Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a spectrum of inflammatory conditions, including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Although IBD primarily affects the intestinal tract, extraintestinal manifestations, such as musculoskeletal, ophthalmologic, and cutaneous conditions, are common. Over 1.6 million Americans carry a diagnosis of IBD and worldwide prevalence rates continue to rise over time.1 Despite major advances in medical management, surgery continues to play a supportive and complementary role in the treatment of IBD.2, 3 Between 20–40% of UC patients and up to 75% of CD patients will require surgery in their lifetime, with most operations taking place due to either failure of medical management or disease complications, such as fulminant colitis, intestinal obstruction, infection/fistula, or neoplasia.3 This review will focus on several advances in management of IBD from the surgical perspective.

Trends, Indications, and Timing of Surgery in the Biologic Era

Whether or not surgery for IBD has become less common as medical management improves remains complex and somewhat unclear. Several large cohort studies appear to demonstrate a reduction in colectomy rates among UC patients over time that coincides with an increased use of immunomodulatory and biologic medications.4–6 Among hospitalized patients with severe UC, infliximab has been associated with a significant reduction in the risk of colectomy in multiple randomized trials.7, 8 However, several population-based studies have found both no difference in the long-term risk of colectomy and no change in emergency colectomy rates over time, suggesting that biologics may be more useful in shifting urgent procedures to elective setting rather than obviating the need for surgery altogether.9–11 Interestingly, one large institutional sample and several nationwide cohort studies have demonstrated an increase in the proportion of colectomies performed for either dysplasia or cancer, again suggesting that medical management may lead to better short-term but not necessarily longer-term disease control.12–14

Rates of surgical resection among patients with CD also appear to be decreasing over time and in conjunction with an increased use of biologic medications.9, 15 Several authors note, however, that changes in surgery rates also parallel changes in other potential confounding factors, such as disease severity at diagnosis and cigarette smoking, making causal links less certain. At least one nationwide cohort study also found that, while primary resection rates dropped by nearly two-thirds, secondary resection rates remained unchanged, suggesting that some patients either remain refractory to medical therapy or experience decreasing efficacy over time.15 Although multiple clinical trials have demonstrated an association between biologics and lower rates of anal fistula surgery, similar trends have not necessarily been reproduced in population-based studies.9, 16–19

The impact of biologics on surgical complication rates also remains hotly debated. Multiple retrospective, single institution studies have demonstrated mixed results, leading to confusion and conflicting recommendations.20–22 Recent results from the PUCCINI trial, however, finally provide some clarity, at least for anti-TNF medications. Based on a prospective cohort of patients undergoing abdominal surgery for either UC or CD at 17 U.S. centers, Cohen et al. report no difference in either overall infection or surgical site infections rates between patients with recent a exposure to anti-TNF agents (within 12 weeks of surgery) and controls.23, 24 Moreover, patients with detectable anti-TNF levels appeared to have no increase in either overall or surgical site infection rates when compared to controls, calling into question prior theories regarding dose response rates. Armed with these results, many surgeons now choose to continue anti-TNF medications during the preoperative period or to time surgery based upon the medication’s dosing interval. The peri-operative safety of newer biologic and small molecule therapies are still under investigation, although multiple studies on vedolizumab appear to show no clear increase in complication rates.25, 26 Optimal timing for restarting patients on therapy after surgery and the associated prophylactic benefit of various therapies is less well established; most surgeons choose to restart biologic medications at 4 to 8 weeks after resection, depending on recovery and functional status.27, 28

Enhanced Recovery Protocols

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols have been a paradigm shift in perioperative management. Born out of the general colorectal field, ERAS protocols aim to promote faster recovery after surgery.29 The encompassing approach focuses on preoperative counseling, nutrition optimization, standardized anesthetic regimens, multimodal pain control, and early initiation of mobilization and enteral nutrition.30 As evidence has demonstrated improved outcomes in colorectal procedures, such protocols are being adopted in IBD patients.

The prehabilitation phase for scheduled procedures in IBD patients focuses on nutritional status and supplementation.31, 32 The chronic inflammatory and malabsorptive state associated with IBD produces a high risk for malnutrition. Malnourished patients are at significantly higher risk for complications following surgical procedures.33, 34 In elective procedures, guidelines recommend thorough assessment of nutritional status.31, 32 For patients identified as being malnourished, surgery should be delayed, and nutritional therapy initiated.31, 32 Enteral therapy is generally preferred to parenteral nutrition unless contraindications exist.35

Patients in the ERAS protocol can have clear liquids up to 2 hours prior to anesthesia. Intravenous fluids are limited. Epidural analgesia is used, and premedication is withheld. Standardized multimodal pain regimens and anesthesia are used in the perioperative setting. Decompressive gastrointestinal tubes are not routinely placed, and oral intake is initiated as soon as patients recover from anesthesia. Patients are advanced to solid food as tolerated. Urinary catheters are removed on post operative day one and early ambulation is encouraged.29, 30 Outcomes from ERAS protocol in ileocecectomies for CD have demonstrated shorter return of bowel function, initiation of solid oral intake, and earlier discharge from the hospital.37, 38

Minimally Invasive Surgery

Minimally invasive surgery has revolutionized intraabdominal procedures. The advantages of laparoscopic procedures in IBD has been supported in the past two decades of literature. In general, laparoscopic interventions are associated with decreased pain, ileus, and hospital stays when compared to open operations.39, 40 Laparoscopic procedures have lower overall costs then open procedures in the IBD population.39 Minimally invasive operations produce fewer adhesions compared to open surgeries which has increased importance for CD patients given the chronic nature of the disease and requirement for multiple operations.41

While it has been well established that the use of laparoscopy has resulted in shorter length of stay postoperatively, improved body image, decreased infertility rates, and decreased intravenous narcotic use among IBD patients, in recent years, the da Vinci robot (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, California) has become an increasingly popular and accepted modality in colorectal surgery for both benign and malignant conditions.42–48 Many studies including meta-analyses have now reported equivalent safety and efficacy with a robotic approach in colorectal operations as compared to conventional laparoscopy.49 The improved dexterity, visualization and ergonomics of the robotic platform have contributed to the surge in the adoption of the robotic platform. This trend of increased use has been seen in IBD surgery with many IPAAs in UC and segmental resections in CD now being performed on a robotic platform despite an increased cost and lack of haptic feedback.50–52

The most common operation performed in Crohn’s disease is an ileocecal resection. A robotic approach allows the surgeon to perform an intracorporeal anastomosis (ICA), which has been associated with decreased rates of postoperative ileus and decreased incisional hernia rates since the extraction site can be moved off the midline.53–57 An ICA also minimizes the amount of colon mobilization necessary, which allows the duodenum to remain in the retroperitoneum protected by the right colon and its mesentery. This is relevant in CD since most fistula to the duodenum in CD originate from recurrent ileal disease after an ileocolic resection. These can be quite difficult to treat. Thus, by avoiding mobilization of the ascending colon, rates of fistula to the duodenum may be decreased.58

While there are a limited number of published series of a robotic approach in CD, there are many more for UC given the most common operation involved a pelvic dissection, proctectomy, with IPAA. Several series have shown a robotic approach is safe with equivalent short term postoperative outcomes to a laparoscopic approach.59–61 A case-matched comparison of robotic versus laparoscopic proctectomy showed no difference in postoperative complications, and a trend toward improvement in conversion rate, time to bowel function, and LOS with the robotic approach.62 An observational series including 81 robotic versus 170 open IPAA from a single institution described similar short-term outcomes with improved LOS in the robotic group, but longer operative times and higher readmission rates.63

Transanal total mesorectal excision (TaTME) refers to a retrograde laparoscopic approach combined with a transabdominal laparoscopic approach to remove the rectum. This technique was initially described and mainly utilized in the treatment of low rectal cancers.64 It has the advantage of improved visualization of the natural planes in the pelvis especially in the narrow male pelvis. This approach to proctectomy has been embraced by highly trained and skilled surgeons but some recent reports of CO2 embolism with this technique have led to concerns with this approach.65 There have been individual case reports of laparoscopic total abdominal colectomy with TaTme and ileal anal pouch for ulcerative colitis.66 Although these case reports are intriguing much more data needs to be collected before this becomes a recommended approach to this complex disease and should be considered experimental at this time.

While data on robotic surgery for CD and UC continues to evolve, the current studies that a minimally invasive approach to IBD offers benefits to the patient. The robotic platform presents improved visualization, instrumentation, and dexterity.

Anastomotic Configurations

A critical component of bowel resections is the ensuing anastomosis. In CD this new connection is commonly the site of early disease recurrence.2 Recurrence at the anastomosis can be as high as 35–85% when evaluated endoscopically, and recurrence requiring surgery can be up to 50% within 20 years.3, 67, 68 Surgical techniques to reduce anastomotic disease recurrence and associated complications continue to be evaluated. In the general population, surgical staplers have demonstrated comparable outcomes to hand-sewn anastomoses, with some studies demonstrating lower leak rates after ileocolic resections.69 Side-to-side anastomosis (STSA) are commonly performed using a stapled technique. In the setting of IBD, particularly in CD, the STSA may create a non-peristaltic reservoir that promotes early disease recurrence.70 End-to-end anastomosis (ETEA) produces a more physiologic connection. Studies have demonstrated similar recurrence rates when comparing ETEA to STSA; but ETEA may produce improved quality of life, easier endoscopic evaluation, and less health care utilization.70

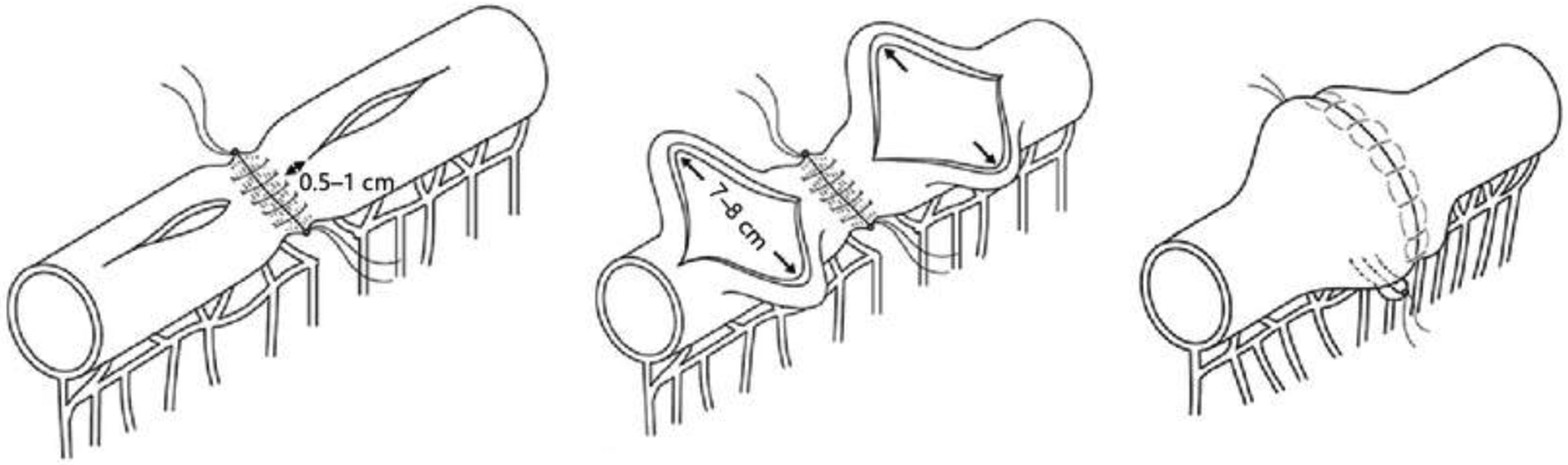

The Kono-S anastomosis was initially created by Dr. Toro Kono and colleagues in Japan in 2003 in an effort to reduce anastomotic recurrence.71 The basis of the technique is an antimesenteric functional end-to-end anastomosis. The anastomosis has produced promising results with surgical recurrence-free survival rates of 98.6% over a 10-year period.72, 73 Theoretical benefits of the anastomosis include a supporting column to maintain diameter limiting stenosis.72 It is a functional ETEA which allows for easier endoscopic monitoring and interventions if stenosis does occur.72, 73

Mesenteric Resection in Crohn’s Surgery

A significant volume of research has been conducted to determine how to prevent postoperative recurrence of CD following an ileocolic resection. Some studies have focused on the timing of resuming postoperative medical therapy. Others have looked at surgical techniques at the time of ileocolic resection including anatomic configuration of the anastomosis and performing a stapled versus handsewn anastomosis. Interestingly, there is recent evidence to suggest that CD may be a disease of the mesentery rather than just the mucosa of the bowel alone. In CD, the transmural inflammation facilitates increased bacterial translocation into the creeping fat. These translocating antigens and activate adipocytes which are cells than have complex metabolic and immunologic functions.75 Additionally, it is thought that functional abnormalities in the mesenteric structures exert an inflammatory effect: the secretion of adipokines that have endocrine functions contribute to immunomodulation through a response to afferent signals, neuropeptides, and functional cytokines; mesenteric nerves are involved in the pathogenesis through neuropeptides; and lymphatics in the mesentery may obstruct, remodel, and impair contraction, contributing to the irregularly thickened mesentery seen in CD. Interestingly, the interaction between neuropeptides, adipokines, and vascular and lymphatic endothelia leads to adipose tissue remodeling. This makes the mesentery an active participant in CD, seemingly as much as the bowel itself.76 However, the mesentery is typically spared, or left in situ, during resection for CD, unlike resections for adenocarcinoma of the colon where a high ligation is performed.

Findings from a retrospective review by Coffey et al spearheaded momentum to consider performing a high ligation in CD at the time of an ileocecal resection.77 In this study, those patients who underwent a high ligation (n=34) compared to those with a mesenteric sparing approach (n=30) had a significantly lower rate of surgical recurrence (40% vs 2.9%; p=0.003). The mesenteric disease activity in this study predicted surgical recurrence, underscoring the relevance of the mesentery in driving disease recurrence.77 This has prompted the initiation of several international multicenter randomized control trials to study this particular question of whether a high ligation at the time of ileocecal resection can reduce rates of disease recurrence following an ileocecal resection.

Segmental Colectomy in CD

Although medically refractory Crohn’s colitis has traditionally been treated with either subtotal colectomy (STC) or total proctocolectomy (TPC), there is growing interest in performing more limited resections, at least for select patients. Compared to STC or TPC, segmental colectomy (SC) allows for preservation of bowel length and function as well as, potentially, a lower likelihood of stoma formation. On the other hand, these benefits must be weighed against the risk and timing of disease recurrence as well as the possibility of higher rates of surgical complications, including anastomotic leak.

Multiple observational studies have compared SC to STC, including two systematic reviews. Tekkis et al. 2006 found no difference in overall or surgical recurrence, although patients undergoing SC required reoperation an average of 4.4 years earlier than those undergoing STC.78 Angriman et al. 2017 performed an updated review, including a total of 11 studies and 1436 patients.79 Again, there was no difference in overall or surgical recurrence between the groups even when limiting the analysis to studies performed during the biologic era. Interestingly, however, patients undergoing SC had a significantly lower rate of any stoma (OR 0.26, p=0.001) and permanent stoma formation (OR 0.52, p=0.001).79 Overall, recurrence rates appear to vary between 40–60% depending on the population and follow-up period.80–83

Although neither review specifically commented on anastomotic leak, Kiran et al. 2011 found no difference in anastomotic leak (2% vs. 3%, p=1.0), abdominal abscess (4% vs. 2%, p=0.59), or 30-day readmissions rates (16% vs. 7%, p=0.13) in a large, retrospective series of patients undergoing either SC or STC for Crohn colitis.84 Angriman and colleagues did find a higher rate of post-operative complications among patients undergoing SC when compared to STC, however, they provided no additional information regarding the type or severity of the complications they identified.79

As with many decisions in IBD, the choice between SC and STC in the setting of Crohn’s colitis should be individualized. Surgeons need to weigh the risks and benefits of surgery, including how well a patient would tolerate a major complication and how likely a patient will be to adhere to ongoing surveillance. After safety concerns are met, quality of life becomes paramount. SC offers better bowel function, on average, than STC or TPC without an apparent difference in the likelihood of recurrence. For that reason, select patients with segmental inflammation that either does not respond to medical management or results in a local complication (e.g., fistula or stricture) are increasingly being offered SC and continued surveillance rather than STC or TPC.

Surgical Considerations for Dysplasia

Dysplasia of the colonic mucosa remains a controversial topic. There are two major classifications of this disease process associated with ulcerative colitis. The first is the histologic presence of dysplasia obtained by random biopsies at the time of surveillance colonoscopy, referred to as invisible dysplasia. The other is visible dysplasia best described using the Paris Classification combined with Kudo pit pattern. Both pathologic classifications have gone through significant evolution over the past 20 years and have resulted in changes in recommendations of treatment.

Visible lesions were (previously sometimes referred to as DALMs) considered aggressive and the presence warranted a total proctocolectomy. The term DALM (Dysplasia Associated Lesion or Mass) is no longer used and instead, lesions should be described according to the Paris Classification. Recent studies support colon preservation if the lesion can be endoscopically removed in its entirety and without evidence of malignancy.85 Some lesions require advanced endoscopic skills for proper removal and endoscopists should appropriately refer to a colleague with those skills for endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection; in that setting, the best approach is to leave the lesion alone but mark near it (4–5 cm distal) with India Spot. Manipulation of the lesion with even biopsy can result in scarring that makes complete endoscopic removal technically more difficult. Long term outcomes demonstrate that 50–65% of patients will develop metachronous adenomas similar to rates seen in non-UC adenoma cohorts. With close endoscopic surveillance many of these patients can avoid colectomy without a significant risk of malignancy.86

The finding of invisible dysplasia has been considered a predictor of developing a future malignancy and the presence of co-existent cancer. The nomenclature has been simplified to indefinite for dysplasia (IND), low grade dysplasia (LGD) and high grade dysplasia (HGD) with noted significant interobserver variability.87 Patients with HGD, defined as severe nuclear changes and the nuclei extending to the upper third of the cell, should undergo total proctocolectomy. The decision of colectomy vs. continued surveillance in patients with LGD, defined as cells having enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei limited to the lower two thirds of the cell, is still controversial. Historically, most surgeons and gastroenterologists agreed that surveillance in these patients is acceptable with low risk of malignancy. However, some recent studies advocate for colectomy in these patients due to 9–20% of patients progressing to carcinoma in an average of 6 years.88

Perianal Fistulizing Disease

Perianal fistulas are a major source of morbidity in Crohn’s disease with 17–50% of patients experiencing fistula during the duration of their disease.89 Rates of fistula closure have improved with the use of biologic medical therapies.18, 19 Newer surgical techniques for complex fistula, such as ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT), have aimed to improve healing while preserving fecal continence.90 Rates of healing after the LIFT procedure have been shown to be 40–60% with low rates of sphincter compromise.90, 91 In addition to intrabdominal surgery, minimally invasive methods have been developed for fistula procedures. Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) is a sphincter sparing technique with improved visualization of the internal opening of the fistula tract.92 In addition to sphincter sparing, advantages of this novel method include faster healing and earlier return to work when compared to traditional seton techniques.93 Given high recurrence rates and surgical morbidity, there has been an interest in augmented healing of fistula with various products such as plugs, glues, and other biomaterials. Adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells (ADSC) have shown promise in a phase III randomized control trial where healing rates were 50% versus 34% in the placebo arm.94 There has yet to be a definitive approach to management of challenging fistula in the setting of CD. The vast array of techniques and therapeutic adjuncts allow the surgeon to tailor the approach to the individual patient.

Telemedicine in the Surgical Patient

Telemedicine and its rapid evolution have much to offer IBD surgery; it will play an increasing role in IBD surgical care. Telemedicine has been present in healthcare since 2000 and rapidly expanded with advances in telecommunication capabilities. The COVID pandemic transformed the landscape for telemedicine and rapidly advanced physician and patient awareness and acceptance.95 Currently, 15–20% of outpatient visits are conducted using telemedicine at a national level.

Due to the complexity of IBD patients, their care is typically conducted in a multi-disciplinary approach including several non-surgical teams. Telemedicine enables these teams to coordinate care and come together using video conferencing.96 Telemedicine fundamentally enables patients and physicians to access patients at a distance. This has implications for diversity, equity, and inclusion for the IBD care of all patients.

Conclusion

The ever-changing landscape of IBD treatment presents a unique balance of medical and surgical co-management. IBD practitioners must be well versed in advances in the entire field of these inflammatory conditions to provide optimal patient care. A multidisciplinary approach involving the surgeon, gastroenterologist, pathologist, radiologist, nutritionist, and others with patient engagement is critical to optimal patient management and outcomes.

Figure 1.

Perioperative nutritional assessment and optimization in IBD patients. Adapted from da Silva et al. 2021 and European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism guidelines.31, 36

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of the Kono-S anastomosis, adapted from Luglio and Kono 2021.74 Licensed by Creative Commons https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number T32CA113263. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Footnotes

The University of Pittsburgh holds a Physician-Scientist Institutional Award from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund

References

- 1.Ng SC, et al. , Worldwide incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in the 21st century: a systematic review of population-based studies. Lancet, 2017. 390(10114): p. 2769–2778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frolkis AD, et al. , Risk of Surgery for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Has Decreased Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Population-Based Studies. Gastroenterology, 2013. 145(5): p. 996–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fichera A and Michelassi F, Surgical Treatment of Crohn’s Disease. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, 2007. 11(6): p. 791–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rungoe C, et al. , Changes in medical treatment and surgery rates in inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide cohort study 1979–2011. Gut, 2014. 63(10): p. 1607–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olaiya B, et al. , Trends in Morbidity and Mortality Following Colectomy Among Patients with Ulcerative Colitis in the Biologic Era (2002–2013): A Study Using the National Inpatient Sample. Dig Dis Sci, 2021. 66(6): p. 2032–2041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes EL, et al. , Decreasing Colectomy Rate for Ulcerative Colitis in the United States Between 2007 and 2016: A Time Trend Analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2020. 26(8): p. 1225–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandborn WJ, et al. , Colectomy Rate Comparison After Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis With Placebo or Infliximab. Gastroenterology, 2009. 137(4): p. 1250–1260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rutgeerts P, et al. , Infliximab for Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. New England Journal of Medicine, 2005. 353(23): p. 2462–2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atia O, et al. , Colectomy Rates did not Decrease in Paediatric- and Adult-Onset Ulcerative Colitis During the Biologics Era: A Nationwide Study From the epi-IIRN. Journal of Crohn’s & colitis, 2022. 16(5): p. 796–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aratari A, et al. , Colectomy rate in acute severe ulcerative colitis in the infliximab era. Dig Liver Dis, 2008. 40(10): p. 821–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan GG, et al. , Decreasing colectomy rates for ulcerative colitis: a population-based time trend study. Am J Gastroenterol, 2012. 107(12): p. 1879–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchino M, et al. , Changes in the rate of and trends in colectomy for ulcerative colitis during the era of biologics and calcineurin inhibitors based on a Japanese nationwide cohort study. Surg Today, 2019. 49(12): p. 1066–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baek SJ, et al. , Current Status and Trends in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Surgery in Korea: Analysis of Data in a Nationwide Registry. Ann Coloproctol, 2018. 34(6): p. 299–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Remzi FH, et al. , Restorative proctocolectomy: an example of how surgery evolves in response to paradigm shifts in care. Colorectal Dis, 2017. 19(11): p. 1003–1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jenkinson PW, et al. , Temporal Trends in Surgical Resection Rates and Biologic Prescribing in Crohn’s Disease: A Population-based Cohort Study. J Crohns Colitis, 2020. 14(9): p. 1241–1247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poggioli G, et al. , Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease. Therapeutics and clinical risk management, 2007. 3(2): p. 301–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubenstein JH, Chong RY, and Cohen RD, Infliximab Decreases Resource Use Among Patients With Crohn’s Disease. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 2002. 35(2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sands BE, et al. , Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med, 2004. 350(9): p. 876–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colombel JF, et al. , Adalimumab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gut, 2009. 58(7): p. 940–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zittan E, et al. , Preoperative Anti-tumor Necrosis Factor Therapy in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis Is Not Associated with an Increased Risk of Infectious and Noninfectious Complications After Ileal Pouch-anal Anastomosis. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2016. 22(10): p. 2442–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Syed A, Cross RK, and Flasar MH, Anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy is associated with infections after abdominal surgery in Crohn’s disease patients. Am J Gastroenterol, 2013. 108(4): p. 583–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alsaleh A, et al. , Timing of Last Preoperative Dose of Infliximab Does Not Increase Postoperative Complications in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients. Digestive diseases and sciences, 2016. 61(9): p. 2602–2607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen BL, et al. , Prospective Cohort Study to Investigate the Safety of Preoperative Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor Exposure in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Undergoing Intra-abdominal Surgery. Gastroenterology, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohen BL, et al. , Prospective Cohort Study to Investigate the Safety of Preoperative Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitor Exposure in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Undergoing Intra-abdominal Surgery. Gastroenterology, 2022. 163(1): p. 204–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lightner AL, et al. , Postoperative Outcomes in Vedolizumab-Treated Patients Undergoing Major Abdominal Operations for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Retrospective Multicenter Cohort Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2018. 24(4): p. 871–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lightner AL, et al. , Surgical Outcomes in Vedolizumab-Treated Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2017. 23(12): p. 2197–2201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regueiro M, et al. , American Gastroenterological Association Institute Technical Review on the Management of Crohn’s Disease After Surgical Resection. Gastroenterology, 2017. 152(1): p. 277–295.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nguyen GC, et al. , American Gastroenterological Association Institute Guideline on the Management of Crohn’s Disease After Surgical Resection. Gastroenterology, 2017. 152(1): p. 271–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wind J, et al. , Systematic review of enhanced recovery programmes in colonic surgery. Br J Surg, 2006. 93(7): p. 800–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melnyk M, et al. , Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols: Time to change practice? Canadian Urological Association journal = Journal de l’Association des urologues du Canada, 2011. 5(5): p. 342–348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.da Silva ISM, et al. , Perioperative Nutritional Optimization in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: When and How? Journal of Coloproctology, 2021. 41(03): p. 295–300 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adamina M, et al. , Perioperative Dietary Therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis, 2020. 14(4): p. 431–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alves A, et al. , Risk factors for intra-abdominal septic complications after a first ileocecal resection for Crohn’s disease: a multivariate analysis in 161 consecutive patients. Dis Colon Rectum, 2007. 50(3): p. 331–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pedersen M, Cromwell J, and Nau P, Sarcopenia is a Predictor of Surgical Morbidity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2017. 23(10): p. 1867–1872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forbes A, et al. , ESPEN guideline: Clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr, 2017. 36(2): p. 321–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bischoff SC, et al. , ESPEN practical guideline: Clinical Nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr, 2020. 39(3): p. 632–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mineccia M, et al. , A retrospective study on efficacy of the ERAS protocol in patients undergoing surgery for Crohn disease: A propensity score analysis. Dig Liver Dis, 2020. 52(6): p. 625–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spinelli A, et al. , Short-term outcomes of laparoscopy combined with enhanced recovery pathway after ileocecal resection for Crohn’s disease: a case-matched analysis. J Gastrointest Surg, 2013. 17(1): p. 126–32; discussion p.132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Young-Fadok TM, et al. , Advantages of laparoscopic resection for ileocolic Crohn’s disease. Improved outcomes and reduced costs. Surg Endosc, 2001. 15(5): p. 450–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan WH, et al. , Opioid Medication Use in the Surgical Patient: An Assessment of Prescribing Patterns and Use. J Am Coll Surg, 2018. 227(2): p. 203–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bartels SA, et al. , Less adhesiolysis and hernia repair during completion proctocolectomy after laparoscopic emergency colectomy for ulcerative colitis. Surg Endosc, 2012. 26(2): p. 368–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Larson DW, et al. , Safety, feasibility, and short-term outcomes of laparoscopic ileal-pouch-anal anastomosis: a single institutional case-matched experience. Ann Surg, 2006. 243(5): p. 667–70; discussion 670–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.White I, et al. , Outcomes of laparoscopic and open restorative proctocolectomy. Br J Surg, 2014. 101(9): p. 1160–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahmed Ali U, et al. , Open versus laparoscopic (assisted) ileo pouch anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2009(1): p. CD006267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bartels SA, et al. , Significantly increased pregnancy rates after laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy: a cross-sectional study. Ann Surg, 2012. 256(6): p. 1045–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Beyer-Berjot L, et al. , A total laparoscopic approach reduces the infertility rate after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a 2-center study. Ann Surg, 2013. 258(2): p. 275–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Y, et al. , Robot-assisted versus conventional laparoscopic surgery for colorectal disease, focusing on rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol, 2012. 19(12): p. 3727–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Juo YY, et al. , Is minimally invasive colon resection better than traditional approaches?: First comprehensive national examination with propensity score matching. JAMA Surg, 2014. 149(2): p. 177–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Trinh BB, et al. , Robotic versus laparoscopic colorectal surgery. JSLS, 2014. 18(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rawlings AL, et al. , Robotic versus laparoscopic colectomy. Surg Endosc, 2007. 21(10): p. 1701–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tyler JA, et al. , Outcomes and costs associated with robotic colectomy in the minimally invasive era. Dis Colon Rectum, 2013. 56(4): p. 458–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bertani E, et al. , Assessing appropriateness for elective colorectal cancer surgery: clinical, oncological, and quality-of-life short-term outcomes employing different treatment approaches. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2011. 26(10): p. 1317–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Morpurgo E, et al. , Robotic-assisted intracorporeal anastomosis versus extracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic right hemicolectomy for cancer: a case control study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A, 2013. 23(5): p. 414–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grams J, et al. , Comparison of intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis in laparoscopic-assisted hemicolectomy. Surg Endosc, 2010. 24(8): p. 1886–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trastulli S, et al. , Robotic right colectomy with intracorporeal anastomosis compared with laparoscopic right colectomy with extracorporeal and intracorporeal anastomosis: a retrospective multicentre study. Surg Endosc, 2015. 29(6): p. 1512–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Casillas MA Jr., et al. , Improved perioperative and short-term outcomes of robotic versus conventional laparoscopic colorectal operations. Am J Surg, 2014. 208(1): p. 33–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Samia H, et al. , Extraction site location and incisional hernias after laparoscopic colorectal surgery: should we be avoiding the midline? Am J Surg, 2013. 205(3): p. 264–7; discussion 268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacobson IM, Schapiro RH, and Warshaw AL, Gastric and duodenal fistulas in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology, 1985. 89(6): p. 1347–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McLemore EC, et al. , Robotic-assisted laparoscopic stage II restorative proctectomy for toxic ulcerative colitis. Int J Med Robot, 2012. 8(2): p. 178–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Miller AT, et al. , Robotic-assisted proctectomy for inflammatory bowel disease: a case-matched comparison of laparoscopic and robotic technique. J Gastrointest Surg, 2012. 16(3): p. 587–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pedraza R, et al. , Robotic-assisted laparoscopic surgery for restorative proctocolectomy with ileal J pouch-anal anastomosis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol, 2011. 20(4): p. 234–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rencuzogullari A, et al. , Case-matched Comparison of Robotic Versus Laparoscopic Proctectomy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech, 2016. 26(3): p. e37–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mark-Christensen A, et al. , Short-term Outcome of Robot-assisted and Open IPAA: An Observational Single-center Study. Dis Colon Rectum, 2016. 59(3): p. 201–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Connell E and Burke JP, The role of transanal total mesorectal excision in inflammatory bowel disease surgery. Annals of Laparoscopic and Endoscopic Surgery, 2020. 5 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Coffey JC, et al. , Transanal total mesocolic excision (taTME) as part of ileoanal pouch formation in ulcerative colitis--first report of a case. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2016. 31(3): p. 735–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ambe PC, Zirngibl H, and Möslein G, Initial experience with taTME in patients undergoing laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy for familial adenomatous polyposis. Tech Coloproctol, 2017. 21(12): p. 971–974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Buisson A, et al. , Review article: the natural history of postoperative Crohn’s disease recurrence. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2012. 35(6): p. 625–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kono T, et al. , Kono-S Anastomosis for Surgical Prophylaxis of Anastomotic Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease: an International Multicenter Study. Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, 2016. 20(4): p. 783–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choy PY, et al. , Stapled versus handsewn methods for ileocolic anastomoses. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011(9): p. Cd004320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gajendran M, et al. , Ileocecal Anastomosis Type Significantly Influences Long-Term Functional Status, Quality of Life, and Healthcare Utilization in Postoperative Crohn’s Disease Patients Independent of Inflammation Recurrence. Am J Gastroenterol, 2018. 113(4): p. 576–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kono T, et al. , A new antimesenteric functional end-to-end handsewn anastomosis: surgical prevention of anastomotic recurrence in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum, 2011. 54(5): p. 586–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Luglio G and Kono T, Surgical Techniques and Risk of Postoperative Recurrence in CD: A Game Changer? Inflammatory intestinal diseases, 2021. 7(1): p. 21–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kono T, et al. , Kono-S Anastomosis for Surgical Prophylaxis of Anastomotic Recurrence in Crohn’s Disease: an International Multicenter Study. J Gastrointest Surg, 2016. 20(4): p. 783–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Luglio G and Kono T, Surgical Techniques and Risk of Postoperative Recurrence in CD: A Game Changer? Inflammatory Intestinal Diseases, 2021. 7: p. 1–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kredel L, Batra A, and Siegmund B, Role of fat and adipokines in intestinal inflammation. Curr Opin Gastroenterol, 2014. 30(6): p. 559–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Li Y, et al. , The Role of the Mesentery in Crohn’s Disease: The Contributions of Nerves, Vessels, Lymphatics, and Fat to the Pathogenesis and Disease Course. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2016. 22(6): p. 1483–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Coffey CJ, et al. , Inclusion of the Mesentery in Ileocolic Resection for Crohn’s Disease is Associated With Reduced Surgical Recurrence. J Crohns Colitis, 2018. 12(10): p. 1139–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tekkis PP, et al. , A comparison of segmental vs subtotal/total colectomy for colonic Crohn’s disease: a meta-analysis. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, 2006. 8(2): p. 82–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Angriman I, et al. , A systematic review of segmental vs subtotal colectomy and subtotal colectomy vs total proctocolectomy for colonic Crohn’s disease. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, 2017. 19(8): p. e279–e287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Martel P, et al. , Crohn’s colitis: experience with segmental resections; results in a series of 84 patients. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 2002. 194(4): p. 448–453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Fichera A, et al. , Long-term outcome of surgically treated Crohn’s colitis: a prospective study. Diseases of the colon and rectum, 2005. 48(5): p. 963–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Handler M, et al. , Clinical recurrence and re-resection rates after extensive vs. segmental colectomy in Crohn’s colitis: a retrospective cohort study. Techniques in coloproctology, 2016. 20(5): p. 287–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lightner AL, Segmental Resection versus Total Proctocolectomy for Crohn’s Colitis: What is the Best Operation in the Setting of Medically Refractory Disease or Dysplasia? Inflammatory bowel diseases, 2018. 24(3): p. 532–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kiran RP, et al. , The role of primary surgical procedure in maintaining intestinal continuity for patients with Crohn’s colitis. Annals of surgery, 2011. 253(6): p. 1130–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Neumann H, et al. , Cancer risk in IBD: how to diagnose and how to manage DALM and ALM. World J Gastroenterol, 2011. 17(27): p. 3184–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Buchner AM, Endoscopic Management of Complex Lesions in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y), 2021. 17(3): p. 121–127. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DeRoche TC, Xiao S-Y, and Liu X, Histological evaluation in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology Report, 2014. 2(3): p. 178–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gorfine SR, et al. , Dysplasia complicating chronic ulcerative colitis: is immediate colectomy warranted? Dis Colon Rectum, 2000. 43(11): p. 1575–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schwartz DA, et al. , The natural history of fistulizing Crohn’s disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology, 2002. 122(4): p. 875–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rojanasakul A, et al. , Total anal sphincter saving technique for fistula-in-ano; the ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract. J Med Assoc Thai, 2007. 90(3): p. 581–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wood T, et al. , Increasing experience with the LIFT procedure in Crohn’s disease patients with complex anal fistula. Tech Coloproctol, 2022. 26(3): p. 205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Meinero P and Mori L, Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT): a novel sphincter-saving procedure for treating complex anal fistulas. Techniques in coloproctology, 2011. 15(4): p. 417–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Siddique S, et al. , Outcomes in High Perianal Fistula Repair Using Video-Assisted Anal Fistula Treatment Compared With Seton Use: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Cureus, 2022. 14(2): p. e22166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Panés J, et al. , Expanded allogeneic adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (Cx601) for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: a phase 3 randomised, double-blind controlled trial. The Lancet, 2016. 388(10051): p. 1281–1290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kichloo A, et al. , Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Fam Med Community Health, 2020. 8(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Regueiro MD, et al. , The inflammatory bowel disease live interinstitutional and interdisciplinary videoconference education (IBD LIVE) series. Inflamm Bowel Dis, 2014. 20(10): p. 1687–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]