Summary

Serotonin (5-HT) modulates early development during critical periods when experience drives heightened levels of plasticity in neurons. Here, we investigate the cellular mechanisms by which 5-HT modulates critical period plasticity (CPP) in the olfactory system of Drosophila. We first demonstrate that 5-HT is necessary for experience-dependent structural plasticity in response to chronic CO2 exposure and can re-open the critical period long after it normally closes. Knocking down 5-HT7 receptors in a subset of GABAergic local interneurons was sufficient to block CPP, as was knocking down GABA receptors expressed by CO2-sensing olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs). Furthermore, direct modulation of OSNs via 5-HT2B receptors in CO2-sensing OSNs and autoreceptor expression by serotonergic neurons was also required for CPP. Thus, 5-HT targets individual neuron types in the olfactory system via distinct receptors to enable sensory driven plasticity.

Subject areas: Molecular neuroscience, Sensory neuroscience

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

5-HT modulates structural plasticity via multiple 5-HTRs

-

•

5-HT modulates both excitatory (OSNs) and inhibitory (LNs) components of olfaction

-

•

SSRI treatment induces critical period like structural plasticity in adults

Molecular neuroscience; Sensory neuroscience

Introduction

In early postnatal life of animals, all sensory systems exhibit heightened levels of plasticity and circuit refinement in response to environmental stimuli in a specific time window called critical period. Critical period plasticity (CPP) provides an excellent readout to assess how sensory experiences shape circuits early in life at the cellular and molecular level.1,2,3 Along with sensory experiences, neuromodulators like 5-HT also play an important role in shaping CPP. Initial experiments indicating the role of 5-HT in modulating sensory critical periods was observed in both the visual and somatosensory cortices in kittens and rats.4,5,6,7 Similarly, 5-HT has also been shown to modulate the early postnatal development of limbic circuits such as the pre-frontal cortex in humans as well as non-human primates and rodent models. Disruption in serotonergic signaling in this circuit has been linked to an increased risk for behavioral and cognitive deficits in adult mice.8,9,10,11 Thus, 5-HT targets multiple effector regions during early development to facilitate proper brain development and function in adults. However, 5-HT can activate several receptor subtypes expressed by distinct cell types within a network, so the cellular mechanisms by which 5-HT impacts CPP can be difficult to identify.

We took advantage of the wealth of transgenic tools and foundational work in the olfactory system of Drosophila to determine how 5-HT can impact different circuit mechanisms within an olfactory critical period. The organization of the fruit fly olfactory network is similar to that in mammals1,12 in that olfactory processing begins upon odor binding chemoreceptive proteins localized at the dendrites of olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs).13,14,15,16 All OSNs expressing the same complement of chemoreceptive proteins project to a distinct glomerulus to form an olfactory map within the primary olfactory center, the antennal lobe (AL).17 OSNs synapse upon second-order projection neurons (PNs) that project onto higher order olfactory centers. The cellular and molecular mechanisms of structural plasticity observed in olfactory CPP in the fruit fly is well known.18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27 Similar forms of experience-dependent olfactory plasticity have also been studied extensively and reviewed in other insects like honeybees, moths, butterflies, locusts, and ants.18 Most CPP studies in Drosophila were conducted using either CO2 or ethyl butyrate exposure as sensory stimuli or both. With either of the odors, chronic exposure during the critical period induced structural plasticity in the relevant glomerulus, causing a change of either an increase or a decrease in the glomerular volume. At the circuit level, the structural plasticity resulting in an increase in glomerular volume is manifested through an increase in the number of local interneuron (LN) and PN arbors innervating the glomerulus, whereas the total number of neurons remains intact.19,20,21,27 Glomerular volume decrease, on the other hand, is caused by retraction of the OSN axon fibers upon chronic ethyl butyrate exposure in a specific glomerulus.23 These studies demonstrated that the olfactory CPP in Drosophila shares many of the same molecular mechanisms as visual CPPs.2,3,20,21,22,23,27,28,29,30 In both cases, CPP involves GABAergic and glutamatergic signaling, Ca2+/Calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase and cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB)-dependent gene transcription.20,21,31 However, although 5-HT neuromodulation has been shown to be required for visual critical periods in mammals,5,6,7,32,33,34,35 it has not been studied with respect to CPP in the olfactory system of mammals or insects.

In this study, we investigate how 5-HT modulates olfactory critical periods, and we focus on the behaviorally relevant36,37 CO2-sensing circuit in Drosophila. Since the V glomerulus is exclusively dedicated to respond to CO2, and the CPP mechanisms are already known for this glomerulus, it is ideal for studying the effect of serotonergic modulation. We performed cell-type specific genetic manipulations of the serotonergic system to identify where 5-HT is required during odor-evoked structural plasticity in the olfactory circuit. Our results show that during the critical period, 5-HT modulates distinct cell types in the AL via activation of different 5-HT receptor subtypes. We thus identified cell types where serotonergic modulation may be interacting with the previously described mechanisms of CPP to modulate structural plasticity during CPs.

Results

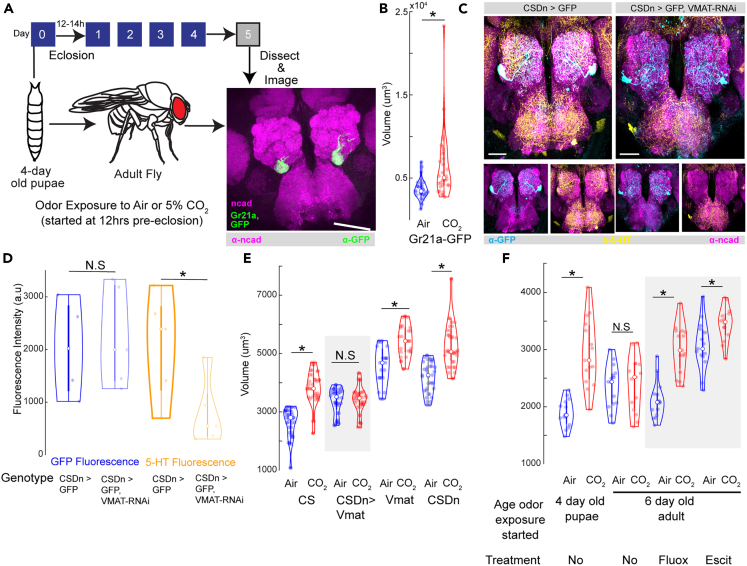

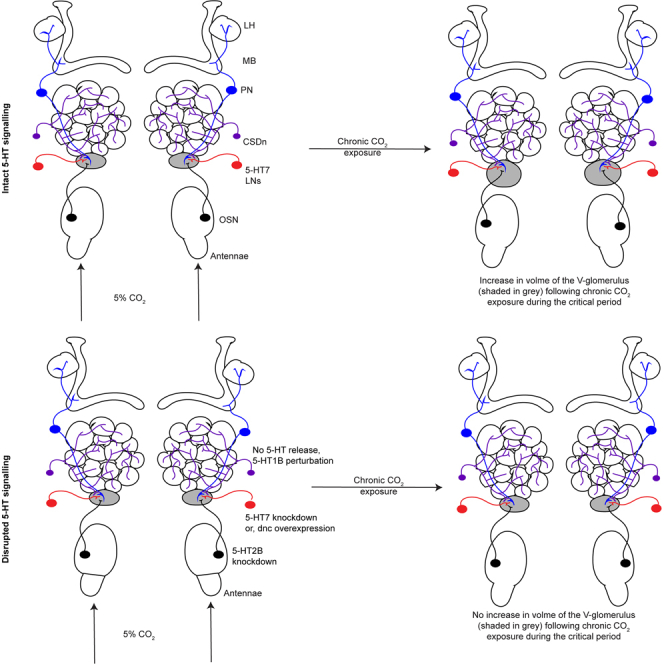

Olfactory CPP requires the release of 5-HT by the serotonergic neurons

In Drosophila, the olfactory CPP manifests as a change in the volume of the glomerulus innervated by OSNs responsive to the odor used as a stimulus (Figures 1A and 1B).20,21,27 Consistent with previous reports,20,21,27 in flies where 5-HT transmission is intact, the V-glomerulus increased in volume in flies exposed to CO2 compared to air exposed (Figure 1B). In Drosophila and other holometabolous insects, a single pair of serotonergic neurons called the contralaterally projecting serotonin immunoreactive deuterocerebral neurons (CSDns) innervate the AL38,39,40 (Figure 1C) and supply serotonin.38,40,41,42 We thus assessed the role of 5-HT in CPP in the Drosophila olfactory system by measuring the structural plasticity induced in the CO2-sensitive V-glomerulus upon chronic exposure to 5% CO2.20,21,27 We employed the R60F02-Gal4 promoter line that labels the CSDns43 to prevent serotonin release by knocking down Vmat in these cells via expression of Vmat RNAi. Previous work from our lab has shown that endogenous release of 5-HT from the CSDns modulates activity in the AL,41 and the expression of the Vmat-RNAi transgene in the CSDns successfully eliminates these 5-HT-mediated responses in the AL.44 To further validate the impact of RNAi knockdown of Vmat on 5-HT signaling in the CSDns, we immunolabeled the brains of R60F02-Gal4 flies driving either UAS-GFP or UAS-GFP and UAS-Vmat-RNAi (Figure 1C) and compared the relative 5-HT immunofluorescence intensity of the CSDns (Figure 1D). Flies in which R60F02-Gal4 drove the expression of the Vmat-RNAi had a near-complete loss of 5-HT immunolabeling, whereas 5-HT immunolabeling was intact in brain regions not innervated by the CSDns as well as in the CSDns of control flies. 5-HT has been shown to affect odor-evoked responses in the olfactory systems of many species of insects.45,46,47,48,49 Chronic CO2 exposure of flies deprived of CSDn 5-HT output failed to undergo structural plasticity in the V (Figure 1E), suggesting that serotonin release is required for structural plasticity. To further ascertain if serotonin is sufficient to induce structural plasticity following chronic odor exposure, we employed selective 5-HT reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) like fluoxetine and escitalopram. Both SSRIs are known to slow down 5-HT reuptake at the dosage concentration of 1 μM but only escitalopram is known to increase 5-HT release at this concentration.50 While 6-day-old adult flies fail to undergo structural plasticity in the V following chronic CO2 exposure, flies of the same age treated with an SSRI like fluoxetine or escitalopram undergo structural plasticity (Figure 1F). Together, these results indicate that 5-HT is required and sufficient to induce structural plasticity following chronic odor exposure.

Figure 1.

Blocking serotonin release from CSDns prevents structural plasticity during the critical period

(A) Schematic of the experimental protocol. Four-day-old pupae are collected and subject to 5% CO2 for 5 days. On day 5 after eclosion, flies are collected and stained with n-cadherin and imaged under a confocal microscope to analyze structural plasticity. Confocal maximum intensity projection of AL by CO2-responsive V-glomerulus in green co-labeled for n-cadherin (magenta).

(B) Quantification of V-glomerulus volumes comparing air- (right) and 5% CO2 (left)-exposed flies during the critical period. Genotype shown here is endogenously expressed GFP under the Gr21a promoter (Gr21aGFP).

(C) Confocal maximum intensity projections of AL innervation by CSDns in CSDn-Gal4 > UAS-mcd8::GFP and CSDn-Gal4 > UAS-GFP, UAS-Vmat-RNAi flies, labeled for GFP (blue), 5-HT (yellow), and n-cadherin (magenta).

(D) Quantification of GFP (n = 4 for each genotype) and 5-HT (n = 5 for each genotype) immunofluorescence in CSDns in CSDn-Gal4 > UAS-mcd8::GFP and CSDn-Gal4 > UAS-GFP, UAS-Vmat-RNAi flies.

(E) Quantification of V glomerulus volumes comparing air- and 5% CO2-exposed flies during the critical period. Four genotypes are shown here from left to right: Canton-S (wildtype), CSDn-Gal4>UAS-Vmat-RNAi (CSDn targeted Vmat knockdown), w1118;;UAS-Vmat-RNai (background control for Gal4) and y,v;; CSDn-Gal4 > RNAi background (background control for RNAi).

(F) Quantification of V glomerulus volumes comparing air- and 5% CO2-exposed Canton-S flies of various ages and SSRI treatment conditions. Different experimental conditions and ages of flies are shown here from left to right: 4-day-old Canton-S pupae without SSRI, 6-day-old Canton-S flies without SSRI treatment, 6-day-old Canton-S flies with fluoxetine treatment, 6-Day-old Canton-S flies with escitalopram treatment. ∗ indicates p < 0.05; N.S indicates p > 0.05; n ≥15. All violin plots include individual data points (colored circles) and mean (white circle). The boxplot of the data is also represented at the center of the violin. The scale bar indicates 50 μm, and gray boxes indicate experimental fly lines in all cases. Detailed genotypes of flies for each experimental condition can be found in Table 1 and the antibody concentrations used in Table 2.

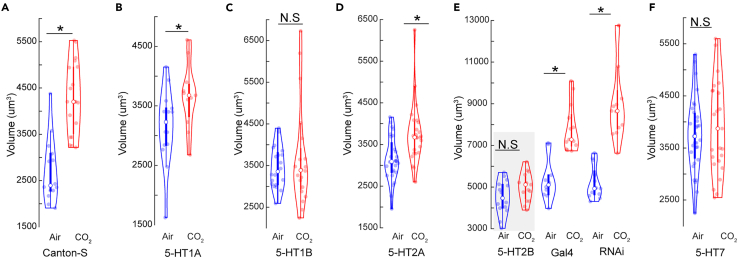

Serotonin modulates the olfactory CPP via multiple receptor targets

Having established that 5-HT plays a role in the olfactory CPP in Drosophila, we wished to determine the cellular and molecular targets by which 5-HT was exerting its impact. 5-HT mediates its effect in cells by concentration-dependent activation of its cognate receptors. In Drosophila, there are five serotonin receptors (5-HTRs): 5-HT1AR, 5-HT1BR, 5-HT2AR, 5-HT2BR, and 5-HT7R.51,52,53,54 We systematically interrogated 5-HTR signaling to determine which receptors are involved in mediating structural plasticity during the critical period (Figure 2). For this, we used the same experimental paradigm as before and employed the null mutants of the 5-HTRs generated by a CRISPR knock in strategy to replace all or parts of the gene encoding the 5-HTRs with the GAL4 gene.54 Chronic exposure of CO2 in flies with mutations in the 5-HT1BR and 5-HT7R (Figures 2C and 2F) failed to demonstrate structural plasticity in the V-glomerulus during the critical period. Since the 5-HT2BR homozygous mutants were not viable in our hands, we employed a slightly modified strategy to investigate its effects on CPP. We crossed the heterozygous 5-HT2BR mutants expressing Gal4 under the 5-HT2BR promoter to induce expression of 5-HT2B-RNAi (for genotypes see Table 1). This 5-HT2BR deficient state was sufficient to block structural plasticity in the V-glomerulus during the critical period (Figure 2E). In contrast, we still observed structural plasticity in 5-HT1AR and 5-HT2AR mutants upon chronic CO2 exposure during the CP (Figures 2B and 2D), indicating that these two receptors do not underlie the effects of 5-HT on early life olfactory plasticity. Together, these results indicate that 5-HT1BR, 5-HT2BR, and 5-HT7R are required during the critical period.

Figure 2.

Serotonin acts through multiple receptors during the critical period

(A) Comparison of V-glomerulus volumes in air- and 5% CO2-exposed brains in wild-type Canton-S flies.

(B–D and F) Comparison of V-glomerulus volumes in air- and 5% CO2-exposed brains of 5-HT1AR (B), 5-HT1BR (C), 5-HT2AR (D), and 5-HT7R (F) knockout flies.

(E) Comparison of V-glomerulus volumes in air- and 5% CO2-exposed brains of flies with genotypes (left to right): 5-HT2B knockdown in 5-HT2B heterozygous mutants, UAS-5HT2B-RNAi in Gal4 knock in background, heterozygous 5-HT2B mutant with Gal4 knock in RNAi background (y,v; 5HT2B[Gal4] > TRiP background). ∗ indicates p < 0.05; N.S indicates p > 0.05; n ≥ 15 and gray boxes indicate experimental fly lines in all cases. All violin plots include individual data points (colored circles) and mean (white circle). The boxplot of the data is also represented at the center of the violin. Detailed genotypes of the flies used in each experimental condition can be found in Table 1 and the antibody concentrations used in Table 2.

Table 1.

Genotypes of flies in the figures

| Figure | Genotype | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1A and 1B | Gr21a-Mmus\Cd8a.GFP | BDSC #52619 |

| 1C and 1D | R60F02-Gal4/10X-UAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP R60F02-Gal4/UAS-Vmat-RNAi,10X-UAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP |

R60F02-Gal4 (BDSC #48228) 10X-UAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP (BDSC #32185) UAS-Vmat-RNAi (BDSC #44471)44 |

| 1E | Left to right: Canton-S R60F02-Gal4/UAS-Vmat-RNAi w1118;;UAS-Vmat-RNAi P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attP2/R60F02-Gal4 |

Canton-S (BDSC #64349), w1118 (BDSC#5905) P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attP2 (BDSC #36303) |

| 1F | Canton-S | – |

| 2A | Canton-S | – |

| 2B | TI{GAL4}5-HT1A[Gal4]/TI{GAL4}5-HT1A [Gal4] | BDSC#86275 |

| 2C | TI{GAL4}5-HT1B[Gal4]/TI{GAL4}5-HT1B [Gal4] | BDSC #86276 |

| 2D | TI{GAL4}5-HT2A[Gal4]/TI{GAL4}5-HT2A [Gal4] | BDSC #86277 |

| 2E | Left to right: UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi; TI{GAL4}5-HT2B[Gal4] w1118; UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi P{y[+t7.7]=Cary P [attp40]; TI{GAL4}5-HT2B - [Gal4] |

UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi (BDSC #60488) TI{GAL4}5-HT2B[Gal4] (BDSC #86278) P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP[attp40] (BDSC #36304) |

| 2F | TI{GAL4}5-HT7[Gal4] | BDSC #86279 |

| 3A | w1118; 5-HT1A-7×GFP11-HA/5-HT1A-(MI1140)-T2A-GAL4,10×UAS-mCD8-GFP | 5-HT1A-7×GFP11-HA (this study) 5-HT1A-(MI1140)-T2A-GAL455 |

| 3B | 10×UAS-mCD8-GFP/w1118; 5-HT1B-(MI5213) -T2A-Gal4/5-HT1B-7×GFP11-HA | 10×UAS-mCD8-GFP (BDSC #32189) MiMIC 5213 HT1B T2A Gal455 5-HT1B-7×GFP11-HA (this study) |

| 3C | w1118; 10×UAS-mCD8-GFP/+; 5-HT2A-(MI459)-T2A-Gal4/5-HT2A(BFH)-7×GFP11-HA | 10×UAS-mCD8-GFP (BDSC #32186) 5-HT2A-(MI459)-T2A-Gal455 5-HT2A(BFH)-7×GFP11-HA (this study) |

| 3D | w1118; 10×UAS-mCD8-GFP/+; 5-HT2B-(MI6500)-T2A-Gal4/5-HT2B-7×GFP11-HA | 5-HT2B-(MI6500)-T2A-Gal455 5-HT2B-7×GFP11-HA (this study) |

| 3E | w1118; +/+; 5-HT7-(MI215)-T2A-Gal4,10× UAS-mCD8-GFP/5-HT7-7×GFP11-HA |

5-HT7-(MI215)-T2A-Gal455 5-HT7-7×GFP11-HA (this study) |

| 4A | R70A09-GAL4}attP2/10XUAS-IVS-mCD8:: GFP | R70A09-GAL4}attP2 (BDSC #47720) |

| 4B | 10xUAS-sfGFP1-10; R70A09-GAL4/5-HT7-7xGFP11-HA (this study) | 10xUAS-sfGFP1-10 (VK00022; BDSC#93189) - Gift from J. Wildonger, University of California, San Diego |

| 4C | NP1227-Gal4 (LN1)/10XQUAS-6XmCherry -HA; R70A09Q/10XUAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP | NP1227-Gal4 (LN1) (DGRC #103945) 10XQUAS-6XmCherry-HA} (BDSC #52269) GMR70A09Q44 |

| 4E | NP2426-Gal4 (LN2); UAS-mCherry/QUAS-mCD8-GFP; R70A09Q | NP2426-Gal4 (LN2) (DGRC #104198) UAS-mCherry (BDSC #59021) QUAS-mCD8-GFP (BDSC #30002) |

| 4G | Left to right: Canton-S R70A09-Gal4/UAS-5HT7-RNAi w1118;;UAS-5HT7-RNAi P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp2/R70A09 -Gal4 |

UAS-5HT7-RNAi (BDSC #32471)44 P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp2 (BDSC #36303) |

| 4H | Left to right: Canton-S UAS-dunce;;R70A09-Gal4, w1118/UAS-dunce |

w, UAS-dunce; +; + was a gift from B.White Lab at NIH. The fly was first described in Cheung et al., 199956 |

| 4I | Left to right: Canton-S Peb-Gal4; UAS-GABAB-RNAi; UAS-GABAB-RNAi Peb-Gal4; UAS-Rdl-RNAi Orco-Gal4/UAS-GABAB-RNAi; UAS-GABAB -RNAi, Orco-Gal4/UAS-Rdl-RNAi Peb-Gal4; P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp40 Peb-Gal4;; P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp2 Orco-Gal4/P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp40 Orco-Gal4; P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp2 w1118; UAS-GABAB-RNAi; UAS-GABAB-RNAi w1118; UAS-Rdl-RNAi |

UAS-GABAB-RNAi; UAS-GABAB-RNAi: Gift from Jing Wang57 Peb-Gal4 (BDSC #80570) UAS-Rdl-RNAi (BDSC #52903)58 Orco-Gal4 (BDSC #26818) |

| 5A | UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi; Gr21a-Gal4/5-HT2B-7x-GFP11-HA. | Gr21a-Gal4 (BDSC #23890) |

| 5B | UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi; Gr63a-Gal4/5-HT2B-7x-GFP11-HA. | Gr63a-Gal4 (BDSC #9943) |

| 5C | Peb-Gal4; UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi; 5-HT2B-7x-GFP11-HA. | – |

| 5D | Left to right: Canton-S UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi; Gr21a-Gal4 w1118; UAS-5HT2B-RNAi P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp40; Gr21a-Gal4 |

– |

| 5E | Left to right: Canton-S UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi/Gr63a-Gal4 w1118; UAS-5HT2B-RNAi P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp40/Gr63a-Gal4 |

– |

| 5F | Left to right: Canton-S Peb-Gal4; UAS-5HT2B-RNAi UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi/Orco-Gal4 w1118; UAS-5HT2B-RNAi Peb-Gal4; P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp40 P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp40/Orco-Gal4 |

– |

| 6A and 6B | 5-HT2B-7x-GFP11-HA | This study |

| 7A | Left to right: Canton-S R60F02-Gal4>UAS-5-HT1B-RNAi Trh-T2A-Gal4>UAS-5-HT1B-RNAi w1118; UAS-5-HT1B-RNAi P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp40; R60F02-Gal4 P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attp40; Trh-T2A-Gal4 |

UAS-5-HT1B-RNAi (BDSC # 51842)58,59 Trh-T2A-Gal4 (BDSC #84694) |

| 7B | Left to right: Canton-S UAS-5-HT1B; R60F02-Gal4 UAS-5-HT1B; + +; R60F02-Gal4 |

UAS-5-HT1B (BDSC #27632) |

All MiMIC lines were a gift from Dr. Herman A. Dierick, Baylor College of Medicine.

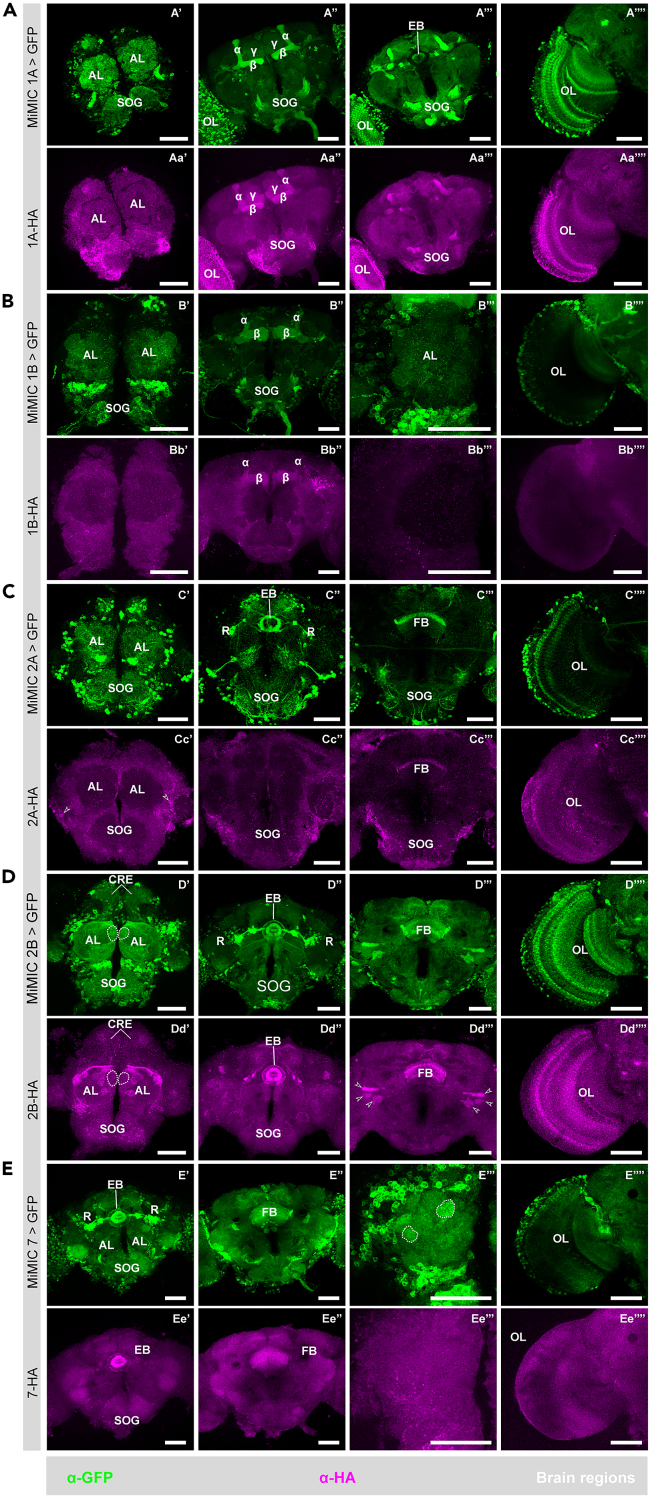

Previous studies demonstrated that all five 5-HT receptors are expressed by distinct neuron types in the AL.60 These studies relied on GFP expression induced by the Gal4 protein expressed from the endogenous promoter and provided a detailed list of 5-HTRs expressed by distinct cell types in the AL (see Sizemore and Dacks, 2017). Although this approach reveals which cells classes express which 5-HTRs, the method does not easily identify where and when the receptors are trafficked within the neurons. More recently, endogenously tagged receptors for 5-HT1A, 5-HT2A, and 5-HT2B have been designed to conditionally or constitutively tag these receptors and track where they are trafficked but not for 5-HT1B and 5-HT7.61 We therefore generated flies with an endogenous HA-tag and the GFP11 fragment on 5-HTRs.62,63,64 We employed a CRISPR-Cas9-based strategy65,66 to generate these flies (refer to STAR Methods and Table 2 for detailed stra). The split-GFP is an elegant tool that consists of splitting the superfolder GFP (sfGFP) between the beta-strand 10 and 11 to generate two non-fluorescing, self-complementing fragments: GFP1-10 and GFP11.67,68 Only cells that would simultaneously express both fragments will be able to form the complete sfGFP molecule that would fluoresce (Figure S1A). Additionally, the HA-tagged 5-HTRs would enable us to locate 5-HTR expression in all cells by immunolabeling against HA (Figure S1B). Together, this strategy allows us to simultaneously visualize the localization of 5-HTRs and determine the cell types that express them (Figures S1C–S1F). We found that the expression patterns of these 5-HTR lines labeled using the MiMIC-5HTR-Gal4 drivers to be consistent with previously reported expression patterns of the 5-HTRs55,60 using more traditional GAL4/UAS approaches (Figures 3A–3E).

Table 2.

Concentration of antibodies used in this study

| Name | Type | Species of origin | Dilution | Supplier | Cat. # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-hemagglutinin(HA) | Primary | Mouse | 1:500 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 26183; RRID: AB_2533049 |

| Anti-5-HT | Primary | Rabbit | 1:5000 | Immunostar | 20080; RRID: AB_572263 |

| Anti-reconstituted GFP | Primary | Mouse | 1:1000 | Sigma | G6539; RRID: AB_259941 |

| Anti-GFP | Primary | Chicken | 1:1000 | Abcam | ab13970; RRID: AB_300798 |

| nc82 Antibody | Primary | Mouse | 1:50 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) | nc82; RRID: AB2314866 |

| N-cadherin (n-cad) | Primary | Rat | 1:50 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) | DN-EX #8; RRID: AB_528121 |

| Anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 488 | Secondary | Goat | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-11039; RRID: AB_2534096 |

| Anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 | Secondary | Goat | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-11004; RRID: AB_2534072 |

| Anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 546 | Secondary | Donkey | 1:1000 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-10040; RRID: AB_2534016 |

| Anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 633 | Secondary | Goat | 1:400 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-21050; RRID: AB_2535718 |

Figure 3.

Distribution of 5-HTRs in adult D. melanogaster brains

(A) Brain sections indicate 5-HT1A expression in the AL, suboesophageal ganglion (SOG), MB, ellipsoid body (EB), and optic lobe (OL). As shown in (A″) and (Aa’'), both α-HA and α-GFP indicate expression in all three lobes of MB, including α, β, and γ lobes. Note, as shown in (Aa’’’), 5-HT1A expression in EB is largely devoid revealed by α-HA, contrary to the α-GFP staining pattern shown in (A‴).

(B) Brain sections indicate 5-HT1B expression in SOG, AL, MB, and OL. In contrast to the MiMIC approach, which labels cell bodies broadly in the brain, immunostaining against the HA tag show significant distribution of the receptor only in the α and β lobes of MB.

(C) Brain sections indicate 5-HT2A expression in many areas such as AL, SOG, EB, the fan-shaped body (FB), and optical lobe (OL). Among all these areas, the staining by α-HA shows weak signals in FB (Cc’’’) and probably in OL (Cc’’’’, indicated by the arrow heads). The contrast of the images from the α-HA channel was elevated to see weak signals, resulting in irregular signal presentation that might be artifacts, as indicated by the arrow heads in (Cc’-Cc’’’).

(D) Brain sections indicate 5-HT2B expression in AL, crepines (CRE), SOG, EB, FB, and OL. In ALs, the MiMIC approach indicates a relatively high expression in a medial glomerulus, as emphasized by the white dashed circle, which is not consistent in the α-HA channel (Dd’). It is noticeable that localization of this receptor in the R neurons (R) and their arborizations toward EB (D″, arrow heads) is missing in the staining pattern revealed by α-HA (Dd’’). Arrow heads in (D‴) and (Dd’’’) indicate some unknown structures stained in both channels.

(E) Brain sections indicate 5-HT7 expression in SOG, EB, FB, and (E‴’/Ee’’’’) OL. In the antennal lobe labeled with the MiMIC approach, extraordinary signals were observed in an anterior dorsal glomerulus as indicated by dashed circle on the right side and a posterior lateral glomerulus as indicated by dashed circle on the left side (E‴). In contrast, no prominent signals showed in these two glomeruli as indicated by the α-HA approach (Ee’’’). Signals were observed in the optical lobe (OL) revealed by both approaches (E‴’/Ee’’’’). For both (E‴/Ee’’’) and (E‴’/Ee’’’’), the brain was oriented with the lateral toward left and the dorsal upward. The scale bar indicates 50 μm in all cases. Detailed genotypes of flies for each experimental condition can be found in Table 1 and the antibody concentrations used in Table 2.

Next, we investigated the differential expression patterns of the 5-HTRs in the olfactory processing centers of the brain. The 5-HT1Rs are expressed in varying degrees within the AL and MBs (Figure 3A). The 5-HT2ARs are mostly expressed in the cells surrounding and innervating the AL, most likely the LNs and PNs (Figures 3C’ and 3Cc’). Remarkably 5-HT2BRs is not uniformly expressed throughout the AL (Figures 3D’, 3Dd’, and S2A–S2I). This indicates varying levels of 5-HT2BR-mediated serotonergic modulation in the OSNs. Consistent with prior reports,60 we found most of the 5-HT2BR expression in the AL to be in the OSNs. When we removed the antennae or the maxillary palps that houses the cell body and dendrites of OSNs, 5-HT2BR expression in the related AL region the OSNs project to is eliminated (Figure S2J). Similarly, we were able to selectively knockdown 5-HT2BRs expression using Gal4 drivers for OSN subtypes using an RNAi against 5-HT2BR (Figures S2K and S2L). The AL neuropil is innervated by various cells including OSNs, PNs, LNs, and CSDns. We found most of the 5-HT7R expression in the cells surrounding the AL, most likely in the LNs and PNs (Figures 3E’ and 3E‴). We also found unusually high GFP labeling in two glomeruli in the AL (Figure 3E’’’) but no corresponding HA labeling (Figure 3Ee’’’) for 5HT7R expression using the MiMIC-5HT7R-Gal4 promoter line. Taken together, these results show that 5-HT targets multiple components of olfactory processing through distinct receptors. Therefore, serotonin could target multiple serotonergic receptors on distinct cell types to mediate their effects during the olfactory critical period.

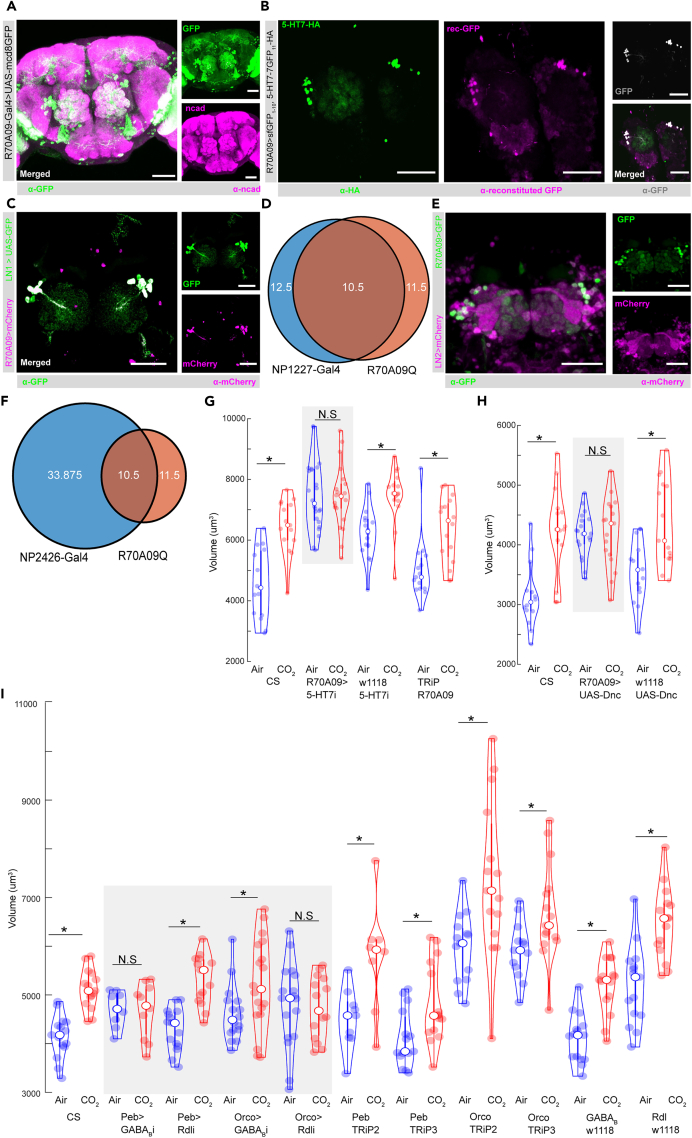

Serotonin modulates distinct components of sensory processing during the critical period

Next, we wanted to isolate the neuronal basis of 5-HTR signaling that modulates CPP. Earlier studies have identified a crucial role of inhibitory, GABAergic LNs, namely LN1 and LN2, during the olfactory critical period.20,21,27 Previous work in our lab has identified a distinct population of 5-HT7R-expressing GABAergic LNs (R70A09-Gal4) that are responsive to low 5-HT concentrations and modify odor coding in the AL.44 As a population, these LNs innervate all glomeruli including the V-glomerulus (Figure 4A). We also found that R70A09-GAL4 LNs express 5-HT7Rs (Figure 4B) and show almost a complete overlap with LN1 neurons (Figures 4C and 4D) and a partial overlap with the LN2 neurons (Figures 4E and 4F). The LN1 neurons have been previously implicated to induce an increase in the number of PN arbors leading to structural plasticity during the critical period.20,21 We therefore sought to determine if these LNs are the target for 5-HT modulation via the 5-HT7Rs and found that knocking down 5-HT7Rs in the R70A09 LNs was sufficient to prevent CPP in the V-glomerulus (Figure 4G). In Drosophila, 5-HT7Rs are known to activate an adenylate cyclase that results in an increase in cytosolic cAMP.51,69 When we overexpress the cAMP-specific phosphodiesterase dunce to deplete cAMP selectively in the R70A09 LNs, keeping the 5-HT7Rs and adenylate cyclase intact, CPP in the V-glomerulus is abolished (Figure 3H). These results indicate that both 5-HT7R signaling and cAMP in R70A09-GAL4 LNs play an important role during the CP that ultimately permits the induction of structural plasticity in the cognate glomerulus.

Figure 4.

5-HT7 targets GABAergic inhibition in the primary olfactory circuit

(A) Confocal maximum intensity projection of the R70A09 LNs expressing GFP in green, co-labeled for n-cadherin in magenta. The V-glomerulus is circled in the merged and GFP channels.

(B) Confocal maximum intensity projection of the AL showing R70A09 LNs co-labeled for 5-HT7-HA in green, reconstituted GFP in magenta, GFP in gray, and the merged channel.

(C) Confocal maximum intensity projection of the AL showing the overlap between R70A09 LNs in magenta and LN1 neurons in green.

(D) The R70A09 line labels 11–12 LNs, LN1 labels 12–15 LNs per hemisphere. There is a total overlap of 10–11 cells between R70A09 and LN1 population per hemisphere.

(E) Confocal maximum intensity projection of the AL showing the overlap between R70A09 LNs in green and LN2 in magenta.

(F) The R70A09 line labels 11–12 LNs, LN2 labels 33–44 LNs per hemisphere. There is a total overlap of 10–11 cells between R70A09 and either LN1 or LN2 population per hemisphere.

(G) Quantification of V glomerulus volumes comparing air- and 5% CO2-exposed flies during the critical period. Four genotypes are shown here from left to right: CS (Canton-S wildtype), R70A09>5-HT7i (R70A09 targeted 5-HT7 knockdown), w1118 5-HT7i (background control for Gal4), and TRiP R70A09 (background control for RNAi).

(H) Comparison of V-glomerulus volumes in air- and 5% CO2-exposed brains of flies with overexpression of dunce in the R70A09 LNs. Three genotypes are shown here from left to right: CS (Canton-S wildtype), R70A09>UAS-Dnc (dunce overexpression in R70A09 LNs), and w1118 UAS-Dnc (background for Dnc and R70A09).

(I) Comparison of V-glomerulus volumes in air- and 5% CO2-exposed brains of flies with GABA receptor knockdown in OSNs. Eleven genotypes are shown here from left to right: CS (Canton-S wildtype), Peb>GABABi (GABAB knockdown in all OSNs), Peb>Rdli (GABAA knockdown in all OSNs), Orco>GABABi (GABAB knockdown in Or83b OSNs), Orco>Rdli (GABAA knockdown in Or83b OSNs), Peb TRiP2 (background control for Rdl RNAi crossed with Peb-Gal4), Peb TRiP3 (background control for GABAB RNAi crossed with Peb-Gal4), Orco TRiP2 (background control for Rdl RNAi crossed with Orco-Gal4), Peb TRiP3 (background control for GABAB RNAi crossed with Orco-Gal4), w1118 GABABi (background for Gal4 crossed with GABAB-RNAi), and w1118 Rdli (background for Gal4 crossed with Rdl-RNAi). ∗ indicates p < 0.05; N.S indicates p > 0.05. n>=15. All violin plots include individual data points (colored circles) and mean (white circle). The boxplot of the data is also represented at the center of the violin. The scale bar indicates 50 μm, and gray boxes indicate experimental fly lines in all cases. Detailed genotypes of flies for each experimental condition can be found in Table 1 and the antibody concentrations used in Table 2.

The R70A09 LNs that express 5-HT7 receptors are GABAergic in nature and release GABA upon activation.44 The pan-glomerular innervation of these LNs implies that they release GABA all over the AL. Apart from these LNs, other GABAergic LNs also exist in the AL that can be sensitive to serotonergic modulation. Previous work has shown that GABA released from the GH298 LNs that are distinct from the R70A09 LNs mediate glomerulus selective presynaptic divisive gain control in Or83b-expressing OSNs in adult Drosophila but do not affect CO2 responses in the Gr21a-expressing OSNs.57 Consistent with these studies, knocking down GABAB and GABAA receptors, respectively, in the CO2-sensing OSNs and PNs was not sufficient to block structural plasticity during the CP.20,23 However, 5-HT7R-mediated activation in the R70A09 LNs and thereby GABA release is important for inducing CPP. Therefore, it is likely that R70A09 LN-activation-linked GABA release during the critical period could lead to network level changes in the AL that ultimately facilitate structural plasticity in the cognate glomerulus. We asked if the two GABA receptors expressed in the fly, the GABAA and GABAB receptors, are required for global inhibition in the OSNs during the critical period. When we knock down GABAB receptors in all OSNs, we saw no structural plasticity in the V-glomerulus (Figure 4I). In contrast, knocking down GABAA receptors in all OSNs did not hinder CPP in the V (Figure 4I). Finally, we targeted Or83b OSNs in the AL using the Orco-Gal4 promoter line. This enabled targeting multiple OSNs responsive to different odors44,57 but not the CO2 sensing ones. Surprisingly, flies expressing GABAA RNAi in Or83b OSNs failed to undergo structural plasticity in the V upon CO2 exposure (Figure 4H). However, knocking down GABAB in the Or83b OSNs was not sufficient to prevent structural plasticity in the V in response to CO2 (Figure 4I). This shows that GABAergic inhibition during the critical period via GABAA is required in a broader sub-population of OSNs in the AL but not selectively in the cognate glomerulus because Or83b OSNs do not innervate the V and few other glomeruli. On the other hand, GABAergic inhibition via GABAB is required in all OSNs in the AL including the V glomerulus, as Peb-Gal4 is expressed in all OSNs. Therefore, GABA targets distinct OSNs through GABAA and GABAB receptors to facilitate CPP in the V glomerulus.

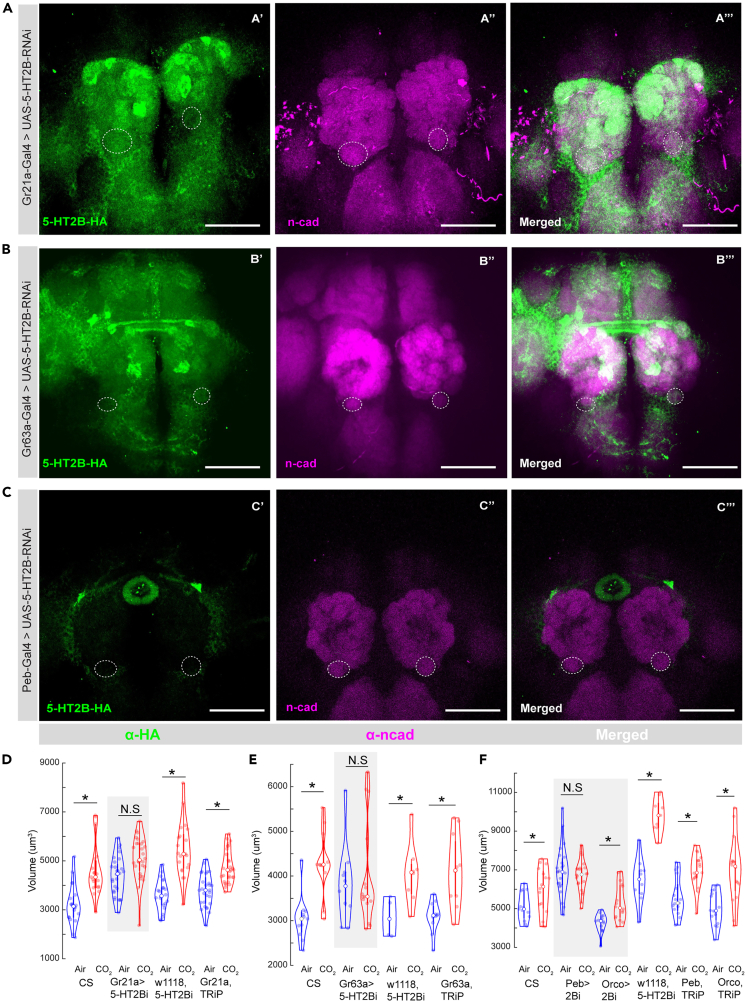

Next, we asked which cells projecting to the AL could be the source of 5-HT2BR-mediated serotonergic modulation of the olfactory CPP. We hypothesized that 5-HT targets 5-HT2BRs on OSNs during the critical period. Previous research has shown that the 5-HT2BRs are expressed by all OSNs and a few LNs and PNs in the AL.60 We showed earlier in Figure S2J that the majority of the 5-HT2BR expression in the antennal lobe is due to their expression by the OSNs. Therefore, we selectively knocked down expression of the 5-HT2BRs in the V-glomerulus OSNs (Figure 5). In the CO2-detecting OSNs, two chemoreceptors, Gr21a and Gr63a, are co-expressed to form a functional CO2 responsive odor receptor.70 However, in our 5-HT2BR knockdown experiments, we observed residual 5-HT2BR expression in the V-glomerulus using the Gr21a-GAL4 driver line (Figure 5A). Therefore, 5-HT2BR knockdown driven by the Gr21a-Gal4 line was not sufficient to prevent CPP in the V-glomerulus (Figure 5D). In contrast, driving the 5-HT2BR RNAi using Gr63a-Gal4 significantly reduced 5-HT2BR expression in the V-glomerulus without impacting expression in the rest of the AL (Figure 5B). This selective knockdown of the 5-HT2BRs by the Gr63a-Gal4 line was sufficient to prevent the induction of structural plasticity in the V-glomerulus (Figure 5E), suggesting that 5-HT2BR expression is required by OSNs within the glomerulus expanding during the CP. To determine if 5-HT2BR expression by OSNs in other glomeruli is required for CPP in the V-glomerulus, we next extended the 5-HT2BR knockdown using drivers expressed broadly in all OSNs (Peb-Gal4) or in many OSNs, except those projecting to the V and a few other glomeruli (Orco-Gal4). We found that flies that expressed 5-HT2B RNAi in all OSNs (Figure 5C) failed to undergo structural plasticity in the V-glomerulus in response to chronic CO2 exposure (Figure 5F). In contrast, 5-HT2B knockdown in multiple OSNs using the Orco-Gal4 driver line did not show any deficits in structural plasticity in response to CO2 (Figure 5F). Together, these results show that the 5-HT2BR expression is required in cognate ORNs of the V glomerulus for proper expression of CPP.

Figure 5.

5-HT2BRs are required in OSNs during the critical period

(A) Insufficient 5-HT2B knockdown in the CO2-sensing OSNs by Gr21a-Gal4. The V glomerulus is circled on all three channels.

(B) 5-HT2B knockdown in the CO2-sensing OSNs by Gr63a-Gal4. The V glomerulus is circled on all three channels.

(C) 5-HT2B knockdown in all OSNs but no other brain regions by Peb-Gal4. The V glomerulus is circled on the n-cad (magenta) and merged channels.

(D) Quantification of V glomerulus volumes comparing air- and 5% CO2-exposed flies during the critical period. Four genotypes are shown here from left to right: CS (Canton-S wildtype), Gr21a>5-HT2Bi (5-HT2B knockdown in CO2 OSNs), w1118 5-HT2Bi (background control for Gal4), and Gr21a, TRiP (background control for RNAi).

(E) Quantification of V glomerulus volumes comparing air- and 5% CO2-exposed flies during the critical period. Four genotypes are shown here from left to right: CS (Canton-S wildtype), Gr63a>5-HT2Bi (5-HT2B knockdown in CO2 OSNs), w1118, 5-HT2Bi (background control for Gal4), and Gr63a, TRiP (background control for RNAi).

(F) Quantification of V glomerulus volumes comparing air- and 5% CO2-exposed flies during the critical period. Six genotypes are shown here from left to right: CS (Canton-S wildtype), Peb>5-HT2Bi (5-HT2B knockdown in all OSNs), Orco> 2Bi (5-HT2B knockdown in Or83b OSNs), w1118,5-HT2Bi (background control for Gal4), Peb, TRiP (background control for 5-HT2B-RNAi), and Orco, TRiP (background control for 5-HT2B-RNAi). ∗ indicates p < 0.05; N.S indicates p > 0.05. n>=15. The scale bar indicates 50 μm, and gray boxes indicate experimental fly lines in all cases. All violin plots include individual data points (colored circles) and mean (white circle). The boxplot of the data is also represented at the center of the violin. Detailed genotypes of flies for each experimental condition can be found in Table 1 and the antibody concentrations used in Table 2.

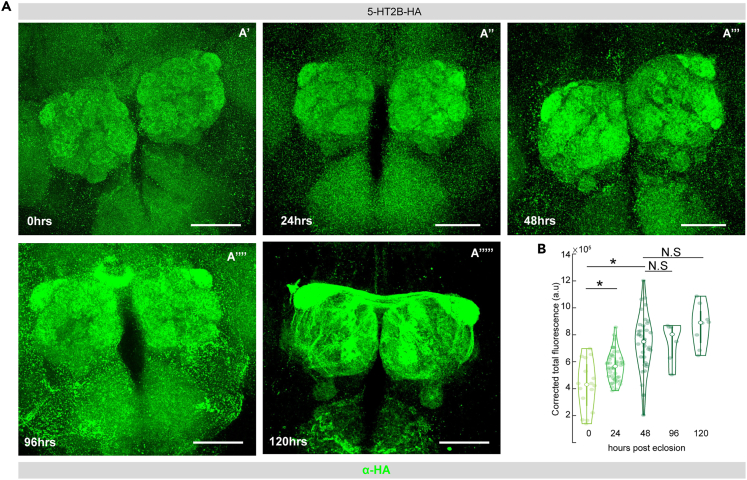

We also observed glomerulus specific differences in the expression levels of the 5-HT2BRs. (Figures S2A–S2I). Therefore, to determine if expression of the 5-HT2BRs within the AL varies post-eclosion, we employed the 5-HT2BR-HA-tagged recombinant flies. We found that the expression of the 5-HT2BRs increases significantly post-eclosion and reaches its peak at day 2 or 48 h post-eclosion (Figures 6A and 6B), which coincides with the closing of the critical period.21,27 After day 2, the 5-HT2BR expression does not vary significantly, as we saw no difference in the corrected total fluorescence between day 2, day 4, and day 5 post-eclosion. Taken together, these results show that 5-HT targets both excitatory and inhibitory neurons within the antennal lobe via distinct receptors.

Figure 6.

5-HT2BR expression in the AL varies during the critical period

(A) 5-HT2B expression levels in the AL as indicated by HA staining in green at different life stages of the fly post eclosion: 0 h or freshly eclosed (A′) 24 h (A″), 48 h (A‴), 96 h (A‴’), and 120 h (A‴’’).

(B) Total corrected cell fluorescence indicating 5-HT2B expression levels in the AL of the fly at different ages from left to right: 0 h or freshly eclosed, 1 day or 24 h post-eclosion (p.e.), 2 days or 48 h p.e., 4 days or 96 h p.e., and 5 days or 120 h p.e.∗∗ indicates p < 0.05; N.S indicates p > 0.05. The scale bar indicates 50 μm in all cases. n ≥ 15. All violin plots include individual data points (colored circles) and mean (white circle). The boxplot of the data is also represented at the center of the violin. Detailed genotypes of flies for each experimental condition can be found in Table 1 and the antibody concentrations used in Table 2.

Autoregulation of serotonergic neurons during the critical period

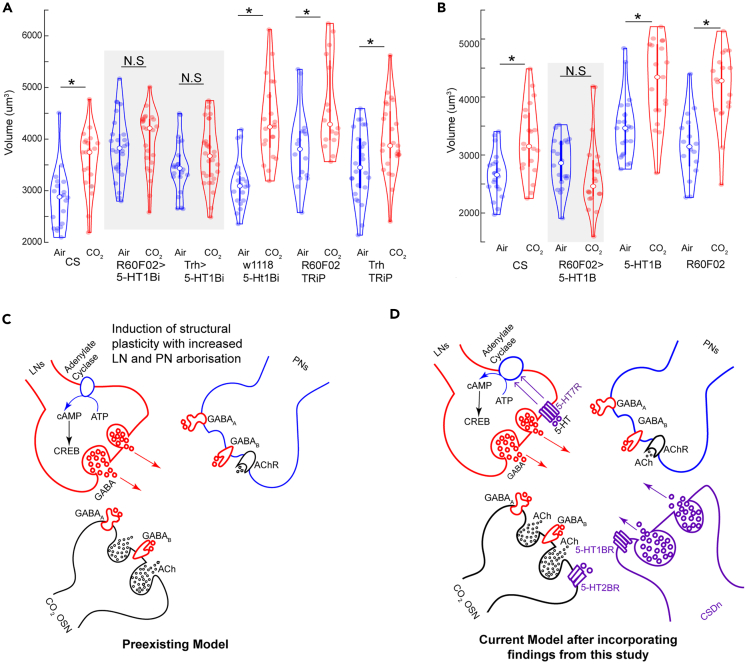

Finally, we sought to determine the neurons for whom expression of the 5-HT1BR is required for the olfactory CPP. Within serotonergic neurons, the 5-HT1BRs often act as auto receptors by either inhibiting the release of 5-HT71,72,73,74 or modulating serotonin reuptake by upregulating SERT activity and clearance rate.75 Therefore, we knocked down 5-HT1B receptors in the CSDns, release of 5-HT from which is required during critical period (Figure 7A). We found that 5-HT1B signaling in CSDns is required for glomerular-specific volume increase during the critical period. Similarly, knocking down 5-HT1BRs in all serotonergic neurons in the brain using a Gal4 promoter line Trh-Gal4 was able to block CPP in the V-glomerulus (Figure 7A). The CSDns release 5-HT upon activation. Since the 5-HT1BRs are inhibitory in nature, activation of 5-HT1BRs on CSDNs will inhibit 5-HT release from them. We also know that release of 5-HT from the CSDns is important during the critical period. Therefore, if we overexpress 5-HT1BRs in the CSDns, there will be a stronger inhibition in the CSDns most likely preventing CPP. Consistent with our hypothesis, we saw that 5-HT1BR overexpression on CSDNs prevents CPP in the V-glomerulus following CO2 exposure (Figure 7B). Together, these results indicate that 5-HT levels need to be tightly controlled to induce CPP.

Figure 7.

Serotonergic signaling during the critical period

(A) Quantification of V glomerulus volumes comparing air- and 5% CO2-exposed flies during the critical period. Six genotypes are shown here from left to right: CS (Canton-S wildtype), R60F02>5-HT1Bi (RNAi knockdown in CSDns), Trh>1Bi (5-HT1B knockdown in all serotonergic cells), w1118,5-HT1Bi (background control for Gal4), R60F02, TRiP (background control for 5-HT1B-RNAi crossed with CSDn line), and Trh, TRiP (background control for 5-HT1B-RNAi crossed with Trh line).

(B) Quantification of V glomerulus volumes comparing air- and 5% CO2-exposed flies during the critical period. Four genotypes are shown here from left to right: CS (Canton-S wildtype), R60F02>5-HT1B (overexpression of 5-HT1B in CSDns), 5-HT1B (control for UAS), and R60F02 (control for Gal4).

(C) During the critical period, chronic odor exposure leads to OSN-dependent activation of LNs and PNs. Activation of GABAergic LNs induces GABA release that modulates OSN and PN responses. cAMP-dependent mechanisms in GABAergic LNs lead to CREB-dependent gene transcription that promotes structural plasticity in the LN and PN arbors, resulting in glomerulus-specific volume increase.

(D) Our results (in pink) show 5-HT also plays a role within the existing model of CPP. 5-HT is released from the CSDNs and is tightly regulated by 5-HT1BRs during the critical period. Differential expression of 5-HT2BR neurons on the OSNs regulates structural plasticity in the LNs and PNs. 5-HT7-mediated GABAergic LN activation interacts with the preexisting model of cAMP-dependent gene transcription to facilitate CPP. GABAergic signaling from the LNs modulate global OSN activation levels during the critical period. ∗ indicates p < 0.05; N.S indicates p > 0.05. n ≥ 15, and gray boxes indicate experimental fly lines in all cases. All violin plots include individual data points (colored circles) and mean (white circle). The boxplot of the data is also represented at the center of the violin. Detailed genotypes of flies for each experimental condition can be found in Table 1 and the antibody concentrations used in Table 2.

Discussion

There are many cellular and molecular components that contribute to CPP. Serotonin is elegantly positioned to affect CPP because a diverse set of 5-HT receptors are broadly expressed throughout the network. The genetically accessible olfactory circuit of Drosophila allowed us to isolate the effects of serotonergic modulation in the critical period exclusively within the olfactory circuit via regulating serotonin release from the CSDns and selectively knocking down 5-HTRs in specific cell types within the olfactory circuit. We first showed that 5-HT is required to induce structural plasticity following chronic odor exposure. Second, we showed that three out of the five 5-HTRs are required for CPP in different neurons. Although 5-HT7Rs are required on a specific subset of LNs that mediate cAMP-dependent structural plasticity during the critical period, the 5-HT2BRs are required in the cognate OSNs, and their expression within the OSNs gradually increases post-eclosion and reaches its peak at the end of the critical period. Furthermore, 5-HT1BRs are required in the serotonergic neurons CSDns. Finally, using SSRIs, we were able to induce structural plasticity in 6-day-old adults when the critical period is normally closed. These results indicate that 5-HT is necessary to induce CPP, and it differentially modulates both excitatory and inhibitory elements in the olfactory circuit during the critical period.

5-HT modulates inhibitory LN circuits that underlie critical period plasticity

Critical periods are known to be tightly regulated by the maturation of inhibitory circuits. In fact, the emergence and maturation of GABAergic inhibitory local interneurons (LNs) in mammals30,76 are known to improve the signal-to-noise ratio by improving their excitation/inhibition balance30 in visual,77 auditory,29 and somatosensory78 cortices during the critical period. Previous investigations of the olfactory critical period in Drosophila have identified a key role of two distinct inhibitory, GABAergic LN populations (LN1 and LN2) in modulating PN output and structural plasticity upon chronic odor exposure during the critical period.20,27 The LN1 sub-population labeled by the NP1227 Gal4 line showed small, statistically insignificant increments in its dose-response curve during chronic CO2 exposure. In contrast, the LN2 LNs labeled by the NP2426-Gal4 line showed significant increases in its cytosolic Ca2+ upon chronic CO2 exposure during the critical period.27 We identified that 5-HT7R-mediated serotonergic modulation within this circuit activates cAMP-dependent mechanisms of gene expression in LN1 neurons that then induces the volume changes.

The CSDns maintain reciprocal connections with the inhibitory, GABAergic, and glutamatergic LNs within the AL.38 These LNs are critical for network level inhibition in the AL, as they tone down PN output before it reaches the MB and LH.57,79,80,81,82,83,84 Following odor exposure, CSDn inhibits some LN types via 5-HT. In turn, the CSDns are inhibited by both GABAergic and glutamatergic inhibition.41 Thus, the CSDns could modulate network level inhibition in the AL via serotonergic modulation and can themselves undergo inhibition based on the network-wide inhibitory dynamics established by the LNs. While blocking 5-HT release from the CSDns prevented the availability of synaptic 5-HT and thereby CPP, the AL neurons also had access to basal 5-HT levels released by the remaining 108 serotonergic neurons in Drosophila. A prime candidate of basal 5-HT modulation is the 5-HT7R-expressing R70A09 GABAergic LNs we identified to be required during the critical period.44 These R70A09 LNs mediate subtractive gain control in the PNs and thereby downregulate global PN responses.44 Our results indicate that although the basal 5-HT levels are trivial during the critical period, 5-HT7R-mediated modulation of R70A09 is required during the critical period. This implies that these cells are most likely playing a crucial role during the critical period in maintaining the inhibitory tone in the AL that is conducive to structural plasticity during the critical period.

In Drosophila, the Ca2+/calmodulin-sensitive adenylate cyclase rutabaga (rut) acts as a coincidence detector for cytosolic Ca2+ increase and GPCR activation20,85 and converts ATP to cAMP. Rescuing (rut) in LN1 or GABA-expressing glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD-1)-positive neurons in rut2080 mutants was sufficient to reinstate CPP in those flies.20,21 We found almost a complete overlap between 5-HT7-expressing R70A09 LNs and the LN1 neurons. Therefore, we can presume a serotonergic modulation in LN1 and consequently in the R70A09 LNs to be acting via 5-HT7-mediated cAMP increase that results in CREB-dependent gene transcription. Our results show that depleting cAMP while keeping the 5-HT7Rs intact in the R70A09 LNs was sufficient to block CPP. The known organisms across phyla that express 5-HT7, all employ an adenylate-cyclase-dependent mechanism to increase cytosolic cAMP.51,69,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97 Within the LN1 neurons, the adenylate cyclase rutabaga is required for CPP.20,21 It is likely that 5-HT7Rs expressed in these LNs modulate cAMP-dependent gene transcription to facilitate structural plasticity during the critical period. This is also consistent with the known mechanism of 5-HT7R activity, which increases intracellular cAMP levels in Drosophila.69 Future work is required to identify if 5-HT7Rs in Drosophila acts through the adenylate cyclase rutabaga to induce CREB-dependent structural plasticity in the R70A09/LN1 neurons.

5-HT directly modulates excitatory OSNs during the critical period

5-HT can modulate circuits directly by acting through 5-HTRs expressed by neurons in the circuit and/or indirectly by modulating 5-HTRs on neurons that feedback onto the neuronal circuit. Within the AL, we see that in addition to impacting local interactions, 5-HT also directly impacts 5-HT2BRs on OSNs during the critical period, suggesting that there is direct modulation of primary sensory afferents by 5-HT. The differential expression levels exhibited by 5-HT2BRs following eclosion and until the end of the critical period (2 days post eclosion) in the AL is reminiscent of the patchy temporal expression of 5-HT2CRs in the kitten striatal cortex during the visual critical period.33 Since the ORNs are the primary source of 5-HT2BR expression in the AL, it is likely that the 5-HT2BR-mediated serotonergic modulation adapts specifically to the odor environment presented to the fly during the critical period. This explains why knocking down 5-HT2BRs in the CO2-responsive OSNs prevents CPP in its cognate V-glomerulus. These results indicate that lower levels of 5-HT2BR expression are permissive to CPP, whereas higher levels of 5-HT2BR signaling beyond the critical levels achieved at day 2 prevent CPP. Additionally, we found differential, patchy expression patterns of the 5-HT2BRs in distinct glomeruli of the antennal lobe during the critical period and in adults, which could also indicate odor-dependent differential serotonergic modulation within distinct glomerulus in the AL. Future work directly correlating 5-HT2BR expression in individual glomerulus with the induction of CPP can shed light on the exact levels of 5-HT2BR modulation required during the critical period. Since the CO2-sensing OSNs do not undergo structural plasticity during the critical period,27 downstream pathways by which 5-HT2BRs modulate OSNs during the critical period might shed light on how they indirectly affect structural plasticity in the LNs and PNs. The most likely mechanism could be via NMDA-receptor-dependent coincident detection that plays an important role in mediating glomerulus-specific volume increase during the critical period.20,21,27 Thus, 5-HT can differentially modulate distinct glomeruli based on their 5-HT2BR expression levels upon a specific odor encounter during the critical period.

Maintenance of optimum serotonin levels during the critical period

The balance of excitation and inhibition (E/I) within a network is fundamentally important for facilitating critical period plasticity.98,99 Intracellular electrophysiological recordings in mice indicate 5-HT acts by differentially modulating relevant excitatory and inhibitory synapses during the critical period.100 This indicates that 5-HT levels can play an important role in controlling permissive levels of excitation and inhibition during the critical period. Therefore, 5-HT levels and thereby 5-HT release permissive to CPP need to be tightly controlled. Similar effects of dopamine are observed during a critical period of sleep in Drosophila that helps in the proper development of a glomerulus intricately involved with courtship.101 Serotonin neurons are known to be modulated by 5-HT itself via expression of 5-HTRs.69 We show direct evidence of how serotonergic neurons modulate their own release to achieve optimum 5-HT levels through autoregulation. In the larval Drosophila nociceptive circuit, the inhibitory 5-HT1BRs expressed in a pair of serotonergic neurons directly inhibit sensory afferents and facilitate a form of experience-dependent plasticity.102 Similarly, the 5-HT1BRs are expressed by the CSDns,69 and knocking down (Figure 7A) or overexpressing the 5-HT1BR in the CSDns (Figure 7B) prevents CPP. Additionally, knocking down 5-HT1B neurons globally in all serotonergic neurons has the same effect (Figure 7A). The inhibitory nature of the 5-HT1BRs implies that the reduction of 5-HT release is required to facilitate CPP. On the other hand, overexpressing 5-HT1BRs on CSDNs ensures less 5-HT release, and because 5-HT release from the CSDns is required for CPP (Figure 1D), we can conclude that 5-HT levels are carefully regulated during the critical period to maintain permissive levels of E/I balance. This concentration-dependent, bi-directional control allows for the maintenance of an optimal 5-HT level above or below which CPP is hindered.

An alternate mode of action of the 5-HT1BRs on serotonergic cells could be the localization of the serotonin transporters (dSERTs) that promote serotonin reuptake, thereby reducing extracellular 5-HT levels.71,72,74 Further studies are required to confirm if this mechanism holds true for serotonergic modulation of serotonin neurons during the critical period.

Neuronal mechanism of serotonergic modulation in CPP

During the olfactory critical period, chronic activation of the OSNs by an odor leads to activation-dependent structural plasticity in the cognate glomerulus. This increase in volume can be attributed to the increase in PN and LN arborizations in an odor-specific manner.19,20,21,27 In a specific subpopulation of GABAergic LNs, the LN1 neurons, the adenylate cyclase rutabaga increases cAMP levels to promote CREB-dependent gene transcription. This facilitates the structural plasticity observed in both the LNs and PNs.20 Functionally, it leads to an increase in inhibitory output and a decrease in excitatory PN output onto the higher order olfactory centers. This mechanism suggests a way by which the primary olfactory center modulates sensory output before it can reach the second-order olfactory centers (Figure 7C). Our observations show that serotonergic modulation integrates at multiple levels of this model to modify the output from the AL. Firstly, 5-HT release from the CSDns within this circuit is required for the structural plasticity. Additionally, 5-HT levels in the extracellular space are maintained by 5-HT1BR-mediated inhibition of serotonergic neurons. Similarly, serotonergic modulation on the OSNs is tightly controlled where lower levels of 5-HT2BR expression permit structural plasticity while higher levels of 5-HT2BR expression achieved 2 days post-eclosion coincide with the end of the critical period. The 5-HT7Rs on the R70A09 LNs and therefore the LN1 neurons likely activate cAMP-dependent gene transcription that ultimately leads to the increase in LN and PN arborizations, resulting in glomerular volume increase (Figure 7D). It is still unclear how 5-HT release from the CSDns gives rise to glomerulus-specific plasticity. The most logical explanation supported by prior literature relies on coincidence detection. Simultaneous activation of OSNs and LNs in the same glomerulus imparts glomerular specificity, which is then modulated by 5-HT2BRs on OSNs. Future experiments are required to examine this model at a greater detail at the cellular and molecular level using pharmacology and electrophysiology.

In conclusion, our work provides insight into how 5-HT modulates structural plasticity at multiple sites of primary olfactory processing during the olfactory critical period. Specifically, we show that 5-HT directly affects the stimulus specific circuit via 5-HT2BRs on the OSNs and 5-HT7Rs on LNs, which indirectly modulates GABAergic inhibition throughout the AL. We also show that 5-HT release from the CSDns is carefully controlled during the critical period, disruption of which hinders CPP. This supports the view that neuromodulators affect different components of sensory processing to facilitate structural plasticity during the critical period.

Limitations of this study

We should note that we tested the effect of 5-HT on a limited number of cell types within the antennal lobe that we hypothesized to be involved in critical period plasticity within the context of the CO2-sensing circuit. Future experiments are required to test the effects of serotonergic modulation on other cell types like PNs and other LN subtypes during the critical period on olfactory processing. Additionally, here we showed the effects of 5-HT on the V-glomerulus that increases in size in response to its cognate odor during the critical period. However, there are other glomerulus like the VM7 that shows OSN retraction and a volume decrease in response to odor exposure during the critical period. It will be interesting to note how 5-HT differentially modulates such glomeruli.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and fulfilled by the lead contact, Andrew M. Dacks (amd358@case.edu).

Materials availability

All plasmids and flies generated in this study have been deposited to Addgene and Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, respectively. The accession number to order these reagents can be found in the key resources table.

Data and code availability

-

•

All raw confocal data are available upon request from the lead contact.

-

•

All codes to plot the figures and analyze data were written in MATLAB and available from the lead contact upon request.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Eric Horstick for helpful feedback on the manuscript and Jonathan Schenk and Marryn Bennett for technical guidance. We thank Dr. Ricardo Areneda for hosting parts of these experiments. We also thank Dr. Jing Wang, Dr. Jill Wildonger, Dr. Herman Dierick, and Dr. Benjamin White for providing us with different transgenic flies. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R21DC018945-01 to Q.G., R01 DC016293 to A.M.D. and Q.G., and NSF IOS 2114775 to A.M.D. We thank A.E. Beaven and the UMD Imaging core facility for confocal imaging. Purchase of the Zeiss LSM 980 Airyscan 2 was supported by Award Number 1S10OD025223-01A1 from the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, A.M., H.L.T., A.M.D., and Q.G.; methodology, H.L.T., A.M.D., and Q.G.; validation, A.M., J.M.E., H.L.T., C.M.J.N., and O.M.C.; formal analysis, A.M., J.M.E., H.L.T., C.M.J.N., and O.M.C.; investigation, A.M., J.M.E., H.L.T., C.M.J.N., and O.M.C.; resources, H.L.T., A.M.D., and Q.G.; data curation, A.M., H.L.T., A.M.D., and Q.G.; writing—original draft, A.M., A.M.D., and Q.G.; writing—review & editing, A.M.D. and Q.G.; visualization, A.M., H.L.T., Q.G., and A.M.D. ; supervision, Q.G. and A.M.D.; project administration, Q.G. and A.M.D.; funding acquisition, Q.G. and A.M.D. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| anti-hemagglutinin (HA) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 26183; RRID: AB_2533049 |

| anti-5-HT | Immunostar | 20080; RRID: AB_572263 |

| anti-reconstituted GFP | Sigma | G6539; RRID: AB_259941 |

| anti-GFP | Abcam | ab13970 ; RRID: AB_300798 |

| anti-Bruchpilot | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) | nc82; RRID: AB_2314866 |

| anti-N-Cadherin (n-cad) | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) | DN-Ex #8; RRID: AB_528121 |

| anti-chicken Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-11039; RRID: AB_2534096 |

| anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-11004; RRID: AB_2534072 |

| anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 546 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-10040; RRID: AB_2534016 |

| anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 633 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A-21050; RRID: AB_2535718 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| DH5α competent cells | Thermo Fisher Scientific | EC0112 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Ampicillin | Thermo Fisher Scientific | J60977.06 |

| Fluoxetine Hydrochloride | Sigma Aldrich | 56296–78-7 |

| Escitalopram Oxalate | Sigma Aldrich | 219861–08-2 |

| Triton-X 100 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | A16046.AE |

| Formaldehyde | Sigma Aldrich | 252549 |

| Normal Goat Serum | Thermo Fisher Scientific | PCN5000 |

| Vectashield Antifade Mounting Medium | Vector Laboratories | H-1000-10 |

| Tris-Cl | Invitrogen | 15568025 |

| NaCl | Sigma Aldrich | S3014 |

| EDTA | Sigma Aldrich | M5755 |

| Proteinase K | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 25530049 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Rapid DNA Ligation Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | K1422 |

| NucleoSpin Plasmid Mini kit | Macherey-Nagel | 740588.250 |

| pTwist Amp | Twist Bioscience HQ, CA | |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Gr21a-Mmus\Cd8a.GFP | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC) | 52619 |

| R60F02-Gal4 | BDSC | 48228 |

| 10x-UAS-IVS-mCD8::GFP | BDSC | 32185 |

| UAS-Vmat-RNAi | BDSC | 44471 |

| Canton-S | BDSC | 64349 |

| w1118 | BDSC | 5905 |

| P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP}attP2 | BDSC | 36303 |

| TI{GAL4}5-HT1A[Gal4] / TI{GAL4}5-HT1A [Gal4] | BDSC | 86275 |

| TI{GAL4}5-HT1B[Gal4]/ TI{GAL4}5-HT1B [Gal4] | BDSC | 86276 |

| TI{GAL4}5-HT2A[Gal4]/ TI{GAL4}5-HT2A [Gal4] | BDSC | 86277 |

| UAS-5-HT2B-RNAi | BDSC | 60488 |

| TI{GAL4}5-HT2B[Gal4]/TM3, Sb[1] | BDSC | 86278 |

| P{y[+t7.7]=CaryP[attp40] | BDSC | 36304 |

| TI{GAL4}5-HT7[Gal4] | BDSC | 86279 |

| 5-HT1A-7×GFP11-HA | This study. BDSC | 605059 |

| 5-HT1A-(MI1140)-T2A-GAL4 | Gift from Dr. Herman A. Dierick | |

| 10×UAS-mCD8-GFP | BDSC | 32189 |

| MiMIC 5213 HT1B T2A Gal4 | Gift from Dr. Herman A. Dierick | |

| 5-HT1B-7×GFP11-HA | This study. BDSC | 605060 |

| 10×UAS-mCD8-GFP | BDSC | 32186 |

| 5-HT2A-(MI459)-T2A-Gal4 | Gift from Dr. Herman A. Dierick | |

| 5-HT2A(BFH)-7×GFP11-HA/TM6B, Tb[1] | This study. BDSC. | 605061 |

| 5-HT2B-(MI6500)-T2A-Gal4 | Gift from Dr. Herman A. Dierick | |

| 5-HT2B-7×GFP11-HA | This study. BDSC. | 605063 |

| 5-HT7-(MI215)-T2A-Gal4 | Gift from Dr. Herman A. Dierick | |

| 5-HT7-7×GFP11-HA | This study. BDSC. | 605066 |

| GMR70A09-GAL4 | BDSC | 47720 |

| 10xUAS-sfGFP1-10 (VK00027) | Gift from Dr. Jill Wildonger | BDSC# 93189 |

| NP1227-Gal4 also known as LN1-Gal4 | Drosophila Genomics Resource Center (DGRC) | 103945 |

| 10XQUAS-6XmCherry-HA | BDSC | 52269 |

| GMR70A09Q | Dr. Quentin Gaudry. Suzuki et al., 2020 | |

| NP2426-Gal4 also known as LN2-Gal4 | DGRC | 104198 |

| UAS-mCherry | BDSC | 59021 |

| QUAS-mCD8-GFP | BDSC | 30002 |

| UAS-5HT7-RNAi | BDSC | 32471 |

| P{y[+t7.7] =CaryP}attp2 | BDSC | 36303 |

| w, UAS-dunce; +; + | Gift from Dr. Benjamin White | |

| UAS-GABAB-RNAi; UAS-GABAB-RNAi | Gift from Dr. Jing Wang | |

| Peb-Gal4 | BDSC | 80570 |

| UAS-Rdl-RNAi | BDSC | 52903 |

| Orco-Gal4 | BDSC | 26818 |

| Gr21a-Gal4 | BDSC | 23890 |

| Gr63a-Gal4 | BDSC | 9943 |

| UAS-5-HT1B-RNAi | BDSC | 51842 |

| Trh-T2A-Gal4 | BDSC | 84694 |

| UAS-5-HT1B | BDSC | 27632 |

| 5-HT7-Gal4 | Gift from Dr. Charles D. Nichols | |

| MZ19-Gal4 | BDSC | 34497 |

| Or56a-Gal4 | BDSC | 23896 |

| Or23a-Gal4 | BDSC | 9956 |

| Or47a-Gal4 | BDSC | 9982 |

| Or13a-Gal4 | BDSC | 9945 |

| Or67c-Gal4 | BDSC | 24856 |

| Or67d-Gal4 | BDSC | 23906 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| gRNA sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1A: gaccagtccactaccgcagc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA1 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: aatttcgacgggccttcaag | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA2 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: gaaaatttgatttcaactga | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA1 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2A isoform A: catattcaatcgcacgttcc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA2 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2A isoform A: ttcgaggtgccttcgtcggt | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA1 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2A isoform D: tccttctggcgcaaacacgg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA2 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2A isoform D: ctgaagacataattacgtgg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA1 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2A isoform B, F and H: cgctatcggtctgtgacaga | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA2 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2A isoform B, F and H: ggaaaagccgctaattacag | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA1 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2B: aggcactcgtgctcgaatag | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA2 sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2B: ttcagtttgcccggtttaac | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| gRNA sequence for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 1× and 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT7: ggcgagggagagctttctct | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1A: aattatgctAGCTAGAGGACCAGGACGAGC | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1A: ccatcgccgagcttcccgctGCGGTAGTG | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1A: ccagattacgcttaaAGCGGaAAGCTCTAGATAGTGC | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1A: aattgcggCCGCTGGTCGGTTTAGCAGAAG | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the insert fragment for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1A: agcgggaagctcggcgatggaggaagcg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the insert for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1A: GCTTtCCGCTttaagcgtaatctggaacatcgtatggg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: taattatgctagcgatgcggatgatgtaagta | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: ctccatcgccggaaattttcgcactgcgcgctc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: ccagattacgcttaatgaagaataacgaggaccagtatttg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: ataattgcggccgcatacatgtgcataccgaag | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the insert fragment for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: gcgaaaatttccggcgatggaggaagcgg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the insert for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: cctcgttattcttcattaagcgtaatctggaacatcgtatggg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: gccttcaagagAattctcttcgg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT1B: ccgaagagaatTctcttgaaggc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2A isoform D: aattatgctagccattgtttgggtaatggccatg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform D: CCATCGCCgtacctgtccattaggtttggatagccg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform D: GCTTAACTCTAGACCtaataggaaaacacctgaagacataattacg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform D: taattgcggCCgcttcaatgggggacctctgag | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the insert fragment for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform D: ctaatggacaggtacGGCGATGGAGGAAGCGGAG | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the insert for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform D: ggtgttttcctattaGGTCTAGAGTTAAGCGTAATCTGGAAC | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 1 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform D: gcaaacacggcgCctatccaaacc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 1 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform D: ggtttggatagGcgccgtgtttgc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 2 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform D: gacataattacgtggtgCtgacttactgc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 2 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform D: gcagtaagtcaGcaccacgtaattatgtc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2A isoform B, F and H: aattatgctagctgagtaacgggtatctgacag | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform B, F and H: ccatcgccgcactcgtcgtctgtgactgtg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform B, F and H: cgcttaactctagacctgaaccacgaggagcaccatc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform B, F and H: tataattgcggccgctcggaaacgcttccttctgc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the insert fragment for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform B, F and H: cgacgagtgcggcgatggaggaagcggag | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the insert for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform B, F and H: ctcgtggttcaggtctagagttaagcgtaatctggaac | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 1 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform B, F and H: ctgtgacagaagCacgcggc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 1 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform B, F and H: gccgcgtGcttctgtcacag | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 2 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform B, F and H: cagaaacaaaacggagtTcactgtaattagc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 2 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2A isoform B, F and H: gctaattacagtgAactccgttttgtttctg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT2B: AATATTCTAGATCCTCCGCAGAAGGCG | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2B: ccatcgccgagTCTGCTCGGTCGCCAGGCAC | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2B: gattacgcttaaTAACAGACGACCGTTAAACCGGGC | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2B: ataattgcggccGCAGCACATTCGAAACTTTCATCCG | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the insert fragment for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2B: CCGAGCAGActcggcgatggaggaagcg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the insert for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2B: ttataaGGTACCCGGTTTAACGGTCGTCTG | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 1 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2B: GTCCTGCTGTGTCGCTATTCGAGC | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse mutagenesis primer for silencing the PAM motif 1 for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT2B: GCTCGAATAGCGACACAGCAGGAC | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5-HT7: aatatagctagccactgtagtgggcaatgtcc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the left donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT7: ctccatcgccgagaaagctctccctcgccccgtg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT7: ccagattacgcttaactctagaccatccacgaggacctcc | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the right donor arm for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT7: taattgcggccgcagggggctgggtatttac | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Forward primer for amplifying the insert fragment for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT7: gggagagctttctcggcgatggaggaagcg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Reverse primer for amplifying the insert for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in of 7×GFP11-HA into 5- HT7: ggtctagagttaagcgtaatctggaacatcgtatgggtaactagtaatgccagctgcg | Eurofins Genomics | N.A. |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pTwist Amp | Twist Bioscience HQ, CA | |

| pTwist Amp_d5-HT7R-7xsfGFP11-HA-HDR-donor | This study | Addgene # 221818 |

| pTwist Amp_d5-HT7R-sfGFP11-HA-CRISPR-HDR-donor | This study | Addgene # 221819 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA-d5-HT1AR | This study | Addgene # 221820 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA1-d5-HT1BR | This study | Addgene # 221821 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA2-5-HT1BR | This study | Addgene # 221822 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA1-5-HT2AR-isoformD | This study | Addgene # 221823 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA2-5-HT2AR-isoformD | This study | Addgene # 221824 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA1-5-HT2AR-isoformBFH | This study | Addgene # 221825 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA2-5-HT2AR-isoformBFH | This study | Addgene # 221826 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA1-d5-HT2BR | This study | Addgene # 221827 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA2-d5-HT2BR | This study | Addgene # 221828 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA-d5-HT7R | This study | Addgene # 221829 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA1-for-dSERT | This study | Addgene # 221830 |

| pdU6-2_sgRNA2-for-dSERT | This study | Addgene # 221831 |

| pTwist Amp_d5-HT1AR-7xsfGFP11-HA-HDR-donor | This study | Addgene # 221832 |

| pTwist Amp_d5-HT2BR-7xsfGFP11-HA-HDR-donor | This study | Addgene # 221833 |

| 13xLexAop2 IVS sfGFP1-10 | This study | Addgene # 221834 |

| pTwist Amp_2xFlag-dSERT-HDR-donor-HDR | This study | Addgene # 221835 |

| pACUH 5-HT7R-7xGFP11-HA | This study | Addgene # 221836 |

| pTwist Amp_d5-HT1BR-7xsfGFP11-HA-HDR-donor | This study | Addgene # 221837 |

| pTwist Amp_d5-HT2AR(isoformD)-7xsfGFP11-HA-HDR-donor | This study | Addgene # 221838 |

| pTwist Amp_d5-HT2AR(isoformBFH)-7xsfGFP11-HA-HDR-donor | This study | Addgene # 221839 |

| pACUH 5-HT2BR-7xGFP11-HA | This study | Addgene # 221840 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | https://imagej.net/ij/ | |

| Other | ||

| Glass slides | VWR | 16004-422 |

| Glass coverslips, 25×25 mm | VWR | 48366-089 |

| Glass coverslips, 18×18 mm | VWR | 48366-045 |

Experimental model and study participant details

In this study we have employed female Drosophila melanogaster as a model system. Male Drosophila also undergoes critical period plasticity.27 The specific genotypes of the flies in the figures can be found in Table 1. Information about fly rearing, maintenance, specific experimental conditions can be found in the relevant sections below.

Method details

Fly rearing and maintenance

All Drosophila lines were raised in sparse cultures on cornmeal, yeast, dextrose medium103 at 25°C in a 12hour light/dark cycle unless otherwise noted. The fly lines used in this study can be found in Tables 1 and S1. We used female flies for our studies, except where specifically mentioned. Flies used in the CO2 and air exposure experiments were raised at 25°C until the 4-day old pupae stage and at 23°C until they were sacrificed.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor (SSRI) Treatment

For treatments with SSRI, fluoxetine hydrochloride (56296–78-7) and escitalopram oxalate (219861–08-2) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. 3mM SSRI containing fly food was made fresh daily as described in Bonanno and Krantz et al., 2023.104 Flies were grown until pupal stage in the same growing media and bottle until 4day old pupae, at which point they were separated into fresh vials of food. On day 5 after eclosion, flies were transferred into food vials containing 3mM fluoxetine or escitalopram and incubated at 25°C overnight. On day 6, flies were transferred into separate food vials containing either SSRI and exposed to either CO2 or air for 4 days at 23°C.

Odor exposure

We employed previously established odor exposure protocol to induce critical period plasticity in the flies21,23 Briefly, 4-day old pupae of relevant genotype were collected into separate vials based on odor-exposure. A fine mesh cheesecloth was secured at the opening of the fly vial to ensure free gaseous exchange. Fly vials were placed in either a temperature-controlled CO2 or regular incubator at 23°C on 12-hour light/dark cycles. Eclosed flies were transferred into clean vials 18-21 hours after the start of odor exposure until day 5 post eclosion when they were collected for dissection and immunohistochemistry. For each of the odor exposure experiments, pupae for all the genotypes including control lines for the Gal4 and RNAi and Canton-S (wild-type) were collected on the same day and odor exposure started at the same time. Pupae of the same genotype were collected from the same stock bottle and separated into odor exposed (CO2) and control (air) vials to ensure consistency in food composition, availability, and conditions. During odor exposure both male and female flies of a specific genotype were present in each vial. Only female flies were collected after cold anesthetizing the flies at the end of the experiment right before dissection.

Plasmid preparation for CRISPR/Cas9 knock-in