Abstract

Introduction

Quality of life (QOL) and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in children and adolescents with food allergies have been an important and steadily growing field of research for the past 20 years. There seem to be conceptual and methodological challenges that might influence the face validity of QOL and HRQOL research in general health research, but this has not been investigated in pediatric and adolescent food allergy research up until now. The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review of the QOL and HRQOL studies on food allergy in children and adolescents under the age of 18.

Methods

The systematic review was conducted on studies purporting to measure QOL or HRQOL in children and adolescents with food allergies. The literature search was developed in Ovid MEDLINE and databases used in the review were Embase, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, CINAHL, and Scopus. Studies were evaluated based on a set of face validity criteria developed by Gill and Feinstein in 1994 and refined by Moons et al. in 2004.

Results

Out of 61 studies eligible for the review, 11 (18%) defined QOL or HRQOL and two distinguished QOL from HRQOL. The Food Allergy Quality of Life (FAQLQ) instrument series is the most frequently used HRQOL measurement among the studies included. QOL and HRQOL were employed interchangeably in half of the studies, some of them also using a third term in addition.

Conclusion

Our findings lead to the conclusion that the research field investigated contains methodological and conceptual shortcomings regarding QOL and HRQOL. An increased awareness toward the terminology as well as consideration of points to reflect upon will be beneficial, as this will also improve the validity of future studies.

Keywords: Quality of life, Health-related quality of life, Food allergy, Children, Systematic review

Introduction

For the last 20 years, the quality of life (QOL) and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) have been an object of research on children and adolescents with food allergies (FAs) [1]. FA is affecting up to 10% of children and adolescents worldwide although with great regional variety [2, 3]. The condition has a wide range of symptoms spanning from mild to life-threatening [4]. The mortality rate due to anaphylaxis is low [5]. Allergies in children often continue into adulthood, implying that this is a chronic condition [6]. As of today, there are few treatment options for FAs. Children and teens with FA must be strictly adherent to an elimination diet and the use of rescue medication including epinephrine injector treatment if accidentally exposed to an allergen. All the above-mentioned factors suggest that QOL and HRQOL research on children and adolescents with FAs will provide important information on the impact of FA. Research has shown that the (HR)QOL of children and adolescents with FA is negatively affected as compared with healthy controls, as well as to children and adolescents with other chronic diseases [1, 7–10]. The risk of accidental exposure to an allergen may lead to anxiety, insecurity, and lack of full participation in social events, which again can reduce (HR)QOL in children and adolescents [7, 11]. HRQOL is considered the best and maybe only meaningful outcome measure to FA because of the low mortality rate and mainly absence of physical symptoms, the subjective nature of FA illness perception, and the lack of alternative measures [5, 12–15]. Furthermore, measuring HRQOL in food-allergic individuals can be used to identify specific needs for support [14, 16]. Moreover, QOL and HRQOL serve as essential treatment outcomes on several levels; for the individual patient, for planning and optimizing clinical healthcare, and impacting political decision making on a national level [17, 18]. Thus, assessments of (HR)QOL in children and adolescents will give benefits on both individual and societal levels.

HRQOL derives from QOL, which is a broader concept. A large variety of definitions exists, and there seems to be no consensus regarding conceptualization, operational definition, or measurement [19, 20]. The QOL construct usually encompasses economic, cultural, material, societal, and health factors. To narrow the QOL content into health-specific matters, the HRQOL term was developed. HRQOL is multidimensional, containing symptoms, treatment effects and side effects, functional status, and perception of health and well-being [21, 22]. One of the conceptual HRQOL models contains five overarching domains: biological function, symptoms, functional status, general health perceptions, and overall QOL [22]. A further distinction between the QOL and HRQOL models is the emphasis of the two concepts; in QOL models, health and HRQOL constitute one of many domains, while in the HRQOL models, overall QOL comprises one of several pillars, the others all being health-related [20].

Several studies indicate that (HR)QOL in health research have conceptual and methodological issues, not being defined and/or measured properly [19, 23–25]. This is likely to affect the validity of the studies [26]. A conceptual framework for assessing QOL research was developed by Gill and Feinstein [23]. They hypothesized QOL as a reflection of how “patients perceive and react to their health status and to other, nonmedical aspects of their lives” [23 p. 619]. With the lack of a unified operational definition of QOL, they address the need of researchers delineating what they mean by QOL, and which domains the researchers investigate. They suggest that both an overall QOL rating as well as rating the importance of individual items affecting the patients’ QOL is needed for properly measuring QOL, and that reasons for QOL and HRQOL instrument choice must be presented [23]. Their work resulted in the development of ten criteria meant to assess the face validity of QOL studies. The criteria have later been elaborated and refined by Moons and colleagues [19], see Table 1. Gill and Feinstein define face validity evaluation as “the application of enlightened common sense,” a combination of ordinary common sense with relevant pathophysiological and clinical knowledge [23 p. 620].

Table 1.

The face validity criteria of Gill and Feinstein as refined by Moons et al. [19]

| 1. Did the investigators give a definition of QOL? |

| 2. Did the investigators state the domains they will measure as components of QOL? |

| 3. Did the investigators give reasons for choosing the instruments they used? |

| 4. Did the investigators aggregate results from multiple items, domains, or instruments into a single composite score for QOL? |

| 5. Were patients asked to give their own global rating for QOL? |

| 6. Was overall QOL distinguished from health-related QOL? |

| 7. Were patients invited to supplement the items listed in the instruments offered by the investigators that they considered relevant for their QOL? |

| 8. If so, were these supplemental items incorporated into the final rating? |

| 9. Were patients allowed to indicate which items were personally important to them? |

| 10. If so, were the importance ratings incorporated into the final rating? |

There are several validation studies on the development of HRQOL and QOL instruments in FA research, but to our knowledge no review studies have been conducted investigating the conceptual rigor in FA (HR)QOL research. Several reasons for performing an assessment exist: there is no established curative treatment for FA, for many this is a life-long condition, where HRQOL is seen as the most important outcome of FA, and FA has been found to impose a great economic burden both individually and societally worldwide [27, 28].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to perform a systematic review of the QOL and HRQOL studies on FA in children and adolescents under the age of 18. We did this using the 10 face validity criteria of Gill and Feinstein.

We posed the following research questions:

-

1.

What definitions of QOL are commonly utilized in research on FA among children and adolescents?

-

2.

Which measures are used to assess QOL and HRQOL within these studies?

-

3.

How do the definitions of QOL and HRQOL align with the measurement techniques utilized in the studies?

-

4.

How do the included studies fare in terms of methodological and conceptual rigor, as per the research criteria outlined by Gill and Feinstein (1994)?

We also wanted to describe the study population, study design, country of origin, instruments used, and context, as well as methodological quality.

Methods

This systematic literature review is performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement (PRISMA) checklist [29]. The study protocol has been registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (ID: CRD42022370416) [30].

Search Strategy

The first and last author in collaboration with an experienced medical librarian built a comprehensive and systematic search strategy in Ovid MEDLINE using medical subject headings (MESH) and text words. The search strategy was discussed with the other authors and tested. The final search strategy was adapted for the databases Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and CINAHL. The literature search was performed on July 15th, 2022, and the search strategy for all the databases is described in the supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000539113).

Papers published from inception until July 15th, 2022, in English, Danish, Swedish and Norwegian or with English abstracts were considered. After using the EndNote V.X9™ software for the removal of duplicates, the search resulted in 1,300 publications.

Selection Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed a priori. Inclusion criteria were (1) QOL or HRQOL mentioned in title or abstract; (2) FA topic mentioned in title or abstract; (3) children and adolescents under the age of 18; (4) use of quantitative QOL or HRQOL measurement instruments; (5) peer-reviewed article; (6) original research; (7) published in English or a Scandinavian language. Exclusion criteria were (1) study participants not including individuals under the age of 18; (2) food intolerances or non-IgE-mediated FAs; (3) studies only on parents of children and adolescents with FA; (4) publications not utilizing QOL or HRQOL measurement instruments; (5) methodological studies; (6) other study designs and publication types: all kinds of review articles, statement articles, letters, brief communications, gray literature, case studies, qualitative literature, protocols; (7) non-peer-reviewed articles.

Data Selection Process

The articles from the primary literature search were randomly divided into two parts. Two pairs of authors (HA + AKW; MHL+SH), independently screened one of the two parts, based on title and abstract. The Rayyan™ software [31] was employed for primary screening and selection. Each pair read in full half of the articles included from the primary screening to assess the diversity of methodologies. They then met to discuss criteria and a consensus was reached on factors determining high-quality research and eligibility for inclusion.

Data Charting

A standardized data charting form was developed. This contained study design, population, country of origin, QOL/HRQOL measurement instrument, the use of self-report and proxy report forms, the identification of terms (QOL or HRQOL) used in the paper, and setting. One author extracted data, whilst another checked the accuracy of the extracted data. In cases of disagreement, the first author (H.A.) made the final call.

We used the main articles as foundation for the face validity evaluations as well as the demographic data obtained. Further, we used the main articles + online supplementaries for the quality appraisals.

Included study designs will be presented as stated in the original papers (in online suppl. Table 1). Studies where authors solely mentioned to have “sent out questionnaires,” were categorized with not stating any design.

An age delineation for the study population was made at 18 years. This implies that instruments solely measuring QOL of adult people with allergy or parental QOL were excluded from presentations. The Child Health Questionnaire-Parent Form (CHQ-PF) instrument contains questions about parental QOL factors in addition to being a proxy instrument and was therefore included in the review. We categorized age-specific instruments as “unspecified” if the article authors only stated that the instrument exists in several versions without declaring which one they made use of.

The frequency of instruments used in the publications was calculated based on each instrument series (e.g., Even if both Food Allergy Quality of Life Questionnaire-Child Form (FAQLQ-CF) and FAQLQ-Parent Form (FAQLQ-PF) were used in one study, the instrument frequency is (1). This also counts for the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) series. Not all articles utilize HRQOL or QOL instruments, but if the article authors stated that they used these instruments for measuring HRQOL or QOL we chose to include them.

Gill and Feinstein Criteria

The Moons et al. [19] refinement of the ten Gill and Feinstein criteria was utilized for assessing the face validity of the studies. These ten criteria consist of eight “yes” or “no” criteria, with two additional criteria (8 and 10) being triggered only if answering “yes” to criteria 7 and/or 9. To fulfill criterion one, the QOL or HRQOL definition had to be presented in the introduction chapter. A pragmatic adjustment was made to criterion two; as long as the authors stated the domains of the instruments, we concluded they adhered to the criterion.

Quality Appraisal

All publications underwent a quality assessment using appraisal forms appropriate to the study design. In cases where the study design was not stated explicitly by the authors, we performed a pragmatic categorization based on the wording of the research aims and methods used, while at the same time keeping the number of quality instruments used to a minimum. The publications were treated the same way as during primary screening; first scored independently, then discussed in pairs (HA + AKW, HA + MHL or AKW+MHL) until consensus.

The Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment tool (ROB2) [32] was employed for randomized controlled trials (RCTs), while the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Checklist for Quasi-experimental Studies [33] was applied to studies with a quasi-experimental design. For studies with a cross-sectional design, we applied the JBI Checklist for Analytical Cross-sectional Studies [34]. Cohort studies were evaluated with the JBI Checklist for Cohort Studies [34], while case-control studies were measured with the JBI Checklist for Case-Control Studies [34]. A high number of “yes” in the JBI checklists indicate better methodological quality.

Synthesis of Results

Numbers and percentages were summarized and calculated using Microsoft Excel™ (version 16). A summary score of the Gill and Feinstein criteria was made by dividing the number of adhered criteria by the number of eligible criteria, multiplying the result by 100. If none of the criteria were fulfilled the score was 0, and the highest obtainable score was 100. Microsoft Excel was furthermore used to overview the review process and also for plotting the quality appraisal.

Results

Characteristics of the Included Studies

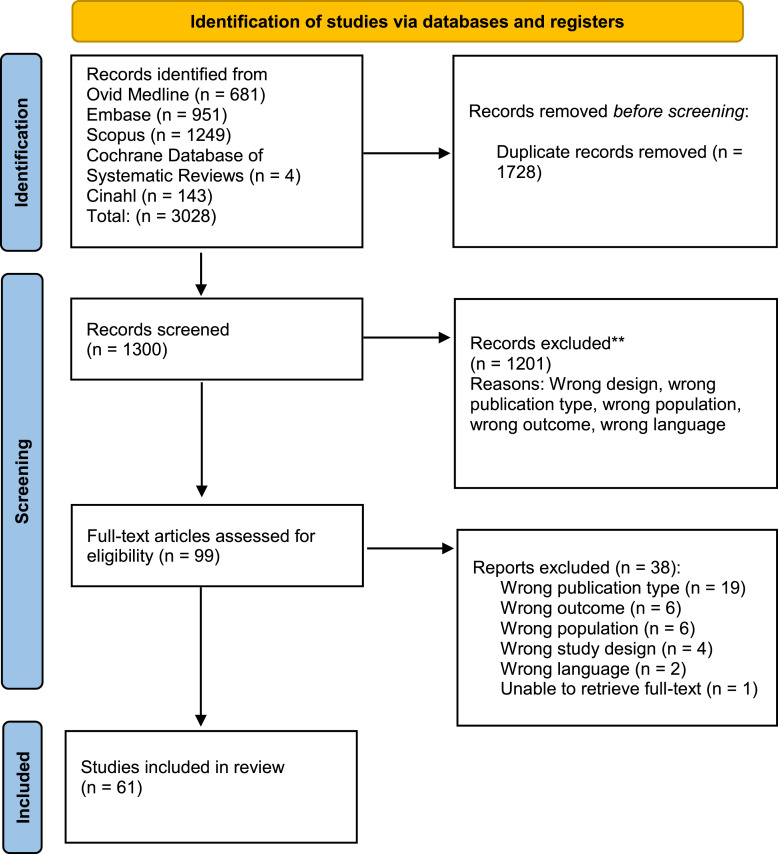

The database search yielded 3,128 results. After 1,828 duplicates were removed, titles and abstract for 1,300 publications were screened, excluding 1,201 articles. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 99 articles were read in full text. Another 38 studies were excluded during this process, leaving 61 studies eligible for this review. See Figure 1 for the inclusion flowchart.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of inclusion from: Page et al. [29]

The 61 articles were published from 2001 to 2022. They had a QOL or HRQOL outcome as common denominator, and the study populations all had FAs, whether specified or not. There were four publications deriving from two studies, by Flokstra de-Blok et al. [10, 35] and Roy and colleagues [36, 37], meaning the number of unique studies was 59.

35 of the studies (57.4%) included had a cross-sectional design [8–10, 35–66]; 18 studies (29.5%) were experimental, involving either an RCT (n = 9) [67–75] or a quasi-experimental design (n = 9) [76–84]. The sample also consisted of five cohort studies (8.2%) [85–89] and three case-control studies (4.9%) [90–92]. For detailed information about each study, see online supplementary Table 1.

As shown in online supplementary Table 2, the studies were mainly conducted in Western Europe and the USA, with 13 of the studies (21.3%) performed in the USA. Of the 61 publications, 36 publications (59%) were European; 10 were from United Kingdom (16.4%), nine of the studies were Swedish (14.8%), seven were from the Netherlands (11.5%), three were from Ireland (4.9%). Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Norway, and Switzerland all had one study each. There were 7 studies performed in Asia; in Israel (n = 5; 8.2%), Japan (n = 1), and Saudi Arabia (n = 1). One study was conducted in Australia. There were four multicenter studies (6.5%).

The total number of participants was 17,045, with sample sizes ranging from 13 [89] to 3,236 [41]. 30 of the publications (49.2%) included children of 0–5 years, 51 of the publications (83.6%) entailed children of 6–12 years of age, 35 of the publications (57.4%) included adolescents 13–17 years, eight of the publications also included adults, and 15 of the publications (24.6%) included parent-QOL. 44 of the studies (72.1%) contained proxy submissions, whereas 19 of these (31.1%) had only proxy submissions. The settings were mainly hospitals or specialist clinics; some recruited via allergy support groups, while other studies were birth cohort or regional based cohort studies.

When it comes to terminology, the results are divided into 4 quite equal parts; 16 of the included studies (26.2%) employed the QOL term consistently throughout their study [9, 43, 49, 51, 66, 67, 74, 77, 78, 82, 85, 87–91], while 17 studies (27.9%) pertained to the HRQOL term [10, 35, 41, 44, 46, 48, 50, 53–56, 59, 62–64, 86, 92]. Both QOL and HRQOL were applied by 15 of the studies (24.6%) [8, 36–40, 45, 47, 52, 57, 60, 61, 65, 68, 75], while 13 studies (21.3%) used the term “food allergy-related QOL” or “food allergy QOL” in addition to either QOL or HRQOL [8, 42, 58, 69–73, 76, 79–81, 83, 84].

A total of 23 different QOL or HRQOL instruments were used (see Table 2), with the FAQLQ instrument series being the most commonly used (n = 76). Disease-specific instruments were employed 84 times, while generic QOL instruments were utilized 34 times with PedsQL as the most frequent of the latter instrument type. Altogether, QOL instruments were employed 118 times, as 15 of the publications (24.6%) applied more than one instrument. 23 of the publications included the Food Allergy Independent Measure (FAIM) [93].

Table 2.

QOL and HRQOL instruments

| Instruments | Frequency, no. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Disease-specific | ||

| FAQLQ-CF | 19 | 16.1 |

| FAQLQ-TF | 20 | 16.9 |

| FAQLQ-PF | 31 | 26.3 |

| FAQLQ-PFT | 3 | 2.5 |

| FAQLQ-10-CF | 1 | 0.8 |

| FAQLQ-10-TF | 1 | 0.8 |

| FAQLQ-10-PF | 1 | 0.8 |

| Self-designed by Avery/PFA-QL | 5 | 4.2 |

| Adapted from Vespid QoL allergy questionnaire | 1 | 0.8 |

| QOL questions generated toward peanut allergy | 1 | 0.8 |

| FAIS | 1 | 0.8 |

| Total | 84 | |

| Generic | ||

| PedsQL 4.0, unspecified | 7 | 5.9 |

| PedsQL 4.0 small children | 2 | 1.7 |

| PedsQL 4.0 children | 4 | 3.4 |

| PedsQL 4.0 Teenagers | 4 | 3.4 |

| PedsQL parent-proxy report | 3 | 2.5 |

| PedsQL family Impact | 1 | 0.8 |

| CHQ-PF28 | 3 | 2.5 |

| CHQ-PF50 | 1 | 0.8 |

| CHQ-CF87 | 4 | 3.4 |

| EQ-5D | 3 | 2.5 |

| EQ-5D-Y (proxy 1) | 1 | 0.8 |

| KIDSCREEN-52 | 1 | 0.8 |

| Total | 34 | |

Gill and Feinstein Criteria Assessment

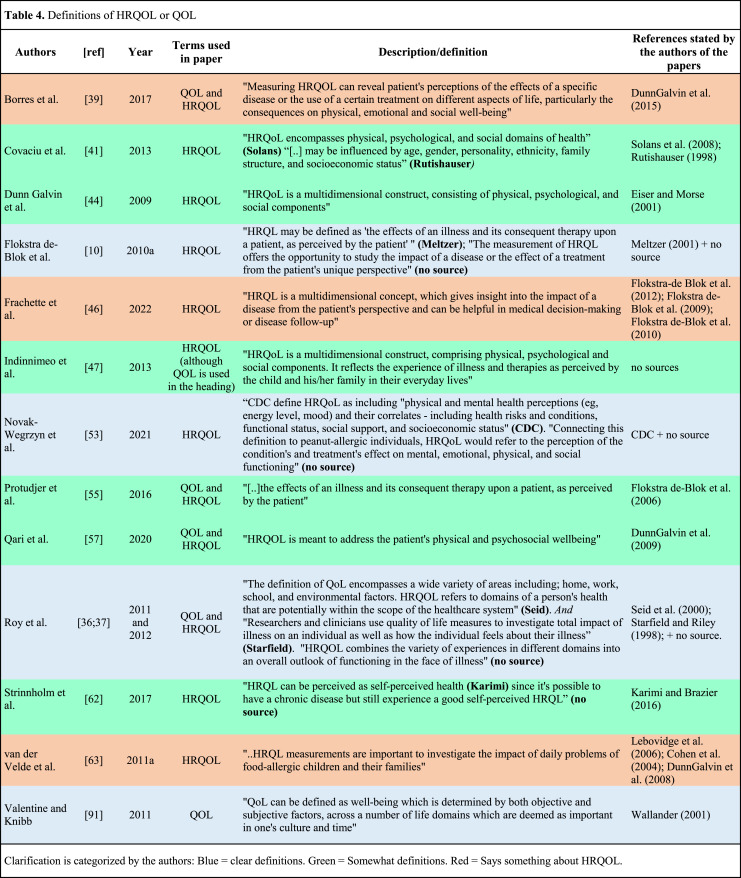

Evaluation of the studies according to Gill and Feinstein’s criteria (shown in Table 3) revealed that 11 of the studies (18%) provided a clear definition of the concept QOL or HRQOL (criterion 1). Altogether fourteen studies either defined (with or without references) or mentioned something about what (HR)QOL is or what it can be used for (see Table 4).

Table 3.

Evaluation of studies according to the face validity criteria of Gill and Feinstein

| Authors | [ref] | Year | 1. Definition of QOL/HRQOL? | 2. Domains stated? | 3. Reasons for choosing instrument? | 4. Aggregate results into single score? | 5. Could patients provide a global rating of QOL? | 6. Overall QOL and HRQOL distinguished? | 7. Patients invited to supplement items? | 8. If adherence to item 7, Incorporated into final rating? | 9. Could patients rate personally important items? | 10. If adherence to item 9, incorporated into final rating | Summary score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acaster et al. | [38] | 2020 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Anagnostou et al. | [67] | 2014 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Avery et al. | [8] | 2003 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | NA | 22.22 |

| Blackman et al. | [85] | 2020 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Blümchen et al. | [68] | 2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Borres et al. | [39] | 2017 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Burrell et al. | [86] | 2021 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Chow et al. | [40] | 2015 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Covaciu et al. | [41] | 2013 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 37.5 |

| Cummings et al. | [42] | 2010 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| d’Art et al. | [69] | 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Danchin et al. | [76] | 2016 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Dantzer et al. | [70] | 2022 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Dilley et al. | [43] | 2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| DunnGalvin et al. | [44] | 2009 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 37.5 |

| DunnGalvin et al. | [71] | 2021 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Epstein Rigbi et al. | [45] | 2016 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Epstein Rigbi et al. | [79] | 2017 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Authors | [ref] | Year | 1. Definition | 2. Domains | 3. Instrument reasoning | 4. Result aggregation | 5. Global QOL rating | 6. QOL/HRQOL distinction | 7. Item supplementation | 8. If; included in final rating | 9. Personally important items | 10. If; included in final rating | Sum score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epstein Rigbi et al. | [87] | 2019 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Epstein Rigbi et al. | [78] | 2020 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Epstein Rigbi et al. | [77] | 2021 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Fernandez-Rivas et al. | [80] | 2022 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Flokstra-de Blok et al. | [10] | 2010a | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 50 |

| Flokstra-de Blok et al. | [35] | 2010b | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Frachette et al. | [46] | 2022 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Hamada et al. | [88] | 2021 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Hourihane et al. | [81] | 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Hourihane et al. | [72] | 2020 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Indinnimeo et al. | [47] | 2013 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 50 |

| Jonsson et al. | [48] | 2021 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Kelleher et al. | [73] | 2013 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| King et al. | [49] | 2009 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Knibb et al. | [90] | 2012 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Knibb and Hourihane | [82] | 2013 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Marklund et al. | [50] | 2006 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Miller et al. | [51] | 2020 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Morou et al. | [52] | 2021 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Nowak-Wegrzyn et al. | [53] | 2021 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 50 |

| Protudjer et al. | [54] | 2015 | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 37.5 |

| Protudjer et al. | [55] | 2016 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 50 |

| Protudjer et al. | [56] | 2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Qari et al. | [57] | 2020 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 37.5 |

| Reier-Nilsen et al. | [74] | 2019 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Roy and Roberts | [36] | 2011 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 37.5 |

| Roy et al. | [37] | 2012 | + | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 50 |

| Saleh-Langenberg et al. | [58] | 2015 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Saleh-Langenberg et al. | [59] | 2016 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Shemesh et al. | [60] | 2013 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Shemesh et al. | [75] | 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Sicherer et al. | [9] | 2001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 0 |

| Stensgaard et al. | [61] | 2017 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 12.5 |

| Strinnholm et al. | [62] | 2017 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 37.5 |

| Valentine and Knibb | [91] | 2011 | + | + | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 50 |

| van der Valk et al. | [83] | 2016 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| van der Velde et al. | [63] | 2011a | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 37.5 |

| van der Velde et al. | [64] | 2011b | 0 | + | + | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 37.5 |

| van der Velde et al. | [84] | 2012 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Venter et al. | [65] | 2015 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Wassenberg et al. | [66] | 2012 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Yee et al. | [89] | 2019 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Östblom et al. | [92] | 2008 | 0 | + | 0 | + | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | 0 | NA | 25 |

| Total | 11 | 43 | 9 | 57 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Table 4.

Definitions of HRQOL or QOL

|

Identification of domains to be studied, criterion 2, was made by 43 of the studies (70.5%). Nine studies (14.8%) stated reasons for choosing the selected instruments, pertaining to criterion 3. 57 of the studies (93.4%) had aggregated results from items, domains, or instruments into a single composite score for QOL, according to criterion 4. None of the studies gave the patients the opportunity to give their own global rating for QOL (criterion 5). Two of the studies (3.3%) distinguished overall QOL from HRQOL (criterion 6).

One study (1.6%), by Avery et al. [8], adhered to criterion 7, inviting patients to supplement the items listed in the instruments with that they considered relevant for their QOL. This was the only study applicable to criterion 8, which it did not adhere to. None of the studies adhered to criterion 9, and because of that none of the studies were applicable for criterion 10.

Calculations of the summary score demonstrated that none of the studies scored higher than 50 points of 100 possible. Six of the studies (9.8%) reached the second highest quartile of 50–74 points, 36 (59%) of the studies were in the second lowest quartile, and finally 19 of the studies (31.1%) scored 0 or 12.5 points (see Table 3).

Quality Appraisal Results

Thirty one of the included studies (50.8%) stated a clear research design in the introduction or methods section, while the remaining 30 (49.2%) were sorted based on the considerations mentioned in the methods section. For the 35 studies assessed with the 8 item JBI checklist for cross-sectional studies (see Table S3), we found six of the studies fulfilled the criteria for six “yes” scores, this was the highest number of “yes.” Five of the studies were deemed to have a total of two “yes,” and one study only one “yes.” The remaining studies scored 3 to 5 “yes.” When looking at the 8 domains, 29 of the studies fulfilled the clearly defined inclusion criteria, while only nine of the studies identified confounding factors.

Among the nine studies assessed with the ROB2 tool (shown in Fig. S1), the overall risk of bias was deemed as “low” in one of the studies [68], and “some concern” in another one of the studies [75], while it was evaluated to be a high risk of bias in the remaining seven of the studies. The nine-item JBI checklist for quasi-experimental studies applied to 9 of the studies included (see Table S4). One study fulfilled all nine criteria [80]; two studies were deemed to fulfill eight “yes” [77, 78]; another two studies scored seven “yes”; three studies scored 5 “yes,” while one study had 4 “yes” [79].

Five studies were assessed with the eleven-item JBI checklist for cohort studies (Table S5). Three of the studies had 5 “yes,” while the remaining two studies had 4 “yes.”

Three studies were identified as case-control studies, and the JBI checklist specific for this study design, containing 10 items, was applied (see Table S6). Two studies had 6 “yes,” while one scored 3 “yes” [91].

Discussion

The aim of this study was to perform a systematic review of the QOL and HRQOL studies on FA in children and adolescents under the age of 18. Our review shows that the studies have methodological issues, fulfilling few of the face validity criteria developed by Gill and Feinstein [23].

Discussion of Findings Related to the Criteria of Gill and Feinstein

Essential to the findings is that only eleven of the studies provided a definition of QOL or HRQOL. An additional three studies mention the potential of measuring HRQOL. This leaves the vast majority of the studies not mentioning anything about what they define as QOL or HRQOL or why they choose to measure one of them. Although varied, the HRQOL definitions largely tend to include physical, social, and psychological components, which is in line with the HRQOL model by Ferrans et al. [22] presented in the introduction.

We did find a large proportion of studies disclosing the domains they measure as QOL/HRQOL components (criterion 2). Only a small share presented the domains properly in the introduction chapter, while the vast majority briefly listed the domains when describing the content of the selected QOL/HRQOL instrument. However, drawing a definite line to how much information was needed for adhering to the criterion proved difficult. We therefore chose to approve all studies mentioning anything about domains, although this could give a false impression of awareness. QOL and HRQOL might sound like intuitive terms, but as the variety of definitions and definitional content are diverse, the domains are what operationalize and give the chosen term a specific meaning. Without appraising the domains, it is hard to know if they really measure what they intend to, which again is a serious threat to validity.

One way to adjust for not stating domains is to disclose the reasons for instrument choice (criterion 3). A thorough disclosure can at the same time reveal which domains are to be investigated, as the instrument should measure the matters of interest to the researchers. Hence, it is important to express this in precise order, as only stating the instrument domains as reasons may be misread as pronounced and comprehensive concepts of investigation. In our assessment of criterion 3, we relied on the refinement of Moons et al. [19] and approved of those who gave more thorough reasons than “good instrument validity.” One of the studies explains their choice of using a generic HRQOL questionnaire with that it “is useful for determining the relative burden of the disease, as well as for making comparisons between different diseases” such as different allergic conditions [39].

Both HRQOL and QOL instruments are being used in the FA research realm according to this review. EAACI advocates for the use of disease-specific questionnaires, as they are the only ones sensitive enough to detect small changes in the HRQOL on an individual level [14], and this review reveals a distribution of about 70/30 in favor of disease-specific instruments. Of the disease-specific instruments in our review, only the FAQLQ series is properly validated to be used in research according to EAACI [14].

Our results on instrument use correspond with the recommendations of the EAACI position paper; however, we find it important to note that the application of disease-specific questionnaires makes HRQOL incomparable to other diseases or to healthy individuals [94]. The choice of instrument should therefore also rely on the aim of the study, another argument for stating the reasons.

When it comes to distinguishing QOL from HRQOL (criterion 6), only two studies adhered to this [53, 91]. The variety of terminology is, although not a part of the Gill and Feinstein criteria, also an issue. Half of the studies employed both the QOL and the HRQOL term within the same publications, and half of these studies again even employed another term in addition to the two others: “food allergy (related) QOL” (FA-QOL). Using this term truly condenses the researchers’ scope to the disease itself, but as we did not succeed in finding a definition on FA-QOL, the meaning of the term is unclear. The developers of the FAQLQs label the series “food allergy quality of life questionnaire(s),” hence the FAQLQ abbreviation [95–97], which may be the origin of the FA-QOL term. However, they purport to measure HRQOL [95–97]. A consciousness about measuring HRQOL or QOL is another requirement for choosing the right instrument. If QOL questionnaires are used when purporting to measure HRQOL, one might overestimate the impact of nonmedical issues [23].

Most of the questionnaires in the included studies generate an overall score of the QOL based on the sum score of each domain. This is in compliance with criterion 4. The overall score gives information on either the disease-specific or the generic HRQOL of the study population, but there are several things it does not provide any information about, for instance the actual value of an overall score. None of the questionnaires in the review, neither disease-specific nor generic, offers the opportunity to provide a global rating of QOL (criterion 5). A global rating can give information about how big of an impact living with a FA is for the child or adolescent. The concept models of HRQOL and QOL imply that HRQOL can be perceived as good in spite of a burdensome FA, the same way as the general QOL can be good despite a low HRQOL. The Ferrans et al. [22] HRQOL model hypothesize the individual as capable of influencing the HRQOL domains. This is also found in the FA field, where Flokstra-de Blok and colleagues found that patients with the worst disease-specific HRQOL do not necessarily have the worst generic HRQOL [35]. It comes down to the individual’s way of coping and reacting to conditions and events happening in their life. Therefore, the patient should have an opportunity to accentuate items as less or more meaningful, as well as add items of personal importance. This is in line with criteria 7–10 and would be an acknowledgment of the distinct personal preferences and values that constitutes an individual.

Gill and Feinstein calculated a summary score to their ten face validity criteria for a “crude indication” of the articles’ compliance to their criteria [23]. The summary score of the included studies in the present review showed that none of the studies achieved more than 50 points out of 100 possible. Therefore, the top 10% of the studies barely reached the second-highest quartile of 50–74 points. A little more than 30% of the studies belonged to the lowest quartile, scoring between 0 and 24 points. These results do tell a story of low methodological and conceptual awareness in HRQOL and QOL research within the FA realm, but they need to be seen in comparison with other comparable reviews. The original 1994 publication by Gill and Feinstein investigated 75 QOL articles from a variety of health research fields [23]. In that review the lowest quartile consisted of 49% of the studies, 11% of the study selection was in the second highest quartile, and none reached the highest quartile. When looking at the 2015 review by Adunuri et al. [25] of QOL studies on children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, 40% pertained to the lowest quartile, whereas 8% of the studies scored from 50 to 86 points (in this study, the top two quartiles were merged). The current review’s summary score demonstrates better results than the other two. Still, it is noteworthy that the majority of the studies in the present review score less than 49 points.

We suggest following the three recommendations proposed by Gill and Feinstein of using global rating, rating severity and importance, and allowing supplemental items. But in addition, we recommend providing a definition of QOL or HRQOL. With these 4 recommendations, there are good reasons to believe this will lead to an improvement of the face validity in FA QOL and HRQOL research, as well as providing more conceptual clarity, likely making the QOL/HRQOL field a little less confusing to both readers trying to make sense of this realm as well as researchers.

A good definition of HRQOL or QOL will potentially solve many of the face validity issues Gill and Feinstein addressed. As revealed in this discussion, a detailed definition could provide both domains to be investigated, help delineate HRQOL from QOL, and support and clarify reasons for the selection of the instrument.

Discussion of Background Characteristics and Quality Aspects

The studies in the current review are largely conducted on western populations, with most of the publications being from Europe and the USA. These findings are in line with other systematic reviews and scoping reviews on burden, QOL and HRQOL in children and adolescents with FA [98–100]. This brings the level and contents of FA research activity in different parts of the world into question, such as if QOL and HRQOL concepts are of greater interest to Western countries.

It is also a question about the generalizability of the existing literature. HRQOL and QOL are concepts of a subjective nature. Hence, what is important for a good QOL related to FA may differentiate not only on an individual level, but also in various geographic areas, cultures, and different socio-economic settings [101]. This is reflected in the WHO definition of QOL as “an individual’s perception of their position in life, in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns” ([102] p. 1404). According to the EAACI position paper on FA HRQOL measures, the optimal is the use of HRQOL instruments in the same language, cultural setting and age group to which they were developed [14], and we hypothesize this counts for the results of the studies as well. Furthermore, food allergens that may be a dominant part of a staple food diet in Western countries may therefore be nonexistent in Asian or African diets, and QOL studies performed on specific foods may be irrelevant in some parts of the world. This is also emphasized in the EAACI position paper [14]. This identifies a need for an exhaustive literature review accepting all languages.

Nearly one-third of the studies contained proxy assessments only. While proxy assessment is essential to capture the QOL and HRQOL on small children, several of the studies in our review utilized proxy reports exclusively even when the population also consisted of schoolchildren and adolescents. This can be a pragmatic choice regarding feasibility; however, one should be aware of proxy rater issues. A 2017 systematic review reported moderate to poor parent-child agreement in HRQOL assessments, with parents mostly reporting lower HRQOL than their children [103]. Children from 8 years [104], or maybe even as low as 5 years of age and up [105], are capable of self-reporting their HRQOL, and self-report is recommended whenever possible [104].

Our review included multiple study designs, but surprisingly only one-half of the studies stated the research design explicitly, leaving the review authors to fit them into appropriate quality appraisal instruments. This may in some cases have led to studies being measured up against other study designs than intended by the authors, which again potentially could lead to a lower quality score.

Quality appraisals of the studies were performed. We did not succeed in finding any clear cut-off values to whether a study has a high or low risk of bias in the JBI instruments. Still, we deem the quality to be moderate in the cross-sectional and quasi-experimental studies, and low in the case-control and cohort studies. The RCTs mostly had a high risk of bias. As this systematic review was set to review the textual content and instrument choice of the studies included, the methodological quality and risk of bias does not affect the results in this study. It still is a notable addition to the impression of the studies’ methodological validity [106].

Strengths and Limitations

This is a systematic review containing face validity appraisals set out by Gill and Feinstein [23]. Although following guidelines regarding both methodology assessment and quality assessment, there will always be a subjective aspect to critical appraisal. We have performed several interrater assessments in all stages of the review, calibrating and discussing issues as they emerged. This was done to improve the inter-rater reliability, but it will not eliminate the risk of some differentiating evaluations.

One limitation of the study is the choice to not include methods and validation studies in our review. It can be argued that this choice might put QOL and HRQOL research in a bad light, as both the Gill and Feinstein scores and the quality assessment scores might have been higher if those studies were included. This is also supported by the findings of Gill and Feinstein, demonstrating significantly better scores in the three first criteria among the development and validation studies included in their review [23]. Still, this was the very reason we chose not to include those studies; precisely to provide a realistic glimpse of the research performed by clinicians and allergists.

We limited our searches to IgE-mediated FAs, to exclude food intolerances and non-IgE-mediated allergies as they involve other bodily mechanisms and give other symptoms. Venter et al. [65] highlights the difficulties in comparing gastrointestinal symptoms, growth, and anaphylaxis. We discovered that few of the studies specified the allergy to be IgE-mediated, and we had to rely on that the researchers meant IgE-mediated FA when using the term “food allergy.” The EAACI position paper emphasizes that FA-specific HRQOL questionnaires are not suitable for measuring non-IgE-mediated FAs [14]. This is, along with the fact that most of the studies take place in hospital allergy clinics, supporting our faith in the studies treating IgE-mediated FAs.

Conclusion

This systematic review set out to assess the face validity of QOL and HRQOL research on children and adolescents with FA, as this had yet to be investigated. The results demonstrate methodological and conceptual challenges in QOL and HRQOL research on children and adolescents with FA. More awareness and knowledge regarding the HRQOL and QOL concepts would improve the validity of the studies and furthermore contribute to more clarity in the HRQOL and QOL realm. The four recommendations of (1) giving the study participants the opportunity to provide a global rating of QOL, (2) rate severity and importance, (3) allow supplemental items, and (4) provide a definition of QOL or HRQOL could provide a simple way to handle this issue.

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement is not applicable because this study is based exclusively on published literature.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Author Contributions

H.A., M.H.L., S.H., and A.K.W. have all contributed substantially to this paper, have been active reviewers in primary screening, validity appraisals, and quality assessments, and have all participated in the conception and design of the study. H.A. performed the data synthesis and drafted the manuscript, while M.H.L., S.H., and A.K.W. have been critically revising the paper.

Funding Statement

This study was not supported by any sponsor or funder.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. DunnGalvin A, Dubois AE, Flokstra-de Blok BM, Hourihane JO. The effects of food allergy on quality of life. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2015;101:235–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Loh W, Tang MLK. The epidemiology of food allergy in the global context. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(9):2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lyons SA, Clausen M, Knulst AC, Ballmer-Weber BK, Fernandez-Rivas M, Barreales L, et al. Prevalence of food sensitization and food allergy in children across Europe. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(8):2736–46.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Burks AW, Tang M, Sicherer S, Muraro A, Eigenmann PA, Ebisawa M, et al. ICON: food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(4):906–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Turner PJ, Jerschow E, Umasunthar T, Lin R, Campbell DE, Boyle RJ. Fatal anaphylaxis: mortality rate and risk factors. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(5):1169–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy: a review and update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(1):41–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. DunnGalvin A, Hourihane JO. Health-related quality of life in food allergy: impact, correlates, and predictors. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2016;59(7):841–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Avery NJ, King RM, Knight S, Hourihane JO. Assessment of quality of life in children with peanut allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2003;14(5):378–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sicherer SH, Noone SA, Munoz-Furlong A. The impact of childhood food allergy on quality of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2001;87(6):461–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Flokstra-de Blok BM, Dubois AE, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Oude Elberink JN, Raat H, DunnGalvin A, et al. Health-related quality of life of food allergic patients: comparison with the general population and other diseases. Allergy. 2010;65(2):238–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cummings AJ, Knibb RC, King RM, Lucas JS. The psychosocial impact of food allergy and food hypersensitivity in children, adolescents and their families: a review. Allergy. 2010;65(8):933–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flokstra-de Blok BM, Dubois AE. Quality of life measures for food allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(7):1014–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shaker MS, Schwartz J, Ferguson M. An update on the impact of food allergy on anxiety and quality of life. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29(4):497–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Muraro A, Dubois AE, DunnGalvin A, Hourihane JO, de Jong NW, Meyer R, et al. EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines. Food allergy health-related quality of life measures. Allergy. 2014;69(7):845–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Blok BMJ, Dubois AE, Hourihane JO. The impact of food allergy on quality of life. In: Mills ENC, Wichers H, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K, editors. Managing allergens in food. Cambridge: Woodhead publishing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Baiardini I, Bousquet PJ, Brzoza Z, Canonica GW, Compalati E, Fiocchi A, et al. Recommendations for assessing patient-reported outcomes and health-related quality of life in clinical trials on allergy: a GA(2)LEN taskforce position paper. Allergy. 2010;65(3):290–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fayers PM, Machin D. Quality of Life: the assessment, analysis and interpretation of patient-reported outcomes. 2 ed. Chichester: Wiley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Walters SJ. Quality of life outcomes in clinical trials and health-care evaluation: a practical guide to analysis and interpretation. Chichester: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moons P, Van Deyk K, Budts W, De Geest S. Caliber of quality-of-life assessments in congenital heart disease: a plea for more conceptual and methodological rigor. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(11):1062–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):645–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cella D, Stone AA. Health-related quality of life measurement in oncology: advances and opportunities. Am Psychol. 2015;70(2):175–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ferrans CE, Zerwic JJ, Wilbur JE, Larson JL. Conceptual model of health-related quality of life. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37(4):336–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gill TM, Feinstein AR. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA. 1994;272(8):619–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haraldstad K, Wahl A, Andenaes R, Andersen JR, Andersen MH, Beisland E, et al. A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Qual Life Res. 2019;28(10):2641–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Adunuri NR, Feldman BM. Critical appraisal of studies measuring quality of life in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Care Res Hob. 2015;67(6):880–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, et al. The COSMIN study reached international consensus on taxonomy, terminology, and definitions of measurement properties for health-related patient-reported outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(7):737–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fong AT, Ahlstedt S, Golding MA, Protudjer JLP. The economic burden of food allergy: what we know and what we need to learn. Curr Treat Options Allergy. 2022;9(3):169–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Warren CM, Jiang J, Gupta RS. Epidemiology and burden of food allergy. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020;20(2):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Aaneland H, Larsen MH, Helseth S, Wahl AK. Quality of life of children and adolescents with food allergies; a systematic review of the literature. 2022. CRD42022370416. Available from: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42022370416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31. Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sterne JAC, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, Campbell J, Hopp L. Chapter 3: systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis: JBI; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, et al. Chapter 7: systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence Synthesis2020.

- 35. Flokstra-de Blok BM, van der Velde JL, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Oude Elberink JN, DunnGalvin A, Hourihane JO, et al. Health-related quality of life of food allergic patients measured with generic and disease-specific questionnaires. Allergy. 2010;65(8):1031–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roy KM, Roberts MC. Peanut allergy in children: relationships to health-related quality of life, anxiety, and parental stress. Clin Pediatr. 2011;50(11):1045–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roy KM, Roberts MC, Canter KS. Anomalies in measuring health-related quality of life: using the PedsQL 4.0™ with children who have peanut allergy and their parents. Appl Res Qual Life. 2012;8(4):511–8. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Acaster S, Gallop K, de Vries J, Ryan R, Vereda A, Knibb RC. Peanut allergy impact on productivity and quality of life (PAPRIQUA): caregiver-reported psychosocial impact of peanut allergy on children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2020;50(11):1249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Borres N, Nilsson N, Drake I, Sjolander S, Nilsson C, Hedlin G, et al. Parents’ perceptions are that their child's health-related quality of life is more impaired when they have a wheat rather than a grass allergy. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(3):478–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Chow C, Pincus DB, Comer JS. Pediatric food allergies and psychosocial functioning: examining the potential moderating roles of maternal distress and overprotection. J Pediatr Psychol. 2015;40(10):1065–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Covaciu C, Bergstrom A, Lind T, Svartengren M, Kull I. Childhood allergies affect health-related quality of life. J Asthma. 2013;50(5):522–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cummings AJ, Knibb RC, Erlewyn-Lajeunesse M, King RM, Roberts G, Lucas JS. Management of nut allergy influences quality of life and anxiety in children and their mothers. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2010;21(4 Pt 1):586–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dilley MA, Rettiganti M, Christie L, O'Brien E, Patterson M, Weeks C, et al. Impact of food allergy on food insecurity and health literacy in a tertiary care pediatric allergy population. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2019;30(3):363–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. DunnGalvin A, Chang WC, Laubach S, Steele PH, Dubois AE, Burks AW, et al. Profiling families enrolled in food allergy immunotherapy studies. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):e503–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Epstein-Rigbi N, Katz Y, Goldberg MR, Levy MB, Nachshon L, Elizur A. Patient quality of life following induction of oral immunotherapy for food allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(3):263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Frachette C, Fina A, Fontas E, Donzeau D, Hoflack M, Gastaud F, et al. Health-related quality of life of food-allergic children compared with healthy controls and other diseases. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2022;33(1):e13663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Indinnimeo L, Baldini L, De Vittori V, Zicari AM, De Castro G, Tancredi G, et al. Duration of a cow-milk exclusion diet worsens parents’ perception of quality of life in children with food allergies. BMC Pediatr. 2013;13:203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jonsson M, Ekstrom S, Protudjer JLP, Bergstrom A, Kull I. Living with food hypersensitivity as an adolescent impairs health related quality of life irrespective of disease severity: results from a population-based birth cohort. Nutrients. 2021;13(7):2357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. King RM, Knibb RC, Hourihane JO. Impact of peanut allergy on quality of life, stress and anxiety in the family. Allergy. 2009;64(3):461–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Marklund B, Ahlstedt S, Nordstrom G. Health-related quality of life in food hypersensitive schoolchildren and their families: parents’ perceptions. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Miller J, Blackman AC, Wang HT, Anvari S, Joseph M, Davis CM, et al. Quality of life in food allergic children: results from 174 quality-of-life patient questionnaires. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(4):379–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Morou Z, Vassilopoulou E, Galanis P, Tatsioni A, Papadopoulos NG, Dimoliatis IDK. Investigation of quality of life determinants in children with food allergies. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2021;182(11):1058–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Nowak-Wegrzyn A, Hass SL, Donelson SM, Robison D, Cameron A, Etschmaier M, et al. The peanut allergy burden study: impact on the quality of life of patients and caregivers. World Allergy Organ J. 2021;14(2):100512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Protudjer JL, Jansson SA, Ostblom E, Arnlind MH, Bengtsson U, Dahlen SE, et al. Health-related quality of life in children with objectively diagnosed staple food allergy assessed with a disease-specific questionnaire. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(10):1047–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Protudjer JL, Jansson SA, Middelveld R, Ostblom E, Dahlen SE, Arnlind MH, et al. Impaired health-related quality of life in adolescents with allergy to staple foods. Clin Transl Allergy. 2016;6:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Protudjer JLP, Middelveld R, Dahlen SE, Ahlstedt S, FoodHE Investigators . Food allergy-related concerns during the transition to self-management. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2019;15:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Qari YH, Abu Alnasr AA, Bazaid AM, AlHarbi HA, Aljahdali N, Goronfolah LT. The impact of childhood food allergy on quality of life of the paediatric population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Australas Med J. 2020;13(6). [Google Scholar]

- 58. Saleh-Langenberg J, Goossens NJ, Flokstra-de Blok BM, Kollen BJ, van der Meulen GN, Le TM, et al. Predictors of health-related quality of life of European food-allergic patients. Allergy. 2015;70(6):616–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Saleh-Langenberg J, Flokstra-de Blok BM, Goossens NJ, Kemna JC, van der Velde JL, Dubois AE. The compliance and burden of treatment with the epinephrine auto-injector in food-allergic adolescents. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(1):28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Shemesh E, Annunziato RA, Ambrose MA, Ravid NL, Mullarkey C, Rubes M, et al. Child and parental reports of bullying in a consecutive sample of children with food allergy. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e10–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stensgaard A, Bindslev-Jensen C, Nielsen D, Munch M, DunnGalvin A. Quality of life in childhood, adolescence and adult food allergy: patient and parent perspectives. Clin Exp Allergy. 2017;47(4):530–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Strinnholm A, Hedman L, Winberg A, Jansson SA, Lindh V, Ronmark E. Health Related Quality of Life among schoolchildren aged 12-13 years in relation to food hypersensitivity phenotypes: a population-based study. Clin Transl Allergy. 2017;7:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. van der Velde JL, Flokstra-de Blok BMJ, DunnGalvin A, Hourihane JOB, Duiverman EJ, Dubois AEJ. Parents report better health-related quality of life for their food-allergic children than children themselves. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(10):1431–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. van der Velde JL, Flokstra-de Blok BM, Hamp A, Knibb RC, Duiverman EJ, Dubois AE. Adolescent-parent disagreement on health-related quality of life of food-allergic adolescents: who makes the difference? Allergy. 2011;66(12):1580–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Venter C, Sommer I, Moonesinghe H, Grundy J, Glasbey G, Patil V, et al. Health-related quality of life in children with perceived and diagnosed food hypersensitivity. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015;26(2):126–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Wassenberg J, Cochard MM, Dunngalvin A, Ballabeni P, Flokstra-de Blok BM, Newman CJ, et al. Parent perceived quality of life is age-dependent in children with food allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2012;23(5):412–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Anagnostou K, Islam S, King Y, Foley L, Pasea L, Palmer C, et al. Study of induction of Tolerance to Oral Peanut: a randomised controlled trial of desensitisation using peanut oral immunotherapy in children (STOP II). Efficacy Mech Eval. 2014;1(4):1–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Blumchen K, Trendelenburg V, Ahrens F, Gruebl A, Hamelmann E, Hansen G, et al. Efficacy, safety, and quality of life in a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of low-dose peanut oral immunotherapy in children with peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(2):479–91.e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. d'Art YM, Forristal L, Byrne AM, Fitzsimons J, van Ree R, DunnGalvin A, et al. Single low-dose exposure to cow’s milk at diagnosis accelerates cow’s milk allergic infants' progress on a milk ladder programme. Allergy. 2022;77(9):2760–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Dantzer J, Dunlop J, Psoter KJ, Keet C, Wood R. Efficacy and safety of baked milk oral immunotherapy in children with severe milk allergy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(4):1383–91.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. DunnGalvin A, Fleischer DM, Campbell DE, O'B Hourihane J, Green TD, Sampson HA, et al. Improvements in quality of life in children following epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) for peanut allergy in the PEPITES and PEOPLE studies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(1):216–24.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. O'B Hourihane J, Beyer K, Abbas A, Fernandez-Rivas M, Turner PJ, Blumchen K, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral immunotherapy with AR101 in European children with a peanut allergy (ARTEMIS): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(10):728–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kelleher MM, Dunngalvin A, Sheikh A, Cullinane C, Fitzsimons J, Hourihane JO. Twenty four-hour helpline access to expert management advice for food-allergy-triggered anaphylaxis in infants, children and young people: a pragmatic, randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2013;68(12):1598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Reier-Nilsen T, Carlsen KCL, Michelsen MM, Drottning S, Carlsen KH, Zhang C, et al. Parent and child perception of quality of life in a randomized controlled peanut oral immunotherapy trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2019;30(6):638–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Shemesh E, D’Urso C, Knight C, Rubes M, Picerno KM, Posillico AM, et al. Food-allergic adolescents at risk for anaphylaxis: a randomized controlled study of supervised injection to improve comfort with epinephrine self-injection. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(2):391–7.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Danchin M, De Bono N, Allen K, Tang M, Hiscock H. Managing simple food allergy in community settings: a pilot study investigating a new model of care. J Paediatr Child Health. 2016;52(3):315–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Epstein-Rigbi N, Schwartz N, Goldberg MR, Levy MB, Nachshon L, Elizur A. Medical clown support is associated with better quality of life of children with food allergy starting oral immunotherapy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32(5):1029–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Epstein-Rigbi N, Goldberg MR, Levy MB, Nachshon L, Elizur A. Quality of life of children aged 8-12 years undergoing food allergy oral immunotherapy: child and parent perspective. Allergy. 2020;75(10):2623–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Rigbi NE, Goldberg MR, Levy MB, Nachshon L, Golobov K, Elizur A. Changes in patient quality of life during oral immunotherapy for food allergy. Allergy. 2017;72(12):1883–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Fernandez-Rivas M, Vereda A, Vickery BP, Sharma V, Nilsson C, Muraro A, et al. Open-label follow-on study evaluating the efficacy, safety, and quality of life with extended daily oral immunotherapy in children with peanut allergy. Allergy. 2022;77(3):991–1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hourihane JO, Allen KJ, Shreffler WG, Dunngalvin G, Nordlee JA, Zurzolo GA, et al. Peanut Allergen Threshold Study (PATS): novel single-dose oral food challenge study to validate eliciting doses in children with peanut allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(5):1583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Knibb RC, Hourihane JO. The psychosocial impact of an activity holiday for young children with severe food allergy: a longitudinal study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24(4):368–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. van der Valk JP, Gerth van Wijk R, Flokstra-de Blok BM, van der Velde JL, de Groot H, Wichers HJ, et al. No difference in health-related quality of life, after a food challenge with cashew nut in children participating in a clinical trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016;27(8):812–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. van der Velde JL, Flokstra-de Blok BM, de Groot H, Oude-Elberink JN, Kerkhof M, Duiverman EJ, et al. Food allergy-related quality of life after double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenges in adults, adolescents, and children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(5):1136–43.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Blackman AC, Staggers KA, Kronisch L, Davis CM, Anagnostou A. Quality of life improves significantly after real-world oral immunotherapy for children with peanut allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125(2):196–201 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Burrell S, Patel N, Vazquez-Ortiz M, Campbell DE, DunnGalvin A, Turner PJ. Self-administration of adrenaline for anaphylaxis during in-hospital food challenges improves health-related quality of life. Arch Dis Child. 2021;106(6):558–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Epstein-Rigbi N, Goldberg MR, Levy MB, Nachshon L, Elizur A. Quality of life of food-allergic patients before, during, and after oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(2):429–36.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hamada K, Nagao M, Imakiire R, Furuya K, Mizuno Y, Sato Y, et al. Factors associated with outcome of egg allergy 1 year after oral food challenge: a good baseline quality of life may be beneficial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2021;32(7):1490–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Yee CSK, Albuhairi S, Noh E, El-Khoury K, Rezaei S, Abdel-Gadir A, et al. Long-term outcome of peanut oral immunotherapy facilitated initially by omalizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(2):451–61.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Knibb RC, Ibrahim NF, Stiefel G, Petley R, Cummings AJ, King RM, et al. The psychological impact of diagnostic food challenges to confirm the resolution of peanut or tree nut allergy. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42(3):451–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Valentine AZ, Knibb RC. Exploring quality of life in families of children living with and without a severe food allergy. Appetite. 2011;57(2):467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Ostblom E, Egmar AC, Gardulf A, Lilja G, Wickman M. The impact of food hypersensitivity reported in 9-year-old children by their parents on health-related quality of life. Allergy. 2008;63(2):211–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. van der Velde JL, Flokstra-de Blok BM, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Oude Elberink JN, DunnGalvin A, Hourihane JO, et al. Development, validity and reliability of the food allergy independent measure (FAIM). Allergy. 2010;65(5):630–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Guyatt GH, Feeny DH, Patrick DL. Measuring health-related quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(8):622–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. DunnGalvin A, de BlokFlokstra BM, Burks AW, Dubois AE, Hourihane JO. Food allergy QoL questionnaire for children aged 0-12 years: content, construct, and cross-cultural validity. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(6):977–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Flokstra-de Blok BM, DunnGalvin A, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Oude Elberink JN, Duiverman EJ, Hourihane JO, et al. Development and validation of a self-administered food allergy quality of life questionnaire for children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39(1):127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Flokstra-de Blok BM, DunnGalvin A, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Oude Elberink JN, Duiverman EJ, Hourihane JO, et al. Development and validation of the self-administered food allergy quality of life questionnaire for adolescents. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;122(1):139–44.e1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Morou Z, Tatsioni A, Dimoliatis IDK, Papadopoulos NG. Health-related quality of life in children with food allergy and their parents: a systematic review of the literature. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2014;24(6):382–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Cushman GK, Durkin K, Noga R, Cooke F, Herbert L, Esteban C, et al. Psychosocial functioning in pediatric food allergies: a scoping review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;151(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Drakouli AE, Kontele I, Poulimeneas D, Saripanagiotou S, Grammatikopoulou MG, Sergentanis TN, et al. Food allergies and quality of life among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic review. Children. 2023;10(3):433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Antolin-Amerigo D, Manso L, Caminati M, de la Hoz Caballer B, Cerecedo I, Muriel A, et al. Quality of life in patients with food allergy. Clin Mol Allergy. 2016;14:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. WHOQOL group . The world health organization quality of life assessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the world health organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1403–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Hemmingsson H, Olafsdottir LB, Egilson ST. Agreements and disagreements between children and their parents in health-related assessments. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(11):1059–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Petersen-Ewert C, Erhart M, Ravens-Sieberer U. Assessing health-related quality of life in European children and adolescents. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(8):1752–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Matza LS, Patrick DL, Riley AW, Alexander JJ, Rajmil L, Pleil AM, et al. Pediatric patient-reported outcome instruments for research to support medical product labeling: report of the ISPOR PRO good research practices for the assessment of children and adolescents task force. Value Health. 2013;16(4):461–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Booth A, Sutton A, Clowes M, James M. Systematic approaches to a successful literature review. 3 ed.. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2022. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.