Abstract

Whole-genome sequencing (WGS) has changed our understanding of bacterial pathogens, aiding outbreak investigations and advancing our knowledge of their genetic features. However, there has been limited use of genomics to understand antimicrobial resistance of veterinary pathogens, which would help identify emerging resistance mechanisms and track their spread. The objectives of this study were to evaluate the correlation between resistance genotypes and phenotypes for Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, a major pathogen of companion animals, by comparing broth microdilution antimicrobial susceptibility testing and WGS. From 2017–2019, we conducted antimicrobial susceptibility testing and WGS on S. pseudintermedius isolates collected from dogs in the United States as a part of the Veterinary Laboratory Investigation and Response Network (Vet-LIRN) antimicrobial resistance monitoring program. Across thirteen antimicrobials in nine classes, resistance genotypes correlated with clinical resistance phenotypes 98.4 % of the time among a collection of 592 isolates. Our findings represent isolates from diverse lineages based on phylogenetic analyses, and these strong correlations are comparable to those from studies of several human pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella enterica. We uncovered some important findings, including that 32.3 % of isolates had the mecA gene, which correlated with oxacillin resistance 97.0 % of the time. We also identified a novel rpoB mutation likely encoding rifampin resistance. These results show the value in using WGS to assess antimicrobial resistance in veterinary pathogens and to reveal putative new mechanisms of resistance.

Keywords: Staphylococcus pseudintermedius, Antimicrobial resistance, Genomics

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance is a One Health issue that poses a major threat to human and animal health. Genomics is an essential tool to track the spread of resistance, detect outbreaks caused by resistant bacteria, and inform strategies to combat resistance.

Recent advances in genomics have allowed for the rapid and accurate identification of resistance genes and mutations in bacterial sequences. Thus, genomics data have been used to accurately predict phenotypic resistance for a number of bacterial species, including Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis, among others (McDermott et al., 2016; Tyson et al., 2015; Witney et al., 2016). The development of publicly available resistance gene databases such as AMRFinder and ResFinder have aided in these efforts (Feldgarden et al., 2019; Zankari et al., 2012).

Fewer studies have used genomics to understand antimicrobial resistance in bacteria from companion animals, where treatment failures can result in animal deaths, as well as zoonoses that may impact human health (Walther et al., 2017). Recent work has shown that genomics can be used to help track the spread of resistant bacteria in companion animals and identify resistance mechanisms (Cole et al., 2020; Tyson et al., 2019).

To date, most genomics work in staphylococci has been on the human pathogen S. aureus (Gordon et al., 2014). Staphylococcus pseudintermedius is a veterinary pathogen that primarily causes skin and soft tissue infections in dogs and cats, although it can also cause more serious and invasive infections (Bannoehr and Guardabassi, 2012; Qekwana et al., 2017). It also occasionally infects humans in close contact with infected companion animals (Blondeau et al., 2020). Infections in companion animals are typically treated with antimicrobials, which depending on the location of infection may be systemic or topical. Treatment failures can occur when the bacteria are resistant to drug classes of medical importance, such as with methicillin-resistant S. pseudintermedius (MRSP) (van Duijkeren et al., 2011). MRSP has emerged globally across multiple lineages and is frequently resistant to multiple major classes of antibiotics used in veterinary medicine (Perreten et al., 2010).

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genomics work in S. pseudintermedius and other veterinary pathogens has been limited. One of the most significant efforts was from a collection of 50 MRSP isolates, where 98 % of resistance genotypes correlated with phenotypes (Wegener et al., 2018). However, this was a small dataset and only included methicillin-resistant isolates. Other AMR genomics work in S. pseudintermedius has included few isolates to help elucidate resistance mechanisms in specific drug classes (Kadlec et al., 2011; Kizerwetter-Swida et al., 2016). More recent work involved sequencing 130 S. pseudintermedius isolates from New England to study the diverse lineages of this species, but did not correlate resistance genotypes with phenotypes (Smith et al., 2020). Similarly, another study involved sequencing 160 isolates from Texas, but did not include comparison of resistance genotypes and phenotypes (Little et al., 2019).

In 2017, the FDA’s Veterinary Laboratory Investigation and Response Network (Vet-LIRN) started a pilot AMR monitoring program, with routine susceptibility testing and sequencing of veterinary pathogens collected from clinical cases by a network of veterinary diagnostic laboratories. Bacteria collected as part of this monitoring included S. enterica from all animals, and E. coli and S. pseudintermedius from dogs. We had previously published preliminary genomics analysis from the AMR monitoring program, including 60 S. pseudintermedius, but there was no comparison with phenotypic data (Ceric et al., 2019).

Vet-LIRN’s continued AMR monitoring has resulted in the collection of 592 isolates of S. pseudintermedius from dogs that have both susceptibility testing and sequencing data. This work describes the use of genomics to identify resistance mechanisms in these isolates and their correlation with clinical resistance phenotypes. This work helps advance our knowledge of S. pseudintermedius genomics, as well as track and monitor the spread of AMR in this important pathogen.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Isolation and Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (AST)

S. pseudintermedius isolates were collected from dogs from 2017 to 2019 from twenty-five sites across the United States and five from Canada. A total of 592 isolates were from the United States and had both AST and WGS conducted, with 41 isolates from Canada that had only WGS data. Bacteria were identified by the original/source laboratory’s protocol, which included a variety of identification methods within the Vet-LIRN network. These included matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or biochemical identification, such as with analytical profile index (API) or Sensititre Identification System. Isolates consisted of clinical specimens collected predominantly from skin, urine, and ear as part of routine processes (Ceric et al., 2019). The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of each drug was determined by broth microdilution. The types of panels varied across laboratories, including the drugs included and MIC ranges, so not every isolate was tested for susceptibility to every drug reported. Panels were read by various AST systems, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Sensititre, Biomic or Vitek). MIC testing was in accordance with CLSI methods using prescribed media, atmosphere, reading times, and quality control strains (CLSI, 2018b). Resistance breakpoints followed the CLSI standards in the Vet08 document (CLSI, 2018a), with breakpoints based on those listed for S. pseudintermedius or Staphylococcus spp. These breakpoints to denote resistance are as follows: penicillin, ≥ 0.25 μg/mL; oxacillin, ≥ 0.5 μg/mL; gentamicin, ≥ 16 μg/mL; tetracycline, ≥ 1 μg/mL; minocycline, ≥ 2 μg/mL; doxycycline, ≥ 0.5 μg/mL; enrofloxacin, ≥ 4 μg/mL; marbofloxacin, ≥ 4 μg/mL; pradofloxacin, ≥ 2 μg/mL; vancomycin, ≥ 32 μg/mL; rifampin, ≥ 4 μg/mL; erythromycin, ≥ 8 μg/mL; clindamycin, ≥ 4 μg/mL; chloramphenicol, ≥ 32 μg/mL; and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ≥ 4/76 μg/mL. MICs below these breakpoints were considered susceptible for genotype-phenotype correlations, including those with intermediate MICs.

2.2. Whole-genome sequencing

A subset of isolates with susceptibility testing data were de-identified and sent as part of routine care to six laboratories that performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) using standardized methods (Ceric et al., 2019). These included a total of 592 isolates from the United States and 41 from Canada. Library preparation was performed using Illumina Nextera XT or DNA Flex/Prep kits, and sequencing was performed on the Illumina MiSeq platform using V2 or V3 chemistry. Sequences were submitted to NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) in BioProjects PRJNA318593, PRJNA318594, PRJNA324567, PRJNA324579, PRJNA481347, and PRJNA503853. Individual accession numbers are listed in Table S1. All sequences met GenomeTrakr network requirements for quality, including ≥ 30 average read quality Q score for R1 and R2, ≥ 20-fold coverage, and ≤ 300 contigs. Sequences were assembled by NCBI with SKESA and resistance genes were identified with AMRFinder version 3 (Feldgarden et al., 2019). Resistance gene calls were downloaded on April 10, 2020 from the NCBI Isolates Browser for further analysis. Regulatory genes identified by AMRFinder (blaI, blaR1 for blaZ and mecI, mecR for mecA) were removed from the outputs for clarity, with blaPC1 being renamed to blaZ for consistency. Resistance genotype information is displayed in Table S1. Sequence typing was performed in silico with MLST 2.0 (Larsen et al., 2012), with sequence types listed in Table S1.

2.3. Genotype-phenotype correlations

In addition to resistance gene outputs from AMRFinder, analysis of amino acid changes in GyrA, GrlA, RpoB, PBP2, PBP4, and FolP was also conducted using MEGA version 7. The presence of relevant resistance genes and/or mutations were compared to MIC data to determine genotype-phenotype correlations. When an isolate was resistant to a particular drug and had an accompanying resistance gene or mutation, then genotype and phenotype were correlated. The same was true if an isolate was susceptible and no mechanism was identified. In cases of mis-correlations or partial genes, additional BLAST analysis was conducted to determine whether resistance genes were full-length.

We performed repeat susceptibility testing on 26 isolates that had genotype-phenotype discrepancies across multiple drug classes. Repeat sequencing was conducted for the isolates where discrepancies were not resolved.

3. Results

3.1. Resistance prevalence

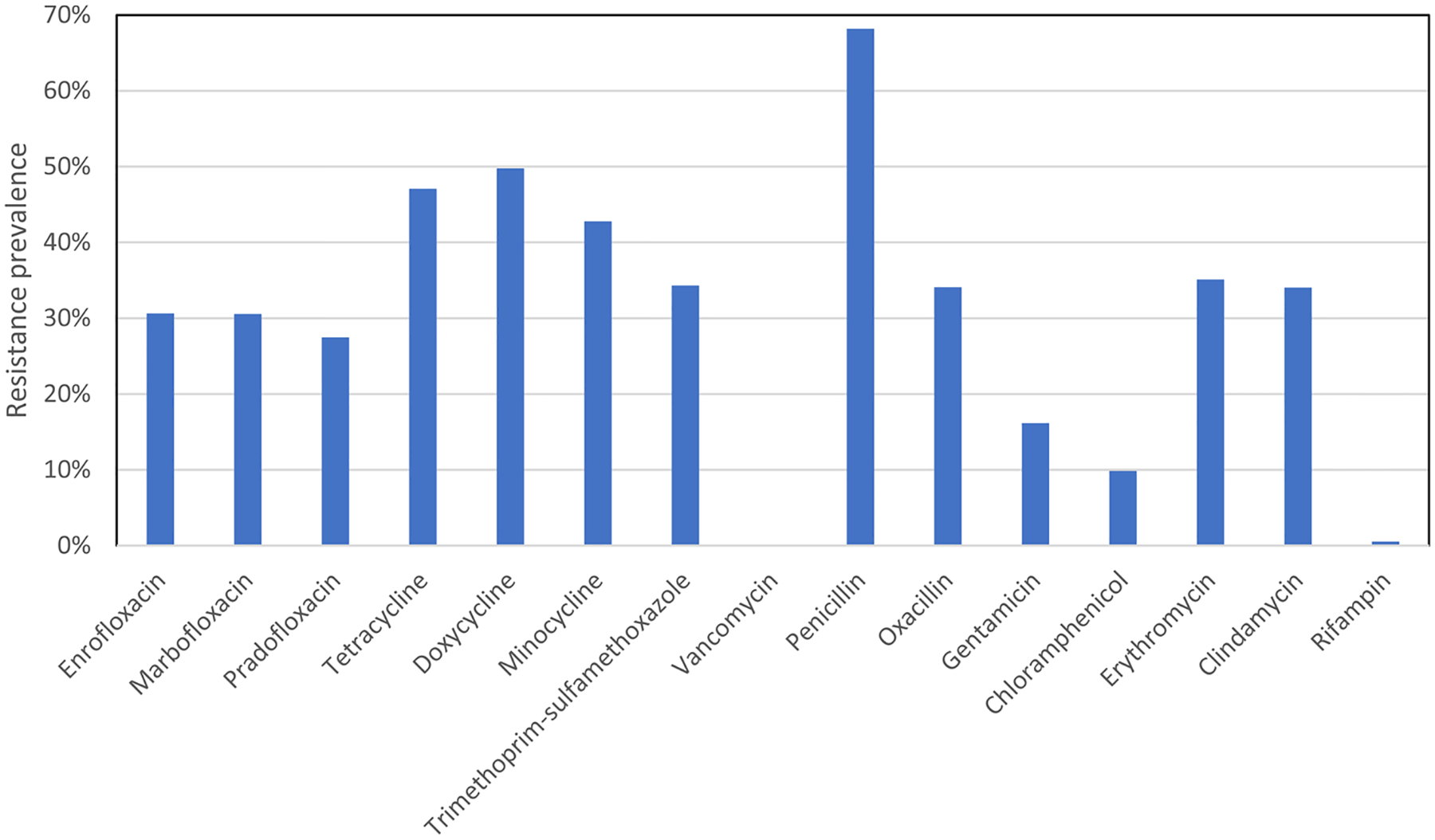

Broth microdilution MIC testing was performed to assess the antimicrobial resistance of 592 S. pseudintermedius isolates collected from dogs in the United States. From data aggregated from Vet-LIRN labs across the United States, the resistance prevalence for these drugs differed significantly, ranging from 0% for vancomycin to 68.2 % for penicillin (Fig. 1). Not every isolate was tested for susceptibility to the same drugs, but there were at least 400 MICs for each of the 15 drugs reported.

Fig. 1.

Resistance prevalence determined by phenotypic testing across fifteen drugs among S. pseudintermedius. Prevalence was based on phenotypic testing. Not every isolate was tested for susceptibility to each drug, which explains some slight differences in resistance prevalence among drugs in the same class. Table 2 shows the number of isolates with MIC data for each drug; see Table S1 for isolate-level details.

WGS was conducted to determine the resistance mechanisms underlying the phenotypes. The most common resistance genes identified included the aminoglycoside resistance genes ant(6)-Ia/aph(3′)-IIIa (35.6 %), the beta-lactam genes blaZ and mecA (74.8 % and 32.3 %, respectively), the macrolide resistance gene erm(B) (34.6 %), and the tetracycline resistance gene tet(M) (45.1 %). Information on the prevalence of all resistance mechanisms is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence of different resistance mechanisms among isolates in the United States.

| Drug class | Mechanism | Number of isolates | Percentage of isolates |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluoroquinolones | GyrA (S84L) | 177 | 29.9% |

| GyrA (S84A) | 1 | 0.2% | |

| GyrA (S84W) | 1 | 0.2% | |

| GyrA (E88G) | 1 | 0.2% | |

| GyrA (E88K) | 1 | 0.2% | |

| GyrA (S84L, S85A) | 1 | 0.2% | |

| GrlA (S80I) | 213 | 36.0% | |

| GrlA (S80R) | 12 | 2.0% | |

| GrlA (D84N) | 8 | 1.4% | |

| GrlA (D84G) | 6 | 1.0% | |

| GrlA (D84Y) | 3 | 0.5% | |

| GrlA (S80I, D84H) | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Tetracyclines | tet(M) | 267 | 45.1 % |

| tet(K) | 11 | 1.9% | |

| Folate synthesis inhibitors | dfrG | 202 | 34.1% |

| dfrC | 3 | 0.5% | |

| Beta-lactams | mecA | 191 | 32.3 % |

| blaZ | 443 | 74.8 % | |

| Phenicols | catA | 52 | 8.8% |

| Macrolides | erm(A) | 1 | 0.2% |

| erm(B) | 205 | 34.6 % | |

| erm(C) | 2 | 0.3% | |

| Ansamycins | RpoB (S486L) | 1 | 0.2% |

| RpoB (H481Y) | 1 | 0.2% | |

| RpoB (Ala after A473) | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Aminoglycosides | aac(6’)-Ie-aph (2”)-Ia | 145 | 24.5% |

| ant(6)-Ia/aph (3’)-IIIa | 211 | 35.6 % | |

| ant(9)-Ia | 1 | 0.2% | |

| Mupirocin | mupA | 3 | 0.5% |

| Lincosamides | lnu(A) | 10 | 1.7% |

| lnu(G) | 2 | 0.3% | |

| Streptothricin | sat4 | 211 | 35.6 % |

3.2. Genotype-phenotype correlations

To perform resistance genotype-phenotype correlations, we compared the resistance phenotypes based on MIC testing with the genotypes identified by the presence of resistance genes and resistance-associated mutations.

Fluoroquinolones tested included enrofloxacin, marbofloxacin, and pradofloxacin. Resistance in staphylococci is typically mediated by mutations resulting in amino acid changes in the target DNA gyrase GyrA, as well as the DNA topoisomerase, GrlA (Gordon et al., 2014). We found that GyrA amino acid changes in the quinolone resistance determining region (QRDR) were associated with fluoroquinolone resistance, with S84L, S84A, S84W, S85A, E88G, and E88K amino acid changes in resistant isolates. Only the S84L and E88G amino acid changes have been reported in S. pseudintermedius (Descloux et al., 2008; Kizerwetter-Swida et al., 2016; Wegener et al., 2018), although the other amino acid changes have been found in S. aureus (Fitzgibbon et al., 1998; Ito et al., 2003; Strahilevitz and Hooper, 2005).

Every isolate with GyrA amino acid changes also had GrlA amino acid changes, including S80I, S80R, D84N, D84G, D84Y, and D84H in GrlA (Table 1). These may be necessary for resistance to pradofloxacin, as this is a dual target drug (Wetzstein, 2005). There were also 45 isolates with only QRDR GrlA amino acid changes, but they were not sufficient to confer clinical resistance. Potential slight elevations in MICs from GrlA amino acid changes could not be assessed (Haenni et al., 2020), due to limited MIC ranges on our testing panels. Overall resistance genotypes and phenotypes correlated 98.9 % (1624/1642) of the time for fluoroquinolones (Table 2). Correlations were somewhat lower for pradofloxacin at 97.6 % (451/463), since five of seven isolates with an MIC of 1 μg/mL were labeled as susceptible but had amino acid changed in GyrA.

Table 2.

Genotype-phenotype correlations among S. pseudintermedius for thirteen drugs.

| Drug | Phenotype: susceptible | Phenotype: resistant | Correlation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype: R | Genotype: S | Genotype: R | Genotype: S | ||

| Enrofloxacin | 2 | 408 | 179 | 2 | 99.3% |

| Marbofloxacin | 2 | 407 | 179 | 1 | 99.5 % |

| Pradofloxacin | 8 | 327 | 124 | 3 | 97.6 % |

| Tetracycline | 4 | 248 | 213 | 11 | 96.8 % |

| Doxycycline | 5 | 202 | 197 | 8 | 96.8 % |

| Minocycline | 8 | 262 | 195 | 7 | 96.8 % |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | 7 | 374 | 195 | 4 | 98.1 % |

| Vancomycin | 0 | 470 | 0 | 0 | 100.0% |

| Oxacillin | 5 | 374 | 184 | 12 | 97.0 % |

| Chloramphenicol | 1 | 530 | 51 | 7 | 98.6 % |

| Erythromycin | 3 | 370 | 198 | 4 | 98.8 % |

| Clindamycin | 7 | 371 | 192 | 3 | 98.3 % |

| Rifampin | 0 | 552 | 3 | 0 | 100.0% |

| Total | 52 | 4895 | 1910 | 62 | 98.4 % |

R: resistant, S: susceptible.

Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was the sole folate synthesis inhibitor tested. A total of 202 isolates had dfrG genes, with three isolates having dfrC. No other dfr genes were detected, resulting in a genotype-phenotype correlation of 98.1 % (569/580). Although these genes only confer resistance to trimethoprim, their presence was sufficient to predict resistance phenotypes to the combination drug trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Mutations in folP have previously been associated with sulfonamide resistance in staphylococci, however the previously reported F17L, S18L, and T51M amino acid changes in FolP were not found (Griffith et al., 2018). There was, however, a four amino acid insertion of EEVT after T59 in FolP found in 396 of 592 isolates (66.9 %), and it was present in all but one isolate with dfr genes. The isolate without the insertion was susceptible to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, indicating the possibility that alterations of folP play a role in resistance to sulfonamides and therefore the combination drug.

Many genes are associated with phenicol resistance in Gram-positive organisms, including fexA, catA, optrA, and cfr, among others. Only catA was detected among isolates in our collection, resulting in a 98.6 % (581/589) genotype-phenotype correlation for chloramphenicol.

For beta-lactams, the known resistance genes in staphylococci include mecA and blaZ. The mecA gene was found in 191 of the 592 isolates (32.3 %), indicating MRSP was common. The presence of mecA correlated well with oxacillin resistance, as expected, at 97.0 % (558/575). Surprisingly, there were 12 isolates that were resistant to oxacillin without mecA or mecC present. None of the isolates without mecA possessed any other regulatory mec genes, including mecI or mecR alleles.

Penicillin is not typically used clinically for treatment of infections caused by staphylococci, but blaZ correlates with resistance to penicillins in S. aureus based on the presence of blaZ (Gordon et al., 2014). A total of 99.5 % (188/189) of isolates with mecA were penicillin-resistant, which is consistent with reporting mecA-positive isolates as resistant to all beta-lactams. Among the remaining isolates, the presence of blaZ did not fully account for the penicillin resistance phenotypes. This is because blaZ was present in 88.0 % (184/209) of the non-mecA penicillin-resistant isolates, but also in 42.4 % (78/184) of the susceptible ones (Table S1). The presence of blaZ in phenotypically susceptible isolates is not surprising, however, as penicillinase testing is recommended for Staphylococcus spp. that test susceptible to penicillins (Kaase et al., 2008). We did additional analysis of amino acid changes in PBP2 and PBP4, as mutations in the associated genes can confer beta-lactam resistance in staphylococci (da Costa et al., 2018; Hackbarth et al., 1995), but this could not account for resistance in isolates lacking blaZ. Overall, we did not calculate resistance genotype-phenotype correlations for this drug due to our inability to accurately predict resistance.

All isolates were vancomycin-susceptible, and none had van genes, which are typically responsible for vancomycin resistance (Werner et al., 2008).

Rifampin resistance is mediated by mutations in rpoB in staphylococci (Kadlec et al., 2011). There were only three resistant isolates, and all had rpoB mutations, with none found in susceptible isolates. Two isolates had previously known S486L and H481Y amino acid changes in RpoB, while one had a three nucleotide insertion encoding an alanine after A473. This mechanism has not been previously reported and is a new insertional rpoB mutation.

Aminoglycoside resistance is typically conferred by aminoglycoside modifying enzymes. A total of 145 isolates had the bifunctional aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia gene, which should confer resistance to gentamicin based on prior work in S. aureus (Gordon et al., 2014). This gene was found in 57 of 95 (60.0 %) gentamicin-resistant isolates, but also in 86 of 493 (17.4 %) susceptible isolates. Given these discordant results, no correlations were calculated for this drug. Several additional aminoglycoside resistance genes were identified (Table 1), but these are expected to confer resistance to aminoglycosides other than gentamicin (Shaw et al., 1993).

Tetracycline drugs in this study included tetracycline, doxycycline, and minocycline. Resistance to this drug class is typically conferred by tet genes, and we identified 267 isolates with tet(M) and 11 with tet(K) (which does not confer minocycline resistance). All isolates with tet(K) also had tet(M) genes. Genotypes and phenotypes overall correlated 96.8 % of the time (1317/1360) for the tetracyclines (Table 2). Three of five isolates with an MIC of 1 μg/mL (phenotypically susceptible) for minocycline had tet(M) genes.

Erythromycin and clindamycin were the macrolide and lincosamide drugs in this study, respectively. For these drugs, erm genes are the predominant resistance mechanisms known in Gram-positive organisms. The most common gene was erm(B), in 205 isolates, with one isolate with erm(A) and two with erm(C). Correlations were 98.3 % (563/573) for clindamycin and 98.8 % (568/575) for erythromycin (Table 2). Both isolates with MICs of 4 μg/mL for erythromycin (phenotypically susceptible) had erm genes. We did not see significant evidence for inducible clindamycin resistance based on comparison of erythromycin and clindamycin phenotypes (Table S1), although this can occur with erm genes (Moosavian et al., 2014).

Some additional resistance genes were identified that did not confer resistance to drugs tested phenotypically. These included lincomycin (lnu(A), lnu(G)), mupirocin (mupA), and streptothricin (sat4) resistance genes (Table 1). The identification of mupA in three isolates was of interest since mupirocin can be used as a topical treatment of S. pseudintermedius and resistance is rare (Godbeer et al., 2014).

3.3. Additional genomics analyses

The isolates in this study were diverse, since 494 of the 592 isolates were not in clusters based on single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the NCBI Pathogen Detection Isolates Browser (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/isolates, accessed April 10, 2020). This means among those 494 isolates, none were within 50 SNPs of each other or any other public S. pseudintermedius sequences. The remaining 98 isolates were in 32 SNP clusters with a maximum of 12 isolates, indicating no large clonal clusters accounted for a large proportion of the isolates in our study (Table S1). These findings were confirmed by in silico multilocus sequence typing (MLST), which identified 99 different sequence types, with the most common being ST181 (5.6 % of isolates), ST155 (2.9 %), and ST551 (2.4 %). Most isolates (58.3 %, 345/592) were not assigned a known sequence type, further illustrating the isolate diversity.

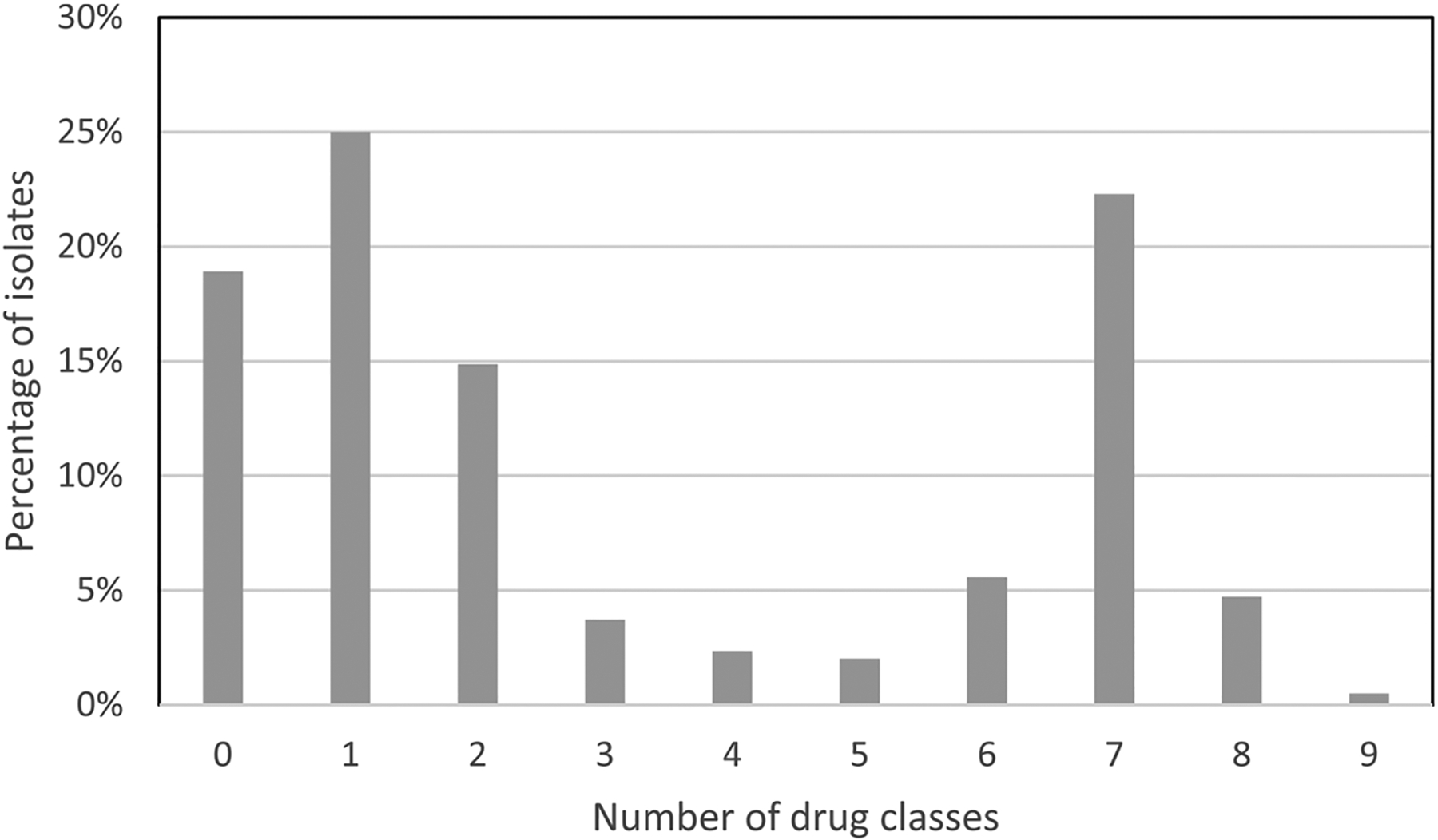

There were 74 different combinations of resistance genes present in the 592 isolates, indicating substantial diversity of resistance gene content in the samples (Table S1). In total, 17 different resistance genes were identified, in addition to various resistance-associated mutations (Table 1). Isolates typically had either few resistance genes or many, as most isolates had resistance mechanisms for zero to two drug classes (58.8 %) or six to eight drug classes (32.6 %) (Fig. 2). This largely reflects the distribution of isolates into those with and without mecA.

Fig. 2.

Prevalence of resistance genes by number of drug classes for individual isolates. The number of drug classes refers to all drug classes for which we had resistance mechanisms (Table 1). All isolates had resistance genes and mutations expected to confer resistance for zero to nine drug classes.

We performed WGS for an additional 41 isolates from Canada, for which we did not have MIC data. The same resistance genes were most common in these isolates as in the rest of the collection, including blaZ, mecA, ant(6)-Ia/aph(3′)-IIIa, erm(B), and tet(M) (Table S1). Combined with the rest of the data, these indicate similarity in the types of resistance genes found in S. pseudintermedius across the United States and Canada.

4. Discussion

Over the last decade, WGS has revolutionized our understanding of microbiology and antimicrobial resistance. We have gained a great understanding of resistance mechanisms in diverse bacterial species and how those mechanisms correlate with phenotypic measures of resistance. However, genomics work in veterinary pathogens has been limited.

This manuscript describes an important advance in the use of genomics to understand antimicrobial resistance of veterinary pathogens. With 633 whole-genome sequences (592 of which had MIC data, all from the United States), this is the largest sequenced collection of S. pseudintermedius ever reported. The isolates were derived from thirty sites across North America making this collection not only the largest but also a geographically diverse collection. In addition, the identification of diverse resistance genes and mutational mechanisms, including a novel rpoB mutation, help aid future work to understand antimicrobial resistance in this important pathogen.

The bacterial isolates in this study represented diverse lineages based on SNP analyses, with seventeen different resistance genes identified. This diversity likely reflects the fact that S. pseudintermedius is widely distributed and a common resident of the skin and mucosal surfaces of most healthy dogs. Nevertheless, there were certain common combinations of resistance genes. For instance, all 52 isolates with catA genes also had erm(B). In addition, among 191 isolates with mecA, 89 had all the following genes: aac(6′)-Ie-aph(2″)-Ia, ant(6)-Ia/aph(3′)-IIIa, erm (B), blaZ, tet(M), and dfrG. This is important because this combination of genes results in resistance to several drug classes, potentially compromising treatment. In contrast, only nine isolates without mecA had all those genes. Unfortunately, based on the limitations of short-read sequencing, we could not further characterize potential genetic link-ages between resistance genes. Further work with long-read sequencing is planned to help uncover the genomic context for these findings.

The finding of such a high proportion of isolates with mecA was surprising and concerning. However, it is important to note that the resistance prevalence estimates may overstate the general prevalence of AMR in S. pseudintermedius. This is because infections that responded favorably to empiric therapy were less likely to be submitted to the diagnostic laboratories for subsequent antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Overall, 98.4 % (6805/6919) of resistance genotypes correlated with phenotypes, indicating that WGS may become a reasonable proxy for identifying antimicrobial resistance in S. pseudintermedius. Of concern is that 54.4 % (62/114) of genotype-phenotype discrepancies result from ‘very major errors’ in which isolates were phenotypically resistant but were predicted to be susceptible by their resistance genotypes. These are of greater concern for any potential future application of genomics technologies to clinical cases and indicate some potential remaining data gaps, further confirming the continued value of phenotypic testing.

Interestingly, if breakpoints were one dilution lower for some drugs, most notably pradofloxacin, minocycline, and erythromycin, then genotype-phenotype correlations would have improved. These results do not necessarily mean that clinical breakpoints should be changed, however, as they are derived from pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies and may not correspond exactly with genotypic data. The use of epidemiological cutoff values to correlate with resistance genotypes may result in better correlations, although unfortunately no such cutoff values exist for S. pseudintermedius. The use of alternative interpretive criteria has been done before in some other pathogens, such as S. enterica, where genotypic cutoff values have been developed (Tyson et al., 2017). Overall, this work shows the power and promise of using WGS for detecting antimicrobial resistance in S. pseudintermedius. In addition to largely providing the same interpretations of resistant and susceptible as traditional phenotypic testing, from WGS we gain valuable additional information about the underlying resistance mechanisms and relatedness of isolates to one another.

One limitation was the inability to correlate resistance genotypes with phenotypes for penicillin and gentamicin. A lack of known resistance mechanisms for these drugs is a remaining knowledge gap where we cannot directly apply information from S. aureus or other published studies. Additional issues may include that the current breakpoints are too high, as EUCAST uses a lower gentamicin breakpoint of > 1 μg/mL, compared to ≥ 16 μg/mL for CLSI. The data also support the use of beta-lactamase tests in penicillin-susceptible isolates, since blaZ may be present in some isolates that test susceptible (CLSI, 2018a). One opportunity for further work is to apply machine learning technologies to identify any additional relevant genetic markers for penicillin or gentamicin resistance, as has been done successfully in both Klebsiella pneumoniae and S. enterica (Nguyen et al., 2018, 2019). Additional work incorporating clinical data, such as drug treatment choice, duration, and outcome, would also greatly expand the utility of genomic data for antimicrobial resistance prediction. However, significant public and private investment must be made in order to support collection of this information.

Vet-LIRN will continue to perform susceptibility testing and WGS of veterinary pathogens to understand the spread of AMR, investigate emerging resistance, and further our understanding of the overall genetic structure of veterinary pathogens. This work also highlights the importance of collaboration across laboratories, states, and countries, demonstrating the critical value of a network approach in assessing antimicrobial resistance. This is an important component of a One Health system to evaluate the public health impact of antimicrobial resistance and monitor its spread among bacteria in animals and humans.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Jill Johnson, Brooke Adams, Teresa Register, Danielle Kenne, the Bacteria K State Group, Hannah Rawza, Tamara Gull, Jesse Bowman, Jana Morgan, Megan Fauls, Jasmin Huang, Leah Scarborough, Gianna Goldman, Megan Cleary, Noah Allen, Christian Holcomb, Donna Krouse, the members of the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of the Texas A&M Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital, Daniel Bradway, Tim Baszler, Rachel Olson, and Marla Francis. This work was supported by FDA Vet-LIRN grants 1U18FD006453, 5U18FD006180, 1U18FD006460-01, 5U18FD006670-02, 1U18FD006562, 1U18FD006862, 5U18FD006172, 5U18FD006157, 5U18FD006173, 5U18FD006667-02, AWD00007382, 5U18FD006245, U18FD006175A, 1U18FD006593-01, U18-FD-006713, 1U18FD004849-01, 1U18FD006164, 1U18FD006671, 1U18FD006673-01, 5U18FD006156, 5U18FD006160-02, 5U18FD006170-04, 5U18FD006179, 5U18FD006377, 5U18FD006378, 5U18FD006379, 1U18FD006567, U18FD006171, U18FD005164, U18FD006151, U18FD006181, U18FD006558, 1U18FD006165-01, 1U18FD0051544, 1U18FD0051544, 3U18FD005144, 1U18FD006716, 5U18FD006379, 3U18FD005144, 1U18FD006716, 1U18FD006448, 1U18FD006567, 5U18FD006379, 5U18FD006155-04, and 5U18FD006712.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or the U.S. Government. Reference to any commercial materials, equipment, or process does not in any way constitute approval, endorsement, or recommendation by the Food and Drug Administration.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2021.109006.

References

- Bannoehr J, Guardabassi L, 2012. Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in the dog: taxonomy, diagnostics, ecology, epidemiology and pathogenicity. Vet. Dermatol 23 (253–266), e251–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau LD, Rubin JE, Deneer H, Kanthan R, Morrison B, Sanche S, Rypien C, Dueck D, Beck G, Blondeau JM, 2020. Persistent infection with Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in an adult oncology patient with transmission from a family dog. J. Chemother 32, 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceric O, Tyson GH, Goodman LB, Mitchell PK, Zhang Y, Prarat M, Cui J, Peak L, Scaria J, Antony L, Thomas M, Nemser SM, Anderson R, Thachil AJ, Franklin-Guild RJ, Slavic D, Bommineni YR, Mohan S, Sanchez S, Wilkes R, Sahin O, Hendrix GK, Lubbers B, Reed D, Jenkins T, Roy A, Paulsen D, Mani R, Olsen K, Pace L, Pulido M, Jacob M, Webb BT, Dasgupta S, Patil A, Ramachandran A, Tewari D, Thirumalapura N, Kelly DJ, Rankin SC, Lawhon SD, Wu J, Burbick CR, Reimschuessel R, 2019. Enhancing the one health initiative by using whole genome sequencing to monitor antimicrobial resistance of animal pathogens: Vet-LIRN collaborative project with veterinary diagnostic laboratories in United States and Canada. BMC Vet. Res 15, 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLSI, 2018a. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated From Animals, 4th edition. In Vet01 supplement (Vet08) (Wayne, PA: ). [Google Scholar]

- CLSI, 2018b. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Disk and Dilution Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria Isolated From Animals, 5th ed. CLSI standard VET01 (Wayne, PA.). [Google Scholar]

- Cole SD, Peak L, Tyson GH, Reimschuessel R, Ceric O, Rankin SC, 2020. New Delhi Metallo-beta-Lactamase-5-Producing Escherichia coli in companion animals, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 26, 381–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa TM, de Oliveira CR, Chambers HF, Chatterjee SS, 2018. PBP4: a new perspective on Staphylococcus aureus beta-lactam resistance. Microorganisms 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Descloux S, Rossano A, Perreten V, 2008. Characterization of new staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec (SCCmec) and topoisomerase genes in fluoroquinolone- and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J. Clin. Microbiol 46, 1818–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldgarden M, Brover V, Haft DH, Prasad AB, Slotta DJ, Tolstoy I, Tyson GH, Zhao S, Hsu CH, McDermott PF, Tadesse DA, Morales C, Simmons M, Tillman G, Wasilenko J, Folster JP, Klimke W, 2019. Validating the AMRFinder tool and resistance gene database by using antimicrobial resistance genotype-phenotype correlations in a collection of isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbon JE, John JF, Delucia JL, Dubin DT, 1998. Topoisomerase mutations in trovafloxacin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 42, 2122–2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godbeer SM, Gold RM, Lawhon SD, 2014. Prevalence of mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J. Clin. Microbiol 52, 1250–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon NC, Price JR, Cole K, Everitt R, Morgan M, Finney J, Kearns AM, Pichon B, Young B, Wilson DJ, Llewelyn MJ, Paul J, Peto TE, Crook DW, Walker AS, Golubchik T, 2014. Prediction of Staphylococcus aureus antimicrobial resistance by whole-genome sequencing. J. Clin. Microbiol 52, 1182–1191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith EC, Wallace MJ, Wu Y, Kumar G, Gajewski S, Jackson P, Phelps GA, Zheng Z, Rock CO, Lee RE, White SW, 2018. The structural and functional basis for recurring sulfa drug resistance mutations in Staphylococcus aureus dihydropteroate synthase. Front. Microbiol 9, 1369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hackbarth CJ, Kocagoz T, Kocagoz S, Chambers HF, 1995. Point mutations in Staphylococcus aureus PBP 2 gene affect penicillin-binding kinetics and are associated with resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 39, 103–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenni M, El Garch F, Miossec C, Madec J-Y, Hocquet D, Valot B, 2020. High genetic diversity among methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in dogs in Europe. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist 21, 57–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Okuma K, Ma XX, Yuzawa H, Hiramatsu K, 2003. Insights on antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus from its whole genome: genomic island SCC. Drug Resist. Updat 6, 41–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaase M, Lenga S, Friedrich S, Szabados F, Sakinc T, Kleine B, Gatermann SG, 2008. Comparison of phenotypic methods for penicillinase detection in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect 14, 614–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadlec K, van Duijkeren E, Wagenaar JA, Schwarz S, 2011. Molecular basis of rifampicin resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from dogs. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 66, 1236–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kizerwetter-Swida M, Chrobak-Chmiel D, Rzewuska M, Binek M, 2016. Resistance of canine methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius strains to pradofloxacin. J. Vet. Diagn. Invest 28, 514–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, Friis C, Hasman H, Marvig RL, Jelsbak L, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Ussery DW, Aarestrup FM, Lund O, 2012. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J. Clin. Microbiol 50, 1355–1361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little SV, Bryan LK, Hillhouse AE, Cohen ND, Lawhon SD, 2019. Characterization of agr groups of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius isolates from dogs in Texas. mSphere 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott PF, Tyson GH, Kabera C, Chen Y, Li C, Folster JP, Ayers SL, Lam C, Tate HP, Zhao S, 2016. Whole-genome sequencing for detecting antimicrobial resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonella. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 60, 5515–5520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosavian M, Shoja S, Rostami S, Torabipour M, Farshadzadeh Z, 2014. Inducible clindamycin resistance in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus due to erm genes. Iran. Iran J Microbiol 6, 421–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M, Brettin T, Long SW, Musser JM, Olsen RJ, Olson R, Shukla M, Stevens RL, Xia F, Yoo H, Davis JJ, 2018. Developing an in silico minimum inhibitory concentration panel test for Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sci. Rep 8, 421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen M, Long SW, McDermott PF, Olsen RJ, Olson R, Stevens RL, Tyson GH, Zhao S, Davis JJ, 2019. Using machine learning to predict antimicrobial MICs and associated genomic features for nontyphoidal Salmonella. J. Clin. Microbiol 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreten V, Kadlec K, Schwarz S, Grönlund Andersson U, Finn M, Greko C, Moodley A, Kania SA, Frank LA, Bemis DA, Franco A, Iurescia M, Battisti A, Duim B, Wagenaar JA, van Duijkeren E, Weese JS, Fitzgerald JR, Rossano A, Guardabassi L, 2010. Clonal spread of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in Europe and North America: an international multicentre study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 65, 1145–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qekwana DN, Oguttu JW, Sithole F, Odoi A, 2017. Burden and predictors of Staphylococcus aureus and S. Pseudintermedius infections among dogs presented at an academic veterinary hospital in South Africa (2007–2012). PeerJ 5, e3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw KJ, Rather PN, Hare RS, Miller GH, 1993. Molecular genetics of aminoglycoside resistance genes and familial relationships of the aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes. Microbiol. Rev 57, 138–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JT, Amador S, McGonagle CJ, Needle D, Gibson R, Andam CP, 2020. Population genomics of Staphylococcus pseudintermedius in companion animals in the United States. Commun. Biol 3, 282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strahilevitz J, Hooper DC, 2005. Dual targeting of topoisomerase IV and gyrase to reduce mutant selection: direct testing of the paradigm by using WCK-1734, a new fluoroquinolone, and ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 49, 1949–1956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson GH, McDermott PF, Li C, Chen Y, Tadesse DA, Mukherjee S, Bodeis-Jones S, Kabera C, Gaines SA, Loneragan GH, Edrington TS, Torrence M, Harhay DM, Zhao S, 2015. WGS accurately predicts antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 70, 2763–2769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson GH, Zhao S, Li C, Ayers S, Sabo JL, Lam C, Miller RA, McDermott PF, 2017. Establishing genotypic cutoff values to measure antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson GH, Li C, Ceric O, Reimschuessel R, Cole S, Peak L, Rankin SC, 2019. Complete genome sequence of a carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli isolate with blaNDM-5 from a dog in the United States. Microbiol. Res. Announc 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Duijkeren E, Catry B, Greko C, Moreno MA, Pomba MC, Pyörälä S, Ruzauskas M, Sanders P, Threlfall EJ, Torren-Edo J, Törneke K, 2011. Review on methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 66, 2705–2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther B, Tedin K, Lübke-Becker A, 2017. Multidrug-resistant opportunistic pathogens challenging veterinary infection control. Vet. Microbiol 200, 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegener A, Broens EM, Zomer A, Spaninks M, Wagenaar JA, Duim B, 2018. Comparative genomics of phenotypic antimicrobial resistances in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus pseudintermedius of canine origin. Vet. Microbiol 225, 125–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner G, Strommenger B, Witte W, 2008. Acquired vancomycin resistance in clinically relevant pathogens. Future Microbiol. 3, 547–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetzstein HG, 2005. Comparative mutant prevention concentrations of pradofloxacin and other veterinary fluoroquinolones indicate differing potentials in preventing selection of resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother 49, 4166–4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witney AA, Cosgrove CA, Arnold A, Hinds J, Stoker NG, Butcher PD, 2016. Clinical use of whole genome sequencing for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. BMC Med. 14, 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, Vestergaard M, Rasmussen S, Lund O, Aarestrup FM, Larsen MV, 2012. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother 67, 2640–2644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.