Abstract

Introduction:

Benign bone tumors like osteochondroma are common during skeletal maturity occurring usually at the ends of long bones, such as the distal femur, proximal humerus, and proximal tibia. The tumor can occur in sessile or pedunculated forms. Mass lesions occurring around the ankle can lead to chronic pain, pathological fractures, progressive erosion, and scalloping of adjacent bone. This report highlights a case of a progressively enlarging bony swelling around the distal tibia with uncommon radiological and histological presentation managed with en bloc excision.

Case Report:

A 30-year-old male with 3 years of progressive bony enlargement without any history of significant trauma presented to our tertiary care hospital. The radiological and histological investigations were performed and many varied differentials were proposed. The lesion was provisionally diagnosed to be a case of an uncommon form of osteochondroma and en bloc excision was done. The patient followed up for a period of 6 months and the patient had uneventful recovery with no recurrence.

Conclusion:

Osteochondromas in the distal tibia are infrequent occurrences among common skeletal tumors. Timely surgical intervention is recommended for symptomatic lesions or those causing compression or mass effects.

Keywords: Osteochondroma, distal tibia, benign, tumor, fibular deformation, bizarre parosteal osteochondramatous proliferation

Learning Point of the Article:

Identification of atypical tumour presentations is the key to avoid diagnostic pitfalls and establishing appropriate management.

Introduction

Benign bone tumors encompass a diverse range of neoplasms, exhibiting variations in incidence, clinical presentation, and necessitating a broad spectrum of therapeutic interventions [1]. Based on the type of cell they include, these tumors can be broadly classified as either bone-forming, cartilage-forming, connective tissue, or vascular [2]. Approximately 30% of benign bone tumors are osteochondromas [1]. Osteochondromas, also known as exostosis, comprises of a bony protrusion covered in a cartilage cap that typically develops in the metaphysis or the metadiaphysis of the pelvis, proximal tibia, proximal humerus, and distal femur [3]. Osteochondromas may be solitary (85%) or multiple (15%) presenting as hereditary multiple exostoses (HME). Although the lesion may increase during childhood, no osteochondroma forms or grows beyond puberty [4]. Typically detected within the initial four decades of life, approximately 75% of these lesions manifest before reaching the age of 20 years with a male predominance [5].

Since osteochondromas do not cause many symptoms, the majority of them are traditionally diagnosed incidentally [4, 6]. Continuity of the cortex and medulla of the tumor, along with the underlying bone encased by a cartilaginous cap, is a pathognomonic feature in establishing the diagnosis [7].

Osteochondromas arising from the distal tibia, particularly those leading to fibula deformity, are infrequent occurrences and are known to cause degenerative changes, mechanical restriction of motion, syndesmotic complications, and subsequent ankle deformities [6]. Less than 1% of cases have the potential to progress to malignant transformation into chondrosarcomas [8]. Although most osteochondromas are asymptomatic and require no intervention; En bloc excision is the method of treating this tumor in cases of pressure symptoms or cosmetic deformities [7].

In this report, we highlighted a case of 30-years-old male with swelling over the distal third of the leg with an unusual presentation of tibial osteochondroma causing fibular deformation resected through a dual approach.

Case Report

A 30-year-old male with a 3-year history of gradually progressive painless swelling of the anterolateral aspect right distal leg presented to the outpatient department of our center. The swelling had slow growth progression and the patient didn’t report any difficulty in bearing weight over his limb.

Initial examination revealed a dome-shaped swelling over the anterolateral aspect of right distal leg approximately (Fig. 1). The swelling was with distinct borders. There was full range of motion across the ankle joint with no associated neurovascular defects.

Figure 1.

Pre-operative clinical presentation of the patient showing a dome-shaped bony swelling encircling 1/3rd to 1/4th circumference of the right distal leg measuring 7×6×4 cm. The swelling was hard in consistency and adhered to the underlying bone, neither febrile nor tender. The skin over the swelling had no secondary changes.

A plain radiograph of right leg anteroposterior and lateral views (Fig. 2) showed an expansile lobulated sclerotic lesion with multiple small lytic areas within it having a narrow zone of transition noted in the metadiaphyseal region of distal tibia with the lesion bulging into the adjacent soft tissue.

Figure 2.

Pre-operative plain radiograph AP and Lateral view of the leg demonstrating an expansile, lobulated sclerotic lesion that bulges into the surrounding soft tissue with a large zone of transition in the metaphyseodiaphyseal region of the distal tibia.

The routine blood tests and biochemical tests were normal. A presumptive differential of benign slow-growing neoplasm was suspected.

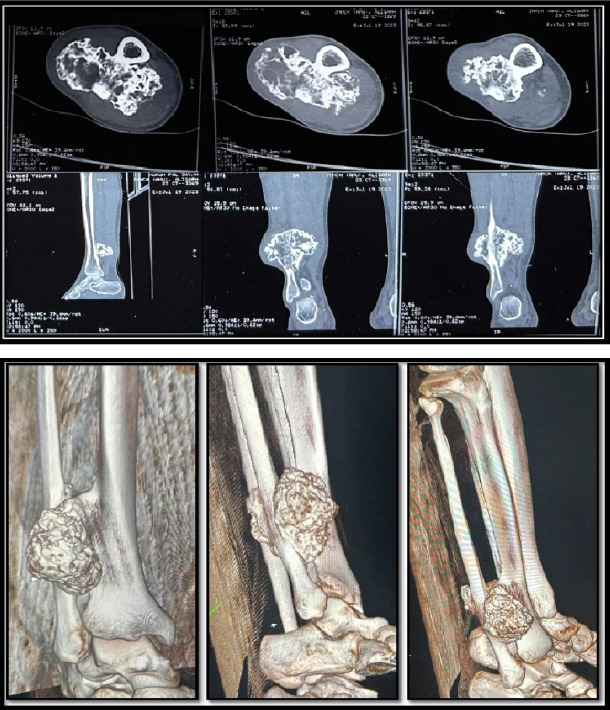

Non-contrast Computed tomography (Fig. 3a and b) of the patient was performed for detailed assessment of the lesion and preoperative planning which suggested “an aggressive bone lesion likely Parosteal osteosarcoma or a malignant osteochondroma.”

Figure 3.

(a) NCCT Right Leg with (b) Three-dimensional reconstruction showing a lobulated cauliflower like meta-diaphyseal predominantly sclerotic lesion with lytic areas and narrow zone of transition arising from the posterior cortex of the distal end of right tibia invading posteriorly into the cortex and possibly medullary cavity of right distal fibula.

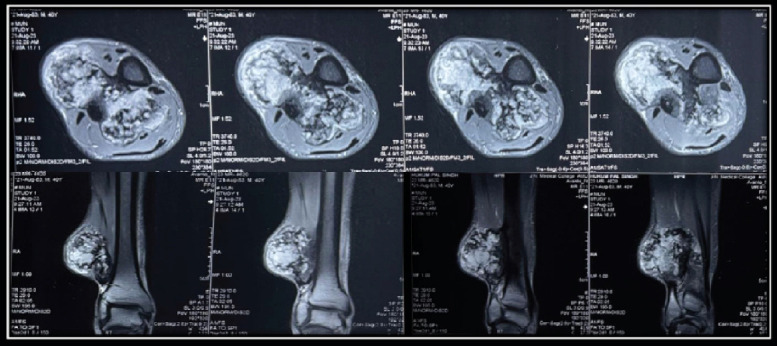

Magnetic resonance imaging of the lesion (Fig. 4) denoted a pedunculated, large, chondroid lesion arising from the lateral cortex of the distal tibia mixed with osseous and chondroid signals with chronic changes in the adjacent fibula the thickness of the cartilage component of the lesion was significant with mild diffusion restriction, suspicious for “malignant degeneration of the osteochondroma”.

Figure 4.

MRI Right leg denoting pedunculated, large, chondroid lesion arising from the lateral cortex of the distal tibia with adjacent cortical thickening giving rise to a large lobulated mass lesion mixed with osseous and chondroid signals (7.3 × 5.7 × 4.4 cm, AP × TR × CC). The lesion bulged in the anterior and posterior intermuscular plane of the leg causing significant compression and displacement of the extensor and flexor muscle compartments. Chronic pressure changes over the medial cortex of the distal fibula with mild pressure-related periostitis on the fibular cortex with no signs of invasion of the fibula.

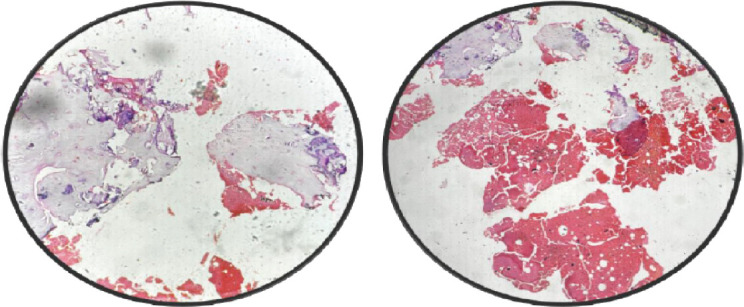

A tru-cut biopsy and fine needle aspiration cytology were performed subsequently. Histopathology report gave an impression of a benign cartilaginous lesion, possibly bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (BPOP lesion) (Fig. 5) and a differential of osteochondroma was suggested.

Figure 5.

Tru-cut biopsy of the lesion showing normocellularity with absence of atypia and focal areas of enchondral ossification admixed with fibrocollagenous tissue giving an impression of benign cartilaginous lesion possibly bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (BPOP lesion).

The pre-operative imaging and histopathological findings were all pointing toward an osteochondromatous lesion appearing in an unusual, rare form. Due to the locally aggressive nature as well as the possible mass effects of the condition, the patient was planned for en bloc excision. The surgical plane was exposed by using an anterolateral approach. The extent of the entire tumor could not be visualized and due to the inability to excise the complete mass, another posterolateral skin incision was made (Fig. 6), and the lesion and its whole fibrous cap were removed. The fibula was thinned out (Fig. 7) but was preserved during the resection and did not require supplementary fixation. The mass removed was sent for histopathological confirmation. The patient was stabilized on a below knee slab. The Histological examination of the excised sample showed mature hyaline cartilaginous cap with underlying woven bone and fibrocollagenous stroma confirming the diagnosis to be consistent with osteochondroma (Fig. 8).

Figure 6.

Intraoperative outlines of the lesion. The margins of the surface were identified and marked with a skin marker to delineate the extent of the incision. After appropriate dissection, the lesion was exposed and excised. The tumor was resected out from the tibial cortex and the normal cortical surface was visualized. The excised tumor mass was sent for histopathological diagnosis. The fibular surface was exposed and was evident for compression effects of the lesion showing periosteal irritation, though the bone was stable and required no fixation.

Figure 7.

Post-operative radiographic of the lesion showing thinning of the fibula due to mass effect. No syndesmotic instability was noted after tumor excision. A drain was put in situ to drain collections and the patient was stabilized on below knee slab for two weeks.

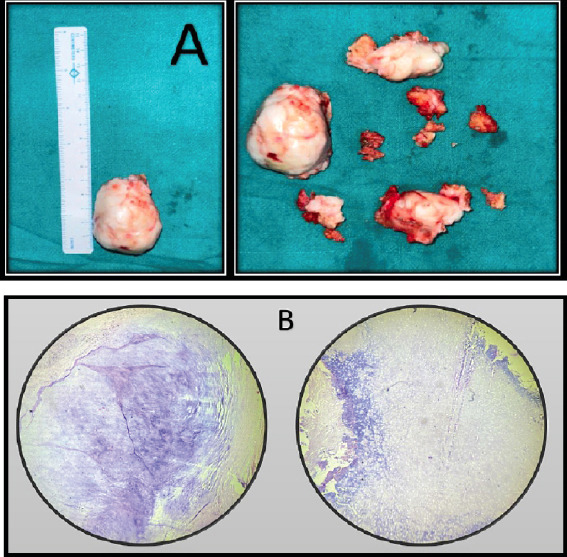

Figure 8.

A. Gross appearance of the excised sample. B. Histological examination of the excised tumor demonstrating mature hyaline cartilaginous cap with underlying woven bone and fibro-collagenous stroma confirming the diagnosis to be consistent with osteochondroma.

No neurovascular deficits were noted post-operatively. After two weeks, the slab was removed and partial weight bearing was allowed. The patient returned to his normal routine with full weight bearing at one month and had no functional limitations.

The patient was followed up for six months after surgery till date, and the patient is in good condition with no tumor recurrence or distant metastasis. The 6 months follow-up radiograph of the patient showed no tumor recurrence (Fig. 9). The post-operative scar was normal with no contracture or dehiscence and the patient had a good range of motion at the ankle with no difficulty in sitting cross-legged or squatting (Fig. 10).

Figure 9.

Radiograph at 6 months follow-up with no recurrence of tumor mass.

Figure 10.

Six months follow-up of the patient. Normal skin and surgical scar condition. Normal and comparable range of motion of the ankle. The patient is able to squat and sit cross-legged comfortably.

Review of Literature

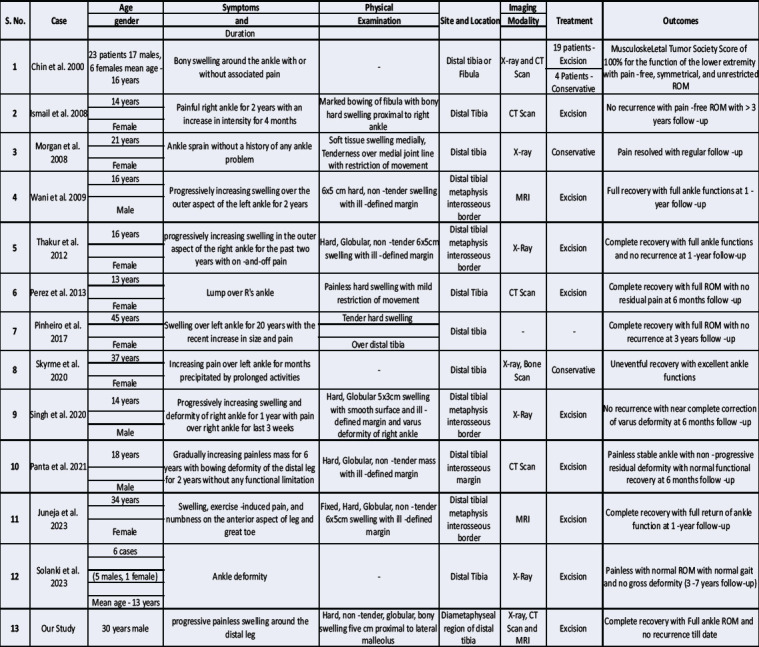

To the best of our knowledge, our study is one of the few that reviewed osteochondroma that arises around the distal tibia exclusively. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses criteria were followed during our literature search. We conducted the literature search through PubMed, EMBASE, and Scopus using the terms “osteochondroma,” “exostosis,” “distal leg,” “tibia,” and “fibula” with various spellings and Boolean logical operators. After reviewing and analyzing 41 abstracts, we included cases that gave a thorough account of the occurrence, symptoms, physical examination, radiologic features, treatment, and follow-up outcomes. Duplicate articles, articles written in languages other than English (in cases where the English translation is unavailable), cases of multiple exostosis, and cases of osteosarcoma were not included. Table 1 provides an overview of 13 studies, including our own.

Table 1.

Review of published literature of the Osteochondroma around the ankle and distal tibia.

Discussion

Osteochondroma, or osteocartilaginous exostosis, is a benign surface lesion of bone consisting of a bony outgrowth covered in a cartilaginous cap. According to some estimates, it is the most common benign skeletal tumor; however, because most are undetected and asymptomatic, the actual incidence is unknown [6]. These tumors typically appear in the second decade of life and are most frequently found in the metaphysis of tubular bones, including the proximal humerus, proximal tibia, distal femur, and distal fibula [6]. Its size and position determine the major symptoms, which include irritation of surrounding structures, bursitis from repeated rubbing, or stalk fracture from traumatisms [9]. After skeletal maturity, the tumor progression slows down and eventually stops in almost all cases. As a result, if at all possible, resection of an osteochondroma in a child should be delayed until skeletal maturity because the cartilaginous cap will be smaller and farther from the growth plate. Typically, the course is slow and predictable, with steady growth until physeal fusion [5].

In our case, the growth of the lesion began around the late twenties, much after the skeletal maturity which is unusual to the common scenario. Moreover, the size of the lesion expanded rapidly causing deformation and periostitis of the fibula and considerable compression of the soft tissues. However the patient didn’t complaint of any considerable pain or neurovascular deficit.

Aside from Multiple Hereditary Exostoses, osteochondromas involving the ankle are quite rare [10]. A few of the recorded sequelae in the neglected cases include plastic deformation of the tibia and fibula, mechanical obstruction of joint motion, syndesmotic issues (synostosis or diastasis), varus or valgus deformities of the ankle, and eventual degenerative alterations in the ankle joint [11]. Genc et al. [12] described a patient with a distal tibial osteochondroma resulting in a deep peroneal entrapment neuropathy that recovered completely after primary resection. Therefore, surgical resection of the exostosis becomes the mainstay in these cases. In our case, the lesion was located on the interosseus border of tibia around 3 cm above the syndesmosis and 5 cm from the lateral malleolus and no syndesmotic instability was encountered till time of presentation.

Osteochondromas have various histological differentials such as Turret Exostosis, Parosteal Osteosarcoma, Juxtacortical chondroma, Subperiosteal hematoma, benign parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (Nora lesion), etc. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation (BPOP) is a surface lesion most commonly involving the osseous structures of the hands and feet [13].

While grossly BPOP may also be mistaken for osteochondromas, there are some clear histological distinctions between the two conditions: in an osteochondroma, chondrocytes lack atypia and are frequently arranged in parallel lacunar spaces; in an osteochondroma, the trabecula of the bone is regularly arranged and oriented at ninety degrees to the cartilage cap [14]. In our case, tru-cut biopsy was reported to be in support of Nora lesion though a differential diagnosis of osteochondroma was proposed. In any case, surgical resection of the tumor was proposed. The final results of the excisional biopsy were confirmatory for osteochondroma.

Osteochondroma with continuous growth after skeletal maturity should raise the possibility of malignant transformation (around 1%) probably into chondrosarcoma [8]. Though luckily, in our case the malignant transformation hadn’t taken place yet.

Surgical treatment of distal tibial osteochondromas consists primarily of complete resection. Complete resection of the cartilaginous cap is important to prevent recurrence [6]. Anterior, posterior and trans-fibular approaches are known to be employed in tumor resections around ankle. Our patient was treated operatively because of progressive enlargement and cosmetic and mass effect. We determined that primary resection was required for this lesion, as images showed a large mass arising from the distal tibia, resulting in plastic deformation of the fibula and its impending fracture. A fibular osteotomy was not necessary because sufficient surgical exposure allowed for total excision.

Conclusion

Even though the majority of osteochondromas arise before skeletal maturity, case reports have shown that osteochondromas presenting in atypical locations and at unusual ages like late twenties do occur. Osteochondromas of the distal tibia are uncommon presentations of common skeletal tumors; the altered natural history and related complications are caused by the unique anatomy of this region. Early surgical intervention is advised in lesions exhibiting symptoms, or causing compression or mass effects, and complete excision is advised when feasible. It is important to emphasize the need for better identification and thorough assessment of these uncommon cases to prevent misinterpretation in clinical settings.

Clinical Message.

An extremely rare presentation of a common bone tumor, along with its diagnostic outline and treatment plan are summarized in this article. It is important to have prior knowledge, literature, and experience to manage such rare presentations appropriately, prevent complications, and enhance the quality of life.

Biography

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: Nil

Source of Support: Nil

Consent: The authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report

References

- 1.Hakim DN, Pelly T, Kulendran M, Caris JA. Benign tumours of the bone:A review. J Bone Oncol. 2015;4:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jbo.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woertler K. Benign bone tumors and tumor-like lesions:Value of cross-sectional imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:1820–35. doi: 10.1007/s00330-003-1902-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herrera-Perez M, De Mendoza MA, De Bergua-Domingo JM, Pais-Brito JL. Osteochondromas around the ankle:Report of a case and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:1025–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tepelenis K, Papathanakos G, Kitsouli A, Troupis T, Barbouti A, Vlachos K, et al. Osteochondromas:An updated review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, radiological features and treatment options. In Vivo. 2021;35:681–91. doi: 10.21873/invivo.12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ismail BE, Kissel CG, Husain ZS, Entwistle T. Osteochondroma of the distal tibia in an adolescent:A case report. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;47:554–8. doi: 10.1053/j.jfas.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tayara B, Uddin F, Al-Khateeb H. Distal tibial osteochondroma causing fibular deformation resected through a posterolateral approach:A case report and literature review. Curr Orthop Pract. 2016;27:E12–4. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain MJ, Kapadiya SS, Mutha YM, Mehta VJ, Shah KK, Agrawal AK. Unusually giant solitary osteochondroma of the ilium:A case report with review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep. 2023;13:42–8. doi: 10.13107/jocr.2023.v13.i11.4000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieg JC, Buckwalter JA, Peterson KK, El-Khoury GY, Robinson RA. Extensive growth of an osteochondroma in a skeletally mature patient. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:269–73. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199502000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davids JR, Glancy GL, Eilert RE. Fracture through the stalk of pedunculated osteochondromas. A report of three cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991;271:258–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takikawa K, Haga N, Tanaka H, Okada K. Characteristic factors of ankle valgus with multiple cartilaginous exostoses. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:761–5. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181847511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danielsson LG, Ei-Haddad I, Quadros O. Distal tibial osteochondroma deforming the fibula. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61:469–70. doi: 10.3109/17453679008993566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Genç B, Solak A, Kalaycıoğlu S, Şahin N. Distal tibial osteochondroma causing fibular deformity and deep peroneal nerve entrapment neuropathy:A case report. ACTA Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2014;48:463–6. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2014.2741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaabane S, Chelli Bouaziz M, Ben Ghars KH, Abid L, Jaafoura MH, Ladeb MF. Bizarre parosteal osteochondromatous proliferation:Nora's lesion. Iran J Radiol. 2011;8:119–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin KR, Kharrazi FD, Miller BS, Mankin HJ, Gebhardt MC. Osteochondromas of the distal aspect of the tibia or fibula. Natural history and treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1269–78. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200009000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan JL, Connolly C, Davies M. Osteochondroma of the Distal Fibula Causing Disruption of the Syndesmosis. Case no 6849. Austria: Eurorad; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wani IH, Sharma S, Malik FH, Singh M, Shiekh I, Salaria AQ. Distal tibial interosseous osteochondroma with impending fracture of fibula - A case report and review of literature. Cases J. 2009;2:115. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thakur GB, Jain M, Bihari AJ, Sriramka B. Transfibular excision of distal tibial interosseous osteochondroma with reconstruction of fibula using Sofield's technique - A case report. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2012;3:115–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jcot.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pinheiro AC, Pereira B, Melo J, Freitas D, Silva MV. Ankle osteochondroma:A case report. MOJ Orthop Rheumatol. 2017;9:00350. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skyrme AD, Chana R, Selmon GP, Butler-Manuel A. Osteochondroma of the distal tibia leading to deformity and stress fracture of the fibula. Foot Ankle Surg. 2003;9:129–30. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh CM, Magar MT, Sud AD. Osteochondroma of the distal tibia leading to deformity and stress fracture of the fibula - A case report. Med J Shree Birendra Hosp. 2021;20:173–6. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panta S, Thapa SK, Paudel KP. Distal tibia interosseous osteochondroma with fibula deformity. J Chitwan Med Coll. 2021;11:148–50. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juneja J, Garg G, Andrews N, Mehra AK, Sen R. Distal tibial interosseous osteochondroma with impending fracture of fibula, deformity and deep peroneal nerve entrapment neuropathy:A case report. J Bone Joint Dis. 2023;38:86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Solooki S, Yazdanpanah B, Akbarzadeh A. Management of distal tibial interosseous osteochondroma:A case series and review of literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2024;12:69–74. doi: 10.22038/ABJS.2023.73288.3395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]