Abstract

Aim:

To evaluate the role of early prophylactic inguinal node dissection in patients with squamous cell cancer and melanoma of lower limb.

Materials and Methods:

From 2008 to 2018, a Tertiary Care Hospital connected to a teaching institute served as the site of this retrospective observational study. Patient records were gathered with the purpose of gathering clinical, investigative, surgical, pathological and follow-up information.

Results:

We included 33 patients in this analysis out of the 47 patients we treated ourselves between 2008 and 2018; among these 33 patients, 21 (63.63%) had palpable inguinal nodes at the time of primary presentation. All 21 patients’ FNAC tests were positive for metastases, in 16 patients (76.19%). 5 patients on FNAC (23.80%) exhibited not metastases. The remaining 12 patients did not have enlarged lymph nodes at the time of their initial presentation. Patients who did not have palpable lymph node were given the option of having a modified inguinal block dissection. 8 patients with metastatic disease have nodes that are positive in histology. In addition, out of 5 patients with negative nodes 4 (80%) showed evidence of metastasis.

Conclusion:

The conclusion of this retrospective observational study is that although palpable lymph nodes in groin are unquestionably a sign that inguinal nodes should be dissected, prophylactic lymph node dissection should be still done even if nodes are not palpable or provide a negative FNAC result. Given that delayed lymphadenectomy has a significant effect on survival, delaying inguinal lymphadenectomy in non-palpable nodes could cause you to lose the battle against cancer in your lower limb. The related surgical morbidity is the only downside to prophylactic lymph node dissection. This can, however, be effectively decreased with a modified inguinal lymphadenectomy operation.

Keywords: Inguinal node, lymph node dissection, morbidity, outcome, squamous cell carcinoma–melanoma of limb

Résumé

Objectif:

Évaluer le rôle de la dissection prophylactique précoce du ganglion inguinal chez les patients atteints d’un cancer épidermoïde et d’un mélanome du membre inférieur.

Matériels et méthodes:

De 2008 à 2018, un hôpital de soins tertiaires relié à un institut d’enseignement a servi de site à cette étude observationnelle rétrospective. Les dossiers des patients ont été rassemblés dans le but de recueillir des informations cliniques, d’investigation, chirurgicales, pathologiques et de suivi.

Résultats:

Nous avons inclus 33 patients dans cette analyse sur les 47 patients que nous avons nous-mêmes traités entre 2008 et 2018; parmi ces 33 patients, 21 (63,63 %) avaient des ganglions inguinaux palpables au moment de la présentation primaire. Les tests FNAC des 21 patients étaient positifs pour les métastases, chez 16 patients (76,19 %). 5 patients sous FNAC (23,80%) ne présentaient pas de métastases. Les 12 patients restants ne présentaient pas d’hypertrophie des ganglions lymphatiques au moment de leur présentation initiale. Les patients qui n’avaient pas de ganglion lymphatique palpable ont eu la possibilité de subir une dissection par bloc inguinal modifié. 8 patients atteints d’une maladie métastatique ont des ganglions positifs en histologie. De plus, sur 5 patients présentant des ganglions négatifs, 4 (80 %) présentaient des signes de métastases.

Conclusion:

La conclusion de cette étude observationnelle rétrospective est que même si les ganglions lymphatiques palpables dans l’aine sont incontestablement un signe que les ganglions inguinaux doivent être disséqués, un curage prophylactique des ganglions lymphatiques doit toujours être effectué même si les ganglions ne sont pas palpables ou fournissent un résultat FNAC négatif. Étant donné que le retardement du curage lymphatique a un effet significatif sur la survie, retarder le curage inguinal des ganglions non palpables pourrait vous faire perdre la bataille contre le cancer du membre inférieur. La morbidité chirurgicale associée est le seul inconvénient du curage prophylactique des ganglions lymphatiques. Ceci peut cependant être efficacement réduit grâce à une opération de lymphadénectomie inguinale modifiée.

Mots-clés: Ganglion inguinal, curage ganglionnaire, morbidité, évolution, carcinome épidermoïde – mélanome d’un membre

INTRODUCTION

In India, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma of the lower limbs are uncommon cancers. The prevalence of this malignancy varies greatly over the globe. Squamous cell cancer of the lower limb is uncommon, although melanoma is a prevalent malignancy in the Western world.[1] In the Indian scenario, squamous cell carcinoma of the lower limb is a prevalent disease that is associated with both definite morbidity (in terms of limb function) and mortality.[1] In Europe and the US, the incidence is <1/100,000 males, or 0.4%–0.6% of all cancers.[2,3] Records from the Indian Cancer Registry show that 2%–6% of all malignancies occurred there. The prevalence in India is between 0.7 and 3/100,000 for both men and women.[4] There is a significant variation in incidence between the urban and rural populations, with 0.7–2/100,000 men and women and 3.2/100,000 men, respectively.[5] Such cancers account for 0.5%–1% of all malignancies at my institution. While the specific cause of this disease is unknown, prolonged irritation and a history of burns are likely risk factors for lower limb cancer.[6] Squamous cell cancer is the most prevalent histological kind of cancer of the lower limbs and tends to develop from the squamous epithelium of the skin.[1,7] According to natural history, the spread to inguinal and ilioinguinal lymph nodes happens in a very sequential and predictable manner.[7] Although uncommon, we included melanoma in our list of cancers that affect the inguinal nodes even earlier than squamous cell cancer and it arises from melanocytes.

From 30% to 60% of those with initial presentation have palpable groin nodes. More than 50% are positive for metastatic disease in regional nodes, whereas the remaining enlarged nodes are caused by the inflammatory or infective response.[8,9]

The management of the inguinal lymph nodes, which is crucial to the outcome and quality of life for these patients, must thus be addressed along with other crucial surgical alternatives.[10] Even if there are numerous clinical standards and pathological criteria accessible for decision-making, predicting the outcome is still a challenging task.[1,8] A clearer knowledge of the development of these tumors would be beneficial.[7] As a result of advances in technology, the cure rate has increased from 50% in the 1990s to almost 75%–80% during the past few decades.[8] The occurrence of metastasis ensures significant morbidity in individuals with these cancers. Therefore, we concentrated on acting quickly and doing early prophylactic lymph node dissection rather than late therapeutic inguinal lymph node dissection.[11]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

From September 2008 to December 2018, this retrospective observational study was conducted in a Tertiary Care Teaching Institute. Clinical, investigative, surgical, pathological, and follow-up information were extracted from patient records and placed into a prestructured database. All other patients were removed, and only those patients were included who were being followed up on and whose pertinent clinical information could be collected. Thus, we could take into account two patients who had melanoma on the sole of the foot and 31 patients out of 47 who had lower limb squamous cell cancer. The majority of our patients are over 40, with a mean age between 45 and 60 years. Three of the individuals we had were between the ages of 28 and 35 years.

Twenty-one individuals exhibited clinically significant unilateral inguinal nodes at the time of original presentation among 33 cases with pathological diagnoses of squamous cell carcinoma of the lower limb and melanoma of the sole of the foot. Only 16 individuals had favorable results from fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) using inguinal nodes. The remaining five patients’ FNAC results were negative, and the remaining 12 patients had no palpable lymph nodes. With simultaneous extensive local excision of the main tumor and repair, we performed radical inguinal block dissection on 16 out of 31 patients, including 2 with melanoma of the sole of the foot. The remaining 17 patients underwent initial surgery for limb cancer along with a modified inguinal block dissection. To the five patients whose FNAC results were negative, we did not recommend a course of antibiotics. There were no in-transit nodules or palpable nodes in the two individuals with solely diagnosed melanoma who were part of the study.

All of these patients with limb malignancies were scheduled for surgery involving extensive local excision and plastic repair of the injured area, which will restore function to the patient’s limb after the procedure, as well as inguinal lymph node dissection regardless of whether the lymph nodes are palpable or not. Due to the biological characteristics of melanoma, the type of lymph node dissection used was more extreme than that for squamous cell cancer.

Technique

The standard criteria, the ability to preserve a functional limb, and compliance with oncological principles all play a role in the decision-making process for the primary disease site. The 33 Patients all had simultaneous inguinal node dissection.

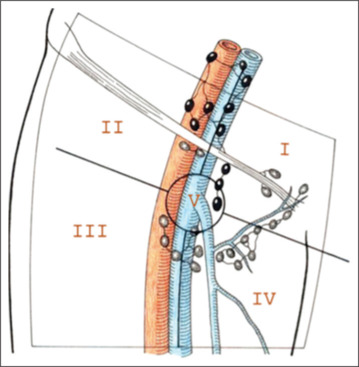

Dissection capacity limits

The radical groin dissection as mentioned in Figures 1 and 2 entails the dissection of the superficial and deep inguinal nodes in a quadrilateral bounded by the inguinal ligament superiorly, a line extending 15 cm down from the pubic tubercle medially, a line extending 20 cm down from the anterior superior iliac spine laterally, and a line connecting the inferior ends of the lateral and medial lines. The saphenous vein and its tributaries are spared, limiting the lateral extent of the node dissection to the femoral vessels, in a modification of the radical inguinal lymphadenectomy. The inguinal ligament, Sartorius muscle, and adductor longus muscle form the triangle around which the superficial and deep nodes are removed. The femoral vessels are the only lateral extent of the node dissection in Catalina’s widely adopted variant, which also shortens the skin incision. For cases with confirmed nodal groin metastases, radical dissection is still the preferred treatment.[12]

Figure 1.

Template - modified inguinal node dissection

Figure 2.

Template - radical inguinal node dissection

A surgeon with professorial training performed each operation. The following information is included in the follow-up record: Characteristics of the primary tumor, including grade, T stage, lymphovascular invasion, and correlation with pathologically positive nodes. In accordance with the well-differentiated grading scale, we also used it (Grade 1) insufficiently differentiated (Grade 3), moderately differentiated (Grade 2). Within 30 days after surgery and 30 days after surgery, severe and minor complications were recorded. It also keeps track of complications requiring additional procedures.

RESULTS

Thirty three individuals were included in the study out of 47 instances with a pathological diagnosis of lower limb squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma. The other 14 patients were excluded because they did not meet the criteria for inclusion – 3 of them had extensive systemic disease, 7 patients had been lost to follow-up, and 4 patients’ data were lacking. Twenty-one patients (63.63%) as mentioned in Table 1 of the 33 patients included had clinically significant nodes at the time of initial presentation. Only 16 individuals (76.19%) had a positive FNAC from the inguinal nodes, though. In 16 patients, we performed radical inguinal block dissection while simultaneously doing a large local excision of the tumor with a conventional margin of 2 cm from the palpable tumor borders. The remaining 15 patients had modified inguinal node dissection as mentioned in Figure 1. To our astonishment, out of 31 patients, histopathology showed positive modal metastasis in 27 patients (87.09%). It is interesting to note that in 80% of individuals with negative FNAC results from inguinal nodes, nodes were found to be positive on histopathology in 4 out of 5 patients.

Table 1.

Clinically palpable ipsilateral inguinal nodes-fine-needle aspiration cytology from these nodes

| Patients with palpable nodes | Nonpalpable nodes | FNAC positive | FNAC negative |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | 10 | 16 | 5 |

FNAC=Fine-needle aspiration cytology

These patients were typically followed up for 3 to 4 years.

Our patients’ average age was 40 or older, and their ages ranged from 28 to 78.

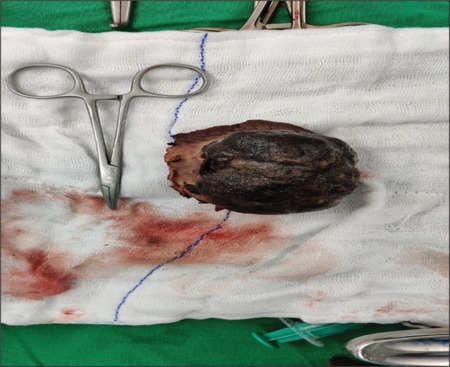

Squamous cell carcinoma of the lower limb (Leg) was found in 31 of our patients, while melanoma of the right foot depicted in Figures 3 and 4 was found in 2 individuals (Heal).

Figure 3.

Malignant melanoma involving the heel of left foot

Figure 4.

Excision of the melanoma

When FNAC from the inguinal lymph nodes came back negative, we decided against prescribing a course of antibiotics and instead waited. The morbidity related to surgical treatment in node-negative patients was our only worry. In patients with positive nodes (on FNAC) and functional inguinal lymph nodes, we used radical inguinal node block dissection as our method.[13] Patients who undergo dissection may have (FNAC) negative nodes or inguinal nodes that are not palpable. This article concerns the morbidity that occurs when patients with nodes negative undergo radical inguinal block dissection. Before and following surgery, risk stratification was also carried out in our study. The disease’s stage and grade were mentioned. T2N1 illness was present in 26 out of 31 patients (83.87%), the remaining 5 individuals’ (16.12%) illness was T3N1. In 23 cases, the condition was classified as Grade 1 (well-differentiated cancer). Six patients (74%), with Grade II (moderately differentiated cancer), and two more (6.4%), with Grade III (poorly differentiated cancer), as mentioned in Table 2 were the remaining patients.

Table 2.

Grade-wise lymph node involvement

| Histological grading | Patients with positive inguinal nodes | Patients with pelvic nodes |

|---|---|---|

| Grade I | 23 | Nil |

| Grade II | 6 | Nil |

| Grade III | 2 | 2 |

Out of 33 patients, 31 patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the leg underwent a wide local excision with a typical margin of 2 cm around the tumor’s palpable bounds. This was followed by plastic surgery to cover the exposed skin as mentioned in Figure 5 where the tumor had been removed. Two melanoma patients underwent ileoinguinal lymph node dissection and broad local excision based on the thickness and depth of invasion.

Figure 5.

STSG of the heel after excision. STSG: Split thickness skin grafting

We tallied the lymph nodes removed from the material and found that, on average, 3–6 nodes were affected. This is to give patients who have more than four positive nodes adjuvant radiotherapy. Our main worry was morbidity, which is documented in up to 57% of the groin in 39% of individuals and is related to radical groin dissection.[14] we have morbidity in our series in terms of problems. We divided them into two categories: Major and minor complications, determined by the need for a second procedure or treated by routine care, and we reported morbidity in the first 30 days and morbidity after 30 days. The incidence of problems following modified lymphadenectomy was minimal, and they were all rather modest. However, patients who have had radical lymph node dissection tend to experience the most morbidity. (1) Lymphedema, (2) infected wounds, and (3) wound edge necrosis are common consequences leading to morbidity. (4) Lymphorrhea, the average length of a surgical procedure was between 90 and 120 min. An average of 30–50 ml of blood was lost.

Every 3 months for the 1st year, every 6 months for the next 2 years, and then once a year for the next 3 years, or more frequently if the patient complained, was the follow-up procedure. In our cohort, no patient experiences a local or regional recurrence. After approximately 7 years of follow-up, 3 of our patients passed away.

DISCUSSION

Squamous carcinoma of the limb is a rare malignancy as depicted in Figure 6, with incidence ranging from 0.4% to 20%,[2,3] however it is not infrequent and has a high morbidity and mortality rate in the Indian subcontinent.[1,4] Its presentation varies from country to country. In 96% of cases, lymphogenic spread of this type of cancer occurs.[15] The treatment and prognosis of patients with squamous carcinoma heavily depend on how the ipsilateral inguinal nodes are managed.[16] If the war against limb-threatening squamous carcinoma and melanoma is to be won, precise management of the inguinal lymph node is crucial.

Figure 6.

Marjolins ulcer involving the right leg

Between 30% and 60% of Squamous cell cancer and melanoma cases involve the inguinal nodes at the time of initial presentation.[7,10]

Thirty-three patients were included in our study, and 21 (67.74%) of them had palpable nodes at the time of initial presentation. When the primary presentation occurs, distant metastases can occur in as little as 1.9%–7% of cases.[17] Patients who had distant metastases were excluded from our study. Sixteen (76.19%) of the 21 patients in the current study had positive FNAC nodes. There were 27 individuals (87.09%) with metastatic deposits following inguinal node dissection. This suggests that even in cases when nodes cannot be felt, more than 20% of patients have lymph nodes visible on dissection, and nearly >70% of patients have micrometastases. This suggests that the clinical assessment of the groin is somewhat inaccurate.[15] Groin node involvement is quite predictable and sequential.[15] The left groin nodes are affected 67% more often than Right nodes, which are affected 27% less frequently. Bilateral node involvement was 4%.[7]

To detect physically metastatic nodes, imaging tests such as ultrasonography have low sensitivity and specificity; however, when combined with FNAC, they have a sensitivity and specificity of 39% and 100%.[18,19] Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has 100% sensitivity and 97% specificity, while computed tomography (CT) scans have a sensitivity of 36%.[20] When it comes to identifying enlarged nodes with micrometastasis,[21] positron emission tomography CT has a 94% positive predictive value and a 96% negative predictive value.[22] Even though they are sensitive, imaging examinations cannot be as conclusive as cytology or histopathology. In light of this, nonsurgical methods are equally unreliable for detecting the genuine condition of the local lymph nodes.[23] Sentinel node biopsy, the minimally invasive dynamic sentinel node biopsy, and the micro particular MRI scan were not available to us.[18,19,20] In our study, we found that lymph node involvement is influenced by the biology of the underlying illness, grade, and lymphovascular invasion.

Although we did not perform molecular testing on these patients to determine if they would have inguinal node metastases, extensive literature research has shown that these markers (Ki67 and Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) DNA) do not reliably indicate the development of metastases.[24,25]

According to numerous publications, the cure rate for nodes that are histologically positive is roughly 20%–60%.[12,15,18,19,20,21,26,27,28,29,30]

Moreover, 5-year recurrence-free rates ranged from 75% to 95%.[17]

We made the decision to take an aggressive strategy by performing preventive lymph node dissection in cases of nonpalpable inguinal nodes and not observing the patient. Numerous studies revealed increased survival. According to observation and recurrence in follow-up, these patients’ chances of survival and (bad) outcome are in jeopardy.[29,30]

Radial groin dissection morbidity, which has been observed in up to 57% of the groin in 39% of patients, has long been a major source of worry.[10] When compared to modified techniques, radical inguinal lymphadenectomy has shown to increase morbidity.[26] Although there is a certain morbidity in operations related to radical dissection in our study when we estimated the morbidity in terms of consequences, there is a very low morbidity in patients who have undergone modified inguinal node dissection. In the past, studies have found that significant morbidity occurs 30%–50% of the time with radical lymphadenectomy, and death can reach 3%.[4,9,12,21,27] Recent series have shown a complication rate of about 15%, which is much more tolerable.[7,10,17]

(1) Lymphedema and (2) infected wound. (3) Wound-edge necrosis (4) Lymphorrhea [Table 3].[10,17]

Table 3.

Comparison of morbidity after radical versus modified lymph node dissection

| Complications/morbidity | Radical inguinal lymphadenectomy (%) | Modified lymph node dissection (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Lymphedema | 4 out of 21 (19.04) | 1/10 temporary (10) |

| Lymphocele | 1 out of 21 (4.76) | Nil (0) |

| Wound edge necrosis | 3 out of 21 (14.28) | 3 needed simple dressings (30) |

| Wound infection | 3 out of 21 (14.28) | 2 simple changes in antibiotics and dressings (20) |

In our study, there were no patients who required a second procedure due to associated complications.

However, in our study, we adjusted the procedure for inguinal lymphadenectomy in patients with negative FNAC and nonpalpable nodes. As a result, morbidity has decreased significantly and no patient has needed a second treatment. Essential criteria for determining the prognosis are pathologic staging and grading. The outcome is negative the higher the grade.[31] Only a few of our patients are in stage, with the majority of patients being in clinical Stages II and III. Thus, the timing of the inguinal lymphadenectomy plays a significant role in the outcome.

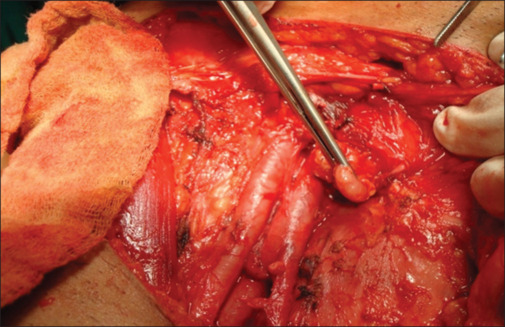

CONCLUSION

The following facts summarize our study: Patients with lower limb squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma should consider having an inguinal lymphadenectomy as a crucial and beneficial predictor of survival and quality of life. Complete removal of ipsilateral inguinal nodal metastases determines the prognosis for individuals who have squamous cell carcinoma and limb melanoma with cover of the required with a skin graft as depicted in Figure 7. The choice of early prophylactic lymphadenectomy over late therapeutic inguinal node dissection as depicted in Figure 8 was made due to inaccuracies in clinical examination, failure of nonsurgical methods to ascertain the true status of the regional lymph nodes, the lack of sentinel node mapping or minimally invasive dynamic sentinel node biopsy as the best option for a better outcome. Numerous findings indicate that delayed lymphadenectomy has undoubtedly impacted the quality of life and survival. Prophylactic lymphadenectomy has clear benefits, but there is also a clear risk of morbidity in node-negative patients. Because of this, it cannot be regarded as the gold standard in the treatment of squamous malignancies. However, because the biology of the illness is more aggressive than squamous cell cancer, early preventive lymph node removal for melanoma of the limb is very well justified. Therefore, it is imperative that we adhere to procedures and approaches to increase the detection of positive inguinal nodes and reduce morbidity for a better result.[32,33]

Figure 7.

STSG after excision of the marjolins ulcer. STSG: Split thickness skin grafting

Figure 8.

Cloquet’s lymph node – node at femoral ring

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Solsona E, Algaba F, Horenblas S, Pizzocaro G, Windahl T, European Association of Urology EAU guidelines on penile cancer. Eur Urol. 2004;46:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horenblas S. Lymphadenectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Part 2: The role and technique of lymph node dissection. BJU Int. 2001;88:473–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ENCR (European Metwork of Cancer Registries) Lyon IARC; 2001. Eurocim Version 4.0. European Incidence Database V.2.2. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy CR, Raghavaiah NV, Mouli KC. Prevalence of carcinoma of the penis with special reference to India. Int Surg. 1975;60:474–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penile Cancer. 2009 Available from: http://www.indiacancersurgerysite.com/penile-cancer-treatment-india.html . [Last accessed on 2014 Sep 10] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dillner J, von Krogh G, Horenblas S, Meijer CJ. Etiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl. 2000:189–93. doi: 10.1080/00365590050509913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abi-Aad AS, deKernion JB. Controversies in ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy for cancer of the penis. Urol Clin North Am. 1992;19:319–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rangabashyam N, Gnanaprakasam D, Meyyappan P, Vijayalakshmi SR, Thiruvadanam BS. Carcinoma of penis. Review of 214 cases. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1981;26:104–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ornellas AA, Seixas AL, Marota A, Wisnescky A, Campos F, de Moraes JR. Surgical treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the penis: Retrospective analysis of 350 cases. J Urol. 1994;151:1244–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35222-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ravi R. Morbidity following groin dissection for penile carcinoma. Br J Urol. 1993;72:941–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saisorn I, Lawrentschuk N, Leewansangtong S, Bolton DM. Fine-needle aspiration cytology predicts inguinal lymph node metastasis without antibiotic pretreatment in penile carcinoma. BJU Int. 2006;97:1225–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ornellas AA, Seixas AL, de Moraes JR. Analyses of 200 lymphadenectomies in patients with penile carcinoma. J Urol. 1991;146:330–2. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37784-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Protzel C, Alcaraz A, Horenblas S, Pizzocaro G, Zlotta A, Hakenberg OW. Lymphadenectomy in the surgical management of penile cancer. Eur Urol. 2009;55:1075–88. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalona WJ. Modified inguinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the penis with preservation of saphenous veins: Technique and preliminary results. J Urol. 1988;140:306–10. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)41589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Protzel C, Knoedel J, Wolf E, Kleist B, Poetsch M, Giebel J. Prognostic parameters of penis carcinoma. Urologe A. 2007;46:1162. doi: 10.1007/s00120-007-1454-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gursel EO, Georgountxos C, Uson AC. Penile cancer: Clinicopathologic study of 54 cases. J Urol. 1973;1:569–73. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(73)90517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inguinal Metastasis in Penile Cancer; Diagnosis and Management , Joost AP, Horenblas LS. EAU-EBU Update Series 5. 2007:142–52. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Protzel C, Kakies C, Kleist B, Poetsch M, Giebel J. Down-regulation of the metastasis suppressor protein KAI1/CD82 correlates with occurrence of metastasis, prognosis and presence of HPV DNA in human penile squamous cell carcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:369–75. doi: 10.1007/s00428-008-0590-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schlenker B, Scher B, Tiling R, Siegert S, Hungerhuber E, Gratzke C, et al. Detection of inguinal lymph node involvement in penile squamous cell carcinoma by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose PET/CT: A prospective single-center study. Urol Oncol. 2012;30:55–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ravi R. Correlation between the extent of nodal involvement and survival following groin dissection for carcinoma of the penis. Br J Urol. 1993;72:817–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb16273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouchot O, Rigaud J, Maillet F, Hetet JF, Karam G. Morbidity of inguinal lymphadenectomy for invasive penile carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2004;45:761–5. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horenblas S, van Tinteren H, Delemarre JF, Moonen LM, Lustig V, van Waardenburg EW. Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. III. Treatment of regional lymph nodes. J Urol. 1993;149:492–7. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gursel EO, Georgountzos C, Uson AC, Melicow MM, Veenema RJ. Penile cancer. Urology. 1973;1:569–78. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(73)90517-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leijte JA, Kerst JM, Bais E, Antonini N, Horenblas S. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced penile carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2007;52:488–94. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mistry T, Jones RW, Dannatt E, Prasad KK, Stockdale AD. A 10-year retrospective audit of penile cancer management in the UK. BJU Int. 2007;100:1277–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pandey D, Mahajan V, Kannan RR. Prognostic factors in node-positive carcinoma of the penis. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93:133–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.20414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gospodarowicz MK, O’Sullivan B, Hilligers SL. 3rd. USA Based publishing company- River St. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. Prognostic Factors in Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graafland NM, Teertstra HJ, Besnard AP, van Boven HH, Horenblas S. Identification of high risk pathological node positive penile carcinoma: Value of preoperative computerized tomography imaging. J Urol. 2011;185:881–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.10.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tabatabaei S, Harisinghani M, McDougal WS. Regional lymph node staging using lymphotropic nanoparticle enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with ferumoxtran-10 in patients with penile cancer. J Urol. 2005;174:923–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000170234.14519.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bevan-Thomas R, Slaton JW, Pettaway CA. Contemporary morbidity from lymphadenectomy for penile squamous cell carcinoma: The M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Experience. J Urol. 2002;167:1638–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leijte JA, Horenblas S. Shortcomings of the current TNM classification for penile carcinoma: Time for a change? World J Urol. 2009;27:151–4. doi: 10.1007/s00345-008-0308-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDougal WS. Carcinoma of the penis: Improved survival by early regional lymphadenectomy based on the histological grade and depth of invasion of the primary lesion. J Urol. 1995;154:1364–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)66863-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leijte JA, Hughes B, Graafland NM, Kroon BK, Olmos RA, Nieweg OE, et al. Two-center evaluation of dynamic sentinel node biopsy for squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3325–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]