Significance

This study evaluates how well convenience samples of political practitioners and laypeople can predict the effectiveness of 172 persuasive messages. Both groups performed barely better than chance, with practitioners performing no better than laypeople. This suggests practitioners may have limited ability to predict which messages persuade voters, consistent with the complexity of persuasive phenomena. The results raise questions about the potential for elites to easily affect public opinion with persuasive messages.

Keywords: political persuasion, forecasting, issue advertising

Abstract

Do political practitioners have good intuitions about how to persuade the public? Longstanding theories that political elites’ messages have large effects on public opinion and the large sums spent to secure some practitioners’ messaging advice suggest they should. However, findings regarding the surprising limits of expert forecasts in other domains suggest they may not. In this paper, we evaluate how well political practitioners can predict which messages are most persuasive. We measured the effects of messages about 21 political issues using a large-sample survey experiment ( respondent-message observations). We then asked both political practitioners ( practitioners, predictions) and laypeople ( respondents, predictions) to predict the efficacy of these messages. The practitioners we surveyed ranged widely in their experience and expertise with persuasive message design. We find that: (a) political practitioners and laypeople both performed barely better than chance at predicting persuasive effects; (b) once accounting for laypeople’s inflated expectations about the average size of effects, practitioners did not predict meaningfully better than laypeople; (c) these results held even for self-identified issue experts and highly experienced practitioners; and (d) practitioners’ experience, expertise, information environment, and demographics did not meaningfully explain variation in their accuracy. Our findings have theoretical implications for understanding the conditions likely to produce meaningful elite influence on public opinion as well as practical implications for practitioners.

Longstanding theories argue that elite rhetoric impacts public opinion (e.g., ref. 1). Political organizations and elites appear to care deeply about accomplishing this goal: For instance, during the 108th Congress, Falk et al. (2) estimated that interest groups spent $625 million on print and television issue advertising (2023 dollars). Reflecting this, political organizations likewise spend large sums hiring communications consultants to help them persuade voters (3).

Scholarship’s robust finding that political elites have the potential to persuade the public sits at odds with findings that their real-world persuasion efforts often have limited effects (e.g., refs. 4–6). In light of the apparent ease with which elites can sometimes impact mass opinion, why do they often fail to do so in practice?

Prior research suggests multiple answers to this puzzle, such as the role of elite competition (7). In this paper, we suggest another, complementary explanation: political elites’ intuitions about how to devise messages to persuade the public may be poor.

A large body of research finds that the persuasive impact of political messages depends, among other factors, on the specific messages used (1). A common assumption in analyses of political elites is that they are rational actors who act optimally, and so we might expect political elites to use the most persuasive possible messages. However, despite that elites can powerfully influence public opinion with certain messages in some instances [especially when the messaging environment is not competitive (7)], little research in political science has studied why and how elites choose their strategies for influencing the public, such as why they choose which messages to deploy.

We argue that political elites are likely to have quite poor intuitions about which messages persuade the public. We argue that this should be expected simply because human beings are generally quite poor at predicting complex phenomena such as persuasion. In particular, a growing interdisciplinary literature on forecasting has shown that people—including experts and academics—are poor at predicting the effects of interventions to change behavior, such as which text messages will most effectively encourage vaccinations, or which advertisements will most increase sales (8–13). This includes research on policy experts, who appear to only rarely accurately forecast world events (14) or the effects of nongovernmental organization interventions intended to increase political accountability (15).*

Recent research on the effects of persuasive interventions also offers some hints consistent with this possibility, as it finds that typical persuasive efforts have very small effects, but that these effects are larger when experiments are used to find persuasive messages and subpopulations that were not identifiable in advance (4, 17). These findings suggest that the very small effects of real-world persuasive interventions may only be partly due to fundamental limitations on how persuadable voters are and may in part be due to the limited abilities of elites to forecast which messages are most persuasive.

In this paper, we examine the quality of political practitioners’ forecasts about how well various messages persuade the public. To do so, we first sourced and lightly edited text-based political messages which were used by real political elites (e.g., politicians and interest groups) to support or oppose each of 21 political issues (total messages).† Next, to measure the effects of these messages, we conducted a large-scale survey experiment where we randomized each of participants to a treatment group which saw one of these messages or a control group which saw none of them, and then asked them a survey question about their opinion on that issue. Each participant participated in experiments on three different issues, so we have a total of respondent-message observations (each of which is associated with one issue and one of the 172 messages or a control). We use this data to estimate the persuasive effect of each of the 172 messages. Finally, we asked both political practitioners ( practitioners, 91% of whom stated that they work or have worked in developing messages; predictions) and laypeople ( respondents, predictions) to predict the efficacy of these messages. This sample size of practitioner predictions compares favorably to other recent studies, such as ref. 8, which had predictions from 24 experts, and ref. 9, which had predictions from 237 experts. Our sample of political practitioners was also diverse along multiple dimensions, including in the extent of their experience and expertise (described in more detail later). Our substantial sample size and diverse sample allow us to more precisely estimate whether subgroups of practitioners are more accurate at forecasting than others, and therefore to test alternative accounts of what might drive variation in accuracy (e.g., expertise or experience).

Our findings suggest that political practitioners are universally fairly poor at predicting which messages persuade the public. In particular, we found that: 1) political practitioners and laypeople both performed barely better than chance at predicting persuasive effects; 2) once accounting for laypeople’s inflated expectations about the average size of effects, practitioners did not predict meaningfully better than laypeople; 3) these results hold even for self-identified issue experts, highly experienced practitioners, and those who expressed confidence in their forecasts; and 4) consistent with the generalizability of our conclusions, practitioners’ experience, expertise, information environment, and demographics did not meaningfully explain variation in their accuracy.

As we discuss in the conclusion, our findings have both practical and theoretical implications. Theoretically, our findings suggest conditions that may underpin the potential for meaningful elite influence on public opinion: Elites may often choose persuasive messages poorly, limiting their influence. The robustness of our conclusions across subgroups of practitioners suggest that our findings do not reflect a lack of expertise or experience on the part of political practitioners in general or in our sample, but rather may reflect fundamental limits on most human beings’ ability to forecast complex phenomena such as persuasion. On a practical level, our findings resonate with findings from recent research on the value of experimentation (17): Some messages are meaningfully more persuasive than others, but if practitioners cannot predict which are more persuasive, it is in their interest to gather data (e.g., from experiments) that can identify them. This suggests that gathering experimental data to learn what works, rather than relying on political practitioners’ limited ability to forecast what is persuasive, may be most useful for political practitioners.

Materials and Methods

Data from this project comes from four sources. This research was reviewed and approved by the Yale University and University of California, Berkeley Human Subjects Committees. All participants provided informed consent.

Messages.

First, we collected 172 text-based political messages about 21 distinct issues. 166 of these messages were used by political practitioners to persuade the mass public to support their cause while we drafted the remaining six (so that there would be at least 3 messages on each side of each issue). These messages were gathered from sources such as communications guides published by various advocacy organizations or the Twitter accounts of prominent politicians. This increases the ecological validity of our study because we use the kinds of messages that real political organizations and elites use—they are indeed messages they have used.

We note that it is possible we may have found different results with the use of video-based messages instead of text-based messages. With that said, Wittenberg et al. (18) find that text-based political messages have fairly similar persuasive effects to video-based political messages.‡

We lightly edited the messages for length and consistency.§Table 1 gives examples of the messages and sources we used for the “legalizing marijuana” policy. (In the experiments, the messages were not attributed to the sources, to avoid potential source cue effects.)

Table 1.

Sample text-based political messages used in study

| Message | Source |

|---|---|

| (a) Example messages against marijuana legalization | |

| Legalizing marijuana could lead us to be soft on crime. A lot of times when you look at the underlying charge—it wasn’t just that they smoked a joint, it’s that they smoked a joint and then beat an elderly woman over the head with a pistol. | Senate candidate J. D. Vance (via the recount twitter) |

| We should not be legalizing marijuana. The drug cartels out of Mexico have absolutely wrought havoc throughout California forests and 27 other states throughout our great nation by growing black market illegal unregulated cannabis. | American Legislative Exchange Council |

| Today, marijuana trafficking is linked to a variety of crimes, from assault and murder to money laundering and smuggling. Legalization of marijuana would increase demand for the drug and almost certainly exacerbate drug-related crime, as well as cause a myriad of unintended but predictable consequences. | The Heritage Foundation |

| Legalization of cannabis for adult use is associated with increased traffic fatalities, exposures reported to poison control (including infants and children), emergency department visits, and cannabis-related hospitalizations. Furthermore, the increasing prevalence of cannabis use in pregnant people is most concerning. | The American Medical Association |

| (b) Example Messages For Marijuana Legalization | |

| Black and white people use marijuana at the same rates, but Black people are six times more likely to go to jail for it. It makes no sense. We should be proud to vote to legalize marijuana and wipe the slate clean for marijuana-related convictions and arrests. | Senate candidate Tim Ryan |

| Polls show that a strong and growing majority of Americans agree it is time to end cannabis prohibition. Nationwide, a recent Gallup poll found that 66% support making marijuana use legal for adults. | Marijuana Policy Project |

| Hundreds of thousands of Americans are arrested each year for marijuana-related offenses, the vast majority of which are for simple possession. By legalizing marijuana, government resources could be better spent on things like testing untested rape kits or investing in human needs such as mental health counseling, substance abuse treatment, and activities for at-risk teens. | Marijuana Policy Project |

| America’s nearly 100-y experiment with cannabis criminalization has been an abject failure. | NORML |

Note: Messages were typically edited slightly and are not always verbatim quotes from the source.

Message Effects.

Second, we conducted a survey experiment to estimate the persuasive effect of each of these 172 messages. We recruited a sample of 21,247 respondents on Lucid who passed pretreatment attention checks. SI Appendix gives the survey questions. We began the survey by measuring baseline covariates and demographics. We then randomly assigned respondents to one of 21 issues (SI Appendix, Table S1). Within each issue, we next randomly assigned respondents to a control group that did not read a persuasive message on that issue or to a treatment group that did read a randomly selected persuasive message on that issue. We then asked all respondents an issue-specific policy support question. For example, among those respondents randomly assigned to the topic of healthcare, respondents in the treatment group might have been randomly assigned to read the statement “Seniors should not have to choose between buying groceries and getting the medicine they need to survive” while respondents in the control condition would read no persuasive message. All respondents assigned to the healthcare issue topic were then asked whether they support or oppose “allowing Medicare, the government’s health insurance program for those over 65, to negotiate lower drug prices with drug companies.” The response to this question is the outcome measure we use to estimate the persuasive effect of the statement. Each respondent repeated this exercise three times over the course of the survey.

To estimate message-level treatment effects, we first stacked the data at the respondent-message level. Separately by issue domain, we regressed an indicator for message support on indicators for each message within that domain (with the control group as the base category) and pretreatment covariates selected using a first-stage Lasso regression (19).¶ Although the sample was fairly representative on observable demographic characteristics to begin with, when estimating treatment effects, we weight it to match the demographic composition of the general population according to the 2022 Cooperative Election Study (20) using ref. 21 (SI Appendix, Table S2).# This results in an estimated treatment effect and associated SE for the effect of each message on increasing or decreasing support for that message’s policy domain. This treatment effect estimate is the target we asked political practitioners and laypeople to predict.

The average treatment effect estimate of the messages was 3.4 percentage points in the intended direction of the message (95% CI 2.9 to 3.8 percentage points). There is also meaningful dispersion in the effects of the messages over and above what would be expected from sampling error; SI Appendix, Fig. S1 shows that we observed far more variation in the estimated effects of the messages than we would expect to see were the true treatment effects of the messages identical within issue-side.

Practitioner Forecasts.

Our third data source is a survey of political practitioners. We gathered email information for 21,459 political practitioners and invited them to participate in an online survey.‖ 1,524 political practitioners responded to the survey—a 7.1% response rate, which is similar to other surveys of political elites (e.g., ref. 22). SI Appendix gives the survey questions.

This population is highly relevant for understanding how political organizations develop and deploy messages to persuade the public: 91% of respondents stated they work on developing messages used for political persuasion or issue advocacy,** although there is meaningful variation in the extent of their expertise and experience.

Various indicators suggest that our sample included many high-level, experienced political practitioners. 65% of respondents have worked in politics for over 10 y and another 18% have worked in politics for 6 to 10 y. 12% have held a managerial role on a candidate campaign or independent expenditure for president.

Additional demographics include that 53% identify as men, and 80% as white. Unfortunately, similar to many political elite surveys, the sample skewed Democratic (e.g., ref. 23): Among respondents, 72% identified as Democrats, 11% as Republican, and 17% as Independent or something else. However, we still have ample numbers of Republican and Independent respondents to allow for subgroup analyses, and our findings are similar among these subgroups.

In summary, the demographics of our survey respondents suggest that we successfully identified and surveyed a population responsible for this task of identifying persuasive political messages. However, we emphasize that there is meaningful variation in expertise and experience in our sample: For instance, only a small minority of the sample (9%) stated that they are not responsible for composing messages at all, while on the other hand, other subsets of the sample have held managerial roles in the upper echelons of political campaigns.

To elicit practitioners’ predictions, we first told them that researchers had recently conducted a large survey of Americans and what baseline support was for a particular policy. We then showed them statements designed to either increase or decrease support for that policy and asked them what percent of survey takers they thought would be persuaded to support the policy after reading each statement. This allows us to estimate each practitioner’s estimate of the persuasive effect of each statement. We repeated this procedure a total of four times for each practitioner across two issues and both the support and oppose side for each issue. If the practitioner self-identified as an expert in a given issue domain, the practitioner would always see that issue as well as a randomly selected second issue.††SI Appendix, Fig. S9 provides an example.‡‡ This resulted in a total of 22,763 predictions from political practitioners.§§ The average within-issue/side SD in practitioners’ predictions was 12.3 percentage points.

Laypeople’s Predictions.

To elicit lay people’s predictions, at the end of the survey used to estimate the message treatment effects, we asked respondents to predict the efficacy of three different messages within one randomly selected issue domain using the same procedure as that used for the practitioner forecasts. These messages were about a distinct issue from the issue on which they were shown messages earlier in the survey. This resulted in 63,442 predictions. The average within-issue/side SD in laypeople’s predictions was 27.6 percentage points.

Results

Message Level (“Wisdom of Crowds”).

We begin by showing the raw data at the message level, examining how well the average forecasts of practitioners and laypeople predict the estimated actual effects of the messages. These “wisdom of crowd” estimates aggregate across many individuals, and so are typically more accurate than any one individuals’ guesses (24). They are therefore likely the best case scenario for finding accurate forecasts: Each individual message’s effects were forecasted by approximately 132 practitioners and 368 members of the mass public on average.

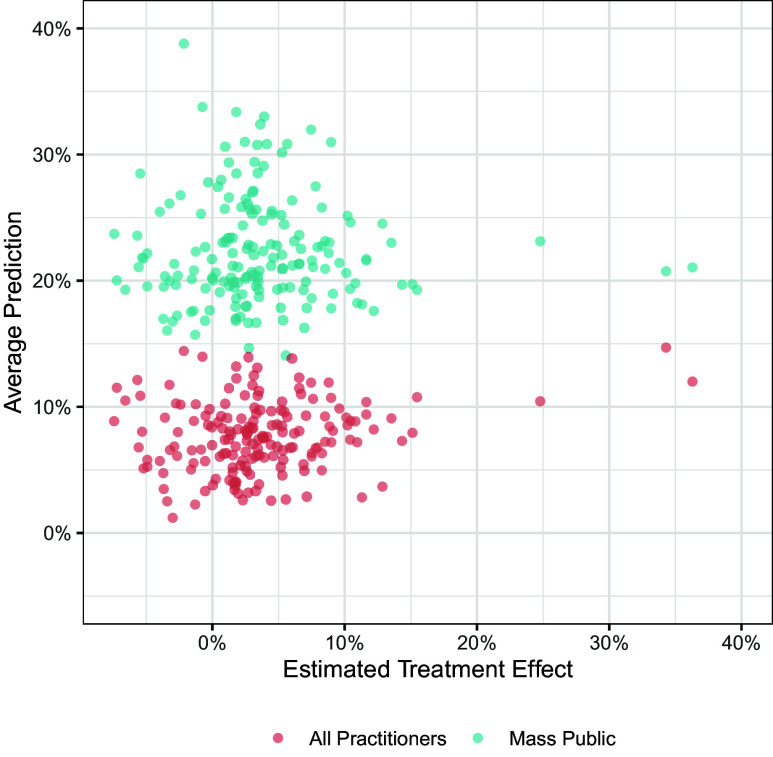

Each point in Fig. 1 corresponds with one of the 172 messages we tested and the average predictions made by either the mass public or political practitioners. The x-axis shows the estimated treatment effect of those messages. The y-axis shows the average predictions that practitioners (red) or the mass public (blue) made about the effects of those messages.

Fig. 1.

Raw Data at the Message Level. Each point corresponds with one of the 172 messages tested, with the estimated treatment effects of those messages shown on the x-axis and the average predictions of either practitioners (red) or the mass public (blue) shown on the y-axis. See SI Appendix, Fig. S3 for results split by issue/side.

Three patterns are readily apparent.

First, the mass public’s predictions (blue dots) are on average much higher than practitioners’ predictions (red dots): The mass public thinks other people are more persuadable than both our treatment effect estimates suggest and than practitioners expect.

Second, though, neither the mass public nor practitioners are very accurate at determining which messages are better than others—a key decision practitioners face when deciding how to persuade. The raw correlation between the mass public’s average predictions and the estimated treatment effect is 0.03. The correlation between the estimated effects and practitioners’ average predictions is 0.20.

Third, although substantively small at 0.20, the correlation is larger for political practitioners than it is for the mass public.

Two weaknesses of these raw correlations are that they do not take into account the sampling variability associated with our estimates of the treatment effects of the messages and they do not control for issue and side. The former issue may attenuate the size of these correlations. However, the latter issue may artificially inflate the correlation. In particular, if practitioners simply understand that persuasion is more difficult on, for example, abortion than on marijuana, the raw correlation across all messages and issues might reflect their knowledge of which issues are more and less difficult to persuade on, rather than their knowledge of which messages are most persuasive within a given issue and side (e.g., which of several messages in favor of marijuana legalization are most effective; the actual task that practitioners working on that issue face).

To address these issues, we run a fixed-effects meta-regression of the practitioners’ average predictions on the estimated treatment effects, with fixed effects for issue by side (i.e., one fixed effect for supportive and another for opposed messages on each issue). This meta-regression takes into account the sampling variability associated with our estimates of the actual effects of the messages.¶¶ In this meta-regression framework, we estimate that the average practitioners’ estimates explain only 4.2% of the variation in true within-issue-side treatment effects. Our best guess is that practitioners do outperform laypeople though; the equivalent number for the mass public is 1.2%, even smaller than the estimate for practitioners. We emphasize that these estimates, already quite small, still dramatically overstate how accurate any individuals are at predicting these effects, as they represent “wisdom of crowds” estimates that average across many people.

Do Individuals Predict Better than Guessing?

We next examine how well individual practitioners and members of the mass public predict the effects of messages by comparing their estimates to random guessing.

To do so, we follow the forecasting literature in computing the root mean squared error of each individual’s forecasts. The root mean squared error is traditionally defined as follows, where the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for individual is computed as a function of their predictions of multiple items and the true effect## of message , :

Adjusting for sampling error and idiosyncratic scale use.

We make two adjustments to avoid “punishing” forecasters for irrelevant aspects of the forecasting exercise.

First, we adjust for the sampling error associated with our estimates of the treatment effects. Our measures of the “true” effects of the messages () are in fact estimates which contain sampling error. To adjust for this sampling error, when computing the estimated error, we therefore subtract a constant , the variance of the estimated treatment effects (Because the effects of each message are estimated using experiments with nearly identical sample sizes, we use a single constant for simplicity). This adjustment follows from the variance sum law. The Adjusted RMSE is therefore:

This adjustment avoids “punishing” the forecasters for errors in the estimates of the treatment effects that arise due to sampling error. This adjustment does not affect inference (e.g., -values), it simply scales down point estimates. All of the RMSE estimates presented in the paper use this adjustment. With this adjustment, were a participant to accurately estimate the true treatment effects, we would estimate an Adjusted RMSE of 0 (We have confirmed this result in simulations).

Second, in some analyses, we also rescale individuals’ estimates, , for respondents’ potentially idiosyncratic uses of the measurement scale. In particular, when individuals select messages for use to persuade on a particular issue in practice, what matters most is arguably their perception of the ranking or relative distance between the effects of the messages, not their expectation about the absolute size of the effects. On the other hand, simply having inaccurate expectations about the average absolute magnitude of treatment effects in survey experiments is mostly irrelevant to how well individuals would select which messages to use in the real world. For instance, if a practitioner understood exactly how much better one message was than another but overestimated the effects that messages have in survey experiments by a factor of five, it might be desirable to not “punish” their predictions for being overly optimistic about the effects messages have in survey experiments in general. Indeed, in the last section, we saw that the mass public in fact did overestimate the magnitude of survey experimental effects in general.

To set aside idiosyncratic uses of the scale, our primary estimates rescale individuals’ predictions on each side of each issue to the average mean of the treatment effects on that issue on that side, and to the estimated SD of the true treatment effects (We estimate the SD of the true treatment effects by again relying on the variance sum law, subtracting the variance due to sampling error from the variance of the point estimates. We estimate the variance of the messages across all 172 messages because we have too few messages within each issue-side to form meaningful estimates of the true variance of the treatment effects by issue-side).

In summary, by using RMSE adjusted for sampling variability, and calculated using a rescaled version of participants’ guesses, we can set aside two major reasons why participants’ forecasts might spuriously appear inaccurate.

Results: Comparison to random guessing.

To test whether participants are able to predict the effects of messages better than guessing, we first compute the adjusted RMSE in the observed data. We then randomly permute each individual participants’ guesses within issue-side. This simulates the null of random guesses within issue-side. We then compute the average adjusted RMSE across all participants.

Fig. 2 shows the results for both the practitioners (A) and the mass public (B). The red line at 0 shows the RMSE we would observe if participants were completely accurate. The blue lines show the RMSE we observed. Finally, the distribution in black shows the distribution of RMSE values calculated when we randomly permuted participants’ guesses within participant-issue-side, using 5,000 permutations. (Although the RMSE is not easily directly interpretable, for context, the average effect of the messages was approximately 3.6 percentage points.)

Fig. 2.

Adjustment RMSE under guessing null for practitioners (panel A) and the mass public (panel B).

Mirroring the “wisdom of crowd” results, we find that both practitioners and the mass public do predict better than guessing, but barely so. The -value for both comparisons is less than 0.01, indicating we have clear evidence that their predictions are better than random guessing. There is also again some evidence that practitioners may outperform the mass public on this metric. But, in terms of substantive magnitude, the estimated RMSE of both groups’ individual guesses is barely better than chance (Consistent with this conclusion that forecasters were statistically better than chance but not meaningfully so, we found that practitioners were 8.6 percentage points more likely to give their top forecast to messages with the highest estimated treatment effect within each issue-side (). Likewise, we found that practitioners performed slightly better than laypeople, who were 3.9 percentage points more likely to give their top forecast to messages with the highest estimated treatment effects (). Similar to the RMSE statistics, then, we find that both groups do better than chance but not meaningfully so, and that practitioners may perform slightly better than laypeople).

Robustness Across Subgroups.

Even though we found that practitioners perform barely better than chance at predicting persuasiveness overall, it is possible that certain subgroups of practitioners perform better, such as those with more experience or expertise. On the other hand, a variety of popular accounts could lead one to expect that some practitioners perform worse than chance at predicting what persuades the mass public (such as practitioners with highly unrepresentative social networks), which could lead practitioners as a whole to appear worse.

To investigate these possibilities, we preregistered that we would examine whether practitioners in a large number of subgroups would predict messages more accurately. We organize these subgroups into four categories:

Demographics (e.g., party, age, education, location, etc.)

Experience (amount of time working in politics, experience conducting various functions, kinds of organizations worked for, etc.)

Expertise (e.g., whether the participant reports being an expert on that particular issue, engages in persuasive work (91% of participants fall in this category), is confident in their predictions, etc.)

Information Environment (e.g., whether the practitioner’s social network works in politics, if they frequently speak with voters directly, what kinds of evidence they consume and prefer to consume, if they read Twitter frequently, etc.)

To examine these subgroups, we compute the adjusted RMSE separately among those in each subgroup and not (e.g., for those who live in Washington, DC, and for those who do not), and compute a SE for this RMSE using the bootstrap. We then estimate the difference in these RMSEs, along with a SE.

Due to the large number of hypotheses we tested, we highlight a representative set of results in Fig. 3, and show the results for the full set of preregistered subgroups in SI Appendix, Figs. S4–S7.

Fig. 3.

Differences in RMSEs. Each coefficient shows the difference in estimated RMSE between the first and second groups shown in the labels at Left. Negative coefficients (to the Left) therefore mean that the first group shown on the label is more accurate (has lower RMSE). Adjusted predictions (Left column) are first rescaled to match the mean and SD of the treatment effects. Unadjusted predictions (Right column) use raw numeric predictions. Red points (“individuals”) show the difference in the average RMSE for individuals in the two groups. Blue points (“Wisdom of Crowds”) show the difference in RMSE for the average of the groups’ predictions at the message level. Point estimates (points) are surrounded by SEs (thick lines) and 95% CIs (thin lines). See all results for all preregistered subgroups in SI Appendix, Figs. S4–S7.

The results in Fig. 3 are organized by the four groups of hypotheses we tested. Each coefficient shows the difference in estimated RMSE between the first and second groups shown in the labels at Left. For example, the first row compares the RMSE for those who said on the survey that they engage in persuasive work and that they do not. Negative coefficients (to the Left of the black line at 0) therefore mean that the first group shown on the label is more accurate (has lower RMSE). Adjusted predictions (Left column) are first rescaled to match the mean and SD of the treatment effects. Unadjusted predictions (Right column) use raw numeric predictions. Red points (“individuals”) show the difference in the average RMSE for individuals in the two groups. Blue points (“Wisdom of Crowds”) show the difference in RMSE for the average of the groups’ predictions at the message level. However, note that differences in the “wisdom of crowd” results at the group level are confounded by differences in the number of forecasters in each group so should be interpreted with caution (the individual-level differences do not have this issue).

Fig. 3 displays several noteworthy findings. First, there is not a single subgroup which is meaningfully more accurate than others. Nor is there a single subgroup that we find consistent evidence is more accurate than others across specifications. In other words, the overall pattern is a lack of any consistent evidence that certain subgroups more successfully predict the effects of the messages. The few statistically significant findings are low in substantive magnitude relative to the average RMSE for practitioners of approximately 0.038. Furthermore, even these statistically significant findings (e.g., the RMSE of individual Republicans’ adjusted predictions is approximately 10% lower (more accurate) than individual Democrats’ adjusted predictions) are not consistent across specifications (e.g., Republicans’ unadjusted predictions are less accurate than Democrats’).

Several of these null findings are particularly surprising.

First, we find no evidence that expertise meaningfully predicts accuracy. Individuals who said they engage in persuasive work have no more accurate adjusted predictions, and if anything their unadjusted predictions are less accurate at the individual level. In addition, practitioners who said they were very or somewhat confident in their predictions (i.e., self-assessed experts) were no more accurate—and if anything, their unadjusted predictions were less accurate (This was assessed with the survey question “How confident are you in your estimates of the effects of the messages you just saw?”). Furthermore, individuals who told us that they are experts on a particular issue are no more accurate at predicting the effects of messages intended to persuade on that issue than individuals who did not tell us they were experts on that issue (This comparison between experts and nonexperts is first conducted within issues. We then we compute a precision-weighted average across issues. This is to account for any potential correlation between how difficult it is to forecast the effects of the message by issue and how many observations we have per issue. Because experts are always asked about their issue, the number of practitioner forecasts per message differs by issue). People with expertise about a particular issue are no more accurate than other practitioners at identifying which of the messages most persuade on that issue (This was assessed with the survey question “Have you worked for, consulted on, or advised in a professional capacity on any of the following issues in the last 10 y?”).

Our patterns with respect to demographics are also consistently null. For instance, individuals who live in New York City or Washington, DC, in rural areas, or who are in the baby boomer generation rather than millennials are no more accurate.

Experience working in politics overall or in various political roles also appears not to correlate with predictive accuracy. For example, those who design persuasive mail, digital, or TV ads, those with managerial experience in a presidential campaign, and those who have been working in politics for over 10 y are also no more accurate.

Finally, measures of practitioners’ information environments are also not meaningfully related to their accuracy. For example, practitioners who have politically diverse networks (as measured by having at least four people of both parties among their close friends or family), talk to voters regularly, or regularly read survey experiments are not consistently or substantively more accurate.

We also examined the general possibility that some practitioners were consistently more accurate than others, consistent with the existence of so-called “superforecasters” (14) and the possibility that there may be variables that predict practitioners’ accuracy we neglected to measure. To examine this, we exploited the fact that the practitioners predicted the effects of messages on two sides of two issues. In particular, we tested whether those who forecasted more accurately on one side of one issue also did so on the other side or on the other issue, consistent with some practitioners being consistently more accurate across forecasting tasks. We did not find any evidence for this (We tested this in two ways. First, we ran regressions at the practitioner level predicting their performance on each issue-side with their performance on the other issue-sides and found statistically insignificant relationships. We also estimated a regression at the practitioner-issue-side level with practitioner fixed effects. The -statistic on this regression was insignificant and the adjusted statistic was negative, suggesting that who is forecasting the messages is not a meaningful predictor of how accurately their effects are forecast).

These null findings are inconsistent with critiques of practitioners as ineffective persuaders because they are unrepresentative of voters. Practitioners’ experience, expertise, information environment, and demographics do not meaningfully explain variation in their accuracy. Rather, these findings are more consistent with the fundamental difficulty of predicting the effects of persuasive messages (11, 25), and perhaps indeed with prediction in general (14).

We also tested whether practitioners’ errors were due to systematic biases such as a preference for messages that are more difficult to read or mention certain groups. SI Appendix, Fig. S8 shows that a number of message features do not predict whether practitioners on average over- vs. underestimate the effects of the messages, with one possible exception being that practitioners may overestimate the effects of messages that use conservative moral language (26). It is possible there may be other features of messages which would better predict practitioners’ errors, and this would be a valuable topic for future research.

Considering Alternative Explanations.

We next consider several potential alternative explanations for our findings.

One class of potential alternative explanations posits that the survey experimental estimates against which we judged practitioners’ forecasts might themselves be inaccurate. For example, it could be the case that the effects we measured in a survey environment would be different in a field context. Or, the presence of opposition messages in real-world campaigns (e.g., ref. 7) could change which messages are most effective.

A bounding exercise is able to address this variety of alternative explanation. In particular, to undermine our conclusions, practitioners would need to be good at predicting true real-world treatment effects, which this class of alternative explanations posits are not well-correlated with the treatment effects we measured in our experiments. However, in order to change our conclusions, the practitioners must to at least some extent agree with each other about which alternative set of messages they think are most effective. Otherwise, for example, if practitioner A thinks message A is better, practitioner B thinks message B is better, and practitioner C thinks message C is better, practitioners as a whole cannot possibly be highly accurate, regardless of which message is truly best. Examining the data from the practitioner forecasting survey, we find that there is in fact fairly minimal agreement among practitioners about which messages are most effective. For instance, within message, the SD of practitioner rankings is 1.06, close to what it would be under random guessing (1.31) and far from what it would be if elites agreed with each other (0). Likewise, only about 16% of the within-issue variation in individual practitioners’ rescaled forecasts of the message effects can be explained by the mean forecasts among all practitioners (We computed this statistic by running two linear regressions with individual practitioners’ predictions as the outcome, a first regression with issue fixed effects and a second regression that added message fixed effects, which capture practitioners’ average forecasts for each message. (Messages are nested within issues.) The on this regression increases from 0.836 to 0.862 by adding the message fixed effects, indicating that only of the within-issue variation in practitioners’ predictions can be explained by their average predictions. (Note that the in the baseline regression is high by construction because the rescaled predictions within each issue-practitioner are constructed so as to have the same mean across all practitioners within issue, matching the issue-specific treatment effect mean from the survey experiment. The equivalent regressions for the raw nonrescaled estimates therefore have much lower values of 0.035 and 0.047, respectively).) This 16% estimate represents a “worst case” upper bound on how much variation in individual practitioners’ rescaled forecasts an unobserved true set of average treatment effects could explain (Furthermore, although our study is similar to the vast majority of studies in political science and psychology in using survey-based experiments to measure the effects of messages, there are reasons to be optimistic that our survey experimental estimates would be well-correlated with real-world effects: Previous research, albeit about different research questions, generally finds relatively robust correspondence between the effects of treatments in field and other settings (27). Experimenter effects or demand contaminating the effects of the messages are also unlikely to change our conclusions: Because we examine variation between messages arguing the same thing, if all of these estimates are similarly inflated by demand, it would not affect our findings. With that said, while our research does not offer any new evidence on the reliability of in-survey message testing and we encourage future research into this topic, the bounding exercise we conducted above indicates that our overall findings do not depend on the accuracy of these estimates).

A final possibility is that political elites are balancing a trade-off between messages that mobilize supporters and persuade opponents, or thinking about specific subgroups when answering our questions. Although our instructions (SI Appendix, Fig. S9) asked elites to focus only on what would persuade and specified that the messages were tested in a general population sample, it is possible they also thought about what messages would most mobilize supporters or persuade particular subgroups when answering. However, consistent with (28), the effects of the messages are fairly homogeneous across voters’ parties and demographics, suggesting it is not the case that different messages are more persuasive to one’s own side relative to the other side or to various subgroups.

Limitations.

Our research reflects several important limitations.

First, an important limitation concerns our samples: a convenience sample for the mass public and a 7.1% response rate in our survey of political practitioners. Our convenience sample was fairly representative on observable demographics to begin with (SI Appendix, Table S2), and we use survey weights to improve this representativeness. Nevertheless, future work should consider whether our results are robust when a more representative sample or a different set of political practitioners is used instead.

Next, there are multiple approaches for measuring perceived message effectiveness (PME) (29). We validated that our approach of asking respondents to estimate treatment effects was highly related to other measures of PME (see Footnote‡‡ for details), but future research should consider if other measures of PME replicate our findings. It is also possible that previously participating in the experiments to measure the effects of the messages may have influenced how lay participants forecasted the effects of messages, although we note that participants forecasted the effects of messages on different topics, and so never forecasted the effects of messages to which they had been exposed as part of the experiments.

We also note that it is possible we may have found different results with the use of video-based messages than text-based messages. This is another important topic for future research to consider. With that said, Wittenberg et al. (18) find that text-based political messages have fairly similar persuasive effects to video-based political messages. It is also possible that the effects of the messages might have been different with repeated exposure instead of a single exposure, or in a richer political context with source cues or competing messages.

In addition, our research did not consider the role of message targeting; it is possible that participants could have predicted the effects of the messages more accurately if we had asked them to forecast effects among particular audiences (e.g., ref. 30).

Finally, as only 11% of our sample identified as Republicans, future research should seek to recruit a larger sample from this group.

Implications

Scholarship’s robust finding that political elites can have tremendous potential to persuade the public sits at odds with findings that their real-world persuasion efforts also often have limited effects (e.g., refs. 4–6). There are a variety of explanations for this disjuncture, such as the role of competing communication (7).

In this paper, we surface another, complementary possibility: that the political practitioners who are responsible for determining how the public is persuaded have poor baseline intuitions about which messages to use to persuade the public.

A standard assumption in political science is that professional political practitioners act optimally. Under this assumption, political practitioners would be expected to use the most persuasive messages. However, evidence from a variety of other studies suggests humans are generally poor at the kind of complex prediction task that predicting the persuasive effects of various messages represents. Evidence from psychology indicates that laypeople are bad at predicting what messages are persuasive in a variety of substantive domains (11). This difficulty mirrors evidence from other domains, where experts in a variety of fields tend to have difficulty predicting the effects of various interventions (e.g., refs. 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, and 15) and the probability of various world events (14). Indeed, Tetlock (14) finds some evidence for a curse of expertise: that experts overestimate the value of their expertise and therefore make overconfident predictions. Our survey found some evidence for this: While only 15% said it was “typically obvious” to them which messages were most persuasive, 66% said that simply reflecting on their past experience was a common tool they used to determine which messages were persuasive. Likewise, 39% said they were somewhat or very confident in their predictions (even though, as we showed above, this group’s predictions were no more accurate).

Forecasting the persuasive effects of political messages is unlike forecasting the effects of future world events (14), though, because there are methods other than intuition to assess them, especially experiments of various forms. On a practical level, then, our findings resonate with findings from recent research on the value of experimentation (17): Some messages are meaningfully more persuasive than others, but if practitioners cannot predict which are more persuasive, it is in their interest to gather data (e.g., from experiments) that can identify them. This suggests that gathering experimental data to learn what works, rather than relying on political practitioners’ limited ability to forecast what is persuasive, may be most useful for political practitioners.

Many practitioners have received this message, and data-driven campaigning is on the rise—presumably because many practitioners realize that their intuitions are often unreliable (31). However, this view is far from universal: Among our survey respondents who work on developing persuasive messaging, only about half (53%) said they often used survey or field experiments to determine which messages are most effective, with less rigorous forms of research (e.g., meeting with other interest groups, focus groups) and intuition being common. With that said, an important area for future research is to better understand how practitioners integrate increasingly available data into their decision-making, an inquiry that could be well-suited for qualitative research. Rather than taking for granted that political practitioners are optimally persuasive or that they make the best use of this data when composing messages, our research suggests that more research is needed into understanding how practitioners decide what to say to the public. To reach a full understanding of how elites affect public opinion, we cannot only study how voters react to elites—we must also investigate how elites see the public.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank P. Aronow, Edward Chang, Kevin Collins, Alex Coppock, Jamie Druckman, Angela Duckworth, Luke Hewitt, Katherine Milkman, Daniel O’Keefe, Ethan Porter, and Adam Shinegate for helpful feedback and Brynn Baker, Laila Davson, Riley Elliott, Xavier Guaracha, Josie Helm, Jack Maedgen, Maia Roothaan, Christian Thomas, and Kalvin Verner for their work as research assistants.

Author contributions

D.E.B. and J.L.K. designed research; D.E.B., J.L.K., C.C., and M.E. performed research; D.E.B. and J.L.K. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; D.E.B., J.L.K., C.C., and M.E. analyzed data; and D.E.B. and J.L.K. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission J.N.C. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

*A related literature has found that laypeople self-generate messages that are most persuasive to people like themselves rather than people who do not agree with them (e.g., ref. 16).

†SI Appendix, Table SI contains the full list of issues. They covered a broad range of social (e.g., abortion and LGBTQ+ rights) and economic (e.g., Medicare and student debt relief) topics.

‡Furthermore, practitioners routinely use short paragraphs to test the effects of messages; see https://campaigner.substack.com/p/inside-progressives-message-testing for an example discussion.

§These edits included replacing pronouns with nouns for clarity (e.g., “they” to “assault weapons”) or removing partisan cues (e.g., changing “The GOP” to “some politicians”), and cutting off paragraphs once they exceeded approximately 70 words. All formatting was removed.

¶This procedure was preregistered at https://osf.io/rbepw?view_only=3d87a71d7a384755a79ef8b288fec4bc.

#We weighted on partisanship, race, education, and gender. Our preanalysis plan did not mention using survey weights.

‖These emails came from the membership directories of American Association for Public Opinion Research (the political practitioner members specifically) and American Association of Political Consultants, the consultant directory from Campaigns & Elections magazine, the judges of the American Association of Political Consultants’ Pollie Awards, the websites of major interest groups and state affiliates identified by Vote Smart, attendees of practitioner webinars where the authors previously presented their research, and emails purchased from the RocketReach and BookYourData databases.

**As shown in SI Appendix, the full question wording was, “Currently or within the last 10 years, have you played a role in developing, advising on, informing, helping to select, polling, or testing which messages are used as part of political persuasion, issue advocacy, or public education campaigns?” In a separate survey question, we asked “Political professionals use a variety of techniques to understand what messages will most effectively persuade voters as part of public education, issue advocacy, or candidate campaigns. When trying to determine which messages are most effective, which of the following approaches do you often use? Please include any tactics that firms you hire for this work often use in work for you. Select all that apply.” Only 5% selected “I don’t engage in work to persuade or educate the public,” implying 95% “engage in work to persuade or educate the public.”

††If the broad issue domain contained multiple subissues (e.g., immigration contained three subissues: border security funding, number of legal immigrants, DREAM Act), then we randomly selected which subissue was shown.

‡‡This procedure was based on that used by Milkman et al. (8) to assess scientists’ and lay survey respondents’ predictions of the impact of different messages on flu vaccination rates. We further validated this procedure in a presurvey of 768 subjects in which we first asked them both their numeric predictions of three statements and how convincing they thought each statement was using a four-point Likert scale. Suggesting that subjects understood our survey question, we found that their numeric predictions of treatment effects were statistically significantly related to their answers to a separate survey question asking them how convincing each message was. In particular, when regressing individuals’ treatment effect estimates on how convincing they rated a message on a 1 to 4 Likert scale, the coefficient was 4.48, indicating that when individuals rated a message as 1 Likert scale point more convincing, they on average expected the treatment effect of that message to be 4.48 percentage points more persuasive (, ). We also compared this to other potential question formats, which we rejected because they were less strongly correlated with perceptions of convincingness.

§§We preregistered our analysis at https://osf.io/su6x7?view_only=e84c4adc1f054856824fe65a7ecf715e. There are two notable deviations from our preanalysis plan. First, as we discuss below, we calculate an Adjusted RMSE to adjust for the sampling error associated with our estimates of the treatment effects. This adjustment was not mentioned in the preanalysis plan. Second, we use a different rescaling procedure from that originally preregistered.

¶¶Due to the shared control group within issue-sides in the message experiments and the issue-side fixed effects in the meta-regression, this meta-regression uses the SEs associated with the estimates of mean support levels within each treatment arm.

##Later in the paper, we consider how the possibility that the survey experimental estimates are themselves biased (e.g., not externally valid) would affect our conclusions, and discuss why this would not change our conclusions meaningfully.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

Anonymized survey data and code data have been deposited in Open Science Foundation (https://osf.io/zfh3y/) (32).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Chong D., Druckman J. N., Framing public opinion in competitive democracies. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 101, 637–655 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falk E., Grizard E., McDonald G., Legislative issue advertising in the 108th congress pluralism or peril? Harv. Int. J. Press. 11, 148–164 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheingate A. D., Building a Business of Politics: The Rise of Political Consulting and the Transformation of American Democracy (Oxford University Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalla J. L., Broockman D. E., The minimal persuasive effects of campaign contact in general elections: Evidence from 49 field experiments. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 112, 148–166 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalla J. L., Broockman D. E., ‘outside lobbying’ over the airwaves: A randomized field experiment on televised issue ads. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 116, 1126–1132 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wlezien C., Soroka S., Media reflect! policy, the public, and the news Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 118, 1–7 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Druckman J. N., Lupia A., Preference change in competitive political environments. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 19, 13–31 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milkman K. L., et al. , A 680,000-person megastudy of nudges to encourage vaccination in pharmacies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 119, e2115126119 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DellaVigna S., Linos E., RCTs to scale: Comprehensive evidence from two nudge units. Econometrica 90, 81–116 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartnett N., et al. , Marketers’ intuitions about the sales effectiveness of advertisements. J. Mark. Behav. 2, 177–194 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Keefe D. J., Message pretesting using assessments of expected or perceived persuasiveness: Evidence about diagnosticity of relative actual persuasiveness. J. Commun. 68, 120–142 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Keefe D. J., Message pretesting using perceived persuasiveness measures: reconsidering the correlational evidence. Commun. Methods Meas. 14, 25–37 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milkman K., et al. , Megastudies improve the impact of applied behavioural science. Nature 600, 478–483 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tetlock P. E., Expert Political Judgment (Princeton University Press, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahrenshop M., Golden M., Gulzar S., Sonnet L., Inaccurate forecasting of a randomized controlled trial. J. Exp. Polit. Sci. 1–17 (2023).

- 16.Feinberg M., Willer R., From gulf to bridge: When do moral arguments facilitate political influence? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 41, 1665–1681 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hewitt L., et al. , How experiments help campaigns persuade voters: Evidence from a large archive of campaigns’ own experiments. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 1–19 (2024).

- 18.Wittenberg C., Tappin B. M., Berinsky A. J., Rand D. G., The (minimal) persuasive advantage of political video over text. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2114388118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bloniarz A., Liu H., Zhang C. H., Sekhon J. S., Yu B., Lasso adjustments of treatment effect estimates in randomized experiments. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 7383–7390 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.B. Schaffner, S. Ansolabehere, M. Shih, Data from “Cooperative Election Study Common Content, 2022.” Harvard Dataverse, V4. 10.7910/DVN/PR4L8P. Accessed 28 December 2023. [DOI]

- 21.Hainmueller J., Entropy balancing for causal effects: A multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Polit. Anal. 20, 25–46 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hertel-Fernandez A., Mildenberger M., Stokes L. C., Legislative staff and representation in congress. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 113, 1–18 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broockman D. E., Carnes N., Crowder-Meyer M., Skovron C., Why local party leaders don’t support nominating centrists. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 51, 724–749 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 24.R. P. Larrick, A. E. Mannes, J. B. Soll, “The social psychology of the wisdom of crowds” in Social Judgment and Decision Making, M. J. I. Krueger, Ed. (Psychology Press, 2012), pp. 227–242.

- 25.D. J. O’Keefe, “Trends and prospects in persuasion theory and research” in Perspectives on Persuasion, Social Influence, and Compliance Gaining, J. S. Seiter, R. H. Gas, Eds. (Pearson/Allyn and Bacon, 2004), pp. 31–43.

- 26.Haidt J., The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion (Pantheon, New York, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coppock A., Green D. P., Assessing the correspondence between experimental results obtained in the lab and field: A review of recent social science research. Polit. Sci. Res. Methods 3, 113–131 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coppock A., Persuasion in Parallel: How Information Changes Minds About Politics (University of Chicago Press, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noar S. M., Barker J., Yzer M., Measurement and design heterogeneity in perceived message effectiveness studies: A call for research. J. Commun. 68, 990–993 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bennett W. L., Manheim J. B., The one-step flow of communication. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 608, 213–232 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Issenberg S., The Victory Lab: The Secret Science of Winning Campaigns (Crown, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 32.D. E. Broockman, J. L. Kalla, C. Caballero, M. Easton, Replication data for “Political practitioners poorly predict which messages persuade the public.” Open Science Framework. https://osf.io/zfh3y/. Deposited 16 October 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized survey data and code data have been deposited in Open Science Foundation (https://osf.io/zfh3y/) (32).