Abstract

Background

Previous studies have been limited by their inability to differentiate between the effects of insulin sensitivity and β-cell function on the risk of kidney function decline, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and all-cause mortality. To address this knowledge gap, we aimed to investigate whether the physiological subtypes based on homeostasis model assessment-2 (HOMA2) indices of β-cell function (HOMA2-B) and insulin sensitivity (HOMA2-S) could be used to identify individuals with subsequently high or low of clinical outcome risk.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included 7,317 participants with a follow-up of up to 5 years. Based on HOMA2 indices, participants were categorized into four physiologic subtypes: the normal phenotype (high insulin sensitivity and high β-cell function), the insulinopenic phenotype (high insulin sensitivity and low β-cell function), the hyperinsulinaemic phenotype (low insulin sensitivity and high β-cell function), and the classical phenotype (low insulin sensitivity and low β-cell function). The outcomes included kidney function decline, CVD events (fatal and nonfatal), and all-cause mortality. Cox regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) for outcomes, and spline models were used to examine the dose-dependent associations of HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S with outcomes.

Results

A total of 1,488 (20.3%) were classified as normal, 2,179 (29.8%) as insulinopenic, 2,173 (29.7%) as hyperinsulinemic, and 1,477 (20.2%) as classical subtypes. Compared with other physiological subtypes, the classical subtype presented the highest risk of kidney function decline (classical vs. normal HR 11.50, 95% CI 4.31–30.67). The hyperinsulinemic subtype had the highest risk of CVD and all-cause mortality (hyperinsulinemic vs. normal: fatal CVD, HR 6.56, 95% CI 3.09–13.92; all-cause mortality, HR 4.56, 95% CI 2.97–7.00). Spline analyses indicated the dose-dependent associations of HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S with outcomes.

Conclusions

The classical subtype had the strongest correlation with the risk of kidney function decline, and the hyperinsulinemic subtype had the highest risk of CVD and all-cause mortality, which should be considered for interventions with precision medicine.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12933-024-02496-5.

Keywords: HOMA2-B, HOMA2-S, Kidney function decline, CVD events, All-cause mortality

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) refers to the gradual and permanent decline in kidney function and is a significant and increasingly common health condition [1–4]. One in ten people in high- and middle-income nations suffer from CKD [1–4]. However, until CKD reaches an advanced stage, symptoms usually do not become apparent [1–4]. Health services for CKD are changing such that the early achievement of better patient outcomes takes precedence over care for advanced CKD [1–4]. In addition, cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide [5]. The worldwide burden of CVD continues to increase despite tremendous progress in our knowledge of the disease and its treatment [5]. Early detection of CVD is crucial for initiating treatment with medication and counseling [5].

β-cell function and insulin sensitivity have been reported to be related to kidney function decline, CVD, and all-cause mortality, however, prior studies have been constrained by the inability to simultaneously evaluate insulin sensitivity and β-cell function and failed to distinguish between the independent impacts of insulin sensitivity and β-cell function [6–13]. The classification of physiological subgroups according to homeostasis model assessment-2 (HOMA2) measures of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity can be used to effectively address these gaps in knowledge [14], which includes four physiologic subtypes: a normal phenotype (high insulin sensitivity and high beta-cell function), an insulinopenic phenotype (high insulin sensitivity and low beta-cell function), a hyperinsulinaemic phenotype (low insulin sensitivity and high beta-cell function), and a classical phenotype (low insulin sensitivity and low beta-cell function) [14–17]. Therefore, participants from the China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort (4C) study were analyzed endeavor to investigate whether the physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity could identify individuals with subsequently high or low risk of kidney function decline, CVD, and all-cause mortality. Furthermore, we extended the investigation to diverse glucose tolerance statuses including normal glucose tolerance (NGT) and prediabetes. Restricted cubic spline (RCS) analyses were also performed to explore the dose-dependent associations of HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S with outcomes.

Materials and methods

Ethics committee and informed consent statement

The Committee on Human Research at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine and Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology approved the study protocol (Numbers: 14/2004 and TJ-IRB20231125), and all participants provided written informed consent. This study was conducted in compliance with the guidelines for cohort studies established by the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Research in Epidemiology (STROBE) [18].

Study design and population

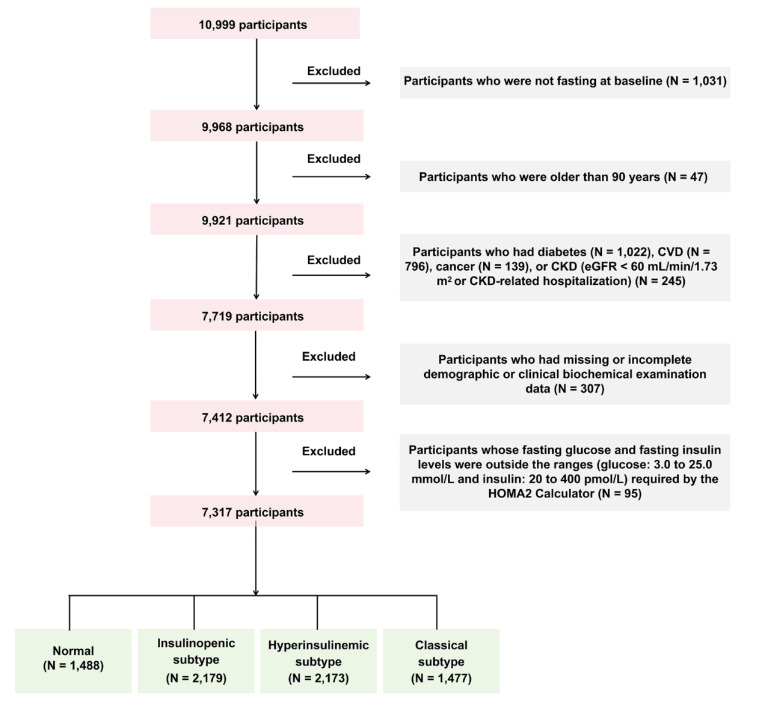

In this retrospective cohort study, at baseline, during 2011–2012, 10,999 participants were included from Hubei Province, as part of the 4C study [19–23]. Potential study participants were identified from the local residence registration records and were aged 40 years or older. Trained local community staff made door-to-door invitations to every eligible participant. Within a week of receiving the invitation, participants signed informed consent forms and were scheduled for a clinic visit and in-person interview [19–23]. The follow-up was conducted during 2014–2016 with a median follow-up duration of 3.8 years. During the follow-up, all participants were invited to attend an in-person follow-up visit. At baseline and follow-up visits, a comprehensive set of questionnaires, clinical measurements, oral glucose tolerance tests (OGTTs), and laboratory examinations were carried out following standardized protocols [19–23]. A total of 48 individuals were lost to follow-up. We excluded participants who were not fasting at baseline (N = 1,031); who were older than 90 years (N = 47); who had diabetes (N = 1,022), CVD (N = 796), cancer (N = 139), or CKD (estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR] < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or CKD-related hospitalization) (N = 245); who had missing or incomplete demographic or clinical biochemical examination data (N = 307); and whose fasting glucose and fasting insulin levels were outside the ranges (glucose: 3.0 to 25.0 mmol/L and insulin: 20 to 400 pmol/L) required by the HOMA2 Calculator (Version 2.2.3, Diabetes Trials Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, U.K., https://www.rdm.ox.ac.uk/about/our-clinical-facilities-and-units/DTU/software/homa) (N = 95) [14, 24], leaving 7,317 participants for analyses (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the cohort study CVD cardiovascular disease, CKD chronic kidney disease, HOMA2 homeostatic model assessment-2

Data collection

At baseline and follow-up visits, data from a comprehensive set of questionnaires, clinical measurements, OGTTs, and laboratory examinations were gathered from local community clinics [19, 25, 26]. Clinical staff members with training and certification from nearby community clinics conducted the standard questionnaire interviews and collected the anthropometrical measurement data. Standard questionnaires were administered to each participant to gather information on family history, lifestyle variables, illness history, medication history, and sociodemographic traits [19, 25, 26]. Definitions of glucose tolerance status, hypertension, and dislipidaemia are provided in the supplementary methods in Additional file 1. Smokers were defined as people who smoked at least once a week in the past 6 months. Alcohol drinkers were defined as people who drank alcohol at least once a week in the past 6 months. Anthropometric measurements including blood pressure (BP), heart rate, weight, height, waist circumference, and hip circumference, were conducted by clinical staff members in local community clinics who were trained and certified according to a standard protocol. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters [27]. The waist-hip ratio (WHR) was calculated by dividing the circumference of the waist by the circumference of the hips [28, 29]. Three consecutive BP measurements within a 5-minute interval were obtained from each participant using an automated electronic device (OMRON; Omron Company, China). The average of 3 measurements of systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were used for analysis.

Moreover, after the participants fasted for at least 10 h, the participants were asked to undergo the 75-g OGTT, and venous blood samples were collected at 0 and 2 h during the test. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), 2-h plasma glucose (PG2h), fasting insulin, creatinine, alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels were evaluated using the autoanalyzer (ARCHITECT ci16200, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL). Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) was evaluated by high performance liquid chromatography method (VARIANT II System; Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Calculation of indices of HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S and classification of participants into four pathophysiological subtypes based on HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S

HOMA2-S and β-cell function (HOMA2-B) were calculated from fasting glucose and insulin levels via the HOMA2 Calculator (version 2.2.3, Diabetes Trials Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, U.K., https://www.rdm.ox.ac.uk/about/our-clinical-facilities-and-units/DTU/software/homa) [14, 24]. Then participants were categorized into four pathophysiological subtypes including normal, insulinopenic, hyperinsulinemic, and classical subtypes based on HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S, as previously described [14, 17]. The normal subtype was defined as having high HOMA2-B and high HOMA2-S, the insulinopenic subtype was defined as having low HOMA2-B and high HOMA2-S, hyperinsulinemic subtype was defined as having high HOMA2-B and low HOMA2-S, and the classical subtype was defined as having low HOMA2-B and low HOMA2-S [14]. The categorization of low and high HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S was based on cutoffs of the median HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S values in the present cohort (HOMA2-B: 63.6% and HOMA2-S: 165.0%) [14, 17].

Outcome assessment

During the follow-up visit, study personnel documented kidney function decline, fatal CVD events, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality as the endpoints. All outcomes were verified via death certificates and hospital records. The investigators from the 4C study adjudication committee, consisting of internal medicine doctors, cardiologists, nephrologists, neurologists, and oncologists, made the adjudications for outcomes. Two committee members independently determined each outcome, and any disagreements were then addressed among the committee members for a final judgement. The adjudicators requested and assessed medical information, including pathology reports, throughout the adjudication process. The committee members were not informed of the baseline risk factors of research participants. Kidney function decline was defined as an eGFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2[30]. Two methods were used to calculate the eGFR: the Chinese Modified Simplified Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) [31, 32] and the CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) formula [31, 33]. The evaluations performed were as follows. 1. The Chinese Modified Simplified MDRD [31, 32]: 175 × [creatinine (mg/dL)] -1.234× age -0.179 [× 0.79 (if female)]. 2. The CKD-EPI formula [33]: 141 × min [creatinine (mg/dL)/κ, 1]α × max [creatinine (mg/dL)/κ, 1] −1.209 × 0.993age [× 1.018 (if female)], where κ is 0.7 for females and 0.9 for males and where α is − 0.329 for females and − 0.411 for males, respectively. “min” indicates the minimum of creatinine/κ or 1, and “max” indicates the maximum of creatinine/κ or 1 [33]. Nonfatal CVD events included myocardial infarction, heart failure, and stroke, and fatal CVD events included all deaths due to CVD [5]. All-cause death was defined as death from all causes [34, 35].

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analyses were conducted as follows. First, the subgroup analysis was performed with the stratification by sex (male/female), age (< 60/≥ 60 years old), and hypertension status (no/yes). Second, the analyses were also duplicated on the basis of cutoffs of the median HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S values (HOMA2-S: 63.5% and HOMA2-B: 115.3%) measured in a nondiabetic background cohort randomly sampled from all residents of the southern Denmark region (360,921 persons), as previously described [16].

Statistical analyses

The baseline characteristics of the participants were summarized as the means (standard deviations [SDs]) or medians (interquartile ratios [IQRs]) for continuous variables and numbers (proportions) for categorical variables. Baseline characteristics of participants between multiple groups were compared via analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables with a symmetric distribution, the Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables with a skewed distribution, and the Mantel-Haenszel chi-squared test for categorical variables to calculate the overall p-value (the overall p-value less than 0.05 means that at least one of the groups is different from the others) [36]. For pairwise comparisons, the Tukey method was used for normally distributed variables; otherwise, the Benjamini & Hochberg method was applied [37].

For the time-to-event analyses, person-time was calculated for each individual from the date of baseline to the date of the outcome occurred, or the end of follow-up, whichever came first. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The covariates in fully adjusted Cox regression models were generated according to previous publications and potential risk factors related to the development and progression of kidney function decline, CVD events, and all-cause mortality from clinical experience [3, 14, 15,38–41]. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. Model 3 was adjusted for all variables in Model 2 plus SBP, FPG, HbA1c, TC, LDL-C, TG, ALT, GGT, eGFR, smoking status, drinking status, hypotensive drug, and lipid-lowering drug at baseline. The associations of physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices with kidney function decline, CVD events, and all-cause mortality were investigated in all participants and those with NGT and prediabetes, respectively. Potential dose-dependent associations of HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S with outcomes were examined via RCSs. A 2-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. R version 4.4.1 (http://www.R-project.org, The R Foundation) was used for all analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics

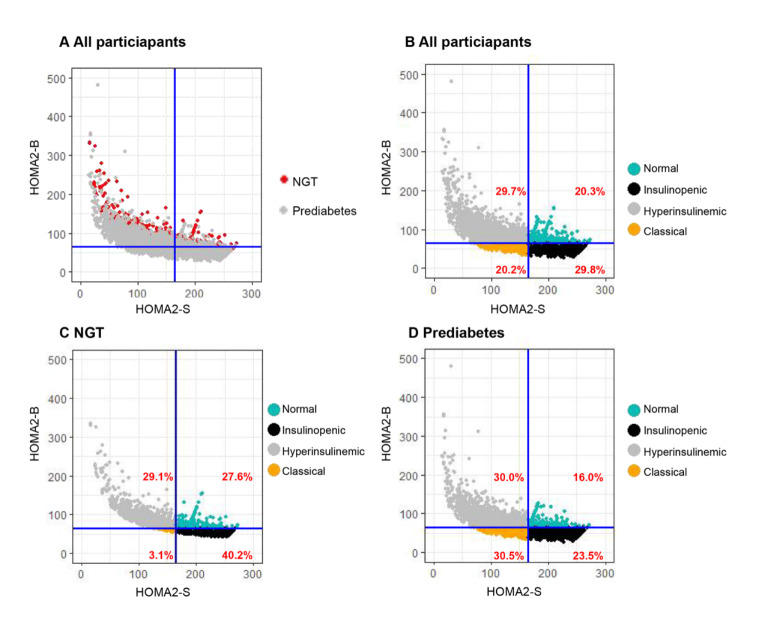

The baseline analysis included 7,317 participants (Table 1 and Fig. 1), with an average age of 60.02±10.64 years old, 34.7% of whom were male (Table 1). The participants were categorized into four physiological subtypes as follows: 1,488 (20.3%) were classified as normal, 2,179 (29.8%) as insulinopenic, 2,173 (29.7%) as hyperinsulinemic, and 1,477 (20.2%) as classical subtypes (Table 1). Moreover, participants with prediabetes had a greater prevalence of classical subtypes and a lower prevalence of normal subtypes compared with those with NGT (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics by their physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity in participants

| Characteristics | All | Normal | Insulinopenic subtype | Hyperinsulinemic subtype | Classical subtype | Overall p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | 7317 | 1488 (20.3) | 2179 (29.8) | 2173 (29.7) | 1477 (20.2) | |

| HOMA2-B (%) | 69.08 ± 26.40 | 73.00 ± 9.53 | 53.08 ± 7.32 * | 93.45 ± 34.13 *† | 52.87 ± 6.37 *§ | < 0.001 |

| HOMA2-S (%) | 159.03 ± 46.89 | 183.46 ± 17.41 | 200.80 ± 27.11 * | 105.56 ± 34.55 *† | 151.47 ± 17.58 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| Male (%) | 2542 (34.7) | 542 (36.4) | 901 (41.3) * | 489 (22.5) *† | 610 (41.3) *§ | < 0.001 |

| Age (y) | 60.02 ± 10.64 | 60.37 ± 11.36 | 60.86 ± 10.58 | 58.32 ± 9.95 *† | 60.95 ± 10.69§ | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.35 ± 3.39 | 22.42 ± 3.00 | 22.60 ± 3.12 * | 24.76 ± 3.37 *† | 23.34 ± 3.48 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| WHR | 0.86 ± 0.07 | 0.86 ± 0.08 | 0.85 ± 0.07 | 0.87 ± 0.07 *† | 0.86 ± 0.07 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 149.62 ± 23.79 | 146.56 ± 24.01 | 149.68 ± 23.83 * | 149.88 ± 23.64 * | 152.22 ± 23.39 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 81.26 ± 12.15 | 79.57 ± 12.26 | 80.54 ± 12.03 | 82.67 ± 12.05 *† | 81.97 ± 12.07 *† | < 0.001 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 79.74 ± 12.32 | 77.85 ± 11.50 | 78.82 ± 12.11 | 80.64 ± 11.87 *† | 81.66 ± 13.63 *† | < 0.001 |

| Fasting insulin (pmol/L) | 38.66 ± 24.42 | 29.66 ± 2.31 | 26.49 ± 3.30 * | 59.88 ± 36.20 *† | 34.44 ± 5.04 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| FPG (mmol/L) | 5.25 ± 0.52 | 4.71 ± 0.27 | 5.31 ± 0.35 * | 5.20 ± 0.49 *† | 5.80 ± 0.38 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| PG2h (mmol/L) | 6.25 ± 1.52 | 5.93 ± 1.43 | 6.17 ± 1.48 * | 6.21 ± 1.47 * | 6.74 ± 1.63 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| HbA1C (%) | 5.63 ± 0.38 | 5.57 ± 0.37 | 5.56 ± 0.38 | 5.66 ± 0.38 *† | 5.74 ± 0.38 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.46 ± 1.05 | 1.26 ± 0.83 | 1.31 ± 0.89 | 1.73 ± 1.23 *† | 1.47 ± 1.13 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 5.05 ± 0.93 | 4.93 ± 0.92 | 4.98 ± 0.88 | 5.14 ± 0.98 *† | 5.12 ± 0.94 *† | < 0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.52 ± 0.36 | 1.57 ± 0.36 | 1.57 ± 0.37 | 1.44 ± 0.31 *† | 1.54 ± 0.37 †§ | < 0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.85 ± 0.78 | 2.76 ± 0.76 | 2.78 ± 0.73 | 2.95 ± 0.81 *† | 2.90 ± 0.80 *† | < 0.001 |

| ALT (U/L) | 15.11 ± 12.41 | 13.83 ± 9.88 | 14.96 ± 12.58 * | 15.76 ± 12.03 * | 15.65 ± 14.69 * | < 0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 24.87 ± 14.03 | 25.57 ± 13.79 | 25.44 ± 13.67 | 23.29 ± 10.16 *† | 25.65 ± 18.75§ | < 0.001 |

| GGT (U/L) | 27.15 ± 37.66 | 24.82 ± 30.02 | 25.43 ± 32.20 | 27.93 ± 34.43 | 30.91 ± 53.14 *† | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine (umol/L) | 63.61 ± 13.99 | 62.37 ± 10.70 | 64.04 ± 14.33 * | 62.90 ± 12.45 † | 65.27 ± 17.86 *†§ | < 0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), MDRD method | 109.72 ± 25.22 | 111.97 ± 19.23 | 110.14 ± 18.87 | 108.63 ± 35.14 * | 108.46 ± 20.73 * | < 0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), CKD-EPI method | 95.17 ± 12.21 | 95.90 ± 11.71 | 95.07 ± 11.85 | 95.43 ± 12.41 | 94.18 ± 12.85 *§ | 0.001 |

| Smoking (%) | 1200 (16.4) | 264 (17.7) | 438 (20.1) | 214 (9.8) *† | 284 (19.2) § | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol (%) | 1565 (21.4) | 333 (22.4) | 556 (25.5) * | 307 (14.1) *† | 369 (25.0) § | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 1807 (24.7) | 268 (18.0) | 489 (22.4) * | 658 (30.3) *† | 392 (26.5) *†§ | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidaemia (%) | 42 (0.6) | 5 (0.3) | 5 (0.2) | 17 (0.8) | 15 (1.0) † | 0.005 |

| Hypotensive drug (%) | 931 (12.7) | 124 (8.3) | 233 (10.7) * | 367 (16.9) *† | 207 (14.0) *†§ | < 0.001 |

| Lipid-lowering drug (%) | 8 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 3 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 0.906 |

The data are presented as the mean ± SDs or numbers (%). The P-value for pairwise comparison: * indicates p < 0.05 compared with the group of normal; † indicates p < 0.05 compared with the group of insulinopenic subtype; § indicates p < 0.05 compared with the group of hyperinsulinemic subtype

SDs standard deviations, BMI body mass index, WHR waist-hip ratio, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, TC total cholesterol, HDL-C high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDL-C low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglycerides, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, FPG fasting plasma glucose, PG2h 2-h plasma glucose, ALT alanine transaminase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, GGT gamma-glutamyl transferase, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, MDRD Modification of Diet in Renal Disease, CKD-EPI the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

Fig. 2.

Distributions of HOMA2-B, HOMA2-S, and corresponding physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity. The HOMA2 computational model was used to calculate insulin sensitivity (HOMA2-S, %) and beta-cell function (HOMA2-B, %) based on fasting glucose and insulin values. Each dot represents a person. Participants were grouped into four subtypes including normal, insulinopenic, hyperinsulinemic, and classical subtypes. High and low HOMA2-S and HOMA2-B were defined as being above or below the median values (HOMA2-S: 165.0 and HOMA2-B: 63.6).A: Distribution of HOMA2-B, HOMA2-S, and corresponding physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity was presented in subgroups of different glucose statuses (A). B–D: Distributions of HOMA2-B, HOMA2-S, and corresponding physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity were presented in all participants (B), NGT (C), and prediabetes (D) respectively.HOMA2 homeostatic model assessment-2, NGT normal glucose status-2

The baseline characteristics of all participants by their physiological subtypes are shown in Table 1. Compared with those with other physiological subtypes, the hyperinsulinemic participants had the highest levels of BMI, WHR, fasting insulin, and TG, the lowest level of HDL-C, and the highest prevalence of hypertension (Table 1). In addition, compared with the other physiological subtypes, the classical participants presented the highest levels of SBP, FPG, PG2h, HbA1c, and creatinine (Table 1). Moreover, the baseline characteristics were compared by their physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity in participants with NGT (Table S1) and prediabetes (Table S2), respectively. First, in participants with NGT (Table S1), compared with those with other physiological subtypes, the hyperinsulinemic participants had the highest levels of BMI and fasting insulin. Compared with the other physiological subtypes, the classical participants presented the highest levels of SBP and FPG. Second, among the participants with prediabetes (Table S2), compared with those with other physiological subtypes, those with hyperinsulinemic presented the highest levels of BMI, WHR, fasting insulin, TG, TC, and LDL-C, the lowest level of HDL-C, and the highest prevalence of hypertension. Compared with those with other physiological subtypes, participants with the classical subtype had the highest levels of FPG.

Furthermore, the comparison of baseline characteristics across different glucose tolerance statuses is shown in Table S3. Across subgroups, as glucose metabolism status worsened, the levels of BMI, WHR, SBP, heart rate, fasting insulin, FPG, PG2h, HbA1c, TG, TC, LDL-C, GGT, and creatine, and the prevalence of hypertension increased (Table S3).

Associations of physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity with the risk of kidney function decline, CVD events, and all-cause mortality

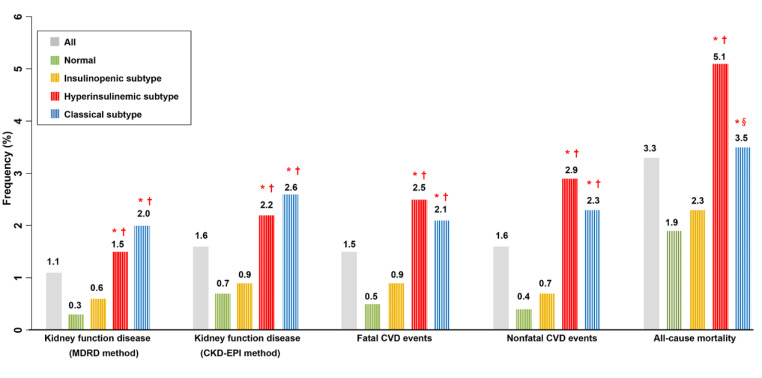

The incidence of kidney function decline was the greatest in the classical subtype, and the incidences of fatal CVD, nonfatal CVD, and all-cause mortality were the highest in the subtype of hyperinsulinemic than in the other physiological subtypes (Fig. 3). In addition, the incidences of outcomes were compared by their physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices in participants with NGT and prediabetes, respectively and the results were consistent (Table S4). The p-values were not less than 0.05 in some comparisons, which is probably due to the low number of outcomes with reduced statistical power. Furthermore, Kaplan–Meier curves demonstrated that the cumulative incidence of kidney function decline was the greatest in the classical subtype, and the cumulative incidences of CVD, and all-cause mortality were the highest in the subtype of hyperinsulinemic than in the other physiological subtypes (Fig. S1).

Fig. 3.

Frequency of outcomes according to physiologic subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity in all participants

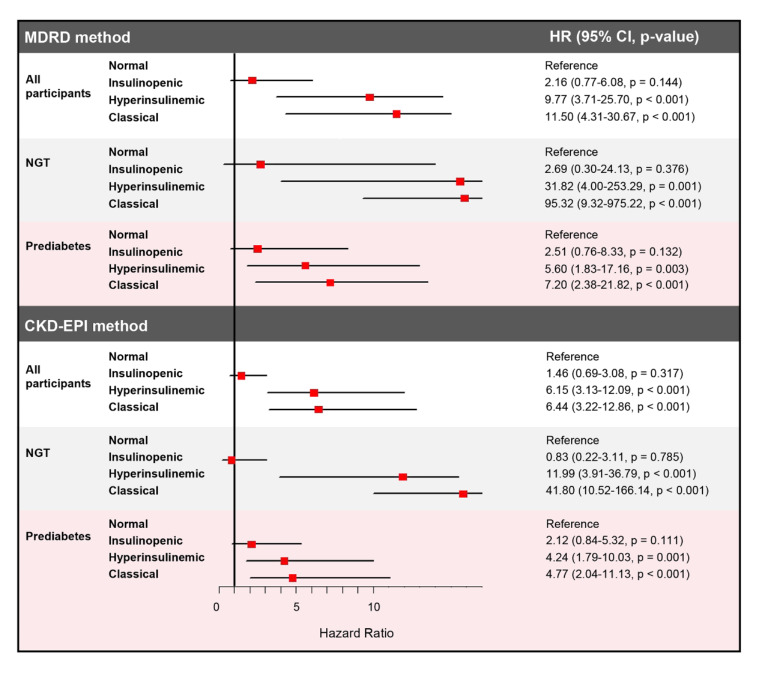

The incidence per 1000 person-years of kidney function decline (Table S5) was the greatest in the classical subtype, and the incidences per 1000 person-years of CVD (Table S6), and all-cause mortality (Table S7) were the highest in the subtype of hyperinsulinemic than in the other physiological subtypes. Cox regression revealed that in all participants, in the subtype of classical, the HRs for kidney function decline were greater after full adjustment compared with that in other physiological subtypes (MDRD method: classical vs. normal HR 11.50, 95% CI 4.31–30.67, p < 0.001; CKD-EPI method: classical vs. normal HR 6.44, 95% CI 3.22–12.86, p < 0.001) (Table S5 and Fig. 4). In the subtype of hyperinsulinemic, the HRs for kidney function decline were the second highest after full adjustment compared with that in other physiological subtypes (MDRD method: hyperinsulinemic vs. normal HR 9.77, 95% CI 3.71–25.70, p < 0.001; CKD-EPI method: hyperinsulinemic vs. normal HR 6.15, 95% CI 3.13–12.09, p < 0.001) (Table S5 and Fig. 4). In insulinopenic subtypes, the HRs for kidney function decline showed non-significant statistically (MDRD method: insulinopenic vs. normal HR 2.16, 95% CI 0.77–6.08, p = 0.144; CKD-EPI method: insulinopenic vs. normal HR 1.46, 95% CI 0.69–3.08, p = 0.317) (Table S5 and Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot showing the adjusted HRs of physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity for kidney function decline in all participants and participants with NGT and prediabetes

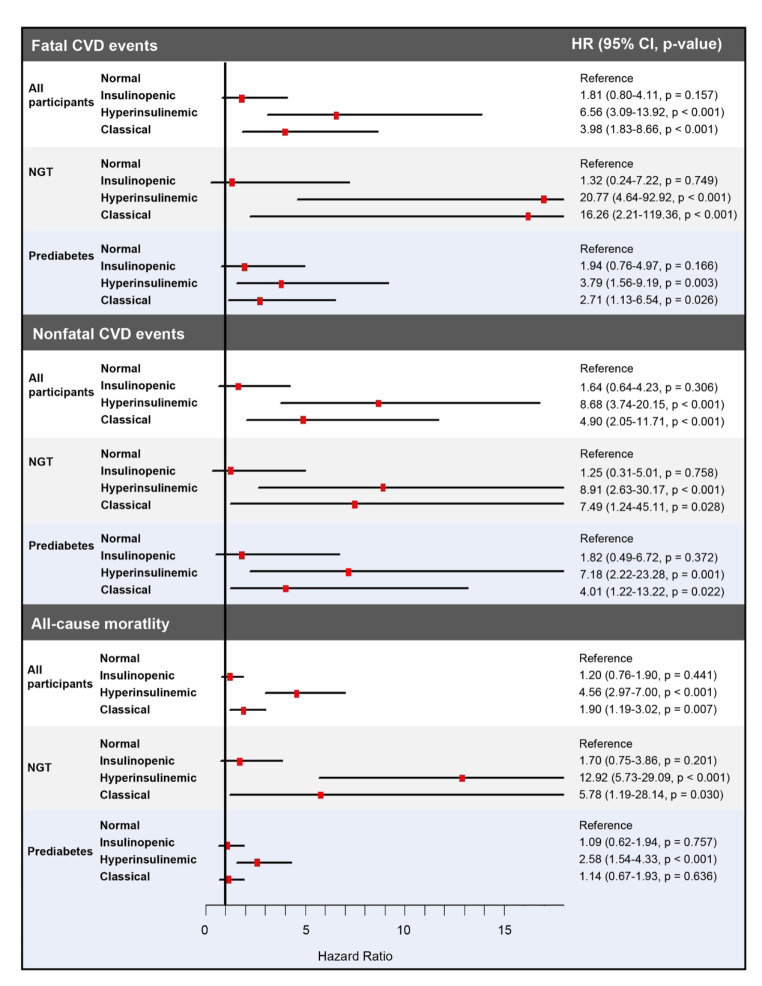

The HR for fatal CVD, in the subtype of hyperinsulinemic, was highest compared with that in other physiological subtypes after full adjustment (hyperinsulinemic vs. normal HR 6.56, 95% CI 3.09–13.92, p < 0.001) (Table S6 and Fig. 6). In the subtype of classical, the HR for fatal CVD was the second highest after full adjustment compared with that of other physiological subtypes (classical vs. normal HR 3.98, 95% CI 1.83–8.66, p < 0.001) (Table S6 and Fig. 5). In insulinopenic subtypes, the HR for fatal CVD showed non-significant statistically (insulinopenic vs. normal HR 1.81, 95% CI 0.80–4.11, p = 0.157) (Table S6 and Fig. 5).

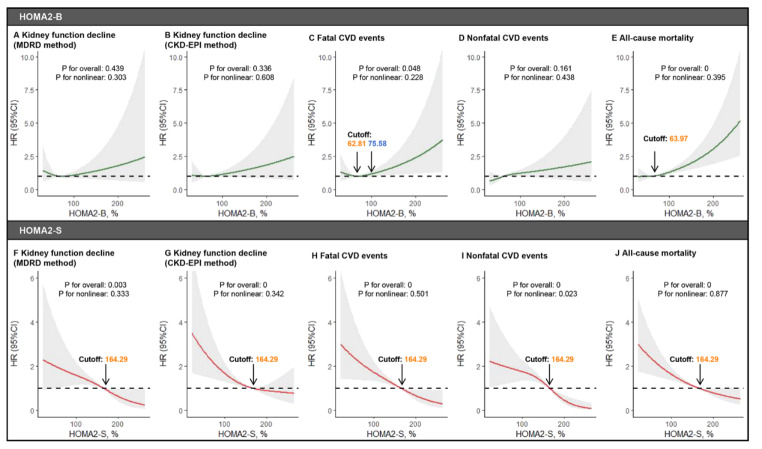

Fig. 6.

RCS showing the dose-response relationships of HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S with the risk of kidney function decline, fatal CVD events, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality The dose-response relationships of HOMA2-B with the risk of kidney function decline (A for the MDRD method,B for the CKD-EPI method), fatal CVD events (C), nonfatal CVD events (D), and all-cause mortality (E). The dose-response relationships of HOMA2-B with the risk of kidney function decline (F for the MDRD method,G for the CKD-EPI method), fatal CVD events (H), nonfatal CVD events (I), and all-cause mortality (J). RCS restricted cubic spline, HOMA2 homeostatic model assessment-2, MDRD Modification of Diet in Renal Disease, CKD-EPI the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration, CVD cardiovascular disease

Fig. 5.

Forest plot showing the adjusted HRs of physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity for CVD events and all-cause mortality in all participants and participants with NGT and prediabetes. The model was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, SBP, FPG, HbA1c, TC, LDL-C, TG, ALT, GGT, eGFR, smoking status, drinking status, hypotensive drug, and lipid-lowering drug. HOMA2 homeostatic model assessment-2, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, NGT normal glucose status, CVD cardiovascular disease

Similarly, the HR for nonfatal CVD, in the subtype of hyperinsulinemic, was highest compared with that in other physiological subtypes after full adjustment (hyperinsulinemic vs. normal HR 8.68, 95% CI 3.74–20.15, p < 0.001) (Table S6 and Fig. 5). In the subtype of classical, the HR for nonfatal CVD was the second highest after full adjustment compared with that of other physiological subtypes (classical vs. normal HR 4.90, 95% CI 2.05–11.71, p < 0.001) (Table S6 and Fig. 5). In insulinopenic subtypes, the HR for nonfatal CVD did not exhibit statistically significant differences (insulinopenic vs. normal HR 1.64, 95% CI 0.64–4.23, p = 0.306) (Table S6 and Fig. 5).

Consistently, the HR for all-cause mortality, in the subtype of hyperinsulinemic, was highest compared with that in other physiological subtypes after full adjustment (hyperinsulinemic vs. normal HR 4.56, 95% CI 2.97–7.00, p < 0.001) (Table S7 and Fig. 5). In the subtype of classical, the HR for all-cause mortality was the second highest after full adjustment compared with that in other physiological subtypes (classical vs. normal HR 1.90, 95% CI 1.19–3.02, p = 0.007) (Table S7 and Fig. 5). In insulinopenic subtypes, the HR for all-cause mortality showed non-significant statistically (insulinopenic vs. normal HR 1.20, 95% CI 0.76–1.90, p = 0.441) (Table S7 and Fig. 5).

Furthermore, Cox regression analyses were performed by their physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices in participants with NGT and prediabetes, respectively. Consistently, the classical subtype exhibited the highest HRs compared with other physiological subtypes for the risk of kidney function decline in participants with NGT and prediabetes, respectively and the classical subtype showed more prominent associations with risk of kidney function decline in NGT than in prediabetes (Table S5 and Fig. 4). Also, the hyperinsulinemic subtype displayed the highest HRs compared with other physiological subtypes for the risk of CVD and all-cause mortality in participants with NGT and prediabetes, respectively and the hyperinsulinemic subtype showed more prominent associations with risk of CVD and all-cause mortality in NGT than in prediabetes (Tables S6–S7 and Fig. 5).

RCS analysis indicated the dose-dependent associations of HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S with the risk of kidney function decline, CVD events, and all-cause mortality

RCS analyses (Fig. 6) suggested dose-dependent associations of HOMA2-B with the risk of fatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality and dose-dependent associations of HOMA2-S with the risk of kidney function decline, fatal CVD events, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality. The cutoffs for HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S were also identified (Fig. 6).

Sensitivity analyses

First, the subgroup analyses showed no significant interaction in any of the subgroups stratified by sex (male/female), age (<60/≥60 years old), or hypertension status (no/yes) for the risk of kidney function decline (Table S8), CVD events (Table S9), or all-cause mortality (Table S10) (p > 0.05), which further validated our results.

Second, the analyses were duplicated based on cutoffs of the median HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S values (HOMA2-S: 63.5% and HOMA2-B: 115.3%) measured in a non-diabetic background cohort randomly sampled from all residents of southern Denmark region (360,921 persons), as previously described [16]. Similarly, baseline characteristics revealed that, compared with other physiological subtypes, the hyperinsulinemic participants had the highest levels of BMI, WHR, and fasting insulin. Compared with other physiological subtypes, the classical participants presented the highest levels of FPG, PG2h, and HbA1c (Table S11). The Cox regression analyses (Table S12) showed that the classical subtype had the most robust correlation with kidney function decline and the hyperinsulinemic subtype showed the strongest association with fatal CVD, nonfatal CVD, and death from all causes.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study revealed that physiological subgroups based on HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S can identify people at high or low risk of kidney function decline, CVD, and all-cause mortality. The classical subtype had the strongest correlation with the risk of kidney function decline, and the hyperinsulinemic subtype had the second highest. The hyperinsulinemic subtype had the highest risk of CVD and all-cause mortality, and the classical subtype had the second-highest risk. The insulinopenic subtype was not significantly correlated with the risk of kidney function decline, CVD, and all-cause mortality. Furthermore, we extended the investigation to diverse glucose tolerance statuses and found similar results in those with NGT and prediabetes, respectively. The RCS analyses indicated dose-dependent associations of HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S with kidney function decline, CVD events, and all-cause mortality.

Before this study, no research had been conducted to examine the associations of physiological subtypes determined by both HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S with the risk of kidney function decline. On the one hand, regarding the association between insulin sensitivity and kidney function decline, previous publications reported that there is a correlation between higher insulin resistance (IR) and the risk of developing chronic renal disease [6, 42]. Our results further extended the findings of previous observational studies that have failed to separate the effects of beta-cell function and IR and revealed that lower insulin sensitivity was associated with a greater risk of kidney function decline. More importantly, this association was confirmed beyond β-cell function by the comparison of individuals with the classical subtype (low HOMA2-B and low HOMA2-S) with individuals with the insulinopenic subtype (low HOMA2-B and high HOMA2-S) and the comparison of individuals with the hyperinsulinemic subtype (high HOMA2-B and low HOMA2-S) with individuals with the normal subtype (high HOMA2-B and high HOMA2-S). Mechanically, by causing hypertriglyceridemia and worsening renal hemodynamics through mechanisms such as activation of the sympathetic nervous system, sodium retention, and decreased Na+, K+-ATPase activity, IR aggravates kidney disease [43]. On the other hand, with respect to the association between β-cell function and kidney function decline, Kim et al. reported that HOMA-B was greater in the CKD group than in the non-CKD group in a Korean cohort study of 5,188 adults aged 20 years or older [10]. Schroijen et al. found that HOMA-B was non-significantly associated with glomerular hyperfiltration (HR 1.00, 95% CI 0.99–1.00) and micro-albuminuria (HR 1.00, 95% CI 1.00–1.00) in a Netherlands cohort study of middle-aged 6,338 individuals [11]. The results of the studies of Kim [10] and Schroijen [11] at first glance, appear to be different from ours. We hypothesize that there is an intricate interaction effect when both phenotypes (insulin sensitivity and β-cell function) are considered simultaneously, rather than the simple existence of each phenotype independently, which is also an intriguing aspect of our research that indicates the necessity of this study. The present study revealed that when IR is present, insulin deficiency poses a more severe threat to kidney function decline compared to hyperinsulinemia by the comparison of individuals with the classical subtype (low HOMA2-B and low HOMA2-S) against individuals with the hyperinsulinemic subtype (high HOMA2-B and low HOMA2-S). The mechanism that insulin deficiency threatens kidney function decline is probably because insulin deficiency increases the expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 in renal mesangial cells, which contributes to the development of nephropathy [44].

The relationships between physiological subtypes based on HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S and CVD events, and all-cause mortality in the general population have not been investigated previously [7, 8, 12, 13], and the present study revealed that the hyperinsulinemic subtype with high HOMA2-B and low HOMA2-S was associated with the highest risk of fatal CVD, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality compared with other physiological subtypes. Prior researches were constrained by the absence of the ability to evaluate both insulin sensitivity and β-cell activity simultaneously. Ke [7] and Liu [8] et al. found significant associations between IR and elevated risk of CVD and all-cause death. The present study was consistent with these studies and provided a fresh perspective on the integration of insulin sensitivity and β-cell function. In the present study, by comparing individuals with the classical subtype to those with the insulinopenic subtype, and comparing individuals with the hyperinsulinemic subtype to those with the normal subtype, we discovered that IR was linked to increased risk of CVD and all-cause mortality, regardless of β-cell function. Mechanically, IR leads to disrupted calcium regulation and dysfunction of mitochondria, which cause impaired diastolic dysfunction, myocardial cell death, and fibrosis [45]. In addition, Wang [12] and Garcífound et al. [13] discovered that hyperinsulinemia is a predictor of CVD and all-cause death. In the present study, by comparing individuals with the hyperinsulinemic subtype to those with the classical subtype, and comparing individuals with the normal subtype to those with the insulinopenic subtype, we discovered that hyperinsulinemic was linked to increased risk of CVD and all-cause mortality, only in the presence of IR. Mechanically, hyperinsulinemia plays a role in reducing the heart's ability to take in glucose, decreasing the heart's energy production, and increasing the production of lipids, and reactive oxygen species, which further impairs heart cells [12]. IR and hyperinsulinemia may form a positive feedback loop, and when both are present, they can more aggressively promote CVD [12]. In addition, Stidsen et al. discovered that individuals with type 2 diabetes with the hyperinsulinaemic phenotype were at the greatest risk of CVD, particularly due to an elevated likelihood of heart failure, CVD death, and overall mortality [15]. The present study extended this scope to the NGT and prediabetes population and found that the hyperinsulinemic subtype showed more prominent associations with the risk of CVD and death in NGT than in prediabetes. We assume this is because individuals in the prediabetes subgroup would be influenced by other risk factors rather than the hyperinsulinaemic subtype, like hypertension and dyslipidaemia, and thus the independent risk of the hyperinsulinaemic subtype would be attenuated by these factors, which was consistent that the baseline characteristics table showed that prediabetes had more percentage of hypertension and higher levels of blood lipids compared with NGT.

Sensitivity analyses further strengthened the robustness of our results. First, none of the subgroups, which included characteristics such as sex, age, and hypertension showed any significant changes in the associations, which implies that our findings are applicable to most individuals. Second, the cutoffs of the median were primarily used from the present cohort due to the racial/ethnic differences in IR and β-cell function [46, 47]. To further enhance the robustness of our results, the analyses were duplicated based on different cutoffs of the median HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S values (HOMA2-S: 63.5% and HOMA2-B: 115.3%) measured in a non-diabetic background cohort random sampled from all residents of southern Denmark region (360,921 persons), as previously described [16]. Consistently, the present study observed that the classical subtype was associated with the highest risk of kidney function decline, and the hyperinsulinemic subtype was associated with the highest risk of fatal CVD, nonfatal CVD events, and all-cause mortality compared with other physiological subtypes. The RCS analyses showed that high levels of HOMA2-B and low levels of HOMA2-S were associated with increased risk of fatal CVD events and all-cause mortality, which was consistent with the result that the hyperinsulinemic subtype with high HOMA2-B and low HOMA2-S was associated with the highest risk of these outcomes. As for we observed non-significant association between HOMA2-B and risk of kidney function decline and nonfatal CVD events, we assumed that this is because the RCS method was limited by their inability to differentiate between the independent effects of HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S for the risk of the outcomes, which also highlights the importance of conducting integrative analyses by classifying physiological subgroups according to both HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S.

The present study is methodologically and clinically important and novel. The strengths of this study are as follows. First, this is the first to investigate the relationships between physiologic subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity and the risk of kidney function decline, CVD, and all-cause mortality. Previous studies were limited by the inability to assess insulin sensitivity and β-cell activity concurrently and were unable to differentiate between the effects of IR and β-cell function [6-13]. Second, this study is the first attempt to extend the investigation to diverse glucose tolerance statuses including NGT and prediabetes, and found the physiological subgroups based on HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S can identify people at high or low risk of kidney function decline, CVD, and all-cause mortality in those with NGT and prediabetes, respectively and the associations were more prominent in NGT than in prediabetes. Third, physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices of β-cell function and insulin sensitivity are more cost-effective and practical. In contrast, the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp technique is the gold standard for assessing insulin resistance [48–50]. However, due to the relatively long time and complex procedure it requires, it is not practical for routine clinical use or large-scale studies [48–50]. This rudimentary categorization based on the physiologic factors has not been previously explored and may be readily implemented in a clinical setting, as it is grounded on a single fasting sample of blood glucose and insulin. Fourth, to further strengthen the results, two methods to calculate eGFR were used: the Chinese MDRD [31, 32] and the CKD-EPI [31, 33] formulas. After recognizing the inadequacies of plasma creatinine and 24-hour creatinine clearance, the recommended use of estimates of GFR calculated from prediction equations based on plasma or serum creatinine emerged [51–53]. Ying-Chun Ma et al. reported a method and concluded that the accuracy of their modified MDRD equations based on data that were obtained from Chinese patients with CKD was better than that of the original MDRD equations in Chinese patients with CKD and provided clinicians with the opportunity to estimate GFR more accurately. In addition, the CKD-EPI equation is more accurate than the MDRD method and is generally considered the best method for estimating GFR in most clinical settings due to its accuracy across a wide range of GFR levels and diverse populations [51–53].

The present study also has several limitations. First, it is important to consider the constraints of the HOMA2 calculator when interpreting our findings. This calculator only offers measurements of the steady-state insulin sensitivity and β-cell function, which are derived from the fasting insulin and glucose tests [14]. In addition, HOMA2 is unable to assess a functional response [14]. Nevertheless, the gold standard tests, such as the hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic clamp and the hyperglycaemic clamp, are impractical for large-scale epidemiological investigations. As a result, HOMA2 has been proposed as a suitable alternative for use in such studies. Additionally, the steady-state/non-prandial phase, which represents the baseline level of β-cell function/insulin sensitivity, is clinically significant since individuals spend a significant part of the day in this phase. Second, the relatively short follow-up duration reduced the number of clinical outcome events and affected the statistical power, but our findings were nonetheless meaningful. This needs to be confirmed in different populations in the future. Third, although numerous potential confounders were adjusted for, other unknown or unmeasured variables might have impacted the associations between physiological subtypes based on HOMA2 indices and the risk of outcomes. Hence, further investigations have to include more extensive sample sizes and extended follow-up durations. Fourth, it is important to note that this study only focused on people of Chinese ethnicity who were 40 years old or older. Therefore, further research in other countries and across different age groups is needed to confirm these findings.

Conclusions

This retrospective cohort study revealed that physiological subgroups based on HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S can identify people at high or low risk of kidney function decline, CVD, and all-cause mortality. The classical subtype had the strongest correlation to the risk of kidney function decline, and the hyperinsulinemic subtype had the highest risk of CVD and all-cause mortality. Furthermore, we extended the investigation to diverse glucose tolerance statuses including NGT and prediabetes. The method of physiological subtypes based on HOMA2-B and HOMA2-S has the potential to enhance the treatment and prognosis for the patients of precision medicine. It might shield people who naturally have a low risk from receiving unneeded therapy and can indicate improved and more accurate treatment for patients with hyperinsulinemia, as we have demonstrated that they are at a notably high risk.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Zhangping Li in the clinical laboratory of the Division of Endocrinology for their contributions to collecting and handling samples.

Abbreviations

- 4C

The China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort

- ALT

Alanine transaminase

- ANOVA

Analysis of variance

- AST

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CKD

Chronic kidney disease

- CKD-EPI

The CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DBP

Diastolic blood pressure

- FPG

Fasting plasma glucose

- GGT

Gamma-glutamyl transferase

- HR

Hazard ratio

- HbA1c

Glycated hemoglobin

- HDL-C

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HOMA

The Homeostasis model assessment

- HR

Hazard ratio

- IQI

Interquartile interval

- IR

Insulin resistance

- LDL-C

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- MDRD

The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease

- NGT

Normal glucose status

- OGTT

Oral glucose tolerance test

- PG2h

2-h plasma glucose

- RCS

Restricted cubic spline

- ROC

Receiver operating characteristic

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SD

Standard deviation

- STROBE

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Research in Epidemiology

- TC

Total cholesterol

- WC

Waist circumference

- WHR

Waist-hip ratio

Author contributions

XY and PL designed the study. YG, DL, XM, RK, SW, and YH collected the data. PL performed the statistical analysis. XY and PL wrote the paper. YX, BM, LP, YY, ZL, JX, BZ, WH, SH, and XZ reviewed the paper and provided suggestions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions of the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82470907, 82270880).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Committee on Human Research at Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiaotong University School of Medicine and Tongji Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology approved the study protocol (Numbers: 14/2004 and TJ-IRB20231125). All participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic Kidney Disease Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1238–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kishi S, Kadoya H, Kashihara N. Treatment of chronic kidney disease in older populations. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Chen N, Ma LL, Zhang Y, Chu X, Dong J, Yan YX. Association of long-term triglyceride-glucose index patterns with the incidence of chronic kidney disease among non-diabetic population: evidence from a functional community cohort. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024;23(1):7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazancioglu R. Risk factors for chronic kidney disease: an update. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2013;3(4):368–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flora GD, Nayak MK. A brief review of Cardiovascular diseases, Associated Risk factors and current treatment regimes. Curr Pharm Des. 2019;25(38):4063–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song SH, Goo YJ, Oh TR, Suh SH, Choi HS, Kim CS et al. Insulin resistance is associated with incident chronic kidney disease in population with normal renal function. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ke Z, Wen H, Huang R, Xu X, Yang K, Liu W, et al. Long-term insulin resistance is associated with frailty, frailty progression, and cardiovascular disease. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2024;15(4):1578–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lin Z, Yuan S, Li B, Guan J, He J, Song C, et al. Insulin-based or non-insulin-based insulin resistance indicators and risk of long-term cardiovascular and all-cause mortality in the general population: a 25-year cohort study. Diabetes Metab. 2024;50(5):101566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen R, Lin L, Bin Z, Qiao X. The U-shape relationship between insulin resistance-related indexes and chronic kidney disease: a retrospective cohort study from national health and nutrition examination survey 2007–2016. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2024;16(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Kim GS, Kim SG, Kim HS, Hwang EY, Lee JH, Yoon H. The relationship between chronic kidney function and homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance and beta cell function in Korean adults with or without type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr J. 2017;64(12):1181–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schroijen MA, de Mutsert R, Dekker FW, de Vries APJ, de Koning EJP, Rabelink TJ, et al. The association of glucose metabolism and kidney function in middle-aged adults. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(11):2383–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang H, He S, Wang J, An Y, Wang X, Li G, et al. Hyperinsulinemia and plasma glucose level independently associated with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in Chinese people without diabetes-A post-hoc analysis of the 30-year follow-up of Da Qing diabetes and IGT study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;195:110199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia RG, Rincon MY, Arenas WD, Silva SY, Reyes LM, Ruiz SL, et al. Hyperinsulinemia is a predictor of new cardiovascular events in Colombian patients with a first myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol. 2011;148(1):85–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kristensen FPB, Christensen DH, Callaghan BC, Stidsen JV, Nielsen JS, Hojlund K, et al. The prevalence of Polyneuropathy in type 2 diabetes subgroups based on HOMA2 indices of beta-cell function and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2023;46(8):1546–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stidsen JV, Christensen DH, Henriksen JE, Hojlund K, Olsen MH, Thomsen RW, et al. Risk of cardiovascular events associated with pathophysiological phenotypes of type 2 diabetes. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;187(2):279–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stidsen JV, Henriksen JE, Olsen MH, Thomsen RW, Nielsen JS, Rungby J, et al. Pathophysiology-based phenotyping in type 2 diabetes: a clinical classification tool. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34(5):e3005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Selen DJ, Edelson PK, James K, Corelli K, Hivert MF, Meigs JB, et al. Physiological subtypes of gestational glucose intolerance and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226(2):241. e1–e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP, et al. The strengthening the reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zou H, Xu Y, Chen X, Yin P, Li D, Li W, et al. Predictive values of ANGPTL8 on risk of all-cause mortality in diabetic patients: results from the REACTION study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19(1):121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu J, Bi Y, Wang T, Wang W, Mu Y, Zhao J, et al. The relationship between insulin-sensitive obesity and cardiovascular diseases in a Chinese population: results of the REACTION study. Int J Cardiol. 2014;172(2):388–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bi Y, Lu J, Wang W, Mu Y, Zhao J, Liu C, et al. Cohort profile: risk evaluation of cancers in Chinese diabetic individuals: a longitudinal (REACTION) study. J Diabetes. 2014;6(2):147–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ning G, Reaction Study G. Risk evaluation of cAncers in Chinese diabeTic individuals: a lONgitudinal (REACTION) study. J Diabetes. 2012;4(2):172–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ning G, Bloomgarden Z. Diabetes and cancer: findings from the REACTION study: REACTION. J Diabetes. 2015;7(2):143–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasouli N, Younes N, Ghosh A, Albu J, Cohen RM, DeFronzo RA, et al. Longitudinal effects of glucose-lowering medications on beta-cell responses and insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetes: the GRADE Randomized Clinical Trial. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(4):580–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gong L, Wang C, Ning G, Wang W, Chen G, Wan Q, et al. High concentrations of triglycerides are associated with diabetic kidney disease in new-onset type 2 diabetes in China: findings from the China Cardiometabolic Disease and Cancer Cohort (4 C) study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(11):2551–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu J, Wang S, Li M, Gao Z, Xu Y, Zhao X, et al. Association of serum bile acids profile and pathway dysregulation with the risk of developing diabetes among normoglycemic Chinese adults: findings from the 4 C study. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):499–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zou H, Xu Y, Meng X, Li D, Chen X, Du T, et al. Circulating ANGPTL8 levels and risk of kidney function decline: results from the 4 C study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20(1):127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cacciatore S, Calvani R, Marzetti E, Coelho-Junior HJ, Picca A, Fratta AE, et al. Predictive values of relative fat mass and body mass index on cardiovascular health in community-dwelling older adults: results from the longevity check-up (Lookup) 7. Maturitas. 2024;185:108011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woolcott OO, Bergman RN. Relative fat mass (RFM) as a new estimator of whole-body fat percentage a cross-sectional study in American adult individuals. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Zhu Y, Zou H, Guo Y, Luo P, Meng X, Li D, et al. Associations between metabolic score for visceral fat and the risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality among populations with different glucose tolerance statuses. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;203:110842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang D, Hu X, Jin H, Liu J, Chen X, Qin Y, et al. Impaired kidney function and the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease among Chinese hypertensive adults: using three different equations to estimate the glomerular filtration rate. Prev Med. 2024;180:107869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma YC, Zuo L, Chen JH, Luo Q, Yu XQ, Li Y, et al. Modified glomerular filtration rate estimating equation for Chinese patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(10):2937–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang J, Guan J, Huang L, Li X, Huang B, Feng J, et al. Sex differences in the associations between relative fat mass and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: a population-based prospective cohort study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2024;34(3):738–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ding C, Li J, Wei Y, Fan W, Cao T, Chen Z et al. Associations of total homocysteine and kidney function with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in hypertensive patients: a mediation and joint analysis. Hypertens Res. 2024. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.McHugh ML. Multiple comparison analysis testing in ANOVA. Biochem Med (Zagreb). 2011;21(3):203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee S, Lee DK. What is the proper way to apply the multiple comparison test? Korean J Anesthesiology. 2018;71(5):353–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grubbs V, Lin F, Vittinghoff E, Shlipak MG, Peralta CA, Bansal N, et al. Body mass index and early kidney function decline in young adults: a longitudinal analysis of the CARDIA (coronary artery risk development in young adults) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(4):590–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagayama D, Watanabe Y, Yamaguchi T, Fujishiro K, Suzuki K, Shirai K, et al. Relationship of serum lipid parameters with kidney function decline accompanied by systemic arterial stiffness: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Kidney J. 2023;16(11):2289–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qin X, Wang Y, Li Y, Xie D, Tang G, Wang B, et al. Risk factors for renal function decline in adults with normal kidney function: a 7-year cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2015;69(8):782–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cui C, Liu L, Zhang T, Fang L, Mo Z, Qi Y, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index, renal function and cardiovascular disease: a national cohort study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakashima A, Kato K, Ohkido I, Yokoo T. Role and Treatment of Insulin Resistance in patients with chronic kidney disease: a review. Nutrients. 2021;13(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Liao MT, Sung CC, Hung KC, Wu CC, Lo L, Lu KC. Insulin resistance in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2012;2012:691369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kong YL, Shen Y, Ni J, Shao DC, Miao NJ, Xu JL, et al. Insulin deficiency induces rat renal mesangial cell dysfunction via activation of IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(2):217–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stewart AJ, Tuncay E, Pitt SJ, Rainbow RD. Editorial: insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1266173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raygor V, Abbasi F, Lazzeroni LC, Kim S, Ingelsson E, Reaven GM, et al. Impact of race/ethnicity on insulin resistance and hypertriglyceridaemia. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2019;16(2):153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hasson BR, Apovian C, Istfan N. Racial/Ethnic differences in Insulin Resistance and Beta cell function: relationship to racial disparities in type 2 diabetes among African americans versus caucasians. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4(2):241–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Linn W, Persson M, Rathsman B, Ludvigsson J, Lind M, Andersson Franko M, et al. Estimated glucose disposal rate is associated with retinopathy and kidney disease in young people with type 1 diabetes: a nationwide observational study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2023;22(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoshida D, Ikeda S, Shinohara K, Kazurayama M, Tanaka S, Yamaizumi M et al. Triglyceride-glucose Index Associated with future renal function decline in the General Population. J Gen Intern Med. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Liu XC, He GD, Lo K, Huang YQ, Feng YQ. The triglyceride-glucose index, an insulin resistance marker, was non-linear Associated with all-cause and Cardiovascular Mortality in the General Population. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:628109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levey AS, Inker LA, Coresh J. GFR estimation: from physiology to public health. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):820–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Delanaye P, Cavalier E, Pottel H, Stehle T. New and old GFR equations: a European perspective. Clin Kidney J. 2023;16(9):1375–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Delanaye P, Pottel H, Cavalier E, Flamant M, Stehle T, Mariat C. Diagnostic standard: assessing glomerular filtration rate. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2024;39(7):1088–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.