Abstract

Objective

Five definitions of clinical instability have been published to assess the appropriateness and safety of discharging patients hospitalised for pneumonia. This study aimed to quantify the level of agreement between these definitions and estimate their discriminatory accuracy in predicting post-discharge adverse events.

Study design and setting

We conducted a retrospective cohort study involving 1038 adult patients discharged alive following hospitalisation for pneumonia.

Results

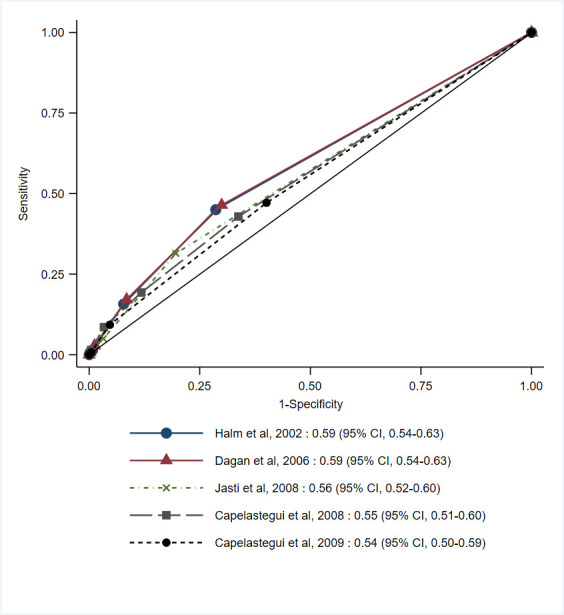

The prevalence of unstable criteria within 24 hours before discharge was 4.5% for temperature >37.8°C, 13.8% for heart rate >100/min, 1.0% for respiratory rate >24/min, 2.6% for systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg, 3.3% for oxygen saturation <90%, 5.4% for inability to maintain oral intake and 6.4% for altered mental status. The percentage of patients classified as unstable at discharge ranged 12.8%–41.0% across different definitions (Fleiss Kappa coefficient, 0.47; 95% CI 0.44 to 0.50). Overall, 140 (13.5 %) patients experienced adverse events within 30 days of discharge, including 108 unplanned readmissions (10.4%) and 32 deaths (3.1%). Clinical instability was associated with a 1.3-fold to 2.0-fold increase in the odds of postdischarge adverse events, depending on the definition, with c-statistics ranging 0.54–0.59 (p=0.31).

Conclusion

Clinical instability was associated with higher odds of 30-day postdischarge adverse events according to all but one of the published definitions. This study supports the validity of definitions that combine vital signs, mental status and the ability to maintain oral intake within 24 hours prior to discharge to identify patients at a higher risk of postdischarge adverse events.

Keywords: pneumonia, clinical epidemiology

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Published definitions of clinical instability at discharge for pneumonia show moderate agreement.

The omission of important predictors, inconsistent thresholds for dichotomised continuous parameters and variations in scoring systems explain the heterogeneity in the discriminatory accuracy across definitions of clinical instability.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Definitions that combine vital signs, mental status and ability to maintain oral intake should be used to assess the appropriateness and safety of discharge of patients with pneumonia.

Introduction

Annually, over 700 000 adults in the USA are hospitalised with a primary diagnosis of pneumonia. In addition to 9% of patients who die in hospitals,1 approximately 15% of pneumonia hospitalisation survivors are readmitted,2 3 and 9% die within 30 days of discharge.1 Given the patient safety issues and cost implications of these postdischarge adverse events, short-term mortality and unplanned readmission rates have been designated as publicly available core hospital quality measures, with financial penalties for underperforming hospitals in the USA and Western Europe.4 5

Premature discharge contributes to one in five potentially avoidable readmissions in general medicine6 and community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) patients.7 A significant number of readmissions could be prevented by evaluating patients’ readiness for discharge regarding recovery from symptoms and clinical instability. Current guidelines advocate assessing the resolution of vital sign abnormalities to guide the discharge decision.8,10 Assessing the stability of vital signs 24 hours before discharge is a simple, objective way to determine the appropriateness and safety of discharge.11

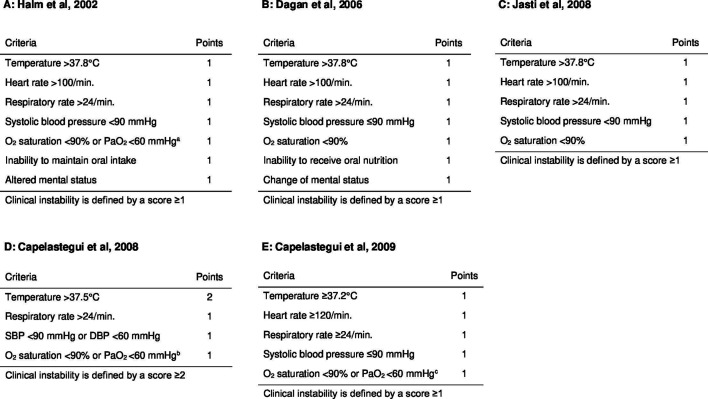

Five definitions of clinical instability at discharge for patients with CAP have been published, based on different thresholds and clinical features, including temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygenation, mental status and the ability to maintain oral intake (figure 1).12,16 These definitions were developed without external validation of their performance concerning discrimination or calibration. The prevalence of clinical instability at discharge ranged 10%–36%, with inconsistent OR estimates for readmissions (range, 0.56–1.76) or mortality (range, 2.08–7.00), across primary studies.12,17 Whether these disparate findings reflect heterogeneous clinical instability criteria, inconsistent study outcomes, failure to account for the competing risk of death or varying severity of illness across primary studies is unknown. A large-scale, head-to-head comparison in the same study sample would provide information on the agreement and accuracy of the clinical instability definitions.18,20

Figure 1. Definitions of clinical instability at discharge from hospitalisation for community-acquired pneumonia. (A) Definition of clinical instability according to Halm et al15;(B) Definition of clinical instability according to Dagan et al14; (C) Definition of clinical instability according to Jasti et al16 ; (D) Definition of clinical instability according to Capelastegui et al12 (E) Definition of clinical instability according to Capelastegui et al13 a Patients receiving supplemental oxygen via face mask were considered to have stable oxygenation if they had an oxygen saturation rate of ≥95%. Patients who used home-based oxygen before admission were not considered to have unstable oxygenation at discharge. b Patients who were receiving supplemental oxygen with a fraction of inspired oxygen ≤24% or no more than 1 L/min of oxygen via nasal cannula, were considered to be stable at discharge if their oxygen saturation rate was ≥95%. Patients who used home-based oxygen before admission were not considered to have unstable oxygenation at discharge. c Patients receiving supplemental oxygen via a face mask or nasal prongs were considered to have unstable oxygenation. DBP, diastolic blood pressure; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

We aimed to quantify the level of agreement between published definitions of clinical instability at discharge and estimate their comparative accuracy in predicting the occurrence of adverse events within 30 days of discharge. We hypothesised that heterogeneous definitions of clinical instability would be associated with different prevalence rates of instability at discharge and discriminatory accuracy.

Methods

Study design

Using individual participant data from a retrospective cohort study, we analysed consecutive adult patients who survived hospitalisation for CAP at two acute care hospitals in France in 2014. The design and primary results of the original study have been reported elsewhere.7 21 In this observational study, no specific intervention was assigned to the patients, and the discharge decision was made autonomously by physicians.

Research ethics approval

An institutional review board (Comité de Protection des Personnes Sud-Est V, Grenoble, France; 15 July 2014; no approval number) reviewed and approved the study protocol and informed consent form before the study began. The study database was approved by the Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l'Information en matière de Recherche dans le domaine de la Santé (CCTIRS, Paris, France; approval number 14.586bis) and authorised by the French Data Agency (Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés, Paris, France; authorisation number DR-2015–161).22

Patients

Potentially eligible patients were identified from hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of pneumonia, or respiratory failure or sepsis combined with a secondary diagnosis of pneumonia. Patients were included based on a medical record notation of a pneumonia diagnosis or a medical record notation of ≥1 respiratory symptom (cough, sputum production, dyspnoea, tachypnoea or pleuritic pain), ≥1 auscultation finding (rales or crepitation) and ≥1 sign of infection (temperature >38°C, shivering or white cell count >10 000/µL or <4000/µL) and a new infiltrate on chest radiography or CT performed within 48 hours of admission.

Hospital-acquired pneumonia, defined as pneumonia that was not present at the time of admission and occurred 48 hours or more after admission, was not within the scope of this study. We excluded patients who died during the index hospitalisation, those who were admitted from or transferred to another acute care hospital, and those residing outside France.

Only the first hospitalisation was included as an index pneumonia admission for individuals with multiple pneumonia admissions during the study period. Additional pneumonia admissions within 1 year of discharge from the index pneumonia hospitalisation were considered readmissions and excluded as index admissions (in other words, a single admission could not be counted both as an index admission and as a readmission for another index admission).

Data collection

Trained clinical research assistants conducted a structured chart review using a computerised case report form. They gathered detailed information on demographics, comorbidities, physical examination findings, relevant laboratory test results and the pneumonia severity index (PSI)23 on admission as well as processes of care, hospital course and length of stay. According to the strategy used in the original derivation and validation studies,23 24 missing values for nursing home residence (n=9 (0.8%)), respiratory rate (n=579 (55.8%)), systolic blood pressure (n=5 (0.5%)), temperature (n=6 (0.6%)), pulse rate (n=6 (0.6%)), pH (n=383 (36.9%)), blood urea nitrogen (n=27 (2.6%)), sodium (n=17 (1.6%)), glucose (n=190 (18.3%)), hematocrit (n=18 (1.7%)), PaO2 (n=383 (36.9%)), oxygen saturation (n=31 (3.0%)) and pleural effusion (n=30 (2.9%)) on admission were imputed at zero for computing PSI.

Additionally, we collected information on mental status, ability to maintain oral intake and vital signs, including the most abnormal values for heart rate, respiratory rate, temperature, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, arterial oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry and partial pressure of arterial oxygen recorded within 24 hours before discharge from the index hospitalisation.

Clinical instability at discharge

Five definitions of clinical instability at discharge, published between 2002 and 200912,16 were identified as part of a systematic review (protocol registered with PROSPERO 2017 CRD42017071531). Using original data from the retrospective chart review, we classified patients as clinically stable or unstable at discharge according to each definition.

We utilised the scoring systems and thresholds reported in the primary studies to define clinical instability (figure 1). For four out of five primary studies,13,16 clinical instability was defined by one or more instability among five to seven clinical features including temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, oxygenation, mental status and ability to maintain oral intake. The exception was the scoring system published by Capelastegui et al (2008),12 which defined clinical instability by a score ≥2 based on one major criterion (temperature >37.5°C, 2 points) and three minor criteria (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure <60 mm Hg, respiratory rate >24 breaths/min and oxygen saturation <90% and/or PaO2 <60 mm Hg, 1 point each).

In the primary analysis, we performed a single imputation of the missing data by replacing them with normal values (ie, zero imputation). This approach was based on the assumption that clinicians selectively documented vital signs at discharge, with a higher likelihood of recording in the presence of positive or abnormal findings.25 To investigate the pattern of missing data, we assessed the frequency of missing values for each variable and analysed the different missing patterns. We also examined the relationship between variables with and without missing values to gain insight into the mechanism behind missing data.

Study outcome

The primary outcome measure for postdischarge adverse events was a composite of unplanned readmission or death within 30 days of discharge, whichever occurred first. Individuals who died after readmission were counted once for the primary outcome. Our primary outcome combined unplanned readmission with death to prevent bias caused by censoring deaths when evaluating readmissions alone.26 27 The secondary outcomes included unplanned readmission and death within 30 days of discharge, considered as independent outcomes.

Readmission was defined as inpatient admission to the index hospital within 30 days of discharge from pneumonia hospitalisation. We were unable to track readmissions to other hospitals.21 Readmissions were classified as unplanned if they resulted from acute clinical events requiring hospitalisation that were not arranged or scheduled at time of discharge. As previously reported,7 four panellists independently assigned the primary reasons for unplanned readmissions using the 11 categories described by Halfon et al.28

Emergency department visits not leading to hospital readmissions were also documented, although they did not contribute to the primary and secondary study outcomes.27 Follow-up information on mortality was obtained from chart reviews and the National Death Index. The follow-up period was extended to 11 February 2015.

Statistical analysis

Summary descriptive statistics for baseline patient characteristics and study outcome measures were reported as numbers and percentages for categorical variables and medians with 25th and 75th percentiles (IQR) for continuous variables. We estimated the overall and leave-one-out Fleiss kappa coefficients29 to quantify the level of agreement among the five definitions of clinical instability at discharge. The degree of agreement was characterised by comparing the coefficient value against a benchmark scale ranging from 0 (indicating agreement expected by chance) to 1 (indicating perfect agreement).30 To assess the robustness of our findings, we examined the consistency with alternative chance-corrected agreement coefficients.31

Univariable logistic regression was employed to calculate the unadjusted OR point estimates, with 95% CI of postdischarge adverse events associated with clinical instability at discharge. Discriminatory accuracy in predicting postdischarge adverse events was quantified for each definition of clinical instability using the c-statistic.20 32 Consistent with published primary studies, c-statistic estimates were derived based on the score calculated according to Capelastegui et al (2008) and the number of instabilities for the four other definitions. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values and likelihood ratio estimates were reported for each definition of clinical instability.

Additional analyses were conducted to assess the findings’ robustness. First, we repeated our primary analysis after imputing missing values using multivariate imputation with chained equations (MICE). MICE was chosen for its ability to handle arbitrary patterns of missing data and provides flexibility to simultaneously impute variables of different types with a separate conditional distribution for each imputed variable. Prediction equations were specified using predictive mean matching for heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, temperature, oxygen saturation, partial pressure of arterial oxygen, oxygen flow, and logistic regression for supplemental oxygen, home oxygen therapy prior to admission, nursing home residence. The imputation of missing oxygen flow values was conditional on the provision of supplemental oxygen (online supplemental appendix A). Fifty imputed datasets were created with a total run length of 50 000 iterations, with imputations performed every 1000 iterations. Second, we conducted an additional analysis using any readmission instead of unplanned readmission as part of the primary composite and secondary study outcomes.

Two-sided p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata Special Edition version V.16.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Results

Of the 1523 potentially eligible patients, 485 were excluded, resulting in a final sample of 1038 consecutive patients with CAP who were alive at discharge from the index hospitalisation (online supplemental appendix B).

Baseline patient characteristics

The median age of all patients was 77 years (IQR, 63–86), and 587 were men (56.6%) (online supplemental appendix C). On admission, 398 patients (38.3%) were classified as having PSI risk classes I–III, 447 (43.1%) as class IV and 193 (18.6%) as class V. The median length of hospital stay was 8 days (IQR, 4–13 days).

At discharge, median values for most vital signs were within the normal range, including temperature (36.9°C, IQR, 36.6–37.2), heart rate (83 beats/min, IQR, 73–94), systolic blood pressure (122 mm Hg, IQR, 110–138), diastolic blood pressure (69 mm Hg, IQR, 60–77) and oxygen saturation rate (95%, IQR, 93–96) (online supplemental appendix D). The exceptions were the respiratory rate (23 breaths/min; IQR, 19–28) and partial pressure of arterial oxygen (68 mm Hg; IQR, 61–77), although documented in <3% and 18% of patients, respectively. The prevalence of altered mental status and inability to maintain oral intake at discharge was 6.4% and 5.4%, respectively.

Postdischarge adverse events

During the 30-day follow-up period, 140 patients (13.5%) experienced postdischarge adverse events, including 108 unplanned readmissions (10.4%) and 32 deaths (3.1%) (online supplemental appendix B). The median time to postdischarge adverse event was 10 days (IQR, 5.5–21), ranging from 9 days (IQR, 7–17.5) for 32 deaths to 10.5 days (IQR, 5–21) for 108 unplanned readmissions. The main reasons for unplanned readmissions are summarised in online supplemental appendix E.

Sixteen additional patients died while readmitted to the hospital, contributing to an estimated overall 30-day mortality rate of 4.6% (48/1038). The total number of readmissions was 184 (17.7%), 76 (7.3 %) of which were elective (planned) readmissions. In addition, 20 emergency department visits did not result in hospital readmission.

Agreement across definitions of clinical instability

The percentage of patients who were unstable at discharge ranged from 12.8% (Capelastegui et al 2008)12 to 41.0% (Capelastegui et al 2009)13 (table 1). Overall, the five sets of criteria classified 515 patients (49.6%) as stable and 72 patients (6.9%) as unstable at discharge while there was disagreement on clinical instability for 451 patients (43.4%) (Fleiss Kappa coefficient, 0.47, 95% CI 0.44 to 0.50). The Fleiss Kappa was conservative, with alternative chance-corrected agreement coefficient estimates ranging 0.47–0.65 (online supplemental appendix F). The definitions of clinical instability according to Capelastegui et al (2008)12 and Capelastegui et al (2009)13 demonstrated fair agreement with the other definitions in the leave-one-out analysis (table 2).

Table 1. Prevalence of clinical instability at discharge among survivors of hospitalisations for community-acquired pneumonia (n=1038).

| Author, year* | Number (%) |

| Halm et al, 200215 | 320 (30.8) |

| Dagan et al, 200614 | 334 (32.2) |

| Jasti et al, 200816 | 220 (21.2) |

| Capelastegui et al, 200812 | 133 (12.8) |

| Capelastegui et al 200913 | 426 (41.0) |

Missing values for the instability criteria at discharge were imputed as zero (Ssee Methods section).

Table 2. Overall and leave-one-out Fleiss Kappa coefficient estimates (95% CI) for definitions of clinical instability at discharge among survivors of hospitalisations for community-acquired pneumonia (n=1038).

| Removed definition of clinical instability* | ||

| Halm et al 200215 | 0.39 | (0.35–0.42) |

| Dagan et al 200614 | 0.38 | (0.35–0.42) |

| Jasti et al 200816 | 0.42 | (0.39–0.46) |

| Capelastegui et al 200812 | 0.58 | (0.54–0.61) |

| Capelastegui et al 200913 | 0.55 | (0.52–0.59) |

| Overall | 0.47 | (0.44–0.50) |

Missing values for the instability criteria at discharge were imputed as zero (Ssee Methods section).

Associations with postdischarge adverse events

Clinical instability at discharge was associated with higher ORs for adverse events, unplanned readmissions and mortality for all but one definitions (online supplemental appendix G). The only exception was the definition by Capelastegui et al (2009),13 which showed lower OR point estimates and did not reach statistical significance for any study outcome.

After multiple imputations of missing values, clinical instability was no longer significantly associated with 30-day mortality using one definition and with adverse events and unplanned readmission using three definitions, compared with the primary analysis (online supplemental appendix H). These apparent inconsistencies likely reflect the fact that multiple imputations yielded inflated SEs, resulting in wider and less precise 95% CI.

Comparative accuracy

Discriminatory accuracy in predicting post-discharge adverse events did not differ across the five definitions of clinical instability, with c-statistic ranging 0.54–0.59 (p=0.31, figure 2). After multiple imputation of missing values, discriminatory accuracy was comparable, with c-statistic point estimates ranging 0.58–0.62 (table 3). Clinical instability showed modest sensitivity (ranging 0.19–0.47) and specificity (ranging 0.60–0.88), when using prespecified thresholds (table 4).

Figure 2. Discriminatory accuracy (c-statistic) for published definitions of clinical instability in predicting 30-day post-discharge adverse events among survivors of hospitalisations for community-acquired pneumonia (n=1038).

Table 3. c-statistic (95% CI) for published definitions of clinical instability in predicting 30-day post-discharge adverse events among survivors of hospitalisations for community-acquired pneumonia (n=1038).

| Author, year | Unplanned readmission or mortality | Any readmission or mortality* | ||||

| Primary analysis* | Secondary analysis† | |||||

| Halm et al, 200215 | 0.59 | (0.54–0.63) | 0.62 | (0.53–0.71) | 0.55 | (0.51–0.59) |

| Dagan et al, 200614 | 0.59 | (0.54–0.63) | 0.60 | (0.51–0.69) | 0.55 | (0.51–0.59) |

| Jasti et al, 200816 | 0.56 | (0.52–0.60) | 0.58 | (0.47–0.69) | 0.54 | (0.50–0.57) |

| Capelastegui et al, 200812 | 0.55 | (0.51–0.60) | 0.59 | (0.50–0.67) | 0.52 | (0.48–0.56) |

| Capelastegui et al, 200913 | 0.54 | (0.50–0.59) | 0.59 | (0.49–0.68) | 0.53 | (0.49–0.56) |

Missing values for the instability criteria at discharge were imputed as zero (Ssee Methods section).

Missing values for the instability criteria at discharge were imputed by multivariate imputation using chain equations (Ssee Methods section).

Table 4. Discriminatory accuracy point estimates (95% CI) using prespecified thresholds for published definitions of clinical instability in predicting 30-day post-discharge adverse events among survivors of hospitalisations for community-acquired pneumonia (n=1038).

| Author, year | Number of patients* | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | LR+ | LR− | |||

| True positive | False negative | False positive | True negative | |||||||

| Halm et al, 200215 | ||||||||||

| ≥1 | 63 | 77 | 257 | 641 | 0.45(0.37–0.54) | 0.71(0.68–0.74) | 0.20(0.15–0.24) | 0.89(0.87–0.91) | 1.57(1.27–1.94) | 0.77(0.66–0.90) |

| Dagan et al, 200614 | ||||||||||

| ≥1 | 65 | 75 | 269 | 629 | 0.46(0.38–0.55) | 0.70(0.67–0.73) | 0.19(0.15–0.24) | 0.89(0.87–0.91) | 1.55(1.26–1.90) | 0.77(0.65–0.90) |

| Jasti et al, 200816 | ||||||||||

| ≥1 | 44 | 96 | 176 | 722 | 0.31(0.24–0.40) | 0.80(0.78–0.83) | 0.20(0.15–0.26) | 0.88(0.86–0.90) | 1.60(1.21–2.12) | 0.85(0.76–0.96) |

| Capelastegui et al., 200812† | ||||||||||

| ≥2 | 27 | 113 | 106 | 792 | 0.19(0.13–0.27) | 0.88(0.86– 0.90) | 0.20(0.14–0.28) | 0.87(0.85–0.90) | 1.63(1.11–2.40) | 0.92(0.84–1.00) |

| Capelastegui et al, 200913 | ||||||||||

| ≥1 | 66 | 74 | 360 | 538 | 0.47(0.39–0.56) | 0.60(0.57–0.63) | 0.15(0.12–0.19) | 0.88(0.85–0.90) | 1.18(0.97–1.43) | 0.88(0.75–1.04) |

Missing values for the instability criteria at discharge were imputed as zero (Ssee Methods section).

Clinical instability was defined by a score ≥2 based on one major criterion (temperature>37.5°C, 2 points) and three minor criteria (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure <60 mm Hg, respiratory rate >24 breaths/min, and oxygen saturation <90% and/or PaO2 <60 mm Hg, 1 point each).

LR−likelihood ratio of negative resultLR+likelihood ratio of positive resultNPVnegative predictive valuePPVpositive predictive value

Additional analysis

Patients with planned readmissions were more likely to have active cancer than those with unplanned readmissions (40.8% (31/76) vs 15.7% (17/108), p<0.001). The most common reasons for planned readmission were chemotherapy or radiotherapy (31.6% (24/76)), medical follow-up for a chronic condition (19.7% (15/76)) and planned surgery (17.1% (13/76)).

Compared with the primary analysis using unplanned readmission as the study outcome, weaker associations were observed between clinical instability and any readmission, either alone or in combination with mortality (online supplemental appendix I). However, the discriminatory accuracy of clinical instability at discharge in predicting a composite of any readmission or mortality remained relatively unchanged, with c-statistic estimates ranging 0.52–0.55 (table 3).

Discussion

This external validation study provides additional evidence for the prognostic significance of clinical instability at discharge for patients with CAP. All but one of the published definitions of clinical instability were associated with a composite of 30-day mortality and unplanned readmission, supporting their transportability across populations and settings. As anticipated, the clinical instability criteria yielded moderate discriminatory accuracy in predicting postdischarge adverse events, reflecting the influence of numerous other factors on hospital readmission.

Compared with previous studies, the patients included in our study were older (mean age, 72 years) and more likely to be assigned to PSI risk classes IV–V (61.7%) and to experience postdischarge adverse events (20.6%) (online supplemental appendix J). Clinical instability criteria derived in one country or population may not provide accurate predictions elsewhere, a phenomenon called miscalibration.19 With the exception of Capelastegui et al13, all definitions of clinical instability at discharge demonstrated external validity when applied to older patients with more severe pneumonia recruited from the French healthcare system, even 10–20 years after their original derivation. The moderate agreement observed between the definitions of clinical instability arises from inconsistent thresholds for dichotomised continuous predictors, variations in scoring systems and the omission of important predictors.

Capelastegui et al13 definition, which classified a higher percentage of patients as clinically unstable at discharge (41.0%), showed fair agreement with other definitions and did not demonstrate significant associations with postdischarge adverse events. These findings reflect an inconsistent threshold for defining elevated body temperature (≥37.2°C), with a prevalence as high as 30% in our study. Although selecting the optimal cut-off maximises statistical significance in primary studies, dichotomising continuous predictors may introduce bias and hinder replication in external validation samples.20 A previous study found that patients with CAP discharged while still febrile had comparable outcomes to those who were stable at discharge, suggesting that fever may be less concerning than other instabilities.33

The scoring system published by Capelastegui et al12 defines clinical instability as a score ≥2 in contrast to other definitions that rely on any instability present at discharge. This scoring system classified a lower percentage of patients as clinically unstable at discharge (12.8%) and achieved higher specificity (0.88, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.90) at the cost of lower sensitivity (0.19, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.27) in predicting postdischarge adverse events.

Compared with definitions of clinical instability that only consider vital signs,16 the addition of mental status and the ability to maintain oral intake criteria14 15 convey stronger associations with postdischarge adverse events. Our findings support the current guidelines,10 34 which advocate monitoring vital signs (such as heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation and temperature), ability to eat and mental status to guide discharge decisions and duration of antibiotic therapy in patients with CAP.

There is no evidence that prolonging the hospital stay of clinically unstable patients leads to clinical stabilisation and reduces the incidence of postdischarge adverse events.11 Despite a 30.8% prevalence of clinical instability at discharge, the absolute risk difference in postdischarge adverse events was relatively modest (9.0 percentage points). In contrast, prolonging hospital stay may expose patients to unnecessary risks of hospital-acquired infections and venous thromboembolism.

Our study found stronger associations between clinical instability and 30-day mortality postdischarge compared with previous studies. This finding may be attributed to the higher proportion of patients with PSI risk classes IV and V in the study population (online supplemental appendix J). The severity of pneumonia on admission affects the time taken to achieve clinical stability and predicts short-term mortality, with more severe pneumonia requiring a longer recovery time and conferring a worse prognosis.35

All five definitions of clinical instability were binary, using meaningful thresholds that are easily remembered by physicians and nurses. Dichotomising clinical prediction scores may lead to a loss of information and reduce discriminatory accuracy. Moreover, dichotomisation assumes a constant risk for all values beyond the threshold. However, the discriminatory accuracy of the discrete score or number of instabilities remained poor in predicting postdischarge adverse events, with c-statistic point estimates <0.60 for all five definitions.

This finding reflects the relatively low magnitude of ORs despite the significant associations.36 A variety of factors other than premature discharge from the index hospital are associated with readmissions, including demographic information, socioeconomic status, prior use of health services, diagnosis codes, laboratory results and discharge disposition.37 In comparison, the median c-statistic for 11 published claims-based or electronic medical record models predicting the risk of 30-day readmission for CAP patients was 0.63 (range, 0.59–0.77), despite combining up to 30 predictors.38

Updating the existing definitions of clinical instability may range from simple recalibration to more extensive revisions.20 Improving calibration requires adjusting the original model regression intercept to ensure that the mean predicted probability aligns with the observed outcome frequency for the intended population. Improving discriminatory accuracy requires model revision, including re-estimating individual regression coefficients and incorporating new predictors. As the updated definitions are adjusted to the validation sample, they should be assessed for internal and external validity before use in routine medical practice.20

Our study has several strengths. First, we performed a head-to-head comparison of definitions of clinical instability using the same study sample to eliminate population heterogeneity across primary studies.20 This heterogeneity, not discernible from primary study results, may lead to variations in performance attributes across different definitions of clinical instability. Therefore, indirect comparisons cannot determine which definition is most effective in identifying patients at risk of postdischarge adverse events. In contrast, the prevalence and accuracy estimates of clinical instability were derived from the same individual participant dataset and directly compared as part of the present external validation study.20

Second, we used unplanned readmission as the study outcome measure, which is more representative of substandard care than any readmission.39,41 Third, our study produced more precise estimates and was more powered to detect clinically relevant associations than published primary studies because of the larger sample size. This may explain why some previous studies14 15 failed to show significant associations between clinical instability at discharge and readmission, despite comparable OR point estimates.

Our study has some limitations. First, missing values for vital signs were imputed at zero in the primary analysis, a strategy previously validated for pneumonia severity clinical prediction models.23 24 42 Apart from the observed proportions of missing values for respiratory rate that posed a challenge for imputation techniques, the distribution of recorded values suggested that some vital parameters were more likely to be recorded in case of abnormal findings.25 This selective recording questions the plausibility of the missing at random assumption and the validity of multiple imputations of missing values.25 43 Nevertheless, the OR and c-statistic point estimates were comparable for both approaches to handling missing values.

Second, our study only tracked readmissions at two participating hospitals, with no access to the National Health Data System to track other readmission. Therefore, the incidence of unplanned readmissions may be underestimated. However, the 30-day readmission rate in our study was higher than those reported in previous studies (online supplemental appendix J).

Third, the implementation of the clinical instability criteria in practice may have influenced the 30-day postdischarge outcomes. However, the low level of documentation of the respiratory rate at discharge suggests that clinical instability criteria were not routinely used to assess patient readiness for discharge.

Fourth, the case definition of pneumonia varied between the primary studies, although most included evidence of new or recent pulmonary infiltrates on chest radiographs. Consequently, we cannot exclude the possibility that our study did not capture the full spectrum of CAP.

Fifth, this study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in healthcare services and patient behaviour during and after the pandemic may have altered discharge dispositions and readmission patterns.2 However, it is unlikely that the pandemic weakened the relationship between clinical instability at discharge and adverse events.

Conclusion

Clinical instability at discharge is associated with higher odds of 30-day postdischarge adverse events according to all but one published definition. Our study supports the validity of definitions that combine vital signs, mental status and the ability to maintain oral intake to assess the safety of discharge in patients hospitalised with CAP. However, further research is needed to determine the benefits of prolonging the hospital stay in clinically unstable patients.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was supported by the Direction générale de l’offre de soins, Ministère de la Santé, Paris, France (Programme de recherche sur la performance du système des soins [PREPS-IQ] 2013, grant number: PREPS1300302).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: An institutional review board (Comité de Protection des Personnes [CPP] Sud-Est V, Grenoble, France; 15 July 2014; no approval number) reviewed and approved the study protocol and informed consent form before the study began. The study database was approved by the Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l’Information en matière de Recherche dans le domaine de la Santé (CCTIRS, Paris, France; approval number 14.586bis) and authorised by the French Data Agency (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés [CNIL], Paris, France; authorisation number DR-2015-161). In accordance with French regulations, data were collected after adequate written information was provided, unless the patient objected.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Anne Danjou, Email: ADanjou@chu-grenoble.fr.

Magali Bouisse, Email: MBouisse@chu-grenoble.fr.

Bastien Boussat, Email: BBoussat@chu-grenoble.fr.

Sophie Blaise, Email: SBlaise@chu-grenoble-alpes.fr.

Jacques Gaillat, Email: jgaillat@ch-annecygenevois.fr.

Patrice Francois, Email: pfrancois@chu-grenoble.fr.

Xavier Courtois, Email: xcourtois@ch-annecygenevois.fr.

Elodie Sellier, Email: ESellier@chu-grenoble.fr.

Anne-Claire Toffart, Email: AToffart@chu-grenoble.fr.

Carole Schwebel, Email: CSchwebel@chu-grenoble.fr.

Ethan A Halm, Email: ethan.halm@rutgers.edu.

José Labarere, Email: JLabarere@chu-grenoble.fr.

Data availability statement

The de-identified database analysed in this study is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Peters ZJ, Ashman JJ, Schwartzman A, et al. National Hospital Care Survey Demonstration Projects: Examination of Inpatient Hospitalization and Risk of Mortality Among Patients Diagnosed With Pneumonia. Natl Health Stat Report. 2022;2022:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lawrence H, McKeever TM, Lim WS, et al. Readmission following hospital admission for community-acquired pneumonia in England. Thorax. 2023;78:1254–61. doi: 10.1136/thorax-2022-219925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prescott HC, Sjoding MW, Iwashyna TJ. Diagnoses of early and late readmissions after hospitalization for pneumonia. A systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:1091–100. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201404-142OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cram P, Wachter RM, Landon BE. Readmission Reduction as a Hospital Quality Measure: Time to Move on to More Pressing Concerns? JAMA. 2022;328:1589–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.18305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kristensen SR, Bech M, Quentin W. A roadmap for comparing readmission policies with application to Denmark, England, Germany and the United States. Health Policy. 2015;119:264–73. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and Causes of Readmissions in a National Cohort of General Medicine Patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:484–93. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boussat B, Cazzorla F, Le Marechal M, et al. Incidence of Avoidable 30-Day Readmissions Following Hospitalization for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in France. JAMA Netw Open . 2022;5:e226574. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.6574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aliberti S, Dela Cruz CS, Amati F, et al. Community-acquired pneumonia. Lancet. 2021;398:906–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00630-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.File TM, Ramirez JA. Community-Acquired Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:632–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2303286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200:e45–67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen OK, Makam AN, Clark C, et al. Vital Signs Are Still Vital: Instability on Discharge and the Risk of Post-Discharge Adverse Outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32:42–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3826-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Capelastegui A, España PP, Bilbao A, et al. Pneumonia: criteria for patient instability on hospital discharge. Chest. 2008;134:595–600. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-3039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capelastegui A, España Yandiola PP, Quintana JM, et al. Predictors of short-term rehospitalization following discharge of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2009;136:1079–85. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dagan E, Novack V, Porath A. Adverse outcomes in patients with community acquired pneumonia discharged with clinical instability from Internal Medicine Department. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:860–6. doi: 10.1080/00365540600684397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halm EA, Fine MJ, Kapoor WN, et al. Instability on hospital discharge and the risk of adverse outcomes in patients with pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1278–84. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jasti H, Mortensen EM, Obrosky DS, et al. Causes and risk factors for rehospitalization of patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:550–6. doi: 10.1086/526526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adamuz J, Viasus D, Campreciós-Rodríguez P, et al. A prospective cohort study of healthcare visits and rehospitalizations after discharge of patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Respirology. 2011;16:1119–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aliberti S, Zanaboni AM, Wiemken T, et al. Criteria for clinical stability in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:742–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00100812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collins GS, Moons KGM. Comparing risk prediction models. BMJ. 2012;344:bmj.e3186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labarère J, Renaud B, Fine MJ. How to derive and validate clinical prediction models for use in intensive care medicine. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:513–27. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mounayar A-L, Francois P, Pavese P, et al. Development of a risk prediction model of potentially avoidable readmission for patients hospitalised with community-acquired pneumonia: study protocol and population. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e040573. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyer L, Fond G, Gauci M-O, et al. Regulation of medical research in France: Striking the balance between requirements and complexity. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2023;71:S0398-7620(23)00711-3. doi: 10.1016/j.respe.2023.102126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:243–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aujesky D, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. Prospective comparison of three validated prediction rules for prognosis in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med. 2005;118:384–92. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rijk MH, Platteel TN, Mulder MMM, et al. Incomplete and possibly selective recording of signs, symptoms, and measurements in free text fields of primary care electronic health records of adults with lower respiratory tract infections. J Clin Epidemiol. 2024;166:S0895-4356(23)00336-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.111240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ashton CM, Wray NP. A conceptual framework for the study of early readmission as an indicator of quality of care. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43:1533–41. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wadhera RK, Yeh RW, Joynt Maddox KE. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program - Time for a Reboot. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2289–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1901225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halfon P, Eggli Y, van Melle G, et al. Measuring potentially avoidable hospital readmissions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:573–87. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00521-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fleiss JL. Measuring nominal scale agreement among many raters. Psychol Bull. 1971;76:378–82. doi: 10.1037/h0031619. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Landis JR, Koch GG. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vanacore A, Pellegrino MS. Robustness of κ‐type coefficients for clinical agreement. Stat Med. 2022;41:1986–2004. doi: 10.1002/sim.9341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hougham GW, Ham SA, Ruhnke GW, et al. Sequence patterns in the resolution of clinical instabilities in community-acquired pneumonia and association with outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:563–71. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2626-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lim WS, Baudouin SV, George RC, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax. 2009;64 Suppl 3:iii1–55. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.121434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halm EA, Fine MJ, Marrie TJ, et al. Time to clinical stability in patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: implications for practice guidelines. JAMA. 1998;279:1452–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, et al. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:882–90. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koch JJ, Beeler PE, Marak MC, et al. An overview of reviews and synthesis across 440 studies examines the importance of hospital readmission predictors across various patient populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2024;167:S0895-4356(23)00343-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.111245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weinreich M, Nguyen OK, Wang D, et al. Predicting the Risk of Readmission in Pneumonia. A Syst Rev Model Perform Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:1607–14. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201602-135SR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benbassat J, Taragin M. Hospital readmissions as a measure of quality of health care: advantages and limitations. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1074–81. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.8.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Horwitz LI. Planned, Related or Preventable: Defining Readmissions to Capture Quality of Care. J Hosp Med. 2017;12:863–4. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van Walraven C, Forster AJ. When projecting required effectiveness of interventions for hospital readmission reduction, the percentage that is potentially avoidable must be considered. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66:688–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aujesky D, Stone RA, Obrosky DS, et al. Using randomized controlled trial data, the agreement between retrospectively and prospectively collected data comprising the pneumonia severity index was substantial. J Clin Epidemiol. 2005;58:357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van Walraven C, McCudden C, Austin PC. Imputing missing laboratory results may return erroneous values because they are not missing at random. J Clin Epidemiol. 2023;154:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2022.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified database analysed in this study is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.