Abstract

Background

Continuing medical education in liver transplantation is pivotal in enhancing the proficiency of liver surgeons. The goal of this study is to obtain information on all aspects of the training, enable us to pinpoint the training's strengths, and address any shortcomings or challenges.

Method

We conducted an online questionnaire survey, which was comprised of 33 questions, offering response options in the form of “yes/no”, single choice, or multiple choice.

Results

A total of 59 liver surgeons actively participated in the questionnaire survey. The majority of them exhibited a comprehensive understanding of the liver transplant training program, encompassing its structure, content, and assessment format. It is noteworthy that all respondents expressed keen interest in novel course components such as medical humanities, interpersonal communication, full-process patient management, and scientific research and academic activities. The overall satisfaction with the diverse specialized training courses was notably high. Furthermore, there was a significant improvement in self-confidence among participants for performing relevant clinical practices post-training, signifying the effectiveness of the program. Notably, key determinants influencing physicians' confidence levels before and after training included accumulated clinical practice time, basic operation cases, and educational background.

Conclusion

This survey reveals that trainees possess a commendable grasp of the program, maintain a positive outlook, and gain substantial benefits from the training. Importantly, it underscores the need to enhance the pedagogical skills of professional training instructors, continually refine the curriculum, and serve as a foundation for informed decisions in the ongoing training of liver transplant physicians.

Keywords: Continuing medical education, Liver transplantation, Training program

Highlights

-

•

Most liver surgeons showed strong understanding of the liver transplant program, including its structure, content, and assessment.

-

•

All respondents expressed interest in new course aspects, such as medical humanities, communication, and full-process patient care.

-

•

Participants reported high satisfaction with training and improved confidence in clinical practice, highlighting program success.

Background

Continuing medical education (CME) holds immense significance in the development and growth of healthcare professionals. It enables them to sharpen their skills and enhance their knowledge throughout their careers, ultimately benefitting patients and the overall healthcare system. Medical teaching has been institutionally incorporated within medical schools and teaching hospitals, providing a structured framework for knowledge transfer and skill development among healthcare practitioners [1]. The primary objective of continuing education is to elevate the overall quality and level of applied physicians [2]. By continuously learning and engaging in lifelong education, healthcare professionals can consistently improve the medical services they provide to their patients [3]. In the United States, CME is not only encouraged but mandated in many states to ensure medical professionals maintain their licenses [4]. This has made research in continuing medical education and physician evaluation a national priority. Despite the growing recognition of CME's importance, China is still in the nascent stages of developing specialist education. One of the key challenges faced is the lack of adequate training resources for difficult medical subspecialties, hindering the progression of specialized medical education. Another obstacle in China's continuing medical education landscape is the unappealing and irrelevant training content [5]. Without engaging and relevant material, healthcare professionals may struggle to find motivation and interest in participating in further education [6,7].

End-stage liver disease and early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma are typically managed through liver transplantation [8]. China's contribution to the global liver transplant cases surpasses one-third, as indicated by data from the China Liver Transplant Registry (CTLR) [9]. Therefore, liver transplantation technology holds significant promise and feasibility within our nation. However, within our country, liver transplant procedures are not uniformly distributed, with the majority concentrated in large cities [10]. Additionally, liver transplantation is a complex surgical procedure, and the perioperative management and long-term follow up pose formidable challenges [11]. Therefore, based on the basis of liver surgery, it is necessary to continue re-education in liver transplantation and its perioperative management. This initiative will help improve the skill level of medical professionals to ensure the safety and effectiveness of liver transplant. After three consecutive liver transplant specialist training sessions at Shanghai Renji Hospital, we found that the trained transplant physicians thoroughly understood our curriculum and course structure, and our training had a positive impact on their subsequent development. Therefore, we conducted a survey to assess the physicians' understanding of the courses at Renji Hospital, their satisfaction levels, and their self-assessed confidence.

The Liver Surgery Department at Shanghai Renji Hospital stands as China's largest liver transplant center and holds the status of a national key clinical specialty. Through continuous refinement, the Liver Surgery Department at Shanghai Renji Hospital has successfully established a mature, efficient, and secure pediatric liver transplantation system. In a bid to advance the practice of pediatric liver transplantation in China and disseminate the core techniques of liver transplantation, Shanghai Renji Hospital has taken a pioneering step by establishing a dedicated training base for liver transplant specialists since 2021. This liver transplant training program, focused on pediatric liver transplantation, emphasizes hands-on clinical practice under the guidance of clinical instructors, supplemented by appropriate coursework. It closely integrates with actual clinical work to cultivate clinicians skilled in organ transplantation and enhance their clinical treatment capabilities. The specialized teaching content includes liver transplant techniques, organ donation protocols, and critical care training and practice. The liver transplant module requires managing 15 liver transplant patients and participating in 10 transplant surgeries. The organ donation module involves completing the retrieval, preservation, and transportation of organs from five deceased donors. The critical care training and practice module requires mastering the management of early postoperative complications, early graft function monitoring and maintenance, and supportive treatment for critically ill liver transplant patients. According to data from 2011, 95 % of transplant surgeons in the United States have undergone specialized transplant surgery training. Following the consecutive offering of relevant training courses from 2021 to 2023, this study seeks to survey physicians who have undergone liver transplantation training. It aims to assess the training's actual effectiveness from their unique perspectives, gauge their satisfaction with the training experience, and evaluate the levels of confidence they have before and after the training. This study aims to not only identify the strengths of the training but also pinpoint any shortcomings and challenges associated with the training process, ultimately paving the way for the exploration of more effective training modes.

Methods

We conducted an online questionnaire survey among physicians who participated in liver transplantation training at Shanghai Renji Hospital. The questionnaire was comprised of 33 questions, offering response options in the form of “yes/no”, single choice, or multiple choice. A comprehensive description of the questionnaire was provided at the outset of the survey. The questionnaire was roughly divided into five parts: demographic characteristics, actual understanding of training, interest in training content, satisfaction survey of training, and a self-assessment of training confidence before and after training. Reliability analysis indicated that the questionnaire demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.93).

The survey was conducted online through the “wenjuanxing” platform (https://www.wjx.cn/). We distributed 60 questionnaires to physicians who participated in one of the liver transplantation training sessions held from 2021 to 2023. The survey targeted included physicians who met the following criteria: holding a “Physician Practice Certificate” with a clinical practice category, practicing in surgery or pediatrics (pediatric surgery direction), working in a tertiary hospital; having not been fully or primarily responsible for a Grade II or higher medical accident in the past three years; holding the professional title of attending physician; and having over five years of clinical experience in human organ transplantation or over eight years of related clinical experience in surgery or pediatric surgery. Right at the beginning of the questionnaire, all participants were provided with information about the research objectives, the voluntariness, and confidentiality of the survey. A link to the survey was distributed to all participants via WeChat, and the survey was closed 30 days after publication. The data were collected from August 20, 2023 to September 19, 2023. The collected questionnaires were used in the analysis, and the inclusion criteria comprised specialist physicians who had undergone liver transplantation training at Shanghai Renji Hospital; exclusion criteria excluded respondents who filled in the answers mechanically (e.g., filled in the same answer on each question); respondents who submitted multiple questionnaires from the same Internet Protocol (IP) address (in such cases, only the last questionnaire submitted was considered valid, and the rest were disregarded). Statistical analysis was conducted utilizing SPSS 24.0 software for data analysis. Categorical variables were described in terms of frequency and composition ratios. Furthermore, group comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. A significance level of P ≤ 0.05 was applied to determine statistical significance.

Result

Physicians' demographic characteristics in liver transplantation training program

We initiated our analysis by examining the demographic data from 59 questionnaires. The majority of respondents, accounting for 94.92 %, were male. In terms of age distribution, 49.15 % of the physicians were 30–40 years old, 42.37 % of the physicians were 40–50 years old, and 8.47 % of the physicians were older than 50 years old. Regarding the timing of our training sessions spanning from 2021 to 2023, 25.42 % of physicians received training in 2021, 33.90 % in 2022, and 40.68 % in 2023. In terms of educational qualifications, among the physicians, 1.69 % had a bachelor's degree, 28.81 % had a master's degree, and 69.49 % had a doctor's degree. All participants were affiliated with public hospitals. The majority of physicians, specifically 84.75 %, reported an accumulated clinical practice experience exceeding 3 years. 45.76 % of physicians performed >50 liver surgeries annually. The detailed distribution of information was presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the physicians.

| Demographic characteristic | Frequency | Percent (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male Female |

56 3 |

94.92 5.08 |

| Age | 30–40 | 29 | 49.15 |

| 40–50 >50 |

25 5 |

42.37 8.47 |

|

| Workplace | Jiangsu, Zhejiang or Shanghai | 30 | 50.85 |

| Not Jiangsu, Zhejiang or Shanghai | 29 | 49.15 | |

| Training year | 2021 | 15 | 25.42 |

| 2022 | 20 | 33.90 | |

| 2023 | 24 | 40.68 | |

| Degree | Bachelor degree | 1 | 1.69 |

| Master degree | 17 | 28.81 | |

| Doctor degree | 41 | 71.19 | |

| Job title | Junior | 0 | 0.00 |

| Intermediate | 17 | 28.81 | |

| Senior | 42 | 71.19 | |

| Medical Institutions | Public | 59 | 100.00 |

| Private | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Operation types | General liver surgery | 15 | 25.42 |

| liver transplant surgery | 4 | 6.78 | |

| both | 33 | 55.93 | |

| Other organ transplant surgery | 1 | 1.69 | |

| else | 6 | 10.17 | |

| clinical practice time | ≤3 year | 9 | 15.25 |

| >3 year | 50 | 84.75 | |

| Basic Operation numbers | ≤50 | 32 | 54.24 |

| >50 | 27 | 45.76 |

Physicians' actual understanding of the liver transplantation training program

Subsequently, our investigation primarily focused on trainees, delving into various facets of the situation of the liver transplant training base. These aspects included the management and training system of the base, the frequency of teaching activities, the diversity and volume of diseases encountered, the types and quantities of surgical procedures performed, as well as an overall assessment of the base. Remarkably, an overwhelming majority, constituting 98.31 % of the physicians, possessed a clear understanding of the management and training system of the training base. Additionally, 91.53 % of the physicians believed that the types and quantities of diseases in the training base had fully met the learning requirements, while 8.47 % believed that they had basically met the requirements. Furthermore, an impressive 96.61 % of the physicians believed that the types and quantities of skill operations had fully met the learning requirements, with 3.39 % indicating they basically met their requirements. It's noteworthy that all participants exhibited a comprehensive understanding of the training base's assessment process (Table 2).

Table 2.

Actual understanding of the liver transplantation training.

| Statements | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| The understanding of the management and training system of the training base | ||

| understand | 58 | 98.31 |

| not understand | 0 | 0.00 |

| don't know | 1 | 1.69 |

| The average frequency of teaching activities at the training base | ||

| >8 times/month | 21 | 35.59 |

| 4-8 times/month | 35 | 59.32 |

| <4 times/month | 3 | 5.08 |

| Whether the types and number of diseases at the training base meet learning requirements | ||

| fully achieved | 54 | 91.53 |

| basically achieved | 5 | 8.47 |

| totally not achieved | 0 | 0.00 |

| Whether the types and number of skill operations met learning requirements | ||

| fully achieved | 57 | 96.61 |

| basically achieved | 2 | 3.39 |

| totally not achieved | 0 | 0.00 |

| The understanding of the assessment situation of the training base | ||

| fully understand | 59 | 100.00 |

| basically understand | 0 | 0.00 |

| totally not understand | 0 | 0.00 |

Physicians' interest in liver transplantation training content

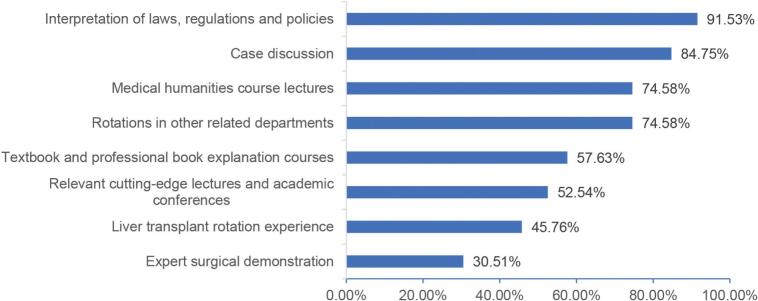

In shaping the future course design of liver transplantation training in Shanghai Renji Hospital, we believed that beyond clinical practice, upcoming medical professionals should play a more extensive role in the complete spectrum of patient management. As shown in Table 3, 100 % of the physicians were interested in the newly added course content such as medical humanities, interpersonal communication, patient management throughout the process, scientific research, and academic activities (Fig. 1). Our liver transplantation training encompasses two primary teaching formats: theoretical instruction and clinical practical skills development. As shown in Table 3, for the theoretical teaching content of our liver transplant training base, 88.14 % of people preferred the combination of online and offline teaching forms, and only 5.08 % and 6.78 % of individuals were satisfied exclusively with online or offline teaching, respectively. Regarding offline teaching, 86.44 % of people were more interested in the technical guidance of clinical technical operations, while only 6.78 % expressed interest in traditionally course-based teaching, and another 6.78 % were inclined towards academic activities. For the form of clinical practice ability training, participants' detailed preferences were shown in Fig. 2. Participants' specific preferences regarding the enhancement of the clinical practice ability training for liver transplantation were illustrated in Fig. 3.

Table 3.

The interest in liver transplantation training content.

| Statements | Frequency | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Are you interested in liver transplant qualification training that includes medical humanities and interpersonal communication, in addition to traditional professional theory teaching? | ||

| fully interested | 59 | 100.00 |

| basically interested | 0 | 0.00 |

| totally not interested | 0 | 0.00 |

| Are you interested in participating in research and academic activities during the liver transplant qualification training? | ||

| fully interested | 59 | 100.00 |

| basically interested | 0 | 0.00 |

| totally not interested | 0 | 0.00 |

| Are you interested in focusing more time on the comprehensive management of patients and various clinical practices in liver transplant qualification training, in addition to surgeries? | ||

| fully interested | 59 | 100.00 |

| basically interested | 0 | 0.00 |

| totally not interested | 0 | 0.00 |

| Preferred teaching format for liver transplant qualification theoretical training | ||

| Online platform lectures | 3 | 5.08 |

| Offline base lectures | 4 | 6.78 |

| Combination of online and offline | 52 | 88.14 |

| Else | 0 | 0.00 |

| Preferred teaching format for on-site base lectures | ||

| Course teaching | 4 | 6.78 |

| Academic activities | 4 | 6.78 |

| Technical guidance of clinical operations | 51 | 86.44 |

| Else | 0 | 0.00 |

| Preferred format of final assessment | ||

| Final assessment | 6 | 10.17 |

| Process assessment | 6 | 10.17 |

| Combination of both | 47 | 79.66 |

| Else | 0 | 0.00 |

Fig. 1.

The additional training program expected in the future liver transplantation training.

Fig. 2.

The detailed preferences for the form of clinical practice ability training.

Fig. 3.

The detailed preferred enhancement of the form of the clinical practice ability training.

Physicians' satisfaction survey of the liver transplantation training program

Employing the Likert 5-point system, participant satisfaction was categorized into five grades, ranging from 1 to 5 points, representing “very dissatisfied,” “dissatisfied,” “neutral,” “satisfied,” and “very satisfied,” respectively. The teaching content of our liver transplantation training base was structured into three major training sections and six special training courses. In terms of the satisfaction survey for the three major training sections, as outlined in Table 4A, regarding technologies related to liver transplantation, 5.08 % of the people were very dissatisfied, 16.95 % were satisfied, and an overwhelming 77.97 % were very satisfied. Concerning organ donation training and practice, 5.08 % were very dissatisfied, 1.69 % were dissatisfied, 20.34 % were satisfied, and 72.88 % were very satisfied. Regarding intensive care training and practice, 5.08 % were very dissatisfied, 1.69 % was neutral, 25.42 % were satisfied, and 67.80 % were very satisfied. In the case of the six specialized training courses, the majority of respondents were satisfied or very satisfied with the six special courses, and only 3.39 % of the people were very dissatisfied with the six special courses. More detailed information was shown in Table 4B. For the overall training process (Table 4C), a satisfaction survey was administered to physicians, mainly encompassing the training rotation arrangement and plan, training teaching content, training teaching methods, training teaching organization and management, base process assessment plan, and implementation. Impressively, >70 % of the physicians were very satisfied with it, >15 % were satisfied, and only 1.69 % were very dissatisfied. Regarding the effect of training (Table 4D), we assessed the improvement of clinical thinking ability, clinical operation practice ability, scientific research ability, teaching ability, medical ethics and doctor-patient communication ability, and professional planning ability. The results revealed that satisfaction with the improvement of teaching and scientific research ability was relatively low, with only 64.41 % of people being very satisfied. Satisfaction with the improvement of clinical thinking ability and clinical operation practice ability was relatively high, with 71.19 % of people being very satisfied.

Table 4.

The satisfaction survey of the liver transplantation training.

| No | Investigated items | Very dissatisfied N(%) |

Dissatisfied N(%) |

Neutral N(%) |

Satisfied N(%) |

Very satisfied N(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Satisfaction with the three main training modules | |||||

| 1 | Hepatic transplant-related technical training | 3(5.08) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 10(16.95) | 46(77.97) |

| 2 | Organ donation training and practice | 3(5.08) | 1(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 12(20.34) | 43(72.88) |

| 3 | Critical care training and practice | 3(5.08) | 0(0.00) | 1(1.69) | 15(25.42) | 40(67.80) |

| B | Satisfaction with the six special training courses | |||||

| 1 | Microsurgical vascular reconstruction skills for liver transplantation | 2(3.39) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 11(18.64) | 46(77.97) |

| 2 | Advanced laparoscopic liver resection skills | 2(3.39) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 9(15.25) | 48(81.36) |

| 3 | Organ procurement and liver transplant surgical techniques | 2(3.39) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 11(18.64) | 46(77.97) |

| 4 | Clinical practice of organ donation | 2(3.39) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 13(22.03) | 44(74.58) |

| 5 | Clinical practice of critical care medicine | 2(3.39) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 15(25.42) | 42(71.19) |

| 6 | Whole lifecycle management under the MDT model for liver transplantation | 2(3.39) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 14(23.73) | 43(72.88) |

| C | Satisfaction with training plans and arrangements | |||||

| 1 | Training plans and arrangements (rotation module) | 2(3.39) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 10(16.95) | 47(79.66) |

| 2 | Training plans and arrangements (time allocation) | 1(1.69) | 1(1.69) | 1(1.69) | 13(22.03) | 43(72.88) |

| 3 | Teaching ability of mentors (responsibility, theory, practice, problem-solving skills) | 2(3.39) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 10(16.95) | 47(79.66) |

| 4 | Teaching content at the training base | 1(1.69) | 1(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 13(22.03) | 44(74.58) |

| 5 | Teaching methods at the training base | 1(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 12(20.34) | 46(77.97) |

| 6 | Regular organization of medical case discussions and new scientific advances by supervisors | 1(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 12(20.34) | 46(77.97) |

| 7 | Targeted guidance based on assessment feedback by supervisors | 1(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 9(15.25) | 49(83.05) |

| 8 | Department’s emphasis on the training and regular organization of professional skill learning | 1(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 12(20.34) | 46(77.97) |

| 9 | Satisfaction with the scheme and implementation of process and final assessments at the base | 1(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 12(20.34) | 46(77.97) |

| 10 | Satisfaction with monthly income during the training at the base | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 4(6.78) | 17(28.81) | 38(64.41) |

| D | Satisfaction with the training outcomes | |||||

| 1 | Improvement in theoretical medical knowledge | 0(0.00) | 1(1.69) | 1(1.69) | 18(30.51) | 39(66.10) |

| 2 | Improvement in clinical thinking ability | 0(0.00) | 1(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 16(27.12) | 42(71.19) |

| 3 | Improvement in clinical practice ability | 1(1.69) | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 16(27.12) | 42(71.19) |

| 4 | Improvement in research ability | 0(0.00) | 1(1.69) | 2(3.39) | 18(30.51) | 38(64.41) |

| 5 | Improvement in teaching ability | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 2(3.39) | 19(32.20) | 38(64.41) |

| 6 | Improvement in medical ethics and doctor-patient communication skills | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 1(1.69) | 19(32.20) | 39(66.10) |

| 7 | Improvement in career planning | 0(0.00) | 0(0.00) | 1(1.69) | 19(32.20) | 39(66.10) |

Physicians' confidence level and associated variables towards training content before and after training

A 7-point Likert scale was employed to assess physicians' self-confidence in performing relevant specific skills. Each of the seven points was described as follows: “Not confident in performing this skill with guidance”; “Relatively confident in performing this skill with guidance”; “Very confident in performing this skill with guidance”; “Not confident without supervision, but manageable with guidance”; “Relatively confident in performing this skill without supervision”; “Very confident in performing this skill without supervision”, and “Had confidence in teaching this skill” (represented the highest level of confidence). A comparative analysis was conducted on the self-confidence in completing six specialized training courses and the self-confidence in completing the entire process of liver transplantation independently before and after training (Table 5). The self-confidence in laparoscopic liver resection before and after training was the highest, with ratings of 4 (3–6) and 6 (5–7) points, respectively. Conversely, self-confidence in completing the liver transplantation process independently before and after training was the lowest, with initial-training scores of 3 (2–5) and post-training scores of 6 (4–7). This showed that it was extremely necessary to further strengthen the training of liver transplant specialists. In addition, all training courses significantly improved students' confidence in performing relevant operations (p < 0.001).

Table 5.

Confidence level before and after training.

| Special courses | Self-reported level of confidence before training Median(IQR) |

Self-reported level of confidence after training Median(IQR) |

Wilcoxon's Z | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microsurgical vascular reconstruction for liver transplantation | 4(2-5) | 6(4-7) | -6.27 | <0.001 |

| Laparoscopic liver resection | 4(3-6) | 6(5-7) | -5.74 | <0.001 |

| Organ procurement and liver transplant surgical techniques | 4(2-6) | 6(4-7) | -6.09 | <0.001 |

| Clinical practice of organ donation | 3(2-5) | 6(5-7) | -5.82 | <0.001 |

| Clinical practice of critical care medicine | 3(2-5) | 6(5-6) | -6.22 | <0.001 |

| Whole lifecycle management under the MDT model for liver transplantation | 3(2-5) | 6(5-7) | -6.22 | <0.001 |

| Independently completing the entire liver transplant surgery process | 3(2-5) | 6(4-7) | -6.14 | <0.001 |

In addition, we grouped the physicians based on demographic characteristics and evaluated the changes in their self-confidence before and after training within different groups. As shown in Table 6, before training, the physicians with accumulated clinical practice time of operation over 3 years had significantly higher self-confidence (p = 0.03), and the physicians with >50 cases of basic operations had significantly higher self-confidence(p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed among the other demographic groups, but the students holding doctoral degrees also had a higher self-confidence than those with a master's degree before training (28 points vs. 17.5 points, p = 0.07). After the training, similarly, the students with cumulative clinical practice time over 3 years had significantly higher self-confidence (p < 0.01), the students with >50 cases of basic operations had significantly higher self-confidence (p < 0.001), with the degree of difference being more pronounced after training. The physicians with a doctor degree also had significantly higher confidence than those with a master's degree or below after the training(p < 0.01). There was no significant difference among the other groups, but the students over 40 years old also had a larger difference in self-confidence than those under 40 years old after the training (42 points vs. 38 points, p = 0.07). Additional specific self-confidence scores and difference analyses were detailed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Association of demographic variables with confidence before and after training.

| Variable | Median Score for overall confidence before training on 7-point Likert Scale Median(IQR) |

Median Score for overall confidence after training on 7-point Likert Scale Median(IQR) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| ≤40 | 21(14.5-37.5) | 38(29-43.5) |

| >40 | 28(16.5-35.25) | 42(36.5-49) |

| Z value | -0.58 | -1.83 |

| P value | 0.56 | 0.07 |

| Workplace | ||

| Jiangsu, Zhejiang or Shanghai | 22(15-39) | 42(30-49) |

| Not Jiangsu, Zhejiang or Shanghai | 27(17-35) | 42(35.5-43.5) |

| Z value | -0.16 | -0.41 |

| P value | 0.87 | 0.68 |

| Training year | ||

| 2021, 2022 | 25(15-36) | 41(34-46) |

| 2023 | 27(15.75-37.25) | 42(30.5-46) |

| Z value | -0.38 | -0.13 |

| P value | 0.71 | 0.90 |

| Education | ||

| Master's degree or below | 17.5(13.75-31.5) | 35.5(28.75-41.25) |

| Doctor degree | 28(16.5-39) | 42(37.5-49) |

| Z value | -1.8 | -3.19 |

| P value | 0.07 | <0.01 |

| Job title | ||

| Medium | 21(13.5-37.5) | 40(31-44) |

| Senior | 28(16.75-35.25) | 42(34-46.75) |

| Z value | -0.91 | -0.95 |

| P value | 0.36 | 0.34 |

| Clinical practice time | ||

| ≤3 years | 13(8-30.5) | 32(26-39.5) |

| >3 years | 27.5(17-37.25) | 42(35.75-47.5) |

| Z value | -2.22 | -2.75 |

| P value | 0.03 | <0.01 |

| Basic Operation numbers | ||

| ≤50 | 16.5(12.25-28) | 34.5(29-41.5) |

| >50 | 35(25-45) | 46(42-49) |

| Z value | -4.12 | -5.01 |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 |

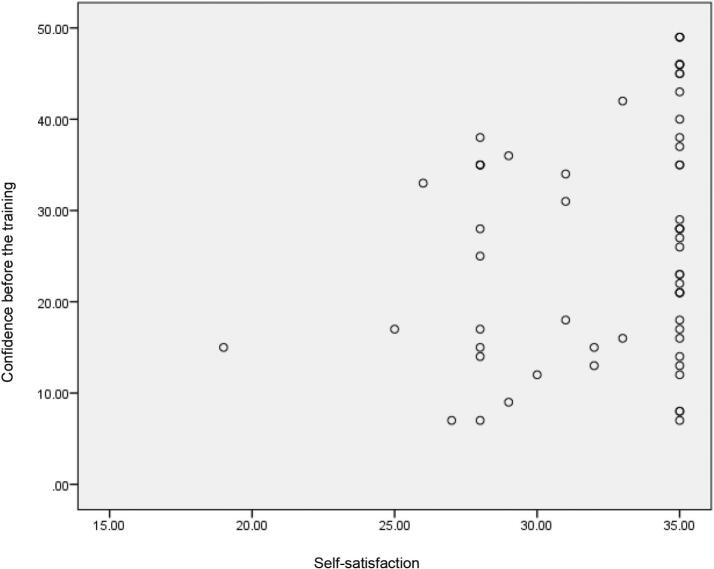

In addition, the correlation between students' self-confidence and their self-satisfaction levels was explored. As shown in Fig. 4 and Fig. 5, there was a certain positive correlation between students' self-confidence and self-satisfaction before and after training, although the p-value of the Spearman correlation test was >0.05. Notably, there was no significant correlation between self-improvement satisfaction and self-confidence before training (r = 0.22, p = 0.1). Similarly, no significant correlation was identified between self-improvement satisfaction and self-confidence after training (r = 0.24, p = 0.06).

Fig. 4.

Correlation between residents' self-assessment confidence before the training and their self-satisfaction.

Fig. 5.

Correlation between residents' self-assessment confidence after the training and their self-satisfaction.

Discussion

Continuing medical education holds immense significance for the ongoing development and advancement of medical professionals. It provides them with opportunities to continually enhance their skills and broaden their knowledge throughout their careers, ultimately benefiting both patients and the entire healthcare system [1]. While liver transplantation has been performed in China for over four decades [10] and has made remarkable progress with the incorporation of new technologies, the current participation rate of continuing medical education programs focusing on liver transplantation remains notably low. As of 2020, the National Health Commission of China has certified only 11 liver transplantation training centers, with a relatively low proportion of trained doctors. In contrast, in the United States, at least 85 % of transplant physicians (146 out of 171) have undergone specialized transplant physician training programs, with an average duration of approximately 1.8 years [12]. Moreover, in the United States, an average of 58.1 transplant training programs were conducted annually between 2007 and 2019, offering 73.1 training opportunities. These programs received an average of 84.9 applicants each year, with approximately 54.0 trainees successfully matched into training positions [13]. Consequently, there is an urgent and compelling need for the further development of liver transplant specialist training programs in China. Shanghai Renji Hospital, as one of the pioneer certified liver transplant training centers, initiated training and re-education for liver transplant specialists from 2021, successfully graduating three batches of trainees from our center. After conducting three consecutive sessions of the liver transplantation specialist training program at Shanghai Renji Hospital, we believe that the trained transplant physicians have developed a solid understanding of our curriculum design and structure. Furthermore, our courses have proven to be highly effective in the subsequent training and development of transplant physicians. Therefore, we surveyed the physicians to evaluate their comprehension of the Renji Hospital transplant courses, their satisfaction with the training, and their self-assessed confidence levels. To assess the educational effectiveness of clinical teaching, we aim to conduct an educational evaluation through questionnaire surveys to optimize the training process [14]. Additionally, due to limited literature on the surgical learning curve, especially in the field of liver transplantation, and most existing work focusing on other medical specialties [15,16], we intend to analyze trainees' confidence levels in performing specialized liver transplantation-related procedures before and after their training. This analysis will help us gauge their progress and facilitate the refinement of their surgical learning curve. Recognizing that our ability to promote surgical education depends, in part, upon our understanding of potential barriers to learning or differences among learners that may not be immediately apparent in the training process, so we consider the potential influence of demographic differences on training outcomes to further optimize our training effects.

The findings of our study indicated that nearly all physicians were well-informed about and content with the various aspects of the training base. This includes the management and training system of the base, the frequency of teaching activities, the diversity and volume of diseases encountered, the types and quantities of surgical procedures performed, and an overall assessment of the training program.

Drawing from a Canadian study's experience, which showed that residents often gathered information from training bases or through word of mouth from friends and colleagues [17], it underscored the importance of clear communication with project leaders before and during the implementation of the training program. This helped address any uncertainties about the competencies' constitution and how they are defined and assessed. Enhancing physicians' understanding of the objectives and regulations of liver transplantation can assist them in identifying their own learning needs and self-regulating themselves during the training process. Therefore, it was essential for administrators, educational leaders, and clinical instructors to take steps to promote and raise awareness about liver transplant training for prospective human organ transplant physicians. This ensured that physicians had access to comprehensive and accurate information before participating in training. Furthermore, administrators, educational leaders, and clinical instructors should provide physicians with career guidance and should assess their skills and abilities to help them develop improvement plans before entering training. This proactive approach increased the chances of successful matching with competency-based training programs. Moreover, future competency-based training requirements could be more explicitly and meticulously outlined.

The results of our survey highlighted that most physicians recognized the importance of including competencies beyond clinical skills in liver transplant training programs. They emphasized the significance of professionalism, communication and teamwork, and a broader understanding of scientific research progress as essential abilities of such programs. This reflected a growing awareness that clinical skills alone are insufficient to meet the demands of daily clinical practice. Studies have indicated that core competencies for healthcare professionals, especially in fields like children's hospice care, encompassed communication skills, personal coping strategies, and teamwork skills. These competencies are vital and should warrant significant attention in training programs [18]. Furthermore, regarding assessment methods, there was a preference for a blended approach that combined both online and offline assessment, as well as a graduation assessment that integrated progress evaluation. This suggested a promising avenue for exploring diverse learning formats. Historically, teaching hospitals in China conducted systematic surveys to gauge residents' perceptions of continuing medical training programs. However, these surveys faced challenges due to the lack of a mature competency framework [19,20]. The unique background of our hepatologist specialty physicians, with their extensive clinical practice and doctor-patient communication experience, has led to high expectations and more interest in such courses. These expectations aligned with the current requirements of organ transplant training curricula. Our next steps should include further refining the organ transplant training program and initiating key measures to establish a national transplant system. Our future training programs will closely focus on the specialized liver transplantation techniques unique to our center, expanding our core specialized training courses. The future curriculum framework will primarily cover six core specialized courses, including microvascular reconstruction skills for liver transplantation, advanced laparoscopic hepatectomy skills, organ procurement and liver transplantation surgical techniques, clinical practice of organ donation, clinical practice of critical care medicine, and whole-life cycle management under the liver transplantation MDT model. This system aims to nurture physicians with expertise, clinical proficiency, ethical grounding, and humanistic values. Achieving uniform quality standards for transplant physicians is a long-term endeavor, likely spanning decades, requiring collaborative efforts from educators, administrators, and the trained physicians themselves.Conducting timely satisfaction surveys is instrumental in obtaining a comprehensive and objective assessment of students' clinical learning outcomes, enabling timely adjustments and guidance [21]. Following the one-year training program, a satisfaction survey revealed that the majority of trainee doctors expressed high satisfaction with various aspects of the liver transplantation training. This outcome strongly suggested that the initial three years of liver transplantation training had been effective and well-structured. Two factors contributed to this success. First, our liver transplant training and education program was highly tailored, encompassing three major sections and six specialized courses that covered the core competencies required for liver surgery physicians. This focused approach allowed trainees to make substantial progress during their training period. Second, our training instructors provided “one-on-one” real-time feedback and coaching to students. This real-time feedback mechanism ensured that trainees received detailed guidance on areas where they might need improvement in diagnosis and treatment. “Real-time feedback” communication served as a catalyst for enhancing students' learning enthusiasm. Moreover, such feedback empowered trainees to set clear goals for their regular training, effectively addressing clinical weaknesses. It essentially created a continuous feedback loop of “feedback-improvement-re-feedback-re-improvement,” forming a spiral process of growth. Looking ahead, our aim is to expand training across multiple disciplines and diverse clinical cases. This approach will expose students to a wide range of liver transplantation-related courses and introduce them to cutting-edge clinical concepts and technologies. Therefore, for future curriculum research, we will continue to follow up with satisfaction surveys and feedback mechanisms to refine the course design from the trainees' perspective, better meeting the clinical needs of transplant physicians.We conducted a comparison of physicians' self-confidence in performing liver transplantation-related procedures before and after the training. These procedures were closely aligned with the content covered in the six specialized training courses. Although some studies had noted that subjective self-assessments could sometimes be influenced by personal bias [22,23], when it came to identifying specific areas of weakness, self-assessments generally proved more effective than assessments by supervisors [24]. Our study revealed that doctors' confidence significantly improved before and after their training, even including their confidence in independently completing the liver transplantation process. This indicated that liver transplantation training playd a valuable role in guiding physicians in their clinical practice. Furthermore, limited information was available on the surgical learning curve, with most research primarily focused on other medical specialties [15,16,23]. Therefore, optimizing the learning curve, particularly in the field of organ transplantation [25], was crucial for ensuring that hepatology specialists consistently deliver high-quality patient care. This was especially important in an environment where new knowledge was rapidly evolving and disseminating. For optimizing the learning curve of future liver transplant surgeons, we plan to enhance the assessment program. Future assessments will not only focus on the technical aspects of transplantation but also include patient management, case analysis, and skill operation examinations in liver transplantation clinical skills. Patient management will be evaluated based on the trainee's daily clinical work at the training base, case analysis will be assessed through written exams to test the trainee's professional knowledge level, and skill operation assessments will cover organ procurement and liver transplantation. The scoring forms for each project will be formulated by the training base. Additionally, in terms of assessments, at least three training instructors will conduct on-site reviews and scoring, with one instructor from another training base, while the trainee's mentor must recuse themselves. We believe that a strict assessment system can help optimize the learning curve for transplant trainees to some extent. The ability to enhance surgical education, as reflected in increased confidence, relied in part on our understanding of potential learning barriers and differences among trained physicians.Our report initially identified three key factors: the number of surgical cases, clinical practice time, and educational background. These factors formed the foundation for early theoretical learning, and clinical experience proved highly beneficial for an in-depth study of liver transplantation. These conclusions prompted us to consider the recruitment of more experienced doctors, including those at the attending level or above, with over five years of experience in human organ transplantation. Additionally, candidates with at least eight years of relevant clinical work experience in surgery or pediatric surgery should be considered for further liver transplant training [26]. In addition, given our department's expertise in pediatric liver transplantation, we will focus on training pediatric surgery physicians. Priority will be given to physicians whose practice scope includes pediatric surgery. Most continuing medical education programs are grounded in the principles of self-directed learning, making subjective evaluations pivotal for guiding one's own learning activities through real-time self-assessment of learning needs [27]. Our aim was to assess the reliability of transplant physicians' self-assessment of clinical skills by examining the correlation between their satisfaction with improvements in their learning abilities and their confidence levels before and after training. The observed correlations of 0.22 and 0.24, respectively, suggested that more detailed scales were needed to evaluate physicians' self-assessment of skill improvement effectively. Following the completion of the hospital-based liver transplant training program, the surveyed physicians engaged in various forms of Continuing Medical Education (CME) to further enhance and update their expertise. These CME activities encompassed regular participation in professional conferences, specialized workshops, webinars, and online courses, enabling physicians to stay abreast of the latest advancements in clinical research and innovative surgical techniques. Moreover, many physicians pursued short-term fellowships and academic exchanges both domestically and internationally, facilitating exposure to cutting-edge practices and fostering interdisciplinary collaboration. This diversity in CME formats ensured that the physicians maintained a high level of professional competence throughout their careers, effectively responding to evolving clinical challenges and patient needs. The ongoing CME not only bolstered the physicians' clinical skills and theoretical knowledge but also significantly enhanced their professional confidence and identity. By continually engaging in education and training, these physicians were better equipped to deliver superior patient care and contribute to the overall advancement of the healthcare system. This commitment to lifelong learning underscores the critical role of CME in sustaining and advancing medical practice.Our study also had certain limitations. Firstly, the data's representativeness was constrained. Our study was confined to the liver transplantation training base at Shanghai Renji Hospital, one of the pioneering liver transplantation training bases in China. Therefore, we recommended that future replication studies be conducted at other liver transplant training centers. Furthermore, physicians' comprehension of liver transplant training should be meticulously assessed to establish a reliable baseline knowledge level, as these responses might be influenced by pre-existing misconceptions related to liver transplantation. Secondly, although we thoughtfully designed and piloted the questionnaire, we didn't explore the underlying factor structures within the questionnaire. However, our intention was not to develop a broadly validated questionnaire instrument for measuring different concepts. Instead, we aimed to encompass all pertinent aspects that require assessment. As pointed out by Schuwirth [28], the value of our assessment questionnaire lay not in the internal structure of the questionnaire or its construct validity, but rather in the correlation of individual items. In other words, each aspect of the evaluation was intended to be meaningful in its own right. In line with this perspective, we diligently endeavored to include all facets we deemed relevant to our study objectives and systematically tailored our questions to cover various facets of liver transplantation training. Thirdly, confidence, being entirely subjective, had been found to be unrelated to objective scores in some other studies [29,30]. Whether this seemingly unrelated trust-competence relationship would have an adverse impact on the liver transplantation learning curve remained uncertain. There were two potential reasons that suggested liver transplant physicians may have limitations in their self-assessment: first, liver surgery, as a distinct surgical field, may lack extensive communication among colleagues regarding medical issues; second, liver transplantation, as a subfield of liver surgery, may not garner significant attention from physicians, making it challenging for them to recognize their own shortcomings and provide accurate self-assessments.

Conclusion

This study highlighted that the three batches of trainees who participated in Shanghai Renji Hospital's liver transplantation training program had a profound understanding of our liver transplant training curriculum, exhibited positive attitudes, and made significant strides. However, it also shed light on the current state of liver transplantation continuing education, which has not yet been widely adopted. Shanghai Renji Hospital, being among the first Chinese liver transplantation training centers, served as a pioneering model. The survey underscored the importance of enhancing the teaching awareness of professional training instructors, continuously refining course structures, and providing a foundation for the training of liver transplantation physicians. Additionally, our research indicated the need for improved self-assessment tools in liver transplantation continuing medical education to make students' self-directed learning more precise and dependable.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Xiaochen Bo: Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. Feng Xue: Visualization, Validation, Project administration, Formal analysis. Qiang Xia: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources. Kang He: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Conceptualization.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for our study was obtained from the Medical Ethical Committee of Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. Informed consent was obtained from all physicians prior to data collection. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declarations of Helsinki and all the selected respondents were given assurance of confidentiality that the information gathered will be used exclusively for research purposes.

Funding

This study was supported by the Project of the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission. (20204Y0012): Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (23ZR1438600), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81972205), and the Project of Shanghai Key Clinical Specialties (shslczdzk05801).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sopen.2024.10.004.

Contributor Information

Qiang Xia, Email: xiaqiang@shsmu.edu.cn.

Kang He, Email: hekang929@163.com.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

STable 1 Association of demographic variables with absolute change of confidence levels before and after training.

Supplementary material

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Ahmed K., Ashrafian H. Life-long learning for physicians. Science. 2009;326(5950):227. doi: 10.1126/science.326_227a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodgers D.J. AOA continuing medical education. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2013;113(4):320–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nissen S.E. Reforming the continuing medical education system. JAMA. 2015;313(18):1813–1814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller S.H., Thompson J.N., Mazmanian P.E., Aparicio A., Davis D.A., Spivey B.E., et al. Continuing medical education, professional development, and requiremen ts for medical licensure: a white paper of the conjoint committee on C ontinuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(2):95–98. doi: 10.1002/chp.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeSilets L.D. The institute of medicine’s redesigning continuing education in the he alth professions. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2010;41(8):340–341. doi: 10.3928/00220124-20100726-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu J., Mao Y. Continuing medical education and work commitment among rural healthcar e workers: a cross-sectional study in 11 western provinces in China. BMJ Open. 2020;10(8) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-037985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ni C., Hua Y., Shao P., Wallen G.R., Xu S., Li L. Continuing education among Chinese nurses: a general hospital-based st udy. Nurse Educ Today. 2014;34(4):592–597. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verna E.C., Patel Y.A., Aggarwal A., Desai A.P., Frenette C., Pillai A.A., et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: management after t he transplant. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(2):333–347. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ling S., Jiang G., Que Q., Xu S., Chen J., Xu X. Liver transplantation in patients with liver failure: twenty years of experience from China. Liver Int. 2022;42(9):2110–2116. doi: 10.1111/liv.15288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mi S., Jin Z., Qiu G., Xie Q., Hou Z., Huang J. Liver transplantation in China: achievements over the past 30 years an d prospects for the future. Biosci Trends. 2022;16(3):212–220. doi: 10.5582/bst.2022.01121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azoulay D., Salloum C., Llado L., Ramos E., Lopez-Dominguez J., Cachero A., et al. Defining surgical difficulty of liver transplantation. Ann Surg. 2023;277(1):144–150. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Florence L.S., Feng S., Foster C.E., III, Fryer J.P., Olthoff K.M., Pomfret E., et al. Academic careers and lifestyle characteristics of 171 transplant surge ons in the ASTS. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(2):261–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alqahtani S.A., Larson A.M. Adult liver transplantation in the USA. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2011;27(3):240–247. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3283457d5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook D.A., Hatala R. Validation of educational assessments: a primer for simulation and bey ond. Adv Simul (Lond) 2016;1:31. doi: 10.1186/s41077-016-0033-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh V., Gress D.R., Higashida R.T., Dowd C.F., Halbach V.V., Johnston S.C. The learning curve for coil embolization of unruptured intracranial an eurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(5):768–771. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ayerdi J., Wiseman J., Gupta S.K., Simon S.C. Training background as a factor in the conversion rate of laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Am Surg. 2001;67(8):780–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curry L., Putnam R.W. Continuing medical education in maritime Canada: the methods physician s use, would prefer and find most effective. Can Med Assoc J. 1981;124(5):563–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claridge J.A., Calland J.F., Chandrasekhara V., Young J.S., Sanfey H., Schirmer B.D. Comparing resident measurements to attending surgeon self-perceptions of surgical educators. Am J Surg. 2003;185(4):323–327. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)01421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lio J., Dong H., Ye Y., Cooper B., Reddy S., Sherer R. Standardized residency programs in China: perspectives on training qua lity. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:220–221. doi: 10.5116/ijme.5780.9b85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Q., Li M., Wu N., Peng X., Tang G., Cheng H., et al. A survey of resident physicians’ perceptions of competency-based educa tion in standardized resident training in China: a preliminary study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):801. doi: 10.1186/s12909-022-03863-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pottier P., Cohen Aubart F., Steichen O., Desprets M., Pha M., Espitia A., et al. Validity and reproducibility of two direct observation assessment form s for evaluation of internal medicine residents’ clinical skills. Rev Med Interne. 2018;39(1):4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2017.10.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marteau T.M., Wynne G., Kaye W., Evans T.R. Resuscitation: experience without feedback increases confidence but no t skill. BMJ. 1990;300(6728):849–850. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6728.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leopold S.S., Morgan H.D., Kadel N.J., Gardner G.C., Schaad D.C., Wolf F.M. Impact of educational intervention on confidence and competence in the performance of a simple surgical task. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(5):1031–1037. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolm P., Verhulst S.J. Comparing self- and supervisor evaluations: a different view. Eval Health Prof. 1987;10(1):80–89. doi: 10.1177/016327878701000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahlawat R.K., Tugcu V., Arora S., Wong P., Sood A., Jeong W., et al. Learning curves and timing of surgical trials: robotic kidney transpla ntation with regional hypothermia. J Endourol. 2018;32(12):1160–1165. doi: 10.1089/end.2017.0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi B.-Y., Liu Z.-J., Yu T. Development of the organ donation and transplantation system in China. Chin Med J (Engl) 2020;133(7):760–765. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorley L., Elcock K. Freedom to learn. Nurs Stand. 2007;21(24):77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schuwirth L. What costs complexity and what price simplicity? Med Teach. 2009;31(6):475–476. doi: 10.1080/01421590802680602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tracey J.M., Arroll B., Richmond D.E., Barham P.M. The validity of general practitioners’ self assessment of knowledge: c ross sectional study. BMJ. 1997;315(7120):1426–1428. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7120.1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fox R.A., Ingham Clark C.L., Scotland A.D., Dacre J.E. A study of pre-registration house officers’ clinical skills. Med Educ. 2000;34(12):1007–1012. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00729.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

STable 1 Association of demographic variables with absolute change of confidence levels before and after training.

Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.