Abstract

Background

The Covid-19 pandemic led to a rapid increase in the use of virtual consultations across healthcare. Post-pandemic, this use is expected to continue alongside the resumption of traditional face-to-face clinics. At present, research exploring when to use different consultation formats for palliative care patients is limited.

Aim

To understand the benefits and limitations of a blended approach to outpatient palliative care services, to provide recommendations for future care.

Methods

A mixed-methods study. Component 1: an online survey of UK palliative care physicians. Component 2: a qualitative interview study exploring patients’ and caregivers’ experiences of different consultation formats. Findings from both components were integrated, and recommendations for clinical practice identified.

Results

We received 48 survey responses and conducted 8 qualitative interviews. Survey respondents reported that face-to-face consultations were appropriate/necessary for physical examinations (n = 48) and first consultations (n = 39). Video consultations were considered appropriate for monitoring stable symptoms (n = 37), and at the patient’s request (n = 42). Patients and caregivers felt face-to-face consultations aided communication. A blended approach increased flexibility and reduced travel burden.

Conclusions

A blended outpatient palliative care service was viewed positively by physicians, patients and caregivers. We identified 13 clinical practice recommendations for the use of different consultation formats.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12904-024-01578-1.

Keywords: Referral and consultation, Outpatients, Palliative care, Remote consultation

Background

The philosophy of palliative care was first conceptualised by Dame Cicely Saunders in the 1960’s. Since then, palliative care services have evolved dramatically, and now represent a multi-disciplinary professional specialty that cares for patients throughout the trajectory of their life-limiting illness and via a range of service delivery models, e.g. hospice inpatient units, outpatient palliative care clinics and acute hospital-based palliative care teams [1]. Outpatient clinics typically allow patients earlier access to palliative care services and are supported by evidence of improved patient outcomes [2]. Furthermore, outpatient clinics have the benefit of requiring relatively few resources and the ability to serve large patient populations [3] - something important when considering the increasing palliative care needs of an ageing population [4] and the scarcity of palliative care healthcare professionals. Historically, most palliative care outpatient services provided exclusively face-to-face consultations, however the use of virtual technology/ telemedicine has increased over time. The World Health Organisation defines telemedicine as “the delivery of healthcare services, where distance is a critical factor, by all healthcare professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information…. all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and communities” [5]. The most familiar use of telemedicine relates to the clinical consultation – patient and healthcare professional, each in a different location, use technologies such as telephone and videophone to communicate. Despite evidence of effectiveness, prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, there was limited international adoption of telehealth technologies, owing to a resistance to change and lack of staff and patient education [6]. A 2010 review across UK palliative care services found that telehealth technologies were being used effectively to some extent, but there remained “no evidence to suggest that telehealth [was] integrated into UK palliative care services in any systematic fashion” [7].

The outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic caused unprecedented disruption to hospital and community healthcare services. At-risk and vulnerable patients in particular suffered poorer symptom control, and social isolation increased the strain on caregivers [8]. New approaches to care delivery were urgently required, and a rapid increase in the use of telehealth technologies was seen [9–11].

Whilst it is recognised that telehealth consultations do not provide a complete substitute for face-to-face care [8, 12, 13], research exploring their feasibility and acceptability has found broadly positive results [10, 11, 14]. During the Covid-19 pandemic, the acceptance of telehealth consultations among patients continued to increase. Sutherland and colleagues reviewed 170 virtual palliative care consultations that occurred during the covid-19 pandemic and found 85% of patients felt video consultations gave a similar or better experience than face-to-face consultations, and 96% were open to future video appointments [13]. That said, face-to-face consultations are often still preferred [8, 15] and for palliative care patients there are particular worries about dehumanising the clinical consultation and the potential negative impact of virtual consultations on communication [12, 16, 17].

Post-pandemic, the use of virtual consultations is expected to continue alongside the resumption of traditional face-to-face clinics. For services to effectively combine these approaches, evidence-based guidance is needed. At present, research exploring how and when to use different approaches in palliative care is limited. To address this need we conducted the following mixed-methods study, the aim of which was to understand the benefits and limitations of a blended approach (mixing virtual and face-to-face consultations) to outpatient palliative care services, to provide recommendations for future practice.

Design and methods

We conducted a mixed-methods study with a concurrent triangulation design [18].

A blended approach to outpatient palliative care services can be considered a complex intervention. A mixed methods design was therefore chosen to allow a more comprehensive and holistic understanding of the phenomenon by enhancing the findings of each component (quantitative and qualitative) with the other. The study included two research components (outlined below), assigned equal weighting and conducted concurrently. The findings were then combined, interpreted and overall conclusions made.

Component 1 – online survey of palliative care physicians

Component 1 was an online survey of palliative care physicians. The survey instrument was a questionnaire developed and piloted by the research team (no existing validated questionnaire was identified for use), with content derived from of a literature review of the subject. The questionnaire explored the experiences and views of UK palliative care physicians regarding different outpatient consultation modalities (telephone; video; face-to-face; blended) and contained a mixture of open (free text boxes), closed and Likert-scale questions. It comprised three sections: (1) basic demographic data (age; sex; clinical role) as well as participants’ familiarity with conducting virtual consultations; (2) participants’ experiences of face-to-face and virtual consultations; and, (3) participants’ views on a blended approach to outpatient services, including identifying clinical scenarios that they believed were “appropriate/necessary” and “inappropriate/unnecessary” for different consultation formats. Free text boxes allowed participants to expand on the benefits and challenges they had experienced with each format of consultation (appendix 1 - questionnaire).

A link to the survey was distributed, via email, to members of the Association for Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland (APM). The APM is one of the world’s largest representative bodies of palliative care professionals and has a growing membership of over 1,300 [19]. Following discussion and approval by the APM Ethics, Science and Executive Committee, information about the study and a link to access the survey was sent to all APM members as part of their quarterly bulletin. NHS Research Ethics Committee approval was not required as participants were identified by virtue of their profession [20], and consent was implied by participants actively choosing to acknowledge, complete and submit the survey. Individuals were eligible to complete the survey if they were a UK palliative medicine physician with experience of face-to-face, telephone and/or video consultations. Allied healthcare professionals, and physicians who did not have experience of palliative care outpatient consultations, were excluded. The survey remained open for three months from 1st February 2022, with a reminder sent after six weeks.

All survey data was anonymised and stored securely. Quantitative data responses were analysed in Microsoft Excel using descriptive statistics; open questions and free-text answers were manually coded for trends and patterns.

Component 2 – qualitative study

Component 2 was a qualitative interview study exploring patients’ and caregivers’ experiences of different consultation formats, with data collected via in-depth semi-structured interviews.

Ethical approval for the study was received from the UK Research Ethics Committee (project ID 308342).

Study participants were adults (≥ 18 years), recruited from medical outpatient clinics at St Ann’s Hospice, Greater Manchester. St Ann’s Hospice is one of the UK’s oldest and largest hospices, operating across two sites in Greater Manchester. As well as two inpatient units, St Ann’s provides weekly medical outpatient clinics, a range of specialist services, e.g. counselling, lymphoedema care and complementary support [21]. Between 1st June 2022 and 31st August 2022 all patients attending medical outpatient clinics at St Ann’s Hospice, Heald Green, were screened against the study’s eligibility criteria (Table 1). Any patients identified as eligible for the study were first approached by a clinical member of the hospice who provided them with information about the study and assessed their interest in participating. Those who expressed an interest were then contacted by a member of the research team who provided further information, answered any questions, and if the patient was agreeable to participating, gained written consent and arranged an interview time. Caregivers were identified through patients enrolled to the study. To aid recruitment, interviews were conducted either individually or jointly with a caregiver, based on the patient’s preference.

Table 1.

Study eligibility criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

|

• English-speaking • Adults (≥ 18 years) • Able to operate and engage with an interview via Microsoft Teams |

• Individuals unable to provide informed consent • Individuals unable to communicate in English • Individuals unable to operate and/or engage with an interview via Microsoft Teams • Patients considered too unwell to participate as determined by themselves and/or their palliative care physician |

Each participant consented to a one-off semi-structured interview via Microsoft Teams (Version 1.5.00.17656) with researcher CM (palliative care physician, MBChB MRCP MSc). All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, with field notes made during and immediately after each interview. At interview, participants were asked about their experience of different formats of clinic appointment (face-to-face; telephone; video). Participants were encouraged to talk in-depth, with prompts used to elicit further information when required. To enhance the consistency and completeness of data collected, an interview guide was developed based on the literature review conducted and the questions contained in the component 1 online survey (appendix 2 – interview topic guide). Interviews continued until data saturation was achieved. Specifically, this was the point when the research team was confident that the emerging themes and constructs were fully represented by the data collected and additional interviews would not result in a greater depth of understanding or the generation of new themes and/or constructs [22].

Interviews were anonymised and transcribed verbatim. Detailed thematic content analysis based on Braun and Clarke [23] was conducted using NVivo 12 Plus software. Researcher CM started by reading all interview transcripts multiple times to ensure familiarity with the dataset. Each transcript was then open coded where meaningful words, phrases and statements were identified. An iterative process continued whereby initial themes were identified followed by more detailed coding until themes were fully developed, refined, defined and named [24]. Particular attention was paid to non-confirmatory and divergent cases. Analysis of the interview transcripts was discussed with researcher LH at regular intervals during the process, and all final themes reviewed and finalised by the entire research group.

Integration of components 1 and 2

Integration involved merging the findings from both components to allow one overall interpretation [25]. The qualitative findings expanded on the quantitative results and provided a greater depth of understanding.

Recommendations for clinical practice were then developed based on the integrated findings.

Results

Component 1 – online survey of palliative care physicians

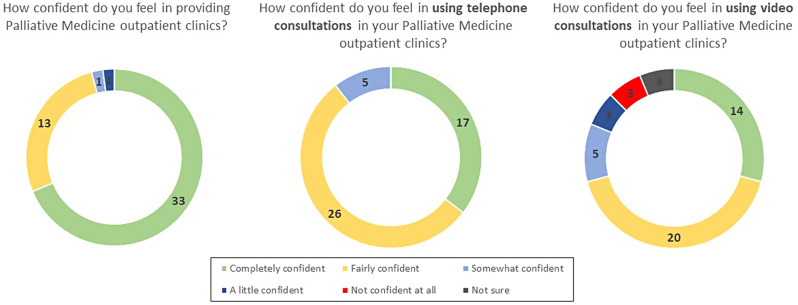

The online survey was completed by 48 physicians; 42 were female and 37 worked at consultant grade. The greater proportion of female respondents is representative of clinical palliative care in the UK that remains a female dominated specialty. Most physicians worked in hospital (n = 19) or hospice (n = 17) settings, and there were respondents from all regions of the UK (Table 2). Most respondents felt ‘completely’ (n = 33) or ‘fairly’ confident (n = 13) in providing palliative medicine outpatient clinics, including via telephone or video (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Demographics of survey respondents

| n = 48 | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 6 |

| Female | 42 |

| Clinical Role | |

| Consultant | 37 |

| Specialty Registrar | 6 |

| Specialty and Associate Specialist / Hospice Physician | 4 |

| Other | 1 |

| Age Range (Years) | |

| 31–40 | 13 |

| 41–50 | 19 |

| ≥ 51 | 16 |

| Clinic Setting | |

| Hospital | 19 |

| Hospice | 17 |

| Community | 9 |

| Other | 3 |

| UK Region of Work | |

| London | 2 |

| South East England (exc. London) | 6 |

| South West England | 1 |

| East England | 5 |

| East Midlands | 5 |

| West Midlands | 4 |

| North West England | 12 |

| North East England, Yorkshire and Humber | 6 |

| Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland | 7 |

Fig. 1.

Circle diagram of self-reported professional confidence in providing palliative medicine outpatient clinics using different modalities

All respondents reported that a face-to-face consultation was appropriate and/or necessary for a physical examination, and most stated that is was appropriate and/or necessary for a patient’s first consultation (n = 39), if requested by a patient (n = 43), when delivering bad news (n = 39), for unstable symptoms (n = 31) and if there was a clinical concern (n = 40). Less respondents felt a face-to-face consultation was appropriate and/or necessary for routine reviews (n = 4), medication reviews (n = 8) and for patients with stable symptoms (n = 3). Most respondents considered a telephone consultation appropriate and/or necessary for reviewing stable symptoms (n = 44), conducting routine clinical reviews (n = 42), at the patient’s request (n = 38), for a medication review (n = 32) and for carer support (n = 24). Video consultations were considered appropriate and/or necessary by the majority of respondents for monitoring stable symptoms (n = 37), at the patient’s request (n = 42) and for routine and medication reviews (n = 36 and n = 32 respectively) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Respondent survey responses (n = 48)

| Clinical situation | Number of respondents who think a face-to-face consultation is appropriate and/or necessary | Number of respondents who think a telephone consultation is appropriate and/or necessary | Number of respondents who think a video consultation is appropriate and/or necessary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Request | 43 | 38 | 42 |

| First Consultation | 39 | 5 | 20 |

| Routine Review | 4 | 42 | 36 |

| Physical Examination Required | 48 | 1 | 7 |

| Medication Review | 8 | 32 | 32 |

| Stable Symptoms | 3 | 44 | 37 |

| Unstable Symptoms | 31 | 11 | 21 |

| Clinician Concern | 40 | 8 | 17 |

| Delivering Bad News | 39 | 5 | 15 |

| Carer Support | 25 | 24 | 22 |

Free text comments from respondents highlighted the importance of individualised care. The choice of consultation format was described as being a balance of patients’ preference and clinicians’ knowledge of what format would be required to ensure an appropriate assessment is conducted.

Need to decide on an individual patient basis – no ‘never’ and ‘always’ in individualised patient care. (physician, survey free text comment)

I think this is about knowing your patient. I think if you have developed a good rapport then I would be comfortable breaking bad news and carer support [virtually], as you know how to effectively communicate. (physician, survey free text comment)

Professionals rarely considered face-to-face consultations inappropriate with the most cited reasons that they improve communication and allow for clinical examination. Respondents recognised that face-to-face consultations presented challenges for patients including travel burden and the impact from Covid-19 restrictions.

When commenting on the use of telephone consultations, professionals reported that they provide an easy, accessible and efficient tool for clinical contacts, but raised concerns about the limited clinical assessment they allowed and identified that telephone consultations could be considered less significant to patients. Video consultations were considered a good alternative to telephone consultations as they allowed for more assessment and interaction. Physicians main concerns related to video consultation technology.

47 of the 48 respondents felt there was benefit to blending outpatient clinic modalities. The most cited benefit was flexibility, and the decision was felt best made jointly between clinician and patient based on clinical need and the consultation objectives.

This is the ideal – using the right type of consultation for the right patient at the right time in their illness for the right purpose. (physician, survey free text comment)

I have long been an advocate of a blended approach and long before Covid would do an initial face-to-face consultation and follow up with telephone consults… [where] appropriate. Our feedback… is that this approach is well liked by our patients. (physician, survey free text comment)

Component 2 – qualitative study

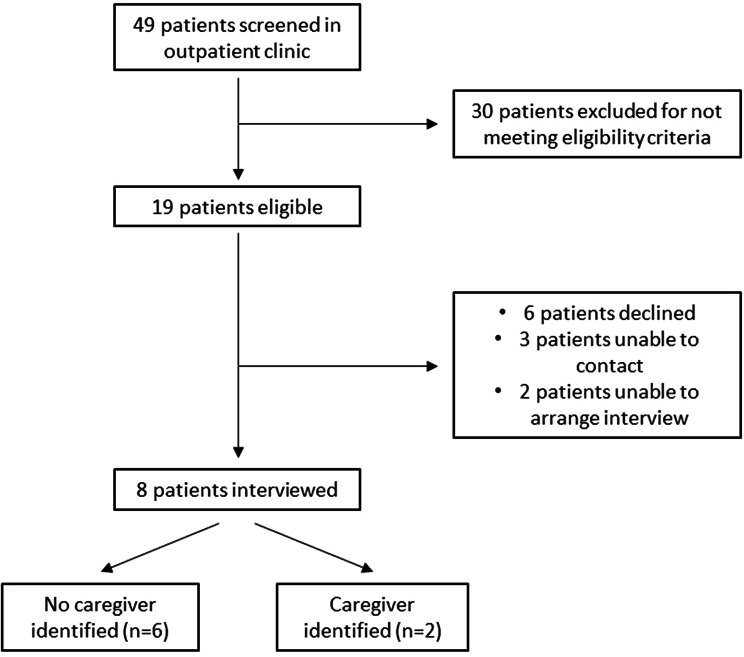

Forty-nine patients were screened for the study, of whom 19 met the eligibility criteria and were approached regarding participation. Six patients declined to participate and five were either not available when contacted or unable to agree an interview time, resulting in eight patients being recruited to the study. Among the eight patients recruited, two identified caregivers who were also approached and recruited to the study (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Flow diagram of patient and caregiver recruitment

Patient participants ranged from 40 to 79 years (median 62 years), five were male. All participants completed the study with interviews lasting an average of 45 min (range 37 to 55 min).

We identified eight themes relating to different consultation types and two related to a blended approach (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of themes from qualitative interviews

| Face-to-face consultations |

|

1. The opportunity for clinical examination 2. Improved communication 3. Time and physical burden |

| Telephone consultations |

|

1. Convenience and ease of use 2. Impaired communication |

| Video consultations |

|

1. Improved communication compared to telephone consultations 2. Convenience 3. Challenges of technology |

| A blended approach to outpatient services |

|

1. Greater flexibility 2. Introduce different approaches early in disease trajectory |

Themes for face-to-face consultations

Three themes emerged regarding face-to-face consultations. Themes seen as beneficial were: (1) the opportunity for clinical examination, and; (2) improved communication. Patients described being reassured by having a physical examination and also reported that they felt examination was important for the clinician as part of their overall assessment.

If it’s something you visually show somebody, then I’d rather be face-to-face obviously. I’d be thinking over the phone, you’re not seeing exactly how I’m trying to cope here with it. (patient P5-0, qualitative interview)

Face-to-face consultations improved both verbal and non-verbal communication. Participants also acknowledged how enhanced communication led to greater satisfaction with the overall consultation and was important for complex and/or challenging discussions.

If I’m seeing somebody and speaking, I tend to be able to concentrate more… And [retain] the information, [because] I’ve actually spoken to somebody face-to-face. (patient P5-0, qualitative interview)

The final theme that emerged described the challenge of face-to-face appointments which was the physical burden and time required for an in-person appointment. This could feel overwhelming for some and not worth the effort if the appointment was deemed to be routine or conducted very quickly.

So the biggest is the all-day nature of a physical consultation. You get ten, fifteen, twenty minutes with the doctor, but it takes up all day. You’ve got to get there, patient transport, and it shouldn’t be tiring sat in a waiting room but for whatever reason it is SO draining. (patient P6-0, qualitative interview)

Yes, I think it’s the value you get out of the time that’s spent. [Going to Local Hospital] from here, you’re talking probably 4 h of your time. And if that is just routine… Although it was a pleasant conversation, when you added it all up…. (caregiver P1-1, qualitative interview)

Themes for telephone consultations

Patients considered telephone consultations to be of value when a specific and straightforward issue needed addressing or as a triage tool. They recognised the convenience and ease of receiving a phone call (theme 1 as per Table 4) but highlighted important limitations. The second theme that emerged was the negative impact of telephone consultations on communication. Participants described how the visual loss created a ‘distance’ to the consultation that reduced clarity and reassurance. They also found the lack of physical assessment worrying and this negatively impacted the patient’s perception of the quality of the assessment.

You can’t see the person. You can’t read their body language. You feel a bit like a forgotten man, really, with the telephone conversation, it’s just feels…. I don’t think they’re particularly beneficial. (patient P6-0, qualitative interview)

Themes for video consultations

For video consultations, two positive themes and one challenging theme were identified. These were (1) Improved communication, especially compared to telephone consultations; (2) Convenience, and; (3) Technology challenges. Participants described feeling comfortable communicating via video as a direct result of the Covid-19 pandemic when this mode of communication became normalised. Communication via video was particularly good when participants had previously had face-to-face contact with the clinician. When a professional relationship was already established some participants felt that receiving bad news would also be acceptable via video, whilst for others a face-to-face appointment would be preferred.

The ability to articulate yourself over Zoom or whatever is quite easy… it seems pretty [natural way to talk]. It has become more part of our everyday life because of the pandemic… I had met [Hospice Consultant], I think we got on quite well. And therefore that was very easy to do subsequent [consultations] by video. (patient P7-0, qualitative interview)

I’d rather have [bad news] face-to-face… I’d walk away, I’d shut the phone down… Because you just wanna shut it away. You don’t want to hear that like that. I’d rather 110% get any bad news face-to-face. (patient P5-0, qualitative interview)

Challenges with video consultations related to practical issues with technology - but were not felt to be insurmountable, and the convenience of video appointments made up for any concerns regarding this.

Themes for a blended approach to outpatient services

A blended approach to outpatient services was considered beneficial by all participants who acknowledged the flexibility and greater convenience this provided (theme 1 as per Table 4). The option to change their appointment format based on how they were feeling was key to patients feeling that a blended service improved their comfort and overall care experience.

I suppose it would be good to have a fall-back position that you can change it if it’s…. So you might say [six weeks before], yes I’m happy to have a telephone conversation. But actually when it comes to it, face-to-face would be better… It would be nice to be able to alter your original decision. (patient P3-0, qualitative interview)

I think each one at different times, I would think ‘I just want to ring them up and ask them this’ or having a video one, and then think ‘oh right I really could do with seeing you every now and again’ as well. So yeah, benefits of having all three. (patient P2-0, qualitative interview)

When discussing blended approaches, the importance of introducing different formats and technology early in the patient’s journey emerged as the second key theme. Having experience of video consultations earlier in their illness meant that if a patient felt too unwell to attend in person they were familiar with the alternative format and not overwhelmed by this change. By comparison having only had face-to-face appointments could lead to distress if the patient felt too unwell to attend with a change to a virtual clinic inadvertently heightening anxiety for patients unfamiliar with their use.

Discussion

This mixed-methods study explored the benefits and limitations of a blended approach (mixing virtual and face-to-face consultations) to outpatient services for palliative care patients, to provide recommendations for future models of care. We found confirmatory findings from our quantitative and qualitative data for the appropriateness of a face-to-face consultation when there is a clinical concern or physical examination is required, and the use of telephone consultations for medication checks and review of stable symptoms. Physicians and patients both reported that communication via video was superior to telephone, but for certain situations remained inferior to an in-person consultation. The use of a blended approach to outpatient palliative care services was seen as positive by patients and physicians, allowing the value of in-person consultations to be balanced against the burden of attending appointments.

Consultation approach and communication

Our findings are in keeping with the wider literature exploring virtual consultations in palliative care. Prior studies have identified the importance of face-to-face consultations to establish and maintain a clinical relationship [26, 27], as well as to allow for a physical examination [26, 28]. In their qualitative study of telemedicine video visits for patients receiving palliative care, Tasneem and colleagues found that although participants did not feel that the overall relationship between themselves and their palliative care provider changed as a result of video consultations, they did feel a need to have occasional in-person visits to establish a stronger rapport with their physician and enable physical examinations [26]. Likewise, in their proof-of-concept study of elderly palliative care patients, Read and colleagues reported that participants felt in-person visits were better than web-based video consults in part due to concerns about their ability to accurately relay physical signs and information [28].

We found that patients and physicians reported telephone consultations to be practically convenient and suitable for routine reviews, in keeping with a 2016 systematic review of telephone consultations for cancer patients [29]. Our findings add the description of telephone consultations as a ‘triage’ service. This was seen positively by patients wanting immediate contact, but negatively by those for whom a second consultation was considered to be duplication. Previous studies have explored the acceptability of telephone consultations for delivering psychosocial support with mixed findings. Whilst some found that sensitive conversations can occur effectively [14], others found that professionals and patients may struggle to give and receive emotional support [29]. In our study only 5 of the 48 physicians surveyed stated that breaking bad news was appropriate over the telephone. By comparison, half of respondents felt that carer support could be provided, suggesting that there is scope for psychological support and rapport-building. Exploration of this topic with patients and caregivers highlighted the importance of the existing clinical relationship. Psychosocial support was considered more effective over the phone if a professional relationship already existed, suggesting that the depth of the relationship, rather than the content of the conversation, is more important, and may explain the variation in research findings to date.

Virtual consultations - gate-keeping and technology challenges

Patients are known to be more accepting of telemedicine than professionals [26, 30], particularly after face-to-face consultations [31]. Similarly, we found that whilst palliative care physicians felt face-to-face consultations were rarely inappropriate, patients emphasised the benefits of a blended service - namely that the value of in-person appointments should be balanced against the physical burden of attending appointments. Occasional clinical contact, even when well, was valued by patients, particularly those with a limited social network [32, 33], however we found less reliance on face-to-face consultations than shown previously, which may be a result of increased telemedicine use since the Covid-19 pandemic [34, 35]. Interestingly, physician respondents in this study frequently mentioned challenges they perceived patients to experience with video consultations, such as anxiety or practical inability, which contrasted with patients reported comfort. None of the 48 physicians suggested professional anxiety as a barrier, despite previous findings that staff can act as ‘gatekeepers’ to the use of technologies [36]. This shows that beyond the provision of, or access to, virtual technologies, there exists a barrier for patients in how the service is presented.

Separate to anxiety or practical inability, technological concerns are commonly raised as a barrier to the use of virtual technologies in healthcare - both by patients and healthcare professionals [12, 28]. Our study found similar concerns amongst healthcare professionals despite being conducted post the Covid-19 pandemic. Research has established that easily accessible and reliable technology, alongside adequate user training, are critical to the success of telehealth initiatives [37]. Whilst acceptability of virtual consultations increased during the pandemic, the importance of addressing the technological and training aspects of telemedicine when developing a virtual service remains. Even post-Covid-19, the two main barriers identified to the adoption of telemedicine were technical literacy and the need for technological development [6]. But self-reported scores of readiness to use video consultations improve with increased use [15], showing the impact of professional’s familiarity and confidence on successful incorporation.

Recommendations for clinical practice

We found evidence for patient benefit from integrating virtual and face-to-face consultations in outpatient palliative care services. Different modes should be used flexibly to support, rather than replace, each other, and a blended outpatient service should capitalise on the benefits that each approach delivers to provide an effective and efficient service. An overreliance on virtual consultations is potentially damaging and correlates with patients still valuing face-to-face consultations, whereas in-person only clinics can be burdensome in terms of travel and time for patients. In this study, the early introduction of video consultations is advocated to encourage future use when needed.

We recommend the following for outpatient palliative care services.

That face-to-face consultations:

are used for an initial consultation; where there is a clinical concern; and, for situations that require a physical examination.

should continue intermittently throughout the patient journey to support relationship building.

may be best for psychosocial interventions and/or breaking bad news, dependent on patient preference and depth of professional relationship.

are not always necessary for stable or predictable situations.

That telephone consultations are:

-

5.

appropriate for stable or predictable situations, medication reviews, and as a triage tool.

-

6.

feasible for delivering psychological support, dependent on patient preference and depth of professional relationship.

-

7.

inappropriate for complex consultations, particularly those with a physical component.

That video consultations are:

-

8.

introduced early in a patient journey to encourage familiarity.

-

9.

supported by telephone back-up.

-

10.

used to reduce the travel and time burden that patients experience when attending outpatient appointments.

-

11.

acceptable for psychosocial interventions and/or breaking bad news, dependent on patient preference and depth of professional relationship.

When developing a blended outpatient palliative care service adequate healthcare professional training alongside reliable, user-friendly technology is vital for successful implementation. We further recommend:

-

12.

integrating different modes of consultation early in a patient journey without over-reliance on one mode.

-

13.

that patient preference be a key factor when choosing consultation mode, acknowledging that clinician guidance for the most appropriate modality is also valued by patients.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is its use of mixed methods to explore a complex intervention. By combining both quantitative data from palliative care physicians with qualitative data from patients and caregivers we were able to explore the benefits and limitations of different consultation formats to a greater extent. We also used our findings to develop practical recommendations for clinical practice.

Limitations of our study include the small sample sizes for both components. For the online survey (component 1) information about the study and a link to access the survey was sent to all members of the Association of Palliative Medicine via email as part of their quarterly bulletin. The email distribution list contains 1,300 palliative care professionals but we do not have information about how many of these people read the emails and/or how many of those on the mailing list would meet the study’s eligibility criteria. We were therefore not able to determine the actual response rate, but anticipate that this was low, meaning our findings may be less representative of a wider population.

Our qualitative component was also limited to patients and caregivers recruited via one hospice site and to those who could use MS Teams. This limited the generalisability of our findings by restricting our sample to those capable of handling the necessary IT. Future research exploring the views of those who do not have access to, or experience of, virtual technologies would be valuable.

Lastly, our patients were recruited from hospice outpatient clinics, whereas most of the palliative care physicians that responded to our online survey worked in a hospital setting which limited the strength when triangulating our findings.

Conclusions

A blended approach to outpatient palliative care services is viewed positively by physicians, patients and caregivers. To be effective, patient preference should be a key factor when arranging appointments. Different consultation formats should also be encouraged early in a patient journey to prevent over-reliance on one mode.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the study conception and design. CM collected and analysed all data. DW and LAH supported data analysis and interpretation. CM drafted the manuscript with substantive revisions by DW and LAH. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this project.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study has been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the UK Research Ethics Committee (project ID 308342). I, the submitting author, declare that all methods in this work were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hui D, Bruera E. Models of palliative care delivery for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):852–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finlay E, Rabow MW, Buss MK. Filling the gap: creating an outpatient palliative care program in your institution. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educational Book. 2018;38:111–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, Lovell N, Evans CJ, Higginson IJ, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017;15:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kazley AS, McLeod AC, Wager KA. Telemedicine in an international context: definition, use, and future. Health information technology in the international context. Volume 12. Emerald Group Publishing Limited; 2012. pp. 143–69. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Kruse C, Heinemann K. Facilitators and barriers to the adoption of telemedicine during the first year of COVID-19: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(1):e31752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kidd L, Cayless S, Johnston B, Wengstrom Y. Telehealth in palliative care in the UK: a review of the evidence. J Telemed Telecare. 2010;16(7):394–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macchi ZA, Ayele R, Dini M, Lamira J, Katz M, Pantilat SZ, et al. Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for improving outpatient neuropalliative care: a qualitative study of patient and caregiver perspectives. Palliat Med. 2021;35(7):1258–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Onesti CE, Tagliamento M, Curigliano G, Harbeck N, Bartsch R, Wildiers H, et al. Expected medium-and long-term impact of the COVID-19 outbreak in oncology. JCO Global Oncol. 2021;5(1):162–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Atreya S, Kumar G, Samal J, Bhattacharya M, Banerjee S, Mallick P, et al. Patients’/Caregivers’ perspectives on telemedicine service for advanced cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: an exploratory survey. Indian J Palliat Care. 2020;26(Suppl 1):S40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baxter KE, Kochar S, Williams C, Blackman C, Himmelvo J. Development of a palliative telehealth pilot to meet the needs of the nursing home population. J Hospice Palliat Nurs. 2021;23(5):478–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Collier A, Morgan DD, Swetenham K, To TH, Currow DC, Tieman JJ. Implementation of a pilot telehealth programme in community palliative care: a qualitative study of clinicians’ perspectives. Palliat Med. 2016;30(4):409–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutherland AE, Bradley V, Walding M, Stickland J, Wee B. Palliative medicine video consultations in the pandemic: patient feedback. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.van Gurp J, van Selm M, Vissers K, van Leeuwen E, Hasselaar J. How outpatient palliative care teleconsultation facilitates empathic patient-professional relationships: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4):e0124387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perri GA, Abdel-Malek N, Bandali A, Grosbein H, Gardner S. Early integration of palliative care in a long-term care home: a telemedicine feasibility pilot study. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18(4):460–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matusitz J, Breen G-M. Telemedicine: its effects on health communication. Health Commun. 2007;21(1):73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demiris G, Oliver DP, Courtney KL. Ethical considerations for the utilization of telehealth technologies in home and hospice care by the nursing profession. Nurs Adm Q. 2006;30(1):56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 3rd ed. London: SAGE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Association of Palliative Medicine of Great Britain and Ireland. (2023). Home Page.https://apmonline.org/ (Accessed: 22nd January 2024).

- 20.Health Research Authority. (2024). Planning and improving research.https://www.hra.nhs.uk/planning-and-improving-research/ (Accessed: 16th July 2024).

- 21.St Ann’s Hospice. (1998). About us.https://www.sah.org.uk/about-us/ (Accessed: 22nd January 2024).

- 22.Given LM. The sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgan DL, Nica A. Iterative Thematic Inquiry: a New Method for analyzing qualitative data. Int J Qualitative Methods. 2020;19:1609406920955118. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6pt2):2134–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tasneem S, Kim A, Bagheri A, Lebret J. Telemedicine video visits for patients receiving palliative care: a qualitative study. Am J Hospice Palliat Medicine®. 2019;36(9):789–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zimmermann J, Heilmann ML, Fisch-Jessen M, Hauch H, Kruempelmann S, Moeller H, et al. Telehealth needs and concerns of stakeholders in pediatric palliative home care. Children. 2023;10(8):1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Read Paul L, Salmon C, Sinnarajah A, Spice R. Web-based videoconferencing for rural palliative care consultation with elderly patients at home. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:3321–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liptrott S, Bee P, Lovell K. Acceptability of telephone support as perceived by patients with cancer: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27(1):e12643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tasneem S, Kim A, Bagheri A, Lebret J. Telemedicine Video visits for patients receiving palliative care: a qualitative study. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(9):789–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheung KL, Tamura MK, Stapleton RD, Rabinowitz T, LaMantia MA, Gramling R. Feasibility and acceptability of Telemedicine-facilitated Palliative Care consultations in Rural Dialysis Units. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(9):1307–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milne S, Palfrey J, Berg J, Todd J. Video hospice consultation in COVID-19: professional and patient evaluations. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care; 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Steindal SA, Nes AAG, Godskesen TE, Dihle A, Lind S, Winger A, et al. Patients’ experiences of telehealth in palliative home care: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(5):e16218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atreya S, Kumar G, Samal J, Bhattacharya M, Banerjee S, Mallick P, et al. Patients’/Caregivers’ perspectives on Telemedicine Service for Advanced Cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: an exploratory survey. Indian J Palliat Care. 2020;26(Suppl 1):S40–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitchell S, Maynard V, Lyons V, Jones N, Gardiner C. The role and response of primary healthcare services in the delivery of palliative care in epidemics and pandemics: a rapid review to inform practice and service delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med. 2020;34(9):1182–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitten P, Holtz B, Nazione S. Searching for barriers to adoption of the videophone in a hospice setting. J Technol Hum Serv. 2009;27(4):307–22. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nguyen M, Fujioka J, Wentlandt K, Onabajo N, Wong I, Bhatia R, et al. Using the technology acceptance model to explore health provider and administrator perceptions of the usefulness and ease of using technology in palliative care. BMC Palliat care. 2020;19(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.