Abstract

Wearable sensors have attracted considerable interest due to their ability to detect a variety of information generated by human physiological activities through physical and chemical means. The performance of wearable sensors is limited by their stability, and endowing wearable sensors with superhydrophobicity is one of the means to enable them to maintain excellent performance in harsh environments. This review emphasizes the imperative progress in flexible superhydrophobic sensors for wearable devices. Besides, the wettability principle and the mechanism of wearable sensors are briefly introduced to propose the combination of superhydrophobicity and wearable sensors. Next, superhydrophobic substrates for wearable sensors, including but not limited to, polydimethylsiloxane, polyurethane, gel, rubber, and fabric, are described in depth, and also the respective fabrication processes and performances. Moreover, the utility of superhydrophobic wearable sensors in a normal intelligent environment is described, highlighting their application in monitoring physiological signals, such as physical movement, pulse, vibration, temperature, perspiration, respiration, and so on. Finally, this review evaluates the challenges and dilemmas that wearable sensors must be overcome for further development and improve the functional performance of wearable sensors, paving the way for their expansion into advanced wearable sensing systems.

Keywords: Superhydrophobicity, Wearable sensor, Fabrication, Application

Introduction

In the era of intelligence, sensors are widely used in our daily lives due to their convenience, safety, and reliability, such as in motion monitoring [1–3], pulse detection [4–6], and sweat detection [7–9], which promotes the further development of sensor technology [10, 11]. It is worth mentioning that limb movement (e.g., muscle contraction during exercise [12]) and biochemical indicators (e.g., glucose [13]) can be used as the two core signal detection objects to monitor the human physiological functions. However, the sensors need relatively low-humidity environment to work properly, and the sweat stains produced by the human body will wet and contaminate the sensor surface. Traditional sensors are mostly rigid, which cannot meet the use of sensors in irregular scenarios such as bending and twisting, which limits their wide application in the field of wearable sensors.

Superhydrophobic wearable sensors have successfully solved these problems. However, higher requirements for the performance of superhydrophobic sensors, such as high sensitivity, linearity, and mechanical stability, are needed, which is an important bottleneck in the manufacturing of superhydrophobic flexible sensors, limiting the application of superhydrophobic wearable sensors. The performances of superhydrophobic flexible sensors can be greatly improved with the use of novel materials. However, it is difficult to develop novel materials, so researchers have been exploring new preparation methods on different substrates. By adding a variety of materials or fabricating microstructures on different substrates, not only can the fabricated sensor obtain excellent electrical conductivity and superhydrophobicity at the same time, but also improve their sensing sensitivity and linearity, which broadens their potential application value in different scenarios.

As a wearable sensor for real-time movement monitoring, it is waterproof, sweat resistant, and still needs to maintain high sensitivity and stability in harsh conditions, such as high humidity environments. The superhydrophobic layer can isolate the contact between the liquid drop and the conductive layer, effectively preventing the liquid drop from penetrating into the conductive layer and affecting the resistance. In some types of flexible strain sensors, such as paper, sponges, and textiles, the flexible substrate is hydrophilic, which can reduce the sensing performance when it comes into contact with water droplets, and the superhydrophobic surface can solve the problem.

In humid environment, due to the high contact angle and small rolling angle of the superhydrophobic surface, the liquid droplets are easy to separate from the surface, and the debris on the surface will be taken away during the droplet rolling process, so that the superhydrophobic surface has the ability to self-clean, and to a certain extent, improve the antibacterial and anti-corrosion performance, so that the superhydrophobic wearable sensor can be used in humid environment, such as long-term stable operation under sweat conditions.

Due to the special wettability of the superhydrophobic surface, it is not easy for the droplet and the material to fit, and the experimental droplet naturally has the rolling property. Therefore, in the application of low temperature environment, the superhydrophobic surface has the role of cold, frost, and ice prevention, and has great application potential in the industrial field. Therefore, the superhydrophobic wearable sensor prepared by using a superhydrophobic material to cover the sensor surface can effectively maintain the performance of the sensor in a wet or sweat environment.

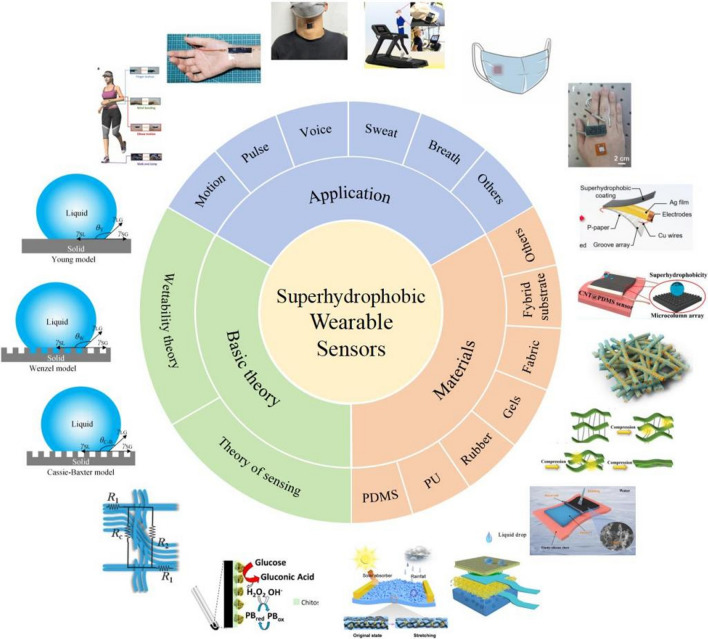

In this review, we highlight the superhydrophobic wearable sensors with different flexible substrates (Fig. 1). The first section briefly introduces three kinds of typical wettability models and four sensing mechanisms about wearable sensors. The second section describes in details the commonly used substrate materials, preparation methods and sensor properties of superhydrophobic flexible sensors. The third section introduces five application scenarios of superhydrophobic flexible sensors on wearable devices, including motion detection, pulse detection, voice detection, sweat detection, and breath detection. Finally, we summarize the development of superhydrophobic flexible sensors and point out the problems that need to be solved to fabricate superhydrophobic flexible sensors [14–16].

Fig. 1.

Overviews of superhydrophobic wearable sensors focusing on substrate materials, preparation and applications. Surface wettability theories: Young model, Wenzel model and Cassie-Baxter model [17–19]. Mechanisms of stress and strain detection: Reproduced with permission [20, 21]. Copyright 2016 WILEY‐VCH. Glucosidase biosensing method on PB electrode: reproduced with permission [13]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. Superhydrophobic flexible strain sensor for solar thermal harvesting functions: reproduced with permission [22]. Copyright 2023 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. A wearable piezoresistive sensor: reproduced with permission [23]. Copyright 2023 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Superhydrophobic strain sensor with high biocompatibility and sensing performance: reproduced with permission [5]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. Hydrophobic PI nanofiber/MXene composite aerogel for wearable piezoresistive sensor: reproduced with permission [24]. Copyright 2021 Wiley‐VCH GmbH. Superhydrophobic conductive fabrics with full human motion detection capabilities: reproduced with permission [2]. Copyright The Royal Society of Chemistry 2023. A superhydrophobic wearable strain sensor with anti-/deicing properties: reproduced with permission [25]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society. Bionic paper-based superhydrophobic wearable strain sensor. Reproduced with permission [26]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society. Wearable superhydrophobic PPy/MXene pressure sensor based on cotton fabric with superior sensitivity for human detection and information transmission. Reproduced with permission [3]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Mechanically durable superhydrophobic strain sensors with high biocompatibility and sensing performance for underwater motion monitoring. Reproduced with permission [5]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society. Superhydrophobic conductive suede fabrics based on carboxylated multiwalled carbon nanotubes and polydopamine for wearable pressure sensors. Reproduced with permission [27]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. Superhydrophobic functionalized Ti3C2Tx MXene-based skin attachable and wearable electrochemical pH sensor for real-time sweat detection reproduced with permission [9]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. A robust bridge-type airflow sensor based on flexible superhydrophobic carbon nanotube fiber thin films. Reproduced with permission [28]. Copyright 2023 The Authors. Advanced materials interfaces published by Wiley–VCH GmbH. Superhydrophobic surfaces-based redox-induced electricity from water droplets for self-powered wearable electronics [29]. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved

Basic theory

Classical wettability theory

Many plants and animals in nature exhibit unique water repellency, such as, lotus leaf, butterfly wing, and duck feather, where water droplet appear as sphere on their surfaces (Fig. 2a). Inspired by this phenomenon, researchers have proposed a number of functional surfaces based on superhydrophobicity that can be used for fluid transportation [30–32], water harvesting [33–35], power generation [36–38], anti-fouling [39–41], anti-icing [42–44], oil–water separation [45–47], and other function [48–50]. Researchers refer to the ability of a water droplet to spread on a solid surface as the wettability of the surface that composed of the surface’s microstructure and chemical composition, which is usually expressed as contact angle (CA) [51, 52]. At the solid–liquid-gas-phase intersection, the tangent lines of the gas–liquid interface and the solid–liquid interface are made, and the angle between the two tangent lines is CA (Fig. 2b). The solid surface is hydrophilic when the contact angle is less than 90°, hydrophobic when the contact angle is between 90° and 150°, superhydrophilic when the contact angle is less than 10°, and superhydrophobic when the contact angle is more than 150° (Fig. 2c) [53, 54]. Surface wettability theories are usually Young model, Wenzel model, and Cassie-Baxter model.

Fig. 2.

Classical theory of wettability. a Lotus leaf, duck feather, and butterfly wing. b Schematic of contact angle. c Schematic of a water droplet on superhydrophilic surface, hydrophilic surface, hydrophobic surface, and superhydrophobic surface. d Young model. e Wenzel model. f Cassie-Baxter model

Young model

In the Young [17] model, the contact angle of a liquid on an ideally smooth solid surface is only related to the surface tension at the interface of the solid–liquid–gas phases (Fig. 2d), which is also called the intrinsic contact angle, denoted as θY, which satisfies the Young’s equation:

| 1 |

where γSG, γSL, and γLG are the surface tension at the solid–vapor phase interface, the surface tension at the solid–liquid phase interface and the surface tension at the gas–liquid phase interface, respectively. In Eq. (1), the magnitude of the intrinsic contact angle θY is inversely proportional to (γSG-γSL) if γLG is a certain value.

Wenzel model

Wenzel [18] stated that the surface of a real object generally had the roughness rather than a smooth surface in the ideal state (Fig. 2e). The contact angle equation in the Wenzel model is:

| 2 |

| 3 |

where θW denotes the contact angle in Wenzel’s model, r denotes the roughness factor of the object’s surface, Sreal denotes the actual area of contact between the liquid and the solid surface, and Sappear denotes the area circled by the solid–liquid–gas three-phase contact line on a solid surface, known as the apparent area, which is in fact Sreal > Sappear, due to the presence of a microstructure on the solid surface, so r > 1. From Eq. (2), it can be seen that at θW < 90°, Sreal will increase with the roughness of the solid surface, which will make the hydrophilic surface more hydrophilic. Correspondingly, at θY > 90°, the hydrophobic surface will be more hydrophobic.

Cassie-Baxter model

Cassie-Baxter [19] stated that although the solid surface has a microscopic rough morphology, the liquid in contact with the surface was not completely filled with the microstructure of the solid surface (Fig. 2f). In the Cassie-Baxter model, when the liquid is in contact with the solid surface, the liquid surface is separated from the solid surface by the air inside the solid surface microstructure, and there are both gas–liquid and solid–gas contact composite contact surfaces at the liquid–solid contact surface. The contact angle equation of the Cassie-Baxter model is:

| 4 |

where θC-B denotes the contact angle in the Cassie-Baxter model; f1 denotes the proportion of the solid–liquid interface on the composite contact surface, and f2 denotes the proportion of the gas–liquid interface on the composite contact surface. From Eq. (4), θC-B is inversely proportional to f1 at the hydrophobic surface θY > 90°. Therefore, in the Cassie-Baxter model, the contact angle θC-B can increase with the increase of the microscopic rough structure of the solid surface (decreasing the solid–liquid contact area).

The contact angle is an important measure used to describe the wettability of the surface. According to the contact angle, the superhydrophobic property of the prepared surface can be judged. In addition, it can be used as an index to judge the superhydrophobic property of the surface in corrosion resistance, impact resistance, and other performance testing experiments. Young’s equation describes the contact angle between the droplet and an ideal solid surface which is smooth, homogeneous, undeformed, and isotropic. The Wenzel model is used to describe the contact angle of a droplet when the surface rough structure is completely wetted by a droplet, based on the wet contact assumption that the droplet can completely fill and infiltrate the microscopic grooves on the rough surface. The Wenzel model is used to describe the contact state between a droplet with an air cushion and a rough surface, and there is air between the droplet and the surface. From a thermodynamic point of view, the droplet will tend to the smaller contact angle mode to reduce its energy, and the droplet will choose the mode that makes its energy lower. In practical applications, this will cause the droplet to change between the Wenzel model and the Cassie model. When applied to the wearable superhydrophobic surface, the droplet in Cassie state is ideal, because the contact area between the droplet and the surface is small, the solid–liquid adhesion is small, and the droplet is easy to detach from the surface, achieving the ability of surface self-cleaning. However, under certain intrinsic contact angle conditions, the droplet in Cassie state is not in the lowest energy state, so it is relatively unstable and will transform into Wenzel state.

Sensing principles of wearable sensor

A device that can convert the measured into the same or another quantity output in a certain way is called a sensor. Sensors applied to wearable devices are mainly physical sensors and chemical sensors depending on the type of biological signals detected. The sensing mechanisms used based on these two signals are strain sensing and electrochemical sensing. Physical sensors are used to detect limb movement, pulse, and other physical signals. Chemical sensors can detect or quantify specific chemicals, such as glucose.

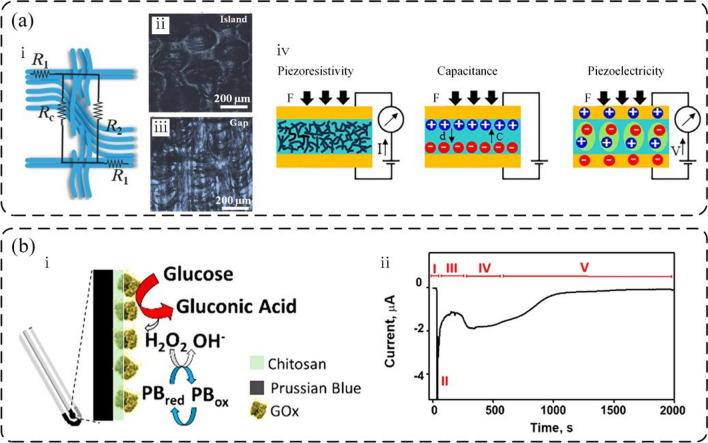

Pressure or tensile detect

Pressure or stretch sensors (Fig. 3a) are indispensable components on wearable devices, which are mainly used in the detection of limb movement, pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and other vital signs detection, which have a greater application value in the field of sports and healthcare. Sensors capable of detecting pressure or stretch apply a wider variety of mechanisms, but there are three main categories of flexible sensor used in wearable devices: capacitive sensor, resistive sensor, and piezoelectric sensor [20, 21]. Capacitive sensors are generally two conductive layers and a dielectric layer to form a sandwich structure, and the conductive layer of flexible capacitive sensors is usually made of conductive polymer, and the dielectric layer is generally an elastic material with a high dielectric constant.

| 5 |

where C represents the capacitance, ε is the dielectric constant, A is the overlap area of the conductive layer, and d is the distance between the conductive layer. When the sensor is subjected to external forces, it will be deformed, which will change the distance between the conductive layers or two conductive layers or the overlap area of the two conductive layers, resulting in changes in capacitance. Then, the variables of pressure change or tensile deformation can be obtained by measuring or analyzing the sensor capacitance.

Fig. 3.

Mechanism of wearable sensor. a Mechanism of stress and strain detection. (i): Schematic illustration showing the resistance model of an elementary unit. Optical image of (ii) the island and (iii) gap formed under tensile strain. (iv): Flexible and stretchable pressure sensor. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2016 WILEY‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim [20, 21]. b Mechanism of detection of biochemical signals. (i): Schematic of the glucose enzymatic biosensing approach on the PB electrode. (ii): On-body saliva monitoring for a healthy individual. Signal interpretation: a dry device. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society [13]

Resistive sensor mainly utilizes the change in resistance after the sensor is deformed or stretched by an external force to detect pressure and stretch. Resistive sensor in wearable device is usually made of conductive material embedded in flexible materials, such as carbon nanotube embedded in elastic material, when the substrate is deformed by force, the carbon nanotubes on the substrate will change the distance between the carbon nanotubes, which will have an impact on the charge transfer, which affects the size of the resistance.

Piezoelectric sensor mainly relies on the piezoelectric effect of piezoelectric material; the piezoelectric effect is when the piezoelectric material is subjected to external force to produce deformation of the surface of a phenomenon that generates a voltage. Piezoelectric material integrated in wearable device can generate an electrical signal under external force and deformation, so that the magnitude of the measured pressure or deformation can be derived through analysis and calibration.

For example, a strain gauge sensor can take advantage of the strain effect of a material, and when the human body moves, the strain gauge on the sensor will be stretched or compressed, resulting in a change in the resistance value of the material. By measuring this resistance change, the intensity and direction of human movement can be indirectly reflected. A piezoelectric pressure sensor is based on the piezoelectric effect, in the human movement monitoring, the sensor can be placed in the need to monitor the part, when the human movement, the sensor is under pressure, generate electrical signal output. When the self-driven sensor is subjected to external forces, it will change the electrical properties of the internal structure of the sensor, such as resistance, capacitance, or piezoelectric effects, resulting in an electrical signal output. These sensors can be applied to superhydrophobic wearable devices to monitor human movement signals, such as limb bending and muscle stretching, to monitor the movement of the human body during movement.

Biochemical signal detect

The life activities of the human body are not only limited to macroscopic limb movement and pulse. There are also a variety of biochemical reactions, such as glucose oxidation to release energy, protein synthesis, and decomposition, which are also life activities for the normal functioning of the human body. A considerable portion of the human body’s state of the data can be obtained through the content of certain salts and proteins, such as glucose content to detect blood glucose, which is a very important data in the diabetes daily treatment. This is a very important data in the daily treatment of diabetes.

Biosensor usually have high specificity, which mean that the sensor only acts on the target substance, the more commonly used are enzymes, antibodies, and receptors, in which enzyme is the most commonly used one, and the principle of detecting biochemical signals is briefly explained here with one of the more common biosensors. The glucose sensor is used for the detection of human blood glucose (Fig. 3b) [13]. Firstly, the glucose in the measured sample is decomposed into gluconic acid and hydrogen peroxide by the glucose oxygenase (GOx) immobilized on the surface of the sensor and hydrogen peroxide generates hydroxide ions (OH−) by the catalyst, which generates micro-currents, by detecting and analyzing the micro-currents. The concentration of glucose in the sample can be obtained by detecting and analyzing the strength of the micro-current.

The enzyme sensor initially uses oxygen as a relay for electrocatalysis, which is achieved by measuring the reduction of reactant O2 or the production of reaction product H2O2. The second-generation enzyme sensor uses electron transfer mediator to measure glucose with the oxidation current generated by the transfer mediator with low oxidation potential on the electrode, thus avoiding the interference of other electroactive substances. Compared with the first-generation enzyme sensor, the sensitivity and accuracy of the second-generation enzyme sensor have been improved to a certain extent. However, in the process of developing and manufacturing enzyme sensors, there are still problems about how to screen high-active enzymes suitable for sensors and how to extend the service life of enzyme sensors. This section describes the principle of superhydrophobicity and the principle of wearable sensor. The wearable sensor for the detection of human physiological information can be applied to practical application, but wearable sensor in the work of its surface is contaminated by the sweat or other contamination, resulting in that its performance will be degraded or even fail. However, if the superhydrophobic property can be attributed to the wearable sensor, it will further increase the feasibility of wearable sensor application.

Fabrication of superhydrophobic wearable sensor on different substrates

Superhydrophobic wearable sensor fabricated on the different flexible materials not only shows excellent performance in terms of flexibility, comfort, and functionality, but also maintains stable performance under the extreme environments. Low modulus, high toughness, and high ductility are usually used as criteria for selecting substrate material. The combination of nanostructures and low surface energy modification to form a superhydrophobic layer significantly improves the hydrophobicity of the sensor’s functional surface as well as the sensor’s sensitivity and durability, which provides a reliable guarantee for various application scenarios. A comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of several common substrate materials is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of substrate materials

Polydimethylsiloxane substrate

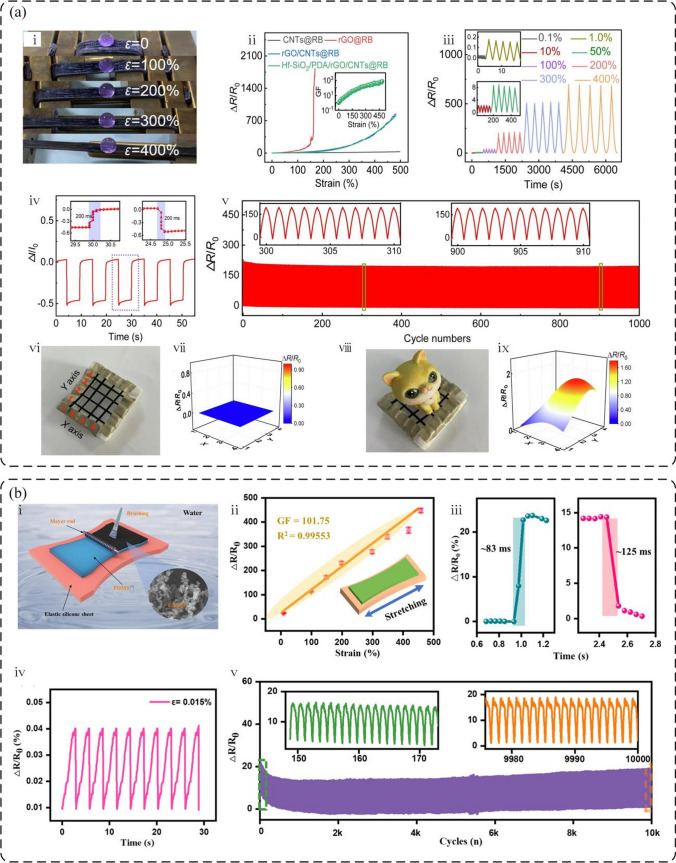

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) has the advantages of variable modulus and thickness, simple preparation process, and stable chemical properties, so it is often used as a substrate for flexible sensor [65]. In 2019, Wang et al. [66] fabricated a strain sensor using fluorinated PDMS as a substrate and cured superhydrophobic carbon nanotubes (CNTs) powder on the surface, which had excellent sensitivity and maintains hydrophobicity after various damages (e.g., up to 200% strain, sandpaper sanding, chemical attack, and high-speed dropping).

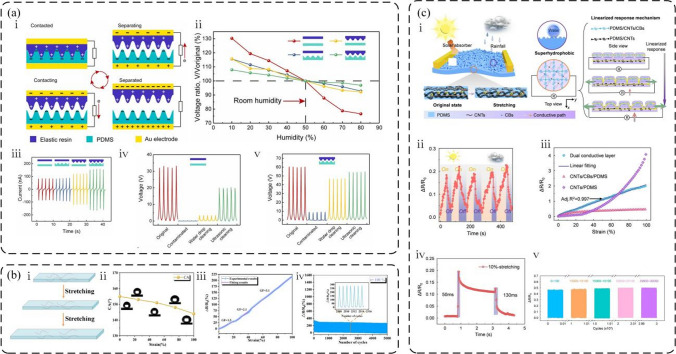

Li et al. [67] invented a biologically-driven sweat-resistant wearable friction generator (BSRW-TENG) (Fig. 4a) in 2021 for motion detection in sports and fitness devices, which consisted of two superhydrophobic friction electric layers (elastomeric resin and PDMS) (Fig. 4a-i), which utilized micro/nanostructures on the friction electric surfaces for enhancing the electricity and had excellent sweat resistance. Due to the better elasticity of the resin and PDMS, the sensor also had better long-term stability (no significant change in output in 10,000 cycles).

Fig. 4.

Fabrication of superhydrophobic wearable sensors on PDMS. a A biologically driven sweat-resistant wearable friction generator. (i): Working principle of the BSRW-TENG. (ii–v): Sensing performance of BSRW-TENG. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2022 The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd [67]. b A superhydrophobic wearable strain sensor. (i): Schematic diagram of the resistance change mechanism with tension strain. (ii): Variations in the water contact angle under different strains. (iii–iv): Sensing performance of tensile strain sensors. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2021 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved [55]. c Superhydrophobic flexible strain sensors for solar thermal harvesting functions. (i): Design ideas and strain sensing mechanisms of bionic flexible sensors. (ii): Changes in resistance of bionic sensors under light and dark conditions. (iii–v): Biomimetic sensor strain sensing performance. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved [22]

Liu et al. [55] homogeneously dispersed CNTs in a PDMS substrate, and then fabricated a superhydrophobic wearable strain sensor by CO2 laser engraving (Fig. 4b-i), which possessed excellent corrosion resistance, good sensitivity (the measurement factor is 3.1), and a wide sensing range.

In addition, this sensor also had excellent durability, which means that this sensor had potential applications in the wearable field. Inspired by moth wings, Li et al. [22] fabricated a flexible strain sensor with superhydrophobicity and solar thermal harvesting by spraying conductive ink on a PDMS substrate in 2022 (Fig. 4c), which had a fast photothermal response (0.403 °C/s), good linearity (0.992), short response time (50 ms), good stability (with over 30,000 cycles of durability), and low detection limit (0.7%).

Shang et al. [56] developed a simple and inexpensive method to fabricate superhydrophobic flexible sensor by spraying a PDMS substrate with an elastomer dispersed in a solution with carbon black (CB) nanoparticles. The fabricated sensor not only had a good self-cleaning property, but also had a good sensitivity (measurement factor GF of 5.4–7.35), a wide sensing range (stretching over 70%), and low hysteresis.

Based on biomimetic nanostructures, Yao et al. [57] fabricated a flexible strain sensor by spraying a thermoplastic elastomer solution dispersed with multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) onto a PDMS substrate with cracks, and then sucking out the conductive film of the raised structure with a magnet. This fabricated sensor has good hydrophobicity, high sensitivity (specification factor GF = 33.08, 0 < ε < 60%), very low detection limit (ε < 0.1%), fast response time (62 ms), and long stabilization period, in addition the sensor can detect sound at 3000 Hz, showing the ability to accurately identify volume and silver color.

Inspired by the superhydrophobic surface of lotus leaf, Hu et al. [68] fabricated a superhydrophobic flexible antimicrobial strain sensor (CGP) based on PDMS. This sensor had advantages of excellent sensitivity (measurement factor GF = 0.467, 0 < ε < 15%) and fast response (65.4 ms, ε = 5%). In addition, this sensor was effective at extreme temperatures (high conductivity of 1.2 mS/cm at − 20 °C, 2.0 mS/cm at 100 °C). Moreover, the surface of this sensor had an antibacterial rate of more than 99% against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus.

In 2024, Jin et al. [69] used chemical vapor deposition to grow nano-cone arrays on a PDMS substrate to fabricate a microfluidic sweat sensing patch for efficient sweat transport, collection, and sensitive analysis, superhydrophilic micro-channels provided great capillary forces for rapid sweat transport, while superhydrophobic surface confined the sweat to the channels and reduced its flow friction. The patch can achieve sweat flow rates of up to 46 mm/s, which exhibited selectivity and sensitivity to specific substances after the construction of a highly porous hydrogel nanocomposite permeated with the relevant enzyme solution on the working electrode of the patch. The above mentioned PDMS-based sensors have better durability under small strain cycles. However, the durability at large strain cycles still needs to be improved for more usage scenarios.

Polyurethane substrate

Electrostatically spun fiber membranes with breathability, stretchability, and their own microstructures have been widely studied as new substrates. A significant portion of polyurethane (PU)-based superhydrophobic sensor is fabricated by adding coatings to electrostatically spun PU fiber mats [70–72]. Among them, in 2019, Gao et al. [73] decorated acid-treated carbon nanotubes (ACNTs) on the surface of PU nanofibers to fabricate conductive superhydrophobic nanofiber membranes made a multifunctional sensor that can detect both chemical vapors and tensile strains, which had good selectivity, high sensitivity, and low detection limit (1 ppm for toluene vapors), which had potential applications in smart textile and other fields.

Gao et al. [74] wrapped graphene around electrostatically spun PU fibers with the assistance of ultrasound, and then modified the graphene shell with SiO2 nanoparticles to produce a superhydrophobic conductive nanocomposites (SCNCs) that can be used as strain sensors. SCNCs had a high tensile properties and reliability, which can be used to detect the full range of human body movements.

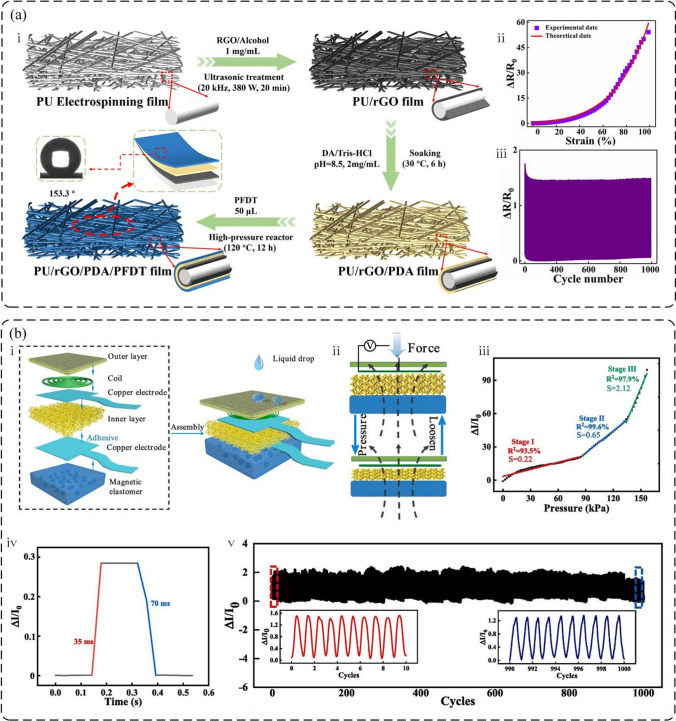

In 2022 Gao et al. [58] fabricated a high-performance strain sensor based on PU by electrostatic spinning (Fig. 5a), whose shell was modified by high temperature and high pressure deposition of low surface energy 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorodecane-thiol, which had a high operating range of up to 590% and ultra-high stable sensing performance within 10,000 cycles, which had high potential within the field of flexible wearable electronics. Subsequently, in 2023, Gao et al. [75] fabricated a superhydrophobic self-healing sensor by embedding reduced graphene oxide (rGO) in fibers with electrostatic spinning self-healing PU fiber membranes as the substrate, which could achieve 85.6% self-healing of scratches at 50 °C and had good cycling stability.

Fig. 5.

Fabrication of superhydrophobic wearable sensors on polyurethane. a A superhydrophobic strain sensor with multilayer structure. (i): Fabrication of superhydrophobic strain sensor with multilayer structure. (ii–iii): Strain sensor performance. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society [58]. b A wearable piezoresistive sensor. (i): Schematic representation of the extension and assembly of the prototype superhydrophobic-magneto-electric sensing integrated SWPS. (ii): Schematic diagram of the conductive coil and magnetic elastomer in SWPS. (iii–v): Sensing performance of SWPS. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved [23]

Meng et al. [76] first added a conductive layer of CNTs to an electrostatically spun TPU fiber mat modified by polydopamine (PDA), after which polyhedral oligosiloxanes (POSS) and 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorooctyltrimethoxysilane were coated onto a thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) mat to form a hydrophobic layer to make nano composite fiber mat. The fiber mat can be used as a superhydrophobic strain sensor, which not only exhibits excellent tensile properties at 550% strain, but also outputs stable signals during small deformation actions, such as swallowing and occurrence.

In the same year, Song et al. [23] fabricated an inner layer of a stable wear-resistant piezoresistive sensor with a sandwich-like layer structure based on PU, which consisted of a flexible superhydrophobic conductive inner layer, a rigid superhydrophobic outer layer, and an electromagnetically-induced generator bottom layer (Fig. 5b), in which the outer layer was able to ensure stable self-powering. The sensor can be used in various scenarios, especially in extreme conditions, as it can therefore maintain a long service life in humid, acidic, and alkaline environments without external power supply.

In 2023, Chen et al. [77] used TPU as the substrate, chemically modified rGO as the conductive raw material to do the middle layer of conductive filler, and then sprayed a layer of flexible graphene-based composite on the surface to give the sensor superhydrophobic properties to fabricate a sandwich structure strain sensor (SFGCM). In extreme environments, the ability of the sensor to continuously capture signals was almost unchanged. In addition, the SFGCM was able to withstand considerable mechanical deformations, which can be used for the detection of various behaviors of the human body. In short, PU-based superhydrophobic wearable sensors combine flexibility, comfort, and durability, but still face certain challenges in terms of conductivity and long-term stability of superhydrophobic coatings.

Rubber substrate

Rubber, with its good elasticity, chemical stability, and low price, is more suitable as a substrate material for flexible sensor. In 2018, Gao et al. [1] fabricated a superhydrophobic conductive layer with a layered fluorinated carbon nanotube (FCNT)/silica nanoparticle structure on an elastic band using a spraying method. The strain sensor based on this superhydrophobic coating possessed excellent stability and durability under the application of external forces such as repeated tensile and abrasion, and had an extremely low strain detection limit (0.01% strain), great strain sensing range (480% strain), and ultra-high sensitivity (the measurement factor can reach 1766), which can realize large and subtle movements of the human body under harsh frontal conditions.

In 2019, Wang et al. [78] modified silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on the surface of rubber bands, and then modified RB/AgNPs using PDMS to fabricate a superhydrophobic and highly conductive rubber composite material that can be used as a strain sensor, which had good tensile property (elongation at break > 900%), good tensile property (elongation at break > 900%), and high sensitivity (corresponding strength up to 3.6 × 108 at 60% strain), which allowed the material to be used in water and ice removal applications.

In 2022, Li et al. [79] fabricated a superhydrophobic super-stretchable wearable strain sensor, which was based on elastic bands (EBs) with nanocarbon blacks (CBs) and CNTs as conductive fillers, and modified by the PDMS. This wearable strain sensor still had good stability and sensitivity after 3000 cycles (100% strain).

Sun et al. [80] first constructed a CNTs/rGO bilayer conductive structure on a rubber band (RB) substrate, and then immobilized a graphene oxide (GO) layer with superhydrophobic-phase silica using a self-adhesive polydopamine (PDA) to fabricate an RB-based superhydrophobic strain sensor (Fig. 6a), which had a low detection limit (as low as 0.1% strain), a wide operating range (0–482% strain), a high sensitivity (measurement factor GF of 685.3 at 482% strain), and an excellent long-term stability (more than 1000 cycles), which can be used not only for the human movement in aqueous environments, but also for the spatial pressure in tactile e-textiles (Fig. 6a-vii–xii).

Fig. 6.

Fabrication of superhydrophobic wearable sensors on rubber. a Superhydrophobic conductive rubber tape with synergistic dual conductive layers. (i): Optical images of water droplet on the surface of superhydrophobic conductive RB under different strains. (ii–v): Strain sensing performances of superhydrophobic conductive RB based strain sensor. (vi–ix): Digital photographs of an e-fabric assembled from superhydrophobic conductive RBs with 4 × 4 pixels as well as the change in resistance of the doll on the e-fabric and the corresponding pressure distribution. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2022 Science China Press. Published by Elsevier B.V. and Science China Press. All rights reserved [80]. b Superhydrophobic strain sensors with high biocompatibility and sensing performance. (i): Schematic structure of superhydrophobic SS/PDMS-CBNP strain sensor. (ii–v): Sensing properties of superhydrophobic SS/PDMS-CBNP strain sensor. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society [5]

In 2023, Luo et al. [81] fabricated superhydrophobic pressure and temperature sensor by ultrasound-assisted interfacial sintering to immobilize CNTs and stearic acid (STA) mounts on a styrene-butadiene rubber (SBR) foam skeleton. The fabricated sensor had good corrosion resistance and durability (up to 11,000 cycles), and can work normally under corrosive conditions. In addition, the resistance of the sensor can suppress the negative temperature coefficient, which made it possible to be used as a temperature sensor.

In addition, Liu et al. [82] fabricated MWCNTs/LIG crosslinked conductive networks on stretchable silicone rubber (SR) substrates by laser irradiation, and subsequently covered the MWCNTs/LIG crosslinked conductive networks with another layer of SR to form a sandwich structure, and finally irradiated the composites using a laser engraver. The composite material formed a micro-nanoconvex structure on its surface to make a superhydrophobic composite strain sensor, the fabricated sensor has up to 667 GF as well as 230% of the operating range, excellent corrosion resistance (pH = 1–14), and ice resistance (36 min, − 5 °C). This sensor can do the human body movement monitoring under the corrosive agent low-temperature environment.

In 2023, Yao et al. [5] also fabricated a wearable flexible strain sensor with SR as the substrate (Fig. 6b-i). they directly coated the conductive CB particles (CBNPs) directly on the PDMS coating bonded with SR, and the fabricated sensor had a high sensitivity (measurement factor of 101.75), strong tensile (0.015–460%), and low latency (response time 83 ms), and can be cycled stably for a long period of time (up to 10,000 times), due to its excellent superhydrophobicity and sensing properties that enabled the sensor to monitor the real-time situation of a person in real-time while swimming.

Gel substrate

Gel materials, such as aerogels exhibit ultra-low density and compressibility due to their stabilized honeycomb structure, can be used to fabricate the wearable sensor. In 2019, Zhou et al. [59] fabricated self-healing wearable strain sensor based on poly (AA-co-SMA)/c-CNF/Fe3+ nanocomposite hydrogels (AA: acrylic acid, SMA: stearoylmethacrylate, c-CNF: carboxylate-modified cellulose nanofibers). The nano-composite hydrogel achieved complete supramolecular cross-linking through hydrophobic conjugation and ion interaction, which realized the self-healing function of the sensor. In addition, c-CNF, as a rigid component, improved the mechanical strength of the sensor and reduced the strain of gel. This sensor had a large sensing range (0–800%), high sensitivity (strain 0–300%, GF = 1.9; strain range 400–800%), and high durability (up to 1000 cycles), resulting in ensuring its application in human detection.

In 2021, inspired by spider webs, Liu et al. [24] fabricated conductive polyimide (PI) nanofibers/Mxene composite aerogels that could be used in piezoresistive sensors by freeze-drying and thermoimidization processes (Fig. 7a). The fabricated sensor had stable electrical properties with very low density and could remain stable elastic property at − 50–250 °C, which was suitable for human motion detection.

Fig. 7.

Fabrication of superhydrophobic wearable sensors on gel. a Hydrophobic PI nanofiber/MXene composite aerogel for wearable piezoresistive sensors. (i): Schematic diagram of the piezoresistive sensing mechanism of PINF/MXene composite aerogel. (ii–vii): Piezoresistive sensing performances of PINF/MXene composite aerogel. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2021 Wiley‐VCH GmbH [24]. b Wearable strain sensors based on superhydrophobic conductive hydrogels. (i): The SEM image of the superhydrophobic surface. (ii): The SEM image of internal porous structures of the dehydrated hydrogel. (iii–v): Antibiotic activity of the broth composite hydrogel. (vi–viii): Sensing performance of superhydrophobic conductive hydrogel strain sensors. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society [60]

Wang et al. [60] fabricated a wearable strain sensor with a bilayer structure based on a conductive composite hydrogel (Fig. 7b), which had an outer layer of a silicone elastomer composite membrane with silica particles, and an inner layer of P(AAmco-HEMA)-MXene-AgNPs hydrogel, in which the outer layer of Ecoflex/SiO2 microparticle composite membrane provided stable superhydrophobicity. In addition, to the fast response speed (120 ms) and stability (no performance degradation was observed after 600 cycles), the inner layer of the sensor could significantly inhibit the activity of Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. When used in the human body, this sensor could help to improve stability under liquid interference and reduce the growth of bacteria on the human epidermis.

Wang et al. [61] fabricated a mechanically robust, liquid puncture-resistant, and self-healing strain sensor by embedding hydrophobic graphene and CNTs into a hydrogel substrate. The sensor can accurately detect human motion and remain superhydrophobic under multiple damages (e.g., 1000% stretching, 10,000 stretching cycles, etc.).

Similarly in 2023, Chen et al. [83] fabricated a superhydrophobic flame-retardant pressure sensor for detecting human body motion. Firstly, they fabricated CS/ammonium polyphosphate/MMT gas-retardant gel with porous by freeze-drying method, and then silver nanowires were coated on the surface of the aerogel by dip-drying method. Finally, the silica/PDMS mixture was sprayed on the surface to complete the preparation. The fabricated sensor had faster response (response/recovery time of 78/100 ms), better stability (the contact angle of the water droplet is still higher than 150° after 1500 cycles), and better flame retardancy (self-extinguishing time of 1.3 s), which had a greater potential for application in the field of e-skin and wearable devices. The performance of various sensors using Gel as the base material performed better, but the degradation of hydrogel performance in the loss of water is a problem that needs to be solved.

Fabric substrate

Fabric can not only be used to make clothes because it has a soft, light weight, good flexibility, low price, and other characteristics, but it can also be used to make wearable sensor.

In 2020, Ipekci et al. [7] showed a flexible electrochemical sensor preparation method by depositing conductive silver patterns on fabrics. They made sensing electrodes by inkjet printing of particle-free silver ink on textiles coated with polyester-like materials, and the fabricated sensors were able to remain stable under repeated bending.

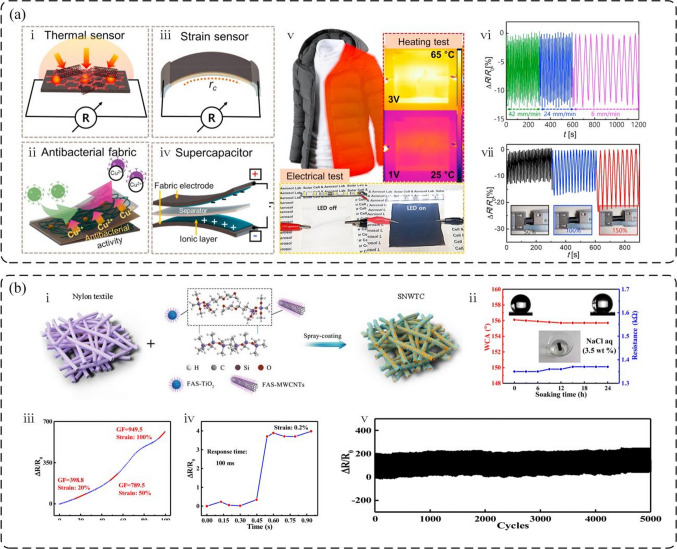

In 2021, Pei et al. [62] fabricated silver nitrate (AgNO3·6H2O)@STA composite coatings on flexible fabrics using a simple dip-coating method based on the flexibility of the fabrics and the superhydrophobicity and conductivity of the coatings allowed the fabrics to be used as strain sensor with high sensitivity (Fig. 8a).

Fig. 8.

Fabrication of superhydrophobic wearable sensors on fabric. a A superhydrophobic metallic fabric. Illustrations of the applications of the multifunctional Cu/CNT/rGO Fabric: (i): thermal sensor. (ii): antibacterial fabric. (iii): strain sensor. (iv): supercapacitor. (v): High conductivity of the sample. (vi–vii): Performance of Cu/CNT/rGO fabrics under different stretching conditions. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2021 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved [84]. b Superhydrophobic conductive fabrics with full human motion detection capabilities. (i): Schematic diagram of preparing the SNWTC by spraying nylon textile with a conductive suspension. (ii): Effect of immersion time in aqueous NaCl solution on WCA and resistance of SNWTC surface. (iii–v): Sensing performance of the SNWTC sensor toward stretching. Reproduced with permission. Copyright The Royal Society of Chemistry 2023 [2]

Park et al. [84] supersonically sprayed rGO, CNTs, and copper nanoparticles onto a fabric to make a wearable energy storage fabric with sensing capability (Fig. 8a). In addition, the fabric was not only antimicrobial, but also capable of generating heat when a voltage was applied or sensing the ambient temperature, and had a good stability in sensing the strain with good stability.

In 2022, Wang et al. [12] made a superhydrophobic strain sensor by using chemical vapor deposition of a composite material (PEDOT) on a fabric, and the fabricated sensor had good flexibility, sensitivity (bending response of 0.4 s), and wide sensing range (bending response range of 15–180°), and the fabric could be used in the harsh environment as well as it had better stability when sensing strain.

In 2023, Peng et al. [63] made a superhydrophobic smart fabric by coating conductive MXene on nylon fabric modified with PDA and then spraying hydrophobic materials (SiO2 and FOTS). The superhydrophobic layer endowed the fabric with superhydrophobicity and was able to protect the conductive layer. The highly conductive MXene coating endowed the fabric with variable highly conductive MXene coating gave the fabric variable conductivity. The fabric not only had better performance indicators of conventional sensors, such as low detection limit (0.2% strain), fast response speed (60 ms), and sensing stability (up to 5000 cycles), but also had an excellent electromagnetic shielding effect (66.5 dB), photo-thermal performance (100mW/cm2), and electro-thermal conversion ability (up to 102.3 °C at 8 V). Therefore, the smart fabric was very effective in electromagnetic shielding (66.5 dB), photo-thermal performance (100 mW/cm2), and electro-thermal conversion ability (102.3 °C at 8 V).

Ma et al. [2] fabricated a superhydrophobic nano-coated textile composite material that could be used as a strain sensor by spraying a conductive suspension (FAS-MWCNTs/TiO2@PDMS) onto the fabric surface (Fig. 8b), and the fabricated fabric can achieve a wide strain range (100% strain), good sensitivity (measurement factor of 949.5), ultra-low detection limit (as low as 0.2% strain), and fast response time (response time of 100 ms), which was expected to be used for underwater motion detection.

Sun et al. [27] constructed a pressure sensor based on a suede textile. They first dip-coated the suede textile with PDA and carboxylated MWCNTs, and then modified the surface with cetylmethoxysilane, from making the fabric a pressure sensor with good hydrophobicity, stability, and repeatability, which can be used for the detection of daily human motion.

Hybrid substrates

When fabricating wearable sensor, people usually use a single substrate to fabricate coating, which is a cumbersome process, and directly by mixing different materials as the substrate can save some steps to improve productivity or better performance. [64, 85]

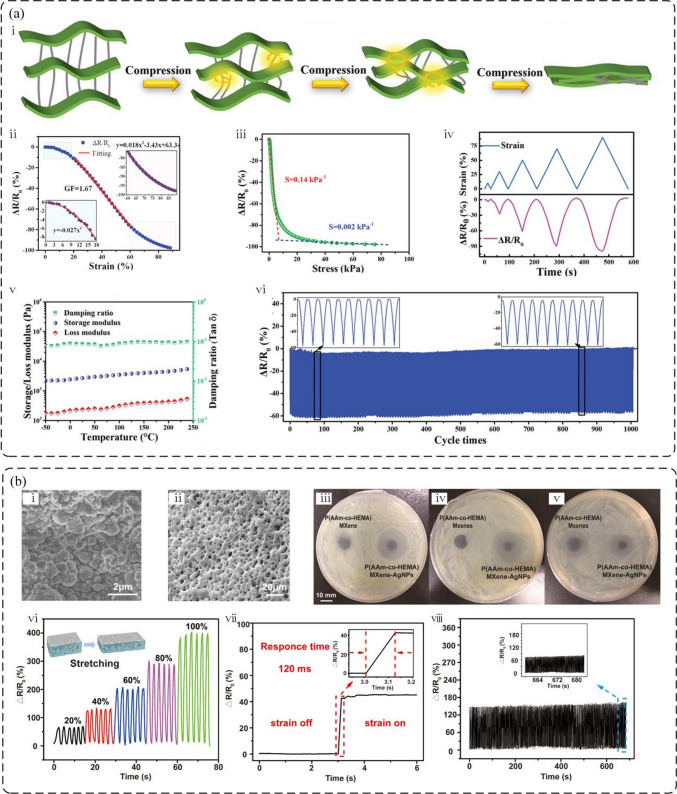

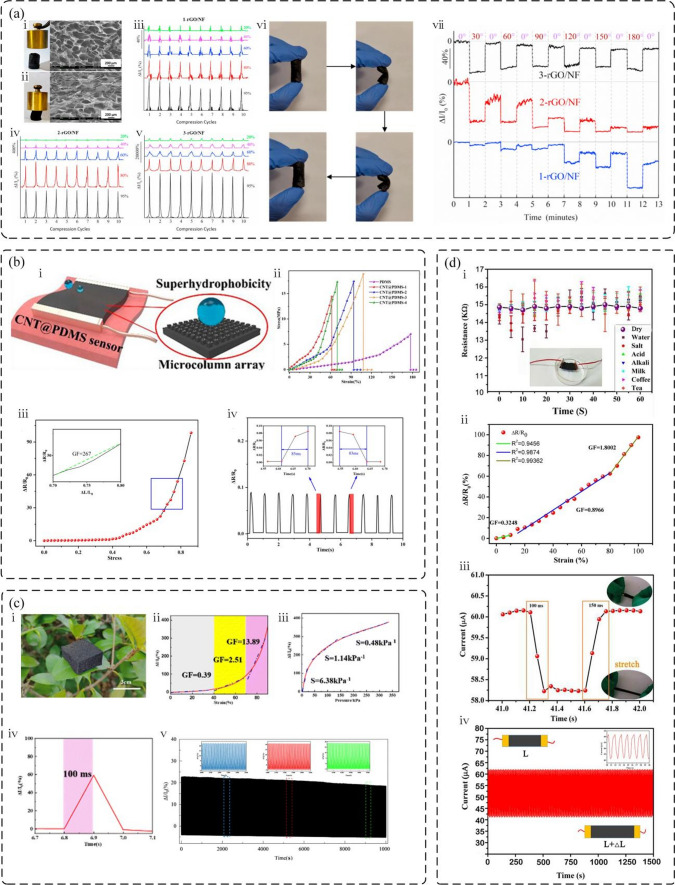

In 2021, Liang et al. [86] fabricated a 3D conductive sponge for wearable tactile pressure sensor by assembling polyacrylonitrile (PAN)/PI electrostatically spun nanofibers as a substrate with reduced graphene oxide nanosheets and then treated them with PDMS (Fig. 9a). They tested the performance of sponges with different graphene oxide contents (1–3 rGO/NF), and concluded that the 3-rGO/NF sponge had the highest porosity (99.23%), low density (11.50 mg/cm3), the largest rate of change of current, and the highest sensitivity during compression, which was suitable for making wearable tactile pressure sensors.

Fig. 9.

Fabrication of superhydrophobic wearable sensors on hybrid substrates. a A 3D conductive sponge based on PAN/PI that can be used as a pressure sensor. (i–ii): The SEM images of 3-rGO/NF 3D nanofibrous sponge in non-compressed state and compressed state. (iii–v): The rate of change of current of the sensor under different degrees of deformation cycling. (vi): Status of 3-rGO/NF sponge during bending process. (vii): Current change ratio of 1-rGO/NF, 2-rGO/NF, and 3-rGO/NF at different angles during bending process. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2021 Published by Elsevier Ltd [86]. b A superhydrophobic wearable strain sensor with anti-/deicing properties. (i): Schematic of the sensor and its superhydrophobicity. (ii–iv): Strain response of the sensor. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society [25]. c Lignin-based PU foam superhydrophobic pressure sensor. (i): Photo of lignin-based PU foam samples placed on leaf. (ii–v): Pressure-sensing response of the sensor. Reproduced with permission. Copyright The Royal Society of Chemistry 2024 [87]. d Superhydrophobic flexible TPE/CNTs air–water boundary masks. (i): The CAs and SAs of different liquid droplets on the surface of the TPE/CNTs film. (ii–iv): Strain sensing behavior of the TPE/CNTs film. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2020 Published by Elsevier B.V [88]

Ma et al. [89] used PDMS as a transfer template to replicate the micro/nano structures on the backside of reed left onto the surface of AgNWs/PCL/PU membranes, and then modified the surface to fabricate a superhydrophobic composite membrane by n-hexadecanethiol (HDT), which had electrical/thermal dual response as well as good self-healing ability. The fabricated composite membrane had good sensing performance and signal detection ability, which could be used as a smart wearable sensor.

In 2024, Zhou et al. [25] fabricated a wearable strain sensor by processing a micro-pillar array on CNTs@PDMS elastomer substrate fabricated by the template method using laser ablation (Fig. 9b). The fabricated sensor had good superhydrophobicity, mechanical strength (fracture stress > 18 MPa), resistance to electrolysis, and good signal detection ability, which can be used as a smart wearable sensor. In addition, the sensor’s good electro-thermal property allowed it to have the anti-icing and de-icing, which would made this sensor had a greater potential for human motion detection.

In 2023, Zhao et al. [87] fabricated graphene/lignin-based PU conductive foam by foaming method and polymerized polypyridine (PPy) on the surface of this base foam to improve its conductivity, and subsequently made the foam hydrophobic by dip-coating with PDMS (Fig. 9c). This foam had excellent pressure sensitivity, fast response time (response time 100 ms), and excellent reliability (good reproduction after more than 2000 cycles), which can be used as an underwater wearable sensor and also for detecting tiny water wave vibration.

In 2020, Ding et al. [88] fabricated a thermoplastic elastomer and carbon nanotubes (TPE/CNTs) composite membrane using a phase separation method (Fig. 9d). This composite membrane had superhydrophobicity and electrical conductivity. As a strain sensor, it had a fast and stable response speed, which allowed for the long-term and reliable detection of the human body’s behaviors in humid environment.

Other substrates

Beside the above different substrates, superhydrophobic wearable sensors have been fabricated with MWCNTs [28, 90, 91], natural latex [92–94], PI [95, 96], graphene [97, 98], paper [26, 99], polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) [100, 101], wood sponge [102], fibers [103], polyvinyl alcohol [104], and other materials [105, 106].

In 2020, Ding et al. [90] fabricated a sandwich-structured superhydrophobic conductive film using MWCNTs as a substrate (Fig. 10a), which can be used for strain sensors with a large variable range (80%), fast and stable response time (60–80 ms), and high stability (up to 1000 stretch-relaxation cycles), which can be used for effective measurement of the pulse rate and other kinds of limb movements.

Fig. 10.

Some other superhydrophobic wearable sensors. a Superhydrophobic strain sensor based on MWCNTs. (i): Schematic of a superhydrophobic membrane. (ii–iv): Response and endurance testing of strain sensors. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2020 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved [90]. b Multifunctional bionic sensor for underwater. (i): Schematic of CNT@SiO2-Sensor. (ii): Response mechanism of CNT to humidity. (iii–iv): Response time and recovery time of CNT@SiO2 sensor to ambient humidity and airflow humidity. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024 Elsevier B.V [92]. c PI-based wearable fluid capture device. (i–vii): Laser-induced graphene. (viii): Schematic of glucose within the electrode. (ix): Schematic of the process of generation of H2O2 due to the glucose oxidase. x: Current time response obtained on graphite electrodes. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society [95]. d A graphene-based superhydrophobic sponge. (i): F-rGO@GAF/PDMS pressure sensor. (ii–iv): Response and durability testing of stress sensors. Reproduced with permission. Copyright The Royal Society of Chemistry 2024 [98]. e Bionic paper-based superhydrophobic wearable strain sensors. (i): Paper-based superhydrophobic strain sensors. (ii–iv): Response and endurance testing of strain sensor. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society [26]

Sun et al. [92] fabricated a multi-functional sensor simulating human skin by sequentially constructing MWCNTs sensing layer and an organosilicon dioxide hydrophobic layer on natural latex (Fig. 10b), which could detect human respiration by sensing humidity. This sensor had a shorter response time (0.8 s for an airflow velocity of 1.3 m/s at 0.8 s) and could be used to monitor physiological signals, such as breath and movement of divers.

Li et al. [95] processed graphene arrays on a PI substrate (Fig. 10c), which gave it controllable super-wettability and electrical conductivity, which could make it an electrochemical sensor. Its detection limit was 6 μM when used for H2O2 detection, which had a greater potential for application in the physiological and health detection in the human body. It had great potential for application in human physiological health detection.

Just in 2024, Luo et al. [98] fabricated a composite sponge with graphene as a substrate that can be used as a pressure sensor (Fig. 10d). The combination of PDMS and the graphene fragments (GFA) enabled the sponge to have good mechanical property, and maintained good stability after 1000 loading cycles. In addition, the reduced graphene oxide particles formed a synergistic conductive network, which enhanced its conductivity and enabled the sensor to reach a sensitivity of 6.9 kPa−1, which was effective in discriminating human movement even in humid environment. Paper-based strain sensor had super-low strain resolution (0.098%), but the paper-based sensors would easily fail in wet or watery environments (Fig. 10e).

Therefore, Liu et al. [26] used a biomimetic strategy to fabricated a superhydrophobic strain sensor with a water contact angle of up to 164°, a fast response time (78 ms), and a good stability (12,000 cycles). The sensor was not only suitable for real-time monitoring of human body movement, monitoring the submerged subtle vibration, but also had the potential to be applied in underwater robotic. Table 2 shows a summary of the properties exhibited by each of these various substrate materials under different preparation methods.

Table 2.

Typical superhydrophobic wearable sensors

| Substrates | Fabrication methods | Contact angle | GF | Response time | Range | Cyclic stability | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDMS | Sprayed CB | 150 ± 2.83° | – | 168 ms | 0–70% | > 1000 (in 0–10% strain) | [56] |

| Sprayed MWCNTs | 157.3° | 33.08 | 62 ms | 0–60% | > 1000 (in 0–20% strain) | [57] | |

| Laser engraving of PDMS and CNT mixtures | 155° | 3.1 | – | 0–100% | > 5000 (in 0–100% strain) | [55] | |

| Template method | > 150° | 22.64 | – | 0–170% | > 10,000 (in 0–10% strain) | [66] | |

| PU | Assembly after layered manufacturing | 160° | 2.12 | 35 ms | 0–50% | > 1000 (in 21 kPa) | [23] |

| Electrostatic spinning and ultrasonic assembly | 153.6° | 145 | – | – | > 10,000 | [75] | |

| spraying method | 164° | 141.4 | 471.03 ms | – | > 1000 | [77] | |

| Rubber | Modified with silver nanoparticles and PDMS | 156° | 3.6 × 108 (in 60% strain) | – | 0–60% | > 25,000 (in 30% strain) | [78] |

| Modified with gas-phase SiO2 treatment | 156° | 685.3 (in 482% strain) | 200 ms | 0–482% | > 1000 | [80] | |

| PDMS coated followed by conductive CB nanoparticles | 156° | 101.75 | 83 ms | 0–460% | > 10,000 | [5] | |

| Gel | Silver nanowires coated with SiO2/PDMS | > 150° | 80 | 78 ms | 0–70% | > 1800 (in 50% strain) | [60] |

| Assembly of silicone elastomer/SiO2 particulate composite films | 152.7° | 4.08 | 120 ms | 0–100% | > 400 (in 50% strain) | [83] | |

| Fabric | Deposition of conductive silver patterns | 166° | 295.3 ± 0.04 (n = 5) µA/mM cm2 | – | 0.05–70 μM | > 100 | [7] |

| Fabrication of coatings | 162° | 2.53 × 10–5 mA/° | – | 0–180° | 2500 kneading test | [62] | |

| Hybrid Substrates | A one-step in-situ strategy | 150.25° | 0.916 (1 kPa) | 100 ms | 0.5–23 kPa | 60 | [100] |

| Foaming process | 154.2° | 6.38 kPa−1 | 100 ms | 0–25 kPa | > 2000 | [87] | |

| Phase separation | 160° | 1.8002 (ε = 81.5–100%) | 100 ms | > 76% | 1000 | [88] | |

| Paper | Sputtering of AgNPs | 164° | 263.34 | 78 ms | Ultimate elongation 2.917% | 12,000 | [26] |

| MWCNTs | Spraying TPE | 169.4° | 69.84 (65–80%) | 60 ms | 80% | 1000 | [90] |

| Natural rubber latex | Penetration of CB | 155.2° | 13.8 (10–50%), up to 13,000 (> 50%) | 28 ms | 0.05–300% | 1000 | [94] |

Applications of superhydrophobic wearable sensor

With the rapid development of superhydrophobic wearable sensors in recent years, they have shown wide application prospects in the fields of health monitoring [107], intelligent identification [108], and Internet of Things(IoT) [109]. The superhydrophobicity of the sensor surfaces can effectively reduce the interference of the liquid to the sensor, thus achieving accurate and stable monitoring in the wet environment. The superhydrophobic wearable sensors also have high sensitivity to monitor the physiological signals in real time, which has great application prospects in medical, rescue, IoT, and other fields. In daily life, superhydrophobic wearable sensor can also help users find health problems in time and take measures. In the future, with the continuous progress and breakthrough of science and technology, superhydrophobic wearable sensors are expected to play an important role in more advanced fields. This section aims to summarize some advanced research progress in five main applications, highlighting some representative works in these fields.

Motion detection

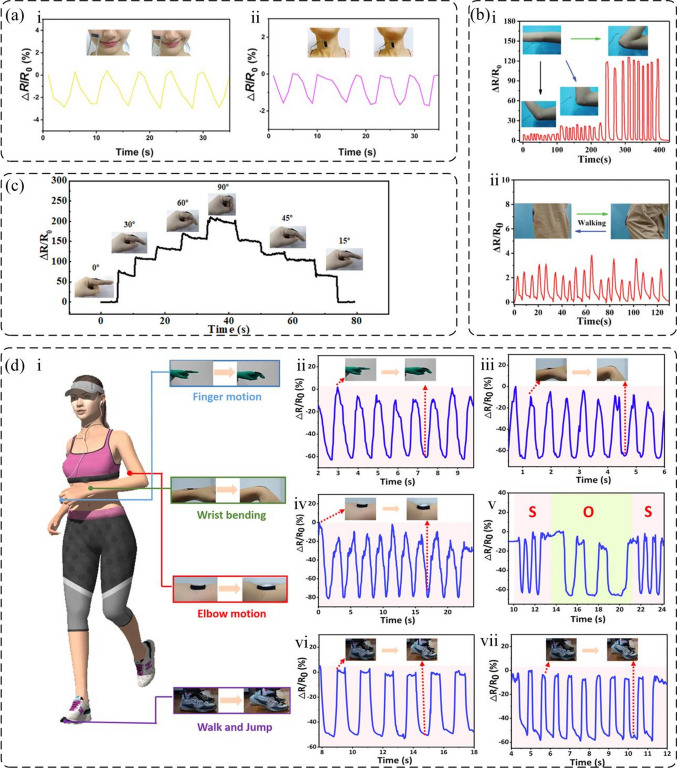

Physical signal detection is a key application field, and superhydrophobic wearable sensors with excellent adaptability [60], stretch-ability [110], and stability [62] characteristics, have shown enormous potential to achieve long-term monitoring during wearing [77]. These sensors can be utilized for monitoring various physical signals generated by human body, such as torsion, elbow bending, finger bending, and wrist changes, thereby facilitating the use of portable behavior monitoring and remote information feedback [82]. Bu et al. [111] fabricated a superhydrophobic micro-crack conductive paper-based strain sensor by coated coating the printing paper with conductive material Ti3C2Tx MXene and deposing superhydrophobic candle dust layer on the surfaces. The sensor shows high sensitivity, ultra-low detection limit, and good resistance to bending deformation fatigue in the strain range of 0–0.6. It is not only suitable for torsion deformation detection, but also micro-movement (like smile and swallow), showing an excellent perception of this movement, as shown in Fig. 11a. Gao et al. [1] fabricated a superhydrophobic and conductive coating by a simple spraying method on an elastic band with multistage fluorocarbon nanotubes (FCNT)/SiO2 nanoparticle structure. The coating has the good tensile property, strong corrosion resistance, and excellent durability, which can be installed on some important human body parts, like the elbow (Fig. 11b). The observation of inductive behavior at elbow bending, corresponding to a relatively large strain, indicated that the sensor had broad application prospects in wearable strain sensors that could be used for human motion detection. Ma et al. [2] proposed a superhydrophobic nanocoated wearable textile composite (SNWTC) strain sensor with excellent liquid repulsion, excellent strain sensing performance and mechanical stability in the underwater environment. When the sensor was installed on the finger, the intensity of the electrical signal increases synchronously with the finger bending angle, as shown in Fig. 11c. Therefore, the SNWTC sensor could accurately identify finger bending behavior at different angles, showing a broad application prospects for underwater sensing. He et al. [3] designed a cotton-based superhydrophobic PPy/MXene pressure sensor with excellent sensing performance, fast response, and good stability, which can be mounted on the main body parts (such as finger, elbow and wrist) to monitor human movement, as shown in Fig. 11d. The signal output can be changed with the rhythm of human movement in real time, showing the high sensitivity and repeatability of the sensor. The generated signals can be sent to the mobile terminals when activated by bending the wrist, and thus monitoring the human activity. In addition, sensors can be also used to test walking and jumping. Therefore, superhydrophobic wearable sensors can be used to monitor the daily human activity for a long term.

Fig. 11.

Application of superhydrophobic wearable sensor in motion detection. a Application of a superhydrophobic micro-crack conductive paper-based strain sensor in motion detection. (i): Smile detection. (ii): Swallowing detection. Reproduced with permission [60]. Copyright 2021 Science China Press. Published by Elsevier B.V. and Science China Press. All rights reserved. b Application of an elastic band with multistage fluorocarbon nanotubes (FCNT)/SiO2 nanoparticle structure. (i): Elbow bending detection. (ii): Leg bending detection. Reproduced with permission [1]. Copyright The Royal Society of Chemistry 2019 (c) Finger bending detection. Reproduced with permission [2]. Copyright The Royal Society of Chemistry 2023 (d) Application of a cotton-based superhydrophobic PPy/MXene pressure sensor in motion detection. (i): Whole body motion detection. (ii): Finger motion detection. (iii): Wrist bending detection. iv: Elbow motion detection. (v): Signal with wrist bending. (vi): Walking detection. (vii): Jumping detection. Reproduced with permission [3]. Copyright 2022 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved

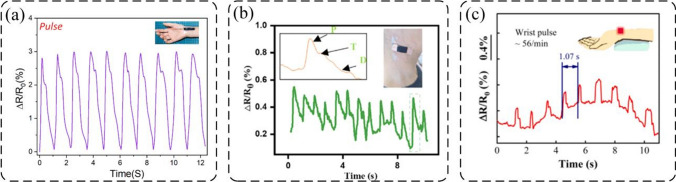

Pulse detection

In the field of tactile sensing, the precise capture of weak signals is an important aspect of sensor sensitivity. The human pulse signal, a universal and weak signal, cannot be accurately captured by traditional stress–strain sensors. Therefore, high precision wearable sensors are needed for signal recognition and conversion. Pulse detection is an integral part of assessing human health, not only providing an immediate reflection of the beat, but also revealing the efficiency and stability of the circulatory system. By monitoring the rate, rhythm, and strength of the pulse, it is possible to initially diagnose a wide range of disease states. Human pulse is a tiny physiological signal that is prone to change due to daily activities, so higher requirements are put forward for the sensing range and sensitivity of strain sensors. Superhydrophobic wearable sensors are highly sensitive [90], antifatigue [102], and identifiable [112], thus performing well in the field of low-frequency mechanical energy harvesting, and showing great promise in the field of pulse detection. Chen et al. [4] fabricated a novel catechol sensor of PVA-CA/ poly (n-acrylylglycine) /MXene hydrogel (PcNA-M) by combining the thermal sensitivity of poly (n-acrylylglycine) (PNAGA) hydrogel and the self-powered properties of PVA (Pc) /MXene hydrogel catechol functionalization. The superhydrophobic wearable sensor had good tensile, compressive, and resilient properties, and its resistance and voltage signal could respond to the state of the human body, which could be used to monitor human physiological signals from the pulse, as shown in Fig. 12a. Yao et al. [5] proposed an extremely durable SS/ PDMS-CBNPS superhydrophobic strain sensor with an ultra-wide sensing range, by introducing a conductive carbon black nanoparticles (CBNPs) onto an elastic silicone rubber sheet (SS) coated with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), which has excellent sensing performance and the ability to identify extremely weak vibration. Carotid pulse is a tiny physiological signal that is prone to change due to daily activities, so higher requirements are put forward for the sensing range and sensitivity of strain sensor. By fixing the sensor to the position of the carotid artery, a stable pulse signal could be detected, as shown in Fig. 12b, which could be used to assess the risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease. Chen et al. [83] fabricated a superhydrophobic flame retardant piezoresistive pressure sensor by a simple freeze-drying, coating, and spraying method to construct a conductive, superhydrophobic and flexible composites substrate. The sensor is not only capable of detecting large-scale limb movements, but also small-scale human movements, such as human radial pulse, as shown in Fig. 12c, which shows that the sensor has great potential in wearable electronics, medical monitoring, and intelligent robotics. Dong et al. [6] proposed a super-stretch self-cleaning textile-based bioelectrode with outstanding health monitoring performance and excellent anti-fouling ability, which can be used for skin adaptive bioelectrode to continuously monitor electrophysiological signals. To obtain an electrocardiograph (ECG) signal, two PTCCS electrodes were installed on the chest of a volunteer with a wireless ECG, and the ECG signal could be received by a smartphone via a Bluetooth connection, thus facilitating its practical application in personal health monitoring.

Fig. 12.

Application of superhydrophobic wearable sensors in pulse detection. a Radial pulse signal. Reproduced with permission [4]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. b Carotid pulse signal. Reproduced with permission [5]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society. c Wrist pulse signal curve, about 56/min. Reproduced with permission [83]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved

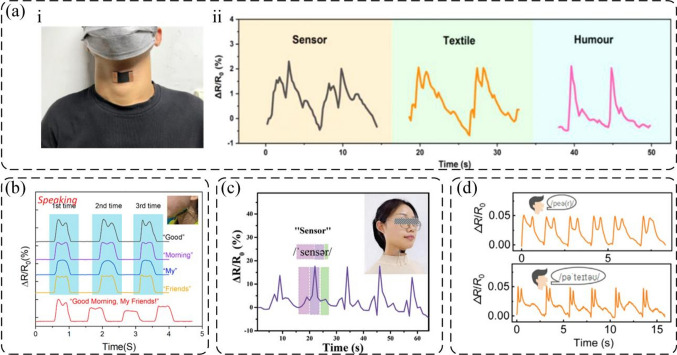

Voice detection

Speaking is the most frequent activity of daily human communication, and sound is produced by vibration of the glottis. Conventional sensing sensors are often constrained by rigid structures and limited sensitivity, making it difficult to accurately sense and quantify pronation tests. Superhydrophobic wearable sensors have the advantages of light weight [78] and excellent sensing performances [72], which can be used to detect voice based on subtle vibrations [58]. Sun et al. [27] fabricated the conductive suede sensor by integrating carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes (C-MWCNT) polydopamine (PDA), and hexadecyl trimethoxysilane. The sensor can be used to detect throat vibration when installed on the throat skin of volunteers (Fig. 13a). The sensor can easily capture the small skin deformation caused by throat movement with high accuracy. Different words correspond to different waveforms, and the shapes of the same word were highly overlapping. The output electrical signal could be recognized by its unique pattern and further analyzed by the computer to recognize the word being spoken, making the sensor have great application prospects in electronic speech assistance, human–computer interaction and speech rehabilitation training applications. Chen et al. [4] fabricated a PcNA-M sensor, demonstrating high sensitivity, recognizability and reliability in self-powered wearable sensor applications. As shown in Fig. 13b, when the volunteers uttered the words “Good morning, my friend”. a correlated characteristic spike was observed in vocal cord vibrations. In addition, when the same phrase was spoken three times, the same resistance signal can be observed. Liu et al. [24] fabricated a conductive polyimide nanofiber (PINF) /MXene composite aerogel piezoresistive sensor, supporting multistage nanofiber honeycomb structure, which had excellent sensing capability, ultra-low detection limit, strong fatigue resistance, excellent piezoresistive stability, and stability in extremely harsh environments. According to the compression effect caused by vocal cord vibration, the voice could also be clearly recognized when the sensor was connected to the throat, as shown in Fig. 13c. Sun et al. [80] fabricated a superhydrophobic strain sensor by constructing synergistic carbon nanotubes (CNTs)/reduced graphene oxide (rGO) double conductive layers to decorate elastic rubber bands (RB) and treated them with fumed silicon dioxide (Hf-SiO2). In addition to detecting violent human movements, the subtle throat muscle movements caused by vocalizations could also be accurately and timely captured by a fabricated sensor attached to the speaker’s neck. As shown in Fig. 13d, words with different syllables, such as the two-syllable word pear and the multi-syllable word potato, could be distinguished. The result showed the high sensitivity and unique mode of the sensor.

Fig. 13.

Application of superhydrophobic wearable sensors in voice detection. a Application of a superhydrophobic conductive suede sensor in voice detection. (i): Photograph of wearing. (ii): Voice signal curve. Reproduced with permission [27]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society. b the signal curve while speaking “Good Morning, My Friends”. Reproduced with permission [4]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. c Repeatable articulatory signal curve. Reproduced with permission [24]. Copyright 2021 Wiley–VCH GmbH. d different signal curves of “pear” and “potato”. Reproduced with permission [80]. Copyright 2022 Science China Press. Published by Elsevier B.V. and Science China Press. All rights reserved

Sweat detection

The human body engages in cutaneous respiration all the time, which is accompanied by perspiration and promotes the body’s metabolism. Traditional sweat sensors are often affected by humid and corrosive environments that reduce sensitivity. The use of superhydrophobic wearable sensors for sweat detection is a non-invasive means of biological monitoring, which not only reflects the immediate physiological state of the human body, but also helps to detect potential health problems and serves as a window for early diagnosis of some diseases such as diabetes. In addition, the detection of sweat also provides scientific basis for outdoor sports and personalized drug treatment. Therefore, sweat detection plays an indispensable role in health management, disease prevention, and diagnosis [7]. Chen et al. [9] fabricated a flexible electrode on polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate using fluoroalkyl silane functionalized Ti3C2Tx (F–Ti3C2Tx) and polyaniline (PANI) films by a simple, low-cost screen-printing technique. The as-fabricated electrochemical sweat pH sensor could continuously monitor the concentration of hydrogen ions in human sweat in real time, so as to measure PH value, and used as a basis for judging human health(Fig. 14a). The pH value of sweat decreased with the increase of exercise intensity, which was consistent with the conclusions of studies in sports medicine, indicating the great application potential of this sensor in the field of electrochemical sensing. Jin et al. [8] fabricated a carbon/hydrogel/enzyme nanocomposite electrode by sequential deposition of high-porosity carbon nanoparticles and hydrogel nano-coatings to achieve sensitive and stable sweat detection. Real-time in vitro sweat analysis was performed by placing sensor-sensing patches on the forehead and arm skin of volunteers, as shown in Fig. 14b. The response of the patched to two body parts were monitored after the volunteers drank cola. In addition, the sweat outflow during running and then resting was also monitored and the lactic acid sensing performance of the patches was tested.

Fig. 14.

Application of superhydrophobic wearable sensors in sweat detection. a Application of a superhydrophobic electrochemical sweat pH sensor in sweat detection. (i): Photograph of the device including the sensor. (ii): Signal curves for continuous real-time monitoring of the pH value in sweat. Reproduced with permission [9]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society. b Application of a superhydrophobic chemical sensor in sweat detection. (i): The signal curve of the glucose sensor on the arm after drinking cola. (ii): The signal curve of the glucose sensor on the forehead after drinking cola. (iii): The signal curve of the lactate sensor on the arm after exercising. (iv): The signal curve of the lactate sensor on the forehead after exercising. Reproduced with permission [8]. Copyright 2024 Wiley–VCH GmbH

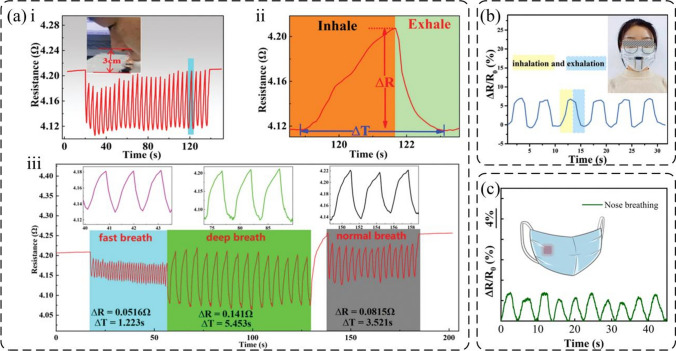

Breath detection

Breathing is one of the necessary parts of human activity and one of the most important manifestations of human functioning. Airflow sensors are extensively equipped and playing a vital role in aerospace, weather forecast, mining industry, environmental monitoring, biomedical engineering, wearable textiles, and integrated smart devices. Superhydrophobic piezoresistive strain/pressure sensors have the advantages of low detection limit, fast response, fast recovery, and good sensitivity, and can also eliminate the influence of moisture or water droplets in practical applications, due to the fact that superhydrophobic surfaces enable the sensors to work normally in the harsh environment with high humidity and even in the rain, which can be used in respiratory health monitoring. Qi et al. [28] developed a wearable robust bridge-type airflow sensor based on flexible superhydrophobic carbon nanotube fiber film. Compared with the previously reported flexible carbon-based air flow sensor, the recovery time was reduced by about 2/3. The R-T curve of the sensor in response to normal breathing showed that the sensor resistance decreases during inhalation and increases during exhalation (Fig. 15a), which showed the sensitivity of the sensor. Respiratory rate and amplitude showed statistically significant differences between rapid, deep, and normal breathing. Liu et al. [24] fixed a superhydrophobic sensor on the mask, outputting a stable and regular signals during inhalation and exhalation, as shown in Fig. 15b. Superhydrophobic sensor provided a simple, low-cost, and efficient method for long-term respiratory monitoring. Chen et al. [83] fabrication a superhydrophobic and flame retardant piezoresistive pressure sensor to detect the respiratory rate and intensity, as shown in Fig. 15c. Under normal breathing, the periodic airflow in the nasal cavity caused slight deformation of the sensor, resulting in changes in periodic resistance. According to the results, the respiratory frequency was calculated to be 13.3 times/min, which is in line with the physiological characteristics of normal adults.

Fig. 15.

Application of superhydrophobic wearable sensors in breath detection. a Application of a wearable robust bridge-type airflow sensor in breath detection. (i): The signal curve of sensors responded to normal breathing. (ii): Enlarged from the shallow blue shade part. (iii): The signal curve of sensors responded to the fast breath-deep breath-normal breath. Reproduced with permission [28]. Copyright 2023 The Authors. Advanced Materials Interfaces published by Wiley–VCH GmbH. b The signal curve of inhalation and exhalation. Reproduced with permission [24]. Copyright 2021 Wiley–VCH GmbH. c The signal curve of nose breathing. Reproduced with permission [83]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved

Other applications

In addition to the above applications in the field of detecting motion, pulse, voice, sweat, and breath, superhydrophobic wearable sensors can also perform real-time gait detection, temperature detection, becoming increasingly popular in numerous fields. Superhydrophobic wearable sensors can convert physical signals into digital signals by detecting information such as human movement for processing by computers, smartphones or other smart devices. These data are then transmitted via wireless networks to the cloud or local servers for analysis, processing, and storage, enabling real-time monitoring of the environment, intelligent control and predictive maintenance. Ma et al. [89] fabricated a flexible super-hydrophobic shape memory film (SSMF) with high strain sensitivity. The surface topography of SSMF could be fine-tuned by reversible stretching/recovery, and its good adaptability and durability made it useful as a super-hydrophobic smart wearable sensor attached to human skin. To achieve comprehensive real-time detection of human movement and intelligent control of the Internet of Things (IoT), a SSMF sample was attached to the finger joints of the index finger (sensor A) and middle finger (sensor B) to control the IoT by recognizing the movement of the finger joints. Two fingers connected to the SSMF can issue different commands, which gives good control over the micro-LCD (Liquid Crystal Display) and PowerPoint (Fig. 16a). Such kind of smart sensors offer great convenience for controlling home appliances and will lead to considerable advances in smart and wearable electronics with versatility and moisture resistance for a wide range of applications, such as artificial electronic skins for controlling the IoT. Besides, superhydrophobic wearable sensors can also monitor temperature in real time, and its stability and accuracy make temperature detection more reliable, which are expected to be applied in the medical and health industry and industrial production in the future. Wang et al. [29] used the redox-induced electricity principle of static water droplets in self-powered wearable electronic devices to create a superhydrophobic wearable temperature sensor, which can be driven by using water droplets. The nanostructured superhydrophobic surfaces can be not only used to improve the electrical output, but also improve the mechanical stability. When three NaCl droplets were dropped on the sensor surfaces, it can work continuously and displayed the temperature data of the human finger, as shown in Fig. 16b.

Fig. 16.