Abstract

Understanding the intricacies of homologous recombination during meiosis is crucial for reproductive biology. However, the role of alternative splicing (AS) in DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) repair and synapsis remains elusive. In this study, we investigated the impact of conditional knockout (cKO) of the splicing factor gene Bcas2 in mouse germ cells, revealing impaired DSBs repair and synapsis, resulting in non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA). Employing crosslinking immunoprecipitation and sequencing (CLIP-seq), we globally mapped BCAS2 binding sites in the testis, uncovering its predominant association with 5’ splice sites (5’SS) of introns and a preference for GA-rich regions. Notably, BCAS2 exhibited direct binding and regulatory influence on Trp53bp1 (codes for 53BP1) and Six6os1 through AS, unveiling novel insights into DSBs repair and synapsis during meiotic prophase I. Furthermore, the interaction between BCAS2, hnRNPH1, and SRSF3 was discovered to orchestrate Trp53bp1 expression via AS, underscoring its role in meiotic prophase I DSBs repair. In summary, our findings delineate the indispensable role of BCAS2-mediated post-transcriptional regulation in DSBs repair and synapsis during male meiosis. This study provides a comprehensive framework for unraveling the molecular mechanisms governing the post-transcriptional network in male meiosis, contributing to the broader understanding of reproductive biology.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00018-024-05479-7.

Keywords: BCAS2, Alternative splicing, Infertility, Meiosis, DNA double-strand breaks repair, Synapsis

Introduction

Homologous recombination in meiosis is fundamental for biodiversity and accurate chromosome segregation, ensuring the production of haploid gametes [1]. Programmed DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), catalyzed by the evolutionarily conserved topoisomerase-like SPO11 protein, initiate meiotic recombination [2, 3]. In humans and mice, two major SPO11 isoforms, SPO11α and SPO11β, the former arising from alternative splicing (AS) through exon 2 skipping, coexist [4]. While transgenic mice expressing only SPO11β exhibit competence in establishing the initial DSB wave, suppression of late foci in the sex chromosomes by SPO11α leads to male sterility [5]. hnRNPH1, a key regulator of SPO11α splicing in mouse spermatocytes, tightly controls exon 2 skipping [6, 7], highlighting the intricate regulation of programmed DSBs through AS.

DSBs repair is contingent upon the coordinated events of homologous pairing and synaptonemal complex (SC) assembly during meiotic prophase I [8, 9]. Essential for DSBs repair, homologous pairing undergoes intricate regulation by homology recognition-related proteins (DMC1 and HFM1) and the telomere-nuclear envelope attachment related proteins (KASH5, SUN1, SUN2, TERB1-TERB2-MAJIN, SPDYA-CDK2, and TRF1) [10–14]. The SC, a crucial protein structure forming chromosomal bivalents, comprises distinct components: the lateral elements (LE), including SYCP2-3; the central element (CE) proteins, such as SYCE1-3, TEX12, C14ORF39/SIX6OS1, and SCRE; and the transverse filament (TF) component SYCP1 [15, 16]. The development of LE stems from the axial element, housing chromosomal structures and meiosis-specific cohesin subunits like REC8, SMC1B, STAG3, and RAD21L [1, 17, 18]. Notably, splicing abnormalities in STAG3, SYCE1, and C14ORF39/SIX6OS1 have been implicated in human infertility cases. In a mouse model with the deletion of the splicing factor SRSF1, abnormal AS of pre-mRNAs Six6os1, Sycp1, Dmc1, Majin, Sun1, and Kash5 was observed, resulting in the phenotype of unequal male and female infertility [19–24]. These findings underscore the extensive involvement of splicing factor-mediated AS during meiotic prophase I.

Breast carcinoma-amplified sequence 2 (BCAS2) emerges as a versatile regulator with direct influences on DSBs repair, engaging with replication protein A (RPA) complexes or the NBS1 protein [25, 26]. Additionally, BCAS2 assumes a role as a negative regulator of p53 [27, 28]. Recognized as pre-mRNA splicing factor SPF27, BCAS2 is implicated in the intricate regulation of AS [29–31]. While the regulatory network of DSBs repair involves various factors such as 53BP1 (encoded by the Trp53bp1 gene), RIF1, BRCA1, DMC1, RAD51, ATM, MSH4, MLH1, and MLH3 [32, 33]. Despite this wealth of knowledge, the precise mechanisms by which post-transcriptional regulation, particularly AS, contributes to DSB repair remain largely unexplored. Recent discoveries from our researches indicate that BCAS2-mediated AS plays a substantial role in oocyte and granulosa cell development, spermatogonial transition to meiosis, and insulin synthesis [34–37].

In this study, we demonstrated that the conditional knockout of Bcas2 in mouse germ cells leads to impaired DSBs repair and synapsis, resulting in non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA). Moreover, we conducted a pioneering exploration into the global landscape of BCAS2 binding sites in the testis using crosslinking immunoprecipitation and sequencing (CLIP-seq). Our findings unveiled that BCAS2 exhibits direct binding capabilities and regulates the AS of crucial pre-mRNAs associated with DSBs repair and synapsis, including Spo11, Six6os1, Sycp1, Msh5, Cdk2, Sun2, Stag3, and Spdya. In conclusion, our study introduces a novel mechanism involving BCAS2-mediated post-transcriptional regulation, specifically through AS, in the processes of DSBs repair and synapsis during meiosis.

Results

BCAS2 may have a vital role in post-transcriptional regulation during meiosis

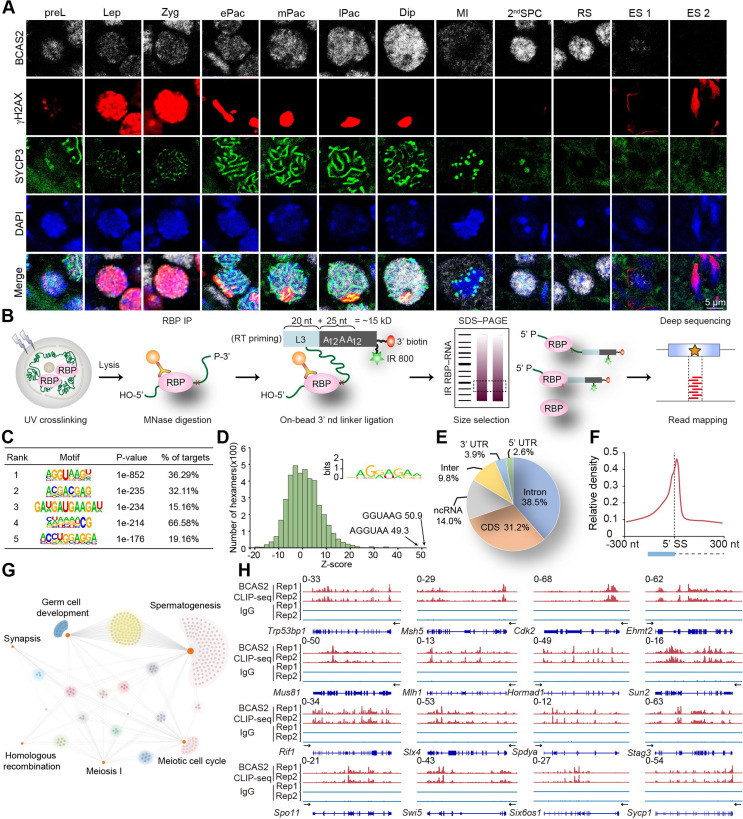

In our prior investigation, we unequivocally demonstrated the involvement of BCAS2-mediated AS in spermatogonial development [34]. Expanding our focus beyond the initial stage of spermatogonial development, we probed into the multifaceted role of BCAS2 during spermatogenesis. An in-depth analysis of how BCAS2 is dynamically localized in the testis uncovered surprising revelations. Co-staining for BCAS2, γH2AX, and SYCP3 unveiled the dynamic expression patterns of BCAS2 during meiosis and spermiogenesis (Fig. 1A and S1). Notably, BCAS2 exhibited a gradual increase in expression during the first meiotic prophase, maintaining heightened levels in both secondary spermatocytes and round spermatids, followed by a rapid decrease in elongated spermatids (Fig. 1A and S1).

Fig. 1.

Dynamic localization of BCAS2 and the global landscape of its binding sites in adult mouse testis. (A) Dynamic localization of BCAS2 in spermatogenesis. Co-immunostaining was performed using BCAS2, γH2AX, and SYCP3 antibodies from adult mouse testis. DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 5 µm. preL, Preleptotene. Lep, Leptotene. Zyg, Zygotene. ePac, early Pachytene. mPac, middle Pachytene. lPac, late Pachytene. Dip, Diplotene. MI, Metaphase I. 2nd SPC, secondary spermatocyte. RS, round spermatid. ES, elongated spermatid. (B) Schematic diagram of the CLIP-seq experiment. (C) Enriched BCAS2 binding motifs. The top six enriched motifs are shown. (D) Histogram showing overrepresented BCAS2-binding motifs identified by CLIP-seq. The Z scores of the top two hexamers are indicated. (E) Pie chart showing the proportion of BCAS2-binding peaks annotated to the 3’ or 5’ untranslated region (UTR), coding sequence (CDS), intron, intergenic, and ncRNA, which were assessed by CLIP-seq. (F) Schematic analyses exhibiting the distribution of BCAS2-binding peaks in the vicinity of the 5’ exon‒intron boundaries (300 nt upstream and 300 nt downstream of the 5’SS). (G) Network showing GO enrichment analyses of BCAS2-binding genes. (H) Representative genome browser views of synapsis and homologous recombination bination-related gene transcripts bound by BCAS2

Considering the role of BCAS2 as a splicing factor, we conducted CLIP-seq on adult mouse testis to understand its genome-wide binding patterns with pre-mRNA. (Fig. 1B). Robust correlation (R = 0.95) between the two biological replicates of BCAS2 CLIP-seq libraries, as revealed by Pearson’s correlation analysis, underscored the reliability of our findings (Figure S2A). BCAS2-bound reads exhibited a notable enrichment between transcription start sites (TSSs) and transcription end sites (TESs) (Figure S2B). Further analysis of BCAS2 binding peaks, particularly their preference for GA-enriched sequences in mouse testis, highlighted intriguing insights (Fig. 1C and D). Noteworthy enrichment in intronic regions (38.5%) compared to coding sequences (CDSs) (31.2%) (Fig. 1E), along with predominant binding to the 5’ splice site (SS) of introns (Fig. 1F and S2C), strongly suggested a pivotal functional role of BCAS2 in splicing. To unravel the functional implications of genes corresponding to BCAS2-bound pre-mRNA, we conducted a thorough Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis. The outcomes indicated that BCAS2 might intricately regulate genes associated with synapsis and homologous recombination (Fig. 1G). Further insights into BCAS2 binding peaks of representative genes related to synapsis and homologous recombination were visually presented using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) tool (Fig. 1H). In conclusion, our comprehensive findings provide compelling evidence that BCAS2 assumes a pivotal role in post-transcriptional regulation during meiosis, particularly influencing processes such as synapsis and homologous recombination.

Impaired meiotic progression due to BCAS2 deficiency

To delineate the specific role of BCAS2 in meiosis, we conducted an in-depth exploration of its physiological impact in vivo using Bcas2Fl/Fl and Stra8-GFPCre mouse models. The Bcas2Fl/Fl mice were engineered with loxP sites flanking exons 3 and 4 [25] (Fig. 2A). Meanwhile, the Stra8-GFPCre mice initiate CRE enzyme expression at 3 days post-partum (dpp) and facilitate gene knockout in germ cells (Fig. 2A) [38, 39]. The crossbreeding of Bcas2Fl/Fl and Stra8-GFPCre mice resulted in the generation of Stra8-GFPCre Bcas2Fl/Δ (cKO) mice, wherein Bcas2 deletion in germ cells was validated through genotyping (Figure S3A). Immunostaining with BCAS2 and SYCP3 antibodies conclusively demonstrated the absence of BCAS2 in spermatocytes (Fig. 2B). Following reproduction experiments, it was observed that male cKO mice exhibited infertility, despite their ability to detect vaginal plugs (Figure S3B). Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining of the cauda epididymis displayed a stark absence of sperm in cKO mice (Figure S3C). This observation was further confirmed by a caudal epididymal sperm count, reinforcing the conclusion of severe impairment in testicular spermatogenic function (Figure S3D). These findings collectively indicate that BCAS2 deficiency significantly disrupts meiotic progression, leading to infertility in male mice.

Fig. 2.

BCAS2 plays critical roles in spermatogenesis. (A) Stra8-GFPCre mice were crossed with Bcas2Fl/Fl mice to generate Bcas2 cKO mice. Cre-mediated deletion removed exons 3 and 4 of Bcas2 and generated a null protein allele. (B) Co-immunostaining of BCAS2 and SYCP3 in adult Ctrl and cKO testis. DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 5 μm. BCAS2 is absent from all spermatocytes in the cKO mouse testis. n = 4. (C) Testis atrophy in adult cKO mice. Testis sizes and weights of adult Ctrl and cKO mice are shown as the mean ± SEM. n = 7. (D) Hematoxylin-eosin-stained testis sections from adult Ctrl and cKO mice were obtained. Scale bar, left panel: 200 μm, right panel: 50 μm. SPG, spermatogonium; SPC, spermatocyte; RS, round spermatid; ES, elongated spermatid. n = 4. (E) A TUNEL apoptosis assay was performed on sections from adult Ctrl and cKO testis. DNA was stained with DAPI. White arrows indicate apoptotic germ cells. Scale bar, 20 μm. n = 4. (F) The percentage of apoptotic tubules is shown as the mean ± SEM. n = 4. (G) Co-immunostaining of SYCP3 and γH2AX in adult Ctrl and cKO testis. DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, right panel: 20 μm, other panels: 100 μm. n = 4. Unpaired Student’s t-test determined significance. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. The points and error bars represent the mean ± SEM

Subsequent morphological analysis of the testis unveiled a notable reduction in size in cKO mice (Fig. 2C). Histological examination of testicular sections provided further insights, revealing impaired spermatogenesis in the absence of BCAS2 (Fig. 2D). In the testes of cKO mice, the presence of spermatocytes was observed, while spermatids were not detected (Fig. 2D). Co-staining of ACRV1 and SOX9 indicated the absence of spermatids, although Sertoli cells were still present (Figure S3E). Simultaneously, TUNEL analysis showed more apoptotic signals in cKO testis (Fig. 2E). The statistics of the percentage of apoptotic tubules showed a significant increase in apoptosis within the cKO testis (Fig. 2F). To ascertain whether cKO mice were arrested at the spermatocyte stage, co-staining of adult mouse testis sections with SYCP3 and γH2AX was performed, revealing a clear arrest at the primary spermatocyte stage (Fig. 2G). This compellingly suggests a blockade in meiosis within the cKO testis. In summary, these findings underscore the critical role of BCAS2 in meiotic progression, with its absence leading to NOA characterized by impaired spermatogenesis and testicular atrophy.

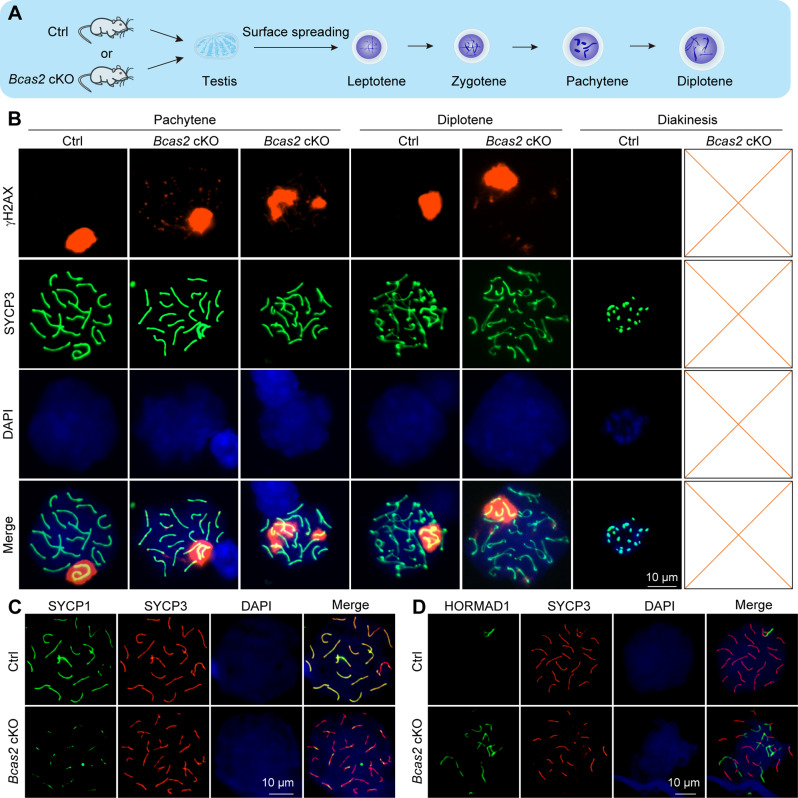

In the role of BCAS2 concerning the repair of DSBs and synapsis

To elucidate the phenotypes, we employed mouse germ cell surface spreading for an in-depth examination (Fig. 3A). Co-staining of SYCP3 and γH2AX unveiled that germ cells from cKO mice were arrested at diplotene, with a significant number of DSBs on autosomes remaining unrepaired in pachytene and diplotene stages, accompanied by abnormal SC formation (Fig. 3B). To further validate the abnormal SC formation phenotype, co-staining of SYCP1 and SYCP3 was conducted on mouse germ cell surface spreading (Fig. 3C). The data illustrated that in cKO sperm cells, certain homologous chromosomes failed to form complete SCs between them (Fig. 3C). Additionally, HORMAD1 and SYCP3 co-staining results indicated a failure of some chromosomes to undergo synapsis during the pachytene stage (Fig. 3D). Thus, the deficiency of BCAS2 manifested as dysregulation in the repair of DSBs and aberrant synapsis during meiosis. These findings underscore the pivotal role of BCAS2 in ensuring the proper progression of key meiotic events.

Fig. 3.

BCAS2 is required for DSBs repair and synapsis. (A) A schematic illustration of testes’ surface spreading was shown. (B) Co-immunostaining was performed using SYCP3 and γH2AX antibodies from adult mouse testis surface spreading. DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. n = 4. (C) Co-immunostaining was performed using SYCP1 and SYCP3 antibodies from adult mouse testis surface spreading. DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. n = 4. (D) Co-immunostaining was performed using HORMAD1 and SYCP3 antibodies from adult mouse testis surface spreading. DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. n = 4

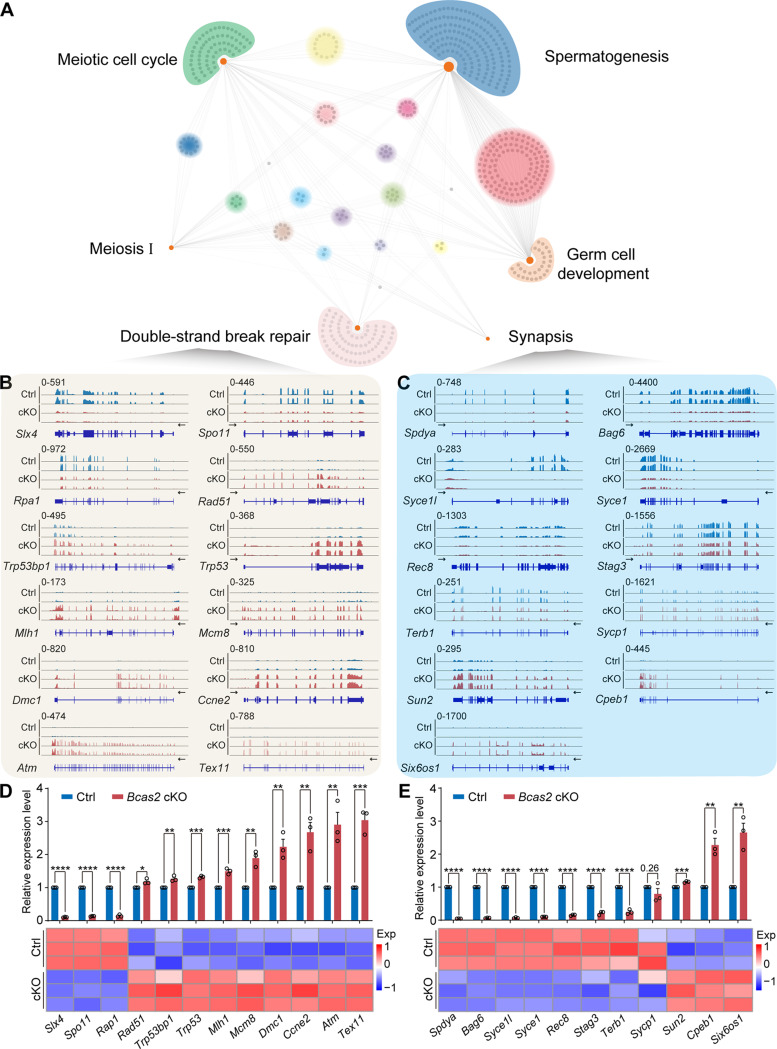

BCAS2 is essential for gene expression during DSBs repair and synapsis

In-depth exploration of the molecular mechanisms underlying the involvement of BCAS2 in DSBs repair and synapsis was conducted through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) on mRNA extracted from cKO and control (Ctrl) adult mouse testis, specifically focusing on STRA8+ cells, as per established protocols from previous studies [24]. The results, as anticipated, revealed a substantial reduction in Bcas2 expression, a finding consistently validated through both RNA-seq and quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR) (Figs. S4A, S4B and S4C). The high correlation observed among the three replicates of Ctrl and cKO samples validated the reliability and consistency of the RNA-seq data (Fig. S4D).

An analysis of the RNA-seq data brought to light 10,647 downregulated and 5,719 upregulated genes in cKO STRA8+ cells (Figs. S4E, S4F, and Table S1). GO enrichment analysis pinpointed the involvement of BCAS2 in the expression of genes crucial for DSBs repair and synapsis (Fig. 4A). Visualization of selected genes using the IGV tool highlighted their altered expression patterns in the absence of BCAS2 (Fig. 4B and C). These genes were then re-mapped on heatmaps based on RNA-seq and validated by RT-qPCR. Further validation through RT-qPCR underscored the dysregulation of DSBs repair and synapsis-related genes (downregulated: Slx4, Spo11, Rpa1, Spdya, Bag6, Syce1l, Syce1, Rec8, Stag3, and Terb1; upregulated: Rad51, Trp53bp1, Trp53, Mlh1, Mcm8, Dmc1, Ccne2, Atm, Tex11, Sun2, Cpeb1, and Six6os1; stabilized: Sycp1) in cKO mouse STRA8+ cells (Fig. 4D and E). In conclusion, the deletion of Bcas2 resulted in a significant disruption in the expression of genes intricately linked to DSBs repair and synapsis, emphasizing the indispensable role of BCAS2 in orchestrating these vital meiotic processes.

Fig. 4.

BCAS2 plays critical roles in DSBs repair and synapsis. (A) Network showing GO enrichment analyses of differentially expressed genes. (B) The expression of genes associated with DSBs repair is shown as read coverage based on RNA-seq. (C) The expression of synapsis-related genes is shown as read coverage based on RNA-seq. (D) The expression of genes associated with DSBs repair in mouse testis STRA8+ cells. The RT‒qPCR data were normalized to Gapdh. The value in the Ctrl group was set as 1.0, and the relative value in the cKO group is indicated. n = 3. Heatmap of genes expression associated with DSBs repair. Exp, expression. (E) The expression of synapsis-related genes in mouse testis STRA8+ cells. The RT‒qPCR data were normalized to Gapdh. The value in the Ctrl group was set as 1.0, and the relative value in the cKO group is indicated. n = 3. Heatmap of synapsis-related gene expression. Exp, expression. Unpaired Student’s t-test determined significance. Exact P value P ≥ 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. The points and error bars represent the mean ± SEM

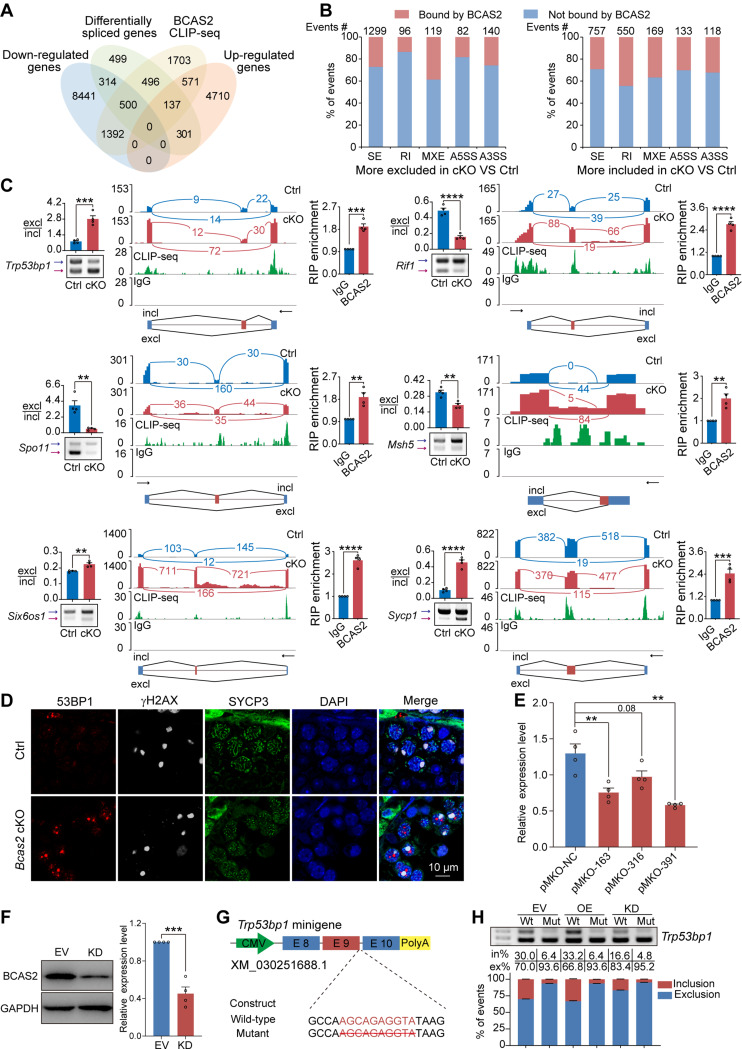

BCAS2 directly binds and regulates AS during DSBs repair and synapsis

In our pursuit of unraveling the intricate splicing dynamics orchestrated by BCAS2, we conducted a meticulous investigation of AS events in mouse testicular STRA8+ cells using RNA-seq. The diverse AS events were meticulously categorized into five distinct types, namely skipped exon (SE), retained intron (RI), mutually exclusive exon (MXE), alternative 5’ splice site (A5SS), and alternative 3’ splice site (A3SS) (Figure S5A). The prevalence of these events in cKO mouse testes revealed a significant impact, with SE events constituting the majority at 59%, followed by RI (19%), MXE (8%), A3SS (7%), and A5SS (6%) (Figure S5B). A substantial total of 3,463 AS events were identified, with a stringent significance threshold (FDR < 0.05), highlighting the pervasive influence of BCAS2 on splicing regulation (Table S2). Among these events, the majority, comprising 2056, were categorized as SE, followed by RI at 646, MXE at 288, A5SS at 215, and A3SS at 258 (Figure S5C). A holistic assessment of the aberrant AS events uncovered a distinct pattern in BCAS2-deficient mice. Notably, the absence of BCAS2 was found to effectively suppress MXE and A5SS events, while concurrently promoting SE, RI, and A3SS events (Figure S5C). Intriguingly, GO enrichment analysis associated these aberrant AS events with genes implicated in DSBs repair and synapsis (Figure S5D).

The regulatory influence of BCAS2 on AS during DSBs repair and synapsis was further explored through a multi-omics approach. A Venn diagram illuminated 500 downregulated and 137 upregulated genes among the 3,463 AS-affected genes directly bound by BCAS2 (Fig. 5A). Notably, 496 BCAS2-bound genes undergoing aberrant AS demonstrated stable expression (Fig. 5A). The intricate details of excluded and included splicing events bound by BCAS2 were unveiled, offering a glimpse into the molecular intricacies of BCAS2-mediated splicing regulation (Fig. 5B). To delve deeper into the mechanistic underpinnings, a subset of genes pivotal for DSBs repair and synapsis, including Trp53bp1, Rif1, Spo11, Six6os1, Sycp1, Msh5, Cdk2, Sun2, Stag3, and Spdya, was selected for meticulous scrutiny. RT-PCR experiments unveiled abnormal AS patterns in the pre-mRNA of these genes in cKO mouse testicular STRA8+ cells (Fig. 5C and S6). Leveraging RNA-seq and CLIP-seq data, the IGV tool provided a visual narrative of the distinct AS patterns induced by BCAS2 deficiency (Fig. 5C and S6). The multi-faceted binding capability of BCAS2 was corroborated through RNA immunoprecipitation qPCR (RIP-qPCR) results, elucidating its interaction with the pre-mRNAs of these genes (Fig. 5C and S6). The investigative journey extended to the realm of protein expression, where immunostaining results showcased a substantial increase in the expression level of 53BP1 (codes for 53BP1), a key player in DSB repair (Fig. 5D) [32]. Thus, this convergence of multi-omics evidence underscores the pivotal role of BCAS2 in finely tuning the intricate machinery of DSBs repair and synapsis at both transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels.

Fig. 5.

BCAS2 directly binds and regulates the expression and AS of pre-mRNA Trp53bp1. (A) Venn diagram showing the correlation among down regulated, upregulated, alternatively spliced, and BCAS2-binding genes. (B) Excluded and included splicing events bound by BCAS2 are shown, respectively. (C) The ectopic splicing of genes related to DSBs repair and synapsis in STRA8+ cells of cKO mouse testes was assessed through RT–PCR (n = 4 per group). The ratio of exclusion to inclusion is shown accordingly. Analysis of gene expression and exon‒exon junctions associated with DSBs repair and synapsis. The BCAS2-binding peaks of genes associated with DSBs repair and synapsis transcripts are shown. Black arrow, direction of transcription. BCAS2 directly regulated the expression of genes associated with DSBs repair and synapsis by RIP–qPCR in 14 dpp mouse testis. n = 4. excl, exclusion. incl, inclusion. (D) Co-immunostaining was performed using 53BP1, γH2AX and SYCP3 antibodies from adult mouse testes sections. DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. n = 4. (E) Expression of BCAS2 in 293T cells. The RT‒qPCR data were normalized to Actb. n = 3. (F) Western blotting of BCAS2 expression in 293T cells. ACTB served as a loading control. The value in the EV group was set as 1.0, and the relative values in other groups are indicated. n = 3. KD, BCAS2 knockdown. EV, empty vector. (G) Graphical representation of Trp53bp1 minigenes. The potential BCAS2-binding sites are marked in red characters, and the specific deletion mutations are indicated with strikeout text. CMV, cytomegalovirus, E, exon. (H) Analysis of the splicing of Trp53bp1 minigenes by RT‒PCR. The percentages of inclusion (in%, red) and exclusion (ex%, blue) within exon 9 of Trp53bp1 transcripts are presented, respectively. The data are shown as mean ± SEM. n = 4. OE, BCAS2 overexpression. Wt, wild-type. Mut, mutant type. Unpaired Student’s t-test determined significance. Exact P value P ≥ 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. The points and error bars represent the mean ± SEM

In pursuit of a deeper understanding, a minigene reporter assay unfolded as a powerful tool, shedding light on the AS dynamics of Trp53bp1. Leveraging 293T cell models with manipulated BCAS2 expression levels (KD/EV/OE) set the stage for a meticulous examination (Fig. 5E and F). The subsequent construction of minigene vectors, harboring fragments of mouse genomic DNA with or without the BCAS2 binding motif on the 5’SS of the intron between exon 9 and exon 10 of Trp53bp1, provided a nuanced perspective (Fig. 5G). The ensuing minigene reporter assay, executed in various combinations in co-transfections into 293T cells, meticulously mirrored the in vivo splicing patterns. Inhibition of BCAS2 expression precipitated the exclusion of exon 9 in Trp53bp1, accentuating the pivotal role of BCAS2 in this AS event. Conversely, the overexpression of Bcas2 exerted a significant inhibitory effect on the exclusion of exon 9 in Trp53bp1 (Fig. 5H). A further layer of evidence emerged with the deletion of the BCAS2 binding motif on the 5’SS of the intron between exon 9 and exon 10, effectively facilitating the exclusion of exon 9 in Trp53bp1 (Fig. 5H).

Indeed, these findings intricately weave a narrative of BCAS2 playing a direct and nuanced role in the AS regulation of Trp53bp1, orchestrating a molecular symphony that delicately tunes the balance of 53BP1 expression.

BCAS2 orchestrates AS of pre-mRNA Trp53bp1 in the testis through interactions with hnRNPH1 and SRSF3

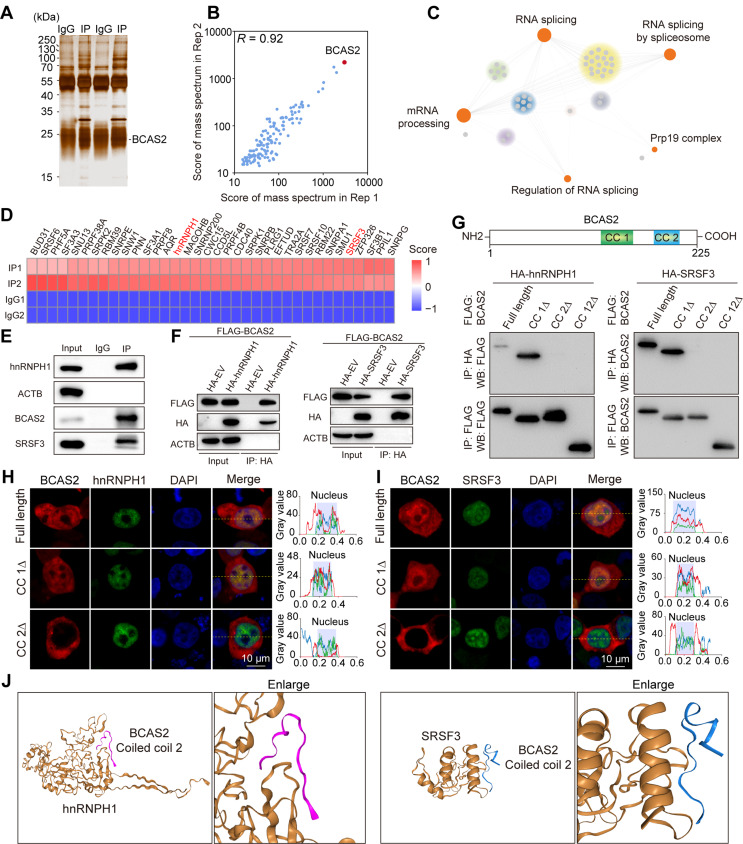

To unravel the intricacies of AS modulation in the testis, we probed the interactome of BCAS2 through an immunoprecipitation mass spectrum (IP-MS) analysis in adult mouse testis (Table S3). The silver-stained gel results of the IP unveiled a potential cohort of BCAS2-interacting proteins (Fig. 6A). Notably, the IP-MS demonstrated robust reproducibility with effective BCAS2 immunoprecipitation (Fig. 6B). A subsequent GO enrichment analysis of genes corresponding to BCAS2-immunoprecipitated proteins spotlighted those linked with RNA splicing (Fig. 6C). These RNA splicing-related factors were singled out, and the heatmap of each splicing-associated protein, based on IP-MS scores, further underscored their potential involvement (Fig. 6D). Within this protein constellation, the hnRNPH1-SRSF3 interaction caught our attention, as it is known to play a pivotal role in AS during DSBs repair and synapsis in mice [6]. Therefore, we immediately examined the interaction of BCAS2 with hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 in the testis using the Co-IP method. This data indicated that BCAS2 interacts with hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 in mouse testis (Fig. 6E). Validation experiments in 293T cells confirmed this interaction. Co-IP results using FLAG-BCAS2 and HA-hnRNPH1/SRSF3 constructs substantiated the physical interactions (Fig. 6F).

Fig. 6.

BCAS2 recruits AS-related proteins to modulate AS. (A) Silver-stained gel of BCAS2 and normal IgG immunoprecipitates from adult mouse testis extracts. (B) Pearson’s correlation analysis showed the coefficient between the two samples for mass spectrometric analysis. (C) Network showing GO enrichment analyses of BCAS2-binding proteins. (D) Heatmap of splicing-related proteins from BCAS2-binding proteins. (E) Co-IP experiment for detecting the BCAS2 association between hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 in mouse testes. (F) Co-IP experiment for detecting the BCAS2 association between hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 in 293T cells. (G) Co-IP experiment for detecting the BCAS2 truncated protein association between hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 in 293T cells. (H) hnRNPH1-eGFP cotransfected with BCAS2-mCherry, BCAS2 CC1Δ-mCherry, and BCAS2 CC2Δ-mCherry 293T cells is shown. DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. Gray-scale scanning of the red, green, and blue channels following the dashed path to draw a line graph. n = 3. (I) SRSF3-eGFP cotransfected with BCAS2-mCherry, BCAS2 CC1Δ-mCherry, and BCAS2 CC2Δ-mCherry 293T cells is shown. DNA was stained with DAPI. Scale bar, 10 μm. Gray-scale scanning of the red, green, and blue channels following the dashed path to draw a line graph. n = 3. (J) A schematic diagram of protein interactions is shown

To delve deeper into the structural basis of BCAS2 interaction with hnRNPH1 and SRSF3, we employed a targeted approach by constructing three expression plasmids in the pcDNA3.0 vector. These plasmids harbored deletions of each of the two coiled coils (CC) of BCAS2, as well as an all-encompassing deletion of both CCs. The subsequent Co-IP results offered valuable insights, pinpointing the CC2 structural domain of BCAS2 as the proficiently interacting region with HA-hnRNPH1 and HA-SRSF3 in 293T cells (Fig. 6G). To validate the co-localization of these interactions in cells, we engineered expression plasmids with fusion mCherry, each lacking CC1 or CC2 of BCAS2. These constructs, along with full-length and two truncated Bcas2 expression plasmids, were co-transfected into 293T cells along with eGFP-hnRNPH1 and eGFP-SRSF3. Intriguingly, the results revealed that BCAS2 CC2-deficient proteins failed to co-localize with hnRNPH1 and SRSF3, underscoring the indispensability of CC2 for these interactions (Fig. 6H and I). To further solidify the structural basis of interaction, molecular docking simulations were performed using HDOCK, a widely used web server for hybrid docking [40]. The docking of BCAS2 CC2 with hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 provided a molecular perspective, illustrating the potential binding modes and confirming the intricate interactions (Fig. 6J). Thus, these comprehensive data substantiate the notion that BCAS2 interacts with both hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 in the mouse testis, with the CC2 domain playing a pivotal role in these intricate molecular associations.

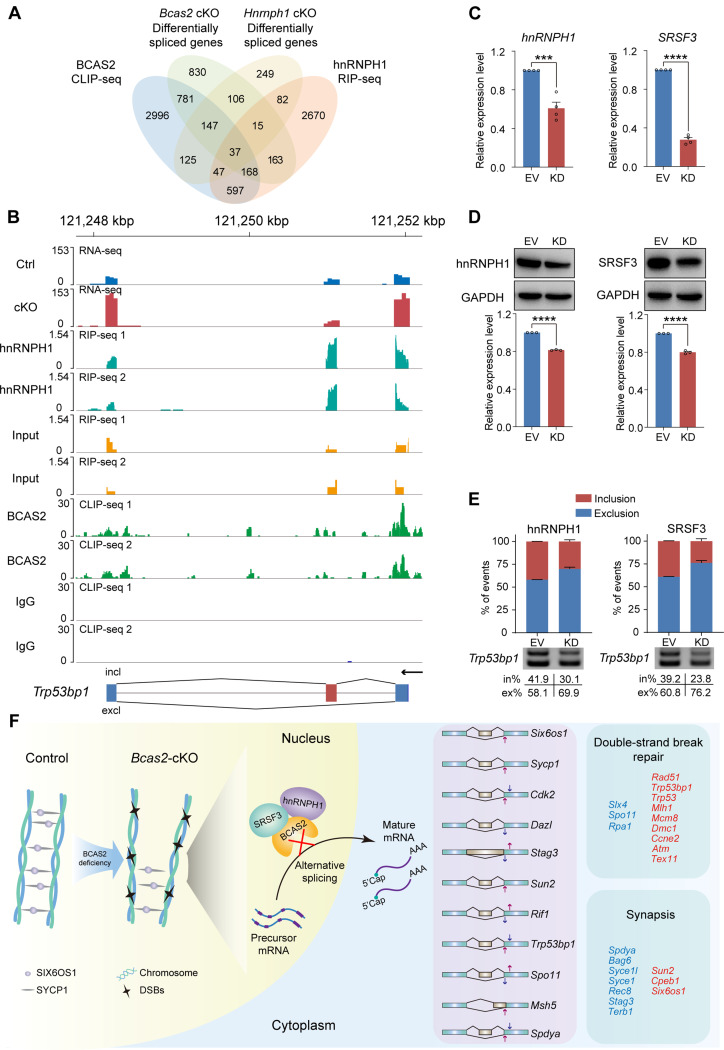

Deletion of Hnrnph1 in mouse germ cells has been associated with aberrant AS of pre-mRNAs, particularly those related to synapsis and DNA recombination, resulting in defects in association and DSBs repair during meiosis [6]. Integrating data from BCAS2 CLIP-seq, hnRNPH1 RIP-seq, and their respective RNA-seq experiments, a Venn diagram highlighted 849 genes co-bound by BCAS2 and hnRNPH1, of which 37 genes collectively exhibit aberrant AS (Fig. 7A). The IGV tool facilitated the examination of BCAS2 and hnRNPH1 binding regions associated with AS abnormalities in key genes such as Trp53bp1 and Six6os1 (Fig. 7B and S6). To further validate the regulatory impact of hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 on AS, we constructed 293T cell models with knockdowns of hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 (Fig. 7C, D). The subsequent minigene reporter assays showcased that the knockdown of either hnRNPH1 or SRSF3 effectively suppressed the inclusion of Trp53bp1 exon 9, mirroring the AS regulatory role observed for BCAS2 (Fig. 7E). In summation, the above data demonstrate that BCAS2 could interact with hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 to regulate AS in mouse testis.

Fig. 7.

BCAS2 recruits hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 to modulate AS of pre-mRNA Trp53bp1. (A) Venn diagram showing the correlation among BCAS2-binding genes, Bcas2 cKO differentially spliced genes, Hnrnph1 cKO differentially spliced genes and hnRNPH1-binding genes. (B) Expression, hnRNPH1-binding peaks, and BCAS2-binding peaks of Trp53bp1 are shown. Black arrow, direction of transcription. (C) The expression of hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 in 293T cells. The RT‒qPCR data were normalized to GAPDH. The value in the Ctrl group was set as 1.0, and the relative value in the cKO group is indicated. n = 4. (D) Western blotting of hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 expression in 293T cells. GAPDH served as a loading control. The value in the EV group was set as 1.0, and the relative values in other groups are indicated. n = 3. KD, knockdown. EV, empty vector. (E) Analysis of the splicing of Trp53bp1 minigenes by RT‒PCR. The percentages of inclusion (in%, red) and exclusion (ex%, blue) within exon 9 of Trp53bp1 transcripts are presented, respectively. The data are shown as mean ± SEM. n = 4. KD, knockdown. EV, empty vector. ex, exclusion. in, inclusion. (F) Schematic illustration of the molecular mechanisms by which BCAS2 regulates DSBs repair and synapsis during meiotic prophase I. Upregulated genes are depicted in red, while downregulated genes are depicted in blue. Unpaired Student’s t-test determined significance. ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. The points and error bars represent the mean ± SEM

Discussion

The current study marks a significant advancement by unveiling the intricate binding characteristics of BCAS2 in the testis through CLIP-seq analysis. Importantly, the findings shed light on the pivotal role of BCAS2 in post-transcriptional regulation, establishing its direct interaction with crucial genes such as Spo11, Six6os1, Sycp1, Msh5, Cdk2, Sun2, Stag3, and Spdya. This regulatory interaction orchestrates AS, thereby influencing DSBs repair and synapsis during the meiotic prophase I program in mouse germ cells (Fig. 7F).

BCAS2-mediated post-transcriptional regulation influences DSBs repair through SC formation

The tripartite proteinaceous ultrastructure of the SC serves as a linchpin in various stages of meiotic recombination, encompassing the initiation of recombination, feedback control of DSB formation, selection of DSB repair pathways, and crossover (CO) formation [9, 41, 42]. Concomitantly, the genesis of DSBs plays a dual role, promoting both homologous pairing and SC formation [10, 11]. Within the ambit of this study, a nuanced observation unravels a partial defect in the formation of the association complex, yet the capacity for homologous pairing remains steadfast (Fig. 3). Supplementary datasets, encompassing RNA-seq, RT-PCR, and RT-qPCR analyses, provided additional insights into the expression patterns of SC formation-related genes. Notably, downregulation was observed in Syce1l, Syce1, Rec8, and Stag3, while Six6os1 exhibited upregulation, and Sycp1 maintained stability (Fig. 4). Furthermore, aberrant AS events were detected in Six6os1, Sycp1, and Stag3 (Fig. 5C and S6C). Thus, these findings collectively intimate the possibility of an anomaly in SC formation as a contributing factor affecting DSB repair.

BCAS2-mediated AS is extensively involved in the repair of DSBs

Germ cells have intricately evolved a program dedicated to safeguarding genome integrity and transmitting pristine genetic information to subsequent generations [43]. Among the myriad challenges to genomic stability, the DSBs stand out as one of the most formidable threats across various forms of DNA damage [44]. In response to DNA damage, BCAS2 has been demonstrated as a unique negative regulator, capable of interacting with p53 to suppress its activity [28]. Further expanding its repertoire, BCAS2 has been revealed to respond adeptly to DNA damage induced by camptothecin (CPT), engaging in a sophisticated interaction with RPA [45]. Subsequently, these mechanisms were validated in various cellular contexts, encompassing mouse syncytium, oocytes, and granulosa cells [25, 35, 37]. Moreover, BCAS2 has been implicated in the repair of DSBs in prostate cancer, where it interacts with NBS1 [26]. Our study illuminates the role of BCAS2-mediated AS in the intricate processes of DSB formation and repair during meiosis in spermatocytes. Specifically, during SPO11-mediated DSB formation, BCAS2 dynamically modulates the expression of SPO11α and SPO11β by regulating the AS of exon 2 of Spo11 (Fig. 5C). In the subsequent repair phase of DSBs, During the repair of DSBs, BCAS2 is able to directly bind and regulate AS of Trp53bp1, Rif1, and Msh5 (Fig. 5C). Additionally, the dysregulation of DSB repair-related genes in BCAS2-deficient spermatocytes implies that BCAS2 may play a role in other dimensions of post-transcriptional regulation during the DSB repair process (Fig. 4A, B and D, and 5A). Although the specific mechanisms governing this post-transcriptional regulation remain unclear, our findings suggest a significant involvement of BCAS2 in DSB repair through the modulation of AS processes.

Deletion of either Hnrnph1 or Bcas2 in spermatocytes impedes DSBs repair and disrupts synapsis during meiosis

In this investigation, BCAS2 demonstrated its interaction with hnRNPH1 and SRSF3, forming a cooperative partnership in the co-regulation of AS (Fig. 7A). Notably, the minigene reporter analysis provided evidence that BCAS2 collaborates with hnRNPH1 and SRSF3 to co-regulate the AS of pre-mRNA Trp53bp1 (Figs. 6 and 7E). Recent research has elucidated that hnRNPH1 recruits PTBP2 and SRSF3 to modulate AS specifically in germ cells [6]. The observed phenotype in this study, showcasing delayed autosomal DSB repair upon Hnrnph1 deletion in spermatocytes, aligns with findings in hnRNPH1-deficient spermatocytes, where defective synapsis is evident, resembling the phenotype observed after Bcas2 deletion in spermatocytes [6]. Intriguingly, a comprehensive multi-omics analysis of both knockout mice revealed that BCAS2 and hnRNPH1 co-regulate the AS of pre-mRNAs associated with some genes involved in DSB repair and synapsis, such as Spo11, Trp53bp1, and Six6os1 (Figures S7 and 7B). In conclusion, hnRNPH1 emerges as a crucial collaborator with BCAS2, contributing significantly to the AS regulation of DSB repair and synapsis during meiosis.

BCAS2-mediated post-transcriptional regulation during meiosis holds potential for treating human reproductive diseases

This study elucidates the novel regulatory network of BCAS2-mediated AS in germ cells to ensure their genomic integrity, possessing potential value in the treatment of human reproductive diseases (Fig. 7F). In particular, the resolution of BCAS2-mediated AS of pre-mRNAs Spo11 and Trp53bp1 expands the novel role of BCAS2 in the repair of DSBs. The conservation of such mechanism needs further exploration, and once confirmed, it will provide new insights into the treatment of DNA damage-related diseases, especially cancer. However, it could not be demonstrated in the present study due to some limitations. Therefore, we look forward to further investigating this issue in future studies.

In conclusion, our study provides an important theoretical basis as well as data source for understanding the post-transcriptional regulatory mechanism of DNA damage repair during meiosis through pre-mRNA splicing.

Star methods

Mouse strains

C57BL/6 N and ICR mice were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. The generation of Bcas2Fl/Fl mice has been described previously [25]. Stra8-GFPCre mice were kindly provided by Prof. Minghan Tong (Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) [38, 39]. To generate Bcas2 cKO mice, Stra8-GFPCre mice were crossed with Bcas2Fl/Fl mice. The primers used for PCR to genotype Bcas2Fl/Fl and Stra8-GFPCre mice are shown in Table S4. All mice were bred and housed under specific pathogen-free conditions with controlled temperature (22 ± 1 °C) and exposed to a constant 12-hour light-dark cycle in the animal facilities of China Agricultural University. All experiments were conducted according to the guidelines and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of China Agricultural University (No. AW80401202-3-2).

Fertility test

For a duration of 15 days, two 8-week-old ICR female mice were housed together with an 8-week-old male mouse, either Ctrl or cKO. Female mice were examined for the presence of vaginal plugs, and those with plugs were individually housed, with meticulous recording of the dates. The male mice were maintained in separate cages after two days of cohabitation. Daily records were maintained for the number of pups born to each female, along with the respective dates of parturition.

Immunostaining and histologic analysis

The mouse testes were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (P6148-500G, Sigma–Aldrich, Missouri, USA) in PBS (pH 7.4) at 4 °C overnight. Subsequently, the samples underwent dehydration through graded ethanol solutions, vitrification with xylene, and embedding in paraffin. Testis sections, cut at a thickness of 5 μm, were utilized for immunostaining and histologic analysis. For histological assessment, sections were dewaxed in xylene, rehydrated in graded ethanol solutions, and stained with H&E. Following sealing with neutral resin, imaging was performed using a Ventana DP200 system.

For immunofluorescence analysis, antigen retrieval was achieved by microwaving the sections with sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Following blocking with 10% goat serum at room temperature for 1 h, the sections were incubated with primary antibodies in 5% goat serum (Table S5) overnight at 4 °C. After PBS washing, the sections were exposed to secondary antibodies (Table S5) at room temperature in the dark for 1 h. The slides were mounted using an antifade mounting medium with DAPI (P0131, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Imaging was conducted using a Nikon A1 laser scanning confocal microscope and a Zeiss OPTOME fluorescence microscope.

TUNEL apoptosis analysis

Adult testes sections were processed according to the TUNEL Apoptosis Assay Kit protocol (C1088, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Photomicrographs were acquired using a Nikon A1 laser scanning confocal microscope and a Zeiss OPTOME fluorescence microscope. The quantification of TUNEL+ tubules was performed to assess the percentage of apoptotic cells in both cKO and Ctrl adult mouse testes.

Surface spreading

Testis surface spreading was carried out following established procedures [24, 46]. In brief, half of the mouse testes were isolated and treated with 300 µl of TrypLE (12604021, Thermo, New York, US) at 37 °C for 10 min under constant agitation. The digestion process was halted by adding 30 µl fetal bovine serum (C0235, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). After centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 1 min, the supernatant was discarded. The cells underwent treatment with 300 µl hypotonic buffer (30 mM Tris-HCl, 17 mM trisodium citrate dihydrate, 50 mM sucrose, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, pH 8.2) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100, P1005, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for 30 min. Slides were pretreated with 20 µl of fixation buffer (1% paraformaldehyde, pH 9.2 with 50 mM boric acid) containing 0.15% Triton X-100 (T9284, Sigma, Missouri, USA) applied evenly on slides in advance. Subsequently, 20 µl aliquots of the cell suspension were dripped onto the slides, which were then incubated at 37 °C for 4 h or overnight in a humidified box. The samples were left to dry at room temperature, and immunofluorescence staining was performed according to the protocol described above.

Flow cytometry

Following established protocols, STRA8+ cell suspensions were isolated and prepared from mouse testes [24]. Initially, adult Ctrl and cKO testes were subjected to digestion with 500 µl of collagenase IV (1 mg/mL, 40510ES60, Yeasen, Shanghai, China) and DNase I (1 mg/mL, 10104159001, Roche, Mannheim, Germany) at 37 °C for 10 min under constant agitation. Subsequently, the testes were further digested for an additional 10 min after replacing collagenase IV with TrypLE. Finally, STRA8+ cell suspensions from Ctrl and cKO mice were sorted using a FACSAria Fusion (BD Biosciences).

RT–PCR and RT–qPCR

Total RNA extraction was performed using RNAiso Plus (9109, Takara, Kusatsu, Japan) and a Direct-zol RNA MicroPrep kit (R2060, Zymo Research, California, USA), with concentration measured using a Nano-300 ultramicro spectrophotometer (Allsheng, Hangzhou, China). Subsequently, cDNA was synthesized following the instructions of the TIANScript II RT kit (KR107, TIANGEN, Beijing, China). The expression levels of target gene transcripts were quantified using a Light Cycle® 96 instrument (Roche) with Hieff UNICON SYBR green master mix (11198ES08, Yeasen, Shanghai, China). AS analyses were conducted on a RePure-A PCR instrument (BIO-GENER, Hangzhou, China). Primers, synthesized by Sangon Biotech, are listed in Table S4. Gapdh or Actb expression served as the control, with its value set as 1. Relative transcript expression levels for other samples were determined by comparing them with the control results.

RNA-seq

Total RNA extraction from STRA8+ cells followed the outlined protocol. In brief, mRNA was isolated from total RNA using poly-T oligo-attached magnetic beads. Following fragmentation, a transcriptome sequencing library was constructed, and library quality was assessed on an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. Index-coded sample clustering was conducted on a cBot Cluster Generation System using a TruSeq PE Cluster kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina), following the provided instructions. Subsequently, the library preparations were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform, generating 150 bp paired-end reads. After quality control, all downstream analyses were performed on clean, high-quality data.

The reference genome index was established, and HISAT2 software (version 2.0.5) aligned paired-end clean reads to the reference genome. FeatureCounts (version 1.5.0) was employed to count the reads mapped to each gene. Subsequently, the fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) value of each gene was calculated based on the gene length and the read count mapped to it. The DESeq2 R package (version 1.20.0) conducted differential expression analysis of cKO/Ctrl STRA8+ cells (three biological replicates per condition). Genes with a padj < 0.05 and |log2FoldChange| > 1, as identified by DESeq2, were considered differentially expressed.

AS analysis

The rMATS software (version 3.2.5) was employed for the analysis of AS events in cKO mouse germ cells utilizing RNA-seq data. The software identified five types of AS events, including SE, RI, MXE, A5SS, and A3SS. The threshold set for screening differentially significant AS events was a false discovery rate (FDR) of less than 0.05. Splicing events with an FDR less than 0.05 and an inclusion-level difference showing significance of at least 5% (0.05) were considered statistically significant. To confirm and visualize AS events based on RNA-seq data, the IGV (Version 2.16.0) was utilized.

GO term enrichment analysis

The GO enrichment analysis for both differentially expressed genes and AS genes was conducted using the clusterProfiler R package (version 3.4.4). This analysis corrected for gene length bias. The mouse genome data (GRCm38/mm10) served as the reference, and the Benjamini–Hochberg method was applied for multiple testing correction. This approach helps identify and interpret the biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components associated with the genes of interest.

Western blotting

Total protein extraction was performed using cell lysis buffer (P0013, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), supplemented with PMSF (1:100, ST506, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100, P1005, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). The protein concentration was measured using a BCA protein assay kit (CW0014S, CWBiotech, Beijing, China). Subsequently, protein lysates were separated through sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore, Ireland). After blocking with 5% skimmed milk for 1 h, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies (Table S5) overnight at 4 °C. Following this, the membranes were exposed to secondary antibodies (Table S5) at room temperature for 1 h. Protein visualization was achieved using the Tanon 5200 chemiluminescence imaging system following incubation with BeyoECL Plus (P0018S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China).

IP, IP-MS, and Co-IP

As previously outlined, total protein was extracted using cell lysis buffer (P0013, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) supplemented with PMSF (1:100, ST506, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (1:100, P1005, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) [23, 24]. After 20 min of incubation on ice, the lysate was combined with 20 µl of protein A agarose (P2051-2 ml, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for pre-clearing at 4 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 2 micrograms of a BCAS2 antibody (PA2466, Abmart, Shanghai, China) and a normal rabbit IgG (A7016, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) were added to the lysate, followed by overnight incubation at 4 °C. On the next day, 60 µl of protein A agarose was introduced to the lysate, followed by a 4-hour incubation at 4 °C. The agarose complexes containing antibodies and target proteins underwent three washes for 5 min each at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitation (IP) and Co-IP were conducted following the Western blotting protocol mentioned earlier. The resulting complex was sent to the protein mass spectrometry laboratory for IP-MS analyses using a Thermo Q-Exactive high-resolution mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham). Raw data from the mass spectrometer were preprocessed with Mascot Distiller 2.4 for peak picking, and the resulting peak lists were searched against the UniProt mouse database using the Mascot 2.5 search engine.

RIP and RIP–qPCR

As previously described, RIP was conducted using 14 dpp mouse testes [24, 47]. The testes were lysed in cell lysis buffer (P0013, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), supplemented with PMSF (1:100, ST506, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), a proteinase inhibitor cocktail (1:100, P1005, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), DTT (1:50, ST041-2 ml, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and an RNase inhibitor (1:20, R0102-10 kU, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Following a 20-minute incubation on ice, the lysate was combined with 20 µl of protein A agarose (P2051-2 ml, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for pre-clearing at 4 °C for 1 h. Subsequently, 2 micrograms of a BCAS2 antibody (PA2466, Abmart, Shanghai, China) and normal rabbit IgG (A7016, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) were introduced to the lysate, followed by an overnight incubation at 4 °C. On the subsequent day, 60 µl of protein A agarose was added to the lysate, and the mixture was incubated at 4 °C for 4 h. The agarose complexes, encompassing antibodies, target proteins, and RNA, underwent a 5-minute wash at 4 °C, repeated three times. Protein-bound RNA was extracted using RNAiso Plus and the Direct-zol RNA MicroPrep kit. RIP–qPCR analysis was performed following the aforementioned RT–qPCR protocol.

irCLIP-seq

Seminiferous tubules were isolated from adult WT C57BL/6 N mice testes, and ultraviolet light (254 nm) was employed to cross-link the tubules, ensuring the covalent binding of RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) to their cognate RNAs. Following this, BCAS2 and the cross-linked RNAs were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-BCAS2 antibody and subsequently digested with Micrococcal nuclease (catalog no. EN0181, Thermo Fisher Scientific). An IR800-biotin adapter was ligated to the 3′ ends of the RNA fragments. The BCAS2/RNA complexes, ranging from approximately 47 to 62 kDa, were separated by SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (catalog no. HATF00010, Millipore). Subsequently, RNA and protein complexes were extracted from the nitrocellulose membrane and subjected to proteinase K digestion (catalog no. 9034, TaKaRa). RNAs were isolated using saturated phenol (catalog no. AM9712, Ambion), ligated with adaptors, and converted to cDNAs using the SuperScript III First-Strand Kit (catalog no. 18080-051, Invitrogen). The cDNAs were then amplified by PCR to generate the respective libraries, followed by sequencing on the HiSeq 2500 Illumina platform.

For the analysis of CLIP-seq data, reads were initially trimmed of adaptor sequences using Trimmomatic (version 0.36). Subsequently, bowtie 2 (version 2.1.0) was utilized to map clean reads to the mm10 reference genome with the following parameters: “-p 10 -L 15 -N 1 -D 50 -R 50 --phred33 --qc-filter --very-sensitive --end-to-end.” CLIP-seq peaks were identified using Piranha (version 1.2.1) with the parameters: “-s -b 20 -d Zero Truncated Negative Binomial -p 0.05.”

Homer (version 4.9.1) was employed for peak annotation based on the mm10 genome assembly and for the analysis of BCAS2-binding motifs. The quality of replicates was assessed by calculating the pairwise Spearman correlation coefficient.

Minigene reporter assay

Minigene reporter assay was performed as described previously [24, 48]. The WT Trp53bp1 minigene was constructed by inserting an additional 3871 bp from exons 8, 9, and 10 (corresponding to chr2: 121,248,163 − 121,252,027 mm10) into pcDNA3.0 vector between the Asc I and Pac I sites. The plasmids containing the mutant-binding site of Bcas2 were cloned with appropriate primers adjacent to the binding site using the site-directed mutagenesis approach. To generate the expression plasmid for Bcas2, the CDS region of Bcas2 was amplified and cloned into the pcDNA3.0 vector with Asc I and Pac I sites. To generate the BCAS2 knockdown vector, the designed sequence for producing BCAS2 short hairpin RNA was amplified and cloned into pMKO.1 vector with Age I and Eco RI sites. 293T cells were transfected with the BCAS2-expressing or knockdown plasmid together with indicated minigene plasmids using Lipo8000™ (C0533-1.5 ml, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) following the provided instructions. The transfected cells were harvested for RNA and protein analyses 24 h later. RT–PCR was performed with primers amplifying endogenous transcripts.

Statistical analysis

Pearson’s correlation coefficients (R) were calculated utilizing RNA-seq, CLIP-seq, and IP-MS data. To compare the distributions of CLIP-seq signals for two sets of genes, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was employed. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.0.0), and the presented values and error bars represent the mean ± SEM. Significant differences between the two groups were assessed using Student’s t-test, with statistical significance considered as follows: Exact P value P ≥ 0.05; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Minghan Tong (Shanghai Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China) for sharing Stra8-GFPCre mice, Prof. Shuyang Yu (China Agricultural University, Beijing, China) for sharing plasmids, Prof. Mengcheng Luo (Wuhan University, Wuhan, China) for sharing antibodies, Prof. Hua Zhang and Chao Wang (China Agricultural University, Beijing, China) for thoughtful discussions and suggestions, and all the members of Prof. Hua Zhang, Chao Wang, and Shuyang Yu laboratory for helpful discussions and comments. We thank Novogene for their assistance with the RNA-seq experiments.

Author contributions

The entire project was conceived and designed by LS, SC, YX, LL, JC, and JL. LS, RY, ZL, CW, XX, XC, XY, ST, LY, and YS conducted the experiments, while LS, ZL, and CW were involved in mouse breeding. LS, RY, ChangC, ChenC, ZL, JC, and JL analyzed the data. LS, JC, and JL contributed to manuscript writing. All authors actively participated in result discussions, provided comments on the manuscript, and read and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No.32171111 to J.L.], the Beijing Natural Science Foundation [No.5222015 to J.L.], the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No.32130064 and 32025008 to Y.X.], and the 2115 Talent Development program of China Agricultural University.

Data availability

All data produced or examined during this investigation are comprehensively presented in this published article, its supplementary information files, and openly accessible repositories. The RNA-seq and CLIP-seq datasets have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession number GSE254464.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All experiments were conducted following the guidelines and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of China Agricultural University (No. AW80401202-3-2).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Longjie Sun, Rong Ye, Changchang Cao, Zheng Lv and Chaofan Wang contributed equally to this work.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yuanchao Xue, Email: ycxue@ibp.ac.cn.

Lei Li, Email: lil@ioz.ac.cn.

Juan Chen, Email: chenjuan.09@163.com.

Jiali Liu, Email: liujiali@cau.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ito M, Shinohara A (2022) Chromosome architecture and homologous recombination in meiosis. Front Cell Dev Biol 10:1097446. 10.3389/fcell.2022.1097446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keeney S, Giroux CN, Kleckner N (1997) Meiosis-specific DNA double-strand breaks are catalyzed by Spo11, a member of a widely conserved protein family. Cell 88(3):375–384. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81876-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Bergerat A, de Massy B, Gadelle D, Varoutas PC, Nicolas A, Forterre P (1997) An atypical topoisomerase II from Archaea with implications for meiotic recombination. Nature 386(6623):414–417. 10.1038/386414a0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Bellani MA, Boateng KA, McLeod D, Camerini-Otero RD (2010) The expression profile of the major mouse SPO11 isoforms indicates that SPO11β introduces double strand breaks and suggests that SPO11α has an additional role in prophase in both spermatocytes and oocytes. Mol Cell Biol 30(18):4391–4403. 10.1128/Mcb.00002-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Kauppi L, Barchi M, Baudat F, Romanienko PJ, Keeney S, Jasin M (2011) Distinct properties of the XY pseudoautosomal region crucial for male meiosis. Science 331(6019):916–920. 10.1126/science.1195774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Feng SL, Li JM, Wen H, Liu K, Gui YQ, Wen YJ, Wang XL, Yuan SQ (2022) hnRNPH1 recruits PTBP2 and SRSF3 to modulate alternative splicing in germ cells. Nat Commun 13(1):3588. 10.1038/s41467-022-31364-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Cesari E, Loiarro M, Naro C, Pieraccioli M, Farini D, Pellegrini L, Pagliarini V, Bielli P, Sette C (2020) Combinatorial control of Spo11 alternative splicing by modulation of RNA polymerase II dynamics and splicing factor recruitment during meiosis. Cell Death Dis 11(4):240. 10.1038/s41419-020-2443-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ur SN, Corbett KD (2021) Architecture and dynamics of meiotic chromosomes. Annu Rev Genet 55:497–526. 10.1146/annurev-genet-071719-020235 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Zhang F, Liu M, Gao J (2022) Alterations in synaptonemal complex coding genes and human infertility. Int J Biol Sci 18(5):1933–1943. 10.7150/ijbs.67843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanzione M, Baumann M, Papanikos F, Dereli I, Lange J, Ramlal A, Tränkner D, Shibuya H, de Massy B, Watanabe Y et al (2016) Meiotic DNA break formation requires the unsynapsed chromosome axis-binding protein IHO1 (CCDC36) in mice. Nat Cell Biol 18(11):1208–1220. 10.1038/ncb3417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson KA, Keeney S (2004) Tying synaptonemal complex initiation to the formation and programmed repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101(13):4519–4524. 10.1073/pnas.0400843101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Wang G, Wu X, Zhou L, Gao S, Yun D, Liang A, Sun F (2020) Tethering of telomeres to the Nuclear envelope is mediated by SUN1-MAJIN and possibly promoted by SPDYA-CDK2 during meiosis. Front Cell Dev Biol 8:845. 10.3389/fcell.2020.00845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee CY, Horn HF, Stewart CL, Burke B, Bolcun-Filas E, Schimenti JC, Dresser ME, Pezza RJ (2015) Mechanism and regulation of rapid telomere prophase movements in mouse meiotic chromosomes. Cell Rep 11(4):551–563. 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Krejci L, Altmannova V, Spirek M, Zhao X (2012) Homologous recombination and its regulation. Nucleic Acids Res 40(13):5795–5818. 10.1093/nar/gks270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao J, Colaiacovo MP (2018) Zipping and unzipping: protein modifications regulating synaptonemal complex dynamics. Trends Genet 34(3):232–245. 10.1016/j.tig.2017.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Liu H, Huang T, Li M, Li M, Zhang C, Jiang J, Yu X, Yin Y, Zhang F, Lu G et al (2019) SCRE serves as a unique synaptonemal complex fastener and is essential for progression of meiosis prophase I in mice. Nucleic Acids Res 47(11):5670–5683. 10.1093/nar/gkz226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hughes SE, Hawley RS (2020) Alternative synaptonemal complex structures: too much of a good thing? Trends Genet 36(11):833–844. 10.1016/j.tig.2020.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ishiguro KI (2019) The cohesin complex in mammalian meiosis. Genes Cells 24(1):6–30. 10.1111/gtc.12652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Wu Y, Li Y, Murtaza G, Zhou J, Jiao Y, Gong C, Hu C, Han Q, Zhang H, Zhang Y et al (2021) Whole-exome sequencing of consanguineous families with infertile men and women identifies homologous mutations in SPATA22 and MEIOB. Hum Reprod 36(10):2793–2804. 10.1093/humrep/deab185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan S, Jiao Y, Khan R, Jiang X, Javed AR, Ali A, Zhang H, Zhou J, Naeem M, Murtaza G, Li Y, Yang G, Zaman Q, Zubair M, Guan H, Zhang X, Ma H, Jiang H, Ali H, Dil S, Shah W, Ahmad N, Zhang Y, Shi Q (2021) Homozygous mutations in C14orf39/SIX6OS1 cause non-obstructive azoospermia and premature ovarian insufficiency in humans. Am J Hum Genet 108(2):324–336. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Krausz C, Riera-Escamilla A, Moreno-Mendoza D, Holleman K, Cioppi F, Algaba F, Pybus M, Friedrich C, Wyrwoll MJ, Casamonti E, Pietroforte S, Nagirnaja L, Lopes AM, Kliesch S, Pilatz A, Carrell DT, Conrad DF, Ars E, Ruiz-Castañé E, Aston KI, Baarends WM, Tüttelmann F (2020) Genetic dissection of spermatogenic arrest through exome analysis: clinical implications for the management of azoospermic men. Genet Medicine: Official J Am Coll Med Genet 22(12):1956–1966. 10.1038/s41436-020-0907-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Hou D, Yao C, Xu B, Luo W, Ke H, Li Z, Qin Y, Guo T (2022) Variations of C14ORF39 and SYCE1 identified in idiopathic premature ovarian insufficiency and Nonobstructive Azoospermia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 107(3):724–734. 10.1210/clinem/dgab777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun L, Lv Z, Chen X, Wang C, Lv P, Yan L, Tian S, Xie X, Yao X, Liu J, Wang Z, Luo H, Cui S, Liu J (2023) SRSF1 regulates primordial follicle formation and number determination during meiotic prophase I. BMC Biol 21(1):49. 10.1186/s12915-023-01549-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Sun L, Chen J, Ye R, Lv Z, Chen X, Xie X, Li Y, Wang C, Lv P, Yan L, Tian S, Yao X, Chen C, Cui S, Liu J (2023) SRSF1 is crucial for male meiosis through alternative splicing during homologous pairing and synapsis in mice. Sci Bull 68(11):1100–1104. 10.1016/j.scib.2023.04.030 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Xu Q, Wang F, Xiang Y, Zhang X, Zhao Z-A, Gao Z, Liu W, Lu X, Liu Y, Yu X-J, Wang H, Huang J, Yi Z, Gao S, Li L (2015) Maternal BCAS2 protects genomic integrity in mouse early embryonic development. Development 142(22):3943–3953. 10.1242/dev.129841 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Wang LP, Chen TY, Kang CK, Huang HP, Chen SL (2020) BCAS2, a protein enriched in advanced prostate cancer, interacts with NBS1 to enhance DNA double-strand break repair. Br J Cancer 123(12):1796–1807. 10.1038/s41416-020-01086-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Yu S, Jiang T, Jia D, Han Y, Liu F, Huang Y, Qu Z, Zhao Y, Tu J, Lv Y et al (2019) BCAS2 is essential for hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell maintenance during zebrafish embryogenesis. Blood 133(8):805–815. 10.1182/blood-2018-09-876599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo PC, Tsao YP, Chang HW, Chen PH, Huang CW, Lin ST, Weng YT, Tsai TC, Shieh SY, Chen SL (2009) Breast cancer amplified sequence 2, a novel negative regulator of the p53 tumor suppressor. Cancer Res 69(23):8877–8885. 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-09-2023 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Chen P-H, Lee C-I, Weng Y-T, Tarn W-Y, Tsao Y-P, Kuo P-C, Hsu P-H, Huang C-W, Huang C-S, Lee H-H, Wu J-T, Chen S-L (2013) BCAS2 is essential for Drosophila viability and functions in pre-mRNA splicing. RNA (New York NY) 19(2):208–218. 10.1261/rna.034835.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Chen HR, Tsao TY, Chen CH, Tsai WY, Her LS, Hsu MM, Cheng SC (1999) Snt309p modulates interactions of Prp19p with its associated components to stabilize the Prp19p-associated complex essential for pre-mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96(10):5406–5411. 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Chen HR, Jan SP, Tsao TY, Sheu YJ, Banroques J, Cheng SC (1998) Snt309p, a component of the Prp19p-associated complex that interacts with Prp19p and associates with the spliceosome simultaneously with or immediately after dissociation of U4 in the same manner as Prp19p. Mol Cell Biol 18(4):2196–2204. 10.1128/mcb.18.4.2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Kabrani E, Saha T, Di Virgilio M (2023) DNA repair and antibody diversification: the 53BP1 paradigm. Trends Immunol 44(10):782–791. 10.1016/j.it.2023.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie C, Wang W, Tu C, Meng L, Lu G, Lin G, Lu LY, Tan YQ (2022) Meiotic recombination: insights into its mechanisms and its role in human reproduction with a special focus on non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod Update 28(6):763–797. 10.1093/humupd/dmac024 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Liu W, Wang F, Xu Q, Shi J, Zhang X, Lu X, Zhao Z-A, Gao Z, Ma H, Duan E, Gao F, Gao S, Yi Z, Li L (2017) BCAS2 is involved in alternative mRNA splicing in spermatogonia and the transition to meiosis. Nat Commun 8:14182. 10.1038/ncomms14182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Zhang JQ, Liu WB, Li GY, Xu CP, Nie XQ, Qin DD, Wang QZ, Lu XK, Liu JQ, Li L (2022) BCAS2 is involved in alternative splicing and mouse oocyte development. Faseb J 36(2):e22128. 10.1096/fj.202101279R [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Chen X, Xie X, Li J, Sun L, Lv Z, Yao X, Li L, Jin H, Cui S, Liu J (2023) BCAS2 participates in insulin synthesis and secretion via mRNA alternative splicing in mice. Endocrinology 165(1):bqad152. 10.1210/endocr/bqad152. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Yao X, Wang C, Sun L, Yan L, Chen X, Lv Z, Xie X, Tian S, Liu W, Li L et al (2023) BCAS2 regulates granulosa cell survival by participating in mRNA alternative splicing. J Ovarian Res 16(1):104. 10.1186/s13048-023-01187-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin Z, Hsu PJ, Xing X, Fang J, Lu Z, Zou Q, Zhang K-J, Zhang X, Zhou Y, Zhang T, Zhang Y, Song W, Jia G, Yang X, He C, Tong M-H (2017) Mettl3-/Mettl14-mediated mRNA N(6)-methyladenosine modulates murine spermatogenesis. Cell Res 27(10):1216–1230. 10.1038/cr.2017.117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Chen Y, Zheng Y, Gao Y, Lin Z, Yang S, Wang T, Wang Q, Xie N, Hua R, Liu M et al (2018) Single-cell RNA-seq uncovers dynamic processes and critical regulators in mouse spermatogenesis. Cell Res 28(9):879–896. 10.1038/s41422-018-0074-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan Y, Zhang D, Zhou P, Li B, Huang SY (2017) HDOCK: a web server for protein-protein and protein-DNA/RNA docking based on a hybrid strategy. Nucleic Acids Res 45(W1):W365–w373. 10.1093/nar/gkx407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Zhang FG, Zhang RR, Gao JM (2021) The organization, regulation, and biological functions of the synaptonemal complex. Asian J Androl 23(6):580–589. 10.4103/aja202153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Woglar A, Villeneuve AM (2018) Dynamic Architecture of DNA repair complexes and the Synaptonemal Complex at sites of Meiotic recombination. Cell 173(7):1678–1691e1616. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Sabour D, Schöler HR (2012) Reprogramming and the mammalian germline: the Weismann barrier revisited. Curr Opin Cell Biol 24(6):716–723. 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Rübe CE, Zhang S, Miebach N, Fricke A, Rübe C (2011) Protecting the heritable genome: DNA damage response mechanisms in spermatogonial stem cells. DNA Repair 10(2):159–168. 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Wan L, Huang J (2014) The PSO4 protein complex associates with replication protein A (RPA) and modulates the activation of ataxia telangiectasia-mutated and Rad3-related (ATR). J Biol Chem 289(10):6619–6626. 10.1074/jbc.M113.543439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peters AH, Plug AW, van Vugt MJ, de Boer P (1997) A drying-down technique for the spreading of mammalian meiocytes from the male and female germline. Chromosome Res 5(1):66–68. 10.1023/a:1018445520117 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Gagliardi M, Matarazzo MR (2016) RIP: RNA immunoprecipitation. Methods Mol Biol 1480:73–86. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6380-5_7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Qi Z, Wang F, Yu G, Wang D, Yao Y, You M, Liu J, Liu J, Sun Z, Ji C, Xue Y, Yu S (2021) SRSF1 serves as a critical posttranscriptional regulator at the late stage of thymocyte development. Sci Adv 7(16):eabf0753. 10.1126/sciadv.abf0753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data produced or examined during this investigation are comprehensively presented in this published article, its supplementary information files, and openly accessible repositories. The RNA-seq and CLIP-seq datasets have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under the accession number GSE254464.