Abstract

Introduction

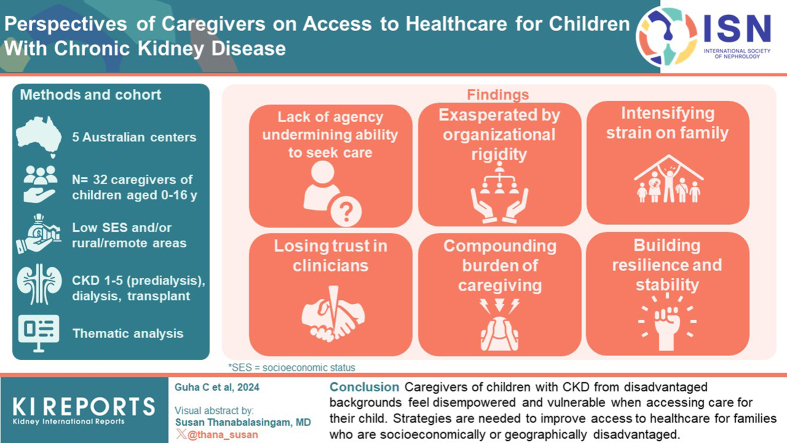

Inequitable access to health care based on demographic factors such as ethnicity, socioeconomic status and geographical location has been consistently found in children with chronic kidney disease (CKD). However, little is known about the perspectives of caregivers on accessing health care. We described caregivers’ perspectives on accessing health care for children with CKD from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds and/or rural or remote areas.

Methods

Caregivers of Australian children aged 0 to 16 years, across all CKD stages, from low socioeconomic status backgrounds, and/or residing in rural or remote areas, purposively sampled from 5 centers, participated in semi structured interviews on accessing health care. Transcripts were analyzed thematically.

Results

From 32 interviews, we identified 6 themes: lack of agency undermining ability to seek care (obscurity of symptoms, uncertain and confused about care processes, and vulnerable and unable to advocate), losing trust in clinicians (confused by inconsistencies and ambiguities in advice, and distressed by lack of collaborative care), exasperated by organizational rigidity (frustrated by bureaucratic roadblocks, lack of access to specialist care in rural and remote settings, and inadequacies of support programs), compounding burden of caregiving (unsustainable financial pressure, debilitating exhaustion, and asymmetry of responsibility), intensifying strain on family (uprooting to relocate, sibling stress and neglect, and depending on family support), building resilience and stability (empowerment through education and confidence in technical and medical support).

Conclusions

Caregivers of children with CKD from disadvantaged backgrounds feel disempowered and vulnerable when accessing care for their child. Strategies are needed to improve access to health care for families who are socioeconomically or geographically disadvantaged.

Keywords: access, caregivers, chronic kidney disease, healthcare, pediatric

Graphical abstract

Children with CKD face increased risks of neurocognitive disorders, multiple morbidities, and premature death.1, 2, 3 The complex nature of CKD requires access to multiple health care services leading to dependence on caregivers4 who are required to coordinate appointments, monitor their child’s health, and potentially administer invasive treatments such as home dialysis and enteral feeding.5,6 Navigating these complex care regimens, including coordinating care among multiple health care providers, understanding medical terminology, and financing treatment costs,7 can be challenging for caregivers.

Access to care for patients with CKD can vary across countries, influenced by factors such as health care systems, socioeconomic conditions, and geographic locations. For example, in low to middle-income countries, the availability of dialysis care often necessitates copayments from patients, placing a significant financial burden on those affected. Conversely, in high-income countries such as Australia and the UK, public health care systems cover dialysis costs, thereby reducing financial barriers.7, 8, 9 Socioeconomic disadvantage and geographical remoteness, particularly in areas with limited access to specialist pediatric CKD health services, pose barriers to equitable access to care.7,10 This is associated with increased rates of comorbidities, poorer clinical outcomes, and diminished quality of life for patients experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage and/or living in rural and remote areas.11, 12, 13, 14 In Australia, a universal health care system, covers many health care costs, including visits to general practitioners and public hospital stays.15 However, persistent challenges such as transportation costs exist affecting access to health care, particularly for those in remote areas and lower socioeconomic groups.9 The burden of care contributes to economical, physical, and psychosocial stress, particularly among caregivers from disadvantaged backgrounds.5,9,16,17

Despite the pivotal role of caregivers in outcomes for children with CKD, little is known about their experiences of accessing health care, particularly in those who are known to have reduced access due to geographical isolation or socioeconomic disadvantage. Understanding their perspectives, from those who are the most vulnerable, can inform interventions, strategies, and policies to improve access and outcomes for children with CKD and their families. This study aims to describe the perspectives of caregivers of children with CKD from low socioeconomic backgrounds and/or living in rural and remote areas on access to health care.

Methods

This qualitative study is reported according to the Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research.18

Context

This study was conducted as part of the NAVKIDS2 trial: a multicenter, waitlisted randomized controlled trial of a patient navigator intervention that aimed to assess the effects of patient navigation (intervention) on the self-rated health of children with CKD. The trial design has been previously described.4,19,20 NAVKIDS2 was registered on the Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12618001152213 and reported as per the CONSORT 2010 statement.21,22 Patients were eligible to participate if they were aged from 0 to 16 years, with CKD stages 1 to 5, receiving dialysis or with a kidney transplant, from low socioeconomic status backgrounds, and/or residing in rural or remote areas.4,20 The trial was conducted across 5 pediatric centers across Australia between 2020 and 2022. Participants were included if they fulfilled any of the following criteria: if caregivers had a weekly income below the median income of $1250 (AUD) or had a low self-perceived income status (having inadequate income or economic resources), where both partners were unemployed, were living in public housing, or were single parents on social benefits, or lived in rural or remote areas (classified by the Australian Statistical Geography Standard as Inner Regional to Very Remote Australia (RA2-RA5).

Participant Selection and Recruitment

The inclusion criteria for this study were the same as for the trial. All adult English-speaking caregivers of participants who were enrolled in the NAVKIDS2 trial were invited to this qualitative study. Participants for this qualitative study were sampled purposively from the participants of the NAVKIDS2 trial to include a diverse range of demographic and clinical characteristics.

Data Collection

The semistructured interviews lasted between 24 and 70 minutes and were conducted prior to the commencement of the trial either face-to-face at the hospitals, over telephone or online using videoconferencing platforms such as Zoom, depending on the preference of the participants. The interview guide was developed based on the literature,9,10,16,23,24 including Levesque’s conceptual framework of access to health care25 and discussion among the research team. (Interview guide for caregivers and Supplementary Figure S1). First author (CG), with experience in qualitative research conducted the interviews from July 2020 to May 2021 until data saturation, defined as when no new data emerged. All interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Data Analysis

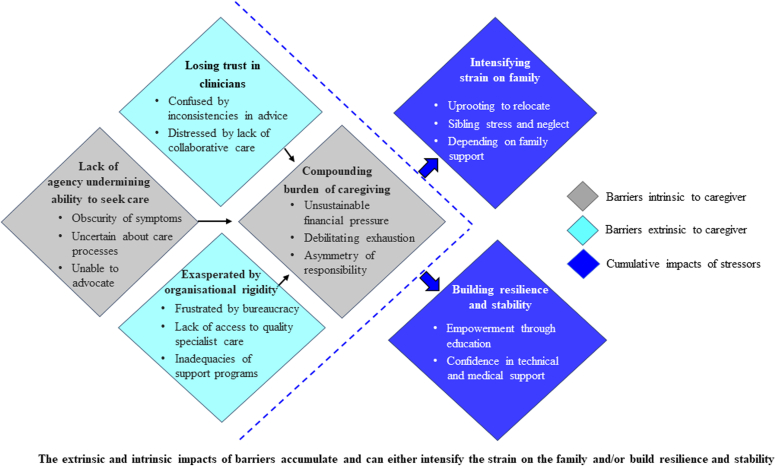

Using thematic analysis, CG read each transcript line-by-line, then conceptualized, and coded all meaningful segments of text into concepts inductively identified from the data. Similar concepts were grouped into preliminary themes and subthemes. Authors CG and AJ discussed the preliminary coding structure to ensure that it captured the full breadth and depth of data collected. The transcripts were imported into Hyper RESEARCH (Version 4.5.4; Research Ware Inc.). The software was used to generate a report of the themes and qualitative data coded to each theme. CG and AJ identified and discussed conceptual patterns among the themes, which were mapped into a schema (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schema-perspectives of caregivers on access to care for children with CKD. CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Consumer Involvement

This study was led by CG who is a caregiver of her daughter diagnosed with childhood CKD and LM was involved in a consumer capacity.

Results

Of the 162 participants in the NAVKIDS2 trial, 106 from the 5 pediatric centers consented to participate in the interview study. In total, 32 caregivers completed the interviews. Participant and patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median (interquartile range) age of the participants was 36.5 (32.8–40.2) (mean [SD], 36.4 [6.9]) years. Thirty-one participants were parents, 1 participant was a grandparent, and 29 participants (91%) were female. Over one-fifth (22%) of the families perceived themselves as “poor” financially, 75% were “just getting along,” and 53% earned below $1250 AUD per week. Most caregivers were married or partnered (66%), whereas 28% were single caregivers on social benefits. A quarter of the families lived in rural/remote regions.

Table 1.

Patient and caregivers’ characteristics (N = 32)a

| Child age (yrs) mean (SD) | 8.3 (4.1) |

| Child gender (%) male | 20 (63) |

| Household income (%) | |

| $0–$31,199/yr | 7 (22) |

| $31,200–$64,999/yr | 10 (31) |

| $65,000–$104,000/yr | 6 (19) |

| > $104,000/yr | 2 (6.3) |

| No response | 7 (22) |

| Family perceived financial status (%)b | |

| Reasonably comfortable | 1 (3.1) |

| Just getting along | 24 (75) |

| Poor | 7 (22) |

| Region RA1–RA5 (%)c | |

| RA 1: major cities of Australia | 22 (69) |

| RA 2: inner regional Australia | 8 (25) |

| RA 4: remote Australia | 1 (3.1) |

| RA 5: very remote Australia | 1 (3.1) |

| Primary ethnicity (%) | |

| European Australian | 17 (53) |

| Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander | 4 (12) |

| Asian | 2 (6.3) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (3.1) |

| Pacific Islander | 1 (3.1) |

| Not specified | 1 (3.1) |

| Other | 6 (19) |

| Languaged (%) | |

| English | 32 (100) |

| Other | 2 (6.3) |

| Marital status of caregivers (%) | |

| Single | 7 (22) |

| Partnered | 2 (6.3) |

| Married/de facto | 19 (59) |

| Divorced/separated | 4 (12) |

| Single caregiver on social benefits (Yes) | 9 (28) |

| Both caregivers unemployed (Yes) | 9 (28) |

| Family lives in public housing (Yes) | 5 (16) |

| Caregiver age (yr)-mean (SD) | 36.4 (6.9) |

| Caregiver gender - female | 29 (91%) |

| CKD stage (%) | |

| Stage 1–5 (predialysis) | 20 (60.3) |

| Dialysise | 4 (13) |

| Transplant | 8 (25) |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; RA, remoteness area.

Inclusion criteria: median income <$1250, AUD/ self-perceived income, employment status of caregivers/single parent/families living in public housing.

n (%) unless otherwise specified, caregivers: 31 were biological parents, 1 was a grandparent.

No participant belonged to “prosperous,” “comfortable,” or “very poor” category.

No participants belonged to RA3: outer regional Australia.

Does not add up to 100% due to children speaking multiple languages.

Hemodialysis - 1, Peritoneal dialysis- 3.

Themes

We identified the following 6 themes: (i) lack of agency undermining ability to seek care, (ii) losing trust in clinicians, (iii) exasperated by organizational rigidity, (iv) compounding burden of caregiving, (v) intensifying strain on family, and (vi) building resilience and stability. The themes and respective subthemes are described in this section with further illustrative quotations to support each theme provided in Table 2. A thematic schema illustrating the relationship among themes and subthemes is shown in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Illustrative quotations supporting each theme

| Theme | Participant quotations |

|---|---|

| Lack of agency undermining ability to seek care | |

| Obscurity of symptoms | “I could hardly lift him up. He was so puffy, and …we didn't know until I noticed that he wasn't walking normally.” Female, 39 yrs. “They really didn't know what it was at the time because his kidneys were so small that they couldn't really pick them up on the ultrasounds … it was a long like week or 2 of just not really knowing and just understanding that there was something wrong with his kidneys, but we didn't know what” Female, 24 yrs. |

| Uncertain and confused about care processes | “We could have done with more help around the management of our case. We were left to bring everything together at times or that's how it felt …that's probably the biggest issue that we had.” Male, 32 yrs. “I cried … because I cared about the aftercare. What am I facing? What do I have to do? What happens if it (the feeding tube) pops out? No one told me any of that.” Female, 38 yrs. "It was very hard. You had to kind of squish all your information into a very short amount of time because obviously they need to see numerous people throughout the working day. Um, so I found I didn't necessarily get to everything that I needed to. Yeah. And so, they would leave and then it would all come back into my head and just stay there.” Female, 35 yrs “We were new to the country; we had been in Australia for a month. That was a very tough experience for us and also the language barrier and the cultural barrier was a bit of an experience. …for example, when we ask for copies of blood results, the nurses wouldn’t give it to us and there is a way of asking for it... but I don’t know (how to ask).” Female 39 yrs. |

| Vulnerable and unable to advocate | “I didn't really feel like I was in control. I felt like I didn't have that 100% choice in choosing whether my daughter wanted to have the PEG (feeding tube) or not.” Female, 38 yrs. “You often get pushed aside as a parent by some doctors, not all, some doctors are amazing and very encouraging and speak with you and want to know more and a 100% believe what you say, but you get other doctors that want to dismiss you.” Female, 28 yrs. “You're allowed to say okay, this treatment plan isn't working okay, my child is clearly still in pain, I want more pain medication. It took me so long to learn to speak up confidently. (Name of child) definitely went through situations where he unintentionally suffered.” Female, 28 yrs. |

| Losing trust in clinicians | |

| Confused by inconsistencies and ambiguities in advice | “There were a lot of inconsistencies coming from different medical staff about various issues we had. People saying …. we’ll be able to sort that out and work that out. And then somebody else turning around and saying, no, that's not possible.” Female, 35 yrs. “I feel like when you are seeing so many different specialists and all the issues sort of blur together, it's really hard to keep up with who's saying what and what's okay with one person and the other person. So, I was having a lot of like, oh this person said this and then they'll be like, oh, but that's irrelevant for this or whatever.” Female, 35 yrs. |

| Distressed by lack of collaborative care | “They just kept on sending us home with silly things. ...everybody knew there was something not right. Her bloods were showing that she had acidosis and all the rest of the jazz. But they weren't proactive in actually having a look at what was going on behind it and getting (name of hospital) involved and getting the renal specialists involved.” Female, 36 yrs. “It's becoming very much to the point where I don't want to have to deal with the hospital up here because they keep brushing my son off, and they're making my son worse.” Female, 33 yrs. “Because we weren't being listened to, we weren't being heard, we were in a regional center, so they have a lot of churns with locum pediatricians. So, we didn't have any consistency from that point of view either. We kept seeing different doctors every time, so (name of patient) was really unwell by the end.” Female, aged 39 yrs |

| Exasperated by organizational rigidity | |

| Frustrated by bureaucratic roadblocks | “You know, the system is too bureaucratic. It seems like bullshit to get through. You never get to the hard and fast fact of what you're eligible for, what you're entitled to, what the outcome will be. No one ever knows. It's almost like you go out there as a guest to what you can find. That is the failure of the system.” Female, 50 yrs. “You can't always get them (appointments) on the same day. And if I can't then I have to stay at the Ronald McDonald House overnight or …try having to come back twice in 1 week (which) is basically impossible.” Female, 34 yrs. |

| Lack of access to expert and quality specialist care | “We were up in (name of regional center) so when you present to ED, then they usually get the pediatric team down to see you. But most of the pediatricians that we were seeing were locums. So, we didn't have any consistency.” Female, 36 yrs. “The main concern for us is (name of child) gets sick. To get to a pediatric service hospital is a drive at least 3 or 4 hours to get there. To access a health system for a kid living in the rural remote places, it's very hard.” Male, 36 yrs. |

| Inadequacies of support programs | “(Name of patient) has now been needing these catheters in and out every, every night. They're super expensive to buy. There's the company that orders it (catheters) and there's the company that provides it. There were times where I was buying the catheters because I just didn't get any delivered because someone hadn't sent an email.” Female, 39 yrs. “Nobody would actually classify (name of patient) as being disabled or needing assistance. Even (name of welfare service) would not classify her as disabled even though she had a colostomy bag. And before the age 1 yr, she had a left foot amputated because she had cleft left foot. So, she's got a prosthesis as well. But they would not classify her as any form of disability.” Female, 41 yrs. “I remember the social worker recommending a few things (related to accessing Centrelink) …and I found a lot of the times they would say, oh, we'll try and find that out for you. And it would just get lost in amongst everything else that was going on. ...I can understand that from a health professional point of view…but from a parent point of view, it's frustrating because then you are kind of left with, well what do I do?” Female, 35 yrs. I did, uh, ask for few things that this social worker, um, I really wasn't satisfied with the answers; I asked the social worker and um, she said she had come back to me with the phone number (for legal aid), which took her about a week to give it to me. So, when she came back to me, I said, well, I already got it. because by then I had noticed in the kitchen that there was the phone number for legal aids.” Female 39 yrs. |

| Compounding burden of caregiving | |

| Unsustainable financial pressure | “I struggled from the minute (patient’s name) was born. I couldn't go back to work. Everything got behind. It kept getting worse to the point 18 months ago I couldn't live with it anymore and I had to make that decision to declare bankruptcy. So that has majorly affected my life. It's not somewhere I thought I'd be at 30 years of age.” Female, 30 yrs. “Prior to having (name of patient), we had 2 relatively good incomes and, so to drop the one income completely was a big shock. I always had a sense of guilt that I couldn't work, and I couldn't bring in an income because I'd always brought in an income… I would like nothing more than to be able to bring in a second income.” Female, 28 yrs. “When she was diagnosed and basically being told that you've got albumin infusions twice a week, and then you always thinking back, how are we going to facilitate this? I've got two other kids, then we had to shut down our business so my husband could sort of work around the kids' schedule.” Female, 42 yrs. |

| Debilitating exhaustion | “And when she (the patient) was discharged that same night, I had like a stroke-like condition, where half of my body just shut down and I stayed in the hospital for the next 2 wks.” Female, 38 yrs. “I've got a disability; I couldn't sort of do everything and I was very fatigued. Like I've just had a child and then I'm running up and down the freeway and it was just chaos.” Female, 42 yrs. |

| Asymmetry of responsibility | “His dad, he wasn't very supportive. So, it was hard. It made it harder for me.” Female, 38 yrs. “It actually does get to the point where some days it feels like I'm trapped in medical prison because all the care falls onto me. If I'm not there (name of patient) won't get his medication. Cause my husband is too scared to make it up. And it doesn't matter how many times I show him, he won't make the medication up, which then means I'm going to go somewhere, I just can't do it without planning.” Female, 39 yrs. “I like to do it all myself…I have a file in my bag and ...it's got all of his most recent blood reports, doctors letters, ...everything, anything we need for (name of patient). Now, if I hand over the care over to his dad to do that: number 1, (name of father) wouldn't really want to do it. ...And number 2, I, I don't think it'll get done.” Female 39 yrs. |

| Intensifying strain on family | |

| Uprooting to relocate | “We've had to shift because we don't trust the health service. …she ended up in ICU down in (name of location) and it still took them 16 hours to fly out. So, after that experience we kind of just went, we can't do this anymore. We need to be closer to Brisbane so we can be within driving distance.” Female, 39 yrs. “She needs to be close to a hospital so that she gets more attention. So that's why I basically started looking for newer jobs. That's why like I picked up job in (name of location).” Male, 36 yrs. |

| Sibling stress and neglect | “He hits, he punches, he threatens to pull (patient’s) cord out, so he dies. He's angry at me I think for sending him to live with my mum for 2 yrs and I kept the 3 little ones with me…. Threatening to break his (patient’s) arm when he had the fistula put in. Just horrible things.” Female, 42 yrs. “So, the first 3 months after diagnosis, we were living in and out of hospital…. I had to drop (sibling) off to someone to care for her during the day to get to the hospital in time.......(sibling) has a lot of anxiety, and I feel like a lot of it has come from the fact that she felt a bit abandoned. …I don't feel that her needs were being met as well as they could have been....so it's impacted her (sibling) immensely and we are still struggling with behaviors that have come out of that...” Female, 36 yrs. |

| Depending on family support | “They (family) provided a lot of support. …. right down to when (name of patient) had his transplant, ….and they did like a cook up of food and brought things up to the hospital cause they knew we were in hospital for a while and, brought up a little goody pack and like they, they provided a shoulder that I needed.” Female, 28 yrs. “My mom is very close with us, so if ever I need anything, she's always there to help and she takes them for a bit... And, and my sister, she's always there as well and the kids (siblings) will go over to her house, and she'll mind them.” Female, 35 yrs. “Socially we were even more isolated because, (name of patient) wasn't physically going to school either, cause you don't want to be sick when you're on dialysis… Because we didn't know anyone in the area, we were on our own. And my partner was leaving at 6, 6.30 in the morning and coming back at 6.30 at night. So, we were definitely just my son and me. And it's, it's been difficult at the same time.” Female, 39 yrs. |

| Building resilience and stability | |

| Empowerment through education | “This is the patient travel service… which in the very beginning we didn't know existed. And we were ringing accommodation places …And we ended up at the (name of the accommodation), which was very close to the hospital and the ladies there actually told me about the patient travel system and said, you need to ring (name of hospital) as your local hospital. And tell them about your situation.” The psychologist came down to (name of patient) and they'd done a little book up for her so that she knew what to expect when it comes coming into dialysis. And I think that was brilliant for her because that gave her more confidence in what she was doing.” Female, 41 yrs. Families who have been in the system long term, are very, very good at what they do (accessing the hospital system).” Female 35, yrs. “And then also not knowing what services were available (when newly diagnosed) and not knowing who to ask if there was service available. Because now I'm very comfortable with the renal nurses. …I've known them 5 years now, so they're almost like friends. But at the start, I definitely didn't have that rapport.” Female, 28 yrs. |

| Confidence in technical and medical support | “I do speak with her (nurse) a lot. She's on to making sure we get regular appointments in (hospital) and I can contact her if I need something.” Female, 30 yrs. “We found the renal team at the hospital to be quite good. They have a smaller number of patients, you know, they are a smaller team. Access to them been very, very good.” Male, 32 yrs. |

Lack of Agency Undermining Ability to Seek Care

Obscurity of Symptoms

Caregivers of children with CKD reported that they were sometimes unable to access timely care because the early symptoms of CKD were not apparent, or the symptoms were not specific to CKD (“massive fatigue”). They noted that clinicians were uncertain whether the symptoms were indicative of a “a kidney issue” or were associated with a different condition, leading to delays in diagnosis. In cases of rare, genetic diseases (e.g., tuberous sclerosis causing tumors in many parts of the body, including kidneys), participants felt they were unable to receive a prompt and accurate diagnosis of the CKD due to the “unknown nature” of the disease.

Uncertain and Confused About Care Processes

Participants overwhelmed by “medical jargon,” were unable to process the amount and pace of information received. Where children required complex treatments (e.g., dialysis or transplantation) or had multiple comorbidities, (e.g., gastrointestinal conditions), coordinating multiple care teams was “the biggest issue.” After devices such as feeding tubes or catheters were (surgically) placed in their children, caregivers were unsure about “who to call” or “where to go” if the device “popped out.” Participants “new to the country” and “not knowing how the system works” had difficulties accessing information and care due to language and cultural barriers. They were unsure of how to ask for their child’s medical files and health information.

Vulnerable and unable to advocate

Some participants believed they were “not in control,” “didn’t have 100% choice,” or “did not have the right” to be involved in their child’s treatment and felt their voices were not heard; for example, request for a “a blood test” was ignored, which delayed the diagnosis of CKD. Feeling dismissed or “pushed aside as a parent by some doctors,” they lacked the confidence to “speak up” and were unable to ask questions of their clinicians.

Losing Trust in Clinicians

Confused by Inconsistencies and Ambiguities in Advice

Participants were confused due to conflicting or unclear information from health care teams, such as unclear instructions on measuring fluid intake for breastfed babies with CKD under fluid restriction. Participants with children managing multiple issues, such as CKD and a stoma bag, found it challenging to navigate conflicting advice from different care teams (e.g., nephrology and gastroenterology). “I was having a lot of, oh this person said this and then…, but that's irrelevant for this or whatever.”

Distressed by Lack of Collaborative Care

Some participants felt there was a lack of collaboration among medical specialty teams, emergency department doctors, and the nephrology team, which they believed could potentially jeopardize the care and outcomes for their child. They believed that non-nephrology clinicians did not understand or consider the impact of their treatment on the underlying kidney condition and “a lot of miscommunications” resulted in harm and/or “longer hospital stays.” When coordinating care between both rural and urban hospitals, participants believed that “differences in the care teams, a lack of coordination and interrupted continuity of care” could result in adverse outcomes. A participant living in a rural area was concerned that the local emergency doctors advised to administer oral rehydration solution (hydrolyte) to her child on peritoneal dialysis without consulting a nephrologist. Another participant whose child had a nasal tube inserted (at the metropolitan hospital) was distressed after being transferred to the local rural emergency department as she found her child “without a feeding tube” and no one knew when the child was last fed.

Exasperated by Organizational Rigidity

Frustrated by Bureaucratic Roadblocks

Scheduling multiple appointments and travelling between multiple clinics was considered the “most challenging” part of accessing care. Participants felt that clinicians did not consider the distress and disruption to the child. For example, commencing dialysis in the afternoon could cause the child to be fatigued and “miss school” the following day. Participants from remote and rural areas sometimes made “extra trips” to the hospital and incurred “extra costs,” including travel, parking, and meal expenses when requests to schedule their appointments in ways that could minimize the travel burden, such as organizing them over a single day, were declined.

Lack of Access to Expert and Quality Specialist Care

For participants in rural and remote areas, the absence of pediatric nephrologists, inpatient and intensive care services locally meant some participants had to travel long distances: “200 km 2 or 3 times a week (for their child) to get treatment.” One participant reported that the local hospital, “didn't have the correct size of the feeding tube” and was frustrated when “no one could put it in.” Participants in rural or remote areas felt that relying on locum clinical staff and having to explain their child’s treatment regimens to a different person each time led to “inconsistent relationships” between patient and clinicians.

Inadequacies of Support Programs

Participants lacked awareness or clarity about the social security services, payments, and products available to them through welfare organizations and government departments (such as Centrelink and National Disability Insurance Scheme). They felt that the application processes did not capture the rare or complex conditions of their child, were too complicated, and an administrative “nightmare.” One participant reported that her “child was not classified as disabled” despite having “an amputated foot and a colostomy bag” and regardless of “numerous doctors’ letters.” In contrast, despite being eligible for support, some participants still faced financial stresses when they had to purchase medical supplies (e.g., catheters and continence products), due to administrative lapses by the providers (such as delayed reimbursements). Participants were disappointed when allied health providers did not follow through with information required for accessing the financial support products or services (e.g., information on Centrelink) they had promised to provide.

Compounding Burden of Caregiving

Unsustainable Financial Pressure

Participants believed that their “family life, careers and finances” were all “thrown into chaos” by the financial burden of health care-related costs such as medicines, parking, and meal costs during hospital visits. Living in a rural area and travelling to urban hospitals for treatment accumulated expenses “especially on a multiday stay.” Caregivers were financially strained when they gave up work to manage their child’s complex care. Some were forced to “dip into their savings,” “shut down the business” or declare “bankruptcy.” Single parents struggled financially and had to rely on government income support.

Debilitating Exhaustion

Participants felt overcome by burnout and unable to continue when they had to provide a high level of care for their child such as catheterizing their infant child by hand frequently. Some participants struggled to maintain the routine and rigor of carrying out peritoneal dialysis at home (monitoring peritoneal dialysis machines and administering the treatment). Caregivers with their own disabilities or health conditions (e.g., depression) felt overwhelmed, fatigued, “mentally not there” and struggled to provide care for their child.

Asymmetry of Responsibility

Some caregivers experienced feelings of loneliness and a lack of support from their partners when they assumed the sole responsibility of accessing care for their child. The unequal responsibility of their duties increased their caregiving burden. They found it “very difficult to” bear the sole responsibility of care such as keeping track of their child’s “blood reports, medications, doctors’ letters,” in addition to their family responsibilities. Some caregivers shouldered the entire burden of care as they lacked trust in their partners, perceiving them incapable of handling the pressures of caregiving or lacking understanding of their child's care processes.

Intensifying Strain on Family

Uprooting to Relocate

Caregivers from rural or remote areas often experienced family disruptions when staying away from home for their child's frequent treatments (such as hospitalizations for infections or catheterizations). The children, including siblings, struggled to “cope well” when “the family was separated.” Relocating for improved access to specialist care presented challenges, such as securing immediate employment and reorganizing their family.

Sibling Stress and Neglect

Participants felt that caring for their child with CKD often led to neglect of their siblings. Siblings were sometimes “dragged” to medical appointments or caregivers “left them” in the care of family members. When the child (patient with CKD) was going through a crisis, the siblings “received no support” because there was “no time” or “kid appropriate resources” to explain what was going on. Deprioritizing the needs of the siblings caused “a lot of imbalances in the family” affecting relationships, causing behavioral problems (in the children) and psychosocial issues including “guilt,” “worry,” “sadness,” “anxiety” and “a lot of anger.” One participant reported that her son (sibling of the patient) “hits, punches and threatens to pull the cord (treatment lines) out so he (patient) dies.”

Depending on Family Support

Some participants described the vital role played by their extended family members, especially the patient’s grandparents, who contributed by actively engaging in the patient’s care, providing emotional support, financial aid, and looking after the patient’s siblings. During stressful times, such as when patients were newly diagnosed or underwent a transplant, participants “leaned on” family and a “few friends” to take “a break,” to recharge and resume their caring responsibilities. One participant who was new to the country encountered cultural and language barriers in accessing care and felt isolated without family support.

Building Resilience and Stability

Empowerment Through Education

As a result of the education, training, and information that the hospital provided, some caregivers felt capable of managing their child’s treatment. They reported that the nurses “made sure” the participants could independently access and administer their child’s treatment such as home dialysis. Caregivers new to the system initially struggled to navigate health care services. However, as the patients reached stable stages and caregivers gained more information, they became familiar with the system and felt more settled.

Confidence in Technical and Medical Support

Some participants expressed confidence in their ability to care for their children, attributing this to effective hospital facilities and systems, or since their child (in the stage of CKD) was now “relatively well.” They felt the information on their child available through the hospital “portal” helped them “keep up with their appointments and treatment.” Participants trusted the medical support they received, and the nurses ensured the caregivers knew how to contact them “for emergencies.” One participant who had a disability herself, reported that the regional hospital nurse and social worker “made sure she (caregiver) was okay” while monitoring her child receiving albumin infusions.

Discussion

Caregivers of children with CKD felt disempowered while accessing health care for their child. Unable to obtain a timely diagnosis and referral to specialist care, they were uncertain about the processes of care or the treatment their child should be receiving. Trust in clinicians was undermined by perceived inconsistencies in the information provided and disjointed care across specialties. The burden of caregiving was intensified by the financial strain, ongoing fatigue, and overwhelming responsibility of care. Caregivers felt frustrated by the systemic impediments to accessing care due to inflexible appointment scheduling systems, lack of equipment and expertise specific to the needs of children with CKD, and hard-to-navigate financial support systems. Some participants felt that they did not receive the information and support from the allied health care professionals (e.g., social workers) to access these services. The strain of caring impacted the whole family with some caregivers uprooting their family and relocating to access necessary care. While balancing the care of the child with CKD, the needs of the siblings were often deprioritized, and some caregivers were forced to rely on extended family members for support. Participants who were new to the country (recent immigrants) and lacked family support, faced language and cultural barriers while navigating the health care system. Despite these barriers, caregivers gained a sense of agency over time. They felt empowered to access care by acquiring knowledge about the disease and the health care system and building confidence through technical and medical support.

Although our findings were broadly consistent across all participants, the differences in perspectives on accessing care were influenced by the child's health needs, the severity and stage of CKD, the socioeconomic status of the caregiver, and geographical factors. Compared to children with low care needs (such as early CKD stages or stable post-transplant), caregivers of children with complex care needs faced greater challenges in accessing care as well as higher disease and treatment burden, which strained their ability to sustain care. The participants were frustrated when they were unable to establish eligibility for support in income support systems, which lacked a category for their child’s rare disease or complex condition. Caregivers, most of whom were mothers in this study, conflicted with their partners over sharing the responsibilities of accessing care. Single mothers were burdened with the strain of single-handedly facing the responsibilities of caring and financial hardships and had to rely on income support. Disparities in access to care were exacerbated for families living in rural areas often because of prohibitive costs of travel and accommodation incurred while accessing services, limited availability of local pediatric facilities and a lack of local medical expertise in pediatric nephrology. Fragmented coordination and communication among the care teams emerged as notable impediments to accessing health care among those navigating multiple care providers (e.g., rural and metropolitan hospitals, or across several specialists).

Our findings are largely reflective of the conceptual frameworks of access to care and encompass the dimensions of abilities to provide service and the abilities to seek and generate access25 (Supplementary Figure S2). We elucidated structural barriers extrinsic to the caregivers that represented the dimensions of provision of health care services, including absence of necessary care services for pediatric CKD, conflicting medical advice, and inaccessible income support systems. Simultaneously, we emphasized challenges intrinsic to caregivers, including financial stress (inability to be employed, single parents, inability to pay for care products, and/or out of pocket costs), insufficient information on CKD, and inability to advocate for their child. These barriers impacted the ability to seek and generate access to care. This underscores the need for empowering individual caregivers and addressing both intrinsic and extrinsic barriers.

The barriers in access to care identified in this study have also been reported by parents and caregivers of children with other chronic conditions, including cancer, asthma, and diabetes.26, 27, 28 Studies in children with chronic diseases mostly from high-income countries including the USA, Canada, Norway, New Zealand, and Sweden show similar results.26, 27, 28 Patients with rare and complex diseases typically require specialized care that may be lacking particularly in rural settings. In addition, there is a lack of coordination between different care settings (e.g., rural vs. metropolitan hospitals) and limited supportive services that can alleviate the burden and economic strain experienced by caregivers.29, 30, 31, 32 Studies specifically in CKD highlighted the financial distress among caregivers caused by the demands of caregiving and the need for access to psychosocial and education support.5,9,33, 34, 35 In our study, we have identified a wide range of barriers that impact the quality of care that the children receive, the hardships experienced by caregivers from disadvantaged backgrounds that limit their capacity to provide care, and the profound consequences this may have for the whole family. Our study supports previous findings that indicate caregivers of children with chronic illnesses can neglect their own self-care, including getting rest, exercising or forgetting to take medications. This can compromise their caregiving abilities.36 Similar to our study, siblings of children with chronic conditions are known to experience more emotional, behavioral, and social issues compared to siblings of healthy children.37

This multicenter study conducted across 5 of the largest pediatric kidney units in Australia includes caregivers of children from all stages of CKD and provides in-depth and diverse insights from a large sample of caregivers who were purposively selected to include a range of demographic characteristics and conditions until data saturation. However, our study has some potential limitations. To avoid cultural and linguistic misinterpretation, we invited only English-speaking families. The study was conducted in Australia and the transferability of our findings to other populations is uncertain; however, there is consistency between our results with similar studies on caregiver perspectives on access to care conducted in other countries.28, 29, 30, 31 Our study highlighted experiences of caregivers from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as delayed diagnosis, treatment burden, siblings neglect, spousal tension, and fragmented care coordination. These issues are universal among caregivers of CKD patients.5,38,39 However, experiences of financial strain vary, with caregivers from higher-income households perceiving more choice and control over their child’s care9

Suggestions for improving access to care from the perspective of caregivers of children with CKD are provided in Table 3. Optimizing caregiver efficacy by building caregiver and patient health literacy, addressing barriers to health care services, enhancing communication with and from health providers, facilitating financial support, and improving care coordination is imperative for the sustenance of care across the life course of the child. We suggest providing information and education to assist newly diagnosed patients, enhancing caregiver-provider communication so that caregivers have a voice, feel listened to, and are treated with empathy and care. Information about CKD and complex treatment processes, such as dialysis and transplant, should be presented in easy-to-understand and culturally sensitive language from trusted sources for both adults and children.

Table 3.

Suggestions for improving access to health care for children with chronic kidney diseasea

| Address health literacy |

|

| Improve access to care through E-health |

|

| Ensure financial support and reimbursements are sufficient, easy to access and provided in a timely manner |

|

| Improve care coordination |

|

| Foster effective communication between children with CKD/parents and clinicians |

|

| Enable social connectedness and caregiver support |

|

CKD, chronic kidney disease; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Suggestions based on the perspectives of caregivers in the study and contributions from the author.

Technologies that can improve the availability and accessibility of health services among children with CKD must be explored. For example, not all hospitals are equipped with technology that allows caregivers to book their own appointments or easy access to their child’s medical test results. Improving access to these technologies is crucial for enhancing the overall health care experience. Strategies and models of care that use digital health technologies, such as mobile health applications, telemedicine, and electronic health records, have been adopted in chronic diseases including asthma and cancer.40, 41, 42 The use of eHealth to augment symptom awareness and management in pediatric asthma have been investigated and found to be technically and clinically feasible, enabling remote care, and beneficial for health outcomes and utilization of required health care. Caregivers of children with cancer benefited from health technologies such as web-based interventions for pain medication optimization, self-guided behavioral and education sessions, smart phone applications, online groups, and telehealth.41,42 In adults with CKD, particularly in patients receiving dialysis, remote patient monitoring (that uses computer systems or software applications to transfer patient-generated data to health professionals) was found to be useful in empowering patients in self-care while providing health care teams with valuable information about the patient’s heath. Remote patient monitoring also helped patients opt for home dialysis by reducing treatment related anxiety.43

Continued advocacy for children with CKD within the complex and sometimes rigid welfare systems needed to support families is recommended to facilitate timely access to income and disability support, to reduce financial stress and allow families to focus on other priorities and challenges. At the local level, ensuring timely, consistent, and appropriate reimbursements of costs of care and out of pocket costs (e.g., with meal vouchers and travel concessions) is required. The provision of a coordinator or patient navigator akin to a nurse or care coordinator is suggested to help guide caregivers navigate complex systems and fragmented health care. Patient navigators have demonstrated effectiveness in increasing screening rates, improving adherence to recommended care and enhancing processes of care in patients with cancer, diabetes, and multiple chronic conditions.44, 45, 46 Such coordinators facilitate children’s care by facilitating individualized treatment plans and education for caregivers and families.47 In addition, supporting caregivers by assisting family members, including the patient’s siblings, may help alleviate family tensions and burdens, improve outcomes for the children (patients) and siblings, offer financial relief, save time, and enhance their quality of life.

To enable shared decision making and patient-centered care, enduring relationships between clinicians and patients must be facilitated and fostered over the life of the patient. Provision of clinician training on effective communication to build trust, empower caregivers, and provide individualized care for improved outcomes is imperative. Social support for alleviating the pressures of caregiving through online internet-based health technologies, community groups, and peer networks is necessary for caregivers who are isolated by the burden of care due to the disease and treatment of CKD. Social connectedness was found to be beneficial in providing psychosocial support and reducing the adverse effects of social isolation among caregivers with chronic diseases.41 A supportive community can help prevent caregiver isolation and enhance their ability to manage their child’s condition.48 Further research needs to be carried out to explore models of care that improve access and outcomes for children across all stages of CKD.

Conclusion

CKD in children presents unique challenges for disadvantaged caregivers in accessing care, including lack of information, limited access to specialized care, financial stress, and fragmented coordination. These issues may delay treatment leading to poor health outcomes. Multifaceted strategies are needed to improve health accessibility and close the health gaps in children with CKD.

Appendix

List of NAVKIDS2 Trial Steering Committee

Germaine Wong (Co-chair), Centre for Kidney Research at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Carmel Hawley (Co-Chair), Princess Alexandra Hospital, the Translational Research Institute and Australasian Kidney Trials Network, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; Allison Tong, Sydney School of Public Health, The University of Sydney; Amanda Walker, Department of Nephrology, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia; Amelie Bernier-Jean, University of Montreal, Canada; Anita van Zwieten, Centre for Kidney Research at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Anna Francis, Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service, Brisbane, Australia; Armando Teixeira-Pinto, Centre for Kidney Research at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Alistair Mallard, Australasian Kidney Trials Network, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; Chandana Guha, Centre for Kidney Research at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney Australia; Charani Kiriwandeniya, Australasian Kidney Trials Network, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; David Johnson, Princess Alexandra Hospital, the Translational Research Institute and Australasian Kidney Trials Network, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; Deirdre Hahn, Centre for Kidney Research at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia; Donna Reidlinger, Australasian Kidney Trials Network, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; Elaine Pascoe, Australasian Kidney Trials Network, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; Elizabeth Ryan, QCIF Facility for Advanced Bioinformatics and Australasian Kidney Trials Network, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; Fiona Mackie, Department of Renal Medicine, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, Sydney, Australia; Hugh J McCarthy, Centre for Kidney Research at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Department of Renal Medicine, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, Sydney, Australia; Jonathan Craig, College of Medicine and Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia; Julie Varghese, Australasian Kidney Trials Network, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; Kirsten Howard, Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Liza Vergara, Australasian Kidney Trials Network, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia; Luke Macauley, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Martin Howell, Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Michelle Irving, The University of Sydney, Sydney Australia; Nicholas Larkins, Perth Children’s Hospital, Perth, Australia; Patrina Caldwell, Centre for Kidney Research at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead and Discipline of Child and Adolescent Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Rabia Khalid, Centre for Kidney Research at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia; Reg Woodleigh, Prostate and Breast Cancer Foundation (CanCare), Sydney, Australia; Sean Kennedy, Department of Renal Medicine, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, Sydney, Australia; Shilpanjali Jesudason, Department of Renal Medicine, Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, Australia; Simon Carter, Department of Nephrology, Royal Children’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia; Stephen Alexander, Centre for Kidney Research at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia; Steve McTaggart, Children’s Health Queensland Hospital and Health Service and The University of Queensland, Australia.

Disclosure

DWJ is funded by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Leadership Investigator Grant. DWJ has received consultancy fees, research grants, speaker’s honoraria and travel sponsorships from Baxter Healthcare and Fresenius Medical Care; consultancy fees from Astra Zeneca, Bayer, and AWAK; speaker’s honoraria from ONO and Boehringer Ingelheim & Lilly; and travel sponsorships from Ono and Amgen. KM is on the editorial board of Kidney International Reports as statistical reviewer. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The study is a part of the NAVKID2 trial and funded by a National Health and Medical Research Council fund under the category: Medical Research Future Fund Targeted Call for Research: Rare Cancers, Rare Diseases and Unmet Need Initiative (APP1170021). The trial was registered on the Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12618001152213.

Footnotes

Interview Guide for Caregivers.

Figure S1. Levesque’s conceptual framework of access to health care.

Figure S2. Mapping themes to Levesque’s conceptual framework of access to care.

Contributor Information

Chandana Guha, Email: chandana.guha@sydney.edu.au.

NAVKIDS2 trial steering committee:

Germaine Wong, Carmel Hawley, Allison Tong, Amanda Walker, Amelie Bernier-Jean, Anita van Zwieten, Anna Francis, Armando Teixeira-Pinto, Alistair Mallard, Chandana Guha, Charani Kiriwandeniya, David Johnson, Deirdre Hahn, Donna Reidlinger, Elaine Pascoe, Elizabeth Ryan, Fiona Mackie, Hugh J. McCarthy, Jonathan Craig, Julie Varghese, Kirsten Howard, Liza Vergara, Luke Macauley, Martin Howell, Michelle Irving, Nicholas Larkins, Patrina Caldwell, Rabia Khalid, Reg Woodleigh, Sean Kennedy, Shilpanjali Jesudason, Simon Carter, Stephen Alexander, and Steve McTaggart

Supplementary Material

Interview Guide for Caregivers. Figure S1. Levesque’s conceptual framework of access to health care. Figure S2. Mapping themes to Levesque’s conceptual framework of access to care.

References

- 1.Kaspar C.D.W., Bholah R., Bunchman T.E. A review of pediatric chronic kidney disease. Blood Purif. 2016;41:211–217. doi: 10.1159/000441737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harshman L.A., Zepeda-Orozco D. Genetic considerations in pediatric chronic kidney disease. J Pediatr Genet. 2016;5:43–50. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1557111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong C.J., Moxey-Mims M., Jerry-Fluker J., Warady B.A., Furth S.L. CKiD (CKD in children) prospective cohort study: a review of current findings. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:1002–1011. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Zwieten A., Caldwell P., Howard K., et al. NAV-KIDS2 trial: protocol for a multi-centre, staggered randomised controlled trial of a patient navigator intervention in children with chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:134. doi: 10.1186/s12882-019-1325-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tong A., Lowe A., Sainsbury P., Craig J.C. Parental perspectives on caring for a child with chronic kidney disease: an in-depth interview study. Child Care Health Dev. 2010;36:549–557. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Penna F.J., Elder J.S. CKD and bladder problems in children. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2011;18:362–369. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lalji R., Francis A., Wong G., et al. Disparities in end-stage kidney disease care for children: a global survey. Kidney Int. 2020;98:527–532. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2020.04.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crews D.C., Bello A.K., Saadi G. World Kidney Day Steering Committee. Burden, access, and disparities in kidney disease. J Nephrol. 2019;32:1–8. doi: 10.1007/s40620-019-00590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medway M.B., Tong A.P., Craig J.C.P., et al. Parental perspectives on the financial impact of caring for a child with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65:384–393. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harambat J., Ekulu P.M. Inequalities in access to pediatric ESRD care: a global health challenge. Pediatr Nephrol: Berlin: West. 2016;31:353–358. doi: 10.1007/s00467-015-3263-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francis A., Didsbury M.S., van Zwieten A., et al. Quality of life of children and adolescents with chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104:134–140. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2018-314934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Didsbury M.S., Kim S., Medway M.M., et al. Socio-economic status and quality of life in children with chronic disease: a systematic review. J Paediatr Child Health. 2016/12/01;52:1062–1069. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scholes-Robertson N., Gutman T., Howell M., Craig J.C., Chalmers R., Tong A. Patients’ perspectives on access to dialysis and kidney transplantation in rural communities in Australia. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7:591–600. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braveman P., Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):19–31. doi: 10.1177/00333549141291S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carey T.A., Wakerman J., Humphreys J.S., Buykx P., Lindeman M. What primary health care services should residents of rural and remote Australia be able to access? a systematic review of “core” primary health care services. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013/05/17;13:178. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tong A.P., Sainsbury P.P., Chadban S.P., et al. Patients’ experiences and perspectives of living with CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:689–700. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anita V.Z. Investigating the relationship between socioeconomic status and health across the life-course and among people with chronic disease. https://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/handle/2123/23554

- 18.Tong A., Sainsbury P., Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guha C., Khalid R., van Zwieten A., et al. Baseline characteristics of participants in the NAVKIDS(2) trial: a patient navigator program in children with chronic kidney disease. Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38:1577–1590. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05772-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Zwieten A., Ryan E.G., Caldwell P., et al. NAVKIDS(2) trial: a multi-centre, waitlisted randomised controlled trial of a patient navigator intervention in children with chronic kidney disease - statistical analysis plan and update to the protocol. Trials. 2022;23:824. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06783-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butcher N.J., Monsour A., Mew E.J., et al. Guidelines for reporting outcomes in trial reports: the CONSORT-outcomes 2022 Extension. JAMA. 2022;328:2252–2264. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D. CONSORT. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:834–840. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeman M., Myaskovsky L. An overview of disparities and interventions in pediatric kidney transplantation worldwide. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;30:1077–1086. doi: 10.1007/s00467-014-2879-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Pádua Paz I., Konstantyner T., de Castro Cintra Sesso R., de Xavier Pinto C., de Camargo M., Nogueira P. Access to treatment for chronic kidney disease by children and adolescents in Brazil. Pediatr Nephrol. 2021;36:2827–2835. doi: 10.1007/s00467-021-05009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levesque J.-F., Harris M.F., Russell G. Patient-centred access to health care: conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding L., Szymczak J.E., Evans E., et al. Factors that contribute to disparities in time to acute leukemia diagnosis in young people: an in depth qualitative interview study. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:531. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09547-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Siminerio L.M., Albanese-O’Neill A., Chiang J.L., et al. Care of young children with diabetes in the child care setting: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2834–2842. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ardura-Garcia C., Blakey J.D., Cooper P.J., Romero-Sandoval N. Caregivers’ and healthcare professionals’ perspective of barriers and facilitators to health service access for asthmatic children: a qualitative study. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2021;8 doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baumbusch J., Mayer S., Sloan-Yip I. Alone in a crowd? Parents of children with rare diseases’ experiences of navigating the healthcare system. J Genet Couns. 2019;28:80–90. doi: 10.1007/s10897-018-0294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Currie G., Szabo J. Social isolation and exclusion: the parents’ experience of caring for children with rare neurodevelopmental disorders. Int J Qual Stud Health Well Being. 2020;15 doi: 10.1080/17482631.2020.1725362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von der Lippe C., Neteland I., Feragen K.B. Children with a rare congenital genetic disorder: a systematic review of parent experiences. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022/10/17;17:375. doi: 10.1186/s13023-022-02525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacob S.A., Bouck J., Daas R., Jackson M.D., LaMotte J.E., Carroll A.E. Understanding caregiver burden with accessing sickle cell care in the Midwest and their perspective on telemedicine. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23:500. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09383-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang Y., Gutman T., Tong A., et al. Child and caregiver perspectives on access to psychosocial and educational support in pediatric chronic kidney disease: a focus group study. Pediatr Nephrol: Berlin: West. 2023;38:249–260. doi: 10.1007/s00467-022-05551-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kish A.M., Newcombe P.A., Haslam D.M. Working and caring for a child with chronic illness: a review of current literature. Child Care Health Dev. 2018;44:343–354. doi: 10.1111/cch.12546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cardinali P., Migliorini L., Rania N. The caregiving experiences of fathers and mothers of children with rare diseases in Italy: challenges and social support perceptions. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1780. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hughes R.G., editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Rockville (MD): April 2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quintana M., Chakkera M., Ravi N., et al. The other sibling: mental health effects on a healthy sibling of a child with a chronic disease: a systematic review. Cureus. 2022;09/11 doi: 10.7759/cureus.29042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tong A., Lowe A., Sainsbury P., Craig J.C. Experiences of parents who have children with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics. 2008;121:349–360. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-3470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warady B.A., Feldman D.L., Bell L.E., et al. Improving clinical care for children with CKD: A report from a National Kidney Foundation scientific workshop. Am J Kidney Dis. 2023;81:466–474. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2022.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van der Kamp M., Reimering Hartgerink P., Driessen J., Thio B., Hermens H., Tabak M. Feasibility, efficacy, and efficiency of eHealth-supported pediatric asthma care: six-month quasi-experimental single-arm pretest-posttest study. JMIR Form Res. 2021;5 doi: 10.2196/24634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J., Lin L., Gao Y., Wang W., Yuan L. Interventions and strategies to improve social support for caregivers of children with chronic diseases: an umbrella review. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.973012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delemere E., Maguire R. The role of Connected Health technologies in supporting families affected by paediatric cancer: A systematic review. Psychooncol. 2021;30:3–15. doi: 10.1002/pon.5542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henriette Tyse N., Lien N., Rigmor C.B. Effect of remote patient monitoring for patients with chronic kidney disease who perform dialysis at home: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2022;12 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-061772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McBrien K.A., Ivers N., Barnieh L., et al. Patient navigators for people with chronic disease: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carter N., Valaitis R.K., Lam A., Feather J., Nicholl J., Cleghorn L. Navigation delivery models and roles of navigators in primary care: a scoping literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:96. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-2889-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kilbourne A.M., Hynes D., O’Toole T., Atkins D. A research agenda for care coordination for chronic conditions: aligning implementation, technology, and policy strategies. Transl Behav Med. 2018;8:515–521. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibx084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith L.R., Clayton M.L., Woodell C., Mansfield C. (NC): RTI Press; Research Triangle Park: April 2017. The Role of Patient Navigators in Improving Caregiver Management of Childhood Asthma. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith A.B., Jones C.D. The role of community support in caregiver well-being. J Fam Health. 2017;25:234–245. doi: 10.1234/jfh.2017.254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Interview Guide for Caregivers. Figure S1. Levesque’s conceptual framework of access to health care. Figure S2. Mapping themes to Levesque’s conceptual framework of access to care.