Significance

Genetic mutations of the transfer RNA (tRNA) modification enzymes including the tRNA N7-methylguanosine (m7G) methyltransferase complex component WDR4 are frequently found in patients with neural disorders, while the pathogenic mechanism and therapeutic intervention strategies remain to be explored. In this study, we uncovered the molecular mechanisms underlying WDR4 mutation in the pathogenesis of neural diseases using mouse models and human iPSCs-derived neuron stem cells harboring patient-derived WDR4 mutation. We further developed two therapeutic strategies for the intervention of WDR4 mutated neural diseases. Our study provides the molecular basis for development of clinical treatment strategies for WDR4 mutated patients.

Keywords: N7-methylguanosine (m7G), tRNA modification, WDR4, gene therapy, neural diseases

Abstract

Mutations modification enzymes including the tRNA N7-methylguanosine (m7G) methyltransferase complex component WDR4 were frequently found in patients with neural disorders, while the pathogenic mechanism and therapeutic intervention strategies are poorly explored. In this study, we revealed that patient-derived WDR4 mutation leads to temporal and cell-type-specific neural degeneration, and directly causes neural developmental disorders in mice. Mechanistically, WDR4 point mutation disrupts the interaction between WDR4 and METTL1 and accelerates METTL1 protein degradation. We further uncovered that impaired tRNA m7G modification caused by Wdr4 mutation decreases the mRNA translation of genes involved in mTOR pathway, leading to elevated endoplasmic reticulum stress markers, and increases neural cell apoptosis. Importantly, treatment with stress-attenuating drug Tauroursodeoxycholate (TUDCA) significantly decreases neural cell death and improves neural functions of the Wdr4 mutated mice. Moreover, adeno-associated virus mediated transduction of wild-type WDR4 restores METTL1 protein level and tRNA m7G modification in the mouse brain, and achieves long-lasting therapeutic effect in Wdr4 mutated mice. Most importantly, we further demonstrated that both TUDCA treatment and WDR4 restoration significantly improve the survival and functions of human iPSCs-derived neuron stem cells that harbor the patient’s WDR4 mutation. Overall, our study uncovers molecular insights underlying WDR4 mutation in the pathogenesis of neural diseases and develops two promising therapeutic strategies for treatment of neural diseases caused by impaired tRNA modifications.

Mis-regulations of RNA modifications are emerging as critical pathogenic factors for various diseases including developmental disorders and cancers (1). Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are heavily modified, which facilitate tRNA folding and stability, and thus play essential functions in mRNA translation and various biological processes (2, 3). Emerging evidence reveals that hyperactivations of tRNA modifications enhance oncogenic mRNA translation and promote cancer progression (4–6). On the other hand, genetic mutations of tRNA modification enzymes are frequently found in patients with neurodevelopmental defects (7–9). However, the molecular mechanisms underlying the neural-specific disease progression in patients with impaired tRNA modifications are still poorly understood.

N7-methylguanosine (m7G) tRNA modification is a highly conserved modification that occurs at position 46 within the variable loop of tRNAs (10). It’s catalyzed by methyltransferase (MTase) Trm8 and its cofactor Trm82 in yeast, the orthologs of which in humans are METTL1 and WDR4, respectively (11, 12). The m7G46 modification on tRNA can form a tertiary base pair with C13–G22 and thus plays an important function in maintaining tRNA stability (10). Interestingly, tRNA m7G modification is nonessential in yeast since loss of functional Trm8 or Trm82 has no obvious defect in the growth of yeast under normal culture condition (11). While the tRNA m7G modification deficient cannot survive under heat stress, suggesting the important functions of tRNA m7G modification in stress responses in yeast (11, 13). Different from yeast, mis-regulated tRNA m7G modification is closely linked to human diseases (9, 14–16). Mutations of the WDR4 gene are identified in a variety of patients with microcephalic primordial dwarfism and other neurodevelopmental defects (9, 14–16), suggesting the more essential functions of tRNA m7G modification in mammals.

WDR4 is a constituent component of the MTase protein complex that is essential for the MTase activity by supporting SAM and tRNA substrate binding (17–19). WDR4-R170L mutation (NM_033661.4:c.509G > T; p.Arg 170Leu) is the most common variant found in the patients with WDR4 mutation. The molecular effect of the WDR4-R170L has been studied extensively under different context. In yeast, the corresponding residue K223 (R170) of Trm82 (homolog of WDR4) is speculated to form a salt bridge with residue E204 (E183) of Trm8 (homolog of METTL1) to maintain Trm8 in an active conformation (9). Recent crystal structure of the human METTL130–265–WDR41–367 complex also revealed that R170 of human WDR4 interacts extensively with multiple residues (including E183 of METTL1) within the METTL1–WDR4 complex (19). On the other hand, Li et al. reported that the R170 of human WDR4 likely does not interact with METTL1 but rather mediates intramolecular WDR4 interactions for WDR4 stabilization in the METTL1–WDR4 complex (18). Ruiz-Arroyo et al. also reported that R170 of WDR4 interacts with nearby backbone carbonyls within WDR4 to facilitate hydrophobic intermolecular interactions between truncated crystal constructs of METTL120–265–WDR41–389 (17). Despite the controversy on whether WDR4-R170 directly interacts with METTL1, all the above studies demonstrate that R170 of WDR4 is essential for the MTase activity of METTL1–WDR4 complex, suggesting the important pathogenic role of WDR4-R170L mutation mediated impaired tRNA m7G modification in neural diseases.

The WDR4 mutated patients showed severe growth and development disorders as well as movement and mental disabilities (9, 14–16). A recent study using neural-specific Wdr4 knockout mouse model uncovered that WDR4 plays important functions in promoting cerebellar development and locomotion through Arhgap17-mediated Rac1 activation (20). In addition, our previous study using Wdr4 knockout mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) also revealed that loss of tRNA m7G modification disrupts mESC neural lineage differentiation, indicating the important role of tRNA m7G modification in neural development (21). Though mouse genetic knockout studies demonstrated the essential function of WDR4 in neural development (20, 21), little is known about the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms of WDR4 mutations in patients, and currently there is no effective therapeutic intervention strategy for treatment of neural diseases associated with impaired tRNA modifications.

In this study, we generated a Wdr4 point mutation (Wdr4R215L/R215L) mouse model that mimics the WDR4-R170L mutation in human patients. Our data revealed that patient-derived WDR4 point mutation directly causes neural developmental disorders and intellectual disability in mice. Mechanistically, mutation of WDR4 results in the degradation of METTL1 protein, altered m7G tRNA modification, and decreased translation of genes involved in mTOR pathway, leading to elevated expression of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress response genes and increased apoptosis in the cerebellum. Attenuating ER stress with TUDCA or restoring wild-type WDR4 notably improves the neural functions of the Wdr4 mutated mice. We further revealed that TUDCA treatment and WDR4 restoration can recover the survival and function of human iPSCs-derived neuron stem cells (NSCs) harboring WDR4-R170L mutation. Our data uncover the pathogenetic mechanisms of WDR4 mutation and provide the molecular basis for the therapy of tRNA-related neural diseases.

Results

WDR4 Mutation Leads to Development, Movement, and Intellectual Disabilities.

To study the molecular mechanisms underlying the patient-derived WDR4 mutations in pathogenesis of neural disorders, we generated a Wdr4 point mutation mouse model (NM_021322.2:p.644G > T; p.Arg 215Leu) that mimics the commonly found WDR4 mutation in patients (NM_033661.4:c.509G>T; p.Arg 170Leu) (Fig. 1 A–C). Our data reveal that Wdr4 homozygous mutated (Wdr4R215L/R215L) mice show serious growth and development retardation, as reflected by the significantly lower body weight and smaller body size compared to the wild-type (Wdr4+/+) mice (Fig. 1 D–F and SI Appendix, Fig. S1 A and B). In addition, the overall survival time of Wdr4R215L/R215L mice is significantly shorter than that of the Wdr4+/+ mice (Fig. 1G). There is no obvious difference in the morphology, body weight, survival time, and brain size between Wdr4+/R215L and Wdr4+/+ mice, indicating that heterozygous mutation of Wdr4 is sufficient to produce enough WDR4 protein for the normal development of mice (Fig. 1 D–G and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Overall, these data demonstrate that the point mutation of Wdr4 in mice leads to similar disease phenotypes as those in human patients, supporting that WDR4 point mutation directly causes developmental retardation in patients.

Fig. 1.

Wdr4 mutation leads to development, movement, and intellectual disabilities. (A) The homologous amino acid sequence between the human and mouse at the WDR4 mutation site found in patients. (B) Schematic representation for the generation of Wdr4 mutated knock-in mice. (C) Sanger sequencing showed the wild-type and mutated sequence of the Wdr4 gene in mice. (D) Representative images of littermates with different genotypes on postnatal week 8. (E and F) Growth curve of female (E) and male (F) mice with different genotypes (n = 8). (G) Survival curve of mice with different genotypes (n = 18). The survival of the Wdr4+/R215L is the same as Wdr4+/+. Therefore, their survival curves overlap with each other. (H) Number of step errors that the mice slipped to the side of beam in the beam balance test (n = 5). (I) Traversal time of mice in the beam balance test (n = 5). (J and K) Latency time before the mice fell in the rotarod test (J) and traction test (K) (n = 5). (L and M) Total errors (L) and total time (M) that the 2-mo-old mice took to reach and enter the target hole (n = 6, three per sex). (N and O) Primary errors (N) and primary time (O) that the 2-mo-old mice took to first reach and poke into the target hole (n = 6, three per sex). (P) Number of visit pokes to each hole during the probe trial on day 5 in the Barnes maze test (n = 6, three per sex). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using RM two-way ANOVA (L–O) or two-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s (E and F) or Sidak’s (H–K) multiple comparisons test. n.s. P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Given that the WDR4 mutated patients show symptoms of motor development and mental disabilities, we then performed behavior and cognitive ability assays to evaluate whether patient-derived WDR4 point mutation leads to movement and intellectual disabilities in mice. Our beam balance assay reveals that mice with Wdr4R215L/R215L show significantly longer traversal time and a higher number of step errors 8 wk after birth (Movie S1 and Fig. 1 H and I). In addition, swimming (Movie S2), rotarod (Fig. 1J), and traction (Fig. 1K) tests further demonstrate the movement disorders in the 8-wk-old Wdr4R215L/R215L mice. Interestingly, though the 8-wk-old Wdr4R215L/R215L mice show severe movement disorders, the 4-wk-old Wdr4R215L/R215L mice exhibit relatively normal movement capacities, indicating the gradual pathogenic process in the Wdr4R215L/R215L mice (Fig. 1 H–K). We next performed the Barnes maze test to evaluate the cognitive ability and revealed that 8-wk-old WDR4 mutated mice have worse performance in spatial learning (Fig. 1 L–O). Moreover, Wdr4R215L/R215L mice fail to locate the target hole in the Barnes maze test in the probe trail (Fig. 1P), indicating that Wdr4R215L/R215L mice have impaired spatial memory. It should be noted that the movement disability could affect the Wdr4R215L/R215L mice to explore and learn the maze at the acquisition phase. Thus, the change between two groups to find the target hole could be due to a combination effect of physical impairment, behavioral changes, and learning/memory defects. However, the Wdr4R215L/R215L mice show no preference for the target hole in the probe trail, which supports the impaired spatial memory in the Wdr4 mutated mice. Taken together, these results provide strong evidence supporting that Wdr4R215L/R215L directly causes obvious movement and intellectual disabilities in patients.

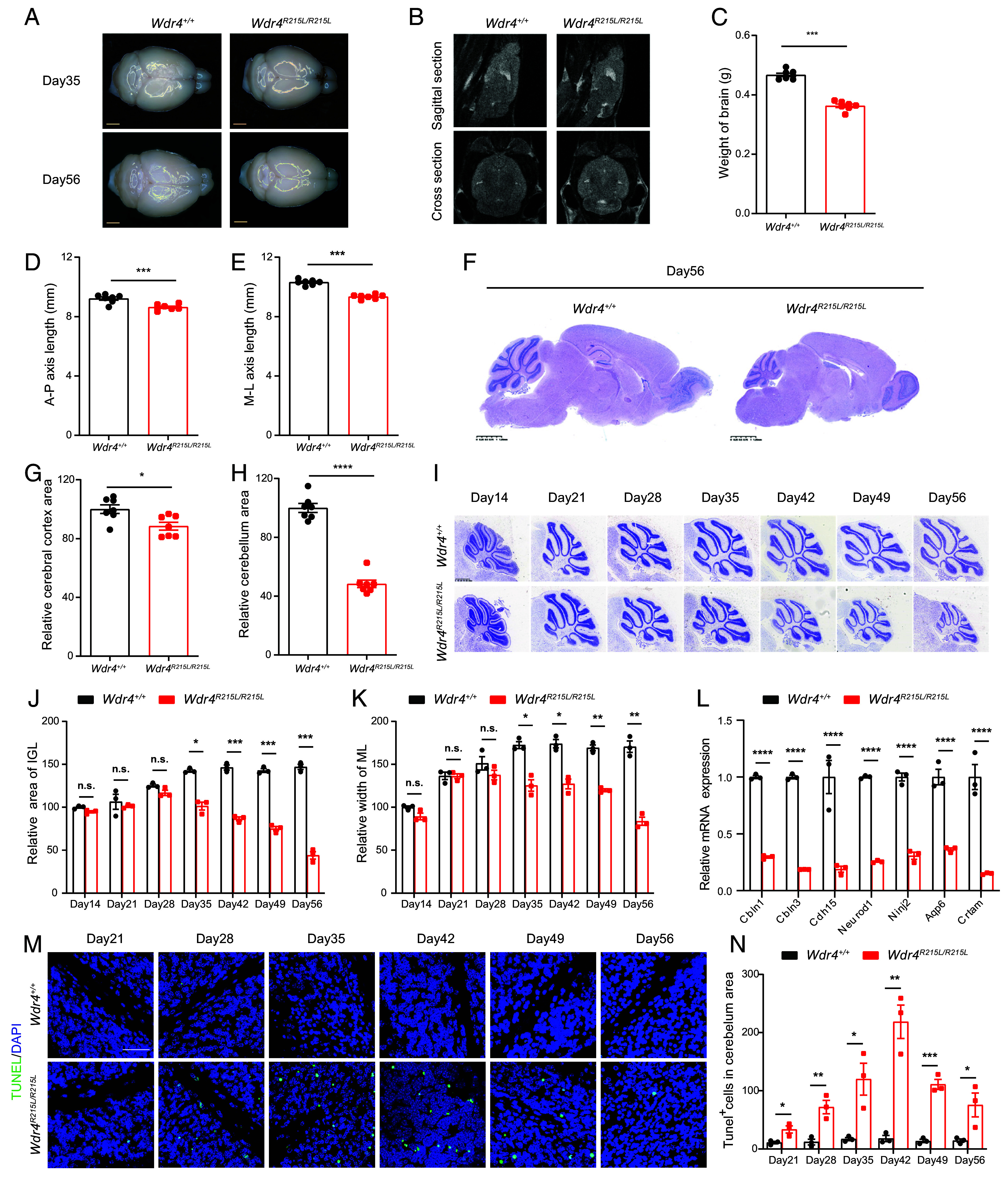

WDR4 Point Mutation Causes Neural Cell Death and Microcephaly.

Since WDR4 point mutation causes abnormal behavior and intellectual disabilities, we further evaluated the brain morphology of Wdr4 mutated mice. Similar to the microcephaly symptoms in patients with WDR4 mutations, the Wdr4 point mutation mice have smaller brain sizes and weights, and exhibit serious atrophy of the cerebellum 8 wk after birth (Fig. 2 A–E). Hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining revealed a modest decrease in the cerebral cortex and massive reduction of cerebellar areas in the brains of Wdr4 mutated mice (Fig. 2 F–H). Given that the Wdr4 point mutation mice show gradual pathogenetic process (Fig. 1 H–K), we further determined the disease progression at different time points and found that the cerebellums of Wdr4 mutated mice are relatively normal within 4 wk after birth, but develop cerebellar atrophy since postnatal day 35, as reflected by significantly decreased area of internal granule layer (IGL) and declined width of molecular layer (ML) in cerebellum area (Fig. 2 I–K). qPCR analysis revealed notable decrease in the expression levels of cerebellar genes (Fig. 2L), which is consistent with the cerebellar atrophy phenotypes found in Fig. 2I. We further detected cell death by TUNEL staining and found a drastic increase of TUNEL+ apoptotic cells in the cerebellum of Wdr4 mutated mice (Fig. 2 M and N). Taken together, these results suggest that WDR4 point mutation leads to cell death, cerebellar atrophy, and microcephaly.

Fig. 2.

WDR4 point mutation causes neural cell death and microcephaly. (A) Representative images of whole brains from Wdr4+/+ and Wdr4R215L/R215L littermates on postnatal day 35 and day 56 (Scale bar, 2,000 μm.) (B) MRI of mouse brains on postnatal day 56 at sagittal and cross sections. (C) Brain weights of mice at postnatal day 56 (n = 7). (D and E) Measurements of brain size from the anterior to posterior (A–P) axis and the medial to lateral (M–L) axis length of mouse forebrains at postnatal day 56 (n = 7). (F) Representative HE staining images of whole brains from Wdr4+/+ and Wdr4R215L/R215L littermates at postnatal day 56 at sagittal section. (Scale bar, 1.25 mm.) (G and H) Measurements of the cerebral cortex (G) and cerebellum area (H) at sagittal section at postnatal day 56 (n = 7). (I) Representative Nissl staining images of the cerebellum from mice at indicated postnatal days. (Scale bar, 625 μm.) (J and K) Area of IGL and width of ML in cerebellum area at sagittal section at indicated postnatal days (n = 3). (L) qPCR analysis of genes involved in cerebellar development and function. The genes were chosen by overlapping our RNA sequencing data with the Cerebellar Gene Database (https://cbgrits.org/Database/CerebellarGene). Total RNA from the whole brain of 2-mo-old mouse was used in this assay. (M) Representative TUNEL staining images of the cerebellum from mice at indicated postnatal days. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (N) Quantification of TUNEL+ cells in the cerebellum area. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using the unpaired t test (C–E, G, and H) or two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (J–L and N). n.s.P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

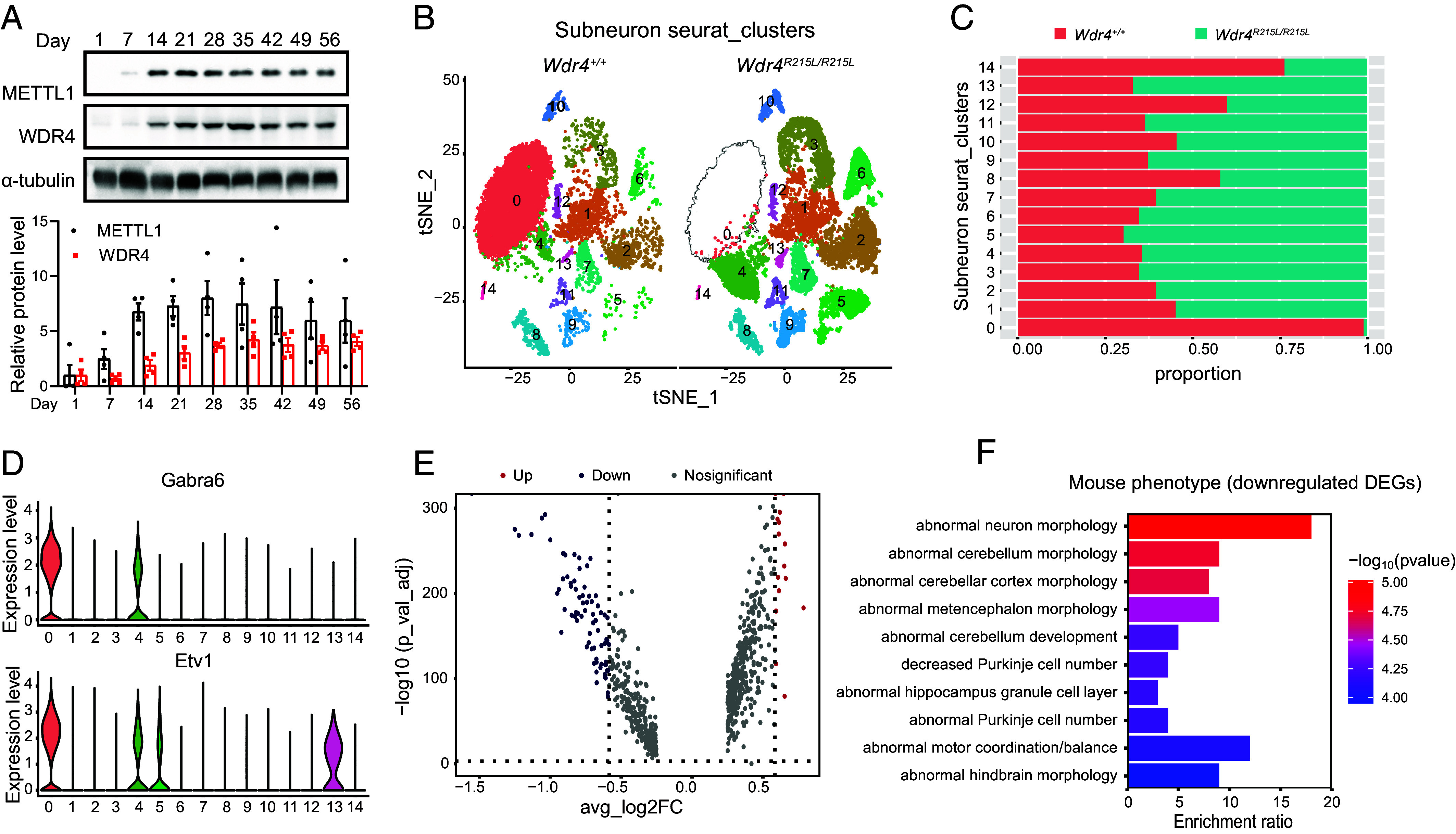

Temporal and Cell-Type-Specific Degeneration in the Brain of Wdr4 Mutated Mice.

The gradual pathogenic process of cerebellar atrophy indicates the spatial-temporal functions of METTL1/WDR4 mediated tRNA m7G modification in regulation of brain development and homeostasis. We first determined the expression of METTL1 and WDR4 at different timepoints and revealed that METTL1 and WDR4 expression gradually increase from postnatal day 1 and reach to the peak at about day 28, which could explain why the Wdr4 mutated mice start to exhibit obvious movement and intellectual disabilities after postnatal day 28 (Fig. 3A). We further performed single nucleus RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) to uncover the tissue composition and characteristics of Wdr4 mutated brain at single cell level. Totally 7 cell types are identified based on the expression of known cell-type specific markers (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and B), and neurons are the most abundant cells among all cell types (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C). We further reclustered the neurons and uncovered a drastic decrease of a neuron subcluster (cluster 0) in the Wdr4 mutated brains (Fig. 3 B and C). This neuron subcluster 0 expresses high levels of granule cell markers Gabra6 and Etv1 (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S2D), suggesting the cell-type-specific degeneration of granule cells in the cerebellum of the Wdr4 point mutation mouse. Gene ontology analysis revealed that the down-regulated differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in neuron subclusters between brains of Wdr4 mutated and control mice are associated with abnormal neuron and cerebellum morphology (Fig. 3 E and F, SI Appendix, Fig. S2E, and Dataset S1). Overall, our data demonstrate the temporal and cell-type-specific functions of WDR4 in regulation of brain postnatal development and homeostasis.

Fig. 3.

Temporal and cell-type-specific degeneration in the brain of the Wdr4 point mutation mouse. (A) Western blot analysis of METTL1 and WDR4 in the whole brain of the wild-type mouse at different postnatal days (n = 4). (B) t-SNE plot of reclustered neuron (from neuron cluster 0, 1, 2, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10 in SI Appendix, Fig. S2A) identified 14 neuron subclusters. (C) Bar graph showing the cell proportions of neuron subclusters. (D) Violin plots showing the expression of granule cell marker genes Gabra6 and Etv1 in neuron subclusters. (E) Volcano plots showing the significantly DEGs in neurons between Wdr4+/+ and Wdr4R215L/R215L brain samples. (F) Mouse phenotype analysis of down-regulated DEGs. Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

Wdr4 Point Mutation Blocks Its Interaction with METTL1 and Destabilizes METTL1.

To investigate the pathogenesis mechanism, we evaluated the effect of WDR4 point mutation on tRNA m7G modification. Our data revealed that Wdr4 point mutation leads to drastic decrease of tRNA m7G modification (Fig. 4A). Given that tRNA m7G modification is catalyzed by the METTL1/WDR4 methyltransferase complex, we further determined the expression of METTL1 and WDR4 in the Wdr4 mutated mouse brain. We found that Wdr4 point mutation results in decreased level of METTL1 protein but has little effect on the Mettl1 mRNA level (Fig. 4 B–D). Interestingly, our immunohistochemical (IHC) staining revealed that METTL1 is highly expressed in the cerebellum, and its expression in other regions of the brain is relatively lower, which is consistent with the cerebellum-specific degeneration phenotype in the WDR4 point mutation mice (Figs. 2I and 4C). Treatment with proteasome inhibitor MG132 increases the protein level of METTL1 in Wdr4 mutated primary neural stem cells (NSCs), indicating that Wdr4 point mutation leads to the degradation of METTL1 protein (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Wdr4 point mutation destabilizes METTL1 through protein degradation. (A) Northern-western analysis and quantification of tRNA m7G levels in mouse brains (n = 3). (B) Western blot analysis and quantification of the METTL1 and WDR4 protein levels in mouse brains (n = 3). (C) Representative IHC staining images of METTL1 in mouse brains at sagittal section on postnatal day 56. (D) Relative mRNA levels of Mettl1 and Wdr4 in mouse brains on postnatal day 56 (n = 3). (E) Western blot analysis of the METTL1 protein level in mouse embryonic NSCs with MG132 treatment. (F and G) Coimmunoprecipitation analyzed the protein interaction between WDR4 and METTL1. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using the unpaired t test (A) or two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (B and D). n.s.P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

To explore the molecular mechanism underlying WDR4 point mutation in regulation of METTL1, we performed three-dimensional structural modeling and showed that WDR4 point mutation (R170L) changes the electrostatic potential energy and disrupts the hydrogen bond formed between R170 in wild-type WDR4 and E183 in METTL1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Protein coimmunoprecipitation assay uncovered that point mutated WDR4 fails to interact with METTL1, suggesting that WDR4 protects METTL1 protein from protein degradation (Fig. 4 F and G). Taken together, these results demonstrate that WDR4 point mutation disrupts the interaction between WDR4 and METTL1 and destabilizes METTL1 through protein degradation.

Wdr4 Point Mutation Leads to Impaired m7G tRNA Modification, Decreased mRNA Translation, and Elevated ER Stress.

We further explored the mechanisms underlying Wdr4 point mutation in pathogenesis of neural degeneration. We performed tRNA reduction and cleavage sequencing (TRAC-Seq) (22) and identified tRNAs containing m7G modification at the “RRRGGT” sequence motif (Fig. 5A and Dataset S2). Our data revealed that m7G modification levels in tRNAs are reduced in Wdr4R215L/R215L mouse brain, as reflected by the decreased cleavage scores (Fig. 5 B and C). In addition, Wdr4 mutation decreases the expression of the majority of m7G tRNAs without disrupting the expression of non_m7G tRNAs (Fig. 5 D and E). These results were further confirmed by northern blot analysis of m7G tRNAs including ValAAC, ProAGG, and LysCTT (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

Wdr4 point mutation leads to impaired m7G tRNA modification, decreased mRNA translation, and elevated ER stress. (A) Motif sequence of tRNAs m7G modification site identified by TRAC-seq. (B) Representative images showing the decreased cleavage scores at indicated tRNA. (C) tRNA m7G modification levels analyzed by TRAC-seq. (D) Changes of m7G-modified tRNA expression levels in Wdr4 mutated brain. (E) Relative expression profile of m7G-modified tRNAs. (F) Northern blotting analysis and quantification of m7G-modified tRNAs (n = 3). U6 snoRNA was used as a loading control. (G) Puromycin intake assay and quantification of the global translation levels in mouse brain (n = 3). (H) Volcano plots showing genes with different translation efficiency (TE) in mouse brains (n = 3). TE was calculated by dividing the polysome-mRNA sequencing signals to input mRNA sequencing signals. (I) m7G-related codons frequency in TE up, TE down, and nonsignificant TE change genes (others). (J and K) Gene ontology and KEGG pathway analysis with TE down genes. The top 10 enriched pathways are ranked by P-value. (L) qPCR analysis of the TE down genes (n = 3 mice/group). (M) Western blot and quantification of signals with indicated antibodies (n = 3). (N) Volcano plots showing genes with different mRNA expression levels in mouse brains. (O) Gene ontology analysis with up-regulated genes. The top 10 enriched pathways are ranked by P-value. (P) qPCR assay of stress response genes (n = 3). (Q) Western blot of ER stress markers. (R) Representative IHC images of microglia marker Iba-1 in the cerebellum from mice at indicated postnatal days. (Scale bar, 200 μm.) The red arrow pointed out an example of brown staining microglia cell. Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using the unpaired t test (C, D, G, and P), one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (I) or two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (F, L, and M). n.s.P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Since tRNAs are involved in mRNA translation, we next performed puromycin intake assay to study the function of WDR4 in mRNA translation in the mouse brain. Results showed that Wdr4 mutation reduces the global translation activity in the mouse brain as reflected by lower intake of puromycin (Fig. 5G). We further applied polyribosome-bound mRNA sequencing (Polysome-seq) to profile the mRNA TE in mouse brain (Fig. 5H and Dataset S3). Our analysis showed that the TE down genes carried higher frequency of m7G-modified tRNA decoded codons (Fig. 5 I). The change of TE ratio (Wdr4R215L/R215L/Wdr4+/+) is significantly associated with the m7G codon frequency, numbers, and CDS length of mRNAs, suggesting that m7G tRNA modification, m7G codon frequency, and numbers of mRNA cooperatively regulate mRNA translation (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C). Gene ontology analysis and pathway analysis showed that the TE down genes are involved in cellular response to the stress process, brain development, and mTOR signaling pathway (Fig. 5 J and K). Further analysis revealed that the mRNAs of genes involved in mTOR signaling including Rictor, Pik3r1, and Akt, contain high number of m7G codons, thus may contribute to their more preferentially regulation in the Wdr4 mutated mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). qPCR and western blot further confirmed the impaired TE and the decreased protein levels of genes involved in mTOR signaling (Fig. 5 L and M). Furthermore, our RNA sequencing revealed that genes involved in cellular stress response are up-regulated in the mouse brain upon Wdr4 mutation (Fig. 5 N and O and Dataset S4). Consistently, qPCR and western blot showed that mutation of Wdr4 resulted in upregulation of ER stress response genes and elevated level of phosphorylated IRE1 and PERK (Fig. 5 P and Q). Activation of residual AKT with SC79 decreases the level of phosphorylated PERK and eIF2a and the proapoptotic proteins Bax and Bim (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). These data are consistent with the critical role of mTOR pathway in maintaining brain homeostasis and promotion of survival by regulation of ER stress response (23, 24). It was reported that elevated neural ER stress is associated with activation of microglia (25). Our data showed that Iba1-positive microglia underwent rapid expansion in Wdr4R215L/R215L cerebellum since postnatal day 35 (Fig. 5R and SI Appendix, Fig. S2 F and G), which is consistent with the gradual pathogenesis of cerebellar atrophy. Taken together, these data indicate that Wdr4 point mutation leads to reduced levels of tRNAs modified at position 46 with m7G, mRNA translation, which elevates cellular stress and increases cell apoptosis in the mouse brain.

TUDCA Treatment Rescues the Brain Functions of the Mice with Impaired tRNA m7G Modification.

We next aimed to develop therapeutic intervention strategies for therapy of patients with impaired tRNA m7G modification. Given that impaired tRNA m7G modification caused by Wdr4 mutation leads to cell death in the brain via elevating cellular stress genes, we explored the therapeutic effect of TUDCA, an FDA-approved drug that can ameliorate cellular stress, on Wdr4R215L/R215L mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S6A). Our data showed that treatment with TUDCA every other day significantly improves the brain weight and brain size in Wdr4R215L/R215L mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 B–E). TUNEL staining revealed reduced cell death in the Wdr4 mutated cerebellum after 8 wk of TUDCA treatment (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 F and G). TUDCA treatment also reduces the expression of cell stress markers and proapoptosis genes (SI Appendix, Fig. S6 H and I). Most importantly, TUDCA treatment significantly improves the neural functions of Wdr4R215L/R215L mice, as demonstrated by decreased traversal time and step errors in the beam balance test (Movie S3, and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 J and K), and obviously increased latency to fall in the rotarod tests (SI Appendix, Fig. S6L). Taken together, our data suggest that TUDCA treatment rescues the brain functions of mice with impaired tRNA m7G modification, suggesting that TUDCA could be a promising therapeutic drug for treatment of WDR4 mutated patients.

Long-Term Therapeutic Intervention of Mice with Impaired tRNA Modifications.

Though TUDCA treatment can significantly reverse the brain degeneration in Wdr4 mutated mice, the treatment process requires repeated usage of TUDCA every other day. Therefore, we further explored simple, long-lasting therapeutic strategies for treatment of diseases with impaired tRNA modifications. Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-PHPeB can introduce efficient and long-term expression of transgenes in brains, so we used AAV-PHPeB to restore WDR4 function in Wdr4 mutated (Wdr4R215L/R215L) mouse (AAV-WDR4) (Fig. 6A). Our data showed that AAV-PHPeB can efficiently infect the mouse brains, as demonstrated by the fact that one-time injection of AAV-PHPeB viruses can achieve high expression of virus-containing EGFP 8 wk after injection (Fig. 6B). Further analysis showed that AAV-PHPeB mediated transduction of wild-type WDR4 expression notably restores the levels of METTL1 (Fig. 6 C and D), m7G tRNA modification, and m7G tRNA expression (Fig. 6 E and F). These data demonstrate that restoration of wild-type WDR4 expression can successfully elevate METTL1 expression and restore the levels of m7G tRNA modification and expression in Wdr4R215L/R215L mice.

Fig. 6.

Long-term therapeutic intervention of mice with impaired tRNA modifications. (A) Schematic diagram of AAV treatment. (B) Representative images of mouse brains 8 wk after AAV infection. GFP indicated the successful AAV infection in the mouse brain. (Scale bar, 2,000 μm.) (C) Representative METTL1 IHC staining images of mouse cerebellum at sagittal section 8 wk after AAV infection. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (D) Western blot analysis and quantification of the expression levels of METTL1 and WDR4 in mouse brains 8 wk after AAV infection (n = 4). (E) Analysis of the tRNA m7G modification and expression levels in mouse brains 8 wk after AAV infection. (F) Quantitative comparison of tRNA m7G modification levels and m7G tRNAs expression levels between different groups (n = 3). (G) Brain weights of mice 8 wk after AAV infection (n = 6). (H and I) Measurements of brain sizes from A–P axis and M-L axis length of mouse forebrains 8 wk after AAV infection (n = 6). (J) Representative HE staining images of the whole mouse brains at sagittal section 8 wk after AAV infection. (K) Latency time before the mice fell in the rotarod test 8 wk after AAV infection (n = 6 mice /group). (L and M) Traversal time and number of step errors that the mice slipped to the side of beam in the beam balance test 8 wk after AAV injection (n = 6). Data are presented as mean ± SEM and analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (D), or one-way ANOVA (H–K) or two-way ANOVA (F, L, and M) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. n.s.P > 0.05, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

We further evaluated the therapeutic effect of AAV-PHPeB-WDR4 in treatment of diseases caused by WDR4 mutations. Our data revealed that the brain size and brain weight of Wdr4R215L/R215L mice are notably increased 8 wk after AAV-PHPeB-WDR4 infection (Fig. 6 G–I). HE staining demonstrated that AAV-PHPeB-WDR4 notably improves the cerebellum size of Wdr4R215L/R215L mice, supporting that AAV-PHPeB-WDR4 can alleviate the neural degeneration phenotypes caused by Wdr4 point mutation (Fig. 6J). Most importantly, AAV-PHPeB-WDR4 significantly improves the neural functions of Wdr4 mutated mice, as demonstrated by obviously increased latency to fall in the rotarod test (Fig. 6K) and drastically decreased traversal time and step errors in the beam balance test (Movie S4 and Fig. 6 L and M). Taken together, our data demonstrate that one-time transduction of AAV-PHPeB-WDR4 can achieve long-lasting therapeutic effect in Wdr4R215L/R215L mice, supporting that AAV-PHPeB mediated gene transduction can be an effective therapeutic strategy for treatment of neural degeneration diseases caused by impaired tRNA modifications/functions.

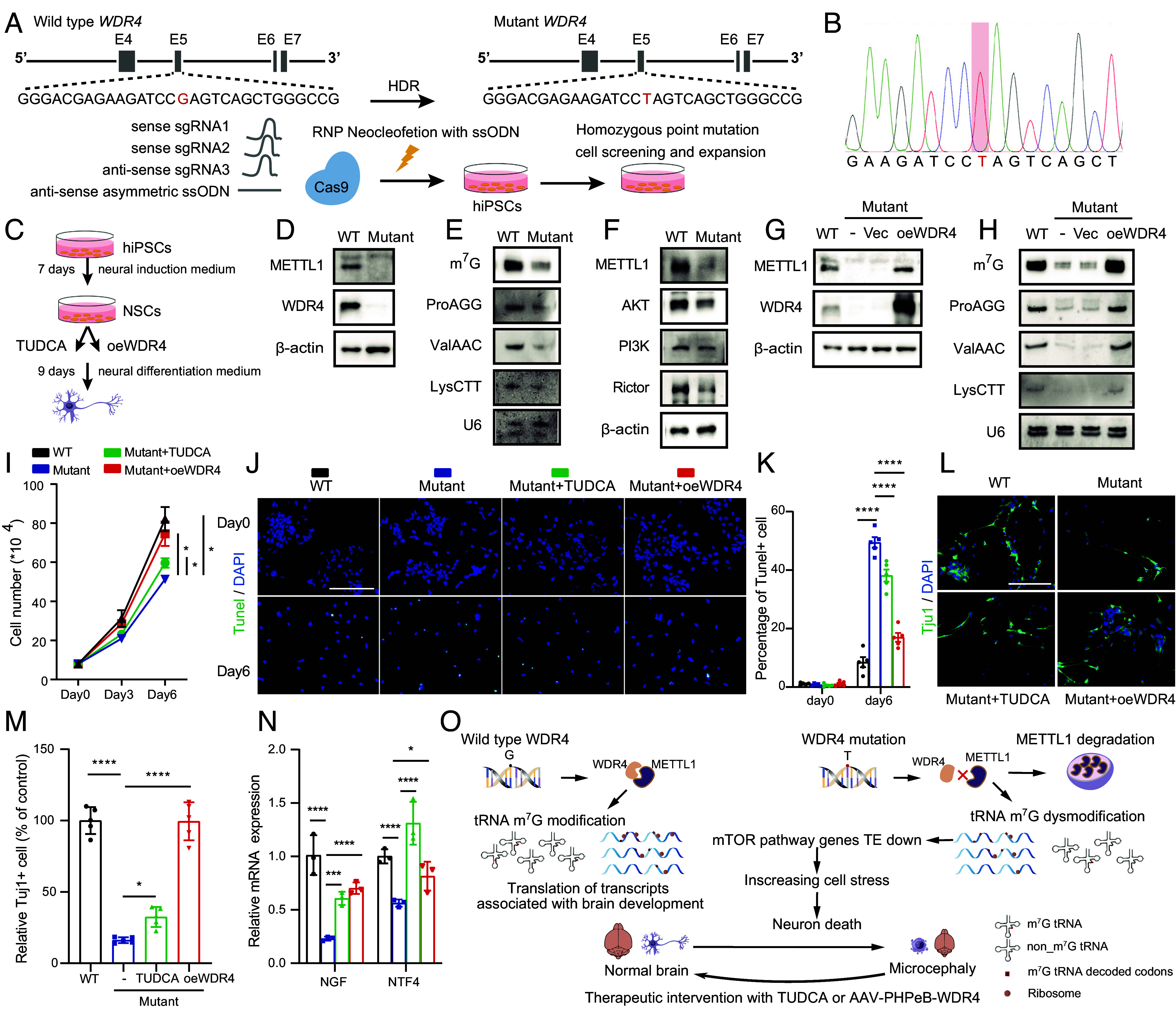

TUDCA Treatment or Restoration of Wild-Type WDR4 Improves the Survival and Functions of Human iPSCs-Derived NSCs Harboring WDR4-R170L Mutation.

To further explore the therapeutic effect of the above two strategies in humans, we established the hiPSCs that harbor the patient’s WDR4 mutation (NM_033661.4:c.509G > T, R170L) (Fig. 7 A and B). Since WDR4 point mutation leads to severe neurological dysfunctions in humans, we further induced differentiation of hiPSCs into NSCs to evaluate the effect of WDR4-R170L mutation on human neurons (Fig. 7C). Our data showed that WDR4 point mutation decreases the levels of WDR4, METTL1 protein, and m7G modified tRNAs, leading to the impaired protein expression of their downstream targets AKT, PI3K, and Rictor in human NSCs (Fig. 7 D–F). In addition, restoration of wild-type WDR4 notably increases the levels of METTL1, m7G tRNA modification, and m7G tRNA expression (Fig. 7 G and H). Functionally, we found that WDR4-R170L mutation impairs the proliferation of human NSCs, and TUDCA treatment or reexpression of wild-type WDR4 significantly improves the proliferation of WDR4-R170L mutated human NSCs (Fig. 7I). Moreover, both TUDCA treatment and restoration of wild-type WDR4 can significantly alleviate the apoptosis of WDR4 mutated NSCs during neural differentiation (Fig. 7 J and K), leading to the increased number of functional Tuj1 positive cells at the end of neural differentiation (Fig. 7 L–N). We also tried to restore the mutant WDR4 protein in NSCs since WDR4-R170L mutation leads to a dramatic decrease in WDR4 protein levels in human NSCs (Fig. 7D). However, WDR4R170L restoration fails to rescue the expression of METTL1, tRNAs m7G modification levels and the proliferation of NSCs (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). Taken together, these data further support that TUDCA treatment or restoration of wild-type WDR4 significantly improves the survival and functions of human NSCs that harbor the patient’s WDR4 mutation, supporting that these strategies could be promising for treatment of human neural degeneration diseases caused by impaired tRNA modifications/functions.

Fig. 7.

TUDCA treatment or restoration of wild-type WDR4 improves the survival and functions of human iPSCs-derived NSCs harboring WDR4 mutation. (A) Schematic diagram of generation of human iPSCs with patient-derived WDR4 point mutation. HDR: homology-directed repair. (B) Sanger sequencing showed the mutated site of the WDR4 gene in hiPSCs. (C) Schematic diagram of NSCs induction and experiment design. (D) Western blot analysis of the expression levels of METTL1 and WDR4 in human NSCs. (E) Analysis of the tRNA m7G modification and expression levels in human NSCs. (F) Western blot analysis of the expression levels of genes involved in mTOR pathway. (G) Western blot analysis of the expression levels of METTL1 and WDR4 in human NSCs after wild-type WDR4 reexpression. (H) Analysis of the tRNA m7G modification and expression levels in human NSCs after wild-type WDR4 restoration. (I) Cell proliferation analysis of human NSCs. (J) Representative TUNEL staining images of NSCs on neuron differentiation day 0 and day 6. (Scale bar, 200 μm.) (K) Quantification of TUNEL+ cells in NSCs undergoing neuron differentiation. (L and M) Representative Tuj1 staining images and quantification of Tuj1+ cells of NSCs on day 9 after neuron differentiation. (Scale bar, 200 μm.) (N) qPCR analysis of the mRNA expression level of neurotrophic factors in NSCs on day 9 after neuron differentiation. (O) The schematic model of the role and underlying mechanism and therapeutic intervention of WDR4 mutation in neural diseases. Data are presented as mean ± SD and analyzed using one-way ANOVA (M) or two-way ANOVA (I, K, and N) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

Mutations of tRNA modification and processing enzymes or impaired tRNA functions are frequently associated with brain malfunctions and neural developmental disorders (26, 27), while the underlying pathogenetic mechanisms are still poorly understood. Development of effective therapeutic intervention strategies for treatment of this large group of patients is urgently needed. m7G modification is a highly abundant tRNA modification that is conserved across different species (10). Mutations of WDR4 are reported in patients with neural disorders, suggesting strong relevance between WDR4 mutation and neural diseases (9, 14–16). In this study, we constructed a Wdr4 point mutation mouse model and human NSCs to study the pathogenic function and mechanism of WDR4 mutation found in patients (NM_033661.4:c.509G > T). Our study found that Wdr4R215L/R215L in mice leads to temporal and cell-type-specific degeneration in the brain and recapitulates human patient symptoms including impaired movement and intellectual capacities (9, 14–16). These data provide strong evidence supporting that WDR4 point mutation directly causes developmental disorders and intellectual disability in patients.

Wdr4R215L/R215L mice exhibit growth retardation, smaller brain, and suffer from severe movement disorders and impaired intellectual capacities. A recent study using the neural-specific Wdr4 knockout mouse model revealed that Wdr4 knockout leads to impaired cerebellar development and granule neuron progenitor proliferation (20), which is consistent with what we found in the Wdr4R215L/R215L mice. Similarly, the neural-specific Wdr4 knockout does not cause increased apoptosis in the cerebellum at postnatal day 7 (20). We also showed that, before postnatal day 21 (P21), no obvious apoptosis could be found in the cerebellum of Wdr4R215L/R215L mice, but notable apoptosis occurs after P21, which eventually leads to severe cerebellar atrophy at two months after birth. We found that METTL1 and WDR4 expression gradually increase after birth and also METTL1 is expressed at a higher level in the cerebellum than in other regions of the brain (Figs. 3A and 4C), thus the spatial-temporal expression patterns of METTL1/WDR4 could lead to the gradual pathogenic process of cerebellar atrophy.

Interestingly, the human and mouse with equivalent WDR4 point mutation are different in the onset of symptoms: human patients with WDR4-R170L mutation show severe growth defects and motor development disorders as early as 4 mo old (9), while the Wdr4R215L/R215L mice exhibit relatively normal movement capabilities at 4 wk of age, which is roughly equivalent to 3- to 10-y-old in humans. Also, mouse WDR4-R215L mutation does not disturb the mRNA and protein level of WDR4 in the mouse brain; however, the homologous mutation in human NSCs causes a notable reduction of the WDR4 protein without significantly decreasing the WDR4 mRNA level (Fig. 7D and SI Appendix, Fig. S8A), suggesting the potential discrepancy between the equivalent WDR4 point mutation in the mouse and human. Amino acid sequence analysis revealed that mouse WDR4 has an additional 43 amino acid peptide in its N terminal, which is an interesting divergence from its human ortholog (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 B and C). IUPRED2A (https://iupred2a.elte.hu/) predicts there is an additional intrinsically disordered region in the N terminal of mouse WDR4 protein compared to the human WDR4 protein (SI Appendix, Fig. S8D), which may provide itself higher affinity to specific targets and enhance its stability and leads to additional molecular functions (28). The additional N terminal disordered region of mouse WDR4 is enriched with positive charged R and K amino acids, which can form sold bond and ionic bond with other amino residues to enhance protein stability (29). Also, the additional N terminal region of mouse WDR4 could have additional molecular functions and thus result in the differences in the onset of symptoms between the mouse and human.

Mechanistically, WDR4-R170L mutation destabilizes METTL1 through proteasome protein degradation. It’s previously reported that WDR4 knockout leads to decreased METTL1 expression in both yeast and human cells (11, 30), while the underlying mechanism was unknown. The role of WDR4-R170 in METTL1–WDR4 Complex formation is controversial possibly due to the differences in the analysis structure model used. In yeast, the corresponding residue K223 (R170) of Trm82 (homolog of WDR4) is speculated to form a salt bridge with residue E204 (E183) of Trm8 (homolog of METTL1 (9). A recent study also confirmed that R170 of human WDR4 interacted with residues of METTL1 (19). However, two different studies reported that the R170 of human WDR4 does not interact with METTL1 but mediates intramolecular WDR4 interactions to build a scaffold for intermolecular interactions (17, 18). Our analysis of the structure of METTL1–WDR4 complex revealed that R170 of WDR4 forms a hydrogen bond with E183 of METTL1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). In addition, our co-IP assay further confirmed the crucial role of R170 of WDR4 in the interaction between METTL1–WDR4 (Fig. 4F). Despite the controversy on WDR4-R170 in the METTL1–WDR4 direct interaction, all of these studies and our data support that R170 of WDR4 is essential for the MTase activity of METTL1–WDR4 complex.

Our translation profiling data showed that loss of m7G modification reduced the TE of genes that involved in cellular stress response, including mTOR signaling genes Rictor and Akt. The mTOR pathway is a key regulator of neural development. Knockout or mis-regulation of mTOR pathway components leads to neurodegeneration diseases including microcephaly (23, 31, 32). Neural-specific conditional knockout of Rictor leads to severe microcephaly starting at birth and impairment of motor function (23), which is similar to the phenotypes observed in the Wdr4R215L/R215L mice. In addition, Rictor deletion and AKT inactivation leads to the activation of the ER stress response markers PERK–eIF2a phosphorylation, and increases the cell susceptibility to ER stress (24). Our data revealed that loss of m7G modification leads to decreased translation efficiencies and the protein levels of Rictor and Akt (Fig. 5 L and M), and increased PERK–eIF2a phosphorylation (Fig. 5Q). To test whether modulation of mTOR pathway affects ER stress in the Wdr4 mutant mouse model, we treated the Wdr4R215L/R215L mice with SC79, a specific and blood–brain barrier permeable AKT activator (33), to activate the residual AKT in vivo. Our data showed that activation of residual AKT by SC79 can decrease the PERK–eIF2a phosphorylation in the Wdr4R215L/R215L mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), suggesting that loss of m7G modification decreases the translation of mTOR signaling genes, which could lead to upregulation of ER stress response proteins and apoptosis in the Wdr4R215L/R215L mice.

Our data revealed that WDR4 point mutation leads to elevating cellular stress response genes and increased neural cell apoptosis. It has been reported that mis-regulated stress response results in apoptosis and causes neurological deficiency (34, 35). We therefore explored whether targeting the aberrantly elevated stress could ameliorate the neural degeneration phenotypes caused by WDR4 mutation. Our data revealed that TUDCA, an FDA-approved stress-releasing drug, significantly alleviates neuron apoptosis in WDR4 mutated human NSCs during differentiation and Wdr4 mutated mouse brain, and improved the movement abilities of the Wdr4 mutated mice, suggesting that TUDCA could be an effective therapeutic drug for treatment of patients with WDR4 mutations. Moreover, considering that mis-regulations of other tRNA modifications also lead to elevated stress and neural diseases (36, 37), TUDCA could have broad application for therapy of a wide range of neural diseases caused by mis-regulated tRNA modification and processing.

Gene therapy is a promising strategy for effective therapy of various diseases, especially for those caused by genetic mutations. We therefore used the Adeno-associated virus (AAV)-PHPeB to restore wild-type WDR4 expression in the Wdr4 mutated mice. Our data showed that AAV-PHPeB could efficiently introduce wild-type WDR4 expression, which restores the expression of METTL1 and m7G tRNA modifications. Functionally, AAV-PHPeB-WDR4 successfully improves the brain size, brain morphology, and neural functions in the Wdr4 mutated mice. Restoration of wild-type WDR4 in human WDR4 mutated NSCs also obtains similar results and improve the functions of human NSCs. Our data demonstrated that a single dose of AAV-PHPeB-WDR4 injection can achieve long-lasting therapeutic effect in Wdr4 mutated mice, providing a proof-of-principal example of using AAV-PhPeB gene therapy for various neural developmental diseases.

Gene involved in tRNA processing and modification are frequently mis-regulated and closely related to developmental diseases. Similar to WDR4 mutation, the mutations in genes involved in tRNA splicing endonuclease complex including CLP1, TSEN54, TSEN2 cause pontocerebellar hypoplasia, which is characterized with atrophy or hypoplasia of the cerebellum (38–40). Thus, the pathogenic mechanism and therapeutic strategies found in this study could be broadly extended for the study and therapy of various tRNA-related diseases. Overall, our study uncovers molecular insights underlying the pathogenesis of WDR4 mutation and develops two therapeutic strategies for the intervention of neural disease caused by impaired tRNA m7G modification (Fig. 7O), which could potentially benefit the clinical treatment of patients with tRNA-related diseases.

Materials and Methods

Detailed description of standard methods is in SI Appendix.

Animals.

C57BL/6N Wdr4 mutated knock-in (mKI) mice with NM_021322.2 c.664G > T mutation were generated using CRISPR-Cas9 system by Biocytogen Co., Ltd (Beijing, China). All experiments were carried out with the approval of the Ethics Committees of The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University. All behavioral assays were conducted during the daytime.

Generation of Human iPSCs and NSCs Harboring Patient-Derived WDR4 Mutation.

The deidentified human iPSCs harboring the patient-derived WDR4 point mutation (NM_033661.4:c.509G > T; p.(Arg 170Leu)) were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 system mediated homology-directed genome editing. Details are shown in SI Appendix. Human NSCs were induced from human iPSCs by culturing iPSCs in neural induction medium (A1647801, Thermo fisher) for 7 d according to the manufacturer’s instruction. After that, NSCs were culture in NSCs expansion medium (Neurobasal medium:Advanced™ DMEM/F-12:GIBCO® neuroinduction supplement = 49:49:2).

Adeno-Associated Virus Infection.

AAV2/PHP.eB-hSyn-EGFP-P2A-Wdr4-WPRE-pA containing wild-type WDR4 gene (AAV-WDR4) were purchased from Taitool Bioscience, Shanghai, China, to restore wild-type WDR4 gene expression in the mouse brain. AAV2/PHP.eB-hSyn-EGFP-3Flag-WPRE-pA (AAV-Vec) was used as negative control. Viruses were intravenously injected into the mouse on postnatal day 21 at a dose of 2.5 × 10 11 v.g per mouse. Mice were subjected to behavior tests 1 wk after virus infection and killed 8 wk later.

Animal Behavior Test, TRAC-seq, RNC-seq, RNA-seq, and snRNA-seq.

Standard methods were used, see SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Represented video of beam balance test of WT and WDR4 mutated mouse.

Represented video showing swimming performance of WT and WDR4 mutated mouse.

Represented video of beam balance test of WDR4 mutated mice with or without TUDCA treatment.

Represented video of beam balance test of WDR4 mutated mice with or without AAV-WDR4 treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFE0138700 to S.L., 2022YFA1105300 to S.L., and 2021YFC2700904 to Y.F.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82200954 to J.M., 82325036 to S.L., 82071723 to Y.F., and 82201734 to C.Z.), Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong (2021A1515111032 to J.M. and 2021B1515020069 to S.L.), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Sun Yat-sen University (23ykzy004 to S.L.), National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and Information and Communications Technology) (NRF-2020R1C1C1009842, NRF-2020R1A4A1018398, and NRF-2022K1A3A1A20014671 to J.C.).

Author contributions

J.C., Q.Y., Y.F., C.Z., and S.L. designed research; J.M., S.Z., C.A., Q.L., Y.H., S.G., Z.W., W.W., Y.S., Y.J., and C.Y. performed research; J.M., S.Z., H.H., G.X., and S.C. analyzed data; and J.M. and S.L. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission R.I.G. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Contributor Information

Yong Fan, Email: yongfan011@gzhmu.edu.cn.

Canfeng Zhang, Email: zhangcf6@mail2.sysu.edu.cn.

Shuibin Lin, Email: linshb6@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

TRAC-seq, RNC-seq, RNA-seq, and snRNA-seq datasets generated during this study are being deposited at GEO and are available under accession number GEO: GSE229612 (41).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Delaunay S., Helm M., Frye M., RNA modifications in physiology and disease: Towards clinical applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 25, 104–122 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackman J. E., Alfonzo J. D., Transfer RNA modifications: Nature’s combinatorial chemistry playground. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 4, 35–48 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.El Yacoubi B., Bailly M., de Crecy-Lagard V., Biosynthesis and function of posttranscriptional modifications of transfer RNAs. Annu. Rev. Genet. 46, 69–95 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orellana E. A., et al. , METTL1-mediated m(7)G modification of Arg-TCT tRNA drives oncogenic transformation. Mol. Cell 81, 3323–3338.e3314 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai Z., et al. , N(7)-Methylguanosine tRNA modification enhances oncogenic mRNA translation and promotes intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma progression. Mol. Cell 81, 3339–3355.e3338 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma J., et al. , METTL1/WDR4-mediated m(7)G tRNA modifications and m(7)G codon usage promote mRNA translation and lung cancer progression. Mol. Ther. 29, 3422–3435 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freude K., et al. , Mutations in the FTSJ1 gene coding for a novel S-adenosylmethionine-binding protein cause nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75, 305–309 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guy M. P., et al. , Defects in tRNA anticodon loop 2’-o-methylation are implicated in nonsyndromic X-linked intellectual disability due to mutations in FTSJ1. Hum. Mutat. 36, 1176–1187 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shaheen R., et al. , Mutation in WDR4 impairs tRNA m(7)G46 methylation and causes a distinct form of microcephalic primordial dwarfism. Genome Biol. 16, 210 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tomikawa C., 7-Methylguanosine modifications in transfer RNA (tRNA). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 4080 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alexandrov A., Grayhack E. J., Phizicky E. M., tRNA m7G methyltransferase Trm8p/Trm82p: Evidence linking activity to a growth phenotype and implicating Trm82p in maintaining levels of active Trm8p. RNA 11, 821–830 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alexandrov A., Martzen M. R., Phizicky E. M., Two proteins that form a complex are required for 7-methylguanosine modification of yeast tRNA. RNA 8, 1253–1266 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexandrov A., et al. , Rapid tRNA decay can result from lack of nonessential modifications. Mol. Cell 21, 87–96 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Braun D. A., et al. , Mutations in WDR4 as a new cause of Galloway–Mowat syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 176, 2460–2465 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X., et al. , Speech and language delay in a patient with WDR4 mutations. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 61, 468–472 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trimouille A., et al. , Further delineation of the phenotype caused by biallelic variants in the WDR4 gene. Clin. Genet. 93, 374–377 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruiz-Arroyo V. M., et al. , Structures and mechanisms of tRNA methylation by METTL1-WDR4. Nature 613, 383–390 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J., et al. , Structural basis of regulated m(7)G tRNA modification by METTL1-WDR4. Nature 613, 391–397 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin X., et al. , Structural insight into how WDR4 promotes the tRNA N7-methylguanosine methyltransferase activity of METTL1. Cell Discov. 9, 65 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu P. R., et al. , Wdr4 promotes cerebellar development and locomotion through Arhgap17-mediated Rac1 activation. Cell Death Dis. 14, 52 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin S., et al. , Mettl1/Wdr4-mediated m(7)G tRNA methylome is required for normal mRNA translation and embryonic stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Mol. Cell 71, 244–255.e245 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin S., Liu Q., Jiang Y. Z., Gregory R. I., Nucleotide resolution profiling of m(7)G tRNA modification by TRAC-Seq. Nat. Protoc. 14, 3220–3242 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomanetz V., et al. , Ablation of the mTORC2 component rictor in brain or Purkinje cells affects size and neuron morphology. J. Cell Biol. 201, 293–308 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tenkerian C., et al. , mTORC2 balances AKT activation and eIF2alpha serine 51 phosphorylation to promote survival under stress. Mol. Cancer Res. 13, 1377–1388 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harvey L. D., et al. , Administration of DHA reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated inflammation and alters microglial or macrophage activation in traumatic brain injury. ASN Neuro 7, 1759091415618969 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawer H., et al. , Roles of elongator dependent tRNA modification pathways in neurodegeneration and cancer. Genes 10, 19 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tahmasebi S., Khoutorsky A., Mathews M. B., Sonenberg N., Translation deregulation in human disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 791–807 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uversky V. N., Gillespie J. R., Fink A. L., Why are “natively unfolded” proteins unstructured under physiologic conditions? Proteins 41, 415–427 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang J., Weng H., Ding W., Kang Z., N-terminal engineering of glutamyl-tRNA reductase with positive charge arginine to increase 5-aminolevulinic acid biosynthesis. Bioengineered 8, 424–427 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Z., et al. , METTL1 promotes hepatocarcinogenesis via m(7) G tRNA modification-dependent translation control. Clin. Transl. Med. 11, e661 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long H. Z., et al. , PI3K/AKT signal pathway: A target of natural products in the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 12, 648636 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heras-Sandoval D., Pérez-Rojas J. M., Hernández-Damián J., Pedraza-Chaverri J., The role of PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway in the modulation of autophagy and the clearance of protein aggregates in neurodegeneration. Cell Signal. 26, 2694–2701 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jo H., et al. , Small molecule-induced cytosolic activation of protein kinase Akt rescues ischemia-elicited neuronal death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 10581–10586 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhu P. J., et al. , Activation of the ISR mediates the behavioral and neurophysiological abnormalities in Down syndrome. Science 366, 843–849 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saxena S., Cabuy E., Caroni P., A role for motoneuron subtype-selective ER stress in disease manifestations of FALS mice. Nat. Neurosci. 12, 627–636 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huber S. M., Leonardi A., Dedon P. C., Begley T. J., The versatile roles of the tRNA epitranscriptome during cellular responses to toxic exposures and environmental stress. Toxics 7, 17 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blanco S., et al. , Aberrant methylation of tRNAs links cellular stress to neuro-developmental disorders. EMBO J. 33, 2020–2039 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Monaghan C. E., Adamson S. I., Kapur M., Chuang J. H., Ackerman S. L., The Clp1 R140H mutation alters tRNA metabolism and mRNA 3’ processing in mouse models of pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2110730118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cassandrini D., et al. , Pontocerebellar hypoplasia: Clinical, pathologic, and genetic studies. Neurology 75, 1459–1464 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Namavar Y., et al. , Clinical, neuroradiological and genetic findings in pontocerebellar hypoplasia. Brain 134, 143–156 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma J., Zheng S., Lin S., Pathogenic mechanism and therapeutic intervention of impaired N7-methylguanosine. GEO database. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE229612. Deposited 13 April 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Dataset S01 (XLSX)

Dataset S02 (XLSX)

Dataset S03 (XLSX)

Dataset S04 (XLSX)

Represented video of beam balance test of WT and WDR4 mutated mouse.

Represented video showing swimming performance of WT and WDR4 mutated mouse.

Represented video of beam balance test of WDR4 mutated mice with or without TUDCA treatment.

Represented video of beam balance test of WDR4 mutated mice with or without AAV-WDR4 treatment.

Data Availability Statement

TRAC-seq, RNC-seq, RNA-seq, and snRNA-seq datasets generated during this study are being deposited at GEO and are available under accession number GEO: GSE229612 (41).