include Arthralgia, Nausea, Nasopharyngitis and Headache.8–10 Although non-SAEs may not lead to immediate drug discontinuation, they can have an effect on patient quality of life and can considerably influence treatment adherence and tolerability, and the potential for AEs may impact patients’ decisions to begin therapy11,12; therefore, it remains important to communicate the incidence and characteristics of these events to fully inform on the overall safety profile of UC treatment.

Etrasimod is an oral, once-daily (OD), selective sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P)1,4,5 receptor modulator for the treatment of moderately to severely active UC. Treatment with etrasimod was demonstrated to be effective and well tolerated among patients with moderately to severely active UC in the 12-week, phase II OASIS induction trial (NCT02447302) 13 ; the 52-week, phase III ELEVATE UC 52 induction and maintenance trial (treat-through design; NCT03945188) and in the 12-week, phase III ELEVATE UC 12 induction trial (NCT03996369). 14 In the OASIS trial, 56.0% (28/50), 59.6% (31/52) and 50.0% (27/54) of patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD, 1 mg OD and placebo, respectively, reported experiencing any AEs. 13 Meanwhile, in ELEVATE UC 52, 71% (206/289) and 56% (81/144) of patients who received etrasimod 2 mg OD and placebo, respectively, reported any AEs, along with 47% for both etrasimod 2 mg OD and patients receiving placebo in ELEVATE UC 12 (etrasimod: 112/238; placebo: 54/116). 14 Headache, Nausea, Dizziness and Pyrexia were among the most frequently reported AEs occurring in ⩾3% of patients treated with etrasimod in ELEVATE UC 52 or ELEVATE UC 12; exposure-adjusted incidence rates (IRs) were mostly similar among patients receiving etrasimod compared with placebo. 14 Worsening of UC, Anaemia, COVID-19, Arthralgia and Abdominal pain were also experienced in ⩾3% of patients in the ELEVATE programme. 14 These are potentially UC-related and extraintestinal manifestation treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), or have been discussed elsewhere (COVID-19 is described in the publication assessing infection events), 15 and so were not the focus of this particular analysis.

This post hoc analysis aimed to further explore the safety profile of etrasimod by investigating the incidence and patient characteristics of specific TEAEs occurring at a frequency of ⩾3% throughout the etrasimod UC clinical programme, namely those of Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness.

Methods

Patients and study designs

In this study, data were analysed in two overlapping cohorts: the Pivotal UC cohort (comprising all patients from the phase III ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 trials) and the Placebo-controlled UC cohort (comprising the Pivotal UC cohort plus all patients from the phase II OASIS trial). The OASIS, ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 trials were randomised, multicentre, double-blind, Placebo-controlled studies. Full details of the patient populations and study designs for all three trials have been previously published.13,14

Briefly, ELEVATE UC 52 comprised a 12-week induction period followed by a 40-week maintenance period with a ‘treat-through’ design. OASIS and ELEVATE UC 12 comprised 12-week induction periods only. Adults with moderately to severely active UC (modified Mayo score (MMS) 4–9 with a centrally read endoscopic subscore ⩾2 and rectal bleeding subscore ⩾1) were eligible to participate in the etrasimod UC clinical programme.13,14 In the OASIS trial, patients aged 18–80 years were randomised 1:1:1 to receive etrasimod 2 mg OD, etrasimod 1 mg QD or placebo. 13 In ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12, patients aged 16–80 years were randomised 2:1 to receive etrasimod 2 mg OD or placebo. In both ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12, patients with a history of inadequate response, loss of response or intolerance to at least one therapy approved for UC treatment, and patients with isolated proctitis (<10 cm rectal involvement) were eligible to enrol (capped at 15% of total patients). Concomitant treatment with oral 5-aminosalicylates and/or oral corticosteroids was permitted, provided the dose was stable ⩾2 weeks immediately prior to randomisation or ⩾4 weeks prior to screening endoscopy assessment, respectively. Investigators were directed to taper corticosteroids in ELEVATE UC 52 after the week 12 assessment. 14

As reduction of heart rate is a known on-target effect of S1P receptor modulators, all patients received in-clinic cardiac monitoring on day 1; see Supplemental Materials for additional details of cardiac monitoring and criteria for cardiovascular-related discontinuation.

All studies were registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice or in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Review Board at each investigational centre participating in the studies. All patients provided written informed consent.

Safety analysis

In this post hoc analysis, the frequency, seriousness, onset and duration of Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness TEAEs were analysed in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort from day 1 to trial end. Additionally, the safety analysis set from the Pivotal UC cohort was used to analyse baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients with these TEAEs.

Selected non-serious TEAEs which were among those with a frequency of ⩾3% were assessed. Non-serious TEAEs were defined as TEAEs that did not meet the criteria for SAEs (defined as an AE that was life-threatening, required inpatient hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation, or resulted in a persistent or significant disability/incapacity, a congenital anomaly/birth defect, death or was otherwise medically significant) and that occurred at any time after the first dose of study treatment.

Management and determination of the severity of TEAEs was the responsibility of the investigator and based on their clinical judgement. Occasional use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, acetaminophen and aspirin ⩽325 mg OD, was permitted. Severity was graded according to the Common Terminology for Adverse Events, version 5.0. Grade 1 TEAEs were mild in severity, with no or mild symptoms and no intervention required; Grade 2 TEAEs were moderate in severity, requiring minimal, local or non-invasive intervention; Grade 3 TEAEs were severe or medically significant but not immediately life-threatening; Grade 4 TEAEs had life-threatening consequences and Grade 5 TEAEs led to death.

Study investigators used their clinical judgement to determine causal relationships between TEAEs and the study treatment, and considered alternative causes including underlying disease, concomitant conditions and therapies, other risk factors and the time of onset in comparison to treatment administration.

TEAEs were classified as ‘ongoing’ if they were unresolved at the trial end. For TEAEs that were not resolved by the end of the study, study investigators used their clinical judgement to determine whether these events were improving (labelled as recovering/resolving) or not. TEAE-preferred terms included in this analysis were coded based on the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 24.1.

The International Classification of Headache Disorders classifies headaches into three categories: primary, secondary and neuropathies and facial pains. 16 All Headache events included in this analysis (based on the preferred term of ‘Headache’) met the criteria for primary headache, defined as a headache or headache disorder, not caused by or attributed to another disorder. The preferred term of ‘Migraine’ was not assessed as part of this analysis.

Statistical analysis

The total number, proportions and IRs of select TEAEs were evaluated. IRs were calculated as the number of patients with a TEAE divided by the total exposure in patient-years (PY) (sum of the individual time to first TEAE occurrence, or time in the study if the patient was event-free). PY was calculated as the sum of time to event for patients with events and censored time at-risk period for patients without events. IRs are reported as the number of unique patients with events per 100 PY with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) constructed assuming normal approximation to the Poisson count variable, except for the exploratory analysis of baseline characteristics, which were reported per 1 PY. Non-overlapping 95% CIs were interpreted as a difference in TEAE IR between treatment groups. Patients with multiple occurrences of the same event were counted only once for proportions and IR analyses; all individual occurrences of events were included in the reporting of onset and duration.

Results

Among the 943 patients in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort, 577 patients received etrasimod 2 mg OD with 276.7 PY of follow-up, 52 patients received etrasimod 1 mg QD with 11.4 PY of follow-up and 314 patients received placebo with 115.1 PY of follow-up. Additionally, of 787 patients included in the Pivotal UC cohort, 527 received etrasimod 2 mg OD with 265.6 PY of follow-up and 260 received placebo with 103.0 PY of follow-up. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients in the Placebo-controlled UC and Pivotal UC cohorts are shown in Table 1. Patient characteristics were generally comparable across treatment groups and cohorts.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients in the Placebo-controlled UC and Pivotal UC cohorts.

| Baseline demographic/clinical characteristic | Placebo-controlled UC cohort a | Pivotal UC cohort b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo OD (N = 314) | Etrasimod 2 mg OD (N = 577) | Etrasimod 1 mg OD (N = 52) | Etrasimod (combined; N = 629) | Placebo OD (N = 260) | Etrasimod 2 mg OD (N = 527) | |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 40.5 (14.0) | 40.8 (13.6) | 43.2 (12.2) | 41.0 (13.5) | 39.6 (13.7) | 40.8 (13.8) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 121 (38.5) | 263 (45.6) | 22 (42.3) | 285 (45.3) | 99 (38.1) | 240 (45.5) |

| Extent of disease, n (%) c | ||||||

| Pancolitis | 111 (35.4) | 184 (31.9) | 20 (38.5) | 204 (32.4) | 88 (33.8) | 170 (32.3) |

| Left-sided colitis/proctosigmoiditis | 179 (57.0) | 339 (58.8) | 23 (44.2) | 362 (57.6) | 153 (58.8) | 318 (60.3) |

| Proctitis | 18 (5.7) | 37 (6.4) | 0 | 37 (5.9) | 18 (6.9) | 37 (7.0) |

| Baseline MMS 4–6, n (%) | 131 (41.7) | 242 (41.9) | 21 (40.4) | 263 (41.8) | 110 (42.3) | 222 (42.1) |

| Baseline MMS 7–9, n (%) | 180 (57.3) | 335 (58.1) | 31 (59.6) | 366 (58.2) | 150 (57.7) | 305 (57.9) |

| Mean duration of UC, years (SD) | 7.1 (6.6) | 7.3 (7.2) | 7.1 (6.2) | 7.3 (7.1) | 6.8 (6.4) | 7.4 (7.4) |

| Baseline CS use, n (%) | 94 (29.9) | 176 (30.5) | 13 (25.0) | 189 (30.0) | 76 (29.2) | 158 (30.0) |

| Prior biologic or JAKi exposure, n (%) | 83 (26.4) | 162 (28.1) | 0 | 162 (25.8) | 83 (31.9) | 162 (30.7) |

The Placebo-controlled UC cohort comprised the Pivotal UC cohort plus all patients from the phase II OASIS trial.

The Pivotal UC cohort comprised all patients from the phase III ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 trials.

Extent of disease at baseline was recorded by investigators on the clinical report form.

CS, corticosteroid; JAKi, JAK inhibitor; MMS, modified Mayo score; n, number of patients with characteristic; N, number of patients in the group; OD, once daily; SD, standard deviation; UC, ulcerative colitis.

No Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea or Dizziness TEAEs met the criteria for SAEs. Proportions and IRs and 95% CI per 100 PY of Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness TEAEs by preferred term in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort and Pivotal UC cohort.

| Preferred term, n (%) (IR; 95% CI per 100 PY) | Placebo-controlled UC cohort | Pivotal UC cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo OD (N = 314) | Etrasimod 2 mg OD (N = 577) | Etrasimod 1 mg OD (N = 52) | Etrasimod (combined; N = 629) | Placebo OD (N = 260) | Etrasimod 2 mg OD (N = 527) | |

| Headache | 10 (3.2) [8.63; 3.28, 13.97] | 38 (6.6) [14.05; 9.58, 18.52] | 0 | 38 (6.0) [13.45; 9.17, 17.73] | 9 (3.5) [8.68; 3.01, 14.36] |

35 (6.6) [13.50; 9.03, 17.98] |

| Pyrexia | 10 (3.2) [8.57; 3.26, 13.88] | 24 (4.2) [8.56; 5.14, 11.99] | 0 | 24 (3.8) [8.21; 4.92, 11.49] | 9 (3.5) [8.62; 2.99, 14.25] |

22 (4.2) [8.19; 4.77, 11.61] |

| Nausea | 6 (1.9) [5.13; 1.03, 9.24] | 20 (3.5) [7.12; 4.00, 10.25] | 1 (1.9) [8.48; 0.00, 25.10] | 21 (3.3) [7.18; 4.11, 10.25] | 4 (1.5) [3.81; 0.08, 7.55] |

19 (3.6) [7.06; 3.89, 10.24] |

| Dizziness | 2 (0.6) [1.69; 0.00, 4.03] | 18 (3.1) [6.44; 3.47, 9.42] | 1 (1.9) [8.38; 0.00, 24.82] | 19 (3.0) [6.52; 3.59, 9.46] | 1 (0.4) [0.94; 0.00, 2.79] |

18 (3.4) [6.73; 3.62, 9.84] |

For TEAEs with 0 patients with events, % and IR are also 0, and 95% CIs were not calculated, so not displayed.

CI, confidence interval; IR, incidence rate; N, total number of patients in the safety analysis set; n, number of patients with each TEAE; PY, patient-year; OD, once daily; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; UC, ulcerative colitis.

TEAEs of Arthralgia and Abdominal pain were experienced by 1.9%–3.3% and 2.4%–3.8% of patients, respectively, across treatment groups (Supplemental Table 1). However, given that these TEAEs may have been UC related, they were not explored further in this analysis. Further TEAEs experienced at a frequency of ⩾2% are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

In the Placebo-controlled UC cohort, the proportion of patients discontinuing study treatment due to any TEAE was low and generally similar across the three studies included. In OASIS, 3/50 (6.0%), 4/52 (7.7%) and 0 patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD, etrasimod 1 mg OD and placebo, respectively, discontinued study treatment due to TEAEs. In ELEVATE UC 52, 12/289 (4.2%) and 7/144 (4.9%) patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD and placebo, respectively, discontinued treatment; in ELEVATE UC 12, 13/238 (5.5%) and 1/116 (0.9%) patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD and placebo, respectively, discontinued treatment due to TEAEs.

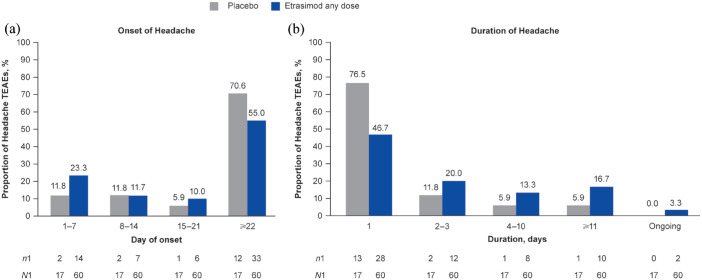

Headache

In the Placebo-controlled UC cohort, proportion and IRs of patients with Headache TEAEs were higher in patients receiving etrasimod (60 events in 38/629 patients (6.0%; etrasimod 2 mg OD, n/N = 38/577; etrasimod 1 mg OD, n/N = 0/52); age range, 16–72 years; IR, 13.45; all 2 mg OD) versus placebo (17 events in 10/314 patients (3.2%); age range, 17–52 years; IR, 8.63; Table 2). All Headache TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity and non-serious; no patients discontinued due to Headache TEAEs. Of the 77 Headache TEAEs in total, 55/60 (91.7%) in the etrasimod group and 16/17 (94.1%) in the placebo group were deemed to be not related to study treatment by the site investigator. By treatment group, the majority of Headache TEAEs occurred on or after day 22 in patients receiving etrasimod (33/60 (55.0%)) and placebo (12/17 (70.6%); Figure 1). Headache TEAEs were short in duration in both the etrasimod and placebo groups, with a median duration of 2.0 days (range, 1–195; mean 14.2 days, standard deviation (SD) 34.22) and 1.0 day (range, 1–74; mean 5.8 days, SD 17.64). Given that the minimum recordable duration for TEAEs was 1 day, ‘short’ was deemed a fair description of Headache TEAEs with median durations of 1 and 2 days. Among patients receiving etrasimod, 28/60 cases (46.7%) resolved within 1 day, 12/60 (20.0%) resolved within 2–3 days and 10/60 (16.7%) lasted ⩾11 days (Figure 1). Among patients receiving placebo, 13/17 cases (76.5%) resolved within 1 day, 2/17 (11.8%) within 2–3 days and 1/17 (5.9%) lasted ⩾11 days (Figure 1). Two cases (3.3%) were ongoing by the trial end (both patients receiving etrasimod); one patient’s Headache TEAE began on day 28 of ELEVATE UC 52 and the other patient’s on day 1 of ELEVATE UC 52. Both were mild in severity and determined as not related to the study treatment by the investigator. One case of non-resolved Headache was experienced as intermittent headaches.

Figure 1.

(a) Onset and (b) duration of Headache TEAEs in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort.

n1, number of events per timepoint; N1, total number of events by treatment group; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; UC, ulcerative colitis.

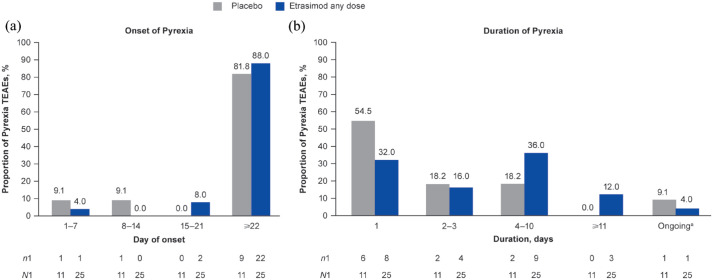

Pyrexia

Overall, 24/629 patients receiving etrasimod (3.8%; age range 18–72 years; all 2 mg OD (N = 577)) experienced 25 Pyrexia TEAEs (IR, 8.21) and 10/314 patients receiving placebo (3.2%; age range 22–67 years) experienced 11 Pyrexia TEAEs (IR, 8.57) in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort (Table 2). Pyrexia TEAEs had similar IRs in patients receiving etrasimod and placebo (Table 2); additionally, all were mild or moderate in severity and non-serious. One female patient, aged 18 years, experienced a Grade 1 (mild) Pyrexia event on day 20 of etrasimod treatment, along with abdominal pain, moderate constipation, vomiting and Pyrexia, which was assessed by the investigator to be probably related to treatment and led to treatment discontinuation and trial withdrawal; early termination visits were not completed, and the outcome of the patient’s Pyrexia was unknown. No other patients permanently discontinued treatment due to Pyrexia TEAEs. Out of 36 Pyrexia TEAEs, 24/25 (96.0%) for etrasimod and 10/11 (90.9%) for placebo were deemed not to be related to the study treatment by the site investigator. By treatment group, 22/25 Pyrexia TEAEs (88.0%) in patients receiving etrasimod and 9/11 (81.8%) in patients receiving placebo occurred on or after day 22 (Figure 2). All Pyrexia TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity with most lasting 1–10 days (etrasimod, 21/25 (84.0%); placebo, 10/11 (90.9%)), with a median duration of 3.5 days (range, 1–40; mean 5.9 days, SD 8.15) for patients receiving etrasimod and 1.0 days (range, 1–4; mean 1.8 days, SD 1.23) for patients receiving placebo. Three cases of Pyrexia occurred at the same or similar time as a UC flare. One Pyrexia TEAE in a patient receiving placebo (reported as intermittent and not related to study treatment) was described as ongoing at trial end, having begun on day 57 of ELEVATE UC 52 (Figure 2). The Pyrexia TEAE described above in one patient receiving etrasimod who discontinued without follow-up was ongoing at the time of discontinuation.

Figure 2.

(a) Onset and (b) duration of Pyrexia TEAEs in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort.

a‘Ongoing’ included patients whose TEAE outcomes were unknown.

n1, number of events per timepoint; N1, total number of AEs by treatment group; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; UC, ulcerative colitis.

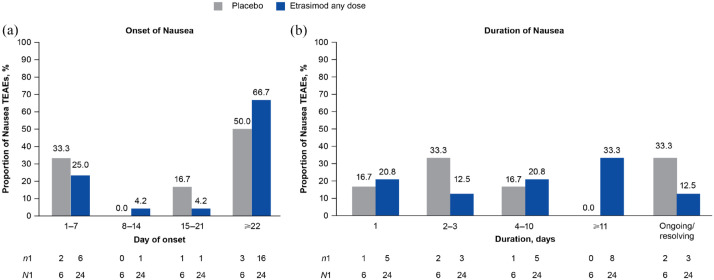

Nausea

A total of 21/629 patients receiving etrasimod (3.3%; age range 21–53 years) experienced 24 Nausea TEAEs (IR, 7.18; etrasimod 2 mg OD, n/N = 20/577; etrasimod 1 mg OD, n/N = 1/52) and 6/314 patients receiving placebo (1.9%; age range 23–51 years) experienced 6 Nausea TEAEs (IR, 5.13) in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort, respectively (Table 2). Nausea TEAEs had slightly numerically higher IRs in patients receiving etrasimod versus placebo (Table 2). All Nausea TEAEs were non-serious and all but one were mild or moderate in severity. One patient experienced a severe Nausea TEAE, which resolved by the trial end; no patients discontinued due to Nausea TEAEs. Of the 30 Nausea TEAEs in total, 17/24 (70.8%) among patients receiving etrasimod and 5/6 (83.3%) among patients receiving placebo were considered to be unrelated to the study treatment by the site investigator. By treatment group, 16/24 (66.7%) Nausea TEAEs among patients receiving etrasimod and 3/6 (50.0%) among patients receiving placebo occurred on or after day 22 (Figure 3). Most Nausea TEAEs (etrasimod, 13/24 (54.2%); placebo, 4/6 (66.7%)) were 1–10 days in duration; the median duration was 5.0 days (range, 1–98; mean 17.7 days, SD 27.46) for patients receiving etrasimod and 2.5 days (range 1–4; mean 2.5 days, SD 1.29) for patients receiving placebo. However, three mild to moderate Nausea TEAEs among patients treated with etrasimod (12.5%) were ongoing at trial end. Two (8.3%), which began on day 45 of ELEVATE UC 52 and day 76 of ELEVATE UC 12, were classified as not recovered/not resolved and one (4.2%), which began on day 82 of ELEVATE UC 52, was classified as ongoing (Figure 3). Among patients receiving placebo, one (16.7%) Nausea TEAE which began on day 114 of ELEVATE UC 52 was ongoing, and one (16.7%) case which began on day 54 of ELEVATE UC 52 was recovering/resolving.

Figure 3.

(a) Onset and (b) duration of Nausea TEAEs in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort.

n1, number of events per timepoint; N1, total number of events by treatment group; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; UC, ulcerative colitis.

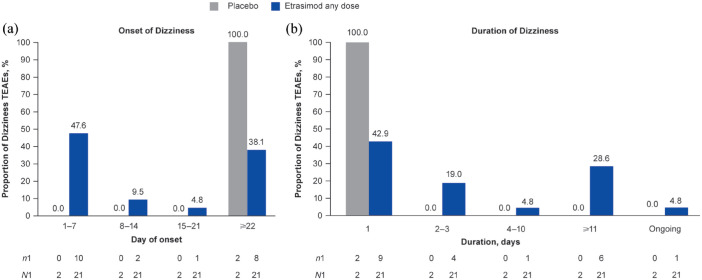

Dizziness

In the Placebo-controlled UC cohort, 19/629 patients receiving etrasimod (3.0%; age range 23–67 years) experienced 21 TEAEs of Dizziness (IR, 6.52; etrasimod 2 mg OD, n/N = 18/577; etrasimod 1 mg OD, n/N = 1/52) and 2/314 patients receiving placebo (0.6%; age range 29–35 years) experienced 2 TEAEs of Dizziness (IR, 1.69; Table 2). All Dizziness TEAEs were mild or moderate in severity, non-serious and none led to study treatment discontinuation. One 38-year-old female patient receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD had a dose interruption following a mild Dizziness TEAE on day 1, described as light-headedness (event resolved the same day); treatment was interrupted on day 2 and resumed on day 3. The patient withdrew from the trial after day 4. Of the total 23 Dizziness TEAEs, 8/21 (38.1%) in the etrasimod group and 1/2 (50.0%) in the placebo group were deemed not to be related to the study treatment by the site investigator.

Of the 21 Dizziness TEAEs among patients receiving etrasimod, 10/21 (47.6%; all receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD) occurred on days 1–7, 2/21 (9.5%) occurred on days 8–14, 1/21 (4.8%) occurred on days 15–21 and 8/21 (38.1%) occurred on or after day 22 (Figure 4). Furthermore, 9/21 (42.9%) Dizziness TEAEs were 1 day in duration in patients receiving etrasimod. Of the two Dizziness TEAEs among patients receiving placebo, one (50%) occurred on day 48 and one (50%) occurred on day 106. The median duration of Dizziness TEAEs was 2.0 days (range 1–132; mean 18.1, SD 34.39) for patients receiving etrasimod and one day (range 1–1; mean 1.0, SD 0.00) for patients receiving placebo. However, 1/21 (4.8%) Dizziness TEAE among patients receiving etrasimod that began on day 1 of ELEVATE UC 52 (deemed not related to treatment) was ongoing at the time of the patient’s last trial visit at day 98 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

(a) Onset and (b) duration of Dizziness TEAEs in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort.

n1, number of events per timepoint; N1, total number of events by treatment group; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; UC, ulcerative colitis.

There were two Dizziness TEAEs in patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD (one each in ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12) that occurred concurrently with Bradycardia TEAEs; etrasimod was discontinued due to Bradycardia events in both patients (see Supplemental Materials for corresponding patient narratives).

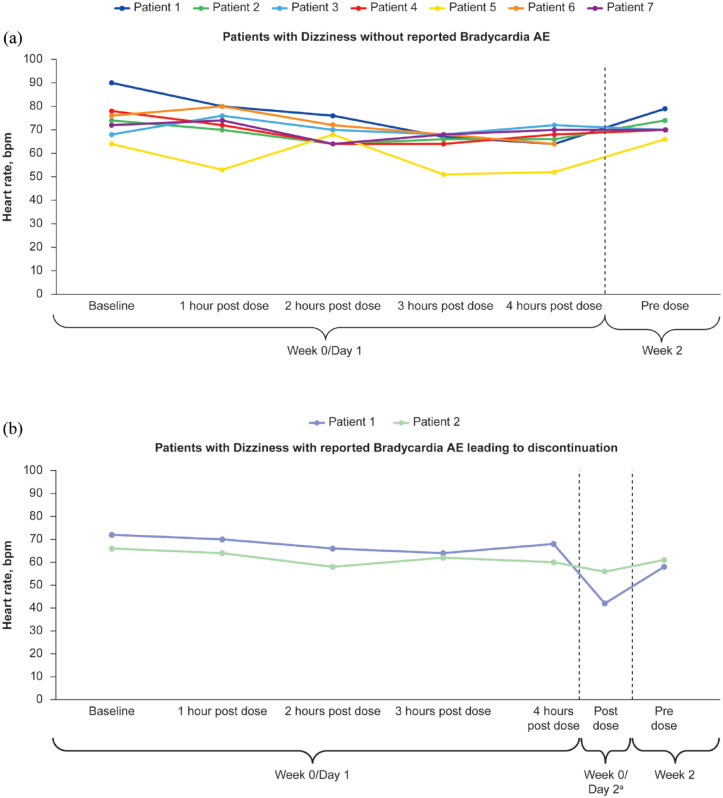

Change in heart rate over time in patients with Dizziness on days 1–3

When assessing whether Dizziness TEAEs were related to first-dose heart rate changes among the nine patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD who experienced Dizziness TEAEs on days 1–3, day 1 changes from baseline in heart rate ranged from −26 to 8 bpm. This was similar to changes in heart rate observed for the 10 patients receiving etrasimod with a later onset of Dizziness (onset day 3 to day 276, range: −27 to 5 bpm). Looking at the individual trial populations, among all patients receiving etrasimod enrolled in the ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 trials, changes from baseline in heart rate on day 1 (measured hourly at 1–13 and 1–8 h post-dose in ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12, respectively) ranged from −53 to 19 bpm (etrasimod 2 mg OD group in ELEVATE UC 52) and −51 to 28 bpm (etrasimod 2 mg QD group in ELEVATE UC 12), whereas among all patients receiving etrasimod enrolled in OASIS, mean changes from baseline in heart rate on day 1 (measured hourly at 1–8 h post-dose) ranged from −9.4 to −5.5 (etrasimod 2 mg QD) and −8.0 to −3.9 (etrasimod 1 mg QD). In the Placebo-controlled UC cohort, decreases in heart rate (mean −8.4 bpm from baseline on day 1) were similar in patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD who experienced Dizziness on days 1–3 compared with those with later onset of Dizziness (Dizziness on days 1–3, range: −26 to 8 bpm; Dizziness after day 3 to day 276, range: −27 to 5 bpm). Among patients receiving etrasimod who experienced Dizziness on days 1–3, there was no apparent relationship between this TEAE and change in heart rate, regardless of whether the patient discontinued study treatment due to Bradycardia (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Change in heart rate from baseline to week 2 in patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD with Dizziness TEAEs on days 1–3 (a) without Bradycardia and (b) following discontinuation due to Bradycardia in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort.

aFor patient 1, post-dose timing of day 2 measurements was unknown. Day 2 measurements shown are the last measurements available from that day.

bpm, beats per minute; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Among patients who received etrasimod and experienced Dizziness on day 1, there were no reports of either hypertension or hypotension. Furthermore, no events of clinical consequence associated with Dizziness/Bradycardia, such as syncope, loss of consciousness or fall were reported. Concurrent TEAEs (including general weakness, drowsiness, Headaches and Pyrexia) at the time of Dizziness were reported in 7/9 (77.8%) patients with onset of Dizziness on days 1–3.

Baseline demographics, clinical characteristics and their relationship with TEAEs

Exploratory analysis of patients who experienced Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness TEAEs in the Pivotal UC cohort (ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 only), stratified by baseline demographics and clinical characteristics, is shown in Supplemental Table 2. Among patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg OD, those with baseline pancolitis had numerically higher IRs of Dizziness and Nausea than patients with baseline left-sided colitis/proctosigmoiditis; however, the highest IR was for Pyrexia among patients with baseline proctitis, compared with those with baseline pancolitis and those with baseline left-sided colitis/proctosigmoiditis. Furthermore, excluding Headache TEAEs in patients receiving placebo, patients with baseline MMS 7–9 had a numerically higher IR for the Headache and Dizziness TEAEs versus those with baseline MMS 4–6, regardless of treatment received.

Discussion

This post hoc analysis characterised and assessed the frequency and extent of selected commonly occurring TEAEs of Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness in patients receiving etrasimod 2 or 1 mg OD or placebo in the phase II and III trials within the etrasimod UC clinical programme. This analysis provides important context on the onset and duration of TEAEs that are most likely to be experienced by patients treated with etrasimod. All TEAEs reported here were mild or moderate in severity, non-serious and most were not related to study treatment; ⩾50% of TEAEs occurred after day 22 across treatment groups, with the exception of Dizziness in patients receiving etrasimod, among whom approximately 50% of TEAEs occurred on days 1–7. Numerically, Headache and Dizziness TEAEs were more frequent, and Nausea TEAEs were slightly more frequent, among patients receiving etrasimod versus placebo. However, 95% CIs were overlapping for the etrasimod and placebo groups for all four TEAEs, with the exception of Dizziness in the Pivotal UC cohort. Although each TEAE assessed occurred in a slightly greater proportion of patients receiving etrasimod 2 versus 1 mg OD, the low number of patients who received etrasimod 1 mg OD and events overall make meaningful comparisons between these treatment groups difficult. Despite experiencing TEAEs, most patients continued taking their study treatment. Although duration varied, most TEAEs lasted less than 2 weeks. Most patients did not discontinue study treatment due to these TEAEs, except one patient receiving etrasimod 2 mg QD with Grade 1 Pyrexia accompanied by gastrointestinal disorders and vomiting. Some cases were considered ongoing at the trial end; however, several of these patients entered into the open-label extension trial, suggesting patient tolerance of these TEAEs.

In this analysis, patients in the Placebo-controlled UC cohort who received any dose of etrasimod demonstrated mostly similar IRs for Pyrexia when compared with placebo. However, numerically, IRs for Headache and Dizziness were higher, and slightly higher for Nausea, in patients receiving any dose of etrasimod versus placebo. It should be noted that the presence of both Pyrexia and Nausea may be affected by several factors, such as the underlying UC disease process.1,17 Furthermore, many cases of Pyrexia during these studies occurred with concomitant infection or vaccine, and so were not attributed to study treatment. The observation that Headache TEAEs were numerically more frequent among those receiving etrasimod than placebo was consistent with previous randomised controlled trials of other advanced UC therapies in patients with UC (vedolizumab: 12.9% vs placebo: 10.2%). 18 This was not unexpected since many drugs with different mechanisms of action are known to induce headaches. 19 Similarly, dizziness has also been frequently reported among patients receiving advanced therapies such as infliximab, with approximately 10% of infusions associated with mild reactions including Dizziness. 20 It is also noteworthy that the ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 trials took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have impacted the frequency and occurrence of any of the described TEAEs.

Headache, pyrexia, bradycardia and dizziness are adverse drug reactions which have been reported with first-generation S1P receptor modulators (ponesimod 20 mg OD: headache 11.5%, pyrexia 2%, bradycardia 0.7%, dizziness 5%; fingolimod 0.5 mg OD: headache 12.4%, bradycardia 0.3%; ozanimod 0.92 mg OD: headache 11.5%, bradycardia 0.8%).21–24 However, the increased selectivity of novel treatments in this drug class has demonstrated promising results in limiting the range of TEAEs that were initially experienced with first-generation drugs.14,25 For example, while patients who experience bradycardia may have accompanying symptoms such as syncope and dizziness, 26 here, only 2 of the 19 patients who reported Dizziness discontinued their treatment due to Bradycardia. Furthermore, Dizziness event onset occurred at various times after patients received their first dose, and no relationship was found between Dizziness and first-dose heart rate change. This suggests that most Dizziness TEAEs reported in the OASIS and ELEVATE trials were not related to Bradycardia. Of the remaining Dizziness TEAEs, most were treatment related, as assessed by the investigator; however, none were serious or led to study treatment discontinuation and most experienced by those receiving etrasimod (42.9%) resolved within 1 day. Additionally, patients who presented with Dizziness on days 1–3 had similar changes in heart rate when compared with those who experienced Dizziness from day 3 to trial end. Finally, changes in heart rate among patients with Dizziness were generally similar to the overall study population in ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 and consistent with the known effects of S1P receptor modulators.27–29 These results contribute to evidence from the etrasimod UC clinical programme which supports the use of etrasimod 2 mg OD from day 1 in patients with UC, and provides evidence that etrasimod treatment can be initiated without the need for dose titration.

There are some limitations that should be noted in this analysis, including its post hoc nature, which introduces the risk of bias through selective reporting. Moreover, the low number of patients who received etrasimod 1 mg OD and the low number of events in some patient subgroups make it difficult to draw any conclusion on the dose effect. Statistical comparison was not performed for this analysis as the low event numbers did not allow for detecting meaningful differences. Comparative analysis with statistical significance levels may add weight to these findings. The select TEAEs reported here may have different aetiologies and potential correlation with etrasimod treatment should be interpreted with caution, given that assessment of TEAEs was primarily clinician dependent and also dependent on reporting by patients; TEAEs may therefore have been subject to recall bias by patients. In addition, symptoms such as nausea, vomiting and pyrexia may be symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease, including UC, 30 rather than related to treatment, while symptoms such as headache and dizziness are associated with S1P receptor modulators in general.27–29 Ongoing or resolving TEAEs were classified as such at the next visit, whereas TEAEs that resolved but then reappeared at a later visit were counted separately. Finally, patients included in the analysis met the ELEVATE clinical programme inclusion criteria and may not represent the overall UC population.

In conclusion, the findings from this post hoc analysis suggest that, despite occurring commonly in the ELEVATE UC trials, TEAEs of Headache, Pyrexia, Nausea and Dizziness were mild or moderate in severity, and resulted in only a small number of discontinuations. Moreover, TEAEs of Dizziness were generally not indicative of potentially more serious TEAEs such as Bradycardia. The results of this analysis expand on the current understanding of the safety and tolerability of etrasimod, as well as further characterising select TEAEs frequently reported in the etrasimod UC programme. These findings will aid in informing clinician and patient treatment decisions for patients with UC.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tag-10.1177_17562848241293643 for Non-serious adverse events in patients with ulcerative colitis receiving etrasimod: an analysis of the phase II OASIS and phase III ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 clinical trials by Charlie W. Lees, Joana Torres, Yvette Leung, Séverine Vermeire, Marc Fellmann, Irene Modesto, Aoibhinn McDonnell, Krisztina Lazin, Michael Keating, Martina Goetsch, Joseph Wu and Edward V. Loftus in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients, investigators and study teams who were involved in the etrasimod UC programme. The authors also wish to thank Natalie Springveld for her contributions to this manuscript. Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Chimwemwe Chibambo, MBChB, and Karen Thompson, PhD, CMC Connect, a division of IPG Health Medical Communications and was funded by Pfizer, New York, NY, USA, in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP 2022) guidelines (Ann Intern Med 2022; 175: 1298–1304).

Footnotes

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Charlie W. Lees, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK Edinburgh IBD Unit, Western General Hospital, NHS Lothian, Edinburgh, UK.

Joana Torres, Division of Gastroenterology, Hospital Beatriz Ângelo, Loures, Portugal; Division of Gastroenterology, Hospital da Luz, Lisbon, Portugal; Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisbon, Portugal.

Yvette Leung, Department of Medicine, Department of Gastroenterology, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Séverine Vermeire, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University Hospitals Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Marc Fellmann, Pfizer Switzerland AG, Schärenmoosstrasse 99, 8052 Zürich, Switzerland.

Irene Modesto, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA.

Aoibhinn McDonnell, Pfizer Ltd, Sandwich, UK.

Krisztina Lazin, Pfizer AG, Zürich, Switzerland.

Michael Keating, Pfizer Inc., New York, NY, USA.

Martina Goetsch, Pfizer AG, Zürich, Switzerland.

Joseph Wu, Pfizer Inc., Cambridge, MA, USA.

Edward V. Loftus, Jr, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine and Science, Rochester, MN, USA.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: All studies were registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, were conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice or in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Institutional Review Board at each investigational centre participating in the studies. All patients provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Charlie W. Lees: Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Joana Torres: Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Yvette Leung: Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Séverine Vermeire: Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Marc Fellmann: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Data analysis; Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Irene Modesto: Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Aoibhinn McDonnell: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Data analysis; Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Krisztina Lazin: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Data analysis; Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Michael Keating: Conceptualisation; Data acquisition; Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Martina Goetsch: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Data analysis; Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Joseph Wu: Formal analysis; Data analysis; Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Edward V. Loftus: Investigation; Interpretation of data; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article: These studies were sponsored by Pfizer Inc.

C.W.L. has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Dr Falk, Ferring, Hospira, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer Inc., Shire, Takeda and Warner-Chilcott; has receiving consultant fees from AbbVie, Dr Falk, Gilead, GSK, Hospira, Iterative Scopes, Janssen, MSD, Oshi Health, Pfizer Inc., Pharmacosmos, Takeda, Topivert, Trellus Health and Vifor Pharma and has received research funding from AbbVie and Gilead. J.T. has received advisory board fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen and Pfizer Inc.; has received research grants from AbbVie and Janssen and has received speaker fees from AbbVie, Galapagos, Janssen and Pfizer Inc. Y.L. has served on advisory committee/as a board member for AbbVie, Celltrion, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer Inc., Sandoz, Takeda and has acted as a consultant for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Pfizer Inc. and Takeda. S.V. has received research grants from AbbVie, Galapagos, J&J, Pfizer and Takeda and has received speakers’ and/or consultancy fees from AbbVie, Abivax, AbolerISPharma, AgomAb, Alimentiv, Arena Pharmaceuticals, AstraZeneca, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Cytoki Pharma, Dr Falk Pharma, Ferring, Galapagos, Genentech-Roche, Gilead, GSK, Hospira, Imidomics, Janssen, J&J, Lilly, Materia Prima, Mestag Therapeutics, MiroBio, Morphic, MrMHealth, Mundipharma, MSD, Pfizer Inc., Prodigest, Progenity, Prometheus, Robarts Clinical Trials, Surrozen, Takeda, Theravance, Tillotts Pharma AG, VectivBio, Ventyx and Zealand Pharma. M.F., I.M., A.M., K.L., M.K. and J.W. are employees and shareholders of Pfizer Inc. M.G. is an employee and shareholder of Pfizer AG. E.V.L. has received consulting fees from AbbVie, Alvotech, Amgen, Arena, Astellas, Avalo Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltrion Healthcare, Eli Lilly Fresenius Kabi, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, Gossamer Bio, Iota Biosciences, Iterative Health, Janssen, KSL Diagnostics, Morphic Therapeutic, Ono Pharma, Protagonist, Scipher Medicine, Sun Pharma, Surrozen, Takeda, TR1X and UCB Pharma; has received research support from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene/Receptos, Genentech, Gilead, Gossamer Bio, Janssen, Pfizer Inc., Takeda, Theravance and UCB Pharma and is a shareholder of Exact Sciences.

Availability of data and materials: Upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

References

- 1. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, et al. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2017; 389: 1756–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: ulcerative colitis in adults. Am J Gastroenterol 2019; 114: 384–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. D’Amico F, Vieujean S, Caron B, et al. Risk–benefit of IBD drugs: a physicians and patients survey. J Clin Med 2023; 12: 3094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Food and Drug Administration. What is a serious adverse event?, https://www.fda.gov/safety/reporting-serious-problems-fda/what-serious-adverse-event (2023, accessed 14 September 2023).

- 5. Vermeire S, Chiorean M, Panés J, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of etrasimod for ulcerative colitis: results from the open-label extension of the OASIS study. J Crohns Colitis 2021; 15: 950–959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sandborn WJ, D’Haens GR, Sands BE, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: an integrated summary of up to 7.8 years of safety data from the global clinical programme. J Crohns Colitis 2023; 17: 338–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heeley E, Riley J, Layton D, et al. Prescription-event monitoring and reporting of adverse drug reactions. Lancet 2001; 358: 1872–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sandborn WJ, Lawendy N, Danese S, et al. Safety and efficacy of tofacitinib for treatment of ulcerative colitis: final analysis of OCTAVE open, an open-label, long-term extension study with up to 7.0 years of treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2022; 55: 464–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, D’Haens G, et al. Ozanimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2021; 385: 1280–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cohen RD, Bhayat F, Blake A, et al. The safety profile of vedolizumab in ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: 4 years of global post-marketing data. J Crohns Colitis 2020; 14: 192–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dubrall D, Schmid M, Alešik E, et al. Frequent adverse drug reactions, and medication groups under suspicion. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2018; 115: 393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rolfes L, van Hunsel F, Taxis K, et al. The impact of experiencing adverse drug reactions on the patient’s quality of life: a retrospective cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. Drug Saf 2016; 39: 769–776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Zhang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of etrasimod in a phase 2 randomized trial of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2020; 158: 550–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Etrasimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (ELEVATE): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies. Lancet 2023; 401: 1159–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Regueiro M, Siegmund B, Yarur AJ, et al. Etrasimod for the treatment of ulcerative colitis: analysis of infection events from the ELEVATE UC Clinical Program. J Crohns Colitis 2024; 18(10): 1596–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The international classification of headache disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Regueiro M, Hunter T, Lukanova R, et al. Burden of fatigue among patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease: results from a global survey of patients and gastroenterologists. Adv Ther 2023; 40: 474–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 699–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrari A. Headache: one of the most common and troublesome adverse reactions to drugs. Curr Drug Saf 2006; 1: 43–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Akiho H, Yokoyama A, Abe S, et al. Promising biological therapies for ulcerative colitis: a review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2015; 6: 219–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kappos L, Fox RJ, Burcklen M, et al. Ponesimod compared with teriflunomide in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis in the active-comparator phase 3 OPTIMUM study: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol 2021; 78: 558–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. US Food and Drug Administration. PONVORY® (ponesimod)—highlights of prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2024/213498s005s006lbl.pdf (accessed 28 June 2024).

- 23. Kappos L, O’Connor P, Radue EW, et al. Long-term effects of fingolimod in multiple sclerosis: the randomized FREEDOMS extension trial. Neurology 2015; 84: 1582–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Danese S, Panaccione R, Abreu MT, et al. Efficacy and safety of approximately 3 years of continuous ozanimod in moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis: interim analysis of the True North open-label extension. J Crohns Colitis 2024; 18: 264–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Danese S, Roda G, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Evolving therapeutic goals in ulcerative colitis: towards disease clearance. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 17: 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sidhu S, Marine JE. Evaluating and managing bradycardia. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2020; 30: 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. European Medicines Agency. Gilenya summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/gilenya (accessed 29 September 2023).

- 28. European Medicines Agency. Zeposia summary of product characteristics. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/zeposia (accessed 29 September 2023).

- 29. Brossard P, Derendorf H, Xu J, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of ponesimod, a selective S1P1 receptor modulator, in the first-in-human study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2013; 76: 888–896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Singh S, Blanchard A, Walker JR, et al. Common symptoms and stressors among individuals with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tag-10.1177_17562848241293643 for Non-serious adverse events in patients with ulcerative colitis receiving etrasimod: an analysis of the phase II OASIS and phase III ELEVATE UC 52 and ELEVATE UC 12 clinical trials by Charlie W. Lees, Joana Torres, Yvette Leung, Séverine Vermeire, Marc Fellmann, Irene Modesto, Aoibhinn McDonnell, Krisztina Lazin, Michael Keating, Martina Goetsch, Joseph Wu and Edward V. Loftus in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology