Abstract

Purpose

Sorafenib has demonstrated anti-tumor efficacy and radiosensitizing activity preclinically and in breast cancer. We examined sorafenib in combination with whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) and explored the [18F] 3′deoxy-3′-fluorothymidine (FLT)-PET as a novel brain imaging modality in breast cancer brain metastases.

Methods

A phase I trial of WBRT + sorafenib was conducted using a 3 + 3 design with safety-expansion cohort. Sorafenib was given daily at the start of WBRT for 21 days. The primary endpoints were to determine a maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and to evaluate safety and toxicity. The secondary endpoint was CNS progression-free survival (CNS-PFS). MacDonald Criteria were used for response assessment with a correlative serial FLT-PET imaging study.

Results

13 pts were evaluable for dose-limiting toxicity (DLT). DLTs were grade 4 increased lipase at 200 mg (n = 1) and grade 3 rash at 400 mg (n = 3). The MTD was 200 mg. The overall response rate was 71%. Median CNS-PFS was 12.8 months (95%CI: 6.7-NR). A total of 15 pts (10 WBRT + sorafenib and 5 WBRT) were enrolled in the FLT-PET study: baseline (n = 15), 7–10 days post WBRT (FU1, n = 14), and an additional 12 week (n = 9). A decline in average SUVmax of ≥ 25% was seen in 9/10 (90%) of WBRT + sorafenib patients and 2/4 (50%) of WBRT only patients.

Conclusions

Concurrent WBRT and sorafenib appear safe at 200 mg daily dose with clinical activity. CNS response was favorable compared to historical controls. This combination should be considered for further efficacy evaluation. FLT-PET may be useful as an early response imaging tool for brain metastases.

Keywords: Brain metastasis, Breast cancer, Sorafenib, Whole brain radiotherapy, FLT-PET

Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is one of the most common solid tumors to metastasize to the brain [1–3]. While stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) has become increasingly popular, whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) remains an important treatment option, with memantine now commonly used to decrease the potential for neurocognitive toxicity [4–8]. The addition of a radiosensitizer has been proposed to improve the efficacy of WBRT but has been less than optimal [9, 10].

Combining a VEGF-targeting agent has been proposed as a rational approach to enhance radiotherapy and is supported by preclinical data [11–13]. Sorafenib is an oral tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) with anti-VEGF activity that has been studied in metastatic BC with moderate activity and is a radiosensitizer [12, 14–22]. We conducted a phase I trial of sorafenib with WBRT in BC patients with brain metastases (BCBM) and examined the safety and toxicities. As a secondary endpoint, we evaluated central nervous system-progression-free survival (CNS-PFS) using MacDonald criteria to assess preliminary clinical activity for BCBM.

Accurate response assessment post radiotherapy has been an emerging clinical challenge and an active area of research given that contrast enhancement on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be affected by changes in the brain vasculature [23, 24]. While MRI provides anatomic information following radiotherapy, imaging that provides biologic functional information may be more informative prognostically. The use of bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF drug, used in brain tumors has been reported to potentially impact the accuracy of response assessment through altering the brain vasculature [25, 26]. The Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology (RANO) working group has noted that the use of anti-VEGF agents may confound the response assessment using the Macdonald Criteria in particular [26].

Positron emission tomography (PET) is proposed to supplement MRI in brain metastases response assessment by characterizing cellular physiology [27]. Many studies have evaluated amino acids as a PET tracer, but there is a paucity of data regarding the use of other PET tracers in brain metastases [27]. [18F] 3′deoxy-3′-fluorothymidine (FLT) is a thymidine analog that tracks the salvage pathway of DNA synthesis. FLT uptake correlates with thymidine uptake and thymidine kinase activity. Thus, it has been considered to reflect cell proliferation and proposed as a non-invasive measurement of cell proliferation [28–30]. A study conducted among patients undergoing chemotherapy for BCBM explored the use of FLT and reported that this novel tracer may supplement information obtained from MRI [31]. Additional evidence for its use in patients with BCBM or those undergoing brain RT would be helpful to assess its potential as a response assessment tool, potentially informing subsequent CNS monitoring strategies and/or a future need for sterotactic radiation (SRS). Therefore, we explored FLT-PET as a complementary imaging tool for sorafenib and WBRT as a correlative study conducted in parallel to this phase I trial.

Material and methods

A prospective phase I dose-escalation study in BCBM using a 3 + 3 design (NCT01724606) was conducted after appropriate approval was obtained from the institutional review board. Informed written consent was obtained from each subject. The primary objective of the study was to assess the toxicity and determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of sorafenib with WBRT. A secondary objective was to describe clinical efficacy by measuring central nervous system-progression-free survival (CNS-PFS), defined as the interval between the date of study entry and the date of tumor progression in the brain or death from any cause. Concurrently, we conducted an imaging correlative study (NCT01621906) to examine the radiologic response to WBRT with and without sorafenib therapy using serial FLT-PET and MRI imaging modalities in patients with BCBM.

The study included patients with histologically confirmed BC and new or progressive brain metastases (BM) (≥ 10 mm in longest dimension) by MRI of the brain. Patients were required to have planned WBRT based on number or size as assessed by the treating investigator. The protocol specified WBRT (1 fraction /day × 10 fractions) to be administered. No patient received hippocampal avoidance. Patients with leptomeningeal metastases were allowed if confined to the WBRT field only (additional MRI spine was required to demonstrate no other area of involvement within 4 weeks of enrollment). Other key eligibility criteria included Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) ≥ 70, a non-escalating dose of steroid (not exceeding more than 16 mg daily of oral dexamethasone) for ≥ 5 days, and no prior exposure to an anti-VEGF agent except bevacizumab. Patients must have had adequate organ function.

Prior CNS-targeted therapies such as SRS and surgery were allowed provided that there were new, non-irradiated measurable brain lesions. There was no limit to prior therapies with the last anti-cancer treatment ≥ 2 weeks from initiation of WBRT except for hormonal therapy, which was required to be discontinued but without a washout period. If patients had human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positive BC and were being treated with anti-HER2 antibodies at the time of new or progressive BM diagnosis, anti-HER2 antibody therapy was allowed to continue during the protocol therapy.

The study planned for three dose levels of sorafenib dosed once daily at 200 mg, 400 mg, and 600 mg. No intra-patient dose escalation was allowed. Sorafenib was administered orally and daily at the start of WBRT and continued for a total of 21 days. WBRT was given in 10 fractions with 3 Gy/fraction as specified by the protocol. The study schema is available in Online Resource 1. A pre-planned safety-expansion cohort of six additional patients was treated with sorafenib at the MTD with WBRT.

Toxicity assessments were conducted weekly for 4 weeks, and the dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) was defined during the WBRT and 2 weeks after WBRT. Toxicity was graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) version 4.0. Patients continued treatment until progression of the disease, unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal from the study.

DLT was defined as the following toxicities attributable to the study drug: any grade ≥ 3 non-hematologic toxicity (except alopecia, altered taste, nail changes), and any grade 3 nausea, vomiting, or dehydration (except those occurred in setting of inadequate compliance with supportive care measures lasting for less than 72 h), grade 3 diarrhea not responsive to supportive care measures within 72 h, grade ≥ 3 hand-foot skin reaction, grade ≥ 2 symptomatic/persistent drug-related hypertension, grade 3 lipase elevation only in the presence of clinical signs or symptoms of pancreatitis, or grade 4 lipase elevation with or without signs or symptoms of pancreatitis, grade ≥ 3 serum bilirubin, hepatic transaminases (> 2 weeks except for patients with liver or bone metastases with asymptomatic hepatic transaminase elevations related to the disease under the study ≥ 10 times upper limit of normal were considered as DLT), grade ≥ 4 neutropenia lasting ≥ 4 days in duration or with fever, grade ≥ 4 thrombocytopenia, ≥ 7 days, < 10,000 for one day, or any value below or equal to 50,000 associated with bleeding, and grade 4 anemia. Any unresolved drug-related toxicity requiring drug interruption for > 14 days was also considered as DLT.

Radiologic assessments

All patients were required to undergo baseline radiologic assessment with MRI brain with contrast. Subsequent MRI brain imaging was performed at 10–12 weeks after WBRT and then every 3 months for the first year and subsequently every 6 months until CNS progression or death. Patients were evaluated for CNS response using standard MacDonald criteria.

The FLT-PET study was conducted concurrently with a planned sample size of ten patients in each of two independent cohorts (n = 20). The first cohort consisted of the first ten patients who participated in phase I sorafenib with WBRT study, and the second cohort included consenting patients who underwent clinically indicated standard WBRT (off-protocol) for new or progressive BM.

All patients in the FLT-PET study were required to undergo baseline radiologic assessment with contrast-enhanced brain MRI and brain FLT-PET scan (Suppl Fig. 1). Brain FLT-PET was repeated at 7–10 days after WBRT to evaluate early changes. Subsequent MRI and FLT-PET scans were performed at 10–12 weeks after the completion of WBRT. For MRI, CNS response was assessed using standard MacDonald criteria.

FLT-PET imaging

Dynamic PET scans were performed for a total of 60-min over a single field of view (15.7 cm axially) on the Discovery STE, 690 or 710 PET/CT (GE Health Care, Inc.), concurrently with an intravenous infusion of 333 ± 35 MBq of 18F-FLT. Where applicable, the second and third dynamic 18F-FLT-PET/CT were performed on the same scanner as the first PET/CT. Images were acquired in list mode and binned into 4 × 15-s, 4 × 30-s, 7 × 60-s, and 10 × 300-s. Low-dose CT scan was used for attenuation correction and anatomical localization. PET emission data were acquired in 3-dimensional mode, corrected for attenuation, scatter, and random events, and iteratively reconstructed into a 128 × 128 × 47 matrix (voxel dimensions: 2.34 × 2.34 × 3.27 mm3) using the ordered subset expectation maximization algorithm provided by the manufacturer.

Image analysis

Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn over sites of disease identified by a radiologist with experience in nuclear medicine (H.S.) to derive standardized uptake values corrected by body weight (SUV). The analysis was also performed for normal brain tissue by averaging the results from 10 spherical ROIs, each with a 10-mm radius.

Statistical analysis

MTD was determined using a standard 3 + 3 dose-escalation design without intra-patient dose escalation. Once the MTD was determined, six additional patients were enrolled in a safety-expansion phase and treated with sorafenib at MTD with WBRT. If a patient had any dose of study drug, that patient was included in the study analysis, including toxicity and DLT assessments.

In secondary analyses, CNS-PFS was estimated using Kaplan–Meier methods. PFS was defined as the interval between the date of study entry and the date of tumor progression in the brain or death from any cause. Patients without progression or death were censored at the time of the last follow up. Patients were considered evaluable for response if follow up MRI brain imaging was completed. Descriptive statistics were used for radiographic responses using two imaging modalities, FLT-PET and MRI.

Results

19 patients were enrolled on the phase I trial portion, with 13 patients treated in the dose-escalation phase and evaluable for toxicities. Six additional patients were treated in the safety-expansion cohort at the MTD. Of the 19 patients in the phase I trial, ten patients participated in the FLT-PET correlative imaging study, and five additional patients who were treated with WBRT alone were additionally enrolled in the FLT-PET imaging correlative study. Due to slow accrual, the WBRT only cohort in the FLT-PET imaging study was closed prior to reaching the enrollment goal of ten patients.

The clinical characteristics of all 24 patients (from the Phase I and FLT-PET study) are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 52 years old (range 37–77). The HER2 positive subtype was the most common (42%; 10/24). The majority of patients (71%; 17/24) had no prior local therapy for BM. 67% (16/24) of patients were on a corticosteroid. Of the ten HER2 positive patients, 40% of patients continued anti-HER2 antibody(ies).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 24)

| Number (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Median (range) in years | 52 (37–77) |

| Sex | Female | 22 (92%) |

| Male | 2 (8%) | |

| ER/PR/HER2 status | ER + HER2- | 9 (37%) |

| HER2 + | 10 (42%) | |

| ER/PR/HER2 negative | 5 (21%) | |

| Prior brain metastases tx | None | 17 (71%) |

| Radiation | 4 (17%) | |

| Surgery | 3 (13%) | |

| KPS | 100% | 2_(8%) |

| 80–90% | 20 (83%) | |

| < 80% | 2 (8%) | |

| Sites of non-CNS disease | None (CNS only) | 3 (13%) |

| Liver | 10 (42%) | |

| Lung | 12 (50%) | |

| Bone | 12 50%) | |

| Baseline steroid use | Yes (dexamethasone) | 16 (67%) |

| No | 8 (33%) | |

| Concurrent therapy with anti-HER2 drugs | Yes (trastuzumab, pertuzumab) | 4 (40% of HER2 +) |

| No | 6 (60% of HER2 +) |

Include both patients who were enrolled on WBRT and sorafenib Phase I trial and WBRT only FLT-PET study

The MTD was determined to be 200 mg per day with WBRT. DLTs were grade 4 lipase elevation at 200 mg (1 patient) and grade 3 rash at 400 mg (3 patients). 6 additional patients were treated in the safety-expansion cohort at MTD without additional or new toxicities considered as DLTs. As expected, since rash is a known toxicity associated with sorafenib, rash was observed predominantly but not exclusively in the WBRT field. The summary of treatment-emergent toxicities (regardless of attribution) from phase I as well WBRT only (from the FLT-PET study) is presented in Table 2. In total,14 patients received the 200 mg dose.

Table 2.

Treatment emergent toxicites (regardless of attribution)

| Adverse Events (> 20%) | 200 mg dose (N = 14) |

400 mg dose (N = 5) |

WBRT only FLT-PET cohort (N = 5) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Grade | % | Grade ≥ 3 | % | All Grade | % | Grade ≥ 3% | All Grade | % | Grade ≥ 3% | % | ||

| Activated partial thromboplastin time prolonged | 3 | 21 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 6 | 43 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 80 | 1 | 20 |

| Alkaline phosphatase increased | 5 | 36 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 1 | 20 |

| alopecia | 6 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anemia | 10 | 71 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 80 | 1 | 20 |

| Anorexia | 5 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 4 | 29 | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 1 | 20 |

| Ataxia | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cognitive disturbance | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 6 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cough | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 4 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 6 | 43 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry skin | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspepsia | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 4 | 29 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 14 | 100 | 1 | 7 | 4 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Headache | 5 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hot flashes | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 14 | 100 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 100 | 1 | 20 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyperkalemia | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypermagnesemia | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypertension | 3 | 21 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 10 | 71 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 80 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 9 | 64 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| Hyponatremia | 5 | 36 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 6 | 43 | 2 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Insomnia | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Lipase increased | 8 | 57 | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 1 | 20 |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 6 | 43 | 4 | 29 | 3 | 60 | 3 | 60 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 20 |

| Mucositis oral | 3 | 21 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 8 | 57 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 80 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Pain | 7 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 5 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Platelet count decreased | 9 | 64 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 0 |

| Pruritus | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rash maculo-papular | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 80 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Weight loss | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White blood cell decreased | 5 | 36 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 60 | 0 | 0 |

The most common treatment-emergent toxicities included fatigue (100%) and hyperglycemia (100%) but mostly low grade, with only one patient reporting grade 3 or above. Elevated serum lipase was observed in 57% of patients, with one patient with grade 4 meeting DLT definition at 200 mg; interestingly, elevated lipase was not reported at 400 mg, but it was also observed in WBRT only patients enrolled in the FLT-PET study. Grade 3 rash was noted in 60% of patients treated at 400 mg, while no high-grade rash was reported at 200 mg or WBRT only patients.

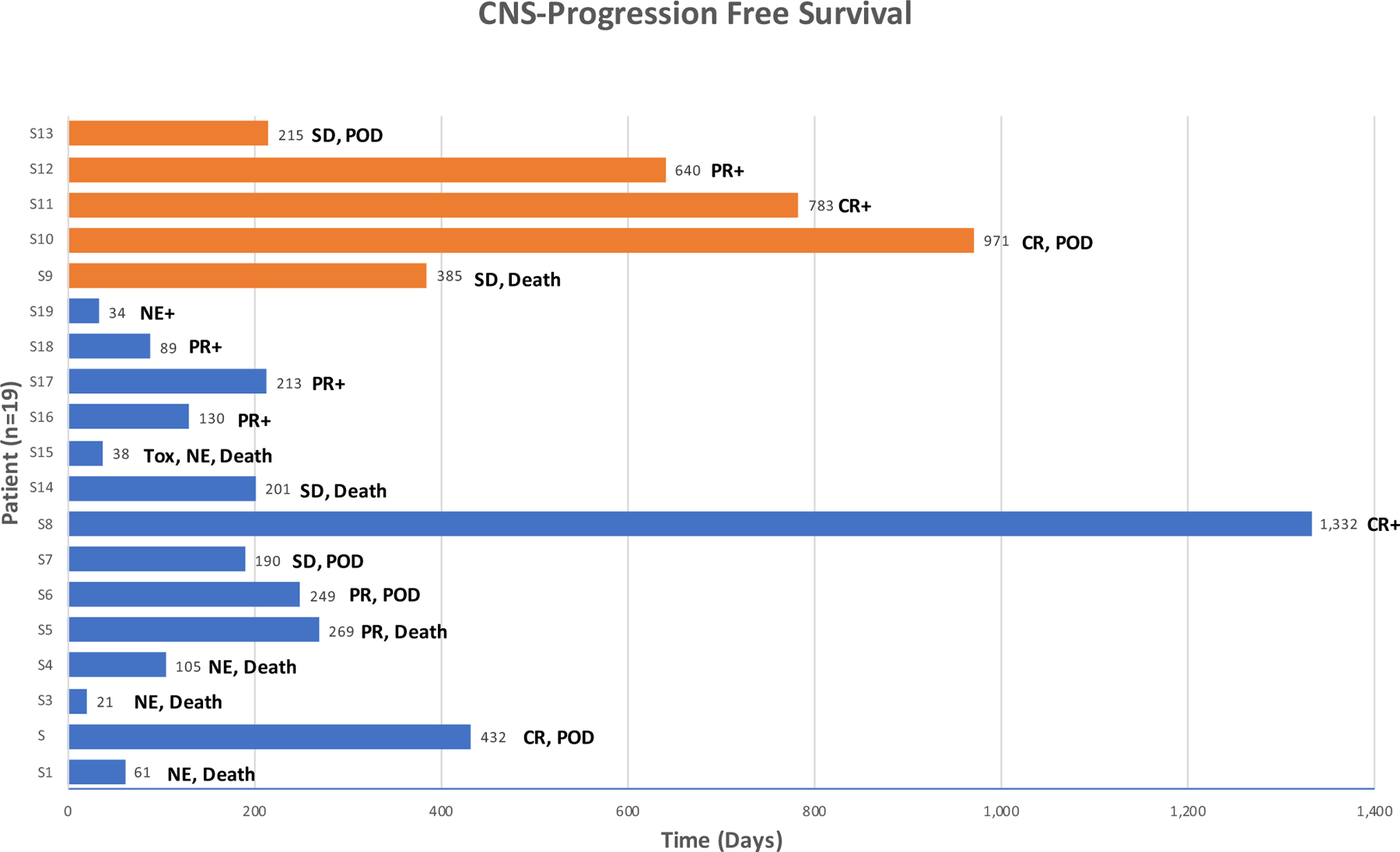

At the time of data cut-off, the median follow up for survivors was 618 days. The median time to death was 201 days, with nine deaths in 19 patients. Of those, six patients remain in follow up after completing the DLT assessment period. Nine deaths were observed at the time of data cut-off, and all were considered to be unrelated to the study treatment. 14 patients out of 19 patients in the phase I study were evaluable for response. Of these 14 evaluable patients, the overall response rate was 71% (10/14), with four complete responses and six partial responses. The median CNS-PFS was 12.8 months (95% confidence interval: 6.7- NR). The clinical response is summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

CNS response and PFS. Central nervous system-progression-free survival graph with types of response, reasons for discontinuation, censoring status at the end of data cut-off, and on study treatment duration for 19 patients on Phase I study. X-axis: individual patients. Y-axis: follow-up time in days. Blue and oragne color marking patients treated at the 200 mg and the 400 mg dose, respectively. CR, complete response. PR, partial response. SD, stable disease. NE, not evaluable. Tox, discontinued due to toxicity. POD, discontinued due to progresson of disease. + , censored at the time of data cut-off

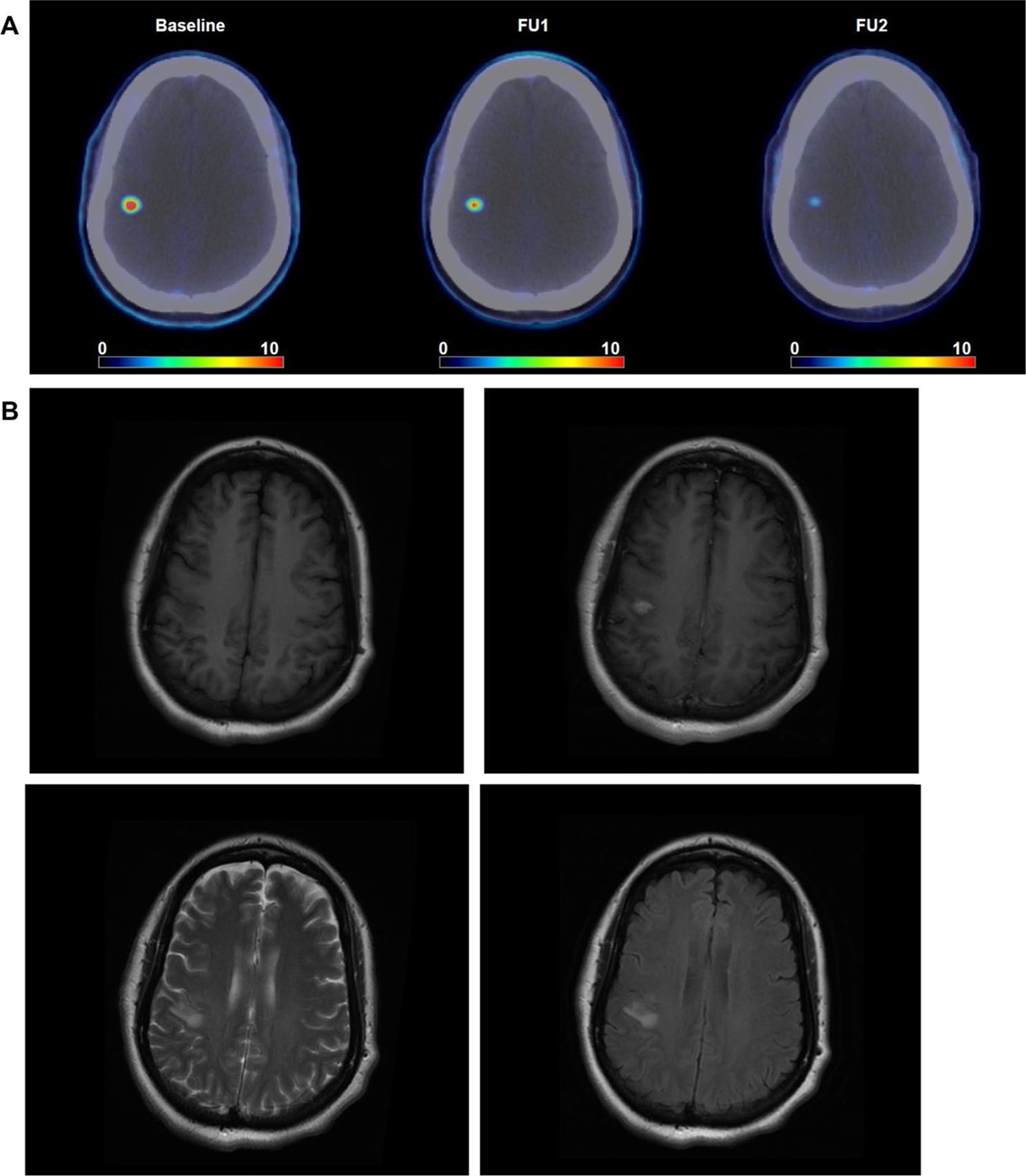

Ten patients in the phase I study and five patients who were treated only with WBRT were enrolled in the correlative FLT-PET study. The enrollment was closed for the WBRT only cohort due to slow accrual. A total of 15 patients had baseline FLT-PET completed, with 14 completing follow up scan 1 (FU1, 7–10 days after WBRT) and nine patients completing additional follow up scan 2 (FU2, 10–12 weeks after WBRT), respectively. All the lesions with FLT-PET uptake had MRI correlates. The representative image of FLT-PET uptake is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

FLT-PET brain metastasis imaging. Example of FLT-PET uptake in brain metastasis and the corresponding MRI images acquired within 2 weeks of baseline FLT-PET. a FLT-PET images at baseline, FU1 and FU2. b corresponding MRI images: top left T1, top right T1 post, bottom left T2, and bottom right T2 FLAIR

Maximum intratumor 18F-FLT SUVs are summarized in Table 3. In total, 35 lesions and 22 lesions were analyzed in WBRT + sorafenib and WRBT only cohorts, respectively. Included separately are the results for WBRT with sorafenib and WBRT only cohorts, as well as for normal brain tissue (SUVmean). Compared to 18F-FLT tumor uptake, 18F-FLT uptake in normal brain tissue was substantially lower and in agreement with previous reports. In 12 out of 35 lesions in the WBRT + sorafenib cohort and 4 out of 22 lesions in the WBRT only cohort, the uptake on the 2nd 18F-FLT-PET (FU1) was indistinguishable from the radiotracer accumulation in normal brain. For these lesions, patient-specific normal brain SUV values were used. The decrease in 18F-FLT SUV was significant in both cohorts (paired t-test) and was more pronounced for the WBRT + sorafenib cohort compared to WBRT only cohort. Additionally, the lesions from the WBRT + sorafenib cohort exhibited lower 18F-FLT SUV on 2nd scan (FU1) compared to those from the WBRT only cohort (unpaired t-test; p = 0.05), despite their 18F-FLT SUV being marginally higher on the 1st scan (baseline). The differences in 18F-FLT SUV were not significant on the 3rd scan. Overall, a decline in average SUVmax of ≥ 25% was noted in 9/10 (90%) of patients in the WBRT + sorafenib cohort and 2/4 (50%) of WBRT only patients at FU1. The normal brain uptake did not change significantly after the initiation of therapy. The longitudinal trends in SUV uptake are graphically presented per lesion and per patient in Online Resource 2.

Table 3.

Summary of SUVmax derived from 18F-FLT-PET scans (n = 15 patients)

| Cohort | Baseline | Early response | Post-treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| All (n = 57) | 3.5 ± 2.0 (0.9–10.8) | 1.5 ± 1.5 (0.2–7.4) | 0.6 ± 0.6 (0.2–2.6) |

| WBRT + Sorafenib (n = 35) | 3.6 ± 2.3 (1.1–10.8) | 1.2 ± 1.4 (0.2–7.4) | 0.6 ± 0.6 (0.2–2.6) |

| WBRT only (n = 22) | 3.4 ± 1.6 (0.9–5.8) | 2.0 ± 1.5 (0.2–5.2) | 0.5 ± 0.5 (0.2–1.8) |

| Normal brain tissue (SUVmean; n = 15) | 0.28 ± 0.04 (0.20–0.35) | 0.26 ± 0.04 (0.20–0.33) | 0.29 ± 0.06 (0.20–0.38) |

Mean ± standard deviation (range)

SUV standardized uptake value, corrected by body weight, as calculated from the summed 15-min image corresponding to last 15-min of the 60-min dynamic acquisition

Discussion

WBRT remains an important treatment option in the setting of more diffuse disease involvement (e.g., miliary metastases, leptomeningeal involvement) [4, 6, 7, 32, 33]. In a ‘real life’ cohort study of 16,701 BC patients by a French group, 45% of patients with BC patients with CNS metastases received WBRT [32]. In a Korean cohort study of BCBM diagnosed from 2000 to 2014, WBRT was the most common first treatment after the diagnosis of BM [33]. Distant or regional relapse remains common after SRS, especially in HER2 negative patients, and salvage WBRT may be offered at that time [34]. The prognosis for patients who undergo WBRT remains poor, and historically, there has been an effort to improve the outcome in this setting.

Many trials using a combination of systemic therapy and WBRT have been evaluated with the hope of leveraging radiosensitizing properties associated with the systemic agent but without a practice-changing result to date. In this study, we selected sorafenib with a rationale that this drug would not only have radiosensitizing property but also activity in BC and a potential to cross the blood–tumor barrier/the blood–brain barrier [35–38]. Efficacy in CNS metastases from renal cell carcinoma provided further motivation [16, 38, 39].

The modest dose of 200 mg of sorafenib is tolerable with WBRT in BC patients. This dose is lower than the approved dose as a single agent in other solid tumors and also lower than the MTD with SRS [40]. The difference in MTD may be due to the difference in radiation modality given rash was the common DLT and may be related to the dermatologic extent of the radiation field. Our study provides safety data when considering a continuation of sorafenib (albeit at a lower dose) during WBRT for other solid tumors where sorafenib is used in routine clinical care.

In addition, some studies have examined the impact of sorafenib dose on cellular and immune pathway activations in cancer as well as liver disease [41–43]. Interestingly, studies have reported that a dose-dependent immunomodulatory effect of sorafenib, with a higher dose being more immunosuppressive [42, 43]. There is an increased interest in incorporating radiation and VEGF-targeting to enhance immune-microenvironment and leverage the use of immunotherapy for both primary brain tumors and brain metastases [44–48]. The activity of low dose sorafenib (vs. higher dose) may of interest to examine its potential to enhance immunogenicity for brain metastases.

In the phase II trial of WBRT with or without temozolomide in BC patients, ORRs were 36% and 30% in WBRT only and WBRT with temozolomide, respectively, with no CR in either arm [49]. There have been trials combining radiotherapy and anti-VEGF therapy. REBECA was a phase I study combining radiation therapy with bevacizumab in patients with BM, including 13/19 patients with BC [50]. While a response rate of 62.5% was reported, there was one CR. Compared to the other studies examining a combination of WBRT with radiosensitizers specifically in BC patients, the observed response rate of 71% (10/14) with 4 CRs, is noteworthy.

The radiologic assessment criteria for BM have evolved over time from the MacDonald criteria, which was routinely used in clinical trials at the time of activation of this study, although the determination of CR may not be significantly affected. However, the number of CRs in this trial is still much higher than the historical response rate of 36% with WBRT alone. As sorafenib and/or other novel anti-VEGF agents in combination with brain RT are explored in the future beyond the phase I setting, more contemporary RANO criteria and incorporation of patient-reported outcome for neurocognitive assessment and quality of life metrics may be considered.

We saw a signal of early FLT change, suggestive of an antiproliferative effect. However, we recognize that our sample size was small, and the enrollment was stopped early for the WBRT cohort only due to slow accrual. Therefore, we decided to present the data graphically for each case. The use of FLT-PET has been examined in 10 BCBM patients receiving investigational drug therapy [31], with an observed association between MRI and FLT-PET changes after one cycle (21 days) [10]. PET has been proposed as a complementary radiologic tool for MRI [51]. While amino acid tracer has more evidence to date, there is a relative paucity of data for other PET tracers, upon which our study shines some new light [27]. FLT-PET could be further explored among patients undergoing SRS and novel systemic therapies in settings with longer follow up to better understand the prognostic implications of early changes in FLT-PET uptake following such intervention. A reliable early indicator of durable response to WBRT, or lack of durable response of a particular lesion to WBRT could inform subsequent CNS monitoring strategy and/or suggest a potential role for SRS. A novel complementary tool to assess early response or treatment effect may also be relevant for patients undergoing immunotherapy (either for systemic control or asymptomatic brain metastases), particularly where pseudoprogression is a potential confounder.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that sorafenib at a modest dose can be given safely with WBRT and provides practical safety information for clinicians seeking to continue sorafenib for systemic disease during WBRT. We observed a signal suggestive of promising efficacy for the combination of WBRT + sorafenib in the context of poor outcomes for patients undergoing WBRT alone. Early changes with FLT-PET suggest a greater antiproliferative effect with sorafenib + WBRT versus WBRT alone. Combinations of WBRT + sorafenib or newer anti-VEGF TKIs warrant further clinical evaluation.

Supplementary Material

Funding

Bayer (phase I trial, ADS), Susan G. Komen Foundation (FLT imaging, ADS), and American Society of Clinical Oncology Gianni Bonadonna Breast Cancer Research Fellowship (AM).

Footnotes

Trial and Clinical Registry

Trial registration numbers and dates: NCT01724606 (November 12, 2012) and NCT01621906 (June 18, 2012).

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06209-4.

Conflict of interest ADS: research support (Novartis, Bayer, Odonate, Nektar), consulting (Genomic Health, Genentech, Novartis, Lilly, Pfizer, Odonate, Nektar, Immunomedics), speaker (Genomic Health, Genentech, Novartis, Lilly, Pfizer, Immunomedics). AM: research support (Novartis, Lilly, Takeda Millenium, Eisai/H3B Biomedicine, Seattle Genetics, Pfizer/National Comprehensive Cancer Network) and consulting (Lilly). KJ: Consultant/Advisory Board (Novartis, Spectrum pharmaceuticals, ADC Therapeutics, Pfizer, BMS, Jounce Therapeutics, Taiho Oncology, Genentech, Synthon, Abbvie, Astra Zeneca, Lilly Pharmaceuticas) and research support (Novartis, Clovis Oncology, Genentech, Astra Zeneca, ADC Therapeutics, Novita Pharmaceuticals, Debio Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Lilly Pharmaceuticals, Zymeworks, Immunomedics, Puma Biotechnology).

Declarations

Ethical approval The authors confirm that the study was approved by the appropriate ethics committee (Memorial Sloan Kettering Institutional Review Board) and certify that the study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study according to the appropriate institutional guideline.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request after an institutional and sponsor review and approval.

References

- 1.Achrol AS, Rennert RC, Anders C, Soffietti R, Ahluwalia MS, Nayak L, Peters S, Arvold ND, Harsh GR, Steeg PS, Chang SD (2019) Brain metastases. Nat Rev Dis Primers 5(1):5. 10.1038/s41572-018-0055-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morikawa A, Jhaveri K, Seidman A (2013) Clinical trials for breast cancer with brain metastases challenges and new directions. Curr Breast Cancer Rep 5(4):293–301. 10.1007/s12609-013-0120-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anders CK (2016) Management of brain metastases in breast cancer. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol H&O 14(9):686–688 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim H, Yaroko AA (2019) Palliative external beam radiotherapy for advanced breast cancer patients with brain metastasis in the university college hospital Ibadan. Ann Afr Med 18(3):127–131. 10.4103/aam.aam_42_18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cagney DN, Lamba N, Montoya S, Li P, Besse L, Martin AM, Brigell RH, Catalano PJ, Brown PD, Leone JP, Tanguturi SK, Haas-Kogan DA, Alexander BM, Lin NU, Aizer AA (2019) Breast cancer subtype and intracranial recurrence patterns after brain-directed radiation for brain metastases. Breast Cancer Res Treat 176(1):171–179. 10.1007/s10549-019-05236-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abe E, Aoyama H (2012) The role of whole brain radiation therapy for the management of brain metastases in the era of stereotactic radiosurgery. Curr Oncol Rep 14(1):79–84. 10.1007/s11912-011-0201-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aoyama H (2011) Radiation therapy for brain metastases in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer 18(4):244–251. 10.1007/s12282-010-0207-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown PD, Pugh S, Laack NN, Wefel JS, Khuntia D, Meyers C, Choucair A, Fox S, Suh JH, Roberge D, Kavadi V, Bentzen SM, Mehta MP, Watkins-Bruner D (2013) Memantine for the prevention of cognitive dysfunction in patients receiving whole-brain radiotherapy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Neuro Oncol 15(10):1429–1437. 10.1093/neuonc/not114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mehta MP, Shapiro WR, Phan SC, Gervais R, Carrie C, Chabot P, Patchell RA, Glantz MJ, Recht L, Langer C, Sur RK, Roa WH, Mahe MA, Fortin A, Nieder C, Meyers CA, Smith JA, Miller RA, Renschler MF (2009) Motexafin gadolinium combined with prompt whole brain radiotherapy prolongs time to neurologic progression in non-small-cell lung cancer patients with brain metastases: results of a phase III trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 73(4):1069–1076. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.05.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chargari C, Campana F, Pierga JY, Vedrine L, Ricard D, Le Moulec S, Fourquet A, Kirova YM (2010) Whole-brain radiation therapy in breast cancer patients with brain metastases. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 7(11):632–640. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.El Kaffas A, Al-Mahrouki A, Tran WT, Giles A, Czarnota GJ (2014) Sunitinib effects on the radiation response of endothelial and breast tumor cells. Microvasc Res 92:1–9. 10.1016/j.mvr.2013.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee JH, Shim JW, Choi YJ, Heo K, Yang K (2013) The combination of sorafenib and radiation preferentially inhibits breast cancer stem cells by suppressing HIF-1alpha expression. Oncol Rep 29(3):917–924. 10.3892/or.2013.2228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmidt B, Lee HJ, Ryeom S, Yoon SS (2012) Combining bevacizumab with radiation or chemoradiation for solid tumors: a review of the scientific rationale, and clinical trials. Curr Angiogenes 1(3):169–179. 10.2174/2211552811201030169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moreno-Aspitia A (2010) Clinical overview of sorafenib in breast cancer. Future Oncol 6(5):655–663. 10.2217/fon.10.41s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dattachoudhury S, Sharma R, Kumar A, Jaganathan BG (2020) Sorafenib inhibits proliferation, migration and invasion of breast cancer cells. Oncology 98(7):478–486. 10.1159/000505521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heravi M, Tomic N, Liang L, Devic S, Holmes J, Deblois F, Radzioch D, Muanza T (2012) Sorafenib in combination with ionizing radiation has a greater anti-tumour activity in a breast cancer model. Anticancer Drugs 23(5):525–533. 10.1097/CAD.0b013e32834ea5b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gradishar WJ, Kaklamani V, Sahoo TP, Lokanatha D, Raina V, Bondarde S, Jain M, Ro SK, Lokker NA, Schwartzberg L (2013) A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study evaluating sorafenib in combination with paclitaxel as a first-line therapy in patients with HER2-negative advanced breast cancer. Eur J Cancer 49(2):312–322. 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonelli MA, Fumarola C, Alfieri RR, La Monica S, Cavazzoni A, Galetti M, Gatti R, Belletti S, Harris AL, Fox SB, Evans DB, Dowsett M, Martin LA, Bottini A, Generali D, Petronini PG (2010) Synergistic activity of letrozole and sorafenib on breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 124(1):79–88. 10.1007/s10549-009-0714-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baselga J, Segalla JG, Roche H, Del Giglio A, Pinczowski H, Ciruelos EM, Filho SC, Gomez P, Van Eyll B, Bermejo B, Llombart A, Garicochea B, Duran MA, Hoff PM, Espie M, de Moraes AA, Ribeiro RA, Mathias C, Gil Gil M, Ojeda B, Morales J, Kwon Ro S, Li S, Costa F (2012) Sorafenib in combination with capecitabine: an oral regimen for patients with HER2-negative locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 30(13):1484–1491. 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.7771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fumarola C, Caffarra C, La Monica S, Galetti M, Alfieri RR, Cavazzoni A, Galvani E, Generali D, Petronini PG, Bonelli MA (2013) Effects of sorafenib on energy metabolism in breast cancer cells: role of AMPK-mTORC1 signaling. Breast Cancer Res Treat 141(1):67–78. 10.1007/s10549-013-2668-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cha J, Seong J, Lee IJ, Kim JW, Han KH (2013) Feasibility of sorafenib combined with local radiotherapy in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Yonsei Med J 54(5):1178–1185. 10.3349/ymj.2013.54.5.1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu W, Gu K, Yu Z, Yuan D, He M, Ma N, Lai S, Zhao J, Ren Z, Zhang X, Shao C, Jiang GL (2013) Sorafenib potentiates irradiation effect in hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Lett 329(1):109–117. 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisele SC, Wen PY, Lee EQ (2016) Assessment of brain tumor response: RANO and its offspring. Curr Treat Options Oncol 17(7):35. 10.1007/s11864-016-0413-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin NU, Lee EQ, Aoyama H, Barani IJ, Barboriak DP, Baumert BG, Bendszus M, Brown PD, Camidge DR, Chang SM, Dancey J, de Vries EG, Gaspar LE, Harris GJ, Hodi FS, Kalkanis SN, Linskey ME, Macdonald DR, Margolin K, Mehta MP, Schiff D, Soffietti R, Suh JH, van den Bent MJ, Vogelbaum MA, Wen PY, Response Assessment in Neuro-Oncology group (2015) Response assessment criteria for brain metastases: proposal from the RANO group. Lancet Oncol 16(6):e270–278. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brandsma D, van den Bent MJ (2009) Pseudoprogression and pseudoresponse in the treatment of gliomas. Curr Opin Neurol 22(6):633–638. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328332363e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, Cloughesy TF, Sorensen AG, Galanis E, Degroot J, Wick W, Gilbert MR, Lassman AB, Tsien C, Mikkelsen T, Wong ET, Chamberlain MC, Stupp R, Lamborn KR, Vogelbaum MA, van den Bent MJ, Chang SM (2010) Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in neuro-oncology working group. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 28(11):1963–1972. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.3541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Galldiks N, Langen KJ, Albert NL, Chamberlain M, Soffietti R, Kim MM, Law I, Le Rhun E, Chang S, Schwarting J, Combs SE, Preusser M, Forsyth P, Pope W, Weller M, Tonn JC (2019) PET imaging in patients with brain metastasis-report of the RANO/PET group. Neuro Oncol 21(5):585–595. 10.1093/neuonc/noz003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Been LB, Suurmeijer AJ, Cobben DC, Jager PL, Hoekstra HJ, Elsinga PH (2004) [18F]FLT-PET in oncology: current status and opportunities. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 31(12):1659–1672. 10.1007/s00259-004-1687-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen W, Delaloye S, Silverman DH, Geist C, Czernin J, Sayre J, Satyamurthy N, Pope W, Lai A, Phelps ME, Cloughesy T (2007) Predicting treatment response of malignant gliomas to bevacizumab and irinotecan by imaging proliferation with [18F] fluorothymidine positron emission tomography: a pilot study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 25(30):4714–4721. 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikaki A, Papadopoulos V, Valotassiou V, Efthymiadou R, Angelidis G, Tsougos I, Prassopoulos V, Georgoulias P (2019) Evaluation of the performance of 18F-fluorothymidine positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FLT-PET/CT) in metastatic brain lesions. Diagnostics (Basel). 10.3390/diagnostics9010017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Sullivan CC, Lindenberg M, Bryla C, Patronas N, Peer CJ, Amiri-Kordestani L, Davarpanah N, Gonzalez EM, Burotto M, Choyke P, Steinberg SM, Liewehr DJ, Figg WD, Fojo T, Balasubramaniam S, Bates SE (2016) ANG1005 for breast cancer brain metastases: correlation between (18)F-FLT-PET after first cycle and MRI in response assessment. Breast Cancer Res Treat 160(1):51–59. 10.1007/s10549-016-3972-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasquier D, Darlix A, Louvel G, Fraisse J, Jacot W, Brain E, Petit A, Mouret-Reynier MA, Goncalves A, Dalenc F, Deluche E, Fresnel JS, Augereau P, Ferrero JM, Geffrelot J, Fumet JD, Lecouillard I, Cottu P, Petit T, Uwer L, Jouannaud C, Leheurteur M, Dieras V, Robain M, Mouttet-Audouard R, Bachelot T, Courtinard C (2020) Treatment and outcomes in patients with central nervous system metastases from breast cancer in the real-life ESME MBC cohort. Eur J Cancer 125:22–30. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JS, Kim K, Jung W, Shin KH, Im SA, Kim HJ, Kim YB, Chang JS, Choi DH, Park YH, Kim DY, Kim TH, Choi BO, Lee SW, Kim S, Kwon J, Kang KM, Chung WK, Kim KS, Nam JH, Yoon WS, Kim JH, Cha J, Oh YK, Kim IA (2019) Survival outcomes of breast cancer patients with brain metastases: a multicenter retrospective study in Korea (KROG 16–12). Breast 49:41–47. 10.1016/j.breast.2019.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vern-Gross TZ, Lawrence JA, Case LD, McMullen KP, Bourland JD, Metheny-Barlow LJ, Ellis TL, Tatter SB, Shaw EG, Urbanic JJ, Chan MD (2012) Breast cancer subtype affects patterns of failure of brain metastases after treatment with stereotactic radiosurgery. J Neurooncol 110(3):381–388. 10.1007/s11060-012-0976-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwartzberg LS, Tauer KW, Hermann RC, Makari-Judson G, Isaacs C, Beck JT, Kaklamani V, Stepanski EJ, Rugo HS, Wang W, Bell-McGuinn K, Kirshner JJ, Eisenberg P, Emanuelson R, Keaton M, Levine E, Medgyesy DC, Qamar R, Starr A, Ro SK, Lokker NA, Hudis CA (2013) Sorafenib or placebo with either gemcitabine or capecitabine in patients with HER-2-negative advanced breast cancer that progressed during or after bevacizumab. Clin Cancer Res Off J Am Assoc Cancer Res 19(10):2745–2754. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu D, Hu Y, Li J, Wang X (2018) Symptomatic treatment of brain metastases in renal cell carcinoma with sorafenib. J Cancer Res Ther 14(Supplement):S1223–S1226. 10.4103/0973-1482.189402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nabors LB, Supko JG, Rosenfeld M, Chamberlain M, Phuphanich S, Batchelor T, Desideri S, Ye X, Wright J, Gujar S, Grossman SA (2011) Phase I trial of sorafenib in patients with recurrent or progressive malignant glioma. Neuro Oncol 13(12):1324–1330. 10.1093/neuonc/nor145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ranze O, Hofmann E, Distelrath A, Hoeffkes HG (2007) Renal cell cancer presented with leptomeningeal carcinomatosis effectively treated with sorafenib. Onkologie 30(8–9):450–451. 10.1159/0000105131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Massard C, Zonierek J, Gross-Goupil M, Fizazi K, Szczylik C, Escudier B (2010) Incidence of brain metastases in renal cell carcinoma treated with sorafenib. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol ESMO 21(5):1027–1031. 10.1093/annonc/mdp411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arneson K, Mondschein J, Stavas M, Cmelak AJ, Attia A, Horn L, Niermann K, Puzanov I, Chakravarthy AB, Xia F (2017) A phase I trial of concurrent sorafenib and stereotactic radiosurgery for patients with brain metastases. J Neurooncol 133(2):435–442. 10.1007/s11060-017-2455-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jian C, Fu J, Cheng X, Shen LJ, Ji YX, Wang X, Pan S, Tian H, Tian S, Liao R, Song K, Wang HP, Zhang X, Wang Y, Huang Z, She ZG, Zhang XJ, Zhu L, Li H (2020) Low-dose sorafenib acts as a mitochondrial uncoupler and ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Metab 31(6):1206. 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lohmeyer J, Nerreter T, Dotterweich J, Einsele H, Seggewiss-Bernhardt R (2018) Sorafenib paradoxically activates the RAS/RAF/ERK pathway in polyclonal human NK cells during expansion and thereby enhances effector functions in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Clin Exp Immunol 193(1):64–72. 10.1111/cei.13128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iyer RV, Maguire O, Kim M, Curtin LI, Sexton S, Fisher DT, Schihl SA, Fetterly G, Menne S, Minderman H (2019) Dose-dependent sorafenib-induced immunosuppression is associated with aberrant NFAT activation and expression of PD-1 in T cells. Cancers (Basel). 10.3390/cancers11050681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fukumura D, Kloepper J, Amoozgar Z, Duda DG, Jain RK (2018) Enhancing cancer immunotherapy using antiangiogenics: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 15(5):325–340. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2018.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang Y, Goel S, Duda DG, Fukumura D, Jain RK (2013) Vascular normalization as an emerging strategy to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Can Res 73(10):2943–2948. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao K, Abbassi L, Romano E, Kirova Y (2020) Radiation therapy and immunotherapy in breast cancer treatment: preliminary data and perspectives. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 10.1080/14737140.2021.1868993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Su Z, Zhou L, Xue J, Lu Y (2020) Integration of stereotactic radiosurgery or whole brain radiation therapy with immunotherapy for treatment of brain metastases. Chin J Cancer Res 32(4):448–466. 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.04.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Formenti SC, Demaria S (2020) Future of Radiation and Immunotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 108(1):3–5. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2020.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cao KI, Lebas N, Gerber S, Levy C, Le Scodan R, Bourgier C, Pierga JY, Gobillion A, Savignoni A, Kirova YM (2015) Phase II randomized study of whole-brain radiation therapy with or without concurrent temozolomide for brain metastases from breast cancer. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol ESMO 26(1):89–94. 10.1093/annonc/mdu488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Levy C, Allouache D, Lacroix J, Dugue AE, Supiot S, Campone M, Mahe M, Kichou S, Leheurteur M, Hanzen C, Dieras V, Kirova Y, Campana F, Le Rhun E, Gras L, Bachelot T, Sunyach MP, Hrab I, Geffrelot J, Gunzer K, Constans JM, Grellard JM, Clarisse B, Paoletti X (2014) REBECA: a phase I study of bevacizumab and whole-brain radiation therapy for the treatment of brain metastasis from solid tumours. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol ESMO 25(12):2351–2356. 10.1093/annonc/mdu465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galldiks N, Abdulla DS, Scheffler M, Wolpert F, Werner JM, Huellner MW, Stoffels G, Schweinsberg V, Schlaak M, Kreuzberg N, Landsberg J, Lohmann P, Ceccon G, Baues C, Trommer M, Celik E, Ruge MI, Kocher M, Marnitz S, Fink GR, Tonn JC, Weller M, Langen KJ, Wolf J, Mauch C (2020) Treatment monitoring of immunotherapy and targeted therapy using (18)F-FET PET in patients with melanoma and lung cancer brain metastases: initial experiences. J Nucl Med Off Publ Soc Nucl Med. 10.2967/jnumed.120.248278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request after an institutional and sponsor review and approval.