ABSTRACT

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (STm) is a causative pathogen for robust inflammatory gastrointestinal disease and can lead to systemic infection. Eicosanoids, bioactive lipid mediators, play a crucial role in modulating both the induction and resolution of inflammatory responses during an infection. A subset of eicosanoids activates PPARs, nuclear receptor/transcription factors that regulate fatty acid metabolism, lipid body formation, and macrophage function. In this study, we determined that mice lacking PPARα exhibited reduced inflammatory hallmarks of STm infection, including lower inflammatory gene expression, cecal inflammation, and bacterial dissemination, along with a significant increase in cecal eicosanoid metabolism compared to wildtype C57BL/6 mice. In macrophages, STm favored M2b-polarized macrophages for intracellular infection, leading to reduced arachidonic acid and ceramide production. Inhibition of fatty acid oxidation via Etomoxir in STm-infected macrophages reduced bacterial burdens and promoted cell death. In Etomoxir-treated wildtype mice, STm infection increased ceramide production, decreased inflammatory gene expression in the cecum, and increased the number of STm-containing M1 macrophages in mesenteric lymph nodes. These findings revealed a novel role for the lipid-immune signaling axis in Salmonella infections, providing significant insights into the lipid-mediated regulation of inflammation during bacterial infections in the gut.

KEYWORDS: Salmonella Typhimurium, lipidomic analysis, eicosanoids, fatty acids, macrophages

Introduction

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (STm) is a Gram-negative intracellular pathogen responsible for more than one million cases of gastroenteritis occurring in the United States every year.1,2 Ingestion of STm via contaminated food or water causes an inflammatory gastrointestinal disease characterized by fever, acute diarrhea, intestinal inflammation, and the destruction of the gastrointestinal (GI) mucosa.3,4 Upon entry into the gastrointestinal tract, STm infects the intestinal epithelium, where it invades M cells and gets taken up by CD18+ immune cells, including macrophages.5,6 In some cases, after being internalized by phagocytes, STm persists intracellularly and disseminates into other tissues causing a systemic infection.3,7

Much of the activities of immune cells to induce and resolve inflammation are modulated by eicosanoids. Eicosanoids and related bioactive lipids are derived from polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFAs) precursors (e.g. arachidonic acids, EPA, and DHA). Upon activation, the arachidonic acid metabolism pathways (cyclooxygenase [COX], lipoxygenase [LOX], and cytochrome P450 [CYP450]) produce hundreds of bioactive lipids with diverse physiological activities on immune and nonimmune cells.8 For example, prostaglandins and thromboxanes are produced via the COX pathway; leukotrienes, HETEs, and lipoxins are produced via the LOX pathway; EET and DHETs are produced via the CYP450 pathway. The same enzyme families can metabolize DHA and EPA (omega-3 fatty acids) into anti-inflammatory/pro-resolution mediators (e.g. resolvins, protectins, and maresins). Having proinflammatory or anti-inflammatory/pro-resolution activities, these signaling molecules play critical roles in the induction and resolution of inflammation. Some eicosanoid mediators are endogenous ligands for PPAR, a nuclear receptor and transcription factor that plays a major role in fatty acid metabolism, lipid body formation, and regulation of macrophage physiology and function.9 PPAR consists of three subtypes, PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ which are activated by different eicosanoids and fatty acids.10 Fatty acids, acting both free and as part of larger lipid molecules, serve as important cell membrane components, signaling molecules, and energy suppliers.11 Through PPAR, fatty acids can regulate gene expression and subsequently alter cellular processes, including macrophage polarization.

Macrophages, as sentinel immune cells that perform diverse immunological functions, integrate signals from the microenvironment and polarize into distinct subtypes.12 Upon encountering immune stimulatory signals, macrophages become either classically activated (M1, TH1 response) or alternatively activated (M2), with M2 macrophages further divided into M2a (TH2 response, parasite control), M2b (immunoregulation), M2c (Immunoregulation & wound healing), and M2d (tumor-associated) subsets based on their function. In complex environments, macrophage polarization is a continuum whereby classically accepted subsets are often muddled. Macrophage polarization is reliant on either glycolysis or fatty acid oxidation (FAO, also known as β-oxidation) for M1 or M2 polarization, respectively.13–16 β-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids (LCFA) utilizes the carnitine palmitoyltransferase (CPT) system, consisting of one transporter and two mitochondrial membrane enzymes: CPT1 and CPT2, which transport LCFAs into the mitochondrial matrix to produce ATP.17,18 PPAR targeting of ACOX1, the gene encoding acetyl CoA oxidase, catalyzes the rate-limiting step of FAO.19 PPAR signaling has been shown to be induced in macrophages following infection with multiple types of pathogens, including Staphylococcus aureus, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and Trypanosoma cruzi, mediating alternative activation of M2 macrophages and decreasing inflammation.20–22

Recent studies have suggested an important role for macrophage polarization in STm infections. Upon infection, STm translocates the virulence factor SteE in macrophages and drives phenotypic switching to anti-inflammatory M2 polarization through non-canonical STAT3 activation and IL-4 production.23–25 Additionally, PPARβ/δ-regulated metabolism of M2 macrophages provides a long-term intracellular survival niche for STm.26

In addition to macrophage polarization, fatty acids also have been shown to regulate other immunological processes. Ceramides, the main type of bioactive sphingolipids (lipids containing a sphingoid base backbone), are essential structural components of eukaryotic membranes and have been shown to promote programmed cell death (including apoptosis), cell cycle arrest, and induction of autophagy, which contribute heavily to the immunological response to pathogens.27–31 In addition, ceramide and sphingosine kinase signaling has been shown to mediate pyroptosis (Caspase-dependent inflammatory cell death often triggered by microbial infection) and worsen gram-negative sepsis outcomes.32,33 Accumulation of very long chain fatty acids (>22 carbons) and ceramide have also been shown to promote necroptosis (a pro-inflammatory lytic cell death dependent on RIP kinases).34

The interactions between lipid metabolism and immunological processes define the lipid-immune signaling axis, whereby the inflammation initiated to fight an infection triggers eicosanoid metabolism, leading to the production of COX, LOX, and CYP450 metabolites (bioactive lipids) to regulate the immunological functions. Some of these lipids activate PPARα signaling which alters fatty acid metabolism and affects macrophage polarization at the site of infection, thus modulating the immune response mounted for the infection.10,20,21,35 In the present study, we used C57BL/6J wildtype and Ppara—/— macrophages and mice to dissect the roles that eicosanoid and fatty acid metabolism play in the inflammatory response to STm infections, including macrophage polarization and the progression and outcome of the infection. We also tested the fatty acid oxidation inhibitor Etomoxir as an immunomodulatory agent for combatting STm infection. Overall, our study indicated that PPARα exacerbates STm infection through the modulation of lipid-mediated immunometabolism and subsequently macrophage polarization.

Methods

Bacterial strains

Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 14028 pBR322 PtetA-gfp (pDW5)36 or Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 14028 pTRC/alphaTomato (Supplementary figure S5)37 were grown with shaking (200 rpm) in 5 ml Luria-Bertani (LB) broth with 50 μg/ml carbenicillin (GFP) or chloramphenicol (tdTomato) at 37°C for 18 hr, then subsequently used for experiments.

Animal husbandry

Animals are kept under the veterinary care of the Temple University Laboratory and Animal Resources (ULAR) department. Mice are assessed for health and safety and are provided fresh food and water by animal husbandry staff. The facility undergoes a 12-hour daylight, 12-hour nighttime cycle. The Temple University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) has approved our experimental and care approaches.

Mouse Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium infections

C57BL/6J (wildtype, C57BL/6) and Ppara—/— (Stock No: 008154) mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Infection groups were randomly selected among male mice aged 7–10 weeks from holding colony. Littermate controls were used where possible to mitigate the effects of varying intestinal microbiotas on the establishment of STm infection and subsequent immune response. Previously established streptomycin-pretreated mouse model38 was used to model STm-induced gastroenteritis. Briefly, mice were orally administered 20 mg of streptomycin/mouse (Thermo Scientific) via oral gavage 24 hours prior to infection, then administered 108 CFUs of GFP-expressing STm or LB media (control) via oral gavage. Mice receiving Etomoxir treatment were administered 100uL of 3 mg/mL Etomoxir (Cayman Chemical) in sterile PBS with 10% DMSO via intraperitoneal injection at the time of STm infection and repeated at 24-hours post-infection. After 48-hours, fecal pellets were collected from mice before euthanasia via CO2. Post-euthanasia, liver, spleen, cecum, and mesenteric lymph nodes were harvested for further sample processing.

Histopathology

Murine cecum tissues were extracted and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for at least 24 hrs, then embedded in paraffin prior to sectioning. Sections of 5 μm of the tissue were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Embedding, sectioning, and staining of formalin-fixed cecum samples were performed by the Fox Chase Cancer Center Histopathology core (Philadelphia, PA).

H&E staining

After the matrix was visibly removed, slides were stained with Hematoxylin for 2 minutes and acidified eosin stain for 2 minutes. Sections were then covered with glass coverslip and mounted with Permount™ (Fisher Scientific). All stains and mounting reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and solvents were sourced from Fisher Scientific (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Histopathology scoring

The histopathological scoring for blinded cecum samples was performed by an experienced veterinary pathologist according to the following criteria: (i) Submucosal edema. Submucosal edema was scored as follows: 0 = no pathological changes; 1 = mild edema (the submucosa is <0.20 mm wide and accounts for < 50% of the diameter of the entire intestinal wall [tunica muscularis to epithelium]); 2 = moderate edema; the submucosa is 0.21 to 0.45 mm wide and accounts for 50 to 80% of the diameter of the entire intestinal wall; and 3 = profound edema (the submucosa is >0.46 mm wide and accounts for > 80% of the diameter of the entire intestinal wall). The submucosa widths were determined by quantitative microscopy and represent the averages of 30 evenly spaced radial measurements of the distance between the tunica muscularis and the lamina mucosalis mucosae. (ii) PMN infiltration into the lamina propria (LP). Polymorphonuclear granulocytes (PMN) in the lamina propria were enumerated in 10 high-power fields (×400 magnification; field diameter of 420 μm), and the average number of PMN/high-power field was calculated. The scores were defined as follows: 0 = <5 PMN/high-power field; 1 = 5 to 20 PMN/high-power field; 2 = 21 to 60/high-power field; 3 = 61 to 100/high-power field; and 4 = >100/high-power field. Transmigration of PMN into the intestinal lumen was consistently observed when the number of PMN was > 60 PMN/high-power field. (iii) Goblet cells. The average number of goblet cells per high-power field (magnification, ×400) was determined from 10 different regions of the cecal epithelium. Scoring was as follows: 0 = >28 goblet cells/high-power field (magnification, ×400) 1 = 11 to 28 goblet cells/high-power field; 2 = 1 to 10 goblet cells/high-power field; and 3 = <1 goblet cell/high-power field. (iv) Epithelial integrity. Epithelial integrity was scored as follows: 0 = no pathological changes detectable in 10 high-power fields (×400 magnification); 1 = epithelial desquamation; 2 = erosion of the epithelial surface (gaps of 1 to 10 epithelial cells/lesion); and 3 = epithelial ulceration (gaps of > 10 epithelial cells/lesion; at this stage, there is generally granulation tissue below the epithelium).

Stimulation and infection of macrophages

Hoxb8-derived39,40 or bone-marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were seeded into 24-well plates at 3 × 105 cells per well. Cells were stimulated with vehicle (DMSO) or Etomoxir (3 µM, Cayman Chemical).41 Etomoxir is a CPT1 chemical inhibitor. Chemical stimulation was performed one hour prior to infection. Macrophages were then infected with STm at an MOI of 20 for 90 mins, followed by PBS wash and treatment with gentamicin (100ug/mL, ThermoFisher) in fresh media for 90 mins, unless stated otherwise. Cells used for subsequent analysis following PBS washes. All experiments were performed with three technical replicates per condition and with at least three biological replications.

RNA extraction and q-PCR

RNA was extracted from macrophage cell suspension or homogenized cecal tissue by TRIzol (Invitrogen) and Direct-zol 96 RNA Preps (Zymo Research). cDNA was synthesized using random hexamer and TaqMan Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems). TaqMan Fast Advance Master mix and TaqMan Primer/Probe sets were used for q-PCR in ABI StepOne System (Applied Biosystems).

Automated digital microscopy

For analysis of bacterial burdens and lipid body dynamics, fixed cells were stained with DAPI (4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, dihydrochloride) (ThermoFisher), Cell MaskTM Orange (Thermofisher), and LipidTOXTM Deep Red Neutral Lipid Stain (Invitrogen). For cell death assays, live cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) and Propidium Iodide (Alfa Aesar). For quantification of dead versus total intracellular STm, live cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) and SytoxTM Green (Thermofisher). Images were captured using EVOS 2 FL (Invitrogen) and analyzed using HCS Studio Cell Analysis Software (ThermoFisher).

Macrophage polarization

BMDMs were stimulated with the following conditions for 48hrs to induce respective M0 and M2b polarizations: M0- DMSO (naïve control, 1uL/mL media), M2b- Immune complex (IC) of Ova and anti-Ova antibodies (Polysciences, #23744-5, ova: 0.046ug/uL, anti-ova: 0.63 ug/uL) and LPS (from Salmonella Minnesota R595, List Biological Laboratories, 304, 10 ng/mL). Macrophages were then washed with PBS and used for subsequent experiments.

Flow cytometry analysis

Single-cell suspensions of mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) were stained with the following: Anti-CD45 Brilliant UV 395 (Thermofisher), Anti-CD11b Alexa Fluor 700 (Thermofisher), Anti-F4/80 PE (Thermofisher), Anti-CD80 Super Bright 600 (Thermofisher), Anti-CD206 APC (Thermofisher), Anti-CD86 Super Bright 436 (Thermofisher), and Fixable Viability Dye eFlour780 (eBioscience). Flow cytometry was done on BD FACSymphony™ A5 Cell Analyzer (Franklin Lakes, NJ) and FlowJo (Ashland, OR) software was used for analysis.

Lipidomic profiling by Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS)

Lipid mediators were examined by LC-MS essentially as described previously.42–44 Before lipid metabolite isolation by solid phase extraction (SPE, Eicosanoids)45 or Bligh & Dyer Fatty Acid Extraction (Fatty Acids),46 deuterated standards (Cayman Chemical) were added. Methanol or chloroform, respectively, was evaporated and the samples reconstituted in a minimal volume of water/acetonitrile (60/40) containing 0.02% v/v acetic acid. Eicosanoids were separated using a Waters Acquity UPLC BEH 1.7 μm 2.1 × 50 mm column using a 4 minute gradient of 99.9% A/B to 75/25 A/B followed by washing and reconditioning. Solvent A is 50/50 water/acetonitrile containing 0.02% acetic acid and solvent B is 50/50 acetonitrile/isopropanol. Eicosanoids were analyzed by a Waters Synapt G2Si QTOF operated in negative-ionization mode via MSe. Data analysis was performed using UNIFI 1.6 (Waters), MS-DIAL447 and Mzmine 2.53.48

Bacterial burdens by colony forming units (CFU)

For in vivo experiments, liver, spleen, and fecal pellets were weighed, homogenized, and plated on selective media for 24-hours at 37°C. For in vitro experiments, macrophages were resuspended in PBS with 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma) to release intracellular bacteria, then plated on selective media for 24-hrs at 37°C. GFP+ colonies were enumerated and imaged under digital fluorescent microscopy.

Statistical analysis

Prism software (Graphpad) was utilized for data analysis. Statistical analyses were performed using One- or two-way ANOVA, with error determined as standard error of the mean and significant values determined by p values of < 0.05.

Results

Ppara—/— mice are more resistant to bacterial dissemination and inflammation induced by STm infection

While PPARγ and PPARδ have been shown to play a role during STm infections, the role of PPARα has not been investigated. To investigate whether PPARα-dependent immune modulation and fatty acid metabolic regulation during STm infection would affect disease presentation, we used the streptomycin-pretreated mouse model38 and infected C57BL/6 (wildtype) and Ppara—/— mice with 108 Colony forming units (CFU) of GFP-expressing STm. To investigate the early inflammatory events, we sacrificed the mice at 48-hours post-infection. Interestingly, Ppara—/— mice had significantly lower CFUs in the spleen and lower bacterial shedding in the fecal pellet compared to wildtype mice (Figure 1a). Although lower levels of bacterial burden were also determined in the liver of Ppara—/— mice, the difference did not reach statistical significance (Figure 1a). Next, we determined the expression of immune-related genes, including pro-inflammatory cytokines Il6 and Il1b, M1 pro-inflammatory macrophage marker Il12b, type I interferon response genes Ifit1 and Mx1, type II interferon Ifng, Tumor necrosis factor alpha (Tnfa), and chemokine Cxcl1 by q-PCR in the cecal tissue of mice from both groups. We found that the inflammatory gene expression in cecal tissue homogenates of Ppara—/— mice was lower compared to that of wildtype mice (Figure 1b). Hematoxylin and eosin-stained cecum sections from Ppara—/— mice also showed significantly lower total inflammatory pathology scores – specifically, Ppara—/— mice had lower numbers of goblet cells and increased maintenance of the epithelial integrity compared to wildtype mice (Figure 1c,d; S1). These data suggest that Ppara—/— mice are more resistant to STm-induced intestinal inflammation and bacterial dissemination than wildtype mice. To assess the immune cell populations, we isolated cells from the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) and found that both wild-type and Ppara–/– mice showed a similar increase in GFP-expressing STm-containing M1 macrophages (CD11b+ F4/80+ CD206- CD86+ CD80+ STm-GFP+) (Figure 1e, S8). However, wild-type mice exhibited a higher number of infected M2 macrophages. This suggests that in wild-type mice, the increased M2 macrophages likely support STm survival and replication within these cells.

Figure 1.

Ppara—/— mice exhibit increased resistance to STm-induced inflammation. Male mice (n = 4-7 per group) were infected with 108 GFP-expressing STm (or LB media only) via oral gavage 24-hrs following oral streptomycin treatment. Cecum, liver, and spleenwere collected for analysis 48 hours post infection. (a) Colony forming units (CFU) were quantified in the liver and spleen of infected animals. Bar graph represents the mean and standard error of the mean (SEM). (b) RNA was extracted from cecum homogenate and TaqMan Primer/Probe sets were used for q-PCR. Relative gene expression represents normalization to the housekeeping gene Eif1a. (c&d) Histopathology with H&E staining and inflammatory pathology scores of formalin-fixed cecum tissue. (e) Flow cytometry analysis of M1 and M2 macrophages from MLN single-cell suspensions. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. 2-way ANOVA was performed to determine statistical significance (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < .0001). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

STm-infected Ppara—/— mice have increased eicosanoid metabolism in cecal tissue

Eicosanoids that signal through PPARα are important immune mediators during inflammation and infection.20,42,43 Since Ppara—/— are more resistant to STm-induced inflammation, we hypothesized that eicosanoid metabolism may be altered during infections, contributing to this resistance. Using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry with deuterated internal standards, we measured the eicosanoid profile during STm infection within the cecal tissue isolated from wildtype C57BL/6 and Ppara—/— mice. We found that following STm infection, cecal tissue from Ppara—/— mice had a more pronounced increase in eicosanoid production compared to uninfected mice, while the increase in eicosanoid production in wildtype mice following infection was not nearly as prominent (Figure 2a). Interestingly, we noted a significant increase in the production of eicosanoid species from multiple pathways, including the Cyclooxygenase (COX) pathway, Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), Lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway, Leukotriene B4 (LTB4), Cytochrome P450 (CYP450) pathway (11,12-EET and 11,12-DHET), EPA and DHA-metabolites (Resolvin D1) in Salmonella-infected Ppara—/— mice compared to wild type infected or uninfected tissues (Figure 2b). Given the increase in multiple eicosanoid pathway metabolites rather than an individual pathway, these data suggest that the more significant increase in cecum eicosanoid production in STm-infected Ppara—/— compared to wildtype mice may contribute to the improved control of infection (i.e. decreased bacterial burdens) and the lower overall systemic inflammatory response.

Figure 2.

Eicosanoid profiling shows increased lipid metabolism in Ppara—/— mice during STm infection. Male mice (n = 4-7 per group) were infected with 108 GFP-expressing STm (or LB media only) via oral gavage 24-hrs following oral streptomycin treatment. Cecum was collected and analyzed 48-hrs post-infection. Eicosanoids were extracted from cecum homogenate via solid-phase extraction and analyzed by LC-MS. (a) Heat map of eicosanoids organized by enzyme families (COX, Cyclooxygenase; LOX, Lipoxygenase; CYP, cytochrome P450; DHA, docosahexaenoic acids; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acids; Lino, linoleic acids). Due to the variability in concentrations across different metabolites, the heatmap displays the mean normalized levels, with each lipid species scaled to its individual sample maximum (normalized to 100). (b) Average relative intensity of individual eicosanoid species under different conditions. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. Relative intensity represents concentration. Statistical significance was determined using 2-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < .0001). Figures are representative of three independent experiments.

Ppara—/— M2b-polarized macrophages have lower internalized bacteria following STm infection

We have recently established that PPARα dependent fatty acid metabolic regulation skew macrophages from a classically activated M1 phenotype to an immunoregulatory M2b phenotype.20,42,43 Since Salmonella takes residence in M2 macrophages to establish persistent infections,25,26 we investigated whether STm infections in naïve or M2b-polarized macrophages lacking PPARα would influence lipid metabolism and bacterial burdens. We stimulated Bone-marrow-derived (BMDM) C57BL/6 and Ppara—/— macrophages to naïve (M0) or M2b (LPS/Immune complex [Ova-Anti-Ova]) polarization subtypes. We then infected the macrophages with STm and used fluorescence microscopy to visualize lipid bodies and bacterial burdens within the cell following infection. Lipid bodies are subcellular organelles that form in immune cells during inflammatory conditions and serve as sites for synthesis and storage of bioactive lipid mediators.49 Assessing the size/area and amount of lipid bodies can serve as a macroscopic indicator of eicosanoid metabolism dynamics within the cell. We found that Ppara—/— M2b-polarized BMDMs have lower bacterial loads than wildtype macrophage (Figure 3a,c). In addition, STm infection increased lipid body counts in wildtype M2b macrophages but did not affect lipid body counts in Ppara—/— M2b macrophages (Figure 3b,c). These data suggest that, in macrophages (M0 and M2b-polarized), deficiency in PPARα is beneficial for combatting STm infection.

Figure 3.

STm infection in M2b-polarized macrophages influences bacterial burden, lipid body production, and eicosanoid production. Bone marrow-derived macrophages from C57BL/6 and Ppara—/— mice were treated with DMSO (naïve, M0) or polarized to M2b for 48hrs, followed by infection with STm for 90 minutes and subsequent gentamicin treatment for 90 minutes. (a-c) Fluorescence microscopy analysis (a, b) and representative images (c) showing internalized STm (a) and lipid body count (b) per macrophage. (d) Average relative intensity of individual arachidonic acid and fatty acid species under different conditions. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using 2-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < .0001). Data are representative of three independent experiments.

STm infection reduces arachidonic acid and ceramide in wildtype M2b-polarized macrophages

After determining that STm infection of wildtype M2b macrophages showed higher lipid body counts, we then aimed to assess the global fatty acid profile changes in naïve and M2b macrophages due to STm infection. We hypothesized that the presence or absence of PPARα in polarized macrophages may alter the changes in STm-induced fatty acid metabolism. We used LC-MS to identify fatty acids in polarized and STm-infected macrophages, determining that fatty acid profiles between wildtype and Ppara—/— naïve and M2b-polarized BMDMs differentially cluster depending on polarization state and infection status (Figure S3a,b, Table S1). We noticed that the shift in fatty acid profiles following STm infection is much more pronounced in Ppara—/— BMDMs, as illustrated by the heatmap and PCA plots (Figure S3a,b).

Further, we characterized the STm infection-induced changes in levels of arachidonic acid (main precursor of eicosanoids) and ceramide (Cer 33:2:4O & Cer 25:2;4O) in wildtype and Ppara—/— naïve and M2b-polarized macrophages, determining that wildtype M2b-polarized macrophages have significantly reduced levels of arachidonic acid and ceramide following infection, while macrophages lacking PPARα were unchanged (Figure 3d). This suggests that STm infection in M2b macrophages reduces ceramide production in a PPARα-dependent manner.

Etomoxir reduces bacterial invasion and promotes lipid body production, cell death, and anti-bacterial activity in STm-infected wildtype macrophages

After determining that STm infection reduced ceramide in M2b-polarized macrophages, we hypothesized that STm induces LCFA β-oxidation, preventing ceramide accumulation and ceramide-induced cell death to promote intracellular survival for long-term persistence. Given this, we aimed to test the pharmacological agent Etomoxir, an inhibitor of fatty acid β-oxidation through specific inhibition of CPT1, to counteract STm-mediated M2-polarization and promote ceramide production and cell death during infection (Figure 4a). Previous research has shown that Etomoxir disrupts CoA homeostasis and subsequently inhibits macrophage polarization at in vitro concentrations over 100uM, thus we utilized a much lower concentration of 3uM for our in vitro experiments, as off-target effects were not observed at this concentration.50

Figure 4.

Etomoxir induces cell death, reduces bacterial burden, and enhances anti-bacterial activity in STm-infected wildtype macrophages. (a) Schematic representation of PPARα-mediated long-chain fatty acid (LCFA) uptake leading to fatty acid oxidation (FAO) via CPT–1 or cell death via ceramide accumulation. PPARα activation promotes the cellular uptake of long-chain fatty acids (LCFAs), which are converted to LCFA. These are either used for fatty acid oxidation (FAO), contributing to M2 macrophage polarization, or converted to ceramides, whose accumulations promotes cell death. Inhibition of CPT–1 blocks FAO, shifting the conversion of LCFAs toward ceramide production. Created with BioRender. (b–f) C57BL/6 hox-derived macrophages were treated with DMSO (vehicle control) or Etomoxir for 1 hr, then infected with STm at MOI 20 for 3hrs (e) or 90 mins, followed by gentamicin treatment in fresh media for 90 mins (b–c, f). Fluorescence microscopy analysis (b-c,e) and representative images (d) of internalized STm (b), lipid body dynamics (c) and cell death (e). (e) Microscopy analysis of cell death measured by the percentage of propidiumiodide-stained nuclei (dead) relative to Hoechst-stained nuclei (total). (f) RNA was extracted from macrophages and TaqMan Primer/Probe sets were used for q-PCR. Relative gene expression was normalized to housekeeping gene Eif1a. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using 2-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p <.0001). Figures are representative of three independent experiments.

We first hypothesized that perturbation of ceramide-induced cell death through inhibition of CPT-1 would reduce the intracellular niche of STm. We pre-stimulated Hoxb8-derived wildtype (Figure 4) and Ppara—/— (Figure S7) macrophages with Etomoxir and measured STm burdens (Figure 4b,d), lipid body dynamics (Figure 4c,d), cell death (Figure 4e, S4), and expression of Cxcl1 (Figure 4f) following infection. We determined that Etomoxir treatment in wildtype macrophages reduced STm load (Figure 4b,d, S5a) and increased lipid body numbers in wildtype macrophages (Figure 4c,d). We also determined that Etomoxir increased cell death following STm infection (Figure 4e, S4). Lastly, we also found that Etomoxir treatment increased Cxcl1 expression in STm-infected wildtype macrophages (Figure 4f). This data suggests that inhibition of CPT-1 and subsequently fatty acid β-oxidation can reduce bacterial burdens and promote pro-inflammatory activities and cell death in wildtype macrophages, which aid in combatting infection.

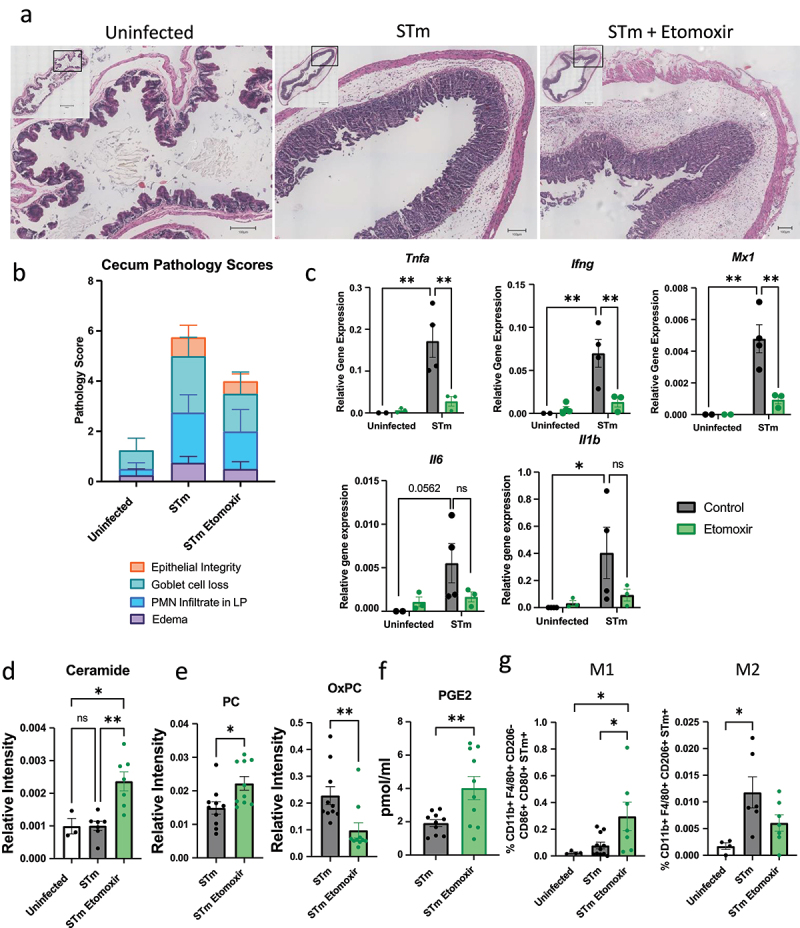

Etomoxir treatment of STm-infected mice increases ceramide production, reduces inflammatory gene expression, and increases PC and PGE2 levels in cecal tissue

To test whether Etomoxir treatment can be a pharmacological treatment for Salmonella infection in vivo, we administered Etomoxir via intraperitoneal injection in wildtype mice at the time of STm oral infection and 24-hours post-infection. At 48-hours post-infection, mice were euthanized, and cecum, MLNs, liver, spleen, and fecal pellets were extracted for analysis. Mice treated with Etomoxir exhibited a trend toward reduced cecal inflammation, although the decrease did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5a,b, S6). Specifically, Etomoxir-treated mice showed slightly lower scores for goblet cell loss and epithelial integrity in cecal tissue compared to STm-infected controls; however, these differences were not statistically significant (Figure 5a,b, S6, data n.s). Although the inflammation pathology was not significantly altered, we did observe that the expression of Tnfa, Mx1, and Ifng were lowered in Etomoxir-treated cecal tissue following infection compared to non-treated STm-infected mice (Figure 5c). We also observed a decrease in Il6 and Il1b expression in Etomoxir-treated infected mice, though this was not statistically significant (Figure 5c). This data suggests a dampening effect on the proinflammatory cytokine expression induced by STm infection that resembled the phenotype in the resistant Ppara—/— mice (Figure 1b). We analyzed cecal tissue for ceramide production, determining that Etomoxir treatment increased ceramide in cecal tissue in STm-infected mice (Figure 5d). In addition, we measured the levels of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and oxidized PC (oxPC) in the cecal tissue of STm-infected mice following Etomoxir treatment. Previous studies have demonstrated a protective role of PC in the gastrointestinal tract – PC and other phospholipids may contribute to establishing a hydrophobic surface and play key roles in barrier properties of intestinal tissue.51–55 Etomoxir-treated mice exhibited an increased level of PC following infection was increased, accompanied by a decreased level of oxPC in cecal tissue (Figure 5e). These findings suggest that Etomoxir treatment enhances barrier protection in the gastrointestinal tract and inhibits LCFA import into the mitochondria for β-oxidation, as indicated by the reduced oxPC levels. PGE2 levels in the cecal tissue of Etomoxir-treated mice were higher than those in untreated mice (Figure 5f), suggesting that Etomoxir may enhance pro-inflammatory activities in the cecal tissue through increased production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids.

Figure 5.

Etomoxir treatment of STm-infected mice increases ceramide production, reduces inflammatory gene expression, and increases PC and PGE2 levels in cecal tissue. Male mice (n = 4-10 per group) were infected with GFP-expressing STm via oral gavage 24-hours following oral streptomycin treatment. Where applicable, mice were administered etomoxir in PBS with 10% DMSO via i.P. injection at the time of infection and 24-hrs post-infection. Cecum and mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) were collected and analyzed 48-hrs post-infection. Bar graphs represent mean and SEM. (a, b) Cecum pathology scoring and representative images for formalin-fixed, H&E-stained cecum sections. (c) RNA was extracted from cecal homogenate, and TaqMan Primer/Probe sets were used for q-PCR. Relative gene expression was normalized to housekeeping gene Eif1a. Bar graphs depicting the mean ± SEM. (d) Average relative intensity of ceramide in cecal tissue. (e, f) Average relative intensity of phosphatidylcholine (PC) and oxidized PC (OxPC) (e) and PGE2 (f) in cecal tissue. (g) Flow cytometry analysis of M1 and M2 macrophages from MLN single-cell suspensions. Bar graphs represent the mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined using one-way or 2-way ANOVA (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < .0001). Figures are representative of three independent experiments.

Finally, we isolated cells from mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) to assess inflammatory cell populations and found a significant increase in the percentage of STm-containing M1 macrophages (CD11b+ F4/80+ CD206- CD86+ CD80+ STm-GFP+) and no significant change in M2 (CD11b+ F4/80+ CD206+ STm-GFP+) macrophages in Etomoxir-treated mice compared to untreated controls (Figure 5g, S8). This suggests that Etomoxir impairs the switch from M1 to M2 macrophages, further promoting bacterial uptake and clearance by proinflammatory macrophages. However, there was no significant difference in bacterial dissemination to the liver and spleen or in bacterial shedding in fecal pellets between Etomoxir-treated and untreated mice (Figure S7).

Discussion

STm is an intracellular pathogen that triggers an inflammatory gastrointestinal disease and can cause systemic infection by surviving in phagocytes and disseminating into other tissues. Inflammatory responses to infection or injury are modulated by eicosanoids, which are bioactive lipid mediators. Some eicosanoids serve as endogenous ligands for PPARs, which regulate macrophage polarization and fatty acid metabolism. Although PPARβ/δ is known to promote a metabolic environment that supports STm long-term survival in macrophages and mice26 and PPARγ signaling activated by host microbiota helps reduce dysbiotic expansion of Salmonella in the gut lumen,56 the role of PPARα in STm-mediated immune responses is less understood. Here, we investigated the role of PPARα in STm-induced immune response, macrophage polarization, and inflammatory activities.

The expression of functional Slc11a1 (Natural resistance-associated macrophage protein-1; Nramp1) is known to confer resistance to STm in mice and macrophages derived from them. To avoid confounding variables, we sequenced Slc11a1 from C57BL/6 and Ppara—/— mice, confirming no differences in sequences. Therefore, the differences in STm infection pathology & immune response observed in this study are not influenced by variations in Slc11a1 gene sequence or function (data not shown).

The present study limited the in vivo studies of STm infections to male -specific responses, as males exhibit higher incidence of bacterial infections, sepsis, and related pathologies, and are generally considered more susceptible.57,58 We also observed more pronounced inflammatory responses mounted against STm infection in male mice compared to females in early studies (data not shown). Sex-specific differences in regulation of eicosanoid metabolism and PPARα expression via sex hormones have also been reported previously.58,59

In our gastroenteritis model of STm infection, Ppara—/— mice exhibited lower levels of bacteria in the spleen and fecal pellets (Figure 1a) and reduced expression of pro-inflammatory gene in the cecum compared to STm-infected wildtype mice, including reduced expression of type I IFN response genes (Ifit1 and Mx1) (Figure 1b). Previous research has shown that type I IFN signaling, which depends on STAT2, a PPARα target gene, contributes to an inflammatory environment in the gut that supports Salmonella replication.60,61 In line with this, we observed decreased cecal inflammation in Ppara—/— mice, as indicated by pathology scoring (Figure 1c,d). These findings suggest that PPARα deficiency reduces STAT-dependent type I IFN signaling and subsequent cecal inflammation during STm infection, impairing the pathogen’s inability to create a robust inflammatory environment and leading to reduced bacterial dissemination into liver and spleen tissue (Figure 1a).

Though the survival outcomes of wildtype and Ppara—/— mice were not addressed in the current study, we have shown in previous studies of survival outcomes of Ppara—/— mice compared to wildtype that Ppara—/— mice have increased survival following Influenza/Staphylococcus aureus superinfection model.43 This combined with our data showing reduced inflammation and bacterial dissemination in STm-infected Ppara—/— mice, which directly counteracts the necessity of an inflammatory environment in the gastrointestinal tract for STm persistence, we hypothesize that animals lacking PPARα would exhibit longer survival.

We also analyzed the eicosanoid profiles of cecum tissue following STm infection (Figure 2a,b). Previous studies on eicosanoids in STm infections have primarily focused on specific roles of individual metabolites, with prostaglandins being widely recognized as mediators for Gram-negative infections.62,63 Most studies have identified different prostaglandin species upregulated following infection,64–67 with COX2 expression induced in macrophages upon injection of virulence factors by the STm type three secretion system (T3SS) which promotes the inflammatory gut environment.64 In our study, we used a global lipidomic approach to assess changes in the eicosanoid metabolism and identify other potential eicosanoids produced during STm infection. We found that STm-infected cecum of Ppara—/— mice had higher eicosanoid levels than that of infected wildtype mice (Figure 2b). We identified increased levels of eicosanoid species from multiple pathways, not just the COX pathway, including increases in LOX pathway metabolite LTB4, a chemoattractant for inflammatory neutrophils, and CYP450 metabolites EET and DHET, which have been identified as PPARα agonists.61,68 Additionally, EPA and DHA pathway metabolite, Resolvin D1, a pro-resolution mediator, were also increased in Ppara—/— mice. This upregulation of eicosanoid production in the cecum paired with reduced inflammation and bacterial dissemination may suggest that loss of PPARα-mediated regulation may result in a dysregulated eicosanoid metabolism that is beneficial for pathogen control in the cecum.

We also investigated the expression of eicosanoid metabolism genes in cecal tissues, finding increased expression of prostaglandin genes Ptges and Ptges2, and the leukotriene gene Alox5ap in wildtype STm-infected mice, along with an increased expression of CYP450 gene Cyp2b10 in STm-infected Ppara—/— mice (Figure S2). These results do not fully explain the increased eicosanoid expression we observed in STm-infected Ppara—/— mice, but this is not surprising. Eicosanoid metabolism involves large enzyme families that act on multiple substrates, leading to significant pathway crosstalk. Additionally, since eicosanoids are part of a rapid response system (compared to cytokines), enzyme expression does not always correlate with protein levels or lipid abundance8 Interestingly, the correlation between Cyp2b10 expression and CYP450 metabolite abundance observed during STm infection is similar to findings from influenza infection studies.42 Our results of lipid abundances obtained using LC-MS likely provides a more representative view of the global shifts in the eicosanoid metabolome due to STm infection.

Our findings from the present study underscore the complexity of lipid-immune signaling, as eicosanoid-mediated immune responses involve concerted activities of multiple enzymes, families, and pathways to orchestrate a global response to induce and resolve inflammation during infection.

In previous studies, we established that PPARα-dependent fatty acid metabolism skews macrophages from a classically activated M1 phenotype to an immunoregulatory M2b phenotype.20,42,43 It is also known that STm infection induces M2 polarization through non-canonical STAT3 activation and upregulation of IL-4Rα which is driven by the delivery of virulence factor SteE.23–25 Given this, we hypothesized that M2b-polarized macrophages would serve as a preferred intracellular niche for STm survival. To test this, we measured bacterial burdens, lipid body dynamics, and lipid metabolism in naïve and M2b-polarized macrophages after STm infection.

Lipid bodies, which are actively formed in immune cells in response to inflammatory conditions, serve as sites for the synthesis and storage of inflammatory lipid mediators and are functionally active organelles.69 It has been established that T3SS-dependent lipid body biogenesis is induced in macrophages following STm infection.69 In this study, we further investigated lipid body biogenesis induced by STm in M2b-polarized macrophages and found that high lipid body loads in wildtype M2b-polarized macrophages correlated with higher bacterial burden (Figure 3a-c). Interestingly, we did not observe a marked increase in lipid body biogenesis in naïve macrophages, in contrast to previous findings by Souza et al – this is most likely due to differences in infection time points and staining methods, as significant differences in distribution patterns and intensities of lipid bodies have been reported between LipidTOX staining (used in this study) and Oil Red O staining (used by Souza et al).69,70 Additionally, though we observed significantly higher baseline lipid body biogenesis in Ppara—/— M2b macrophages compared to wildtype M2b macrophages, we interestingly did not observe a significant increase in lipid body biogenesis in Ppara—/— M2b macrophages following infection. This may suggest a baseline dysregulation of lipid metabolism in these cells that correlates to a lack of sensitivity to the effect of STm infection on lipid body biogenesis noted previously.

We also found that STm infection in wildtype M2b-polarized macrophages reduced intracellular arachidonic acid levels (Figure 3d). Arachidonic acid is a major precursor for the production of various eicosanoids stored in lipid bodies. Upon inflammatory stimuli, such as infection by an intracellular pathogen, arachidonic acid is rapidly converted to COX-, LOX-, and CYP450-derived metabolites for inflammatory signaling.49,71,72 The reduction of arachidonic acid in M2b cells following STm infection, along with the observed increase in lipid body biogenesis, suggests a rapid upregulation of eicosanoid synthesis and storage using intracellular arachidonic acid reserves. In contrast, Ppara—/— M2b macrophages displayed reduced arachidonic acid levels and an increased number of lipid bodies regardless of infection. The dysregulation of lipid metabolism, due to the loss of PPARα, may potentiate eicosanoid metabolism, leading to enhanced production of lipid mediators during infection. Overall, our findings suggest that PPARα contributes to STm-induced lipid biogenesis in M2b-polarized macrophages, and dysregulated lipid metabolism due to loss of PPARα may provide some protection against STm infection.

It is important to note that in vitro stimulation of macrophages using defined signals to promote specific polarization phenotypes represents extremes of a spectrum of macrophage polarization.12 While M1/M2 polarization is commonly used to describe macrophages, recent research indicates macrophage polarization is more representative of a spectrum of phenotypes influenced by external signals, cell metabolism, and functional activities. Additionally, although Hoxb8-derived macrophages are considered functionally similar to BMDMs, there may still be differences in immune responses mounted by conditionally immortalized cells.39

Etomoxir was originally developed as an antidiabetic agent for increasing insulin sensitivity through inhibition of β-oxidation in the mitochondria. However, there is growing interest in Etomoxir’s immune-modulating effects, including its ability to reprogram macrophage metabolic through lipid metabolism. After observed reduced ceramide production in wildtype M2b-polarized macrophages following STm infection (Figure 3d), we hypothesized that Etomoxir treatment could inhibit M2 polarization by inhibiting FAO, thereby shifting LCFA metabolism toward ceramide production, inducing cell death, and eliminating the intracellular niche for STm survival (Figure 4a). We tested this hypothesis by treating macrophages with Etomoxir to inhibit CPT-1, followed by STm infection. Our results showed that Etomoxir pretreatment reduced STm burden, promoted lipid body biogenesis, increased cell death, and elevated inflammatory gene expression in wildtype macrophages following STm infection (Figure 4b-g, S4, 5a).

To further investigate the effect of Etomoxir on phagocytosis and bacterial killing in macrophages, we utilized a Td-tomato-expressing STm strain and SytoxTM green staining to quantify total (Td-tomato+) and dead (Sytox+) bacteria within wildtype macrophages treated with Etomoxir. Live bacteria do not retain Sytox Green fluorescence, whereas killed bacteria, due to loss of its membrane integrity, are stained.20,73 After 30 minutes of gentamicin treatment, Etomoxir-treated macrophages showed higher intracellular counts of both total and dead bacteria, suggesting that shortly after infection, Etomoxir-treated macrophages exhibit enhanced phagocytosis and bacterial killing compared to untreated cells (Figure S5b,c). This further suggests that the lower bacterial burdens observed at 90 minutes post-gentamicin in Etomoxir-treated cells result from their ability to killed and clear more bacteria than untreated cells (Figure 4b, S5).

As well, though the specific type of cell death observed in the present study was not further characterized, previous studies have shown that accumulation of ceramides has been shown to induce multiple types of cell death, including apoptosis, pyroptosis, and necroptosis, as well as caspase-independent programmed cell death.31,33,34,74,75 Given that STm is an intracellular pathogen that can often trigger rapid pyroptotic (caspase-1-dependent) cell death upon infection, we hypothesize that the increased cell death we observed in STm-infected macrophages with Etomoxir treatment is indicative of enhanced pyroptosis (Figure 4e, S4).76,77 We further hypothesize that enhanced pyroptosis induced by ceramide accumulation due to Etomoxir may aid in reducing STm establishment of an intracellular niche. These findings suggests that inhibiting CPT-1 and subsequent fatty acid β-oxidation can enhance pro-inflammatory activities and cell death in wildtype macrophages, helping to combat infection.

We further hypothesized that Etomoxir may promote antibacterial activities in the mouse STm infection model by targeting FAO rather than PPAR, which has multiple other roles in immunomodulation. We tested Etomoxir in wildtype C57BL/6 mice only, as Ppara—/— mice develop myocyte lipid accumulation in the heart from Etomoxir treatment, which often leads to death.78,79 Our study found that Etomoxir treatment promoted ceramide production in cecal tissue (Figure 5d), suggesting a potential role in ceramide-induced cell death in the main organ harboring STm during infection, thereby reducing the intracellular niche for STm survival. Although we did not observe significant differences in cecum inflammatory pathology with Etomoxir treatment (Figure 5a,b), we did find decreased expression of Tnfa, Ifng, Mx1, Il6 (n.s), and Il1b (n.s) in the cecum of Etomoxir-treated mice (Figure 5c), similar to what we observed in Ppara—/— mice (Figure 1b). We suspect that the reduced inflammatory gene expression in the Etomoxir-treated cecum may play a critical role in limiting inflammatory responses that could otherwise promote STm establishment. Previous research has also established that TNF-α exposure alters Salmonella effector expression, inducing more inflammatory IL-8 production in intestinal epithelial cells. Thus, Etomoxir treatment may indirectly prevent this effect, reducing inflammatory cytokine production.80,81

We also measured phosphatidylcholine (PC) in the cecum following Etomoxir treatment in STm-infected mice. Previous studies suggest that PC and other phospholipids contribute to establishing a hydrophobic surface and play key roles in the barrier properties of intestinal tissue.51–55 PC has also been studied in the context of ulcerative colitis (UC), where low levels of PC in the mucus are associated with the chronic inflammatory disorder, and therapeutic PC supplementation in the gastrointestinal tract has been beneficial.51,54,82 Etomoxir treatment in STm-infected mice promoted PC production in the cecum, suggesting a mechanism for localized reduction of inflammation during STm infection (Figure 5e).

The increased PGE2 and decreased TNF-α we observed in STm-infected cecal tissue following Etomoxir treatment is interesting, as several studies have explored the relationship between these signaling molecules (Figure 5f). Previous studies have shown that pretreatment of macrophages with PGE2 prior to STm infection increases IL-1β and decreases TNF-α expression, with the downregulation of TNF-α resulting from destabilization and turnover of its mRNA.64,83,84 In contrast, in the gastrointestinal tract, PGE2-driven TNF-α production has been linked to impaired epithelial barrier function and induced Cl- and K+ secretion in the human colon, suggesting a role for PGE2-mediated TNF-α expression in diarrhea during intestinal inflammation.85,86 This highlights that the regulation of TNF-α expression by PGE2 is likely cell-type dependent. In our study, we hypothesize that the increased PGE2 levels in the cecal tissue of Etomoxir-treated mice (Figure 5f) may promote pro-inflammatory macrophage activities, such as inflammasome activation and M1 pro-inflammatory macrophage polarization locally in the cecal tissue, potentially reducing the STm intracellular niche. At the same time, the reduced TNF-α expression in the Etomoxir-treated mice may indicate reduced intestinal damage from STm-induced inflammation (Figure 5a,b). Furthermore, our observation that Etomoxir treatment increased the proportion of STm-containing M1-polarized macrophages and decreased the proportion of M2 macrophages in mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) further suggests enhanced bacterial uptake and potential clearance by pro-inflammatory macrophages and a reduction in STm uptake and persistence in M2 macrophages (Figure 5g, S8).

We also assessed antibacterial activities in Ppara—/— macrophages following Etomoxir treatment, finding that Etomoxir reduced STm burden and increased cell death following infection, while lipid body numbers and Cxcl1 expression remained unchanged (Figure S9). However, given that Ppara—/— macrophages had lower STm burdens and lipid body formation compared to C57BL/6 macrophages at baseline (Figure 3) and because testing Etomoxir in Ppara—/— mice was not feasible due to the cardiac effects mentioned previously, the present study focused on effects in wildtype mice only.

Investigating the roles of bioactive lipids, including fatty acids and eicosanoids, during STm and other bacterial infections, helps to define the lipid-immune signaling axis in microbial infections. This research provides significant insights into how lipids mediate the induction and resolution of inflammation during bacterial infections. Given the alarming rise in multidrug-resistant pathogens, there is an urgent need to develop new strategies for combatting bacterial infections. The present study, along with others, encourages the exploration of unique immunomodulatory techniques to address the growing threat of antibiotic resistance to public health.

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) [Grants R01 AI168550 (to V. Tam), R01 AI153325 and AI171568 (to C. Tükel)] and National Cancer Institute Core [Grant P30 CA 06927 (to A. Klein-Szanto)].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data presented in the study are deposited in the MetaboLights repository, accession number MTBLS10099.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/19490976.2024.2419567

References

- 1.CDC . Reports of selected salmonella outbreak investigations. [cited 2023 Oct 1]. https://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/outbreaks.html.

- 2.Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM.. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(1):7–21. doi: 10.3201/eid1701.p11101. PubMed PMID: 21192848; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3375761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fàbrega A, Vila J. Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium skills to succeed in the host: virulence and regulation. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26(2):308–341. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00066-12. PubMed PMID: 23554419; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3623383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohmann EL. Nontyphoidal salmonellosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32(2):263–269. doi: 10.1086/318457. Epub 20010115. PubMed PMID: 11170916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vazquez-Torres A, Fang FC. Cellular routes of invasion by enteropathogens. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3(1):54–59. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00051-x. PubMed PMID: 10679413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jepson MA, Clark MA. The role of M cells in Salmonella infection. Microbes Infect. 2001;3(14–15):1183–1190. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01478-2. PubMed PMID: 11755406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, Angulo FJ, Kirk M, O’Brien SJ, Jones T, Fazil A, Hoekstra R. The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(6):882–889. doi: 10.1086/650733. PubMed PMID: 20158401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis EA, Norris PC. Eicosanoid storm in infection and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(8):511–523. doi: 10.1038/nri3859. PubMed PMID: 26139350; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4606863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cytochrome P450 Eicosanoids are Activators of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor . 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Grygiel-Górniak B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and their ligands: nutritional and clinical implications–a review. Nutr J. 2014;13(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-17. Epub 20140214. PubMed PMID: 24524207; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3943808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Carvalho CCCR, Caramujo MJ. The various roles of fatty acids. Molecules. 2018;23(10). 2583. doi: 10.3390/molecules23102583. Epub 20181009. PubMed PMID: 30304860; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6222795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):677–686. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015. PubMed PMID: 15530839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Odegaard JI, Chawla A. The immune system as a sensor of the metabolic state. Immunity. 2013;38(4):644–654. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.001. PubMed PMID: 23601683; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3663597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pearce EL, Pearce EJ. Metabolic pathways in immune cell activation and quiescence. Immunity. 2013;38(4):633–643. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.005. PubMed PMID: 23601682; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3654249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vats D, Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, Zhang L, Smith KL, Morel CR, Greaves DR, Murray PJ, Chawla A. Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1β attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation. Cell Metab. 2006;4(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.011. PubMed PMID: 16814729; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1904486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang SC, Everts B, Ivanova Y, O’Sullivan D, Nascimento M, Smith AM, Beatty W, Love-Gregory L, Lam WY, O’Neill CM, et al. Cell-intrinsic lysosomal lipolysis is essential for alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(9):846–855. Epub 20140803. doi: 10.1038/ni.2956. PubMed PMID: 25086775; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4139419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houten SM, Wanders RJ. A general introduction to the biochemistry of mitochondrial fatty acid β-oxidation. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2010;33(5):469–477. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9061-2. Epub 20100302. PubMed PMID: 20195903; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2950079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nomura M, Liu J, Rovira II, Gonzalez-Hurtado E, Lee J, Wolfgang MJ, Finkel T. Fatty acid oxidation in macrophage polarization. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(3):216–217. doi: 10.1038/ni.3366. PubMed PMID: 26882249; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6033271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dreyer C, Keller H, Mahfoudi A, Laudet V, Krey G, Wahli W. Positive regulation of the peroxisomal beta-oxidation pathway by fatty acids through activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR). Biol Cell. 1993;77(1):67–76. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(05)80176-5. PubMed PMID: 8390886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucarelli R, Gorrochotegui-Escalante N, Taddeo J, Buttaro B, Beld J, Tam V. Eicosanoid-activated PPARα inhibits NFκB-Dependent bacterial clearance during post-influenza superinfection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:881462. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.881462. Epub 20220704. PubMed PMID: 35860381; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9289478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penas F, Mirkin GA, Vera M, Cevey Á, González CD, Gómez MI, Sales ME, Goren NB. Treatment in vitro with PPARα and PPARγ ligands drives M1-to-M2 polarization of macrophages from T. cruzi-infected mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1852(5):893–904. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.12.019. Epub 20141231.PubMed PMID: 25557389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim YS, Lee HM, Kim JK, Yang CS, Kim TS, Jung M, Jin HS, Kim S, Jang J, Oh GT, et al. Ppar-α activation mediates innate host defense through induction of TFEB and Lipid catabolism. J Immunol. 2017;198(8):3283–3295. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601920. Epub 20170308. PubMed PMID: 28275133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor SJ, Winter SE, Leong JM. Salmonella finds a way: metabolic versatility of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium in diverse host environments. PLOS Pathog. 2020;16(6):e1008540. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008540. Epub 20200611. PubMed PMID: 32525928; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7289338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stapels DAC, Hill PWS, Westermann AJ, Fisher RA, Thurston TL, Saliba AE, Blommestein I, Vogel J, Helaine S. Salmonella persisters undermine host immune defenses during antibiotic treatment. Science. 2018;362(6419):1156–1160. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7148. PubMed PMID: 30523110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panagi I, Jennings E, Zeng J, Günster RA, Stones CD, Mak H, Jin E, Stapels DAC, Subari NZ, Pham THM, et al. Salmonella effector SteE converts the mammalian serine/threonine kinase GSK3 into a tyrosine kinase to direct macrophage polarization. Cell Host & Microbe. 2020;27(1):41–53.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.11.002. Epub 20191217. PubMed PMID: 31862381; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6953433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eisele NA, Ruby T, Jacobson A, Manzanillo PS, Cox JS, Lam L, Mukundan L, Chawla A, Monack D. Salmonella require the fatty acid regulator PPARδ for the establishment of a metabolic environment essential for long-term persistence. Cell Host & Microbe. 2013;14(2):171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.07.010. PubMed PMID: 23954156; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3785333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obeid LM, Linardic CM, Karolak LA, Hannun YA. Programmed cell death induced by ceramide. Science. 1993;259(5102):1769–1771. doi: 10.1126/science.8456305. PubMed PMID: 8456305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Taniguchi M, Okazaki T. Role of ceramide/sphingomyelin (SM) balance regulated through “SM cycle” in cancer. Cell Signal. 2021;87:110119. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2021.110119. Epub 20210819. PubMed PMID: 34418535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taniguchi M, Okazaki T. Ceramide/Sphingomyelin rheostat regulated by Sphingomyelin Synthases and chronic diseases in murine models. J Lipid Atheroscler. 2020;9(3):380–405. doi: 10.12997/jla.2020.9.3.380. Epub 20200729. PubMed PMID: 33024732; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7521967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young SA, Mina JG, Denny PW, Smith TK. Sphingolipid and ceramide homeostasis: potential therapeutic targets. Biochem Res Int. 2012;2012:248135. doi: 10.1155/2012/248135. Epub 20120209. PubMed PMID: 22400113; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3286894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dadsena S, Bockelmann S, Mina JGM, Hassan DG, Korneev S, Razzera G, Jahn H, Niekamp P, Müller D, Schneider M, et al. Ceramides bind VDAC2 to trigger mitochondrial apoptosis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1832. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09654-4. Epub 20190423. PubMed PMID: 31015432; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6478893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang X, Yang Y, Cai WQ, Lu Y. The relationship of sphingosine kinase 1 with pyroptosis provides a new strategy for tumor therapy. Front Immunol. 2020;11:574990. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.574990. Epub 20201002. PubMed PMID: 33123153; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7566665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu F, Zhang Y, Shi Y, Xiong K, Wang F, Yang J. Ceramide induces pyroptosis through TXNIP/NLRP3/GSDMD pathway in HUVECs. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(1):54. doi: 10.1186/s12860-022-00459-w. Epub 20221214. PubMed PMID: 36517743; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9749313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parisi LR, Li N, Atilla-Gokcumen GE. Very long chain fatty acids are functionally involved in necroptosis. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24(12):1445–54.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.08.026. Epub 20171012. PubMed PMID: 29033315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varga T, Czimmerer Z, Nagy L. PPARs are a unique set of fatty acid regulated transcription factors controlling both lipid metabolism and inflammation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812(8):1007–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.02.014. Epub 20110305. PubMed PMID: 21382489; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3117990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cummings LA, Wilkerson WD, Bergsbaken T, Cookson BT. In vivo, fliC expression by Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium is heterogeneous, regulated by ClpX, and anatomically restricted. Mol Microbiol. 2006;61(3):795–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05271.x. Epub 20060627. PubMed PMID: 16803592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaner NC, Campbell RE, Steinbach PA, Giepmans BN, Palmer AE, Tsien RY. Improved monomeric red, orange and yellow fluorescent proteins derived from Discosoma sp. red fluorescent protein. Nat Biotechnol. 2004;22(12):1567–1572. doi: 10.1038/nbt1037. Epub 20041121. PubMed PMID: 15558047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barthel M, Hapfelmeier S, Quintanilla-Martínez L, Kremer M, Rohde M, Hogardt M, Pfeffer K, Rüssmann H, Hardt W-D. Pretreatment of mice with streptomycin provides a Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium colitis model that allows analysis of both pathogen and host. Infect Immun. 2003;71(5):2839–2858. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2839-2858.2003. PubMed PMID: 12704158; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC153285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosas M, Osorio F, Robinson MJ, Davies LC, Dierkes N, Jones SA, Reis e Sousa C, Taylor PR. Hoxb8 conditionally immortalised macrophage lines model inflammatory monocytic cells with important similarity to dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41(2):356–365. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040962. Epub 20110111. PubMed PMID: 21268006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang GG, Calvo KR, Pasillas MP, Sykes DB, Häcker H, Kamps MP. Quantitative production of macrophages or neutrophils ex vivo using conditional Hoxb8. Nat Methods. 2006;3(4):287–293. doi: 10.1038/nmeth865. PubMed PMID: 16554834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berger J, Moller DE. The mechanisms of action of PPARs. Annu Rev Med. 2002;53(1):409–435. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.104018. PubMed PMID: 11818483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tam VC. Lipidomic profiling of bioactive lipids by mass spectrometry during microbial infections. Semin Immunol. 2013;25(3):240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2013.08.006. Epub 20130929. PubMed PMID: 24084369; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3885417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tam VC, Suen R, Treuting PM, Armando A, Lucarelli R, Gorrochotegui-Escalante N, Diercks AH, Quehenberger O, Dennis EA, Aderem A, et al. PPARα exacerbates necroptosis, leading to increased mortality in postinfluenza bacterial superinfection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(27):15789–15798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2006343117. Epub 20200624. PubMed PMID: 32581129; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC7355019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quehenberger O, Armando AM, Dennis EA. High sensitivity quantitative lipidomics analysis of fatty acids in biological samples by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1811(11):648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.07.006. Epub 20110720. PubMed PMID: 21787881; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3205314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sterz K, Scherer G, Ecker J. A simple and robust UPLC-SRM/MS method to quantify urinary eicosanoids. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(5):1026–1036. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D023739. Epub 20120214. PubMed PMID: 22338011; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3329380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bligh EG, Dyer WJ. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J Biochem Physiol. 1959;37(8):911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. PubMed PMID: 13671378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsugawa H, Ikeda K, Takahashi M, Satoh A, Mori Y, Uchino H, Okahashi N, Yamada Y, Tada I, Bonini P, et al. A lipidome atlas in MS-DIAL 4. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(10):1159–1163. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0531-2. Epub 20200615. PubMed PMID: 32541957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pluskal T, Castillo S, Villar-Briones A, Oresic M. Mzmine 2: modular framework for processing, visualizing, and analyzing mass spectrometry-based molecular profile data. BMC Bioinf. 2010;11(1):395. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-395. Epub 20100723. PubMed PMID: 20650010; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2918584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Melo RC, D’Avila H, Wan HC, Bozza PT, Dvorak AM, Weller PF. Lipid bodies in inflammatory cells: structure, function, and current imaging techniques. J Histochem Cytochem. 2011;59(5):540–556. doi: 10.1369/0022155411404073. Epub 20110323. PubMed PMID: 21430261; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3201176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Divakaruni AS, Hsieh WY, Minarrieta L, Duong TN, Kim KKO, Desousa BR, Andreyev AY, Bowman CE, Caradonna K, Dranka BP, et al. Etomoxir inhibits macrophage polarization by disrupting CoA homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2018;28(3):490–503.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.001. Epub 20180628. PubMed PMID: 30043752; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6125190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Treede I, Braun A, Sparla R, Kühnel M, Giese T, Turner JR, Anes E, Kulaksiz H, Füllekrug J, Stremmel W, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of phosphatidylcholine. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(37):27155–27164. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704408200. Epub 20070718. PubMed PMID: 17636253; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2693065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lichtenberger LM. The hydrophobic barrier properties of gastrointestinal mucus. Annu Rev Physiol. 1995;57(1):565–583. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003025. PubMed PMID: 7778878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bengmark S, Jeppsson B. Gastrointestinal surface protection and mucosa reconditioning. JPEN J Parenter Enter Nutr. 1995;19(5):410–415. doi: 10.1177/0148607195019005410. PubMed PMID: 8577022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stremmel W, Merle U, Zahn A, Autschbach F, Hinz U, Ehehalt R. Retarded release phosphatidylcholine benefits patients with chronic active ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2005;54(7):966–971. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.052316. PubMed PMID: 15951544; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC1774598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nervi F. Significance of biliary phospholipids for maintenance of the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier and hepatocellular integrity. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(6):1265–1267. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70380-5. PubMed PMID: 10833502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Byndloss MX, Olsan EE, Rivera-Chávez F, Tiffany CR, Cevallos SA, Lokken KL, Torres TP, Byndloss AJ, Faber F, Gao Y, et al. Microbiota-activated ppar-γ signaling inhibits dysbiotic enterobacteriaceae expansion. Science. 2017;357(6351):570–575. doi: 10.1126/science.aam9949. PubMed PMID: 28798125; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5642957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dias SP, Brouwer MC, van de Beek D, Richardson AR. Sex and gender differences in bacterial infections. Infect Immun. 2022;90(10):e0028322. doi: 10.1128/iai.00283-22. Epub 20220919. PubMed PMID: 36121220; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC9584217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pace S, Sautebin L, Werz O. Sex-biased eicosanoid biology: impact for sex differences in inflammation and consequences for pharmacotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017;145:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.06.128. Epub 20170622. PubMed PMID: 28647490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Park HJ, Choi JM. Sex-specific regulation of immune responses by PPARs. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49(8):e364. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.102. Epub 20170804. PubMed PMID: 28775365; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5579504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilson RP, Tursi SA, Rapsinski GJ, Medeiros NJ, Le LS, Kotredes KP, Patel S, Liverani E, Sun S, Zhu W, et al. STAT2 dependent type I interferon response promotes dysbiosis and luminal expansion of the enteric pathogen salmonella typhimurium. PLOS Pathog. 2019;15(4):e1007745. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007745. Epub 20190422. PubMed PMID: 31009517; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6513112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rakhshandehroo M, Knoch B, Müller M, Kersten S. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha target genes. PPAR Res. 2010;2010:1–20. doi: 10.1155/2010/612089. Epub 20100926. PubMed PMID: 20936127; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2948931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tanaka K, Hirai H, Takano S, Nakamura M, Nagata K. Effects of prostaglandin D2 on helper T cell functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;316(4):1009–1014. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.02.151. PubMed PMID: 15044085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ide T, Egan K, Bell-Parikh LC, FitzGerald GA. Activation of nuclear receptors by prostaglandins. Thromb Res. 2003;110(5–6):311–315. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(03)00418-3. PubMed PMID: 14592554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sheppe AEF, Kummari E, Walker A, Richards A, Hui WW, Lee JH, Mangum L, Borazjani A, Ross MK, Edelmann MJ. PGE2 augments inflammasome activation and M1 polarization in macrophages infected with. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2447. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02447. Epub 20181031. PubMed PMID: 30429830; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC6220063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sheppe AEF, Edelmann MJ, Ottemann KM. Roles of eicosanoids in regulating inflammation and neutrophil migration as an innate host response to bacterial infections. Infect Immun. 2021;89(8):e0009521. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00095-21. Epub 20210715. PubMed PMID: 34031130; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8281227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buckner MM, Antunes LC, Gill N, Russell SL, Shames SR, Finlay BB, Gorvel J-P. 15-Deoxy-Δ12,14-prostaglandin J2 inhibits macrophage colonization by Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(7):e69759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069759. Epub 20130726. PubMed PMID: 23922794; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3724865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bowman CC, Bost KL. Cyclooxygenase-2-mediated prostaglandin E2 production in mesenteric lymph nodes and in cultured macrophages and dendritic cells after infection with Salmonella. J Immunol. 2004;172(4):2469–2475. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.4.2469. PubMed PMID: 14764719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Afonso PV, Janka-Junttila M, Lee YJ, McCann CP, Oliver CM, Aamer KA, Losert W, Cicerone M, Parent C. LTB4 is a signal-relay molecule during neutrophil chemotaxis. Dev Cell. 2012;22(5):1079–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.02.003. Epub 20120426. PubMed PMID: 22542839; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC4141281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kiarely Souza E, Pereira-Dutra FS, Rajão MA, Ferraro-Moreira F, Goltara-Gomes TC, Cunha-Fernandes T, Santos JDC, Prestes EB, Andrade WA, Zamboni DS, et al. Lipid droplet accumulation occurs early following Salmonella infection and contributes to intracellular bacterial survival and replication. Mol Microbiol. 2022;117(2):293–306. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14844. Epub 20211201. PubMed PMID: 34783412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liu Y, Yang S, Chen X, Ke M. Comparison of different lipid staining methods in human meibomian gland epithelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2023;236:109658. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2023.109658. Epub 20230922. PubMed PMID: 37741430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saka HA, Valdivia R. Emerging roles for lipid droplets in immunity and host-pathogen interactions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28(1):411–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-153958. Epub 20120511. PubMed PMID: 22578141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang D, Dubois RN. Eicosanoids and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(3):181–193. doi: 10.1038/nrc2809. Epub 20100219. PubMed PMID: 20168319; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC2898136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harhala M, Gembara K, Miernikiewicz P, Owczarek B, Kaźmierczak Z, Majewska J, Nelson DC, Dąbrowska K. DNA dye sytox green in detection of bacteriolytic activity: high speed, precision and sensitivity demonstrated with endolysins. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:752282. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.752282. Epub 20211025. PubMed PMID: 34759903; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC8575126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang Y, Rao E, Zeng J, Hao J, Sun Y, Liu S, Sauter ER, Bernlohr DA, Cleary MP, Suttles J, et al. Adipose fatty acid binding protein promotes saturated fatty acid–induced macrophage cell death through enhancing ceramide production. J Immunol. 2017;198(2):798–807. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601403. Epub 20161205. PubMed PMID: 27920274; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC5225136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thon L, Möhlig H, Mathieu S, Lange A, Bulanova E, Winoto-Morbach S, Schütze S, Bulfone-Paus S, Adam D. Ceramide mediates caspase-independent programmed cell death. Faseb J. 2005;19(14):1945–1956. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3726com. PubMed PMID: 16319138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Monack DM, Navarre WW, Falkow S. Salmonella-induced macrophage death: the role of caspase-1 in death and inflammation. Microbes Infect. 2001;3(14–15):1201–1212. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(01)01480-0. PubMed PMID: 11755408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miao EA, Rajan JV. Salmonella and caspase-1: a complex interplay of detection and evasion. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:85. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00085. Epub 20110425. PubMed PMID: 21833326; PubMed Central PMCID: PMCPMC3153046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Djouadi F, Brandt JM, Weinheimer CJ, Leone TC, Gonzalez FJ, Kelly DP. The role of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR alpha) in the control of cardiac lipid metabolism. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids. 1999;60(5–6):339–343. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(99)80009-x. PubMed PMID: 10471118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]