Abstract

Despite research and recommendations supporting shared decision-making and vaginal birth as a reasonable option for appropriately screened candidates with a term breech pregnancy, cesarean remains the only mode of birth available in most hospitals in the United States. Unable to find care for planned vaginal birth in a hospital setting, some individuals choose to pursue breech birth at home, potentially placing themselves and their infants at increased risk. Through this analysis of qualitative data gathered from a mixed methods study, we explored the experience of decision-making of 25 individuals who left the US hospital system to pursue a home breech birth. Data were gathered through open-ended survey responses (n = 25) and subsequent in-depth, semi-structured interviews (n = 23) and analyzed using an interpretive description approach informed by situational analysis. Five interwoven and dynamic themes were identified in this complex decision-making process: valuing and trusting in normal birth, being “backed into a corner,” asserting agency, making an informed choice, and drawing strength from the experience. This study provides a foundation for understanding the experience of decision-making and can inform future research and clinical practice to improve the provision of safe and respectful, person-centered care for breech pregnancy and birth.

1. Introduction

In most pregnancies, the fetus settles into a cephalic (head down) presentation prior to term (by 37 weeks’ gestation). However, in 3–4% of term pregnancies, the fetus is breech, with the buttocks or lower extremities presenting. Because breech presentation is associated with increased risk of complications in vaginal birth compared to cephalic presentation, decisions must be made about attempting interventions to reposition the fetus (such as a manual rotation procedure called external cephalic version [ECV]) and intended mode of birth (i.e., vaginal or cesarean) if breech presentation persists (Hofmeyr, Kulier, & West, 2015; Impey et al., 2017). Decisions about mode and site of birth hold psychological, cultural, emotional, and spiritual importance for many birthing persons and their families (Cheyney, 2008; Declercq et al., 2023; Downe et al., 2018; Larkin et al., 2009; Simkin, 1991). Person-centered care that honors individuals’ agency and autonomy is an essential component of high-quality perinatal care (Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001; Reis et al., 2012; Renfrew et al., 2014; World Health Organization, 2016). A lack of autonomy in childbirth-related decision-making may be perceived as traumatic and is associated with adverse psychological and emotional outcomes as well as alienation from the healthcare system (Beck, 2004; Bohren et al., 2015; Elmir et al., 2010; Hadjigeorgiou et al., 2012; Reed et al., 2017; Vedam et al., 2019). Yet, in the United States, where nearly all breech fetuses (96%) are born via cesarean (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023), pregnant people may have limited opportunities for involvement in decision-making and informed choice for intended mode of breech birth (Schafer et al., 2023).

Cesarean became the recommended mode of birth for term breech fetuses after an international, large-scale, randomized controlled trial (the Term Breech Trial) reported increased risk of perinatal and neonatal mortality and short-term serious neonatal morbidity with planned vaginal birth compared to planned cesarean (Hannah et al., 2000). In the United States, vaginal breech births diminished sharply following publication of this study and an ensuing recommendation from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) that all singleton term breech fetuses should be delivered via planned cesarean (ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2001; Hehir, 2015). The Term Breech Trial has since been widely criticized (Bloomfield, 2005; Glezerman, 2012; Hauth & Cunningham, 2002; Kotaska, 2004; Lawson, 2012; van Roosmalen & Rosendaal, 2002), and subsequent research has demonstrated that although short-term perinatal morbidity and mortality is higher in planned vaginal breech birth than planned cesarean, absolute risk of adverse outcomes is low, with no significant difference in longer-term pediatric outcomes such as death or neuro-developmental delay (Berhan & Haileamlak, 2016; Goffinet et al., 2006; Hofmeyr, Hannah, & Lawrie, 2015; Jennewein et al., 2019; Whyte et al., 2004). Even after ACOG issued a revised statement acknowledging that hospital vaginal breech birth is a “reasonable” option for appropriately screened candidates, vaginal breech births remain quite rare in the United States due to provider inexperience and medicolegal concerns (ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018; Dotters-Katz et al., 2020; Hipsher & Fineberg, 2019).

Individuals who desire a vaginal breech birth have reported difficulties in obtaining care, especially within the US hospital system, leading some to seek care in community birth settings (homes and birth centers) (Coalition for Breech Birth, 2020; Schafer et al., 2023). However, there is international consensus that, when appropriate, vaginal breech birth should occur in a hospital setting attended by a skilled breech provider (ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2018; Impey et al., 2017; Kotaska & Menticoglou, 2019; Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2016; Sentilhes et al., 2020). Due to evidence of increased risk of fetal or neonatal morbidity and mortality in breech births outside of the hospital (16.8/1000, adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 8.2, 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.7 to 18.4) (Bovbjerg et al., 2017), breech presentation is generally considered a contraindication to planned community birth (i.e., home or birth center birth) (ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice, 2017; National Academies of Sciences, 2020). Yet, about one in ten (12%) of all term singleton vaginal breech births in the United States currently occur in community birth settings, a number that has been steadily rising over the past 5 years (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023). Although it has been proposed that a lack of availability of care for planned vaginal breech in US hospitals conceivably makes community birth the only option for persons seeking to avoid surgical birth (Caughey & Cheyney, 2019; Fischbein & Freeze, 2018; Kotaska, 2011), there are no identified studies exploring breech birth decision-making in the United States to support this claim (Morris et al., 2022), and decision-making for home breech birth remains poorly understood. The purpose of this study was to explore the experience of decision-making in individuals who transferred out of the hospital system to pursue home breech birth.

2. Method

2.1. Design

This article presents qualitative findings from a mixed methods study (described in a previous publication [Schafer et al., 2023]) that used an explanatory, sequential design (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2018). After completing an eligibility screen, participants completed an online survey that collected both quantitative and qualitative data about the experience of decision-making surrounding leaving the hospital system to pursue a home breech birth. Participants were then invited to participate in in-depth, semi-structured interviews. Quantitative data from the survey were used to inform interview questions, and qualitative data were used to explore, expand upon, and contextualize quantitative responses. For qualitative analysis, an interpretive description approach informed by situational analysis was used to explore subjective perspectives and the interrelationships of key situational elements to generate knowledge that could inform clinical application (Clarke et al., 2018; Thorne, 2016).

2.2. Sample

The target population for this study was individuals who transferred out of hospital-based care to pursue a home breech birth in the US in the last 5 years. Over a period of six months (February to August 2021), participants were recruited through purposive, convenience, and snowball sampling methods by sharing study information with administrators of targeted social media sites, leaders of birth-related advocacy and professional organizations, and identified expert breech birth providers (Walker et al., 2016a, Walker et al., 2016b). Individuals who were 18 years of age or older, not pregnant, received prenatal care in the US in their third trimester of pregnancy with a singleton breech fetus within 5 years of enrollment, and had intended to give birth in the hospital and then made the decision pursue home breech birth were invited to participate, irrespective of birth outcomes. Recruitment was closed once theoretical saturation had been achieved (Clarke et al., 2018; Sandelowski, 1995).

2.3. Ethics

This study was approved by Vanderbilt University’s Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained in writing upon study enrollment and reaffirmed verbally at the onset of the interview. At the conclusion of the interview, participants received a $50 electronic gift card in compensation for their time.

2.4. Theoretical frameworks

Three interrelated theoretical frameworks of ethics of care, feminist theory, and the social model of care informed this study and framed the researchers’ disciplinary orientation and personal positions in the field of inquiry. From a foundation of ethics of care, identity and agency were understood to be deeply embedded in relationships and environments and shaped by complex social determinants (Newnham & Kirkham, 2019; Noseworthy et al., 2013; Sherwin, 1998). As such, familial, cultural, institutional, and sociopolitical contexts and relationships were considered essential aspects of decision-making. Decision-making includes both psychological and microsocial aspects, such as patient-provider interactions, cognitive and information processing, and individuals’ feelings and views about their role, effort, and contributions (Entwistle & Watt, 2006; Noseworthy et al., 2013). Through the lens of feminist theory, decision-making exists within sociocultural constructs of risk, sociopolitical contexts, and cultural and gendered narratives related to the management and control of the female and childbearing body (Davis-Floyd, 1994; Mackenzie & Stoljar, 2000). The social model of care frames the holistic interpretation of risk employed in this study, appreciating that risk is subjective, exists on multiple levels, and extends beyond adverse biomedical outcomes to include threats to psychological and emotional well-being, dignity, bodily integrity, and agency (Chadwick & Foster, 2014; Kitzinger, 2012; MacKenzie Bryers & van Teijlingen, 2010).

2.5. Researcher positionality

In qualitative research, transparency and credibility are understandably enhanced through disclosure of the researcher’s positionality, including their clinical and personal background (Tong et al., 2007). Towards that aim, it should be noted that the three researchers involved in data collection and analysis in this study (RS, JCP, and HPK) are certified nurse-midwives and midwifery educators and researchers in the United States with clinical experience in both hospital and community birth settings. All study researchers identify as women. None worked in a practice setting that offered care for planned vaginal breech birth, had personal experience with having a breech pregnancy or birth, or had relationships with participants enrolled in the study.

2.56. Data generation

Data included participant responses to open-ended survey questions and semi-structured interviews and researcher-generated field notes, reflective memos, and situational maps. Surveys were completed online by participants independently (n = 23), except where assistance was requested (n = 2). All participants who completed the survey were invited to participate in an in-depth, semi-structured interview. One participant declined interview, and one was lost to follow-up. Interviews were conducted using participants’ preferred technology: Zoom with video enabled (n = 19, 83%), Zoom audio-only mode (n = 1), or telephone (n = 3).

All interviews were conducted by the first author using a predetermined interview guide (Supplemental Table S1). Interviews begun with an open-ended request for participants to share their story of the experience of decision-making. Follow-up prompts asked participants to provide further description including considerations and influential factors in decision-making, narrative of interactions with health care providers, perception of risks and benefits, personal reflections, and recommendations to improve care. Interviews lasted an average of 1.75 hours (range 59–155 minutes, total), with some taking place over multiple sessions due to time constraints or interruptions. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and reviewed to ensure accuracy and incorporate nonverbal communication (Thorne et al., 2004).

Researcher-generated field notes and reflective memos were completed following each interview (Phillippi & Lauderdale, 2018; Thorne, 2016). Situational analysis maps were developed and revised to frame the situation and deepen data analysis (Clarke et al., 2018). These maps depicted the relational ecology of the situation, including relevant human and non-human elements and actors, sociopolitical and organizational entities, and a spectrum of core debates and positions (Clarke et al., 2018).

2.7. Data analysis

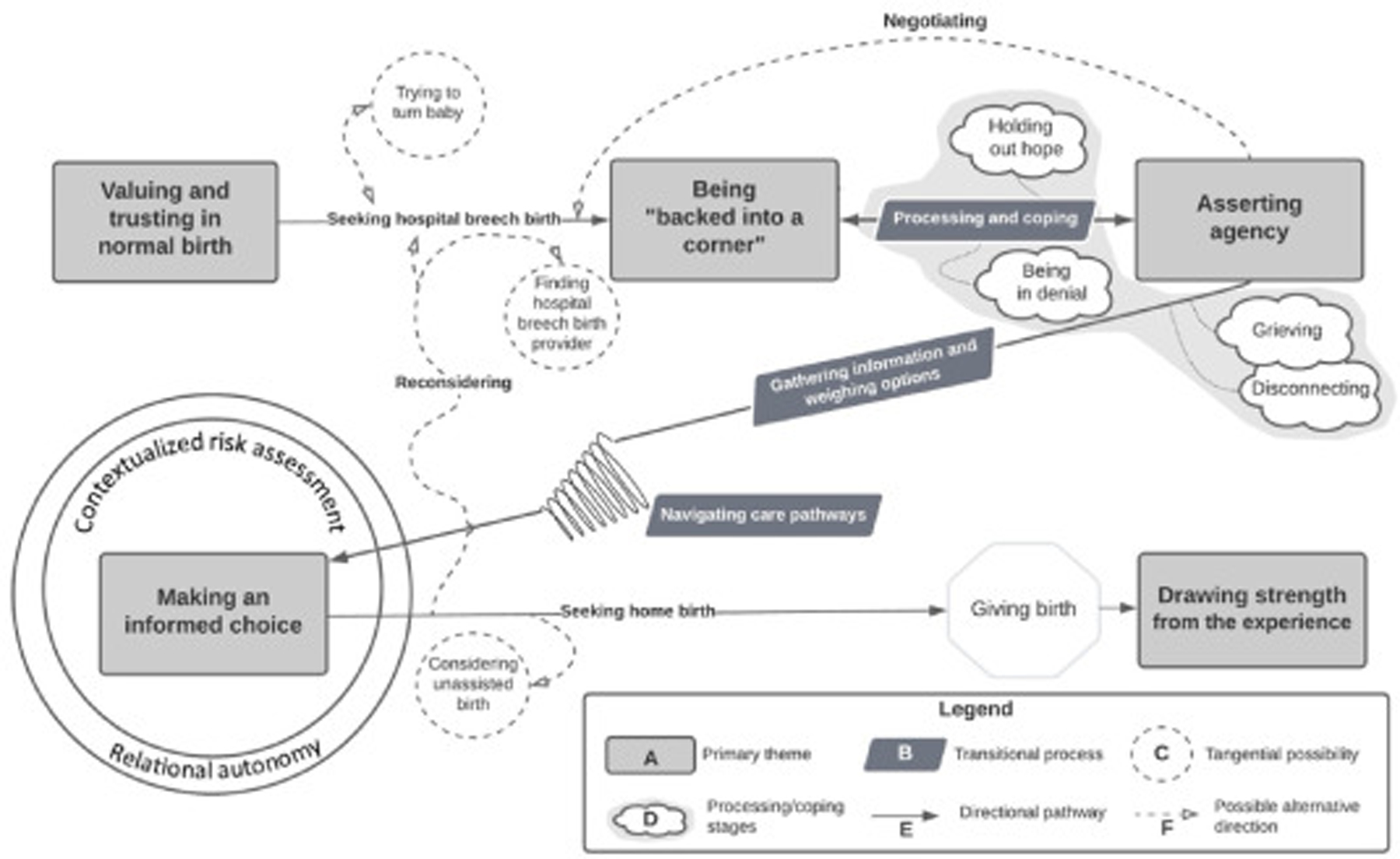

Following immersion in the data, initial coding used a constant comparative coding strategy to assign descriptive or in vivo codes to each meaningful segment of data (Charmaz, 2014), framed by the research questions: (1) what was the participant’s experience, and (2) what can be learned from this to improve care. The first author and a second independent coder (JCP) participated in multiple coding comparisons to reach inter-coder consensus (Saldañ, 2016). Theoretical saturation was achieved after 20 interviews; analysis of the final few interviews did not result in the generation of any new properties of theoretical categories. Agreement on focused codes and the final codebook was achieved by consensus (RS, JCP, HPK). Reflective and theoretical memoing and revisions of situational maps continued throughout analysis and were explored in debriefing to contribute to the development of emerging theory. Theoretical codes were used to develop a storyline (Fig. 1) to illustrate relationships between themes and represent generated theory (Birks et al., 2009).

Fig. 1.

Experience of decision-making following diagnosis of term breech presentation.

An audit trail demonstrating evolution of codes and a detailed project log outlining the research process were maintained throughout the study (Rodgers & Cowles, 1993). Debriefing was undertaken to verify conceptual analysis of fit between data and theory. To elaborate on core themes and facilitate theoretical saturation, the first author reengaged participants through a process of member-checking (Charmaz, 2014) by sharing a short video summary of preliminary findings and a draft of the storyline approximately six months after interview completion. Clinical practice recommendations were reviewed with an expert breech birth provider to assess plausibility. Direct quotes from participants and a table of themes and codes were provided to support and enrich theoretical explanations, and exemplar quotes were selected to illustrate themes and subthemes.

3. Results

The final study sample consisted of 25 participants; detailed demographic information is provided in a prior publication (Schafer et al., 2023). Participants gave birth in 14 different states, representing all regions of the United States and including rural, suburban, and urban settings. Based on comparison with birth certificate and birth registry data, our sample is likely representative of the US home birth population in terms of race and ethnicity, parity, and marriage/partnership status (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023). However, study participants were slightly older (N = 23, median 36.4, interquartile range [IQR] 30.5–38.0) with higher levels of education (n = 24, 96% with at least some college) and more private health insurance (n = 19, 76%) than the general home birth population (Schafer et al., 2023). Most study participants (n = 21, 84%) had been born in the United States; other countries of birth were Guatemala, Germany, United Kingdom, and India. None reported any medical or pregnancy-related complications or history of psychiatric conditions or posttraumatic stress disorder. A variety of birth outcomes were encompassed in the study sample, including breech (n = 23, 92%) and cephalic (n = 2, 8%) births in both homes (n = 22, 88%) and hospitals (n = 3, 12%). Most participants (n = 24, 96%) experienced vaginal birth in their intended site of birth. There was one (4%) intrapartum transfer from home to hospital resulting in non-emergent cesarean birth and three (12%) transfers for postpartum or neonatal complications. The median time from the index birth to interview was 10.3 months (IQR 2.9–36.6).

Although the experience of decision-making for home breech birth was multidimensional, dynamic, and nonlinear, a simplified, illustrated storyline of commonalities of experience following diagnosis of term breech presentation is presented in Fig. 1. We identified five themes that comprised key aspects of the decision-making experiential narrative: valuing and trusting in normal birth, being “backed into a corner,” asserting agency, making an informed choice, and drawing strength from the experience. These themes (depicted by the light gray boxes in Fig. 1) are summarized in Table 1. We also identified three subthemes of transitional processes (represented by the dark gray parallelograms in Fig. 1) which were fundamental to participants’ ability to make an informed choice; these were stages of processing and coping, gathering information and weighing options, and navigating care pathways. Each of these themes and subthemes is described in detail in the subsequent sections.

Table 1.

Key themes and codes.

| Theme | Exemplar codes | Exemplar participant quote | Interpretive summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valuing and trusting in normal birth | • Desiring natural birth • Wanting to avoid cesarean • Viewing birth not as a medical event • Being healthy/normal (breech as a variant of normal) • Having confidence in one’s ability to birth |

“Breech is just a variation of normal.” | Underlying participant values and beliefs reflected a birth philosophy grounded in the normalcy of pregnancy and birth and a desire to experience “natural” (physiologic) childbirth. |

|

Being “backed into a corner” |

• Having no choice • Encountering barriers to agency • Doing “everything possible” • Feeling pressured • Being pushed out of the system |

“How is that consent, if you can’t say no?” |

People felt “cornered,” “threatened,” “vulnerable,” and “hopeless” in interactions with health care providers and systems in which cesarean was presented as the only option for breech birth. |

|

Asserting agency |

• Understanding there are options • Valuing informed consent • Trusting intuition • Doing it “my way” • Owning the outcomes |

“Ultimately it’s your decision, not the doctor’s choice about what you do with your body.” |

Participants defended their right to decisional autonomy, felt empowered to find a “better way,” and assumed responsibility for decision-making and its consequences. |

|

Making an informed choice |

• Processing and coping • Gathering information and weighing options • Navigating care pathways • Balancing identities (relational autonomy) • Defining risk and safety (contextualized risk) |

“I did weigh all the pros and cons, and … I feel like it was the best decision that I could have made for me and my baby.” |

Decision-making was a multidimensional process that involved processing and coping, gathering information and weighing options, and navigating care pathways to make an informed choice based on concepts of relational autonomy and contextualized risk assessment. |

|

Drawing strength from the experience |

• Being transformed • Seeing the good • Healing from trauma • Changing views on health care • Wanting to create change for others |

“It pretty much broke me open, in a way that was pretty” |

This experience was extremely impactful, transforming participants’ sense of self, approach to parenting, and views on medicine and health care providers and creating a strong drive to make positive change for others. |

3.1. Valuing and trusting in normal birth

The experience of decision-making for home breech birth was informed by participants’ underlying beliefs and values, personal philosophies about pregnancy and birth, and previous life experiences. Participants valued and trusted in normal (physiologic) birth, which was viewed primarily as important and meaningful life event rather than biomedical procedure. They considered themselves healthy, had confidence in their ability to give birth, and prioritized embodied knowledge and intuition over scientific or authoritative knowledge (Cheyney, 2008; Davis-Floyd & Sargent, 1997). Breech presentation was considered as a “variant of normal” rather than a high-risk condition, making cesarean unnecessary and undesirable surgery.

I wanted to have a natural birth. I wanted to have that experience.… To me, birth is such a natural thing … I didn’t want [a cesarean] because to me that’s not what birth was, and I knew that birth could be a beautiful thing … so I wanted to avoid it at all cost. (Participant [P]6)

I felt totally confident that my body was capable of birthing my baby in a breech presentation, and I had more concerns about the implications of a C-section. (P15)

3.2. Being “backed into a corner”

Many participants’ preferred birth setting was the hospital, but they were unable to find a skilled and willing breech birth attendant to provide care for planned vaginal birth. Participants perceived “no choice” other than cesarean within the hospital system and received counseling that was viewed as biased and incomplete. They encountered numerous barriers to obtaining care including financial limitations due to a lack of insurance coverage for home birth services, regulatory constraints such as state and institutional policies and regulations limiting scope of practice for breech care, and pressure and judgment from family, peers, and health care providers. Many felt “trapped,” “frustrated,” “coerced,” and even “traumatized” from interactions with care providers.

I was just trying to find somebody that would let me try [for vaginal birth], and I couldn’t. It was insane. It was so hard. (P1)

It wasn’t really presented to me as, “This is now considered a breech birth, now these are your options.” It was like, “Okay, so let’s schedule your C-section.” … I felt a bit judged, to be honest … It was pretty upsetting.… I just left feeling really unsupported and confused. (P12)

I felt like I was backed into a corner and had no choice but to have a home birth. (P11)

Participants frequently expressed that the hospital system offered a “one size fits all” model of care, whereas they wanted individualized care that incorporated their unique preferences, values, and risk factors. They put extreme effort into finding a hospital provider for planned vaginal breech birth. Many also tried numerous complementary and alternative strategies to try to turn the baby into a more optimal birth position. Several underwent a procedure of external cephalic version (ECV) to manually reposition the baby; this experience was generally perceived negatively and, when unsuccessful, led to an increase in providers’ directive counseling for planned cesarean birth. Some participants tried negotiating with hospital-based providers, presenting research about vaginal breech birth and seeking compromises and individualized plans of care.

I tried the [external cephalic] version, he tried it three different times, and it was excruciating.… She wouldn’t move. I went over the options again, but basically, he was like, “We need to schedule a C-section.” That’s what he said. I asked him even if there were other providers around that would potentially even let me go into labor and then see how it progressed. He was basically like, “No, this is not the way this works.” (P7)

I’m like, “You [the doctor] don’t even have to do anything. I can just do it.” That’s what I was thinking. I was like, “I will not hold you responsible, I will not sue you. I promise.” (P17)

Unable to find care for vaginal birth within the hospital system, participants felt that their only option was to seek care in a home birth setting. Many withheld their decision from their care providers, fearing negative judgment or additional pressure. Among participants who did communicate their intent, some reported that providers resorted to evasion or coercion. The use of “scare tactics” or “bullying” led to a loss of trust and firmer resolve to find alternative care. In some cases, following the decision to decline planned cesarean, providers formally terminated the care relationship, leaving participants without access to postpartum, lactation, and neonatal care.

She [the doctor] goes into this story about … a breech delivery, and the baby’s neck broke, and it died. I was like, “Um, she just pulled the dead baby card on me.” … That’s what they were doing the whole time, was trying to scare me with one-sided statistics. (P3)

The doctor even hinted to me … “Well, if you come in and baby is [almost born], then you know, maybe we have no choice but to deliver breech” … Why would they even want me to risk that – having a breech baby and being in the car with her butt hanging out? Because it wouldn’t be on them. They would have no liability if something happened while I’m in the car on the way to the hospital. (P21)

I called like a week and a half after he was born … I wanted to get him circumcised … and she’s like, “Um, we’re not able to … I should let you know that you’ll be receiving a letter in the mail saying that you are discharged as a patient.” And I was like, “Oh really, why?” … “Well, you went against the doctor’s recommendations, and we just felt like it was a liability.” (P6)

3.3. Asserting agency

Participants wanted to determine their planned mode and site of birth and have the opportunity to make an informed choice based on information about the risks and benefits of all available options. They also wanted to be heard, validated, and maintain some control during the labor and birth, ensuring that both their decisional and bodily autonomy were protected. As such, participants were willing to decline (explicitly or implicitly) interventions and provider recommendations. In doing so, they acknowledged the inherent uncertainty of outcomes in pregnancy and birth, accepted that no plan would eliminate risk, and willingly assumed responsibility for their decisions and potential consequences. They often valued their own embodied knowledge and intuition over the authoritative knowledge of their care providers and firmly placed themselves at the center of the decision-making experience, with their providers at the periphery.

I get to have a say in what happens, because I have to live with the consequences … so I’m going to birth in the way that’s going to be the safest for me and the best for me and my baby. End of story. (P13)

I’m really bad with like confrontation, so I just asked, like, “Are there any other choices?” and she [the doctor]’s like, “No, we’re just gonna have to schedule your C-section.” And I knew there’s other choices, but I’m not the type of person to argue with somebody so I just left, and I knew I wasn’t seeing her again and I was, like, “Alright, I’m gonna find someone else.” (P16)

Autonomy is just so important in general in everyday life, but in birth – something so sacred and brutal and beautiful and transcendent – I really believe that there should just be more trust placed in the birthing person. The provider should be there to assist, not dictate. (P5)

3.4. Making an informed choice

Following a diagnosis of breech presentation and learning that their desired birth was no longer obtainable, participants worked through complex stages to make an informed decision for their intended mode and site of birth. Decision-making was dynamic, evolving based on shifting circumstances and new information. Autonomy for decision-making was relational, reflecting embeddedness in relationships with partners, family members, health care providers and institutions, and society at large. Assessment of risks and benefits was subjective and contextual, with participants accepting responsibility for their decision and the unknowability of its outcome. To arrive at the place where they could make an informed choice, participants progressed through transitional processes (subthemes) of processing and coping, gathering information and weighing options, and navigating care pathways.

Processing and coping.

Initially, participants struggled to process the diagnosis of breech presentation and cope with its consequences, experiencing shock, denial, and frustration. Several participants shared that the situation was difficult to accept and were “holding out hope” that the baby might turn. Almost universally, participants experienced grief, “mourning” the loss of their ideal birth. Some “disconnected,” turning away from social connections to avoid stigma and negative judgment, while others reached out to partners, family, friends, birth communities, or online social media groups for advice and support. To support coping, several participants sought strength and peace in spirituality (i.e., faith, religion, mindfulness/intuition, or ancestral knowledge).

I just very much the mindset of, “It’ll all work out. Everything will work out,” you know? I just felt like that last minute, he was going to flip, and I was going to just go through normal birth at the hospital.… At that appointment [when the doctor diagnosed breech presentation], she did discuss things with me. I’m just going to be honest, I don’t remember in great detail, I was so thrown off … I just couldn’t process it. (P15)

She checked [the baby’s presentation] with ultrasound … and said, “Okay, we have to schedule a C-section.” … I said yes. Yes, because I was so shocked in that moment. Then, of course, I went home, and I cried. I was out of my mind, because it was the biggest fear I had that was happening. (P22)

I shut off all my social media. I turned off my phone … I was just getting so many questions about, “Has he turned yet?” and “When’s your cesarean?” … I was processing my own fear and anxiety around it.… I had this intuition that this was the right way to go and that my body could do it, and I needed to trust it…. I was just like, “I need to go in a hole, and I’ll come out when I’m ready.” (P20)

Gathering information and weighing options.

Next, participants sought information to guide informed decision-making and carefully weighed their options. The perception of biased, inaccurate, and incomplete information from hospital-based care providers drove participants to seek information elsewhere such as peer communities, online birth videos, scientific literature, general internet searches, anecdotes of others’ breech births, and other care providers such as doulas, childbirth educators, or chiropractors. Participants integrated or rejected the information they gathered, incorporated their own embodied knowledge, and evaluated all available options to determine the best plan of care. To do so, they conducted a contextualized risk assessment, considering the pros and cons of each available alternative based on subjective perceptions of risks and benefits, in the context of what was meaningful and important to them in their lives.

Safety of the baby was an extremely high priority (often the highest priority), but it was not the only thing that mattered. Participants also valued their maternal and familial health, including psychological and emotional safety and financial stability, and values such as autonomy, bodily integrity, and dignity. Over-medicalization through unnecessary interventions in labor and birth was perceived as a risk, as were threats to future reproductive capacity associated with cesarean birth. Participants considered their decision in the context of their relationships with partners, parents and other family members, friends, and care providers as well as the intuitive connection they felt with their unborn child; perceived obligations to existing children; professional and personal identities; and societal norms. There was also a temporal component of decision-making that extended to both past and future pregnancies. For example, those who had previous birth experiences with good outcomes had high levels of confidence in their ability to give birth again, and those who had experienced cesarean, trauma, or negative encounters with the medical system were strongly motivated to avoid repeat adverse experiences.

There was no discussion about breech delivery or anything like that [with my doctor], just that she wasn’t going to be doing it! So, I came home, and I did all my own research. (P19)

There’s that famous saying, “Oh, as long as you’re safe and baby’s safe and healthy!” I’m like, “That’s a no-brainer, of course, everybody wants that, but what about emotional stability? What about the postpartum period of having to navigate not only being a new parent … plus having to mitigate what you wanted to happen versus what actually happened? What about feeling like you’ve lost control?” (P5)

Literally, I wrote out the pros and cons of each type of birth, and I just kept adding to that list until I found which cons could we handle, is how I basically ended up choosing. (P9)

Navigating care pathways.

Participants then had to navigate complex care pathways to access care for their desired plan for birth, gradually refining their options (represented by the conical spiral in Fig. 1). Navigating care pathways often involved changing to a new provider and planned site of birth late in pregnancy. Several participants explored multiple care pathways simultaneously: some received care in two separate settings due to indecision, while others intentionally received care from a provider that they were not planning on giving birth because of convenience or cost. There were also temporary shifts in care pathways, such as transfers to a hospital-based practice for external cephalic version, surgical consultation, or antepartum care after being “risked out” of a midwifery or birth center practice or being temporarily inbetween providers and without care. Common pivotal moments between care pathways were diagnosis of breech presentation, external cephalic version, shifts in financial situation or insurance coverage, moments of deep reflection, changes in pregnancy-related or medical conditions, finding a new care provider, and being dismissed from care. Decision-making encounters perceived as coercive or disrespectful were often an impetus for leaving a provider, as were interactions that created a loss of trust such as provider interventions in the absence of consent. Some went to great lengths to access a provider including traveling far distances, taking up temporary residence in another state, or paying providers large sums of money (as much as $10,000 out-of-pocket). Others felt “desperate” to find a provider who would offer care for planned vaginal breech birth. Many even considered having an unassisted breech home birth (with no health care provider present) or “showing up pushing” at the hospital with the intent to refuse cesarean.

In the last two weeks of my pregnancy, I was sort of in limbo, trying to find a provider…. I had two prenatal visits with a midwife but did not end up hiring her for the birth in time, mostly because my husband was not on board with home birth. I ended up going back to the hospital to deliver via C-section in the end. (P18)

I felt if no one was going to help me, I may very well have to do it alone [unassisted]. Luckily, I was able to find my breech-friendly provider and have a safe and natural homebirth breech VBAC [vaginal birth after cesarean]. (P11)

People traveled all over for her [the hospital-based breech provider]. … [One pregnant woman] was staying in a hotel waiting for her labor to start…. For me it was like, oh my God, three and half hours, it’s so far. Then I meet these women that had traveled for days, just to get to her. (P10)

After progressing through these transitional processes, participants sought to make and accept a decision about their plan for birth. They felt strongly about their right to make the decision that they determined was best for them within the context of their lives, even when this meant facing negative judgment, and they tried to justify their decision to themselves and others. For some participants, there was a clear turning point, a specific moment when they made their final decision. Others existed in a state of liminality, opting to defer decision-making and “stay open,” with decisions evolving over time. Several participants shared that they repeatedly reconsidered their decision based on shifting situational factors, reevaluating their rationale and exploring options throughout pregnancy, even in active labor. Sometimes after making a decision, intended birth plans became unactionable due to evolving circumstances such as a provider being unavailable or a precipitous labor. Regardless of the outcome, participants felt satisfied with their decision to leave the hospital system to pursue a home breech birth and were grateful that they had the opportunity to exercise agency.

Even my family members … are like, “You risked the life of your child because of your decision.” I said, “No, I made a decision that was safer for me and my child.” … I did weigh all the pros and cons, and this is what I came up with, and I felt good about my decision. (P7)

We were making many decisions, all along.… If I had just been hardline, like, “I’m going to have a vaginal birth, whatever happens,” it could have ended up being a really misguided decision. I wasn’t tied to it to the point where I was going to abandon all reason and risk assessment. It was like, “Okay, this is where we are now. Can we still do it? This is where we are now, can we still do it?” Eventually, things managed to fall into place where it was possible. (P12)

I think I would ultimately just blame myself [if something bad happened], because it was ultimately my decision (pause), which, is a good thing – at least I had a decision. (P9)

3.5. Drawing strength from the experience

Many participants shared that the experience of decision-making for home breech birth was transformational and had profound and lasting effects. Overwhelmingly, after giving birth, participants felt positively about and even idealized their labor and birth experiences, describing them as “easy,” “gentle,” and “beautiful,” “like a dream.” When complications were present, they were often dismissed as tangential or insignificant relative to the aspects of care experience that participants valued more highly such as having agency and feeling empowered and supported. Participants minimized situations that are often otherwise perceived as negative or traumatic, such as postpartum or neonatal complications, asserting that “everything was fine,” or “the way it needed to be.” For several participants with prior traumatic births, this experience provided opportunity for healing. Despite describing decision-making for breech birth as extremely stressful and difficult, participants focused on drawing strength from the experience in a way that increased their self-confidence and positively shaped their parenting. For many, the experience of decision-making affected how they approached health care including their relationships with care providers, confidence in medicine, and future engagement with the health care system.

It was a great home birth. I’m so glad I made that decision. Afterwards, we didn’t have that bonding time as a family at home [because of the need to transfer to hospital postpartum], but I was just thankful for what we did have and that there was no major emergency. I just had a placenta stuck in me for hours and hours (laughs). (P6)

Having my [breech] baby at home has really helped me heal…. I needed that experience to recover from trauma that I experienced [in a previous cesarean birth]…. It just gave me closure to a terrible experience, doing something I know I could have done.… I knew I could do it, and I did it! (P17)

It totally transformed like just so many aspects of me. I don’t even know who I was before that … being able to advocate for myself and stand up for myself … it put it all into perspective for me that, like, I can have that control in other aspects of my life, too. (P11)

Despite reflecting positively on the outcome of their experience, participants were motivated to participate in this study with the hope that by sharing their story, they might help others avoid similar circumstances. They also wanted to draw attention to failures of health care providers and systems to inspire changes that might enable others to obtain more optimal care.

Women should have more choices and more educated, highly skilled individuals to give them those choices. (P7)

I’m willing to share my experience and trauma to help.… Nobody should have to feel like they don’t have a say in what’s going to happen to themself and their baby, and they don’t have options. (P3)

4. Discussion

4.1. Main findings

The experience of decision-making for individuals who left the hospital system to pursue home breech birth was complex and multifaceted. Participants valued and trusted in the physiologic birth process, viewing breech as a variant of normal. However, they encountered substantial barriers to obtaining care for their preferred mode and site of birth. Perceiving no choice other than planned cesarean within the hospital system, many felt “backed into a corner,” “pushed out” of the hospital, and “forced into home birth.” Participants felt strongly that they should be the one to decide their intended mode of birth, and they asserted agency and accepted responsibility for the consequences of their decisions. After progressing through transitional stages of processing and coping, gathering information and weighing options, and navigating care pathways, participants made an informed choice for their desired care and intended plan for pregnancy and birth. This decision was rooted in a relational understanding of autonomy and a nuanced, contextualized assessment of risks and benefits. The experience of decision-making was often extremely emotionally and logistically challenging. It was also profound and transformative, shaping participants views of themselves, their parenthood, and their future engagement with the health system. This study provides a foundation for understanding the experience of decision-making and can inform future research and clinical practice recommendations to improve the quality and person-centeredness of care for breech pregnancy and birth.

4.2. Interpretation

Care for breech birth decision-making failed to meet participants’ expectations for safe, respectful perinatal care, instead causing disempowerment, traumatization, and a perceived lack of opportunity for informed choice. As researchers in other areas of perinatal care have described (Bohren et al., 2015; Downe et al., 2022; Niles et al., 2021), lack of respectful perinatal care in this study arose from poor patient-provider communication and discordance between patient preferences and provider recommendations. At the foundation of this discordance were differing perceptions and prioritizations of risk. For example, participants placed value on the experience of pregnancy, labor, and birth; decisional and bodily autonomy; relationship and communication with the care provider; and holistic interpretations of risk that incorporated threats to psychological, emotional, and familial health. However, participants perceived providers as focusing solely on biomedical outcomes, expecting patient compliance, and prioritizing mitigation of potential neonatal risk over certain threats to maternal well-being. Differing perceptions about the acceptability of interventions which medicalized physiologic birth processes and the prioritization of authoritative (i.e., medical) knowledge over embodied (i. e., intuitive) knowledge also led to discordance between participants and their care providers.

As the first known study to explore decision-making for breech birth in the United States, this research strengthens international findings that decision-making making for breech birth involves complex intrapersonal and contextual factors and has strong emotional impact (Guittier et al., 2011; Petrovska et al., 2017; Roy et al., 2023; Sierra, 2021). Many of the reasons individuals in this study left the hospital system echoed rationale for choosing home birth in general, such as trust in the birth process, respect for embodied knowledge, and the desire to avoid interventions, loss of agency, or retraumatization (Bernhard et al., 2014; Boucher et al., 2009; Coburn & Doering, 2021; Keedle et al., 2015; Sassine et al., 2021). This study adds the knowledge of factors unique to breech pregnancy and birth such as the lack of unbiased information and counseling, access to skilled providers, and institutional support. Our research also presents the complexities of care involved in breech birth decision-making such as having multiple care providers, shifts across different care pathways, and decision-making that took place over multiple encounters or outside of care encounters. It also highlights barriers to open and honest patient-provider communication in care for breech pregnancies based on concerns about negative judgment or provider liability from deviating from the standard of care.

Overall, this study demonstrated that the decision for home breech birth is often a consequence of having limited opportunities for decisional and bodily autonomy within the US hospital system. Similarities may be drawn between the experience of individuals seeking vaginal birth after cesarean in some regions of the United States with regard to perceived threats to bodily integrity, lack of opportunity for informed choice, and substantial barriers to obtaining care (Basile Ibrahim et al., 2021). This study reinforces that for people with “high-risk” conditions, a decision for planned home birth demonstrates failure of the hospital-based system to meet individuals’ preferences for autonomy and less medicalized care (Dahlen et al., 2011; Diamond-Brown, 2019; Hollander et al., 2019; Holten & de Miranda, 2016; Jackson et al., 2020).

4.3. Implications

This exploratory research should be used to guide clinical practice and health system recommendations to increase the provision of safe and respectful care for pregnancy and birth. To better meet standards of quality care, clinicians should provide person-centered, traumainformed care that is respectful of and responsive to individual’s values, needs, and preferences for breech pregnancy and birth. In a personcentered care framework, a “good outcome” is defined in terms of what is meaningful and valuable to the individual (Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001). For birth, this necessarily includes the labor and birth experience (independent from health outcomes) and the complex factors which contribute to holistic well-being (including psychological, cultural, emotional, and spiritual health). Care for breech pregnancy and birth must acknowledge that “safety” extends beyond prevention of morbidity or mortality to encompass protection of dignity, autonomy, and self-determination as basic human rights (Reis et al., 2012).

When approaching decision-making for breech birth, providers should understand that childbearing individuals are considering multiple, contextual, relational aspects of well-being and will inevitably perceive, prioritize, and tolerate risk in uniquely personal ways. Shared decision-making for breech birth should consider respect for patient autonomy, relevant clinical and situational factors, evidence-based information about the full spectrum of care options, and the strength and quality of available evidence (Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001; Reis et al., 2012; Snowden et al., 2018; World Health Organization, 2016). Counseling should be individualized to account for patients’ desired level of involvement in decision-making and their social, educational, and cultural health needs (Kukla et al., 2009). Decision-making encounters should allow sufficient time for individuals to process the situation independently or with partners/family, gather information, consider options, and engage in bidirectional informational exchange that incorporates their unique circumstances, values, needs, preferences, concerns, and embodied knowledge. Decisional support should be offered, including values clarification to help patients identify the optimal plan of care (Elwyn et al., 2012). When there is discordance between provider recommendation and patient preference or inability of a provider to implement the chosen plan of care, the clinician should respect the person’s informed choice and provide informational resources and respectful referral or transfer of care (ACOG Committee on Ethics, 2016; Kotaska & Menticoglou, 2019; Su et al., 2003).

Given the shortcomings of the current perinatal care system highlighted in this study, health systems reforms should be explored to enhance access to care and opportunity for informed choice. This research provides evidence that increased access to vaginal breech birth in US hospital settings would likely decrease planned home breech births and associated risks while increasing patients’ autonomy and satisfaction with care, as others have proposed (Caughey & Cheyney, 2019; Kotaska, 2011; Nethery et al., 2021). Stakeholders should work together to identify and address barriers to care for vaginal breech birth. Medicolegal reforms and changes to institutional policies may be necessary, as this study showed that providers were often unable or unwilling to deviate from the standard of care to “allow” participants to decline scheduled cesarean birth, even when they expressed this decision as an informed choice with acceptance of responsibility for its potential outcomes. Further research is needed to explore the feasibility and efficacy of efforts such as interprofessional education and training, specialized breech teams or centers, evidence-based patient resources and decision tools specific to breech pregnancy and birth, and regulatory reforms (Birthing Instincts, 2020; Borbolla Foster et al., 2014; Breech Without Borders, 2021; Derisbourg et al., 2020; Leeman, 2020; Marko et al., 2019; Nassar et al., 2007; Walker et al., 2018).

4.4. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of this study include the diversity of participants, including geographic location and birth outcomes, and richness of the qualitative data. Multiple iterative strategies were taken to ensure rigor in this study including prolonged engagement with participants, data verification, analytic memos, critical reflection, field notes, and disclosure of researcher positionality (Creswell & Poth, 2018). Trustworthiness of study findings was enhanced by the mixed methods design, which allowed for data triangulation and eligibility criteria that limited inclusion to those who had given birth within the past 5 years to decrease recollection bias (Takehara et al., 2014).

Although as exploratory research into a rare phenomenon, this study did not aim to achieve representative sampling or produce findings that were transferrable to the entire population of interest, the potential for sampling bias is an important limitation of this study. Despite the multimodal approach to recruitment that resulted in a diverse study sample, participants may not representation the full diversity of people who left the hospital system to pursue a home breech birth. For example, individuals who were not active in social media groups or in contact with their breech birth provider were not well represented. It is also possible that those who experienced serious complications or who did not achieve a successful home breech birth may have been less inclined to participate. Additionally, the retrospective, cross-sectional design of this study limits results to a single point in time, and it is possible that participants’ recollections of events and perceptions of the experience of decision-making differ over time.

5. Conclusion

Despite recommendations for inclusion of patient preferences into mode of birth decision-making and support for vaginal breech birth as a “reasonable” option for appropriately screened candidates, there is a lack of opportunity for informed choice for people with a breech pregnancy in the United States. Unable to access care for vaginal breech birth within the hospital system, some individuals choose to give birth at home, potentially placing themselves and their infants at increased risk. Decision-making for home breech birth involves dynamic, interwoven processes of valuing and trusting in normal birth, being “backed into a corner,” asserting agency, making an informed choice, and drawing strength from the experience. Decision-making is embedded in subjective and contextualized interpretations of risk and relational constructions of autonomy. This understanding of the underlying beliefs and values, barriers to care, and the process and outcomes of breech birth decision-making can inform clinical practice and health systems reforms to increase the provision of safe, ethical, and respectful person-centered perinatal care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the March of Dimes, National League for Nursing, Vanderbilt University, and the A.C.N.M. Foundation Inc. for their financial support for this research. The authors would also like to acknowledge Dr. Mary S. Dietrich who contributed to conceptualization of this study and supervision of the research efforts.

Funding

This work was supported by March of Dimes, National League for Nursing, Vanderbilt University, and the A.C.N.M. Foundation Inc.

Biographies

Robyn Schafer, PhD, CNM, FACNM, is Assistant Professor at Rutgers University School of Nursing and Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, where she educates midwifery and advanced practice nursing students, trains obstetric residents, provides perinatal care, and researches clinical decision-making and evidence-based, person-centered care.

Holly Powell Kennedy, PhD, CNM, FACNM, FAAN, is the Helen Varney Professor of Midwifery at the Yale University School of Nursing. Her program of research is focused on a greater understanding of the effectiveness and outcomes of specific models of care during the childbearing year, especially in support of childbearing physiology.

Shelagh A. Mulvaney, PhD, is an Associate Professor at Vanderbilt University School of Nursing with an appointment in Biomedical Informatics. Her research focuses on reducing psychosocial barriers to self-management in people with chronic illness.

Julia C. Phillippi, PhD, CNM, FACNM, FAAN, is a Professor at Vanderbilt University School of Nursing and Vanderbilt Medical Center. She is active in midwifery education, perinatal research, and clinical care.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Robyn Schafer: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Holly Powell Kennedy: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Shelagh Mulvaney: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Julia C. Phillippi: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2024.100397.

References

- ACOG Committee on Ethics. (2016). Committee opinion no. 664: Refusal of medically recommended treatment during pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 127(6), e175–e182. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. (2001). Committee opinion no. 265: Mode of term single breech delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 98(6), 1189–1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. (2017). Committee opinion no. 697: Planned home birth. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(4), 779–780. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. (2018). Committee opinion no. 745: Mode of term singleton breech delivery: Interim update. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 132(2), e60–e63. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002755 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile Ibrahim B, Knobf MT, Shorten A, Vedam S, Cheyney M, Illuzzi J, & Kennedy HP (2021). “I had to fight for my VBAC”: A mixed methods exploration of women’s experiences of pregnancy and vaginal birth after cesarean in the United States. Birth, 48(2), 164–177. 10.1111/birt.12513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT (2004). Birth trauma: In the eye of the beholder. Nursing Research, 53(1), 28–35. 10.1097/00006199-200401000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhan Y, & Haileamlak A (2016). The risks of planned vaginal breech delivery versus planned caesarean section for term breech birth: A meta-analysis including observational studies. BJOG, 123(1), 49–57. 10.1111/1471-0528.13524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard C, Zielinski R, Ackerson K, & English J (2014). Home birth after hospital birth: Women’s choices and reflections. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 59 (2), 160–166. 10.1111/jmwh.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks M, Mills J, Francis K, & Chapman Y (2009). A thousand words paint a picture: The use of storyline in grounded theory research. Journal of Research in Nursing, 14 (5), 405–417. 10.1177/1744987109104675 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield TH (2005). Should “term breech trial” be withdrawn? [Letter to the editor]. BMJ, 330(95). https://www.bmj.com/rapid-response/2011/10/30/should-term-breech-trial-be-withdrawn. [Google Scholar]

- Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, Aguiar C, Saraiva Coneglian F, Diniz AL, Tunçalp Ö, Javadi D, Oladapo OT, Khosla R, Hindin MJ, & Gülmezoglu AM (2015). The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: A mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Medicine, 12(6), Article e1001847. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001847. discussion e1001847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbolla Foster A, Bagust A, Bisits A, Holland M, & Welsh A (2014). Lessons to be learnt in managing the breech presentation at term: An 11-year single-centre retrospective study. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 54(4), 333–339. 10.1111/ajo.12208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boucher D, Bennett C, McFarlin B, & Freeze R (2009). Staying home to give birth: Why women in the United States choose home birth. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 54(2), 119–126. 10.1016/j.jmwh.2008.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovbjerg ML, Cheyney M, Brown J, Cox KJ, & Leeman L (2017). Perspectives on risk: Assessment of risk profiles and outcomes among women planning community birth in the United States. Birth, 44(3), 209–221. 10.1111/birt.12288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breech Without Borders. (2021). https://www.breechwithoutborders.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Caughey AB, & Cheyney M (2019). Home and birth center birth in the United States: Time for greater collaboration across models of care. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133(5), 1033–1050. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National vital statistics system, natality on CDC WONDER online database. Data are from the natality records 2016–2022, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the vital statistics cooperative program. http://wonder.cdc.gov/natality-expanded-current.html. (Accessed 13 November 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick RJ, & Foster D (2014). Negotiating risky bodies: Childbirth and constructions of risk. Health, Risk & Society, 16(1), 68–83. 10.1080/13698575.2013.863852 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2014). Constructing grounded theory (2 ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cheyney MJ (2008). Homebirth as systems-challenging praxis: Knowledge, power, and intimacy in the birthplace. Qualitative Health Research, 18(2), 254–267. 10.1177/1049732307312393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AE, Friese C, & Washburn RS (2018). Situational analysis: Grounded theory after the interpretive turn (2 ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Coalition for Breech Birth. (2020). https://www.facebook.com/groups/coalitionforbreechbirth.

- Coburn J, & Doering JJ (2021). Deciding on home birth. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing, 50(3), 289–299. 10.1016/j.jogn.2021.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Plano Clark VL (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3 ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, & Poth CN (2018). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4 ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlen HG, Jackson M, & Stevens J (2011). Homebirth, freebirth and doulas: Casualty and consequences of a broken maternity system. Women and Birth, 24(1), 47–50. 10.1016/j.wombi.2010.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Floyd RE (1994). The technocratic body: American childbirth as cultural expression. Social Science & Medicine, 38(8), 1125–1140. 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90228-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Floyd RE, & Sargent CF (1997). Childbirth and authoritative knowledge: Cross-cultural perspectives. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, Applebaum S, & Herrlich A (2023). Listening to mothers III: Pregnancy and birth: Report of the third national U.S. survey of women’s childbearing experiences. Childbirth Connection. Retrieved November 13, 2023 from https://nationalpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/listening-to-mothers-iii-pregnancy-and-birth-2013.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derisbourg S, Costa E, De Luca L, Amirgholami S, Bogne Kamdem V, Vercoutere A, Zhang WH, Alexander S, Buekens PM, Englert Y, Pintiaux A, & Daelemans C (2020). Impact of implementation of a breech clinic in a tertiary hospital. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 435. 10.1186/s12884-020-03122-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond-Brown LA (2019). Women’s motivations for “choosing” unassisted childbirth: A compromise of ideals and structural barriers. Reproduction, Health, and Medicine, 20, 85–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dotters-Katz SK, Gray B, Heine RP, & Propst K (2020). Resident education in complex obstetric procedures: Are we adequately preparing tomorrow’s obstetricians? American Journal of Perinatology, 37(11), 1155–1159. 10.1055/s-0039-1692714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downe S, Finlayson K, Oladapo OT, Bonet M, & Gülmezoglu AM (2018). What matters to women during childbirth: A systematic qualitative review. PLoS One, 13 (4), Article e0194906. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downe S, Meier Magistretti C, Shorey S, & Lindström, B. (2022). The application of salutogenesis in birth, neonatal, and infant care settings. In Mittelmark MB, Bauer GF, Vaandrager L, Pelikan JM, Sagy S, Eriksson M, Lindström B, & Meier Magistretti C (Eds.), The handbook of salutogenesis (2nd ed.). Springer Nature. 10.1007/978-3-030-79515-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmir R, Schmied V, Wilkes L, & Jackson D (2010). Women’s perceptions and experiences of a traumatic birth: A meta-ethnography. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(10), 2142–2153. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05391.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwyn G, Frosch D, Thomson R, Joseph-Williams N, Lloyd A, Kinnersley P, Cording E, Tomson D, Dodd C, Rollnick S, Edwards A, & Barry M (2012). Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(10), 1361–1367. 10.1007/s11606-012-2077-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle VA, & Watt IS (2006). Patient involvement in treatment decision-making: The case for a broader conceptual framework. Patient Education and Counseling, 63 (3), 268–278. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischbein SJ, & Freeze R (2018). Breech birth at home: Outcomes of 60 breech and 109 cephalic planned home and birth center births. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 18 (1), 397. 10.1186/s12884-018-2033-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glezerman M (2012). Planned vaginal breech delivery: Current status and the need to reconsider. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol, 7(2), 159–166. 10.1586/eog.12.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goffinet F, Carayol M, Foidart JM, Alexander S, Uzan S, Subtil D, Breart G, & Group PS (2006). Is planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term still an option? Results of an observational prospective survey in France and Belgium. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 194(4), 1002–1011. 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guittier MJ, Bonnet J, Jarabo G, Boulvain M, Irion O, & Hudelson P (2011). Breech presentation and choice of mode of childbirth: A qualitative study of women’s experiences. Midwifery, 27(6), e208–e213. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadjigeorgiou E, Kouta C, Papastavrou E, Papadopoulos I, & Mårtensson LB (2012). Women’s perceptions of their right to choose the place of childbirth: An integrative review. Midwifery, 28(3), 380–390. 10.1016/j.midw.2011.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, & Willan AR (2000). Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: A randomised multicentre trial. Term breech trial collaborative group. Lancet, 356(9239), 1375–1383. 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02840-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauth JC, & Cunningham FG (2002). Vaginal breech delivery is still justified. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 99(6), 1115–1116. 10.1016/S0029-7844(02)02031-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehir MP (2015). Trends in vaginal breech delivery. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 69(12), 1237–1239. 10.1136/jech-2015-205592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipsher C, & Fineberg A (2019). Up against a wall: A patient and obstetrician’s perspective on the mode of breech delivery. Birth, 46(4), 543–546. 10.1111/birt.12432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeyr G, Hannah M, & Lawrie T (2015). Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 7. 10.1002/14651858.CD000166.pub2. CD000166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmeyr G, Kulier R, & West H (2015). External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4. 10.1002/14651858.CD000083.pub3. CD000083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander M, de Miranda E, Vandenbussche F, van Dillen J, & Holten L (2019). Addressing a need: Holistic midwifery in The Netherlands – a qualitative analysis. PLoS One, 14(7), Article e0220489. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holten L, & de Miranda E (2016). Women׳s motivations for having unassisted childbirth or high-risk homebirth: An exploration of the literature on ‘birthing outside the system’. Midwifery, 38, 55–62. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impey L, Murphy D, Griffiths M, & Penna L (2017). Management of breech presentation: Green-top guideline no. 20b. BJOG, 124(7), e151–e177. 10.1111/1471-0528.14465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Instincts Birthing. (2020). Reteach breech https://www.birthinginstincts.com/reteach-breech.

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. National Academies Press. 10.17226/10027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MK, Schmied V, & Dahlen HG (2020). Birthing outside the system: The motivation behind the choice to freebirth or have a homebirth with risk factors in Australia. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20(1), 254. 10.1186/s12884-020-02944-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennewein L, Allert R, Möllmann CJ, Paul B, Kielland-Kaisen U, Raimann FJ, Brüggmann D, & Louwen F (2019). The influence of the fetal leg position on the outcome in vaginally intended deliveries out of breech presentation at term – a FRABAT prospective cohort study. PLoS One, 14(12), Article e0225546–e0225546. 10.1371/journal.pone.0225546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keedle H, Schmied V, Burns E, & Dahlen HG (2015). Women’s reasons for, and experiences of, choosing a homebirth following a caesarean section. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 206. 10.1186/s12884-015-0639-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger S (2012). Rediscovering the social model of childbirth. Birth, 39(4), 301–304. 10.1111/birt.12005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotaska A (2004). Inappropriate use of randomised trials to evaluate complex phenomena: Case study of vaginal breech delivery. BMJ, 329(7473), 1039–1042. 10.1136/bmj.329.7473.1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotaska A (2011). Commentary: Routine cesarean section for breech – the unmeasured cost. Birth, 38(2), 162–164. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2011.00468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotaska A, & Menticoglou S (2019). No. 384: Management of breech presentation at term. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada, 41(8), 1193–1205. 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukla R, Kuppermann M, Little M, Lyerly AD, Mitchell LM, Armstrong EM, & Harris L (2009). Finding autonomy in birth. Bioethics, 23(1), 1–8. 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00677.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkin P, Begley CM, & Devane D (2009). Women’s experiences of labour and birth: An evolutionary concept analysis. Midwifery, 25(2), e49–e59. 10.1016/j.midw.2007.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson GW (2012). The term breech trial ten years on: Primum non nocere? Birth, 39 (1), 3–9. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2011.00507.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman L (2020). State of the breech in 2020: Guidelines support maternal choice, but skills are lost. Birth, 47(2), 165–168. 10.1111/birt.12487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie Bryers H, & van Teijlingen E (2010). Risk, theory, social and medical models: A critical analysis of the concept of risk in maternity care. Midwifery, 26(5), 488–496. 10.1016/j.midw.2010.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie C, & Stoljar N (2000). Relational autonomy: Feminist perspectives on automony, agency, and the social self. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marko KI, Gimovsky AC, Madkour A, Daines D, Abbasi AH, & Soloff MA (2019). Current experience with the vaginal breech initiative at the George Washington University Hospital [1E]. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 133. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000558993.43751.dc, 53S–51S. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SE, Sundin D, & Geraghty S (2022). Women’s experiences of breech birth decision making: An integrated review. Eur J Midwifery, 6(2). 10.18332/ejm/143875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassar N, Roberts C, Raynes-Greenow C, Barratt A, & Peat B (2007). Evaluation of a decision aid for women with breech presentation at term: A randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN14570598]. BJOG, 114(3), 325–333. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01206.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2020). Birth settings in America: Outcomes, quality, access, and choice. The National Academies Press. 10.17226/25636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nethery E, Schummers L, Levine A, Caughey AB, Souter V, & Gordon W (2021). Birth outcomes for planned home and licensed freestanding birth center births in Washington state. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 138(5), 693–702. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newnham E, & Kirkham M (2019). Beyond autonomy: Care ethics for midwifery and the humanization of birth. Nursing Ethics, 26(7–8), 2147–2157. 10.1177/0969733018819119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niles PM, Stoll K, Wang JJ, Black S, & Vedam S (2021). “I fought my entire way”: Experiences of declining maternity care services in British Columbia. PLoS One, 16(6), Article e0252645. 10.1371/journal.pone.0252645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noseworthy DA, Phibbs SR, & Benn CA (2013). Towards a relational model of decision-making in midwifery care. Midwifery, 29(7), e42–e48. 10.1016/j.midw.2012.06.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovska K, Watts NP, Catling C, Bisits A, & Homer CS (2017). ‘Stress, anger, fear and injustice’: An international qualitative survey of women’s experiences planning a vaginal breech birth. Midwifery, 44, 41–47. 10.1016/j.midw.2016.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillippi J, & Lauderdale J (2018). A guide to field notes for qualitative research: Context and conversation. Qualitative Health Research, 28(3), 381–388. 10.1177/1049732317697102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R, Sharman R, & Inglis C (2017). Women’s descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to care provider actions and interactions. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17 (1), 21. 10.1186/s12884-016-1197-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis V, Deller B, Carr C, & Smith J (2012). Respectful maternity care: Country experiences USAID. https://www.k4health.org/sites/default/files/RMC%20Survey%20Report_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, Silva DR, Downe S, Kennedy HP, Malata A, McCormick F, Wick L, & Declercq E (2014). Midwifery and quality care: Findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet, 384(9948), 1129–1145. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60789-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers BL, & Cowles KV (1993). The qualitative research audit trail: A complex collection of documentation. Research in Nursing & Health, 16(3), 219–226. 10.1002/nur.4770160309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy R, Gray C, Prempeh-Bonsu CA, & Walker S (2023). What are women’s experiences of seeking to plan a vaginal breech birth? A systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis. NIHR Open Research, 3(4). 10.3310/nihropenres.13329.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Royal and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG). (2016). Management of breech presentation at term. https://www.ranzcog.edu.au/RANZCOG_SITE/media/RANZCOG-MEDIA/Womens-Health/Statement-and-guidelines/Clinical-Obstetrics/Management-of-breech-presentation-at-term-(C-Obs-11)-Review-July-2016.pdf?ext=.pdf.

- Saldaña J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(2), 179–183. 10.1002/nur.4770180211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassine H, Burns E, Ormsby S, & Dahlen HG (2021). Why do women choose homebirth in Australia? A national survey. Women and Birth, 34(4), 396–404. 10.1016/j.wombi.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer R, Dietrich M, Kennedy H, Mulvaney S, & Phillippi J (2023). “I had no choice”: A mixed-methods study on access to care for vaginal breech birth. Birth. 10.1111/birt.12797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentilhes L, Schmitz T, Azria E, Gallot D, Ducarme G, Korb D, Mattuizzi A, Parant O, Sananès N, Baumann S, Rozenberg P, Sénat M-V, & Verspyck E (2020). Breech presentation: Clinical practice guidelines from the French college of Gynaecologists and obstetricians. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherwin S (1998). A relational approach to autonomy in health care. In Sherwin S (Ed.), The politics of women’s health: Exploring agency and autonomy. Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sierra A (2021). Women’s perception of choice and support in making decisions regarding management of breech presentation. British Journal of Midwifery, 29(7), 392–400. 10.12968/bjom.2021.29.7.392 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin P (1991). Just another day in a woman’s life? Women’s long-term perceptions of their first birth experience. Part I. Birth, 18(4), 203–210. 10.1111/j.1523-536x.1991.tb00103.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden JM, Guise JM, & Kozhimannil KB (2018). Promoting inclusive and person-centered care: Starting with birth. Birth, 45(3), 232–235. 10.1111/birt.12351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su M, McLeod L, Ross S, Willan A, Hannah WJ, Hutton E, Hewson S, Hannah ME, & Term Breech Trial Collaborative, G. (2003). Factors associated with adverse perinatal outcome in the Term Breech Trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 189(3), 740–745. 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]