Abstract

Objectives

The efficient delivery of drugs from dry powder inhaler (DPI) formulations is associated with the complex interaction between the device design, drug formulations, and patient’s inspiratory forces. Several challenges such as limited emitted dose of drugs from the formulation, low and variable deposition of drugs into the deep lungs, are to be resolved for obtaining the efficiency in drug delivery from DPI formulations. The objective of this study is to review the current challenges of inhaled drug delivery technology and find a way to enhance the efficiency of drug delivery from DPIs.

Methods/Evidence acquisition

Using appropriate keywords and phrases as search terms, evidence was collected from the published articles following SciFinder, Web of Science, PubMed and Google Scholar databases.

Results

Successful lung drug delivery from DPIs is very challenging due to the complex anatomy of the lungs and requires an integrated strategy for particle technology, formulation design, device design, and patient inhalation force. New DPIs are still being developed with limited performance and future device design employs computer simulation and engineering technology to overcome the ongoing challenges. Many issues of drug formulation challenges and particle technology are concerning factors associated with drug dispersion from the DPIs into deep lungs.

Conclusion

This review article addressed the appropriate design of DPI devices and drug formulations aligned with the patient’s inhalation maneuver for efficient delivery of drugs from DPI formulations.

Keywords: DPI device design, Particle technology, Drug formulation, Lung deposition, Computational modelling

Introduction

Dry powder inhaler (DPI) technology is a delivery platform for either the local respiratory tract or systemic in the form of fine powders of drug. For a variety of reasons, DPI has advantages over nebulizers and pressurized metered dose inhalers (pMDI) as it does not need to syncronise between patients inspiratory force and device actuation. DPI is found to be appealing and effective in the treatment of some local lung disorders such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis (CF), and pulmonary tuberculosis by allowing drugs to be deposited directly to the target site, resulting in rapid drug action with reduced adverse effects. DPI is a probable candidate for parenteral administration replacement for vaccines, amino acid proteins, and peptide drugs [1]. DPIs technology have three major components such as drug formulation, the design of devices with metering system and the aerosol dispersion system. Deposition of pharmaceutical aerosols in the lungs is associated with the inspiratory force of the patients, design of the devices, and the drug formulations [2, 3]. There are many published articles demonstrated the DPI technologies, challenges and emerging trends in inhaled drug delivery systems for various applications [4–8], no comprehensive studies are available to explicitly focused on the combined challenges of particle technology, drug formulations, device characteristics and patients manuver for overcoming the ongoing problems and future platforms for significant clinical outcomes. The limited selections of suitable excipients in developing the formulations with low variability of drug deposition into lungs, cost-effectiveness, and poor performances of the inhalers are still challenging.

DPIs stand out as an effective method for lung drug delivery, offering several advantages. These devices facilitate the rapid administration of therapeutic agents directly to the lungs without the need for propellants, thereby minimizing the risk of microbial contamination. Additionally, DPIs ensure enhanced stability of medications in their solid form. Nonetheless, it is essential to consider the potential adverse effects associated with their long-term usage.

Here in this manuscript, we review the type of DPIs and the known fundamental mechanisms of drug delivery from different DPIs with different resistances (Sects. “The known knowledge and gaps in this area of research”, “Classifications of dry powder inhalers”, “Dry powder inhaler device resistances”, “Dry powder inhaler (DPI) technology”). Section “Opportunities and challenges in the design of high-performance DPIs” covers the opportunities and challenges associated with some existing DPI devices. The performance and limitations of the existing DPIs based on particle technology and formulation, device design, and patient’s inspiratory forces, are covered briefly in Sect. “Factors associated with the performance of the DPI”. Similarly, the details of the DPIs design with enhanced performance and future directions have been explained in Sect. “Design of DPIs with enhanced performance”. Section “Computational modelling” covers the computational modelling in developing the new devices suitable for all formulations. Section “The updated/new knowledge on this topic” highlights the updated/new knowledge on this topic. Finally, the overall conclusion of this review is presented in Sect. “Conclusions”.

The known knowledge and gaps in this area of research

The available known knowledge and limitations of inhaled drug formulation technology, the impact of device design on particle aerosolization, and the application of computational fluid dynamic technology have been elaborated throughout the manuscript. The development of high-dose DPIs is heavily dependent on advances in particle engineering, formulations, device design and patient inspiratory force associated with the severity of lung diseases such as asthma, COPD and CF. This area of coordinated research has not progressed yet. Very little is known about the drug interactions in formulations containing multiple active ingredients and their aerosolization via a universal device suitable for all types of patients including children who are a vast portion of consumers. Researchers have spent a significant amount of time developing smart formulations and device designs; however, the outcomes in terms of patient satisfaction with optimum therapeutic benefits have not been achieved. Regarding the formulation technology, the main objective is to diminish the cohesive properties of the particles, thereby significantly reducing inter-particulate interactions, and enhancing the aerosolization of particles from the devices. Additionally, it is critical to ensure that the powder remains stable and free from agglomeration in the devices during storage, preserving the efficacy and safety of the medication. Such efforts are aimed at improving powder dispersion and optimizing drug delivery to the lungs; however, the device design for patients with different degrees of lung disorders is still in its infancy and the following subsections detail the current information and subsequent future steps to overcome the ongoing challenges.

Classifications of dry powder inhalers

The design of DPI can be classified into three distinct categories, single-unit dose, multiple unit doses and multiple doses. The Spinhaler®, Rotahaler®, Inhalator®, and Cyclohaler® devices fall under the category of single-unit-dose delivery systems which make use of capsules to deliver medications. Diskhaler®, Ellipta®, and Accuhaler® are all examples of the second type, which is characterized by the utilization of multiple unit dose dispensing devices. The powdered medication is pre-filled in blister discs or blister strips, and then a device mechanism either punctures or peels the blisters off, delivering the medication dose by dose. Devices that hold different doses, such as the Turbuhaler®, Autohaler®, Easyhaler®, and NEXThaler®, are classified under the third category of DPI.

The drug powder in most DPIs is located in the middle of the devices between the inlet and the outlet of an airflow passage in which the patient draws in breaths of air. It may be challenging to generate a sufficient volume of air flow through the apparatus to entrain the medication and transport it into the patient’s lungs to the greatest extent possible[9]. The amount of medicines that reach the lower airways is partially determined by the degree of air turbulence that is generated through the device and the oral cavity [10, 11]. It is convenient to use capsule as the unit container in certain devices such as the Spinhaler®, Rotahaler®, Inhalator®, and Cyclohaler®. In most cases, this does not result in a significant loss of the medicine due to residual powder that is still present in the container after activation. On the other hand, both gelatin capsules and medicine have a tendency to hold onto moisture, which can be a challenge to the drug stability whereby making it more difficult to flow in powder form [12–14]. Therefore, the second generation of multiple unit dosing devices has been designed to tackle such challenges. These devices protect the medicine from degradation by moisture; however, some multiple doses have poor dose consistency.

Dry powder inhaler device resistances

There is a direct correlation between the pressure drop that occurs across the delivery devices with the device’s specific resistance [15]. It has been demonstrated that there is a linear relationship between the square root of the pressure drop and flow rate. There are various types of devices with varying degree of resistance are available on market. For example, Rotahaler® was found to be the lowest resistance followed by other devices like Spinhaler®, Cyclohaler®, Diskhaler®, Turbuhaler® and the Inhalator Ingelheim®[15]. For the new generation DPI devices, the inhalation resistances were listed in the following order; Twincaps® > Handihaler® > Swinghaler® = Clickhaler® > Twisthaler® > Turbuhaler® > Jenuair® > Diskus® > Ellipta® > Diskhaler® > Breezhaler® [16].

The Andersen cascade impactor and next generation impactor are two examples of apparatus that can be used in the laboratory to measure aerosol delivery efficiency of DPI devices. This is accomplished through the utilization of an apparatus that has been specifically designed for the aerodynamic assessment of fine particles through the process of inertial impaction. Additionally, it is anticipated that the fine particle fraction (FPF) of the medicine plays a key role in determining the extent to which the delivery efficiency is maximized. This proportion demonstrates the highest potential of drug deposit in the lower airways, a process that is dependent on a wide variety of factors such as properties of the powder formulation and inhaler device features.

As air is drawn through the inhaler device, the pressure drop occurs. This is a situation whereby the difference in static pressure is measured at two different sites inside a system. When compared to the same amount of inhaling effort, a lower inhalation flow rate is expected by an increase in flow resistance and a higher pressure drop. Consequently, a higher pressure drop in the device may occur from the narrow passage areas of the air flow which may also provide a significant effect on fine particle production for aerosolization. The sufficient shear stresses that act on the particles and high local turbulence leads to appropriate de-agglomeration of the powders for aerosolization. The inhalation of smaller-sized particles is promoted by high turbulence flow. The opposite effect was observed with the reduced inlet mouthpiece size and resulted in an increased particle velocity, which caused drug loss via inertial impaction. Similarly, a high turbulence airflow through the device can be produced by decreasing the diameter of the device inlet. Therefore, further investigation is required to optimise the device resistance.

Each DPI device has a suitable flow rate to generate optimal aerosolization drug particles. For example, flow rate of 30 L/min was reported to be suitable for high resistance devices such as the HandiHaler® and 60 L/min for the Turbuhaler®, while medium to low resistance devices includes 40 L/min Aerolizer® and 30 L/min Autohaler®, respectively [17] to generate aerosols for a wide range of patients. The high resistance DPIs are suitable for patients who are unable to produce high level inspiratory force during inhalation. The optimal flow can be represented in terms of device resistances and required minimum and optimum flow rate as shown in Eq. (1)[18].

| 1 |

where :

= required breathing power (W).

= the specific resistance of the device (mbar1/2 /L/min).

= minimum required flow rate (L/min).

The required breathing power can be used to match DPIs to the condition of the patient, for example, Spiromax® and Turbohaler® have the same device resistance of 0.11 mbar1/2/L/min but the required breathing power is 0.54 W and 4.36 W, respectively[18]. The device resistance, inspiratory pressures, and flow-rate relationship are explored by Clark et al. [9]. It was suggested that the device resistance influences patient’s ability to generate sufficient flow for efficient use of DPIs. Accordingly, it has been well established that devices with high resistance are suitable for patients with low inspiratory force due to severe asthma or COPD. Because of the device design with high resistance, deagglomeration and aerosolization of particles occurred at a low inspiratory flow.

Dry powder inhaler (DPI) technology

DPI technology is based on the drug formulations in powder form, which is dispersed from a device using a patient’s inhalation forces. The effectiveness of drug deposition relied on some crucial factors, including the inhalation force of the patient, dry powder formulation, and inhaler devices[19].

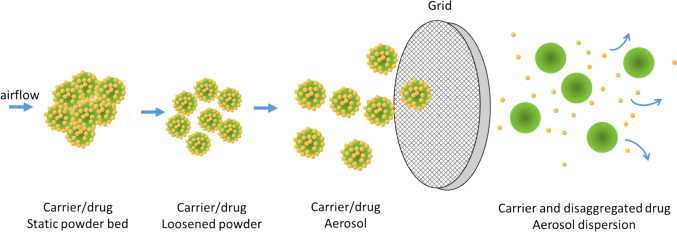

There are four fundamental principles of DPIs to facilitate the dispersion and deagglomeration of the medication powder which include the dose-metering mechanism (for multiple dose device), deagglomeration/aerosolization mechanism, and mouthpiece that directs the aerosol to the patient. During inhalation, the airflow disperses the drug powder and deagglomerates the power into fine particles; in many cases, the powder comprises the large lactose particle and fine drug particles (carrier-based formulations). The dispersed powder pass through a grid that assists the powder deagglomeration (Fig. 1). The fine drug particles will cross the respiratory tract while the large carrier particles are mostly deposited in the mouthpiece and patient’s oropharyngeal region[20, 21].

Fig. 1.

Mechanism of drug dispersion from dry powder inhaler (Redrawn from Tiano and Dalby [20])

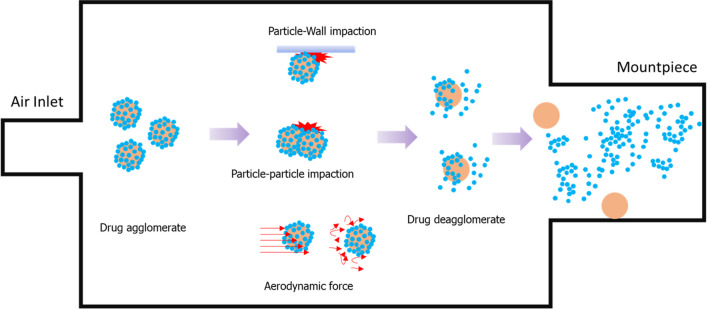

For optimal DPI delivery performance, the device’s design is one of the most important factors to consider. In general, the device must be able to provide a sufficient force that leads to the deagglomeration of the particles by air turbulence and mechanical impaction within the device (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mechanisms of dispersion of the powder as aerosol inside an inhaler (drug particle in blue, carrier particle in orange)

Interestingly, the impact that resulted from the device design was the device resistance, which was related to the inspiratory force. However, the high resistance of device provides a high degree of turbulent airflow inside the device, and caused aerosolization of powders at low flow rate. Therefore, the device should create a balance between the optimal resistance and the optimal turbulence of the airflow for efficient dispersion of powders during inhalation [15].

Opportunities and challenges in the design of high-performance DPIs

There are various types of devices with different designs with improved performances; however, the optimum performance is still far from the reality as the fine particle fractions of drugs from the currently available devices are still approximately 50%.

The capsule-based inhaler is still a good design of choice for a single unit dose system as it provides a good balance between device complexity and performance [22–24]. The challenging factor in this delivery design is the complete emission of the formulated powder out of the capsule. Hence, the most capsule-based device directs the airflow to spin, shake and vibrate the capsule in a longitudinal axis or transverse axis to assist the capsule emptying. The spinning action of the capsule is created by using a chamber with a tangential air inlet. This design creates a swirling airflow field and provides force to spin the capsule. For example, Breezhaler™ spins the capsule along the transverse axis of the capsule inside the circular chamber which results in the capsule spinning rapidly[25]. The centrifugal force assists the powder ejection from the pierced holes of the capsule. Moreover, the capsule can collide with the inhaler wall and facilitate the powder escaping from the capsule. Contradictory, the Turbospin®, PodHaler®, and ARCUS inhaler spin the capsule along its longitudinal axis [22, 26, 27]. In addition to spinning, the capsule is also shaken by the airflow flux. These actions allow the powder to be emitted and aerosolized. The advantage of these devices is that they have relatively low resistance and can produce consistence performance over a certain range of the inspiratory flow rate. However, the multiple steps of using these DPIs resulting more prone to patient errors. Thus, there is a design challenge to reduce the step of operating a capsule-based inhaler, for example, the active capsule piercing mechanism that is triggered by inhalation or piercing the capsule on the inhaler lid opens and closes resembled the Nexthaler®.

Recently, the delivery of single or multiple high drug doses through the pulmonary route has attracted much attention in the delivery of high-dose antibiotics. The challenge of delivering such a high amount of power is to retain the powder agglomerate in the de-agglomeration zone within the inhaler to expose the inspiratory airflow energy. The Twincer® and Cyclop® devices utilize the air classifier technology to overcome this limitation by implementing the principle of the cyclone separator [28–30]. For example, the impaction angle of the revolving powder in the classifier was lowered and air supply channels are increased in the Cyclop® device due to tobramycin, which tends to stick to the classifier wall. The difference in physicochemical properties of the two active ingredients combined in DPI also caused difficulty in the manufacturing process. The prospect to overcome this problem is to formulate the drug separately and deliver it using the inhaler device; however, still it is not the permanent solution.

Many DPI manufacturers offer active DPI systems that have the external energy supply to assist the powder deagglomeration. This type of DPI is useful for patients with limited breathing force such as pediatric, critically ill, and severe COPD or asthma patients. The aerosolisation energy of PuffHaler® and Exubera® is compressed air provided by a rubber bulb and user-operated air pump, respectively[31, 32]. The major limitation of this device was the bulkiness and high cost. Exubera® is an example of the bulkiness of the air pump results in poor patient acceptance and thus the manufacturing was discontinued. The MicroDose DPI and 3 M Taper™ DPI are much more compact [26, 33] with high velocity air pressure. The use of a mechanical impactor in 3 M Taper™ DPI reduces the cost of electronics and batteries[26].

Factors associated with the performance of the DPI

The efficient delivery of drugs from DPI formulations is associated with the complex nature of the respiratory tract, particle technology of the drug formulations, the design of device, and patients’ inspiratory forces [34, 35]. The deep lung delivery of drug particles from the drug formulations and delivery devices is the results of integrated performance of patients, formulations and device design [36]. There are several challenges which limits to the emitted dose of drugs from the formulation, low and variable deposition of drugs into the deep lungs, and maximum drug deposition in the upper airways of the respiratory tract such as oropharynx region [6, 37]. There is a big gap between clinical practice and DPI formulations for efficient delivery of appropriate dose of drugs from the formulations. To date a large number of DPI devices are available and some are under development for clinical applications; however, no individual devices have been identified as an ideal inhaler for a wide range of patients. The drug deposition from the DPI formulations is variable and extent of dose variability depends on the complex formulations, the device design, and the patient’s inhalation maneuver depending on the conditions of lungs. An appropriate dosing of the drug from the DPI formulations is somehow inadequate and that results in limited therapeutic benefits of the currently available DPI products. Therefore, the successful development of this drug delivery technology is very challenging. Although most of the time we concentrate on the development of efficient drug formulations and new devices with optimum performances, appropriate patient training always remains behind the scenario of maximizing the treatment outcomes. Therefore, appropriate patient training for using their devices should be incorporated in minimizing the ongoing challenges.

Particle technology and Formulation factor

Particle technology

The particle technology for the development of powder formulation is important as the physicochemical properties of drug particles and excipients are associated with the efficiency of drug dispersion. In order to get efficient lung deposition, the aerodynamic diameter of the inhalable particles must be less than 5 µm[38]; however, particles < 3 µm showed strong correlation with appropriate pulmonary drug deposition [39]. Inhalable particles less than 5 are highly cohesive and have very poor flow property. Having said this, the micronized particles are likely to agglomerate. To overcome these problems, inhalable drug particles are mixed with large carrier lactose, which enhances the flow property of the formulations[40]. Upon inhalation, airflow through the device generates shear and turbulence, which help aerosolize the powder formulations and impact on the mesh/grid in the device from where drug particles are dispersed by deagglomerating the fine drug agglomerates or detaching fine drug particles from the surface of large carriers and finally deposited into the lower airway of lungs. The successful deposition of drug particles from the formulations is not possible if the deagglomeration of the agglomerates and detachment of drug particles from the large carrier surface are not occurred [41, 42]. Thus, effective dispersion of drug particles from the formulation depends on the physicochemical properties of the particles such as particle morphology[43, 44], particle size, shape, surface area, density, and adhesion/cohesion forces[42, 45].

Particles with different shapes experience varying drag forces and terminal velocities, which significantly influence drug particle aerosolization and deposition into deep lungs [46–48]. The specific shape of carriers has an influence in controlling drug aerosolization and lung dispersion. The interaction forces between drug particles and carrier surfaces, and the flow properties of the formulation are also affected by the particle’s shapes of drugs and carriers [49, 50]. For example, the elongated particles of lactose carriers produced increased FPF, fine particle dose and dispersibility of salbutamol sulphate [51, 52]. It was suggested by the authors that the elongated shape of particles might exhibit a much smaller aerodynamic diameter than that of spherical particles with similar mass or volume. Recent studies employing computational fluid dynamics alongside the discrete element method (DEM) uncovered that elongated-shaped particles demonstrate significantly increased deposition rates within the device, especially in the chamber and mouthpiece sections of the Turbuhaler® device, in contrast to spherical particles [53]. They suggested that elongated particles, due to their greater flat contact area with the device wall, experienced a higher van der Waals attraction force compared to that acting on spherical particles.

Particle surface charge is another controlling factor of drug dispersion from the DPI devices. The electrostatic interactions among particles or internal surface of the devices are crucial for disrupting drug-carrier detachment or deagglomeration of drug-drug agglomerates and aerosolization of drugs into lungs [54, 55]. Excessive opposing charges might produce high adhesive forces that caused poor drug aerosolization and deposition into deep lungs. The addition of surface force controlling agents like magnesium stearate and leucine minimizes the surface charge. Therefore, minimization of particle charges and their interactions in the formulation as well as the internal surfaces of the device need to be ensured.

Therefore, the advances of DPI formulation have been focused on enhancing particle aerosolization by controlling particle size, shape, density and surface energy [6], addition of carrier and excipients [40, 56–58]. Although many articles dedicated to the particle technology for the development of optimized DPI formulations, have been published; however, the drug dispersion into deep lungs from the currently available formulations is still limited. To improve the efficiency of DPI products, various types of engineered particles have been prepared by freeze drying, spray freeze drying and supercritical fluid techniques [6, 56, 59]. The prepared engineered particles are physically and chemically stable in the formulation containing various types of excipients characterized by different techniques [58, 60]. Recently, engineered nanoparticles of various drug loaded polymers for lung delivery against cancer, respiratory tract infections [61, 62], and many other systemic disorders [56, 59, 63–68] have been investigated; however, no products have come to the market as the in-vitro and in-vivo models [69, 70] have not been well established.

Although the inhaled particles prepared by milling, spray drying, spray freeze drying, supercritical fluid and aerogel methods as demonstrated in Table 1, still the lung delivery of drugs form the DPI formulations are not maximum. The inhalable particles produced by milling process are highly cohesive owing to the high surface energy that leads to reduced particle flow. Spray dried particles are mostly amorphous with limited stability and require extra treatment for maximizing stability. Supercritical fluid technology is limited to laboratory scale production of particles. Further details of these technologies are demonstrated elsewhere [59, 60, 71].

Table 1.

Particle technology used in preparing the DPI formulations

| Technology | Drugs used | Outcomes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Milling |

Beclomethasone dipropionate (BDP); Diclofenac (DF), diclofenac sodium (DFNa) Ibuprofen with leucine and magnesium stearate |

BDP milled with lactose and magnesium stearate produced less aerosol performance; DF produced better aerosol performance than DFNa Wet milled ibuprofen particles produced higher FPF than of dry milled powders |

[72–75] |

| Spray drying (SD) | meloxicam and meloxicam potassium salt; Paclitaxel (PTX) loaded bovine serum albumin; Tobramycin with and without sodium stearate; Salbutamol sulfate | Carrier based DPI formulation decreased progression of CF and COPD Promising flow property with significant antitumor activity; improved antibacterial activity to CF patients; Co-spray dried drug with carrier (mannitol-lactose) improve aerosolization performance | [76–81] |

| Spray freeze drying (SFD) | Voriconazole; Theophylline-oxalic acid cocrystal; Insulin | Porous voriconazole showed good aerosol property and lung deposition; Stable crystal of theophylline suitable for DPI formulations; inhaled liposomal insulin particle produced successful hypoglycaemic activity for longer period of time | [82–85] |

| Supercritical fluid technology (SCF) | Insulin; Celecoxib-PLGA; | Inhaled insulin loaded poly-L-lactic porous microspheres pronounced hypoglycemic activity in diabetic rat model; Celecoxib loaded PLGA microparticles showed sustained drug release and promising efficacy against cancer cells, with insignificant toxic effects | [42, 86, 87] |

| Aerogel (assisted with SCF technology) | Naproxen loaded alginate and alginate–hyaluronic acid microspheres; Salbutamol loaded chitosan aerogel microspheres | Alginate-Chitosan Aerogel showed less toxicity in lung cells; Alginate and alginate-hyaluronic acid aerogel microspheres found suitable for lung drug delivery; very good, sustained salbutamol release from the microspheres | [88–91] |

| Electrospraying | Montelukast and budesonide | Montelukast served as a carrier for budesonide and improved the aerosolization behavior and dissolution rate of budesonide | [92] |

Pulmonary infectious diseases especially the lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) are one of the major health problems and this have a bright opportunity for inhaled drug therapy [93, 94]. Currently, only tobramycin (TobiPodhaler™) DPI is available for the treatment of lung infection[95, 96] and there is a high demand in the inhaled delivery of large dose antibiotics; however, it does come with some challenges such as the use of excipients needs to be minimized to limit the powder mass to be delivered into lungs for therapeutic benefits. To achieve this, a new technology is paramount so that drug particles can be prepared with the minimum amount of excipients. Finally, by integrating the device design, particle technology and patient’s inhalation maneuver, it is possible to adopt sophisticated technological approaches to resolve the ongoing challenges and enhance the pulmonary drug delivery from DPI formulations [23]. Therefore, further studies are required to develop robust particle technology to resolve the ongoing challenges with the currently available systems. Details of some particle technologies for developing DPI formulation are summarized in Table 1.

Additionally, most patients, which involve both children and elderly with dexterity, are unable to perform this experiment effectively, which has been a challenge for those patient group who get benefits from the system. Appropriate particle engineering is essential to achieve enhanced lung deposition of drug particles from a well-designed DPI device. The proper design of delivery devices can improve the deagglomeration of drug agglomerates with enhanced dispersion.

Formulation factor

The two basic dry powder inhalation formulations are soft agglomerates and adhesive mixtures. The agglomerates are suitable for high dose drugs whereas the low dose drug is usually prepared as adhesive mixture with carrier. Such low dose micronized drug mixed with coarse carrier as ordered mixture. Other technology emerging from coarse carrier like carrier blend between coarse and fine carrier, dry powder coating, carrier surface modification, force controlling agent and particle engineering. Particle engineering in dry powder for inhalation by spray dried low density porous particles in Pulmosphere technology, proliposome and micelle formulations, solid lipid nanoparticles and nanocrystal, these types of formulation will convert to nanoparticle when contact with biological fluids [97]. Coating technology will also modify the interacting surface of carrier. This will lead to modify strength of drug carrier interaction. The alteration depends on coating agent. Particle replicate on non-wetting template (PRINT) may be able a choice in the near future of producing a uniform carrier. PRINT is a soft lithography producing uniform and identical particles of various size and shape and chemical compositions. The molds made from Teflon are non-adhesive using customized micro- nanosized can be manufactured [98].

To address the inherent challenges in high-dose DPIs, a variety of particle surface modification techniques have been employed. Advanced particle engineering technologies, such as micronisation, in tandem with co-processing techniques that enhance the surface properties of particles using minimal excipients, have proven effective. In particular, porous particles, such as aerogel powders, are nanostructured particles that present significant potential for surface modification. Their large surface area, superior aerodynamic qualities, and robust fluid uptake capacity make them ideal candidates for this purpose [99].

Recent advancements in powder technology, including the use of porous carriers, have been thoroughly reviewed. The research on high-dose DPI has been considerably expanded, with several drugs gaining recent regulatory approval as a direct result of these research efforts. Innovative strategies for surface modification tailored to high-dose dry powder inhalers have been compiled and are instrumental in this progress [100, 101]. The employment of various force control agents, such as leucine, magnesium stearate, and sodium stearate, alongside diverse manufacturing methods, has been pivotal in overcoming the obstacles associated with high-dose DPI formulations.

Device factors

The DPI devices developed so far are mostly passive or breath activated and thus, require a forceful and deep inhalation to disperse drug particles from the formulations. Different devices with different resistance require appropriate inhalation force from the patients. However, many patients including children and elderly with impaired lung function usually face challenges in creating appropriate inhalation force that is required for dispersing drug particles from the formulations. To avoid this limitation of passive DPIs, external energy from battery is required to activate DPIs, which has been developed to operate as electrical vibration, compressed air or mechanical impellers to disperse the drug from the formulation. [102–104]. Due to the presence of energy source, active devices enable patients inhaled drugs with limited inspiratory force; however, none of them has reached the market because of their high cost and limited portability. The drawbacks of currently available DPIs are limited aerosolization performance, high variability, and low lung deposition [4, 105]. These drawbacks are associated with the micronized particle interactions in the formulation and inefficient device design, which may affect the powder deagglomeration or dispersion. Appropriate particle engineering is essential to achieve an enhanced lung deposition of drug particles from a well-designed DPI device. Therefore, in developing future DPI products, it is important to adopt a better technological approaches to resolve the ongoing challenges, thus, will enhance the pulmonary drug delivery from DPI formulations through integrating the device design, particle technology and patient’s inhalation [23].

Patients Inspiratory force

The inspiratory force of the patients is one of the most critical factors that influence particle deposition into deep lungs form DPI formulations. Inspiratory flow affects drug aerosolization and subsequent deposition into deep lungs for clinical benefits. To ensure effective lung drug deposition from DPIs, a certain level of inspiratory force from the patients is required to produce an appropriate flow rate through the device and deagglomerate which disperses the drug particles from the devices with different resistance. Patients with impaired lung functions due to severe asthma or COPD or age, are unable to produce the required inspiratory force to aerosolize drug particles from the devices. The selection of appropriate DPI for specific patients is essential. Health care professionals need to be careful about selecting the appropriate device following considering the patients lung function, dexterity, and inspiratory flow [106, 107].

Design of DPIs with enhanced performance

In most cases, the powder used in DPI is micronized with high surface energy, which is difficult to dislodge from the agglomerate. A critical function of an inhaler device is to regulate the patient’s airflow within the device, thereby providing dispersion forces sufficient to overcome the inter-particulate force. While much research has been focused on formulations previously, there is an increasing need to understand and enhance device design. Inhaler design modifications and developments can aid in increasing powder aerosolization and patient adherence [108].

Design modification for passive devices

The optimization of the passive DPI device to enhance its performance can be done in two ways, which include enhancement of powder deagglomeration through the turbulence and particle impaction as well as the modification of outlet flow pattern to minimize the mount-throat deposition loss. The enhancement of turbulence and particle impaction could be implemented using grid structure, swirling chamber, simple baffle, or rods array [109–111]. The modification of the mouthpiece with an auxiliary inlet increases aerosol plume spray angle while the spiral channel and mixing chamber result in uniform dispersion of particles in the radial direction. This modification can be applied for drug targeting to the specific regions of the peripheral airways [110, 111].

Many DPI devices implement air classifier technology, which is based on the cyclone separator design to improve drug de-agglomeration. The air classifier classified particles based on aerodynamic equivalence size. The large particles remain in the inhaler longer than the smaller particles. The large particles which are usually the drug-carrier agglomerate have more opportunity to expose the force inside the device while, smaller drug particles freely travel to the mouthpiece. Some devices that use air classifiers include Novolizer®, Twincer™, and Cyclops™ [29, 112–115]. The principle of the cyclone separator is also implemented in the 3 M Conix™ device where the cyclone part of the device is a close-end cyclone. This design emits fewer large carrier particles and significantly enhances FPF when compared to the Accuhaler™ [116]. Unfortunately, some modifications do not show adequate improved performance as demonstrated in the grid mesh modification of Clickhaler® with budesonide and salbutamol sulfate powder. The grid mesh structure showed improvement only in FPF. The mount piece spacer plays many roles in reducing drug deposition in the oropharyngeal mode [109].

The resQhaler™ incorporates airflow mesh vibration to assist powder dispersion called ActiveMesh™ technology. The vibration motion of the mesh behaves like sieving the powder through the mesh holes and deagglomerating the powder. However, the mesh vibration amplitude is directly derived from the inhalation force; the performance of the mesh may diminish at a low flow rate [116].

Design of active devices

The active device is designed to overcome the airflow-dependent performance of many passive devices. External energy, such as compressed air, piezoelectric vibration, and heat, is provided to assist the dispersion. Though many advantages of active devices, it still has many drawbacks such as higher costs and reduced portability[1]. A multi-dose active device that uses compressed air to deliver microdoses of medication is developed by Zhang et. al. [117]. The de-aggregation and aerosolization forces are supplied by the piezoelectric vibrator system in the MicroDose DPI. When the device is activated via inhalation, a piezoelectric transducer integrated inside the device generates a high-frequency vibration that aerosolizes medication powder in the blister. Staccato® device that had been described in the previous section is another example of an active device. This method was effectively utilized to administer fentanyl, demonstrating high bioavailability without the presence of thermal degradation products of fentanyl in patients’ plasma [118].

The exploration of another heat-assisted aerosolization through electronic cigarette platforms (vaping drug delivery systems) has been conducted. This approach managed to achieve a dose equivalence of terbutaline comparable to those delivered by jet nebulizers and DPIs. Nonetheless, there were notable limitations, including the need for formulation optimization specific to vaping technology, and the incompatibility of heat-sensitive drugs with this delivery platform [119]. Despite the superior aerosol dispersion capabilities of these active devices, the overall efficiency of the DPI system also depends on patient inhalation patterns.

Future directions in DPI device design

Despite many advancements in active device design, the passive device is still preferred among physicians and patients as it is effective and costs less than the active device. High drug doses, delivery of complex molecules such as protein and peptide, and personalized DPI design for special populations are increasing interest. Delivery of high-dose antibiotics of more than 100 mg is a challenge due to the large amounts of powder that may affect the device portability, powder dispersion difficulties, and patient compliance. One important issue that had to be resolved is minimizing the deposition of high dose of the drugs in the oropharynx, which can cause considerable adverse effects, including upper respiratory tract irritation. Recent efforts to combine antimicrobial peptides with isoniazid have demonstrated promising results in both aerosolization performance and antibacterial effectiveness against multi-drug resistant clinical strains Mycobacterium tuberculosis [120]. DPI design for special populations such as pediatric, critically ill, and elderly patients is another critical challenge. They have limited inhalation force or cannot correctly use effective inhalation techniques to operate the DPI device. This problem may be solved by using an active DPI device that has an external force to aerosolize the medication powder. Tang et al. have come up with an innovative DPI system that may be used on patients who are being incubated with the assistance of a breathing bag [121].

Several generations of DPI have incorporated a swirling airflow design to improve deagglomeration efficiency by increasing particle impaction and turbulent kinetic energy. A key aspect of this design is the inclusion of a grid at the mouthpiece outlet, which serves to minimize turbulence and reduce drug loss in the upper respiratory tract. Traditionally, these swirling flow designs have utilized a constant geometry tangential air inlet to generate the swirling effect, a method that has been shown to enhance deagglomeration efficiency in terms of FPF and MMAD. Recent studies have investigated the application of varied geometry cross-sections and honeycomb grids, resulting in enhanced aerosol performance [122]. The introduction of a counter-swirling flow design, featuring dual layers of multiple tangential inlets arranged in opposing directions, has been effective in reducing drug loss at the USP induction port and the pre-separator of next-generation impactors. This design leads to a more confine aerosol plume at the mouthpiece outlet compared to devices utilizing a single swirling flow, thereby minimizing drug loss in the oropharyngeal region [123].

The swirling flow design also impacts powder movement within the capsule of inline capsule-based DPIs. Integrating a capillary inlet equipped with a spiral vane alongside a capillary outlet enhances the swirling flow and turbulent kinetic energy inside the capsule. This configuration aids in the dispersion of the powder, thereby increasing the emitted dose. [124] Further evidence indicates that swirling flow enhances the aerosolization process in capsule-based devices using carrier-based formulations, with efficacy significantly influenced by the flow rate [125]. In addition, Air-Jet DPI is developed to deliver pharmaceutical aerosol to infants. The positive pressure air source, such as compressed air or a large bore syringe provided the required energy for aerosolization. The air volume is controlled by a miniature electronic controlled solenoid valve or spring-piston air reservoir chamber and 3-ways valve. The lung delivery efficiency is about 54% [126, 127]. Bass and Longest addressed the problem of air-jet DPI in children by using computational fluid dynamic to design the patient interface for either mouth-throat or nose-throat routes. The optimal design of mouthpiece interface was a wide expansion inlet with rod array 343 configuration tapered to the elliptical outlet. The extrathoracic drug loss had been reduced by approximately 5% [128].

Reloadable or reusable inhalers are frequently used medicines’ most demandable or favorable devices. Most capsule-based DPIs available belong to this group [129]. However, the trend is shifting to blister strip-based multiple-unit doses. High-dose antimicrobials, peptides, proteins, vaccines, and other single-dose active components have increased DPI delivery. Therefore, disposable devices are explicitly developed for short-term DPI treatments. A notable instance of an innovative high-dose DPI designed for a specific demographic is the Air-Jet DPI, which features a passive cyclic loading mechanism. Aimed at administering high-dose EEG formulations nasally to preterm infants, this device demonstrates the ability to achieve an estimated lung delivery efficiency of over 60% for a prototype spray-dried formulation. Remarkably, its performance shows minimal sensitivity to variations in powder mass within the 10–30 mg range, and it possesses the scalability needed to administer significantly larger doses [130, 131]. The novel particle engineering method beyond spherical particles such as planar, fold and fiber-like particles can be used for lung deposition control and enhance DPI efficiency [132, 133].

Further investigation into the optimal conditions for heat-assisted aerosolization, including temperature control, timing, and drug formulation compatibility, will be crucial. Additionally, developing devices capable of precisely controlling heat application during the aerosolization process will be a key to harnessing the potential of this technology. New formulations that can withstand the heat of aerosolization without degradation could open doors for a wide range of drugs to be delivered via this technology. This innovative approach could significantly impact pulmonary drug delivery, offering a new avenue for enhancing efficacy and patient experiences of the inhaled products[134].

Digitally monitored DPIs are developed as they provide both therapeutics and diagnostic functions at the same time. Digital DPIs allow disease conditions and patient compliance data, which doctors collect and review to adjust further treatment plans. These devices include Enerzair Breezhaler™, ProAir® Digihaler™, Diskus Adherence Logger, and Smart Turbuhaler® [25]. These digital devices offer acceptable accuracy in measuring spirometry parameters, such as peak inspiratory flow rate and inhalation volume [135]. They can provide cost savings in the long term by optimizing medication adherence in patients with difficult-to-treat asthma [136]. However, there are some concerns regarding the long-term cost-effectiveness of these devices in the general outpatient population.

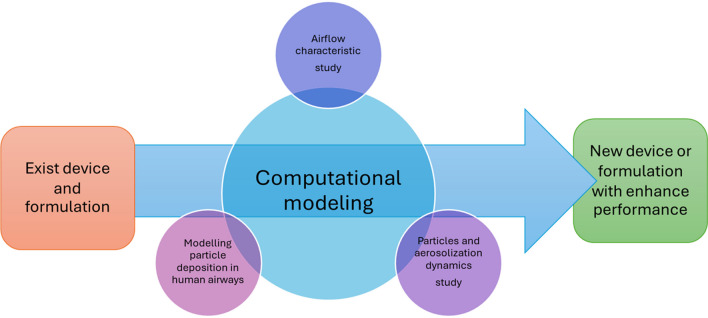

Computational modelling

The exponential growth of computational technologies has unlocked new possibilities for the computer-aided design of inhaler devices. Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) has been extensively utilized to explore airflow profiles and, to a somewhat lesser degree, the movement of particles in various inhaler types. CFD modelling employs a numerical method for analyzing and addressing fluid flow issues, adhering to the laws of mass and momentum conservation. These equations can be resolved through either coupled or segregated approaches, facilitating the determination of velocity and pressure fields, among other valuable parameters. The pioneering application of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) to study the Aerolizer® and Rotahaler® DPIs was undertaken by Coates et al. [137]. They discovered that the inhaler’s grid played a crucial role in achieving high performance in inhaler designs. This finding prompted increased focus from other research groups on employing CFD methodologies in the development of DPIs. Computational modelling of DPIs has been emphasized across various domains, including the analysis of commercial DPIs, investigation of specific device features, exploration of agglomerate breakup mechanisms, examination of DPI formulations, analysis of the impact of device and patient factors on particle deposition patterns, and the design of new DPI models (Fig. 3) [138].

Fig. 3.

The roles of computational modelling in developing of DPI systems

Analysis of commercial DPIs, DPI device features and agglomerate breakup mechanism

Tong et.al. [139] explored the impact of the carrier-drug mass ratio on aerosolization mechanics within the Aerolizer® and its cross-grid variant through a combined CFD-DEM analysis. They employed a range of lactose carrier to salbutamol sulfate ratios, from pure salbutamol sulfate up to a 200:1 mix, as their model drug system. Simulations of carrier particle dynamics were performed for both the standard and cross-grid configurations of the inhaler-throat models. The findings from both experimental and simulation data revealed significant differences between the original and cross-grid designs when utilizing pure drug formulations, whereas such differences were not observed with the carrier-based systems. The simulation results further demonstrated that drug loading increases did not affect FPFs until surpassing a specific threshold.

In addition to the grid design, the mouthpiece design was also studied. Research compares aerosolization performance of original ACTIVAIR™ (KOREA UNITED PHARM. INC., Korea) DPIs with a modified spiral mouthpiece design of the same inhaler device. The numerical calculation was performed and confirmed with particle image velocimetry and Andersen cascade impactor data. The CFD results showed that the non-spiral device demonstrated a high degree of linear motion in the middle, which resulted in the formation of a vortex on the side during the initial stage of airflow. The spiral mouthpiece demonstrated the development of radial velocity as a result of the swirling motion of the air flow exiting the spiral channel. Regardless of the air flow rate, the spiral mouthpiece provided more consistent particle velocity and swirl flow. This was crucial since the flow rate between patients may vary. It was confirmed by the cascade impactor data. The spiral device had a lower MMAD and a higher FPF percentage than the standard device. In this case, the spiral mouthpiece will undoubtedly improve the DPI’s effectiveness in terms of drug particle dispersion, allowing for a more constant dosage distribution [140].

The particle–wall collision energy was one of the predominant factors during the aerosolization process of the carrier DPI system. The micro-scale simulation at the carrier-API agglomerate level was conducted by Ariane et al. [141]. They investigated the effect of angle of impact, angular and impact velocity on the particle detachment using the DEM. Many simulation parameters were varied including the translational velocity from 1 m s−1 to 20 ms−1, angles of impact between 5° to 90, and the angular velocity between − 1 × 105 rad s−1 and 1 × 10 rad s−1. It was found that increasing impact angle rapidly increased the dispersion ratios towards a maximum value, especially above impact angles of 20°. As one may expect, increasing the impact velocity results in a greater dispersion ratio. The rotation of agglomerate was also important under a certain condition that the rotational kinetic energy was less than the energy from the translational velocity.

The capsule’s effect has been extensively explored. Aerolizer® capsule motion was studied using numerical simulation and a high-speed camera at various flow rates ranging from 30 to 100 L/min. This study made several noteworthy discoveries. For CFD simulation, the high-speed camera revealed the capsule’s fundamental motion. Between 500 and 3700 revolutions per minute, the capsule rolled predominantly in one direction around its longitudinal axis. Frequently, the capsule in the swirl chamber collided with the inhaler wall at speeds of up to 3 m/s, shaking the powder off the walls. By inducing whirling air flow around the capsule, the capsule altered the air flow field. The air flow entered the capsule’s pierce holes at a rate of up to 10 m/s, depending on the capsule orientation. This enabled the calculation of forces acting on the particles contained within the capsule by combining gravity and the centrifugal force generated by the capsule's spinning. The effect of these forces varied according to the particle’s size and location within the capsule. For example, the aerodynamic and centrifugal forces are approximately equal for a spherical 175 μm carrier particle near the capsule hole when the air velocity reaches approximately 30 m/s. Fluid drag was likewise the dominant force in the capsule’s interior for particles smaller than about 100 m. However, the aerodynamic force was negligible for large carrier particles located in the capsule’s interior [142]. Moreover, the distribution of powder in the capsule was heavily relied on initial phase of inhalation and angular capsule position. The particles escaped from the capsule were carrier particle clusters which contributed to the inhaler retention [143].

Longest et al. [144] developed a capsule-based unit dosage DPI device, as well as aerosolization and confinement techniques for the dose (DAC). The inhaler is operated by air flow along the capsule’s longitudinal axis through two pierce holes on each of the size 0 capsule tips. CFD simulations were performed using a low Reynolds number k–ω turbulence model in combination with particle tracking. As a model drug, salbutamol sulfate was employed. Numerous elements were considered and included in the design process. They conclude that the flow and particle parameters such as average particle specific dissipation rate, particle turbulent kinetic energy, specific dissipation rate of the flow field, the turbulent kinetic energy of the flow field, and wall shear stress from numerical simulation were very useful for optimizing inhaler devices to crate high-efficiency DPIs. The DAC device was further investigated with realistic mouth-throat by [145] The effects of piercing aperture location, reservoir length and inhaler inlet flow rate on emitted dose and particles deposition were evaluated. They suggested that the offset between the inlet and outlet orifice and the high flow rate increased emitted dose. The reservoir inside the DPIs device provides an area for the strong jet at the DAC unit’s outlet to relax and disseminated, resulting in improved delivery efficiency of in the mouth and throat. The higher deposition in the mouth and throat correlated to the larger particle size and higher inhalation flow rate.

DPIs particles residual in a device was a factor impairing the performance of DPIs. The particles could adhere to the device wall or capsule wall in capsule-based DPI. CFD-DEM modeling was utilized to study the fluid and particle behaviors in the device’s capsule while taking into account adhesive forces between particles and the particle-capsule wall. The computational modeling and experiment were performed at a flow rate of 28.3 L/min with Jethaler® device and 4.77 ± 2.0 μm mannitol in No. 2 HPMC capsule as a model drug. The contact force between particle–particle and particle–wall were simulated with Hertz–Mindlin contact model. The particles in the capsule were discovered to be accompanied by the high-velocity flow near the center of the capsule, resulting in multiple collisions between the particles and the capsule walls on the air outlet side. Conversely, turbulent kinetic energy was large at the air inlet side, and particle impact with the capsule wall was negligible. Thus, the capsule was modified with two holes at the outlet side resulting in most particles being emitted [146]. The drug particle detachment from the carrier particle mechanism was also observed by applying Lattice–Boltzmann method. The significant finding was that particle detachment from rough surfaces might occur by lift-off, sliding, or rolling. The effect drags and lift does not scale very well with respect to the contact distance. Rolling detachment, on the other hand, corresponded extremely strongly with asperity contact distance. However, particles on a rough structure were most likely dislodged by sliding rather than rolling especially at a high Reynolds number [147].

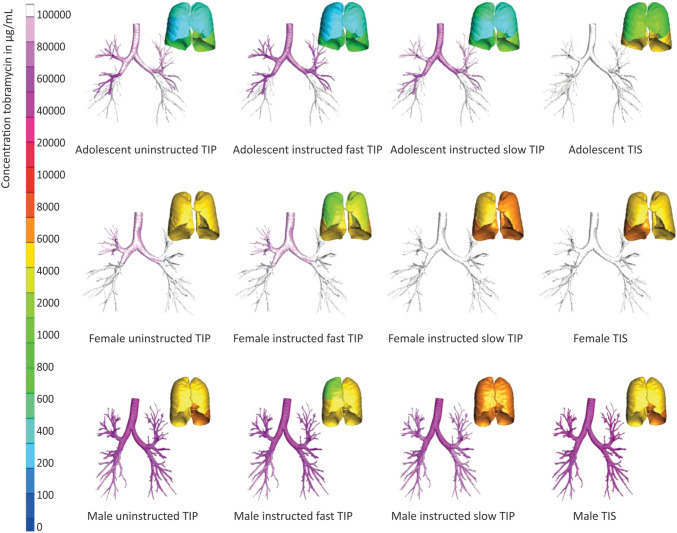

Modelling device with patient factor

The patient factor also affected the particle deposition pattern in the airways especially the head position of the patient. The physiologically realistic mouth-throat geometries under three positions head-straight, head-up and head-left) were scanned using MRI and were used as a CFD geometries model. The three different angle positions of an inhaler mouthpiece and the lips were emulated (i.e. 0°, 15°, 30°). It was discovered that head posture has little effect on particle deposition in the oropharyngeal region. Whereas the inhaler mouthpiece angle greatly increased the drug loss in the oropharyngeal region, especially 15 o -orientation at a low flow rate. The inlet direction affects the flow field of flow field structures in the mouth area, which affects the particle trajectory. A direct inertial impact was found near the symmetry plane of the mouthpiece and oral cavity due to strong jet flow. However, the deposition far from the symmetrical plane was an effect of centrifugal inertial impaction. This experiment implied that next-generation inhalers should integrate some elements that force the users to hold the inhaler at the appropriate orientation angle [10]. Besides head and mouthpiece orientation, the inhalation pattern was an important factor affecting the particle deposition in the airways passage. The airways model was obtained from medical imaging (CT scan). The numerical simulation of inhalation was performed at the flow rates of 28.3 and 60.0 L/min which resembled the inhalation conditions in patients with bronchial asthma and healthy subjects, respectively. The effect of breath holding was investigated compared to the steady flow condition. Many of the inhaled particles were deposited in the airways following the breath holding during inhalation whereas the majority were deposited in the mouth/throat area following exhalation without breath holding. The turbulence generated by breath holding facilitated particle deposition in the airways. Thus, one of the most critical aspects affecting the therapeutic impact of formulations is breath holding [148]. In addition to breath holding, the inspiratory flows of patients strongly affected the DPIs performance. A study on cystic fibrosis (CF) patients’ inspiratory maneuvers on lung deposition of tobramycin inhalation powder were conducted using CFD. The airflow profile was recorded at the patient’s home using an inhalation profile recorder. The inhalation profile was split into three groups including instructed slow inhalation, uninstructed inhalation and instructed fast inhalations. The 3D lungs models were obtained from chest CT scans of patients with CF. The CFD analysis demonstrated that instructed slow inhalation of tobramycin inhalation powder resulted in significantly higher tobramycin concentrations in our models’ large and small airways when compared to uninstructed inhalation or instructed fast inhalation, especially in male patients as shown in Fig. 4 [149].

Fig. 4.

The calculated concentrations of tobramycin across the bronchial tree for three types of inhalations—uninstructed, instructed fast, and instructed slow—during tobramycin inhalation powder (TIP) and tobramycin inhalation solution inhalation sessions, based on three single-study participants and three out of the nine CT models examined [149]

Modelling particle deposition in human airways

Numerical simulations of particle deposition in human airways may be used to target inhaled aerosol to a specific region of the lung [150]. used CFD to precise target aerosol to children’s upper airways. They employed a simple but morphometrically accurate upper airway model of the human lung at various ages. Variable factors included tidal volume, PIFR, and total inspiration time as a function of age (5, 10, and 25 years old). The CFD simulation revealed that at younger ages, the input velocity and flow velocity near the larynx was greater. Turbulence also occurred in the larynx for all age groups with varying degrees of severity. The Stokes number was used to quantify the effectiveness of particle deposition (Stk). For all age groups, particle deposition was found to be fitted by a single curve as a function of Stk. To specifically target the upper airways, particles with a Stk of 0.06 deposited roughly 80 percent in the conducting airways. [128] addressed the problem of air-jet DPI in children. They used CFD to design patient interfaces of air-jet DPI for either mouth-throat or nose-throat routes. The goal of their design was to minimize extra thoracic drug loss due to inertial impaction from high velocity jet flow from air-jet DPIs. The patient interfaces featured several design variants including undulating surface, step volume expansion, rod array and teardrop baffle, and cylindrical expansion. The model of air-jet DPIs, patient interface, nose throat and mouth throat region of the 5–6-year-old patient was created, and numerical simulation was performed at 13.3 LPM air flow. The numerical model was a low-Reynolds number (LRN) k-ω turbulence model. The best mouthpiece interface design was the design with wide expansion tapped to the outlet with rod array 343 configuration close to the capillary inlet. It reduced the drug loss in extrathoracic to approximately 5%.

Recently, the effect of fibers shape particles on particle deposition characteristics in human airways was examined using numerical simulation. The simulation model was a realizable k- ε model with DEM for fiber dynamics. Ellipsoid-shaped fibers with a density of 1000 kg/m3 and a mass equivalent to 1–20 μm spheres are simulated. The major discovery was that 5–7 μm fibers with high aspect ratios were the best for deposition in the bronchioles, while 4–6 μm fibers with high aspect ratios produced the highest deposition in the acinar areas [133].

The updated/new knowledge on this topic

The updated information and new knowledge have been explained in different sections throughout the manuscript; however, we have highlighted the conclusion of recently published research outcomes here. The particle surface modification, although not new, recent studies on micronisation in tandem with co-processing techniques showed enhanced surface properties of particles using minimal excipients, which have proven effectiveness[99]. Specifically, nanostructured porous aerogel showed significant potential for surface modification to enhance drug dispersibility. The high-dose antibiotic DPI products are limited; however, research in this area is progressing[100, 101]. Advanced strategies for developing high-dose DPI products with multiple drugs are continuing. Heat-assisted particle aerosolization, drug formulations and their stability, and DPI devices that can withstand the applied heat during aerosolization is an emerging area of research[134]. This groundbreaking approach could significantly improve the inhaled drug delivery technology.

Computational fluid dynamics along with the discrete element method uncovered that the elongated-shaped drug particles significantly increased particle deposition within the chamber and mouthpiece of Turbuhaler® due to the high van der Waals force between the particles and device wall[53]. The spherical shaped particles showed less attraction with the device walls. This study needs further investigation with other devices to draw a clear conclusion. We anticipate that the patient centered DPI products of various drugs with acceptable safety profiles will be available on market in near future.

Conclusions

During the last couple of decades, significant innovations in designing DPI devices and powder formulations have improved the performance of inhaler devices; however, the perfect inhalers for specific patients do not exist yet. The physicochemical properties of drug particles and DPI formulations with or without carrier based have shown some promising approaches in particulate drug delivery systems using DPIs as a carrier device. The future of DPI products is very bright. The formulation, device design, and patient inhalation profiles are crucial for efficient drug delivery into deep lungs. However, there is considerable space for improving the technology for maximum benefits. Using CFD and numerical modelling, an appropriate understanding of the powder properties, device design with a wide range of resistance for a large array of patients, including children and patients with impaired lung functions, appropriately engineered particles with proper flow properties can be developed with optimized drug dispersion from DPI devices. Patient training is another crucial parameter for successfully delivering drugs from delivery devices. Additionally, the patient’s adherence needs to be confirmed to ensure the required treatment outcomes from devices. In conclusion, the future generation of DPIs is anticipated to offer enhanced safety and superior therapeutic efficacy, surpassing the constraints associated with conventional high-dose DPIs. Nevertheless, it is imperative to rigorously evaluate and comment on these advancements to guarantee they adhere to the utmost safety and efficacy standards. We believe that the ongoing challenges will be overcome, and DPI therapy will hold great potential and promising options for treating various diseases in the future.

Author contributions

Conceptualization, NI and TS; Methodology, NI, TS, TS; Validation, NI, TS; Resources, NI; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, NI, TS, TS; Writing – Review & Editing, NI, TS; Supervision, NI; Project Administration, NI.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nazrul Islam, Email: nazrul.islam@qut.edu.au.

Teerapol Srichana, Email: teerapol.s@psu.ac.th, Email: nazrul.islam@qut.edu.au.

References

- 1.Ye Y, Ma Y, Zhu J. The future of dry powder inhaled therapy: Promising or discouraging for systemic disorders? Int J Pharm. 2022;614:121457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tse JY, Koike A, Kadota K, Uchiyama H, Fujimori K, Tozuka Y. Porous particles and novel carrier particles with enhanced penetration for efficient pulmonary delivery of antitubercular drugs. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2021;167:116–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ali AM, Abo Dena AS, Yacoub MH, El-Sherbiny IM. Exploring the influence of particle shape and air velocity on the flowability in the respiratory tract: a computational fluid dynamics approach. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2019;45(7):1149–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaikwad SS, Pathare SR, More MA, Waykhinde NA, Laddha UD, Salunkhe KS, Kshirsagar SJ, Patil SS, Ramteke KH. Dry Powder Inhaler with the technical and practical obstacles, and forthcoming platform strategies. J Control Release. 2023;355:292–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaurasiya B, Zhao YY. Dry powder for pulmonary delivery: A comprehensive review. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(1):1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moon C, Smyth HDC, Watts AB, Williams IIIRO. Delivery Technologies for Orally Inhaled Products: an Update. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2019;20(3):117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han X, Li D, Reyes-Ortega F, Schneider-Futschik EK. Dry Powder Inhalation for Lung Delivery in Cystic Fibrosis. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15(5):1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shukla SK, Sarode A, Kanabar DD, Muth A, Kunda NK, Mitragotri S, Gupta V. Bioinspired particle engineering for non-invasive inhaled drug delivery to the lungs. Mater Sci Eng C. 2021;128:112324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Clark AR, Weers JG, Dhand R. The Confusing World of Dry Powder Inhalers: It Is All about Inspiratory Pressures, Not Inspiratory Flow Rates. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2020;33(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stylianou FS, Angeli SI, Kassinos SC, Svensson M. 10th International symposium on turbulence and shear flow phenomena, TSFP10. Chicago: USA; 2017.

- 11.Yao Y, Capecelatro J. Numerical modeling of deagglomeration of cohesive particles by turbulence. AIChE Annual Meet Conf Proc. 2020:261a.

- 12.Benke E, Varga P, Szabó-Révész P, Ambrus R. Stability and in vitro aerodynamic studies of inhalation powders containing ciprofloxacin hydrochloride applying different dpi capsule types. Pharm. 2021;13:689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Pinto JT, Wutscher T, Stankovic-Brandl M, Zellnitz S, Biserni S, Mercandelli A, Kobler M, Buttini F, Andrade L, Daza V, Ecenarro S, Canalejas L, Paudel A. Evaluation of the physico-mechanical properties and electrostatic charging behavior of different capsule types for inhalation under distinct environmental conditions. AAPS PharmSciTech 2020;21(4):128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Wauthoz N, Hennia I, Ecenarro S, Amighi K. Impact of capsule type on aerodynamic performance of inhalation products: A case study using a formoterol-lactose binary or ternary blend. Int J Pharm. 2018;553(1–2):47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srichana T, Martin GP, Marriott C. Dry powder inhalers: The influence of device resistance and powder formulation on drug and lactose deposition in vitro. Eur J Pharm Sci. 1998;7(1):73–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hira D, Koide H, Nakamura S, Okada T, Ishizeki K, Yamaguchi M, Koshiyama S, Oguma T, Ito K, Funayama S, Komase Y, Morita SY, Nishiguchi K, Nakano Y, Terada T. Assessment of inhalation flow patterns of soft mist inhaler co-prescribed with dry powder inhaler using inspiratory flow meter for multi inhalation devices. PLoS One 2018;13(2):e0193082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Haidl P, Heindl S, Siemon K, Bernacka M, Cloes RM. Inhalation device requirements for patients’ inhalation maneuvers. Respir Med. 2016;118:65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pohlmann G, Hohlfeld JM, Haidl P, Pankalla J, Cloes RM. Assessment of the power required for optimal use of current inhalation devices. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2018;31(6):339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Louey MD, Razia S, Stewart PJ. Influence of physico-chemical carrier properties on the in vitro aerosol deposition from interactive mixtures. Int J Pharm. 2003;252(1–2):87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tiano SL, Dalby RN. Comparison of a respiratory suspension aerosolized by an air-jet and an ultrasonic nebulizer. Pharm Dev Technol. 1996;1(3):261–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silin N, Tarrio J, Guozden T. An experimental study of the aerodynamic dispersion of loose aggregates in an accelerating flow. Powder Technol. 2017;318:151–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Díez F. Capsule-based inhalers: Part I. Manuf Chem. 2019;90(1):42–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiroudaki S, Schoubben A, Giovagnoli S, Rekkas DM. Dry powder inhalers in the digitalization era: current status and future perspectives. Pharm. 2021;13(9):1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Díez F, Kalafat J, Bhat J. The science behind capsule-based dry powder inhalation technology. ONdrugDelivery. 2017;2017(80):4–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mehta PP. Dry powder inhalers: A concise summary of the electronic monitoring devices. Ther Deliv. 2021;12(1):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Healy AM, Amaro MI, Paluch KJ, Tajber L. Dry powders for oral inhalation free of lactose carrier particles. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2014;75:32–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schuster A, Haliburn C, Döring G, Goldman MH, Group FS. Safety, efficacy and convenience of colistimethate sodium dry powder for inhalation (Colobreathe DPI) in patients with cystic fibrosis: a randomised study. Thorax. 2013;68(4):344–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Boer AH, Hagedoorn P, Woolhouse R, Wynn E. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) assisted performance evaluation of the Twincer™ disposable high-dose dry powder inhaler. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64(9):1316–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoppentocht M, Akkerman OW, Hagedoorn P, Frijlink HW, De Boer AH. The Cyclops for pulmonary delivery of aminoglycosides; A new member of the Twincer™ family. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2015;90:8–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friebel C, Steckel H. Single-use disposable dry powder inhalers for pulmonary drug delivery. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010;7(12):1359–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jahan N, Archie SR, Shoyaib AA, Kabir N, Cheung K. Recent approaches for solid dose vaccine delivery. Sci Pharm. 2019;87(4):27.

- 32.Kanojia G, Have RT, Soema PC, Frijlink H, Amorij JP, Kersten G. Developments in the formulation and delivery of spray dried vaccines. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2017;13(10):2364–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corcoran TE, Venkataramanan R, Hoffman RM, George MP, Petrov A, Richards T, Zhang S, Choi J, Gao YY, Oakum CD, Cook RO, Donahoe M. Systemic delivery of atropine sulfate by the microdose dry-powder inhaler. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2013;26(1):46–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Islam N, Cleary MJ. Developing an efficient and reliable dry powder inhaler for pulmonary drug delivery–a review for multidisciplinary researchers. Med Eng Phys. 2012;34(4):409–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Islam N, Gladki E. Dry powder inhalers (DPIs)-A review of device reliability and innovation. Int J Pharm. 2008;360(1–2):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Boer AH, Hagedoorn P, Hoppentocht M, Buttini F, Grasmeijer F, Frijlink HW. Dry powder inhalation: past, present and future. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2017;14(4):499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weers JG, Son Y-J, Glusker M, Haynes A, Huang D, Kadrichu N, Le J, Li X, Malcolmson R, Miller DP, Tarara TE, Ung K, Clark A. Idealhalers Versus Realhalers: Is It Possible to Bypass Deposition in the Upper Respiratory Tract? J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2019;32(2):55–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byron PR. Prediction of drug residence times in regions of the human respiratory tract following aerosol inhalation. J Pharm Sci. 1986;75(5):433–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Newman SP, Chan H-K. In VitroIn Vivo Comparisons in Pulmonary Drug Delivery. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2008;21(1):77–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Islam N, Stewart P, Larson I, Hartley P. Effect of carrier size on the dispersion of salmeterol xinafoate from interactive mixtures. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93(4):1030–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Telko MJ, Hickey AJ. Aerodynamic and electrostatic properties of model dry powder aerosols: a comprehensive study of formulation factors. AAPS PharmSciTech. 2014;15(6):1378–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Islam N, Stewart P, Larson I, Hartley P. Surface roughness contribution to the adhesion force distribution of salmeterol xinafoate on lactose carriers by atomic force microscopy. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94(7):1500–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adi H, Traini D, Chan H-K, Young PM. The influence of drug morphology on the aerosolisation efficiency of dry powder inhaler formulations. J Pharm Sci. 2008;97(7):2780–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Telko Martin J, Hickey AJ. Dry powder inhaler formulation. Respir Care. 2005;50(9):1209–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Traini D, Young PM, Thielmann F, Acharya M. The Influence of Lactose Pseudopolymorphic Form on Salbutamol Sulfate-Lactose Interactions in dry powder inhaler Formulations. Drug Dev Ind Pharm. 2008;34(9):992–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peng T, Lin S, Niu B, Wang X, Huang Y, Zhang X, Li G, Pan X, Wu C. Influence of physical properties of carrier on the performance of dry powder inhalers. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2016;6(4):308–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hassan MS, Lau R. Effect of particle formulation on dry powder inhalation efficiency. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(21):2377–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin YW, Wong J, Qu L, Chan HK, Zhou QT. Powder production and particle engineering for dry powder inhaler formulations. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21(27):3902–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Crowder TM, Louey MD, Sethuraman VV, Smyth HDC, Hickey AJ. 2001: An odyssey in inhaler formulation and design. Pharm Techol. 2001;25(7):99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mullins ME, Michaels LP, Menon V, Locke B, Ranade MB. Effect of geometry on particle adhesion. Aerosol Sci Technol. 1992;17(2):105–18. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeng XM, Martin GP, Marriott C, Pritchard J. The effects of carrier size and morphology on the dispersion of salbutamol sulphate after aerosolization at different flow rates. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2000;52(10):1211–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zeng XM, Martin GP, Marriott C, Pritchard J. The influence of carrier morphology on drug delivery by dry powder inhalers. Int J Pharm. 2000;200(1):93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu Q, Gou D, Chan HK, Yang R. CFD-DEM investigation of the dispersion of elongated particles in the Turbuhaler® aerosol device. Powder Technol. 2024;437:119565.

- 54.Staniforth JN, Rees JE. Electrostatic charge interactions in ordered powder mixes. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1982;34(2):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Staniforth JN, Rees JE, Lai FK, Hersey TLJA. Interparticle forces in binary and ternary ordered powder mixes. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1982;34(3):141–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeung S, Traini D, Lewis D, Young PM. Dosing challenges in respiratory therapies. Int J Pharm. 2018;548(1):659–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]