Abstract

Background

Currently, the popularity of female genital cosmetic procedures is on the rise worldwide. Despite the multiple roles of healthcare practitioners at different stages of women’s decision-making for these procedures, limited studies have been conducted in this area. This systematic review aimed to summarize the available qualitative and quantitative data from observational studies that investigated healthcare practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding female genital cosmetic procedures.

Method

The present systematic review was performed based on PRISMA guidelines. All published studies that examined the knowledge, attitudes and practices of healthcare practitioners regarding female genital cosmetic procedures were included. PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Web-of-science, ScienceDirect and Google Scholar were searched using related keywords until 30 November 2023. Quality assessment was performed using the Appraisal Tool for Cross-Sectional Studies and Checklist for Qualitative Research from the Joanna Briggs Institute.

Results

Eight studies comprising 2063 healthcare practitioners met the inclusion criteria and were analysed. Based on the results, some healthcare practitioners in the included studies acknowledged the naturalness of the variety of female genitalia, but others considered very small labia as attractive. There was little agreement on the positive effects of female genital cosmetic procedures on improving women’s quality of life and sexual function in the included studies. Nearly all healthcare practitioners have seen women who had concerns about being natural of their genitalia. Meanwhile, approximately two-thirds of them had encountered women requesting female genital cosmetic procedures. Only three-quarters of healthcare practitioners felt confident in assessing the normality of genital appearance. The willingness to perform female genital cosmetic procedures was higher among male healthcare practitioners and plastic surgeons than among females and gynecologists.

Conclusion

The results indicated that although a large number of healthcare practitioners had encountered women who were concerned about genitalia or requested genital cosmetic procedures, they did not have sufficient knowledge or favorable attitudes and practices in most related fields. Therefore, it is recommended to design educational interventions, formulate guidelines and make policies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12905-024-03439-8.

Keywords: Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, Health Practitioner, Female Genital Cosmetic procedures

Background

Female genital cosmetic procedures (FGCPs) refer to any nonmedically indicated cosmetic genital procedure that is designed to improve the appearance of female external genitalia [1–3]. Specifically, it encompasses a range of techniques, including labiaplasty, labia majora augmentation, pubic liposuction, clitoral hood reductions and laser procedures [4]. It has been suggested that FGCPs are associated with improved sexual performance [2, 5].

Currently, the popularity of FGCPs is on the rise worldwide [2, 5]. Evidence shows a 140% increase in these procedures in Australia between 2001 and 2013 [6]. The global rate of labiaplasty also increased by 28% between 2015 and 2018 and 24% between 2018 and 2019 [7]. The statistics published in the United States in 2018 also report 12,756 cases of labiaplasty, which has increased by 53% compared to the last 5 years, and according to the opinion of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, it can no longer be considered a passing trend [8]. A similar increase was reported in some countries of Eastern Europe, North and Central America and Asia from 2001 to 2016 [9]. This is even though the reported amount did not reflect the actual number of these techniques because a large number of them are offered in private clinics and centers [10].

It has been discussed that these procedures have risks that can include infection, scarring, disfigurement, pain during intercourse and changes in sexual sensation [11, 12]. For example, the removal of labia minora or clitoral hoods is associated with disorder in the sexual response cycle due to their role during sexual arousal and orgasm. In addition, despite these procedures being promoted as effective treatment options, scant evidence of clinical effectiveness, complications, safety and long-term consequences exists [13, 14].

It has been suggested that genital modification for cosmetic reasons has many sociocultural roots [2, 15]. Decisions about changing genital appearance may also be based on false assumptions about natural dimensions [11]. There is an increasing number of girls and women who perceive their labia minora as annoying and unsightly. They want a vulva with labia minora that is so short as to be invisible [11, 16]. They attribute sexual, physical, or aesthetic reasons to the size of the labia minora and therefore request labia minora reduction or other cosmetic procedures [16, 17]. However, according to the literature, women who undergo FGCPs are more likely to have psychiatric disorders than women who do not choose these procedures [18].

On the other hand, many similarities between female genital mutilation (FGM) and FGCPs have been proposed, which indicates the increasing medicalization of female genital cutting [19]. However, although FGM is considered a form of violence against women and is often denounced by international organizations, FGCPs are not condemned by the United Nations agencies and WHO. According to the literature, support for FGCPs may influence efforts to curb FGM. This is because the medicalization of these procedures seems to create the false confidence that if HCPs perform the technique, fewer adverse outcomes may occur and fewer objections are raised against it [20]. Furthermore, the rise of FGCPs in high-income countries has allowed traditional practices to be medicalized and passed off as cosmetics [21].

In recent years, general practitioners (GPs), gynecologists, plastic surgeons and other healthcare practitioners (HCPs) have increasingly encountered women who are concerned about their genitalia appearance and sometimes request genital cosmetic techniques [16].

On the one hand, HCPs also play an important role in promoting women’s knowledge about their genitals. As the first point of contact with the health care system, knowledgeable GPs often play an important role in informing women and girls about genital diversity and the risks of genital cosmetic procedures [22]. In this regard, women in the US and Australia considered their physicians as one of the sources of learning about the appearance of the vulva [23, 24].

In addition to GPs, gynecologists are often the primary providers of women’s health services that provide guidance and counsel on their health and well-being [25]. In this regard, ACOG (2020) urges obstetricians and gynecologists to be prepared to discuss natural sexual development and the wide diversity of genital appearance, nonsurgical options, and autonomous decision-making [3].

On the other hand, at the same time that the public tends to use these procedures under the influence of the media, it is unlikely that physicians will not be affected. Physicians’ personal opinions about genital appearance and their willingness to perform surgery may influence their clinical decision-making [16]. In 2007, members of the ACOG expressed concern about the increasing number of physicians providing cosmetic surgery for women without medical indications and the lack of evidence regarding the safety and effectiveness of these techniques [12].

However, despite the multiple roles of HCPs regarding this emerging phenomenon, limited studies have been conducted in the field of their knowledge, attitudes and practices in different disciplines [2, 4, 16, 26, 27]. For example, in a cross-sectional study by Simonis et al. (2016), almost all Australian GPs were asked by women about the naturalness of their genitals. However, only three-quarters of them were confident in their ability to assess female genital anatomy. More than half of them had seen women who were requesting for FGCPs. However, one-third of them evaluated their knowledge of FGCPs as insufficient [2].

Based on the points mentioned above, this systematic review aimed to summarize the available qualitative and quantitative data from observational studies that investigated healthcare practitioners’ knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding female genital cosmetic procedures.

Method

This manuscript was written according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [28].

Search strategy

Online electronic databases such as PubMed/Medline, Scopus, Web-of-science, ScienceDirect and Google Scholar were individually searched using the terms “Female genital cosmetic” OR “Cosmetic genital” OR “Female genital cosmetic procedure” OR “female genital cosmetic surgery” OR “female genital cosmetic practice” OR “labiaplasty” AND “health practitioner” OR “health provider” OR “general practitioner” OR “physician” OR “Gynecologist” OR “plastic surgeon”. A combination of search strategies involving Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and keywords were used depending on the search methods of each database. There was no restriction on the publication date and language for the included studies. References of included studies were manually reviewed to search for possible missing articles.

Inclusion criteria

Articles were eligible if published before 30 November 2023, were only in English, were published in peer-reviewed journals, and reported original research (using qualitative or quantitative methods) about the knowledge, attitude, practice and role of HCPs in FGCPs. Case reports, conference reports, review articles, meta-analysis and expert opinions were excluded.

Study selection

After removing duplicates, two researchers screened the titles and abstracts of records according to the PRISMA guidelines. To determine final inclusion, the full text of all potential studies was independently read and reviewed by two researchers. During the review of the studies, disagreements were resolved through further discussion.

Data extraction

Two reviewers independently extracted data from the included studies using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. The data extraction sheet included the first author’s name, year of publication, study country, study design, mean age, sample size, specialty of HCPs, gender proportion of HCPs, the main evaluated variable and its measurement tool and quality score of studies.

Quality assessment of the study

Quality assessment of cross-sectional studies was conducted by the Appraisal tool for Cross-Sectional Studies (Axis tool). It is a valid quality appraisal tool to evaluate the quality of cross-sectional studies using 20 criteria. The results of the quality assessment were calculated using no = 0, yes = 1 and cannot tell or do not know = 0 for each question [29]. A scoring method was adapted to quantify the risk of bias in the studies based on this scale. According to this method, studies were categorized as very low risk of bias if they obtained a score of 19 out of 20, as low risk of bias if they scored 17 or 18, as a moderate risk of bias if they obtained 15 or 16, and as high risk of bias if scored 14 or less [30].

The quality of the Harding and Kirkman studies, with a qualitative approach, was assessed by using the Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI, 2014). It is a 10-question tool that was used [31]. So far, the classification for assessing the risk of bias of the qualitative study has not been provided based on this tool, and a higher score indicates a better quality of the studies. For both tools, the scores of all questions were summed to provide a score for each study, which was presented in the results. Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the included studies. In this study, no studies were excluded based on quality scores.

Results

Study selection and characteristics

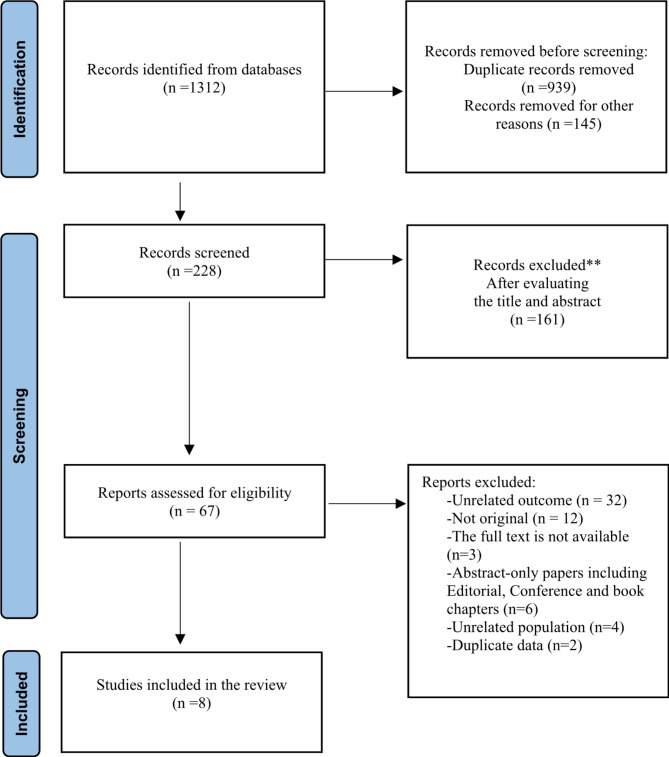

A total of 1312 potential records were identified from the online electronic databases PubMed/Medline (n = 25), Google Scholar (n = 1120), Scopus (n = 12), Web of Science (n = 36) and ScienceDirect (n = 119).

After removing duplicate studies and excluding ineligible studies, a total of eight studies were included in the final systematic review. Figure 1 shows the study selection process and reasons for excluding records during full-text screening.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases

Quality assessment

The results of the quality assessment of the cross-sectional studies using the Axis tool showed that the quality scores of the included articles ranged from 12 to 16. This means that three quantitative studies had a high risk of bias [16, 26, 32] and three studies had a moderate risk of bias [1, 2, 27]. The quality of the included qualitative articles was at an average level with a score of 6 out of 10 based on the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Authors [Year] |

Study Country | Study Design | Evaluated Variable | Number of Participants |

Mean age of participants or Age range |

Health practitioner Specialty | Gender proportion [male/female] |

Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reitsma (2011) [16] |

Netherlands | Cross-sectional |

Attitudes, experiences, and performance of labioplasty |

164 | 44.5 |

GP = 80, Gynecologist = 41, Plastic Surgeon = 43 |

[96/48] | [14/20] * |

|

Lowenstein (2014) [26] |

Different countries | Cross-sectional study |

Attitudes toward indications for FGPS. |

360 |

48 [23–72] |

Gynecologist = 36, Urologists = 187, Family physicians = 47, Psychiatrists and other specialties [e.g., cardiologists, endocrinologists] = 36 |

[226/94] | [12/20] * |

|

Harding (2015) [4] |

Australia | Qualitative study | Viewpoints | 27 | 28–66 |

GPs, Gynecologists and Plastic Surgeons Nurses, 2ee, Sexual Health Physician and Policymaker |

[7/20] | [6/10] ** |

|

Simonis (2016) [2] |

Australia | Cross-sectional study |

Knowledge, attitudes and practice regarding female genital cosmetic surgery |

443 | 52.9 | General Practitioner | [116/327] | [15/20] * |

|

Yeğin (2021) [27] |

Turkey | Cross-sectional study |

Attitudes towards Female Genital Cosmetic Procedures |

623 | NR |

Medical students = 120, Professional: Obstetrics and gynecology = 183, General practitioners = 101, other surgical = 117, other non-surgical = 102 |

[265/358] | [15/20] * |

|

Iqbal (2021) [32] |

Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional |

Opinion and ethical consideration of FGCPs |

260 | NR |

Consultant gynecology = 20, Medical students = 117, Postgraduate trainee gynecology = 35, Postgraduate trainee surgery = 30, MBBS Graduates = 48, Other specialties = 10 |

[53/207] | [13/20] |

|

Sawan (2022) [1] |

Saudi Arabia | Cross-sectional |

Attitudes toward female genital cosmetic surgeries |

165 | 24–60 |

Obstetrics and gynecology = 136, Plastic, and reconstructive surgery = 29 |

[48/117] | [16/20] * |

|

Kirkman (2024) [33] |

Australia | Qualitative study | Identifying discourses that explained or justified FGCPs | 21 | 32–76 | Health professionals = 16 (gynaecologists = 4, plastic surgeons = 4, cosmetic surgeons = 3, GPs = 1, nurses = 3, pelvic floor physiotherapists = 1) and non-health professionals = 4(beauty therapists = 4, body piercers = 1) | NR | [7/10] ** |

NR: Non-Reported

*AXIS

**JBI

Characteristics of the included studies

The included studies were published between 2015 and 2021. These eight studies enrolled a total of 2063 participants, with an age range between 24 and 76 years.

Of the 8 studies, 3 studies were conducted in Australia, 2 were in the Netherlands, 1 was in Turkey and 2 were in Saudi Arabia. More details can be found in Table 1.

Main Results

Reasons women seek FGCPs from the perspective of healthcare practitioners

The results of the two Australian studies showed that all GPs thought the demand for FGCPs in women was more affected by fashion, comfort in clothes, perception of beauty and pornography [2, 4]. In addition, some Australian HCPs stated that because the female genitalia are hidden by clothing, many women are unaware of the diversity of natural genitalia, which can increase the desire for these procedures [4].

The results of Kirkman’s study showed that psychological, functional and aesthetic reasons were the main reasons for the desire to use FGCPs from the perspective of HCPs. Physical discomfort (For example, during exercise or sexual activities) and poor hygiene were introduced as functional problems. Poor self-esteem and poor mental health were suggested as psychological causes. The results of this study also showed that the popularity of genital waxing, pornography, media representation, social pressure that originates in public discourse and personal opinions, regulations about representations of women’s genitals in Australian media, and women’s genital unfamiliarity were raised as reasons for women seeking to modify their genitals from the perspective of Australian HCPs [33].

Almost half of the HCPs (52%) from the study of Lowenstein believe that body image is the main reason for women to seek labiaplasty [26]. Improvement of sexual performance and reduction of genital pain were other reasons proposed by HCPs for performing labiaplasty [26].

HCPs’ perspective on diversity and the normal vulva

A review of studies showed that Australian HCPs in the study of Harding believed that there are many variations in the natural genitalia [4]. Similarly, all Australian HCPs in in Kirkman’s study stated that the appearance of the natural vulva was diverse [31]. However, despite acknowledging the diversity in the genitalia, they used words such as “excess”, " abnormal” and “unnecessary” to describe minor labia protrusion, indicating that in their view “natural” actually refers to the vulva without visible labia minora [33].

Furthermore, 90% of all physicians from different specialties in a cross-sectional study in the Netherlands believed that external genitalia with very small labia minora represents society’s ideal and considered it attractive [16]. The participants stated that their view of the natural shape of the genitals is based only on experience. This suggests that in the absence of codified education, a healthcare provider faced with a limited number of female patients is likely to be less confident in assuring women that different genitalia variants are natural [16].

Experience with women concerned about their genital anatomy and women requesting FGCPs

The results of Simonis and Harding from Australia revealed that nearly all HCPs (97% and 100%, respectively) had seen women who were concerned about their genitalia [2, 4]. However, only 75% of the HCPs in one of these two studies had examined the genitalia of women requesting FGCPs [2]. In addition, only three-quarters of Australian HCPs felt confident in assessing the natural appearance of the genitals [2]. All participants stated their need for resources to inform women of natural genital appearance [4]. The point mentioned by some participants is that women who have concerns about their genital appearance may refuse to see their HCPs for necessary examinations such as a pap smear because they fear being judged by them and seen as malformed [2].

Furthermore, some Australian GPs had experiences relief of concerns after reassuring women that their genital anatomy was natural [2, 4]. Despite the number of women with concerns about their genitalia, only approximately two-thirds of the Australian HCPs in these two studies had been asked about cosmetic procedures or requested a referral for one [2, 4].

However, the results of Lowenstein showed that two-thirds (65%) of physicians from various disciplines related to sexual medicine from different countries have repeatedly or occasionally encountered women requesting FGCPs [26].

Health providers’ perspectives on the effects of FGCPs

Just over half (54–55%) of the Turkish HCPs believed that FGCPs improve the quality of life, self-esteem, and sexual functions of women. In this study, one-fourth of the participants considered that the effect of FGCPs was a temporary trend, while almost one-third of them thought the opposite [27].

Similarly, almost one-third (30%) of HCPs in the study of Lowenstein believed that FGCPs improve sexual function in women. In this study, conversely, other participants either did not.

know whether or not believe that FGCPs affect sexual function [26].

In the qualitative study conducted by Kirkman, HCPs had different views on whether the FGCPs improve psychological problems. Some Australian HCPs claimed that FGCPs could improve women’s self-confidence, however others disagreed. Further, some other Australian HCPs were concerned that FGCS could reduce sexual pleasure or cause pain and discomfort [33].

Ethical perspectives and women’s rights about FGCPs from the viewpoint of HCPs

Almost two-thirds of the Turkish HCPs (74–78%) considered that it could be appropriate to perform FGCPs based solely on a patient’s desire without therapeutic necessity [27], whereas only one-fifth of Australian GPs (21%) in the study of Simonis thought so [2]. However, most Saudi HCPs would refuse requests for clitoral hood reduction because they deem these practices to be unethical [32].

6. Condemnation of performing FGCPs in girls under 18 years old

More than a third of Australian GPs (35%) and all Saudi physicians stated that they had seen women under 18 years of age who requested FGCPs [1, 2]. More than half of Australian GPs (56%) in a study conducted in Australia believed that FGCPs should not be performed on women younger than 18 years unless medically indicated [2]. In the study conducted by Yegin, more than four-fifths of Turkish HCPs (80.1%) supported not performing FGCPs in girls under 18 years of age [27].

Psychological assessment before performing FGCPs

More than half of Australian GPs (50–67%) suspected mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and body dysmorphic disorder in female referrals applying for FGCPs [2]. In addition, approximately half of the Australian GPs in this study (56%) and Turkish HCPs in another study (44.8%) felt that a woman should be supported with psychological counselling before proceeding to FGCPs and that mental health screening should be performed for all referees [2, 27]. Most HCPs in the study of Lowenstein (75%) also stated that they refer their patients to a psychologist or a psychiatrist for a comprehensive assessment [26]. Several HCPs in the study of Kirkman stated that a woman’s anxiety and emotions should be managed through a referral to a psychologist or psychiatrist before cosmetic surgery. Others did not refer patients for psychological help and performed psychological assessments themselves [33].

The need to improve knowledge to optimize better performance in counseling or clinical practice

The GP is an educator on the anatomy of the reproductive system and FGCPs [2]. However, two-thirds of Australian GPs (75%) rated their knowledge about FGCPs as insufficient [2]. In addition, of those who encountered patients requesting FGCPs, nearly half (44%) did not know enough about the risks of FGCPs. Regardless of the lack of sufficient knowledge, only 75% of Australian GPs in this study felt confident in assessing the naturalness of genital anatomy. The majority of the GPs in this study needed more information to support their patients [2].

Similarly, the majority of Australian HCPs in the study of Harding also highlighted their need for greater education to raise awareness of FGCPs. Although the Australian HCPs in this study acknowledged that they saw patients requesting FGCPs, some of them stated that they did not know how to manage these consultations best [4].

More than half of Saudi HCPs and medical students (68.7%) in the Iqbal et al. study stated that they did not have sufficient knowledge about the FGCPs [29]. Later, in another study, only half of Saudi physicians (46–53%) knew about the long- and short-term risks of FGCPs and always discussed these with their patients [1].

HCPs’ views on the advertisement of FGCPs

Approximately half of Turkish HCPs thought that the encouragement and advertisement of FGCPs should be forbidden [27].

The effect of gender on the attitudes and performance of HCPs

HCPs’ beliefs about female genital beauty and FGCPs differ by gender, with men being more willing to undertake surgery than women [16, 26]. In this regard, the survey performed by Reitsma in the Netherlands revealed that male physicians from different specialties were more inclined to perform a labia minora reduction procedure than their female counterparts [16].

In another study of physicians from several countries, 14% of specialists sometimes or frequently performed labial reduction surgery, which was higher among male than female physicians [2].

A study that investigated the ethical concerns of Turkish medical students and professionals regarding FGCPs showed that the gender of the participants did not affect their ethical views and opinion on the medical indications of FGCPs, except that male Turkish HCPs consider vulvar bleaching (genital whitening) to be unethical [27].

The effect of specialty on the attitude and performance of HCPs

The results of the study of Harding, Reitsma and Yeğin indicated the difference in the attitudes and practices of HCPs in different disciplines regarding FGCPs [4, 16, 27]. The results of Reitsma’s study showed that GPs and gynecologists had different attitudes about what forms a natural and attractive vulva compared to plastic surgeons [16]. In this study, more plastic surgeons considered the picture with the largest labia minora as unnatural and undesirable compared to GPs and gynecologists, and more were likely to offer cosmetic surgery to women. Furthermore, plastic surgeons had a significantly higher tendency to perform labiaplasty than gynecologists regardless of the size of the labia minora and the presence or absence of physical discomfort [16].

Similarly, in the qualitative study performed by Harding, some participants expressed that gynecologists were more likely to reassure women about the natural state of their genitalia than plastic surgeons. In addition, they were less willing to undertake labia minora reduction surgery [4]. Furthermore, in a cohort study of Yegin in Turkey, nearly half of the respondents thought that women should be screened by a psychiatrist before undergoing procedures. However, there was a high disagreement among specialists in different fields, with more than half of gynecologists, fewer than 10% of GPs and approximately 15% of surgeons concurring on this point [27]. Most Saudi HCPs and medical students agreed that FGCPs should be Performed by gynecologists rather than general surgeons and plastic surgeons [32].

Discussion

This is the first known comprehensive report to systematically review studies that explored the knowledge, attitudes and practices of HCPs regarding FGCPs. The findings of this study listed the reasons such as fashion, comfort in clothes, perception of beauty and pornography for seeking FGCPs by women from the perspective of HCPs [2, 4]. Many of these reasons are consistent with those on websites promoting these methods, such as comfort in clothing, increased self-esteem, and improved sexual satisfaction [2, 4, 26, 27, 34]. This is despite the relationship between the appearance of female genitalia and its modification with FGCPs for some of the mentioned reasons having no scientific basis [35]. In this regard, numerous studies indicate the inefficiency of FGCPs in improving the quality of sexual function [36, 37].

In fact, consistent with many other studies, and contrary to the reasons women give health providers for performing FGCPs, such as frequent infections or discomfort during exercise, there are deep emotional issues due to anxiety about appearing natural, sexual anxiety or embarrassment behind their request [38–40]. The results of some studies have confirmed this, where it was mentioned that the Australian GPs in the Simonis study considered mental health problems such as depression in women requesting FGCPs [2].

Furthermore, the findings of the included studies indicated differences in the views of HCPs about natural genital appearance [4, 16]. For example, according to Reitsma’s study, HCPs’ understanding of natural genitalia is only based on their experiences in examining their client, so it is recommended to provide training to them during their educational courses and then provide educational materials during service delivery [16]. It is also important to note that one of the critical roles of HCPs is to inform women about the variety of genitalia appearances. Therefore, they must be sure of the naturalness of different variants of female genitalia [19].

Other findings resulting from this review showed that almost all HCPs had clients who expressed concern about their genital appearance [2, 4]. More than half of the HCPs had encountered women requesting FGCPs, which is evidence of the increasing popularity of these procedures [26]. However, despite the high prevalence of encountering these patients, HCPs in several studies felt a lack of knowledge to reassure women about the naturalness of the genitalia and counseling about FGCPs [2, 4]. This also shows the need for clinical resources to help them in this area [4]. In this regard, some resources, such as the labia library provided by Women’s Health Victoria, can be introduced to women to provide a realistic understanding of the natural female genitalia. The Labia Library is a website that shows a variety of variants of the natural anatomy of the female genitalia [41].

Based on the included studies, GPs play a primary role in informing about genital anatomy and FGCPs, performing initial mental health screening, and referring women appropriately if necessary [19, 42]. According to some studies, some other medical professions, such as midwives or nurse-midwives, are also the first line of contact with women, which solves the concerns of women about the appearance of genitals or sexual issues [43–45]. Midwives and nurses involved in cervical cancer screening, sexual counselling, and treatment of gynecologic disease have many opportunities to help women and girls explore their concerns about genital appearance, provide reassurance and counsel or refer [46]. They have more time than any other HCPs to talk to women and girls about their reproductive and sexual concerns, give them the necessary advice and training, and participate in their informed decisions [47]. Therefore, HCPs providing FGCPs services should have extensive knowledge of female pelvic and reproductive anatomy and should work as a team based on current evidence and independent of commercial interests [48].

Along with the HCPs who stated that they have little confidence in reassuring women, some HCPs in Harding’s study were able to adequately reassure women about genital naturalness. Immediate reassurance to women about the natural state of the genitalia and no immediate referral to a specialist may resolve women’s fears and concerns and lead to a reduction in the request to use the FGCPs [4, 11].

The other results show that some HCPs do not know about the short-term and long-term complications of FGCPs [1, 2]. However, the limited evidence about the long-term and short-term positive effects of genital modification and the risks associated with it should be presented to patients [3]. Furthermore, women requesting surgery should be informed that FGCPs are extreme interventions and may not necessarily solve their concerns [35].

On the other hand, more than half of HCPs from Turkey believed that FGCPs improve quality of life, self-esteem, and sexual performance [27]. However, in the study of Lowenstein et al., in which HCPs from different countries participated, only one-third of the participants agreed on this matter. The results of Lowenstein’s study are consistent with the scientific evidence that indicates the lack of effectiveness of FGCPs in improving the quality of sexual function [26, 35].

In line with the recommendations of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the British Association of Paediatrics and Adolescent Gynecology, more than half of HCPs in the included studies believed that FGCPs should not be performed in women under 18 years of age [2]. In this regard, the statistics of studies conducted in Australia, the United Kingdom and the US show that the incidence of FGCPs in the age group of 15–25 years is similar to that of the age group of 26–45 years. In addition, this statistic is increasing, similar to other age groups [2, 49, 50]. The external genitalia change during puberty and there is a need to refrain from intervention until the woman reaches full maturity [45]. In this regard, a recent Internet-based survey reported a high complication rate (20.5%) of labiaplasty in adolescents, with a rate requiring reoperation in 6.8% of cases. Nearly half of the study subjects reported a change in labia size after the procedure [51].

Regarding the ethical perspective governing HCPs, there was no agreement in the view of HCPs in different studies about performing FGCPs without medical indication. Turkish FGCPs were more willing to perform FGCPs only at the patient’s request compared with Australian GPs [2, 26]. In addition, approximately half of Turkish HCPs thought that the encouragement and advertisement of FGCPs should be forbidden [27]. As is evident, along with the expansion of medical commercialization and marketing of health services, some providers of FGCPs do not provide real information in their advertisements [34]. As such, advertisements should be accurate and not lead to misleading and deceiving applicants [3].

The results of this review also indicated differences in the opinion and practice of male and female HCPs in the context of FGCPs, which may be due to differences between the two genders in attitudes towards female genital appearance and the more erotic view of men [4, 16, 26, 27]. On the other hand, based on the results, plastic surgeons have a more unfavorable attitude towards larger labia minora than gynecologists, and they mostly offer FGCPs. Disagreement in opinion and practice among experts in the field of FGCPs may be due to the different nature of their expertise. Plastic surgeons often deal with many parts of the body. However, gynecologists, regardless of FGCPs, may have more experience looking at variations of female genitalia and may be more aware of the variation in female genitalia. Evidence suggests that surgeons have historically played a role in defining “normal” and “abnormal” anatomy, and that their actions help define and limit the “normal” genitalia for women. The fact that the HCPs who are responsible for defining or redefining the natural genitalia for women are those who profit from the lucrative market of these techniques is an inherent conflict of interest [52]. Therefore, based on the findings of this review, HCPs, especially plastic surgeons, should ensure that providing real and much-needed services to humans, not business, is the real goal of the medical profession [53]. In addition, it is recommended to emphasize especially to male physicians and plastic surgeons, who are more inclined to perform FGCP, during training courses that their judgments and perceptions should not influence the performance of FGCP and other similar fields.

According to the exponential growth of FGCPs and according to the findings of the present study, there is a need to pay more attention to improving the knowledge and practice of HCPs in accordance with international guidelines in order to reduce the growth of these procedures. Additionally, as part of appropriate practices, the natural range of female genitalia should be defined and presented to HCPs, women and the community. Training interventions with lasting psychological and functional benefits to health personnel to provide to women requesting FGCPs should be considered.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to investigate the knowledge, attitudes, and practices of HCPs regarding FGCPs. The present study has some limitations that should be considered. One of these limitations is the possible publication bias because we only included English-language articles. One of these limitations is possible publication bias because we only included English-language articles, which would have omitted other relevant studies. Second, there was a moderate to high risk of bias for quantitative studies which may limit the value of our findings. In addition, the included studies are limited to a number of countries, which limits the generalization of the results to other countries, especially to developing and underdeveloped countries that have an increasing slope similar to developed countries in terms of FGCPs. Due to the heterogeneity of the data, especially the use of different and nonstandard tools, and different outcomes, it was not possible to perform a meta-analysis.

Further research on the knowledge, attitudes and roles of HCPs is recommended, especially in underdeveloped or developing countries. In addition, considering that in many countries, other medical professions, such as midwives, are at the forefront of primary health services for women, exploring the knowledge, attitude and roles of these HCPs about FGCPs is recommended.

Conclusion

Female genital cosmetic procedures are influenced by complex social interactions that can be promoted or limited by the health practitioner’s opinion and practice. This review illustrated some reasons for women’s tendency towards FGCPs from the perspective of HCPs. The naturalness of female genital diversity was acknowledged by most HCPs, however, others considered the external genitalia with very small labia attractive and used pathological language to describe natural genitalia. There was little agreement about the positive effects of FGCPs on improving women’s quality of life and sexual performance among HCPs. HCPs had encountered women who were concerned about the naturalness of their genitalia, but some were not confident in reassuring women about their appearance. Therefore, they realized the need for resources to know the natural genital appearance. Furthermore, the willingness to perform FGCP was higher among male HCPs than female surgeons and plastic surgeons compared to gynecologists. Given that HCPs are faced with cultural norms that push women for change their bodies, it is clear that despite training during education, sustained and continuous training should be provided to them regarding the principles of medical ethics during service delivery. Further research in other cultural contexts will lead to more complete evidence on the views and practices of health practitioners regarding Female genital cosmetic procedures.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

No.

Abbreviations

- FGCPs

Female Genital Cosmetic Procedures

- HCPs

Healthcare Practitioners

- US

United States

- GPs

General Practitioners

Author contributions

EA, SEZ and NJS were responsible for the conception, search literature and performed the data selection and quality assessment. EA, NJS, EH interpreted the data. EA, SEZ and ET drafted the manuscript, and NJS and EH substantially revised the manuscript. All authors worked on revisions and read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding has been received for this paper.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sawan D, Al-Marghoub M, Abduljabar GH Jr., Al-Marghoub M, Kashgari F, Aldardeir N, et al. The attitude of Physicians towards Female Genital Cosmetic surgery. Cureus. 2022;14(8):e27902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Simonis M, Manocha R, Ong JJ. Female genital cosmetic surgery: a cross-sectional survey exploring knowledge, attitude and practice of general practitioners. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e013010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elective Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery. ACOG Committee Opinion Summary, Number 795. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;135(1):249–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding T, Hayes J, Simonis M, Temple-Smith M. Female genital cosmetic surgery: investigating the role of the general practitioner. Aus Fam Physician. 2015;44(11):822–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw D, Allen L, Chan C, Kives S, Popadiuk C, Robertson D, et al. Guideline 423: Female Genital Cosmetic surgery and procedures. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2022;44(2):204–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Services AGDoH. Medicare Item Reports. [http://medicarestatistics.humanservices.gov.au/statistics/mbs_item.jsp]

- 7.The Aesthetic Society. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery National Databank Statistics. 2019: The Aesthetic Society; 2019. [https://cdn.theaestheticsociety.org/media/statistics/2019-TheAestheticSocietyStatistics.pdf]

- 8.Aesthetic Plastic Surgery National Databank Statistics 2020: The Aesthetic Society. 2020. [https://cdn.theaestheticsociety.org/media/statistics/aestheticplasticsurgerynationaldatabank-2020stats.pdf] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Liao L-M, Creighton SM. Female Genital Cosmetic surgery: solution in pursuit of Problem. In: Liao L-M, Creighton SM, editors. Female Genital Cosmetic surgery: solution to what Problem? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2019. pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe J, Black KI. Female genital cosmetic surgery. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;61(3):325–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liao LM, Creighton SM. Requests for cosmetic genitoplasty: how should healthcare providers respond? BMJ [Clinical research ed]. 2007;334(7603):1090–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.ACOG Committee Opinion No. Vaginal rejuvenation and cosmetic vaginal procedures. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;378(3):737–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berman JR, Berman LA, Werbin TJ, Goldstein I. Female sexual dysfunction: anatomy, physiology, evaluation and treatment options. Curr Opin Urol. 1999;9(6):563–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minto CL, Liao LM, Woodhouse CR, Ransley PG, Creighton SM. The effect of clitoral surgery on sexual outcome in individuals who have intersex conditions with ambiguous genitalia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet (London England). 2003;361(9365):1252–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharp G, Tiggemann M, Mattiske J. Predictors of consideration of Labiaplasty: an extension of the tripartite influence model of Beauty ideals. Psychol Women Q. 2014;39(2):182–93. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reitsma W, Mourits MJ, Koning M, Pascal A, van der Lei B. No (wo)man is an island–the influence of physicians’ personal predisposition to labia minora appearance on their clinical decision making: a cross-sectional survey. J Sex Med. 2011;8(8):2377–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodman MP. Female cosmetic genital surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veale D, Eshkevari E, Ellison N, Costa A, Robinson D, Kavouni A, Cardozo L. Psychological characteristics and motivation of women seeking labiaplasty. Psychol Med. 2014;44(3):555–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahvisi A. FGM vs. female cosmetic surgeries: why do they continue to be treated separately? Int J Impot Res. 2023;35(3):187–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esho T. The future of genital cutting: an evolution of its medicalization. Afr Futures. 2022;27:338–46. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimani S, Shell-Duncan B. Medicalized female genital Mutilation/Cutting: contentious practices and Persistent debates. Curr Sex Heal Rep. 2018;10(1):25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liao LM, Creighton SM. Female genital cosmetic surgery: a new dilemma for GPs. The British journal of general practice. J Royal Coll Gen Practitioners. 2011;61(582):7–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howarth C, Hayes J, Simonis M, Temple-Smith M. Everything’s neatly tucked away’: young women’s views on desirable vulval anatomy. Cult Health Sex. 2016;18(12):1363–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yurteri-Kaplan LA, Antosh DD, Sokol AI, Park AJ, Gutman RE, Kingsberg SA, et al. Interest in cosmetic vulvar surgery and perception of vulvar appearance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(5):e4281–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pauls RN. We are the correct physicians to treat women requesting labiaplasty. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(3):218–e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowenstein L, Salonia A, Shechter A, Porst H, Burri A, Reisman Y. Physicians’ attitude toward female genital plastic surgery: a multinational survey. J Sex Med. 2014;11(1):33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeğin GF, Kılıç G. Clinical and ethical perspectives of medical professionals towards female genital cosmetic procedures. 2021;18(2):131–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Res ed). 2021;372:n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e011458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor M, Masood M, Mnatzaganian G. Longevity of complete dentures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Prosthet Dent. 2021;125(4):611–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lockwood C, Munn Z, Porritt K. Qualitative research synthesis: methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):179–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iqbal S, Akkour K, Bano B, Hussain G, Elhelow M, Al-Mutairi AM, et al. Awareness about Vulvovaginal aesthetics procedures among Medical Students and Health professionals in Saudi Arabia. Revista Brasileira De Ginecol E Obstetricia: Revista da Federacao Brasileira das Sociedades de Ginecol E Obstet. 2021;43(3):178–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkman M, Dobson A, McDonald K, Webster A, Wijaya P, Fisher J. Health professionals’ and beauty therapists’ perspectives on female genital cosmetic surgery: an interview study. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23(1):601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mowat H, McDonald K, Dobson AS, Fisher J, Kirkman M. The contribution of online content to the promotion and normalization of female genital cosmetic surgery: a systematic review of the literature. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shaw D, Allen L, Chan C, Kives S, Popadiuk C, Robertson D, et al. Guideline 423: Female Genital Cosmetic surgery and procedures. J Obstet Gynecol Can. 2022;44(2):204–e141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Emhardt E, Siegel J, Hoffman L. Anatomic variation and orgasm: could variations in anatomy explain differences in orgasmic success? Clin Anat [New York NY]. 2016;29(5):665–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krissi H, Ben-Shitrit G, Aviram A, Weintraub AY, From A, Wiznitzer A, et al. Anatomical diversity of the female external genitalia and its association to sexual function. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;196:44–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zwier S. What motivates her: motivations for considering Labial reduction surgery as recounted on women’s Online communities and surgeons’ websites. Sex Med. 2014;2(1):16–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berman L, Berman J, Miles M, Pollets D, Powell JA. Genital self-image as a component of sexual health: relationship between genital self-image, female sexual function, and quality of life measures. J Sex Marital Ther. 2003;29(Suppl 1):11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Michala L, Koliantzaki S, Antsaklis A. Protruding labia minora: abnormal or just uncool? J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;32(3):154–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Victoria WsH. Labia Library. Melbourne: Women’s Health Victoria; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Braun V. Female genital cosmetic surgery: a critical review of current knowledge and contemporary debates. J Women’s Health. 2010;19(7):1393–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Quinlivan J, Rowe H, Wischmann T, Thomson G, Stuijfzand S, Horsch A, et al. Setting the global research agenda in psychosocial aspects of women’s health - outcomes from ISPOG world conference at the Hague. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2020;41(1):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rowe H. Biopsychosocial obstetrics and gynaecology - a perspective from Australia. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;37(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Creighton SM, Liao LM. Female Genital Cosmetic surgery: solution to what Problem? Cambridge University Press; 2019.

- 46.Female genital cosmetic. surgery- A resource for general practitioners and other health professionals. Melbourne: The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Female Genital Cosmetic Surgery. Solution to what Problem? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vieira-Baptista P, Almeida G, Bogliatto F, Bohl TG, Burger M, Cohen-Sacher B, et al. International Society for the study of Vulvovaginal Disease recommendations regarding Female Cosmetic genital surgery. J Lower Genit Tract Dis. 2018;22(4):415–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cosmetic Surgery National Data Bank Statistics. Aesthet Surg J. 2018;38(suppl3):1–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aesthetic Genital Surgery. Female Genital Aesthetic Surgery (Aesthetic Genital Surgery DV. London.

- 51.Jodoin A, Dubuc E. Labia Minora surgery in the Adolescent Population: a cross-sectional satisfaction study. J Sex Med. 2021;18(3):623–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stahl D, Vercler CJ. What should be the Surgeon’s role in defining normal genital appearance? AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(4):384–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Atiyeh BS, Rubeiz MT, Hayek SN. Aesthetic/Cosmetic surgery and ethical challenges. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2008;32(6):829–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.