Abstract

The study aims to explore whether work-life balance mediates the impact of work-family conflict and its dimensions on psychological well-being. Using a survey method, data were collected from a sample of 258 working women in Hebei province in China. The analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS and the PROCESS macro in order to test the mediation model. The findings show that work-family conflict has an indirect effect on psychological well-being through work-life balance. In the case of work-to-family conflict, a suppression effect is detected in which the mediator shows an underlying relationship between the work-to-family conflict and psychological well-being. On the other hand, family-to-work conflict is fully moderated by work-life balance. Based on these results, it can be concluded that enhancing the quality of work-life balance may help to reduce the negative impact of work-family conflict on psychological health. The findings of this study can be beneficial to organizations and policy makers to formulate policies that would enhance the mental health and work productivity of women professionals in China.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-024-79322-1.

Keywords: Work-family conflict, Work-life balance, Psychological well-being, Mediator analysis

Subject terms: Psychology, Health care

Introduction

Work and life are two most essential aspects in individuals’ lives. Individuals struggle to seek after work-life balance but rarely achieve. Working women struggle to achieve balance between these two important spheres of life. It has been observed that the 21st-century women from all walks of life want to have it all: a happy family, successful career and personal time and space for each individual1. Nevertheless, women face more challenges than men in managing the work-life balance2. This perhaps is due to their social and cultural roles as the main caregivers of children, many times of elderly parents especially in the developing world, and work responsibilities3. Generally, women take more responsibilities in the family care: housekeeping, child-rearing and elderly parents caring. In addition to their regular workday, mothers will typically spend 2.9 h a day taking care of their children’s needs and domestic responsibilities4.

Work and life can cause conflict when they contend with each other5. Work-family conflict is defined as the interference between work and family that results from demands originating from work, family or both domains6. This conflict is particularly salient among working women, who often face the dual burden of work responsibilities and family obligations. Generally, work-family conflict is believed to be bidirectional in nature7,8. It implies the interference of the work to family and family to work9. Work-to-family interference was defined as “a form of interrole conflict occurring as a result of general demands and strain created by the job interfering with one’s ability to perform family related responsibilities”. Meanwhile, family-to-work interference was defined as “role conflict resulting from general demands and strain created by the family interfering with an employee’s ability to perform responsibilities related to work”8,10.

The Chinese context is particularly relevant because of the rapid economic transformation and changing social culture on work-family conflict. Even though China has been interacting and assimilating with global society more and more in recent years, and the participation of women in the workplace has been increasing greatly. It is unable to alter people’s traditional gender roles expectations at all age ranges. Women are often expected to prioritize family responsibilities over their careers, which exacerbates work-family conflict and can negatively impact their psychological well-being11. Therefore, it is important to know how these conflicts influence their psychological health in order to improve their health and productivity.

Psychological well-being is a multidimensional construct that encompasses various dimensions such as positive affect, life satisfaction, self-esteem, and purpose in life12. It is an essential aspect of an individual’s overall health and quality of life, and has been linked to various positive outcomes such as improved work performance, job satisfaction, and reduced absenteeism13,14. Low psychological well-being is closely related to decreased job performance and productivity.

Numerous studies have proven that work-family conflict has a negative impact on psychological well-being, particularly among working women15,16. Unbalance such as “non-achievement in work” and “fulfillment in private life” is likely to deteriorate their psychological well-being16–18. Research shows that Chinese female healthcare workers’ mental health is significantly influenced by work-family conflict19. However, much of the research focuses solely on the direct effects of work-family conflict on psychological well-being, neglecting the role of potential mediating variables, especially in the context of Chinese professional women16,20,21.

One potential mechanism is work-life balance (WLB), which refers to the degree to which an individual can manage and harmonize their work and family responsibilities effectively. Previous studies have proved that work-life balance tend to play as a mediator in the relationships of well-being-related factors22,23. It is posited to mitigate the negative effects of work-family conflict on psychological well-being by providing a sense of control and satisfaction over one’s life domains. It is hypothesized that women who can achieve a better balance between their work and family roles may experience less stress and better psychological outcomes, despite the presence of work-family conflict.

This study aims to investigate the relationship between work-family conflict, work-life balance, and psychological well-being among working women in China. Specifically, it examines whether work-life balance mediates the effect of work-family conflict and its dimensions on psychological well-being. Therefore, we assume that:

H1 – WLB mediates the relationship between work-family conflict and psychological well-being.

H2 – WLB mediates the relationship between work-to-family conflict and psychological well- being.

H3 – WLB mediates the relationship between family-to-work conflict and psychological well- being.

By employing a mediation model, this research seeks to elucidate the pathways through which work-family conflict impacts psychological well-being and to identify potential leverage points for interventions aimed at improving the well-being of professional women.

Methodology

The empirical data were collected using an online survey method. Structured questionnaires revised in Chinese version were used. Then consistency reliability was tested. To conduct mediation analysis, IBM SPSS and special PROCESS macro have been used. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Instrument

Work-family conflict

The independent variable will be measured using the Work-Family Conflict Scale (WFCS) by Netemeyer et al. (1996). The scale includes 2 subscales with 5 items each: subscale of work-to-family conflict (WFC) and family-to-work conflict (FWC). Participants will be asked to rate their agreement with each topic using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). No reverse items are included. The summative answers to the scale and sub-scale items will be used for scoring. Significant levels of work-family conflict will be indicated by higher scores, whereas lower scores demonstrate lower levels of work-family conflict. The revised Chinese version has been adopted in the study of Xu et al.24. The overall Cronbach’s α coefficient is 0.864, with Cronbach’s α coefficients for individual dimensions being 0.904 and 0.886 respectively.

Work-life balance

The mediating variable will be assessed using five items derived from the Satisfaction with Work-Family Balance Scale25, modified to emphasize private life. Respondents rated these items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). No reverse items are included. Higher scores indicate a higher level of work-life balance for the participants. The revised Chinese version of the Work-Life Balance Questionnaire has been adopted in the study of Wu26. The internal consistency coefficient for these items was 0.880.

Psychological well-being

The dependent variable was tested by the 18-item Chinese scale which was translated into Chinese based on the 84-item Ryff version27. People rank themselves from 1 to 6 on a Likert-type scale, with the categories “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. No reverse items are included. The majority of factor loadings were more than 0.60 in terms of factor validity. Cronbach’s α was at least 0.60 for each dimension and 0.92 for the overall scale in terms of dependability27,28.

Sample and data collection

The data were collected using the online questionnaire platform “Survey Star”. The target population included the full-time working women employed by public or private sectors in Hebei province of China across industries like education, healthcare, finance, and technology. Participants should be permanent residents of Hebei province, migrant or expatriates are excluded. Convenience sampling was used and invitations to participate were sent through companies and directly to their employees. A total of 258 respondents completed the questionnaires, and all gave their informed consent.

The average age of participants was 36.24 years (SD = 8.18). 15.9% of the respondents are single, Most were married (82.2%), with 46.1% having one child and 29.5% having two. Educationally, 58.5% held a bachelor’s degree, 19% had a master’s, 17.4% had an associate degree, and 1.2% held a doctorate. In terms of work hours, 48.1% worked 40–49 h per week, while 17.4% worked 50 or more. Most participants worked 40 h or more each week.

Data analysis

Mediation analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS and the PROCESS macro, with a bootstrapping method of 5000 samples to test the significance of direct and indirect effects. A number of linear models, as recommended by Field29 and Hayes30, were used to investigate the mediating impact. The mediating effect should be accepted if the indirect effect’s confidence interval doesn’t include a zero value; otherwise, it should be rejected29,30.

Research results

Reliability, descriptive statistics and correlations

The Cronbach’s Alfa test was performed to determine the scale reliabilities of all the constructs employed in the data analysis. The test results revealed no problems with how the data was used for the following analysis. The values fluctuated from 0.86 for family-to-work up to 0.95 for psychological well-being (See Table 1). Those values were within the range indicated by Field29 and suggested good reliability.

Table 1.

Reliabilities, means, standard deviations and correlations.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reliability | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.92 | 0.95 | |

| Mean | 27.57 | 15.63 | 11.94 | 16.72 | 65.33 | |

| Std. deviation | 7.98 | 4.76 | 4.46 | 4.17 | 11.96 | |

| 1 | Work-Family Conflict | 1 | ||||

| 2 | Work-to-Family Conflict | 0.68*** | 1 | |||

| 3 | Family-to-Work Conflict | 0.72*** | 0.49*** | 1 | ||

| 4 | Work-Life Balance | -0.47*** | -0.36*** | -0.32*** | 1 | |

| 5 | Psychological Well-being | -0.36*** | -0.02 | -0.16* | 0.52*** | 1 |

Note: *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). ***Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level (2-tailed).

The correlation analysis revealed the interdependencies among the variables under investigation. The mediator (WLB), the dependent variable (psychological well-being), and the predictors of the models (work-family conflict, work-to-family conflict, and family-to-work conflict) have moderately high correlations. WLB as a mediating variable in the research model has a correlation with both work-family conflict (r=-0.47) and psychological well-being (r = 0.52). This suggests that all three variables may be related in some way, thus it makes logical to include them all in the mediator model.

Mediator analysis

According to Field29 and Hayes30, mediating analysis refers to a series of regression analyses carried out in a specific order. In this study, WLB was considered as a mediator and work-family conflict was used as a predictor to predict psychological well-being in four-step mediator analyses. The following step eliminated the role of the mediator, WLB, using two components of the work-family conflict construct: work-to-family conflict and family-to-work as independent variables to assess the relationship with the respective psychological well-being.

Regression effect of work-family conflict on WLB

In this study, the four-step mediator analyses are presented in a sequential manner. The initial stage is the linear regression analysis which determines the correlation between the predictor and the mediation. Table 2 displays the results of all three regression models, which indicated statistically significant correlations between the mediator (WLB) and the predictor (work-family conflict and its dimensions). The work-family conflict variable showed the greatest correlation which explained 22% of the variations in the work-life balance variable.

Table 2.

The linear regression effect of work-family conflict and its dimensions on WLB.

| R-sq | F | Constant | Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | t | unst B | t | stan β | ||

| Work-family conflict -> WLB | ||||||

| 0.22 | 71.79*** | 23.77 | 27.53*** | -0.25 | -8.47*** | -0.47 |

| Work-to-family conflict -> WLB | ||||||

| 0.13 | 37.02*** | 21.57 | 25.86*** | -0.31 | -6.09*** | -0.36 |

| Family-to-work conflict -> WLB | ||||||

| 0.10 | 28.87*** | 20.27 | 28.75*** | -0.30 | -5.37*** | -0.32 |

Note: *** Coefficient is significant at the 0. 001 level.

Additionally, the overall construct had the greatest standardized regression coefficient (β=-0.47), followed by work-to-family conflict (β=-0.36), family-to-work conflict (β=-0.32).

Regression effect of work-family conflict and WLB on psychological well-being

Multiple regression analysis was the next stage of the mediator analysis, in which the mediator and the predictor were treated as independent variables in order to predict the result. In this instance, we examined how work-family conflict and its dimensions, as well as WLB, may be used as independent variables to explain psychological well-being. Table 3 presents an analysis of the findings.

Table 3.

The linear regression effect of work-family conflict, its dimensions and WLB on psychological well-being.

| R-sq | F | Constant | Conflict coefficients | Balance coefficients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | t | unst B | t | stan β | unst B | t | stan β | ||

| Work-family conflict + WLB -> Well-being | |||||||||

| 0.28 | 50.34*** | 50.29 | 10.62*** | -0.22 | -2.46* | -0.15 | 1.28 | 7.44*** | 0.45 |

| Work-to-family conflict + WLB -> Well-being | |||||||||

| 0.30 | 53.99*** | 29.90 | 7.31*** | 0.48 | 3.38*** | 0.19 | 1.67 | 10.39*** | 0.58 |

| Family-to-work conflict + WLB -> Well-being | |||||||||

| 0.27 | 46.23*** | 40.16 | 10.66*** | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 1.49 | 9.16*** | 0.52 |

Note: * Coefficient is significant at the 0.05 level. *** Coefficient is significant at the 0.001 level.

The analysis showed that WLB and work-family conflict and its dimension work-to-family conflict were good predictors of psychological Well-being. R square reached 0.28 when full work-family conflict construct was taken. When work-to-family conflict was taken, R square reached 0.30. Both of the work-family conflict and WLB factors were significant independent variables at the 0.05 level, indicating that they were both acceptable predictors of a dependent variable.

Depending on whether work-family conflict component was taken into consideration, the standardized regression coefficients relating to the relationships between the mediator—WLB—and psychological well-being ranged from 0.45 (work-family conflict) to 0.58 (work-to-family conflict). The relationship between the predictor-work-family conflict and its dimensions and the outcome-psychological well-being was influenced by the second independent variable (mediator), as indicated by the standardized regression coefficients, which varied between − 0.15 (the predictor-work-family conflict) and 0.19 (the predictor-work-to-family conflict).

Regression effect of work-family conflict on psychological well-being

The following step involved determining the predictor’s direct impact on the outcome variable. Table 4 displays the results of the linear regression analysis that was done between the outcome variable, psychological well-being, and the predictor, in this case, work-family conflict and its dimensions. Work-family conflict was clearly the biggest predictor of the direct linear regression relationship (R2 = 0.13), but family-to-work conflict was marginally less evident (R2 = 0.02). Standardized regression coefficients were the highest for work-family conflict as the predictor (-0.36) and the lowest for family-to-work conflict (-0.16).

Table 4.

The linear regression effect of work-family conflict and its dimensions on psychological well-being.

| R-sq | F | Constant | Coefficients | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| value | t | unst B | t | stan β | ||

| Work-family conflict -> Well-being | ||||||

| 0.13 | 37.34*** | 80.75 | 30.83*** | -0.54 | -6.11*** | -0.36 |

| Work-to-family conflict -> Well-being | ||||||

| 0.00 | 0.08 | 66.01 | 25.78*** | -0.04 | -0.28 | -0.02 |

| Family-to-work conflict -> Well-being | ||||||

| 0.02 | 6.40* | 70.32 | 33.36*** | -0.42 | -2.53* | -0.16 |

Note: * Coefficient is significant at the 0. 05 level. *** Coefficient is significant at the 0. 001 level.

Mediation test

The final step in the mediation analysis involved evaluating the mediator’s influence on the predictor-outcome relationship and determining the presence of mediation. Table 5 summarizes the key statistical results and the conclusions regarding the hypotheses tested. The mediation analysis proved that WLB serves as a mediator in the relationship between work-family conflict and psychological well-being, as well as for the structural dimensions of work-family conflict. Specifically, H1 demonstrated partial mediation, H2 revealed a suppression effect, and H3 confirmed full mediation.

Table 5.

Mediation test results.

| Total effect | Direct effect | Indirect effect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 |

Work family conflict -> Balance -> Psychological well-being |

-0.5400 LLCI=-0.7141 ULCI=-0.3660 |

-0.2237 LLCI =-0.4025 ULCI =-0.0448 |

-0.3164 BootLLCI= -0.4766 BootULCI=-0.1776 |

| H2 | Work-to-family conflict -> Balance -> Well-being |

-0.0438 LLCI=-0.3528 ULCI = 0.2652 |

0.4768 LLCI = 0.1991 ULCI = 0.7545 |

-0.5206 BootLLCI =-0.7829 BootULCI =-0.2759 |

| H3 | Family-to-work conflict -> Balance -> Well-being |

-0.4186 LLCI=-0.7444 ULCI=-0.0928 |

0.0238 LLCI=-0.2748 ULCI = 0.3225 |

-0.4425 BootLLCI =-0.7082 BootULCI =-0.1923 |

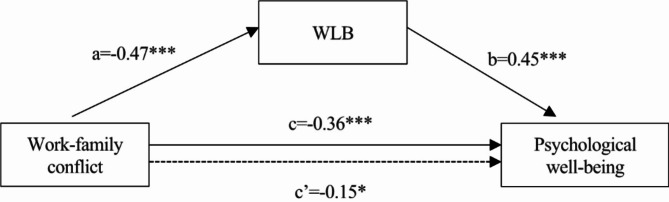

The results for H1 show that work-life balance partially mediates the relationship between work-family conflict and psychological well-being. The total effect of work-family conflict on psychological well-being was significant (-0.5400), indicating that higher levels of conflict lead to lower psychological well-being. The direct effect remained significant (-0.2237), and the indirect effect through work-life balance was also significant (-0.3164). See Fig. 1. This partial mediation suggests that while work-life balance plays a crucial role in buffering the negative impact of work-family conflict, there are additional factors influencing psychological well-being that are not accounted for by work-life balance alone.

Fig. 1.

The mediating effect of WLB between work-family conflict and psychological well-being.

a, effect of work-family conflict on WLB; b, effect of WLB on psychological well-being; c, total effect of work-family conflict on psychological well-being; c’, direct effect of work-family conflict on psychological well-being. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

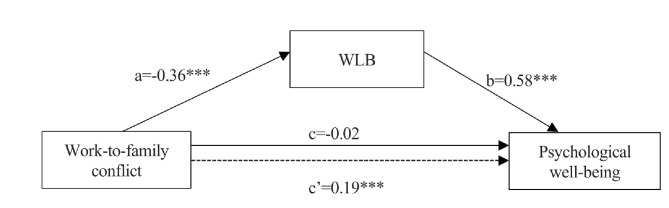

For H2, the relationship between work-to-family conflict and psychological well-being demonstrated a suppression effect. The suppression effect occurs when a third variable (the suppressor) clarifies or changes the relationship between two variables, revealing a hidden or stronger connection that wasn’t initially apparent31. In this case, the total effect of work-to-family conflict on psychological well-being was not significant (-0.0438), meaning work-to-family conflict didn’t strongly affect psychological well-being. But when work-life balance was added as a mediator, the relationship changed. The direct effect was positive and significant (0.4768), and the indirect effect through work-life balance was negative and significant (-0.5206). See Fig. 2. This suppression effect suggests that work-life balance reveals a hidden relationship between work-to-family conflict and psychological well-being that is not apparent when considering the total effect alone. This complex relationship indicates that other underlying mechanisms might be at play, possibly involving factors such as job resources, personal coping strategies, or organizational support systems that could influence how work-to-family conflict impacts psychological well-being.

Fig. 2.

The mediating effect of WLB between work-to-family conflict and psychological well-being.

a, effect of work-to-family conflict on WLB; b, effect of WLB on psychological well-being; c, total effect of work-to-family conflict on psychological well-being; c’, direct effect of work-to-family conflict on psychological well-being. ***p < 0.001.

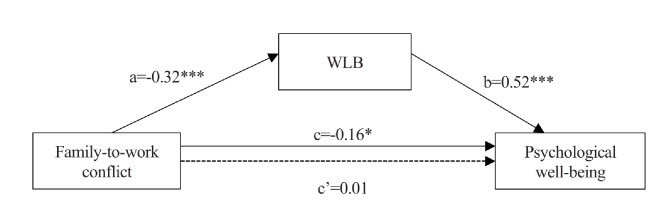

The results for H3 indicate full mediation of the relationship between family-to-work conflict and psychological well-being by work-life balance. The total effect of family-to-work conflict on psychological well-being was significant (-0.4186), but the direct effect was not significant (0.0238), while the indirect effect through work-life balance was significant (-0.4425). See Fig. 3. This finding suggests that work-life balance fully accounts for the negative impact of family-to-work conflict on psychological well-being. This full mediation highlights the critical role of work-life balance in managing the adverse effects of family-to-work conflict, implying that interventions aimed at improving work-life balance could be highly effective in enhancing the psychological well-being of professional women dealing with family-to-work conflict.

Fig. 3.

The mediating effect of WLB between family-to-work conflict and psychological well-being.

a, effect of family-to-work conflict on WLB; b, effect of WLB on psychological well-being; c, total effect of family-to-work conflict on psychological well-being; c’, direct effect of family-to-work conflict on psychological well-being. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

Basically, all the hypotheses were supported, no single 95% confidence level interval of the indirect effect had crossed the zero value. The mediation effect was present in every interaction under analysis. Work-life balance significantly mediates the relationships between work-family conflict including its dimensions and psychological well-being.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine the mediating role of work-life balance in the relationship between work-family conflict and psychological well-being among working women in China. Our findings supported the mediator role of work-life balance in the variables.

In line with previous studies, the findings of the present study reveal that work-life balance has a significant and positive correlation with psychological well-being32. Individuals who perceive a balance between their work and personal lives report higher levels of life satisfaction and overall well-being33–35. This positive relationship is also seen in the present study where work-life balance fully mediates the relationship between work-family conflict and psychological well-being. Thus, employees who are capable of managing their work and personal life are expected to have higher psychological well-being which in turn yields positive effects like job satisfaction and reduced stress levels.

The findings of this study also support the previous research works that have established work life balance as a mediator in different well-being related relationships22,34. For instance, Isa and Indrayati8 and Vernia and Senen36 demonstrated that work-life balance mediates the relationship between work-family conflict and employee performance. In the same way, Taşdelen-Karçkay and Bakalım37 found that WLB fully mediates the relationship between work-family conflict and life satisfaction. This study further builds on these findings by establishing that work-life balance also acts as a mediator in the work-family conflict and psychological well-being relationship.

Mediating role of work-life balance

The present study revealed that work-life balance partially mediates the relationship between work-family conflict and psychological well-being. The total effect of work-family conflict on psychological well-being was significant, indicating that higher levels of conflict lead to lower psychological well-being. The direct effect remained significant, and the indirect effect through work-life balance was also significant. This partial mediation suggests that while work-life balance plays a crucial role in buffering the negative impact of work-family conflict, other factors also influence psychological well-being. This finding supports previous studies indicating that work-life balance can mitigate some adverse effects of work-family conflict but cannot entirely eliminate them38,39.

Surprisingly, the results showed that work-to-family conflict had a suppression effect on psychological well-being of the female employees. The total effect of work-to-family conflict on the level of psychological well-being was not statistically significant, but the direct effect was positive and significant, whereas the indirect effect through the level of work-life balance was negative and statistically significant. This suppression effect indicates that work-life balance uncovers another interaction between work-to-family conflict and psychological well-being that may not be noticeable when taking into account the total impact. This complex relationship implies that work-to-family conflict is mediated by work-life balance in practical terms. Enhancing the work-life conflict might help in minimizing the impact of this conflict on the well-being of workers. Furthermore, the degree to which work-to-family conflict influences psychological well-being may be mediated by other variables such as the job resources, coping strategies, or organizational support, pointing out areas where organizational interventions might be effective.

The results for H3 indicate full mediation of the relationship between family-to-work conflict and psychological well-being by work-life balance. The total effect of family-to-work conflict on well-being was significant, but the direct effect was not significant, while the indirect effect through work-life balance was significant. This finding suggests that work-life balance fully accounts for the negative impact of family-to-work conflict on psychological well-being. This full mediation stresses the importance of work-life balance in reducing the negative impact of family-to-work conflict, suggesting that interventions intended to increase work-life balance can be very effective in promoting the psychological well-being of working women caused by family-to-work conflict.

Practical implications

Based on the results of this study, it can be concluded that by enhancing the work-life balance, the adverse impact of work-family conflict on psychological well-being may be reduced, especially among working women. Employers can implement flexible work policies such as remote work and flexible hours, so that they can balance between work and family. Supportive leave policies including parental leave, caregiver leave or even mental health days can support female employees to take time off and promote a healthy work-life balance. It is also possible to offer wellness programs focused on mental health and stress management. For example, Workshops and resources can help employees develop coping strategies and improve their overall psychological well-being; Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) can offer valuable counseling services, while regular check-ins from managers can help identify and address potential conflicts early on. What’s more, it is necessary to establish a healthy organizational culture that supports employees’ work-life balance and psychological well-being. It is important for leaders to set an example of productive work behaviors and to discourage communication after hours in order to emphasize the value of personal time. Such policies would not only improve working women’s psychological well-being but also promote gender equality.

Limitations and future research

There are several limitations of this study that have to be noted. First, this study’s cross-sectional design restricts the possibility of making a causal relationship between variables. While these correlations are evident, the absence of time series data means that causality cannot be claimed conclusively. The longitudinal research designs would allow for an increasing number of data waves with changes over time, providing more convincing proof of long-term consequences and the dynamic nature of the relationships among variables. The longitudinal research design should be used in future research studies to capture changes that occur over time and to give a clear understanding of the causal relationships between work-family conflict, work-life balance, and psychological well-being. Second, this research adopted a convenience sampling method, focusing on Chinese working women in several sectors in Hebei province. Due to possible sampling bias, the results may not apply to all working women, especially those in different industries or geographical areas. The external validity of the results may be limited. Future studies should address this by using a more varied and random selection method that includes people from different industries, geographical areas, and socioeconomic backgrounds to improve representativeness and lower bias. Last but not the least, the use of online surveys for data collection may cause potential exclusion of certain participants. While the “China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC)” reports that as of June 2023, China had nearly 1.1 billion internet users (1.079 billion), with an internet penetration rate of 76.4%40, there still remains a possibility of participant exclusion. In future research, we suggest using different data collection techniques such as paper-based surveys or in-person interviews for those who may not have reliable internet access or are less familiar with online tools.

Conclusion

Therefore, this research fills the gap in the literature on the mediating effect of WLB in the relationship between work-family conflict and psychological well-being among working women in China. The study stresses the role of work-life balance in reducing the impact of work-family conflict, showing that the mediation models vary depending on the type of conflict, work-to-family and family-to-work. These findings also stress the importance of organizations’ efforts to promote work-life balance initiatives to improve the psychological health of employees and positively impact organizational productivity and employee satisfaction.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Xiaoying: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Collection, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing.Mohammad Saipol: Supervision, Project Administration, Writing - Review & Editing.

Funding

This research was supported by 2024 Science and Technology Innovation Project from Cangzhou Science and Technology Association of Hebei China (grant no. CZKX2024069); and 2024 Cangzhou Social Science Development Research Project (grant no. 2024318).

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. This study protocol has been reviewed and approved by Faculty of Education, Cangzhou Normal University Ethics Committee. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript and consent to its publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Kashyap, V. & Verma, N. Linking dimensions of employer branding and turnover intentions. Int. J. Organizational Anal.26 (2), 282–295 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundaresan, S. Work-life balance–implications for working women. OIDA Int. J. Sustainable Dev.7 (7), 93–102 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adisa, T. A., Aiyenitaju, O. & Adekoya, O. D. The work–family balance of British working women during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Work-Applied Manage.13 (2), 241–260 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 4.White, C. & Maniam, B. Flexible working arrangements, worklife balance, and working women. J. Bus. Acc.13 (1), 59–73 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahmood, M., Rizvi, S. A. A. & Bibi, M. Educated Working Women and their work-life conflict and work-Life Balance. Pakistan J. Gend. Stud.17 (1), 105–126 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huffman, A. et al. Work-family conflict across the lifespan. J. Managerial Psychol.28 (7/8), 761–780 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hill, E. J. Work-family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and mothers, work-family stressors and support. J. Fam. Issues. 26 (6), 793–819 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isa, M. & Indrayati, N. The role of work–life balance as mediation of the effect of work–family conflict on employee performance. SA J. Hum. Resource Manage.21, 10 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kappagoda, U. Emotional intelligence as a predictor of work-family conflict among school teachers in North Central Province in Sri Lanka. in Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Management and Economics-2013, University of Ruhuna, Sri Lanka. (2013).

- 10.Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S. & McMurrian, R. Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J. Appl. Psychol.81 (4), 400 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang, H., Ma, A. & Guo, T. Gender concept, work pressure, and work–family conflict. Am. J. Men’s Health. 14 (5), 1557988320957522 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Atari, R. & Han, S. Perceived discrimination, ethnic identity, and psychological well-being among arab americans. Couns. Psychol.46 (7), 899–921 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diener, E. Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. Am. Psychol.55 (1), 34 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trudel-Fitzgerald, C. et al. Psychological well-being as part of the public health debate? Insight into dimensions, interventions, and policy. BMC Public. Health. 19 (1), 1712 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin, W. R., Chen, H. M. & Wang, Y. C. Work-family conflict and psychological well-being of tour leaders: the moderating effect of leisure coping styles. Leisure Sci.44 (7), 786–807 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Obrenovic, B. et al. Work-family conflict impact on psychological safety and psychological well-being: a job performance model. Front. Psychol.11, 475 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujimoto, T. et al. Overtime reduction, work-life balance, and psychological well-being for research and development engineers in Japan. in. IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management. 2013. IEEE. (2013).

- 18.Karakose, T., Yirci, R. & Papadakis, S. Exploring the interrelationship between covid-19 phobia, work–family conflict, family–work conflict, and life satisfaction among school administrators for advancing sustainable management. Sustainability. 13 (15), 8654 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, Z. & Hong, L. Work–family conflict and mental health among Chinese female healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: The moderating effects of resilience. in Healthcare. MDPI. (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Akram, M. F. Relationship of work-family conflict with job demands, Social Support and Psychological Well-Being of University Female Teachers in Punjab. Bull. Educ. Res.42 (1), 45–66 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yucel, D. & Fan, W. Work–family conflict and well-being among German couples: a longitudinal and dyadic approach. J. Health Soc. Behav.60 (3), 377–395 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazemi, S. et al. The effect of work-family conflict and work-Family Enrichment on turnover intention and Psychological Well-Being: the mediating role of work-life balance. Psychol. Methods Models. 8 (27), 83–108 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stankevičienė, A. et al. The mediating effect of work-life balance on the relationship between work culture and employee well-being. J. Bus. Econ. Manage.22 (4), 988–1007 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu, F. et al. Analysis of the relationship between work-family conflict and work-family support path for female nurses with two children. Chin. J. Social Med.38 (5), 507–510 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valcour, M. Work-based resources as moderators of the relationship between work hours and satisfaction with work-family balance. J. Appl. Psychol.92 (6), 1512–1523 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu, X. A study on the relationship between perceived organizational support, psychological capital and work-life balance, in Hebei University. Hebei University: Hebei, China. (2016).

- 27.Li, R. H. Reliability and validity of a shorter Chinese version for Ryff’s psychological well-being scale. Health Educ. J.73 (4), 446–452 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li, R. H. & Yu, M. N. Reliability, validity, and Measurement Invariance of the brief Chinese version of Psychological Well-being scale among College Students. Chin. J. Guidance Couns.46, 127–154 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics (Sage publications limited, 2024).

- 30.Hayes, A. F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A regression-based Approach (Guilford, 2017).

- 31.Cheung, G. W. & Lau, R. S. Testing mediation and suppression effects of latent variables: bootstrapping with structural equation models. Organizational Res. Methods. 11 (2), 296–325 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen, T. D. & Martin, A. The work-family interface: a retrospective look at 20 years of research in JOHP. J. Occup. Health Psychol.22 (3), 259 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vatharkar, P. Relationship between Role, Conflict and Work Life balance–mediation of job satisfaction. Imperial J. Interdisciplinary Res. (IJIR), 3. (2017).

- 34.Abdul Jalil, N. I. et al. The relationship between Job Insecurity and Psychological Well-Being among Malaysian precarious workers: work–life balance as a Mediator. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 20 (3), 2758 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenhaus, J. H., Collins, K. M. & Shaw, J. D. The relation between work–family balance and quality of life. J. Vocat. Behav.63 (3), 510–531 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vernia, D. M. & Senen, S. H. Work-Family Conflict, Emotional Intelligence, Work-Life Balance, and Employee Performance. in 6th Global Conference on Business, Management, and Entrepreneurship (GCBME 2021). Atlantis Press. (2022).

- 37.Taşdelen-Karçkay, A. & Bakalım, O. The mediating effect of work–life balance on the relationship between work–family conflict and life satisfaction. Australian J. Career Dev.26 (1), 3–13 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Higgins, C. A., Duxbury, L. E. & Irving, R. H. Work-family conflict in the dual-career family. Organizational Behav. Hum. Decis. Processes. 51 (1), 51–75 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grzywacz, J. G. & Bass, B. L. Work, Family, and Mental Health: testing different models of work-family fit. J. Marriage Family, 65(1). (2003).

- 40.Wang, S. et al. China University Online Public Opinion Risk Dataset (IEEE Access, 2024).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.