Abstract

Background

Breast cancer seriously affects physical and mental health of women. Despite advances in the clinical use of different treatments, breast cancer remains a major cause of mortality. Therefore, it is imperative to identify promising treatment options. In the present study, we investigated the effects of shikonin on 4T1 breast cancer cells and its potential mechanisms of action.

Methods

BALB/c-derived mouse breast cancer 4T1 is very close to human breast cancer in growth characteristics and systemic response, so 4T1 cells were selected for further experiments. Cell viability, apoptosis, intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS), mitochondrial activity, and cellular calreticulin (CRT) exposure were assessed to evaluate the antitumor effects and mechanisms of shikonin in vitro. Orthotopic tumor growth inhibition and splenic immune cell regulation by shikonin were evaluated in 4T1 breast cancer orthotopic mice in vivo.

Results

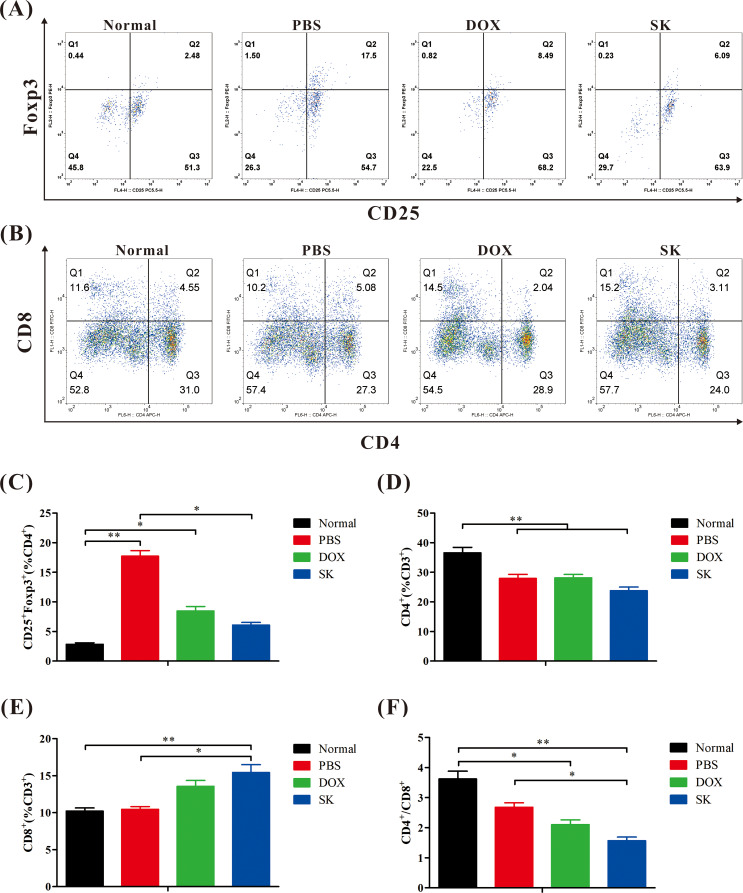

In vitro, shikonin could inhibit cell proliferation, cause apoptosis, disrupt mitochondrial activity, and induce ROS production and CRT exposure. In vivo, shikonin inhibited tumor growth, increased the proportion of CD8+ T cells, and reduced the proportion of regulatory cells (CD25+ Foxp3+ T cells) in the spleen.

Conclusions

Shikonin inhibits the growth of 4T1 breast cancer cells by disrupting mitochondrial activity, promoting oxidative stress, and regulating immune function.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12906-024-04671-3.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Shikonin, Intracellular reactive oxygen species, Mitochondrial activity, Immunomodulation

Introduction

According to the latest data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization, breast cancer has become the malignant tumor with the highest incidence globally [1]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is a subtype of breast cancer that features the negative expression of estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). TNBC accounts for 10–15% of all breast cancer cases and is characterized by strong aggressiveness, easy recurrence and metastasis, and poor prognosis [2]. The unique biological behavior, TNBC makes the cells fail to respond to endocrine and traditional anti-HER2 targeted therapies. The current treatment options for TNBC are limited to surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy. Unfortunately, some patients are already inoperable at the time of diagnosis [3]. Chemotherapy is the main form of systemic therapy for TNBC. Chemotherapeutic drugs include taxanes, anthracyclines, cyclophosphamide, platinum agents, and fluorouracil [4]. These drugs do not produce a satisfactory therapeutic effect and have problems with drug resistance and toxic side effects [3–5]. Whether TNBC is sensitive to radiotherapy remains inconclusive, however, susceptibility to recurrence suggests the presence of radiotherapy resistance [6]. The development of additional treatments for TNBC is necessary, and candidate treatments are being validated and explored. In recent years, new treatment strategies for breast cancer have emerged, such as targeting the tumor microenvironment and immune response [7, 8].

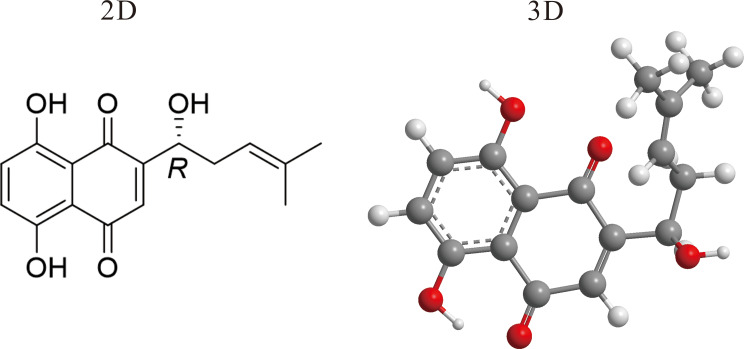

An increasing number of recent studies have documented the advantages of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) in the treatment of cancer, including TNBC, targeting multiple regulatory pathways [9–13]. Therefore, it is important to verify the efficacy and mechanisms of action of TCM in the treatment of TNBC. Shikonin (Fig. 1), is a small-molecule naphthoquinone compound extracted from the roots of Chinese herbal medicine Zicao (Lithospermum erythrorhizon Sieb. et Zucc). Relevant information concerning Zicao is presented in Table 1. Shikonin is active against thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer, and has immunomodulatory, and other effects [14, 15]. Shikonin exerts anti-tumor effects on various types of tumors through various of mechanisms [14–20]. In one clinical trial, a shikonin mixture inhibited the growth of lung cancer and improved the immune function in participants [21]. Shikonin can increase reactive oxygen species (ROS) in gastric cancer cells and eventually triggers mitochondria-mediated apoptosis [22]. In human colon cancer, shikonin has cytotoxic effects on tumors by inducing apoptotic cell death via the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria-mediated pathways [23]. However, the effects and mechanisms of action of shikonin on breast cancer are still being explored, with relatively few relevant reports published. More in-depth research is needed.

Fig. 1.

Two-dimensional (2D) and 3D chemical structures of shikonin

Table 1.

Zicao

| Latin scientific name | Plant part | English name | Pinyin name |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithospermum erythrorhizon Sieb. et Zucc. | Root | Radix Arnebiae Seu Lithospermi | Zicao |

The mouse 4T1 breast cancer model is often used in pharmacological breast cancer research as it can fairly accurately mimic the characteristics of human breast cancer, including TNBC, including the local tumor growth pattern and the systemic response [24–26]. In this study, 4T1 breast cancer cells were used in vitro and in vivo in the mouse model to explore the inhibitory effect of shikonin on breast cancer and its possible mechanisms, and to elaborate its value in the treatment of breast cancer.

Methods

Cell culture

4T1 cells purchased from Procell Life Science&Technology Co.,Ltd.(China) were maintained in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) 1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 air.

Cell viability assay

4T1 cell viability was detected by the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yi(2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. Each well of 96-well plates was seeded with 5 × 103 cells and incubated overnight. The cells were then exposed to a series of concentrations of shikonin (Desite, China) ranging from 10 to 0.039 µg/mL. After 48 h of treatment, 20 µL of MTT reagent (Solarbio, China) at a concentration of 5 mg/mL was added to each well. After incubation at 37 °C for 4 h, the supernatant was removed. The insoluble formazan that had been formed by viable cells was resuspended in 150 µL dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Yuanye, China) and the absorbance was determined using a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The experiment on the effect of shikonin on non-cancerous cells was included in the supporting information.

For in vitro experiments, shikonin was dissolved in DMSO to produce a stock solution of 10 mg/mL, which was diluted as required in cell culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Cell apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was detected by flow cytometry. Each well of six-well plates was seeded with 2 × 105 cells and incubated overnight. The cells were then treated with 200 ng/mL shikonin (low-dose shikonin group, LD-SK group) or 800 ng/mL shikonin (high-dose shikonin group, HD-SK group). Cells in the negative control group were treated with PBS (Procell, China; PBS group). Cells in the positive control group were treated with 400 ng/mL doxorubicin hydrochloride (Meilunbio, China; DOX group). After 48 h of treatment, the cells were collected and stained with Annexin V-Cy5 (BioVison, USA) and 4’,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride (DAPI; Meilunbio, China) at 4℃ for 30 min, followed by flow cytometry analysis (Beckman Coulter, USA).

ROS assay

Intracellular ROS levels were measured by flow cytometry. Cells at logarithmic growth stage were inoculated (3 × 105 cells) in wells of six-well plates and incubated for 24 h. The cells were then treated to yield the aforementioned PBS, DOX, LD-SK, and HD-SK group. After 24 h of treatment, the ROS fluorescent probe dihydrorhodamine 123 (Meilunbio, China) was added and then incubated at 37℃ for a further 4 h in the dark. After incubation, elution with PBS was performed three times, and fluorescence intensity was detected by flow cytometry.

Mitochondrial activity assay

The mitochondrial activity was detected using flow cytometry. Each well of six-well plates was seeded with 2 × 105 cells and incubated for 24 h. The cells were then treated to establish the aforementioned PBS, DOX, LD-SK, and HD-SK groups. After 48 h of treatment, the cells were collected and stained with JC-10 cationic and lipophilic dye (BIOBYING, China) at 37℃ for 2 h. After staining, cells were washed and resuspended in PBS. Mitochondrial activity was detected by flow cytometry.

Calreticulin (CRT) exposure assay

CRT exposure was quantified by flow cytometry. Cells at the logarithmic growth stage were inoculated (2 × 105 cells) in wells of six-well plates and incubated for 24 h. The cells were then treated to establish the aforementioned PBS, DOX, LD-SK, and HD-SK groups. After 48 h of treatment, the cells were collected and incubated with the CALR Polyclonal Antibody (Elabscience, China) at 37℃ for 1 h. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated with goat Anti-Rabbit IgG H&L/Cy5 (Bioss, China) at 37 °C in the dark for 1 h, washed, and resuspended in PBS. Flow cytometry was used for the quantitative assay of CRT exposure of 4T1 cells.

In vivo antitumor activity

Twenty-four specific pathogen-free healthy female BALB/c mice (6–8 weeks old, 16–20 g in weight) were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (License Number: SYXK (Yue) 2018-0034). The mice were raised in a temperature-and humidity-controlled pathogen-free room under a 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water. All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Sci-tech Industrial Park, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (serial number: PZ22069).

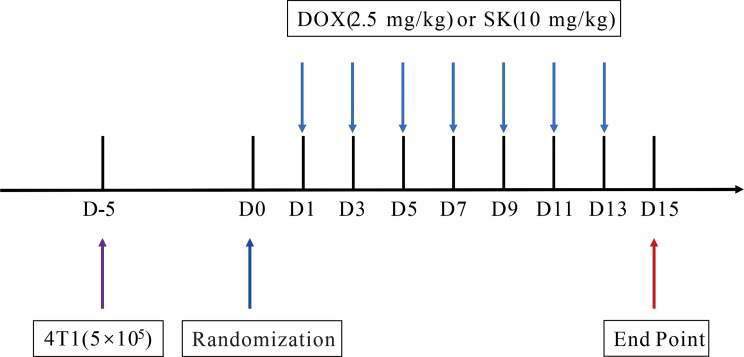

After being anesthetized by isoflurane (Ruiwode, China) inhalation (1.5% in air), the mammary fat pads of 18 mice were injected with 4T1 cells (5 × 105 cells in 50 µL PBS per mouse) using sterile insulin syringe (Kindly, China). Animals were randomized (n = 6) and then received intravenous injection of shikonin (10 mg/kg, dissolved in PBS containing 1% DMSO and 3% Tween 80), DOX (2.5 mg/kg, dissolved in PBS), or an equal volume of PBS every other day for 14 days (Fig. 2). The tumor volume of mice were measured every other day (tumor volume = length×1/2 width2). Animals were euthanized by isoflurane inhalation (3% in air) and cervical dislocation after treatment. The tumor tissues and spleens were collected.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of in vivo experimental procedure

Spleen immune cells detection

Spleen immune cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Spleens were washed with pre-cooled PBS, ground, and passed through a 200 sieve to purify the spleen grinding liquid. The collected cell suspension was centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. After removing the supernatant, 1 mL of diluted modified red blood cell lysis buffer (Meilunbio, China) was added to the cell precipitate and the cells were lysed at room temperature for 10 min. When a white flocculent precipitate was visible to the naked eye, 1 mL of PBS was added to terminate lysis, and each sample was centrifuged after filtering. The precipitate was resuspended with PBS to form a single cell suspension of spleen cells. The spleen single cell suspension was divided into two equal portions. One portion was incubated with Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Anti-Mouse CD45 Antibody[30-F11] (Elabscience, China), Elab Fluor® Red 780 Anti-Mouse CD3 Antibody[17A2] (Elabscience), APC Anti-Mouse CD4 Antibody[GK1.5] (Elabscience, China) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) Anti-Mouse CD8a Antibody[53 − 6.7] (Elabscience) diluted in cell staining buffer (Elabscience, China) at 4 °C in the dark for 30 min. The other portion was incubated with Elab Fluor® Violet 450 Anti-Mouse CD45 Antibody[30-F11], Elab Fluor® Red 780 Anti-Mouse CD3 Antibody[17A2], APC Anti-Mouse CD4 Antibody[GK1.5], and PerCP/Cyanine5.5 Anti-Mouse CD25 Antibody[PC-61.5.3] (Elabscience, China) diluted in cell staining buffer at 4 °C in the dark for 30 min. Fixed membrane breaking and nucleation breaking solutions (Biolegend, USA) were used to disrupt cell membranes and nuclei, respectively, according to the specifications to facilitate staining with phycoerythrin (PE) Anti-Mouse Foxp3 Antibody [3G3] (Elabscience, China). Finally, flow cytometry was used to examine the samples, and FlowJo _V10 software was used for data analysis.

Statistical analysis

SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM, USA) was used for the statistical analysis of data. Data are presented as mean ± standard error. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for the measurement of multiple groups conforming to a normal distribution and homogeneity of variance. Welch’s ANOVA was used for the measurement data of multiple groups that conformed to a normal distribution but did not conform to homogeneity of variance. Kruskal-Wallis test was used for the measurement data of multiple groups that did not conform to a normal distribution. The test level of the above statistical results used P < 0.05 as the standard of significant difference and P < 0.01 as the standard of very significant difference.

Results

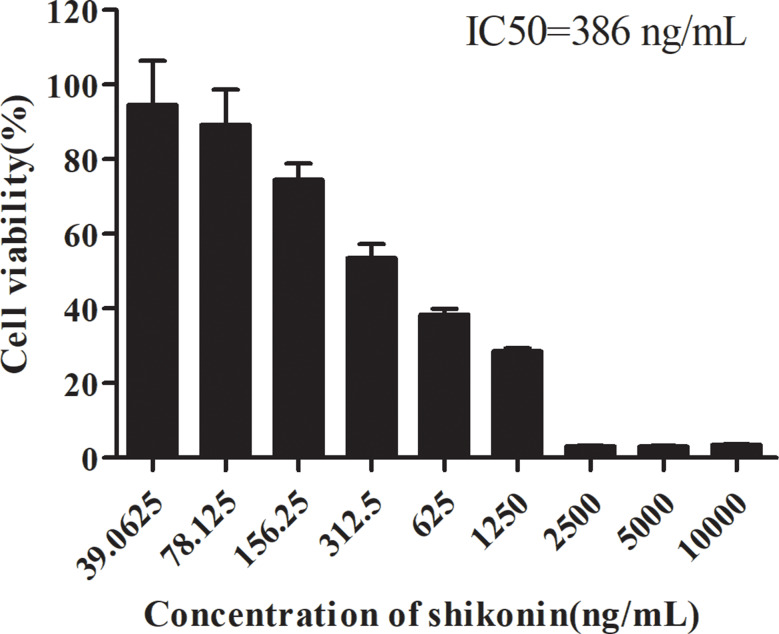

Cytotoxic effect of shikonin on 4T1 cells

The cytotoxicity of shikonin was detected by the MTT assay. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) value was calculated based on the percentage of cell viability inhibition. Shikonin strongly inhibited 4T1 cell viability, with an IC50 value of 386 ng/mL following a 48-h treatment (Fig. 3). The finding suggested that shikonin could inhibit the proliferation of 4T1 breast cancer cells in vitro.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effect of shikonin treatment for 48 h on 4T1 cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6)

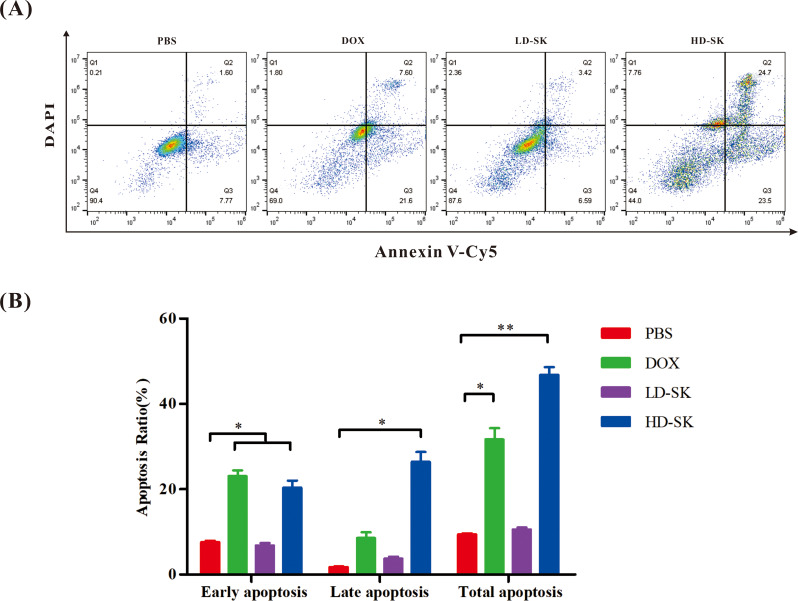

Effect of shikonin on apoptosis of 4T1 cells

To further evaluate whether the cytotoxicity of shikonin was related to apoptosis, flow cytometry was used to measure the apoptosis rate. Similar to DOX, treatment with 800 ng/mL shikonin promoted the early and late apoptosis of 4T1 cells (Fig. 4). These findings demonstrate that the cytotoxicity of shikonin is related to apoptosis.

Fig. 4.

Shikonin promotes apoptosis of 4T1 cells. (A) Representative scatter plots of the apoptotic status in 4T1 cells in the 48-h PBS, DOX, LD-SK and HD-SK groups. (B) Statistical analysis of apoptosis of 4T1 cells (percentage of cells in Q2 and Q3) after the different treatments. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

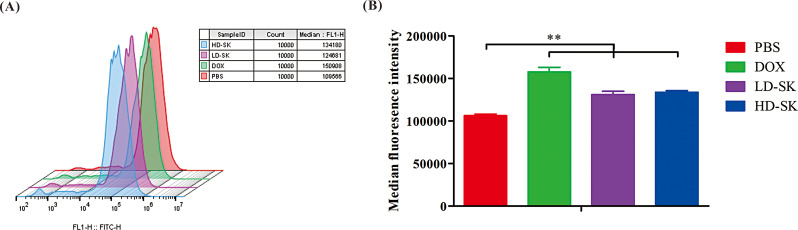

Effect of shikonin on ROS levels of 4T1 cells

Flow cytometry was used to detect the effects of the drugs on ROS levels in 4T1 cells. Both shikonin and DOX increased ROS levels in tumor cells (Fig. 5). These results suggest that, similar to DOX, shikonin may kill tumor cells by inducing increased production of ROS.

Fig. 5.

Shikonin induces excessive production of ROS by 4T1 cells. (A) Flow cytometry detection of induced production of ROS in the PBS, DOX, LD-SK and HD-SK groups after 24 h. (B) Statistical analysis of ROS level in 4T1 cells after the different treatments. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3); **P < 0.01

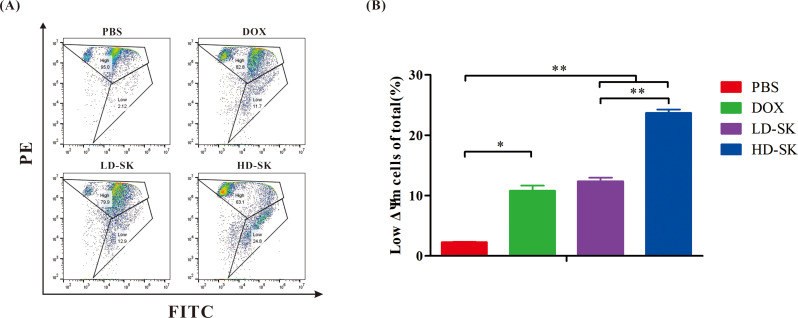

Effect of shikonin on mitochondrial membrane potential of 4T1 cells

The effect of shikonin on the mitochondrial membrane potential of 4T1 cells was analyzed using JC-10 staining. JC-10 is a fluorescent probe of mitochondrial membrane potential that can selectively accumulate in the mitochondrial matrix to form a reversible red fluorescent polymer in normal cells. Owing to the decrease or loss of the membrane potential of unhealthy mitochondria, JC-10 can be transformed from a polymer to a monomer form and exists in the cytoplasm, producing green fluorescence. As shown in Fig. 6, a change from red to green fluorescence was observed in all drug treatment groups, and the positive rate of mitochondrial membrane potential dissipation increased with an increase in shikonin concentration. These data suggest that shikonin, similar to doxorubicin hydrochloride, attacks the mitochondria of 4T1 cells and disrupts their function.

Fig. 6.

Shikonin disrupts the mitochondrial function of 4T1 cells. (A) Representative scatter plots of the mitochondrial membrane potential status in 4T1 cells treated with PBS, 400 ng/mL doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX), 200 ng/mL shikonin, and 800 ng/mL shikonin for 48 h. (B) Statistical analysis of percentage of cells with low mitochondrial membrane potential. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3); *P values < 0.05, **P < 0.01

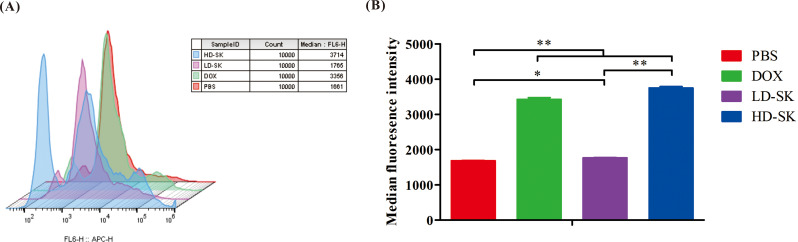

Effect of shikonin on CRT exposure of 4T1 cells

When tumor cells die due to external stimulation, the non-immunogenic to immunogenic transformation, and mediation of an antitumor immune response is termed immunogenic cell death (ICD). When ICD occurs in tumor cells, a series of signaling molecules are generated. These damage-associated molecular patterns include CRT exposed on the cell surface. Flow cytometry was used to detect the effects of the drugs on CRT exposure in 4T1 cells. Similar to DOX, shikonin induced CRT exposure in 4T1 cells (Fig. 7). The findings indicated the potential of shikonin to induce ICD (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Shikonin induces CRT exposure of 4T1 cells. (A) Flow cytometry detection of induced CRT exposure of 4T1 cells in the PBS, DOX, LD-SK, and HD-SK groups at 48 h. (B) Statistical analysis of CRT exposure of 4T1 cells after the different treatments. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 3); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

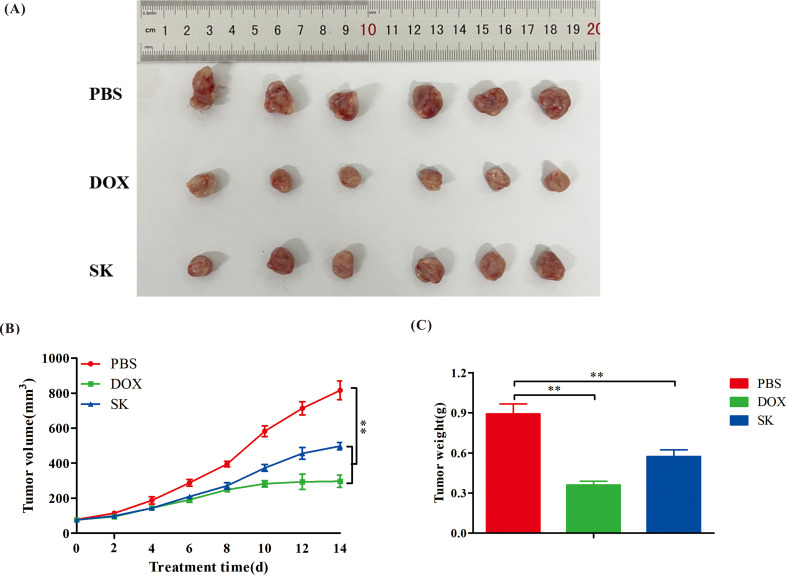

In vivo antitumor activity of shikonin

To better evaluate the antitumor effects of shikonin in vivo, a mouse 4T1 orthotopic transplantation tumor model was used. As shown in Fig. 8, the solid tumor volume in the PBS group gradually increased over time. The tumor volume (Fig. 8B) and weight (Fig. 8C) of mice in the DOX and SK groups were significantly lower than those in the PBS group after treatment, suggesting that shikonin could inhibit the growth of 4T1 breast cancer in mice. Although the tumor inhibitory effect was not as strong as that of DOX, the anti-breast tumor effect of shikonin warrants further study.

Fig. 8.

Antitumor effects of shikonin in vivo. (A) Anatomic morphology of tumors. (B) Tumor growth curve during the experimental period. (C) Tumor weight at the end of experiment. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6); **P values < 0.01

Effects of shikonin on spleen immune cells in vivo

To better evaluate the antitumor mechanism of shikonin, splenic immune cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 9, the proportion of CD25+Foxp3+-positive T cells in the spleens of PBS-treated mice with breast cancer was higher than that in the normal group, suggesting immunosuppression. Similar to DOX, shikonin reduced the proportion of CD25+Foxp3+ T cells in mice with breast cancer, thereby alleviating immunosuppression. In addition, although shikonin had no significant effect on CD4+ T cells, it increased the proportion of CD8+ T cells in mice with breast cancer compared to that in the normal group. The finding is conducive to antitumor effects, as CD8+ T cells are a subgroup of T lymphocytes that can directly kill tumor cells. Shikonin also reduced the proportions of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which was mainly associated with an increased proportion of CD8+ positive T cells. The findings indicate that, in general, shikonin plays an immunomodulatory role by alleviating immunosuppression and enhancing antitumor immunity, which may be an important antitumor mechanism.

Fig. 9.

Shikonin regulates immunity in vivo. (A and B) Representative scatter plots of spleen CD25+Foxp3+ positive T cells (A) and CD8+ positive T cells (B). (C and D) Statistical analysis of percentage of CD25+Foxp3+ positive T cells (C) and CD4+ positive T cells (D). (E) Statistical analysis of CD8+ positive T cells percentage. (F) Statistical analysis of the ratio of CD4+ and CD8+ positive T cells. Data are presented as mean ± SEM (n = 6); *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01

Discussion

Progress has been made in the non-surgical treatment of breast cancer in recent years. However, breast cancer, especially TNBC, remains one of the main malignant tumors that endangers the health of women. The pathogenesis of breast cancer is complex, and improved methods of treatment are needed [27]. TCM has the advantage of having multiple tumor targets, such as direct and indirectly killing of tumor cells by regulating the body’s immunity [9]. Shikonin is an important active component of Lithospermum erythrorhizon Sieb. et Zucc, with a strong inhibitory effect on a variety of cancers through multiple antitumor mechanisms [14–20, 28–31]. For example, hypoxia is a potential therapeutic target in breast cancer, potential hypoxia-regulated axis was associated with tumor development and progression [32]. Shikonin down-regulated expression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α to inhibit tumor growth [33].

DOX is a chemotherapeutic drug commonly used in clinical breast cancer treatments, including TNBC [4, 34, 35]. The antitumor activity of DOX involves induction of apoptosis, ROS production, and ICD [36, 37]. DOX treatment was the positive control group to further clarify the anti-breast cancer effect and mechanisms of shikonin. Shikonin reportedly has an unfavorable oral bioavailability with a plasma protein binding rate of 64.6% [38]. To observe the effect of shikonin on tumors in vivo, shikonin was injected intravenously in tumor-bearing mice. In a Sprague-Dawley rat model, the t1/2β detected after intravenous injection of shikonin at a dose of 5 mg/kg was 630.7 ± 124.9 min [39]. However, in the present study, considering the tolerance of the mice to tail vein injection, we administered the drug via tail vein injection every other day. If shikonin is administered according to its’ pharmacokinetics, it should achieve a better therapeutic effect. Improving the pharmacokinetics of shikonin by optimizing the dosage to reduce the frequency of administration may overcome this limitation. This, requires further research.

The IC50 of shikonin on 4T1 cells was 386 ng/mL. Thus, we selected doses of 800 ng/mL (HD-SK group) and 200 ng/mL (LD-SK group) for the subsequent in vitro experiments. These doses were approximately 0.5 and 2 times the IC50, respectively. The in vitro experimental results showed that shikonin inhibited the proliferation of 4T1 breast cancer cells, this is consistent with the results of in vitro study by Chen et al., who also found that shikonin inhibits the growth of human breast cancer cells MDA-MB-231 and MCF-12 A [40]. Similar to DOX, shikonin induced the apoptosis of 4T1 breast cancer cells, disrupted mitochondrial activity, increased ROS levels in tumor cells, and induced CRT exposure. Mitochondrial inhibition is a treatment strategy for cancer [41]. The antitumor activity of shikonin involves disrupted mitochondrial activity in 4T1 breast cancer cells. Previous studies have reported that ROS generated from shikonin has a significant influence on multiple signaling pathways, ultimately killing tumor cells, which is an indirect interaction mode in which ROS is a key mediator [15, 16]. Therefore, we measured the ROS levels before detecting the other indicators. When the intracellular ROS content exceeds a certain threshold, it causes the destruction of protein and DNA structures and the breakdown of the mitochondrial membrane potential, leading to the death of tumor cells [15, 42]. Intracellular ROS storms can also cause ICD, and increased exposure to CRT on the surface of tumor cells is an important sign of immunogenic death [43]. Increasing the ROS content at tumor sites has become an effective cancer treatment method, and we found that increasing the ROS content in tumor cells is one of the anti-breast cancer mechanisms of shikonin.

Although the current in vivo study results suggest that shikonin is less effective than the positive control drug DOX, it does have an anti-breast cancer effect, so it may be used as an adjuvant in the future, or it may be an additional choice for patients with DOX resistance. Immunotherapy has recently emerged as a therapeutic strategy. This approach, which modulates the immune system to kill tumor cells, has been applied to treat TNBC [7]. Compared to other breast cancers, TNBC has unique molecular characteristics that include a high tumor mutation load and large number of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, which are amenable for immunotherapy [44]. Advancements in TNBC immunotherapy have included combination therapy, such as chemotherapy combination regimens (such as atezolizumab + nab-paclitaxel) and targeted therapy combination regimens (such as niraparib + pembrolizumab). Monotherapy remains limited, necessitating further explorations of novel immunotherapy agents [44]. Regulatory T cells (Tregs) are an immunosuppressive subgroup of CD4+T cells (CD25+Foxp3+). When used for tumor immunotherapy, Tregs impair both the immune surveillance of cancer in healthy individuals and the antitumor immune response in tumor-bearing hosts [45, 46]. Equipped with highly immunosuppressive activity, Tregs, have been shown to suppress the viability and function of CD8+ T cells and promote tumor progression [47]. Increased Treg infiltration has been described in TNBC tissue compared to the infiltration in normal breast tissue [48]. It has been reported that the anti-TNBC effect involves inhibition of Treg activity and increased CD8+ T cell responses [49]. In vivo experimental results of this study showed that shikonin had antiproliferative effects on 4T1 breast cancer cells. An increase in the proportion of Tregs in splenic immune cells was observed in a 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mouse model, an immunosuppressive state conducive to tumor growth. Similar to DOX, shikonin can downregulate the proportion of Tregs in the spleen immune cells of the 4T1 breast cancer BALB/c mouse model, relieve the splenic immunosuppressive state of tumor-bearing mice, and facilitate the activation of the peripheral antitumor immune response. In addition, shikonin significantly increased the proportion of CD8+T cells in the spleens of tumor-bearing mice, as CD8+T cells play an important role in the antitumor immune response [50].

As shown in Figure S1, the IC50 value of shikonin on MLE-12 is approximately 10 times higher than that on 4T1 cells, which suggested that the toxicity of shikonin to 4T1 tumor cells is much greater than that to normal cells. But like many chemotherapy drugs, shikonin may have potential toxicity to normal cells, which requires further research to determine whether the anti-tumor effects of shikonin outweigh its drawbacks.

Conclusions

Shikonin can inhibit the growth of 4T1 breast cancer cells through multiple mechanisms, including disruption of mitochondrial activity, promotion of oxidative stress, and relief of immune suppression. This study explored the anti-breast cancer effect and its mechanisms. Subsequent research will determine the optimal dosage and toxic side effects of shikonin in vivo for anti-tumor treatment.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

Jianming Liang designed the project and supervised its implementation. Chuyi Yu, Haoyu Xing, Xiaguo Fu, Yingying Zhang, Xiufang Yan, Jianjia Feng, Zhouqin He, Li Ru and Chunlong Huang completed all experiments. Chuyi Yu wrote the manuscript and Chunlong Huang, Jianming Liang revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2022A1515011312), the Special Projects in Key Areas of Colleges and Universities in Guangdong Province (2022ZDZX2015).

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of Sci-tech Industrial Park, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicinee (Serial number: PZ22069) and carried out in accordance with the national rules, regulations of laboratory animal ethics and ARRIVE guidelines.

Consent for publication

All authors consent for the publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chunlong Huang, Email: tommyhuang1988@foxmail.com.

Jianming Liang, Email: liangjianming@gzucm.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries [J]. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dass SA, Tan KL, Rajan RS et al. Triple Negative Breast Cancer: A Review of Present and Future Diagnostic Modalities[J]. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 2021, 57(1):62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Li Y, Zhang H, Merkher Y, et al. Recent advances in therapeutic strategies for triple-negative breast cancer[J]. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15(1):121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yin L, Duan JJ, Bian XW, et al. Triple-negative breast cancer molecular subtyping and treatment progress[J]. Breast Cancer Res. 2020;22(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nath A, Mitra S, Mistry T, et al. Molecular targets and therapeutics in chemoresistance of triple-negative breast cancer[J]. Med Onco. 2021;39(1):14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.He MY, Chloé, Rancoule A, Rehailia-Blanchard et al. Radiotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer: Current situation and upcoming strategies[J]. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 2018, 131: 96–101. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Liu Y, Hu Y, Xue J, et al. Advances in immunotherapy for triple-negative breast cancer[J]. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Domínguez-Cejudo MA, Gil-Torralvo A, Cejuela M, et al. Targeting the Tumor Microenvironment in breast Cancer: prognostic and predictive significance and Therapeutic opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(23):16771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiang Y, Guo Z, Zhu P, et al. Traditional Chinese medicine as a cancer treatment: modern perspectives of ancient but advanced science[J]. Cancer Med. 2019;8(5):1958–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho VW, Tan HY, Guo W, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Chinese Herbal Medicine on treatment of breast Cancer: a Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials[J]. Am J Chin Med. 2021;49(7):1557–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang LN, Wu ZL, Yang ZJ, et al. Exploring mechanism of Key Chinese Herbal Medicine on breast Cancer by Data Mining and Network Pharmacology Methods[J]. Chin J Integr Med. 2021;27(12):919–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao XY, Xu JY, Wang ZL, et al. Research progress on regulation of immune microenvironment of breast cancer by traditional Chinese medicine[J]. Microenviron Microecol Res. 2022;4(1):9–13.

- 13.Yang Z, Zhang Q, Yu L, et al. The signaling pathways and targets of traditional Chinese medicine and natural medicine in triple-negative breast cancer[J]. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;264:113249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia XU, Chun-Lian WU. The research Progress of Shikonin Pharmacological Effect[J]. Pharm Biotechnol. 2015;22(1):87–90.

- 15.Zhang X, Cui JH, Meng QQ, et al. Advance in anti-tumor mechanisms of Shikonin, Alkannin and their derivatives[J]. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2018;18(2):164–72. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Wang X, Yang MK, Han HW, et al. Shikonins as natural products from traditional Chinese medicinal plants: their biosynthesis, genetic regulation, structural modifications, and pharmaceutical functions (in Chinese)[J]. Sci Sin Vitae. 2022;52:347–72. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Q, Wang J, Wang J, et al. Molecular mechanism of shikonin inhibiting tumor growth and potential application in cancer treatment[J]. Toxicol Res. 2021;10(6):1077–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Feng W, Jianwen MA, Rao M. Effect and mechanism of Shikonin-Induced Necroptosis in Ovarian Cancer SKOV3 and A2780 Cells[J]. China Pharmaceuticals. 2019;28(1):5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma J, Feng W, Zhang L, et al. Mechanisms of Shikonin Inducing apoptosis in human non-small cell Lung Cancer A549 cells by promoting ROS Production[J]. J Med Res. 2018;47(12):7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang Z. Effects of Shikonin on immunologic function of the rats suffering Liver Cancer[J]. Western J Traditional Chin Med. 2018;031(009):26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo XP, Zhang XY, Zhang SD. Clinical trial on the effects of shikonin mixture on later stage lung cancer (in Chinese)[J]. Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi, 1991, 11(10):598–9, 580. [PubMed]

- 22.Liang W, Cai A, Chen G, et al. Shikonin induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and enhances chemotherapeutic sensitivity of gastric cancer through reactive oxygen species[J]. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han X, Kang KA, Piao MJ, et al. Shikonin exerts cytotoxic effects in human colon cancers by inducing apoptotic cell death via the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria-mediated Pathways[J]. Biomol Ther. 2019;27(1):41–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Bailey-Downs LC, Thorpe JE, Disch BC, et al. Development and characterization of a preclinical model of breast Cancer Lung Micrometastatic to Macrometastatic Progression[J]. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(5):e98624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arroyo-Crespo JJ, Armiñán A, Charbonnier D, et al. Characterization of triple-negative breast cancer preclinical models provides functional evidence of metastatic progression[J]. Int J Cancer. 2019;145(8):2267–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng L, Li W, Chen CS. Breast cancer animal models and applications[J]. Zool Res. 2020;41(5):477–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rakha EA, Pareja FG. New advances in molecular breast Cancer Pathology[J]. Sem Cancer Biol. 2020;72(9793):102–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo Z, Sun L, Xia H, et al. Shikonin as a WT1 inhibitor promotes promyeloid leukemia cell differentiation. Molecules[J]. 2022;27(23):8264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jia L, Zhu Z, Li H, et al. Shikonin inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion and promotes apoptosis in NCI-N87 cells via inhibition of PI3K/AKT signal pathway[J]. Artif Cells. 2019;47(1):2662–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji W, Sun X, Gao Y, et al. Natural compound shikonin is a novel PAK1 inhibitor and enhances efficacy of Chemotherapy against Pancreatic Cancer Cells[J]. Molecules. 2022;27(9):2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boulos JC, Rahama M, Hegazy M, et al. Shikonin derivatives for cancer prevention and therapy[J]. Cancer Lett. 2019;459:248–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lou W, Xiao S, Lin K. Identification of a hypoxia-suppressed lncRNA RAMP2-AS1 in breast cancer[J]. Noncoding RNA Res. 2024;9(3):782–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li MY, Mi C, Wang KS, et al. Shikonin suppresses proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest through the inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor-1α signaling[J]. Chem Biol Interact. 2017;274:58–67. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Maughan KL, Lutterbie MA, Ham PS. Treatment of breast cancer[J]. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(11):1339–46. [PubMed]

- 35.Golshan M, Loibl S, Wong SM, et al. Breast conservation after Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy for Triple-negative breast Cancer: Surgical results from the BrighTNess Randomized Clinical Trial[J]. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(3):e195410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nesstor P-F. Influence of doxorubicin on apoptosis and oxidative stress in breast cancer cell lines[J]. Int J Oncol. 2016;49(2):753–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang Q, Lan Y, Li Y, et al. Crizotinib prodrug micelles co-delivered doxorubicin for synergistic immunogenic cell death induction on breast cancer chemo-immunotherapy[J]. Eur J Pharm Biopharmaceutics: Official J Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Pharmazeutische Verfahrenstechnik e V. 2022;177:260–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Q, Gong T, Liu M, et al. Shikonin, a naphthalene ingredient: therapeutic actions, pharmacokinetics, toxicology, clinical trials and pharmaceutical researches[J]. Phytomedicine. 2022;94:153805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sui, Huang L, et al. Simultaneous Quantitative Analysis of Shikonin and Deoxyshikonin in Rat plasma by Rapid LC–ESI–MS–MS[J]. Chromatographia. 2010;72(1–2):63–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen Y, Chen Zong-yue, Chen L, et al. Shikonin inhibits triple-negative breast cancer-cell metastasis by reversing the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via glycogen synthase kinase 3β-regulated suppression of β-catenin signaling[J]. Biochem Pharmacol. 2019;166:33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bueno MJ, Ruiz-Sepulveda JL, Quintela-Fandino M. Mitochondrial inhibition: a treatment strategy in Cancer?[J]. Curr Oncol Rep. 2021;23(4):49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang N, Wu Y, Bian J, et al. Current development of ROS-Modulating agents as Novel Antitumor Therapy[J]. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2017;17(2):122–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krysko DV, Garg AD, Kaczmarek A, et al. Immunogenic cell death and DAMPs in cancer therapy[J]. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(12):860–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keenan TE, Tolaney SM. Role of Immunotherapy in Triple-negative breast Cancer[J]. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(4):479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nishikawa H, Koyama S. Mechanisms of regulatory T cell infiltration in tumors: implications for innovative immune precision therapies[J]. J Immunother Cancer. 2021;9(7):e002591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohue Y, Nishikawa H. Regulatory T (Treg) cells in cancer: can Treg cells be a new therapeutic target?[J]. Cancer Sci, 2019, 110(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Farhood B, Najafi M, Mortezaee K. CD8 + cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: a review[J]. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(6):8509–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang P, Zhou X, Zheng M, et al. Regulatory T cells are associated with the tumor immune microenvironment and immunotherapy response in triple-negative breast cancer[J]. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1263537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guo J, Chen T, Ma Z, et al. Oridonin inhibits 4T1 tumor growth by suppressing Treg differentiation via TGF-β receptor[J]. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;88:106831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bagher F. CD8 + cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: a review.[J]. J Cell Physiol. 2018;234(6):8509–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.