Abstract

BACKGROUND

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a leading cause of chronic liver disease with a significant risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Recent clinical evidence indicates the potential benefits of statins in cancer chemoprevention and therapeutics. However, it is still unclear if these drugs can lower the specific risk of HCC among patients with MASLD.

AIM

To investigate the impact of statin use on the risk of HCC development in patients with MASLD.

METHODS

A systematic review and meta-analysis of all the studies was performed that measured the effect of statin use on HCC occurrence in patients with MASLD. The difference in HCC risk between statin users and non-users was calculated among MASLD patients. We also evaluated the risk difference between lipophilic versus hydrophilic statins and the effect of cumulative dose on HCC risk reduction.

RESULTS

A total of four studies consisting of 291684 patients were included. MASLD patients on statin therapy had a 60% lower pooled risk of developing HCC compared to the non-statin group [relative risk (RR) = 0.40, 95%CI: 0.31-0.53, I2 = 16.5%]. Patients taking lipophilic statins had a reduced risk of HCC (RR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.28-0.64), whereas those on hydrophilic statins had not shown the risk reduction (RR = 0.57, 95%CI: 0.27-1.20). The higher (> 600) cumulative defined daily doses (cDDD) had a 70% reduced risk of HCC (RR = 0.30, 95%CI: 0.21-0.43). There was a 29% (RR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.55-0.91) and 43% (RR = 0.57, 95%CI: 0.40-0.82) decreased risk in patients receiving 300-599 cDDD and 30-299 cDDD, respectively.

CONCLUSION

Statin use lowers the risk of HCC in patients with MASLD. The higher cDDD and lipophilicity of statins correlate with the HCC risk reduction.

Keywords: Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Statins, Lipophilic statin, Hydrophilic statin, Meta-analysis

Core Tip: Current clinical evidence regarding the effect of statins on lowering the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) among patients with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is inconclusive. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of all the studies that evaluated the impact of statins on HCC occurrence in MASLD patients. The pooled data from four studies involving 291684 patients was included in the final analysis. Our findings show that statin use reduces the risk of HCC among patients with MASLD. The use of higher cumulative defined daily doses and lipophilic statins results in a significant reduction in HCC risk.

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the most common chronic liver disease worldwide[1-3]. A recent meta-analysis revealed the global prevalence of MASLD has increased from 25.3% (1990–2006) to 38.2% (2016–2019)[4]. Studies have shown that patients with MASLD have an increased incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)[5-9]. A systematic review showed that the HCC incidence in MASLD patients with and without cirrhosis at 10 years was up to 15% and 2.7%, respectively[10]. It is critical to understand that MASLD not only increases HCC risk but also liver cancer-related mortality[11]. A nationwide study from the United States found that HCC patients with alcoholic liver disease and MASLD as causes had significantly higher mortality rates than those with viral etiologies[12]. Furthermore, MASLD-associated HCC (MASLD-HCC) has a lower survival rate compared to hepatitis C virus-related HCC[13-15]. MASLD has also been linked to a lower reception of HCC surveillance, decreasing the detection of cancer in its early stages[16]. A Swedish multigenerational cohort study also revealed that first-degree relatives of MASLD patients had significantly increased hazards of HCC, major adverse hepatic outcomes, and liver-associated mortality[17]. The growing evidence of this troubling association has led to the curation of prevention strategies aimed at reducing HCC occurrence among MASLD patients[18-21]. While several modifiable risk factors are identified for MASLD-HCC, interest has also increased in the potential cancer chemopreventive role of certain widely used drugs[22].

Statins are a common class of drugs used for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular diseases[23,24]. These drugs also inhibit the growth of tumor cells through varied pharmacological activities and regulation of the methyl-valerate pathway[25-28]. Consequently, statins are among the most studied chemopreventive agents, potentially reducing the risk of cancers of the breast, prostate, pancreas, and liver[29-33]. Despite initial safety concerns, subsequent research has proven the safety and efficacy of these medications in patients with liver disease, especially MASLD[34-37]. With regard to their chemopreventive effects against HCC, previous studies have predominantly evaluated patient populations other than MASLD[38-42]. Therefore, the role of statin treatment in MASLD-HCC risk reduction has remained largely underinvestigated. A recent meta-analysis has reported that statin use decreases the HCC incidence among patients with MASLD[43]. However, the data on the clinical benefit of statins stratified by solubility status and doses is still incongruous. To our knowledge, this is the first meta-analysis to assess the variation in HCC risk in patients with MASLD between statin users and non-users. We also aim to calculate the risk difference between hydrophilic and lipophilic statins, as well as the effect of cumulative dose on HCC risk reduction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data search and screening

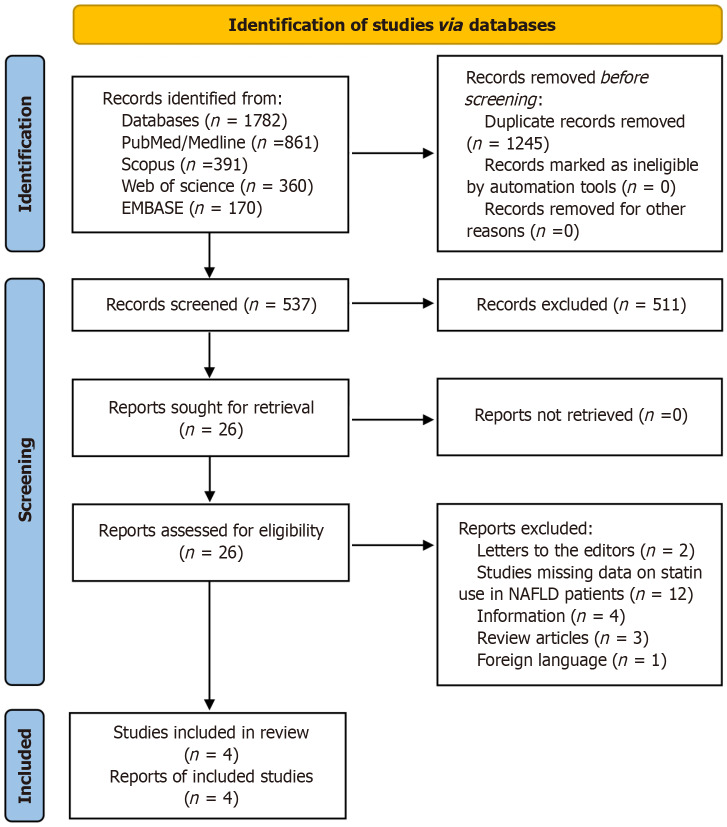

The meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis statement[44]. We performed a detailed search of electronic medical databases, including MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, and Scopus, from January 1990 to June 2023. The following keywords were used in different combinations: (1) Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase inhibitors OR HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors OR statins OR atorvastatin OR cerivastatin OR fluvastatin OR simvastatin OR lovastatin OR pitavastatin OR pravastatin OR rosuvastatin; (2) NAFLD OR nonalcoholic fatty liver disease OR NASH OR nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; and (3) HCC OR hepatocellular carcinoma OR liver cancer. Only articles in the English language were included. A manual bibliographic search of the included articles was also performed to find any missing studies. The search strategy in the current study is outlined (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis flow diagram of the search strategy.

Study selection and data extraction

Three researchers (Tarar ZI, Inayat F, and Gandhi M) independently searched for eligibility and screened abstracts, titles, and full manuscripts without the use of automation tools. Any disagreement was resolved through discussion with the senior author (Ali AH). Three reviewers (Tarar ZI, Inayat F, and Gandhi M) extracted data on an Excel sheet. The data on study design, year of publication, country of study, first authors, patient demographics, type and duration of statin use, study quality, and outcome measures were extracted. A fourth reviewer (Farooq U) reviewed the extracted data, and the final datasheet was drafted after a discussion between all four authors.

Eligibility criteria

The Population, Intervention, Control, and Outcome (PICO) framework was used to formulate the inclusion criteria as described in the Cochrane Collaboration Handbook[45,46]. The PICO characteristics for eligibility were: (1) Population: Patients older than 18 years with a history of MASLD; (2) Intervention: Use of statin therapy; (3) Comparison group: Statin non-users; and (4) Outcome: Risk of HCC development.

We excluded studies in which the underlying etiology of cirrhosis was a chronic liver disease other than MASLD, such as hereditary, alcohol-related, viral, and autoimmune causes.

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the risk stratification for HCC among MASLD patients between statin users and non-users. We performed a subgroup analysis to examine the effect of lipophilic versus hydrophilic statins on HCC risk. We further analyzed the dose-dependent effect of statin on the risk of HCC development.

Statistical analysis

The random-effects model was used to calculate the pooled hazard ratios (HR) along with a 95%CI. Cochrane χ² and I2 were applied to assess the heterogeneity and variance. Forest plots were used to present the results of the meta-analysis. The funnel plot and Egger’s test for asymmetry were used to determine the publication bias. We utilized Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software version 3.0 (Biostat Inc., Englewood, NJ, United States) to conduct the analysis.

Quality assessment

We relied on the Methodological Index for Nonrandomized Studies (MINORS) criteria for assessing the quality of the included studies[47]. We scored comparative studies on 12 items of the MINORS criteria, and each item was scored from 0 to 2: (1) 0 if not reported; (2) 1 when reported but inadequate; and (3) 2 when reported and adequate. Therefore, a maximum ideal score of 24 could be obtained for comparative studies and 16 for non-comparative studies.

RESULTS

Literature search and study selection

A total of 1782 citations were found in the initial literature search; 1245 articles were removed as duplicates. We screened the remaining 537 reports and shortlisted 26 articles deemed relevant to our study question. These 26 articles were retrieved, and a comprehensive review was undertaken. Four studies were included in the final analysis[48-51]. The total number of patients was 291684. Of these, 80246 were statin users, and 211438 were not under therapy with statins. The mean age of the study population was 57.0 ± 12.2 years. The gender distribution of included patients showed that 46.9% (136804) were male and 53.1% (154880) were female. Three studies were retrospective cohorts, and one was a case-control (Table 1)[48-51]. The three studies provided the outcome data in HR, whereas one study reported results as odds ratios (OR). We converted the OR results of this study to relative risk (RR) prior to its inclusion in the final analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies

|

Ref.

|

Study design

|

Age (years)

|

Total patients (n)

|

Males/females

|

Statin users

|

Non-users

|

Cirrhosis

|

No cirrhosis

|

Follow-up (years)

|

| Zou et al[51] | Cohort | 52.1 ± 14.7 | 272430 | 126804/145626 | 73384 | 199046 | 34257 | 238173 | 727390 person-year |

| Pinyopornpanish et al[50] | Cohort | 59 ± 10.4 | 1072 | 432/640 | 440 | 632 | 950 | 122 | 4326 person-year |

| German et al[49] | Case-control | 64.3 ± 13.1 | 102 | 66/36 | 40 | 62 | 93 | 9 | Not applicable |

| Lee et al[48] | Cohort | 52.7 (41.6-64.4) | 18080 | 9502/8578 | 6382 | 11698 | 0 | 18080 | 6.32 (3.04-10.10) |

Outcomes

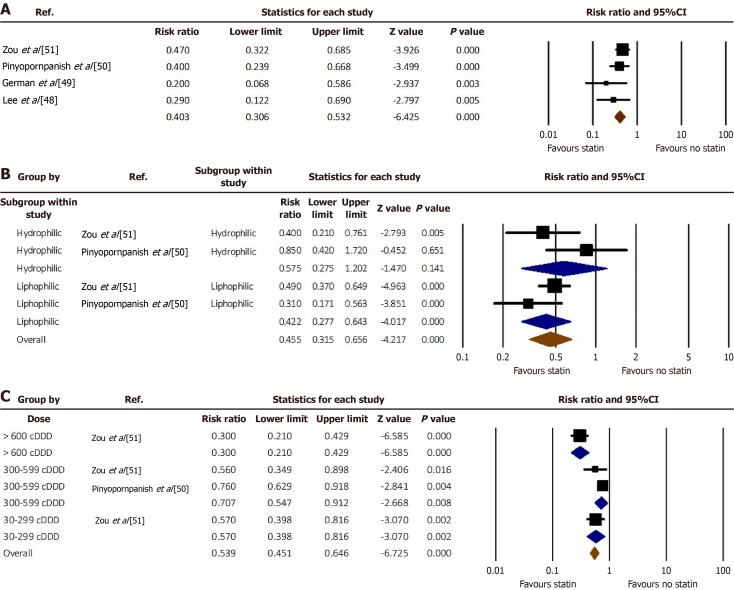

Patients with MASLD who were on statin therapy had a 60% less pooled risk of developing HCC compared to the non-statin group (RR = 0.40, 95%CI: 0.31-0.53, I2 = 16.5%) (Figure 2A)[48-51]. We performed a subgroup analysis of lipophilic versus hydrophilic statins reported in two studies. Lipophilic statins were associated with a lower risk of HCC (RR = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.28-0.64). No statistically significant difference was noted among hydrophilic statin users (RR = 0.57, 95%CI: 0.27-1.20) (Figure 2B)[50,51].

Figure 2.

Forest plot. A: The risk difference of hepatocellular carcinoma among MASLD patients between statin users versus non-users; B: The risk difference of hepatocellular carcinoma among users of lipophilic versus hydrophilic statins; C: The dose-dependent risk reduction of hepatocellular carcinoma among statin users. cDDD: Cumulative defined daily doses.

Dose-dependent risk reduction

We analyzed the data based on the dose of statins and concluded that > 600 cumulative defined daily doses (cDDD) decrease the risk of HCC by 70% (RR = 0.30, 95%CI: 0.21-0.43). The administration of 300-599 cDDD and 30-299 cDDD of statins decreases the risk by 29% (RR = 0.71; 95%CI: 0.55-0.91) and 43% (RR = 0.57; 95%CI: 0.40-0.82), respectively (Figure 2C)[50,51].

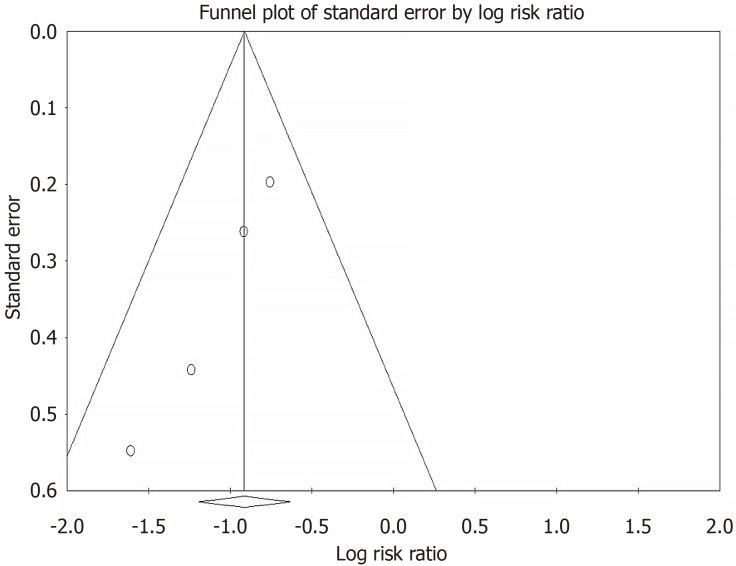

Publication bias and quality assessment

A funnel plot and Egger's test were used to ascertain publication bias. There was no evidence of significant publication bias among the studies included in our final analysis (Figure 3). Using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, all studies were determined to have a low risk of bias.

Figure 3.

Funnel plot for publication bias.

Risk of bias assessment

Based on MINORS criteria for non-randomized studies, the quality of studies was classified as poor (score ≤ 5), fair (score 6-10), or high quality (score ≥ 11), as described previously[52]. All the studies were rated as high quality. The quality assessment of the studies is summarized in Supplementary Table 1.

DISCUSSION

This meta-analysis has comprehensively assessed the impact of statin use on HCC risk in patients with MASLD. We included four observational studies. Our findings are summarized as follows: (1) Statin use reduces the risk of HCC in patients with MASLD; (2) Lipophilic statins are more potent in lowering the risk of HCC compared to hydrophilic statins; and (3) The risk reduction with cDDD of statin follows a U-shaped curve.

Liver cancer is a major contributor to the global cancer burden, and its incidence rate has increased in recent decades. According to the Global Cancer Statistics, HCC of the liver parenchyma is the sixth most frequently diagnosed cancer worldwide, with approximately 865269 new cases reported in 2022[53]. With a 5-year survival rate of only 18%, liver cancer constitutes the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with over 757948 deaths in 2022[53,54]. MASLD is the fastest-growing cause of HCC in several countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, and France[55]. Global MASLD-HCC case numbers are projected to increase significantly due to the rapidly rising MASLD prevalence rates[56,57]. This warrants a concerted effort to reduce the incidence of HCC in MASLD by exploring the impact of lifestyle modification and chemoprevention[58,59]. Current clinical evidence indicates a growing interest in the chemopreventive role of statin therapy[60].

Our results show that statin therapy significantly reduces the risk of HCC in MASLD patients. Statin use has previously been linked to a lower risk of HCC in the general population[61]. These agents have also resulted in a similar clinical benefit in patient populations with diabetes and cirrhosis[62,63]. However, the data regarding chemopreventive effects of statins for MASLD-HCC has remained inconclusive. MASLD is closely associated with metabolic syndrome, which consists of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and obesity. These conditions lead to systemic inflammation and raise the HCC risk, likely by activating oncogenic pathways[64]. Lipid accumulation in MASLD causes a number of cellular derangements, including lipotoxicity, endoplasmic reticulum stress, and the generation of reactive oxygen species leading to DNA damage resulting in oncogenesis[65,66]. The antineoplastic effect of statin occurs through both hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase-dependent and independent pathways. Clinical evidence shows that lipid-lowering agents other than statins have fewer anticancer effects[67]. Despite their established safety in MASLD, statins remain underused in this patient population[68-70]. Therefore, our meta-analysis highlights the importance of statin usage in patients with MASLD in the context of HCC prevention.

We noted that lipophilic statins were associated with a higher reduction in the risk of HCC among MASLD patients. The use of hydrophilic statins had no significant effect on HCC risk reduction. A Swedish prospective cohort study also reported an association between lipophilic statins and reduced 10-year HCC incidence and death among patients with viral hepatitis-related chronic liver disease[71]. In contrast, two meta-analyses reported that the beneficial effect of statins in lowering the risk of HCC was similar for both hydrophilic and lipophilic statins[72,73]. Pre-clinical studies revealed the effectiveness of lipophilic statins in preventing viral replication, potentiating antiviral therapy, and stimulating antitumor immunity compared to hydrophilic statins[74]. Kato et al[75] described reduced surface expressions of anion transporter proteins in hepatocytes during inflammation and carcinogenesis, preventing hydrophilic statins from penetrating the cells. Lipophilic statins readily diffuse across the cell membrane and induce potent antitumor effects through G0/G1 cell cycle arrest and suppression of the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway[75].

The higher doses of statin (cDDD > 600) correlated with a greater risk reduction of HCC in our analysis. The beneficial effects plummeted with the cDDD of 300-599 but increased again with the lower cDDD. Congruent to our findings, Tsan et al[76] found that a high dose duration of the statin product was associated with greater hepatoprotective effects in the hepatitis B cohort. Similarly, a meta-analysis showed increasing cDDD of statins resulted in HCC risk reduction in general as well as at-risk non-MASLD populations, confirming a dose-dependent effect[72]. A retrospective study from the United States based on 9135 chronic hepatitis C patients also substantiated a dose-dependent reduction in incident cirrhosis and HCC[77]. A nationwide, nested case-control study from the Republic of Korea found a dose-dependent risk reduction, with doses greater than 720 cDDD showing greater clinical effectiveness[78]. In a Taiwanese study, statin usage also dose-dependently reduced the incidence of HCC, decompensation, and death in cirrhosis patients[79]. On the other hand, a few studies have revealed that a higher dose of statin has no significant benefit over a lower dose in HCC prevention[80,81]. However, these studies had limitations such as a small sample size and inclusion of patients with several different types of cancer. Therefore, further population-based studies are warranted to determine the dose effect of statins on MASLD-HCC prevention.

Our meta-analysis has several strengths. We examined the use of statins specifically in patients with MASLD, avoiding the heterogeneity of patient populations with other high-risk liver conditions. We conducted a detailed literature search of all the major databases and a manual search of the bibliographies of the included studies. Furthermore, three investigators searched and screened the databases separately, and a fourth reviewer approved the final studies included in the analysis. Our meta-analysis consists of four studies, but the combined total number of patients was sufficiently large. Finally, we used a random-effects model to provide a more conservative pooled estimate. This meta-analysis is unique as it offers pooled evidence regarding HCC risk stratified by solubility status and doses of statins in patients with MASLD. Therefore, it may provide guidance for future clinical trial design that would form the basis for deriving an effective HCC prevention strategy in these patients. A recent literature review found that statins had the strongest clinical evidence currently available among all the chemopreventive agents for MASLD-HCC[82]. While the effect of statins requires further evaluation, an expert panel supports their regular use for HCC prevention in patients with MASLD[83].

Limitations

The small number of included studies constituted a major limitation. Moreover, the non-randomized, observational nature of the studies could result in bias due to flaws in study selection criteria, design, and the presence of confounding factors, including the concurrent use of other drugs, comorbidities, activity status, and genetic predisposition. It could potentially make it difficult to prove that statins alone were responsible for the protective effect against HCC in these patients. However, an updated meta-analysis has recently indicated that only statin use was significant for HCC chemoprevention in subgroup analyses accounting for concurrent drugs such as aspirin and metformin[84]. Large-scale randomized prospective trials are required to further evaluate the effects of statins on HCC prevention in the MASLD population.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluates the difference in HCC risk between MASLD patients on statin treatment and those who did not receive these medications. Based on the available data, our findings conclude that the use of statins lowers the risk of HCC in patients with MASLD. Lipophilic statins are found to be more potent in reducing the risk of HCC compared to hydrophilic statins. The reduction in risk with cDDD of statin follows a U-shaped curve. Further reliable research with a rigorous study design is required to confirm our results in the future.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors report no relevant conflicts of interest for this article.

PRISMA 2020 Checklist statement: The authors have read the PRISMA 2020 Checklist, and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the PRISMA 2020 Checklist.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Pakistan

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B

Novelty: Grade A

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade B

P-Reviewer: Shousha HI S-Editor: Luo ML L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang L

Contributor Information

Zahid Ijaz Tarar, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Umer Farooq, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, St. Louis University, St. Louis, MO 63104, United States.

Faisal Inayat, Department of Internal Medicine, Allama Iqbal Medical College, Lahore, Punjab 54550, Pakistan. faisalinayat@hotmail.com.

Sanket D Basida, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Faisal Ibrahim, Department of Internal Medicine, Wexham Park Hospital, Wexham SL24HL, Slough, United Kingdom.

Mustafa Gandhi, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Gul Nawaz, Department of Internal Medicine, Allama Iqbal Medical College, Lahore, Punjab 54550, Pakistan.

Arslan Afzal, Department of Hospital Medicine, ECU Health Medical Center, Greenville, NC 27834, United States.

Ammad J Chaudhary, Department of Internal Medicine, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI 48202, United States.

Faisal Kamal, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA 19107, United States.

Ahmad H Ali, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

Yezaz A Ghouri, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65212, United States.

References

- 1.Le MH, Yeo YH, Li X, Li J, Zou B, Wu Y, Ye Q, Huang DQ, Zhao C, Zhang J, Liu C, Chang N, Xing F, Yan S, Wan ZH, Tang NSY, Mayumi M, Liu X, Liu C, Rui F, Yang H, Yang Y, Jin R, Le RHX, Xu Y, Le DM, Barnett S, Stave CD, Cheung R, Zhu Q, Nguyen MH. 2019 Global NAFLD Prevalence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:2809–2817. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong VW, Ekstedt M, Wong GL, Hagström H. Changing epidemiology, global trends and implications for outcomes of NAFLD. J Hepatol. 2023;79:842–852. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miao L, Targher G, Byrne CD, Cao YY, Zheng MH. Current status and future trends of the global burden of MASLD. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2024;35:697–707. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2024.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Younossi ZM, Golabi P, Paik JM, Henry A, Van Dongen C, Henry L. The global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): a systematic review. Hepatology. 2023;77:1335–1347. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang DQ, Singal AG, Kono Y, Tan DJH, El-Serag HB, Loomba R. Changing global epidemiology of liver cancer from 2010 to 2019: NASH is the fastest growing cause of liver cancer. Cell Metab. 2022;34:969–977. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2022.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tan DJH, Ng CH, Lin SY, Pan XH, Tay P, Lim WH, Teng M, Syn N, Lim G, Yong JN, Quek J, Xiao J, Dan YY, Siddiqui MS, Sanyal AJ, Muthiah MD, Loomba R, Huang DQ. Clinical characteristics, surveillance, treatment allocation, and outcomes of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:521–530. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00078-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shah PA, Patil R, Harrison SA. NAFLD-related hepatocellular carcinoma: The growing challenge. Hepatology. 2023;77:323–338. doi: 10.1002/hep.32542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Orci LA, Sanduzzi-Zamparelli M, Caballol B, Sapena V, Colucci N, Torres F, Bruix J, Reig M, Toso C. Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review, Meta-analysis, and Meta-regression. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:283–292. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2021.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tovo CV, de Mattos AZ, Coral GP, Sartori GDP, Nogueira LV, Both GT, Villela-Nogueira CA, de Mattos AA. Hepatocellular carcinoma in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis without cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:343–356. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i2.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reig M, Gambato M, Man NK, Roberts JP, Victor D, Orci LA, Toso C. Should Patients With NAFLD/NASH Be Surveyed for HCC? Transplantation. 2019;103:39–44. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Petrelli F, Manara M, Colombo S, De Santi G, Ghidini M, Mariani M, Iaculli A, Rausa E, Rampulla V, Arru M, Viti M, Lonati V, Ghidini A, Luciani A, Facciorusso A. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis: HCC and Steatosis or Steatohepatitis. Neoplasia. 2022;30:100809. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2022.100809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brar G, Greten TF, Graubard BI, McNeel TS, Petrick JL, McGlynn KA, Altekruse SF. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Survival by Etiology: A SEER-Medicare Database Analysis. Hepatol Commun. 2020;4:1541–1551. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Piscaglia F, Svegliati-Baroni G, Barchetti A, Pecorelli A, Marinelli S, Tiribelli C, Bellentani S HCC-NAFLD Italian Study Group. Clinical patterns of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A multicenter prospective study. Hepatology. 2016;63:827–838. doi: 10.1002/hep.28368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinmann A, Alt Y, Koch S, Nelles C, Düber C, Lang H, Otto G, Zimmermann T, Marquardt JU, Galle PR, Wörns MA, Schattenberg JM. Treatment and survival of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis associated hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:210. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1197-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi Y, Taherifard E, Saeed A, Saeed A. MASLD-Related HCC: A Comprehensive Review of the Trends, Pathophysiology, Tumor Microenvironment, Surveillance, and Treatment Options. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46:5965–5983. doi: 10.3390/cimb46060356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Henry-Blake C, Balachandrakumar V, Kassab M, Devonport J, Matthews C, Fox J, Baggus E, Henney A, Stern N, Cuthbertson DJ, Palmer D, Johnson PJ, Hughes DM, Hydes TJ, Cross TJS. Lower hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: Impact on treatment eligibility. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi: 10.1111/jgh.16727. 2024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ebrahimi F, Hagström H, Sun J, Bergman D, Shang Y, Yang W, Roelstraete B, Ludvigsson JF. Familial coaggregation of MASLD with hepatocellular carcinoma and adverse liver outcomes: Nationwide multigenerational cohort study. J Hepatol. 2023;79:1374–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2023.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motta BM, Masarone M, Torre P, Persico M. From Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis (NASH) to Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC): Epidemiology, Incidence, Predictions, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:5458. doi: 10.3390/cancers15225458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho Y, Kim BH, Park JW. Preventive strategy for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29:S220–S227. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2022.0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daher D, Seif El Dahan K, Rich NE, Tayob N, Merrill V, Huang DQ, Yang JD, Kulkarni AV, Kanwal F, Marrero J, Parikh N, Singal AG. Hepatocellular Carcinoma Screening in a Contemporary Cohort of At-Risk Patients. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e248755. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.8755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rivera-Esteban J, Muñoz-Martínez S, Higuera M, Sena E, Bermúdez-Ramos M, Bañares J, Martínez-Gomez M, Cusidó MS, Jiménez-Masip A, Francque SM, Tacke F, Minguez B, Pericàs JM. Phenotypes of Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease-Associated Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:1774–1789. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2024.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiao S, Liu Y, Fu X, Chen T, Xie W. Modifiable Risk Factors for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Am J Med. 2024:S0002–9343(24)00410. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2024.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marcus ME, Manne-Goehler J, Theilmann M, Farzadfar F, Moghaddam SS, Keykhaei M, Hajebi A, Tschida S, Lemp JM, Aryal KK, Dunn M, Houehanou C, Bahendeka S, Rohloff P, Atun R, Bärnighausen TW, Geldsetzer P, Ramirez-Zea M, Chopra V, Heisler M, Davies JI, Huffman MD, Vollmer S, Flood D. Use of statins for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in 41 low-income and middle-income countries: a cross-sectional study of nationally representative, individual-level data. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10:e369–e379. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00551-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Preventive Services Task Force, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, Cabana M, Chelmow D, Coker TR, Davis EM, Donahue KE, Jaén CR, Kubik M, Li L, Ogedegbe G, Pbert L, Ruiz JM, Stevermer J, Wong JB. Statin Use for the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2022;328:746–753. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.13044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vaklavas C, Chatzizisis YS, Tsimberidou AM. Common cardiovascular medications in cancer therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130:177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2011.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Freed-Pastor WA, Mizuno H, Zhao X, Langerød A, Moon SH, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, Barsotti A, Chicas A, Li W, Polotskaia A, Bissell MJ, Osborne TF, Tian B, Lowe SW, Silva JM, Børresen-Dale AL, Levine AJ, Bargonetti J, Prives C. Mutant p53 disrupts mammary tissue architecture via the mevalonate pathway. Cell. 2012;148:244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tripathi S, Gupta E, Galande S. Statins as anti-tumor agents: A paradigm for repurposed drugs. Cancer Rep (Hoboken) 2024;7:e2078. doi: 10.1002/cnr2.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaky MY, Fan C, Zhang H, Sun XF. Unraveling the Anticancer Potential of Statins: Mechanisms and Clinical Significance. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:4787. doi: 10.3390/cancers15194787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ricco N, Kron SJ. Statins in Cancer Prevention and Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:3948. doi: 10.3390/cancers15153948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang WT, Lin HW, Lin SH, Li YH. Association of Statin Use With Cancer- and Noncancer-Associated Survival Among Patients With Breast Cancer in Asia. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e239515. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.9515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C, Chen H, Hu B, Shi J, Chen Y, Huang K. New insights into the therapeutic potentials of statins in cancer. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1188926. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1188926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gohlke BO, Zincke F, Eckert A, Kobelt D, Preissner S, Liebeskind JM, Gunkel N, Putzker K, Lewis J, Preissner S, Kortüm B, Walther W, Mura C, Bourne PE, Stein U, Preissner R. Real-world evidence for preventive effects of statins on cancer incidence: A trans-Atlantic analysis. Clin Transl Med. 2022;12:e726. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xiao M, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Liu J, Li J, Xu H, Zhao Y, Yu X, Shi S. Functional significance of cholesterol metabolism in cancer: from threat to treatment. Exp Mol Med. 2023;55:1982–1995. doi: 10.1038/s12276-023-01079-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janicko M, Drazilova S, Pella D, Fedacko J, Jarcuska P. Pleiotropic effects of statins in the diseases of the liver. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:6201–6213. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i27.6201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho Y, Rhee H, Kim YE, Lee M, Lee BW, Kang ES, Cha BS, Choi JY, Lee YH. Ezetimibe combination therapy with statin for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an open-label randomized controlled trial (ESSENTIAL study) BMC Med. 2022;20:93. doi: 10.1186/s12916-022-02288-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou H, Toshiyoshi M, Zhao W, Zhao Y, Zhao Y. Statins on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 14 RCTs. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023;102:e33981. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000033981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai W, Xu B, Li P, Weng J. Statins for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Ther. 2023;30:e17–e25. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000001499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Wang W, Wang M, Shi J, Jia X, Dang S. A Meta-Analysis of Statin Use and Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;2022:5389044. doi: 10.1155/2022/5389044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wong YJ, Qiu TY, Ng GK, Zheng Q, Teo EK. Efficacy and Safety of Statin for Hepatocellular Carcinoma Prevention Among Chronic Liver Disease Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021;55:615–623. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lu MC, Chen CC, Lu MY, Lin KJ, Chiu CC, Yang TY, Fang YA, Jian W, Chen MY, Hsu MH, Lai YH, Yang TL, Hao WR, Liu JC. The Association between Statins and Liver Cancer Risk in Patients with Heart Failure: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:2959. doi: 10.3390/cancers15112959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kim G, Jang SY, Han E, Lee YH, Park SY, Nam CM, Kang ES. Effect of statin on hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with type 2 diabetes: A nationwide nested case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2017;140:798–806. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinn DH, Kang D, Park Y, Kim H, Hong YS, Cho J, Gwak GY. Statin use and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with chronic hepatitis B: an emulated target trial using longitudinal nationwide population cohort data. BMC Gastroenterol. 2023;23:366. doi: 10.1186/s12876-023-02996-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang J, Fu S, Liu D, Wang Y, Tan Y. Statin can reduce the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;35:353–358. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000002517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: a key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. 1995;123:A12–A13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas J, Kneale D, McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, Bhaumik S. Chapter 2: Determining the scope of the review and the questions it will address. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.4 (updated August 2023). United Kingdom: Cochrane, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712–716. doi: 10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee TY, Wu JC, Yu SH, Lin JT, Wu MS, Wu CY. The occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in different risk stratifications of clinically noncirrhotic nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Int J Cancer. 2017;141:1307–1314. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.German MN, Lutz MK, Pickhardt PJ, Bruce RJ, Said A. Statin Use is Protective Against Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Case-control Study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2020;54:733–740. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pinyopornpanish K, Al-Yaman W, Butler RS, Carey W, McCullough A, Romero-Marrero C. Chemopreventive Effect of Statin on Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:2258–2269. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000001347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zou B, Odden MC, Nguyen MH. Statin Use and Reduced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:435–444. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2022.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vanella G, Crippa S, Archibugi L, Arcidiacono PG, Delle Fave G, Falconi M, Capurso G. Meta-analysis of mortality in patients with high-risk intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms under observation. Br J Surg. 2018;105:328–338. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229–263. doi: 10.3322/caac.21834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang DQ, El-Serag HB, Loomba R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18:223–238. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Estes C, Anstee QM, Arias-Loste MT, Bantel H, Bellentani S, Caballeria J, Colombo M, Craxi A, Crespo J, Day CP, Eguchi Y, Geier A, Kondili LA, Kroy DC, Lazarus JV, Loomba R, Manns MP, Marchesini G, Nakajima A, Negro F, Petta S, Ratziu V, Romero-Gomez M, Sanyal A, Schattenberg JM, Tacke F, Tanaka J, Trautwein C, Wei L, Zeuzem S, Razavi H. Modeling NAFLD disease burden in China, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Spain, United Kingdom, and United States for the period 2016-2030. J Hepatol. 2018;69:896–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phoolchund AGS, Khakoo SI. MASLD and the Development of HCC: Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Challenges. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16:259. doi: 10.3390/cancers16020259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Inayat F, Ur Rahman Z, Hurairah A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Cureus. 2016;8:e754. doi: 10.7759/cureus.754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lange NF, Radu P, Dufour JF. Prevention of NAFLD-associated HCC: Role of lifestyle and chemoprevention. J Hepatol. 2021;75:1217–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sharpton SR, Loomba R. Emerging role of statin therapy in the prevention and management of cirrhosis, portal hypertension, and HCC. Hepatology. 2023;78:1896–1906. doi: 10.1097/HEP.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vell MS, Loomba R, Krishnan A, Wangensteen KJ, Trebicka J, Creasy KT, Trautwein C, Scorletti E, Seeling KS, Hehl L, Rendel MD, Zandvakili I, Li T, Chen J, Vujkovic M, Alqahtani S, Rader DJ, Schneider KM, Schneider CV. Association of Statin Use With Risk of Liver Disease, Hepatocellular Carcinoma, and Liver-Related Mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2320222. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.20222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.El-Serag HB, Johnson ML, Hachem C, Morgana RO. Statins are associated with a reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a large cohort of patients with diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1601–1608. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Singh S, Singh PP, Singh AG, Murad MH, Sanchez W. Statins are associated with a reduced risk of hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:323–332. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turati F, Talamini R, Pelucchi C, Polesel J, Franceschi S, Crispo A, Izzo F, La Vecchia C, Boffetta P, Montella M. Metabolic syndrome and hepatocellular carcinoma risk. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:222–228. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Margini C, Dufour JF. The story of HCC in NAFLD: from epidemiology, across pathogenesis, to prevention and treatment. Liver Int. 2016;36:317–324. doi: 10.1111/liv.13031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anstee QM, Reeves HL, Kotsiliti E, Govaere O, Heikenwalder M. From NASH to HCC: current concepts and future challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:411–428. doi: 10.1038/s41575-019-0145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Friis S, Poulsen AH, Johnsen SP, McLaughlin JK, Fryzek JP, Dalton SO, Sørensen HT, Olsen JH. Cancer risk among statin users: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:643–647. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) J Hepatol. 2024;81:492–542. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2024.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ho A, Kiener T, Nguyen QN, Le QA. Effect of statin use on liver enzymes and lipid profile in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) J Clin Lipidol. 2024;18:e501–e508. doi: 10.1016/j.jacl.2024.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang S, Ren X, Zhang B, Lan T, Liu B. A Systematic Review of Statins for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Safety, Efficacy, and Mechanism of Action. Molecules. 2024;29:1859. doi: 10.3390/molecules29081859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Simon TG, Duberg AS, Aleman S, Hagstrom H, Nguyen LH, Khalili H, Chung RT, Ludvigsson JF. Lipophilic Statins and Risk for Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Death in Patients With Chronic Viral Hepatitis: Results From a Nationwide Swedish Population. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:318–327. doi: 10.7326/M18-2753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang Y, Liu Q, Zhou Z, Ding Y, Yang M, Xu W, Chen K, Zhang Q, Wang Z, Li H. Can Statin Treatment Reduce the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2020;19:1533033820934881. doi: 10.1177/1533033820934881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Islam MM, Poly TN, Walther BA, Yang HC, Jack Li YC. Statin Use and the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:671. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Syed GH, Amako Y, Siddiqui A. Hepatitis C virus hijacks host lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kato S, Smalley S, Sadarangani A, Chen-Lin K, Oliva B, Brañes J, Carvajal J, Gejman R, Owen GI, Cuello M. Lipophilic but not hydrophilic statins selectively induce cell death in gynaecological cancers expressing high levels of HMGCoA reductase. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1180–1193. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00771.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsan YT, Lee CH, Wang JD, Chen PC. Statins and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:623–630. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simon TG, Bonilla H, Yan P, Chung RT, Butt AA. Atorvastatin and fluvastatin are associated with dose-dependent reductions in cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, among patients with hepatitis C virus: Results from ERCHIVES. Hepatology. 2016;64:47–57. doi: 10.1002/hep.28506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim G, Jang SY, Nam CM, Kang ES. Statin use and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients at high risk: A nationwide nested case-control study. J Hepatol. 2018;68:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chang FM, Wang YP, Lang HC, Tsai CF, Hou MC, Lee FY, Lu CL. Statins decrease the risk of decompensation in hepatitis B virus- and hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis: A population-based study. Hepatology. 2017;66:896–907. doi: 10.1002/hep.29172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chiu HF, Ho SC, Chen CC, Yang CY. Statin use and the risk of liver cancer: a population-based case–control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:894–898. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Friedman GD, Flick ED, Udaltsova N, Chan J, Quesenberry CP Jr, Habel LA. Screening statins for possible carcinogenic risk: up to 9 years of follow-up of 361,859 recipients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2008;17:27–36. doi: 10.1002/pds.1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dickinson A, Dinani A, Wegermann K. Chemoprevention of hepatocellular carcinoma associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease: An updated review. Hepatoma Res. 2024;10:37. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Loomba R, Lim JK, Patton H, El-Serag HB. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Screening and Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1822–1830. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.12.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zeng RW, Yong JN, Tan DJH, Fu CE, Lim WH, Xiao J, Chan KE, Tan C, Goh XL, Chee D, Syn N, Tan EX, Muthiah MD, Ng CH, Tamaki N, Lee SW, Kim BK, Nguyen MH, Loomba R, Huang DQ. Meta-analysis: Chemoprevention of hepatocellular carcinoma with statins, aspirin and metformin. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;57:600–609. doi: 10.1111/apt.17371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]