Abstract

Background

This research explores the relationships between the educational environment, student engagement, and academic achievement in Health Professions Education (HPE) , specifically examining the mediating role of engagement.

Methods

The study used cross-sectional design, and data were collected from 554 HPE students via self-report questionnaires. The Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) assessed the educational environment while the University Student Engagement Inventory measured learning engagement across the behavioral, emotional, and cognitive dimensions. Academic achievement was measured using cumulative GPA. Relationships between study variables were analyzed using path analysis.

Results

Path analysis demonstrated that four educational environment subscales directly affected emotional engagement (48% variance explained). Students’ perception of learning and academic self-perceptions influenced behavioral engagement (28% variance explained), while cognitive engagement was influenced by academic self-perceptions (39% variance explained). GPA was positively influenced by behavioral and cognitive engagement but negatively by emotional engagement. Cognitive and behavioral engagement mediated the relationship between students’ academic self-perceptions and academic achievement.

Conclusions

Students’ perceptions of the educational environment significantly influenced emotional engagement, followed by cognitive and behavioral engagement. Cognitive and behavioral engagement directly affected academic achievement and mediated the relationship between the educational environment and academic achievement.

Keywords: Student engagement, Sociocultural engagement, Validity

Introduction

The term “educational environment” encompasses the diverse range of social interactions, organizational cultures, and structures, along with the physical and virtual spaces that shape and influence learners’ experiences, perceptions, and learning [1]. The educational environment is measurable and can be modified to improve student learning outcomes. The assessment of students’ perceptions of the educational environment has been used as an important metric for enhancing the quality of education. The features of an educational environment could significantly affect the motivation of students, potentially enhancing or inhibiting their engagement in learning [2]. Therefore, student engagement in learning is a malleable construct which is shaped by the educational experiences of students [3]. The Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM) inventory was developed as a tool to evaluate student perceptions of the learning environments in medical schools and other health professions education institutions [4]. The DREEM was created three decades ago through a Delphi panel comprising faculty members from global medical schools and health professions. It was subsequently validated through testing with students across multiple countries [5, 6]. This inventory has received great attention as valuable instrument for measuring educational environment in undergraduate health professions education programs [7].

Student engagement is defined as the active investment of students in both academic and non-academic experiences, encompassing learning, teaching, research, governance, and community activities [8]. Within the learning domain, engagement of students refers to the psychological state of activity that enables students to feel energized, exert effort, and become deeply immersed in learning activities [9]. The most prevailing theoretical model of student engagement delineates engagement as a multidimensional construct comprising cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dimensions [10]. Cognitive engagement refers to the psychological investment in learning, where the students exceed mere fulfillment of requirements, prefers challenges, direct their efforts toward employing metacognitive and deep strategies to understand and master the content [10]. Behavioral engagement is evidenced by positive actions such as persistence, task completion, active participation, questioning, focused attention, and involvement in school-related activities. Emotional engagement refers to emotional reactions to classroom, school, or teachers including enjoyment, interest, and happiness [10].

The outcomes of student engagement in HPE suggest a range of academic and personal benefits. Student engagement is positively associated with academic performance, though often with a small effect size, and particularly with cognitive engagement [11–16]. However, student engagement does not consistently predict GPA or examination scores, indicating that its benefits may be more pronounced in non-quantitative aspects of student achievement [17–19]. In addition, student engagement significantly reduced burnout of HPE students [20, 21] especially the emotional and behavioral dimensions [22], improves student satisfaction with the learning experience [23], and enhances wellbeing of students [24]. Moreover, it is associated with favorable mental health outcomes, including diminished rates of depression [25], and elevated life satisfaction [26]. The significance of student engagement extends beyond its impact on individual students; it plays an important role in facilitating the teaching process by enhancing the intrinsic motivation of teachers [27]. Conversely, student disengagement significantly contributed to teacher burnout [28].

Studies have demonstrated that students’ engagement in the educational environment is an important contributor to their learning [4, 29, 30]. On the other hand, the educational environment is directly related to many learners factors such as self-regulated learning [30], approaches to learning [31], resilience and quality of life [32], attitudes towards specialties [33], psychological distress [34], mindfulness [35], and academic achievement [36]. The connection between the educational environment and student engagement can be traced back to Astin’s influential model, developed approximately three decades ago [37, 38]. According to Astin, students’ engagement in academic activities is significantly shaped by their interactions within the learning environment, which in turn affects their educational outcomes [38]. Building on Astin’s work, numerous other scholars have proposed models of student engagement that further emphasize the central role the educational environment plays in fostering student participation in learning [39, 40]. In line with this, we have recently developed a framework that positions the educational environment as a key factor influencing student engagement in HPE [8]. Despite these theoretical advancements, there remains a notable gap in empirical research investigating the specific relationship between the educational environment and student engagement in the HPE context. Therefore, the present study aims to evaluate the practical application of the student engagement framework, specifically examining how the educational environment predicts learning engagement among HPE students.

The findings from this project have the potential to contribute significantly to the HPE literature in this underexplored area, as well as provide valuable insights for evaluating and refining undergraduate programs. Therefore, as illustrated in Fig. 1, this study aims to examine the causal interactions between the educational environment in HPE and the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dimensions of student engagement. In the current study, we limit ourselves to the engagement of students in learning. In addition, we consider student engagement in learning as both an “outcome” of the educational environment and as a “mediator” between changes in the educational environment and academic achievement. Hence this study was designed to answer the following research questions: a) what are the influences of different aspects of the educational environment in HPE programs on student engagement in learning (cognitive, behavioral, and emotional)? b) what is the role of student engagement in HPE as a mediator between the changes in educational environment and academic achievement of students? Findings from this research might determine ways to best design and implement an educational environment which helps to improve student engagement in HPE institutions.

Fig. 1.

Study variables including antecedents (dimensions of the educational environment) using DREEM inventory, engagement dimensions (cognitive, behavioral, and emotional), and academic achievement

Methods

Research design and context

The study employed a quantitative cross-sectional design, utilizing self-reported surveys administered at a private University in UAE. The University encompasses six constituent colleges: Medicine, Dentistry, Pharmacy, Health Sciences, Nursing, and Healthcare Management and Economics. These colleges operate on a single campus with shared physical and human resources for academic activities. The university is characterized by a diverse student body, representing 77 nationalities and a range of cultural and social backgrounds.

Study instruments

The following instruments were used for data collection in this study:

Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM)

The DREEM inventory comprises 50 items categorized under five subscales: Students’ Perception of Teaching (12 items), Students’ Perception of Teachers (11 items), Students’ Academic Self-Perception (8 items), Students’ Perception of Atmosphere (12 items), and Students’ Social Self-Perception (7 items). Each subscale comprises a set of statements intended to evaluate various dimensions of the learning environment, and respondents are asked to rate their agreement using a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4 with 0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = uncertain, 3 = agree, and 4 = strongly agree. Items 4, 8, 9, 17, 25, 35, 39, 48, and 50 require reverse coding. Items with a mean score of 3.5 or more are real positive points, while items with a mean score of 2 or less indicate problematic areas which require attention. Items with a mean score of 2–3 are aspects of the climate that could be enhanced. The overall score of DREEM is 200 and interpreted as follows: 0 to 50 = very poor, 51 to 100 = plenty of problems, 101 to 150 = more positive than negative, and 151 to 200 = excellent. The overall reliability of the DREEM inventory demonstrated an excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.95. The reliability coefficients for the individual subscales were as follows: Students’ Perception of Learning (α = 0.84), Students’ Perception of Teachers (α = 0.79), Students’ Academic Self-Perception (α = 0.91), Students’ Perception of Atmosphere (α = 0.79), and Students’ Social Self-Perception (α = 0.68).

University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI)

The version of the USEI utilized in the present study comprises 15 items and has previously exhibited strong psychometric properties [41]. The questionnaire items are organized into a three-factor structure, addressing the dimensions of engagement: behavioral (5 items), emotional (5 items), and cognitive (5 items). Responses are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The questionnaire has demonstrated construct validity of the three-factor model across nine countries and four continents [42]. Furthermore, scores for emotional and behavioral engagement have shown a negative correlation with perceived burnout [21]. The USEI exhibited excellent internal consistency, with a reliability coefficient of α = 0.93. The reliability coefficients for its subscales were as follows: behavioral engagement (α = 0.82), emotional engagement (α = 0.91), and cognitive engagement (α = 0.88). The self-reported questionnaires were distributed to students through Google forms as an online survey during class time, ensuring anonymity and confidentiality to encourage honest responses. Google forms were distributed to the different HPE students after obtaining written informed consent.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were entered and analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 28.0. Analysis of Moment Structures (AMOS) program version 21 was used for studies involving structural equation modeling and path analysis. Independent Sample t-test was used to examine the gender differences in the study variables. One way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to examine the differences between the students in relation to their nationalities and type of program. Tukey’s HSD Test for multiple comparisons was used for post-hoc analysis of the differences between the categories of the study variables. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Internal consistency reliability of the study questionnaires was measured by using Cronbach’s alpha statistics.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) using path analysis was applied to test the links between educational environment dimensions with learning engagement dimensions and academic achievement. Various indices were employed to evaluate the model’s goodness-of-fit, as previously reported [43]. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) assesses model performance relative to a baseline, with a value of 0.90 or higher indicating a good fit. The Chi-Square (χ²) test compares implied and observed covariance matrices, where an insignificant χ² or a χ²/df ratio below 2 suggests a good fit. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) indicates the average discrepancy between observed and predicted covariance, with values at or below 0.08 considered acceptable. Additionally, the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) reflects the mean standardized difference between observed and model-implied correlation matrices, with values under 0.08 signifying a good fit. These indices collectively provide a comprehensive assessment of the model’s ability to represent the data [44, 45].

Validity of the USEI

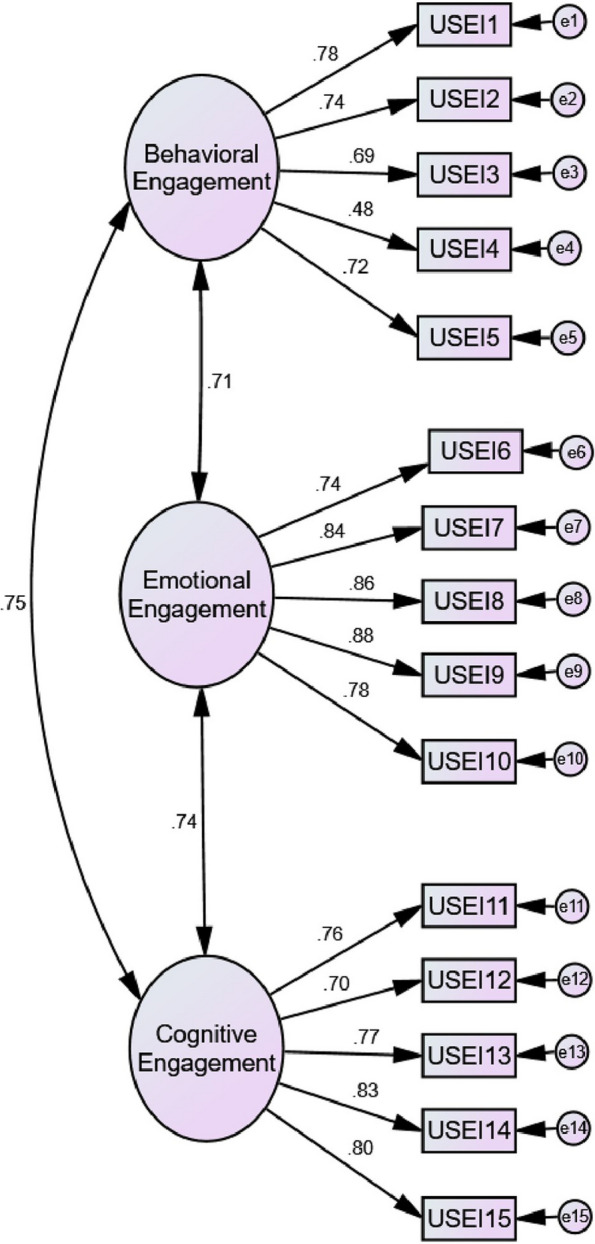

To assess the construct validity of the USEI, student responses were analyzed through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to evaluate the degree of fitness between the student scores and the three-factor model delineating the dimensions of student engagement. As shown in Fig. 2, applying the CFA using maximum likelihood estimation demonstrated acceptable fitness indices with the three-factor model (χ2 = 315.47, df = 84 (P = .000), χ2/df = 3.75, CFI = .96, TLI = 0.94, RMSEA = .07, SRMR = .05, and AIC = 270.00).

Fig. 2.

Confirmatory factor analysis illustrating the relationships between the constructs related to the University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI). Standard regression coefficients show that the students’ scores from the inventory items tap on three latent constructs (Behavioral engagement, Emotional engagement, and Cognitive engagement). Double-headed arrows illustrate the correlation coefficients between the constructs. The error terms (e1 to e15) inside the small circles reflect the unexplained variance and measurement errors

Results

Demographic variables

The target population of the study was 892 HPE students with an average response rate of 62.13% (n = 554). Table 1 illustrates the distribution of study participants by gender, with females comprising 74.5% and males 25.5% of the sample. Table 1 also shows the ethnic composition of students with nearly half of the students were Asian (46.3%), followed by Middle Eastern (31.6%), African (11.4%), European (2.2%), North American (7.9%), and Australian (.6%). Regarding academic programs, most participants were undergraduate medical students (61.6%), while the remainder were enrolled in dentistry (23.5%), nursing (10.3%), and health sciences (4.7%) programs.

Table 1.

Demographic variables in the study

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 141 | 25.5 |

| Male | 411 | 74.5 |

| Sum | 552 | |

| Geographic origin | ||

| Asia | 247 | 46.3 |

| Middle east | 169 | 31.6 |

| Africa | 61 | 11.4 |

| America | 42 | 7.9 |

| Europe | 12 | 2.2 |

| Australia | 3 | 0.6 |

| Sum | 534 | |

| Study program | ||

| Medicine | 341 | 61.5 |

| Dentistry | 130 | 23.5 |

| Nursing | 57 | 10.3 |

| Health Sciences | 26 | 4.7 |

| Sum | 554 | |

DREEM inventory findings

The average sum of DREEM score in the study sample was 134.74 ± 29.07 interpreted as “more positive than negative” with an average score of 2.69 ± .58. The sum scores of the DREEM subscales were as follows: Student’s Perception of Learning = 24.77 ± 5.71 (a more positive approach), Student’s Perception of Teachers = 30.01 ± 6.41 (moving in the right direction), Student’s Academic Self Perceptions = 23.22 ± 6.13 (feeling more on the positive side), Student’s Perception of Atmosphere = 31.03 ± 7.41 (a more positive atmosphere), and Student’s Social Self Perceptions = 18.10 ± 4.58 (not too bad).

Demographic differences in DREEM scores

No significant gender differences were observed in either the total DREEM scores or the subscales of the educational environment. A one-way ANOVA indicated that the total DREEM scores did not differ significantly across various university programs/colleges. However, significant differences in total DREEM scores were found among at least two nationalities (F (5, 528) = [5.89], p = [0.0001]). Tukey’s HSD Test for multiple comparisons revealed that the mean value of total DREEM score was significantly higher in Asian compared with Middle East students (p = 0.011, 95% C.I. = [1.39, 17.72]). Similarly, the total DREEM score was significantly higher in Asian compared with North American students (p = 0.005, 95% C.I. = [3.52, 30.83]).

Relationships between the study variables

The path model in Fig. 3 illustrates the relationships between the study variables. The model demonstrated acceptable fitness indices with the data (χ2 = 22.98, df = 9 (P = .006), χ2/df = 2.55, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .032, and AIC = 92.49).

Fig. 3.

Path analysis of the different scales of the DREEM inventory for measuring the educational environment, learning engagement (behavioral, emotional, and cognitive), and academic achievement of health professions education students (n = 554). Notes: Numbers on the arrows represent the estimates of standardized regression weights between the independent and dependent study variables. The error terms (e) inside the small circles reflect the unexplained variance and measurement errors. Interactions between variables were statistically significant at P < .05

Direct effects of the educational environment on student engagement

The results of the path model (Fig. 3) demonstrated significant positive direct effects of four subscales of the educational environment on emotional engagement of students with a total effect that explained 48% of the variance. These effects included Student’s Perceptions of Learning (β = .15, P = .001), Student’s Academic Self Perceptions (β = .20, P = .001), Student’s Perception of Atmosphere (β = .13, P = .001), and Student’s Social Self Perceptions (β = .27, P = .001). On the other hand, behavioral engagement was directly affected by Student’s Perception of Learning (β = .19, P = .001), and Student’s Academic Self Perceptions (β = .36, P = .001) with a total effect that explained 28% of the variance. However, cognitive engagement was strongly affected by Student’s Academic Self Perceptions (β = .63, P = .001) and explained 39% of the variance.

Direct effects on academic achievement of students

The student academic achievement (GPA) was positively affected by behavioral engagement (β = .15, P = .007) and cognitive engagement (β = .17, P = .004) of students but no significant effect on their emotional engagement (β =-0.08, P = .16). The overall effects on academic achievement of students explained only 6% of the variance.

Indirect effects

The study results demonstrated that both cognitive and behavioral engagement of students mediated the relationships between Student’s Academic Self Perceptions and academic achievement (β = .15, P = 0.001).

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the students’ perception of the educational environment is a significant predictor of their learning engagement. The strongest effect of the educational environment was on emotional engagement, followed by cognitive and behavioral engagement of students. Out of the five DREEM subscales, students’ academic self-perceptions emerged as the most robust predictor of student engagement in learning with direct effects on the three engagement dimensions. In addition, cognitive and behavioral engagement, but not emotional engagement, significantly predicted the overall academic achievement of students. Furthermore, both cognitive and behavioral engagement of students mediated the relationships between student’s academic self-perceptions and academic achievement.

Our study demonstrated that the overall score of the perceived quality of the educational environment in the University using the DREEM inventory is more positive than negative. The mean DREEM score of 135 exceeds those reported by medical schools in the region, including institutions in Bahrain and the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia [46], and is comparable to a previously conducted study at UAE in the same institution [47]. Similarly, students’ perceptions of the five subscales of the educational environment reflect a positive trend. The ethnic differences in students’ perceptions of the learning environment, as reflected in the DREEM scores, could be attributed to variations in cultural expectations, educational backgrounds, and adaptation to the institution’s pedagogical approach. Asian students, who scored significantly higher than their Middle Eastern and North American counterparts, may find the teaching methods, atmosphere, and institutional resources more aligned with their cultural norms and previous educational experiences, leading to a more favorable perception. In contrast, North American students may come from educational systems with different expectations or teaching styles, potentially leading to challenges in adapting to the current environment. These differences highlight the need for institutions to recognize and address diverse cultural backgrounds to create a more universally supportive educational environment.

We have demonstrated that student’s academic self-perception is the strongest predictor of cognitive and behavioral engagement of students. These findings could be explained by the self-determination theory where fulfillment of basic psychological needs of competence enhances the motivation and engagement of learners [48, 49]. Items in the academic self-perception scale of DREEM inventory address competence-related needs of the students, including the continuity of effective learning strategies, confidence in academic success, perceived adequacy of past coursework preparation, and perceptions of skill development. These findings align with a previous study on medical students, which showed that fostering student competence is the strongest predictor of their engagement in medical studies [50]. Therefore, learning environments should be designed to support the learner’s use of active learning strategies, problem solving skills, and the use of self-regulated learning [2]. Enhancing the motivation of students through the development of mastery goal orientation is a key for acquiring the self-regulated learning skills, which are essential for future clinical practice [2, 51]. Other studies in HPE have also demonstrated that student engagement is enhanced by applying active, student centered, and collaborative teaching methods such as problem-based learning [40, 52–54], team based learning [53, 55–57], flipped classroom [58, 59], and interprofessional education [60, 61]. Another study demonstrated strong relationships between teaching effectiveness and cognitive, behavioral, and emotional engagement in continuous medical education [62].

The application of self-determination theory could also explain the predictive power of students’ academic and social self-perceptions of the educational environment in enhancing their emotional engagement. The fulfillment of relatedness and interpersonal connection needs within the university context is evidenced by items of the social self-perceptions scale. These items include the availability of robust support systems for students experiencing stress, enjoyment and minimal boredom in course engagement, establishment of meaningful friendships within the academic community, satisfaction with social interactions, absence of loneliness, and favorable accommodation facilities. Establishing good relationships with peers and the feeling of support by the institutions strengthens the feeling of membership to the university community and the sense of belonging [63], which consequently enhances the student engagement in learning [64]. In addition, students interactions in classrooms, social interactions, and interactions with diversity enhanced the student engagement [29]. furthermore, participation of students in residential learning communities (RLCs) enhances the student engagement [65]. We have also recently demonstrated that that fostering a sense of relatedness by facilitators in small-group Problem-Based Learning (PBL) tutorials is a strong predictor of both cognitive and emotional engagement among medical students [66].

We demonstrated that a positive university atmosphere emerges as a significant determinant of student engagement. Within this dimension, student perceptions encompass aspects such as perceived relaxation during educational activities, the liberty to ask questions, the sense of social comfort within classroom settings, perception that the atmosphere fosters the cultivation of interpersonal competencies, and the overall enjoyment during educational activities, coupled with enhanced motivation for learning. In introductory STEM courses, students were engaged in learning when the teacher demonstrated an openness to student questions and acknowledged her/his role in fostering students success [67]. This feeling of “psychological safety” is an important drive for student engagement in the learning process [40]. The perceptions of a positive atmosphere could enhance the engagement of students through improving the sense of belonging [66]. This process evolves as students develop their identity and establish a sense of connection to the university community [63]. Student engagement is enhanced when teachers have good relationships with students such as being friendly and approachable and providing challenging learning tasks for students [68]. In addition, teachers who cultivate a relaxing atmosphere of learning by enhancing the psychological safety of students increases their level of engagement [66, 69]. Students demonstrating high levels of engagement reported feeling at ease with asking questions in class, seeking tutoring, attending supplemental instruction sessions, and collaborating with peers enrolled in the course [67]. Furthermore, providing constructive feedback to students can enhance the self-efficacy and psychological safety of students leading to increasing their engagement in learning [69].

The present study reveals that cognitive and behavioral engagement are significant determinants of academic achievement among HPE students. These findings indicate that high academic achievement of HPE students is predicted through significant psychological investment in learning by going beyond understanding the subject (cognitive engagement) as well as through behavioral engagement indicators such as paying attention in classes, and participation in class activities and group assignments. Other studies which used GPA for measuring academic performance reported inconsistent relationships between student engagement with no significant relationship with self-reported cumulative GPA [17, 18] or significant relationships with actual GPA [13, 70]. On the other hand, previous research has demonstrated a positive relationship between cognitive engagement and scores of students in knowledge-based assessments [14, 15, 71–73]. Similarly, behavioral engagement, as measured by participation in class activities, has been shown to correlate positively with academic performance [11, 74]. The differences between these study findings and ours could be related to the tool of measuring student engagement and the method of assessing academic achievement.

We have also demonstrated a full mediating role for cognitive and behavioral engagement between student’s academic self-perceptions and academic achievement. Other studies demonstrated a mediating role for cognitive engagement of medical students between using social media and academic achievement [72]. In addition, learning engagement mediated the relationships between student motivation and academic achievement [75].

Practical implications

The findings of this study have significant implications for enhancing student engagement and promoting academic success within health professions education. Firstly, given that cognitive and behavioral engagement are central predictors of academic achievement, educators should prioritize the development of a supportive learning environment that actively fosters these forms of engagement. Specifically, integrating curricula that enhance students’ academic self-perceptions, such as confidence in academic success and the application of active learning strategies, can strengthen both cognitive and behavioral engagement, which are essential for student success. Secondly, fostering a positive university atmosphere that promotes openness, psychological safety, and a sense of belonging is crucial for enhancing emotional engagement. Practical approaches to achieve this include creating robust social support networks, providing constructive feedback, and facilitating meaningful peer relationships. Lastly, the study indicates that cultural factors may significantly shape students’ perceptions of the educational environment and their engagement levels. Therefore, faculty and administrators should take these differences into account when designing educational interventions. Implementing culturally responsive teaching strategies that foster inclusivity can help meet the diverse needs of a varied student body, thereby enhancing engagement and overall academic success.

Limitations

While this study utilized a large sample and robust design, several limitations must be acknowledged. The study assumed that student engagement is a fixed construct across different timings of the program. However, many scholars view engagement as a dynamic state that fluctuates between different classroom settings. Consequently, a student may exhibit high engagement in one classroom and lower engagement in another. A limitation of this study is its focus on average engagement levels across courses without accounting for variations in engagement across different subjects, lessons, or instructors. Future research employing diverse methodologies is needed to explore how alterations in various dimensions of the learning environment impact student engagement. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of the study prevented the establishment of causal relationships, revealing only associations between independent and dependent variables, with student engagement serving as the dependent or mediating variable. Lastly, reliance solely on students’ self-reports may limit the comprehensiveness of the engagement measures.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the education environment is a significant predictor of HPE students’ engagement in learning. Emotional engagement appears to be the most influenced dimension by the educational environment with 48% of the variance explained, followed by cognitive engagement and then behavioral engagement. Student academic self-perception subscale of the DREEM is the strongest predictor with a significant effect on the three dimensions of student engagement. In addition, cognitive and behavioral engagement directly affected the student academic achievement, while emotional engagement does not significantly affect academic achievement.

Acknowledgements

None.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Glossary

- Learning engagement

the active investment of students in academic experiences at the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional dimensions.

Authors’ contributions

SEK initiated the idea of the research and developed the research protocols. RR was responsible for collecting and entering all study-related data. HH assisted in crafting the initial draft of the manuscript. DT provided valuable input for the manuscript development. All authors contributed to the revision, editing, and finalization of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) at Gulf Medical University (# IRB-COM-FAC-136-MAY-2024). Each student provided written informed consent and received a detailed information sheet outlining the research purpose, potential benefits, and affirming that participation was voluntary. The information sheet also emphasized the participants’ right to withdraw at any time, without providing a reason or facing any negative consequences. Confidentiality was maintained by ensuring the questionnaire was anonymous and by omitting any identifying information about the participants. Additionally, contact information for one of the authors was made available to address any questions or provide further clarification.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Gruppen LD, Irby DM, Durning SJ, Maggio LA. Conceptualizing learning environments in the Health professions. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):969–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross S, Pirraglia C, Aquilina AM, Zulla R. Effective competency-based medical education requires learning environments that promote a mastery goal orientation: a narrative review. Med Teach. 2022;44(5):527–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christenson SL, Reschly AL, Wylie C. Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. 1 ed. Springer Science + Business Media New York 2012. Boston, MA: Springer; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan CYW, Sum MY, Tan GMY, Tor PC, Sim K. Adoption and correlates of the Dundee Ready Educational Environment Measure (DREEM) in the evaluation of undergraduate learning environments - a systematic review. Med Teach. 2018;40(12):1240–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaughan B, Carter A, Macfarlane C, Morrison T. The DREEM, part 1: measurement of the educational environment in an osteopathy teaching program. BMC Med Educ 2014;14:99. 10.1186/1472-6920-14-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Roff S, McAleer S, Harden R, Al-Qahtani MA, Deza A, Groenen H. Development and validation of the Dundee Ready Education Environment Measure (DREEM). Med Teach. 1997;19(4):295–9. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soemantri D, Herrera C, Riquelme A. Measuring the educational environment in health professions studies: a systematic review. Med Teach. 2010;32(12):947–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kassab SE, Taylor D, Hamdy H. Student engagement in health professions education: AMEE Guide 152. Med Teach. 2023;45(9):949–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong ZY, Liem GAD. Student Engagement: Current State of the Construct, Conceptual Refinement, and Future Research Directions. Educational Psychol Rev. 2021.

- 10.Fredricks JA, Blumenfeld PC, Paris AH. School Engagement: potential of the Concept, State of the evidence. Rev Educ Res. 2004;74(1):59–109. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dewar A, Hope D, Jaap A, Cameron H. Predicting failure before it happens: a 5-year, 1042 participant prospective study. Med Teach. 2021;43(9):1039–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotgans JI, Schmidt HG. Cognitive engagement in the problem-based learning classroom. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2011;16(4):465–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Casuso-Holgado MJ, Cuesta-Vargas AIM-M. The association between academic engagement and achievement in health sciences students. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rotgans JI, Schmidt HG, Rajalingam P, Hao JWY, Canning CA, Ferenczi MA, et al. How cognitive engagement fluctuates during a team-based learning session and how it predicts academic achievement. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2018;23(2):339–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reinke NB. Promoting student engagement and academic achievement in first-year anatomy and physiology courses. Adv Physiol Educ. 2019;43(4):443–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Greene BA, Miller RB, Crowson HM, Duke BL, Akey KL. Predicting high school students’ cognitive engagement and achievement: contributions of classroom perceptions and motivation. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2004;29(4):462–82. [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Souza MS, Isac C, Venkatesaperumal R, Nairy KS, Amirtharaj A. Exploring nursing student engagement in the learning environment for improved learning outcomes. Clin Nurs Stud. 2013;2(1):1–16. 10.5430/cns.v2n1p1.

- 18.Abdul Sattar A, Kouar R, Amer Gillani S. Exploring nursing students Engagement in their learning Environment. Am J Nurs Res. 2018;6(1):18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kauffman CA, Derazin M, Asmar A, Kibble JD. Patterns of medical student engagement in a second-year pathophysiology course: relationship to USMLE Step 1 performance. Adv Physiol Educ. 2019;43(4):512–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Bu L, Li Y, Song J, Li N. The mediating effect of academic engagement between psychological capital and academic burnout among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;102:104938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abreu Alves S, Sinval J, Lucas Neto L, Maroco J, Goncalves Ferreira A, Oliveira P. Burnout and dropout intention in medical students: the protective role of academic engagement. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zucoloto ML, de Oliveira V, Maroco J, Bonini Campos JAD. School engagement and burnout in a sample of Brazilian students. Currents Pharm Teach Learn. 2016;8(5):659–66. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hensley A, Hampton D, Wilson JL, Culp-Roche A, Wiggins AT. A Multicenter Study of Student Engagement and satisfaction in Online Programs. J Nurs Educ. 2021;60(5):259–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruokamo A, Keskitalo ET. Engagement Enhances Well-Being in Simulation-Based Healthcare Education. In: Johnston JP, editor. EdMedia 2017: World Conference on Educational Media and Technology Washington. DC: Association for the advancement of computing in education; 2017. p. 138–47. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Lerner RM. Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence: implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance use. Dev Psychol. 2011;47(1):233–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis AD, Huebner ES, Malone PS, Valois RF. Life satisfaction and student engagement in adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2011;40(3):249–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Frenzel AC, Goetz T, Lüdtke O, Pekrun R, Sutton RE. Emotional transmission in the classroom: exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. J Educ Psychol. 2009;101(3):705–16. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chang M-L. An Appraisal Perspective of Teacher Burnout: examining the emotional work of teachers. Educational Psychol Rev. 2009;21(3):193–218. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trolian TL. Student Engagement in Higher Education: Conceptualizations, Measurement, and Research. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research. 2023. pp. 1–60.

- 30.van Schaik SM, Reeves SA, Headrick LA. Exemplary learning environments for the Health professions: a vision. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):975–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rochmawati E, Rahayu GR, Kumara A. Educational environment and approaches to learning of undergraduate nursing students in an Indonesian school of nursing. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(6):729–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tempski P, Santos IS, Mayer FB, Enns SC, Perotta B, Paro HB, et al. Relationship among Medical Student Resilience, Educational Environment and Quality of Life. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0131535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mahendran R, Lim HA, Verma S, Kua EH. The impact of the educational environment on career choice and attitudes toward psychiatry. Med Teach. 2015;37(5):494–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamada Y, Klugar M, Ivanova K, Oborna I. Psychological distress and academic self-perception among international medical students: the role of peer social support. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14(256):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu X, Wu D, Zhao X, Chen J, Xia J, Li M, et al. Relation of perceptions of educational environment with mindfulness among Chinese medical students: a longitudinal study. Med Educ Online. 2016;21:30664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayya S, Roff S. Students’ perceptions of educational environment: a comparison of academic achievers and under-achievers at Kasturba medical college, India. Educ Health (Abingdon). 2004;17(3):280–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Astin AW. Student involvement: a Developmental Theory for Higher Education. J Coll Student Personnel. 1984;25(4):297–308. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Astin AW. What matters in college? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1993. p. 482. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leach L, Zepke N. Engaging students in learning: a review of a conceptual organiser. High Educ Res Dev. 2011;30(2):193–204. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grijpma JW, Ramdas S, Broeksma L, Meeter M, Kusurkar RA, de la Croix A. Learning from the experts: stimulating Student Engagement in Small-group active learning. Perspect Med Educ. 2024;13(1):229–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Presoto CD, Wajngarten D, Dos Santos Domingos PA, Botta AC, Campos J, Pazos JM, et al. University engagement of dental students related to educational environment: a transnational study. PLoS One. 2021;16(11):e0259524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Assuncao H, Lin SW, Sit PS, Cheung KC, Harju-Luukkainen H, Smith T, et al. University Student Engagement Inventory (USEI): Transcultural Validity evidence across four continents. Front Psychol. 2019;10:2796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kassab SE, El-Baz A, Hassan N, Hamdy H, Mamede S, Schmidt HG. Construct validity of a questionnaire for measuring student engagement in problem-based learning tutorials. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lt H, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Modeling: Multidisciplinary J. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Young SL. Best practices for developing and Validating Scales for Health, Social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front Public Health. 2018;6:149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Al-Hazimi A, Al-Hyiani A, Roff S. Perceptions of the educational environment of the medical school in King Abdul Aziz University,Saudi Arabia. Med Teach. 2004;26(6):570–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shehnaz SI, Sreedharan J. Students’ perceptions of educational environment in a medical school experiencing curricular transition in United Arab Emirates. Med Teach. 2011;33(1):e37–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: classic definitions and new directions. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2000;25(1):54–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Connell JP, Wellborn JG. Competence, autonomy, and relatedness: a motivational analysis of self-system processes. In: Sroufe MRGLA, editor. Self processes and development. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 1991. pp. 43–77. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babenko O, Mosewich A, Abraham J, Lai H. Contributions of psychological needs, self-compassion, leisure-time exercise, and achievement goals to academic engagement and exhaustion in Canadian medical students. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2018;15:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pintrich PR. A conceptual Framework for assessing motivation and self-regulated learning in College Students. Educ Psych Rev. 2004;16(4):385–407. [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Malley KJ, Moran BJ, Haidet P, Seidel CL, Schneider V, Morgan RO, et al. Validation of an observation instrument for measuring student engagement in health professions settings. Eval Health Prof. 2003;26(1):86–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelly PA, Haidet P, Schneider V, Searle N, Seidel CL, Richards BF. A comparison of in-class learner engagement across lecture, problem-based learning, and team learning using the STROBE classroom observation tool. Teach Learn Med. 2005;17(2):112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alimoglu MK, Sarac DB, Alparslan D, Karakas AA, Altintas L. An observation tool for instructor and student behaviors to measure in-class learner engagement: a validation study. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:24037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alimoglu MK, Yardim S, Uysal H. The effectiveness of TBL with real patients in neurology education in terms of knowledge retention, in-class engagement, and learner reactions. Adv Physiol Educ. 2017;41(1):38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hopper MK, Kaiser AN. Engagement and higher order skill proficiency of students completing a medical physiology course in three diverse learning environments. Adv Physiol Educ. 2018;42(3):429–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ulfa Y, Igarashi Y, Takahata K, Shishido E, Horiuchi S. A comparison of team-based learning and lecture-based learning on clinical reasoning and classroom engagement: a cluster randomized controlled trial. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Riddle E, Gier E. Flipped Classroom improves Student Engagement, Student Performance, and sense of Community in a Nutritional sciences Course. Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(Suppl). 10.1093/cdn/nzz032.P07-007-19.

- 59.Burkhart SJ, Taylor JA, Kynn M, Craven DL, Swanepoel LC. Undergraduate students experience of Nutrition Education using the flipped Classroom Approach: a descriptive cohort study. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2020;52(4):394–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee S, Valtis YK, Jun T, Wang D, Zhang B, Chung EH, et al. Measuring and improving student engagement in clinical training. Educ Prim Care. 2018;29(1):22–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y, Ji Y. How do they learn: types and characteristics of medical and healthcare student engagement in a simulation-based learning environment. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stephenson CR, Bonnes SL, Sawatsky AP, Richards LW, Schleck CD, Mandrekar JN, et al. The relationship between learner engagement and teaching effectiveness: a novel assessment of student engagement in continuing medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Burkhardt MS, Gower S, Flavell H, Taplin J. Engagement and Creation of Professional Identity in undergraduate nursing students: a convention-style orientation event. J Nurs Educ. 2015;54(12):712–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gillen-O’Neel C. Sense of belonging and Student Engagement: a Daily Study of First- and Continuing-Generation College Students. Res High Educt. 2019;62(1):45–71. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hurtado SS, Gonyea RMG, Fosnacht PA. K. The Relationship between Residential Learning communities and Student Engagement. Learn Commun Res Pract. 2020;8(1):1–18.

- 66.Kassab SE, Hamdy H, Mamede S, Schmidt H. Influence of tutor interventions and group process on medical students’ engagement in problem-based learning. Med Educ. 2024 (11):1315–23. 10.1111/medu. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Gasiewski JA, Eagan MK, Garcia GA, Hurtado S, Chang MJ. From gatekeeping to Engagement: a multicontextual, mixed Method Study of Student Academic Engagement in Introductory STEM courses. Res High Educ. 2012;53(2):229–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bryson C, Hand L. The role of engagement in inspiring teaching and learning. Innovations Educ Teach Int. 2007;44(4):349–62. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tsuei SH, Lee D, Ho C, Regehr G, Nimmon L. Exploring the Construct of Psychological Safety in Medical Education. Acad Med. 2019;94(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S28-S35. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Bayoumy HM, Alsayed S. Investigating relationship of Perceived Learning Engagement, Motivation, and academic performance among nursing students: a Multisite Study. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;12:351–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wong V, Smith AJ, Hawkins NJ, Kumar RK, Young N, Kyaw M, et al. Adaptive tutorials Versus web-based resources in Radiology: a mixed methods comparison of Efficacy and Student Engagement. Acad Radiol. 2015;22(10):1299–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bhat IH, Gupta S. Mediating effect of student engagement on social network sites and academic performance of medical students. Int J Sociol Social Policy. 2019;39(9/10):899–910. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hadie SNH, Tan VPS, Omar N, Nik Mohd Alwi NA, Lim HL, Ku Marsilla KI. COVID-19 disruptions in Health Professional Education: use of cognitive load theory on students’ comprehension, cognitive load, Engagement, and motivation. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:739238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Grant LL, Opperman MJ, Schiller B, Chastain J, Richardson JD, Eckel C et al. Medical Student Engagement in a virtual learning Environment positively correlates with course performance and satisfaction in Psychiatry. Med Sci Educ. 2021:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Wu H, Li S, Zheng J, Guo J. Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med Educ Online. 2020;25(1):1742964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.