Abstract

Salmonella enterica serovar Dublin is a host-adapted serotype associated with typhoidal disease in cattle. While rare in humans, it usually causes severe illness, including bacteremia. In the United States, Salmonella Dublin has become one of the most multidrug-resistant (MDR) serotypes. To understand the genetic elements that are associated with virulence and resistance, we sequenced 61 isolates of Salmonella Dublin (49 from sick cattle and 12 from retail beef) using the Illumina MiSeq and closed 5 genomes using the PacBio sequencing platform. Genomic data of eight human isolates were also downloaded from NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) for comparative analysis. Fifteen Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs) and a spv operon (spvRABCD), which encodes important virulence factors, were identified in all 69 (100%) isolates. The 15 SPIs were located on the chromosome of the 5 closed genomes, with each of these isolates also carrying 1 or 2 plasmids with sizes between 36 and 329 kb. Multiple antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs), including blaCMY-2, blaTEM-1B, aadA12, aph(3′)-Ia, aph(3′)-Ic, strA, strB, floR, sul1, sul2, and tet(A), along with spv operons were identified on these plasmids. Comprehensive antimicrobial resistance genotypes were determined, including 17 genes encoding resistance to 5 different classes of antimicrobials, and mutations in the housekeeping gene (gyrA) associated with resistance or decreased susceptibility to fluoroquinolones. Together these data revealed that this panel of Salmonella Dublin commonly carried 15 SPIs, MDR/virulence plasmids, and ARGs against several classes of antimicrobials. Such genomic elements may make important contributions to the severity of disease and treatment failures in Salmonella Dublin infections in both humans and cattle.

Keywords: Salmonella Dublin, pathogenicity islands, antimicrobial resistance, MDR plasmid

Introduction

Salmonella enterica serotype Dublin is a host-adapted serotype associated with typhoidal disease in cattle. The symptoms include fever, diarrhea, abortions, septicemia, and respiratory signs.1,2 Although the incidence of Salmonella Dublin infections in humans is low, it frequently causes severe illness, including bloodstream infections. A recent report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed that there was an increase in hospitalization and mortality rates by Salmonella Dublin infections from 1996–2004 (68% hospitalization, 2.7% mortality) to 2005–2013 (78% hospitalization, 4.2% mortality).3

The genetic background of pathogens is known to play a critical role in contributing to infection outcomes.4–6 Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs) contain many genes encoding virulence factors, including different types of secretion systems (T1SS, T3SS, and T6SS), adhesins, effector proteins, and other factors associated with bacterial invasion, enteropathogenesis, intracellular survival, and proliferation.7–10 The type III secretion systems (T3SS) encoded on SPI 1 and SPI 2 are important virulence factors that have been well studied.7,11–14 The acquisition of SPIs can be achieved through horizontal gene transfer from other bacterial species and is considered to be a “quantum leap” in Salmonella evolution,8,10,15,16 which is evidenced based on gene function, base composition, and codon usage. SPIs not only carry virulence genes but also are frequently associated with mobile DNA elements such as insertion sequences and bacteriophages as well as genes encoding tRNA.17 To date, 21 SPIs have been reported.6,8,13,18 They are diverse in structure and function, and even the same SPI can vary among different serotypes, suggesting a range of transmissible elements that are likely involved in the continuing evolution of SPI and host specificity.10,15 Among the 21 SPIs, some such as SPI 1–5, 9, 13, and 14 are conserved throughout the Salmonella genus, whereas others are specific for certain serotypes.10 For example, Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 carries 13 SPIs, whereas Salmonella Typhi carries 17 SPIs.6 Analysis of a limited number of isolates has shown that Salmonella Dublin carries various SPIs,10 but no reports are available on the comprehensive genomic structure and distribution of SPIs in Salmonella Dublin from different sources.

Salmonella Dublin also contains a virulence plasmid that carries a spvRABCD operon.5 The spvR gene encodes a transcriptional regulator required for expression of spvABCD.5 Several studies have shown that spv genes can enhance the virulence of Salmonella by increasing the rate of bacterial replication within host cells and can produce lethal disease in mice.19–22 Libby et al. also showed that spv genes are required for severe enteritis and systemic infection to occur in the natural host.5 Virulence plasmids have been identified in other host-adapted serotypes such as Salmonella Choleraesuis (swine), Salmonella Paratyphi (human), Salmonella Gallinarum and Salmonella Pullorum (chicken), Salmonella Abortusovis (sheep), and some highly invasive strains of the broad-host serotypes of Salmonella Typhimurium and Salmonella Enteritidis.5,23,24 Although the genetic diversity of virulence plasmids in different serotypes has been reported, there is a lack of understanding on the diversity and genetic structure of virulence plasmids within the same serotype. In the past, identification and molecular characterization of virulence plasmids and SPIs relied on PCR, microarrays, cloning, and Southern hybridizations, but such approaches have limitations and are unable to provide a clear picture of the structure and organization of virulence plasmids and SPIs.

Salmonella Dublin has become one of the most antimicrobial-resistant serotypes in the United States. The CDC reported that multidrug-resistant (MDR) Salmonella Dublin (resistant to ≥7 classes of antimicrobials) increased from 2.4% during 1996–2004 to 50.8% during 2005–2013.3 The National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) 2015 annual report also showed that MDR (resistant to ≥3 classes) Salmonella Dublin isolated from cattle increased from 54.7% during 1998–2004 to 85.2% during 2005–2015.25 A study by Zhao et al. showed that 100% (n = 32) of Salmonella Dublin isolated from sick cattle were resistant to ≥5 antimicrobials, and 31% (n = 10) were resistant to ≥9 antimicrobials.26 Previously, we used PCR followed by sequence analysis to detect antimicrobial resistance genes (ARGs) or mutations conferring resistance, which is a time-intensive process. PCR-based detection also suffers from potentially failing to detect ARGs in the presence of primer sequence divergence. Recent studies have shown the power and promise of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) technology, which can offer the highest practical resolution for characterizing genetic determinates of individual microbes, including the full complement of resistance determinants.27–29 The objective of this study was to investigate the presence, distribution, and diversity of SPIs, virulence plasmids, and resistomes of Salmonella Dublin strains isolated from humans, sick cattle, and retail beef in the United States.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains

A total of 61 Salmonella Dublin isolates including 49 from sick cattle isolated in Arizona between 2003 and 2005 and 12 from retail ground beef isolated between 2012 and 2014 (Table 1) were available from our culture collections for the study. Forty-nine cattle isolates were from Arizona State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, and the antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) profile of these isolates was previously reported.26 WGS data from eight human clinical isolates, which were isolated from 2014 to 2015, were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) for comparative genomic analysis. Thirteen other Salmonella serotypes including Salmonella Typhimurium, Salmonella Kentucky, Salmonella Reading, Salmonella Schwarzengrund, Salmonella Johannesburg, Salmonella Heidelberg, Salmonella Muenchen, Salmonella Newport, Salmonella Infantis, Salmonella Enteritidis, Salmonella Saintpaul, Salmonella Hadar, and Salmonella Senftenberg isolated from retail meats in 2015 were also included in the study for comparative genomic analysis. All isolates were stored at −80°C in Brucella broth with 20% glycerol until use.

Table 1.

Salmonella Strains Used in This Study

| ID No. | Serotype | Source | State | Year | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVM22427 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952677 |

| CVM22429 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | CP032396–CP032397 |

| CVM22434 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952678 |

| CVM22435 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952675 |

| CVM22439 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952674 |

| CVM22440 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952673 |

| CVM22441 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952672 |

| CVM22442 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952671 |

| CVM22445 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952670 |

| CVM22449 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952669 |

| CVM22451 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952666 |

| CVM22452 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952668 |

| CVM22453 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | CP32393–CP032395 |

| CVM22455 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952665 |

| CVM22456 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952664 |

| CVM22463_R | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952663 |

| CVM22465 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952662 |

| CVM22466 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952661 |

| CVM22467 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952660 |

| CVM 22468_R | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952659 |

| CVM22469 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952658 |

| CVM 22470_R | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952656 |

| CVM22471 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952657 |

| CVM22472 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952655 |

| CVM22473 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952654 |

| CVM22475 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952653 |

| CVM 22477_R | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952652 |

| CVM 22482_R | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952651 |

| CVM 22485_R | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952650 |

| CVM 22486_R | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952649 |

| CVM22487 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952648 |

| CVM22492 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2003 | SRR6952646 |

| CVM34977 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2004 | SRR6952647 |

| CVM34980 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2004 | SRR6952645 |

| CVM34981 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2004 | CP032390–CP032392 |

| CVM34982 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2004 | SRR6952643 |

| CVM34983 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2004 | SRR6952642 |

| CVM35538 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952640 |

| CVM35539 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952641 |

| CVM35540 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952639 |

| CVM35541 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952638 |

| CVM35549 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952637 |

| CVM35551 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952636 |

| CVM35552 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952635 |

| CVM35553 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952633 |

| CVM35555 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952634 |

| CVM35556 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952631 |

| CVM35557 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952632 |

| CVM35563 | Salmonella Dublin | Cattle | AZ | 2005 | SRR6952630 |

| N40387 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | MD | 2012 | SRR3664744 |

| N41733 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | CA | 2012 | SRR3664802 |

| N42502 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | NY | 2012 | SRR3664934 |

| N42512 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | PA | 2012 | SRR3664944 |

| N45955 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | OR | 2013 | CP032387–CP032389 |

| N50443 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | OR | 2013 | SRR2567125 |

| N50446 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | OR | 2013 | SRR2567128 |

| N51251 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | CO | 2013 | SRR2567144 |

| N51298 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | NM | 2013 | SRR2567191 |

| N53043 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | MN | 2014 | CP032384–CP032386 |

| N53083 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | WA | 2014 | SRR2407658 |

| N54720 | Salmonella Dublin | GB | MO | 2014 | SRR2407736 |

| SRR1953054a | Salmonella Dublin | Human | N/A | 2014 | SRR1953054 |

| SRR2043689a | Salmonella Dublin | Human | N/A | 2015 | SRR2043689 |

| SRR2043690a | Salmonella Dublin | Human | N/A | 2015 | SRR2043690 |

| SRR2043691a | Salmonella Dublin | Human | N/A | 2015 | SRR2043691 |

| SRR2968111a | Salmonella Dublin | Human | N/A | 2015 | SRR2968111 |

| SRR2968112a | Salmonella Dublin | Human | N/A | 2015 | SRR2968112 |

| SRR2968113a | Salmonella Dublin | Human | N/A | 2015 | SRR2968113 |

| SRR2968114a | Salmonella Dublin | Human | N/A | 2015 | SRR2968114 |

| N55869 | Salmonella Typhimurium | GB | TN | 2015 | SRR3295518 |

| N55936 | Salmonella Kentucky | CB | CA | 2015 | SRR3295520 |

| N55937 | Salmonella Reading | GT | CA | 2015 | SRR3295521 |

| N55938 | Salmonella Schwarzengrund | GT | CA | 2015 | SRR3295522 |

| N55939 | Salmonella Johannesburg | PC | CA | 2015 | SRR3295523 |

| N56232 | Salmonella Heidelberg | GT | CT | 2015 | SRR3295527 |

| N56233 | Salmonella Muenchen | GT | CT | 2015 | SRR3295528 |

| N56252 | Salmonella Newport | CB | PA | 2015 | SRR3295534 |

| N56554 | Salmonella Infantis | CB | CA | 2015 | SRR3932910 |

| N56556 | Salmonella Enteritidis | CB | CA | 2015 | SRR3932912 |

| N56567 | Salmonella Saintpaul | GT | NM | 2015 | SRR3295552 |

| N56571 | Salmonella Hadar | GT | NY | 2015 | SRR3295555 |

| N56984 | Salmonella Senftenberg | GT | CA | 2015 | SRR4280565 |

All human WGS data were downloaded from NCBI.

AZ, Arizona; CA, California; CB, chicken breast; CO, Colorado; CT, Connecticut; GB, ground beef; GT, ground turkey; MD, Maryland; MN, Minnesota; MO, Missouri; N/A, state information not available; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; NM, New Mexico; NY, New York; OR, Oregon; PA, Pennsylvania; PC, pork chop; TN, Tennessee; WA, Washington; WGS, whole-genome sequencing.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

In vitro AST was performed using 14 antimicrobials, including gentamicin (GEN), streptomycin (STR), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC), cefoxitin (FOX), ceftiofur (TIO), ceftriaxone (CRO), sulfisoxazole (FIS), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (SXT), ampicillin (AMP), chloramphenicol (CHL), ciprofloxacin (CIP), nalidixic acid (NAL), azithromycin (AZM), and tetracycline (TET). Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined by broth microdilution using dehydrated panels CMV2AGNF and CMV3AGNF (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) following standard protocols.25 Antimicrobial resistance was defined using the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) criteria,30 except for streptomycin (≥32 mg/L) and azithromycin (≥32 mg/L) for which there are no clinical breakpoints25 (https://www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/SafetyHealth/AntimicrobialResistance/NationalAntimicrobialResistanceMonitoringSystem/ucm059103.htm).

Genome sequencing, assembly, and annotation

Genomic DNA was extracted with QIAamp 96 DNA QIAcube HT Kit (Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD) on an automated high-throughput DNA extraction machine QIAcube HT per the manufacturer’s instructions. WGS was performed using the MiSeq platform using v3 reagent kits (Illumina, San Diego, CA) with 2 × 300 paired end option. Assembly was performed de novo for each isolate using CLC Genomics Workbench version 8.0 (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark). Five isolates including three from sick cattle and two from retail beef were selected to close the genomes and plasmids using the Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) RS II Sequencer (PacBio®, Menlo Park, CA. USA). The continuous long reads were assembled by PacBio Hierarchical Genome Assembly Process (HGAP3.0) program.31 The size of chromosome ranged from 4,844,293 to 4,877,381 bp with coverage from 570× to 750×. The size of 9 circular plasmids ranges from 36,009 to 329,264 bp with coverage from 170× to 1270×.

Genomes were annotated using the NCBIs Prokaryotic Genome Automated Pipeline version 2.9.32 The closed genomes were annotated on the Rapid Annotation using Sub-system Technology (RAST) annotation server. Among the 61 Salmonella Dublin isolates, there was a median of 88 contigs (ranging from 51 to 161) and 48-fold coverage (ranging from 26 to 90) per genome.

Identification of antimicrobial resistance genotypes

Antimicrobial resistance genes were identified using Perl scripts to perform local blastn with ResFinder (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder) with at least 85% amino acid identity and 50% sequence length to known ARG sequences. Sequences showing less than 100% identity and/or sequence length were examined by additional BLAST analysis to identify the appropriate ARGs. Mutations in gyrA, gyrB, parC, and parE genes were identified using an in-house pipeline.

SPIs and virulence spvRABCD operon identification

Sequences of 21 SPIs were downloaded from GenBank to a local database. The size of the SPIs ranged from 1.7 to 133.3 kb, encoding 1–21 virulence genes. SPIs were identified from several Salmonella serotypes, including Salmonella Typhimurium, Salmonella Typhi, Salmonella Dublin, and Salmonella IIIa 62:z4,z23:- (Table 2). The sequence of the spvRABCD operon was extracted from the pSDVr (pOU1115) plasmid (Accession No. DQ115388). A local blastn search was performed to determine the existence of SPIs and spvRABCD operon among the 69 Salmonella Dublin isolates as well as the 13 other Salmonella serotypes.

Table 2.

Salmonella Pathogenicity Islands Identified in Different Salmonella Serotypes

| SPI | Serotype | Accession No. | Location | Size, bp | GC% | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPI 1 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 3005849–3048153 | 42305 | 45.5 | 32 |

| SPI 2 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 1461731–1501480 | 39750 | 47.4 | 32 |

| SPI 3 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 3948999–3985278 | 36280 | 49.6 | 32 |

| SPI 4 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 4477865–4501275 | 23411 | 44.8 | 32 |

| SPI 5 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 1175536–1182100 | 6565 | 43.6 | 32 |

| SPI 6 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 304666–351358 | 46693 | 52.4 | 32 |

| SPI 7 | Salmonella Typhi CT18 | NC_003198 | 4409652–4542913 | 133262 | 49.7 | 32 |

| SPI 8 | Salmonella Typhi CT18 | NC_003198 | 3132530–3139414 | 6885 | 38.3 | 32 |

| SPI 9 | Salmonella Typhi CT18 | NC_003198 | 2743495–2759190 | 15696 | 57.7 | 32 |

| SPI 10 | Salmonella Typhi CT18 | NC_003198 | 4683605–4716538 | 32934 | 46.6 | 32 |

| SPI 11 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 1326065–1334385 | 8321 | 40.9 | 32 |

| SPI 12 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 2330960–2345977 | 15018 | 47.2 | 32 |

| SPI 13 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 3276387–3301691 | 25305 | 48.5 | 32 |

| SPI 14 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 926180–933609 | 7430 | 41.4 | 32 |

| SPI 15 | Salmonella Typhi CT18 | NC_003198 | 3054094–3059809 | 5716 | 49.5 | 32 |

| SPI 16 | Salmonella Typhimurium LT2 | NC_003197 | 613596–617725 | 4130 | 42.1 | 32 |

| SPI 17 | Salmonella Typhi CT18 | NC_003198 | 2461018–2465128 | 4111 | 38.4 | 32 |

| SPI 18 | Salmonella Typhi CT18 | NC_003198 | 1455055–1456801 | 1747 | 39 | 32 |

| SPI 19 | Salmonella Dublin CT_02021853 | NC_011205 | 1203281–1239108 | 35828 | 53.8 | 3 |

| SPI 20 | Salmonella IIIa 62:z4,z23:- | NC_010067 | 2617493–2651483 | 33991 | 53.1 | 3 |

| SPI 21 | Salmonella IIIa 62:z4,z23:- 62:z4,z23:- | NC_010067 | 2504768–2560524 | 55757 | 49.7 | 3 |

GC, Guanine (G), Cytosine (C); SPI, Salmonella pathogenicity island.

Plasmid typing

Plasmid type was determined using PlasmidFinder (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder), and the sequences were blasted with the database to known plasmid types with 95% sequence identity and over at least 60% sequence length compared with the reference sequences.

Whole-genome phylogenetic analysis

The single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) analysis of 61 Salmonella Dublin isolates along with 8 human isolates downloaded from the NCBI database was performed using the Food and Drug Administration Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN)-SNP-Pipeline (http://snp-pipeline.readthedocs.io/en/latest). A closed genome sequence of isolate CVM34981 served as a reference genome. VarScan33 was used to detect SNPs. The plasmid sequences were excluded in the analysis since they evolved through horizontal gene transfer, which may misrepresent the evolution path of the isolates. SNP redundancy by linkage disequilibrium was reduced, and the phylogenetic tree was constructed with the maximum likelihood algorithm using the SNPhylo package.34

Results

Resistance phenotypes and genotypes

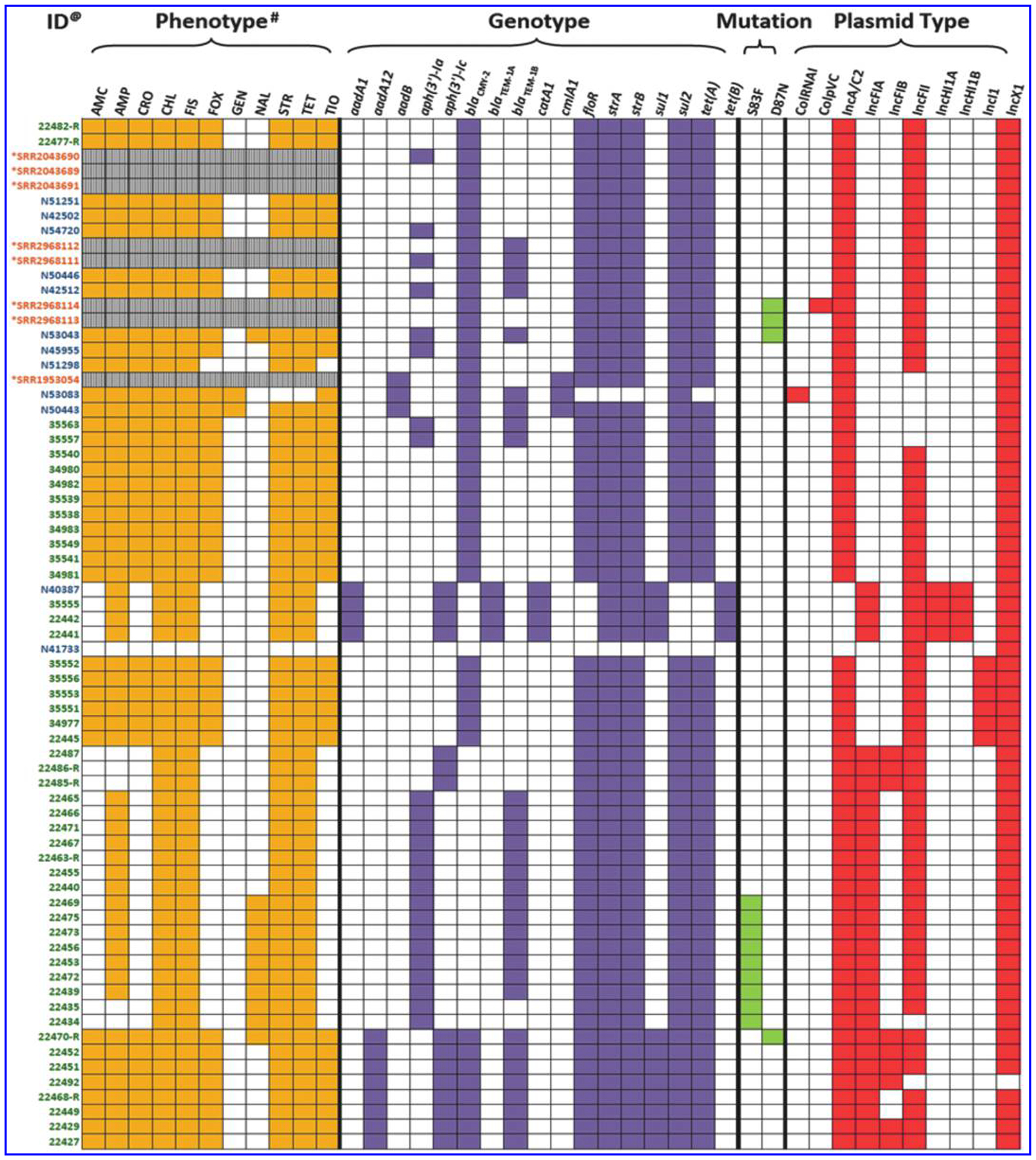

AST showed that 60 of 61 Salmonella Dublin isolates recovered from retail beef and sick cattle were resistant to ≥4 antimicrobial classes (Fig. 1). The most common resistance pattern was blaAmpC type, AMP-FOX-CRO-AMC-TIO-CHL-TET-FIS-STR (n = 35, 57%) followed by AMP-CHL-TET-FIS-STR (n = 10, 16%) and AMP-CHL-TET-FIS-STR-NAL (n = 7, 11%). Eleven isolates showed resistant to NAL. One isolate (N41733) was susceptible to all 14 antimicrobials tested. A total of 17 ARGs including aadA1(4/69, 5.8%), aadA12 (8/69, 11.6%), aadB (3/69, 4.3%), aph(3′)-Ia (24/69, 34.8%), aph(3′)-Ic (15/69, 21.7%), blaCMY-2 (45/69, 65.2%), blaTEM-1A (4/69, 5.8%), blaTEM-1B (31/69, 44.9%), catA1(4/69, 5.8%), cmlA1 (3/69, 4.3%), floR (63/69, 91.3%), strA (67/69, 97.1%), strB (67/69, 97.1%), sul1 (12/69, 17.4%), sul2 (64/69, 92.8%), tet(A) (63/69, 91.3%), and tet(B) (4/69, 5.8%) were identified (Fig. 1). In addition, GyrA S83F (9/69, 13%) or D87N (4/69, 5.8%) mutations were identified in 13 NAL-resistant isolates, including 10 NAL-resistant animal isolates, 1 retail meat isolate, and 2 human isolates. Overall, the resistance phenotypes had 99.8% correspondence with resistance genotypes. One isolate (N51298) carrying blaCMY-2 gene showed only resistance to AMP, AMC, and TIO, but intermediate resistance to CRO (MIC, 4 μg/mL) and FOX (MIC, 16 μg/mL). The resistance phenotypes of the human isolates from NCBI were not available and therefore were not included in the analysis.

FIG. 1.

Resistance phenotype, genotype, and plasmid profiles of Salmonella Dublin strains isolated from cattle, beef, and humans. @Green—cattle, blue—beef isolates, orange—human isolates. *These are human isolates, and no antimicrobial susceptibility data were available. #AMC, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid; AMP, ampicillin; CRO, ceftriaxone; CHL, chloramphenicol; FIS, sulfisoxazole; FOX, cefoxitin; GEN, gentamicin; NAL, nalidixic acid; SPIs, Salmonella pathogenicity islands; STR, streptomycin; TET, tetracycline; TIO, ceftiofur.

Presence and distribution of SPIs and spvRABCD

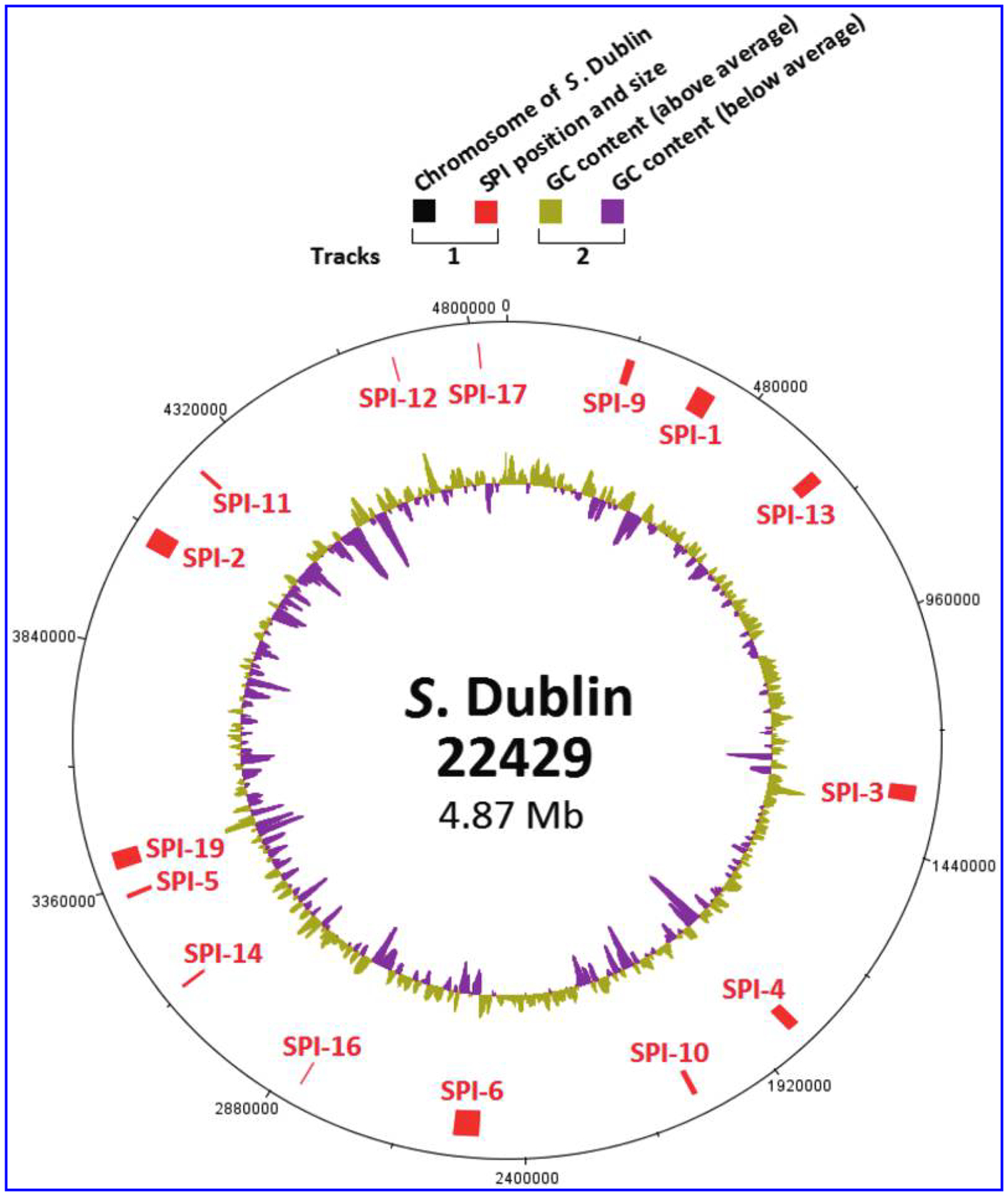

Fifteen SPIs, including SPI 1–6, 9–14, 16, 17, and 19, were identified in all 69 Salmonella Dublin isolates. The 15 SPIs were scattered throughout the entire Salmonella Dublin chromosome (Fig. 2), and their locations were the same in all 5 closed genomes. The gene content in each of 15 SPIs conserved in all 69 Salmonella Dublin isolates with 0–29 SNP difference (data not shown). Of the other 13 Salmonella serotypes, broadly chosen to represent common serotypes in the NARMS collection, all except Salmonella Enteritidis carried 11–12 various SPIs (Table 3). Salmonella Enteritidis (N56556) carried the same 15 SPIs as Salmonella Dublin but had greater variability in gene content and number of SNP differences compared with each of the Salmonella Dublin genomes. For example, a 24 kb deletion in SPI 19 was detected in Salmonella Enteritidis, whereas the corresponding sequences were harbored by all Salmonella Dublin genomes. The spvRABCD virulence operon was identified in all 69 Salmonella Dublin isolates. Except for Salmonella Typhimurium, none of the other 12 serotypes harbored the spvRABCD virulence operon (Table 3).

FIG. 2.

Presence and distribution of SPIs in Salmonella Dublin genome. The color codes are given on the top of the figure.

Table 3.

Distribution of Salmonella Pathogenicity Islands in Different Salmonella Serotypes

| Serotypea | SPI 1 | SPI 2 | SPI 3 | SPI 4 | SPI 5 | SPI 6 | SPI 7 | SPI 8 | SPI 9 | SPI 10 | SPI 11 | SPI 12 | SPI 13 | SPI 14 | SPI 15 | SPI 16 | SPI 17 | SPI 18 | SPI 19 | SPI 20 | SPI 21 | spvRABCD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dublin | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| Typhimurium | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Kentucky | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Reading | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Schwarzengrund | + | + | .+ | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Johannesburg | + | + | .+ | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − |

| Heidelberg | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Muenchen | + | + | .+ | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Newport | + | + | .+ | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Infantis | + | + | .+ | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Enteritidis | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | − |

| Saintpaul | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Hadar | + | + | .+ | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Senftenberg | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

The data were generated from 69 Salmonella Dublin strains and 1 strain from each of other 13 serotypes.

Plasmid types

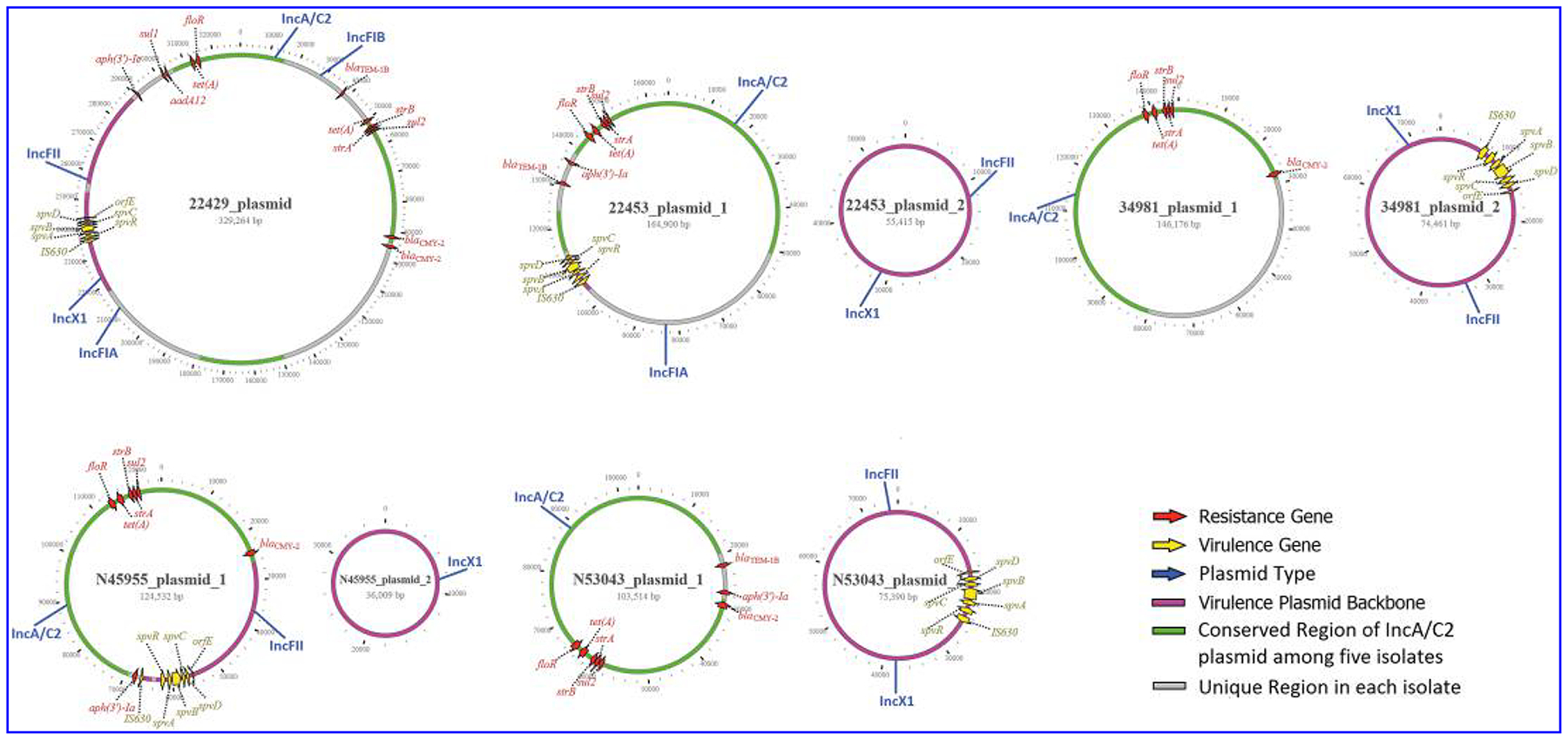

Ten plasmid types, including CoIRNAI, ColpVC, IncA/C2, IncFIA, IncFIB, IncFII, IncHI1A, IncHI1B, IncI1, and IncX1, were identified by PlasmidFinder among the 69 Salmonella Dublin isolates. Each isolate contained two to five different plasmid types with the most common ones being IncX1 (n = 69, 100%), IncA/C2 (n = 64, 92.3%), and IncFII (n = 63, 91.3%) (Fig. 1). However, based on plasmid analysis of the five closed genomes, each of these isolates carried only one to two plasmids. Several single plasmids from these isolates were typed to two to five different plasmid types (Fig. 3). For example, CVM22429 carried a single megaplasmid with a size of 329 kb and was typed as IncA/C2-IncFIA-IncFIB-IncFII-IncX1. This plasmid carried 10 different ARGs, including aadA12, aph(3′)-Ic, blaCMY-2, blaTEM-1B, floR, strA, strB, sul1, sul2, and tet(A) plus a spvRABCD virulence operon (Fig. 3). The other four isolates (CVM22453, CVM34981, N45955, and N53043) carried two plasmids each. Five single plasmids from these isolates were also typed as two plasmid types, including the combination of IncA/C2-IncFIA, IncA/C2-IncFII, and IncX1-IncFII, respectively (Fig. 3). CVM34981 and N53043 carried separate MDR (IncA/C2) and virulence (IncX1-IncFII) plasmids. However, CVM22453 and N45955 possessed backbone-only virulence plasmids (IncX1-IncFII or IncX1) without spvRABCD. The spvRABCD operon integrated into IncA/C2 MDR plasmids (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Structure of MDR and virulence plasmids in five strains of Salmonella Dublin. The color codes are given on the right of the figure. MDR, multidrug-resistant.

Whole-genome phylogenetic trees

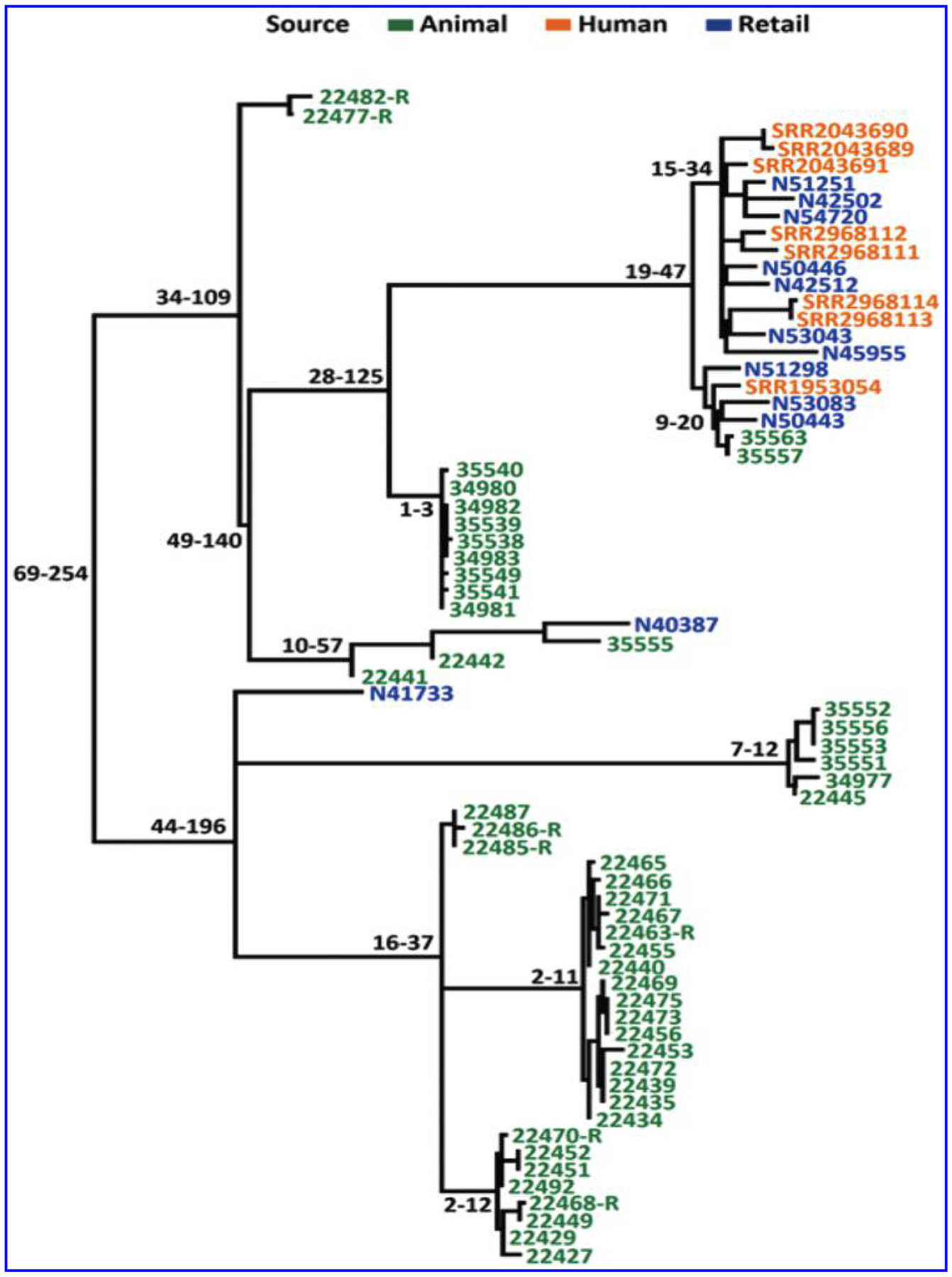

The SNP tree of the 69 Salmonella Dublin isolates showed that they were highly clonal, with a maximum of 254 core-genome SNP differences despite the fact that they were from different sources and collected in different years (Fig. 4). One branch contained 20 isolates from humans, retail meat, and cattle with ≤47 SNP differences and included strains isolated from 2005 to 2015. The remaining branches consisted solely of animal and retail meat isolates. Although this may indicate that a particular group of related isolates are more likely to cause human infections, this remains to be further investigated with the inclusion of additional human isolates.

FIG. 4.

hqSNP core-genome tree of Salmonella Dublin strains isolated from cattle, retail beef, and humans.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to identify genetic elements that contribute to the highly pathogenic and antimicrobial-resistant nature of Salmonella Dublin.3 We performed WGS and comparative genomic analysis on 69 representative Salmonella Dublin isolates recovered from the U.S. food animals, retail beef, and humans. The study shed light on the distributions of SPIs and the spvRAVCD operon, and more detailed information on the structure of MDR/virulence plasmids.

SPIs contribute to host cell invasion and intracellular pathogenesis. Previous studies indicated the same SPI may have great variation among different serotypes, which is likely due to continuing evolution of SPI and host specificity.8,16–18 Our results showed that the distribution of SPIs varied among different serotypes, with some of these findings differing from those in previous reports. Suez et al. reported that SPI 1–5, 9, 13, and 14 were a part of core genome of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella (iNTS); SPI 6, 10–12, 16–19 were variable among genomes, and SPI 7, 8 15 were absent in iNTS.10 However, our data showed that SPI 6 and SPI 11 also were part of the core genome, but SPI 13 and SPI 14 were not. The SPI 8 was detected in Salmonella Kentucky and Salmonella Senftenberg. These differences with previous reports may be due to methodologies used in the two studies. In the study by Suez et al., microarray-based comparative genomic hybridization was employed. Additionally, isolates and serotypes were different between the two studies, and only one strain per serotype was included in the current study. Sabbagh et al.6 reported that SPI 7, 8, 15, 17, and 18 were specific to Salmonella Typhi, and Blondel et al.18 indicated that SPI 19, 20, and 21 were absent in both Salmonella Typhimurium and Salmonella Typhi. We detected SPI 17 and SPI 19 in all 69 Salmonella Dublin isolates and 1 Salmonella Enteritidis isolate, whereas SPI 18 was found in Salmonella Reading, Salmonella Schwarzengrund, and Salmonella Johannesburg. SPI 8 was thought to be specific for Salmonella Typhi,17 but we detected it in Salmonella Kentucky and Salmonella Senftenberg. Although Salmonella Dublin and Salmonella Enteritidis carried the same SPIs, further analysis showed that there was great diversity within some SPIs between these two serotypes in terms of gene content and SNP differences within the same genes (data not shown). As more Salmonella WGS data from different serotypes and sources become available, comparative genomic analysis will improve and can provide a comprehensive picture on the distribution, diversity, and host specificity of SPIs in different serotypes. Such information not only allows us to identify highly virulent strains and serotypes but also helps us to understand the evolution of SPI, Salmonella pathogenicity, and host specificity.

Several studies indicated that a spvRABCD operon in Salmonella Dublin enhances the severity of the enteric infection and produces lethal disease in mice and calves by increasing the proliferation of Salmonella Dublin in a variety of tissues, at both intestinal and extraintestinal sites.5,20 We detected the spvRABCD operon in all 69 Salmonella Dublin isolates and 1 Salmonella Typhimurium isolate. A spvRABCD operon is a hallmark for Salmonella Dublin and also has been found in nearly all host-adapted serotypes, except the human-specific serotype Salmonella Typhi, as well as some highly invasive strains of the broad-host serotypes of Salmonella Typhimurium and Salmonella Enteritidis.5,23,24

The spvRABCD operon is usually located on a virulence plasmid,15,19 which has replicons IncX1 and IncFII.35 Our data showed that a spv operon was not always located on IncX1 and IncFII plasmids. In CVM22429, CVM22453, and N45955, a spv operon integrated into an MDR IncA/C2 plasmid and MDR-virulence plasmids were typed as IncA/C2-IncFIA-IncFIB-IncFII-IncX1, IncA/C2-IncFIA, and IncA/C2-IncFII, respectively, based on PlasmidFinder. CVM34981 and N53043 carried MDR IncA/C2 and virulence plasmids (IncX1 or IncX1-IncFII) independently (Fig. 3). CVM22429 carried a single mega-plasmid plasmid, which contained a spvRABCD operon plus 12 ARGs. This megaplasmid contained sequences that had high homology to five plasmid replicons, including IncA/C2, IncFIB, IncFIA, InxX1, and IncFII. These results clearly indicated that recombination events have occurred between the MDR plasmid and virulence plasmids. Because of the complexity due to such recombination events, using traditional PCR plasmid typing and PlasmidFinder based on short-read WGS data for plasmid analysis has major limitations. The PlasmidFinder database was developed based on unique short sequences (200–800 bp) of plasmid replicons for Enterobacteriaceae.36 This approach may not be reliable because the full structure of a plasmid cannot be revealed since recombination, insertion, or deletion events often occur among plasmids. It is important to close a plasmid to study plasmid biology, evolution, and plasmid typing.

Salmonella Dublin has developed into one of the most antimicrobial-resistant serotypes in the United States. Among 61 Salmonella Dublin isolates recovered from sick cattle in Arizona and retail meats, all except 1 were resistant to ≥4 antimicrobial classes tested. Seventeen ARGs plus gyrA mutations were identified. Current study showed that an IncA/C2 MDR plasmid is commonly present in Salmonella Dublin and often carries many ARGs, including blaCMY-2. In this study, 45 Salmonella Dublin isolates had blaCMY-2 and also carried the IncA/C2 plasmid. Reports by Folster et al. have indicated that although the IncA/C2 plasmid has a broad host range, human infection with Salmonella strains that carry IncA/C2 linked with blaCMY-2 most commonly involved serotypes usually associated with bovine sources, such as Salmonella Newport and Salmonella Dublin.37 The information of plasmid type and linkages with specific ARGs can potentially be used for outbreak investigations and foodborne disease source attribution studies. These results are in line with previous data from the United States1 but are in contrast to the data from Europe and other countries, where Salmonella Dublin also causes severe infections in humans but is not associated with high levels of antimicrobial resistance.36 In that report, no acquired ARGs were detected in 33 Salmonella Dublin isolates, and of 22 human invasive isolates, only 2 carried various ARGs, including resistance to aminoglycoside, phenicol, sulfonamide, beta-lactam, and trimethoprim.36 The AMR differences between this panel of isolates and those from Europe may be due to the MDR IncA/C2 plasmid has been spreading on the U.S. cattle farms, but may not in Europe.

Finally, a whole-genome SNP tree showed that Salmonella Dublin is highly clonal. There are less than 260 SNP differences among 69 isolates. This may be due to limited isolates available for this study, especially all sick cattle isolates were from Arizona. To determine the genomic diversity of Salmonella Dublin, further study is needed to include more Salmonella Dublin strains from different countries and states, as well as from different sources. It is interesting that one particular branch with less than 50 SNP differences contained 8 Salmonella Dublin isolates from humans, 10 from retail beef, and 2 from sick cattle. All 20 of these isolates carry IncA/C2 and IncX1 plasmids as well as blaCMY-2 and spvRABCD. The data clearly showed that this is a highly virulent and resistant clone, and food animals and contaminated meats could be sources of human infections. Human isolates were only within this branch. This may be due to the fact that a limited number of human isolates were included in the study. Therefore, a more representative panel of human isolates recovered from different geographic locations and times is needed for further comparative genomic analysis.

In conclusion, we employed WGS to further understand the genetics contributing to antibiotic resistance and severe infections in a collection of 69 Salmonella Dublin isolates from humans, animals, and food in the United States. Despite lacking of representative isolates from different geographic locations and sources, we found that Salmonella Dublin isolates in this study commonly carried 15 SPIs, a spvRABCD virulence operon, and several MDR and virulence plasmids. These genetic elements may contribute to the severity of disease and potential treatment failures in both humans and cattle. WGS offers high resolution for detection and characterization of full components of virulence and antimicrobial resistance determinants. More studies that include closing plasmids are needed to study MDR and virulence plasmid structure, biology, evolution, and plasmid typing.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Maureen Davison for helpful comments and article review. We would also like to acknowledge Ms. Claudia Lam for handling all WGS submissions. This work was supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration with internal funds as part of routine work.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or Food and Drug Administration.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.McDonough PL, Fogelman D, Shin SJ, Brunner MA, and Lein DH. 1999. Salmonella enterica serotype Dublin infection: an emerging infectious disease for the north-eastern United States. J. Clin. Microbiol 37:2418–2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nielsen LR, Schukken YH, Grohn YT, and Ersboll AK. 2004. Salmonella Dublin infection in dairy cattle: risk factors for becoming a carrier. Prev. Vet. Med 65:47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey RR, Friedman CR, Crim SM, Judd M, Barrett KA, Tolar B, Folster JP, Griffin PM, and Brown AC. 2017. Epidemiology of Salmonella enterica Serotype Dublin infections among humans, United States, 1968–2013. Emerg. Infect. Dis 23. DOI: 10.3201/eid2309.170136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kingsley RA, Msefula CL, Thomson NR, Kariuki S, Holt KE, Gordon MA, Harris D, Clarke L, Whitehead S, Sangal V, Marsh K, Achtman M, Molyneux ME, Cormican M, Parkhill J, MacLennan CA, Heyderman RS, and Dougan G. 2009. Epidemic multiple drug resistant Salmonella Typhimurium causing invasive disease in sub-Saharan Africa have a distinct genotype. Genome Res 19:2279–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libby SJ, Adams LG, Ficht TA, Allen C, Whitford HA, Buchmeier NA, Bossie S, and Guiney DG. 1997. The spv genes on the Salmonella dublin virulence plasmid are required for severe enteritis and systemic infection in the natural host. Infect. Immun 65:1786–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabbagh SC, Forest CG, Lepage C, Leclerc JM, and Daigle F. 2010. So similar, yet so different: uncovering distinctive features in the genomes of Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium and Typhi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett 305:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerlach RG, and Hensel M. 2007. Protein secretion systems and adhesins: the molecular armory of Gram-negative pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol 297:401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hensel M 2004. Evolution of pathogenicity islands of Salmonella enterica. Int. J. Med. Microbiol 294:95–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rychlik I, Karasova D, Sebkova A, Volf J, Sisak F, Havlickova H, Kummer V, Imre A, Szmolka A, and Nagy B. 2009. Virulence potential of five major pathogenicity islands (SPI-1 to SPI-5) of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis for chickens. BMC Microbiol 9:268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suez J, Porwollik S, Dagan A, Marzel A, Schorr YI, Desai PT, Agmon V, McClelland M, Rahav G, and Gal-Mor O. 2013. Virulence gene profiling and pathogenicity characterization of non-typhoidal Salmonella accounted for invasive disease in humans. PLoS One 8:e58449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerlach RG, Jackel D, Geymeier N, and Hensel M. 2007. Salmonella pathogenicity island 4-mediated adhesion is coregulated with invasion genes in Salmonella enterica. Infect. Immun 75:4697–4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerlach RG, Jackel D, Stecher B, Wagner C, Lupas A, Hardt WD, and Hensel M. 2007. Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 4 encodes a giant non-fimbrial adhesin and the cognate type 1 secretion system. Cell Microbiol 9:1834–1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcus SL, Brumell JH, Pfeifer CG, and Finlay BB. 2000. Salmonella pathogenicity islands: big virulence in small packages. Microbes Infect 2:145–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt H, and Hensel M. 2004. Pathogenicity islands in bacterial pathogenesis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev 17:14–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amavisit P, Lightfoot D, Browning GF, and Markham PF. 2003. Variation between pathogenic serovars within Salmonella pathogenicity islands. J. Bacteriol 185: 3624–3635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groisman EA, and Ochman H. 1996. Pathogenicity islands: bacterial evolution in quantum leaps. Cell 87: 791–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerlach RG, and Hensel M. 2007. Salmonella pathogenicity islands in host specificity, host pathogen-interactions and antibiotics resistance of Salmonella enterica. Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr 120:317–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blondel CJ, Jimenez JC, Contreras I, and Santiviago CA. 2009. Comparative genomic analysis uncovers 3 novel loci encoding type six secretion systems differentially distributed in Salmonella serotypes. BMC Genomics 10:354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guiney DG, Fang FC, Krause M, and Libby S. 1994. Plasmid-mediated virulence genes in non-typhoid Salmonella serovars. FEMS Microbiol. Lett 124:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guiney DG, Fang FC, Krause M, Libby S, Buchmeier NA, and Fierer J. 1995. Biology and clinical significance of virulence plasmids in Salmonella serovars. Clin. Infect. Dis 21(Suppl 2):S146–S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulig PA, Danbara H, Guiney DG, Lax AJ, Norel F, and Rhen M. 1993. Molecular analysis of spv virulence genes of the Salmonella virulence plasmids. Mol. Microbiol 7:825–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gulig PA, and Doyle TJ. 1993. The Salmonella typhimurium virulence plasmid increases the growth rate of salmonellae in mice. Infect. Immun 61:504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haneda T, Okada N, Nakazawa N, Kawakami T, and Danbara H. 2001. Complete DNA sequence and comparative analysis of the 50-kilobase virulence plasmid of Salmonella enterica serovar Choleraesuis. Infect. Immun 69:2612–2620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotger R, and Casadesus J. 1999. The virulence plasmids of Salmonella. Int. Microbiol 2:177–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.FDA. 2015. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS): 2015 Retail Meat Report. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao S, McDermott PF, White DG, Qaiyumi S, Friedman SL, Abbott JW, Glenn A, Ayers SL, Post KW, Fales WH, Wilson RB, Reggiardo C, and Walker RD. 2007. Characterization of multidrug resistant Salmonella recovered from diseased animals. Vet. Microbiol 123:122–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDermott PF, Tyson GH, Kabera C, Chen Y, Li C, Folster JP, Ayers SL, Lam C, Tate HP, and Zhao S. 2016. Whole-genome sequencing for detecting antimicrobial resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 60:5515–5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyson GH, Li C, Ayers S, McDermott PF, and Zhao S. 2016. Using whole-genome sequencing to determine appropriate streptomycin epidemiological cutoffs for Salmonella and Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett 363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao S, Tyson GH, Chen Y, Li C, Mukherjee S, Young S, Lam C, Folster JP, Whichard JM, and McDermott PF. 2016. Whole-genome sequencing analysis accurately predicts antimicrobial resistance phenotypes in Campylobacter spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol 82:459–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.CLSI. 2016. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 26th ed. CLSI Supplement M100-S26. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffmann M, Payne J, Roberts RJ, Allard MW, Brown EW, and Pettengill JB. 2015. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Agona 460004 2-1, associated with a multistate outbreak in the United States. Genome Announc 3:e00690–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Angiuoli SV, Gussman A, Klimke W, Cochrane G, Field D, Garrity G, Kodira CD, Kyrpides N, Madupu R, Markowitz V, Tatusova T, Thomson N, and White O. 2008. Toward an online repository of Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for (meta)genomic annotation. OMICS 12: 137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koboldt DC, Zhang Q, Larson DE, Shen D, McLellan MD, Lin L, Miller CA, Mardis ER, Ding L, and Wilson RK. 2012. VarScan 2: somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Res 22:568–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee TH, Guo H, Wang X, Kim C, and Paterson AH. 2014. SNPhylo: a pipeline to construct a phylogenetic tree from huge SNP data. BMC Genomics 15:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohammed M, Le Hello S, Leekitcharoenphon P, and Hendriksen R. 2017. The invasome of Salmonella Dublin as revealed by whole genome sequencing. BMC Infect. Dis 17:544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carattoli A, Zankari E, Garcia-Fernandez A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, Moller Aarestrup F, and Hasman H. 2014. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 58:3895–3903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Folster JP, Tolar B, Pecic G, Sheehan D, Rickert R, Hise K, Zhao S, Fedorka-Cray PJ, McDermott P, and Whichard JM. 2014. Characterization of blaCMY plasmids and their possible role in source attribution of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium infections. Foodborne Pathog. Dis 11:301–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]