Summary

Background

The influence of the gut microbiota on long-term immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) efficacy and immune-related adverse events (irAEs) is poorly understood, as are the underlying mechanisms.

Methods

We performed gut metagenome and metabolome sequencing of gut microbiotas from patients with lung cancer initially treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy and explored the underlying mechanisms mediating long-term (median follow-up 1167 days) ICI responses and immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Results were validated in external, publicly-available datasets (Routy, Lee, and McCulloch cohorts).

Findings

The ICI benefit group was enriched for propionate (P = 0.01) and butyrate/isobutyrate (P = 0.12) compared with the resistance group, which was validated in the McCulloch cohort (propionate P < 0.001, butyrate/isobutyrate P = 0.002). The acetyl-CoA pathway (P = 0.02) in beneficial species mainly mediated butyrate production. Microbiota sequences from irAE patients aligned with antigenic epitopes found in autoimmune diseases. Microbiotas of responsive patients contained more lung cancer-related antigens (P = 0.07), which was validated in the Routy cohort (P = 0.02). Escherichia coli and SGB15342 of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii showed strain-level variations corresponding to clinical phenotypes. Metabolome validation reviewed more abundant acetic acid (P = 0.03), propionic acid (P = 0.09), and butyric acid (P = 0.02) in the benefit group than the resistance group, and patients with higher acetic, propionic, and butyric acid levels had a longer progression-free survival and lower risk of tumor progression after adjusting for histopathological subtype and stage (P < 0.05).

Interpretation

Long-term ICI survivors have coevolved a compact microbial community with high butyrate production, and molecular mimicry of autoimmune and tumor antigens by microbiota contribute to outcomes. These results not only characterize the gut microbiotas of patients who benefit long term from ICIs but pave the way for “smart” fecal microbiota transplantation. Registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000032088).

Funding

This work was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7232110), National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-A-072, 2023-PUMCH-C-054), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2022-I2M-C&T-B-010).

Keywords: Gut microbiome, Lung cancer, Immune checkpoint inhibitor, Metabolites, Molecular mimicry

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

There is growing evidence that the gut microbiota influences both initial ICI efficacy and the development of irAEs. Although underlying mechanisms mediated by microbiota in this context - such as molecular mimicry - are widely hypothesized, no direct data supporting these hypotheses are available.

Added value of this study

This study not only characterizes the gut microbiotas of patients who benefit long term from ICIs but also paves the way for “smart” fecal microbiota transplantation, where a specific bacterial formulation is designed for cancer patients receiving immune checkpoint inhibitors containing species with favorable strain dynamics, butyrate production, and mimicking tumor but not autoimmune antigens.

Implications of all the available evidence

Although hypothesized, this is the first study to provide empirical evidence that molecular mimicry between the microbiome and host or cancer peptides drive irAEs and responses, respectively. Furthermore, this study provides new insights into species-level variations and associated clinical responses.

Introduction

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are now standard of care for many cancer patients, including those living with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).1 Although ICIs can prolong survival, sometimes over the longer term up to ten years,2 many patients still die from their disease.3 Groups of patients experiencing long term survival benefits are especially informative, as they have not experienced the therapy resistance and immune-related adverse events (irAEs) that characterize treatment failure in many patients. Understanding what distinguishes this group of patients from those with early relapse, resistance, and adverse events could help to define the underlying biological mechanisms governing outcomes and provide targets for intervention.

There is growing evidence that the gut microbiota influences both ICI efficacy and the development of irAEs. The baseline gut microbiome is associated with initial ICI efficacy over the first six months,4 and, in preclinical models4, 5, 6 and clinical trials,7, 8, 9, 10 modifying the intestinal microbiome with probiotics or fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been shown to improve ICI efficacy. We previously detected differences in gut microbiota composition in patients with and without irAEs and showed that FMT from colitic irAE patients could induce irAEs in mice,11 providing a further causal link between the gut microbiota and irAEs. While existing research has mainly focused on the gut microbiota and initial ICI efficacy or irAE responses, there are little data on the relationship between the gut microbiome and long-term outcomes.

To address this gap, here - using landmark analysis - we comprehensively analyzed the relationships between the baseline gut microbiome and metabolome and long-term survival from lung cancer. As most patients with lung cancer receiving immunochemotherapy progress and/or develop irAEs within the first year,12,13 we set 1 year as the assessment timepoint defining long-term benefit. Furthermore, to provide insights into the underlying mechanisms governing survival, we explored microbiome-produced metabolites, antigen mimicry, and genomic variations in specific species.

Methods

Experimental design

This was a non-randomized, unblinded, prospective cohort study of two clinical cohorts.

Metagenome cohort

Patients with lung cancer initially treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy were consecutively enrolled into this prospective cohort study between May 2020 and May 2022 at the Lung Cancer Center, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Beijing, China. Fresh fecal samples were collected from all patients prior to commencement of ICI treatment. The inclusion criteria were: (i) age ≥18 years; (ii) diagnosed with advanced lung cancer (according to the TNM Classification for Lung Cancer, 8th edition14); (iii) initially treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapy as part of their care; and (iv) followed up for more than one year. Patients were excluded if they: (i) had unstable vital signs; and/or (ii) were exposed to antibiotics and/or probiotics within the four weeks prior to enrollment. The last follow-up date was July 23rd, 2024.

Metabolome cohort

Patients were consecutively and prospectively enrolled from June 2022 to May 2023 following the same criteria as the metagenome cohort at the same tertiary center but without the limitation of one-year follow-up. The last follow-up date was August 20th, 2024.

Demographic and clinical information including sex, age, tumor histopathological subtype, tumor stage,14 therapy regimen, ICI type and primary response, progression-free survival (PFS), progression-free interval (PFI), overall survival (OS), and irAE type and grade were collected. ICI efficacy was assessed according to RECIST v1.1 criteria.15 IrAEs in different organs were diagnosed according to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines on ICI-related toxicities.16 PFS, PFI, and OS were defined as the time from ICI initiation until disease progression or death, until progression or tumor-related death, and until death, respectively.

Patient grouping by long-term outcomes

Patients were classified into three groups according to their long-term outcomes: patients benefitting long term from ICIs (“benefit” group); patients failing to benefit due to severe irAEs (“severe irAE” group), and patients failing to benefit due to lack of efficacy (“resistance” group). We first created a four-quadrant diagram according to the two dimensions of efficacy and severe irAEs. “Good” efficacy was defined as a PFI ≥1 year or postoperative histopathological downstaging after neoadjuvant immunotherapy, while “severe irAE” was defined as ≥ grade 2 irAEs occurring within one year. The one-year timepoint was deemed suitable for assessing benefit from immunotherapy as, despite initially effectively controlling tumor progression in lung cancer patients, secondary failure usually develops within one year in patients taking combination immunochemotherapy.13 Therefore, the “benefit” group contained patients with good efficacy without severe irAEs, the “severe irAE” group contained patients with good efficacy but who developed severe irAEs; and the “resistance” group were patients with poor efficacy but without severe irAEs. Patients with poor efficacy and severe irAEs were classified into the severe irAE group or resistance group depending on the main reason for ICI discontinuation (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Taxonomic characteristics of baseline gut microbiota in the benefit (n = 24), severe irAE (n = 13), and resistance (n = 17) groups. (A) Grouping scheme diagram. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for PFS (log-rank P value was calculated after introduction of time-dependent interaction terms). (C) Shannon index of alpha diversities (compared by Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini-Hochberg correction). (D) Principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA) plot (compared by adonis function with 999 permutations and Benjamini-Hochberg correction). (E) Cladogram of linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe) analysis. (F) Differential genera by LEfSe analysis. (G) Co-occurrence networks of species (isolated nodes not shown). (H) Venn diagram of edge number of co-occurrence networks. #Good efficacy refers to patients with progression-free survival (PFI) ≥1 year or down-staged in postoperative pathology after neoadjuvant immunotherapy. ##Severe irAE refers to patients with ≥ grade 2 irAEs occurring within one year.

Fecal microbiota DNA sequencing and metagenome analyses

All fecal samples were subjected to paired-end sequencing with insert size 350 bp using the Illumina HiSeq 4000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Low-quality reads, including reads with low-quality bases, ambiguous “N” bases, and adapter contamination were filtered to obtain high-quality reads. Reads were then filtered by aligning against the human genome using Bowtie217 (--end-to-end --sensitive –I 200 -X 400) to remove host contamination.

Unaligned reads (clean data) were subsequently assembled into scaffolds with MEGAHIT18 (--presets meta-large), which were broken at ambiguous “N” junctions to obtain scaftigs. Clean data were mapped against scaftigs with Bowtie217 using the same parameters.

Scaftigs ≥500 bp were subjected to open reading frame (ORF) prediction with MetaGeneMark.19 Redundancy was removed with CD-HIT20 (-c 0.95 -G 0 -aS 0.9 -g 1 -d 0) to produce an initial gene catalogue. Clean data were mapped against the initial gene catalogue with Bowtie217 using the same parameters to determine gene abundance. Genes with ≥2 mapped reads were obtained as unigenes for subsequent analyses.

Taxonomic annotation was performed with MetaPhlAn3 (pangenome database version mpa_vJan21_CHOCOPhlAnSGB_202103).21 Species abundance was used for alpha diversity (Shannon and Simpson indices) and beta diversity (Bray–Curtis distance) calculations for principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA). Species characterizing the assessed groups (see above) were evaluated by linear discriminant analysis effect size (LEfSe).22

Functional annotation was performed by aligning genes with the EggNOG database (v2023.04) using DIAMOND.23

DESeq224 has been shown to perform well for analyzing taxonomic differences in metagenome studies25 and was used to screen for significant differential species between patients with different responses and those with and without irAEs. The relative abundances output by MetaPhlAn3 were multiplied by reads in each sample plus one, since each species was missing from at least one sample. Overrepresentation was defined as screening conditions of |log2(FC)| ≥ 1.0 and Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted P-value < 0.05. Heat maps were drawn with the pheatmap package in R after centered log-ratio transformation (not plus one prior to transformation). As a reference, LEfSe analysis22 was also performed between the two groups.

Differences in taxonomic and SCFAs (below) composition structure were assessed with PERMANOVA using the adonis function with default (999) permutations within the vegan package in R.

Microbial co-occurrence network analysis

Absolute species abundances were used for co-occurrence network construction. The inter-species Spearman rank correlations of different groups were calculated, and P-values were adjusted to account for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method. A correlation between two species was considered statistically robust if the correlation coefficient was >0.7 and the Benjamini-Hochberg-adjusted P-value was <0.01. Co-occurrence networks were constructed with the igraph and Hmisc packages in R and visualized using Gephi (v0.10.1)26 with degree and modules calculated.

Metabolite prediction using metagenome data

The abundances of UniRef90 gene families were obtained from annotations using HUMAnN3 with default parameters.21 Then, MelonnPan with the pretrained model27 was used to predict the relative abundances of 79 metabolites in each sample.

Butyrate/propionate-producing and -consuming gene identification

Based on a previous study,28 3055 gene sequences involved in butyrate production via four different pathways were retrieved from public repositories. Sample scaftigs were mapped against the butyrate-producing gene database using BLAST29 with a 1 × 10−5 E-value threshold. Butyrate-producing genes tended to be long, so identity or coverage parameters were not limited.

The genes essential for microbial butyrate degradation are acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (for the first step: butyrate→crotonyl-CoA) and enoyl-CoA hydratase (for the second step: crotonyl-CoA→3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA).30 For propionate, the succinate and acrylate pathways are essential for production and the 2-methylcitrate cycle for degradation.31,32 The abundances of relevant genes were extracted from the eggNOG ortholog group annotation result, and the ortholog group IDs are listed in Supplementary Data S1.

Correlations between differential species and both butyrate/propionate-producing and -consuming genes were calculated using Spearman rank correlation coefficients, which were visualized with heatmaps.

Landmark analyses for immune-related adverse events

Patients with poor efficacy often discontinued treatment shortly after progression, which might result in underestimations of their irAE hazards. Therefore, we performed landmark analysis for analyses related to irAEs to minimize this immortal time bias inherent in the time-dependent nature of irAEs. This approach has been widely used in irAE-related analyses, but with a shorted time-point of one to seven months.12,33, 34, 35 In this study, an irAE was considered present if it occurred within one year and absent if it did not occur within at least one year of ICI treatment or occurred after one year. In this way, all patients had the same exposure time to ICIs, which made following analyses more reliable.

Molecular mimicry analysis

Antigenic epitopes associated with autoimmune diseases (including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), autoimmune diseases of the skin and connective tissue (skin/CT), autoimmune hepatitis, autoimmune pancreatitis, ulcerative colitis (UC), autoimmune thrombocytopenic purpura, latent autoimmune diabetes in adults, autoimmune thyroiditis, and Graves’ disease) and lung cancer were identified from the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB; http://www.iedb.org/). 439 anticancer peptides (ACPs) composed entirely of natural amino acids were obtained from the CancerPPD database.36 The scaftigs of fecal samples or sequences of identical protein groups of specific differential species from the NCBI database were mapped against the amino acid sequences of these peptides by BLAST29 with a 1 × 10−2 E-value threshold. Autoimmune antigens with both identity and coverage of ≥80% were filtered out for further analyses.

Strain-level analyses of specific species

PanPhlAn37 was used to establish whether UniRef90 gene families from Escherichia coli and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii were present at sufficient abundance (or not) in each sample (--min_coverage 1 --left_max 1.70 --right_min 0.30). StrainPhlAn38 was used to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for different species-level genome bins (SGBs) of each species in different samples, and mutation rate summary tables for the concatenated multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) were generated and visualized with chord diagrams. Phylogenetic trees of SGBs were also constructed with StrainPhlAn38 and visualized with tvBOT.39 Phylogenetic signals were detected using Pagel’s lambda (λ) test to detect associations between evolutionary patterns and clinical phenotypes.40

Analysis of SCFAs in fecal samples by GC-MS

The standards of 2-methylvaleric acid, acetic acid, propionic acid, isobutyric acid, butyric acid, valeric acid, isovaleric acid, hexanoic acid, heptanoic acid, octanoic acid, nonanoic acid, and decanoic acid were obtained from Dr. Ehrenstorfer (Augsburg, Germany). Fecal samples were first extracted by liquid–liquid extraction with H2SO4 and methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE), with 2-methylvaleric acid as internal standard.

GC-MS analysis was performed on a Shimadzu GC2030-QP2020 NX gas chromatography-mass spectrometer using an HP-FFAP capillary column. A 1 μL aliquot of the analyte was injected in split mode (5:1). Helium was used as the carrier gas, the front inlet purge flow was 3 mL/min, and the gas flow rate through the column was 1.2 mL/min. The initial temperature was kept at 50 °C for 1 min, raised to 150 °C at a rate of 50 °C/min for 1 min, raised to 170 °C at a rate of 10 °C/min for 0 min, raised to 225 °C at a rate of 25 °C/min for 1 min, and then raised to 240 °C at a rate of 40 °C/min for 1 min. The injection, transfer line, quad and ion source temperatures were 220 °C, 240 °C, 150 °C and 240 °C. The energy was −70 eV in electron impact mode. Mass spectrometry data were acquired in Scan/SIM mode with an m/z range of 33–150 after a solvent delay of 3.75 min.

External validation

To verify the roles of SCFAs and molecular mimicry for both tumor antigens and ACPs, external validation was conducted using three publicly available metagenome datasets. The definitions of responses were retained as reported in each original study and are summarized in Supplementary Data S2. The processes for quality control, assembly, metabolite prediction, and antigen/ACP mapping followed the same pipeline as our cohort.

Ethics

The Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital (ZS-3037) approved the study protocol. All patients provided written informed consent. This clinical study was registered in the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry (ChiCTR2000032088).

Statistics

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies and percentages. Demographic and clinical characteristics were compared between groups with ANOVA, Pearson’s chi-squared tests, or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare differences in alpha diversity, abundances of predicted metabolites, and mapped sequences counts between groups. Benjamini-Hochberg correction was applied to adjust for the two-time comparisons among three groups. Survival was estimated by the Kaplan–Meier method, and differences in survival were evaluated with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to assess hazard ratios for PFS of different SCFA abundances. The proportional hazards assumption (PH assumption) was assessed by Schoenfeld test. If the assumption was found to be violated, time-dependent interaction terms would be introduced to improve the model’s fit. A two-sided P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified. All statistical analyses were performed in R v4.3.0 and SPSS v24.0 (IBM Statistics, Chicago, IL).

Role of funders

The funding sources had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Results

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics

In the metagenome cohort, 110 were considered for enrollment, and 54 patients were finally included in the metagenome analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1). The median follow-up time was 1167 days. There were 24, 13, and 17 patients in the benefit, severe irAE, and resistance groups, respectively, and they had comparable demographic characteristics (Table 1). The majority of patients had squamous cell carcinoma (48.1%) or adenocarcinoma (40.7%), and 57.4% of patients were stage IV. Most patients (94.4%) received combined chemotherapy, while 14.8% and 5.6% patients received radiotherapy or vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR) inhibitors, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study cohorts (metagenome and metabolome).

| Characteristic | Metagenome cohort (n = 54) |

Metabolome cohort (n = 49) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit group (n = 24) | Severe irAE group (n = 13) | Resistance group (n = 17) | P-value | ||

| Male (%) | 21 (87.5) | 10 (76.9) | 13 (76.5) | 0.61 | 36 (73.5) |

| Age (years) (mean ± standard deviation) | 64.92 ± 7.05 | 65.69 ± 8.33 | 61.41 ± 8.57 | 0.26 | 60.65 ± 9.69 |

| Pathological subtype | 0.27 | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma (%) | 9 (37.5) | 4 (30.8) | 9 (52.9) | 31 (63.3) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma (%) | 14 (58.3) | 7 (53.8) | 5 (29.4) | 18 (36.7) | |

| Others (%) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (15.4) | 3 (17.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| TNM stagea | 0.40 | ||||

| Stage II (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Stage III (%) | 12 (50.0) | 6 (46.2) | 5 (29.4) | 16 (32.7) | |

| Stage IV (%) | 12 (50.0) | 7 (53.8) | 12 (70.6) | 32 (65.3) | |

| Combined chemotherapy (%) | 24 (100.0) | 11 (84.6) | 16 (94.1) | 0.09 | 48 (98.0) |

| Combined radiotherapy (%) | 4 (16.7) | 1 (7.7) | 3 (17.6) | 0.79 | 10 (20.4) |

| Combined VEGFR inhibitors (%) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (5.9) | >0.999 | 2 (4.1) |

| Received ICI as neoadjuvant therapy (%) | 9 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 2 (11.8) | 0.15 | 3 (6.1) |

| Primary response to ICI treatment | 0.006 | ||||

| PR (%) | 15 (62.5) | 8 (61.5) | 3 (17.6) | 23 (46.9) | |

| SD (%) | 9 (37.5) | 5 (38.5) | 10 (58.8) | 26 (53.1) | |

| PD (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (23.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| IrAEs occurrence | |||||

| None (%) | 18 (75.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (64.7) | <0.001 | 37 (75.5) |

| Mono irAE (%) | 6 (25.0) | 8 (61.5) | 5 (29.4) | 11 (22.4) | |

| Multiple irAEs (%) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (38.5) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (2.0) | |

| Type of irAEb | |||||

| Skin toxicity (%) | 1 (4.2) | 5 (38.5) | 1 (5.9) | 0.02 | 4 (8.2) |

| Endocrine toxicity (%) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (7.7) | 4 (23.5) | 0.55 | 4 (8.2) |

| Gastrointestinal toxicity (%) | 1 (4.2) | 6 (46.2) | 2 (11.8) | 0.006 | 2 (4.1) |

| Cardiovascular toxicity (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (5.9) | 0.09 | 0 (0.0) |

| Pulmonary toxicity (%) | 1 (4.2) | 4 (30.8) | 1 (5.9) | 0.054 | 2 (4.1) |

| Hematological toxicity (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.24 | 1 (2.0) |

| Renal toxicity (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.24 | 0 (0.0) |

| Muscle toxicity (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.24 | 1 (2.0) |

| irAE highest severityb | |||||

| Grade 1 (%) | 4 (16.7) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | 0.46 | 3 (6.1) |

| Grade 2 (%) | 2 (8.3) | 5 (38.5) | 1 (5.9) | 0.04 | 5 (10.2) |

| Grade 3 (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (15.4) | 2 (11.8) | 0.11 | 3 (6.1) |

| Grade 4 (%) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (46.2) | 1 (5.9) | <0.001 | 1 (2.0) |

ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitors; irAE, immune-related adverse event; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

TNM staging is based on the 8th edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer, as published by the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC).

irAE classification and grading were performed according to the Management of immunotherapy-related toxicities from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN).

In terms of primary response, 48.1% and 44.4% of patients achieved partial response (PR) and stable disease (SD), respectively. During the entire follow-up period, 25 patients (46.3%) had at least one irAE, of whom six patients (11.1%) had more than one type of irAE. There were 36 irAE events in total: rashes (7/36), pulmonary toxicity (6/36), hypothyroidism (5/36), colitis (3/36), hepatitis (3/36), pancreatitis (3/36), cardiovascular toxicity (3/36), hyperthyroidism (2/36), hypophysitis (1/36), thrombocytopenia (1/36), renal toxicity (1/36), and muscle toxicity (1/36) (Table 1). The PFS, PFI, and OS were significantly different between the three groups (log-rank P < 0.0001); as expected, the benefit group had the longest survival, while the resistance group had the shortest. In the analysis, the grouping satisfied the PH assumption for OS, but not for PFS and PFI, for which time-dependent interaction terms were introduced into the models (Supplementary Fig. S2). The PFS rate at one year was also lower in the irAE group (69.2%) compared with the benefit group (100%) (P = 0.01), and the PFS rate (69.2%) was lower than the PFI rate (81.8%) due to two severe irAE-related deaths (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. S2).

In the metabolome cohort, sixty-two patients were considered for enrollment, and 49 patients were finally included in the metabolome analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1). The clinical characteristics were comparable to the metagenome cohort: 63.3% patients had adenocarcinoma, 36.7% had squamous cell carcinoma, and 65.3% of patients were stage IV. All patients achieved PR or SD as primary responses. Twelve patients (24.5%) had at least one irAE, of whom nine patients (18.4%) had ≥ grade 2 irAE. There were 14 irAE events in total: rashes (4/14), pulmonary toxicity (2/14), hypothyroidism (1/14), hepatitis (1/14), pancreatitis (1/14), diabetes (1/14), hyperthyroidism (1/14), thrombocytopenia (1/14), hypophysitis (1/14), and muscle toxicity (1/14) (Table 1).

Patients who benefit from ICIs have a different gut microorganism composition

We first compared the alpha diversity, which reflects the richness of microorganisms, between groups. The benefit group had higher Shannon and Simpson indices compared with the resistance group and lower indices compared with the severe irAE group, but the differences were not significant (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S3). PCoA plots by Bray–Curtis distance revealed a marginally significant difference in microorganism composition between the benefit and resistance groups (adonis P = 0.08) but no significant difference between the benefit group and the severe irAE group (adonis P = 0.91). Interestingly, the similarity in microbiota composition became more obvious in especially long-surviving patients benefitting long-term from ICIs (PFS ≥ 1000 days without surgery) (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, LEfSe analysis to determine differential taxa between the groups revealed a significantly higher abundance of butyrate-producing microbes in the benefit group, e.g., Faecalibacterium, Ruminococcus, Roseburia, and Anaerobutyricum at the genus level and F. prausnitzii, Blautia faecis, Anaerobutyricum hallii, Eubacterium ramulus, and Coprococcus catus at the species level (Fig. 1E and F, and Supplementary Fig. S4).

Co-occurrence networks reveal compact microbiota correlations in patients who benefit from ICIs

Filtering species present in ≤20% samples identified 241, 246, and 173 species in the benefit, severe irAE, and resistance groups, respectively, from which co-occurrence networks were constructed. The benefit group showed a more interconnected network (126 nodes and 191 edges) compared with the severe irAE group (99 nodes and 146 edges) and resistance group (94 nodes and 166 edges). The modularities of the three outcome groups were all >0.7, demonstrating the modular structure of all groups. The top four largest modules were labeled and accounted for 52.38%, 39.39%, and 53.19% of all nodes in the benefit, severe irAE, and resistance groups, respectively (Fig. 1G) Co-occurring species in these modules are summarized in Supplementary Data S3. Of note, butyrate-producing Intestinimonas butyriciproducens (679.85) and Dysosmobacter welbionis (373.11) showed the highest betweenness centralization in module #3 of the benefit group, possibly indicating the importance of these nodes. Furthermore, species in module #3 of the severe irAE group and module #4 of the resistance group were closely inter-connected but independent of the other modules. Alistipes shahii had the highest degree in the benefit group. The relationships among species differed between groups, with the benefit group showing the most unique microbial correlations (Fig. 1H).

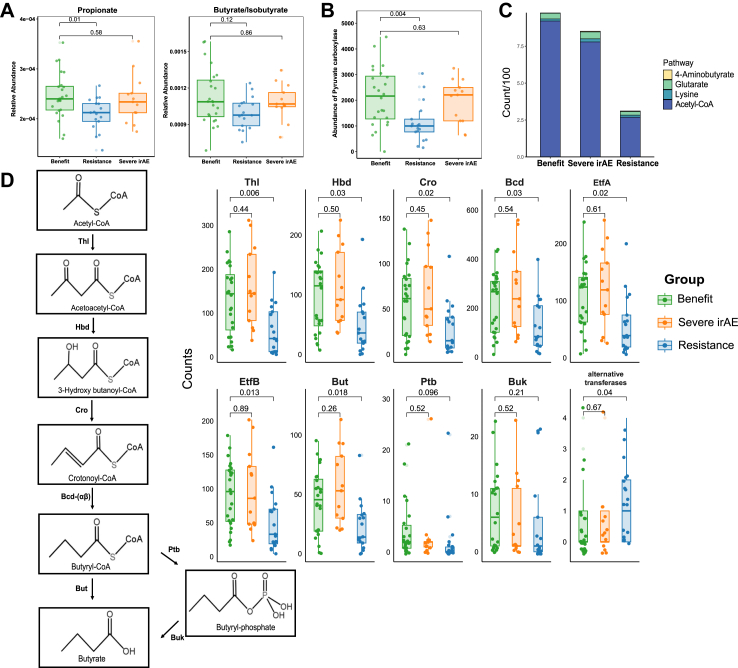

Butyrate/propionate-metabolizing pathways might play an important role in ICI efficacy

As microbiota can influence host function by producing metabolites, we next explored associated metabolic pathways. Of 79 predicted metabolites, the short chain fatty acid (SCFA) propionate was significantly enriched in the benefit group compared with the resistance group (P = 0.01), while there was a trend towards higher abundance of butyrate/isobutyrate in the benefit group compared with the resistance group (P = 0.12). No differences were observed between the benefit group and severe irAE group (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S5).

Fig. 2.

Predicted butyrate and butyrate-producing pathways in the benefit (n = 24), severe irAE (n = 13), and resistance (n = 17) groups. (A) Predicted propionate and butyrate/isobutyrate abundances (compared by Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini-Hochberg correction). (B) Abundance of pyruvate carboxylase (compared by Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini-Hochberg correction). (C) The enzyme counts of four butyrate-producing pathways (compared by Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini-Hochberg correction). (D) The enzyme counts of the acetyl-CoA butyrate-producing pathway (compared by Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini-Hochberg correction). Abbreviations: Thl, thiolase; Hbd, β-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase; Cro, crotonase; Bcd, butyryl-CoA dehydrogenase; EtfA and EtfB, electron transfer protein α, β subunits; But, butyryl-CoA:acetate CoA transferase; Ptb, phosphate butyryltransferase; Buk, butyrate kinase; irAE, immune-related adverse event.

We sought to validate our findings in external metagenome datasets. We first used an NSCLC cohort for validation,41 although it included various treatments not limited to immunotherapy, which showed significantly higher predicted propionate levels (P = 0.03) and higher butyrate/isobutyrate (P = 0.098) levels with marginal significance in responders (Supplementary Fig. S6A). Then, we validated our findings in the McCulloch cohort12 of immunotherapy in melanoma patients, which further confirmed significantly higher predicted propionate (P < 0.001) and butyrate/isobutyrate (P = 0.002) in responders than non-responders (Supplementary Fig. S6B).

To assess the propionate/butyrate-producing/consuming capacity in different groups, we further compared related metabolic enzymes. Pyruvate carboxylase, which is involved in the first step of the succinate pathway for propionate production,31 was significantly more abundant in the benefit group than in the resistance group (P = 0.004). However, other enzymes involved in propionate production and degradation were not significantly different between the three groups (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S7).

We further investigated the four main pathways that might be responsible for differences in butyrate abundance: acetyl-CoA, glutarate, 4-aminobutyrate, and lysine.28 Sequence counts of genes in the different pathways were compared. Only the acetyl-CoA pathway, the main butyrate-producing pathway, was significantly depleted in the resistance group compared with the benefit group (P = 0.02) (Fig. 2C). Further focusing on the acetyl-CoA pathway, we observed a universal increase in butyrate-producing enzymes in the benefit group compared with the resistance group, except for phosphate butyryltransferase (Ptb), butyrate kinase (Buk) and alternative transferases, which account for only a small proportion of the entire pathway (Fig. 2D). However, abundance of the butyrate-consuming genes acyl−CoA dehydrogenase and enoyl−CoA hydratase were not significantly different between the three groups (Supplementary Fig. S8).

Beneficial species had more compact co-occurrence correlations with butyrate-producing pathways

After filtering out species present in >20% samples and then selecting the top 200 species by average abundance, we identified differential species based on efficacy, which included 44 potentially beneficial species (i.e., overrepresented in patients with good efficacy), and 34 harmful species (i.e., species overrepresented in patients with poor efficacy) (Supplementary Data S4). Beneficial species included Akkermansia muciniphila, Bifidobacterium bifidum, two Roseburia species, and three Blautia species (Fig. 3A). LEfSe analysis also identified enrichment of Blautia species and A. hallii in responsive patients (Supplementary Fig. S9). We further explored correlations between beneficial species and butyrate-metabolizing genes and detected generally positive correlations between beneficial species and butyrate-producing enzymes. There were no similar correlations between beneficial species and butyrate-consuming enzymes nor between harmful species and butyrate-producing/consuming enzymes (Fig. 3B). Of note, for propionate, the harmful species Erysipelatoclostridium ramosum and Enterococcus faecalis were strongly positively correlated with propionate-consuming enzymes, which might suggest a harmful role for these species through propionate-derived toxic catabolites (Supplementary Fig. S10).32

Fig. 3.

Beneficial/harmful species in ICI efficacy groups and associations with butyrate-producing/consuming enzymes. (A) Heatmap and bubble plot of differential species in patients with good (n = 34) and poor (n = 20) ICI efficacy. (B) Correlation heatmap between species (beneficial and harmful) and butyrate-metabolizing (producing and consuming) genes.

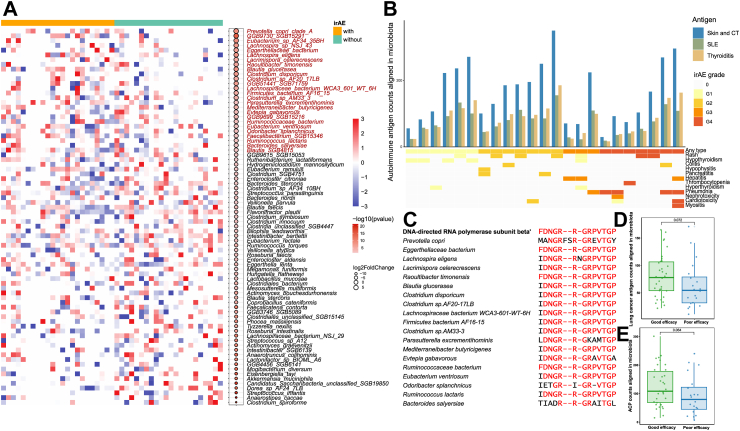

Autoimmune antigenic mimicry might contribute to irAEs

Given that the benefit and severe irAE groups possessed similar microbial compositions and butyrate/propionate-producing capacity, we hypothesized that specific species might determine irAE occurrence. Landmark analysis excluded patients receiving ICI treatment for less than one year without irAEs. After filtering out species present in >20% samples and selecting the top 200 species by average abundance, irAE (any grade) patients had a lower abundance of Roseburia faecis, Roseburia intestinalis, Bacteroides stercoris, Lactobacillus mucosae, and A. muciniphila (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the harmful species Prevotella copri was more abundant in irAE patients, and this organism has also been widely reported in association with autoimmune diseases.42 Both differential analyses revealed enrichment of Blautia glucerasea in irAE patients (Fig. 4A and Supplementary Fig. S11).

Fig. 4.

Molecular mimicry of autoimmune and lung cancer antigenic epitopes and ACP in gut microbiota. (A) Heatmap and bubble plot of differential species in patients with (n = 23) or without (n = 22) irAEs. (B) Aligned autoimmune antigen counts in microbiota of irAE patients. (C) Sequence alignment diagram of FDNGRRGRPVTGP with harmful species enriched in irAE patients. (D and E) Lung cancer antigen and ACP counts aligned in microbiota from patients with good (n = 34) and poor (n = 20) efficacy (compared by Wilcoxon rank sum tests). Abbreviations: ACP, anticancer peptides; CT, connective tissue; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; irAE, immune-related adverse event.

We next postulated that molecular mimicry of microbiota for autoantigens might contribute to irAE development. Consistent with our hypothesis, we identified numerous peptide mimics with autoimmunogenic potential within identical protein groups of P. copri and B. glucerasea genomes, as well as in other irAE-related species such as Streptococcus viridans12 and Bacteroides dorei.43 These mimics include antigenic epitopes associated with autoimmune diseases affecting the skin and connective tissue (CT), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), autoimmune thyroiditis, Graves’ disease, and ulcerative colitis (UC) (Supplementary Data S5). Furthermore, antigenic epitopes associated with several autoimmune diseases aligned with gut microbiota sequences in irAE patients, especially for SLE, autoimmune diseases of the skin/CT, and autoimmune thyroiditis (Fig. 4B). However, total epitope counts were not significantly different between patients with and without irAEs (P = 0.62), nor were there trends between aligned autoantigen counts and higher irAE grade (Supplementary Fig. S12A and B), possibly due to the clinical heterogeneity of irAEs in different organs. We therefore examined specific epitopes for specific irAEs and found that total SLE-related epitope counts were significantly higher in patients with immune-related colitis (P = 0.04), especially FDNGRRGRPVTGP (P = 0.02) and IDNGRRGRPITGP (P = 0.02). Interestingly, the encoded protein sequences from harmful microbes reported above generally aligned with these autoantigenic epitopes (Fig. 4C and Supplementary Fig. S13).

Tumor antigen/anticancer peptide mimicry might enhance ICI efficacy

Similarly, we hypothesized that there exists molecular mimicry of microbiota for tumor antigens that contributes to immune system recognition of the tumor, thereby enhancing ICI efficacy. As expected, there was a trend towards greater abundance of lung cancer-related antigen counts in patients with good ICI efficacy compared with those with poor ICI efficacy (P = 0.07) (Fig. 4D). Patients with good efficacy also had more anticancer peptide (ACP) counts aligned in microbiota (P = 0.06) (Fig. 4E). Further focusing on specific sequences, three lung cancer-related antigens and four ACPs were significantly higher in good efficacy patients (Table 2). Comparing lung cancer antigens and ACP sequences, only one aligned sequence GVGSPYVSRLLG appeared in both databases. The sequences identified only in the lung cancer antigen database might therefore also act as ACPs, especially in lung cancer patients receiving ICIs.

Table 2.

Lung cancer-related antigens and ACPs represented in good efficacy patients.

| Lung cancer antigen | P-valuea | ACP | P-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| NPTNTVFDAKRLIGRR | 0.02 | ALWKDILKNVGKAAGKAVLNTVTDMVNQ | 0.014 |

| TCEFYMAYADYHDFMEITEK | 0.037 | MPKWKVFKKIEKVGRNIRNGIVKAGPAIAVLGEAKALG | 0.027 |

| ANGILNVSAVDKSTGKE | 0.043 | LPKWKVFKKIEKVGRNIRNGIVKAGPAIAVLGEAKALG | 0.043 |

| ACDCRGDCFCGGGGIVRRADRAAVP | 0.022 |

ACP, anticacer peptides.

P-values were calculated by Wilcoxon rank sum tests between good (n = 34) and poor (n = 20) efficacy patients.

We further conducted validation analyses in the Routy cohort,6 which included NSCLC patients receiving anti-PD-1 therapy. Responders exhibited a higher abundance of lung cancer-related antigen counts compared with non-responders (P = 0.02). However, no similar trend was observed for ACP counts in microbiota (P = 0.98) (Supplementary Fig. S14).

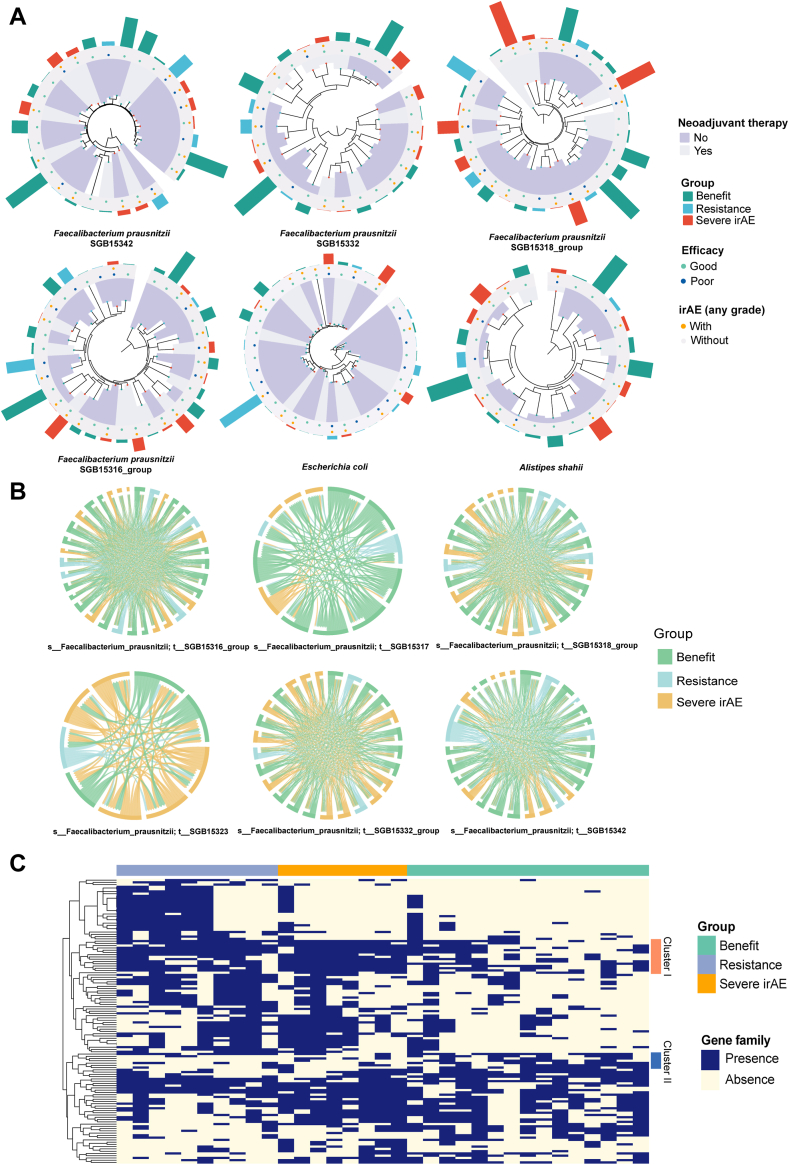

Genomic variations of specific strains might play a role in different clinical phenotypes

Previous studies have reported contradictory effects for specific species (e.g., F. prausnitzii) in ICI efficacy44,45 and immune-related colitis.44,46 Besides heterogeneity across different clinical cohorts, strain-level variations might also play a role in different clinical phenotypes. Supporting this, strain variability of E. coli has been studied in inflammatory bowel disease patients.47 The role of A. shahii has also been investigated, since it was highly related to other species in the benefit group.

Six SGBs of F. prausnitzii were variably distributed across samples of different groups, with only the SGB15316_group significantly higher in the benefit group compared with the resistance group (P = 0.049). No significant differences were observed for SGBs of E. coli and A. shahii (Supplementary Fig. S15). The phylogenetic structures of SGBs for these three species were constructed. Disregarding abundance, a noticeable centralized trend emerged where similar clinical phenotypes clustered within the genetic lineages of each species (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Fig. S16). Specially, E. coli and SGB15342 of F. prausnitzii showed significant evolutionary variation among patients with different ICI outcomes, for both efficacy (E. coli, Pagel’s λ = 1.28, P = 0.001; SGB15342 of F. prausnitzii, Pagel’s λ = 1.89, P = 0.001) and irAEs (E. coli, Pagel’s λ = 2.10, P = 0.001; SGB15342 of F. prausnitzii, Pagel’s λ = 1.83, P = 0.001). We next investigated SNPs in these SGBs between different patients, and the benefit group contained the largest proportion of patients with F. prausnitzii SGB15317 and SGB15342, while those with a tendency to develop severe irAEs had a high prevalence of F. prausnitzii SGB15323 and SGB15332_group (Fig. 5B and Supplementary Fig. S17). For all three species, there existed high mutation rates between the different clinical groups, indicating that strain variation might influence the effect of specific species on ICI outcomes.

Fig. 5.

Strain-level analyses of Escherichia coli, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Alistipes shahii. (A) Phylogenetic trees of Escherichia coli, SGBs of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, and Alistipes shahii species with different clinical phenotypes and groups. (B) Chord diagrams of 6 SGBs of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii within the three groups. (C) Heatmap of Escherichia coli gene families within the three groups. Abbreviations: SGB, species-level genome bins; irAE, immune-related adverse event.

Finally, we sought to explore which genes were responsible for the differences. Heatmap clustering for E. coli showed clearest discrimination of beneficial and harmful strains (Fig. 5C), with a cluster of harmful gene families absent in most patients in the benefit group but mainly present in the resistance and severe irAE group (cluster I), including gene families involved in the toxin-antitoxin system [ghoS], stress response [cadC, rclC, ykgR and ycgZ], cell cycle [cedA and ymgF], cyanate transport and metabolic process [cynS and cynX], together with several genes [yeeS, ybjO, insl1, etc.] that might be beneficial (cluster II) (Supplementary Data S6). For F. prausnitzii, we classified gene families into four clusters, and F. prausnitzii absent for genes in clusters I and II but present in clusters III and IV was likely to be a beneficial strain in ICI patients (Supplementary Fig. S18). The gene families in each cluster are listed in Supplementary Data S7.

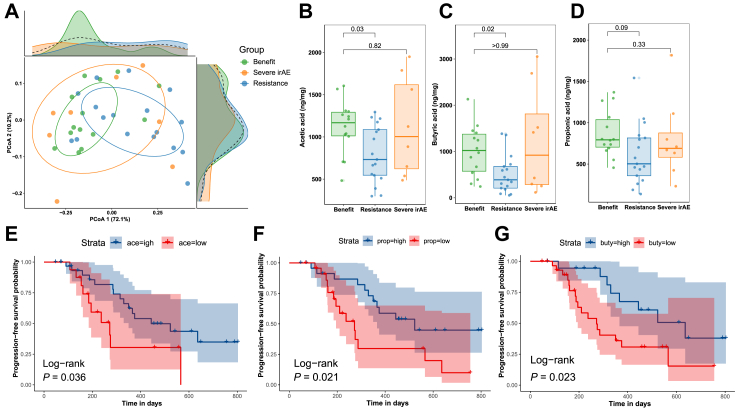

Gut metabolome analysis reveals that baseline SCFA concentrations might predict long-term survival on ICIs

To validate metagenome-predicted metabolites, 49 patients were subjected to metabolome analysis, among whom 14 patients were in the benefit group, eight were in the severe irAE group, and 17 were in the resistance group (ten were lost to one-year follow-up and are only included in survival analyses). Unsurprisingly, a PCoA plot revealed significantly different SCFA composition between the benefit and resistance groups (adonis P = 0.02) (Fig. 6A). Comparisons of eleven SCFAs revealed that acetic acid (P = 0.03) and butyric acid (P = 0.02) were significantly more abundant in the benefit group compared with the resistance group (Fig. 6B–C). A similar trend was observed for propionic acid (P = 0.09) (Fig. 6D), though it was not statistically significant. No differences were observed for the other eight SCFAs (Supplementary Fig. S19). Furthermore, PFS was significantly longer in patients with highly abundant acetic acid (>700 ng/mg), propionic acid (>670 ng/mg), and butyric acid (>800 ng/mg) (log-rank P < 0.05) (Fig. 6E–G). Even after adjusting for histopathological subtype and stage, the risk of tumor progression was still higher in patients with a lower abundance of acetic acid (HR = 2.98, 95% CI: 1.21–7.35, P = 0.02), propionic acid (HR = 2.93, 95% CI: 1.26–6.79, P = 0.01), and butyric acid (HR = 2.51, 95% CI: 1.05–5.99, P = 0.04). The abundance of these metabolites, along with covariates histopathological subtype and stage, all satisfied PH assumption (Supplementary Fig. S20).

Fig. 6.

Metabolome analyses of eleven SCFAs in the validation cohort. (A) Principal co-ordinates analysis (PCoA) plot by benefit (n = 14), severe irAE (n = 8), and resistance (n = 17) groups (compared by adonis function with 999 permutations and Benjamini-Hochberg correction). (B–D) Acetate, propionate, and butyrate abundances (compared by Wilcoxon rank sum tests with Benjamini-Hochberg correction). (E–G) Kaplan–Meier survival curves for PFS of patients with higher or lower acetate/propionate/butyrate. Abbreviations: SCFA, short chain fatty acids; irAE, immune-related adverse event.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the baseline gut microbial characteristics in advanced lung cancer patients deriving long-term benefit from ICIs. The baseline microbial composition in patients benefitting from ICIs was different to those showing resistance but not to those developing severe irAEs. Similarities in microbiota composition were even more pronounced in long-surviving patients. Patients in the benefit group had the most interconnected and complex microbial network and were enriched for the SCFAs propionate and butyrate/isobutyrate, while the acetyl-CoA pathway accounted for the largest difference in butyrate-producing capacity with a universal increase in butyrate-producing enzymes. Beneficial species were more positively correlated with butyrate-producing enzymes but not butyrate-consuming enzymes, and some harmful species were correlated with propionate-consuming enzymes. The microbial signature of irAE patients might harbor autoimmune-related species, e.g., P. copri, and total counts of SLE-related epitopes were significantly more enriched in patients with immune-related colitis. Likewise, patients showing good ICI efficacy had more abundant lung cancer-related antigens aligned in microbiota. Genomic variations in E. coli and F. prausnitzii centralized around different clinical phenotypes. Finally, metabolome validation revealed that patients with higher acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid levels had a better prognosis and lower risk of tumor progression.

The baseline microbiota composition of the benefit and severe irAE groups was similar and distinct from the resistance group, consistent with the reported positive association between the development of irAEs and efficacy.48 This is perhaps unsurprising, as these two processes can be regarded as two sides of the same coin, where overactivation of the immune system targets both tumor and normal tissues. Focusing on the longest surviving patients with a PFS ≥1000 days without undergoing surgery, there was a pronounced increase in compositional similarity of baseline gut microbiota within this population. Furthermore, co-occurrence network analyses revealed that the benefit group had the most compact microbiota correlation. The microbiota of patients deriving long-term benefit from ICIs might undergo coevolution and develop a specific beneficial microbiota structure with favorable characteristics.

To better understand this beneficial microbiota structure, we identified the microbiota characteristics of patients benefitting long-term from ICIs at different taxonomic levels. Remarkably, LEfSe analyses revealed abundant enrichment of butyrate-producing species in the benefit group, including F. prausnitzii,49 B. faecis,50 A. hallii,49 E. ramulus,49 and C. catus.51 Furthermore, the co-occurrence network for the benefit group showed a microbial module centered on butyrate-producing I. butyriciproducens and D. welbionis, prompting further consideration of the underlying metabolite production.

SCFAs such as acetate, propionate, and butyrate are abundant microbial metabolites mainly produced by microbial fermentation and reported to regulate adaptive immunity and inhibit tumor progression.52,53 Butyrate has been shown to enhance anti-tumor efficacy in mice receiving combined oxaliplatin and anti-PD-1 therapy by promoting IL-12 signaling and activating CD8+ T cell cytotoxic immune responses on an ID2-dependent manner.54 Two observational gut metabolomics profiling studies in cancer patients receiving anti-PD-1 treatment showed that higher SCFA concentrations were associated with responses and long-term benefits from ICIs.55,56 We also found that predicted levels of microbiota-derived propionate and butyrate/isobutyrate were significantly higher in the benefit group than in the resistance group, and the beneficial impacts of these metabolites and also acetate were validated in metabolome analyses, prompting us to further explore the specific metabolizing pathways and enzymes active in each group. Enzymes in the butyrate-producing acetyl-CoA pathway and pyruvate carboxylase of the propionate-producing succinate pathway were significantly depleted in the resistance group compared with the benefit group. However, there were no differences between groups for propionate/butyrate-consuming pathways. Furthermore, we found that species favoring efficacy had significantly more positive correlations with butyrate-producing enzymes. These results support existing data that SCFAs, especially butyrate, promote ICI efficacy, although other studies have failed to detect this association; one study reported that SCFAs, including butyrate, inhibited anti-CTLA-4-induced CD86/CD80 expression and impaired antitumor activity.57 These inconsistencies may be due to the different ICI types studied and heterogeneous tumor backgrounds.

With respect to irAEs, abundances of acetic acid, propionic acid, and butyric acid were also lower in patients developing severe irAEs compared with those benefitting from ICIs, although this association did not reach statistical significance. In our previous study using 16S rDNA amplicon sequencing, we also found decreased abundance of butyrate-producing genera in patients with irAEs, especially in those with colitic irAE.11

Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain the development of irAEs, but there has yet to be a consensus. Vétizou et al. reported gut microbiota-dependent induction of subclinical colitis after anti-CTLA-4 treatment in mice.58 We previously showed that fulminant immune-related colitis was only induced after FMT from irAE patients (but not those without irAEs) to antibiotic-treated mice.11 Thus, there appear to be pathogenic factors in the gut microbiota of irAE patients that are not explained by beneficial microbiota-derived metabolites such as butyrate. The gut microbiota may influence autoimmune diseases, including irAEs, by molecular mimicry,59 which describes cross-reactivity between microbial and autoimmune antigens. Dougan et al. proposed that ICIs reactivate tissue-resident T cells specific for microbial antigens and trigger downstream autoimmune toxicity and inflammatory cytokine signaling, leading to irAE development,60 but to our best knowledge there is no direct empirical evidence to support this hypothesis. In this study, we provide the first preliminary evidence that molecular mimicry drives irAEs. We found that the severe irAE group had the highest alpha diversity, indicating the most abundant microbial antigens. We also detected a series of irAE-related species in this group, especially P. copri, which has widely been reported in association with autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes.42 It is therefore possible that overlap of the microbial genome with abundant autoimmune antigenic epitopes might play a role in irAE development. Interestingly, our organ-specific comparisons further revealed that SLE-related epitopes (but not UC-related epitopes) were significantly more abundant in colitic irAE patients. Combined with previous findings that the endoscopic and histologic characteristics of immune-related colitis and UC are different,61 it is rational to infer that these two diseases have different underlying autoimmune targets despite the similar clinical characteristics. Furthermore, these epitopes also showed universal overlap with irAE-related species, further supporting the molecular mimicry hypothesis.

Molecular mimicry might also play a role in enhancing ICI efficacy through cross-reactivity between microbial and tumor antigens. Snyder et al. performed whole-exome sequencing of melanomas from patients treated with anti-CTLA-4 and identified tumor neoantigenic peptides that were homologous with microbial epitopes, and, furthermore, these were predictive of better clinical outcomes.62 Furthermore, T cell clones recognizing naturally processed tumor antigens were cross-reactive with microbial peptides in melanoma patients.63 In NSCLC patients, a peptide overexpressed in tumors could activate cross-reactivity with Epstein–Barr virus and E. coli.64 However, these studies were all conducted from the perspective of tumor antigens and indicated that the tumor antigens could somehow mimic microbial antigens and activate cross-immunity. Our analysis of the gut microbiota is the first to show that microbiota can mimic tumor antigens and that this phenomenon predicts ICI responses.

There have been several studies of associations between the gut microbiota and ICI efficacy in different clinical cohorts and tumors, but there has been little consensus on specific microbial associations.65 A. muciniphila, R. intestinalis, and B. bifidum are all generally acknowledged to benefit patients receiving ICIs, consistent with our findings.41,66,67 We also found that A. muciniphila was not only beneficial in terms of efficacy but also protected against irAEs. Unlike the universal beneficial role reported for A. muciniphila, many species have been reported to have variable effects, such as for F. prausnitzii for ICI efficacy44,45 and irAE occurrence.44,46 We also explored another possible mechanism, namely genomic variations in the same species, which was further validated by phylogenetic analyses of F. prausnitzii and E. coli. Our findings suggest that strain-level variation is important in this context. Furthermore, we revealed a series of potential harmful E. coli gene families for ICI patients, including genes related to toxin-antitoxin systems, stress responses, the cell cycle, cyanate transport, and metabolic processes.

FMT from responders to patients with PD-1-refractory melanoma could overcome resistance in some cases, though with unstable clinical benefit.7 Our findings pave the way for the concept of “smart” FMT – that is, defining a specific bacterial formulation to administer to cancer patients receiving ICIs containing species with favorable strain dynamics, SCFA production, and mimicking the tumor but not autoimmune antigens.

One of the main strengths of our study was that landmark analysis was performed based on long-term prognosis, rather than the initial effects of ICIs over the first several months, as in most other studies.4,6 The median follow-up time of up to 3 years as well as the novel grouping approach combining efficacy and irAEs enabled us to identify patient subgroups who truly benefit long-term from ICIs. Furthermore, we not only identified baseline gut microbiota characteristics but also further explored the underlying mechanisms with respect to metabolite production, molecular mimicry, and strain-level genomic variations. However, our study also had some limitations. As all samples were collected before commencement of ICIs to establish the predictive value of microbiota, the sample size was relatively small due to strict data quality control and the requirement for long-term follow-up. Our antigen sequence alignment analysis relied on known autoantigens cataloged in public databases, so some crucial, as yet uncharacterized antigenic epitopes for irAEs may not have been identified. Finally, strain-level analyses were not performed for some species due to their limited abundance.

In conclusion, patients achieving long-term benefit from ICIs had converging gut microbiota characteristics that co-evolved as a compact microbial community with high butyrate-producing ability. Microbial production of SCFAs was especially beneficial for anti-tumor efficacy. We provide preliminary evidence that molecular mimicry of autoimmune and tumor antigens with microbial antigens might contribute to irAE development and ICI efficacy, respectively, and genomic variations of the same microbial species may also play a role in dictating different clinical phenotypes. These mechanisms now need further, in-depth exploration.

Contributors

Conceptualization, XL, BT, and JL; methodology, XL, BT, and JL; investigation, XL, HT, BL, XJ, XG, QZ, and YZ; visualization, XL; supervision, BT, JL, MC, YX, and MW; writing—original draft, XL; writing—review & editing, all authors. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. XL, BT, and JL have accessed and verified the underlying data. BT and JL were responsible for the decision to submit the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

Raw metagenomic sequences are available in the SRA under the Bioproject accession PRJNA1154401.

Declaration of interests

Authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7232110), National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (2022-PUMCH-A-072, 2023-PUMCH-C-054), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS) (2022-I2M-C&T-B-010). All samples were stored and managed by the Clinical Biobank, Medical Research Center, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences. The research analysis was conducted on the high-performance computing platform of Peking Union Medical College Hospital.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2024.105427.

Contributor Information

Bei Tan, Email: tanbei0626@aliyun.com.

Jingnan Li, Email: lijn2008@126.com.

Appendix ASupplementary data

References

- 1.Hargadon K.M., Johnson C.E., Williams C.J. Immune checkpoint blockade therapy for cancer: an overview of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors. Int Immunopharmacol. 2018;62:29–39. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumeister S.H., Freeman G.J., Dranoff G., Sharpe A.H. Coinhibitory pathways in immunotherapy for cancer. Annu Rev Immunol. 2016;34:539–573. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gopalakrishnan V., Spencer C.N., Nezi L., et al. Gut microbiome modulates response to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359(6371):97–103. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matson V., Fessler J., Bao R., et al. The commensal microbiome is associated with anti-PD-1 efficacy in metastatic melanoma patients. Science. 2018;359(6371):104–108. doi: 10.1126/science.aao3290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Routy B., Le Chatelier E., Derosa L., et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1-based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science. 2018;359(6371):91–97. doi: 10.1126/science.aan3706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davar D., Dzutsev A.K., McCulloch J.A., et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science. 2021;371(6529):595–602. doi: 10.1126/science.abf3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baruch E.N., Youngster I., Ben-Betzalel G., et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science. 2021;371(6529):602–609. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dizman N., Meza L., Bergerot P., et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab with or without live bacterial supplementation in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomized phase 1 trial. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):704–712. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01694-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Routy B., Lenehan J.G., Miller W.H., Jr., et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation plus anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in advanced melanoma: a phase I trial. Nat Med. 2023;29(8):2121–2132. doi: 10.1038/s41591-023-02453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X., Tang H., Zhou Q., et al. Gut microbiota composition in patients with advanced malignancies experiencing immune-related adverse events. Front Immunol. 2023;14 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1109281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCulloch J.A., Davar D., Rodrigues R.R., et al. Intestinal microbiota signatures of clinical response and immune-related adverse events in melanoma patients treated with anti-PD-1. Nat Med. 2022;28(3):545–556. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01698-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gandhi L., Rodríguez-Abreu D., Gadgeel S., et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy in metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(22):2078–2092. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstraw P., Chansky K., Crowley J., et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (eighth) edition of the TNM classification for lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J., et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson J.A., Schneider B.J., Brahmer J. 2024. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: management of immunotherapy-related toxicities version 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langmead B., Salzberg S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li D., Liu C.M., Luo R., Sadakane K., Lam T.W. MEGAHIT: an ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(10):1674–1676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu W., Lomsadze A., Borodovsky M. Ab initio gene identification in metagenomic sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(12) doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li W., Godzik A. Cd-hit: a fast program for clustering and comparing large sets of protein or nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(13):1658–1659. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beghini F., McIver L.J., Blanco-Míguez A., et al. Integrating taxonomic, functional, and strain-level profiling of diverse microbial communities with bioBakery 3. Elife. 2021;10 doi: 10.7554/eLife.65088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Segata N., Izard J., Waldron L., et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchfink B., Xie C., Huson D.H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12(1):59–60. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15(12):550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calgaro M., Romualdi C., Waldron L., Risso D., Vitulo N. Assessment of statistical methods from single cell, bulk RNA-seq, and metagenomics applied to microbiome data. Genome Biol. 2020;21(1):191. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02104-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bastian M., Heymann S., Jacomy M. Proceedings of the third international conference on weblogs and social media, ICWSM 2009, san jose, California, USA, may 17-20, 2009. 2009. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mallick H., Franzosa E.A., McLver L.J., et al. Predictive metabolomic profiling of microbial communities using amplicon or metagenomic sequences. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3136. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10927-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vital M., Howe A.C., Tiedje J.M. Revealing the bacterial butyrate synthesis pathways by analyzing (meta)genomic data. mBio. 2014;5(2) doi: 10.1128/mBio.00889-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He J., Chu Y., Li J., et al. Intestinal butyrate-metabolizing species contribute to autoantibody production and bone erosion in rheumatoid arthritis. Sci Adv. 2022;8(6) doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abm1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hosseini E., Grootaert C., Verstraete W., Van de Wiele T. Propionate as a health-promoting microbial metabolite in the human gut. Nutr Rev. 2011;69(5):245–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dolan S.K., Wijaya A., Geddis S.M., Spring D.R., Silva-Rocha R., Welch M. Loving the poison: the methylcitrate cycle and bacterial pathogenesis. Microbiology (Reading) 2018;164(3):251–259. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haratani K., Hayashi H., Chiba Y., et al. Association of immune-related adverse events with nivolumab efficacy in non-small-cell lung cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(3):374–378. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robert C., Hwu W.J., Hamid O., et al. Long-term safety of pembrolizumab monotherapy and relationship with clinical outcome: a landmark analysis in patients with advanced melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2021;144:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nara K., Taguchi S., Buti S., et al. Associations of concomitant medications with immune-related adverse events and survival in advanced cancers treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a comprehensive pan-cancer analysis. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12(3) doi: 10.1136/jitc-2024-008806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tyagi A., Tuknait A., Anand P., et al. CancerPPD: a database of anticancer peptides and proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D837–D843. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scholz M., Ward D.V., Pasolli E., et al. Strain-level microbial epidemiology and population genomics from shotgun metagenomics. Nat Methods. 2016;13(5):435–438. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Truong D.T., Tett A., Pasolli E., Huttenhower C., Segata N. Microbial strain-level population structure and genetic diversity from metagenomes. Genome Res. 2017;27(4):626–638. doi: 10.1101/gr.216242.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xie J., Chen Y., Cai G., Cai R., Hu Z., Wang H. Tree Visualization by One Table (tvBOT): a web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(W1):W587–W592. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pagel M. Inferring the historical patterns of biological evolution. Nature. 1999;401(6756):877–884. doi: 10.1038/44766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee S.H., Cho S.Y., Yoon Y., et al. Bifidobacterium bifidum strains synergize with immune checkpoint inhibitors to reduce tumour burden in mice. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6(3):277–288. doi: 10.1038/s41564-020-00831-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abdelsalam N.A., Hegazy S.M., Aziz R.K. The curious case of Prevotella copri. Gut Microb. 2023;15(2) doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2249152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Usyk M., Pandey A., Hayes R.B., et al. Bacteroides vulgatus and Bacteroides dorei predict immune-related adverse events in immune checkpoint blockade treatment of metastatic melanoma. Genome Med. 2021;13(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00974-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chaput N., Lepage P., Coutzac C., et al. Baseline gut microbiota predicts clinical response and colitis in metastatic melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(6):1368–1379. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pietrzak B., Tomela K., Olejnik-Schmidt A., et al. A clinical outcome of the anti-PD-1 therapy of melanoma in polish patients is mediated by population-specific gut microbiome composition. Cancers. 2022;14(21) doi: 10.3390/cancers14215369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao Y., Xu P., Sun D., et al. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii abrogates intestinal toxicity and promotes tumor immunity to increase the efficacy of dual CTLA4 and PD-1 checkpoint blockade. Cancer Res. 2023;83(22):3710–3725. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-23-0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dubinsky V., Reshef L., Rabinowitz K., Wasserberg N., Dotan I., Gophna U. Escherichia coli strains from patients with inflammatory bowel diseases have disease-specific genomic adaptations. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(10):1584–1597. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hussaini S., Chehade R., Boldt R.G., et al. Association between immune-related side effects and efficacy and benefit of immune checkpoint inhibitors - a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev. 2021;92 doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2020.102134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Louis P., Duncan S.H., McCrae S.I., Millar J., Jackson M.S., Flint H.J. Restricted distribution of the butyrate kinase pathway among butyrate-producing bacteria from the human colon. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(7):2099–2106. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.7.2099-2106.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahashi K., Nishida A., Fujimoto T., et al. Reduced abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria species in the fecal microbial community in crohn’s disease. Digestion. 2016;93(1):59–65. doi: 10.1159/000441768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Louis P., Flint H.J. Diversity, metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;294(1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01514.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yao Y., Cai X., Fei W., Ye Y., Zhao M., Zheng C. The role of short-chain fatty acids in immunity, inflammation and metabolism. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2022;62(1):1–12. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1854675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Miller K.D., O’Connor S., Pniewski K.A., et al. Acetate acts as a metabolic immunomodulator by bolstering T-cell effector function and potentiating antitumor immunity in breast cancer. Nat Cancer. 2023;4(10):1491–1507. doi: 10.1038/s43018-023-00636-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.He Y., Fu L., Li Y., et al. Gut microbial metabolites facilitate anticancer therapy efficacy by modulating cytotoxic CD8(+) T cell immunity. Cell Metab. 2021;33(5):988–1000.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nomura M., Nagatomo R., Doi K., et al. Association of short-chain fatty acids in the gut microbiome with clinical response to treatment with nivolumab or pembrolizumab in patients with solid cancer tumors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.2895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Botticelli A., Vernocchi P., Marini F., et al. Gut metabolomics profiling of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients under immunotherapy treatment. J Transl Med. 2020;18(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s12967-020-02231-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Coutzac C., Jouniaux J.M., Paci A., et al. Systemic short chain fatty acids limit antitumor effect of CTLA-4 blockade in hosts with cancer. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):2168. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16079-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vétizou M., Pitt J.M., Daillère R., et al. Anticancer immunotherapy by CTLA-4 blockade relies on the gut microbiota. Science. 2015;350(6264):1079–1084. doi: 10.1126/science.aad1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang X., Chen B.D., Zhao L.D., Li H. The gut microbiota: emerging evidence in autoimmune diseases. Trends Mol Med. 2020;26(9):862–873. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dougan M., Luoma A.M., Dougan S.K., Wucherpfennig K.W. Understanding and treating the inflammatory adverse events of cancer immunotherapy. Cell. 2021;184(6):1575–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang Y., Abu-Sbeih H., Mao E., et al. Endoscopic and histologic features of immune checkpoint inhibitor-related colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24(8):1695–1705. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Snyder A., Makarov V., Merghoub T., et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(23):2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fluckiger A., Daillère R., Sassi M., et al. Cross-reactivity between tumor MHC class I-restricted antigens and an enterococcal bacteriophage. Science. 2020;369(6506):936–942. doi: 10.1126/science.aax0701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chiou S.H., Tseng D., Reuben A., et al. Global analysis of shared T cell specificities in human non-small cell lung cancer enables HLA inference and antigen discovery. Immunity. 2021;54(3):586–602.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lee K.A., Thomas A.M., Bolte L.A., et al. Cross-cohort gut microbiome associations with immune checkpoint inhibitor response in advanced melanoma. Nat Med. 2022;28(3):535–544. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01695-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Derosa L., Routy B., Thomas A.M., et al. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2022;28(2):315–324. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01655-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kang X., Liu C., Ding Y., et al. Roseburia intestinalis generated butyrate boosts anti-PD-1 efficacy in colorectal cancer by activating cytotoxic CD8(+) T cells. Gut. 2023;72(11):2112–2122. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2023-330291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.