Abstract

Introduction:

Epithelioid hemangiomas (EHs) are rare vascular lesions which generally affect the skin and subcutaneous tissue but rarely seen in bones. It is a benign entity but intermediate grade, i.e., locally aggressive in nature. It has very confusing clinicoradiological and histopathological features which make diagnosis difficult and help us to avoid inappropriate treatment.

Case Report:

We present with a 32-year-old male with multifocal EH involving the distal radius, a few carpal bones (trapezium, trapezoid, and capitate), and the base of 2nd and 3rd metacarpals with extensive surrounding soft-tissue involvement. He was managed with intralesional extended curettage + bone grafting and is disease free till follow-up.

Conclusion:

As EH is a rare entity, this comes as a differential diagnostic in locally aggressive-looking lytic lesions in the bone which helps the treating orthopedic surgeons or orthopedic oncosurgeons to have this differential in their mind for a better diagnosis and further management.

Keywords: Epithelioid hemangioma, vascular tumors, locally aggressive

Learning Point of the Article:

Diagnosis and Management of Epithelioid Hemangioma.

Introduction

Epithelioid hemangioma (EH) of bone is a rare locally aggressive benign entity. It has discrete clinical and radiological features that confuse us toward the malignant origin. Although hemangiomas are the most common intraosseous vascular tumors, EH of bone is a rare and discrete entity. Bone epithelioid vascular tumors have been classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) into two distinct entities based on malignancy level: Benign Epithelioid hemangioma (EH) EH and other malignant categories including epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EHE) and epithelioid angiosarcoma (EAS). We report a case of EH of bone involving the distal radius, carpal, and metacarpal bones, which was a diagnostic challenge with discrete clinicoradiological and histopathological features.

Case Report

A 36-year-old male presented with pain and swelling over the right wrist extending toward the dorsal aspect of the hand associated with difficulty in wrist range of movements, for the past 3 months. There are no history of trauma or any twisting injury and no history of any fever. The swelling did not respond to any analgesics. Moreover, the swelling was increasing day by day, but there were no erythematous changes over the skin. Upon examination, there was tenderness over the wrist joint and carpometacarpal joints with a restricted range of movements of the wrist and multiple lobulated swelling felt over the dorsal aspect of the wrist.

After initial examination, the patient reported with X-ray and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A plain X-ray (Fig. 1) of the wrist showed a destructive lytic lesion over the distal radius which had ill-defined margins, lytic lesions also seen in the base of the 2nd and 3rd metacarpal base. MRI report (Figs. 2 and 3) showed an osteolytic lesion measuring 2.5 × 2.4 cm distal end of radius extending to a subarticular location with extraosseous soft-tissue component breaching the volar surface of distal radius. Multiple lytic lesions involving the trapezium, trapezoid bone, and capitate bones with associated marrow edema lytic lesions are also seen in the base of 2nd and 3rd metacarpals with enhancing soft tissue lesion measuring 2.9 × 2.1 cm abutting the carpal bones also seen. This was followed by whole-body positron emission tomography-computed tomography (CT) scan (Fig. 4) which revealed increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake of standardized uptake value Max-5 in the distal radius with soft-tissue component and involvement of multiple carpal bones as described in MRI reports.

Figure 1.

Plain wrist anteroposterior radiograph showing lytic lesion of the distal radius with thinning of cortex.

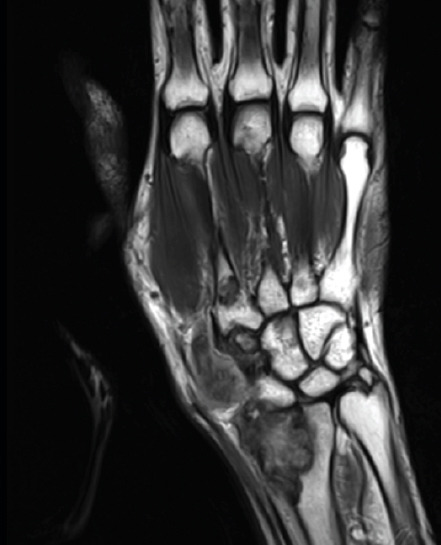

Figure 2.

Coronal T1-weighted magnetic resonance image showing lesion involving distal radius, scaphoid bone, and base of 2nd metacarpal bone.

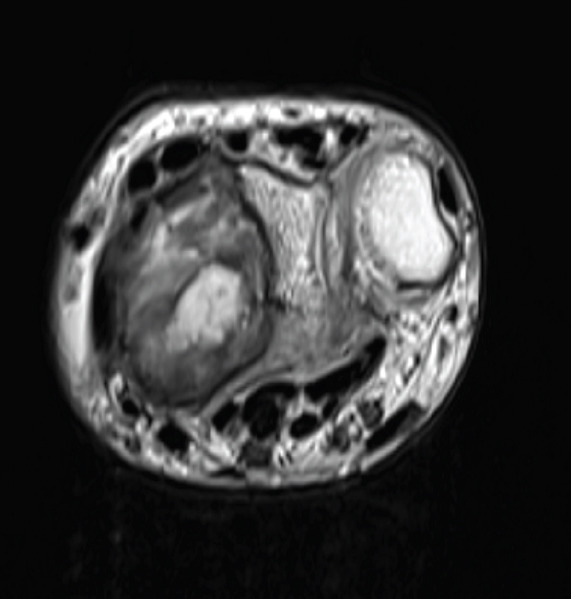

Figure 3.

Axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging showing lesion involving distal radius with lateral soft-tissue component and cortical breach.

Figure 4.

Positron emission tomography - computed tomography image showing the coronal image of distal radius showing increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake.

Then we performed a closed Jamshedji needle biopsy which was reported as EH. Then, he was managed with extended curettage + bone grafting + bone cementing and plating.

The patient was kept in close follow-up and there was no recurrence till 1-year post-operative period.

Histopathology

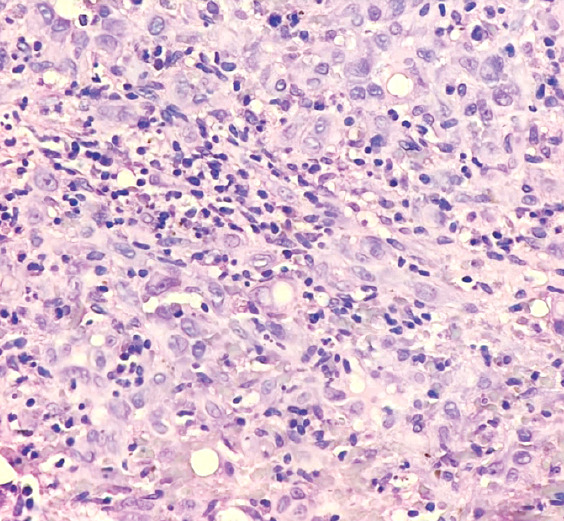

Biopsy-microscopy (Fig. 5) the lesion composed of a proliferation of small, capillary-sized vessels is lined by plump epithelioid endothelial cells arranged in a solid pattern. These cells are round vesicular nuclei with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with no evidence of atypia, necrosis, and nuclear pleomorphism.

Figure 5.

Lesion composed of solid nests of epithelioid endothelial cells (H and E ×400).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)-CD31-positive, CD34-positive, ERG nuclear-positive, S100-positive, pan cytokeratins (CK)-negative, and CD68-negative.

IHC with CD 31, CD 34 and ERG were positive in the epithelioid endothelial cells. S-100 was positive in few cells. PanCK and CD 68 was negative.Final histopathological report post-surgery - microscopy- tissue composed of tumor sheets of singly placed neoplastic cells with oval-to-spindled vesicular nuclei. Some of the cells exhibit nuclear grooves. Numerous intervening eosinophils and lymphocytes are present. Vascularity is prominent with increased numbers of vascular spaces showing plump endothelial cells. Mitotic activity or necrosis is not seen.

IHC-CD31 and CD34 show positivity, patchy positivity for CD68 and S100, and C1a- negative.

Discussion

EH tumorigenesis has been evolved as a distinct pathological entity since its discovery in the 1960s. Hartmann and Stewart at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Centre provided the first detailed descriptions of bone hemangioendothelioma from a case series and explained its unfavorable clinical course for malignant vascular tumors [1]. Rosai et al. suggested a unifying disease model encompassing diseases of the skin, soft tissue, large vessels, bone, and heart which was previously described [2]. The microscopic similarity of lower-grade hemangioendothelioma of bone cases to angio-lymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia (AHLE) suggests that both are characteristic of a single neoplastic but benign entity subsequently named “histiocytoid hemangioma.” Weiss and Enzinger introduced the term soft-tissue EHE to describe borderline to low-grade biologically malignant tumor that was histologically similar to EAS but less aggressive than the latter one [3]. Then, they concluded that AHLE was neoplastic and suggested the term “EH” which was widely accepted thereafter. In the latest WHO classification 2020, EH is classified as intermediate grade and EHE and EAS as malignant [4]. Hence, it is very important to distinguish EH from EHE and EAS owing to critical differences in clinical behavior and prognosis [5].

EH in bones is mostly found in metaphysis and diaphysis of long tubular bones of extremities, then in short tubular bones of distal lower extremities and flat bones. Nielsen et al. described the largest series of 50 cases of EH [6]. The mean age was 35 years (age range = 10–75 years). Males are slightly more affected than that of females. Clinical features are slow-growing soft and bony swellings with joint stiffness of the affected limb. It can also present as a pathological fracture occasionally that can occur secondary to osteolysis in the lesions. The distribution of soft-tissue EHs is broad but multifocality is seen in 18% of cases and the most commonly affected sites are the head, forehead, periauricular area, and scalp and in temporal artery distribution. Tumors have also been documented in extremities and less frequently in the trunk. Rarely, there are patients who have manifested with involvement of lymph nodes, soft tissues, skin, and parenchymal organs, such as lungs, heart, breast, spleen, and testis [7].

In conventional X-ray, lesions are osteolytic, septated, or expansile and generally well-defined. Aggressive features, such as mixed lytic and sclerotic appearance, cortical destruction, periosteal reaction, and soft tissue expansion can also be seen. Differential diagnosis based on a conventional radiograph can include giant cell tumor, aneurysmal bone cyst, browns tumor, infection or tuberculosis, Olliers disease, Maffuci syndrome, and metastatic deposits [8]. CT scans of bones EH show well-defined, septate, expansile, lytic lesions with cortical destructions and bony expansion. MRI is the investigation of choice for EH because it depicts soft-tissue extension of the lesion properly. In MRI, EH looks well defined but with soft-tissue involvement which can be misinterpreted as aggressive or malignant neoplasm. Hence, differential diagnosis according to MRI can be expanded into osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, or locally aggressive giant cell tumor due to multifocal cortical erosions and enhanced soft tissue components. EH looks hypointense or isointense relative to muscles in T1-weighted images and hyperintense in T2-weighted images, and lesions are markedly enhanced by Gadolinium contrast. Low-signal foci were seen on T2-weighted sequences that could represent small vascular flow voids in the setting of vascular malformations which expanded the differential to include tumors of vascular origins, i.e., hemangioma, soft tissue venous malformations, and multifocal EH or EHE. Cortical disruption, periosteal elevation, variable surrounding edema, and enhancement can be seen. These overlapping findings with other vascular tumors especially EHE and can be difficult to distinguish without histologic correlation [9, 10]. These overlapping radiological findings can be seen in other vascular tumours ; especially in EHE, so histological co-relation is a must to distinguish

Pathological features of epitheloid hemangioma are discrete which makes diagnosis difficult. Morphologically, EH has multinodular or lobulated with borders pushing into the medullar cavity sometimes breaching the bony cortex or adjacent soft tissues. They also show variable vaso-informative properties and form mature vessels with open lumens containing erythrocytes [9]. Microscopically, EH has lobules that commonly show a hypocellular periphery and gradually transition to hypercellular containing well-formed compact vessels lined with plump epithelioid endothelial cells that can protrude into the lumen creating a “tombstone-like” appearance [11]. These epithelioid endothelial cells contain variable nuclei (round - oval to cleaved) with evenly dispersed chromatin and have abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. The miotic activity is usually low supporting its benign nature [11]. A loose connective tissue stroma with inflammatory infiltrates, such as eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells is usually present. EH can be easily mistaken for other vascular tumors, particularly when comparing it to EHE; however, there are distinct histological differences. EHE is composed of cords and strands with solid aggregates of cells with round, oval- and cuboidal-shaped epithelioid endothelial cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm embedded in abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm embedded in a myxo-hyaline stroma. EH does not show the extracellular hyalinized matrix typical of EHE. Furthermore, EHE has a more primitive corded arrangement compared to mature vessels of EH and lacks its typical inflammatory infiltrate. EHE has also been related to the t (1:3) (p36:q25) translocation gene with WWTRi-CAMTA-1 fusion gene that can be identified with FISH and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction [12]. EH can be distinguished from malignant lesions such as angiosarcoma and metastatic carcinoma by the absence of nuclear pleomorphism, anaplasia, and cytologic atypia [10].

Vascular IHC markers such as ERG1, CD31, and CD34 should be used to highlight the endothelial differentiation. However, they cannot be used to differentiate among EH, EHE, and AS; hence, diagnosis is mainly on clinicoradiological and histo-morphological findings [13]. Pathologists should be aware of expression CK in epithelioid vascular tumors, which can prompt an erroneous diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma. Thus, judicious use of vascular markers and organ-specific markers can help in settling the diagnosis.

The clinical behavior of EH has recently been understood. The incidence of recurrence reported is 8–10%. Nielsen et al., revealed in their series that four patients experienced recurrence whereas one had lymph node involvement. Management of EH of bone had remained contentious with most patients being treated with intralesional curettage or local resection and had excellent prognosis [6, 14]. Few cases received radiational therapy or chemotherapy in view of local aggressive or recurrence or multicentricity. However, studies could not establish a conclusive benefit [6, 9]. Our case was managed with intralesional curettage and did not have any recurrence or lymph node involvement on 1-year follow-up. Hence, indicates guidelines established for a limited surgical treatment approach. All published cases of EH regardless of site and distribution in the body had remained healthy without demonstrating aggressive or life-threatening features on long-term follow-up.

As explained in this case report, clinical examination with multimodality imaging and good histopathological studies is essential to get a correct diagnosis in a broad differential diagnosis from benign bone tumors to malignant vascular tumors, which thereby helps in proper treatment and improved prognosis.

Conclusion

EH of bone is a rare tumor and has a difficult diagnosis due to its aggressive clinicoradiological features. This case had aggressive radiological features, extensive soft tissue components, and multifocality which were looking like a malignant bone tumor with extensive soft-tissue involvement. Only after a closed J needle biopsy, expert histopathological study, and clinico-radiological correlation helped us to come to a confirmed diagnosis of EH. The case highlights clinical, radiological, and histopathological findings of EH of bone and also provides insights about the approach to these uncommon locally aggressive bone tumors. This case will help orthopedic surgeons and orthopedic onco-surgeons about the diagnostic approach and management of these rare bone tumors. An expert histopathological examination with the judicious help of an IHC panel is essential for a proper diagnosis which helps onco-pathologists and pathologists to understand the nature of the disease. Finally, coordination between orthopedic surgeons, radiologists, and pathologists (O.R.P) teams is a key for diagnosing rare bone tumors and its management.

Clinical Message.

EH is a vascular neoplasm that generally occurs in soft tissues. However, when it comes to bone, it is a rare entity. Patients with aggressive-looking lytic lesions in bone in radiology to histopathology report as benign EH is a challenge for the clinicians to understand the course of management. Proper imaging like MRI which shows its soft-tissue invasion in a specific vascular course can be an indication for the diagnosis. Further, histopathological examination and proper IHC testing will help in the exact diagnosis. The rarity of the disease and unusual clinicoradiological features with distinct pathological features make it a worthy case for publication. The case will help orthopedic surgeons, orthopedic oncologists, pathologists, and radiologists for diagnosing this rare entity in bone.

Biography

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Nil

Source of Support: Nil

Consent: The authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report

References

- 1.Hartmann WH, Stewart FW. Hemangioendothelioma of bone. Unusual tumor characterized by indolent course. Cancer. 1962;15:846–54. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(196207/08)15:4<846::aid-cncr2820150421>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosai J, Gold J, Landy R. The histiocytoid hemangiomas. A unifying concept embracing several previously described entities of skin, soft tissue, large vessels, bone, and heart. Hum Pathol. 1979;10:707–30. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(79)80114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss SW, Enzinger FM. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma:A vascular tumor often mistaken for a carcinoma. Cancer. 1982;50:970–98. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820901)50:5<970::aid-cncr2820500527>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone. 5th ed. Lyon (France): IARC Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Floris G, Deraedt K, Samson I, Brys P, Sciot R. Epithelioid hemangioma of bone:A potentially metastasizing tumor? Int J Surg Pathol. 2006;14:9–15. doi: 10.1177/106689690601400102. discussion 16-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nielsen GP, Srivastava A, Kattapuram S, Deshpande V, O'Connell JX, Mangham CD, et al. Epithelioid hemangioma of bone revisited:A study of 50 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:270–7. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31817f6d51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramkumar S. Epithelioid haemangioma of bone:A case series and comprehensive literature review reappraising the diagnostic classification of all epithelioid vascular neoplasms of bone. Cureus. 2021;13:e15371. doi: 10.7759/cureus.15371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairfax A, Dey CB, Shaves S. Multifocal epithelioid hemangioma of the metacarpal bones:A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2019;14:1467–72. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2019.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Errani C, Zhang L, Panicek DM, Healey JH, Antonescu CR. Epithelioid hemangioma of bone and soft tissue:A reappraisal of a controversial entity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:1498–506. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2070-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wenger DE, Wold LE. Benign vascular lesions of bone:Radiologic and pathologic features. Skeletal Radiol. 2000;29:63–74. doi: 10.1007/s002560050012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hart JL, Edgar MA, Gardner JM. Vascular tumors of bone. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2014;31:30–8. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flucke U, Vogels RJ, De Saint Aubain Somerhausen N, Creytens DH, Reidl RG, Van Gorp JM. Epithelioid hemangioendothelioma:Clinicopathologic, immunhistochemical, and molecular genetic analysis of 39 cases. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:131. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van IJzendoorn DG, Bovée JV. Vascular tumors of bone:The evolvement of a classification based on molecular developments. Surg Pathol Clin. 2017;10:621–35. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2017.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bansal D, Pasricha S, Sharma A, Pruthi M, Tiwari A, Gupta G. Epithelioid haemangioma of bone:A series of four cases with a revision of this contentious entity. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2022;65:401–5. doi: 10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_1170_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]