Abstract

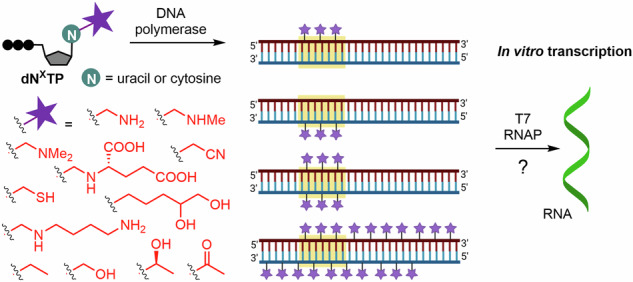

DNA modifications on pyrimidine nucleobases play diverse roles in biology such as protection of bacteriophage DNA from enzymatic cleavage, however, their role in the regulation of transcription is underexplored. We have designed and synthesized a series of uracil 2ʹ-deoxyribonucleosides and 5ʹ-O-triphosphates (dNTPs) bearing diverse modifications at position 5 of nucleobase, including natural nucleotides occurring in bacteriophages, α-putrescinylthymine, α-glutaminylthymine, 5-dihydroxypentyluracil, and methylated or non-methylated 5-aminomethyluracil, and non-natural 5-sulfanylmethyl- and 5-cyanomethyluracil. The dNTPs bearing basic substituents were moderate to poor substrates for DNA polymerases, but still useful in primer extension synthesis of modified DNA. Together with previously reported epigenetic pyrimidine nucleotides, they were used for the synthesis of diverse DNA templates containing a T7 promoter modified in the sense, antisense or in both strands. A systematic study of the in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase showed a moderate positive effect of most of the uracil modifications in the non-template strand and some either positive or negative influence of modifications in the template strand. The most interesting modification was the non-natural 5-cyanomethyluracil which showed significant positive effect in transcription.

Subject terms: DNA, Nucleic acids, Natural product synthesis

DNA modifications on pyrimidine nucleobases play diverse roles in biology such as protection of bacteriophage DNA from enzymatic cleavage, however, their role in the regulation of transcription is underexplored. Here, the authors design and synthesize a series of 5-substituted pyrimidine 2ʹ-deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates and employ them for the synthesis of diverse DNA templates, showing their regulation on in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase.

Introduction

Modified pyrimidine nucleobases play diverse roles in biology. 5-Methylcytosine (5mC)1 is an important epigenetic modification in most eukaryotic genomes typically downregulating transcription. Its oxidized congeners2,3, i.e., 5-hydroxymethylcytosine (5hmC)4,5, 5-formylcytosine (5fC)6 and 5-carboxycytosine (5caC)7, that are formed through oxidation of 5mC by ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes8,9 are intermediates in active demethylation10–12 but also can play a role in regulation of transcription13–15. On the other hand, 5-hydroxymethyluracil (5hmU) is a very rare natural DNA modification occurring in human stem cells16, cancer cells17, or protozoan parasites18, yet its biological role is not fully understood19. Most interestingly, in several bacteriophages 5hmU almost completely replaces thymine20,21 and some bacteriophages even contain hypermodified pyrimidine bases20,22, e.g., α-putrescinylthymine23,24, α-glutaminylthymine25, 5-dihydroxypentyluracil26,27, 5-aminomethyl- and 5-aminoethyluracil22, as well as glucosylated hydroxymethylcytosine28,29. Other interesting pyrimidine modifications have been observed in other organisms, e.g., base J in kinetoplastid protozoa30–32 and 5-glycerylmethylcytosine in alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii33,34. Interestingly, 5-cyanomethyluridine was found as a modification in tRNA of Haloferax Volcanii35. There have been many studies on biosynthesis36 of these hypermodified nucleotides and on their role in protection of virus DNA from cleavage by bacterial restriction endonucleases (REs)37,38, but their role in regulation of transcription39 is yet underexplored20.

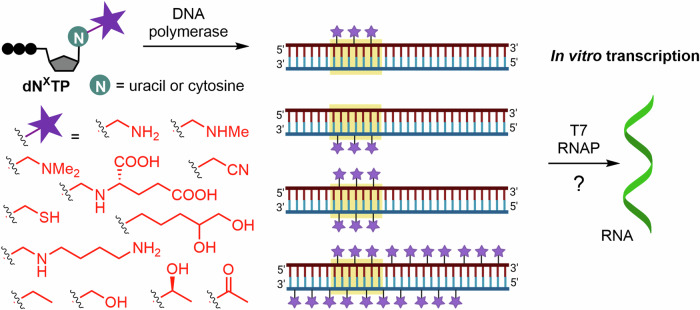

We have studied the influence of natural and non-natural nucleobase modifications on cleavage of DNA by REs and found40,41 that some smaller modifications (i.e., hydroxymethyl or ethynyl) are often tolerated by RE that can still recognize and cleave the target DNA sequences and we have even shown proof-of-concept transient protection of DNA from RE cleavage42,43. We have also systematically studied the role of nucleobase modifications in regulation of transcription with bacterial RNA polymerase (RNAP) from E. coli and B. subtilis and found44 that bulkier modifications typically completely inhibit transcription through blocking of the interaction of the RNAP and transcription factors with promoter sequences of the DNA. On the other hand, some small modifications, i.e., 7-deazapurines or 5-ethynyluracil are tolerated and allow transcription44, whereas 5-hydroxymethyluracil45, 5-hydroxymethylcytosine45 or 5-ethyluracil46 are not only tolerated but, surprisingly, they even significantly enhance transcription with E. coli RNAP. Also, some non-natural oxidized forms of 5-ethyl and 5-propylpyrimidines were tolerated and allowed transcription46. 5-Glucosyl-hmC was found to protect the DNA from RE cleavage but still gave transcription47. Photocaged 5hmU was used for switching transcription through photochemical release of 5hmU (triggering the transcription on) and phosphorylation by bacterial 5hmU DNA kinase (5HMUDK) that switched the transcription off again48. These findings suggest that the presence of 5hmU gives the bacteriophage DNA advantage in transcription, the enzymatic phosphorylation can be the bacterial response inactivating the viral DNA, while the glucosylation of 5hmC protects the viral DNA and keeps in transcriptionally active. The intriguing results with bacterial RNAP prompted us to study the influence of natural or non-natural pyrimidine modifications on in vitro transcription (IVT) with bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase (T7 RNAP) which is used in enzymatic production of RNA through IVT49, including RNA vaccines50. There has been two previous related studies51,52 showing that small pyrimidine modifications (5-halouracil or 5-methyl- or 5-hydroxymethylcytosine) placed into the template (antisense) strand of the promoter do not prevent transcription. In this paper we present the synthesis of the modified nucleotides, enzymatic synthesis of DNA templates containing the modified nucleotides in either sense or antisense strand of the promoter or in both strands of the promoter or the whole sequence, as well as on the systematic study of the influence of the modifications on IVT with T7 RNAP (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Outline of the synthesis of modified DNA templates and study of the influence of pyrimidine modifications on IVT with T7 RNAP. Partially created in BioRender. Gracias, F. (2024) BioRender.com/p33m837.

Results

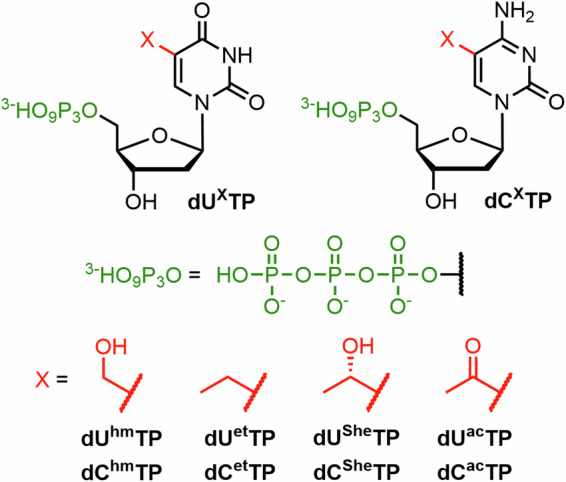

Similarly to our previous works40–48, we intended to synthesize modified DNA templates through polymerase incorporation of 5-substituted pyrimidine 2ʹ-deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates. We included some of the previously synthesized 5-hydroxymethyl-45, 5-ethyl-, 5-hydroxyethyl and 5-acetylpyrimidine46 nucleotides (Fig. 2), as well as several rare natural modifications, i.e., α-putrescinylthymine, α-glutaminylthymine, 5-dihydroxypentyluracil, and methylated or non-methylated aminomethyluracil, and related non-natural 5-sulfanylmethyl- and 5-cyanomethyluracil.

Fig. 2.

Additional nucleoside triphosphates used in this study. These nucleotides were previously prepared in our group.

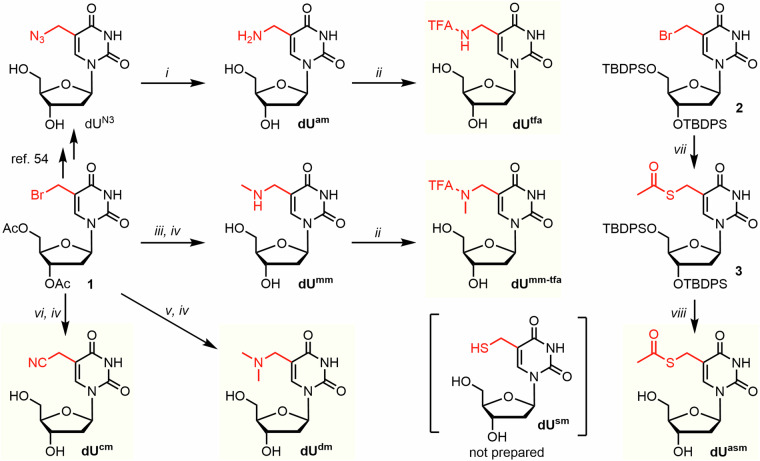

Firstly, we needed to synthesize the nucleoside intermediates where all highly nucleophilic groups needed suitable protection for the subsequent triphosphorylation. The synthesis of all started from thymidine, which upon protection and radical bromination provides the main intermediates—Ac-protected 5-bromomethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine 1 or TBDPS-protected 5-bromomethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine 2 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Synthetic overview of prepared nucleosides bearing small functional modification.

Reagents and conditions: i) Pd/C, H2, EtOH, H2O, 23 °C, 1.5 h; ii) TFAEt, Et3N, MeOH, 23 °C, 16 h; iii) MeNH2, Et3N, MeCN, 0 °C, 15 min; iv) NH4OH, MeOH, 23 °C, 2 h; v) Me2NH, Et3N, MeCN, –20 °C, 1.5 h; vi) KCN, DMF, 50 °C, 16 h; vii) AcSK, Et3N, DMF, 75 °C, 1.5 h; viii) TBAF, AcOH, THF, 23 °C, 4 h.

The acetyl-protected 5-bromomethyl-deoxyuridine intermediate (1) was used to prepare 5-(methylamino)methyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine (dUmm), 5-(dimethylamino)methyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine (dUdm) and 5-cyanomethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine (dUcm) in analogy to previously published procedures24,53–55. Nucleophilic substitution reactions with appropriate nucleophiles, followed by immediate deprotection provided the target nucleosides in moderate yields (17% for dUmm, 20% for dUdm and 7% for dUcm, in 4 steps from thymidine). These relatively low yields are mainly due to the bromination reaction55, which (in our hands) provided yields of only around 70% and the crude product could not be purified from the reaction mixture due its inherent high sensitivity to hydrolysis. Aminomethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine (dUam) was prepared by the previously reported54 catalytic hydrogenation of 5-azidomethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine. Both dUam and dUmm needed to be protected by the reaction with ethyl-trifluoroacetate and Et3N in methanol. Similar protection was needed in case of known 5-sulfanylmethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine56 (Usm), which was prepared directly as an S-acetyl protected dUsm (dUasm) from TBDPS-protected bromo-derivative (2) and potassium thioacetate, followed by TBDPS deprotection by acidified TBAF (29% in 4 steps from thymidine).

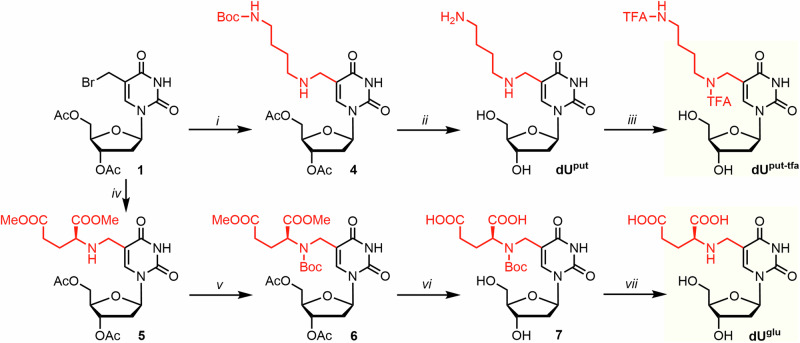

Next, we sought to prepare three non-canonical nucleosides that were found in several bacteriophages—namely putrescine-, glutamic acid-, and diol-linked thymidines (dUput, dUglu and dUdhp, respectively)24,25,27. Initially, we intended to prepare dUglu and dUput by reductive amination of acetyl protected 5-formyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine with the respective amine or glutamic acid. However, a problematic imine formation combined with an undesired 1,4-addition of tested reductive agents on imine made us abandon this approach and instead we choose the same reaction pathway as mentioned above. Hence, the dUput was prepared in an analogy to the previously published procedure24 but using Boc-protected putrescine as the nucleophile instead of reported monophthaloylputrescine (Fig. 4). Concomitant deprotection of both acetyl- and Boc- groups by acetyl chloride in dry methanol provided dUput (20% in 4 steps from thymidine) as the major product, which again needed to be TFA-protected before triphosphorylation. For dUglu, the nucleophilic substitution was performed using dimethylester of L-glutamic acid with Et3N in MeCN, instead of unprotected glutamic acid, which has shown insufficient reactivity and solubility in multiple reaction conditions. Attempted direct deprotection of both Ac- and Me- protecting groups on intermediate 5 resulted in cyclization of glutamic acid moiety to form 5-carboxy-γ-lactam modified nucleoside. Therefore, we performed a 3-step cascade that includes Boc-protection of the free amine, followed by prolonged complete deprotection of all acetyl and methyl groups by K2CO3 in H2O/MeOH mixture, followed by the final Boc-deprotection by TFA in DCM. This provided the desired dUglu in an acceptable yield (9% in 6 steps from thymidine) (for NMR spectra of all prepared compounds see Supplementary Data 1, for IR spectra see Figs. S145–S155 in Supplementary Information).

Fig. 4. Synthetic overview of putrescine- and glutamic acid-modified thymidine.

Reagents and conditions: i) N-Boc-putrescine, Et3N, DCM, 23 °C, 3 h; ii) AcCl, MeOH, 23 °C; iii) TFAEt, Et3N, MeOH, 23 °C, 16 h; iv) dimethyl-L-glutamate HCl, Et3N, DCM, 23 °C, 3 h; v) Boc2O, MeOH, 23 °C, 48 h; vi) K2CO3, H2O, MeOH, 23 °C, 24 h; vii) TFA, DCM, 23 °C, 35 min.

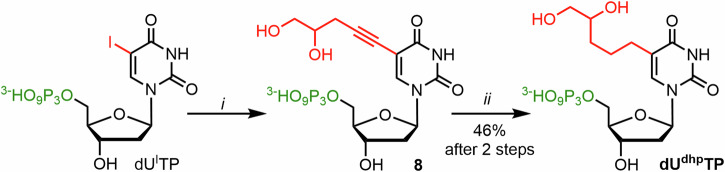

To avoid problems with selectivity in phosphorylation of nucleoside dUdhp, we have directly synthesized the corresponding nucleoside triphosphate (dUdhpTP) using Sonogashira coupling conditions on 5-iodo-2ʹ-deoxyuridine 5’-O-triphosphate with racemic 4,5-dihydroxypent-1-yne (Fig. 5), followed by Pd-catalyzed hydrogenation of the triple bond in analogy to previous work57. The desired dUdhpTP was obtained and isolated in 46% yield (in 2 steps from dUITP).

Fig. 5. Synthesis of dUdhpTP.

Reagents and conditions: i) Pd(OAc)2, CuI, TPPTS, Et3N, 80 °C, 1 h; ii) H2, H2O, MeOH, 23 °C, 24 h.

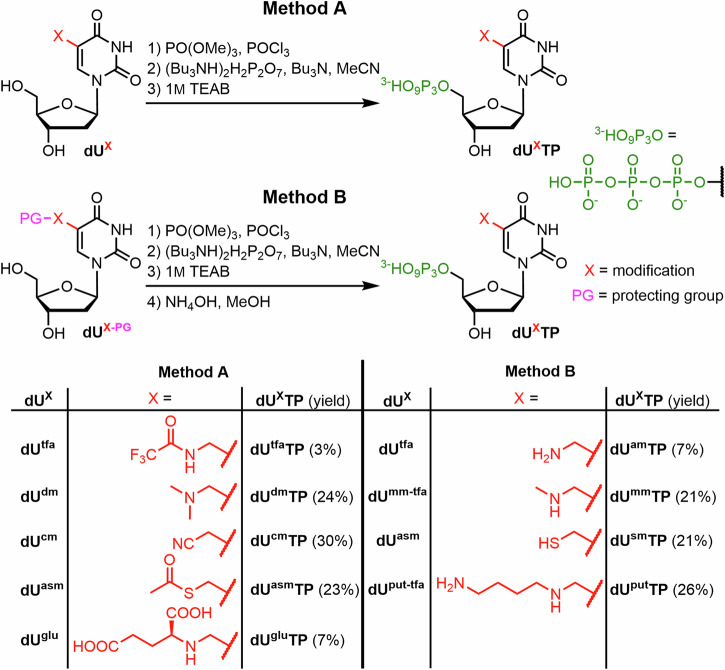

All the above mentioned nucleosides were phosphorylated using slightly modified standard Ludwig conditions58 with optional use of Proton Sponge, in some cases followed by immediate removal of protecting groups by aqueous ammonia (TFA removal in case of dUamTP, dUmmTP and dUputTP; Ac removal in case of dUsmTP) (Fig. 6). We also prepared two triphosphates with the protected aminomethyl and sulfanylmethyl groups (dUtfaTP and dUasmTP). The yields ranged from 3 to 30%. The lowest yields (3% for dUtfaTP and 7% for dUamTP) were achieved in triphosphorylation of dUtfa, which showed numerous side-products, probably due to partial deprotection and subsequent reactivity of the primary amine. Another low yielding procedure (7%) was the triphosphorylation of dUgluTP containing unprotected α-amino group of glutamic acid moiety, where the lower yield was compensated by shorter reaction sequence. All the desired dUXTPs were prepared in sufficient quantities for the follow-up biochemical profiling and synthesis of modified DNA templates.

Fig. 6. Synthesis of modified dNTPs through triphosphorylation of nucleosides.

Method A was used for the preparation of triphosphates without any deprotection step. Method B was used for the preparation of triphosphates with a protecting group, that needed to be removed post-triphosphorylation.

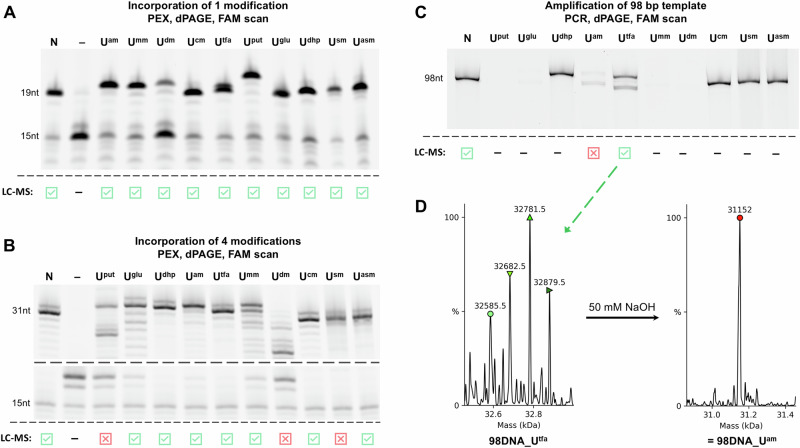

With the set of base-modified dUXTPs in hand, we first tested them as substrates for DNA polymerases in primer extension (PEX) using a 5ʹ-FAM-labelled 15-nt primer Prim15ON-FAM and a 19-nt template Temp19ON_T encoding for incorporation of one modified deoxyuridine (for sequences, see Table S2 in Supplementary Information). All modified dUX nucleotides were successfully incorporated into DNA in the PEX reactions using KOD XL DNA polymerase to produce 19-bp double-stranded DNA products 19DNA_UX that were visualized and characterized by both denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (dPAGE) (Fig. 7A and Fig. S2 in Supplementary Information) and by LC-MS using UniDec deconvolution tool59 (see Table S3 and Figs. S23–S46 in Supplementary Information). Only dUdmTP showed sub-optimal substrate activity, but the full-length product was still observed. More demanding PEX reaction using a 31-bp template Temp31ON encoding for four modifications (for sequences, see Table S4 in Supplementary Information) also worked for most modified dUXTPs and the resulting modified 31DNA_UX were characterized by dPAGE (Fig. 7B and Fig. S3 in Supplementary Information) and LC-MS (Table S5 and Figs. S47–S70 in Supplementary Information). Only dUgluTP, dUmmTP were less efficient substrates but still gave full-length products, while dUputTP and dUdmTP unfortunately did not give any full-length products. The thiol-linked triphosphate dUsmTP gave a full-length product according to dPAGE but the product 31DNA_Usm could not be confirmed by MS—probably due to the oxidation of the thiol group. We tried to mitigate this by adding dithiothreitol (DTT) or tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) into the reaction and after purification also to the solution of purified DNA but it did not help. We also tried to use S-acetyl protected analog dUasmTP, which could be incorporated into DNA and then deprotected by a solution of sodium hydroxide when needed. However, the S-acetyl group was quite unstable and prone to hydrolysis during standard PEX conditions.

Fig. 7. Summary of nucleoside triphosphate testing in enzymatic incorporations.

A Incorporation of 1 modified dUXTP by PEX to produce 19DNA_UX; B Incorporation of 4 modified dUXTP by PEX to produce 31DNA_UX; C Amplification of 98DNA by PCR with modified dUXTP; D LC-MS analysis of 98DNA_Utfa and its product after a treatment with aqueous NaOH. All enzymatic reactions use KOD XL polymerase. N = natural DNA, UX refer to modified nucleobases. LC-MS data deconvoluted using UniDec.

Testing of the dUXTPs in polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a 98 bp template 98DNA with 5ʹ-FAM-labelled 20-nt primer Prim20ON-FAM and 5ʹ-Cy5-labelled 25-nt primer Prim25ON-Cy5 (for sequences, see Table S6 in Supplementary Information) showed that only few triphosphates can provide full length amplicons, namely dUdhpTP, dUtfaTP, dUcmTP, dUasmTP and dUsmTP (Fig. 7C and Fig. S4 in Supplementary Information). In some cases, this was possible only after optimizations, extra Mg2+ ions or extra DTT (see Section 2.4.3. in Supplementary Information for more information). It should be noted, that incorporation of dUcmTP in PCR using a similar mixture of thermostable DNA polymerases was reported previously60. All the dNTPs with highly basic substituents (dUamTP, dUmmTP, dUdmTP and dUputTP) were poor substrates and did not give PCR amplicons. This can be explained by unfavorable repulsion of the protonated cationic substituent with positively charged basic arginine(s) and/or lysine(s) in the active site of the polymerase61. On the other hand, the TFA-protected dUtfaTP was incorporated well even in PCR, where the corresponding free amine dUamTP failed. LC-MS analysis of the PCR product (98DNA_Utfa) showed partial deprotection (three to seven TFA groups cleavages detected, Fig. 7D; Table S7 and Figs. S137–S140 in Supplementary Information). After a treatment with 50 mM NaOH for 1 hour, the follow-up LC-MS showed a mass corresponding to full length product of dUam-modified DNA (98DNA_Uam) (Fig. 7D; Figs. S141–S144 in Supplementary Information). This shows a viable route to longer DNA modified with Uam, even though the unprotected dUamTP is not an efficient substrate in more demanding polymerase reactions.

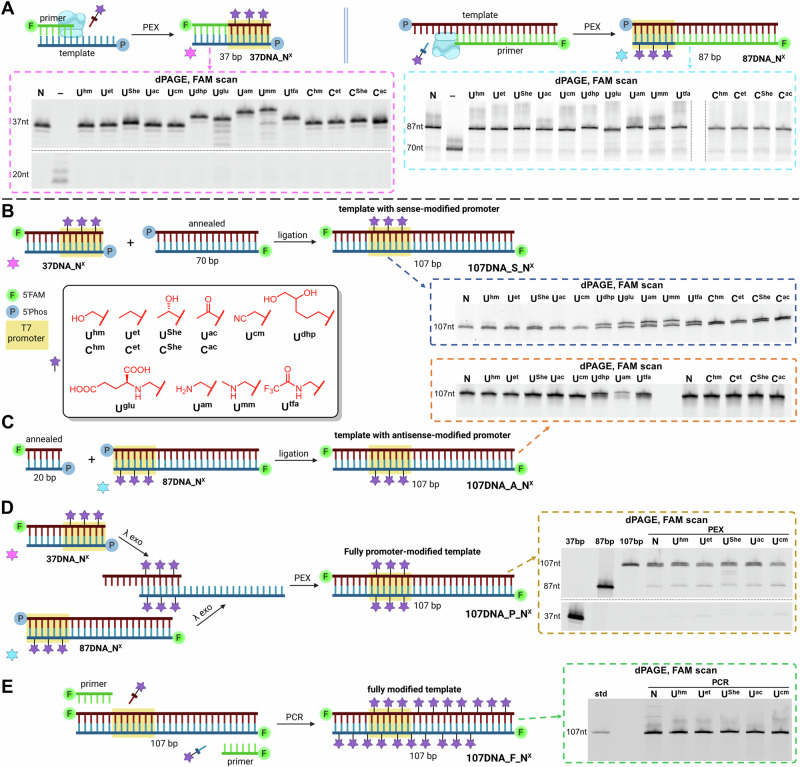

Next, we wanted to test all viable modified triphosphates as well as some previously prepared ones45,46 (Fig. 2) in in vitro transcriptions with T7 RNA polymerase. We wanted to study the transcription efficiency (the amount of RNA produced by T7 DNA polymerase) when we introduce our modifications in the T7 promoter region of either sense strand, antisense strand, both strands and also if we modify the whole DNA template. To this end, we designed a 107 bp template with the T7 promoter region localized between 21st and 37th base pair. The templates were also modified with FAM on both 5ʹ ends and, at the 5ʹ end of the antisense strand by three 2ʹ-OMe ribonucleotides, which help to prevent T7 RNA polymerase from non-templated additions62. This enabled us to prepare the modified templates using only enzymatic reactions and commercially available oligonucleotides. For each set of modified templates, a natural template was prepared in the same manner to be used as a reference.

To prepare templates with sense-modified promoter (107DNA_S), we first prepared modified 37-bp DNA (37DNA) containing T7 promoter region in a PEX reaction with KOD XL DNA polymerase using a 37-nt template Temp37ON-P and 5ʹ-FAM-labelled 20-nt primer Prim20ON-FAM (for sequences, see Table S8 in Supplementary Information). All used modified dNXTPs provided full-length PEX products, which were first confirmed by dPAGE (Fig. 8A and Fig. S5 in Supplementary Information) and LC-MS (Table S9 and Figs. S71–S102 in Supplementary Information) and then ligated to a 70-bp dsDNA by T4 DNA ligase, using optimized conditions (Fig. 8B) (for more information, see Section 2.7.1. in Supplementary Information). The desired products were then purified by gel extraction from an agarose gel. Previously in our lab we noticed that after preparative ligation reaction, a small amount of partially ligated (nicked) product can be generated. This nicked product can exist in two variants (depending on which strand is not ligated) and is purified from agarose gel together with the desired fully ligated template. Therefore, we performed a dPAGE analysis to check for presence of these nicked products. The analysis has shown presence of minimal amount of nicked products (see Fig. S9 in Supplementary Information for full gel) and so we proceeded forward by quantifying the amount of produced 107DNA_S templates based on 6-FAM signal (for more information, see Section 2.8.1. in Supplementary Information).

Fig. 8. Preparation of modified DNA building blocks and templates for transcription testing.

A Preparation of modified DNA building blocks 37DNA_NX (pink color) and 87DNA_NX (cyan color) by PEX reactions, using KOD XL polymerase; B preparation of templates with sense-modified promoter via ligation by T4 ligase; C preparation of templates with antisense-modified promoter via ligation by T4 ligase; D preparation of templates with fully modified promoter via partial λ-exo digestion of products in (A), followed by PEX reaction, using Vent (exo-) polymerase; E preparation of fully modified templates by PCR, using KOD XL polymerase. N = natural DNA, UX refer to modified nucleobases. Partially created in BioRender. Gracias, F. (2024) BioRender.com/l73g378.

Templates with antisense-modified promoter (107DNA_A) were prepared in a similar manner by first preparing modified 87-bp (87DNA) by PEX using an 87-nt template Temp87ON-P and either 5ʹ-FAM-labelled 70-nt primer Prim70ON-FAM (in case of UX) or 68-nt primer Prim68ON-FAM (in case of CX) (for sequences, see Tables S10 and S11 in Supplementary Information). The full-length products were confirmed by dPAGE (Fig. 8A and Figs. S6 and S7 in Supplementary Information) and (most of them also) by LC-MS (Table S12 and Figs. S103–S132 in Supplementary Information) and then ligated to 20-nt dsDNA (Fig. 8C). The dPAGE analysis after ligation showed some nicked products but still in minor amounts (see Fig. S10 in Supplementary Information for full gel). In this case, 107DNA_A_Umm and 107DNA_A_Uglu could not be prepared due to insufficient incorporation of the corresponding modified nucleotides in PEX reaction and were therefore not tested.

We also prepared templates with modified promoter in both strands (107DNA_P) and fully modified templates containing the modifications in both strands in the whole sequence (107DNA_F). Here we used only a subset of modified nucleobases, namely Uhm, Uet, UShe, Uac and Ucm (Fig. 8D, E), whose dNXTPs were good substrates in PEX and PCR and which gave some positive effect in transcription in our preliminary experiments. The promoter-modified templates (107DNA_P) were prepared by a Lambda exonuclease digestion of 5’-phosphorylated strand in 87DNA and 37DNA to produce modified single stranded DNA (ssDNA; 87ON and 37ON) (Fig. S8 in Supplementary Information). These two ssDNA were then combined and elongated in a double PEX reaction by Vent(exo-) DNA polymerase (Fig. 8D) (see Fig. S11 in Supplementary Information for full gel). Fully modified templates 107DNA_F were prepared by standard PCR with KOD XL DNA polymerase using the natural 107DNA_S used as a template with 5ʹ-FAM-labelled primers Prim20ON-FAM and Prim16ON-FAM (for sequences, see Table S17 in Supplementary Information), utilizing slightly modified conditions (Fig. 8E) (see Fig. S12 in Supplementary Information for full gel).

With these modified templates in hand, we moved to IVT testing. We chose to use T7 transcription conditions used previously in our lab63, with 10 ng of our templates for 1 hour, followed by DNA template digestion by DNase I for additional 15 min. In order to avoid working with radioactive isotopes (γ-32P GTP labelling of the RNA), we opted to visualize the synthesized RNA after gel electrophoresis by SYBR Gold staining (Fig. 9A). The fluorescent signal of RNA produced by natural template (N) was used as a control and assigned a value of 100%, to which signals of RNA produced from modified DNA templates were compared (Fig. 9). Each template was used for three separate transcription reactions and the results were averaged.

Fig. 9. Scheme of transcriptional testing and the follow-up results.

A General scheme for transcriptional testing; B results from templates with sense-modified promoter; C results from templates with antisense-modified promoter; D results from templates with fully-modified promoter; E results from fully modified templates. Natural DNA (N) was set to 100%. n = 3, error bars represent ±SD. Partially created in BioRender. Gracias, F. (2024) BioRender.com/q45b994; BioRender.com/p33m837.

Firstly, we tested IVT with templates containing modifications in sense-strand of promoter region (107DNA_S) and found that most of the tested modifications increased the amount of produced RNA by 20–65%, with Ucm being the modification with the most stimulating effect (Fig. 9B) (see Figs. S13 and S14 in Supplementary Information for full gel and graph). Only in case of Uglu and cytidine-modified Chm, CShe and Cac we saw some decrease of RNA synthesis (81%, 52%, 65% and 62%, respectively). Testing of templates with antisense-modified promoter 107DNA_A showed that Ucm was again the most transcription stimulating modification (135% compared to natural template), followed by Chm (125%) (Fig. 9C) (see Figs. S15–S17 in Supplementary Information for full gels and graph). The other modifications showed either negligible effect (90–110% compared to natural template) or stronger suppression effect (61% for UShe, 53% for Udhp, 10% for Uam and 16% for Utfa). Modification Utfa was particularly interesting, since it provided a stimulatory effect in sense-strand, but very strong inhibition in antisense-strand.

IVT reactions with templates modified in both strands (107DNA_P and 107DNA_F) were performed without subsequent DNase I treatment and instead the reaction was stopped by EDTA, followed by immediate denaturation to avoid an undesirable blocking of template digestion by one or more modifications64. Templates with fully modified promoter region (107DNA_P) showed in all cases similar or slightly lowered level of RNA production, compared to partially modified promoter templates (Fig. 9D) (see Figs. S18 and S19 in Supplementary Information for full gel and graph). Only Uhm and Ucm modifications showed a minor stimulatory effect on IVT (114% and 109%, respectively). The fully modified templates 107DNA_F in all cases gave lower transcription compared to non-modified template (Fig. 9E) (see Figs. S20 and S21 in Supplementary Information for full gel and graph) but the results were not too different from the promoter-modified templates suggesting minimal effect of these modifications outside of the promoter region.

Finally, we wanted to assess the fidelity of IVT with fully modified templates 107DNA_F through sequencing of the produced RNA (70RNA_F). Therefore, we prepared samples for the next generation sequencing (NGS) by reverse transcription of purified 70RNA_F from IVT, using M-MLV reverse transcriptase with target-specific primer Prim_RT18ON and template switching oligo TSO30ON, followed by PCR-based amplicon library preparations (see Section 2.9. in Supplementary Information for full description). Indexed libraries were pooled and sequenced on Illumina NovaSeq with an output of 2 millions of 2 ×150 bp paired-end reads per sample. The results (see Figs. S156–S162 in Supplementary Information) show high transcription fidelity with templates 107DNA_F containing natural T, or modified Uhm, Uet, UShe or Ucm nucleobases. Only in case of template containing the Uac modification, the resulting RNA contained several partial (4–5%) A → G mutations (mainly positions 13, 16, 25, 43). Apparently, these mutations are caused by misincorporations due to mutagenic minor base-pairing between Uac and G, similarly as has been previously reported for 5-formyluracil65. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that part of these mutations could have been introduced into the DNA during PCR with modified dUacTP.

Discussion

We have synthesized a series of dUXTPs derived from bacteriophage nucleotides and several related non-natural 5-substituted nucleosides and dUXTPs. The dUXTPs bearing strongly basic amino groups or glutamic acid, as well as oxidizable thiol were rather poor substrates for DNA polymerases, but in most cases they could be at least used in PEX synthesis of modified ssDNA. In PCR, most of them do not give good amplification. This is probably because of unfavorable interactions of the positively charged substituents with cationic amino acids in the active site of the enzyme. The comparison of our results with biosynthesis of viral DNA containing modified nucleobases shows a distinct correlation. The modifications that were easily incorporated even in PCR using modified dUXTPs (Uhm, Udhp) are biosynthetically available directly as nucleoside triphosphates, whereas Uglu and Uput, which failed to give full-length amplicon in PCR from their corresponding dUXTPs, are introduced into DNA via post-synthetic transformations of Uhm20.

We have successfully designed and executed the synthesis of DNA templates containing the modified pyrimidine nucleotides (including several previously reported45,46 modified 5-substituted uracil and cytosine nucleotides) in either non-template (sense), template (antisense) or in both strands of the promoter, as well as in the whole sequence and systematically studied the transcription with T7 RNAP. The effect of pyrimidine modifications on IVT with T7 RNA polymerase showed some similarities and some differences compared to previously reported works45,46,66 on the effect on transcription with bacterial RNAP. Similarly to the bacterial RNAP, some pyrimidine modifications showed a stimulatory effect on IVT with T7 RNAP, but this effect was significantly weaker (max. ca 170%) compared to E. coli RNAP, where some of the modifications showed more than two-fold increase in transcription (350% for Uhm, 250% for Chm and 200% for Uet)45,46. The strongest positive effect of most of the uracil modifications and a weak negative effect of cytosine modifications was observed in the non-template (sense) strand of DNA template. On the other hand, the modifications in the coding (antisense) strand showed higher differences where some nucleobases bearing small neutral modifications had slightly stimulating (Ucm, Chm, Uhm) or neutral (Uet, Cet, Uac, Cac) effect, whereas bulkier (Udhp, Utfa) or charged (Uam) modifications showed moderate to strong inhibiting effects. Several previous studies52,67–71 and X-ray structure72 of T7 RNAP showed that specific major-groove interactions are more important in the template strand which is in accord with our findings that some bulkier or charged modifications may disrupt these interactions and inhibit transcription. Conversely, the non-template (sense) strand apparently offers more freedom for accommodation of modifications which are generally better tolerated and some of them may even positively contribute to the interactions with the polymerase and thus enhance the transcription. However, a deeper mechanistic and structural biology study would be needed to fully understand the effects.

Unlike in the bacterial IVT45,46, the modifications in both strands has only minor effect on T7 RNAP IVT and there was no increase in IVT in fully modified templates. The bacteriophage-derived natural modified pyridimine nucleobases showed weak positive (Uam, Umm and Udhp) or negative (Uglu) effect in the sense-strand, but strong negative effect in the antisense strand (Uam and Udhp). Surprisingly, the non-natural 5-cyanomethyluracil (Ucm) showed the strongest stimulatory effects in most cases and we can envisage some biotechnological applications of this nucleotide in more efficient IVT synthesis of RNA with T7 RNAP. The influence of these modifications on bacterial and eukaryotic transcription that could shed more light into their biological role will be subject of a separate study.

Methods

Complete experimental part including synthesis of all nucleosides, nucleoside triphosphates and their characterization, and also of all enzymatic procedures, their analysis, DNA template preparations, in vitro transcriptions, and others are given in the Supplementary information.

Example of triphosphorylation reaction–preparation of 5-cyanomethyl-2ʹ-deoxyuridine-5ʹ-O-triphosphate, triethylammonium salt (dUcmTP)

dUcm (40 mg, 0.150 mmol) was dried on high vacuum for 16 hours and then suspended in PO(OMe)3 (0.5 mL), stirred at 23 °C for 10 min and then cooled to 0 °C. POCl3 (16 µL, 0.18 mmol) was added dropwise over 1 min and the reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 4 hours. Then, Bu3N (178 µL, 0.75 mmol) and chilled 0.5 M solution of (Bu3N)2H2P2O7 in MeCN (1.2 mL, 0.6 mmol) were added and the reaction was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min and then 15 min at 23 °C. The reaction was finished by adding 1 M TEAB (2 mL) and stirred for 15 min. The mixture was diluted with H2O, evaporated, diluted again with H2O (5 mL) and lyophilized for 16 hours. The lyophilizate was dissolved in H2O (22 mL) and separated on ion-exchange HPLC (0 to 100% of 800 mM TEAB in H2O, Sepharose DEAE Fast Flow). The appropriate fraction were collected, evaporated, dissolved in buffer A and injected into HPLC (0 to 30% of buffer B in buffer A, Kinetex EVO C18). The pure triphosphate dUcmTP (36.9 mg, 30%) was obtained as a hydroscopic amorphous solid.

Preparation of 37DNA, 37DNA_UX and 37DNA_CX by primer extension reaction

The reaction mixture (100 μL) contained primer Prim20ON-FAM (2.5 μM), template Temp37ON-P (2.5 μM), natural dNTPs (dATP, dGTP and either dCTP or dTTP, 200 μM each), appropriate dUXTP or dCXTP (for natural DNA either dTTP or dCTP, 200 μM; 300 μM for dUacTP; 400 μM for dUgluTP, dUamTP, dUmmTP), KOD XL polymerase reaction buffer (10 μL) and KOD XL DNA polymerase (5 U; 7.5 U for dUgluTP, dUamTP, dUmmTP). The reactions were then subjected to the following thermal cycler program: 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 55 °C for 10 min and then 72 °C for 5 min. The reactions were purified using QIAquick nucleotide removal kit (eluted in 30 μL of 5 mM Tris-Cl buffer, pH = 8.5).

DNA analysis by LC-MS

LC-MS measurements of DNA were measured on Agilent 1920 Infinity II BIO system with MSD XT mass spectrometer equipped with ESI ion source, using Phenomenex Biozen 1.7μm Oligo 50 ×2.1 mm column together with buffer A (300 mM HFIP + 15 mM TEA in H2O) and buffer B (300 mM HFIP + 15 mM TEA in MeOH). Gradients and flowrates were variable. Aquired spectra were deconvoluted using UniDec program with a deconvolution resolution of ± 0.5 Da.

Ligation reaction procedure

The reaction mixture (50 μL) contained two appropriately 5’-phosphorylated dsDNAs (0.8 μM each), T4 DNA ligase (3200 U) and 2X Quick ligation buffer (132 mM Tris, pH = 7.6, 20 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 2 mM rATP, 15% PEG 6000; 25 μL). The reaction was incubated at 23 °C for 30 min. After the reaction, samples were first pre-purified by QIAquick PCR purification kit (eluted in 30 μL of 5 mM Tris-Cl buffer, pH = 8.5). 6X loading dye (10 μL) was then added to the pre-purified samples and each sample was loaded onto 3% agarose gel (SERVA agarose for PCR, molecular biology grade) and run at 5 V/cm for 2 h. DNA was visualized by blue light transilluminator and the DNA of the desired length was cut out of the gel and purified on Qiagen MinElute columns, but using buffers and protocol from E.Z.N.A. Gel Extraction Kit (eluted in 15 μL of 5 mM Tris-Cl buffer, pH = 8.5). The products were then analyzed on denaturing PAGE to confirm the length of the products as well as the presence of only partially ligated DNA. This partially ligated DNA is visible as a residual FAM signal of the used dsDNA for the ligation.

Transcription reaction using 107DNA_S and 107DNA_S_UX/107DNA_S_CX containing sense-modified promoter

In vitro transcription reaction (20 μL) contained T7 transcription buffer (4 μL), MgCl2 (25 mM), Triton X-100 (0.1%), rNTPs mix (2 mM), RiboLock RNase Inhibitor (20 U), either natural or modified DNA template (107DNA_S, 107DNA_S_UX or 107DNA_S_CX; 10 ng, prepared according to Section 2.7.2.) and T7 RNA polymerase (20 U). Once the template was added, the reactions were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. DNase I (2 U) was then added and the reactions were further incubated at 37 °C for 15 min, followed by the addition of stop solution (40 μL) and H2O (20 μL). The samples were denatured (65 °C for 10 min), chilled on ice and 5 μL was loaded onto 12.5% denaturing PAGE which was run at 25 mA for 50 min. The gel was stained with SYBR Gold (diluted to 1X in 1X TBE buffer) for 15 min, scanned (Fig. S13 in Supplementary Information) and the relative amount of RNA quantified. The whole procedure was done in triplicate and the results were averaged.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

The work was funded by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic OPJAK grant RNA for therapy (CZ.02.01.01/00/22_008/0004575) co-financed by the EU. Ph.D. scholarship for F.G. from the Department of Organic Chemistry of the University of Chemistry and Technology Prague is also acknowledged. The authors thank NGS facility of IOCB Prague for the help with NGS RNA sequencing.

Author contributions

F.G. and M. H. designed the study, analyzed results and wrote the paper. F.G. performed the chemical synthesis and biochemical study. R.P. measured and characterized NMR spectra. V. S. and M. H. supervised the study and secured funding.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

Detailed procedures and data are given in Supplementary Information. NMR data are given in Supplementary Data 1. Primary data are available from repository 10.48700/datst.r2a7v-fw652.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. Michal Hocek is a Guest Editor for Communications Chemistry’s Nucleic Acid Chemistry Collection, but was not involved in the editorial review of, or the decision to publish this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42004-024-01354-5.

References

- 1.Luo, C., Hajkova, P. & Ecker, J. R. Dynamic DNA methylation: In the right place at the right time. Science361, 1336–1340 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carell, T., Kurz, M. Q., Müller, M., Rossa, M. & Spada, F. Non-canonical bases in the genome: the regulatory information layer in DNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.57, 4296–4312 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Raiber, E.-A., Hardisty, R., van Delft, P. & Balasubramanian, S. Mapping and elucidating the function of modified bases in DNA. Nat. Rev. Chem.1, 0069 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Münzel, M., Globisch, D. & Carell, T. 5-Hydroxymethylcytosine, the sixth base of the genome. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.50, 6460–6468 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Globisch, D. et al. Tissue distribution of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine and search for active demethylation intermediates. PLoS ONE5, e15367 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raiber, E.-A. et al. 5-Formylcytosine alters the structure of the DNA double helix. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol.22, 44–49 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, L. et al. Molecular basis for 5-carboxycytosine recognition by RNA polymerase II elongation complex. Nature523, 621–625 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu, X., Zhao, B. S. & He, C. TET family proteins: oxidation activity, interacting molecules, and functions in diseases. Chem. Rev.115, 2225–2239 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He, Y.-F. et al. Tet-mediated formation of 5-carboxylcytosine and its excision by TDG in mammalian DNA. Science333, 1303–1307 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kohli, R. M. & Zhang, Y. TET enzymes, TDG and the dynamics of DNA demethylation. Nature502, 472–479 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiesser, S. et al. Deamination, oxidation, and C-C bond cleavage reactivity of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine, and 5-carboxycytosine. J. Am. Chem. Soc.135, 14593–14599 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schön, A. et al. Analysis of an active deformylation mechanism of 5-formyl-deoxycytidine (fdC) in Stem Cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.59, 5591–5594 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lercher, L. et al. Structural insights into how 5-hydroxymethylation influences transcription factor binding. Chem. Commun.50, 1794–1796 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Perera, A. et al. TET3 is recruited by REST for context-specific hydroxymethylation and induction of gene expression. Cell Rep.11, 283–294 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kitsera, N. et al. Functional impacts of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine, 5-formylcytosine, and 5-carboxycytosine at a single hemi-modified CpG dinucleotide in a gene promoter. Nucleic Acids Res.45, 11033–11042 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pfaffeneder, T. et al. Tet oxidizes thymine to 5-hydroxymethyluracil in mouse embryonic stem cell DNA. Nat. Chem. Biol.10, 574–581 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Djuric, Z. et al. Levels of 5-hydroxymethyl-2’-deoxyuridine in DNA from blood as a marker of breast cancer. Cancer77, 691–696 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawasaki, F. et al. Genome-wide mapping of 5-hydroxymethyluracil in the eukaryote parasite Leishmania. Genome Biol.18, 23 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Olinski, R., Starczak, M. & Gackowski, D. Enigmatic 5-hydroxymethyluracil: Oxidatively modified base, epigenetic mark or both? Mutat. Res.767, 59–66 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weigele, P. & Raleigh, E. A. Biosynthesis and function of modified bases in bacteria and their viruses. Chem. Rev.116, 12655–12687 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hutinet, G., Lee, Y.-J., de Crécy-Lagard, V. & Weigele, P. R. Hypermodified DNA in Viruses of E. coli and Salmonella. Ecosal9, eESP00282019 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, Y.-J. et al. Identification and biosynthesis of thymidine hypermodifications in the genomic DNA of widespread bacterial viruses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA115, E3116–E3125 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kropinski, A. M., Bose, R. J. & Warren, R. A. 5-(4-Aminobutylaminomethyl)uracil, an unusual pyrimidine from the deoxyribonucleic acid of bacteriophage phiW-14. Biochemistry12, 151–157 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takeda, T., Ikeda, K., Mizuno, Y. & Ueda, T. Synthesis and properties of deoxyoligonucleotides containing putrescinylthymine (nucleosides and nucleotides. LXXVI). Chem. Pharm. Bull. 35, 3558–3567 (1987). . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Witmer, H. Synthesis of deoxythymidylate and the unusual deoxynucleotide in mature DNA of Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage SP10 occurs by postreplicational modification of 5-hydroxymethyldeoxyuridylate. J. Virol.39, 536–547 (1981). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walker, M. S. & Mandel, M. Biosynthesis of 5-(4’5’-dihydroxypentyl) uracil as a nucleoside triphosphate in bacteriophage SP15-infected Bacillus subtilis. J. Virol.25, 500–509 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayashi, H., Nakanishi, K., Brandon, C. & Marmur, J. Structure and synthesis of dihydroxypentyluracil from bacteriophage SP-15 deoxyribonucleic acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc.95, 8749–8757 (1973). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kornberg, S. R., Zimmerman, S. B. & Kornberg, A. Glucosylation of deoxyribonucleic acid by enzymes from bacteriophage-infected Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem.236, 1487–1493 (1961). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomaschewski, J., Gram, H., Crabb, J. W. & Rüger, W. T4-induced alpha- and beta-glucosyltransferase: cloning of the genes and a comparison of their products based on sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res.13, 7551–7568 (1985). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Leeuwen, F. et al. The telomeric GGGTTA repeats of Trypanosoma brucei contain the hypermodified base J in both strands. Nucleic Acids Res.24, 2476–2482 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, S., Ji, D., Cliffe, L., Sabatini, R. & Wang, Y. Quantitative mass spectrometry-based analysis of β-D-glucosyl-5-hydroxymethyluracil in genomic DNA of Trypanosoma brucei. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom.25, 1763–1770 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cross, M. et al. The modified base J is the target for a novel DNA-binding protein in kinetoplastid protozoans. EMBO J.18, 6573–6581 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xue, J.-H. et al. A vitamin-C-derived DNA modification catalysed by an algal TET homologue. Nature569, 581–585 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang, Z.-L. et al. Total synthesis of all stereoisomers of C5- glyceryl-methyl-2′-deoxycytidine 5gmC and their occurrence in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci.5, 102041 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mandal, D. et al. Identification and codon reading properties of 5-cyanomethyl uridine, a new modified nucleoside found in the anticodon wobble position of mutant haloarchaeal isoleucine tRNAs. RNA20, 177–188 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee, Y.-J. et al. Pathways of thymidine hypermodification. Nucleic Acids Res.50, 3001–3017 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang, L. H., Farnet, C. M., Ehrlich, K. C. & Ehrlich, M. Digestion of highly modified bacteriophage DNA by restriction endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res.10, 1579–1591 (1982). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flodman, K. et al. Type II restriction of bacteriophage DNA With 5hmdU-derived base modifications. Front. Microbiol.10, 584 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Casella, E., Markewych, O., Dosmar, M. & Witmer, H. Production and expression of dTMP-enriched DNA of bacteriophage SP15. J. Virol.28, 753–766 (1978). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macíčková-Cahová, H. & Hocek, M. Cleavage of adenine-modified functionalized DNA by type II restriction endonucleases. Nucleic Acids Res.37, 7612–7622 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macíčková-Cahová, H., Pohl, R. & Hocek, M. Cleavage of functionalized DNA containing 5-modified pyrimidines by type II restriction endonucleases. ChemBioChem12, 431–438 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kielkowski, P., Macíčková-Cahová, H., Pohl, R. & Hocek, M. Transient and switchable (triethylsilyl)ethynyl protection of DNA against cleavage by restriction endonucleases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.50, 8727–8730 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vaníková, Z. & Hocek, M. Polymerase synthesis of photocaged DNA resistant against cleavage by restriction endonucleases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.53, 6734–6737 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Raindlová, V. et al. Influence of major-groove chemical modifications of DNA on transcription by bacterial RNA polymerases. Nucleic Acids Res.44, 3000–3012 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janoušková, M. et al. 5-(Hydroxymethyl)uracil and -cytosine as potential epigenetic marks enhancing or inhibiting transcription with bacterial RNA polymerase. Chem. Commun.53, 13253–13255 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gracias, F. et al. Homologues of epigenetic pyrimidines: 5-alkyl-, 5-hydroxyalkyl and 5-acyluracil and -cytosine nucleotides: synthesis, enzymatic incorporation into DNA and effect on transcription with bacterial RNA polymerase. RSC Chem. Biol.3, 1069–1075 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chakrapani, A. et al. Glucosylated 5-hydroxymethylpyrimidines as epigenetic DNA bases regulating transcription and restriction cleavage. Chem. Eur. J.28, e202200911 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vaníková, Z., Janoušková, M., Kambová, M., Krásný, L. & Hocek, M. Switching transcription with bacterial RNA polymerase through photocaging, photorelease and phosphorylation reactions in the major groove of DNA. Chem. Sci.10, 3937–3942 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beckert, B. & Masquida, B. Synthesis of RNA by in vitro transcription. Methods Mol. Biol.703, 29–41 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nance, K. D. & Meier, J. L. Modifications in an emergency: the role of N1-Methylpseudouridine in COVID-19 Vaccines. ACS Cent. Sci.7, 748–756 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stahl, S. J. & Chamberlin, M. J. Transcription of T7 DNA containing modified nucleotides by bacteriophage T7 specific RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem.253, 4951–4959 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rastinejad, F. & Lu, P. Bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. 19F-nuclear magnetic resonance observations at 5-fluorouracil-substituted promoter DNA and RNA transcript. J. Mol. Biol.232, 105–122 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Edelman, M. S., Barfknecht, R. L., Huet-Rose, R., Boguslawski, S. & Mertes, M. P. Thymidylate synthetase inhibitors. Synthesis of N-substituted 5-aminomethyl-2’-deoxyuridine 5’-phosphates. J. Med. Chem.20, 669–673 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shiau, G. T., Schinazi, R. F., Chen, M. S. & Prusoff, W. H. Synthesis and biological activities of 5-(hydroxymethyl, azidomethyl, or aminomethyl)-2’-deoxyuridine and related 5’-substituted analogs. J. Med. Chem.23, 127–133 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.No, Z., Shin, D. S., Song, B. J., Ahn, M. & Ha, D. C. A facile one-pot synthesis of 2,3’-anhydro-2’-deoxyuridines via 3’-O-Imidazolylsulfonates. Synth. Commun.30, 3873–3882 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bornemann, B. & Marx, A. Synthesis of DNA oligonucleotides containing 5-(mercaptomethyl)-2’-deoxyuridine moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem.14, 6235–6238 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ondruš, M., Sýkorová, V., Bednárová, L., Pohl, R. & Hocek, M. Enzymatic synthesis of hypermodified DNA polymers for sequence-specific display of four different hydrophobic groups. Nucleic Acids Res.48, 11982–11993 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ludwig, J. A new route to nucleoside 5’-triphosphates. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Hung.16, 131–133 (1981). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marty, M. T. et al. Bayesian deconvolution of mass and ion mobility spectra: from binary interactions to polydisperse ensembles. Anal. Chem.87, 4370–4376 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kuwahara, M. et al. Systematic characterization of 2’-deoxynucleoside- 5’-triphosphate analogs as substrates for DNA polymerases by polymerase chain reaction and kinetic studies on enzymatic production of modified DNA. Nucleic Acids Res.34, 5383–5394 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kropp, H. M., Diederichs, K. & Marx, A. The structure of an archaeal B-family DNA polymerase in complex with a chemically modified nucleotide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.58, 5457–5461 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kao, C., Zheng, M. & Rüdisser, S. A simple and efficient method to reduce nontemplated nucleotide addition at the 3 terminus of RNAs transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase. RNA5, 1268–1272 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brunderová, M., Krömer, M., Vlková, M. & Hocek, M. Chloroacetamide-modified nucleotide and RNA for bioconjugations and cross-linking with RNA-binding. Proteins Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.62, e202213764 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kuprikova, N. et al. Superanionic DNA: enzymatic synthesis of hypermodified DNA bearing four different anionic substituents at all four nucleobases. Nucleic Acids Res.51, 11428–11438 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fujikawa, K., Kamiya, H. & Kasai, H. The mutations induced by oxidatively damaged nucleotides, 5-formyl-dUTP and 5-hydroxy-dCTP,in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res.26, 4582–4587 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chakrapani, A. et al. Photocaged 5-(hydroxymethyl)pyrimidine nucleoside phosphoramidites for specific photoactivatable epigenetic labeling of DNA. Org. Lett.22, 9081–9085 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ikeda, R. A., Ligman, C. M. & Warshamana, S. T7 promoter contacts essential for promoter activity in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res.20, 2517–2524 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jorgensen, E. D., Durbin, R. K., Risman, S. S. & McAllister, W. T. Specific contacts between the bacteriophage T3, T7, and SP6 RNA polymerases and their promoters. J. Biol. Chem.266, 645–651 (1991). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sastry, S. & Ross, B. M. Probing the interaction of T7 RNA polymerase with promoter. Biochemistry38, 4972–4981 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kochetkov, S. N., Rusakova, E. E. & Tunitskaya, V. L. Recent studies of T7 RNA polymerase mechanism. FEBS Lett.440, 264–267 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li, T., Ho, H. H., Maslak, M., Schick, C. & Martin, C. T. Major groove recognition elements in the middle of the T7 RNA polymerase promoter. Biochemistry35, 3722–3727 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cheetham, G. M., Jeruzalmi, D. & Steitz, T. A. Structural basis for initiation of transcription from an RNA polymerase-promoter complex. Nature399, 80–83 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Detailed procedures and data are given in Supplementary Information. NMR data are given in Supplementary Data 1. Primary data are available from repository 10.48700/datst.r2a7v-fw652.