Abstract

The Duke University Clinical and Translational Science Institute Community Engaged Research Initiative (CERI) created an e-Library in 2018. This e-Library was developed in response to requests from academic researchers and the community for reliable, easily accessible information about community-engaged research approaches and concepts. It was vetted by internal and external partners. The e-Library’s goal is to compile and organize nationally relevant community-engaged research resources to build bi-directional capacity between diverse community collaborators and the academic research community. Key elements of the e-Library’s development included a selection of LibGuides as the platform; iterative community input; adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic; and modification of this resource as needs grow and change.

Introduction

An e-Library, an electronic or digital library, is a collection of topical or reference materials, including resources that can only be accessed digitally (i.e., through subscriptions, hyperlinks, or e-books), and those scanned from hard copies.1 An e-Library is designed to be accessed electronically either online, over the internet (e.g., website), or through other non-networked technologies (e.g., information kiosks).2 They are often more easily accessible to a wider array of remote or community users and can be utilized with minimal or no support from librarians or other service providers.3 An e-Library can be updated and organized frequently and by multiple contributors, reduce the cost of maintaining physical resources, and allow institutions and communities to collaborate from anywhere in the world.4

In the context of community-engaged research, an e-Library is a novel and innovative tool to disseminate research information and to build capacity.5 Community-engaged research (CEnR) is defined as a process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting their well-being.6 It empowers community members to be involved in setting research priorities, as well as building relationships among researchers and community members to better achieve research aims and improve real-world implementation.7 The CEnR approach expedites new innovations in health equity, population health, and other research by prioritizing multi-stakeholder cooperation, especially among historically underrepresented groups.8

CEnR requires intentionality in the dissemination of information that is easily accessible by the community to promote these innovations.9 Information is a valuable resource and can increase researcher and community knowledge and capacity, including their understanding of and ability to engage in CEnR.10 Dissemination of information easily accessible by many individuals makes e-libraries such an attractive option for sharing information regarding community-engaged research. Libraries play a special role in the creation of CEnR resources, as well as facilitating researcher-community relationships; they are institutions that are by their nature interdisciplinary and stakeholder-engaged.

An e-Library can be created using a variety of software or database programs. LibGuides, proprietary software produced by Springshare and marketed to Duke and public libraries since 2008, has traditionally been used within educational settings, serving as topic and course guides for Duke students.11 Because LibGuides is easy to use and widely available,12 the format can also be adapted to organize electronic resources,13 for community-oriented training and education,14 and has even been used as part of social justice movements15 and emergency response strategies.16 Although alternative platforms exist, such as Weebly, LibGuides is the overwhelming choice of academic and community libraries in the United States and beyond.17 Given its adaptability for use within both academic and community settings, LibGuides can: organize and present information to a variety of audiences18 and be updated frequently; be created collaboratively; and can include both academic- and community-related content.19 The creation of e-libraries to address the need to share content related to community-engaged research that is developed collaboratively and that includes the voices of academic and community voices is not the norm, to our knowledge.

In this article, we share key elements of the development of an e-Library used to facilitate community-engaged research capacity building. We address the following: the rationale, selection, and use of LibGuides software; iterative community input regarding content and structure; adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic; and modification of this living resource as organizational and client needs grow and change. We also address the implications of this case study for other institutions and future directions for research.

Rationale for an e-Library Focused on Community-Engaged Research

Duke CTSI’s Community Engaged Research Initiative (CERI) was established in 2016. CERI’s purpose is to: provide programs and tools to enable community-engaged research (CEnR) and spur collaborations and innovations; enhance local, regional, and national capacity for community-engaged research; and improve knowledge and information sharing to foster trust and transparency in research.

CERI staff and faculty conduct CEnR consultations with researchers and work closely with community-based organizations and coalitions with the overall goal of facilitating bi-directional capacity building with academic and community partners. During consultations, staff wanted to be able to find and share CEnR resources quickly with stakeholders. This need increased after receiving feedback from clients and collaborators, including community members, stating that they did not know where to look for, nor did they have access to, the information needed to be able to work effectively with academic research partners. Barriers for community members included being unable to access materials and having little awareness of free resources (e.g., PubMed Central). At the same time, academic researchers from within the institution also sought a single site to obtain trusted, high-level CEnR information to enhance their skills and knowledge of best practices in participatory approaches. Barriers for academic researchers included a lack of expertise regarding community engagement practice and methods, and limited knowledge of trusted resources. Therefore, CERI was motivated to identify and organize available resources to serve both client populations, and to support staff and faculty working with researchers and community members.

Initial e-Library Development

Before the e-Library’s development in 2018, the team had compiled and stored a list of forty trusted sources of CEnR information in an Excel spreadsheet. While brainstorming ways to share this vetted information with academic and community partners, the team envisioned transitioning the spreadsheet to a website format. During planning for this transition, the team sought the advice of a Duke Medical Center librarian to discuss possible solutions and to identify the best platform for the transition from an Excel spreadsheet to a site that would easily be accessible by both community members and academic researchers. This initial consultation resulted in the team choosing LibGuides as the online platform.

There is precedent both within Duke and in the literature of using LibGuides to serve community audiences, in addition to academic institution affiliates.20 Duke LibGuides policy also emphasizes the importance of external utility, which matched CERI’s goal of making a resource repository that would serve academic researchers and lay community members. The Duke Medical Center Library hosts each guide, and CERI’s staff update and maintain the guides through an online account. Guides can be drafted and vetted internally before launch and may be updated in real-time without the need for constant librarian support and oversight. Managing online resources without librarian oversight made a LibGuides-based e-Library ideal as resources could be added and modified promptly in response to community needs.

After determining that resources could be housed in a LibGuide and made available for community members without an institutional affiliation, input was solicited from CERI’s community advisory council and other partner organizations, community leaders, and academic researchers regarding specific resources to include, as well as content, layout, and usability concerns. A preliminary prototype was then presented to CERI’s community advisory council which offered verbal and written feedback during a live feedback session and through an electronic survey. This process informed the architecture of the guide. Including a recommended reading from staff and community partners tab, a “frequently asked questions” section, and a “suggest a resource” form linked on the homepage were among the changes that were suggested and later implemented. The community advisory council also recommended dissemination methods such as linking the e-Library on CERI website and promoting it in CERI’s newsletters and staff email signatures. They also—presciently—warned that too much information is just as “painful” to navigate as too little information.

Resources were organized into tabs that included a landing page about CERI, an introduction to CEnR, and separate tabs for researchers and community members. In response to suggestions from community partners regarding usability, new sections were incorporated: a glossary of terms and acronyms; separate tabs for books, videos, podcasts; and funding opportunities. The intent of this architecture was to segment content for the intended audience to increase the usability and overall utility of the resources. A “Contact Us” tab was also included to encourage users to submit questions about the e-Library content or to participate in any programs or services offered by CERI. Most e-Library resources were developed by other organizations, and as such, they were appropriately hyperlinked and credited.

Adapting to the COVID-19 Pandemic:

Given CERI’s mission and connection to the community, the e-Library was not meant to be a static resource once it was created. Before 2020, the e-Library developed organically with CERI staff and community collaborators frequently making recommendations to incorporate new materials. This process changed rapidly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. In April 2020, in response to the dearth of information, CERI’s community advisory council urged CERI to quickly adapt the e-Library to share trusted and reliable information about the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as relevant community resources. This resulted in a new resource section that included: links to clinical research studies; the most current and reliable epidemiological data on COVID-19 spread; COVID-19 vaccination data; information on COVID-19 prevention; volunteer opportunities to provide food and other essentials to those most severely impacted by the pandemic; and COVID-19 testing and vaccination sites within the county in which Duke is located. The e-Library also listed organizations aiding community members during the pandemic, including housing, food, and employment assistance. The content was organized according to its geographic relevance (national, state, or local), and much of it was available in English and Spanish.

As COVID-19 evolved, CERI sought to once again adapt to the “new normal.” During the pandemic, the number of resources available in the e-Library had grown considerably, from about seventy-five to over 170. Though the resources were separated by topic using tabs, they had outgrown the single LibGuide that comprised the e-Library. Additionally, the necessary focus on the COVID-19-related resource page had hindered the maintenance of community engagement and CEnR resources, leading to many proposed resources and other changes waiting to be internally approved by CERI staff. This was also complicated by the speed at which COVID-related information was changing, leading to a huge burden on staff to maintain and include the most up-to-date and accurate information about the pandemic. Although the guide was used—having 3,067 visits in 2020 and 2,873 in 2021—viewership declined month after the summer of 2021. Additionally, many of its resources were no longer the most up-to-date sources for COVID-19 information locally or nationally.

To make the e-Library more accessible and usable, CERI staff and faculty again consulted with a Medical Center librarian about how best to modify the existing content. The librarian recommended that the e-Library be split into a series of related topical LibGuides. The resulting three LibGuides’ subjects are: What Is Community Engagement; Community-Engaged Research for Researchers; and Community-Engaged Research for Community Members. All three guides, and any future ones, are linked to a simple directory guide that includes the “Suggest a Resource” form. These guides received a combined 1,323 views from January to October 2022, which is impressive given that most views for the old guide came from the COVID-19 resources page. Therefore, it can be assumed that although the views are lower, more people encounter information about CEnR in the revised guides.

Resources displayed in the original e-Library and new resources were reviewed and, if still relevant and suitable, added to the appropriate guide. COVID-19-related resources were relocated to a preexisting Duke Medical Center Library guide of clinical and community COVID-19 resources, which is regularly maintained and directly links to reliable sources of up-to-date information (e.g., Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). Once this process was complete, fifty-five unique resources remained in the e-Library, along with helpful charts and diagrams and a glossary of CEnR terms. Although a natural drift of scope and purpose occurred over time, these revisions to the e-Library represent a pivot back to the original guidance that CERI’s community partners offered when it was initially developed.

To ensure that the e-Library remains a user-friendly and accessible resource for all, a new vetting process was implemented in December 2021, as the revised e-Library was launched. This vetting process included a two-stage review of suggested materials conducted by CERI staff and faculty, as well as the development of guidelines for the inclusion of new materials. Existing materials are now reviewed quarterly by CERI staff and yearly by library staff. All current and future materials must be:

Different from previously posted content

Directly related to the topic of the guide

Free and publicly accessible without institutional access

Layperson-friendly

Housed on a stable, trustworthy website

Ideally five or fewer years old

Credited appropriately in the hyperlinked resource title

These criteria will help ensure that CERI’s e-Library stays true to its mission of providing trusted resources about community engagement and community-engaged research, while emphasizing equity and ensuring public access for both academic and community partners nationwide.

Discussion

Lessons Learned

The e-Library’s success depends, in many ways, on the software used to develop and maintain it. The LibGuides platform helps the e-Library accomplish its goals by:

Increasing access to resources for internal and external users

Having a simple and straightforward layout, so that the software is easy for staff to learn and content can be regularly updated

Allowing content and templates to be reused in multiple tabs or guides

Including the capacity to embed video clips, gallery boxes, book covers, diagrams, or other media to make content stand out

Having the ability to obtain real-time insight into system usage, including hits on guides and individual assets

Being supported by institutional technical support and guidance

Additionally, the LibGuides platform augments CERI’s ability to be responsive to stakeholder and community requests and concerns, and to broaden the impact of these resources regionally and nationally. Without the existence of the e-Library and the quick changes made possible by the LibGuides format, CERI could not have responded as efficiently to stakeholder needs during the pandemic. Moreover, the inclusion of resources developed by other institutions’ Clinical and Translational Science Awards Centers and community-based organizations breaks down the silos between academia and community and among institutions.

Implications for the Field

Through compiling and publicizing the important work being done in community engagement and CEnR across the country, CERI endeavors to lift up the voices of those at the forefront of community engagement implementation and innovation. This has implications for other academic institutions that may want to implement an e-Library to bolster their community engagement efforts. Primarily, developing this resource would mean:

Identifying stakeholders: Does the academic library have a research team, department, or center at the institution that is interested in or conducting CEnR? Is there a relationship, or could there be, among community members and organizations and the institution’s research infrastructure? How can the potential audience be consulted while creating and maintaining the e-Library?

Identifying resource aims: What are the goals of the e-Library (for example, informing, disseminating, making connections among stakeholders)?

Identifying institutional capacity: Are there other resources on campus that could augment a CenR e-Library (for example, a funding program, a community advisory board)? If so, can collaboration among these parties be established?

Libraries establishing a CEnR-related resource should also consider how the traditional values and norms of academic librarianship would be implicated in its creation. For example: Academic centers and libraries collaborating directly to create resources – Traditionally, LibGuides are primarily used in academic libraries as course or subject guides and aimed at students and other institutional members. These guides are usually created and maintained by librarians, who are responsible for managing their content. However, CERI’s e-Library is an example of a resource created collaboratively between an academic center and a Duke library. Maintained by CERI staff, it does not create additional burden for librarians, while also sharing institutional resources interdepartmentally to create a wider variety of content for an expanded user base.

Expanding the definition of a library “user” – Academic libraries are, understandably, most focused on serving the students, faculty, staff, and visitors of their institutions. However, as many universities expand their definition of “community” to include the geographic communities in which they are located, libraries get the opportunity to do the same. This allows them to adapt and expand their resources for new users in the broader community, rather than solely focusing on members of the institution.

Emphasizing free and equitable access to information – Libraries are, at their core, devoted to access to information. However, this information, particularly in academic spaces, is often inaccessible to those without Duke affiliations. Although institutions must be mindful of their capacity to provide expensive resources to non-institutional community members, they can still act as information brokers through e-libraries and other tools. Librarians and academicians can work together to present freely accessible, evidence-based information to users who may not have formal research training and experience. In this way, academic libraries can help further the democratization of information to a wider audience—those who do not have the privilege of being a member of an academic institution.

Limitations

As with any software, LibGuides has limitations that can impact their usability,21 especially for a resource as large as CERI’s e-Library. Additionally, LibGuides’ ease of use can tempt creators into creating more resources than they can realistically maintain, negatively impacting their effectiveness.22 Some such limitations include:

A simple, relatively inflexible layout that has limited capacity for visual appeal

The risk of the e-Library becoming a “dumping ground” if resources are not consistently evaluated, updated, and/or culled

Accessibility concerns, e.g., lack of hyperlink underlining, color contrast, and other tools used by those with visual impairments and other disabilities.23 These must be resolved either with customized code on the part of the host institution, or by Springshare as a back-end solution.24

CERI will address these limitations through continuing to interface with our academic and community stakeholders to improve the e-Library’s visual elements and content. In addition, the implementation of the new resource vetting policy and review schedule will ensure that the e-Library’s content remains publicly accessible, relevant, and easy to navigate for all users. At this time, LibGuide accessibility concerns are in the hands of the Duke Medical Center Library and are not controlled directly by CERI.

Implications for Future Research

Although outreach and engagement are primary missions of libraries and librarians, there is a lack of knowledge regarding how and when academic researcher teams and librarians collaborate to mediate and facilitate community engaged research. More research is needed on how academic libraries can work with other institutional centers, as well as on how departments can not only collaboratively create resources, but also directly facilitate CEnR and other community engagement strategies.

E-libraries, including ones built using LibGuides, are promising but underutilized tools in the community engagement literature, representing an opportunity to prioritize user-friendliness and information accessibility. Such resources could bridge gaps in knowledge between community members and academic partners through a transparent interface, if community members are able to substantively involve themselves in their creation. More research is needed on the effectiveness of e-libraries for community-oriented projects, and how they can best be adapted for community use.

Conclusion

As CERI continues to adapt and respond to the continued need for credible public health research information and increase community engagement—particularly in historically marginalized communities—the e-Library will continue to be a vital first stop for those interested in learning about CEnR. E-libraries and LibGuides both thrive when they are cared for; like relationship between communities and researchers, they need collaboration, coordination, and consistent upkeep in order to remain useful.25 CERI’s e-Library is able to adapt with the times—evolving from a simple spreadsheet, to a trusted way to get local information about the pandemic, to a series of topical guides with the potential to expand to other CERIs across the Duke’s Clinical and Translational Science Awards Center.

FIGURE 1.

A Partial Screenshot of One of the Pages from Ceri’s Original E-Library. As is evident here, many researcher resources are only accessible via institutional login. Each tab in the top of the image leads to a similar page of resources

FIGURE 2.

A Partial Screenshot of CERI’s e-Library’s COVID Information Page. Resources in Spanish are available further down. During the subsequent redesign, community COVID resources were relocated to a preexisting Duke Medical Center Library guide

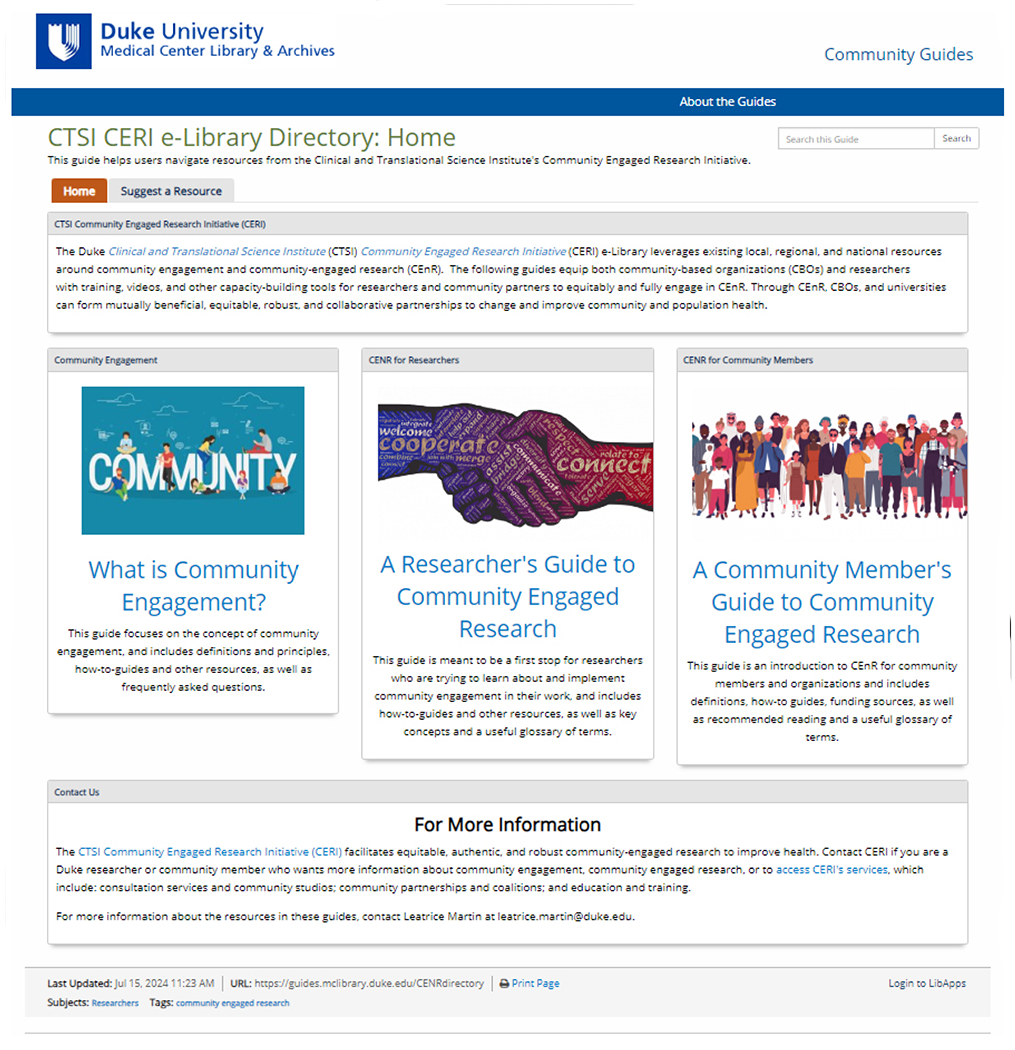

FIGURE 3.

A Screenshot of the Directory Homepage for the New CERI e-Library. Each hyperlinked box leads to a topic-focused guide with vetted, fully publicly accessible resources.

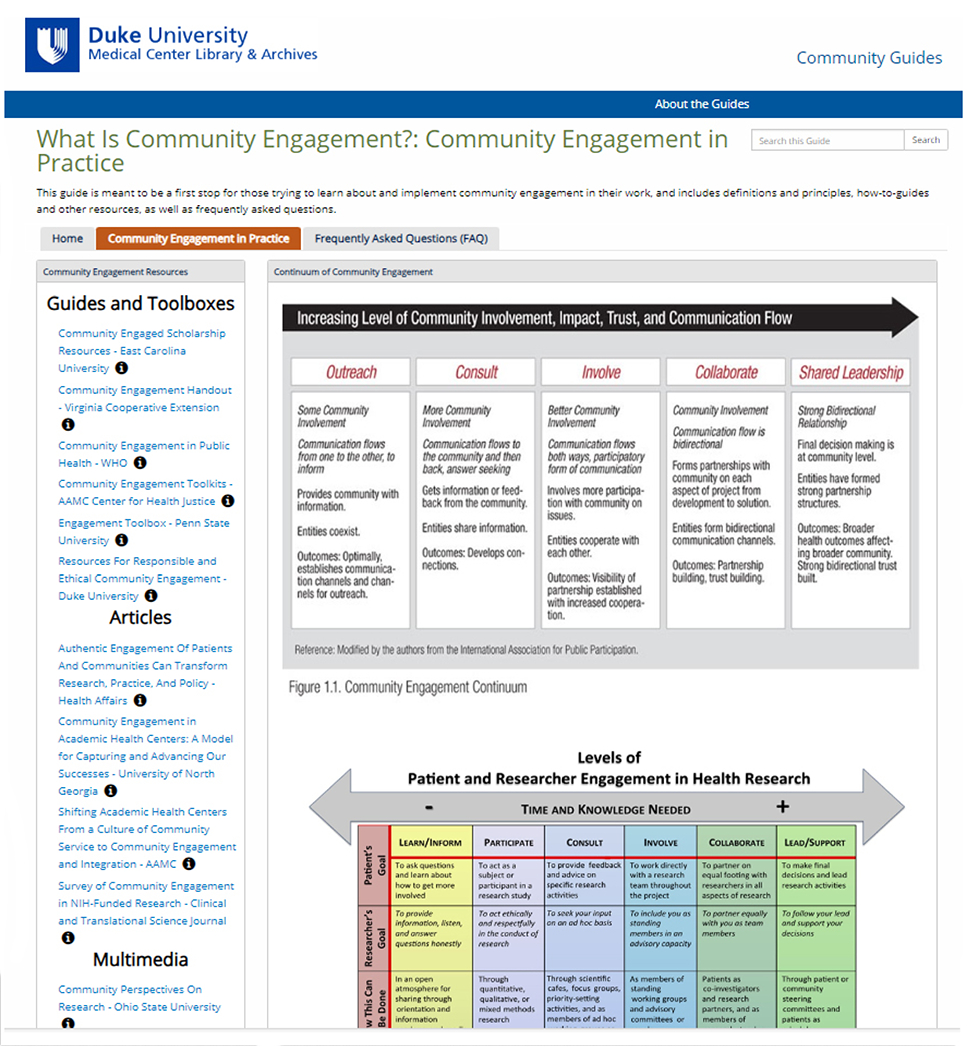

FIGURE 4.

A Screenshot Of One Page Of A New Guide, “What Is Community Engagement?”

Acknowledgements

The authors and the Duke Community Engaged Research Initiative (CERI) would like to acknowledge Brandi Tuttle, Duke Medical Center librarian; Davon Washington, former CERI project coordinator; Dr. Nadine Barrett, former CERI co-director; the rest of CERI’s staff and faculty; the CERI Advisory Council; and NIH CTSA Grant UL1TR002553.

Contributor Information

Lea Efird-Green, Research Program Manager at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Eve Marion, Duke University.

Diane Willis, Duke Department of Pediatrics.

Jennifer M. Gierisch, Duke School of Medicine.

Leonor Corsino, Duke School of Medicine and Department of Population Sciences.

Notes

- 1.Umuloro Immanuel O. and Tiamiyu Mutawakilu A., “Determinants of E-Library Services’ Use Among Duke Students: A Study of John Harris Library, Duke of Benin, Nigeria,” Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 49, no. 4 (2017): 438–453; [Google Scholar]; Sheffer Joseph, “BRIGHT IDEAS: From Disarray to Shipshape: Implementing an E-Library,” Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology 48 no. 4 (2014): 281–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umuloro and Tiamiyu, “Determinants of E-Library Services’ Use,” 440.

- 3.Umuloro and Tiamiyu, “Determinants of E-Library Services’ Use,” 440.

- 4.Sheffer, “BRIGHT IDEAS,” 282.

- 5.Oinam Aruna Chanu and Thoidingjam Purnima, “Impact of Digital Libraries on Information Dissemination,” International Research: Journal of Library and Information Science 9, no. 1 (2019): 78–92. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Principles of Community Engagement. 2. Washington, DC: NIH Publication; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed Syed M. and Palermo Ann-Gel S., “Community Engagement in Research: Frameworks for Education and Peer Review. American Journal of Public Health, 100, no. 8 (2010): 1380–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahmed and Palermo, “Community Engagement in Research,” 1380-1387.

- 9.Michener Lloyd et al. , “Aligning the Goals of Community-Engaged Research: Why and How Academic Health Centers Can Successfully Engage with Communities to Improve Health,” Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 87, no. 3 (2012): 285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmed and Palermo, “Community Engagement in Research,” 1380–1387.

- 11.Gonzalez Alisa C. and Westbrock Theresa, “Reaching out with LibGuides: Establishing a Working Set of Best Practices,” Journal of Library Administration 50, no. 5-6 (2010): 638–656. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erb Rachel A. and Erb Brian, “Leveraging the LibGuides Platform for Electronic Resources Access Assistance,” Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship 26, no. 3 (2014): 170–189. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erb and Erb, “Leveraging the LibGuides,” 170-189;; Ream Tim and Parker-Kelly Darlene, “Expanding Library Services and Instruction through LibGuides. Medical Reference Service Quarterly 35, no. 3 (2016): 342–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuller Tyler J. and Bogue Sarah, “Training for Health Ministry: Design and Implementation of Library Resources to Incorporate Health Education and Promotion into Theological Education,” Teaching Theology & Religion 23, no. 4 (2020), 240–251. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kostelecky Sarah R., “Sharing Community Created Content in Support of Social Justice: The Dakota Access Pipeline LibGuide,” Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication 6 (Special Issue: The Role of Scholarly Communication in a Democratic Society), (2018): eP2234. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazure Emily S., et al. , “Librarian Contributions to a Regional Response in the COVID-19 Pandemic in Western North Carolina,” Medical Reference Services Quarterly 40, no. 1 (2021): 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leibiger Carol A. and Aldrich Alan W., “‘The mother of all LibGuides’: Applying Principles of Communication and Network Theory in LibGuide Design,” Association of College and Research Libraries 2013 Conference Proceedings (2013): 429–441. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Little Jennifer J., et al. , “Interdisciplinary Collaboration: A Faculty Learning Community Creates a Comprehensive LibGuide,” Reference Services Review 38, no. 3 (2010): 431–444. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Little et al., “Interdisciplinary Collaboration,” 431-444; Kostelecky, “Sharing Community Created Content,” eP2234.

- 20.Fuller and Bogue, “Training for Health Ministry,” 243; Kostelecky, “Sharing Community Created Content,” eP2234; Mazure et al., “Librarian Contributions to a Regional Response,” 79-80.

- 21.Leibiger and Aldrich, “‘The Mother of all LibGuides,’” 436-437.

- 22.Leibiger and Aldrich, “‘The Mother of all LibGuides,’” 436-437.

- 23.Greene Katherine, “Accessibility Nuts and Bolts: A Case Study of How a Health Sciences Library Boosted its LibGuide Accessibility SCERI from 60% to 96%,” Serials Review 46, no. 2 (2020): 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greene, “Accessibility Nuts and Bolts,” 125-136.

- 25.Little et al., “Interdisciplinary Collaboration,” 439.