Abstract

Periodic paralysis is a rare, dominantly inherited disorder of skeletal muscle in which episodic attacks of weakness are caused by a transient impairment of fiber excitability. The attacks of weakness are often elicited by characteristic environmental triggers, which was the basis for clinically delineating subtypes of periodic paralysis and is an important distinction for optimal disease management. All forms of familial periodic paralysis are caused by mutations of ion channels, often selectively expressed in skeletal muscle, that destabilize the resting potential. The missense mutations usually alter channel function from gain-of-function changes, rather than producing a complete loss-of-function null. The knowledge of which channel gene harbors a variant, whether that variant is expected to (or known to) alter function, and how altered function impairs fiber excitability aides in the interpretation of patient signs and symptoms, the interpretation of gene test results, and in how to optimize therapeutic intervention for symptom management and improve quality of life.

Keywords: muscle, channelopathy, myotonia, sodium channel, calcium channel, potassium channel, SCN4A, CACNA1S, KCNJ2

4.1. Introduction

Periodic paralysis is a disorder of skeletal muscle, where the cardinal feature is recurrent episodes of muscle weakness with variable duration and frequency (Venance et al., 2006; Statland et al., 2018). A familial inheritance pattern was recognized over a century ago (Shakhnowitsch, 1882), and several variants have been delineated on the basis of environmental triggers that provoke an episode of weakness and the associated changes in serum potassium level (Biemond and Daniels, 1934; Tyler et al., 1951). Early clinical investigations established the cause for episodic weakness with reduced muscle tone as a reversible impairment of muscle fiber excitability (Westphal, 1885). In the 1980s, landmark studies by Frank Lehmann-Horn and colleagues identified anomalous ionic currents in microelectrode recordings from muscle biopsies of patients with periodic paralysis (Lehmann-Horn et al., 1981; Lehmann-Horn et al., 1983). This insight paved the way for screening specific ion channel genes (Fontaine et al., 1990) and led to the discovery of mutations in the sodium channel gene (SCN4A) as the first voltage-activated ion channelopathy in humans (Ptacek et al., 1991; Rojas et al., 1991). Subsequent work has shown that all clinical varieties of periodic paralysis are ion channelopathies (reviewed in Lehmann-Horn and Jurkat-Rott, 1999; Fialho and Hanna, 2007; Cannon, 2015), most often as a result of missense mutations, in genes coding for the main pore-forming subunits of sodium channels (SCN4A), calcium channels (CACNA1S), or potassium channels (KCNJ2). This introductory section summarizes the many elements in common with all forms of periodic paralysis, even with this molecular diversity.

4.1.1. Clinical presentation

The primary symptom in periodic paralysis is recurring episodes of muscle weakness (Statland et al., 2018; Lehmann-Horn et al., 2004; Fialho et al., 2018). The onset is gradual, often with a premonitory sense of apprehension, fatigue or muscle paresthesias, that progresses over minutes to a maximal loss of strength, followed by a gradual spontaneous recovery over tens of minutes to hours. Weakness is usually symmetrical, and may be global or focal. Severity for the loss of strength is variable, and may either be mild or render the patient quadriparetic, unable to sit or even raise a limb against gravity. In a severe attack, muscle tone is diminished and tendon reflexes are absent. Muscle groups for respiration, swallowing, speech, and extraocular movement are largely spared. Respiratory compromise is uncommon (Kil and Kim, 2010), although fatal events have been reported (Holtzapple, 1905) and a myotonic variant of infancy presents with laryngospasm and ventilatory failure (Lion-Francois et al., 2010; Singh et al., 2014; also see Chapter 3 Inherited Myotonias). Muscle pain is commonly reported, either during or after recovery from an attack of weakness (Charles et al., 2013) and may impact quality of life (Giacobbe et al., 2021).

Episodes of weakness in periodic paralysis are often provoked by physical activity or environmental triggers (Lehmann-Horn et al., 2004). Sustained vigorous exercise is commonly reported to be a trigger, with preserved strength of active muscles and weakness occurring within minutes of stopping to rest. On the other hand, an impending attack can often be prevented or attenuated by mild exercise. Other frequently reported triggers include cold environment, stress, alcohol consumption, and dietary patterns (carbohydrate rich foods for hypokalemic periodic paralysis, HypoPP, versus fasting for hyperkalemic periodic paralysis, HyperPP). The frequency of attacks is highly variable, even for members of the same family, and ranges from a few in a lifetime to multiple episodes per week. Episodes of symptomatic weakness usually begin in childhood or adolescence, although the diagnosis is often delayed for years to a decade or more because the physical examination is normal in between attacks. For many patients the frequency of attacks diminishes with age, and is replaced by a chronic state of mild weakness that later progresses to myopathy with permanent muscle weakness, especially of proximal muscles, and may cause loss of ambulation (Links et al., 1990; Charles et al., 2013).

The inheritance pattern is autosomal dominant in all forms of familial periodic paralysis, although the penetrance for the acute attacks is lower in women with HypoPP (Links et al., 1994; Elbaz et al., 1995). Periodic paralysis occurs in all populations worldwide, but is a rare disorder with a prevalence of about 1 per 100,000 (Horga et al., 2013; Stunnenberg et al., 2018). A positive family history is usually found, but de novo mutations have been documented and so a lack of affected relatives does not exclude the diagnosis (Sung et al., 2012; Elbaz et al., 1995).

4.1.2. Shared pathomechanism for episodic weakness in all forms of periodic paralysis

In all forms of periodic paralysis – familial, sporadic, and associated with thyrotoxicosis – the transient impairment of contractile force is caused by an anomalous sustained depolarization of the muscle fiber. The interictal resting potential of skeletal muscle is normally −85 mV to −95 mV; whereas during an episode of weakness is −45mV to −60 mV in affected muscles (Lehmann-Horn et al., 1987; Rüdel et al., 1984; Creutzfeldt et al., 1963). This depolarized shift of is sufficient to produce substantial inactivation of voltage-dependent sodium channels (availability reduced to 50% or less of normal). In a manner analogous to the depolarizing muscle relaxant succinylcholine, fiber excitability is compromised and the failure to generate a propagated action potential produces flaccid weakness. This pathomechanism is consistent with the hypotonia, areflexia, and loss of electrical excitability (motor unit activity with the needle EMG or amplitude of the evoked compound muscle action potential) during a severe attack of periodic paralysis (Shy et al., 1961).

The challenge for the management of patients with periodic paralysis, and for further improvements in therapeutic intervention, is to understand the basis for the intermittent depolarization and the relationship to trigger factors that often provoke an attack. Indeed, differences in the trigger factors formed the basis for delineating the clinical variants of familial periodic paralysis (Biemond and Daniels, 1934; Tyler et al., 1951) and subsequently was found to be associated with which ion channel gene harbored a mutation (Ptacek et al., 1991; Ptacek et al., 1994; Tawil et al., 1994) and which functional class of ion channel defect occurred as a consequence of the genetic variant (Cannon, 2018). While all forms of periodic paralysis are ion channelopathies of skeletal muscle, differences in the pathomechanism for inducing the depolarized shift of readily account for whether the clinical presentation will be HypoPP or HyperPP, and that the latter may be accompanied by myotonia (Cannon, 2015). On the other hand, episodes of weakness may occur without provocation or in association with serum [K+] in the normal range (3.6 to 5.2 mmol/l) for any variant of periodic paralysis, which may confound the effort to accurately diagnose the type of periodic paralysis.

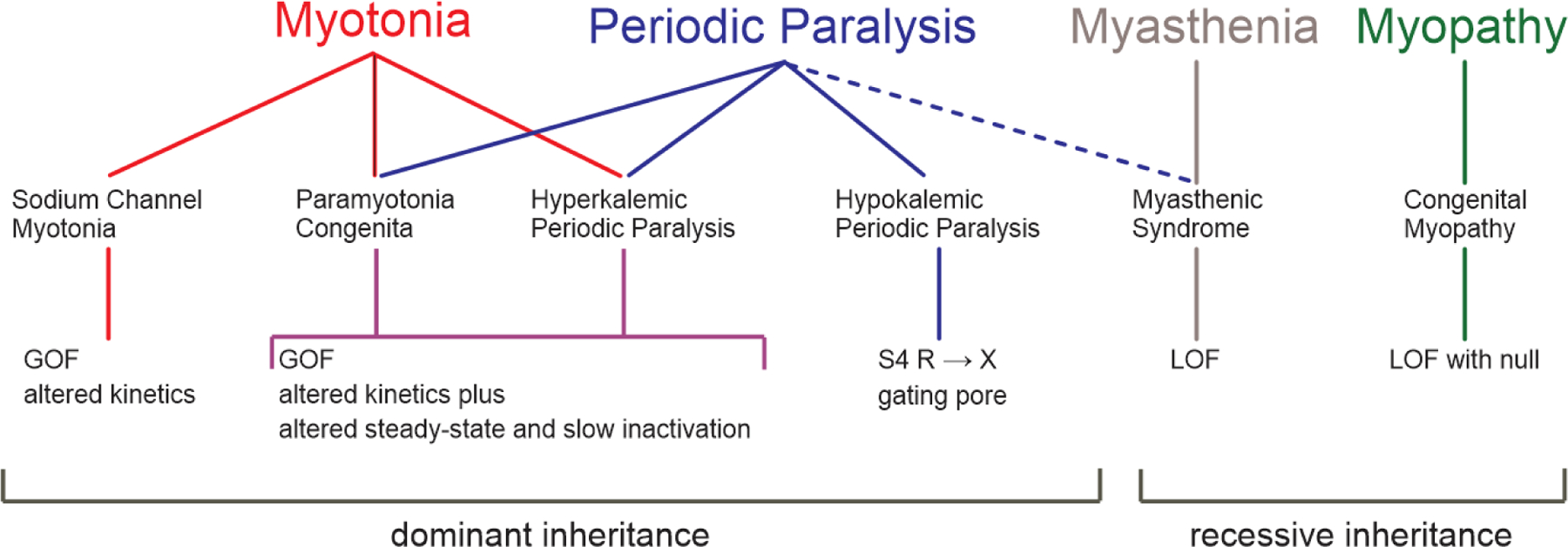

4.1.3. Clinical spectrum of non-dystrophic myotonia and periodic paralysis

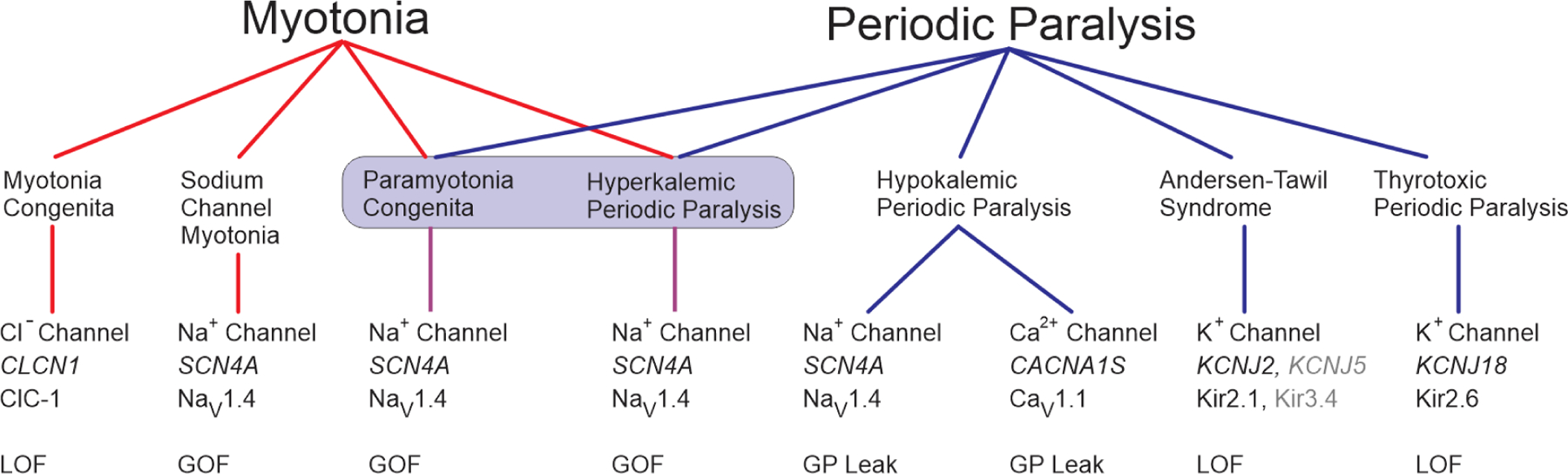

The disorders of voltage-activated ion channels expressed in skeletal muscle present with a mixture of clinical features along a continuous spectrum from non-dystrophic myotonia to periodic paralysis (Figure 1). Consistent genotype-phenotype associations are found for these clinically delineated syndromes (Figure 1, bottom row), with several distinct disorders being allelic variants of SCN4A having functionally different defects of NaV1.4 (Cannon, 2015). Conversely, the cause of HypoPP is genetically heterogenous, with missense mutations in either a calcium channel gene (CANCA1S) or a sodium channel gene (SCN4A) (Ptacek et al., 1994; Bulman et al., 1999; Sternberg et al., 2001).

Figure 1.

Spectrum of diseases and associated gene defects for ion channelopathies of skeletal muscle. The clinical presentation ranges from myotonia (left) to periodic paralysis (right) with diseases in the center for which both myotonia and periodic paralysis may occur in the same patient. Paramyotonia congenita and hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (shaded box) are highly overlapping diseases for which features typical of either condition may occur for different affected members in a single family. The row below each disease indicates the channel name, gene name, and nomenclature for the channel protein subunit. KNCJ5 and Kir3.4 are listed in gray because this is an ultra-rare cause of Andersen-Tawil syndrome. Abbreviations: LOF loss-of-function, GOF gain-of-function, GP gating pore.

Myotonia congenita (MC) lies at one extreme (Figure 1, left) for which patients have dominantly inherited (Thomsen type) or recessive (Becker type) myotonia without periodic paralysis (see Chapter 3 Inherited Myotonias). Both inheritance patterns are caused by mutations of the ClC-1 chloride channel encoded by CLCN1 (Steinmeyer et al., 1991; Koch et al., 1992; Suetterlin et al., 2021). A brief impairment of contractility, lasting less than 5 min, may occur in MC with initial forceful movement after a period of rest (Ricker et al., 1978), but this phenomenon is clearly different from the prolonged episodes of weakness in periodic paralysis. Brief plateau depolarization of , sufficient to cause weakness, has been observed in animal models of MC (recessive CLCN1 null or pharmacological block of ClC-1) and implicated contributions from Na+ and Ca2+ currents for initiating and maintaining the depolarization, respectively (Myers et al., 2021).

Another dominant form of non-dystrophic myotonia is associated with missense mutations of the pore-forming subunit of the skeletal muscle sodium channel, NaV1.4, encoded by SCN4A (Mitrovic et al., 1995). Multiple clinical variants that range from mild stiffness with muscle pain, to debilitating stiffness that impedes respiration (Gay et al., 2008), or with neonatal hypotonia and life-threatening laryngospasm are allelic disorders of SCN4A. By definition, none include periodic paralysis as a clinical feature. Collectively, these disorders are referred to as the “sodium channel myotonias” (SCM) and include subtypes such as potassium-aggravated myotonia (Heine et al., 1993), fluctuant myotonia (Ricker et al., 1994), and severe neonatal episodic laryngospasm (Singh et al., 2014).

Paramyotonia congenita (PMC) and hyperkalemic periodic paralysis (HyperPP) have extensive overlap of clinical features (Figure 1, center) and are caused by similar gain-of-function defects arising from missense mutations of NaV1.4 (Cannon, 2018; Lehmann-Horn et al., 1981). The notable feature of this group is that both myotonia (a disorder of anomalously enhanced fiber excitability) and periodic paralysis (transient failure of fiber excitability) may occur in the same patient. The predominant symptom in PMC is myotonic stiffness, usually aggravated by cold, with infrequent episodes of weakness. Patients with HyperPP present with recurrent episodes of weakness, frequently associated with elevated [K+], and also may have myotonia that often becomes symptomatic at the onset of an episode of weakness.

Hypokalemic periodic paralysis (HypoPP) presents with recurrent episodes of weakness, usually in the setting of low serum [K+] (Lehmann-Horn et al., 2004). Myotonia is not a feature of HypoPP. HypoPP was initially associated with missense mutations of the skeletal muscle calcium channel, CaV1.1, encoded by CACNA1S (Ptacek et al., 1994; Jurkat-Rott et al., 1994), and subsequently missense mutations were also identified in the sodium channel SCN4A (Bulman et al., 1999; Matthews et al., 2009; Sternberg et al., 2001). Clinically, patients with HypoPP arising from a mutation in either channel are indistinguishable. The HypoPP mutations occur at homologous loci within either channel (the voltage-sensor domain) and cause an identical functional defeat (an anomalous leakage current).

The Anderson Tawil Syndrome (ATS) is unique amongst the muscle channelopathies because additional organ systems are affected (see Chapter 5 Anderson Tawil Syndrome) (Tawil et al., 1994; Sansone et al., 1997). The symptom complex includes dyskalemic periodic paralysis (often HypoPP-like (Sansone et al., 1997), but HyperPP-like described as well (Tawil et al., 1994)), cardiac arrhythmia, and skeletal anomalies: clinodactyly, short stature, characteristic facial features. ATS is caused by loss-of-function mutations of a potassium channel (Kir2.1 encoded by KCNJ2 (Plaster et al., 2001), and is rarely secondary to inhibition of Kir2.1 by a variant of Kir3.4 encoded by KCNJ5 (Kokunai et al., 2014)). Unlike the skeletal muscle-specific expression for CLCN1, SCN4A, and CACNA1S; KCNJ2 is expressed in multiple tissues including skeletal muscle, heart, and bone.

The episodes of weakness in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis (TPP) are similar to those of HypoPP, including ictal hypokalemia and the absence of myotonia (Chen et al., 1965). The attacks of weakness occur in the setting of hyperthyroidism, although patients may not have clinical signs of thyrotoxicosis (McFadzean and Yeung, 1967). Mutations in a potassium channel gene, KCNJ18, are associated with TTP (Ryan et al., 2010), but this occurs for a small minority of cases.

4.1.4. Approaches to diagnosis in periodic paralysis

The approach for establishing a diagnosis of periodic paralysis is similar for all of the disorders illustrated along the clinical spectrum in Figure 1. The primary symptom in periodic paralysis is recurrent episodes of weakness beginning in the first or second decade, with a gradual onset, spontaneous recovery after minutes to hours, and characteristic trigger factors as described above in 4.1.1. Video documentation by the patient’s family is helpful because the attack may have resolved, and motor function may be normal between episodes in those who have not progressed to proximal myopathy with permanent weakness. Manual muscle testing should be performed to establish a baseline and to document any myopathic features. Examine the patient for signs of action myotonia, after voluntary contraction of the hands or eyelids or when attempting to quickly rise from a chair and walk after sitting motionless for 15 minutes. Cold-induced myotonia may be manifest as dysarthria after sipping a cold drink with a straw. Percussion myotonia may be elicited by directly tapping the muscle with a reflex hammer.

The ictal serum K+ may be low (< 3.5 mmol/L) suggesting HypoPP, high (> 4.5 mmol/L) suggestive of HyperPP, or in the normal range which does not exclude a diagnosis of periodic paralysis. With secondary HypoPP the serum K+ is low (often < 2.5 mmol/L) when the patient is symptomatic. Between episodes of weakness, the serum K+ is usually in the normal range in all forms of familial periodic paralysis. With the initial evaluation for the possibility of periodic paralysis, thyroid function studies should be performed to check for TPP, especially in males with no family history of periodic paralysis. Provocative testing, with a glucose plus insulin challenge for HypoPP or with an oral K+ challenge in HyperPP, is potentially dangerous and no longer used in clinical practice.

A screening electrocardiogram should be performed in all patients with a presentation of periodic paralysis to check for a prolonged QT interval or prominent TU-waves that would support a diagnosis of ATS.

All forms of periodic paralysis are dominantly inherited, and so there usually is a history of other similarly affected family members. The penetrance of the episodic weakness phenotype may be reduced for women (Links et al., 1994), and de novo mutations are well documented in probands (Elbaz et al., 1995); either of which may cause a “negative” family history.

Genetic testing by next-generation sequencing of candidate genes (CACNA1S, SCN4A, and KCNJ2) is now routinely performed in the evaluation for familial periodic paralysis (Vivekanandam et al., 2020). When myotonia is present, CLCN1 should also be screened, and the possibility of myotonic dystrophy should be investigated by testing for expansion of CTG repeats in DMPK and CCTG repeats in CNBP. Analysis of KCNJ18 may also be considered in the evaluation of sporadic periodic paralysis (see 4.4 below) but is seldom needed in the evaluation of TPP because the thyroid function test always shows hyperthyroidism. The presence of a pathogenic variant in CACNA1S and SCN4A is highly informative and is often of great value in distinguishing between HypoPP and HyperPP, which despite the historical precedence for a distinction based on serum K+ is often difficult to document. Almost all HypoPP mutations are missense substitutions at arginine residues in S4 transmembrane segments (Matthews et al., 2009), which not only helps to distinguish HypoPP from HyperPP or ATS, but also adds to the confidence of excluding a variant of unknown significance in the genetic evaluation of a possible case of HypoPP. About 10%- 30% of patients who meet clinical criteria for a diagnosis of periodic paralysis do not have a pathogenic variant in CACNA1S, SCN4A, or KCNJ2.

Clinical neurophysiological testing adds important information in the assessment of periodic paralysis. The needle EMG may show myotonic discharges, even in the absence of signs or symptoms of myotonic after-contractions. Convincing evidence of myotonia (discharges waxing and waning in frequency and amplitude, increased activity after voluntary contraction or provoked by percussion or needle movement) is inconsistent with a diagnosis of HypoPP or ATS, and supports a diagnosis of HyperPP or PMC. Exercise-induced changes in the compound muscle action potential (CMAP) with periodic paralysis were initially described by McManis et al. (1986) and later refined by Fournier et al. (2006). Two protocols were developed: (1) the short-exercise test with a 10–20 sec maximal contraction (Streib et al., 1982) after which the CMAP was monitored for 60 min, (2) the long-exercise test with a 5 min maximal contraction (including short rests every 30 sec) after which the CMAP was recorded every minute for 5 minutes and then every 5 minutes thereafter for a total of 45 minutes. The long-exercise test is the more sensitive one for detecting susceptibility to periodic paralysis, defined as a ≥ 40% decrease in CMAP amplitude (peak-peak) or ≥ 50% in area. With these thresholds, the sensitivity was 70% with a specificity of 98% (Simmons et al., 2018; Ribeiro et al., 2022). In a cohort of genetically-confirmed patients, five patterns were defined (Fournier et al., 2004) with a late decrease alone most often found in HypoPP (pattern V), an early increase follow by a late decrease in HyperPP (pattern IV), or a rapid onset decrease that persisted for minutes in PMC (pattern I). The low cost and broad accessibility of next-generation sequencing has made genetic testing the first-line modality for laboratory confirmation of periodic paralysis, with the added precision of defining the sub-type (Vivekanandam et al., 2020). The CMAP long-exercise test still has an important role, however, for those cases in which the genetic screen returns a VUS or no variant (up to 30% of clinically defined cases) or in cases where the episodes of weakness are atypical for periodic paralysis and confirmation is sought for a pathomechanism based on transient reduction of muscle excitability.

4.1.5. Overview of therapeutic intervention in periodic paralysis

Several recent reviews provide details and specific treatment plans for the management of episodic attacks of weakness in periodic paralysis (Jitpimolmard et al., 2020; Statland et al., 2018). The discussion herein presents an overview of the principles that form the basis for symptom management, and new investigational approaches are described in the sections below on specific variants of periodic paralysis.

A change in life-style to minimize triggering events is the first-line approach in symptom management for all types of periodic paralysis. Adjustment of physical activity level is often most effective; either resuming a modest level of exercise to curtail an impending attack or warming down after vigorous exercise to prevent the initiation of an episode. Reducing stress levels (emotional and physical) and similarly avoiding drug preparations that contain adrenergic agents (e.g. epinephrine in local anesthetics) is especially helpful in HypoPP. Dietary adjustments are also effective: avoiding carbohydrates, staying well-hydrated and avoiding high-Na+ foods, or ingesting high-K+ containing foods for HypoPP; avoid fasting and use a carbohydrate snack to abort an attack of HyperPP.

Medications may be necessary to optimize quality of life in patients with periodic paralysis. Oral K+ supplements and K-sparing diuretics (e.g. eplerenone) are used for HypoPP, whereas K-wasting diuretics (e.g. hydrochlorothiazide) are used for HyperPP (Lehmann-Horn et al., 2004). Beta-adrenergic inhalants may be used to hasten recovery from an episode of HyperPP (Hanna et al., 1998). If these measures are inadequate, then chronic administration of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g. acetazolamide) may be used prophylactically to reduce the frequency and severity of attacks for both HypoPP and HyperPP (Griggs et al., 1970; Matthews et al., 2011; Tawil et al., 2000). If myotonic stiffness is the more problematic symptom, then use-dependent sodium channel blockers (e.g. mexiletine) may provide relief (Statland et al., 2012).

Effective intervention to minimize or prevent late-onset permanent muscle weakness has not been established. While a causal relationship between the severity and frequency of acute episodes of weakness and the risk of developing has not been established, the general recommendation is to optimize a life-style that minimizes these attacks and maintain a healthy level of physical activity.

4.2. Hypokalemic periodic paralysis

4.2.1. Clinical features and diagnosis (HypoPP)

Hypokalemic periodic paralysis is the most prevalent form of familial periodic paralysis, although there may be an ascertainment bias because the episodes of weakness tend to be more severe and more prolonged than for HyperPP and so patients with HypoPP are more likely to seek medical care. The onset of symptoms is usually in adolescence, but is variable and ranges from childhood to the third decade of life (Miller et al., 2004). The inheritance mode is dominant, but interpretation of the family history may be complicated by de novo mutations and because the penetrance of the episodic weakness trait may be reduced for females (Links et al., 1994; Elbaz et al., 1995).

An episode of weakness in HypoPP typically lasts for hours to a day or longer. The severity is variable and may progress to full quadriparesis with an inability to stand, sit, or even reposition in bed without assistance. Attacks are often triggered by rest after exercise, ingesting carbohydrate-rich foods, stress, alcohol, or intercurrent illness (e.g. in the setting of K+ loss from diarrhea). The presence of symptomatic or latent myotonia (detectable by needle EMG, but asymptomatic) is considered an exclusionary criterion for the diagnosis of HypoPP (Statland et al., 2018).

4.2.2. Ion channel mutations and pathophysiology (HypoPP)

Most cases of HypoPP are caused by missense mutations of CACNA1S (Jurkat-Rott et al., 1994; Ptacek et al., 1994; Fontaine et al., 1994) encoding the pore-forming subunit of the CaV1.1 calcium channel (also named the dihydropyridine receptor). The pore-forming subunit of the voltage-gated sodium channel in skeletal muscle, NaV1.4 encoded by SCN4A, is a second disease gene in HypoPP, albeit at a much lower frequency (Sternberg et al., 2001; Bulman et al., 1999). Pathogenic variants of CACNA1S are found in about 70% to 80% of HypoPP patients, and mutations of SCN4A are in about 10% (Stunnenberg et al., 2018; Horga et al., 2013).

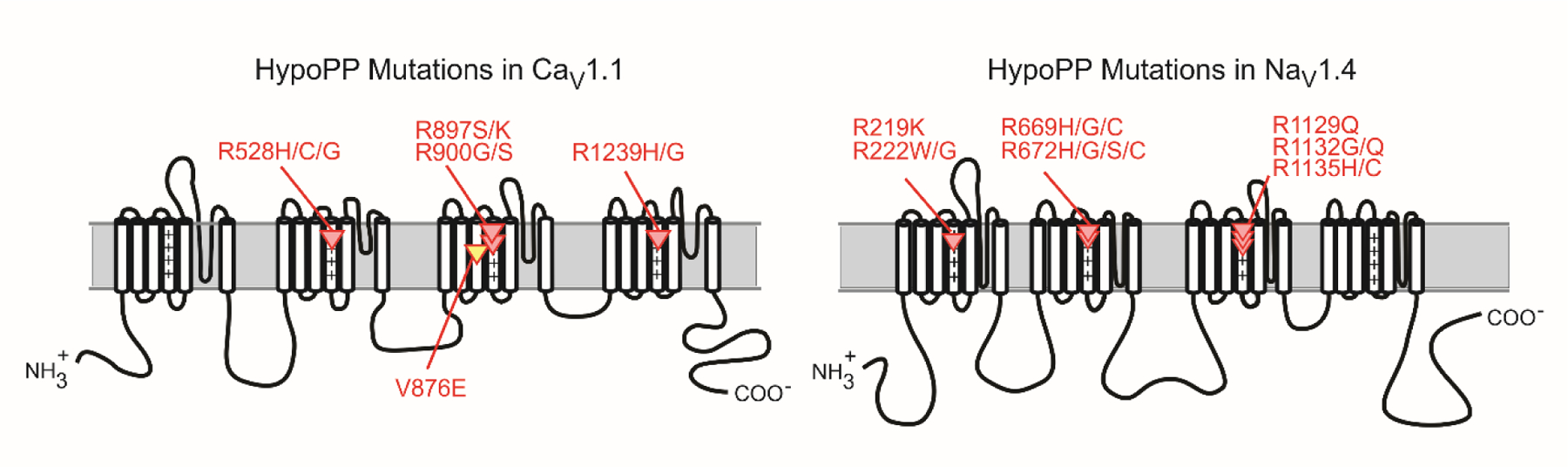

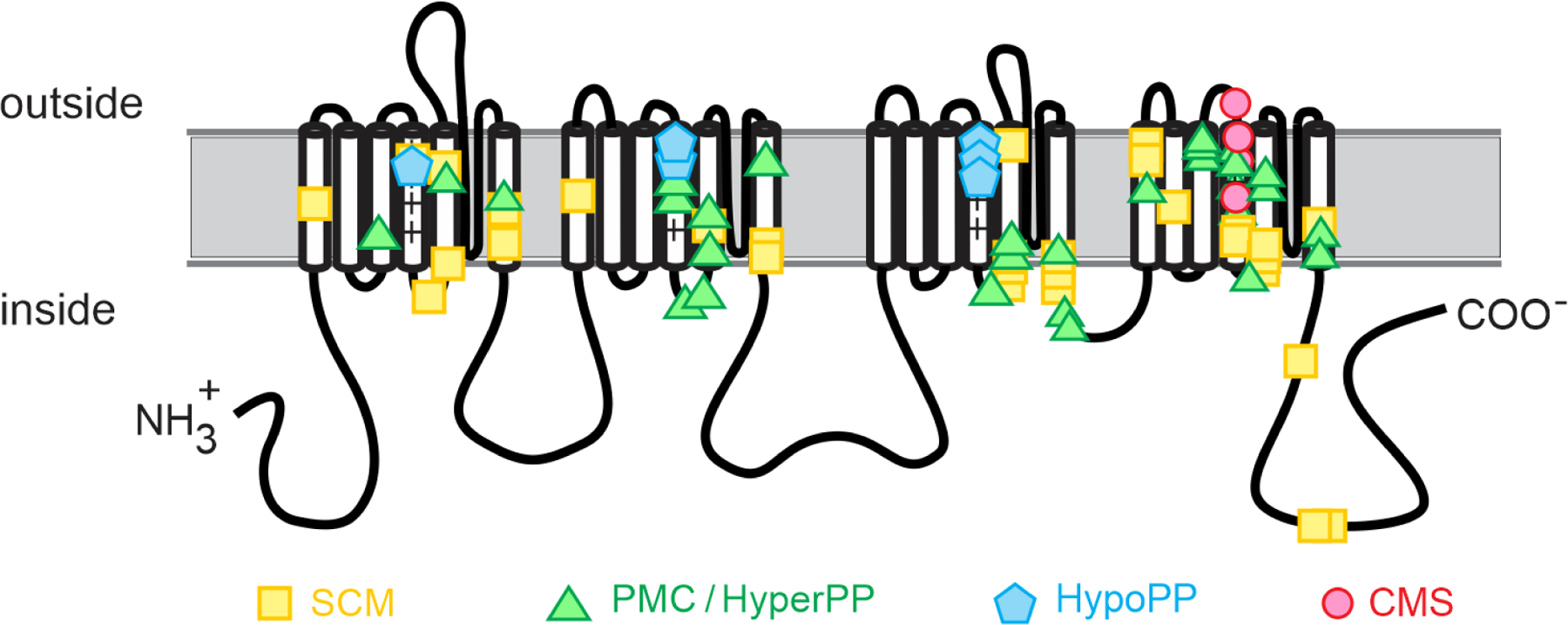

Remarkably, almost all HypoPP mutations occur at arginine residues in the S4 transmembrane segments of voltage-sensor domains (Figure 2) in CaV1.1 or NaV1.4 (Matthews et al., 2009). Nine of the 10 HypoPP mutations in CaV1.1 are missense substitutions at arginine residues in S4 segments, with the one exception being V876E in the S3 transmembrane segment of the voltage sensor for domain II (Ke et al., 2009). All 15 HypoPP mutations of NaV1.4 are missense substitutions at arginine residues in S4 segments. With 24 of the 25 established HypoPP mutations being missense substitutions at arginine residues in S4 segments, it is unlikely that a rare variant of unknown significance that does not adhere to this pattern will be pathogenic for susceptibility to HypoPP. A few of the more prevalently occurring mutations in CACNA1S (R528H and R1239H) account for approximately 70% of genetically established HypoPP cases, and the most common HypoPP mutation in SCN4A is R672H (Stunnenberg et al., 2018; Horga et al., 2013; Sasaki et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2004).

Figure 2.

HypoPP mutations in CaV1.1 and NaV1.4. Schematic representations for the membrane-folding topology of the CaV1.1 (left) and NaV1.4 (right) channel subunits illustrate the clustering of HypoPP missense mutations in S4 segments of voltage sensor domains. The V876E mutation in CaV1.1 (yellow) is the only exception to the pattern of R → X missense substitution for these 25 HypoPP mutations. The “+” symbols emphasize the repeating pattern of positively charged amino acids (usually arginine = R, occasionally lysine = K) in S4 segments.

The consistent pattern of R→X missense substitutions in S4 segments of CaV1.1 or NaV1.4 produces a common functional defect that causes susceptibility to episodes of anomalous depolarization and weakness in HypoPP (Cannon, 2018; Cannon, 2015). HypoPP mutant channels are “leaky”, and thereby allow a small inappropriate influx of sodium current when the fiber is at rest (Sokolov et al., 2007; Struyk and Cannon, 2007). The leak pathway is not via the conventional ion-conducting pore of the channel. Instead, the mutation in the S4 segment creates an aberrant ion conduction pathway in the “gating pore” that normally functions to allow motion of the S4 helix (without an ion leak) during voltage-dependent activation of the “gate” that regulates opening / closing of the channel pore. A growing body of experimental evidence strongly supports the notion that the anomalous gating pore leak is the critical channel defect in HypoPP (Cannon, 2010). Gating pore currents have been detected for 11 different HypoPP mutations of NaV1.4 (Sokolov et al., 2007; Francis et al., 2011; Struyk et al., 2008; Struyk and Cannon, 2007; Bayless-Edwards et al., 2018) and for 6 different HypoPP mutations in CaV1.1 (Wu et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2021), including the exception to the R→X pattern with the V876E mutation (Fuster et al., 2017). Moreover, the gating pore leak has similar functional properties for HypoPP mutations of both CaV1.1 and NaV1.4, probably because of evolutionary conservation of the voltage-sensor domains. This commonality explains how mutations in either of two ion channels that serve very different functions in muscle can produce susceptibility to the same clinical phenotype, HypoPP.

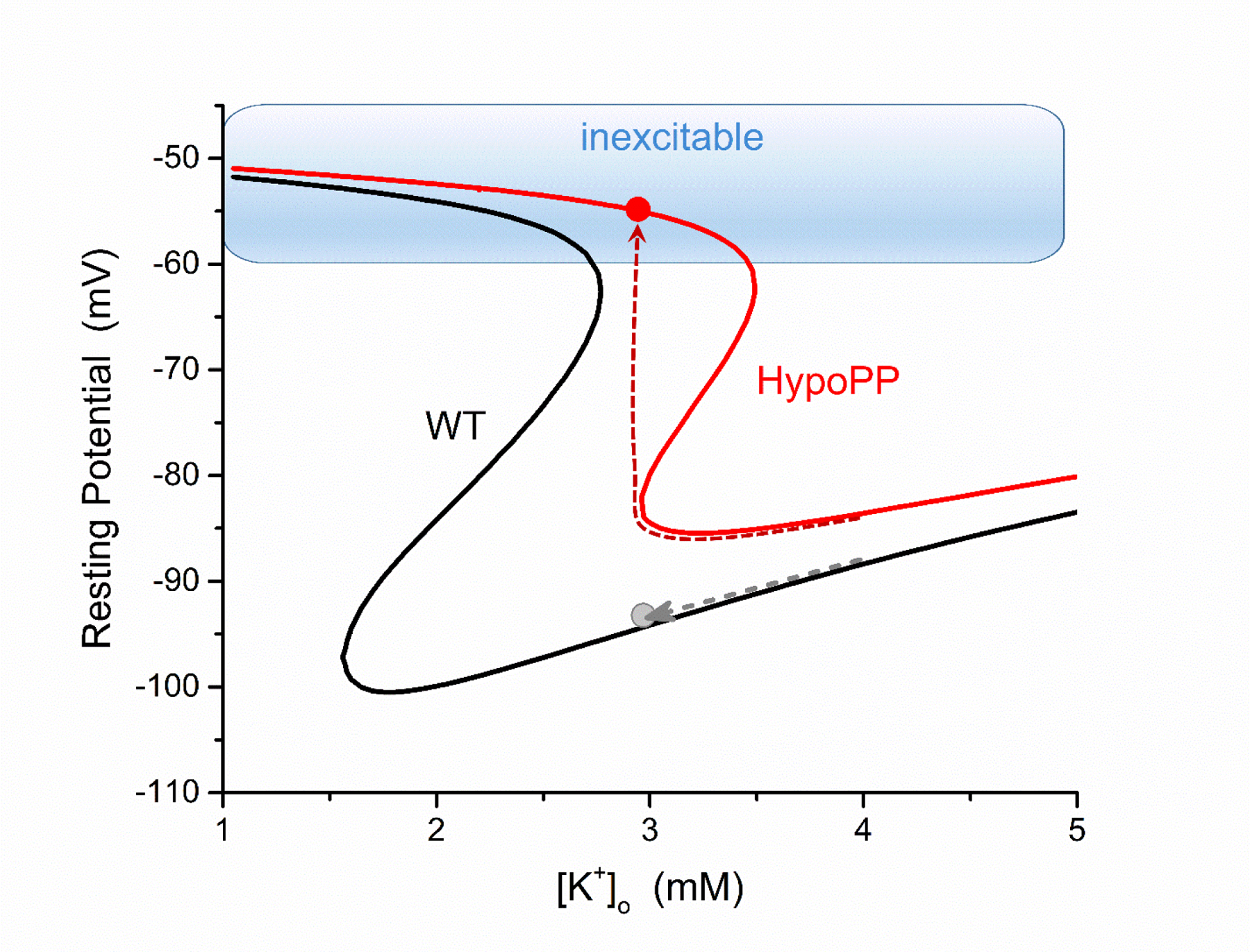

Why does the gating pore leakage current cause anomalous depolarization of , and therefore weakness, in the setting of hypokalemia? The conventional view is that hypokalemia will hyperpolarize of excitable cells because the equilibrium potential for K+, , becomes more negative. In normal skeletal muscle, lowering the [K+] does initially hyperpolarize , but at extremely low levels < 1.5 mmol/L, the fiber depolarizes (Figure 3). This unexpected depolarization occurs because the normal mechanism by which sets (namely, the inward-rectifying K+ conductance) fails at these extremely low, unphysiological, [K+] of about 1.5 mmol/L. In HypoPP fibers, the gating pore current shifts the K-dependent anomalous depolarization of into the low-normal physiological range (e.g. 2.5 to 3.5 mmol/L, see Figure 3), even though the magnitude of the gating pore current is small (the “leak” is about 1% of the normal resting conductance of the fiber). Moreover, the system has “hysteresis” whereby after a depolarization of in low-normal K+ for HypoPP fibers, recovery to the normal requires an increase of [K+] significantly above the level that initiated the “attack”. This explains how inappropriate depolarization of , which will partially inactivate Na+ channels and suppress excitability, can cause an attack of weakness in HypoPP when the venous [K+] is in the normal range.

Figure 3.

Model simulation of the muscle fiber resting potential as a function of extracellular [K+] for a wild type (WT, black) and a HypoPP (red) fiber. In simulated HypoPP fibers (either a CaV1.1 or NaV1.4 mutation), the gating pore leakage current causes a rightward shift of the relation. Starting from a normal [K+] of 4 mmol/L, both fibers are polarized and excitable. As the extracellular [K+] is reduced (dashed lines), the HypoPP fiber will paradoxically depolarize and from hypokalemia whereas a WT fiber hyperpolarizes. From a depolarized , the fiber is refractory from sodium channel inactivation and unable to generate an action potential. (Modified from (Cannon, 2018).

Sodium channel mutations may also cause myotonia (see below, 4.3 HyperPP/PMC, and Chapter 3 Inherited Myotonias), and so it is conceivable that HypoPP and myotonia could co-exist in the same patient. In practice, this rarely occurs (if ever) and not in the setting of “classical” HypoPP. First, most cases of HypoPP are caused by missense mutations of CACNA1S, and the CaV1.1 channel has no established role in myotonia. The SCN4A mutations associated with myotonia produce gain-of-function changes, by enhancing voltage-dependent activation (Cummins et al., 1993) or partially disrupting inactivation (Yang et al., 1994; Mitrovic et al., 1995; Cannon et al., 1991). In general, the SCN4A R→X mutations of S4 in HypoPP have mild loss-of-function changes secondary to enhanced inactivation (Struyk et al., 2000; Jurkat-Rott et al., 2000), and as expected are not associated with myotonia. Conversely, the R→X mutations of the S4 segment in the voltage sensor of domain IV in NaV1.4 do not cause a gating pore leak and are not associated with HypoPP; rather these mutations produce gain-of-function changes and PMC (Francis et al., 2011). In one exceptional case, a proband homozygous for R1451L in the S4 of domain IV had frequent and severe attacks of weakness with normal or low [K+] (2.8, 3.3 and 4.0 mmol/L) and latent myotonia by EMG (Luo et al., 2018). Although presented as “HypoPP”, other characteristic features of HypoPP were not described (induction of attacks by carbohydrates or improvement after K supplement). Family members heterozygous for R1451L had mild myotonia and no episodes of weakness. No gating pore current was detected in R1451L expression studies (Luo et al., 2018). In a different family, members heterozygous for R1451L had recurrent episodes of weakness, usually with normal or high [K+], latent myotonia by EMG, a long exercise CMAP test consistent with HyperPP, weakness elicited by oral K+ challenge, and a single episode in which quadriparesis upon wakening was associated with a low [K+] (Poulin et al., 2018). Although described as complex periodic paralysis with features of HyperPP and HypoPP, this case is much more consistent with HyperPP alone. In summary, the data to support “HypoPP with myotonia” is questionable, with atypical HypoPP at best, and more likely HyperPP with a spuriously low [K+]. On the other hand, there is strong evidence that different missense mutations at the same “HypoPP-associated” arginine in an S4 segment may cause either HypoPP with a gating pore current (R222W, R222G) (Bayless-Edwards et al., 2018) or myotonia without HypoPP and a gain-of-function defect for NaV1.4 (R222Q) with a concomitant CLCN1 variant associated with myotonia (Thor et al., 2019). The consensus view that the presence of symptomatic or latent myotonia is an exclusionary criterion for HypoPP should guide clinical practice (Statland et al., 2018; Venance et al., 2006; Fialho et al., 2018).

In a few instances, the gating pore current was either very small in amplitude or not detected for pathogenic HypoPP variants expressed in frog oocytes. Two cases involve charge-conserving missense mutations in S4 segments (arginine to lysine, both positively charged (Kubota et al., 2020)), whereas HypoPP mutations with detectable gating pore currents are all non-conserved substitutions. The R897K variant of CaV1.1 was identified in three HypoPP families (two from France and one from Japan) with ictal hypokalemia and an abnormal decrement in the CMAP exercise test for 2 of 3 studies. No gating pore current was detected in oocytes expressing CaV1.1 R897K. On the other hand, an exceptionally large amplitude gating pore current was observed for a different missense mutation at the same residue (CaV1.1 R897S (Wu et al., 2021)) that is associated with a severe HypoPP phenotype (Chabrier et al., 2008). Functional studies for another charge-conserving substitution, but in NaV1.4 (R219K), had a small-amplitude gating pore current that is predicted to be insufficient to cause aberrant depolarization and paralysis (Kubota et al., 2020). Finally, expression of the non-conserved R900S HypoPP mutation in CaV1.1 did not produce a detectable gating pore current, while another HypoPP mutation at the same residue, R900G, did (Wu et al., 2021). The confidence level was high for a clinical diagnosis of HypoPP for all three of these variants without detectable gating pore currents (CaV1.1 R897S, R900S; and NaV1.4 R219K). Possible explanations are: (1) an alternative defect in channel function creates susceptibility to HypoPP (e.g. for NaV1.4 enhanced slow inactivation (Struyk et al., 2000) or decoupling voltage-sensor movement to channel opening (Mi et al., 2014)), (2) the oocyte expression system is inadequate to demonstrate a gating pore leak that may occur when the channel is expressed in a human muscle fiber.

4.2.3. Investigational approaches for pharmacologic management of episodic weakness (HypoPP)

In principle, a drug or small molecule that blocks the gating pore current, without otherwise altering channel function, should prevent attacks of weakness and facilitate recovery from an established attack. The gating pore is an anomalous ion conduction pathway with no structural homology to the conventional pore of Ca2+ or of Na+ channels (Jiang et al., 2018; Monteleone et al., 2017), and so it is unlikely that pore-blocking drugs could be repurposed to suppress the leak in HypoPP fibers. Many sodium channel toxins act by binding to the voltage-sensor of domain, and are therefore candidates to block the gating pore current. As proof of principle, a toxin from the crab spider (Hm-3) was shown to inhibit the gating pore current of the R222W HypoPP mutation (Mannikko et al., 2018). Unfortunately, the concentration required for 50% inhibition (5 µmol/L) would also severely suppress the Na+ current of HypoPP and WT channels. Nevertheless, the search for gating pore current blockers remains a viable strategy to identify compounds that may improve symptom management in HypoPP.

An increase in the resting conductance of a muscle fiber to K+ will promote hyperpolarization of toward the Nernst potential for K+ . This strategy is highly effective for recovery of twitch force for HypoPP muscle bundles in low K+, when agonists of ATP-sensitive K+ channels (pinacidil or chromakalim) were added to the bath (Grafe et al., 1990; Iaizzo et al., 1995). In clinical practice, KATP channel openers were not useful for management of weakness in HypoPP because symptomatic hypotension occurred before the drug concentration was high enough to improve muscle performance. The large-conductance Ca-activated K+ channel (so-called big K+ or BK channel) is another potential target for increasing the resting muscle permeability to K+, but clinically relevant agonists have not been identified. More recently, activation of KCNQ-type K+ channels by retigabine (1–5 µM) has been shown in a mouse model to protect HypoPP muscle from loss of force in low K+ and also to promote recovery when applied after the loss of force has occurred (Quinonez et al., 2023). In other mouse models, retigabine also reduced myotonia induced by inhibition of the Cl− conductance (Su et al., 2012; Dupont et al., 2019). The KCNQ channel openers retigabine as a first-in-class anti-epileptic drug (Orhan et al., 2012) and a related compound, flupirtine, used in Europe as an analgesic were withdrawn because of adverse events (dose-related CNS effects and liver toxicity, respectively). Nevertheless, the interest in KCNQ channel openers as therapeutic agents remains high and next generation compounds without serious adverse effects are in phase III trials for epilepsy (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT05614063).

Studies in muscle from HypoPP mutant mice have shown that changes in the transmembrane gradient of ions other than K+ will impact the susceptibility to anomalous depolarization of and loss of force (Mi et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2013a). For both normal and HypoPP fibers, the resting conductance of the membrane is dominated by chloride. This means , the equilibrium potential for Cl−, has a major influence on stabilizing . Reduction of the chloride conductance, as occurs in myotonia congenita, impairs this stability and results in bursts of after-discharges and delayed relaxation of force in myotonia (Lipicky and Bryant, 1966; Adrian and Bryant, 1974). During an attack of weakness in HypoPP muscle, where the Cl conductance is normal, the value of must depolarize in order for the modest gating pore leakage current to produce anomalous depolarization of with hypokalemia (Heiny et al., 2019). Depolarization of , in turn, occurs by an increase of intracellular [Cl−]. The Cl− gradient in skeletal muscle is often approximated as “passive”, such that intracellular [Cl−] will shift until . In fact, the [Cl−] is slightly higher than this predicted equilibrium value and so by a few mV (Aickin et al., 1989). Intracellular [Cl−] of muscle is primarily set by the balance of influx via the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter (NKCC1) and efflux at rest via the ClC-1 chloride channel (Gallaher et al., 2009). By recognizing this balance, Geukes Foppen and colleagues (2002) proposed the anomalous depolarization of muscle in low [K+] during an attack of HypoPP may be attenuated by preventing the accumulation of intracellular Cl− via inhibition of the NKCC1 cotransporter. The creation of knock-in mutant mice with a robust HypoPP phenotype (Wu et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2012) provided the opportunity to test this hypothesis. Inhibition of NKCC1 with 1 µmol/L bumetanide completely prevented the loss of force in a 2 mmol/L K+ challenge for HypoPP muscle with the most prevalent CaV1.1 mutation (R528H (Wu et al., 2013a)) and with an NaV1.4 mutation (R669H) where the drug also produced a full recovery of force from an on-going attack (Wu et al., 2013b). Lasix, a less potent inhibitor of NKCC1, also had a similar beneficial effect (Wu et al., 2013a). The clinical application of these powerful loop diuretics for prophylaxis or abortive therapy in HypoPP may be limited by K+ loss in the urine. On the other hand, the hypokalemia resulting from an ictal shift of K+ to the intracellular compartment of muscle in HypoPP is expected to greatly exceed the reduction caused by drug-induced kaliuresis, and so on balance a co-administration of an NKCC1 inhibitor and K+ is worth consideration. While a blinded trial of bumetanide in a single 2 mg oral dose did not completely prevent the CMAP decrement after a 5 min exercise of the ADM; the CMAP recovered rapidly in two subjects who received bumetanide but in none of the placebo controls for this limited study of 10 subjects (Jitpimolmard et al., 2020). No subject experienced weakness after bumetanide. Additional studies are needed to assess the effect of bumetanide on attack frequency and severity in the outpatient setting.

The sarcolemmal pH gradient also impacts the susceptibility to loss of force in HypoPP muscle. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors (e.g. acetazolamide) reduce attack frequency in about 50% of HypoPP patients (Matthews et al., 2011) and while the mechanism of action is still under investigation, the associated metabolic acidosis contributes to the therapeutic benefit (Griggs et al., 1970). This systemic mechanism acting through pH is consistent with studies in mouse models of HypoPP that show protection when acetazolamide is administered in vivo (and causes acidosis), but it is much less effective when applied ex vivo in a tissue bath, where the extracellular pH is fixed (Wu et al., 2013a). Moreover, metabolic acidosis induced by administration of ammonium chloride to HypoPP patients provided protection from provoked attacks of weakness (Jarrell et al., 1976), and a similar benefit of low pH was observed for in vitro studies of muscle from HypoPP mice (Mi et al., 2019). A rapid correction of pH, after a period of acidosis lasting tens of minutes, triggers a robust loss of force in mouse models of HypoPP based on CaV1.1 R528H and NaV1.4 R669H (Mi et al., 2019). Taken together, these data support the notion that acidosis is protective against attacks of HypoPP whereas recovery from acidosis induces a loss of force. This pattern is consistent with the clinical observation that HypoPP patients do not become weak during exercise (possibly because of acidosis), but instead experience an attack several minutes after stopping to rest (with recovery from acidosis). This pH effect may be a consequence of the well-known reduction in the Cl conductance with acidosis, which will promote intracellular Cl accumulation, followed by an anomalous depolarization when the pH and Cl conductance are rapidly returned to baseline in the setting of this elevated intracellular [Cl] (Mi et al., 2019).

4.3. Hyperkalemic periodic paralysis / Paramyotonia congenita

The clinical presentation, natural history, genetic basis, functional defects of mutant channels, and disease management are extensively overlapping for HyperPP and PMC (Cannon, 2018; Ebers et al., 1991; Ptacek et al., 1993). These similarities have led to inconsistencies of genotype-phenotype assignments for SCN4A mutations (e.g. A1156T for either HyperPP or PMC). Moreover, affected individuals with the same mutation in a single family may have clinical manifestations that are more typical for HyperPP or for PMC (McClatchey et al., 1992; de Silva et al., 1990; Kelly et al., 1997). Many neuromuscular specialists view HyperPP and PMC as variations of a single disease, and so the presentation herein is combined for the two disorders. So-called normokalemic periodic paralysis is also a variant of the HyperPP/PMC cluster (Chinnery et al., 2002).

4.3.1. Clinical features and diagnosis (HyperPP/PMC)

The presenting symptom in HyperPP is recurrent episodes of weakness, often in the setting of elevated [K+] of 5 – 6.5 mM (Jurkat-Rott and Lehmann-Horn, 2007; Lehmann-Horn et al., 2004; Fialho et al., 2018). The onset of attacks is usually in childhood and episodes are triggered by cold environments, rest after vigorous exercise, stress, fasting, ingesting of K-rich foods, or alcohol (Charles et al., 2013). Weakness severe enough to impair mobility typical lasts for 30 min to a few hours, although full recovery may not occur for days. Most patients with HyperPP also have myotonia, often becoming symptomatic with activity-dependent muscle stiffness that precedes an attack of weakness or asymptomatic but detectable on clinical exam (e.g. percussion myotonia) or by needle EMG. With advancing age, most patients with HyperPP have a slowly progressive proximal myopathy with permanent weakness that may impair ambulation.

The predominant symptom in PMC is myotonic stiffness that paradoxically worsens with the first few repetitions for voluntary contraction of affected muscles (paramyotonia), whereas the stiffness diminishes with repeated effort (warm-up) for other forms of myotonia (Haass et al., 1981). Stiffness in PMC is also frequently aggravated by muscle cooling so that facial muscles and distal muscles of the hands are often selectively affected in winter. Episodes of weakness with elevated [K+] (> 5.3 mmol/l) may also occur in PMC and are indistinguishable from attacks of HyperPP.

4.3.2. Ion channel mutations and pathophysiology (HyperPP/PMC)

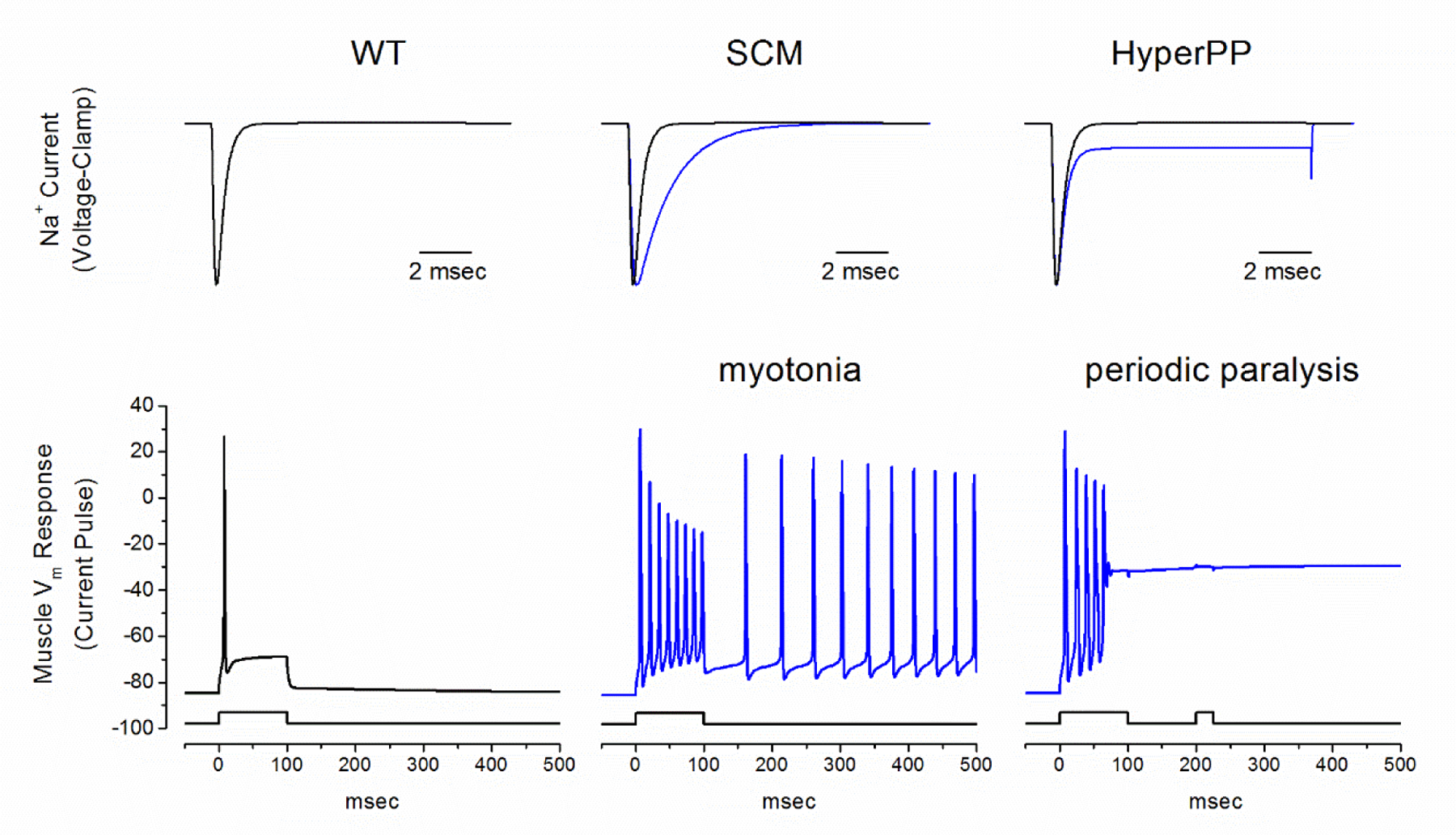

A consistent picture has emerged for the genetic basis and for the types of functional defects in mutant channels that cause HyperPP/PMC (reviewed in Cannon, 2018). Across the narrow clinical spectrum from PMC to HyperPP, and everything in between, the gene defects are missense mutations of SCN4A. No other causative gene has been implicated for HyperPP/PMC. Expression studies show the missense mutations produce gain-of-function alterations in channel behavior, which is consistent with the autosomal dominant inheritance and high penetrance of the clinical phenotype in this disorder. The experimental determination of functional defects for mutant channels, coupled with quantitative simulations of fiber excitability, provide an understanding of how mutation of a single ion channel gene may cause either anomalously enhanced fiber excitability (myotonia) or intermittent failure of excitability (periodic paralysis), of fluctuations of both in the same individual (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Model simulation of myotonia and periodic paralysis resulting from gain-of-function defects in NaV1.4. Top row shows simulated Na+ currents recorded under voltage clamp for WT (black) and mutant NaV1.4 currents (blue) in SCM (middle) and HyperPP/PMC (right). The simulated fiber response to current injection (bottom row) is normally a single action potential with full repolarization after termination of the stimulus (left, for WT). A slower rate of inactivation in SCM mutant channels (middle) enhances excitability and gives rise to a sustained burst of myotonic discharges that persist after termination of the stimulus. On the other hand, the response with a steady-state defect of inactivation in HyperPP mutant channels (right) also begins with a myotonic burst, but then settles to a sustained plateau depolarization. The fiber is refractory at this depolarized state, such that a second current stimulus fails to elicit an action potential (right). Because the mutant NaV1.4 channel has a steady-state gain-of-function defect, the fiber will remain depolarized and inexcitable, resulting in flaccid paralysis. Abbreviations: WT wild type, SCM sodium channel myotonia. (Reproduced from (Cannon, 2018).

The propensity for myotonia or for periodic paralysis segregates with type of functional defect (Cannon, 2015), although there is overlap in the genotype – channel function – phenotype relation. The gain-of-function changes all allow too much Na+ current, either from anomalous enhancement of mutant channel activation (Cummins et al., 1993), from impairment of inactivation (Cannon et al., 1991), or a combination of the two. These defects arise from missense mutations in specific functional domains of the channel protein (Figure 5): the inactivation gate in the III-IV cytoplasmic linker, the receptor for the inactivation gate at the inner mouth of the pore (cytoplasmic ends of S5 and S6 transmembrane segments for each domain), the voltage sensor domain for inactivation (S4 segment in domain IV), or the voltage sensor domains for activation (S1-S4 in domains I-III). These structure-function insights provide additional information for evaluating the interpretation of a variant of unknown significance (VUS) in a gene test for periodic paralysis.

Figure 5.

Structure-function relationship for missense mutations of the skeletal muscle sodium channel, NaV1.4. The HypoPP mutations are all R→X substitutions in S4 transmembrane segments of voltage sensors in domains I – III, which produces the canonical gating pore leakage current. The homologous mutations in domain IV do not produce a gating pore current and instead alter channel inactivation to cause PMC/HyperPP. In general, the PMC/HyperPP mutations are in transmembrane segments of voltage-sensors or of the inner vestibule of the pore (cytoplasmic end of S5 or S6), or in the intracellular III-IV loop that forms the inactivation gate. These regions form the voltage sensors, gates, and receptors for gates that regulate conduction through the pore by activation and inactivation. The mutations associated with CMS are all in the S4 segment of the domain IV voltage sensor, which is tightly coupled to channel inactivation. The CMS mutations all produce loss-of-function changes (enhanced inactivation) for this recessively inherited phenotype. Abbreviations: SCM sodium channel myotonia, PMC paramyotonia congenita, HyperPP hyperkalemic periodic paralysis, HypoPP hypokalemic periodic paralysis, CMS congenital myasthenic syndrome.

Myotonia, without periodic paralysis, occurs with gain-of-function changes that are less severe; either because the change is transient (e.g. slower rate of inactivation, but the inactivation of mutant channels is eventually complete) or the shift in the voltage-dependence of channel gating is small (e.g. 3 to 5 mV hyperpolarized shift for activation of channel opening). These changes enhance fiber excitability and increase the likelihood of self-sustained bursts of after-discharges (Figure 4), as observed for a myotonic run on the needle EMG. The affected fibers are not spontaneously active. Use-dependent accumulation of K+ in the transverse tubules during the preceding voluntary contraction is the depolarizing stimulus that reveals the aberrantly enhanced fiber excitability caused by the NaV1.4 gain-of-function changes. The mechanistic basis for the warm-up phenomenon remains an active area of investigation, with some proposing a role for slow-inactivation of NaV1.4 (Lossin, 2013; Novak et al., 2015), while even less is understood about the basis for paramyotonia.

The transient episodes of weakness in HyperPP/PMC are caused by a failure to maintain the resting potential, with a depolarization-induced loss of fiber excitability from inactivation of NaV1.4. The gain-of-function defects for mutant NaV1.4 channels are the source of the anomalous current that drives depolarization of (Figure 4). These defects are more pronounced than those in sodium channel myotonia without weakness. Moreover, the defects must be manifest in the steady-state behavior, e.g. enhanced activation by a left shift of > 5 mV, because an attack of weakness has a long duration of hours compared to the brief time scale of channel gating and action potentials. Sodium channels undergo multiple forms of inactivation; the conventional fast inactivation on a millisecond time scale that contributes to repolarization of an action potential and slow inactivation over minutes that participates in the use-dependent regulation of sodium channel availability. Gain-of-function defects from a partial disruption of slow inactivation (Hayward et al., 1997; Cummins and Sigworth, 1996) are always associated with susceptibility to attacks of paralysis in HyperPP (e.g. T704M, M1592V) or PMC (e.g. I693T, T1313M).

4.4. Andersen Tawil syndrome

The Andersen Tawil syndrome (ATS) is presented in Chapter 5 of this volume. A brief discussion is presented herein to compare the pathogenic mechanism for the episodes of weakness to the basis for similar attacks in other forms of periodic paralysis.

ATS is unique amongst the familial forms of periodic paralysis because multiple organ systems are affected. The clinical triad in ATS includes periodic paralysis, mild dysmorphic features (small mandible, low set ears, clinodactyly, syndactyly), and ventricular arrhythmias (bigeminy, bidirectional VT) with TU waves on EKG (Tawil et al., 1994; Sansone et al., 1997). The clinical expression is highly variable, even within the same family. In mutation carriers, approximately 60% have periodic paralysis, 80% have dysmorphic features, and over 80% have cardiac manifestations (Tristani-Firouzi et al., 2002; Mazzanti et al., 2020; Kimura et al., 2012). Episodes of weakness in ATS are often similar to those in HypoPP (low serum K, similar trigger factors, no myotonia) (Sansone et al., 1997), but weakness with elevated serum K+ has been observed as well (Tawil et al., 1994). This inconsistency has led to the term dyskalemic periodic paralysis in ATS. Also similar to other forms of periodic paralysis, the CMAP exercise test shows an abnormal decremental response (Song et al., 2016b; Katz et al., 1999) and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may be beneficial (Junker et al., 2002; Gupta et al., 2021).

The majority of patients with ATS have dominant-negative loss-of-function mutations of KCNJ2, encoding the Kir2.1 inward rectifying K+ channel (Plaster et al., 2001; Tristani-Firouzi et al., 2002), although in one cohort of 17 probands only 40% had mutations of KCNJ2 (Donaldson et al., 2003). A second disease gene, KCNJ5, is rare cause of ATS in which missense mutation of a G-protein coupled inward rectifying K+ channel (Kir3.4) also exerts a dominant-negative effect on the Kir2.1 current (Kokunai et al., 2014).

The impairment of fiber excitability demonstrated by the CMAP exercise test is consistent with the notion that episodes of weakness in ATS are caused by sustained, anomalous depolarization of (although this has yet to be directly shown by intracellular recordings). The resting potential is determined by a balance of inward and outward currents, and is the condition for which the total ionic current is zero. Normally, the Kir2.1 channel is the major contributor to the resting outward K+ current, and so a loss of Kir2.1 is predicted to promote depolarization of . Moreover, the propensity for inappropriate depolarization is expected to be worse with hypokalemia, in a manner analogous to the deleterious effect of the gating pore leak (Figure 3). The reduction of Kir2.1 is numerically equivalent to an anomalously increased inward current from the gating pore leak; operationally “two sides of the same coin”. In support of this hypothesis, pharmacological models of ATS (Ba2+ block of Kir2.1) and computer simulation both show anomalous depolarization and loss of force in low K+ (Struyk and Cannon, 2008). Unexpectedly, a high K+ challenge also elicited aberrant depolarization of and loss of force (Elia and Cannon, unpublished observations). These preliminary studies offer insights on the conflicting case reports of hypokalemic or hyperkalemic associated episodes of weakness in ATS.

4.5. Thyrotoxic periodic paralysis

4.5.1. Clinical features and diagnosis (TPP)

TPP presents with episodes of weakness similar to those in HypoPP, including ictal hypokalemia and similar trigger factors, but in the setting of hyperthyroidism (Ober, 1992; Maciel et al., 2011). Susceptible individuals may have an attack of weakness in the absence of clinically overt thyrotoxicosis (McFadzean and Yeung, 1967), but the serologic test of thyroid function will consistently show hyperthyroidism. Myotonia does not occur in TTP. The CMAP exercise test shows a late decline of amplitude, similar to the loss of fiber excitability found in all forms of periodic paralysis (Arimura et al., 2007). After treatment when the patient is euthyroid, the episodes of weakness cease and the CMAP exercise test no long shows an abnormal decrement (Jackson and Barohn, 1992).

The prevalence of TTP is much higher in Asia (China, Japan, Korea) and Latin America than in North America or Europe (Ober, 1992; Chen et al., 1965). Approximately 1 in 50 Asians with hyperthyroidism will have TTP, while in other parts of the world the risk is about 1 in 500 or 1000. The male predominance is even more striking in TTP, with a relative risk of 50:1 (male : female).

4.5.2. Ion channel mutations (TPP)

The geographical differences in prevalence of TPP, and the rare occurrence of familial clusters (Kufs et al., 1989), suggest a genetic influence on the risk for episodic weakness in hyperthyroidism. A screen of candidate ion channel genes with a thyroid hormone response element (TRE) and expressed in skeletal muscle led to the identification of a new gene, KCNJ18, highly homologous to the Kir2.2 inward rectifying K+ channel and was named Kir2.6 (Ryan et al., 2010). Variants of KCNJ18 have been associated with TTP (Ryan et al., 2010) and with sporadic periodic paralysis (SPP) in which episodic weakness occurs without thyrotoxicosis (Cheng et al., 2011). In the original cohort of 30 TTP patients from North America and Europe, 1/3rd had variants in KCNJ18 (Ryan et al., 2010). Subsequent studies in a Chinese cohort of 122 TPP patients found only 3.1% had pathogenic variants of KCNJ18 (Li et al., 2015), and another group has questioned whether KCNJ18 is a disease gene for TPP (Kuhn et al., 2016).

Expression studies have revealed loss-of-function changes for several pathogenic variants of KCNJ18, but not for all (Cheng et al., 2011; Ryan et al., 2010; Zheng et al., 2016). Expression of Kir2.6 at the plasma membrane is poor, and immunocytochemical studies show most of the protein is retained in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). Moreover, Kir2.6 co-assembles with Kir2.1 and Kir2.2, and thereby may regulate the trafficking of Kir2.x channels to the plasma membrane by retention in the ER (Dassau et al., 2011). These observations have led to the notion that in thyrotoxicosis expression of KCNJ18 is increased, more Kir2.x subunits are retained in the ER, and the net result is a decrease of the membrane K+ conductance. Similar to the pathomechanism of ATS, a reduced K+ conductance in TTP is predicted to cause attacks of weakness from hypokalemia and paradoxical depolarization of .

Increasing evidence has emerged for additional genetic defects in TTP, and that TTP and SPP may share a common genetic etiology. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified a single nucleotide variant (SNV; rs23011) that confers risk for TTP (Jongjaroenprasert et al., 2012) and in other studies showed association with TTP and SPP (Chu et al., 2012; Nakaza et al., 2020). Curiously, rs23011 is 75 kb downstream from KCNJ2, the disease gene for ATS on 17q24.3, which is very remote from KCNJ18 on 17p11.2. In this same region, a risk allele for both TTP and SPP was identified in a lincRNA that disrupted the ability to regulate Kcnj2 expression in a mouse muscle cell line (Song et al., 2016a).

4.6. Rare variants of atypical periodic paralysis

Advances in the accessibility of genetic testing has led to the identification of pathologic variants in genes coding for ion channels or pumps for which the clinical phenotype includes recurrent episodes of weakness that are not typical for periodic paralysis (Fialho et al., 2018). The unusual features may include late onset, lack of usual triggers (diet, K+, temperature), prominent pain, congenital myopathy, or rapid fatiguability with or without a decremental response from repetitive stimulation.

4.6.1. Myopathy and myasthenic syndromes with recessive SCN4A variants

A syndrome with features of congenital myasthenia (fatigable generalized weakness, ptosis) and congenital myopathy that later in life evolves to include prolonged episodes of weakness has been reported for several probands (Tsujino et al., 2003; Elia et al., 2019), often in families with consanguinity (Arnold et al., 2015; Habbout et al., 2016; Echaniz-Laguna et al., 2020). Mutations of genes associated with the congenital myasthenic syndrome (acetylcholine receptor, cholinesterase, rapsyn, or choline acetyl transferase) were excluded. The CMAP did not have a post-exercise decrement, as occurs in periodic paralysis. In some cases a pronounced decrement was observed with high-frequency repetitive nerve stimulation at 10 or 50 Hz, implicating a defect of the neuromuscular junction, and yet the end plate potential was of normal amplitude (Tsujino et al., 2003). This observation led to a consideration of a sodium channel defect that impaired the generation of a propagated action potential in muscle.

A recessive pattern of pathogenic variants in SCN4A, either homozygous mutations in families with consanguinity or compound heterozygous mutations in others, was identified in probands (Figures 5 and 6). The heterozygous parents were asymptomatic carriers. Notably, almost all of the missense variants are located in the voltage-sensor of domain IV, as shown in Figure 5 (Tsujino et al., 2003; Habbout et al., 2016; Arnold et al., 2015), with the one exception being in the carboxyl terminus (Echaniz-Laguna et al., 2020). Functional expression studies for these pathogenic variants of SCN4A all show loss-of-function changes, usually from a marked enhancement of inactivation (e.g. 15–30 mV left shift (Tsujino et al., 2003), which is larger than for voltage-dependent defects observed in any other skeletal muscle channelopathy). This pattern is consistent with the prevailing view for structure-function relations of NaV channels in which the voltage sensor of domain IV is tightly coupled to channel inactivation (Capes et al., 2013), whereas domains I-III are coupled to activation.

Figure 6.

Summary of the phenotypes, diseases, and class of channel defect for the NaV1.4 channelopathies of skeletal muscle. In general, GOF changes cause dominantly inherited phenotypes whereas the LOF changes are associated with recessive inheritance. Abbreviations: GOF gain-of-function, LOF loss-of-function, S4 fourth transmembrane segment of a voltage sensor domain, R→X missense substitution from arginine (R) to some other amino acid (X). (Modified from (Cannon, 2018).

Pathogenic variants of SCN4A have also been associated with congenital myopathy (Figure 6). The congenital myopathies are a clinically and genetically diverse group of disorders, often with characteristic structural changes in muscle biopsies. In a consortium effort, whole exome sequencing led to the identification variants of SCN4A in 11 patients from six unrelated families with diverse clinical phenotypes ranging from in utero demise to severe fetal hypokinesia to congenital myopathy and survival to adulthood (Zaharieva et al., 2016). Inheritance was recessive, with homozygous mutations in consanguineous families and compound heterozygous mutations in others. Functional studies of missense mutant channels generally showed severe loss of function defects, although the behavior of one variant (H1782Qfs65) was indistinguishable from wild type when expressed in fibroblasts (Zaharieva et al., 2016). The parents were asymptomatic carriers, even with null mutations that are predicted to destroy the coding potential of SCN4A. Consistent with this observation, heterozygous mice with a knockout of scn4a do not have myopathy or susceptibility to periodic paralysis (Wu et al., 2016).

Subsequently, additional probands have been identified with recessive SCN4A mutations in congenital myopathy (Gonorazky et al., 2017; Mercier et al., 2017). In all cases, the muscle histology had nonspecific findings, with no unique markers to implicate a potential SCN4A defect. The variability in the clinical phenotype correlated with the genetic defect. Homozygous null mutations of SCN4A are lethal in utero, showing that the embryonically expressed cardiac isoform (NaV1.5 encoded by SCN5A) is not capable of rescuing the phenotype. Compound heterozygotes with a functional null allele plus a hypomorphic loss-of-function mutation results in a severe phenotype with fetal hypokinesia. Less severe loss-of-function mutations, as homozygous alleles or compound heterozygotes, produce a spectrum of clinical phenotypes ranging from moderate congenital myopathy to a myasthenic syndrome. Finally, when at least one SCN4A allele is wild type then the individual has no signs of muscle disease.

4.6.2. Ryanodine receptor-associated atypical periodic paralysis

The skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor, encoded by RYR1, is the Ca2+ release channel of the sarcoplasmic reticulum. Mutations of RYR1 give rise to a diverse group of myopathies (reviewed in Dowling et al., 2014) including susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia and several types of congenital myopathy (central core disease, mutliminicore myopathy, centronuclear myopathy, congenital fiber type disproportion, and core-rod myopathy). In rare instances, a clinical presentation that begins as a static congenital RYR1-myopathy later evolves to include discrete episodes of severe weakness with cramping and myalgia (Zhou et al., 2010). The attacks of weakness differed from those in periodic paralysis because the onset was later (early adulthood), dietary triggers were not recognized, and pain was a prominent feature. Like periodic paralysis, however, attacks were induced by exercise and the CMAP exercise test showed an abnormal decrement. In total, four probands with RYR1-associated atypical periodic paralysis have been described in the literature (Matthews et al., 2018), two with and two without congenital myopathy. Three of the four had compound heterozygous missense and nonsense mutations of RYR1, whereas mutations of SCN4A, CACNA1S, and KCNJ2 were excluded.

The pathomechanism by which RYR1 mutations cause susceptibility to atypical periodic paralysis remains to be established. The abnormal CMAP exercise test implies an exercise-induced defect in sarcolemmal excitability (Matthews et al., 2018). While the RyR1 protein exerts “retrograde” feedback that enhances the Ca2+ current conducted by the CaV1.1 L-type channel in skeletal muscle (Nakai et al., 1996), this current does not have established role in the regulation of , and so a connection to depolarization-induced paralysis remains to be elucidated.

The ryanodine receptor is a large protein of about 5000 amino acids (i.e. 2.5 times larger than NaV1.4 or CaV1.1) and the structure-function relationships are not as well resolved as compared to voltage-gated cation channels. Consequently, the interpretation of an RYR1 variant of unknown significance can be problematic in the evaluation of clinically diagnosed periodic paralysis when no pathogenic variant is identified in SCN4A, CACNA1S, or KCNJ2. The presence of myalgia, late onset, abnormal CMAP exercise test, and compound heterozygous variants in RYR1 may add confidence to assigning a pathogenic status.

4.6.3. Na/K-ATPase associated periodic paralysis plus seizures

A de novo missense mutation (S779N) in the α2 subunit of the Na/K-ATPase (encoded by ATP1A2) was identified in a proband with HypoPP-like episodes beginning in childhood (Sampedro Castaneda et al., 2018). Episodes often occurred upon waking and lasted for hours, with a low K+ (2.4 mmol/L) documented on one attack. Trigger factors included ingestion of carbohydrates or viral infection, and symptoms improved with K+ supplementation. No mutations were identified in SCN4A, CACNA1S or KCNJ2. The proband also had seizures from age 4 months that were difficult to control, and a brain MRI at 7 years of age showed mesial temporal sclerosis. Mutations of ATP1A2 have previously been associated with hemiplegic migraine (Bottger et al., 2012) and alternating hemiplegia of childhood (Bassi et al., 2004), but the proband did not have symptoms consistent with either of these disorders.

Expression studies of S779N in frog oocytes showed a reduced turnover of Na/K-ATPase pump activity, but more importantly also revealed a leakage current that was permeable to Na+ and H+ (Sampedro Castaneda et al., 2018). Missense mutations of ATP1A2 associated with hemiplegic migraine also decrease Na/K-ATPase turnover, but a leakage current has not been reported in these studies, nor do these patients have a skeletal muscle phenotype. These observations imply the leakage current for S779N is the critical defect that creates susceptibility to HypoPP-like episodes of weakness, by a mechanism similar to the gating pore leakage current for mutant NaV1.4 and CaV1.1 in conventional HypoPP.

4.7. Conclusions

The molecular basis and pathomechanism for the classic forms of periodic paralysis are now well established (Cannon, 2015; Lehmann-Horn et al., 2004). Episodic weakness in HypoPP is caused by “leaky” Ca2+ or Na+ channels, with an anomalous gating pore current that is conducted through the voltage-sensor domain of the channel. The leak is active at the resting potential, which renders the fiber susceptible to paradoxical depolarization and loss of excitability in low K+. Myotonia and transient weakness in HyperPP / PMC are both caused by gain-of-function defects (impaired inactivation or augmented activation) of mutant Na+ channels. Hyperkalemia produces a modest depolarization, as occurs in normal fibers, that becomes pathologically amplified by the excessive inward current conducted by mutant Na+ channels and leads to refractory loss of fiber excitability. For both HypoPP and HyperPP, the depolarization-induced loss of fiber excitability is a consequence of altered function for mutant channels, either leaky or gain of function. This pathomechanism implies the genetic defects will be missense mutations or small deletions of one or two codons that preserve the reading frame. Moreover, the HypoPP mutations will largely be confined to missense substitutions of arginine residues in first- or second-most outer position in S4 transmembrane segments (Matthews et al., 2009; Sternberg et al., 2001). Genetic variants of introns or regulatory elements will not produce alterations of channel function that cause susceptibility to HypoPP or to HyperPP / PMC. Likewise, null mutations of SCN4A or CACNA1S do not cause periodic paralysis, and individuals with a single intact copy of these genes have no muscle signs or symptoms (Zaharieva et al., 2016; Schartner et al., 2017). These insights aid in the interpretation of variants of unknown significance that are detected in genetic screens for periodic paralysis.

In contrast, the pathomechanism in ATS is based on a reduction of the inward rectifying K+ current (Plaster et al., 2001). The consensus view is that dominant inheritance for ATS is caused by loss-of-function for the channel tetrameric complex by dominant-negative effects of the mutant subunit, often by impaired trafficking to the plasma membrane or loss of PIP2-activation (Tristani-Firouzi and Etheridge, 2010). The diversity of genetic lesions producing a loss of function is greater than the set focal mutations that result in a gain of function change. This may account for the lower percentage of clinically diagnosed ATS patients with an identified mutation (about 60%, almost always in KCNJ2) compared to greater likelihood of identifying a mutation of CACNA1S or SCN4A (70%) for a clinical diagnosis of “typical” HypoPP and HyperPP/PMC (Fialho et al., 2018; Statland et al., 2018).

Advances in understanding the functional defects that produce susceptibility to recurrent attacks of weakness in periodic paralysis are expanding the therapeutic strategies being investigated to improve management of symptoms. Anomalous depolarization of is the final common pathway, and interventions to stabilize a normal polarization of the fiber show promise in preclinical studies. With this more generalized approach, the molecular target is not the mutant channel (e.g. K+ channel openers (Quinonez et al., 2023) or inhibitors of Cl− influx by NKCC1 (Wu et al., 2013a)). Other pharmacologic strategies are directed at reducing the aberrant current conducted by a mutant channel (e.g. inhibition of the gating pore leak (Mannikko et al., 2018) or Na+ channel pore-blockers). While new pharmacologic approaches show great promise to improve quality of life by reducing the frequency, duration, and severity of episodic weakness in periodic paralysis, a more durable and comprehensive correction of the defect, as can be achieved with gene therapy, offers the possibility of also having an impact on reducing the risk of late onset permanent weakness.

Acknowledgements

The author’s research program on channelopathies of skeletal muscle is supported by the National Institute of Arthritis, Skin, and Musculoskeletal Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (AR063182 and AR078198).

References

- Adrian RH & Bryant SH (1974). On the repetitive discharge in myotonic muscle fibres. Journal of Physiology 240: 505–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aickin CC, Betz WJ & Harris GL (1989). Intracellular chloride and the mechanism for its accumulation in rat lumbrical muscle. J Physiol 411: 437–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura K, Arimura Y, Ng AR, et al. (2007). Muscle membrane excitability after exercise in thyrotoxic periodic paralysis and thyrotoxicosis without periodic paralysis. Muscle & nerve 36: 784–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold WD, Feldman DH, Ramirez S, et al. (2015). Defective fast inactivation recovery of Nav 1.4 in congenital myasthenic syndrome. Ann Neurol 77: 840–850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi MT, Bresolin N, Tonelli A, et al. (2004). A novel mutation in the ATP1A2 gene causes alternating hemiplegia of childhood. J Med Genet 41: 621–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayless-Edwards L, Winston V, Lehmann-Horn F, et al. (2018). NaV1.4 DI-S4 periodic paralysis mutation R222W enhances inactivation and promotes leak current to attenuate action potentials and depolarize muscle fibers. Sci Rep 8: 10372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biemond A & Daniels AP (1934). Familial periodic paralysis and its transition into spinal muscular atrophy. Brain 57: 91–108. [Google Scholar]

- Bottger P, Doganli C & Lykke-Hartmann K (2012). Migraine- and dystonia-related disease-mutations of Na+/K+-ATPases: relevance of behavioral studies in mice to disease symptoms and neurological manifestations in humans. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 36: 855–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulman DE, Scoggan KA, van Oene MD, et al. (1999). A novel sodium channel mutation in a family with hypokalemic periodic paralysis. Neurology 53: 1932–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC (2010). Voltage-sensor mutations in channelopathies of skeletal muscle. J Physiol 588: 1887–1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC (2015). Channelopathies of skeletal muscle excitability. Compr Physiol 5: 761–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC (2018). Sodium Channelopathies of Skeletal Muscle. Handb Exp Pharmacol 246: 309–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon SC, Brown RH Jr. & Corey DP (1991). A sodium channel defect in hyperkalemic periodic paralysis: potassium-induced failure of inactivation. Neuron 6: 619–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capes DL, Goldschen-Ohm MP, Arcisio-Miranda M, et al. (2013). Domain IV voltage-sensor movement is both sufficient and rate limiting for fast inactivation in sodium channels. J Gen Physiol 142: 101–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabrier S, Monnier N & Lunardi J (2008). Early onset of hypokalaemic periodic paralysis caused by a novel mutation of the CACNA1S gene. J Med Genet 45: 686–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charles G, Zheng C, Lehmann-Horn F, et al. (2013). Characterization of hyperkalemic periodic paralysis: a survey of genetically diagnosed individuals. J Neurol 260: 2606–2613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KM, Hung TP & Lin TY (1965). PERIODIC PARALYSIS IN TAIWAN. CLINICAL STUDY OF 28 CASES. Archives of neurology 12: 165–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CJ, Lin SH, Lo YF, et al. (2011). Identification and Functional Characterization of Kir2.6 Mutations Associated with Non-familial Hypokalemic Periodic Paralysis. J Biol Chem 286: 27425–27435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnery PF, Walls TJ, Hanna MG, et al. (2002). Normokalemic periodic paralysis revisited: does it exist? Ann Neurol 52: 251–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu PY, Cheng CJ, Tseng MH, et al. (2012). Genetic variant rs623011 (17q24.3) associates with non-familial thyrotoxic and sporadic hypokalemic paralysis. Clin Chim Acta 414: 105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creutzfeldt OD, Abbott PC, Fowler WM, et al. (1963). Muscle membrane potentials in episodica adynamia. Electroenceph. Clin. Neurophysiol 15: 508–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR & Sigworth FJ (1996). Impaired slow inactivation in mutant sodium channels. Biophysical Journal 71: 227–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins TR, Zhou J, Sigworth FJ, et al. (1993). Functional consequences of a Na+ channel mutation causing hyperkalemic periodic paralysis. Neuron 10: 667–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dassau L, Conti LR, Radeke CM, et al. (2011). Kir2.6 Regulates the Surface Expression of Kir2.x Inward Rectifier Potassium Channels. J Biol Chem 286: 9526–9541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Silva SM, Kuncl RW, Griffin JW, et al. (1990). Paramyotonia congenita or hyperkalemic periodic paralysis? Clinical and electrophysiological features of each entity in one family. Muscle Nerve 13: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson MR, Jensen JL, Tristani-Firouzi M, et al. (2003). PIP2 binding residues of Kir2.1 are common targets of mutations causing Andersen syndrome. Neurology 60: 1811–1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]