Abstract

Background

Iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is a major public health problem among children worldwide. Iron deficiency without anemia (IDWA) is at least twice as common as IDA. Some studies propose that oral iron fortification can modify the infant’s gut microbiome, leading to intestinal inflammation.

Objectives

To determine whether oral iron therapy can lead to intestinal inflammation in children with IDA or IDWA.

Patients and methods

Fifty-six patients aged 6 months to 16 years (median age 7.6 years) with IDA or IDWA were randomly assigned to receive either iron (III)-hydroxide polymaltose complex (IPC) 5 mg/kg once daily (maximum dose 100 mg) or sucrosomial iron (SI)1.4 mg/kg once daily (maximum dose 29.4 mg). Safety and efficacy were studied after 30 and 90 days of treatment. In addition, fecal calprotectin as a marker of intestinal inflammation was measured simultaneously and compared to results obtained before therapy.

Results

A significant increase in serum ferritin was noted in both groups as the median ferritin level at baseline was 6.7 μg/L in the IPC group and 6.6 μg/L in the SI group, increasing to 15.9 μg/L and 12.1 μg/L respectively, after 90 days of treatment. However, there was no significant change in fecal calprotectin in either group. In addition, no differences in the trend over time were observed between the two groups regarding fecal calprotectin, serum ferritin, and hemoglobin.

Conclusions

IPC and SI were equally effective in treating IDA and IDWA. At the recommended doses, oral iron therapy does not seem to induce intestinal inflammation.

Keywords: Iron deficiency anemia, Iron deficiency without anemia, Micronutrient powders, Calprotectin, Intestinal inflammation

Introduction

One-fourth of the global population has been estimated to be anemic, as in 2021, 1.92 billion people globally had anemia.1 Across all ages and both sexes, the leading cause of anemia is dietary iron deficiency.1 Therefore, iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is by far the most common anemia worldwide. For every patient with IDA, there is at least one more with iron deficiency without anemia (IDWA), and most of them reside in countries with limited resources.2 In developed countries, the prevalence of IDA in children < 4 years of age is estimated to be 20.1%, while the prevalence increases to 39% in developing countries.3

Iron supplementation aims to prevent sideropenia and to correct established IDA. Many oral iron products at various formulations and doses are available, including ferrous iron salts, ferric iron salts, heme-iron polypeptides, carbonyl iron, chelates of iron with amino acids, complexes of ferric iron with polysaccharides (iron (III)-hydroxide polymaltose complex, IPC), and complexes of iron with amino acids in casein, such as iron protein succinylate and iron acetyl aspartylate.2 Ferrous salts, either sulfate or gluconate, are by far the most commonly used oral iron preparations. However, absorption of oral iron is poor and may be further reduced by certain medications (e.g., proton pump inhibitors) and food intake, thus making oral iron treatment difficult.4,5 In addition, gastrointestinal adverse effects diminish compliance with therapy. A recent study by Jaeggi et al. showed that the provision of iron-containing micronutrient powders (MNPs) to weaning infants adversely affects the gut microbiome, increasing pathogen abundance, fecal calprotectin, and rates of diarrhea among Kenyan infants.6

Recently, new preparations of oral iron, such as sucrosomial iron (SI) became commercially available. SI is an innovative oral iron formulation in which ferric pyrophosphate is protected by a phospholipid bilayer, mainly from sunflower lecithin, plus a sucrester matrix (sucrosome), which is absorbed through para-cellular and trans-cellular routes (M cells).5 To date, in vitro studies have shown that SI is mostly absorbed as a vesicle-like structure, bypassing the conventional iron absorption pathway.5 Due to its behavior in the gastrointestinal tract, SI is well tolerated and highly bioavailable, compared to conventional iron salts.5,7 In an Italian randomized trial, Pisani et al. showed that oral liposomal iron was a safe and efficacious alternative to IV iron gluconate in correcting anemia in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD). However, its effects on the repletion of iron stores and the stabilization of hemoglobin (Hb) after drug discontinuation were inferior.8 Adequate data regarding the efficacy of SI in the treatment of children with IDA are still lacking.

Our study aimed to determine the efficacy and safety of two oral iron preparations in pediatric patients with IDA or IDWA, particularly on intestinal inflammation. One of the products, i.e., IPC has been widely used and studied in the past, while the other (SI), is a new and promising product with limited safety and efficacy data in children.

Patients and Methods

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in assessing anemia, the following cutoff values for Hb were used: Hb<11 g/dL in children 6 months to 59 months old, Hb<11.5 g/dL for children 5–11 years old, Hb< 12 g/dL for children 12–14 years old, Hb< 12 g/dL for adolescent girls > 15 years old, and Hb <13 g/dL for adolescent boys> 15 years of age.9

Patients with IDA had lower Hb values than those listed above and serum ferritin ≤15 μg/L and/or total iron binding capacity (TIBC) ≥425 μg/dL. Patients with normal Hb but serum ferritin ≤15 μg/L or total iron binding capacity (TIBC) ≥425 μg/dL were defined as patients with IDWA. Exclusion criteria were a previous allergic reaction to any of the oral iron products used, children with IDA due to inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), celiac disease or CKD, and children on medications that can lower gastric acidity, such as proton pump inhibitors. The duration of treatment was three months. Patients were randomly assigned by using a random number-generating computer program to receive either IPC 5 mg/kg once daily (maximum daily dose 100 mg) or SI 1.4 mg/kg once daily (maximum daily dose 29.4 mg).

At baseline and after 30 and 90 days, venous blood was drawn. At the same time, parents were instructed to collect and bring a stool sample from their children. The following parameters were determined: Hb, reticulocytes (Ret), serum ferritin, TIBC, serum iron, transferrin saturation, C-reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). The stool samples were introduced within a special vial that can preserve feces for 7 days at 2–8 °C and at −20 °C for 6 months. Calprotectin Turbilatex®, a latex turbidimetric assay for the quantitative detection of calprotectin in human stool samples, was used to determine fecal calprotectin. This assay is performed on the Architect c8000 chemical analyzer (Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA). The calprotectin range is 20–8000 μg/g of stool, with normal levels indicating the absence of inflammation to be < 50 μg/g.

The study was approved by the ethics and research committees of the University General Hospital of Alexandroupolis, and the parents of all participating children gave written informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

The chi-square test was also used to test for significant differences in dichotomous variables. Nominal variables are presented as absolute and relative (%) frequencies, while quantitative ones with mean, standard deviation, median, and interquartile range (IQR). The normality of data was evaluated graphically with histograms, as well as with the Shapiro-Wilk statistical test. To identify significant changes in laboratory measurements 90 days after treatment initiation, a paired t-test (or sign-rank test, when the normality of data did not hold) was performed. Independent samples t-test (or Mann-Whitney test, when the normality of data did not hold) was used to compare changes between the two groups. Trends over time (baseline measurements, 30 and 90 days after treatment initiation) and differences in trends between the two groups were evaluated using Linear Mixed Models. The chi-square test of independence was used to detect differences in the frequency of side effects between the two groups. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. Analysis was conducted with the statistical package STATA SE v.18.

Results

Overall, 56 children were enrolled in the study (age 6 months to 15 years). The demographic characteristics of the participating children are shown in Table 1. Three of them (girls 9, 11, and 14 years old) did not complete the designated oral treatment, as they had severe IDA that did not adequately respond to oral iron therapy after 30 days, thus necessitating the administration of parenteral iron. In addition, six patients (120-month-old boy, 19-year-old boy, and 4 girls 11, 12, 13, and 15 years old) failed to provide stool samples at 30 and/or 90 days and were also excluded. Hence, the final analysis included 47 patients. Among them, 23 patients were prescribed IPC and 24 SI.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participating patients.

| Total (N=56) | Children with IDWA (N=24) | Children with IDA (N=32) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Percentage % | N | Percentage % | N | Percentage % | |||

| Sex | Male (M) | 23 | 41.07 | 14 | 58.33 | 9 | 28.12 | |

| Female (F) | 33 | 58.92 | 10 | 41.66 | 23 | 71.87 | ||

| Age | 6–59 mo | 22 | M:15 | 39.28 | 8 | 33.33 | 14 | 43.75 |

| F:7 | ||||||||

| 5–11 yr | 14 | M:3 | 25.00 | 8 | 33.33 | 6 | 18.75 | |

| F:11 | ||||||||

| 12–15 yr | 20 | M:5 | 35.71 | 8 | 33.33 | 12 | 37.50 | |

| F:15 | ||||||||

mo: months, yr: years.

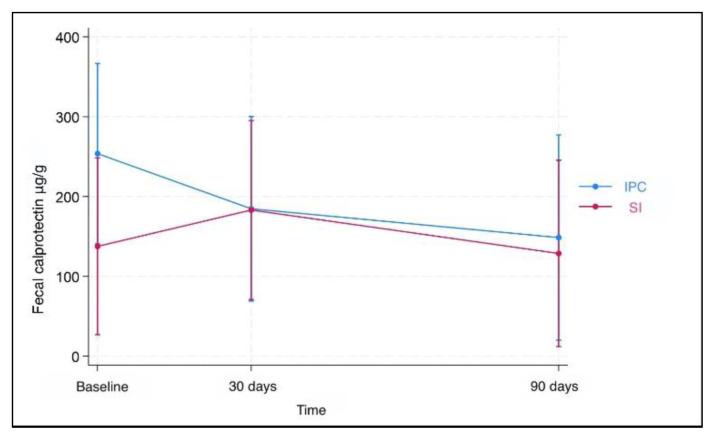

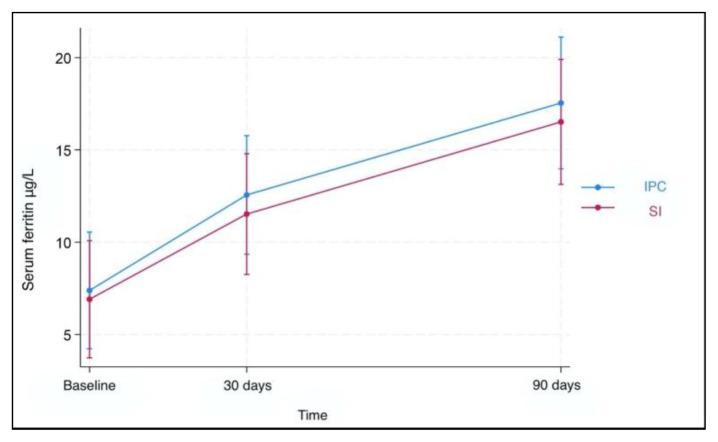

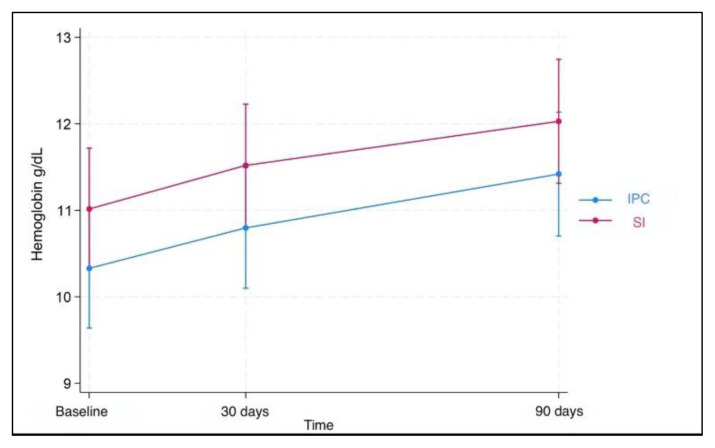

Results for fecal calprotectin, serum ferritin, and Hb at baseline and after 30 and 90 days of treatment are presented in Table 2. Fecal calprotectin levels did not increase compared to baseline measurements in both groups after 90 days of treatment (Figure 1). IPC and SI effectively elevated serum ferritin levels after 30 and 90 days (Figure 2). Median ferritin level at baseline was 6.7 μg/L in the IPC group and 6.6 μg/L in the SI group, increasing to 15.9 μg/L and 12.1 μg/L respectively, after 90 days of treatment (p=0.002 and p=0.001, respectively). Both I PC and SI effectively elevated Hb levels in patients with IDA after 30 (p= 0.003 and p<0.001, respectively) and 90 days of treatment (p=0.002 and p=0.003, respectively) (Figure 3). In addition, no differences in the trend over time were observed between the two groups regarding fecal calprotectin, serum ferritin, and Hb (Table 3).

Table 2.

Results for serum ferritin, fecal calprotectin, and Hb at baseline and after 30 and 90 days of treatment.

| Baseline | After 30 days | After 90 days | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | N | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | N | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | p-value (0 vs 90) | ||

| IPC | Serum ferritin (μg/L) | 26 | 7.8 (4.6) | 6.7 (4.4–10.4) | 25 | 12.7 (8.5) | 11.3 (5.0–16.6) | 19 | 18.6 (13.0) | 15.9 (10.4–23.0) | 0.002# |

| Calprotectin (μg/g) | 26 | 256.8 (515.5) | 61.6 (16.1–213.3) | 24 | 161.7 (190.9) | 114.4 (29.6–227.7) | 16 | 70.6 (60.9) | 47.3 (22.1–107.3) | 0.290# | |

| Hb (g/dL) | 28 | 10.3 (2.4) | 10.7 (8.1–12.6) | 25 | 10.8 (2.2) | 11.5 (8.8–12.7) | 19 | 12.1 (1.4) | 12.1 (10.9–13.2) | 0.002* | |

| SI | Serum ferritin (μg/L) | 26 | 6.9 (3.5) | 6.6 (4.0–8.8) | 24 | 11.7 (8.5) | 9.7 (5.8–13.1) | 22 | 16.5 (11.3) | 12.1 (8.5–25.4) | 0.001# |

| Calprotectin (μg/g) | 27 | 139.4 (160.4) | 108.5 (34.2–171.8) | 26 | 182.5 (257.4) | 85.3 (26.7–253.2) | 22 | 120.9 (162.6) | 49.3 (19.8–123.6) | 0.964# | |

| Hb (g/dL) | 27 | 11.1 (1.4) | 10.9 (10.2–11.9) | 25 | 11.5 (1.5) | 11.6 (10.7–12.4) | 22 | 12.1 (1.8) | 12.1 (11.5–12.6) | 0.003* | |

IPC: iron polymaltose complex, SI: sucrosomial iron, SD: standard deviation, IQR: interquartile range

paired sample t-test

Sign-rank test

Figure 1.

Fecal calprotectin levels over time. There was no significant change in fecal calprotectin levels compared to baseline measurements in both groups after 90 days of treatment.

Figure 2.

Serum ferritin levels over time. Both IPC and SI effectively elevated serum ferritin levels after 30 and 90 days of treatment.

Figure 3.

Hemoglobin levels over time. Both IPC and SI effectively elevated hemoglobin levels in patients with IDA after 30 and 90 days of treatment.

Table 3.

Changes over time in both groups regarding serum ferritin, fecal calprotectin, and hemoglobin.

| IPC | SI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Changes 0–90 | N | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | N | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | p-value |

| Change in serum ferritin | 19 | 9.9(11.9) | 5.5(1.2–18.0) | 22 | 9.8(10.8) | 6.1(0.9–17.6) | 0.977# |

| Change in calprotectin | 16 | −33.3(121.5) | −0.8(−96.8–47.9) | 21 | 1.6(161.4) | −4.7(−89.8–30.3) | 0.474# |

| Change in Hb | 19 | 1.0(0.9) | 0.9(0.4–1.4) | 22 | 1.1(1.1) | 1.1(0.1–1.5) | 0.887* |

IPC: iron polymaltose complex, SI: sucrosomial iron, SD: standard deviation, Hb: hemoglobin, IQR: interquartile range

Independent sample t-test

Mann-Whitney test.

Gastrointestinal side effects, such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation, were reported by 5 patients, 4 in the IPC (17.4%) and 1 (4.2%) in the SI group (p=0.19).

Discussion

Strategies to control sideropenia include daily and intermittent iron supplementation, home fortification with MNPs, fortification of staple foods and condiments, and activities to improve food security and dietary diversity.10 In areas where the prevalence of anemia in children < 5 years of age is ≥20%, WHO recommends fortification of complementary foods with iron-containing MNPs in infants and young children aged 6–23 months.11 In this age group, MNPs decrease the risk of anemia by 18% and iron deficiency by 53% compared to no intervention or placebo.11 However, the safety of this strategy is unclear. In a review of 29 studies conducted in low- and middle-income countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Caribbean, where anemia is a major public health problem, MNPs appeared to improve some cognitive outcomes, such as receptive and expressive language but did not seem to influence all-cause morbidity, diarrhea, upper respiratory infections or the risk of malaria.12,13 However, information on the side effects and morbidity, including malaria and diarrhea, was scarce, and therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution.12

Management guidelines and treatment recommendations for iron-deficient children are not evidence-based, and few clinical studies compare oral iron products in pediatric patients,2,14 often making the choice and dose of the product to be used difficult.

The usually recommended dose for IPC products is 3–6 mg/kg/day in one or divided doses. Jaber et al. compared the efficacy and safety of iron gluconate (IG) versus IPC in the prevention of IDA in 105 healthy infants attending a community pediatric center in Israel. Mean Hb levels at the study end were significantly higher in the IG group, but IPC was associated with significantly fewer adverse events.15 Name et al. randomized 20 children with IDA in Brazil aged 1 to 13 years to IPC or iron bis-glycinate at 3 mg/kg/day for 45 days. They reported that both iron preparations were equally effective in elevating Hb, but only iron bis-glycinate significantly increased ferritin, suggesting greater efficacy than IPC in increasing iron stores.16 Bopche et al. assessed the clinical response and side effects of ferrous sulfate (FS) and IPC in 106 children with IDA. All patients were given elemental iron 6 mg/kg/day in three divided doses. Patients who received FS had significantly higher Hb and fewer residual complaints compared to those who received IPC. However, gastrointestinal side effects were 2.5 times more common in the FS-treated children.17 Powers et al. randomized 80 infants and children aged 9 to 48 months with nutritional IDA to 3 mg/kg/day of elemental iron once daily for three months as either FS or IPC drops. Treatment with FS resulted in a greater increase in Hb concentration at 12 weeks, while the proportion of children with complete resolution of IDA at the end of therapy was also significantly higher in the FS group (29% versus 6%). Both iron products were well tolerated, but there were significantly more reports of diarrhea in the IPC group.18 Sheikh et al. randomized 70 toddlers with IDA to receive FS or IPC at 6 mg/kg/day of elemental iron in three divided doses. Response and compliance with therapy were comparable for both groups.19 In a systematic review and meta-analysis that assessed the effectiveness of IPC in the treatment and prevention of IDA in children, 6 trials (5 from Turkey and 1 from India) were included in the comparison group, which was used to evaluate IPC versus FS. There was moderate to high certainty evidence that FS is superior to IPC in correcting IDA, with a clinically meaningful difference in improving Hb and ferritin levels. The occurrence of gastrointestinal side effects such as spitting, vomiting, constipation, nausea, and stomachaches was comparable between IPC and FS.20 Russo et al. prospectively monitored oral iron therapy in children with IDA aged 3 months to 12 years treated in 15 centers of the Associazione Italiana di Ematologia ed Oncologia Pediatrica. In this multicenter study, 13 patients with mild IDA were given liposomal iron. None of them reported gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, or constipation. However, liposomal iron was less effective in correcting IDA at 2 and 8 weeks compared to other iron preparations, i.e., ferrous gluconate, FS, ferric iron salts, and bis-glycinate iron.21 Cancelo-Hidalgo et al. performed a systematic review of the tolerability of different iron supplements and found that ferrous fumarate had the highest rate of adverse events (47%), followed by FS and ferrous gluconate (32% and 30.9%, respectively). Among all oral iron products, ferrous glycine sulfate, iron protein succinylate, and FS combined with mucoproteose were those better tolerated.22

In our study, patients who were treated with IPC were prescribed 5 mg/kg/day in a single dose. For SI, the dose of 1.4 mg/kg/day was chosen based on an ex vivo and in vivo study of SI intestinal absorption and bioavailability7 and a previously published study.21 The doses used for IPC and SI were equally effective in elevating Hb and serum ferritin levels at 30 and 90 days. The fact that only one patient in the SI group reported gastrointestinal side effects versus five in the IPC group was not statistically significant, but in larger studies, this may not be the case.

Our study showed that oral iron therapy in children with IDA or IDWA aged 6 months to 16 years (median age 7.6 years) does not induce intestinal inflammation, as assessed by fecal calprotectin. Some studies have shown that iron fortification can extensively modify the gut microbiota, increasing enterobacteria and decreasing lactobacilli and leading to intestinal inflammation measured by fecal calprotectin.6,23 Jaeggi et al. performed two double-blinded randomized clinical trials in 6-month-old Kenyan infants consuming home-fortified maize porridge daily for four months. In the first trial, infants received an MNP containing 2.5 mg of iron as NaFeEDTA or the same MNP without iron. In the second trial, they received a different MNP containing 12.5 mg of elemental iron as ferrous fumarate or the same MNP without iron. Comparing +FeMNP versus −FeMNP by qPCR analysis, they revealed a borderline significant effect of iron on enterobacteria, with higher concentrations in the +FeMNP group versus the −FeMNP group. There was a significant treatment effect on the sum of the pathogenic E. coli at the endpoint, with higher concentrations in those who received iron-fortified MNPs. They concluded that the provision of iron-containing MNPs to weaning infants adversely affects the gut microbiome, increasing pathogen abundance, and they also reported increased fecal calprotectin, as well as increased rates of diarrhea among the +FeMNPs groups.6 However, there were no significant correlations of fecal calprotectin with the overall gut microbiome composition assessed by pyrosequencing. The results of our study, at first glance, may seem conflicting. However, the increase in fecal calprotectin through iron fortification shown in the Kenyan study was significant in infants who were iron-sufficient at baseline, not in infants with iron deficiency, like the participants in our study.

A wide range in fecal calprotectin concentration was noted among our patients, decreasing the power of the study. Calprotectin is derived predominantly from neutrophils, where it accounts for about 60% of the cytosolic protein, with a lesser contribution from monocytes and macrophages.24 Fecal calprotectin correlates with the number of neutrophils present in the intestinal lumen and thus allows the detection of an acute gastrointestinal inflammatory response. Moreover, it can be retrieved non-invasively, is inexpensive, and remains stable at room temperature in the stools for at least three days.25 However, concentrations in the feces of healthy infants are much higher than those observed in children older than 4 years.26 Moreover, there are a lot of potential factors that can modify fecal calprotectin, such as viral or bacterial gastrointestinal infections, which are relatively common in children, or the use of drugs such as NSAIDs.25,27 Considering the above, the wide range of fecal calprotectin levels observed in our study may not be surprising.

Our study has some limitations. First, the doses of the two oral iron preparations used may not have been equivalent, although we used the best published and available evidence for choosing equivalent doses. Second, the sample size of our study was relatively small, possibly affecting some outcomes, such as the frequency of gastrointestinal side effects. To this extent, larger studies are needed to conclusively assess the safety profile of SI in comparison to IPC and other oral iron products. Finally, the collection of data on gastrointestinal side effects was based on parental reports alone, which may have been biased.

Conclusions

IDA remains a major public health problem with high prevalence in children. Oral iron therapy in children with IDWA or IDA does not seem to induce intestinal inflammation, as assessed by fecal calprotectin, and therefore, it should be used without delay. Several oral iron products are available, but formulation, dosage, and duration of treatment are mainly empirical. SI is a relatively new oral iron preparation that appears to be a safe and effective alternative to IPC. Large and well-designed clinical trials are needed to establish specific evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of IDWA and IDA in pediatric patients.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflict of Interest.

References

- 1.GBD 2021 Anaemia Collaborators. Prevalence, years lived with disability, and trends in anaemia burden by severity and cause, 1990–2021: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Haematol. 2023;10:e713–e734. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(23)00160-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mantadakis E, Chatzimichael E, Zikidou P. Iron Deficiency Anemia in Children Residing in High and Low-Income Countries: Risk Factors, Prevention, Diagnosis and Therapy. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2020;12(1):e2020041. doi: 10.4084/mjhid.2020.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Torres V, Torres N, Davis JA, Corrales-Medina FF. Anemia and Associated Risk Factors in Pediatric Patients. Pediatric Health Med Ther. 2023;14:267–280. doi: 10.2147/PHMT.S389105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muñoz M, Gómez-Ramírez S, Bhandari S. The safety of available treatment options for iron-deficiency anemia. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(2):149–159. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2018.1400009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gómez-Ramírez S, Brilli E, Tarantino G, Muñoz M. Sucrosomial® Iron: A New Generation Iron for Improving Oral Supplementation. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2018;11(4):97. doi: 10.3390/ph11040097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaeggi T, Kortman GA, Moretti D, Chassard C, Holding P, Dostal A, Boekhorst J, Timmerman HM, Swinkels DW, Tjalsma H, Njenga J, Mwangi A, Kvalsvig J, Lacroix C, Zimmermann MB. Iron fortification adversely affects the gut microbiome, increases pathogen abundance, and induces intestinal inflammation in Kenyan infants. Gut. 2015;64(5):731–42. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fabiano A, Brilli E, Fogli S, Beconcini D, Carpi S, Tarantino G, Zambito Y. Sucrosomial® iron absorption studied by in vitro and ex-vivo models. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2018;111:425–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pisani A, Riccio E, Sabbatini M, Andreucci M, Del Rio A, Visciano B. Effect of oral liposomal iron versus intravenous iron for treatment of iron deficiency anaemia in CKD patients: a randomized trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(4):645–52. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfu357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guideline on haemoglobin cutoffs to define anaemia in individuals and populations [Internet] Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pasricha SR, Drakesmith H, Black J, Hipgrave D, Biggs BA. Control of iron deficiency anemia in low- and middle-income countries. Blood. 2013;121(14):2607–17. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-453522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO Guideline: Use of Multiple Micronutrient Powders for Point-of-Use Fortification of Foods Consumed by Infants and Young Children Aged 6–23 Months and Children Aged 2–12 Years. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De-Regil LM, Suchdev PS, Vist GE, Walleser S, Peña-Rosas JP. Home fortification of foods with multiple micronutrient powders for health and nutrition in children under two years of age (Review) Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8(1):112–201. doi: 10.1002/ebch.1895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez de Romaña D, Mildon A, Golan J, Jefferds MED, Rogers LM, Arabi M. Review of intervention products for use in the prevention and control of anemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2023;1529(1):42–60. doi: 10.1111/nyas.15062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchanan GR. Paucity of clinical trials in iron deficiency: lessons learned from the study of VLBW infants. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):e582–4. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaber L, Rigler S, Taya A, Tebi F, Baloum M, Yaniv I, Haj Yehia M, Tamary H. Iron polymaltose versus ferrous gluconate in the prevention of iron deficiency anemia of infancy. J PediatrHematol Oncol. 2010;32(8):585–8. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181ec0f2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Name JJ, Vasconcelos AR, Valzachi Rocha Maluf MC. Iron Bisglycinate Chelate and Polymaltose Iron for the Treatment of Iron Deficiency Anemia: A Pilot Randomized Trial. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2018;14(4):261–268. doi: 10.2174/1573396314666181002170040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bopche AV, Dwivedi R, Mishra R, Patel GS. Ferrous sulfate versus iron polymaltose complex for treatment of iron deficiency anemia in children. Indian Pediatr. 2009;46(10):883–5. https://www.indianpediatrics.net/oct2009/883.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powers JM, Buchanan GR, Adix L, Zhang S, Gao A, McCavit TL. Effect of Low-Dose Ferrous Sulfate vs Iron Polysaccharide Complex on Hemoglobin Concentration in Young Children With Nutritional Iron-Deficiency Anemia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;317(22):2297–2304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.6846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheikh MA, Shah M, Shakir MU. Comparison of efficacy of ferrous sulfate and iron polymaltose complex in the treatment of childhood iron deficiency anemia. PJMHS. 2017;11:259–261. https://pjmhsonline.com/2017/jan_march/pdf/259.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohd Rosli RR, Norhayati MN, Ismail SB. Effectiveness of iron polymaltose complex in treatment and prevention of iron deficiency anemia in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2021;9:e10527. doi: 10.7717/peerj.10527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russo G, Guardabasso V, Romano F, Corti P, Samperi P, Condorelli A, Sainati L, Maruzzi M, Facchini E, Fasoli S, Giona F, Caselli D, Pizzato C, Marinoni M, Boscarol G, Bertoni E, Casciana ML, Tucci F, Capolsini I, Notarangelo LD, Giordano P, Ramenghi U, Colombatti R. Monitoring oral iron therapy in children with iron deficiency anemia: an observational, prospective, multicenter study of AIEOP patients (AssociazioneItalianaEmato-OncologiaPediatrica) Ann Hematol. 2020;99(3):413–420. doi: 10.1007/s00277-020-03906-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cancelo-Hidalgo MJ, Castelo-Branco C, Palacios S, Haya-Palazuelos J, Ciria-Recasens M, Manasanch J, Pérez-Edo L. Tolerability of different oral iron supplements: a systematic review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2013;29:291–303. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2012.761599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zimmermann MB, Chassard C, Rohner F, N’goran EK, Nindjin C, Dostal A, Utzinger J, Ghattas H, Lacroix C, Hurrell RF. The effects of iron fortification on the gut microbiota in African children: a randomized controlled trial in Cote d’Ivoire. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92(6):1406–15. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Røseth AG, Fagerhol MK, Aadland E, Schjønsby H. Assessment of the neutrophil dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1992;27(9):793–8. doi: 10.3109/00365529209011186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jukic A, Bakiri L, Wagner EF, Tilg H, Adolph TE. Calprotectin: from biomarker to biological function. Gut. 2021;70(10):1978–1988. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ayling RM, Kok K. Fecal Calprotectin. Adv Clin Chem. 2018;87:161–190. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2018.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tibble JA, Sigthorsson G, Foster R, Scott D, Fagerhol MK, Roseth A, Bjarnason I. High prevalence of NSAID enteropathy as shown by a simple faecal test. Gut. 1999;45(3):362–6. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.3.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]