Key Points

Question

Are barriers to divorce during pregnancy and reproductive health care access correlated with pregnancy-associated homicide rates in the US?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study of state-level pregnancy-associated homicide rates from 2018 to 2021, rates were significantly higher in state-years that prohibit finalizing divorce during pregnancy and with more barriers to reproductive health care. The specific barriers associated with homicide risk varied based on how the person killed knew the suspect, and the racial and ethnic group of the person killed.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that, in the US, major barriers to divorce and reproductive health care pose a serious health risk to pregnant or recently pregnant females, given their association with homicide risk.

Abstract

Importance

Barriers to divorce and reproductive health care can threaten the health and safety of pregnant and recently pregnant females.

Objective

To examine state laws about divorce, reproductive health care (access to contraception, family planning services, and abortion), and pregnancy-associated homicide rates in US states over a 4-year period (2018-2021).

Design, Setting, and Participants

In this cross-sectional study, bivariate tests and regressions were used to analyze crude rates of pregnancy-associated homicide from the National Violent Death Reporting System in 181 state-years for calendar years 2018 to 2021, with analyses conducted on September 8, 2024.

Exposures

Access to divorce while pregnant and reproductive health care over a 4-year period in the US.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcomes (pregnancy-associated homicide by intimate partners vs non–intimate partners and rates among younger Black, Hispanic, and White females) were assessed using the National Violent Death Reporting System. Negative binomial regression was used to test 2 hypotheses: access to divorce while pregnant and reproductive health care are associated with pregnancy-associated homicide rates.

Results

Individual level data, including exact sample size, were not available in this study of state-level homicide rates. Negative binomial regression analysis showed that, where finalizing divorce during pregnancy is prohibited, intimate partner homicide rates (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 2.11; 95% CI, 1.09-4.08; P = .03) and rates among younger (age 10-24 years) White females (IRR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.12-5.09; P = .02) were significantly higher. In state-years with greater access to reproductive health care, rates were significantly lower for non–intimate partner homicide (IRR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.87-0.98; P = .01) and for younger Black females (IRR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87-0.96; P < .001) and younger Hispanic females (IRR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79-0.96; P = .007).

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study of pregnancy-associated homicide rates, barriers to divorce were associated with higher homicide rates and access to reproductive health care was associated with lower homicide rates. This study highlights the association between state legislation and pregnancy-associated homicide in the US, which is important information for policymakers.

This cross-sectional study examines the association of state laws limiting divorce during pregnancy and access to reproductive health care with rates of pregnancy-associated homicide.

Introduction

Homicide is a leading cause of death for pregnant women in the US.1,2,3,4,5,6 More women die from pregnancy-associated homicide (while pregnant or in the year after pregnancy), than other causes of maternal mortality, such as preeclampsia or hemorrhage.7,8 Rates of pregnancy-associated homicide vary by age and race, with individuals younger than 25 years and Black women at highest risk,1,2,3,4,5,6,9,10,11 and the largest proportion is committed by an intimate partner.3,4,6

While increased access to divorce has been shown to decrease rates of intimate partner homicide (IPH) in general,12,13 divorce laws could also shape pregnancy-associated IPH if they pose obstacles to finalizing a divorce during pregnancy. Recently, the inability of women to finalize a divorce while pregnant in Missouri was highlighted, where anyone petitioning for divorce must disclose pregnancy, and a pregnancy will delay finalizing divorce. Since Missouri State Representative Ashley Aune called attention to this, journalists have highlighted additional states with similar barriers in place, where judges are known to wait until after the child’s birth to finalize a divorce, and how this practice could worsen intimate partner violence (IPV).14,15,16

Intimate partner violence and pregnancy-associated homicide are also intertwined with access to reproductive health care. Unintended pregnancies are more likely to occur in violent relationships,17,18 as they frequently involve a complex web of psychological, emotional, and/or sexual abuse.19,20,21 Reproductive coercion is one form of IPV that can result in unintended pregnancies through rape, sexual assault, sabotaging contraception, and restricting women’s contraception use through threats, violence, coercion, or control.22,23,24 Women who experience IPV during their pregnancy are more likely to miss prenatal appointments or delay starting prenatal care until late in their pregnancy,18,25,26 and there is a higher risk of pregnancy-associated homicide among women who receive no or late prenatal care.5 Barriers to reproductive care and delays in starting prenatal care have major implications. In many states, women lack options if they do not seek care until after passing a particular gestational stage. As of this writing in 2024, 17 states have passed total abortion bans or abortion bans at 6 weeks, before women typically have their first prenatal appointment.27

In 2022, the US Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade, which provided federal protections for abortion access; when it was overturned, states were able to fully ban the procedure. Although there were not outright bans during the years 2018 to 2021, the period of current study, there were more than 350 state restrictions in place, preventing full access to abortion services even before Roe v Wade was overturned.28 Research conducted prior to the overturning of Roe v Wade found that individuals’ access to abortion is associated with a reduction in violence by the man involved with the pregnancy,29 and on the state level, states with more abortion barriers report higher rates of both maternal mortality30 and infant mortality.31 This association is not only isolated to nonviolent causes of death. In recent studies, rates of IPH were higher in states with more laws that regulate abortion providers,32 and states categorized as restrictive of abortion access had higher rates of peripartum homicide.33

To our knowledge, the current study is the first that examines the correlation between state divorce laws and pregnancy-associated homicide rates. The current study also expands previous research by examining the association between pregnancy-associated homicide rates and a range of both restrictive and expansive state-level policies on reproductive health care that vary year to year including, but not limited to, abortion. We examine these patterns over time (calendar years 2018-2021), including pregnancy-associated homicide rates for those killed by an intimate partner and those killed by someone other than an intimate partner. We also examine rates of pregnancy-associated homicide across racial and ethnic groups among younger females (age 10-24 years), as research reports significant differences in rates across racial and ethnic groups,9,11 and the highest rates are found among younger women.8 Based on previous research, this study tested 2 hypotheses. The first hypothesis is that states in which divorce cannot be finalized while a spouse is pregnant will have higher rates of pregnancy-associated homicide. The second hypothesis is that states with greater reproductive health care access (including contraception, family planning services, and abortion) will have lower rates of pregnancy-associated homicide.

Methods

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administers the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS).34 The NVDRS integrates data on violence from multiple sources, including law enforcement, medical examiners/coroners, and death certificates, and includes data on homicide, suicide, firearm-related deaths, deaths from legal intervention, and other causes of violent death. The dataset includes more than 600 data elements and thus provides considerable detail about individual incidents, including information about the injury, circumstances, and extensive demographic information. Beginning with 40 states at the start of the study period (2018), the NVDRS contained 3 additional states in 2019 and included data from 49 states in 2020 and 2021 (Washington, DC, and all states except Florida and Hawaii). Because data were collected in each participating state and year, the unit of analysis is the state-year (N = 181 state-years). Given its use of secondary, aggregated data, the study received exempt status from the institutional review board of the University of South Carolina. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Pregnancy-Associated Homicide Rates

The Web-Based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS) calculates crude rates of violent deaths as captured in the NVDRS. Various filters can be selected in WISQARS, including whether the individual was pregnant at the time of death or within a year of their death. WISQARS was used to calculate the crude rate of intimate partner and non–intimate partner pregnancy-associated homicide rates in each state-year for females from all age groups, although WISQARS calculates this rate per 100 000 females of reproductive age (15-49 years). WISQARS was also used to calculate crude rates for females aged 10 to 24 years who are at higher risk for pregnancy-associated homicide, across racial and ethnic identity: non-Hispanic younger Black females, younger Hispanic females of all races, and non-Hispanic younger White females. In the NVDRS, the females’ race and ethnicity is coded based on how it was reported in the source documents provided (eg, death certificate or medical examiner’s report).

Barriers to Finalizing Divorce

In recent months, news publications have highlighted barriers to divorce during pregnancy, for instance, so that paternity can be confirmed and child support can be arranged before the case is finalized.14,15 While these articles highlighted that divorces may not be finalized as a matter of practice in various states, the publications agreed that finalizing divorce during pregnancy is prohibited in Arkansas, Missouri, and Texas. This coding was informed by a fact check conducted by the periodical USA Today, in which legal experts in these states were consulted.16 In 8 of the 181 state-years, finalizing divorce is prohibited (4%).

Reproductive Health Care Access

A recent study35 published state-level policies that restricted and expanded access to reproductive health care from 2006 to 2021. The authors analyzed 20 expansive policies, for instance, related to insurance coverage, Medicaid, protections for minors and dependents, and who can dispense contraception, along with 3 restrictive policies, such as restrictions on state family planning funds. For each state-year, count variables were calculated for expansive policies and for restrictive policies.

The Guttmacher Institute produced a series of annual reports that identify states in which abortion barriers are in place, which included license requirements (eg, who can perform an abortion), gestational limits, partial-birth abortion restrictions, restrictions on public funds and private insurance, mandatory counseling, mandatory waiting periods, and laws that permit individual health clinicians or institutions to refuse care; and requirements that parents consent to a minor’s abortion or are notified about a minor’s abortion.27 For each state-year, a count variable was calculated, summing the number of types of abortion barriers, ranging from 0 to 9.

Because measures of reproductive health policies and abortion barriers are highly correlated (ρ = −0.74, P < .001), an index was created for regression analysis. For each state-year, the number of restrictive reproductive health care policies and abortion barriers were subtracted from the number of expansive reproductive health care policies. This results in a Reproductive Health Care Access Index ranging from −8 to 17 (mean [SD], 3.227 [6.630]), with higher scores indicating greater access. For example, if a state-year had every abortion barrier (9) and every restrictive health care policy (3) and 0 expansive policies (0 of 20), their Reproductive Health Care Access Index score would be −12. A state with no abortion barriers or restrictive health care policies and every expansive policy would have a score of 20.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted on September 8, 2024. Like other violent crimes, pregnancy-associated homicide rates are not normally distributed, which was confirmed by Shapiro-Wilk tests of normality. The z scores ranged from 7.12 to 9.67, and all reached significance, indicating nonnormality (P < .001). Due to nonnormality, for bivariate analysis, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to determine whether homicide rates were significantly higher when finalizing divorce is prohibited during pregnancy. This is a common nonparametric test used for independent samples and dichotomous independent variables. The z statistic and significance levels are reported. To determine whether homicide rates are correlated with the number of restrictive and expansive reproductive health care policies and abortion barriers, variables that range from 0 to 20, Spearman correlation was used, which is an appropriate test to detect associations between continuous variables with nonnormal distributions.

Negative binomial regression was used because the dependent variables are nonnormal and overdispersed. A control variable for location in the southern US and fixed effects for years are included, given regional and year-to-year variation in reproductive health care access. Robust SEs are clustered by state in these 2-sided unpaired tests. Analyses were completed using Stata Software, release 17 (StataCorp LLC).

Results

Individual level data, including exact sample size, were not available in this study of state-level homicide rates. Pregnancy-associated homicide rates, calculated per 100 000 reproductive-aged females in each state-year, are listed in Table 1. Mean (SD) IPH (0.11 [0.18]) was higher than non-IPH (0.03 [0.08]). For racial and ethnic groups, the highest rates were found among younger Black females (0.43 [1.02]), followed by younger Hispanic females (0.10 [0.41]) and younger White females (0.03 [0.07]).

Table 1. Barriers to Finalizing Divorce While Pregnant and Pregnancy-Associated Homicide Rates per 100 000 Females of Reproductive Age.

| Variable | Mean (SD) [range] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| All state-years (N = 181) | Can finalize divorce while pregnant (n = 173) | Finalizing divorce prohibited (n = 8 state-years) | |

| Intimate partner rate | 0.11 (0.18) [0.00-1.62] | 0.10 (0.18) [0.00-1.62] | 0.26 (0.14) [0.04-0.51] |

| Non–intimate partner rate | 0.03 (0.08) [0.00-0.58] | 0.03 (0.08) [0.00-0.58] | 0.04 (0.05) [0.00-0.15] |

| Younger Black female rate | 0.43 (1.02) [0.00-7.50] | 0.39 (1.00) [0.00-7.50] | 1.36 (1.20) [0.00-3.35] |

| Younger Hispanic female rate | 0.10 (0.41) [0.00-4.34] | 0.10 (0.41) [0.00-4.34] | 0.21 (0.49) [0.00-1.42] |

| Younger White female rate | 0.03 (0.07) [0.00-0.35] | 0.03 (0.07) [0.00-0.35] | 0.11 (0.08) [0.00-0.22] |

Pregnancy-associated homicide rates of all types were higher where divorce cannot be finalized during pregnancy than in states without this barrier (Table 1). Wilcoxon rank-sum tests indicated this difference is significant for all groups except younger Hispanic females (Table 2).

Table 2. Barriers to Finalizing Divorce While Pregnant and Pregnancy-Associated Homicide Rates: Wilcoxon Rank Sum Tests.

| Variable | Absolute z score | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Intimate partner rate | 3.42 | .001 |

| Non–intimate partner rate | 2.45 | .03 |

| Younger Black female rate | 3.51 | .001 |

| Younger Hispanic female rate | 1.66 | .17 |

| Younger White female rate | 3.87 | .001 |

Spearman correlations reported in Table 3 show more expansive reproductive health care policies were negatively associated with pregnancy-associated homicide rates among younger Black females (ρ = −0.20; P = .006) and younger White females (ρ = −0.23; P = .002). More-restrictive policies were positively associated with all types of homicide rates, except among younger White females.

Table 3. Reproductive Health Care Policies and Pregnancy-Associated Homicide Rates per 100 000 Females of Reproductive Agea.

| Variable | Expansive policies | Restrictive policies | Abortion barriers | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ρ | P valueb | ρ | P valueb | ρ | P valueb | |

| Intimate partner rate | −0.08 | .28 | 0.22 | .003 | 0.23 | .002 |

| Non–intimate partner rate | −0.13 | .08 | 0.22 | .003 | 0.20 | .008 |

| Younger Black female rate | −0.20 | .006 | 0.26 | <.001 | 0.28 | <.001 |

| Younger Hispanic female rate | 0.03 | .70 | 0.22 | .004 | 0.11 | .16 |

| Younger White female rate | −0.23 | .002 | 0.03 | 0.72 | 0.26 | .001 |

Mean (SD) [range] number of expansive policies in place across state-years is 9.53 (4.29) [3-20]; mean number of restrictive policies, 0.93 (0.87) [0-3]; and mean number of abortion barriers, 5.38 (2.57) [0-9].

Spearman correlation used to determine P values.

The number of abortion barriers was positively associated with 4 types of pregnancy-associated homicide (except younger Hispanic females). Three barriers were associated with all types of pregnancy-associated homicide except younger Hispanic females: restricted public funding, mandatory waiting periods, and parental involvement (eTable in Supplement 1).

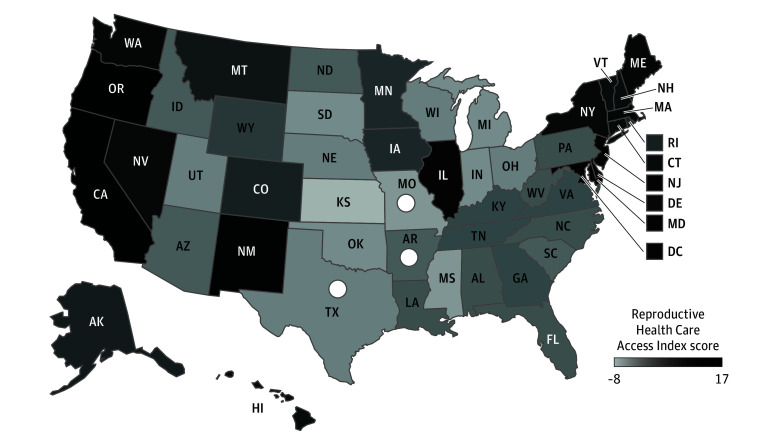

Table 2 and Table 3 suggest support for both hypotheses, but states that prohibit finalizing divorce during pregnancy tended to have less reproductive health care access (Figure). To address this correlation, negative binomial regressions were conducted that control for region, include fixed effects for year, and cluster robust SEs by state (Table 4).

Figure. Reproductive Health Care Access.

White circles identify states that prohibit finalizing divorce during pregnancy. The Reproductive Health Care Access Index ranges from −8 to 17; higher scores indicate greater access. For additional information, see the Reproductive Health Care Access subsection of the Methods section.

Table 4. Negative Binomial Regression of Pregnancy-Associated Homicide Rates, Barriers to Divorce, and Reproductive Health Carea.

| Variable | IRR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Intimate partner rate | ||

| Finalizing divorce prohibited | 2.11 (1.09-4.08) | .03 |

| Reproductive Health Care Access Index scoreb | 0.98 (0.95-1.01) | .19 |

| Southern US | 1.49 (0.93-2.39) | .10 |

| Non–intimate partner rate | ||

| Finalizing divorce prohibited | 0.93 (0.33-2.58) | .88 |

| Reproductive Health Care Access Index scoreb | 0.92 (0.87-0.98) | .01 |

| Southern US | 1.07 (0.48-2.38) | .87 |

| Younger Black female rate | ||

| Finalizing divorce prohibited | 2.00 (0.60-6.73) | .26 |

| Reproductive Health Care Access Index scoreb | 0.91 (0.87-0.96) | <.001 |

| Southern US | 2.17 (1.00-4.71) | .05 |

| Younger Hispanic female rate | ||

| Finalizing divorce prohibited | 1.07 (0.44-2.58) | .88 |

| Reproductive Health Care Access Index scoreb | 0.87 (0.79-0.96) | .007 |

| Southern US | 0.87 (0.29-2.58) | .80 |

| Younger White female rate | ||

| Finalizing divorce prohibited | 2.39 (1.12-5.09) | .02 |

| Reproductive Health Care Access Index scoreb | 0.95 (0.90-1.00) | .06 |

| Southern US | 3.04 (1.62-5.71) | .001 |

Abbreviation: IRR, incident risk ratio.

Total of 181 state-years. Robust SEs are clustered by state; fixed effects for year.

Information on this index is given in the Reproductive Health Care Access subsection of the Methods section.

When finalizing divorce while pregnant is prohibited, rates of IPH were significantly higher (IRR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.09-4.08; P = .03), as were rates for younger White females (IRR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.12-5.09; P = .02). Rates were not significant for any other racial and ethnic group.

Rates of non-IPH were lower in states with greater reproductive health care access (IRR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.87-0.98; P = .01). Reproductive health care access was negatively associated with homicide rates for younger Black females (IRR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.87-0.96; P < .001) and younger Hispanic females (IRR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.79-0.96; P = .007).

Discussion

Barriers to divorce while pregnant were associated with higher rates of pregnancy-associated IPH in the US (2018-2021). These results have policy implications for ensuring the safety of pregnant women and highlight the importance of domestic violence resources and safety planning for people leaving abusive marriages, especially in states with restrictive divorce laws. It is crucial that legal support and victim advocates, for instance, ensure pregnant women in abusive marriages secure protective orders and safe housing or other resources despite their inability to finalize divorce at that specific stage. As legislators push for changing divorce laws in Missouri, further research will be needed to see whether such changes decrease IPV and pregnancy-associated homicide.

More pregnant females are killed by an intimate partner than a nonpartner. Training could help health care professionals better identify and respond to signs of partner violence. Pregnant women experiencing abuse should be advised of their heightened risk of pregnancy-related complications and homicide, as well as the effects of violence on their child. Training for gynecologists, obstetricians, and other professionals who administer reproductive services could help them identify reproductive coercion and ensure access to contraceptive methods that are less resistant to sabotage by violent partners. Given that greater reproductive health care access is even more strongly associated with rates of pregnancy-associated homicide perpetrated by someone other than an intimate partner, however, this suggests a need to screen for dangerous contexts other than IPV that place women at risk for pregnancy-associated homicide. This is especially important for groups placed at the highest risk: younger Black and Hispanic girls and women.

Three abortion barriers were associated with higher homicide rates in 4 of the contexts studied, except younger Hispanic females. Rates were higher in state-years with waiting periods, ranging from 18 to 72 hours, suggesting this is a critical time in which medical and criminal justice intervention may be needed. Rates were also higher where parental consent/notification is required, which is of great concern, given it is estimated that approximately 18% of rape-related pregnancies are perpetrated by the female’s father, stepfather, or other family member.36 State-years that limit public funding of abortion to life endangerment, rape, or incest also had higher rates, suggesting younger pregnant girls and women who are placed at economic disadvantage are particularly vulnerable due to these restrictions.

While state-level effects were examined, understanding how reproductive health care access varies at the county level and across rural, suburban, and urban divides could reveal economic and geographic factors that facilitate access to care locally and in border states. Understanding reproductive health care resources at local levels could provide resources and points of contact to help ease access, identify signs of violence, and intervene to keep women and girls safe.

Limitations

This study has limitations. Similar to other datasets on violent deaths, the NVDRS has missing data on key variables, including high levels of missing data on pregnancy status.8 Pregnancies among women who experience violent deaths continue to be underreported on death certificates, even with pregnancy check boxes added to these documents in 2003.37 Other NVDRS sources may also lack this information depending on the timing of the pregnancy in relation to the woman’s death and whether she had confided in others about the pregnancy. Furthermore, pregnancy-associated homicide rates cannot be calculated for some states due to small numbers, resulting in unstable rates, and data were not available for all states for all years.

Conclusions

Laws passed by state legislatures can provide protections or create harms to pregnant women. The findings of this cross-sectional study suggest that homicide rates among pregnant and recently pregnant women vary significantly across state-years in accordance with access to divorce and reproductive health care. The inability to finalize a divorce was associated with higher rates of pregnancy-associated IPH, and greater reproductive health care access was associated with lower homicide rates for those killed by someone other than an intimate partner. Reproductive health care access was also associated with lower pregnancy-associated homicide rates among the 2 groups studied at greatest risk: younger Black and Hispanic girls and women.

eTable. Specific Barriers to Abortion and Crude Rates of Pregnancy-Associated Homicide per 100 000 Females of Reproductive Age

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Wallace M, Gillispie-Bell V, Cruz K, Davis K, Vilda D. Homicide during pregnancy and the postpartum period in the United States, 2018-2019. Obstet Gynecol. 2021;138(5):762-769. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallace ME. Trends in pregnancy-associated homicide, United States, 2020. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(9):1333-1336. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell J, Matoff-Stepp S, Velez ML, Cox HH, Laughon K. Pregnancy-associated deaths from homicide, suicide and drug overdose: review of research and the intersection with intimate partner violence. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(2):236-244. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cliffe C, Miele M, Reid S. Homicide in pregnant and postpartum women worldwide: a review of the literature. J Public Health Policy. 2019;40(2):180-216. doi: 10.1057/s41271-018-0150-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang J, Berg CJ, Saltzman LE, Herndon J. Homicide: a leading cause of injury deaths among pregnant and postpartum women in the United States, 1991-1999. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(3):471-477. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.029868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng D, Horon IL. Intimate-partner homicide among pregnant and postpartum women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(6):1181-1186. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181de0194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitchell C, Lawton E, Morton C, McCain C, Holtby S, Main E. California pregnancy-associated mortality review: mixed methods approach for improved case identification, cause of death analyses and translation of findings. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(3):518-526. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1267-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, Flynn H, Gold KJ. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1056-1063. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823294da [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kivisto AJ, Mills S, Elwood LS. Racial disparities in pregnancy-associated intimate partner homicide. J Interpers Violence. 2022;37(13-14):NP10938-NP10961. doi: 10.1177/0886260521990831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miller JM, Rensing S. Integrating National Violent Death Reporting System data into maternal mortality review committees. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2021;30(11):1573-1579. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2021.0058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Modest AM, Prater LC, Joseph NT. Pregnancy-associated homicide and suicide: an analysis of the National Violent Death Reporting System, 2008-2019. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(4):565-573. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugan L, Nagin DS, Rosenfeld R. Explaining the decline in intimate partner homicide: the effects of changing domesticity, women’s status, and domestic violence resources. Homicide Stud. 1999;3:187-214. doi: 10.1177/1088767999003003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reckdenwald A, Parker KF. Understanding the change in male and female intimate partner homicide over time: a policy- and theory-relevant investigation. Fem Criminol. 2012;7:167-195. doi: 10.1177/1557085111428445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gerson J. Abortion bans and divorce restrictions can be a dangerous combination for pregnant people. The 19th. Published April 11, 2024. Accessed August 27, 2024. https://19thnews.org/2024/04/states-abortion-bans-divorce-restrictions-domestic-violence/

- 15.Riddle K. Pregnant women in Missouri can’t get divorced: critics say it fuels domestic violence. NPR. Published May 3, 2024. Accessed May 3, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2024/05/03/1247838036/divorce-pregnant-women-missouri-abortion-marriage-abuse

- 16.Trela N. Missouri, Texas, Arkansas bar finalizing divorce while pregnant: fact check. USA Today. Published February 28, 2024. Accessed March 4, 2024. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/factcheck/2024/02/28/pregnant-women-divorce-missouri-texas-arkansas-arizona/72763848007/

- 17.Gazmararian JA, Adams MM, Saltzman LE, et al. ; The PRAMS Working Group . The relationship between pregnancy intendedness and physical violence in mothers of newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(6):1031-1038. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00057-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodwin MM, Gazmararian JA, Johnson CH, Gilbert BC, Saltzman LE. Pregnancy intendedness and physical abuse around the time of pregnancy: findings from the pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 1996-1997: PRAMS Working Group, Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4(2):85-92. doi: 10.1023/A:1009566103493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore AM, Frohwirth L, Miller E. Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(11):1737-1744. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316-322. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samankasikorn W, Alhusen J, Yan G, Schminkey DL, Bullock L. Relationships of reproductive coercion and intimate partner violence to unintended pregnancy. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2019;48(1):50-58. doi: 10.1016/j.jogn.2018.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith EJ, Bailey BA, Cascio A. Sexual coercion, intimate partner violence, and homicide: a scoping literature review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2024;25(1):341-353. doi: 10.1177/15248380221150474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maxwell L, Devries K, Zionts D, Alhusen JL, Campbell J. Estimating the effect of intimate partner violence on women’s use of contraception: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(2):e0118234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basile KC, Smith SG, Liu Y, et al. Rape-related pregnancy and association with reproductive coercion in the US. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55(6):770-776. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.07.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chambliss LR. Intimate partner violence and its implication for pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;51(2):385-397. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31816f29ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn LL, Oths KS. Prenatal predictors of intimate partner abuse. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2004;33(1):54-63. doi: 10.1177/0884217503261080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guttmacher Institute . State bans on abortion throughout pregnancy. Updated July 29, 2024. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/state-policies-abortion-bans

- 28.Guttmacher Institute . An overview of abortion laws. August 31, 2023. Accessed April 10, 2024. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/overview-abortion-laws

- 29.Roberts SC, Biggs MA, Chibber KS, Gould H, Rocca CH, Foster DG. Risk of violence from the man involved in the pregnancy after receiving or being denied an abortion. BMC Med. 2014;12:144-150. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0144-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Addante AN, Eisenberg DL, Valentine MC, Leonard J, Maddox KEJ, Hoofnagle MH. The association between state-level abortion restrictions and maternal mortality in the United States, 1995-2017. Contraception. 2021;104(5):496-501. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burdick KJ, Coughlin CG, D’Ambrosi GR, et al. Abortion restrictiveness and infant mortality: an ecologic study, 2014-2018. Am J Prev Med. 2024;66(3):418-426. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2023.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wallace ME, Stoecker C, Sauter S, Vilda D. States’ abortion laws associated with intimate partner violence-related homicide of women and girls in the US, 2014-20. Health Aff (Millwood). 2024;43(5):682-690. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2023.01098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keegan G, Hoofnagle M, Chor J, et al. State-level analysis of intimate partner violence, abortion access, and peripartum homicide: calls for screening and violence interventions for pregnant patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2024;238(5):880-888. doi: 10.1097/XCS.0000000000001019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . National Violent Death Reporting System. Updated May 16, 2024. Accessed September 5, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/nvdrs/about/index.html

- 35.Rice WS, Redd SK, Luke AA, Komro K, Jacob Arriola K, Hall KS. Dispersion of contraceptive access policies across the United States from 2006 to 2021. Prev Med Rep. 2022;27:101827. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holmes MM, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Best CL. Rape-related pregnancy: estimates and descriptive characteristics from a national sample of women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175(2):320-324. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(96)70141-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horon IL, Cheng D. Effectiveness of pregnancy check boxes on death certificates in identifying pregnancy-associated mortality. Public Health Rep. 2011;126(2):195-200. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Specific Barriers to Abortion and Crude Rates of Pregnancy-Associated Homicide per 100 000 Females of Reproductive Age

Data Sharing Statement