Abstract

Introduction

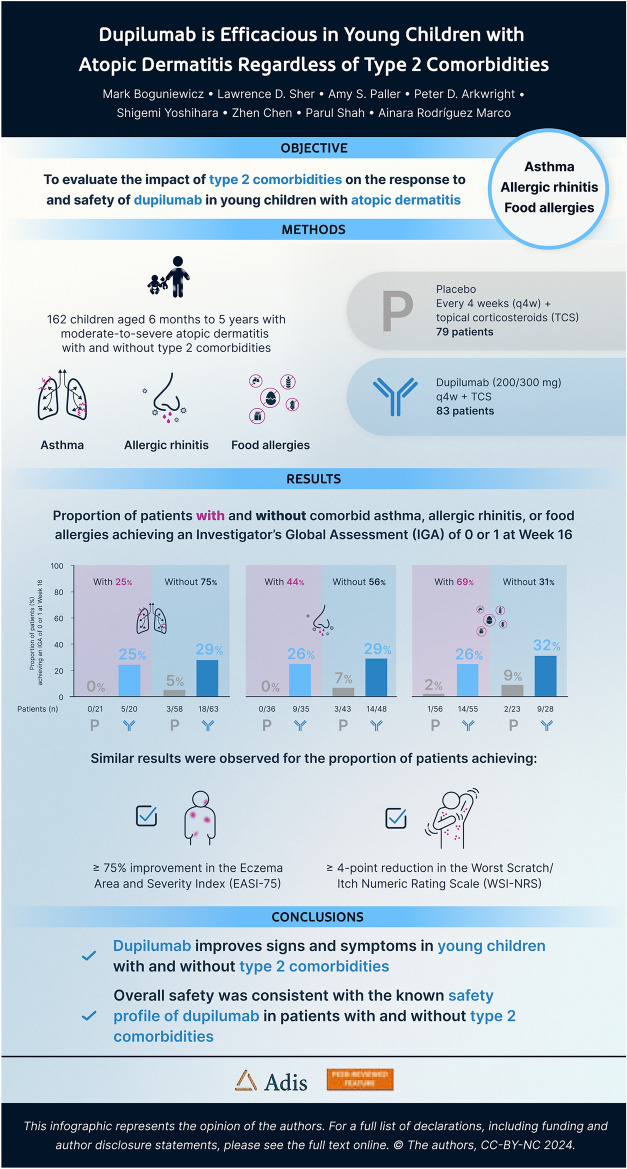

Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) often have other comorbid type 2 inflammatory conditions. The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of type 2 comorbidities on the response to and safety of dupilumab in young children with AD.

Methods

LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B was a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD. In this post hoc analysis, patients were stratified by the presence or absence of caregiver-reported selected type 2 comorbidities at baseline: asthma, allergic rhinitis (AR), and food allergies (FAs).

Results

At week 16, significantly more patients receiving dupilumab versus placebo, with or without asthma and AR, achieved an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0/1 and a ≥ 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index (all p < 0.05). Significantly more patients receiving dupilumab versus placebo with FAs and numerically more patients without FAs achieved an IGA score of 0/1 (p = 0.0007 and p = 0.06). Numerically more patients receiving dupilumab versus placebo with asthma and significantly more patients without asthma achieved a ≥ 4-point reduction in the weekly average of daily score on the Worst Scratch/Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WSI-NRS) (p = 0.6 and p < 0.0001). Additionally, significantly more patients receiving dupilumab versus placebo with or without AR (p = 0.008 and p < 0.0001) and with or without FAs (p = 0.0002 and p = 0.004) achieved a ≥ 4-point reduction in the weekly average of daily score on the WSI-NRS. Overall safety was consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile.

Conclusions

Dupilumab treatment improves AD signs and symptoms in children aged 6 months to 5 years with and without type 2 comorbidities such as asthma, AR, and FAs.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov registration number NCT03346434.

Infographic

Do type 2 comorbidities impact the response to dupilumab in children with atopic dermatitis? (MP4 103,451 KB)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-024-02998-4.

Keywords: Atopic dermatitis, Comorbidities, Dupilumab, Pediatrics, Type 2 inflammation

Plain Language Summary

Patients with atopic dermatitis (AD; also known as eczema) often have other inflammatory conditions as well, including asthma, allergic rhinitis, and food allergies. Like AD, they are all so-called type 2 conditions, caused by similar processes in the body. A drug called dupilumab has been shown to be effective in treating patients with moderate-to-severe AD. This study looked at the results of a clinical trial in which children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD had been treated with either dupilumab or placebo for 16 weeks. The trial results had already shown that at the end of the study, dupilumab compared with placebo resulted in better improvements in their disease and quality of life. In this study, we looked at patients who had only AD, and those who had AD plus one of the other type 2 conditions. We wanted to know if the conditions would impact the response to dupilumab in children with AD. Results showed that dupilumab was better than placebo at reducing the signs and the symptoms of AD in patients, whether or not they also had asthma, allergic rhinitis, or food allergies. Overall safety was consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile. In summary, dupilumab improves the signs and symptoms of moderate-to-severe AD in children aged 6 months to 5 years whether or not they also have another type 2 condition. These results suggest that dupilumab treatment may be effective in children with or without other type 2 conditions.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-024-02998-4.

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a video and infographic, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article, go to 10.6084/m9.figshare.26947120.

Key Summary Points

| The signs and symptoms of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis (AD) and the additional burden of asthma and allergic conditions in children can have a profoundly negative impact on the quality of life of patients, and their caregivers and families. |

| We aimed to evaluate the impact of concomitant type 2 comorbidities on the response to and safety of dupilumab in children with AD aged 6 months to 5 years who had participated in the LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B clinical trial. |

| At week 16, the dupilumab efficacy endpoints—the proportion of patients achieving an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1; a ≥ 75% reduction from baseline on the Eczema Area and Severity Index; and a ≥ 4-point reduction from baseline in the weekly average of daily score on the Worst Scratch Itch Numeric Rating Scale—were similar in patients aged 6 months to 5 years with and without the presence of type 2 comorbidities. |

| The results suggest that dupilumab is effective in reducing the signs and symptoms of AD in patients with and without concurrent type 2 inflammatory comorbidities and could provide a therapeutic benefit for patients with asthma comorbidities. |

| Overall safety was consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile. |

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with an estimated global prevalence of 12% in children aged 6 months to 5 years [1]. Infants and young children with moderate-to-severe AD have a multidimensional disease burden, with skin lesions and symptoms that include intense pruritus and disturbed sleep, which can have a profoundly negative impact on the quality of life (QoL) not only of patients but also of their caregivers and families [2–4]. Infants and young children with AD often have the additional burden of comorbid type 2 inflammatory diseases, including asthma, allergic rhinitis (AR), and food allergies (FAs) [5–7], with estimated prevalences of 16–36% [8–10], 23–33% [8, 11, 12], and 33–56%, respectively [13–15].

Dupilumab is a fully human VelocImmune®-derived monoclonal antibody that blocks the shared receptor component for interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, inhibiting signaling of both IL-4 and IL-13, which are central drivers of type 2 inflammation in multiple diseases [16–19]. Dupilumab is approved for use in pediatric patients aged ≥ 6 months with moderate-to-severe AD, and in pediatric populations with other type 2 conditions, such as asthma and eosinophilic esophagitis [20].

In key clinical trials in adult and pediatric patients with AD, dupilumab has demonstrated significant efficacy and an acceptable safety profile [21–26]. In adult patients with moderate-to-severe AD, phase 3 clinical trials have also shown that dupilumab improves not only the signs and symptoms of AD but also the signs and symptoms of comorbid asthma and sinonasal type 2 inflammatory conditions [27]. Moreover, the efficacy of dupilumab in AD outcomes was shown to be undiminished in subgroups of adults with comorbid asthma or sinonasal conditions [27]. However, the impact of comorbid type 2 conditions on dupilumab efficacy in infants and young children with AD has yet to be established.

In the LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B study, dupilumab with concomitant low-potency topical corticosteroids (TCS) significantly improved AD signs, symptoms, and QoL compared with placebo plus concomitant TCS in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD [26]. We aimed to evaluate the impact of concomitant type 2 comorbidities on the response to and safety of dupilumab in children with AD aged 6 months to 5 years who had participated in LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B.

Methods

Study Design

LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B (NCT03346434) was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 clinical trial in children aged 6 months to 5 years with moderate-to-severe AD whose disease was inadequately controlled with topical therapy, or for whom topical therapy was considered medically inadvisable. The full study design and inclusion and exclusion criteria of LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B have been previously reported [26]. Briefly, patients were randomized (1:1) to receive either subcutaneous dupilumab (200 mg for baseline body weight ≥ 5 kg to < 15 kg; 300 mg for baseline body weight ≥ 15 kg to < 30 kg) every 4 weeks (n = 83), or matched placebo (n = 79), for a 16-week treatment period. All patients received a mandatory standardized, once-daily regimen of concomitant, low-potency TCSs (hydrocortisone acetate 1% cream).

The LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards and ethics committees. For each patient, written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian.

Endpoints

Efficacy endpoints were the proportion of patients achieving an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin) at week 16; the proportion of patients achieving a ≥ 75% reduction from baseline on the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) at week 16; and the proportion of patients achieving ≥ 4-point reduction from baseline in the weekly average of daily score on the Worst Scratch Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WSI-NRS) at week 16.

Safety endpoints were the incidence and severity of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) such as eczema herpeticum, blepharitis, conjunctivitis cluster events (includes all Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities [MedDRA] Preferred Terms [PTs] that include the term “conjunctivitis”, including [but not limited to] allergic conjunctivitis, bacterial conjunctivitis, viral conjunctivitis, giant papillary conjunctivitis, adenoviral conjunctivitis, and atopic keratoconjunctivitis), keratitis cluster events (keratitis cluster includes all MedDRA PTs that include the term “keratitis”, including [but not limited to] keratitis, ulcerative keratitis, and allergic keratitis), and angioedema that occurred during the study period.

Analyses

For this post hoc analysis, patients included in the full analysis set of LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B (all randomized patients) were stratified according to the presence or absence of selected type 2 atopic comorbidities at baseline: with and without asthma, with and without AR, with and without FAs. The presence or absence of type 2 comorbidities was ascertained by caregiver reports.

Categorical endpoints were analyzed using a Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test, after adjustment for randomization strata. Patients who had missing values at week 16 because of use of rescue treatment, withdrawn consent, adverse events (AEs), or lack of efficacy were considered non-responders to ensure accurate analysis of efficacy of dupilumab treatment. Missing data (2.6%) due to any other reason were imputed using multiple imputation.

Continuous endpoints were analyzed using analysis of covariance, with treatment group, stratification factors, and relevant baseline measurements included in the model. Patients who had missing values at week 16 because of use of rescue treatment, withdrawn consent, AEs, or lack of efficacy were imputed using the last observation carried forward. Missing data (2.6%) due to other reasons were imputed using multiple imputation. Statistical significance was calculated for dupilumab versus placebo. All p values reported are nominal, with p < 0.05 considered nominally significant. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) or higher.

Results

A total of 162 patients (83 dupilumab + TCS, 79 placebo + TCS) were included in this analysis, with a mean age of 3.1 (standard deviation 1.2) years; 61% of the patients were male. As previously reported [26], the baseline demographics and disease characteristics for patients included in LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B were similar between the dupilumab and placebo groups. Overall, 161/162 (99%) patients had at least one atopic comorbidity at baseline (41/161 [26%] asthma; 71/161 [44%] AR; 110/161 [68%] FAs) (Table 1). The prevalence of each type 2 comorbidity was similar between the dupilumab and placebo groups.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics, disease characteristics, and comorbidities

| Patient characteristics | Placebo + TCS (n = 79) | Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 83) | Overall (N = 162) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 3.8 (1.3) | 3.9 (1.2) | 3.8 (1.2) |

| ≥ 6 months to < 2 years, n (%) | 5 (6) | 6 (7) | 11 (7) |

| ≥ 2 years to 5 years, n (%) | 74 (94) | 77 (93) | 151 (93) |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 55 (70) | 44 (53) | 99 (61) |

| Age at AD disease onset, n (%) | |||

| < 6 months | 57 (72) | 50 (60) | 107 (66) |

| ≥ 6 months | 22 (28) | 33 (40) | 55 (34) |

| Duration of AD (years), mean (SD) | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.3) |

| Disease characteristics, mean (SD) unless otherwise noted | |||

| Patients with IGA score 3, n (%) (range 0–4) | 17 (22) | 20 (24) | 37 (23) |

| Patients with IGA score 4, n (%) (range 0–4) | 62 (79) | 63 (76) | 125 (77) |

| EASI total score (range 0–72) | 33.1 (12.2) | 35.1 (13.9) | 34.1 (13.1) |

| WSI-NRS score (range 0–10) | 7.6 (1.5) | 7.5 (1.3) | 7.6 (1.4) |

| Placebo + TCS (n = 78) | Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 83) | Overall (N = 161) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients reported to have baseline atopic conditions, n (%) | |||

| Asthma | 21 (26.6) | 20 (24.1) | 41 (25.3) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 36 (45.6) | 35 (42.2) | 71 (43.8) |

| Food allergies | 56 (70.9) | 55 (66.3) | 111 (68.5) |

AD atopic dermatitis; EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index; IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment; q4w every 4 weeks; SD standard deviation; TCS topical corticosteroid; WSI-NRS Worst Scratch/Itch Numeric Rating Scale

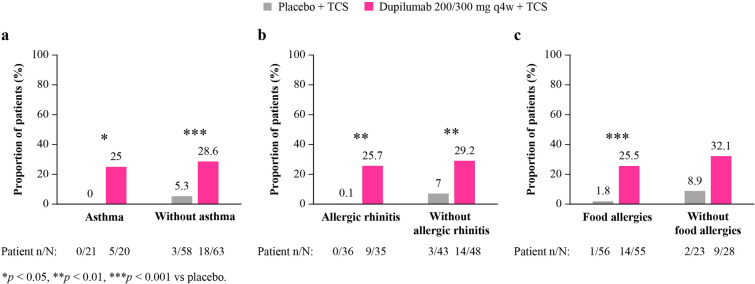

Efficacy

At week 16, significantly more patients receiving dupilumab versus placebo, with or without asthma or AR, achieved IGA 0 or 1 (with asthma: 25% vs 0% [p = 0.03]; without asthma: 29% vs 5% [p = 0.0005]; with AR: 26% vs 0.1% [p = 0.006]; without AR: 29% vs 7% [p = 0.005]) (Fig. 1). Significantly more patients with comorbid FAs and numerically more patients without FAs achieved IGA 0 or 1 (with FAs: 26% vs 2% [p = 0.0007]; without FAs (32% vs 9% [p = 0.06]).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of patients achieving an IGA score of 0/1 at week 16, with and without a asthma, b AR, c FAs. n.s. not significant; AR allergic rhinitis; FA food allergies; IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment; q4w every 4 weeks; TCS topical corticosteroid

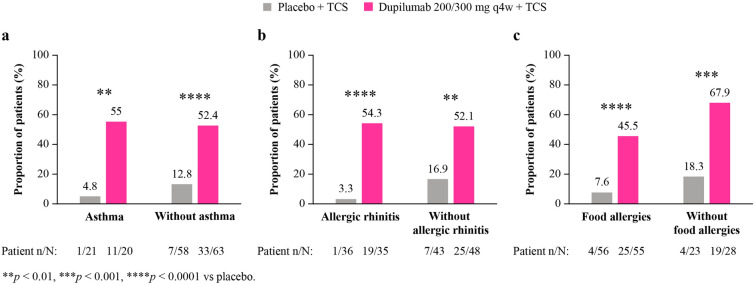

At week 16, significantly more patients receiving dupilumab versus placebo, regardless of the presence of type 2 comorbidities, achieved ≥ 75% improvement in EASI (with asthma: 55% vs 5% [p = 0.001]; without asthma: 52% vs 13% [p < 0.0001]; with AR: 54% vs 3% [p < 0.0001]; without AR: 52% vs 17% [p = 0.001]; with FAs: 46% vs 8% [p < 0.0001]; without FAs: 68% vs 18% [p = 0.0005]) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Proportion of patients achieving EASI-75 at week 16, with and without a asthma, b AR, c FA. AR allergic rhinitis; FA food allergies; EASI-75≥ 75% improvement in Eczema Area and Severity Index; q4w every 4 weeks; TCS topical corticosteroid

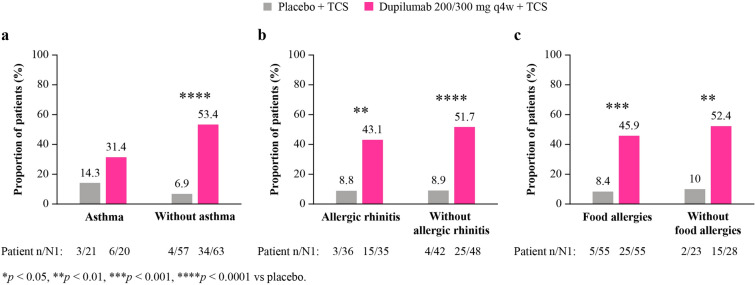

At week 16, significantly more patients receiving dupilumab versus placebo, with or without AR or FAs, achieved a ≥ 4-point reduction in the weekly average of daily score on the WSI-NRS (with AR: 43% vs 9% [p = 0.008]; without AR: 52% vs 9% [p < 0.0001]; with FAs: 46% vs 8% [p = 0.0002]; without FAs: 52% vs 10% [p = 0.004]) (Fig. 3). Numerically more patients with comorbid asthma and significantly more patients without comorbid asthma achieved a ≥ 4-point reduction (with asthma: 31% vs 14% [p = 0.6]; without asthma: 53% vs 7% [p < 0.0001]).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients achieving ≥ 4-point reduction of WSI-NRS score at week 16, with and without a asthma, b AR, c FA. AR allergic rhinitis; FA food allergies; N1 number of patients with baseline WSI-NRS score ≥ 4; WSI-NRS Worst Scratch/Itch Numeric Rating Scale; q4w every 4 weeks; TCS topical corticosteroid

Safety

Safety outcomes from the LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B study have been previously reported in detail [26]. Dupilumab was well tolerated, with an acceptable safety profile, consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile [23, 24, 28–30].

At week 16, versus patients receiving dupilumab, more patients without FAs receiving placebo reported TEAEs. Overall, more patients without type 2 comorbidities receiving placebo reported TEAEs than patients receiving dupilumab (Table 2). Additionally, more patients with asthma, FA, and AR comorbidities who received placebo had serious TEAEs than patients without asthma, FA, and AR comorbidities (Table 2). No serious TEAEs were reported in patients receiving dupilumab (Table 2). Overall, more patients with type 2 comorbidities receiving placebo reported severe TEAEs versus patients receiving dupilumab. The numbers of TEAEs leading to discontinuation and severe TEAEs were similar between patients with and without type 2 comorbidities (Table 2).

Table 2.

Safety profile for patients with and without type 2 comorbidities at week 16

| Overall summary | With asthma | Without asthma | With food allergies | Without food allergies | With allergic rhinitis | Without allergic rhinitis | With type 2 comorbidities | Without type 2 comorbidities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo + TCS (n = 21) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 20) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 57) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 63) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 55) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 55) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 23) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 28) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 36) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 35) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 42) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 48) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 63) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 65) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 15) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 18) |

|

| TEAE, n (%) | 16 (76.2) | 15 (75.0) | 42 (73.7) | 38 (60.3) | 39 (70.9) | 37 (67.3) | 19 (82.6) | 16 (57.1) | 27 (75.0) | 23 (65.7) | 31 (73.8) | 30 (62.5) | 45 (71.4) | 44 (67.7) | 13 (86.7) | 9 (50.0) |

| Serious TEAE, n (%) | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 2 (3.5) | 0 | 3 (5.5) | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 0 | 4 (6.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TEAE leading to discontinuation, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 1 (1.6) | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3.6) | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) |

| Severe TEAE, n (%) | 3 (14.3) | 0 | 7 (12.3) | 2 (3.2) | 8 (14.5) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (3.6) | 5 (13.9) | 0 | 5 (11.9) | 2 (4.2) | 9 (14.3) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (5.6) |

No TEAEs leading to death were reported

q4w every 4 weeks; TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event; TCS topical corticosteroid

Overall, at week 16, more patients without type 2 comorbidities receiving placebo reported infections and infestations versus patients receiving dupilumab. Additionally, more patients with and without asthma and FAs, and patients with AR who received placebo reported serious and severe infections versus patients treated with dupilumab (Table 3). More patients with AR receiving placebo reported adjudicated non-herpetic skin infections events versus patients receiving dupilumab. At week 16, more patients receiving dupilumab versus placebo, reported conjunctivitis cluster events, keratitis cluster events, and PT blepharitis, irrespective of type 2 comorbidities (Table 3). Additionally, versus patients receiving placebo, more patients with asthma, FA, and AR comorbidities receiving dupilumab reported angioedema (Table 3). No cases of angioedema were reported in patients without type 2 comorbidities, irrespective of treatment (Table 3). No events of herpes zoster, eye pruritus, dry eye, arthralgia, or serum sickness/serum sickness-like reaction were reported during the treatment period (Table 3). Overall, one patient (1%) discontinued dupilumab treatment as a result of an AE.

Table 3.

Summary of adverse events of special interest by subgroup at week 16

| Overall summary | With asthma | Without asthma | With food allergies | Without food allergies | With allergic rhinitis | Without allergic rhinitis | With type 2 comorbidities | Without type 2 comorbidities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo + TCS (n = 21) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 20) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 57) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 63) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 55) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 55) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 23) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 28) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 36) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 35) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 42) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n =) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 63) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 65) |

Placebo + TCS (n = 21) |

Dupilumab 200/300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 20) |

|

| Infections and infestations (SOC) | 10 (47.6) | 7 (35.0) | 31 (54.4) | 28 (45.2) | 26 (47.3) | 27 (49.1) | 15 (65.2) | 8 (28.6) | 20 (55.6) | 14 (40.0) | 21 (50.0) | 21 (43.8) | 30 (47.6) | 29 (44.6) | 11 (73.3) | 6 (33.3) |

| Serious infections | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 3 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (4.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Severe infections | 2 (9.5) | 0 | 2 (3.5) | 0 | 3 (5.5) | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 4 (11.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (6.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Injection-site reactions (HLT) | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.5) | 2 (3.2) | 0 | 2 (3.6) | 2 (8.7) | 0 | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (2.1) | 1 (1.6) | 2 (3.1) | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

| Adjudicated non-herpetic skin infections | 5 (23.8) | 1 (5) | 14 (24.6) | 9 (14.3) | 12 (21.8) | 8 (14.5) | 7 (30.4) | 2 (7.1) | 10 (27.8) | 2 (5.7) | 9 (21.4) | 8 (16.7) | 15 (23.8) | 8 (12.3) | 4 (26.7) | 2 (11.1) |

| Herpes viral infections (HLT) | 0 | 1 (5.0) | 4 (7.0) | 4 (6.3) | 3 (5.5) | 5 (9.1) | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 2 (5.6) | 4 (11.4) | 2 (4.8) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (4.8) | 5 (7.7) | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

| Eczema herpeticum (PT) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 0 |

| Herpes zoster (PT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Helminthic infections (HLGT)a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Conjunctivitis clusterb | 0 | 2 (10) | 0 | 2 (3.2) | 0 | 3 (5.5) | 0 | 1 (3.6) | 0 | 3 (8.6) | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 4 (6.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Keratitis clusterc | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.1) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Blepharitis (PT) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 2 (3.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4.2) | 0 | 2 (3.1) | 0 | 0 |

| Eye pruritus (PT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry eye (PT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia (PT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anaphylactic reaction (narrow SMQ)d | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anaphylactic reaction (related)e | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serum sickness/serum sickness-like reaction (PT) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Angioedema (PT) | 0 | 1 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 |

All data are n (%)

No events of herpes zoster, eye pruritus, dry eye, arthralgia, or serum sickness/serum sickness-like reaction were observed during the treatment period

HLGT MedDRA High Level Group Term; HLT MedDRA High Level Term; MedDRA Medical Dictionary of Regulatory Activities; NEC not elsewhere classified; PT MedDRA Preferred Term; q4w every 4 weeks; SMQ standardized MedDRA query; SOC system organ class; TCS topical corticosteroid

aIncludes all PTs under 4 MedDRA HLTs: cestode infections, helminthic infections NEC, nematode infections, and trematode infections

bIncludes all MedDRA PTs that include the term “conjunctivitis”, including (but not limited to) allergic conjunctivitis, bacterial conjunctivitis, viral conjunctivitis, giant papillary conjunctivitis, adenoviral conjunctivitis, and atopic keratoconjunctivitis

cKeratitis cluster includes all MedDRA PTs that include the term “keratitis”, including (but not limited to) keratitis, ulcerative keratitis, allergic keratitis

dAnaphylactic reaction narrow SMQ includes the PTs: anaphylactic reaction, anaphylactic shock, anaphylactic transfusion reaction, anaphylactoid reaction, anaphylactoid shock, circulatory collapse, dialysis membrane reaction, Kounis syndrome, procedural shock, shock, shock symptoms, type 1 hypersensitivity

eAssessed as causally related to treatment by investigator

Discussion

This post hoc analysis of data from the LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B study in infants and young children showed that treatment with dupilumab is associated with consistent, clinically meaningful improvements in AD signs (achievement of EASI-75 and/or IGA 0/1) and/or AD symptoms (≥ 4-point improvement in WSI-NRS) in patients with and without type 2 comorbidities.

Overall, versus patients receiving dupilumab, patients receiving placebo reported higher numbers of TEAEs, serious TEAEs, serious infections, severe infections, and adjudicated non-herpetic skin infections (Table 3). Conjunctivitis cluster events, keratitis cluster events, and blepharitis were reported in dupilumab-treated patients, irrespective of type 2 comorbidities, and angioedema was reported in dupilumab-treated patients with asthma, FA, and AR type 2 comorbidities. Otherwise, the safety profile was similar across the dupilumab and placebo groups in patients with and without comorbid type 2 conditions. Overall, treatment discontinuation was low; only one patient (1%) discontinued dupilumab treatment because of an AE. The overall safety of dupilumab was consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile.

These results are consistent with a previous post hoc analysis of clinical trial data for adults with AD, which found that the efficacy of dupilumab versus placebo on AD outcomes in subgroups with comorbid asthma and/or chronic sinonasal conditions was comparable to the efficacy in the overall study populations [27].

Besides the early age of onset of AD and its adverse impact on QoL, the high prevalence of concurrent type 2 inflammatory comorbidities imposes an additional burden on children with AD and their caregivers. Dupilumab has previously shown significant efficacy compared with placebo in the treatment of asthma [31, 32], chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps with and without AR [33], severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps [34], AR with comorbid asthma [35], and AD with comorbid asthma and/or sinonasal conditions [27]. Dupilumab inhibits the signaling of IL-4 and IL-13, which are key mediators of type 2 inflammation and serve as important components in the pathogenesis of type 2 conditions in general [16–18, 36]; therefore, dupilumab could provide a therapeutic benefit for patients with asthma comorbidities.

The results of the present study reinforce those of previous studies showing that dupilumab is effective for AD with concurrent type 2 inflammatory comorbidities. Compared with a placebo, dupilumab treatment has been demonstrated to decrease the incidence rate ratio for the risk of new, or the worsening of preexisting, allergic conditions in adult and adolescent patients with AD [37]. Asthma and AR can develop after the onset of AD in young children as part of the atopic march. Early treatment of young children with dupilumab may offer a method for disease modification by preventing the advancement of the atopic march [38]. At study enrollment, patients were classified as without asthma, AR, or FA type 2 comorbidities by caregiver report. This, however, does not preclude the development of type 2 comorbidities in the future. Patients with and without type 2 comorbidities receiving dupilumab treatment reported fewer TEAEs compared with patients receiving placebo, including but not limited to eczema herpeticum and adjusted non-herpetic skin infections. In future publications, statistically comparing the occurrence of TEAEs in patients with AD receiving dupilumab versus placebo may be beneficial in determining if dupilumab significantly reduces the chances of TEAE development in patients with AD.

Limitations of this study include the low number of patients aged 6 months to < 2 years included in some subgroups, which potentially limits the generalizability of the findings across the age groups included in this patient population. As comorbidities were caregiver assessed, they may be subject to biases around understanding and identification of FAs and other type 2 conditions as a result of variation in how these can be defined.

Conclusions

Dupilumab with concomitant TCS is efficacious in improving AD signs and symptoms in children aged 6 months to 5 years with or without a history of type 2 comorbidities. Overall safety was consistent with the known dupilumab safety profile.

Acknowledgments

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Benjamin Crane, PhD, of Excerpta Medica, and was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., according to the Good Publication Practice guidelines. The National Institute for Health and Care Research provided support to the Manchester Clinical Research Facility at Royal Manchester Children’s Hospital. Dr Ashish Bansal, MD, of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., was the medical monitor of the Liberty AD PRESCHOOL clinical trial.

Author Contributions

Mark Boguniewicz, Amy S. Paller, and Peter D. Arkwright contributed to manuscript concept and design. Lawrence D. Sher, Amy S. Paller, and Peter D. Arkwright contributed to data acquisition. Zhen Chen conducted statistical analyses of the data. All authors interpreted the data, provided critical feedback on the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript for submission, and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier NCT03346434. The journal's rapid service and open access fees were also funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the indication has been approved by a regulatory body, if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant reidentification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Mark Boguniewicz has been an investigator for Incyte, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Sanofi, and participated on advisory boards for AbbVie, Amgen, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte, LEO Pharma, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Sanofi. Lawrence D. Sher is an advisory board member for Aimmune Therapeutics, Optinose, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and Sanofi; reports speaker fees from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. and Sanofi; and clinical trials funding from Aimmune Therapeutics, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Circassia, DBV Technologies, Galderma, GSK, Lupin, Merck, Mylan, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Optinose, Pearl, Pfizer, Pulmagen, Roxane, Sanofi, Spirometrix, Teva, Vectura, and Watson Pharmaceuticals. Amy S. Paller is an investigator for AbbVie, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Krystal Biotech, LEO Pharma and UCB; a consultant for Amryt Pharma, Azitra, BioCryst, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Castle Creek Biosciences, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Krystal Biotech, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi, Seanergy, TWi Biotechnology, and UCB; and a member of the data and safety monitoring board for AbbVie, Abeona Therapeutics, Catawba Research, Galderma, and InMed Pharmaceuticals. Peter D. Arkwright has acted as an investigator for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and has received grants from and acted as an advisor for Sanofi. Shigemi Yoshihara has acted as an investigator for Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., and has received grants from and acted as an advisor for Sanofi. Zhen Chen and Parul Shah are employees and shareholders of Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Ainara Rodríguez Marco is an employee of and may hold stock and/or stock options in Sanofi.

Ethical Approval

The LIBERTY AD PRESCHOOL part B study was conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Council for Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and applicable regulatory requirements. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards/ethics committees. For each patient, written informed consent was obtained from a parent or legal guardian.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2023, February 24–27, San Antonio, Texas, USA. European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2023, June 9–11, Hamburg, Germany.

References

- 1.Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(4):417-28.e2. 10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Shobaili HA. The impact of childhood atopic dermatitis on the patients’ family. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010;27(6):618–23. 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2010.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chamlin SL, Chren M-M. Quality-of-life outcomes and measurement in childhood atopic dermatitis. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2010;30(3):281–8. 10.1016/j.iac.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eyerich K, Gooderham MJ, Silvestre JF, et al. Real-world clinical, psychosocial, and economic burden of atopic dermatitis: results from a multicountry study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023. 10.1111/jdv.19500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knudgaard MH, Andreasen TH, Ravnborg N, et al. Rhinitis prevalence and association with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;127(1):49-56.e1. 10.1016/j.anai.2021.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ravnborg N, Ambikaibalan D, Agnihotri G, et al. Prevalence of asthma in patients with atopic dermatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(2):471–8. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsakok T, Marrs T, Mohsin M, et al. Does atopic dermatitis cause food allergy? A systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137(4):1071–8. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paller AS, Mina-Osorio P, Vekeman F, et al. Prevalence of type 2 inflammatory diseases in pediatric patients with atopic dermatitis: real-world evidence. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86(4):758–65. 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paller AS, Spergel JM, Mina-Osorio P, Irvine AD. The atopic march and atopic multimorbidity: many trajectories, many pathways. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):46–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van der Hulst AE, Klip H, Brand PL. Risk of developing asthma in young children with atopic eczema: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(3):565–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aberle N, Kljaić Bukvić B, Blekić M, et al. Allergic diseases and atopy among schoolchildren in eastern Croatia. Acta Clin Croat. 2018;7(1):82–90. 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kapoor R, Menon C, Hoffstad O, et al. The prevalence of atopic triad in children with physician-confirmed atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(1):68–73. 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bergmann MM, Caubet JC, Boguniewicz M, Eigenmann PA. Evaluation of food allergy in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2013;1(1):22–8. 10.1016/j.jaip.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Breuer K, Heratizadeh A, Wulf A, et al. Late eczematous reactions to food in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(5):817–24. 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.1953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sampson HA, McCaskill CC. Food hypersensitivity and atopic dermatitis: evaluation of 113 patients. J Pediatr. 1985;107(5):669–75. 10.1016/s0022-3476(85)80390-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gandhi NA, Pirozzi G, Graham NMH. Commonality of the IL-4/IL-13 pathway in atopic diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2017;13(5):425–37. 10.1080/1744666X.2017.1298443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Macdonald LE, Karow M, Stevens S, et al. Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5147–52. 10.1073/pnas.1323896111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murphy AJ, Macdonald LE, Stevens S, et al. Mice with megabase humanization of their immunoglobulin genes generate antibodies as efficiently as normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5153–8. 10.1073/pnas.1324022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Floc’h A, Allinne J, Nagashima K, et al. Dual blockade of IL-4 and IL-13 with dupilumab, an IL-4Rα antibody, is required to broadly inhibit type 2 inflammation. Allergy. 2020;75(5):1188–204. 10.1111/all.14151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc./sanofi-aventis U.S. LLC. Highlights of Prescribing Information. In: DUPIXENT® (dupilumab) injection, for subcutaneous use. US Food and Drug Administration. 2020. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/761055s040lbl.pdf. Accessed Nov 25, 2023.

- 21.Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):130–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thaçi D, Simpson EL, Beck LA, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis inadequately controlled by topical treatments: a randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10013):40–52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287–303. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de Bruin-Weller M, Thaçi D, Smith CH, et al. Dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroid treatment in adults with atopic dermatitis with an inadequate response or intolerance to ciclosporin A or when this treatment is medically inadvisable: a placebo-controlled, randomized phase III clinical trial (LIBERTY AD CAFÉ). Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(5):1083–101. 10.1111/bjd.16156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10356):908–19. 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boguniewicz M, Beck LA, Sher L, et al. Dupilumab improves asthma and sinonasal outcomes in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(3):1212-23.e6. 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):44–56. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1282–93. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cork MJ, Thaçi D, Eichenfield LF, et al. Dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: results from a phase IIa open-label trial and subsequent phase III open-label extension. Br J Dermatol. 2020;182(1):85–96. 10.1111/bjd.18476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pavord ID, Bourdin A, Papi A, et al. Dupilumab sustains efficacy in patients with moderate-to-severe type 2 asthma regardless of inhaled corticosteroids dose. Allergy. 2023;78(11):2921–32. 10.1111/all.15792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wenzel S, Castro M, Corren J, et al. Dupilumab efficacy and safety in adults with uncontrolled persistent asthma despite use of medium-to-high-dose inhaled corticosteroids plus a long-acting β2 agonist: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled pivotal phase 2b dose-ranging trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10039):31–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peters AT, Wagenmann M, Bernstein JA, et al. Dupilumab efficacy in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps with and without allergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2023;44(4):265–74. 10.2500/aap.2023.44.230015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394(10209):1638–50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31881-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinstein SF, Katial R, Jayawardena S, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in perennial allergic rhinitis and comorbid asthma. Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(1):171-7.e1. 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gandhi NA, Bennett BL, Graham NMH, Pirozzi G, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2016;15(1):35–50. 10.1038/nrd4624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Geba GP, Li D, Xu M, et al. Attenuating the atopic march: meta-analysis of the dupilumab atopic dermatitis database for incident allergic events. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;151(3):756–66. 10.1016/j.jaci.2022.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bieber T. Disease modification in inflammatory skin disorders: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023;22(8):662–80. 10.1038/s41573-023-00735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the indication has been approved by a regulatory body, if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant reidentification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.