Abstract

We tested a diverse set of 500 isolates of nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica from various animal, food, and human clinical sources for susceptibility to antimicrobials currently lacking epidemiological cutoff values (ECOFFs) set by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. A consortium of five different laboratories each tested 100 isolates, using broth microdilution panels containing twofold dilutions of ceftriaxone, cefepime, and colistin to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations of each drug when tested against the Salmonella isolates. Based on the resulting data, new ECOFFs of 0.25 μg/mL for ceftriaxone, 0.12 μg/mL for cefepime, and 2 μg/mL for colistin have been proposed. These thresholds will aid in the identification of Salmonella that have phenotypically detectable resistance mechanisms to these important antimicrobials.

Keywords: Salmonella, antimicrobial resistance, ECOFF, ceftriaxone, cefepime, colistin

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance in human pathogens is a critical public health problem, contributing to poor patient outcomes and increased healthcare costs. Therefore, it has become increasingly important to develop useful metrics for antimicrobial resistance, particularly to detect emerging resistance.

In the United States, the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) monitors antimicrobial resistance among foodborne pathogens, including isolates from food animals, retail meats, and humans. Historically, NARMS has relied on clinical breakpoints set by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI; Wayne, PA) to interpret bacteria as susceptible or resistant to different antimicrobials, although the breakpoints can vary based on dosing regimens and are not based on distinguishing populations of bacteria based on the presence of acquired resistance mechanisms.

One alternative to using clinical breakpoints is the use of epidemiological cutoff values (ECOFFs), which divide bacteria into wild-type and nonwild-type strains based on distributions of their minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs). These ECOFFs are better suited to detect acquired resistance and correlate with genotypically detectable resistance mechanisms (Tyson et al., 2017). However, ECOFFs are not typically used for therapeutic decision-making by clinicians, and a nonwild-type isolate is not necessarily clinically resistant. In this study, NARMS sought to develop Salmonella enterica ECOFFs for ceftriaxone, cefepime, and colistin, as these cutoffs are currently lacking in data presented by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST), a body that publishes ECOFFs as interpretive criteria.

Ceftriaxone is a third-generation cephalosporin that is used clinically in humans to treat infections caused by Gram--negative organisms, including Salmonella (Lin et al., 2003). Cefepime is a fourth-generation cephalosporin effective against AmpC β-lactamase-producing bacteria that can also be used to treat human cases of salmonellosis (Tamma et al., 2013). Although human clinical breakpoints exist for both ceftriaxone and cefepime, currently there are no ECOFFs to detect emerging resistance mechanisms for either drug for Salmonella. Colistin is not a standard therapy for Salmonella infections in humans; however, an ECOFF could help identify trends in emerging resistance such as the novel mcr-1 plasmid-borne colistin resistance mechanism (Liu et al., 2016).

Materials and Methods

In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Five laboratories were involved in testing, including at the Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (FDA-CVM), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United States Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety and Inspection Service and Agricultural Research Service, and the Joint Institute for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. Each of these laboratories has been longtime participants in or collaborators with the U.S. NARMS program.

Each of these five laboratories tested 100 S. enterica isolates, including those from food animal cecal and fecal samples, carcass rinses, retail meat products, and human clinical samples. These isolates were collected as part of routine surveillance activities of the participating laboratories, and each laboratory tested 100 different isolates. Isolates were tested on a custom-dried broth microdilution panel (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) containing twofold dilutions of ceftriaxone (0.004–64 μg/mL), cefepime (0.008–32 μg/mL), and colistin (0.06–32 μg/mL). Quality control organisms Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853 were used and tested in accordance with ISO 20776–1, the accepted EUCAST method for susceptibility testing (EUCAST, 2017).

ECOFF determinations

To define ECOFFs, the program ECOFFinder was used according to the instructions (https://clsi.org/education/microbiology/ecoffinder) (Turnidge et al., 2006). A 99.0% cutoff was applied, meaning that approximately 99.0% of the wild-type MIC distribution was less than the identified ECOFF value. The Normalized Resistance Interpretation (NRI) tool was also used as a comparator, and defines ECOFFs to be 2 standard deviations from the mean MIC of the wild-type distribution (Kronvall, 2010). MIC values were submitted to EUCAST in April 2018 to establish new ECOFFs.

Results and Discussion

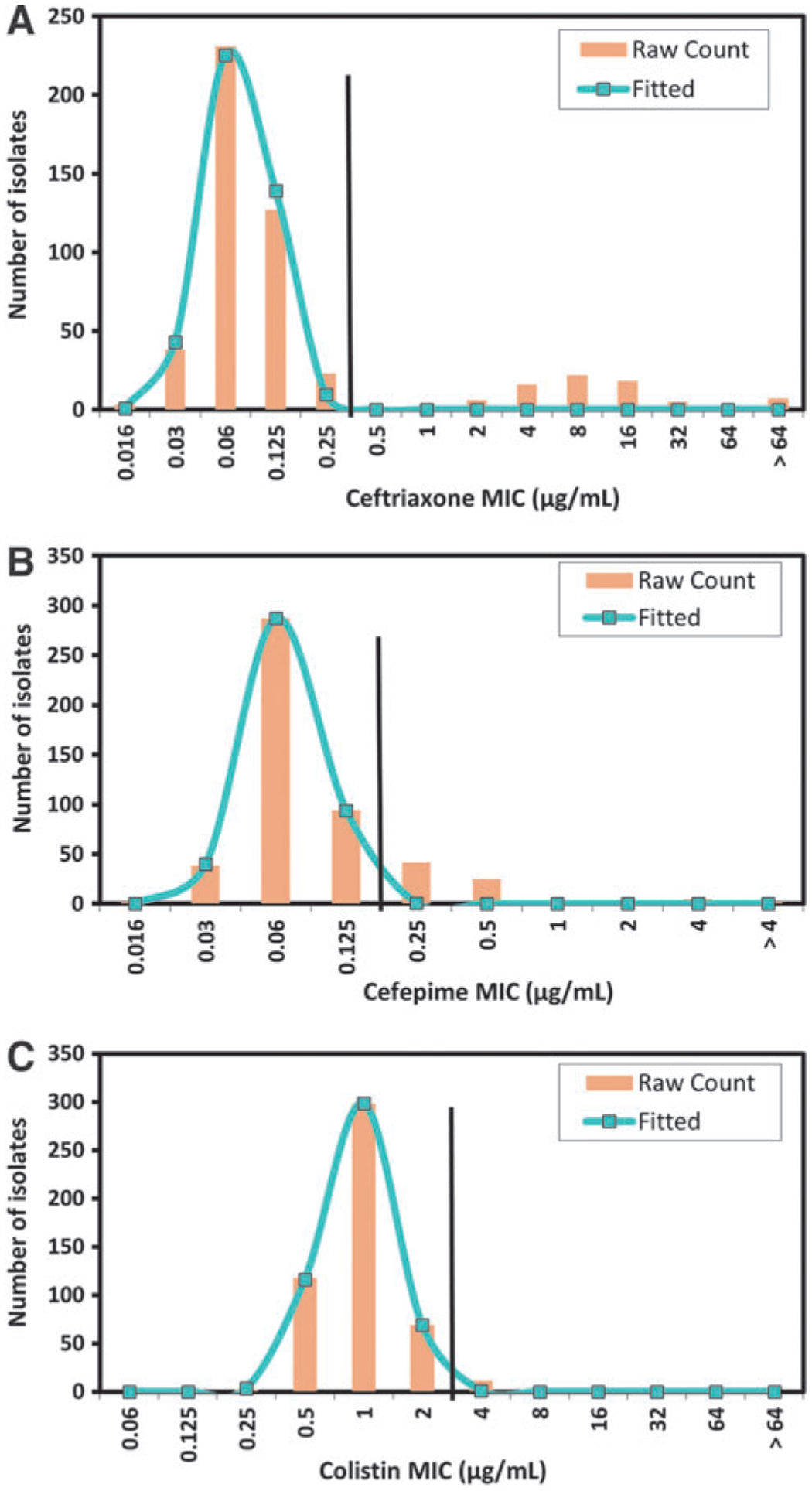

We sought to generate ECOFFs for ceftriaxone, cefepime, and colistin by testing 500 isolates of S. enterica across five laboratories, including isolates from diverse sample sources, such as food animals, retail meats, and human clinical samples. These resulted in a total of 62 different serotypes present in the isolate collection (Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/fpd). Combined data from the five laboratories demonstrated unimodal MIC distributions for each of the three drugs (Fig. 1). Wide testing ranges in the custom panels ensured that precise MIC readings were obtained for all wild-type isolates, with no isolates with MICs less than or equal to the lowest dilution tested for any of the drugs.

FIG. 1.

Nontyphoidal Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica MIC distributions for isolates from food animal, retail food, and human sources for (A) ceftriaxone, (B) cefepime, and (C) colistin. Raw counts depict the observed number of isolates at each MIC, with the fitted line of the MIC distribution modeled by ECOFFinder to include 99.0% of the wild-type isolates below the ECOFF. Vertical black lines indicate the proposed ECOFF dividing wild-type strains from nonwild-type strains presumed to have acquired resistance mechanisms. ECOFF, epidemiological cutoff values; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

For ceftriaxone, the ECOFF based on the ECOFFinder 99.0% threshold was 0.25 μg/mL, meaning that isolates with MICs ≥0.5 μg/mL would be considered nonwild-type (Fig. 1A). For cefepime, the ECOFF was 0.12 μg/mL, although our MIC distribution did not appear to fully fit a normal distribution due to a gradual tapering of MIC frequencies at the high end of the distribution (Fig. 1B). This may be explained by the presence of isolates with low-potency β-lactamases causing elevated MICs. Finally, for colistin, the proposed ECOFF was 2 μg/mL (Fig. 1C), meaning that isolates with MICs ≥4 μg/mL would be considered nonwild-type.

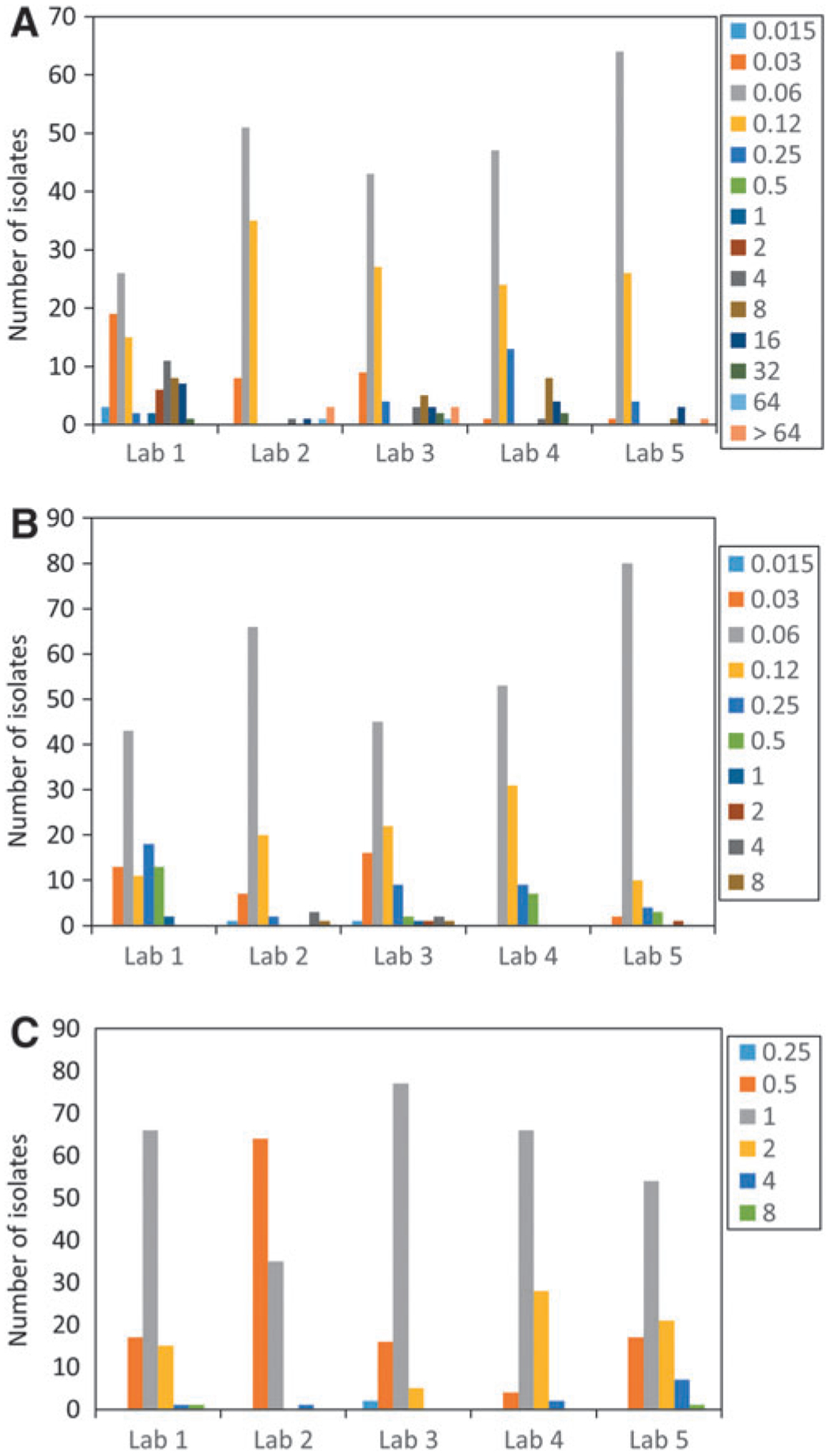

It is worth noting that the ECOFFs for all three drugs were identical using both ECOFFinder and NRI methods (Kronvall, 2010; EUCAST, 2017), further supporting the proposed ECOFFs. Results were also highly consistent among laboratories (Fig. 2), with the peak in the wild-type MIC distribution from all five laboratories matching for each antimicrobial, except for laboratory 2 in the colistin distribution (Fig. 2C). Thus, these data adhered to the EUCAST guideline that all individual laboratory distributions must have a peak within one dilution of the mode in the aggregated wild-type distribution.

FIG. 2.

MIC distributions for each of five laboratories for (A) ceftriaxone, (B) cefepime, and (C) colistin. The height of each of the bars refers to the number of isolates with particular MIC values (depicted in the legend). All units are in μg/mL.

Although the presentation of new ECOFFs is valuable for differentiating wild-type and nonwild-type strains, these phenotypes do not always correspond with genotypic measures of resistance. For instance, the proposed Salmonella ECOFF for ceftriaxone is 0.25 μg/mL, whereas the genotypic cutoff value, a cutoff based on the presence of known resistance mechanisms, was found to be 1 μg/mL (Tyson et al., 2017). Although relatively few isolates are typically in the 0.5–1 μg/mL range, the distinction between these cutoffs is important. Therefore, additional genetic data could be valuable to discern whether isolates with a particular MIC value can be predicted to have resistance mechanisms.

Importantly, the recent identification of mcr genes conferring colistin resistance has demonstrated the need for colistin ECOFFs to help identify strains to be screened for colistin resistance mechanisms. Most groups have used cutoffs of ≥4 μg/mL to identify nonwild-type isolates (Chiou et al., 2017), whereas others have used cutoffs of ≥2 μg/mL or ≥8 μg/mL (Li et al., 2016; Garcia-Graells et al., 2018). The data presented in this study support the use of 2 μg/mL as the colistin ECOFF for Salmonella, meaning that isolates with MICs ≥4 μg/mL would be considered nonwild-type. Interestingly, several of the isolates with MICs above this proposed ECOFF were of serotypes Dublin and Enteritidis, confirming earlier findings that Salmonella of these serotypes have reduced colistin susceptibility (Agerso et al., 2012).

In summary, we have three newly proposed ECOFFs for Salmonella, which will be valuable additions to antimicrobial resistance surveillance programs. In particular, the need for the colistin ECOFF has become an emerging issue, as different measures to identify nonwild-type strains have been reported. Establishing new ECOFFs only requires a total of 100 isolates across a minimum of five laboratories (EUCAST, 2017), so the use of 500 total isolates from a variety of sources provides us a high degree of confidence in the proposed cutoffs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Jean Whichard for her critical review of the article.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, the United States Department of Agriculture, the Food Safety and Inspection Service, or the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the Food and Drug Administration.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Agerso Y, Torpdahl M, Zachariasen C, Seyfarth A, Hammerum AM, Nielsen EM. Tentative colistin epidemiological cut-off value for Salmonella spp. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2012;9:367–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiou CS, Chen YT, Wang YW, et al. Dissemination of mcr-1-Carrying Plasmids among Colistin-Resistant Salmonella Strains from Humans and Food-Producing Animals in Taiwan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017;61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EUCAST. EUCAST SOP 10.0: MIC distributions and the setting of epidemiological cutoff (ECOFF) values. Basel, Switzerland: European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, 2017, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Graells C, De Keersmaecker SCJ, Vanneste K, et al. Detection of Plasmid-Mediated Colistin Resistance, mcr-1 and mcr-2 Genes, in Salmonella spp. Isolated from Food at Retail in Belgium from 2012 to 2015 . Foodborne Pathog Dis 2018;15:114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronvall G Normalized resistance interpretation as a tool for establishing epidemiological MIC susceptibility breakpoints. J Clin Microbiol 2010;48:4445–4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li XP, Fang LX, Song JQ, et al. Clonal spread of mcr-1 in PMQR-carrying ST34 Salmonella isolates from animals in China. Sci Rep 2016;6:38511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin TY, Chiu CH, Lin PY, Wang MH, Su LH, Lin TY. Short-term ceftriaxone therapy for treatment of severe non-typhoidal Salmonella enterocolitis. Acta Paediatr 2003;92:537–540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: A microbiological and molecular biological study. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:161–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamma PD, Girdwood SC, Gopaul R, et al. The use of cefepime for treating AmpC beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57:781–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnidge J, Kahlmeter G, Kronvall G. Statistical characterisation of bacterial wild-type MIC value distributions and the determination of epidemiological cut-off values. Clin Microbiol Infect 2006;12:418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson GH, Zhao S, Li C, et al. Establishing genotypic cutoff values to measure antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017;61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.