Abstract

Context:

Adrenal incidentalomas (AIs) are relatively uncommon neoplasms in 2% of apparently healthy individuals requiring evaluation for functionality and malignancy.

Aim:

We aimed to study the clinical, biochemical, and radiological profiles of patients presenting with AI and histopathological outcomes of those undergoing adrenalectomy.

Materials and Methods:

This retrospective study enrolled 62 AI patients attending a tertiary care center in South India between January 2016 and October 2023. Demographic details, radiological features, functionality, and histopathological data were analyzed.

Results:

Out of 62 patients, total masses evaluated were 65 indicating bilaterality in 3 patients. The female: male ratio was 1.69, with a median age of 55 years (interquartile range: 44–64 years). 45.1% of individuals were >60 years. The most common indication for imaging was pain abdomen in 43 (69.4%). The median size was 3.2 cm. Fifty-five (88.7%) were assessed for functionality and 27 (49.1%) were functional. Among the 62 individuals, 14 (20.2%) had hypercortisolism, 11 (15.9%) had pheochromocytoma, 5 (7.24%) had primary hyperaldosteronism (PA), and 4 (5.7%) had hyperandrogenism including plurihormonal in 7. A mass size of 3.2 cm was of great value in distinguishing functional tumors with a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 66% with an area under the curve of 0.682. A total of 34 (54.8%) patients underwent adrenalectomy. On histopathological examination, Adenoma (44.1%) was the most common followed pheochromocytoma (26.5%), adrenal cysts (8.8%), and Myelolipoma (5.9%). Two (5.9%) incidentalomas were adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC). Eight (53.3%) adenomas were functional with 6 having hypercortisolism (including 1 with hyperandrogenism) and 2 with PA.

Conclusion:

In our experience, the incidence of pheochromocytoma was second most common after adenoma. Since most functional tumors (60%) and all ACCs were ≥4 cm, a thorough biochemical evaluation for hormonal excess and evaluation for malignancy followed by surgery should be considered for lesions, especially ≥4 cm. Thus, we report the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with AI from a single center in South India.

Keywords: Adrenal incidentaloma, adrenalectomy, adrenocortical carcinoma, mild autonomous cortisol secretion, pheochromocytoma, size

Résumé

Contexte:

Les incidents surrénaliens (AIS) sont des néoplasmes relativement rares chez 2% des individus apparemment en bonne santé nécessitant une évaluation de la fonctionnalité et de la malignité.

Objectif:

Nous visions à étudier les profils cliniques, biochimiques et radiologiques des patients présentant IA et résultats histopathologiques de ceux qui subissent une surrénalectomie.

Matériaux et méthodes:

Cette étude rétrospective a inscrit 62 patients AI fréquentant un centre de soins tertiaires dans le sud de l’Inde entre janvier 2016 et octobre 2023. Les détails démographiques, les caractéristiques radiologiques, les fonctionnalités et les données histopathologiques ont été analysés.

Résultats:

Sur 62 patients, les masses totales évaluées étaient 65 indiquant la bilatéralité chez 3 patients. Le ratio féminin: mâle était de 1,69, avec un âge médian de 55 ans (intervalle interquartile: 44–64 ans). 45,1% des individus étaient> 60 ans. L’indication la plus courante pour l’imagerie était l’abdomen de la douleur dans 43 (69,4%). La taille médiane était de 3,2 cm. Cinquante-cinq (88,7%) ont été évaluées pour les fonctionnalités et 27 (49,1%) étaient fonctionnelles. Parmi les 62 individus, 14 (20,2%) avaient un hypercortisolisme, 11 (15,9%) Le phéochromocytome, 5 (7,24%) avait une hyperaldostéronisme primaire (PA), et 4 (5,7%) avaient l’hyperandrogénisme, y compris le plurihormonal dans 7. Une taille de masse de 3,2 cm était d’une grande valeur dans la distinction des tumeurs fonctionnelles avec une sensibilité de 72% et une spécificité distinctive de 66% avec une zone sous la courbe de 0,682. Au total, 34 (54,8%) patients ont subi une surrénalectomie. À l’examen histopathologique, l’adénome (44,1%) était le phéochromocytome suivi le plus courant (26,5%), les kystes surrénaliens (8,8%) et le myélolipome (5,9%). Deux incidentsalomes (5,9%) étaient un carcinome surrénocortical (ACC). Huit (53,3%) adénomes étaient fonctionnels avec 6 souffrant d’hypercortisolisme (dont 1 avec l’hyperandrogénisme) et 2 avec PA.

Conclusion:

D’après notre expérience, l’incidence du phéochromocytome était la deuxième plus courante après l’adénome. Étant donné que la plupart des tumeurs fonctionnelles (60%) et tous les ACC étaient ≥ 4 cm, une évaluation biochimique approfondie pour l’excès hormonal et l’évaluation de la malignité suivie d’une chirurgie doivent être envisagées pour les lésions, en particulier ≥4 cm. Ainsi, nous rapportons les caractéristiques démographiques et cliniques de base des patients atteints d’IA d’un seul centre du sud de l’Inde.

Mots-clés: Carcinome surrénocortical, incident surrénal, surrénalectomie, sécrétion de cortisol autonome légère, phéochromocytome, taille

INTRODUCTION

A clinically unapparent adrenal mass lesion >1 cm discovered serendipitously on imaging excluding lesions that are discovered during screening for hereditary syndromes or extra-adrenal tumors is called an adrenal incidentaloma (AI) as per the definition by the European Society of Endocrinology and European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors (ESE/ENSAT).[1] Masses <1 cm are usually not considered AI.[2] This entity is more common than in ester years due to the rapid advances in radiology such as computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging with their popular utilization in clinical practice.[2] The frequency reported is about 2.3% in an autopsy study, 4% in retrospective CT studies, and 5.8% in oncological series.[3]

There is an increasing prevalence of AI with age reaching up to 10% in the elderly,[4] thus we would expect the prevalence to increase in India with the growing proportion of elderly individuals.

Two common questions that arise following the detection of an adrenal mass raises are, whether the lesion is functional/malignant and the need for adrenalectomy, and simultaneously, answering both questions is imperative.[5]

One of the recent guidelines by the American College of Radiology recommends routine biochemical evaluation for most AI.[6] Should this evaluation in the Indian context be based on the size or characteristic of the lesion is still unanswered as there is a lot of heterogeneity in studies on AI related to the management.[3] Studies of AI in the Indian scenario are insufficient with our study being the third of its kind and the first of its kind in the South Indian population which might answer the above.

Therefore, we conducted this retrospective analysis to evaluate the demographic characteristics and laboratory and imaging findings of AI and follow up the histopathology in those operated to provide greater comprehension into their evaluation and management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This retrospective study was conducted at the Department of Endocrinology, Ramaiah Medical College, Bengaluru. The Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained specifically for this study. Patients who presented with an incidentally detected adrenal mass >1 cm on imaging as per ESE and ENSAT guidelines to Ramaiah Hospitals between January 2016 and October 2023 were included whose data were collected from the hospital registry using words such as AI, adrenal mass, and suprarenal space-occupying lesion. The other details such as clinical presentation including comorbidities such as hypertension/diabetes mellitus, biochemistry, and radiological features were retrieved. Histopathological findings in those who underwent adrenalectomy were collected. Exclusion criteria were (1) clinical symptoms related to the adrenal gland for which the imaging was carried out, (2) extra-adrenal tumors, (3) hereditary syndromes, and (4) initial discovery of a malignancy with adrenal metastasis.

Sixty-two eligible patients hospitalized between January 2016 and October 2023 were enrolled. The imaging technique was not standardized as imaging was done in different hospitals and the patients were referred. Hence, only size and Hounsfield unit (HU) (when available) on unenhanced CT were considered for statistical analysis.

Biochemical evaluation following history and physical examination included the following: Hypercortisolism was assessed using 24-h urine-free cortisol or overnight/low-dose dexamethasone suppression test and adrenocorticotropic hormone. Possible mild autonomous cortisol secretion (MACS) and definitive MACS following overnight dexamethasone suppression test were defined based on cortisol levels which were between 1.8 and 5 mcg/dl and >5 mcg/dl, respectively, in the absence of typical clinical Cushing syndrome.[7] Primary hyperaldosteronism (PA) was diagnosed in patients with hypertension/hypokalemia using an aldosterone–renin ratio followed by confirmatory test in those elevated. Pheochromocytoma was diagnosed based on the concentrations of fractionated metanephrines/normetanephrines in the 24-h urine sample/plasma. Serum testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) were done to assess the hyperfunctioning of zona reticularis.

Chemiluminescence immunoassay was used to analyze all the hormones in the study.

Based on histology in those undergoing adrenalectomy, patients were given a final diagnosis.

Sample size with proper justification

From the literature review in a study by Jekaterina Patrova et al.,[8] it has been observed that 85.4% of all AIs were nonfunctioning adenomas. In the present study, expecting similar results, with 95% confidence level and 10% relative precision, the study requires a minimum of 62 subjects.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics of clinical, biological, and radiological profile and outcomes will be analyzed and summarized in terms of percentage. The Chi-square test would be used to compare the clinical profile and outcome between young versus older age groups, benign versus malignant tumors, small versus large tumors, etc. Kappa statistics would be used to find the agreement between clinical and histopathological diagnoses.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of patients with adrenal incidentaloma

Between January 2016 and October 2023, 62 eligible patients were enrolled. The demographic and clinical data are presented in Table 1. The female: male ratio was 1.69 (62.9% and 37.1%). The median age of patients was 55 years (interquartile range [IQR], 44–64 years), and the age and gender distribution of AI is depicted in Figure 1 with the highest proportion of patients in the age group of >60 years (n = 28, 45.1%). Bilaterality was seen in 3 patients indicating that the total AIs assessed were 65 in number. The proportion of individuals with hypertension was 36 (58.1%) and diabetes was 27 (43.5%). The predominant complaint for which the imaging was done was abdominal pain (n = 43, 69.4%) followed by gastrointestinal and urogenital complaints.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients with adrenal incidentaloma

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Gender, male/female (n) | 23/39 |

| Age (year), median (IQR) | 55 (44–64) |

| Bilaterality | 3 (4.8) |

| Mass size (mm)a, median (IQR) | 32 (23–60) |

| Surgery, n (%) | 34 (54.8) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |

| Hypertension | 36 (58.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 27 (43.5) |

| Reasons for initial imaging, n (%) | |

| Abdominal pain | 43 (69.4) |

| Gastrointestinal complaints | 8 (12.9) |

| Urogenital complaints | 6 (9.7) |

| Respiratory complaints | 4 (6.5) |

| Others | 1 (1.6) |

aThe widest diameter of the largest tumor. IQR=Interquartile range

Figure 1.

Age and gender distribution of patients

Clinical and radiological characteristics of adrenal incidentaloma

The median size of AI along the widest diameter was 3.2 cm with 19% of lesions in <2 cm, 41.4% of lesions between 2 and 3.9 cm, 10.3% in 4–5.9 cm, and 29.3% of lesions >6 cm. 60.4% of lesions were >4 cm and 39.6% of lesions were <4 cm.

HU was analyzed in 32 (51.6%) of patients. Among those analyzed, 13 (40.6%) of patients had HU ≥10. Nine (69.2%) and 4 (30.8%) of AI in the <4 cm and >4 cm groups, respectively, had HU ≥10 which was not statistically significant (P: 0.194).

Bilaterality was seen in 3 (4.8%) of patients with 68 years, 63 years, and 75 years. Bilateral lesions were seen only in men.

Functional status of adrenal incidentaloma

Functionality was assessed in 55 (88.7%) of AIs out of which, 28 (50.9%) were nonfunctional. Among the 27 functional AI cases, pheochromocytoma were 11 (32.3%), MACS were 14 (41.1%), primary hyperaldosteronism(PA) were 5 (14.7%), hyperandrogenism was seen in 4 cases (11.7%). The details regarding the functional status of the tumor are depicted in Table 2 including 7 cases with plurihormonal status.

Table 2.

The functional status of the lesions

| Functional status | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Nonfunctional tumor | 28 (40.5) |

| Mild autonomous cortisol secretion | 14 (20.2) |

| Pheochromocytoma | 11 (15.9) |

| PA | 5 (7.24) |

| Hyperandrogenism | 4 (5.7) |

| Unknown functional status | 7 (10.1) |

PA=Primary hyperaldosteronism

Among 14 patients with MACS, 71.4% had diabetes (P: 0.017) and 71.4% (P: −0.249) had hypertension which was not statistically different from nonfunctioning lesions where 32.1% had diabetes and 60.7% had hypertension (P: 0.575 and 0.281, respectively). The median size of lesion in possible MACS and definitive MACS was 4.2 cm (IQR: 2.2–7.5) and 5.4 cm (IQR: 2.2–10.8) (P: 0.661).

Among 11 patients of pheochromocytoma, 2 (18.1%) were normotensives.

Among 5 patients of PA, 1 (20%) was normotensive.

The distribution of patients according to the diagnosis and comorbidities is depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of subjects according to the diagnosis and comorbidities

| Diagnosis | n (%) | Hypertension, n (%) | Diabetes mellitus, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pheochromocytoma | 11 | 9 (81.8) | 6 (54.5) |

| Hyperfunctioning adenoma | 13 | 9 (69.2) | 10 (76.9) |

| Nonfunctional adenoma | 21 | 12 (57.1) | 5 (23.8) |

| Myelolipoma | 4 | 1 (25) | 1 (25) |

| ACC | 2 | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

| Others | 11 | 4 (36.3) | 4 (36.3) |

ACC=Adrenocortical carcinoma

One out of the 3 bilateral lesions was functional with plurihormonal status (hypercatecholinemia and hypercortisolism). One was nonfunctional, and functional status was not assessed for the other.

The proportion of functional tumors was 25% in lesions <2 cm, 36.4% in 2–3.9 cm, 66.7% in 4–5.9 cm, and 68.8% in >6 cm.

The proportion of functional tumors in <4 cm group and in >4 cm group were 40% and 60% respectively. Whereas, the proportion of nonfunctional tumors in <4 cm group and in >4 cm group were 74.1% and 25.9% respectively. And the difference was statistically significant (P: 0.024). According to tumor size, functionality was significantly more frequent in patients with larger lesions, as depicted in Figure 2. Plurihormonal status was seen in lesions with a median of 6.3 cm (IQR: 2–13.1).

Figure 2.

Distribution of adrenal incidentaloma according to size and functional status (hyperfunctioning vs. nonhyperfunctioning)

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was obtained to analyze that a 3.2 cm cutoff can be used to predict functionality with a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 66%, as depicted in Figure 3, with an area under the curve being 0.682.

Figure 3.

Area under the receiver operating characteristic for the prediction of functionality

The proportion of functional tumors in lesions >10 HU was 6 (46.2%) (P: 0.488).

Histopathological results of adrenal incidentaloma

Among the lesions >4 cm, 78.3% underwent surgical resection.

74.1% of the functional tumors underwent adrenalectomy (one patient with bilateral functional AI preferred unilateral adrenalectomy).

A total of 34 patients underwent resection for the removal of 15 adenomas (44.1%), 9 pheochromocytomas (26.5%), 3 cysts (8.8%), 2 adreno-cortical carcinomas (ACC) (5.9%), 2 myelolipomas (5.9%), 1 diffuse cortical hyperplasia (2.9%), and 1 for adrenocortical neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential (2.9%). One patient on histopathology was diagnosed to have adrenal hemorrhage (2.9%). These figures are depicted in Table 4.

Table 4.

The functional status of the lesions

| Histopathology | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Adenoma | 15 (44.1) |

| Pheochromocytoma | 9 (26.5) |

| Cyst | 3 (8.8) |

| Adrenal cortical carcinomas | 2 (5.9) |

| Myelolipoma | 2 (5.9) |

| Diffuse cortical hyperplasia | 1 (2.9) |

| Adrenocortical neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential | 1 (2.9) |

| Adrenal hemorrhage | 1 (2.9) |

Out of 15 cases of adenoma, a total of 8 cases were functional, 6 cases had cortisol hypersecretion, 3 cases had aldosterone hypersecretion, and 1 case had androgen hypersecretion (including 2 cases with plurihormonal status with 1 lesion cosecreting cortisol and androgens and another lesion cosecreting cortisol and aldosterone).

Both the myelolipomas were found in men.

Both ACCs were in the >6 cm group (10 cm and 9.6 cm) and seen in women (40 years and 52 years).

Among the cases in whom HU was assessed, all myelolipomas and 66.6% of adenomas were found to have <10 HU. All the ACCs and pheochromocytoma had HU >10.

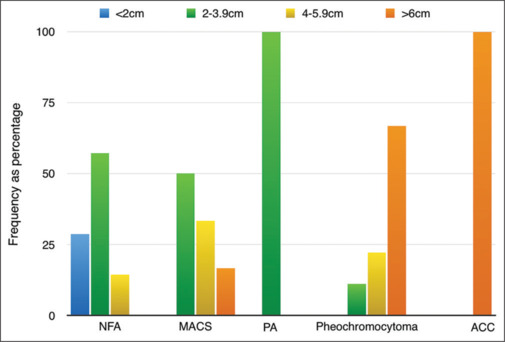

The detailed clinical characteristics of the different tumor types among those operated as categorized by size are represented in Table 5. The proportion of different tumor types according to mass size is presented in Figure 4.

Table 5.

The detailed clinical characteristics among the different tumor types were categorized by size in 34 operated patients

| <2 cm | 2–3.9 cm | 4–5.9 cm | >6 cm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, male/female (n) | 8/3 | 9/15 | 0/6 | 5/12 |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 55 (30–93) | 61.5 (17–76) | 56 (36–69) | 55 (25–74) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 4 (11.8) | 16 (47) | 4 (11.8) | 10 (29.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (11.5) | 12 (46.2) | 3 (11.5) | 8 (30.8) |

| Type of tumor, n (%) | ||||

| Nonfunctional adenoma | 2 (28.6) | 4 (57.1) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| Mild autonomous cortisol secretion | 0 | 3 (50) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (16.6) |

| PA | 0 | 2 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Pheochromocytoma | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 2 (22.2) | 6 (66.7) |

| Myelolipoma | 1 (50) | 0 | 0 | 1 (50) |

| Cyst | 0 | 1 (33.3) | 0 | 2 (66.7) |

| Adrenal cortical carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (100) |

| Diffuse cortical hyperplasia | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Adrenocortical neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100) |

| Adrenal hemorrhage | 0 | 1 (100) | 0 | 0 |

IQR=Interquartile range, PA=Primary hyperaldosteronism

Figure 4.

The proportion of different tumor types according to mass size

DISCUSSION

Among studies from South India, this is the first clinical series of AI reported from a single center in the literature. With the advent of novel technologies and an increasing frequency of imaging, there has been an increase in the detection of AI.

The age distribution was wide with the median age at detection being 55 years, similar to that quoted in the article by Barzon et al.[9] Nearly half were >60 years (45.1%) similar to the study by Bovio et al.[10] With the increase in life expectancy, the aging population has increased. There is also a trend toward more investigations in the elderly contributing to the high proportion in this age group.[3] A few autopsy studies have also detected a higher proportion of cortical nodules with age as seen in our study.[11,12] The increasing prevalence of AI with age has been postulated to be due to arteriosclerotic disease causing local ischemia in turn leading to a compensatory growth and focal nodular proliferation of cortical cells.[13] Similar to the studies by Mantero et al.[14] and Tabuchi et al.,[15] there is a female preponderance in our study, especially in those <60 years. This could be attributed to the higher frequency of abdominal imaging in women than in men.[16]

58.1% and 43.5% of AI had hypertension and diabetes, respectively, as compared to another study where 55.4% had hypertension[16] and another study where 30.9% had diabetes, respectively.[7] This increased proportion could be because aging is associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, or AIs.[17]

Bilaterality was seen in 3 of cases as compared to the previous studies where it was between 7.6% and 7.8%.[3,16] However, in studies with a larger cohort, bilateral lesions were seen in 10% and 15% of cases.[18] The cause of them was pheochromocytoma in one following unilateral adrenalectomy. Functionality was not assessed in another patient with bilateral lesion, and another individual had nonfunctional lesions. They were detected only in men with an age of 68 years, 63 years, and 75 years compared to a study where bilateral lesions were detected with a mean age of 61 years,[19] with a male-to-female sex ratio of 1.55. The size of the widest lesions on the left and right was 2.1 cm and 3.6 cm similar to another study where it was 2.4 cm on the right and 2.8 cm on the left.[20]

The median diameter was 3.2 cm similar to that quoted by Barzon et al.[9] 60.4% of lesions were >4 cm and 39.6% of lesions were <4 cm as compared to the Italian where 64% of lesions were <4 cm.[14] A study by Kim et al. had 8.6% of lesions >4 cm and 91.4% of lesions <4 cm.[16] Most of the women had lesion between 2 and 3.9 cm followed by >6 cm.

HU was assessed only in 51.6% of AIs similar to another study where it was reported only in 41% of lesions.[21] 40.6% and 59.4% of patients had HU ≥ 10 and HU < 10, respectively, similar to the study stated prior where 65% had HU < 10.[21] 69.2% and 39.8% of AIs in the <4 cm and >4 cm groups had HU ≥ 10, indicating that although the size of lesions was <4 cm, many individuals had a higher HU. Reporting of HU can be influenced by the size of the lesion, heterogeneity of the adrenal mass, and the region of interest.[22]

Following the detection of AIs, issues related to functionality and malignancy arise. Regarding the functionality, among 62 patients, functionality was assessed in 55, and we observed that 27 (49.1%) patients had functional tumors comparable to the previous studies where 10%–15% of lesions were functional.[14,23] A study by Li et al. found the proportion of functional tumors as 27.3%.[3] It was also seen that men were found to harbor functioning tumors more than women (57.1% vs. 44.1%) though the total number of lesions in men was less, but the difference was not significant. This was in contrast to a previous study where women had more functional lesions which was also not significantly different.[15] Individuals >60 years had more functional lesions as compared to those <45 years or 45–59 years, P = 0.016, which was again in contrast to the study stated above where younger individuals had more functional lesions.[15]

The proportion of hypertension and diabetes between functional and nonfunctional tumors was 19 (52.8%) and 17 (65.4%), respectively (P = 0.573, P = 0.031) in contrast to the Japanese study[15] where glucose intolerance, cardiovascular disease, and dyslipidemia between functioning and nonfunctioning tumors were comparable with a higher proportion of hypertension in the functional lesions. This could be due to the increase in blood pressure and carotid intima-media thickness even in nonfunctioning tumors warranting a long-term follow-up.[15]

Among the functional tumors, MACS (41.1%) was the most common followed by pheochromocytoma (32.3%), primary hyperaldosteronism (PA) (14.7%), and 11.7% of hyperandrogenism in contrast to the study by Cawood et al.[23] where nonfunctioning lesions were 89.7%, subclinical Cushing syndrome 6.4%, pheochromocytoma 3.1%, and primary aldosteronism 0.6%. In another study with 62 out of 348 lesions with functionality, pheochromocytoma occurred more frequently followed by SCS, and aldosterone-secreting adenoma in 40.3%, 33.9%, and 25.8%, respectively.[16]

This indicates the importance of endocrine workup in a patient with AI.[3]

Following ROC analysis, it was suggested that 3.2 cm cutoff can be used to predict functionality with a sensitivity of 72% and specificity of 66%. This has been the first study as per our knowledge which has analyzed the ROC curve for prediction of functionality in AI and pheochromocytoma and adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) in the >6 cm group indicating the importance of size in the evaluation of functionality similar to a previous study.[3]

11.3% of the total 62 lesions were pleurihormonal with a median size of 6.3 cm with 4 patients having hypercatecholenemia and hypercortisolism, 1 patient having hypercatecholenemia and hyperandrogenism, 1 patient having hypercortisolism and hyperandrogenism, and 1 patient with hypercortisolism.

Among three individuals with bilateral lesions, one had plurihormonal status with hypercortisolemia and hypercatecholinemia. In a study by Pasternak et al., bilateral AI was found to have a higher prevalence of SCS.[20] In the same study by Pasternak et al.,[20] only one patient underwent adrenalectomy, and who was confirmed to have pheochromocytoma similar to our study.

Among the lesions >4 cm, 78.3% underwent surgical resection unlike in a study where only 5.8% of lesions >4 cm underwent adrenalectomy.[16] 74.1% of the functional tumors underwent adrenalectomy as compared to the same study by Kim et al. where 50.7% of functional tumors underwent adrenalectomy.[16]

54.8% underwent adrenalectomy. Among those who underwent surgery, regarding functionality, pheochromocytoma (26.4%) was most common followed by nonfunctioning adrenal adenomas (26.4%) followed by MACS (17.6%) followed by adrenal cysts (8.8%) and myelolipoma (5.8%). However, among pheochromocytoma (26.5%) and adenomas (44.1%) (functional and nonfunctional), adenomas were more common similar to the study by Li et al.[3] where adenomas occurred at a frequency of 53.6% followed by pheochromocytomas (18.5%). Among 14 patients with MACS, 71.4%% had diabetes and hypertension similar to a study where 32.9% had diabetes and 75.8% had hypertension indicating the increased cardiometabolic risk.[7]

Among 11 operated cases of definitive MACS/possible MACS, 6 were adenomas and 1 was adrenal neoplasm of uncertain malignant potential and 4 were cosecreting catecholamines with histopathology being pheochromocytoma, unlike the Shah et al.’s[4] study where 4 MACS were histopathologically myelolipoma. Among the three cases of PA on biochemical evaluation, two were histologically proven to be adenomas whereas one case was diagnosed as myelolipoma.

Among nine patients of histologically proven pheochromocytoma, 22.2% were normotensives similar to the previous study where 20% of pheochromocytomas were normotensives.[4] This entity is usually seen with AI or those detected during familial screening, as the lesions are smaller being less functional.[4] 88.8% of pheochromocytomas were >4 cm which was seen in the Italian study as well.[14]

Out of 15 cases of adenoma, 8 were functional with 6 of MACS, 3 of PA, and 1 with hyperandrogenism.? (total)n an Indian study by Maiti et al., where out of six adenomas, five were functional – two had hypercortisolism, two had hyperaldosteronism followed by one case of hyperandrogenism.[24] All myelolipomas were seen in men, unlike the previous study where they were more common in women.[24]

The proportion of functional tumors in lesions >10 HU was 46.2%, and all pheochromocytomas in whom HU was assessed were >10 HU. In a study by Canu et al., only 0.5% of pheochromocytomas had <10 HU.[25] This indicates the utility of unenhanced attenuated CT to differentiate lipid-poor adenomas from pheochromocytomas.[4] Among 11 out of 15 adenomas in whom HU was assessed, 7 (63.6%) were found to have <10 HU unlike the study by Shah et al.[4] where all adenomas were <10 HU.

Regarding the malignancy, 2 of the operated patients were diagnosed to have ACC contributing to 5.9% of the operated cases as compared to a review done in New Zealand.[23] Both the ACCs were in the >6 cm group which was similar to the study by Angeli et al. where 90% of ACCs were >4 cm.[18] A study by Li et al.[3] predicted the risk of malignancy with a 4.6 cm cutoff with 88.2% sensitivity and 95.5% specificity in contrast to a study by Ye et al. where the cutoff size was 5.4 cm.[26] Altogether, nonfunctioning adenomas were the smallest tumors as compared to malignant lesions which were the largest, though there was some overlap. These findings emphasize that the size of the lesion is a risk for malignancy as comparable to the previous studies[27,28] with studies stating the correlation between tumor size and risk of ACC: 2% risk in AIs <4 cm, 6% in AIs 4.1–6 cm, and 25% in AIs >6 cm.[29] Individuals with ACC were younger women (<60 years) compared to other functional tumors which were more common in >60 years. This was similar to a national survey of Italy with the median age of ACC being 46 years.[14] It has been noted that there is a size underestimation on CT scans ranging from 20% to 47%[9] emphasizing the importance of preoperative assessment of tumor size.

Hence, it has been suggested that surgical resection is generally not required for tumors <4 cm with a low risk of malignancy on imaging.[3] Hence, adrenalectomy should be considered in lesions >4 cm to avoid missing ACC and other functional tumors, especially in younger individuals.

Both the ACCs were >10 HU. This was in line with the study where adrenal masses with unenhanced CT attenuation > 10 HU diagnosed malignancy with a sensitivity of 100%, specificity of 33%, positive predictive value of 72%, and negative predictive value of 100%.[22]

Besides the size and imaging features of the lesion, biochemical evaluation, especially androgens in women and DHEAS, could predict the risk of ACCs which was seen in 1 of our cases. The other patient had normal androgens and DHEAS, indicating that although 40%–60% of ACCs can be functional, the remainder can be nonfunctional,[29] with DHEAS and testosterone being elevated only in 28% and 27% of ACCs.[14] With aging, DHEAS secretion declines physiologically which might interfere with the recognition of reduced DHEAS in elderly individuals.[30] The age of the patient with normal DHEAS was 52 years.

Overall, a detailed review of imaging characteristics and hormonal evaluation usually will be able to differentiate malignant from benign lesions as ACCs are not rare even if majority of lesions are benign similar to the Italian study where the proportion was 4%.[14]

Limitations of our study include the following:

Since it was a retrospective study, some data were unavailable like hormonal evaluation and HU assessment, which decreased the power of analysis

Routine biochemical assessments and CT techniques were not standardized

The clinical and biochemical follow-up of those operated and interval change of size in those not operated was not studied

Because of the small sample size of adrenal tumors, the subgroup analysis was not able to establish statistical significance in many of the cases

Only 34 cases underwent adrenalectomy indicating that many patients were diagnosed by clinical and not pathological evaluation

17-hydroxyprogesterone was not assessed in bilateral lesions.

CONCLUSION

Here, we present the detailed demographic and clinical details of AI related to their functionality and malignancy from a single center in South India. Imaging by CT scan is a valuable screening tool to evaluate its nature followed by biochemical to exclude adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC), MACS, pheochromocytoma, and primary aldosteronism (PA). In those following adrenalectomy, nonfunctional adenomas were found in 20.5%, pheochromocytomas (26.4%) followed by MACS (14.7%), and PA and ACC occurring at the same frequency (5.8%). Plurihormonal status and bilaterality were seen in 11.3% and 4.8% of cases, respectively. The size of lesions was of value in distinguishing functionality and differentiating malignant and benign tumors. Biochemical screening for hypercatecholinemia is mandatory prior to adrenalectomy, especially in lesions >3.2 cm.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fassnacht M, Arlt W, Bancos I, Dralle H, Newell-Price J, Sahdev A, et al. Management of adrenal incidentalomas: European Society of Endocrinology clinical practice guideline in collaboration with the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumors. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;175:G1–34. doi: 10.1530/EJE-16-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JM, Kim MK, Ko SH, Koh JM, Kim BY, Kim SW, et al. Clinical guidelines for the management of adrenal incidentaloma. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2017;32:200–18. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2017.32.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li L, Yang G, Zhao L, Dou J, Gu W, Lv Z, et al. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with adrenal incidentaloma from a single center in China: A survey. Int J Endocrinol. 2017;2017:3093290. doi: 10.1155/2017/3093290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah AN, Saikia UK, Chaudhary BK, Bhuyan AK. Adrenal incidentaloma needs thorough biochemical evaluation – An institutional experience. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2022;26:73–8. doi: 10.4103/ijem.ijem_335_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cuthbertson DJ, Alam U, Davison AS, Belfield J, Shore SL, Vinjamuri S. Investigation and assessment of adrenal incidentalomas. Clin Med (Lond) 2023;23:135–40. doi: 10.7861/clinmed.2023-0042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayo-Smith WW, Song JH, Boland GL, Francis IR, Israel GM, Mazzaglia PJ, et al. Management of incidental adrenal masses: A white paper of the ACR incidental findings committee. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:1038–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prete A, Subramanian A, Bancos I, Chortis V, Tsagarakis S, Lang K, et al. Cardiometabolic disease burden and steroid excretion in benign adrenal tumors: A cross-sectional multicenter study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:325–34. doi: 10.7326/M21-1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patrova J, Jarocka I, Wahrenberg H, Falhammar H. Clinical outcomes in adrenal incidentaloma: experience from one center. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:870–7. doi: 10.4158/EP15618.OR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barzon L, Sonino N, Fallo F, Palu G, Boscaro M. Prevalence and natural history of adrenal incidentalomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2003;149:273–85. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1490273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bovio S, Cataldi A, Reimondo G, Sperone P, Novello S, Berruti A, et al. Prevalence of adrenal incidentaloma in a contemporary computerized tomography series. J Endocrinol Invest. 2006;29:298–302. doi: 10.1007/BF03344099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Commons RR, Callaway CP. Adenomas of the adrenal cortex. Arch Intern Med (Chic) 1948;81:37–41. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1948.00220190045004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russi S, Blumenthal HT, Gray SH. Small adenomas of the adrenal cortex in hypertension and diabetes. Arch Intern Med (Chic) 1945;76:284–91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1945.00210350030005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arnaldi G, Boscaro M. Adrenal incidentaloma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;26:405–19. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantero F, Terzolo M, Arnaldi G, Osella G, Masini AM, Alì A, et al. A survey on adrenal incidentaloma in Italy. Study group on adrenal tumors of the Italian Society of Endocrinology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:637–44. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.2.6372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tabuchi Y, Otsuki M, Kasayama S, Kosugi K, Hashimoto K, Yamamoto T, et al. Clinical and endocrinological characteristics of adrenal incidentaloma in Osaka region, Japan. Endocr J. 2016;63:29–35. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.EJ15-0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim J, Bae KH, Choi YK, Jeong JY, Park KG, Kim JG, et al. Clinical characteristics for 348 patients with adrenal incidentaloma. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2013;28:20–5. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2013.28.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reimondo G, Castellano E, Grosso M, Priotto R, Puglisi S, Pia A, et al. Adrenal incidentalomas are tied to increased risk of diabetes: Findings from a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105:dgz284. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgz284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angeli A, Osella G, Alì A, Terzolo M. Adrenal incidentaloma: An overview of clinical and epidemiological data from the National Italian Study Group. Horm Res. 1997;47:279–83. doi: 10.1159/000185477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalthoum M, Nacef IB, Chida AB, Rojbi I, Mechirgui N, Khiari K. Endocrine Abstracts. Bioscientifica; 2020. Differences between Bilateral and Unilateral Adrenal Incidentalomas. Available from: https://www.endocrine-abstracts.org/ea/0070/ea0070ep19 . [Last accessed on 2023 Dec 03] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasternak JD, Seib CD, Seiser N, Tyrell JB, Liu C, Cisco RM, et al. Differences between bilateral adrenal incidentalomas and unilateral lesions. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:974–8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eldeiry LS, Garber JR. Adrenal incidentalomas, 2003 to 2005: Experience after publication of the National Institutes of Health consensus statement. Endocr Pract. 2008;14:279–84. doi: 10.4158/EP.14.3.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delivanis DA, Bancos I, Atwell TD, Schmit GD, Eiken PW, Natt N, et al. Diagnostic performance of unenhanced computed tomography and (18) F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in indeterminate adrenal tumours. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2018;88:30–6. doi: 10.1111/cen.13448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cawood TJ, Hunt PJ, O’Shea D, Cole D, Soule S. Recommended evaluation of adrenal incidentalomas is costly, has high false-positive rates and confers a risk of fatal cancer that is similar to the risk of the adrenal lesion becoming malignant; time for a rethink? Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;161:513–27. doi: 10.1530/EJE-09-0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maiti M, Sarkar R, Maiti K. Single centre based clinicopathological experience of adrenal tumours including some rare entities. Clin Diagn Res. 2020;14:ER01–4. Available from: https://jcdr.net/article_fulltext.asp?issn=0973-709x&year=2020&volume=14&issue=10&page=ER01 &issn=0973-709x&id=14126 . [Last accessed on 2023 Nov 24] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canu L, Van Hemert JA, Kerstens MN, Hartman RP, Khanna A, Kraljevic I, et al. CT characteristics of pheochromocytoma: Relevance for the evaluation of adrenal incidentaloma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:312–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-01532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye YL, Yuan XX, Chen MK, Dai YP, Qin ZK, Zheng FF. Management of adrenal incidentaloma: The role of adrenalectomy may be underestimated. BMC Surg. 2016;16:41. doi: 10.1186/s12893-016-0154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Park SY, Park BK, Park JJ, Kim CK. CT sensitivities for large (≥3 cm) adrenal adenoma and cortical carcinoma. Abdom Imaging. 2015;40:310–7. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0202-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bin X, Qing Y, Linhui W, Li G, Yinghao S. Adrenal incidentalomas: Experience from a retrospective study in a Chinese population. Urol Oncol. 2011;29:270–4. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherlock M, Scarsbrook A, Abbas A, Fraser S, Limumpornpetch P, Dineen R, et al. Adrenal incidentaloma. Endocr Rev. 2020;41:775–820. doi: 10.1210/endrev/bnaa008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terzolo M, Stigliano A, Chiodini I, Loli P, Furlani L, Arnaldi G, et al. AME position statement on adrenal incidentaloma. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;164:851–70. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]