Abstract

Background

Although the exact role of mitophagy in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) caused by type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) remains controversial, recent studies revealed inhibition of mitophagy exacerbates cardiac injury in DCM. The zinc transporter ZIP7 has been reported to be upregulated by high glucose in cardiomyocytes and ZIP7 upregulation leads to inhibition of mitophagy in mouse hearts in the setting of ischemia/reperfusion. Nevertheless, little is known about the role of ZIP7 and its relationship with mitophagy in DCM caused by T2DM.

Methods

T2DM was induced with high-fat diet (HFD) and streptozotocin. The cardiac-specific ZIP7 conditional knockout (ZIP7 cKO) mice were generated by adopting CRISPR/Cas9 system. Cardiac function was evaluated with echocardiography. Mitophagy was assessed by detecting mito-LC3II, mitoKeima, and mitoQC. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were detected with DHE and mitoB.

Results

ZIP7 was upregulated by T2DM in mouse hearts and ZIP7 cKO reduced mitochondrial ROS generation in mouse hearts with T2DM. Mitophagy was suppressed by T2DM in mouse hearts, which was prevented by ZIP7 cKO. T2DM inhibited PINK1 and Parkin accumulation in cardiac mitochondria, an effect that was prevented by ZIP7 cKO, pointing to that ZIP7 upregulation mediates T2DM-induced suppression of mitophagy by inhibiting the PINK1/Parkin pathway. T2DM induced mitochondrial hyperpolarization and decrease of mitochondrial Zn2+ and this was blocked by ZIP7 cKO, indicating that upregulation of ZIP7 leads to mitochondrial hyperpolarization by reducing Zn2+ within mitochondria. Finally, ZIP7 cKO prevented cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis caused by T2DM.

Conclusions

ZIP7 upregulation mediates the inhibition of mitophagy by T2DM in mouse hearts by suppressing the PINK1/Parkin pathway. Reduction of mitochondrial Zn2+ due to upregulation of ZIP7 accounts for the inhibition of the PINK1/Parkin pathway. Prevention of ZIP7 upregulation is essential for the treatment of T2DM-induced cardiomyopathy.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12933-024-02499-2.

Keywords: ZIP7, Mitophagy, T2DM, Cardiomyopathy, PINK1/Parkin pathway

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a global health problem and patients with T2DM often develop diabetic cardiomyopathy (DCM) characterized by the left ventricular hypertrophy, diastolic dysfunction, fibrosis, and cell signaling abnormalities [1]. DCM occurs in the absence of coronary diseases and hypertension in patients with T2DM and results in heart failure [2]. While various factors such as inflammation, oxidative stress, and dysregulation of metabolism have been proposed to contribute to the pathogenesis of DCM, the precise mechanism remains unclear.

Studies have demonstrated that impairments of the mitochondrial structure and function may contribute to the pathogenesis of DCM [1, 3]. Dysfunctional mitochondria often leads to increased reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and triggers a vicious cycle of mitochondrial damage and production of ROS [4]. Thus, a timely removal of dysfunctional or damaged mitochondria via a selective autophagy, called mitophagy [5], is critical for the protection of cardiomyocytes in the setting of DCM [6], although the role of mitophagy in DCM caused by T2DM remains controversial [7]. In a mouse model of obesity cardiomyopathy caused by high-fat diet (HFD), mitophagy was activated during the early phase of HFD consumption through the conventional Atg7-dependent autophagy and deletion of Atg7 or Parkin aggravated HFD-induced mitochondrial and cardiac dysfunction, indicating that mitophagy is critical for the maintenance of cardiac function in the setting of HFD-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy [8]. In support, activation of mitophagy by TAT-Beclin1 attenuated HFD-induced cardiac dysfunction [8].

The zinc transporter ZIP7 (Slc39a7), initially found in ER and Golgi apparatus, plays an important role in cellular zinc homeostasis by regulating the movement of Zn2+ from intracellular vesicles to the cytosol [9]. A recent study adopting Western blotting and imaging technique demonstrated that ZIP7 is localized cardiac mitochondria [10], indicating that ZIP7 may play a role in mitochondrial Zn2+ homeostasis. ZIP7 plays a role in B cell development [11] and breast cancer [12]. A recent study demonstrated that ZIP7 is upregulated in cardiomyocytes of rats treated with streptozotocin or high-glucose and accounts for T1DM-induced cardiac dysfunction [13]. In contrast, ZIP7 expression is decreased in the skeletal muscle of HFD-fed mice, although the exact role of ZIP7 was not determined in T2DM [14]. Recently we have demonstrated that upregulation of ZIP7 contributes to the pathogenesis of ischemia/reperfusion injury in mouse hearts by inhibiting mitophagy [15]. However, whether ZIP7 plays a role in DCM remains to be explored.

The purpose of this study was to determine if ZIP7 contributes to the pathogenesis of DCM by regulating mitophagy in T2DM mice. We identified that ZIP7 was upregulated in the heart of T2DM mice and the cardiac-specific knockdown of ZIP7 (ZIP7 cKO) promoted mitophagy leading to an attenuation of mitochondrial ROS generation. T2DM induced DCM as indicated by cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis, which was prevented by ZIP7 cKO. ZIP7 inhibits mitophagy by preventing Parkin recruitment to mitochondria through mitochondrial hyperpolarization.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and genome editing

HL-1 and AC16 cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) and 100 U penicillin/streptomycin (Solarbio) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2–95% air atmosphere. Cells were seeded in 6-well plates for 24 h before transfection and were 60% confluent at transfection. Adult cardiomyocytes were isolated from C57BL/6J mice. Cells were cultured in M199 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin in a 95% O2 and 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Cells were exposed to either normal glucose (NG) or high glucose (HG) culture medium. HG culture medium was made using DMEM medium (5.5 mM glucose) supplemented with D-glucose to a final concentration of 35 mM. To generate the ZIP7 gene knockout (ZIP7 KO) cell line, HL-1 cells were transfected with lentiCRISPRv2 plasmid with a single guide RNA sequence (GCGTGGCTGTGTCCGTGCGCG) using Lipofectamine 3000. This single guide RNA sequence targets exon 5 of Slc39a7. After 72 h of transfection, positive cells were sorted by puromycin and seeded at a 96-wells plate to isolate single colonies. Clones were picked when colonies were ~ 100 cells. Colonies were expanded and screened for ZIP7 KO based on disruption of DNA sequence and confirmed by Western blotting.

Animals

Male C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks) were obtained from the Institute of Laboratory Animal Science, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Beijing, China). All the treatments and subsequent analyses were conducted in a blind fashion. All mice were housed in standard conditions (temperature 22 ± 1 °C and 12 h light/dark cycle) with free access to a standard rodent diet and tap water. All the animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Eighth Edition) and were approved by the Tianjin Medical University Animal Care and Use Committee.

Generation of Slc39a7 (ZIP7) cKO mice

The cardiac-specific Slc39a7 conditional knockout mice (ZIP7 cKO) were made in corporation with Nanjing BioMedical Research Institute of Nanjing University (NBRI) by adopting the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Transcript Slc39a7-201 is selected for the presentation of the recommended strategy. The correct integration of cre and loxP sites, and the successful frameshift mutation of Slc39a7 gene were confirmed by PCR analysis with the primers listed below:

cre-forward: ATACCGGAGATCATGCAAGC.

cre-reverse: AGGTGGACCTGATCATGGAG.

loxP-forward: GTGATGCGTTCCTCCACCTC.

loxP-reverse: CGTGGTGAGAATGAGGTTCTGC.

Slc39a7-forward: GAAGCTCCATCTTTGCCTTCTG.

Slc39a7-reverse: TTAGGTGGGAGCAGTGTTAAGG.

Tamoxifen (Sigma, T5648) was dissolved in corn oil with ethanol (100%) to a concentration of 10 mg/mL. Tamoxifen solution was given (75 mg/kg, i.p.) once daily for 3 consecutive days.

T2DM mouse model

The T2DM model was established as described elsewhere [16]. Mice were randomly divided into the normal control (NC) group and the T2DM model group. The NC group was fed an ordinary maintenance diet. The T2DM model group was fed a customized high-fat diet. Both groups were given pure water. After 8 weeks, the mice were allowed to fast for 12 h and mice in the T2DM model group were intraperitoneally injected with streptozotocin dissolved in sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.2–4.5, 100 mg/kg). Mice in the NC group were injected with sodium citrate buffer solution alone. After the intervention, fasting glucose levels were measured. A fasting glucose level of 11.1 mmol/L indicates a successful T2DM model establishment. After the successful modeling, diabetic mice were fed with the high fat diet for 8 weeks to induce diabetic cardiomyopathy (Fig. S1A).

Isolation of adult mouse cardiomyocytes

Mouse cardiomyocytes were isolated as our previous report [15]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 5% chloral hydrate. Hearts were removed rapidly and mounted on a Langendorff apparatus. Hearts were perfused in a constant perfusion pressure (90 cm H2O) with perfusion buffer for 4–5 min. When there was ~ 10 mL of perfusion buffer remaining, hearts were perfused with 30 mg collagenase and 0.6 mg protease. After 2 min, remaining buffer in the reservoir was discarded. Hearts were perfused with 6.4 µL 0.25 mmol/L CaCl2 for 15–20 min. Hearts were cut into 2 pieces. Then the hearts were aspirated using a transfer pipette. The supernatants containing dispersed cells were removed into a centrifuge tube through a cell strainer, and centrifuge at 500 rpm for 1 min. The supernatants were discarded, and the cell pellets were resuspended with 7 mL of perfusion buffer. Cells were plated in dishes (pre-coated with L-laminin) with M199 and placed in an incubator. For imaging experiments, each group included 6–7 mice for cardiomyocytes isolation and isolated cells were placed in 4–5 dishes. Six to 8 cells were randomly selected for measurements of fluorescence and the mean fluorescence intensity was calculated with individual values obtained from these cells.

siRNA transfection in vivo

Male C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks) were injected with 1 OD PINK1 siRNA dissolved in 200 µL saline via the tail vein. Injection was repeated at 8 and 24 h after the first injection. Experiments were conducted 48 h after the first injection. Control mice were injected with siNC (negative control of siRNA).

Western blotting analysis

Cardiac cell and tissue homogenates were prepared using RIPA buffer. Equal amounts of protein from cells were separated by SDS–PAGE (10% polyacrylamide gels) and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose. Membranes were blocked with 5% defatted milk in Tris-buffered saline, pH 7.6, containing 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST). Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 ℃ Each primary antibody binding was detected with an anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibody. Proteins were visualized by the enhanced ECL method. The image was captured with Biospectrum Imaging System (UVP, Upland, CA). Protein expression levels were calculated as the ratio of target protein to GAPDH or COX IV.

Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) in cardiac cells

Mitochondrial membrane potential was measured using either TMRE or JC-1. Cells were stained with JC-1(5 mg/ml) or TMRE(0.5 µmol/L) for 15 min at 37 °C and washed twice with PBS. Fluorescence was detected with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The green fluorescence of JC-1 monomer was imaged through a 488 nm filter, whereas the red fluorescence of JC-1 aggregation was imaged through a 559 nm filter. The ratio between the red and green florescence was considered a quantitative index of MMP. TMRE fluorescence was excited at 550 nm and collected at 574 nm. Plane images with confocal microscopy were obtained without Z-stack. Image J was used to quantify DHE fluorescence intensity in cardiac cells.

Measurement of cardiac ROS

Dihydroethidium (DHE) was used to detect cardiac ROS production. Cardiomyocytes were incubated with 5 µmol/L DHE at 37 °C for 20 min and avoided from light. After washing with PBS, images were captured using a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1200).

Measurement of mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) levels in vivo

H2O2 levels were measured in mice using the MitoB probe. MitoB can be targeted at the mitochondrial matrix and oxidized to MitoP by mitochondrial H2O2. Both MitoB and MitoP are quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometer (LC–MS/MS). The ratio of MitoP/MitoB can be used to assess the level of mitochondrial H2O2. Mice were injected with MitoB (0.8 µmol/kg). After experiments, hearts were removed and were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80 °C for subsequent extraction and quantification of MitoB and MitoP. To extract MitoB and MitoP, the samples were homogenized in a 2.0 mL tube with 500 µL 60% ACN/0.1% FA. The homogenate was spiked with isotope IS (100 pmol of d15-MitoB and 50 pmol of d15-MitoP), vortexed 30 s, and centrifuged 10 min at 16,000 g. The supernatant was transferred to a fresh tube and the pellet extracted with a further 500 µL 60% ACN/0.1% FA, which was pooled with the first supernatant. The supernatants were then centrifuged 10 min at 16,000 g, filtered through a 0.22 μm PVDF membrane into a fresh tube. Samples were dried under vacuum using a Savant SpeedVac 2–3 h. The dried samples were resuspended in 150 µL 20% ACN/0.1% FA by vortexing for 5 min. Finally, the samples were centrifuged 10 min at 16,000 g, and 120 µL was transferred to an autosampler vial. The samples were then analyzed by LC–MS/MS. For all experiments, a standard curve (R2 > 0.99) was prepared to calculate MitoB and MitoP concentration.

Isolation of mitochondrial fractions

Mitochondrial fractions were isolated by differential centrifugation via a cell mitochondria isolation kit or a tissue mitochondria isolation kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Measurement of intracellular free Zn2+

Free Zn2+ concentrations in mouse cardiomyocytes were detected with Zinpyr-1 (5 µmol/L, ChemCruz) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Green fluorescence was determined with a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1200).

Measurement of mitochondrial Zn2+ concentrations in cardiac tissue

Mitochondrial Zn2+ levels were measured using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICPOES, Perkin Elmer, USA) at a wavelength of 206.200 nm. Cardiac mitochondria were digested using 65% nitric acid at 120 °C. Standard curve of Zn2+ concentration was set up using a multi-element standard solution (Perkin Elmer, USA).

Detection of mitophagy in vivo

Mice were injected with 17 µg mito QC plasmid (MRC PPU) via the tail vein. Mice were perfused with PBS until blood runs clear and switched to 3.7% formaldehyde in 200 mM HEPES at pH 7.0. Hearts were rapidly excised and stored at 4 °C overnight. Fixed tissues were washed extensively in PBS at 4 °C, before dehydration with 30% sucrose. The tissues were embedded in OCT and were flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The tissues were sectioned at 7 μm thickness on a cryostat and placed on glass slides. After washing with PBS, the sections were stained with DAPI. Images were captured using a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1200). Image J was used to quantify the mCherry fluorescence.

Mitophagy assay with mKeima

Mice were injected with 17 µg mKeima plasmid via the tail vein. Cardiomyocytes were isolated 10 h after the injection. Measurements of lysosomal mKeima were made using a confocal microscope (Olympus, FV1200) at 488 nm (pH 7) and 561 nm (pH 4). The FlowJ software was used to assess mitophagy.

Histological staining

Heart samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and were embedded in paraffin and sliced into 7 μm thick sections. The sections were stained with haematoxylin & eosin (HE) or Masson’s trichrome. The morphological changes and collagen content of the cardiac tissues were observed with an optical microscope.

Echocardiography

Mice were placed supine on the echocardiograph table, and an isoflurane chamber was connected to the nose and mouth. Using Vevo770 ultrasonic instrument, M400 probe was selected for M ultrasonic monitoring. After the outflow tract was detected by the probe, the probe was placed into the long and short axis of the left ventricle of the mice, and ejection fraction (EF), shortening fraction (FS), left ventricular end-diastolic anterior wall thickness (LVAWD), and left ventricular end-diastolic posterior wall thickness (LVPWD) were detected by LV Trace.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total mRNA was isolated using Trizol reagent and RNA was quantified with NanoDrop (ThermoFisher). Reverse transcription (RT) was performed to convert RNA into cDNA by using the reverse transcriptase. DEPC (4 µl), MgCl2 (4.5 µl), dNTP Mix (1 µl), RRI (0.5 µl), 5x buffer (4 µl), and RT (1 µl) were used for the reverse transcription. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using 2x EvaGreen qPCR Master Mix (abm, Richmond, CA) with a CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, CA, USA). Reagents used for quantitative PCR included DEPC (3.5 µl), cDNA (1 µl), EvaGreen 2x mix (5 µl), the forward primer (0.3 µl), and the reverse primer (0.3 µl). The primer pairs used are as follows.

ZIP7:

F: TGTTGGTAAAGGTATCGGGGC.

R: ATGGTCATCACGCGGCTC.

GAPDH:

F: CGTGCCGCCTGGAGAAACCTG.

R: AGAGTGGGAGTTGCTGTTGAAGTCG.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± S.E. Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA with the Tukey’s test was used to test for differences between groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

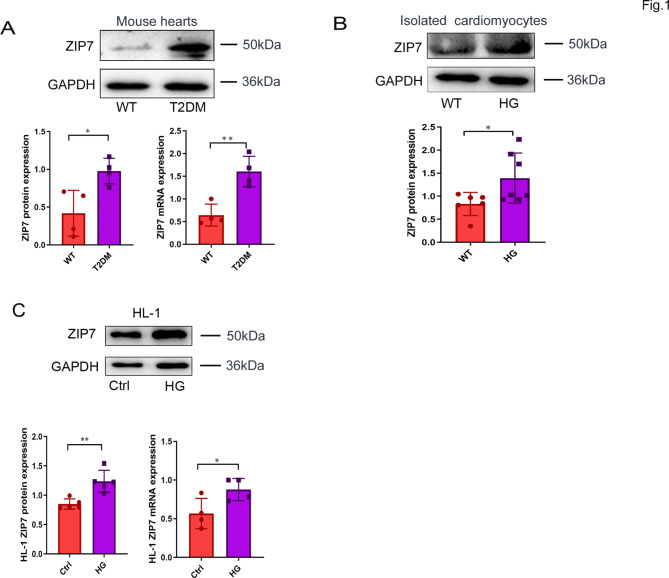

ZIP7 is upregulated by both T2DM and high glucose (HG)

To test if ZIP7 expression is altered by T2DM, we measured its protein expression in mouse hearts in vivo and in cardiac cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, ZIP7 mRNA and protein expression was markedly increased in T2DM mouse hearts. Likewise, ZIP7 expression was also upregulated in isolated mouse cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1B), HL-1 cells (Fig. 1C), and AC16 cells (Fig. S1E) exposed to 35 mM glucose for 48 h. These results indicate that ZIP7 may play a role in T2DM-induced heart disease.

Fig. 1.

ZIP7 expression in mouse hearts and cardiac cells. A ZIP7 protein and mRNA expression in mouse heats. T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus. n = 4 mice per group. B ZIP7 protein expression in primary cardiomyocytes. Cardiomyocytes were treated with high glucose (35 mM, HG) for 4 h. n = 6 mice per group. C, D ZIP7 protein and mRNA expression in HL-1 cells. Cell were treated with 35 mM glucose for 48 h. n = 4 experiments per group. Data are shown in mean ± s.e.m. P values were determined by Student’s t test. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01

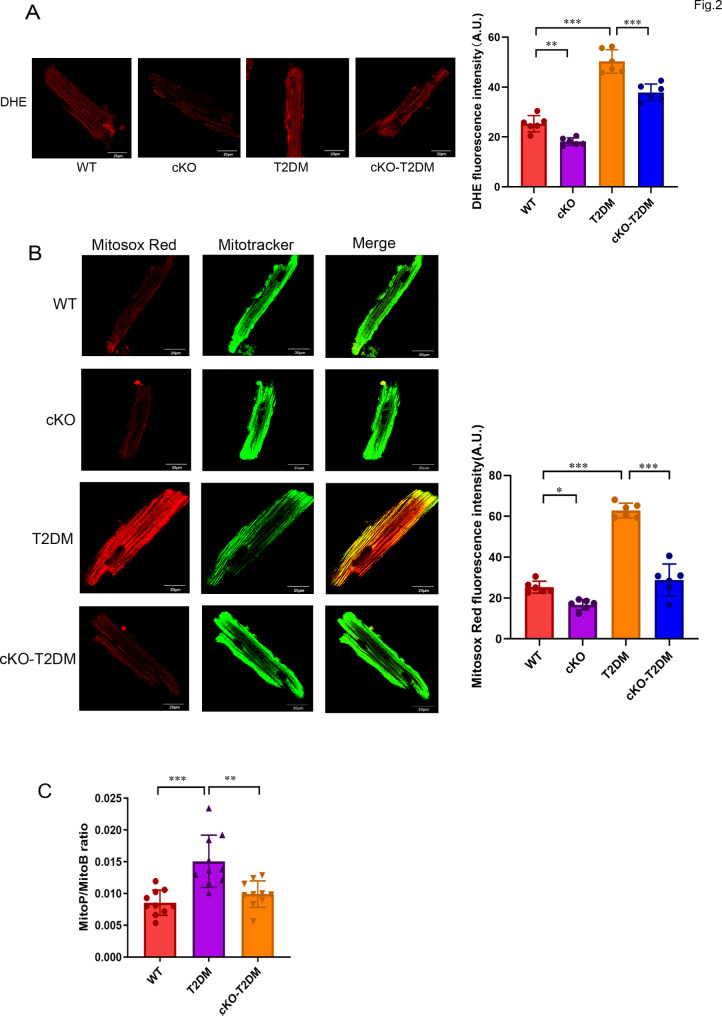

Mitochondrial ROS are increased in T2DM mouse hearts and deletion of ZIP7 reduces mitochondrial ROS

Oxidative stress due to augmented mitochondrial ROS generation has been proposed to contribute to the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy [1]. We thus tested if T2DM can alter mitochondrial ROS generation in the heart, and determined the role of ZIP7 in mitochondrial ROS generation. Figure 2A (left) shows that compared to mouse cardiomyocytes isolated from WT mice, cardiomyocytes from T2DM mice revealed a higher DHE fluorescence intensity, suggesting that T2DM enhances cardiomyocytes ROS generation. However, T2DM-induced ROS generation was prevented by the cardiac-specific ZIP7 knockout (cKO), as indicated by the decrease of DHE fluorescence (Fig. 2A), pointing to that ZIP7 may mediate ROS generation in T2DM-induced cardiomyopathy. Further experiments with Mitosox Red, a mitochondrial superoxide indicator, revealed that T2DM increased mitochondrial ROS generation, an effect that was reversed by ZIP7 cKO (Fig. 2B), suggesting that ZIP7 may contribute to mitochondrial ROS generation caused by T2DM in the heart. To corroborate this finding, we then detected mitochondrial H2O2 levels in mouse hearts in vivo using MitoB, a mitochondria-targeted spectrometric H2O2 probe [17]. Figure 2C shows that compared to the WT, the MitoP/MitoB ratio was markedly increased in T2DM hearts, which was reversed by ZIP7 cKO, indicating that ZIP7 mediates T2DM-induced mitochondrial H2O2 production in mouse hearts in vivo.

Fig. 2.

Deficiency of ZIP7 prevents increases of mitochondrial ROS generation caused by T2DM. A Confocal images of adult mouse cardiomyocytes loaded with DHE. n = 5–6 mice per group. Scale bars, 20 μm. B Confocal images of adult mouse cardiomyocytes loaded with Mitosox Red. n = 5–6 mice per group. Scale bars, 20 μm. C Mitochondrial H2O2 generation in mouse hearts measured by Mito B oxidation. n = 9–10 mice per group. Data are shown in mean ± s.e.m. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA or Student’s t test. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

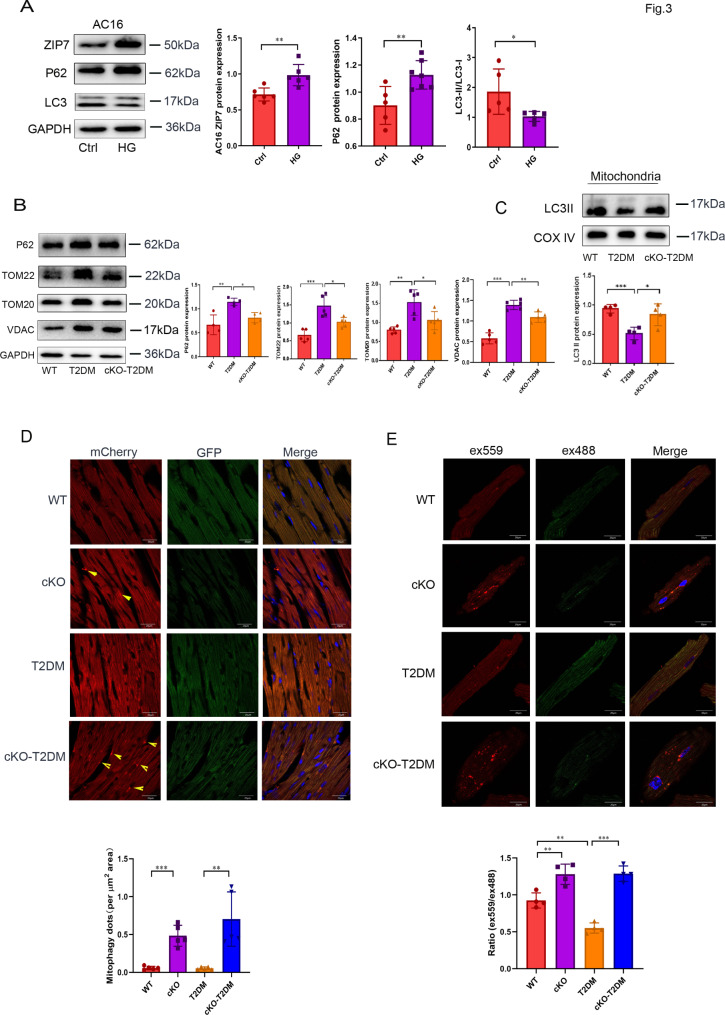

ZIP7 accounts for the inhibition of mitophagy by T2DM

Dysfunctional mitochondria trigger a vicious cycle of ROS generation and mitochondrial damage [4]. Mitophagy can selectively eliminate damaged or dysfunctional mitochondria thereby preventing mitochondrial ROS generation. Thus, suppression or inactivation of mitophagy can lead to increase of ROS generation from mitochondria. Accordingly, we tested if ZIP7 mediates the enhanced mitochondrial ROS generation due to T2DM by controlling mitophagy. Treatment of AC16 cells with a high dose of glucose (35 mM) not only increased ZIP7 protein expression but also downregulated autophagy as indicated by increased P62 expression but decreased the LC3II/I ratio (Fig. 3A). To determine if high glucose inhibits autophagy by altering the autophagic flow, we tested the effect of the autophagic flux inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (Baf) on the LC3II/I ratio. The ratio was decreased by high glucose and this was reversed by Baf, indicating high glucose downregulates autophagy by suppressing the autophagic flow (Fig. S1C). In mouse hearts, T2DM increased protein expression levels of P62, TOM22, TOM20, and VDAC, an effect that was inhibited by ZIP7 cKO, suggesting that T2DM suppresses mitophagy via ZIP7 in mouse hearts in vivo (Fig. 3B). In mitochondria isolated from mouse hearts, ZIP7 cKO also prevented the reduction of LC3II by T2DM (Fig. 3C). To confirm the role of ZIP7 in mitophagy in the setting of T2DM, we injected mitoQC plasmid into mice and detected its fluorescence intensity in cardiac tissue. MitoQC is a pH-sensitive mitochondrial fluorescence probe and displays red and green fluorescence during steady-state conditions, but the mCherry signal becomes stable when mitophagy is induced, because mitochondria are delivered to the lysosome where the GFP signal is quenched. Figure 3D shows that ZIP7 cKO increased mitophagy under physiological conditions or in the setting of T2DM. Further experiments with mKeima, a quantitative probe for mitophagy, demonstrated that T2DM downregulated mitophagy, which was reversed by ZIP7 cKO (Fig. 3E). All these data suggest that T2DM suppresses mitophagy in mouse hearts through ZIP7.

Fig. 3.

Deficiency of ZIP7 abates T2DM-induced downregulation of mitophagy. A Effect of HG on ZIP7, p62, and LC3 expression levels in AC16 cells. n = 5 experiments per group. B p62, TOM22, TOM20, and VDAC expression levels in mouse hearts. n = 5 mice per group. C LC3-II levels in mitochondria isolated from mouse hearts. n = 4–5 mice per group. D Effects of ZIP7 cKO on mitophagy. Mitophagy were assessed with confocal microscopy in cardiac sections loaded with MitoQC plasmid. n = 5 mice per group. Scale bar, 20 μm. E Confocal images of mouse cardiomyocytes loaded with Keima. n = 4 mice per group. Scale bar, 20 μm. Data are shown in mean ± s.e.m. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA or Student’s t test. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

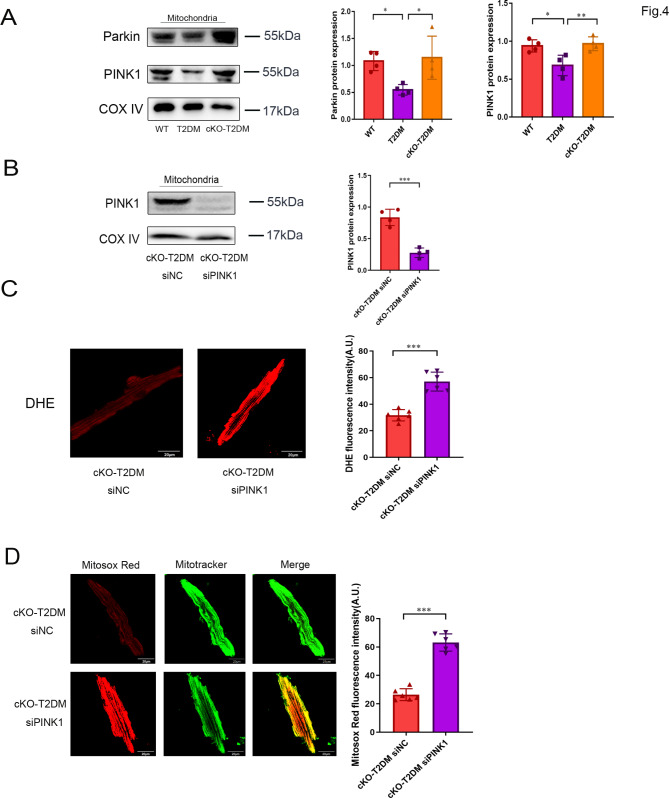

ZIP7 mediates T2DM inhibition of PINK1 and Parkin accumulation in mitochondria

The PINK1-Parkin pathway plays a major role in the regulation of mitophagy. To examine if ZIP7 mediates suppression of mitophagy in the setting of T2DM through the PINK1-Parkin pathway, we detected Parkin and PINK1 protein levels within mitochondria isolated from mouse hearts. Compared to WT, T2DM significantly reduced both Parkin and PINK1 protein levels in mitochondria, an effect that was reversed by ZIP7 cKO, indicating that ZIP7 may mediateT2DM-induced suppression of mitophagy via the PINK1-Parkin pathway (Fig. 4A). To confirm this finding, we then tested effect of PINK1 siRNA on ROS generation. ROS were measured in cardiomyocytes isolated 48 h after the injection of siRNA. The efficacy of siRNA was evaluated by Western blotting (Fig. 4B). As described above, ZIP7 cKO prevents T2DM-induced ROS generation. However, this effect of cKO was reversed by the PINK1 siRNA, as indicated by increased DHE fluorescence (Fig. 4C). Further experiments revealed that PINK1 siRNA markedly enhanced Mitosox Red fluorescence intensity in the cKO-T2DM mouse cardiomyocytes, indicating that Knockdown of ZIP7 alleviates T2DM-induced mitochondrial ROS generation through PINK1. Accordingly, this result supports the above finding that ZIP7 mediates T2DM-induced inhibition of mitophagy via the PINK1-Parkin pathway.

Fig. 4.

ZIP7 deficiency prevents T2DM-induced inhibition of mitochondrial recruitment of Parkin and ameliorates mitochondrial ROS generation in mouse hearts. A Parkin and PINK1 protein expression in mitochondria isolated from mouse hearts. n = 4 mice per group. B PINK1 protein expression in mitochondria. n = 4 mice per group. C DHE fluorescence in isolated mouse cardiomyocytes. n = 4 experiments per group Scale bar, 100 μm. D Mitosox fluorescence in isolated mouse cardiomyocytes. n = 6 mice per group. Data are shown in mean ± s.e.m. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

ZIP7 cKO prevents T2DM-induced mitochondrial hyperpolarization in mouse cardiomyocytes by increasing mitochondrial Zn2+

PINK1 is imported into mitochondria and is degraded by matrix processing peptidase and presenilin-associated rhomboid-like proteases. However, when mitochondria are depolarized, PINK1 is stabilized and accumulates on the outer mitochondrial membrane. Then, PINK1 recruits and activates Parkin in mitochondria leading to the initiation of mitophagy. Thus, it is not hard to understand that hyperpolarization of mitochondria will dampen PINK stabilization in mitochondria leading to inhibition of mitophagy. Accordingly, to explore the mechanism by which T2DM inhibits Parkin recruitment into mitochondria, we measured mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) in isolated mouse cardiomyocytes loaded with JC-1. As shown in Fig. 5A, T2DM increased the aggregate/monomer ratio of JC-1, indicating that T2DM induces mitochondrial hyperpolarization. However, this effect of T2DM was reversed by ZIP7 cKO, implying that ZIP7 accounts for T2DM-induced mitochondrial hyperpolarization. In support, additional experiments with TMRE also revealed that T2DM-induced hyperpolarization was nullified by ZIP7 cKO (Fig. 5B). ZIP7 is localized in mitochondria and its upregulation in mitochondria leads to a decrease in Zn2+ levels within mitochondria. Because Zn2+ is a cation, a decrease of Zn2+ in mitochondria due to upregulation of ZIP7 may result in mitochondrial hyperpolarization. Thus, we detected mitochondrial Zn2+ levels with Zinpyr-1 and Mitotracker in isolated mouse cardiomyocytes. Figure 5C shows that T2DM reduced mitochondrial Zn2+ levels, which was prevented by ZIP7 cKO, pointing to that ZIP7 is responsible for the reduction of mitochondrial Zn2+ caused by T2DM. In vitro study also demonstrated that treatment of mouse cardiomyocytes with 35 mM glucose reduced mitochondrial Zn2+ levels, which was revered by ZIP7 cKO (Fig. 5D). To corroborate these findings, we determined mitochondrial Zn2+ levels with ICPOES. In line with the above quantitative data, the mitochondrial Zn2+ content was markedly decreased by T2DM, which was prevented by ZIP7 cKO (Fig. 5E). To validate all these findings, we measured mitochondrial ZIP7 protein levels and found a significant increase of ZIP7 expression in mitochondria isolated from T2DM mouse hearts (Fig. 5F), implying that increases of ZIP7 in mitochondria reduces mitochondrial Zn2+ levels by promoting Zn2+ efflux from mitochondria to the cytosol.

Fig. 5.

A Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential with confocal microscopy in mouse cardiomyocytes loaded with JC-1. n = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 200 μm. B Measurement of mitochondrial membrane potential with confocal microscopy in mouse cardiomyocytes loaded with TMRE. n = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 200 μm. C Detection of Zn2+ with Zynpyr-1 in mouse cardiomyocytes. n = 6 mice per group. Scale bar, 20 μm D Detection of Zn2+ with Zynpyr-1 in mouse cardiomyocytes. Cardiomyocytes were treated with 35 mM glucose. n = 4 experiments per group. Scale bar, 20 μm E Detection of Zn2+ with ICPOES in mitochondria isolated from mouse hearts. n = 5–6 mice per group. F ZIP7 expression in mitochondria isolated from mouse hearts. n = 4 mice per group. Data are shown in mean ± s.e.m. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

ZIP7 cKO prevented cardiac dysfunction and fibrosis caused by T2DM

To further confirm the role of ZIP7, we tested the effects of ZIP7 cKO on cardiac function, hypertrophy, and fibrosis in the setting of T2DM. Echocardiographic studies showed that T2DM reduced ejection fraction (EF), fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular diastolic anterior wall thickness (LVAWD), and left ventricular diastolic posterior wall thickness (LVPWD), an effect that was inhibited by ZIP7 cKO, indicating that ZIP7 accounts for T2DM-induced cardiac dysfunction (Fig. 6A). Histopathological study with HE staining shows that cardiomyocytes were clearly striated and regularly arrayed in WT mouse myocardium (Fig. 6B, upper panel). In contrast, T2DM myocardium reveals disordered cell arrays, enlarged intercellular spaces, and ruptured fibers, which were improved by ZIP7 cKO, indicating that ZIP7 is responsible for T2DM-induced myocardial injury. Masson staining showed that compared to the WT, a marked accumulation of collagen in T2DM myocardium was noticeable, which was again prevented by ZIP7 cKO, suggesting that ZIP7 accounts for fibrosis caused by T2DM.

Fig. 6.

Deletion of ZIP7 prevents T2DM-induced cardiac dysfunction in mice. A Echocardiography of mice. EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractional shortening; LVAWD, left ventricular diastolic anterior wall thickness; LVPWD, left ventricular diastolic posterior wall thickness. n = 5 mice per group. B HE and Masson staining of cardiac sections. n = 4 experiments per group. Data are shown in mean ± s.e.m. P values were determined by one-way ANOVA. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001

Discussion

In this study we have demonstrated that cardiac ZIP7 is upregulated by T2DM and cKO of ZIP7 can reduce T2DM-induced mitochondrial ROS generation and DCM. Our study also revealed that ZIP7 upregulation is responsible for the inhibition of mitophagy by T2DM and ZIP7 cKO promotes mitophagy in the hearts of T2DM mice. We further found that ZIP7 cKO prevents the inhibition of mitophagy by T2DM by stimulating the PINK1-Parkin pathway through Zn2+ accumulation within mitochondria.

In addition to its major function to produce energy, mitochondria play important roles in cell death processes. Studies found structural and functional damages of mitochondria in DCM patients [3, 18, 19], indicating that mitochondrial impairment may play a role in DCM. Studies with animals further established that mitochondrial dysfunction and deformation underlie the mechanism by which DCM is induced by both T1DM and T2DM [20–22]. Importantly, impairment of mitochondria results in the ROS-induced ROS release [4] leading to increased oxidative stress and cardiac dysfunction in DCM [7, 23]. Accordingly, a timely removal of impaired mitochondria through mitophagy may prevent DCM. Studies have demonstrated that autophagy and mitophagy are inhibited in the hearts of T1DM, and activation of either autophagy or mitophagy could alleviate cardiac dysfunction, suggesting that mitophagy is protective against DCM caused by T1DM [24–26]. However, the experimental data regarding the activity of mitophagy in the hearts with T2DM are quite controversial. Some studies reported that cardiac mitophagy and autophagy were inhibited in mice fed with HFD [25, 27], but others showed the opposite [28, 29]. A recent study by Tong et al. demonstrated that autophagy and mitophagy in mouse hearts are activated during the early phase of HFD consumption, but this activation declines at the late phase [8]. They further found that inhibition of mitophagy with deletion of either atg7 or Parkin exacerbated cardiac dysfunction, whereas activation of mitophagy by injection of Tat-Beclin1 (TB1) prevented cardiac dysfunction, indicating that mitophagy can protect the heart from DCM. The same group further demonstrated that alternative autophagy is activated during the chronic phase of HFD consumption, which protects the heart from DCM [30]. In the current study, we found that mitophagy was inhibited by both high glucose and T2DM, and activation of mitophagy with ZIP7 cKO alleviated cardiac dysfunction caused by T2DM, indicating that the inhibition of mitophagy may serve as the mechanism underlying T2DM-induced DCM.

It has been reported that ZIP7 mRNA expression was elevated by glucose in mouse pancreatic cells [31]. Similarly, ZIP7 activity was increased in cardiomyocytes isolated from T1DM rats and in H9c2 cells treated with high glucose [13]. Moreover, ZIP7 and ZnT7 play important roles in the progression of cardiac dysfunction in hyperglycemic cardiomyocytes [10]. These findings suggest that ZIP7 may play a role in the regulation of glucose homeostasis in the heart. In this study, ZIP7 was upregulated in cardiac cells exposed to high glucose or T2DM mouse hearts, and cKO of ZIP7 improved cardiac function, pointing to that upregulation of ZIP7 may contribute toT2DM-induced DCM. In our previous study we demonstrated that ZIP7 was upregulated in mouse hearts subjected to ischemia/reperfusion and the upregulation of ZIP7 contributes to the pathogenesis of myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting mitophagy [15]. In the present study, the inhibitory effect of T2DM on mitophagy was reversed by ZIP7 cKO, and ZIP7 cKO attenuated mitochondrial ROS generation as well as cardiac dysfunction in mouse hearts of T2DM. Since, as described above, mitophagy is protective against T2DM-induced DCM, it is tenable to propose that upregulation of ZIP7 contributes to pathogenesis of DCM induced by T2DM by inhibiting mitophagy. However, since mitochondrial ROS and MMP were reduced by cKO under physiological conditions, one may consider that ZIP7 may not completely account for the inhibitory action of T2DM on mitophagy. However, because the effects of T2DM on Mitosox Red (mitoROS), JC-1 (MMP), and mitophagy were almost completely blocked by ZIP7 cKO, it is tenable to propose that upregulation of ZIP7 plays a major role in T2DM-induced inhibition of mitophagy.

Several intracellular pathways including the PINKl/Parkin, FUNDC1, and BNIP3/NIX have been established to be responsible for initiation of mitophagy. Among them the PINK1/Parkin pathway is the best characterized pathway responsible for the induction of mitophagy. Under physiological conditions, PINK1 is degraded by peptidase and proteases after being imported into mitochondria. However, PINK1 is accumulated on the outer membrane of mitochondria when mitochondria are depolarized. Then PINK1 recruits and activates Parkin within mitochondria [32]. Activated Parkin induces mitochondrial protein ubiquitination, promoting the interaction of ubiquitinated proteins and mitophagy receptors [33]. In the study by Tong et al., deletion of Parkin inhibited mitophagy and exacerbated cardiac dysfunction during HFD consumption, indicating that Parkin-dependent mitophagy is essential for protecting the heart from development of DCM. In this study, we found that both PINK1 and Parkin expression within mitochondria was decreased by T2DM, which was prevented by ZIP7 cKO, suggesting that upregulation of ZIP7 leads to inhibition of mitophagy by inhibiting the PINK1/Parkin pathway in the setting of T2DM. In support, downregulation of PINK1 with its siRNA abolished the inhibitory effect of ZIP7 cKO on mitochondrial ROS generation.

PINK1 stabilization and accumulation in mitochondria is initiated by mitochondrial depolarization. ZIP7 is an important Zn2+ transporter and is responsible for promoting Zn2+ movement to the cytosol from intracellular organelles [34]. Our study found that T2DM increased ZIP7 expression in mitochondria, which may result in decrease of mitochondrial Zn2+ levels. Indeed, T2DM reduced mitochondrial Zn2+, an effect that was reversed by ZIP7 cKO. Since Zn2+ is a cation, a decrease of Zn2+ within mitochondria by T2DM will result in hyperpolarization of mitochondria, which may account for the inhibition of PINK1 accumulation in mitochondria. In our previous study, ZIP7 cKO increased mitochondria Zn2+ in the setting of cardiac ischemia/reperfusion leading to depolarization of mitochondria and promoted PINK1 accumulation in mitochondria [15]. Similarly, a recent study reported that knockdown of ZIP7 led to increased mitochondrial Zn2+ in nucleus pulposus cells [35].

In summary (Fig. 7), we have demonstrated that suppression of mitophagy due to ZIP7 upregulation underlies the mechanism by which T2DM induces DCM. Upregulation of mitochondrial ZIP7 blocks the PINK1/Parkin pathway by reducing mitochondrial Zn2+. Our findings suggest that ZIP7 plays a critical role in DCM and inhibition or inactivation of ZIP7 may serve as an effective therapeutic strategy for the treatment of patients with DCM caused by T2DM.

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram showing how ZIP7 upregulation leads to diabetic cardiomyopathy

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

NY, RZ, and HZ performed experiments and analyzed data. YY and ZX designed experiments and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grants 82270294 and 81970255) and Tianjin Municipal Education Commission (Grant 2022KJ195).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Ningzhi Yang, Rui Zhang, and Hualu Zhang have contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Yonghao Yu, Email: yyh@tmu.edu.cn.

Zhelong Xu, Email: zxu@tmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ritchie RH, Abel ED. Basic mechanisms of diabetic heart disease. Circ Res. 2020;126:1501–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jia G, Hill MA, Sowers JR. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: an update of mechanisms contributing to this clinical entity. Circ Res. 2018;122:624–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montaigne D, Marechal X, Coisne A, Debry N, Modine T, Fayad G, Potelle C, El Arid JM, Mouton S, Sebti Y, Duez H, Preau S, Remy-Jouet I, Zerimech F, Koussa M, Richard V, Neviere R, Edme JL, Lefebvre P, Staels B. Myocardial contractile dysfunction is associated with impaired mitochondrial function and dynamics in type 2 diabetic but not in obese patients. Circulation. 2014;130:554–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaludercic N, Di Lisa F. Mitochondrial ros formation in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Enriquez S, Kim I, Currin RT, Lemasters JJ. Tracker dyes to probe mitochondrial autophagy (mitophagy) in rat hepatocytes. Autophagy. 2006;2:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ketenci M, Zablocki D, Sadoshima J. Mitochondrial quality control mechanisms during diabetic cardiomyopathy. JMA J. 2022;5:407–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng H, Zhu H, Liu X, Huang X, Huang A, Huang Y. Mitophagy in diabetic cardiomyopathy: roles and mechanisms. Front cell Dev Biology. 2021;9:750382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tong M, Saito T, Zhai P, Oka SI, Mizushima W, Nakamura M, Ikeda S, Shirakabe A, Sadoshima J. Mitophagy is essential for maintaining cardiac function during high fat diet-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2019;124:1360–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adulcikas J, Sonda S, Norouzi S, Sohal SS, Myers S. Targeting the zinc transporter zip7 in the treatment of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nutrients. 2019;11:408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuncay E, Bitirim CV, Olgar Y, Durak A, Rutter GA, Turan B. Zn(2+)-transporters zip7 and znt7 play important role in progression of cardiac dysfunction via affecting sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum-mitochondria coupling in hyperglycemic cardiomyocytes. Mitochondrion. 2019;44:41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anzilotti C, Swan DJ, Boisson B. An essential role for the zn(2+) transporter zip7 in b cell development. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:350–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor KM, Vichova P, Jordan N, Hiscox S, Hendley R, Nicholson RI. Zip7-mediated intracellular zinc transport contributes to aberrant growth factor signaling in antihormone-resistant breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2008;149:4912–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuncay E, Bitirim VC, Durak A, Carrat GRJ, Taylor KM, Rutter GA, Turan B. Hyperglycemia-induced changes in zip7 and znt7 expression cause zn(2+) release from the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum and mediate er stress in the heart. Diabetes. 2017;66:1346–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Norouzi S, Adulcikas J, Henstridge DC. The zinc transporter zip7 is downregulated in skeletal muscle of insulin-resistant cells and in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cells. 2019;8:663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang H, Yang N, He H, Chai J, Cheng X, Zhao H, Zhou D, Teng T, Kong X, Yang Q, Xu Z. The zinc transporter zip7 (slc39a7) controls myocardial reperfusion injury by regulating mitophagy. Basic Res Cardiol. 2021;116:54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang N, Yu H, Liu T, Zhou Z, Feng B, Wang Y, Qian Z, Hou X, Zou J. Bmal1 downregulation leads to diabetic cardiomyopathy by promoting bcl2/ip3r-mediated mitochondrial ca(2+) overload. Redox Biol. 2023;64:102788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chouchani ET, Methner C, Nadtochiy SM, Logan A, Pell VR, Ding S, James AM, Cochemé HM, Reinhold J, Lilley KS, Partridge L, Fearnley IM, Robinson AJ, Hartley RC, Smith RA, Krieg T, Brookes PS, Murphy MP. Cardioprotection by s-nitrosation of a cysteine switch on mitochondrial complex i. Nat Med. 2013;19:753–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beer M, Seyfarth T, Sandstede J, Landschütz W, Lipke C, Köstler H, von Kienlin M, Harre K, Hahn D, Neubauer S. Absolute concentrations of high-energy phosphate metabolites in normal, hypertrophied, and failing human myocardium measured noninvasively with (31)p-sloop magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1267–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The framingham study. JAMA. 1979;241:2035–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Galloway CA, Yoon Y. Mitochondrial dynamics in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2015;22:1545–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boudina S, Sena S, O’Neill BT, Tathireddy P, Young ME, Abel ED. Reduced mitochondrial oxidative capacity and increased mitochondrial uncoupling impair myocardial energetics in obesity. Circulation. 2005;112:2686–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bugger H, Abel ED. Molecular mechanisms of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetologia. 2014;57:660–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volpe CMO, Villar-Delfino PH, Dos Anjos PMF, Nogueira-Machado JA. Cellular death, reactive oxygen species (ros) and diabetic complications. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He C, Zhu H, Li H, Zou MH, Xie Z. Dissociation of bcl-2-beclin1 complex by activated ampk enhances cardiac autophagy and protects against cardiomyocyte apoptosis in diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62:1270–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu W, Gao B, Li N, Wang J, Qiu C, Zhang G, Liu M, Zhang R, Li C, Ji G, Zhang Y. Sirt3 deficiency exacerbates diabetic cardiac dysfunction: role of foxo3a-parkin-mediated mitophagy. Biochim et Biophys Acta Mol Basis Disease. 2017;1863:1973–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang S, Zhao Z, Feng X, Cheng Z, Xiong Z, Wang T, Lin J, Zhang M, Hu J, Fan Y, Reiter RJ, Wang H, Sun D. Melatonin activates parkin translocation and rescues the impaired mitophagy activity of diabetic cardiomyopathy through mst1 inhibition. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:5132–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mu J, Zhang D, Tian Y, Xie Z, Zou MH. Brd4 inhibition by jq1 prevents high-fat diet-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy by activating pink1/parkin-mediated mitophagy in vivo. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2020;149:1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mellor KM, Bell JR, Young MJ, Ritchie RH, Delbridge LM. Myocardial autophagy activation and suppressed survival signaling is associated with insulin resistance in fructose-fed mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:1035–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tang Y, Liu J, Long J. Phosphatase and tensin homolog-induced putative kinase 1 and parkin in diabetic heart: role of mitophagy. J Diabetes Invest. 2015;6:250–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tong M, Saito T. Alternative mitophagy protects the heart against obesity-associated cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2021;129:1105–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellomo EA, Meur G, Rutter GA. Glucose regulates free cytosolic zn2+ concentration, slc39 (zip), and metallothionein gene expression in primary pancreatic islet β-cells. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:25778–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koyano F, Okatsu K, Kosako H, Tamura Y, Go E, Kimura M, Kimura Y, Tsuchiya H, Yoshihara H, Hirokawa T, Endo T, Fon EA, Trempe JF, Saeki Y, Tanaka K, Matsuda N. Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by pink1 to activate parkin. Nature. 2014;510:162–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lazarou M, Sliter DA, Kane LA, Sarraf SA, Wang C, Burman JL, Sideris DP, Fogel AI, Youle RJ. The ubiquitin kinase pink1 recruits autophagy receptors to induce mitophagy. Nature. 2015;524:309–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lichten LA, Cousins RJ. Mammalian zinc transporters: nutritional and physiologic regulation. Annu Rev Nutr. 2009;29:153–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song Y, Liang H, Li G, Ma L, Zhu D, Zhang W, Tong B, Li S, Gao Y, Wu X, Zhang Y, Feng X, Wang K, Yang C. The nlrx1-slc39a7 complex orchestrates mitochondrial dynamics and mitophagy to rejuvenate intervertebral disc by modulating mitochondrial Zn(2+) trafficking. Autophagy. 2024;20:809–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.