Abstract

Summary

Introgression (the flow of genes between species) is a major force structuring the evolution of genomes, potentially providing raw material for adaptation. Here, we present a versatile Bayesian model selection approach for detecting and quantifying introgression, , that builds upon the recently published distance-based statistic. Unlike , accounts for the number of variant sites within a genomic region. The underlying model parameter of our method, here denoted as , accurately quantifies introgression, and the corresponding Bayes Factors () enables weighing the strength of evidence for introgression. To ensure fast computation, we use conjugate priors with no need for computationally demanding MCMC iterations. We compare our method with other approaches including , , , and Patterson’s using a wide range of coalescent simulations. Furthermore, we showcase the applicability of and using whole-genome mosquito data. Finally, we integrate the new method into the powerful genomics R-package PopGenome.

Availability and implementation

The presented methods are implemented within the R-package PopGenome (https://github.com/pievos101/PopGenome) and the simulation as the application results can be reproduced from the source code available from a dedicated GitHub repository (https://github.com/pievos101/Introgression-Simulation).

1 Introduction

Hybridization among species is increasingly recognized as a pivotal evolutionary factor, challenging traditional views of genetic divergence and speciation (Whitney et al. 2006, Soltis and Soltis 2009, Kronforst et al. 2013, Harrison and Larson 2014). Contrary to the long-held view that species boundaries are impermeable, there is mounting evidence suggesting that they are semipermeable (Harrison and Larson 2014) and that resultant gene flow through hybridization plays a crucial role in shaping biodiversity and adaptation (Taylor and Larson 2019). This paradigm shift underscores the need for advanced methods to quantify hybridization and introgression—the transfer of genes between species (Hibbins and Hahn 2022).

The impacts of hybridization, gene flow, and introgression are multifaceted. Traditionally, hybridization was viewed negatively, with immediate fitness consequences for hybrid offspring (Whitlock et al. 2013, Adavoudi and Pilot 2021). Gene flow can decrease genetic differentiation, potentially leading to species loss through genomic swamping (Todesco et al. 2016). However, hybridization and gene flow can lead to introgression, where hybrids exchange genetic material with parental species, which can have negative or positive outcomes for recipient species (Aguillon et al. 2022). Introgression may lead to maladaptation and selection against introgressed DNA (Veller et al. 2023). Conversely, it could facilitate the transfer of adaptive alleles across species boundaries—a process known as adaptive introgression (Whitney et al. 2006, Hedrick 2013, Edelman and Mallet 2021). Paradoxically, introgression can also kick-start increased genetic differentiation between taxa (Edelman and Mallet 2021), creating novel gene combinations or introducing new genes into recipient genomic backgrounds (Barton 2001). Fitness-enhancing introgression can promote local adaptation (Hedrick 2013), facilitate range expansion (Pfennig et al. 2016), and help species respond to changing environments (Brauer et al. 2023). Ultimately, hybridization can contribute to species formation (Abbott et al. 2013) and lead to adaptive radiation (Seehausen 2004, Grant and Grant 2019, Meier et al. 2019).

Before the rise of relatively inexpensive genome-wide sequencing, much of what was known about hybrids was derived from studying phenotypically apparent hybrids found alongside parental species in the field, especially in showy species such as plants, some insects including Lepidoptera, and colorful birds (Mallet 2005). With the rise of next-generation genome sequencing, cases of hybridization and introgression are now widely documented across the entire tree of life (Taylor and Larson 2019, Edelman and Mallet 2021). Numerous tools have been developed to detect introgression at the genome scale, ranging from phylogenetic to population genetic approaches [reviewed in Hibbins and Hahn (2022)].

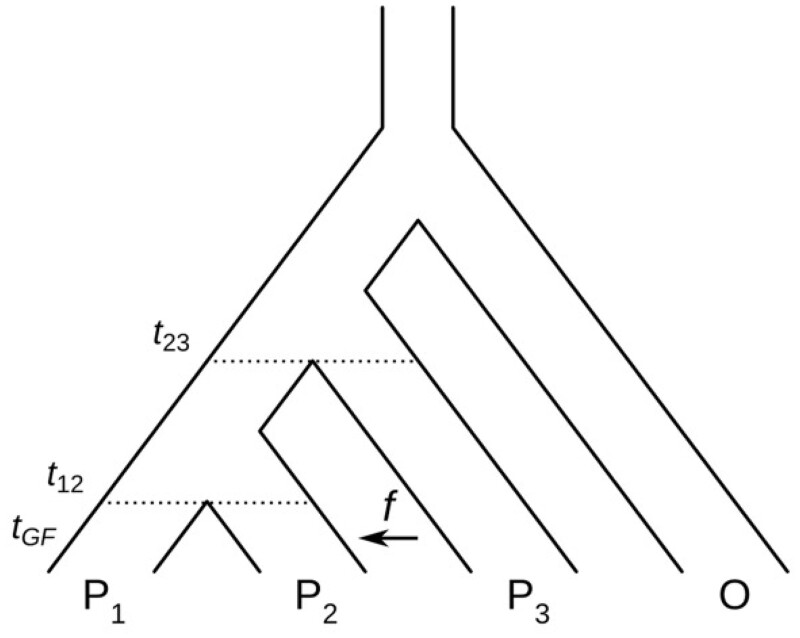

A unique combination of these two approaches derives from the four-taxon (see Fig. 1) test that compares sister species with a third species, and an outgroup (Kulathinal et al. 2009, Green et al. 2010). This method relies on an accounting of Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) patterns arising from the sharing of a derived allele “B” between either member of the sister taxa with the third taxon (pattern “ABBA” indicates sharing between taxa P2 and P3, or “BABA” sharing between taxa P1 and P3). An excess of ABBA or BABA patterns is taken as evidence of introgression over the alternative of incomplete lineage sorting (Reich et al. 2010, Durand et al. 2011). Patterson’s D summarizes the imbalance of ABBA to BABA sites, indicating hybridization (Durand et al. 2011, Patterson et al. 2012).

Figure 1.

A four-taxon phylogenetic tree illustrating introgression between taxon 3 () and taxon 2 (). The time of gene flow is indicated by , with the fraction of introgression f. The illustration is modified from Martin et al. (2015)

However, it is now well understood that the D-statistic is biased, as it does not vary linearly with the fraction of introgression. Furthermore, when applied to smaller genomic regions, the D-statistic tends to overestimate the numbers of regions across the genome deemed introgressed, particularly in cases where reduced heterozygosity can lead to false positives (Martin et al. 2015).

Pfeifer and Kapan (2019) recognized that reduced genetic distance between taxa, an entirely obvious genomic signal of introgression, could be placed in the ABBA-BABA framework, to derive new measures of hybridization that did not suffer from the pitfalls of Patterson’s D. This paradigm shift underscores the need for advanced methods to quantify introgression in genomes (Hibbins and Hahn 2022), as understanding the dynamics of hybridization becomes imperative in unraveling the intricacies of evolutionary processes. Here, we extend the work of Pfeifer and Kapan (2019) by enhancing the distance statistic with Bayesian estimation.

We present a versatile Bayesian model selection approach for detecting and quantifying introgression, , which builds upon the distance-based statistic (Pfeifer and Kapan 2019). Unlike , accounts for the number of variant sites within a genomic region. The method quantifies introgression with the inferred parameter and simultaneously enables weighing the strength of evidence for introgression based on Bayes Factors. We employ conjugate priors, which eliminate the need for computationally demanding MCMC iterations to ensure fast computation.

The article is structured as follows: Section 2 briefly reviews the statistic and Section 3 introduces our new Bayesian approach. We evaluate this approach through simulations based on previous research on introgression levels and numeric experiments involving maximally introgressed SNPs. This allows us to emphasize the impact of population size and the genomic scale of measurement. The corresponding simulation setup is detailed in Section 4. Results from these simulations are presented in Section 5, which also includes an application to real-world data.

2 The statistic

The statistic (Pfeifer and Kapan 2019), an estimator of the proportion of introgression, is formulated as

| (1) |

where , , and represent SNP sharing patterns on a four-taxon tree, which we show can be expressed in terms of genetic distance:

| (2) |

where refers to the mutant allele frequency in population at variant site . Here, is the average pairwise nucleotide difference between population and population at variant site . is the total number of bi-allelic sites in a genomic region. The first two taxa are closely related species the third taxon is a potential donor of mutant allele at variable sites, and the fourth taxon refers to the outgroup as in the original work by Patterson (Green et al. 2010). Note, that the statistic calculates the fraction of introgression based on variant sites where the outgroup (taxon 4) is monomorphic for allele . From Equation (2), it can be seen that when either = ) or = ) is zero, the statistic estimate is 1 or −1, respectively. This can generate false positives in low diversity regions, e.g. in low recombining regions comprising only a few bi-allelic markers. This issue is not unique to the statistic, it applies to other ABBABABA methods, such as (Martin et al. 2015), and Patterson’s since they do not explicitly account for the number of bi-allelic sites.

To tackle this problem, we transform the statistic into a Bayesian model selection problem.

3 New approach

We define two competing models of introgression.

Models and can be conceptually represented by the following likelihood functions for the observed data :

| (3) |

| (4) |

The parameter in model includes information about the fraction of the data explained by the ABBA+BBAA () patterns. In model , captures the BABA+BBAA () signals. The parameter includes the species tree pattern BBAA (), which is used as an approximate measure of the neutral (non-introgressed) signal within the data (for more details, see Pfeifer and Kapan 2019). We perform Bayesian inference over the parameter space of conjugate Beta distributions with , which assumes a process proportional to a binomial likelihood [see Equations (3) and (4)]. The shape parameters are , , and , computed from the data using the logic. The expected value of the computed Beta posterior distribution is our new estimate of introgression, here denoted as .

The Bayesian model assumes that the observed data can be approximately explained by the species tree pattern (BBAA) plus the corresponding introgression frequency patterns (ABBA and BABA). We use the following conjugate Beta distribution as a prior

| (5) |

| (6) |

where is the initial guess for no introgression evidence, adjusting the sensitivity to the actual observed signals of introgression in the data. To form the posterior, we use the following updating scheme of the Beta distribution per variant site

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

where is a scaling factor that we set to the average population size of , , and . The corresponding posterior density distributions of the models and are

| (10) |

| (11) |

where is the inferred Beta model parameter to quantify the gene flow between (model ) and (model ). Finally, evidence of introgression is calculated using Bayes Factors as

| (12) |

allowing researchers to judge the relative merit of the two competing introgression models. We scaled the obtained likelihood fractions in Equation (12) using the exponential function so that the resulting Bayes Factors can be interpreted according to Jeffreys (Jeffreys 1939). See Table 1 for an overview of these values.

Table 1.

Jeffreys’ scale for Bayes Factors interpretation.

| Bayes Factor (BF) | Strength of evidence |

|---|---|

| 1 | No evidence |

| Anecdotal evidence | |

| Moderate evidence | |

| Strong evidence | |

| Very strong evidence | |

| Extreme evidence |

It should be noted again that the BBAA pattern is included in both and [see Equations (3) and (4)]. This is true for both models, and , and thus we are performing inference on the [0.5,1] theta range. Therefore, a transformation back into the full theta range [0,1] is required to estimate the fraction of introgression. We define as

| (13) |

In our software implementation, the parameter can optionally be set to negative values when (indicating introgression between and , model supported), while it remains positive when (indicating introgression between and , model supported). This flexibility allows the user to reflect the most highly supported model of introgression based on the combination of and the posterior support for the introgression model, which is especially useful when graphing the results of the calculations.

Given the described mathematical model we can quantify the fraction of introgression and at the same time verify the supporting strength of the signal using Bayes Factors.

4 Simulation set-up

To validate our approach, we follow our previous simulation setup (Pfeifer and Kapan 2019) built upon that presented by Martin et al. (2015).

First, we generated topologies with different levels of introgression using Hudson’s ms program (Hudson 2002). It is extensively utilized for simulating genetic variation data, specifically SNP data, by randomly sampling haplotypes from a population. Users can customize several parameters related to population demography, such as population sizes and migration patterns, as well as evolutionary factors like mutation, crossover, and gene conversion rates.

Second, the sequence alignments were produced by the seq-gen program (Rambaut and Grass 1997). Seq-Gen is a versatile program designed to simulate the evolution of nucleotide or amino acid sequences along a phylogeny, employing various substitution models, including the general reversible model. Users can specify parameters like state frequencies and incorporate site-specific rate heterogeneity in multiple ways. The program accommodates the input of multiple trees, generating numerous datasets for each tree, making it suitable for creating extensive sets of replicate simulations. Overall, Seq-Gen serves as a general-purpose simulator, encompassing commonly used and computationally tractable models of molecular sequence evolution.

We generated 5 kb sequences with split times , , and generations ago. The time of gene flow from to was set to generations ago with a fraction of introgression of . The recombination rate was set to , and the Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano substitution model was employed, utilizing a branch scaling factor of . We varied the fraction of introgression and the time of gene flow . For each set-up, we repeated the simulation 100 times and for each run we computed , Patterson’s (Patterson et al. 2012), (Martin et al. 2015), (Hamlin et al. 2020), and (Pfeifer and Kapan 2019). Detailed guidance for generating synthetic data using ms and seq-gen is provided on our GitHub repository (https://github.com/pievos101/Introgression-Simulation).

In addition to the above-described simulation, to study how values are affected by changes in population size, the prior , and the number of SNPs supporting the simulated signal, we modeled a single SNP with maximal possible introgression () from to . We set minor allele frequencies to , , and and proceeded to study these effects based on this single marker and copies of that marker.

5 Results and discussion

5.1 Simulations

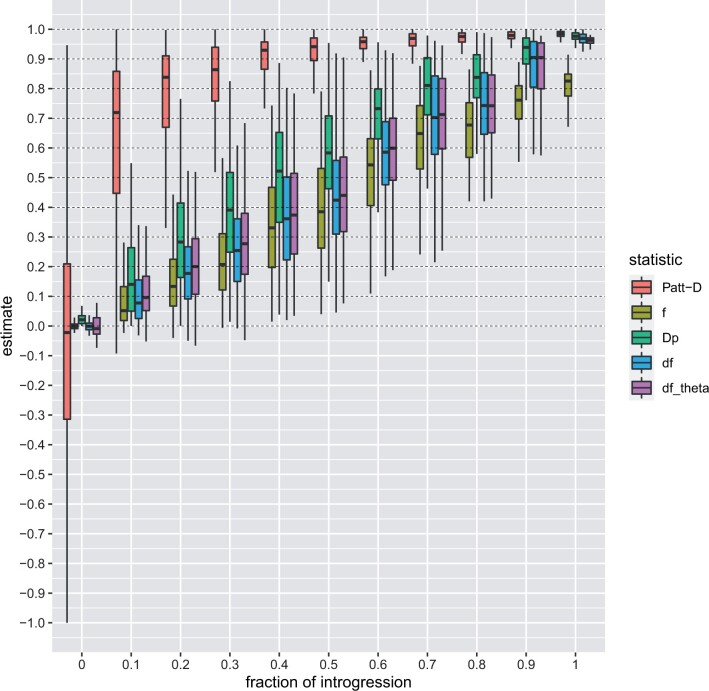

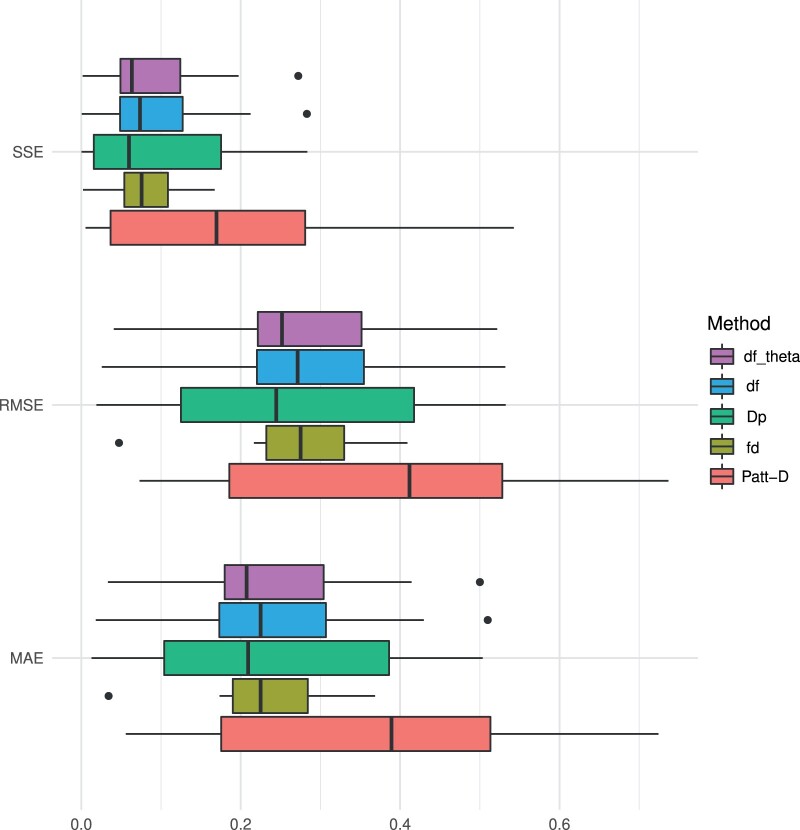

The results based on synthetic data show that reliably estimates introgression and quantifies the evidence of introgression versus the null model. Figure 2 displays the results of our experiments when varying the fraction of introgression from population to . The model parameter (denoted as ) precisely quantifies the fraction of introgression and produces almost identical results as the statistic (see Fig. 2). Patterson’s greatly overestimates the fraction of introgression on the whole spectrum. The method tends to underestimate the fraction of introgression, especially when introgression is strong (Fig. 2). In Figure 3, we report on the Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). The model parameter consistently outperforms the competing methods for all metrics when the median is used for comparison. These results indicate that performs best across the spectrum of possible levels of introgression.

Figure 2.

Simulation results—the fraction of introgression. Results comparing estimators Patterson’s D, , , , and for varying levels of introgression. The horizontal dashed lines refer to the real fraction of introgression

Figure 3.

Simulation results—the fraction of introgression. The metrics Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values of the statistics Patterson’s D, , , , and (bottom to top) over all simulated data with varying levels of introgression

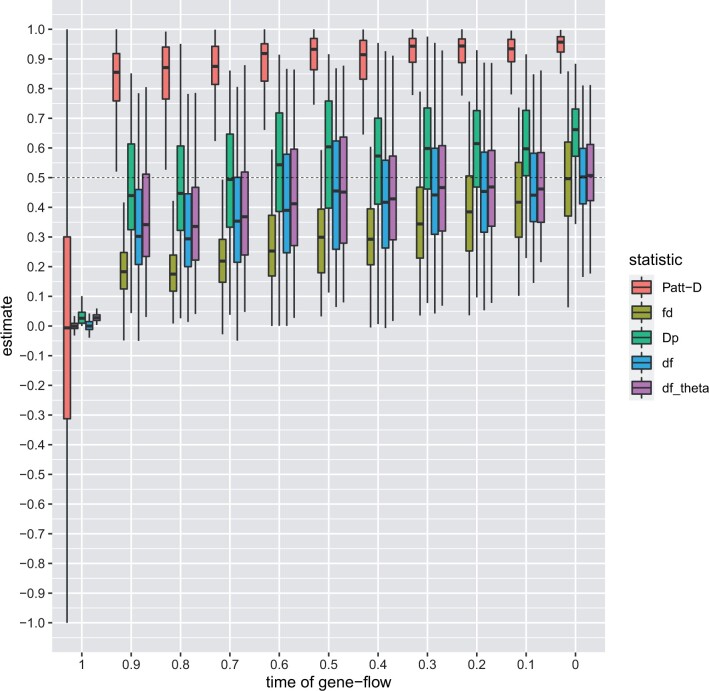

We also varied the time of gene flow. We could confirm the results reported by Pfeifer and Kapan (2019); is nearly unaffected by the time of gene flow, and quantifies the fraction of introgression more accurately compared to Patterson’s and . Here, we report the same properties for (see Fig. 4). When varying the time of gene flow (Figs 4 and 5) and are the best-performing estimates of introgression. is more accurate for low levels of introgression, while is a much better estimator when the signal of gene flow is strong. Furthermore, Fig. 4 shows that strongly underestimates the introgression. Again, the values based on Patterson’s are inflated.

Figure 4.

Simulation results—time of gene-flow. Results of the statistics Patterson’s D, , , , and on simulated data with varying time of gene-flow (). The horizontal dashed line refers to the real simulated fraction of introgression ()

Figure 5.

Simulation results—time of gene flow. The metrics Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) values of the statistics Patterson’s D, , , , and (bottom to top) over all simulated data with varying the time of gene-flow (). The fraction of introgression f is set to 0.5

Introgression statistics, including , are influenced by evolutionary factors such as branch lengths and effective population sizes, as demonstrated in Pfeifer and Kapan (2019). Further development utilizing the Bayesian framework introduced here offers promise to address these additional evolutionary effects.

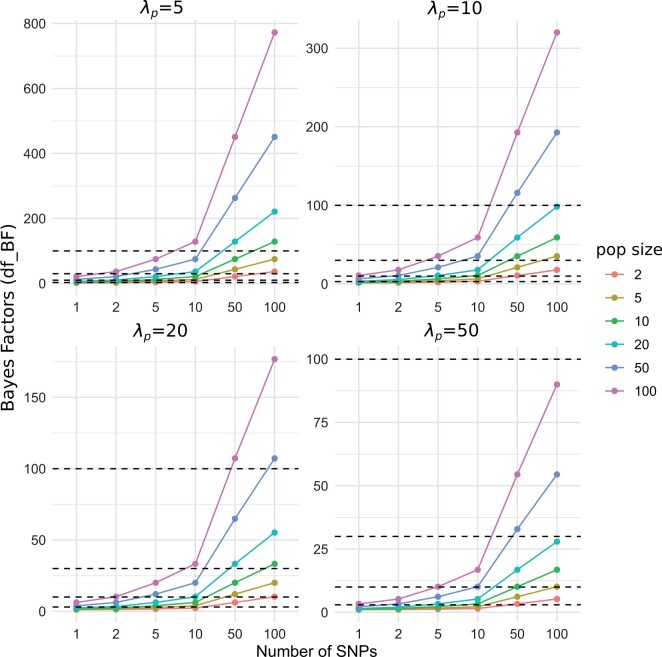

Moreover, we extensively examined the scaling characteristics of the Bayes Factors. We simulated maximal possible introgression (), varied the number of SNPs within a genomic region supporting that signal, and investigated the influence of the population size accordingly. Figure 6 reveals the scaling of the values are dependent on the prior , , and the corresponding values. When is set to the average population size () it results in an overly conservative test. With this specific setting, very-strong evidence of introgression () is obtained with 50 consecutive SNPs supporting complete introgression. With this critical value is already reached with 10 SNPs. The prior-specific values can be adjusted by the user as a flexible parameter within our provided software implementation, with Fig. 6 providing guidance. For example, with an average population size of 100, a researcher might view 10 consecutive SNPs under complete introgression as a very strong indication of introgression (). Figure 6 demonstrates that in this scenario, strong evidence is achieved using a prior-specific , as indicated in the upper right panel.

Figure 6.

Change in values as a function of varying the average population size (), priors (), and the number of SNPs supporting the signal of introgression. The fraction of introgression is for each set-up. The horizontal dashed lines refer to the critical values according to Jeffrey’s Table (see Table 1)

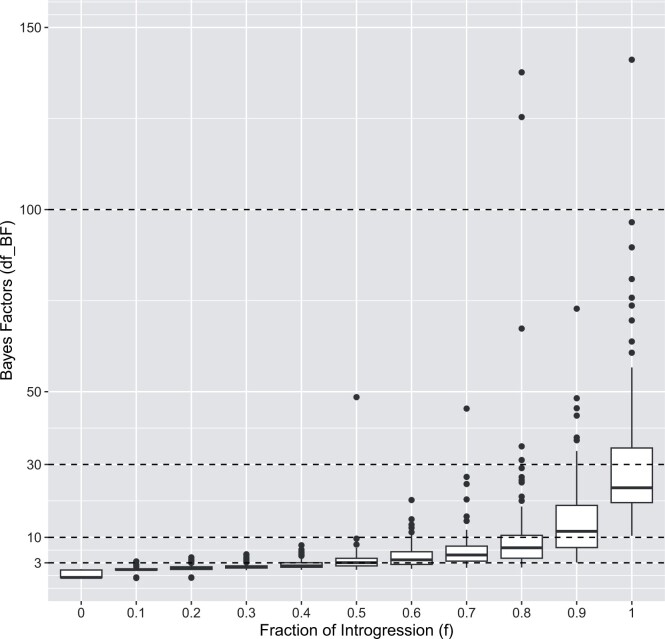

The displayed Bayes Factors in Fig. 7 correspond to the simulated data shown in Fig. 2. With the current default parameter setting strong evidence of introgression is reported when the fraction of introgression is >0.8.

Figure 7.

Bayes Factors () for simulated data with varying levels of introgression. The horizontal dashed lines refer to the critical values according to Jeffrey’s Table (see Table 1). The displayed Bayes Factors correspond to the simulated data shown in Fig. 2

5.2 Application

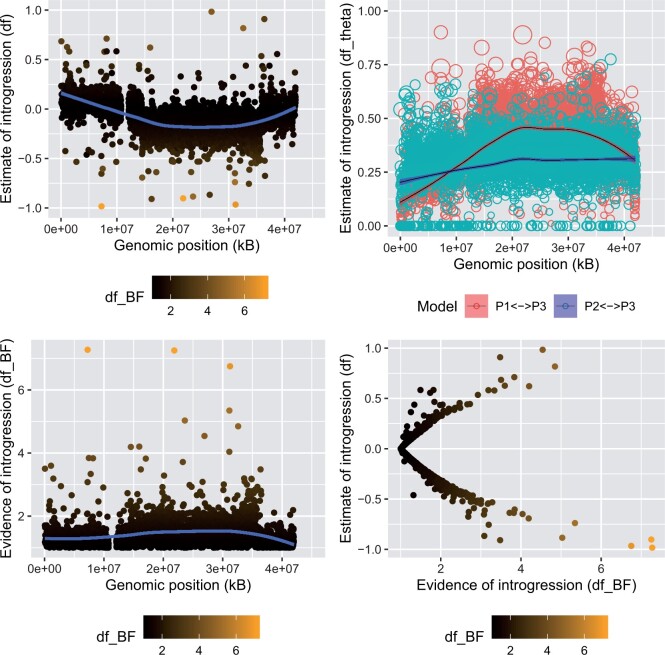

We applied the method to mosquito data analyzed by Fontaine et al. (2015). Their investigation identified introgression between the species Anopheles merus and Anopheles quadriannulatus. Chromoplots for all five chromosomal arms showed a highly spatially heterogeneous distribution of phylogenies, particularly on 3L (Fontaine et al. 2015). The authors studied three possible rooted phylogenetic relationships for An. quadriannulatus (Q), An. melas (L), and An. merus (R), with An. christyi as an outgroup. The region on 3L showed strong evidence of R-Q introgression and a strong negative deviation of the Patterson’s D statistic.

The average population size of the studied groups was 46. Therefore, we set , which provides strong evidence of introgression () when there are approximately 10 fully introgressed SNPs (see Fig. 6).

Next, we scanned the 3L arm with 10-kb consecutive sliding windows and found detects introgression (Fig. 8). The panel in the bottom right plots the Bayes Factors and the statistic values for the same genomic regions. The plot shows that false positives are resolved by . In extreme cases, assigns a maximal fraction of introgression to a region, while the Bayes Factor reports no evidence of introgression. This is because, in these regions, the estimated fraction of introgression is supported by only a few variant sites, or in extreme cases, just a single SNP. There are three genomic regions where moderate evidence of introgression can be reported (). The detected genomic regions differ in their estimated value of the fraction of introgression, the evidence of introgression, and the number of supporting SNPs (see Table 2). For instance, while the window at 7 Mb has the highest value, the evidence of introgression measured by is almost identical to the genomic window at 21 Mb. This is because, the 7 Mb window contains only two SNPs, both with strong signals of introgression, whereas within the genomic region at 21 Mb, there are multiple SNPs. Not all of them contain a strong signal; otherwise, the corresponding value would be much higher (see Fig. 6).

Figure 8.

Application for the 3La chromosome of Anopheles gambiae. The chromosome was scanned using 10-kB consecutive windows. Values for (upper left) vs colored by each alternative specified introgression model where the size of the circle is proportional to (upper right), (lower left), and the latter vs on the lower right. Note, points are colored by (scale on bottom)

Table 2.

Detected regions on the Anopheles gambiae 3La chromosome.

| Mb (start) | Mb (end) | Number of SNPs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7.26 | 7.27 | 2 | −0.98 | 7.27 |

| 21.85 | 21.86 | 10 | −0.90 | 7.25 |

| 31.23 | 31.24 | 3 | −0.97 | 6.75 |

Overall, the signal of the introgressed vector is moderate but consistent over multiple consecutive windows.

5.3 Implementation

The / methodology is fully integrated into the widely used R-package PopGenome (Pfeifer and Kapan 2019) and can scan across genomes using narrow sliding windows, chromosomes, or whole genomes. These methods are found in a dedicated PopGenome module, called introgression.stats(). By integrating the presented methods into PopGenome, researchers can use the full functional spectrum of PopGenome, significantly simplifying data analysis. To reproduce the results shown in Fig. 8, we provide source code on our GitHub repository (https://github.com/pievos101/Introgression-Simulation).

6 Conclusion

We have developed a versatile Bayesian model selection framework that effectively detects and quantifies introgression, exhibiting accuracy equal to or surpassing that of the statistic upon which it is founded. Concurrently, it allows for quantification of the estimated value and the corresponding strength of evidence for introgression through the utilization of Bayes Factors. We have incorporated the new method into the robust genomics R-package PopGenome, which is readily accessible on GitHub (https://github.com/pievos101/PopGenome).

Contributor Information

Bastian Pfeifer, Institute for Medical Informatics, Statistics and Documentation, Medical University Graz, Graz 8010, Austria.

Durrell D Kapan, Department of Entomology and Center for Comparative Genomics, Institute for Biodiversity Science and Sustainability, California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, CA 94118, United States.

Sereina A Herzog, Institute for Medical Informatics, Statistics and Documentation, Medical University Graz, Graz 8010, Austria.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

The presented methods are implemented within the R-package PopGenome (https://github.com/pievos101/PopGenome) and the simulation can be reproduced from the code available on a dedicated GitHub repository (https://github.com/pievos101/Introgression-Simulation). The mosquito data are available on Dryad (https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.f4114).

References

- Abbott R, Albach D, Ansell S. et al. Hybridization and speciation. J Evol Biol 2013;26:229–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adavoudi R, Pilot M.. Consequences of hybridization in mammals: a systematic review. Genes (Basel) 2021;13:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguillon SM, Dodge TO, Preising GA. et al. Introgression. Curr Biol 2022;32:R865–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton NH. The role of hybridization in evolution. Mol Ecol 2001;10:551–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauer CJ, Sandoval-Castillo J, Gates K. et al. Natural hybridization reduces vulnerability to climate change. Nat Clim Chang 2023;13:282–9. [Google Scholar]

- Durand EY, Patterson N, Reich D. et al. Testing for ancient admixture between closely related populations. Mol Biol Evol 2011;28:2239–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edelman NB, Mallet J.. Prevalence and adaptive impact of introgression. Annu Rev Genet 2021;55:265–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaine MC, Pease JB, Steele A. et al. Mosquito genomics. Extensive introgression in a malaria vector species complex revealed by phylogenomics. Science 2015;347:1258524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant PR, Grant BR.. Hybridization increases population variation during adaptive radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019;116:23216–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green RE, Krause J, Briggs AW. et al. A draft sequence of the neandertal genome. Science 2010;328:710–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamlin J, Hibbins M, Moyle L.. Assessing biological factors affecting postspeciation introgression. Evol Lett 2020;4:137–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RG, Larson EL.. Hybridization, introgression, and the nature of species boundaries. J Hered 2014;105Suppl 1:795–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrick PW. Adaptive introgression in animals: examples and comparison to new mutation and standing variation as sources of adaptive variation. Mol Ecol 2013;22:4606–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbins MS, Hahn MW.. Phylogenomic approaches to detecting and characterizing introgression. Genetics 2022;220:iyab173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR. Generating samples under a wright–fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics 2002;18:337–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffreys H. Theory of Probability. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Kronforst MR, Hansen ME, Crawford NG. et al. Hybridization reveals the evolving genomic architecture of speciation. Cell Rep 2013;5:666–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulathinal RJ, Stevison LS, Noor MA.. The genomics of speciation in drosophila: diversity, divergence, and introgression estimated using low-coverage genome sequencing. PLoS Genet 2009;5:e1000550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallet J. Hybridization reveals the evolving genomic architecture of speciation. Trends Ecol Evol 2005;20:229–37.16701374 [Google Scholar]

- Martin SH, Davey JW, Jiggins CD.. Evaluating the use of ABBA-BABA statistics to locate introgressed loci. Mol Biol Evol 2015;32:244–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier JI, Stelkens RB, Joyce DA. et al. The coincidence of ecological opportunity with hybridization explains rapid adaptive radiation in lake Mweru cichlid fishes. Nat Commun 2019;10:5391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson N, Moorjani P, Luo Y. et al. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics 2012;192:1065–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer B, Kapan DD.. Estimates of introgression as a function of pairwise distances. BMC Bioinformatics 2019;20:207–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfennig KS, Kelly AL, Pierce AA.. Hybridization as a facilitator of species range expansion. Proc R Soc B 2016;283:20161329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rambaut A, Grass NC.. Seq-Gen: an application for the Monte Carlo simulation of DNA sequence evolution along phylogenetic trees. Comput Appl Biosci 1997;13:235–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich D, Green RE, Kircher M. et al. Genetic history of an archaic hominin group from denisova cave in Siberia. Nature 2010;468:1053–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seehausen O. Hybridization and adaptive radiation. Trends Ecol Evol 2004;19:198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis PS, Soltis DE.. The role of hybridization in plant speciation. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2009;60:561–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SA, Larson EL.. Insights from genomes into the evolutionary importance and prevalence of hybridization in nature. Nat Ecol Evol 2019;3:170–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todesco M, Pascual MA, Owens GL. et al. Hybridization and extinction. Evol Appl 2016;9:892–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veller C, Edelman NB, Muralidhar P. et al. Recombination and selection against introgressed DNA. Evolution 2023;77:1131–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlock R, Stewart GB, Goodman SJ. et al. A systematic review of phenotypic responses to between-population outbreeding. Environ Evid 2013;2:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney KD, Randell RA, Rieseberg LH.. Adaptive introgression of herbivore resistance traits in the weedy sunflower helianthus annuus. Am Nat 2006;167:794–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The presented methods are implemented within the R-package PopGenome (https://github.com/pievos101/PopGenome) and the simulation can be reproduced from the code available on a dedicated GitHub repository (https://github.com/pievos101/Introgression-Simulation). The mosquito data are available on Dryad (https://datadryad.org/stash/dataset/doi:10.5061/dryad.f4114).