Abstract

Background

Professional voice users often experience stigma associated with voice disorders and are reluctant to seek medical help. This study deployed empirical and computational tools to (1) quantify the experience of vocal stigma and help-seeking behaviors in performers; and (2) predict their modulations with peer influences in social networks.

Methods

Experience of vocal stigma and information-motivation-behavioral (IMB) skills were prospectively profiled using online surveys from a total of 403 Canadians (200 singers and actors and 203 controls). Data were used to formulate an agent-based network model of social interactions on vocal stigma (self-stigma and social-stigma) and help-seeking behaviors. Network analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of social network structure on the flow of IMB among virtual agents.

Results

Larger social networks are more likely to contribute to an increase in vocal stigma. For small social networks, total stigma is reduced with higher total IMB but not much so for large networks. For agents with high social-stigma and risk for voice disorder, their vocal stigma is resistant to large changes in IMB ( > 2 standard deviations). Agents with extreme IMB and stigma values are likely to polarize their networks faster in larger social groups.

Conclusions

We integrated empirical surveys and computational techniques to contextualize vocal stigma and IMB beyond theory and to quantify the interaction among stigma, health-seeking behavior and influence of social interactions. This work establishes an effective, predictable experimental platform to provide scientific evidence in developing interventions to reduce health stigma in voice disorders and other medical conditions.

Subject terms: Epidemiology, Epidemiology, Rehabilitation

Plain language summary

Voice professionals such as singers and actors can experience stigma if they have a voice disorder. This stigma can result from their personal experience and knowledge (internalized) or be based on input from their peers, employment, and healthcare providers (externalized). To understand how negative vocal stigma spreads, we surveyed the stigma experience of voice professionals and developed computational models. We find that people tend to have more polarized stigma experiences when they are in larger social groups. Vocal stigma is not changed by a person’s knowledge, beliefs, and tendency to seek help. Our method could be used to study other stigmatized health conditions. Our research could also be used to reduce stigma and promote more equitable health care for vocal professionals with a voice disorder.

Glick et al. investigate the stigma experience and help-seeking behavior in professional singers and actors using de novo data and social simulation. They find that vocal performers experience greater discrimination against their vocal injury with simulation data also predicting that vocal stigma could be worsened with larger social groups.

Introduction

Professional voice users or vocal athletes, such as singers and vocal performers, have an unusual vocal demand at work, putting them at a very high risk of vocal injury. Depending on the severity, their vocal folds may have hemorrhage or develop a benign lesion like nodules and polyps. Afflicted individuals may experience partial or complete loss of voice, pain or tension around the neck, loss of range when performing, and so on1. The estimated lifetime prevalence of voice disorders is alarmingly high in vocal athletes, 46% in singers2, 59% in voice acting students3, etc. They also report devastating physical and emotional difficulties as well as challenges in professional and career development4–7.

Vocal athletes constitute a large labor force in Canada and elsewhere8–12. More than 35,000 of them are employed in Canada as of 20163,13. Singers and actors are highly susceptible to vocal injuries given their highly demanding rehearsal and performance schedules14. Up to 80% of them have experienced vocal illness at least once in their lifetime4,5,15. They also report devastating physical and emotional difficulties as well as challenges in career development4–7. Reduction in voice disorders for professional voice users would improve patient well-being and reduce the healthcare burden on society.

Stigma is considered a serious threat to population health inequalities as it disrupts resource availability, social relationships, and coping behaviors within society16. Individuals with a stigmatized medical condition may become reluctant to seek medical help17. For example, a meta-analysis on mental health stigma found a negative correlation between stigma and help-seeking18. Similarly, a meta-analysis of stigma and health outcomes in HIV/AIDS found that those who experience symptoms of stigma were 21% less likely to access health and social services19. Individual studies also found associations between stigma and avoidance or delaying of help-seeking in other health issues, including alcoholism20 and cancers21.

Similarly, stigma against vocal illness, i.e., vocal stigma, is a known barrier to vocal performers seeking help for work-related illness. Feelings of stigma, judgment, and shame were reported to be pervasively associated with voice disorders within the vocal performing community. With these negative labels, vocal performers felt isolated and hesitated to disclose their vocal injury22. The negative social-stigma of vocal illness among singers and actors is rooted from the fear of judgment as having poor vocal techniques that will damage the performer’s reputation and career longevity. Vocal performers reported higher rates of social isolation, anxiety, and depression than other occupational voice users with work-related vocal illness23,24. The stigma against vocal illness not only negatively affects a person’s mental and physical health, but also has repercussions at the legal and corporate levels. For instance, over 85% of Broadway singers did not disclose their vocal illness to employers or file workers’ compensation claims23. Some would rather use sick days instead of injury leave. As the injury-related information is not reported to the managing company, the performers’ lost time will not be calculated into the production’s running costs. The production company has thus no monetary incentive to provide therapeutic services.

The health stigma and discrimination framework proposed by Stangl et al. described a hierarchy of social levels on which stigma operates, and a series of processes leading from the creation of a stigma to its measurable outcomes25. In brief, the framework consists of a multi-level social hierarchy, namely, individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and public policy. Within this hierarchy, the stigmatization process starts with constituent factors that drive or facilitate health stigma. Then, individuals with a specific health condition are marked or labeled with a stigma, followed by manifestations, i.e., attitudes, behaviors, and experiences that arise from the stigma in those who are marked by the stigma and those around them. Finally, the stigma manifestations affect a range of measurable outcomes on affected populations (e.g., access to healthcare) and society (e.g., public policies against discrimination)25. In this context, our conception of vocal stigma includes all aspects of the theorized construct of stigma via power dynamics, which include labeling, stereotyping, separation from peers, and loss of status and discrimination due directly from the vocal problem as proposed by ref. 26.

By adopting Stangl et al.’s framework to vocal stigma, vocal performers with vocal impairments can entail catastrophic fears about losing the employment, social status, and creative fulfillment that their art provides27. In other words, they fear the consequences of not being able to meet the vocal demands of performance. This fear is a strong candidate for a driving factor in vocal stigma among vocal performers. However, individuals face different vocal demands and consequences for being unable to perform. For example, actors and singers face different vocal demands, and full-time performers face greater consequences from voice disorders than those who have other sources of income.

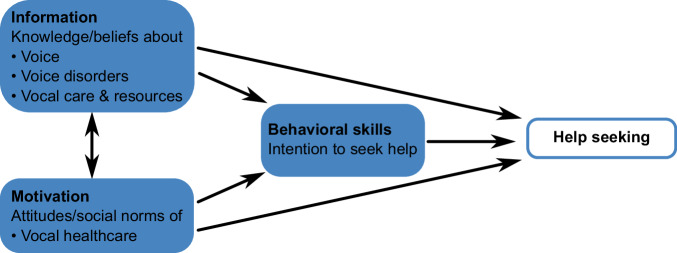

Predicting help-seeking and other behaviors that influence health is a major topic in the field of health psychology28. One prominent psychological model for making these predictions is the information motivation behavioral skills (IMB) model29. Information represents a person’s knowledge and beliefs about the behavior, and about the issue that the behavior is intended to address. Motivation represents a person’s attitudes toward the predicted behavior, and their perception of social norms around it, i.e., what attitudes does the person believe other people hold? An example can be the perceived costs and benefits of the behavior. Behavioral Skills represent a person’s ability to perform the behavior. This component can include objective skills, psychological skills, and, more importantly, self-efficacy, i.e., a person’s intention to seek help30.

By applying this IMB model to vocal stigma, information includes a person’s knowledge and beliefs about voice disorders and related issues. Motivation includes a person’s attitudes and perception of social norms about seeking professional medical help for a voice disorder. Finally, behavioral skills represent the intention to seek professional medical help if they acquire a voice disorder.

In response to the well-recognized health challenges presented by stigma, various strategies have been proposed to reduce the stigma around conditions such as HIV and mental illness. At the level of social-stigma, one common approach is to provide information about a health condition to the general public, emphasizing that affected individuals are not to blame for their condition. Other interventions include promoting empathy and understanding toward affected individuals, for example, via testimonials or social contact between affected and unaffected individuals. For self-stigma, a provision of counseling or coping strategies can also be implemented for affected individuals31–33.

Of these, social contact has emerged as the most successful strategy for reducing stigma in adults31,34. Computer simulation has emerged as a powerful, quantitative way to study social networks and their effects on human behavior and public policy. In fact, social networks have been investigated as a structural determinant of health on their role in the spread of social behaviors and attitudes affecting health outcomes35. For instance, testable models have been developed to simulate the mechanisms of misinformation, bias, and polarization in social networks36,37, characterize the effects of misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic38, and help understand stigma and its impact on obesity, depression, mental illness, heart disease, and HIV-prevention39–42.

In particular, agent-based models (ABM) have become a pivotal simulation platform in social and behavioral sciences in the fast-growing field of social computing43–45. ABM have been applied for building and testing theories in stock markets46–48, consumer behaviors49–54, and psychological cooperation55–58. For driver behaviors in particular59–67, ABMs are used to simulate how the behavior of a driver (an individual agent) will affect other drivers (other agents) and the evolving traffic patterns (emergent population behavior). Rather than individual isolated decisions, social behaviors often resulted from interactions among people with diverse backgrounds over time. Such characteristics match very well with the framework of ABMs.

In essence, an ABM is built up by a collection of entities called agents, whose state and behavior are governed by a set of computational rules. Agents live in the virtual world, which is discretized into grids, or patches. Each patch is a certain situation or a physical environment that an agent lives in. In the application of social behaviors, each agent can represent an individual person with distinctive features with respect to demography, psychology, and social history. Second, an individual agent makes its own decision and adapts the behavior to the environment over time, that effectively represents the dynamics of social and physical influences on human behavior in the real world44. Lastly, ABM is technically flexible for users to explore a wide parameter space and a long temporal scale, which otherwise would be very costly or, at times, prohibitive with empirical experiments. For example, ABM can simulate human interactions in social networks with the ability to control network sizes, type, and frequency of interaction, and observe individual and group outcomes from weeks to years. At the time of writing, current vocal health-related ABMs have focused on studying cellular and molecular behavior in laryngeal systems68–76. ABM or other computer simulation methods (e.g., system dynamics) related to social stigmatization or de-stigmatization are barely reported77,78.

In this study, we investigate the experience of vocal stigma in professional voice users using empirical survey questionnaires and computer network models. The primary focus is to predict how peer interactions could affect an individual’s help-seeking behaviors and vocal stigma experience, especially in vocal performers. We seek answers to the following research questions: (1) if vocal stigma decreases when there are larger social groups; (2) if vocal stigma decreases when peers are more willing to socially interact; and (3) how social network structure impacts IMB and stigma.

Our survey data show that vocal stigma was driven more by external pressures (i.e., social-stigma) than by internal belief (i.e., self-stigma) in professional singers and actors. Our network simulations further predict that the stigmatization of vocal illness could be notably accelerated and polarized with the expansion of social networks. With a better understanding of vocal stigma, clinicians, social epidemiologists and public health policy makers will be more informed when devising interventions aimed at reducing vocal stigma and improving access to voice healthcare.

Methods

Empirical study of vocal stigma profiling

Ethical considerations

This cross-sectional survey study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at McGill University (Study A09-B73-20A) and was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants online prior to participation. The study team has complied with all relevant ethical regulations.

Survey development and deployment

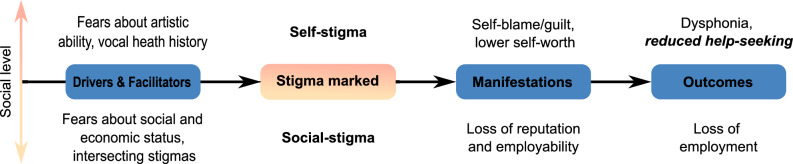

The survey design was based on the health stigma and discrimination framework25 (Fig. 1) and the information-motivation-behavioral skills model29 (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1. Proposed health stigma and discrimination framework for vocal stigma.

Plausible drivers and facilitators contribute to the process of vocal stigmatization. The top of the diagram shows internalized stigma, or self-stigma, and the manifestations and outcomes related to internalizing vocal stigma. The bottom of the diagram outlines how externalized stigma, or social-stigma, manifests and leads to outcomes in a social context. Adapted from ref. 25.

Fig. 2. Proposed information motivation behavioral skills model of predicting help-seeking behavior for voice disorders.

Adopted from ref. 29.

The vocal stigma questionnaire was developed in consultation with an expert panel, including (a) a speech-language pathologist with over 10 years of experience working with clinical voice disorders; and (b) three professional vocal performers (one actor, one singer, one actor/singer; each with over 20 years of experience) from the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television and Radio Artists (ACTRA) or the National Association of Teachers of Singing (NATS). The questionnaire consisted of a total of 64 items to survey individuals’ demographics (six items), occupation and training (three items), vocal health history (14 items), IMB profile (30 items, 10 each for information, motivation, and behavioral skills), experiences of vocal stigma (ten items, five each for social-stigma and self-stigma) plus a single, open item for feedback (Supplementary Methods). The survey was deployed via LimeSurvey, Version 3 (LimeSurvey GmbH, Hamburg, Germany), an open-source survey tool housed at McGill University. The survey took participants around 10–15 min to complete all items.

In this survey, the term of voice disorders was described as a wide range of conditions that impact a person’s voice in various ways, including tone, pitch, loudness, and more. For this study, we further referred to a voice disorder that interferes with a person’s daily conversation and/or professional work as a vocal performer. Specific vocal pathology was not sought in this study as corresponding clinical diagnosis would require access to medical information. For the stigma-related items, self-stigma questions were adapted from the work of Vogel et al. (e.g., I would feel worse about myself if I could not solve my voice problems on my own.)79 and Rosen et al. (e.g., If I had a voice problem, I would blame myself.)27. Social-stigma questions were based on the work of Clough et al.80, Bradshaw and Cooper81, Sataloff et al.82, and Sloggy et al. (e.g., My professional reputation would suffer if I went to a vocal health professional.)83.

Participant recruitment and compensation

A convenience sample of professional vocal performers and gender-matched controls were recruited for the online survey study. Professional vocal performers were recruited through membership offices of ACTRA and NATS. For this study, professional vocal performers were defined as those receiving at least part of their income via singing or acting performance. For the gender-matched control group, an online recruiting platform Prolific (www.prolific.co) was used for recruiting non-vocal performers to the study. Non-vocal performers were defined as receiving no income via singing or acting performance and having no past or present employment in the arts sector listed in their participant profiles on Prolific. Gender as reported by the individual was collected in surveys, and was analyzed for demographic comparison across groups.

Participants without a valid Canadian postal code were excluded from this study because an individual’s stigma experience and tendency to seek help are specific to their own countries’ healthcare systems. Participants were also excluded if they had a history of vocal pathology arising from cancer, stroke, degenerative neurological conditions, or physical trauma to the throat, head, and neck.

Interested individuals would first need to answer a set of screening questions to ensure their eligibility on LimeSurvey. Eligible participants were directed to the consent form, in which the general purpose of the study was described. Explicit reference to stigma was omitted to avoid response biases. A debrief with the full purpose of the study was disclosed to participants at the end of the questionnaire, at which time they could opt to withdraw their data from the study. In this study, no opt-outs were requested at the end.

In terms of compensation, individuals in the vocal performer group, were given the choice to enter a raffle for gift cards (each CAD $50) by following an external link and providing their email address at the end of the study. Participants in the control group were paid CAD $5 via the Prolific platform.

Data privacy

All data were collected anonymously and were stored on a secure server, hosted by McGill University. Participant data did not contain any identifying information. The emails in the gift card raffle were not linked to individual participant data. Participant identity was thus not traceable or identifiable. No additional information was collected passively about participants’ computers, e.g., IP address, cookies etc.

Preparatory data analysis

Given that the survey data is the data source for ABM development, we opted to summarize the statistics of the empirical data here to avoid duplication and confusion from those of simulation experiments in Section 3. In short, a complete data set of 200 professional singers (N = 82) and actors (N = 118) and 203 controls were included in the analysis (both groups: ages 21–65; female 65%, male 32%, other 3%). An additional 32 participants were not considered for analyses (vocal performer group: n = 22; control group: n = 10), as their data were considered to be inadequate after data cleaning due to invalid or missing data. An additional 14 participants dropped out of the study (vocal performer group: n = 3; control group: n = 11). Full details of participant demographics, statistical tests, and results of the empirical survey data can be found in Supplementary Tables 1–3 and 5–10, respectively. Demographic and vocal health information for each group has been specified, and the vocal performer group has been further disambiguated by singers and actors in Supplementary Table 4.

Statistical analyses were carried out in R (version 4.2.1)84. All assumptions were tested and met for the test statistics, including independent sample t-tests (t), Spearman’s rank-order correlations (ρ), and Pearson’s product-moment correlation (r). With respect to vocal stigma experience, performers reported 14% more stigma than controls (t(401) = 8.87, p = 0.025) overall. Among professionals, singers reported 15% more stigma than actors (t(198) = −1.67, p = 0.025). Irrespective of groups, stigma was negatively associated with (1) age (Performers: r = −0.27, p < 0.001; Controls: r = −0.17, p = 0.018), (2) recency of a voice disorder (Performers: ρ = 0.15, p = 0.033; Controls, ρ = 0.14, p = 0.047), and (3) frequency of voice disorder (Performers: ρ = 0.46, p = 0.005; Controls: ρ = 0.26, p = 0.031). One-way ANOVA analyses were also carried out to evaluate the relationship between stigma and gender identity, and no significant results were obtained in either study group (Performers: F(2202) = 1.91, p = 0.151; Controls: F(2199) = 1.70, p = 0.168).

With respect to the association of stigma experience and individual IMB profiles, stigma correlated negatively with motivation (Performers: r = −0.49; Controls: r = −0.59, p < 0.001) and behavioral skills (Performers: r = −0.28; Controls: r = −0.46, p < 0.001) in both participant groups. Stigma was not significantly associated with information (Performers: r = −0.09, p = 0.205; Controls: r = −0.09, p = 0.200), meaning there was not a definitive trend between stigma and an individual’s knowledge/beliefs regarding voice disorder or vocal health.

Broadly speaking, vocal stigma is found present among professional singers and actors in Canada. The level of Motivation and Behavioral Skills of an individual were negatively associated with vocal stigma. The negative association between age and experiences of stigma may indicate that early-career vocal performers are more vulnerable to this stigma. The positive association between a history of vocal illness and experience of vocal stigma may indicate that vocal stigma is not commonly recognized by individuals without direct experience with a voice condition.

Computational study of simulating social interactions and vocal stigma

Vocal stigma agent-based models: a conceptual framework

In this vocal stigma agent-based model (VS-ABM)85, each agent represents an avatar of a vocal performer (VP) or a non-vocal performer (non-VP), who functions as a social actor and interacts with their peers to share information and their motivations for help-seeking related to voice health. Depending on an agent’s geolocation, they have access to a small or a large peer network in the VS-ABM. When two agents interact, they will exchange information and motivations related to vocal health.

An agent’s vocal health (history and frequency of disordered voice), stigma experience (self- and social- stigma), and IMB are connected via two feedback loops (social and personal), which in turn affects an agent’s tendency to seek help (Fig. 3). The social loop simulates the interrelationship between social-stigma and IMB. Also, an agent’s motivation is linked to its own frequency of voice disorder. For instance, if an individual has frequent relapses of voice disorders, they will likely have less motivation to seek help from social partners and professionals. In contrast, the personal loop simulates the interrelationship between self-stigma and IMB. Also, an agent’s information related to vocal health is contingent on its history of voice disorder. For instance, if an individual has prior experience with a voice disorder, they will likely have more information about the nature of it and may have reduced their self-stigma as a result.

Fig. 3. The framework of vocal stigma agent-based models (VS-ABM).

An agent’s vocal health, vocal stigma, information, motivation, and behavioral skills (IMB) are presumably interrelated and modulated via the social and personal feedback loops, which collectively affect an agent’s tendency to seek help.

VS-ABM design: world

The VS-ABM is developed with NetLogo version 6.3.0, a free and open-source, cross-platform, agent-based modeling framework86. In our implementation, the VS-ABM world represents a small urban community, which is divided into a total of 1089 patches (33 × 33), with a densely populated urban-center and a sparser rural-perimeter. This geographical specification of the VS-ABM is based on the following considerations. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Variables of world and agents in the vocal stigma agent-based model

| ABM variables | Real-world components | Estimated range/values |

|---|---|---|

| World Variables | ||

| Ratio of rural to non-rural agents | 5% | |

| Rural area | 55 patches | |

| Max number of links | min = 0, max = number of agents | |

| Number of interactions with the max number of links | Time when max number of links is established | |

| Agent variables | ||

| Gender | male, female | |

| Age | Mean = 43.68 (SD = 12.56) | |

| Education level | High school diploma (9%), Apprenticeship/trade (5%), College/CEGEP (16.5%), Bachelors (46%), Graduate (23.5%) None (0%) | |

| Vocal training | None (4%), less than 1 year (11%), less than or equal to 3 years (21.5%), less than or equal to 5 years (13%), more than 5 years (50.5%) | |

| Proportion of income dependent on using their voice professionally | None or almost none (8%), less than half (24.5%), about half (17.5%), greater than half (18.5%), all (29%), not answered (2.5%) | |

| Information | 0–20 | |

| Motivation | 0–20 | |

| Behavior skills | 0–20 | |

| Frequency of voice disorder | Never (51%), Every few years (33.5%), Yearly (9%), Quarterly (4.5%), Monthly (0.5%), All the Time (1.5%) | |

| Previous history of voice disorder | Never (50%), currently have disorder (6%), within the past month (4.5%), within the past year (9.5%), more than a year ago (30%) | |

First, the VS-ABM world size was set to approximate the lower boundary of a sparse geographic network. This is because simulated social networks of all sizes need to fit within the ABM world without being too densely populated. If the ABM world is too big, agents will be too far away from each other for social interactions. Second, the VS-ABM world is set as box-bound. That is, agents on the left or the top edges do not interact with the agents on the right or the bottom edges and vice versa. That way, agents in the rural region at the outer border are constrained to have fewer possible connections compared to those in the urban center of the simulation space. Note that about 5% of survey respondents were from rural areas in Canada (Supplementary Table 1). To approximate this real-world geographical distribution in the VS-ABM, we set the smallest network (50 agents) to have around 5% of patches occupied by agents, whilst the same proportion of rural agents approaches 100% of occupied patches for the largest social network (400 agents). This geographical specification allows the proportion of rural agents to remain at 5% in both geographically sparse networks (with 50 agents) and socially sparse networks (with 400 agents).

VS-ABM design: individual agent attributes

Each agent has a set of attributes in terms of personal background (gender, age, education level, vocal training, etc.) as well as experience related to voice health (e.g., information, motivation, behavior skills, self-stigma, social-stigma, history of voice disorder). (Table 1) All attributes are randomly assigned to each agent based on the normal distribution of the values from the demographic data in the empirical study (Supplementary Tables 1–4).

VS-ABM: agent-agent social interactions

Within the ABM world, agents are free to interact and exchange information with nearby peers. These agents cannot move their location and are surrounded by neighboring peers whom they are free to interact with. Agents also randomly select their next agent for each interaction. The potential peers are limited to a circular region around each agent with a radius of three patches. In other words, agents’ interaction space is 2.5% of the possible geographic space. We also assume that an agent with high initial social-stigma may be reluctant to interact with their peers. As such, in the VS-ABM, if either agent has high social-stigma (over 7.5), the chance of their peer interaction is set as 75%.

After each interaction, the IMB and vocal stigma of an agent will change incrementally. The exact incrementation is formulated based on the linear regression analyses of the help-seeking and stigma relationship in the survey study (Supplementary Table 9). For example, within the social loop, social-stigma is associated with information. After each peer interaction, an agent’s information will slightly change by a value that is randomly sampled from a normal distribution centered around the mean, as obtained from the corresponding regression analysis (Information-Social-Stigma: 0.066). The change in an agent’s information can also cascade to changes in behavior skills and motivation. The formulation is the same but with different center means derived from the corresponding regression terms (Information-behavioral skills: 0.232; Motivation-social-stigma: 0.316). The formulation of all agent-rules is detailed in Supplementary Table 12, and the pseudocode for the VS-ABM is presented in Supplementary Code.

VS-ABM simulation experiments

This VS-ABM is designed to simulate social interaction and transfer of information/motivation among peers as functions of network size and initial social-stigma. Simulation experiments were set up to answer three research questions respectively (Supplementary Table 11 for the ABM world initialization and Supplementary Table 13 for the initialization procedure of simulation experiments).

Research Question #1: Does vocal stigma decrease when there are larger social groups?

To investigate the relation between network size and total stigma, we ran 500 simulations for each network size with 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300, 350, and 400 agents up to 500,000 social interactions. We hypothesize that an agent’s total stigma will reduce with increasing peer networks. With more peers available to interact with, agents have a greater variety of peers to gain experiences and information from. More peers, more information, and more interactions should make agents more likely to increase their total IMB and lower their vocal stigma. Peers with extreme values for IMB and stigma may polarize their limited network more severely than with a larger peer group.

Research Question #2: Does vocal stigma decrease when peers are more willing to socially interact?

To evaluate social willingness for agent-agent interactions, we ran an additional 800 simulations initialized for five agent populations with distinctive initial social-stigma profiles, since empirical data showed differences between non-VP and VP groups (Supplementary Tables 5–8). Each group is assigned with an initial social-stigma value obtained from the empirical data (Supplementary Table 10). For instance, the initial social-stigma value for the “General Population” is 5.4, which is derived by averaging social-stigma scores from non-VPs and VPs. While the VS-ABM does not explicitly model medical intervention, we assume that social interventions based on peer interactions will act similarly on social-stigma. Related hypotheses are: (1) social-stigma will decrease over time for agents who are more willing to interact; and (2) agents with high social-stigma will be less likely to transfer information/motivation to peers. A total of 4000 simulations were run for the following five agent populations (see Supplementary Table 10 for quantitative descriptions of each population): (1) General Population of both non-VPs and VPs with average social-stigma (5.40) and average risk and incentive; (2) non-VP group with low social-stigma (4.86), low risk of voice disorder and little incentive to seek professional help; (3) VP group with higher social-stigma (5.95), higher risk of voice disorder and more incentive to seek professional help; (4) VP group with a history of voice disorder, high social-stigma (6.42) that has been mitigated by some social intervention; as well as (5) VP group with a history of voice disorder, very high social-stigma (7.39) elevated in part by no intervention for the voice disorder.

Research Question #3: How does social network structure impact IMB and stigma?

A comprehensive network-based analysis was employed to evaluate the impact of social network structure on the flow of information and motivation among agents for all 4000 simulations run. A NetLogo network extension procedure (nw) was used to quantify two standard network measures, namely, the degree of a node and local clustering coefficient87. The degree of the node (count links) is used to measure the number of peers that an agent is connected to in the network. The local clustering coefficient (nw:clustering-coefficient) is used to measure how densely connected an agent’s neighbors are and how much they tend to group together in a network by averaging all individual nodes. While this analysis could be performed on both the network size and social-stigma manipulations, we chose to focus on network size for two reasons. First, social structure in these networks should be directly correlated to the number of agents in the simulation, since the simulation space does not change nor does the radius which agents survey for neighbors. Second, in order to generalize across all simulations, we use an outcome measure agnostic to initialized values of social-stigma, change in total stigma, which also allows us to compare directly with change in IMB so they are on similar measurement scales. We thus test which network structure, degree (number of peer connections) or clustering coefficient (peer connectedness), has the largest impact on change over time.

Statistics and reproducibility

VS-ABM is developed with NetLogo version 6.3.086. Network measures were calculated in NetLogo via the new extension87. Each simulation was run for 500,000 interactions; 100 simulations were run for each set of initialization parameters. Further, all simulation data are available online88, but are replicable as a random seed was initialized for all simulations, and data can be regenerated directly from NetLogo code. All statistical analyses for both empirical data and simulation data were imported into R (version 4.2.1)84. Data were summarized via tidyverse (version 1.3.2)89, and plotted using a combination of the ggplot2 (version 3.4.2)90 and ggpubr (version 0.6.0)91 packages. Network diagrams were created through gephi (version 0.9)92.

All tests of independence between participants were 2-tailed chi-squared tests. Statistical tests between participant groups were two-tailed t-tests, or Mann–Whitney U-tests in the case of non-normal distributions.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Results

Overall relation between total stigma and social network size

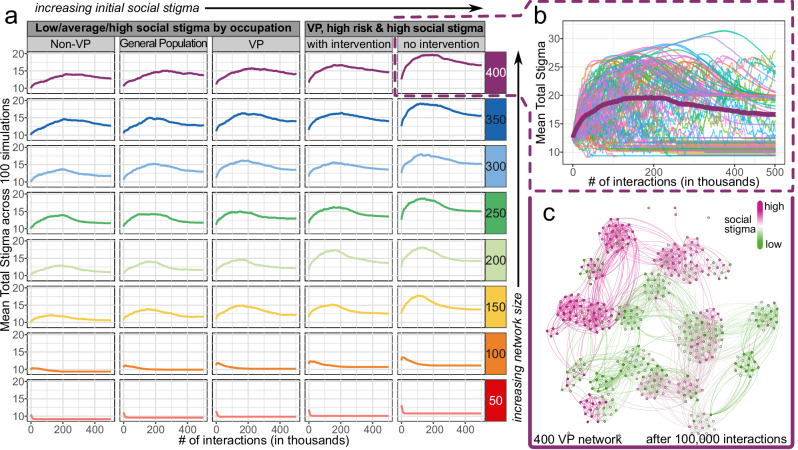

Our original hypothesis for Research Question #1 was that vocal stigma would decrease with larger social networks. Unexpectedly, this hypothesis was not supported by our ABM simulation results in looking at changes in total stigma relative to the number of interactions with network sizes (50–400 agents) and initial social-stigma profiles (low vs average vs high) for each VP, non-VP and general populations (Fig. 4a, social-stigma profile values outlined in Supplementary Table 13).

Fig. 4. Total stigma experience as functions of network size and number of interactions in agents with low, average, and high initial social-stigma.

a Aggregated trends of mean total stigma scores. Each trend aggregated from 100 simulations initialized with social-stigma and network size. b Varying outcomes of mean total stigma score from individual simulations for VP agents with a high risk of voice disorders, high initial social-stigma, and no intervention within the 400-agent network size. The aggregated trend, the same as the VP group in Fig. 4a, for all 100 simulations is shown in bold. c A representative snapshot of simulated social networks with 400-VP agents near the maximal total stigma after 100,000 interactions in the 400-VP network. An agent’s social-stigma is color-coded from low (Green) to high (Red).

First, on the VP networks, agents in the two smallest network sizes (50 and 100) had their total stigma stabilized as early as 25,000 social interactions. Their final total stigma values were also lower than initial values, regardless of initial social-stigma. In contrast, when the networks became sizable (>150 agents), the trajectories of total stigma started to follow a log-normal distribution pattern. That is, agents’ total stigma quickly increased to a peak and then slowly leveled off but did not always return to initial values. Interestingly, VP agents with high initial social-stigma took 25% fewer social interactions (50,000 to 100,000) to reach the peak of total stigma, compared to those with low initial social-stigma (the general and non-VP groups). This initial observation suggests that total stigma likely worsens over time with social interactions in larger network groups, particularly for individuals prone to higher social-stigma, such as VP at high risk for voice disorder and a tendency to not seek intervention.

To further examine this paradox, we proceeded to examine individual-specific variations in the evolution of total stigma in the largest network (400 agents) from the VP group with initial high stigma up to 500,000 interactions (Fig. 4b). Three distinct patterns emerged from this case simulation. (1) First, one set of simulations quickly leveled off towards a total stigma value lower than the initial value, which is denoted as the decreasing cohort. (2) Another set of simulations, which is denoted as the increasing cohort, increased rapidly towards a maximum between 50,000 and 200,000 interactions and then slowly leveled off to a total stigma value larger than the initial value. (3) Lastly, the chaotic cohort is a set of agent simulations that appeared to fluctuate randomly and did not appear to stabilize even after 500,000 social interactions.

Except for the chaotic cohort, most agents’ total stigma appeared to approach a maximum of around 100,000 social interactions with large social networks. To understand one such maxima, we further visualized an established social network from the increasing cohort in 400-VP agents after 100,000 social interactions (Fig. 4c). Multiple clusters or social groups with similar social-stigma values were formed within the global network, suggesting a homogenization with these highly interconnected social groups. Also, these clusters were not isolated but rather fairly connected to neighboring groups. In other words, peers were connecting with the whole set of the neighboring group, rather than simply bottlenecking through a few nearby peers.

In particular, a few social groups appeared to have a heterogeneous mix of agents with initial low and initial high social-stigma profiles (Fig. 4c: networks with mixed green and red color), confirming that agents could interact with opposite social-stigma values. Especially in this increasing cohort, the emergence of mixed social groups in the global network coincides with the stabilization of total stigma around the critical point of 100,000 social interactions. We speculated that, at the beginning of interactions, agents would establish social groups with peers around them, becoming more like their neighbors. Then, when social groups became homogenous, the total stigma would approach its peak. Eventually, when social groups with polarized views interacted, a mix of agents with low and high social-stigma emerged and, paradoxically, stabilized the population’s social-stigma.

To answer Research Question #1, our simulation results indicated that, on average, vocal stigma increases with larger social groups. However, there are non-trivial trends where total stigma diminishes as social groups become less polarized. In addition, our results suggested that interactions between groups are not bottlenecked with a small set of agents but distributed among the entire social group. The clusters can exchange information/motivation with multiple members of neighboring groups, which may ultimately result in less polarized neighboring groups.

Social network size in relation to each IMB and vocal stigma components

For Research Question #2, the original hypothesis was that social-stigma would decrease when agents were more willing to socially interact, i.e., lower social-stigma and higher IMB. This hypothesis was partially supported by our ABM simulation results in comparing the probability distributions of final IMB and final total stigma scores between the smallest and largest social networks (50 vs 400 agents) (Fig. 5a, b).

Fig. 5. Probability distribution of total IMB and total stigma experience.

A total of 500,000 social interactions were simulated for VP, non-VP, and general populations with low, average, or high initial social-stigma. a Total IMB and its components (information, motivation, and behavioral skills) at 50 and 400 network sizes. b Total stigma and its components (self-stigma and social-stigma) at 50 and 400 network sizes. c Average change in total IMB (diamonds) and total stigma (circles) from their initial values. Each row of subplots represents a specific magnitude of change, i.e., from less than 1 SD (σ) to more than 2 SD increase (inc.) or decrease (dec.), in total IMB and total stigma. % = percentage of simulations with corresponding changes in total stigma across all network sizes. d Ratio of simulations with total stigma changes more than 1 SD (Panel c row 1 + 2) relative to those with little or no changes (Panel c row 3).

Following a total of 500,000 social interactions, a clear bimodal distribution of total IMB score was noted in large, but not in small networks across all three agent populations (Fig. 5a). Of the total IMB score, the first mode (local maximum) appeared around 60 and 75, whereas the second mode appeared around 110 in the probability density function. Each IMB element (information, motivation, and behavioral skills) also appeared to be highly coupled. That is, an agent population, regardless of its initial social-stigma, can be sub-grouped into either with low IMB and high IMB. Such sub-group distinction is much more pronounced in large social networks than in small ones.

For the total stigma, a bimodal distribution also appeared in large but not small social networks across all three agent populations (Fig. 5b). Of the total stigma score, the first mode was centered around 10, whereas the second mode was around 20 within the data. Each total stigma element (social- and self-stigma) also displayed two distinctive peaks, but their distance was more separated in social-stigma score. Additionally, comparing high-risk VP groups, those with social intervention had overall lower social-stigma, whereas the maximal mode for the no-intervention group showed higher social-stigma. Our results indicated that social-stigma experience has more weight than self-stigma in the total stigma experience.

Further analysis was performed to evaluate the magnitude of changes in total IMB and total stigma by aggregating VP, non-VP, and general populations before and after the 500,000 interactions (Fig. 5c, d). For total IMB, about 35 and 63% of agents showed increases or no changes in their scores in smaller networks (50 and 100 agents) at the end of simulations. With larger network sizes (>150 agents), about 36% of agents showed considerable increases in their total IMB scores with more than two standard deviations (SD, σ), i.e., between 30 and 40 points increase from initial values. At the same time, about 39% and 21% of agents showed a reduction in their IMB scores by more than 1 and 2 SD, respectively, in these larger networks (Fig. 5c). For total stigma, all agents in smaller networks had negligible changes of their scores, whilst 25% of them had total stigma increased by more than six points when they were in larger networks. For those with high risk and high social-stigma, VP agents were 1.5 times more likely to experience more total stigma if they had no intervention, compared to those with social intervention, when they are in the largest social network (Fig. 5d).

All in all, the aforesaid simulation results confirmed that higher total IMB was associated with lower total stigma for small networks. Interestingly, IMB outcomes vary across network sizes. Despite minimal change to total stigma, IMB tended to decrease more for larger social networks, while IMB for smaller networks tended to increase. The bimodal distribution noted in large social networks (i.e., 400) may be attributed to the increased likelihood that extreme values of social-stigma arise in the population. Also, within a large social network, their social groups tend to be more polarized with group size, as noted in Fig. 4c, leading to a wider separation between the two modes of the bimodal distributions.

To address Research Question #2, our results supported the hypothesis in cases of small networks, i.e., lower social-stigma leads to an overall decrease in total stigma. Larger networks are far more likely to have increased total stigma. For high-risk VPs, social interventions might help mitigate high social-stigma and eventually a reduction in total stigma over time.

Network structure in relation to total IMB and total stigma

To understand the connections among agents in the social network, the degree of node and clustering coefficient were computed in relation to the changes in total IMB and total stigma when the social network was established (i.e., after 100,000 social interactions) in all 4000 simulations.

First, the degree of a node represents the number of social links that an agent has in a social network. (Fig. 6a) The average number of links ranged from 2.5 in the smallest social network (50 agents) to 13.5 in the largest social network (400 agents). This positive linear relationship is expected because each agent has more peers to interact within their vicinity in larger social networks. For instance, the relative patch coverage increases from 5% in the 50-agent network to nearly 36% in the 400-agent network.

Fig. 6. Network structure analysis of network size effects on IMB and vocal stigma.

a Distribution of an average number of peer links (degree of nodes) by network size. b Distribution of average local clustering coefficient by network size. c Total IMB values decrease as a function of an average number of peer links, which is highly correlated with network size. A clear bifurcation appears around 4.5 peer links. d Total stigma values increase as a function of an average number of peer links. No bifurcation appears. However, distributions show a larger range of changing stigma values for more peer links. Note all panels show all 4000 simulations; panels (a, b) plot distribution of all 500 for each network size, while panels (c, d) plot all each simulation results individually for a total n = 4000.

Second, the clustering coefficient represents how close-knit an agent’s social group (i.e., cluster) is interconnected in a social network. The clustering coefficient is measured on a scale of 0 to 1. A lower cluster coefficient is when peers are only connected through the agent, whereas a higher cluster coefficient is when agents’ peers connected independently and create denser and tighter connections.

Interestingly, the average clustering coefficient for the network does not show a linear trend with network size (Fig. 6b). A wide spread of clustering coefficients was observed in small social networks, whereas the probability distribution approximated to a normal distribution towards a larger social network. The cluster coefficient is also higher in larger networks (400 agents; mean (SD) = 0.61 (0.009)) than that of smaller networks (50 agents; mean (SD) = 0.31 (0.086)). In small networks, agents were sparsely randomized in the simulation space, which geographically favored agents being connected with their neighboring peers only but not reaching out to other social groups that are further away.

Finally, we analyzed how the number of peer links (i.e., social partners) affects an agent’s total IMB and total stigma scores when the social network is stabilized, i.e., all links are maximally connected. For total IMB, more peer links might relate to a gradual decrease in IMB. (Fig. 6c) Upon the stabilization of social networks, the IMB increases by 7.6 points in the smallest 50-agent network (1.5 social links); whereas it decreases by 10.6 points in the largest 400-agent network (12.5 social links). For total stigma, more peer links might contribute to a slight increase in total stigma (Fig. 6d). Upon network stabilization, the total stigma decreases by 1.2 points in the 50-agent network yet increases by 3.5 points in the 400-agent network.

Discussion

By using a prospective survey and network simulations, we were able to: (1) characterize population behavior related to vocal stigma in professional vocal performers; (2) identify which IMB and stigma components contribute most to population outcomes; and (3) analyze network structure and social groups to understand the impact of social interactions on population outcomes. Our VS-ABM allows each IMB and stigma component to be examined independently while simultaneously modeling how each element influences others. These components can vary for each individual and change as individuals interact with peers with distinct IMB and health profiles.

Three population behaviors, namely decreasing, increasing, and chaotic cohorts, were identified across all network sizes. The decreasing cohort had characteristics that resembled the small network trends, such that total stigma decreases and quickly stabilizes at a value less than the original population stigma. The increasing cohort had characteristics that resembled the large network trends, where total stigma increases to a maximum and then levels off towards a value larger than the initial stigma value. Such stigma maxima are seen when the social network of the population is fully established, and social groups are largely homogenous. When polarized homogenous groups start to interact and exert more influence on each other, greater heterogeneity of the groups emerges at a population level. Lastly, the chaotic set is referred to an oscillatory behavior when total stigma does not stabilize. Such complex patterns of vocal stigma are not programmed (i.e., hard-coded) in VF-ABM but rather emerge de novo (i.e., emergency) from dynamical systems. Our simulation outcomes may also be in line with the notion of stigma mutation.93 For instance, stigma associated with COVID-19 has a social-historical context and changes over time in response to the local and global environment. In our case, agents’ social-personal backgrounds (e.g., occupation, medical history, and initial social-stigma) modulate the evolution of their total stigma in a network environment.

We further investigated which specific IMB and stigma components drove changes in population outcomes in relation to network size. Overall, information and behavioral skills tend to be coupled more strongly with motivation being inversely related, i.e., higher information and behavioral skills relative to a lower motivation. Social-stigma has more impact than self-stigma on total stigma. The variance of IMB changes is considerably large across all network sizes, ranging from −6 to +5 SD changes on average. In contrast, the variance of total stigma changes remains quite consistent—around 75–85% of all simulations show less than 1 SD change on average. Moreover, in larger network sizes, social interactions led to three distinctive patterns of social-stigma, namely, (1) small decreases in low/ average risk groups, (2) small increases in high-risk groups; or (3) large increases regardless of risk group. In particular, larger networks with higher-risk groups of voice disorders have considerably higher odds of increasing the total stigma than those of lower-risk groups. Among these higher-risk individuals, those without medical interventions have higher odds (4:4) to increase total stigma after social interaction than those who received treatment (3:4). That is, for large networks (i.e., 400 agents), about 51% of VP with no intervention are likely to increase their stigma after interacting with their peers; this likelihood drops to 41% if they receive intervention.

Another key observation is that IMB and stigma do not always have a directional relationship. For instance, if we looked at simulated populations whose total stigma changed more than 1 SD with social interactions, their IMB scores could increase by 20 points at most. For those with changes of more than 2 SD in total stigma, IMB decreased considerably by 30 points—in this case, vocal stigma might get worse despite informational and social intervention. Similar notions were also confirmed in reducing public stigma of mental illness, in which stigma is difficult to eliminate, especially if it is deep rooted in social relationships94.

Two standard network measures were analyzed to evaluate how connected VPs were (i.e., degree of node) and how close their social groups were linked (i.e., clustering coefficient). As the network size increased, a VP agent had more peers to interact and connect with in their vicinity. That is, for larger networks, peers had consistently larger social groups. However, as we simulated hundreds of thousands of social interactions, all agents were able to eventually interact and connect with all their potential peers, and all social groups were maximally interconnected or clustered. As social group networks stabilize and become maximally connected, a gradual increase in total stigma and decrease in IMB was evident in larger but not smaller social groups. These analytics also provided part of the evidence to answer Research Question #1, i.e., larger networks stabilized towards more polarized social groups. This observation aligns with similar social network findings of polarization of political groups and how negativity spreads through larger social networks faster than positivity95,96.

As far as we are aware, this study investigates vocal stigma, for the very first time, in the context of social computing with expected technical challenges. First, our vocal stigma-specific questionnaire was deployed to Canadians only. Additional data from other countries can be collected to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of VS-ABM or if additional organization or institutional factors (e.g., reimbursement system) will be needed to be included in future simulations.

Second, personality traits have been linked to the risk of voice disorders97–101, which in turn may affect a person’s health-seeking behavior102,103. Compared to those of vocally healthy, singers with vocal nodules were found to be more impulsive and socially dominant104 Meanwhile, individuals with low levels of neuroticism would likely engage in proactive health behavior, e.g., seeking health information, social support etc102 In the current study, individual’s personality was not factored in the VS-ABM. One key barrier was that empirical association data between vocal athletes’ personality and their health-seeking experience did not exist in the literature for our model building and verification. Future work could include additional survey questions to profile extroversion-introversion and neuroticism-stability together with vocal stigma experience. The information will help decipher how intrapersonal factors (e.g., personality traits) could contribute to individual differences in the stigmatization process and health-seeking behavior.

Third, our initial model results suggest the presence of a chaotic set in the population behavior. A more rigorous analysis of systems dynamics can be performed to evaluate when the system is in equilibrium or cycling in parameter space, which is out of the scope of this paper.

Fourth, causal models can be considered to further examine the direction and causal relationships between components of IMB and stigma, since we primarily focused on correlations between these measures. Lastly, for the network analysis, we took a measured approach to establish a general trend for the population dynamics. However, more complex network measures such as information transmission and node similarity can be employed to characterize the details of stigma spread through the social network, instead of focusing on population averages in IMB and stigma.

In conclusion, stigma is a serious, intractable barrier that prevents vocal performers from seeking vocal healthcare. This study integrated empirical survey and network simulation approaches to quantify the relationship between social interaction and vocal stigma. VS-ABM computer models were built to numerically simulate peer interactions and track person-level changes in the IMB framework. Our results highlight that an individual’s social network plays an important role in the experience of vocal stigma. Especially for vocal performers, social interventions, e.g., close peer support, may help reduce high vocal stigma over time.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (#430-2020-00108), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (388583), the Digital Research Alliance of Canada, and the Canada Research Chair research stipend (N.Y.K.L.-J.). The presented content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the above funding agencies. This project would not be possible without the help of our collaborators at the National Association of Teachers of Singing and the Alliance of Canadian Cinema, Television, and Radio Artists, including the expert feedback provided by Allen Henderson, Simon Peacock, and Theresa Tova. The authors would also like to thank Maia Masuda for her feedback as an expert voice clinician and all individuals who participated in the survey study.

Author contributions

A.R.G.: Conceptualization (lead), investigation (lead), formal analysis (equal), writing—original draft (lead). C.J.: Formal analysis (equal), data curation (lead), writing—original draft (supporting). L.M.: Investigation (supporting), Writing—review and editing (supporting). L.B.: Investigation (supporting), writing —review and editing (supporting). T.T.: Investigation (supporting), writing—review and editing (supporting). A.H.: Investigation (supporting), writing—review and editing (supporting). M.D.P.: Supervision (supporting), conceptualization (supporting), writing—review and editing (supporting). N.Y.K.L.-J.: Supervision (lead), conceptualization (supporting), funding acquisition (lead), resources (lead), writing—review and editing (lead).

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Medicine thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Data availability

All survey and simulation datasets in this study can be accessed via 10.6084/m9.figshare.27244824105 and 10.6084/m9.figshare.2540014088, respectively. Raw simulation data for all timepoints are shared, combined across network size, with all supporting information for the network. Requests regarding the data can be directed to the corresponding author at nicole.li@mcgill.ca upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The computer code used in this study can be accessed via 10.6084/m9.figshare.2538833585. All simulations were run using NetLogo version 6.3.0. All statistical analyses for both empirical data and simulation data were imported into R (version 4.2.1). Data were summarized via tidyverse (version 1.3.2), and plotted using a combination of the ggplot2 (version 3.4.2) and ggpubr (version 0.6.0) packages.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s43856-024-00651-3.

References

- 1.Lei, Z. et al. Wearable neck surface accelerometers for occupational vocal health monitoring: instrument and analysis validation study. JMIR Form. Res.6, e39789 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pestana, P. M., Vaz-Freitas, S. & Manso, M. C. Prevalence of voice disorders in singers: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Voice31, 722–727 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerner, M. Z., Paskhover, B., Acton, L. & Young, N. Voice disorders in actors. J. Voice27, 705–708 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cutiva, L. C. C., Vogel, I. & Burdorf, A. Voice disorders in teachers and their associations with work-related factors: a systematic review. J. Commun. Disord.46, 143–155 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martins, R. H. et al. Voice disorders: etiology and diagnosis. J. Voice30, 761 e761–761 e769 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen, S. M., Kim, J., Roy, N., Asche, C. & Courey, M. Direct health care costs of laryngeal diseases and disorders. Laryngoscope122, 1582–1588 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen, S. M., Kim, J., Roy, N., Asche, C. & Courey, M. The impact of laryngeal disorders on work-related dysfunction. Laryngoscope122, 1589–1594 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Titze, I. R., Lemke, J. & Montequin, D. Populations in the U.S. workforce who rely on voice as a primary tool of trade: a preliminary report. J. Voice11, 254–259 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verdolini, K. & Ramig, L. O. Review: occupational risks for voice problems. Logop. Phoniatr. Vocol. 26, 37–46 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vilkman, E. Voice problems at work: a challenge for occupational safety and health arrangement. Folia Phoniatr. Logop.52, 120–125 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones, K. et al. Prevalence and risk factors for voice problems among telemarketers. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head. Neck Surg.128, 571–577 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fellman, D. & Simberg, S. Prevalence and risk factors for voice problems among soccer coaches. J. Voice31, 121.e129–121.e115 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canada Council for the Arts. A Statistical Profile of Artists in Canada in 2016. https://canadacouncil.ca/research/research-library/2019/03/a-statistical-profile-of-artists-in-canada-in-2016 (2019).

- 14.Satav, B. & Relekar, S. Identification of symptoms of the vocal fatigue in stage actors. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Dev.4, 38–41 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boltezar, L. & Sereg Bahar, M. Voice disorders in occupations with vocal load in Slovenia. Zdr. Varst.53, 304–310 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Phelan, J. C. & Link, B. G. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am. J. Public Health103, 813–821 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scott, N., Crane, M., Lafontaine, M., Seale, H. & Currow, D. Stigma as a barrier to diagnosis of lung cancer: patient and general practitioner perspectives. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev.16, 618–622 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clement, S. et al. What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol. Med.45, 11–27 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rueda, S. et al. Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open6, e011453 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cellucci, T., Krogh, J. & Vik, P. Help seeking for alcohol problems in a college population. J. Gen. Psychol.133, 421–433 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carter-Harris, L., Hermann, C. P., Schreiber, J., Weaver, M. T. & Rawl, S. M. Lung cancer stigma predicts timing of medical help-seeking behavior. Oncol. Nurs. Forum41, E203 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Murphy Estes, C., Flynn, A., Clark, C. M., Born, H. & Sulica, L. Understanding performers’ perspectives on access to care and support for voice injuries: a survey study. J. Voice S0892-1997(24)00137-1 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Bradshaw, N. & Coopeer, A. L. Medical privacy and the professional singer: injury stigma, disclosure, and professional ramifications on broadway. J. Sing.74, 513–520 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilman, M., Merati, A. L., Klein, A. M., Hapner, E. R. & Johns, M. M. Performer’s attitudes toward seeking health care for voice issues: understanding the barriers. J. Voice23, 225–228 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stangl, A. L. et al. The health stigma and discrimination framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med.17, 31 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Link, B. G. & Phelan, J. C. Conceptualizing stigma. Annu. Rev. Sociol.27, 363–385 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosen, D. C., Sataloff, J. B. & Sataloff, R. T. Psychology of Voice Disorders, 2nd edn (Plural Publishing, 2021).

- 28.Norman, P. & Conner, P. Predicting health behaviour: a social cognition approach. Predicting Health Behav.1, 17–18 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fisher, W. A., Fisher, J. D. & Harman, J. The Information-Motivation-Behavioral Skills Model: a General Social Psychological Approach to Understanding and Promoting Health Behavior. In Social Psychological Foundations of Health and Illness (eds Suls, J. & Wallston, K. A.) Ch. 4 (Blackwell Publishing, 2003).

- 30.DeBate, R. D., Gatto, A. & Rafal, G. The effects of stigma on determinants of mental health help-seeking behaviors among male college students: an application of the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Am. J. Mens. Health12, 1286–1296 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thornicroft, G. et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet387, 1123–1132 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgan, A. J., Reavley, N. J., Ross, A., Too, L. S. & Jorm, A. F. Interventions to reduce stigma towards people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Psychiatr. Res.103, 120–133 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown, L., Macintyre, K. & Trujillo, L. Interventions to reduce HIV/AIDS stigma: what have we learned? AIDS Educ. Prev.15, 49–69 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adu, J., Oudshoorn, A., Anderson, K., Marshall, C. A. & Stuart, H. Social contact: next steps in an effective strategy to mitigate the stigma of mental illness. Issues Ment. Health Nurs.43, 485–488 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang, J. & Centola, D. Social networks and health: new developments in diffusion, online and offline. Annu. Rev. Sociol.45, 91–109 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sikder, O., Smith, R. E., Vivo, P. & Livan, G. A minimalistic model of bias, polarization and misinformation in social networks. Sci. Rep.10, 5493 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tokita, C. K., Guess, A. M. & Tarnita, C. E. Polarized information ecosystems can reorganize social networks via information cascades. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA118, e2102147118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Gradoń, K. T., Hołyst, J. A., Moy, W. R., Sienkiewicz, J. & Suchecki, K. Countering misinformation: a multidisciplinary approach. Big Data Soc.10.1177/20539517211013848 (2021).

- 39.Mooney, S. J. & El-Sayed, A. M. Stigma and the etiology of depression among the obese: An agent-based exploration. Soc. Sci. Med.148, 1–7 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Drapalski, A. L. et al. A model of internalized stigma and its effects on people with mental illness. Psychiatr. Serv.64, 264–269 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garney, W. R. et al. Evaluating community-driven cardiovascular health policy changes in the United States using agent-based modeling. J. Public Health Policy43, 40–53 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marshall, B. D. et al. A complex systems approach to evaluate HIV prevention in metropolitan areas: preliminary implications for combination intervention strategies. PLoS ONE7, e44833 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Giabbanelli, P. J., Voinov, A. A., Castellani, B. & Törnberg, P. Ideal, best, and emerging practices in creating artificial societies. In Proc. Annual Simulation Symposium. 2 (Society for Computer Simulation International) (ACM/IEEE, 2019).

- 44.Smith, E. R. & Conrey, F. R. Agent-based modeling: a new approach for theory building in social psychology. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev.11, 87–104 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Elliott, E. & Kiel, L. D. Agent-based modeling in the social and behavioral sciences. Nonlinear Dyn. Psychol. Life Sci.8, 121–130 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen, S.-H. & Yeh, C.-H. Evolving traders and the business school with genetic programming: a new architecture of the agent-based artificial stock market. J. Econ. Dyn. Control25, 363–393 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 47.LeBaron, B. Empirical regularities from interacting long- and short-memory investors in an agent-based stock market. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput.5, 442–455 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Llacay, B. & Peffer, G. Using realistic trading strategies in an agent-based stock market model. Comput. Math. Organ. Theory24, 308–350 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen, D.-N., Jeng, B., Lee, W.-P. & Chuang, C.-H. An agent-based model for consumer-to-business electronic commerce. Expert Syst. Appl.34, 469–481 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Garifullin, M., Borshchev, A. & Popkov, T. Using AnyLogic and agent-based approach to model consumer market. In Proc. 6th EUROSIM Congress on Modelling and Simulation 1–5 (ARGESIM, 2007).

- 51.North, M. J. et al. Multiscale agent‐based consumer market modeling. Complexity15, 37–47 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Said, L. B., Bouron, T. & Drogoul, A. Agent-based interaction analysis of consumerbehavior. In Proc. First International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems: Part 1 184–190 (ACM, 2002).

- 53.Schenk, T. A., Löffler, G. & Rauh, J. Agent-based simulation of consumer behavior in grocery shopping on a regional level. J. Bus. Res.60, 894–903 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang, T. & Zhang, D. Agent-based simulation of consumer purchase decision-making and the decoy effect. J. Bus. Res.60, 912–922 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gotts, N. M., Polhill, J. G. & Law, A. N. R. Agent-based simulation in the study of social dilemmas. Artif. Intell. Rev.19, 3–92 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elliott, E. & Kiel, L. D. Exploring cooperation and competition using agent-based modeling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA99, 7193–7194 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ceschi, A., Hysenbelli, D., Sartori, R. & Tacconi, G. Cooperate or Defect? How an Agent Based Model Simulation on Helping Behavior Can Be an Educational Tool. In Methodologies and Intelligent Systems for Technology Enhanced Learning Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, Vol. 292 (eds. Mascio, T., Gennari, R., Vitorini, P., Vicari, R. & de la Prieta, F.) Ch. 24 (Springer, 2014).

- 58.Marsella, S. C., Pynadath, D. V. & Read, S. J. PsychSim: Agent-based modeling of social interactions and influence. In Proc. International Conference on Cognitive Modeling 243–248 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, 2004).

- 59.Bernhardt, K. Agent-based modeling in transportation. Artif. Intell. Transport. Inf. Appl.E-C113, 72–80 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dia, H. An agent-based approach to modelling driver route choice behaviour under the influence of real-time information. Transport. Res. C Emerg. Technol.10, 331–349 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 61.Handford, D. & Rogers, A. Modelling Driver Interdependent Behaviour in Agent-Based Traffic Simulations for DisasterManagement. In Advances on Practical Applications of Agents and Multiagent Systems Advances in Intelligent and Soft Computing, Vol. 88 (eds. Demazeau, Y., Pěchoucěk, M., Corchado, J. M. & Pérez, J. B.) Ch. 21 (Springer, 2011).

- 62.Manley, E., Cheng, T., Penn, A. & Emmonds, A. A framework for simulating large-scale complex urban traffic dynamics through hybrid agent-based modelling. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst.44, 27–36 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mizuta, H. Evaluation of metropolitan traffic flow with agent-based traffic simulator and approximated vehicle behavior model near intersections. In Proc. 2015 Winter Simulation Conference 3925–3936 (IEEE Press, 2015).

- 64.Paruchuri, P., Pullalarevu, A. R. & Karlapalem, K. Multi agent simulation of unorganized traffic. In Proc. First International Joint Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems: Part 1 176–183 (ACM, 2002).

- 65.Wahle, J., Bazzan, A. L. C., Klügl, F. & Schreckenberg, M. Decision dynamics in a traffic scenario. In Traffic and Granular Flow ’99 Vol. 287, Ch. 8. 669–681 (Springer, 2000).

- 66.Wahle, J. & Schreckenberg, M. A multi-agent system for on-line simulations based on real-world traffic data. In Proc. 34th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 9 (IEEE, 2001).

- 67.Zhang, L. et al. Integrating an agent-based travel behavior model with large-scale microscopic traffic simulation for corridor-level and subarea transportation operations and planning applications. J. Urban Plan. Dev.139, 94–103 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garg, A. et al. Towards a physiological scale of vocal fold agent-based models of surgical injury and repair: sensitivity analysis, calibration and verification. Appl. Sci.9, 2974 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li, N. Y. K. et al. Translational systems biology and voice pathophysiology. Laryngoscope120, 511–515 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li, N. Y. K. et al. A patient-specific in silico model of inflammation and healing tested in acute vocal fold injury. PLoS ONE3, e2789 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li, N. Y. K., Vodovotz, Y., Hebda, P. A. & Verdolini Abbott, K. Biosimulation of inflammation and healing in surgically injured vocal folds. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol.119, 412–423 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li, N. Y. K. et al. Biosimulation of acute phonotrauma: an extended model. Laryngoscope121, 2418–2428 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Seekhao, N., JaJa, J., Mongeau, L. & Li-Jessen, N. Y. K. In situ visualization for 3D agent-based vocal fold inflammation and repair simulation. Supercomput. Front. Innov.4, 68 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Seekhao, N., Shung, C., JaJa, J., Mongeau, L. & Li-Jessen, N. Y. K. Real-timeagent-based modeling simulation with in-situ visualization of complexbiological systems - a case study on vocal fold inflammation and healing. In 15th IEEE International Workshop on High Performance Computational Biology (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 75.Seekhao, N., Shung, C., JaJa, J., Mongeau, L. & Li-Jessen, N. Y. K. High-performance agent-based modeling applied to vocal fold inflammation and repair. Front. Physiol.9, 304 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Seekhao, N. et al. High-Performance Host-Device Scheduling and Data-Transfer Minimization Techniques for Visualization of 3D Agent-Based Wound Healing Applications. In Regular Research Paper in the 25th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Processing Techniques and Applications. PDPTA 19 (2019). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Heinke, D., Carslaw, G. & Christian, J. An agent-based simulation of destigmatization (DSIM): introducing a contact theory and self-fulfilling prophecy approach. J. Artif. Soc. Soc. Simul.16, 10 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nowak, S. A., Matthews, L. J. & Parker, A. M. A general agent-based model of social learning. Rand Health Q7, 10 (2017). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G. & Haake, S. Measuring the self-stigma associated with seeking psychological help. J. Counsel. Psychol.53, 325–337 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clough, B. A., Hill, M., Delaney, M. & Casey, L. M. Development of a measure of stigma towards occupational stress for mental health professionals. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol.55, 941–951 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bradshaw, N. & Cooper, A. L. Medical privacy and the professional singer: Injury stigma, disclosure, and professional ramifications on Broadway. J. Sing.74, 513–520 (2018). [Google Scholar]