Abstract

Sleep is essential for the optimal consolidation of newly acquired memories. This study examines the neurophysiological processes underlying memory consolidation during sleep, via reactivation. Here, we investigated the impact of slow wave - spindle (SW-SP) coupling on regionally-task-specific brain reactivations following motor sequence learning. Utilizing simultaneous EEG-fMRI during sleep, our findings revealed that memory reactivation occured time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes, and specifically in areas critical for motor sequence learning. Notably, these reactivations were confined to the hemisphere actively involved in learning the task. This regional specificity highlights a precise and targeted neural mechanism, underscoring the crucial role of SW-SP coupling. In addition, we observed double-dissociation whereby primary sensory areas were recruited time-locked to uncoupled spindles; suggesting a role for uncoupled spindles in sleep maintenance. These findings advance our understanding the functional significance of SW-SP coupling for enhancing memory in a regionally-specific manner, that is functionally dissociable from uncoupled spindles.

Subject terms: Slow-wave sleep, Non-REM sleep, Consolidation, Motor cortex, Replay

Simultaneous EEG-fMRI shows that slow wave-coupled sleep spindles promote region-specific memory reactivation after motor learning, revealing distinct roles for coupled vs. uncoupled spindles in sleep-dependent memory consolidation.

Introduction

Sleep is crucial for optimal consolidation of newly acquired memories, via memory trace reactivation1,2. Physiological reactivation of newly formed memory traces during sleep3,4, results in the transformation, integration and strengthening of the memory trace5–9, ultimately supporting enhanced performance. One of the key sleep features involved in the consolidation of memories, and in particular memory for motor skills, is the sleep spindle; brief bursts of oscillatory activity (~11–16 Hz) that characterize and predominate non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. In fact, several studies have demonstrated learning-dependent increases in sleep spindle activity following motor skill learning (MSL)10–13. Spindles have also been found to be correlated with both behavioral improvements14 and sleep-dependent changes of activity in brain structures which support motor skills15,16.

Advances in simultaneous EEG-fMRI recordings have enabled the measurement of regional brain activity and functional connectivity, time-locked precisely to spontaneous events during sleep such as spindles17–22 and slow waves18,19,23 thereby providing insights into systems-level changes in brain activity that reflect memory consolidation during sleep. These changes impact how brain regions communicate with one another during sleep, reflecting complex neural interactions crucial for memory processes20,21,24. Brain areas recruited during spontaneous spindle events include: the thalamus and the temporal lobe17–19,21,25, as well as activation of the cingulate cortex and motor cortical areas21,25. Critically, however, activation of areas related to the acquisition of new motor skills and related cognitive functions, time-locked to spindle events have also been reported in subcortical structures like the putamen19,21,26 and hippocampus4,18.

For example, our previous work has demonstrated a direct link between sleep spindles, the offline reactivation of key brain regions that support motor sequence memory and offline performance improvements3. These results showed that brain regions recruited during motor sequence learning, like the striatum, were subsequently reactivated time-locked to sleep spindles. The extent of this reactivation was related to the magnitude of the enhancement in performance the following day, hence providing direct support for the hypothesis that sleep-dependent memory consolidation takes place via reactivation of brain regions recruited during initial learning. Analogous results have been found for declarative memory as well4,27. Finally, the link between spindles and motor memory consolidation has also been suggested to be regionally-specific11. In their study, Nishida and Walker11 utilized a unimanual sequential finger-tapping task to explore how motor learning was integrated during sleep. Their findings revealed that enhancement of offline motor skill memory was closely associated with an increase in sleep spindle activity. Notably, this increase was predominantly observed over motor cortical regions that were actively engaged during the learning phase.

Spindles, however, do not always occur—or act, in isolation. Rather, they are often part of slow wave—spindle—hippocampal ripple complexes, whereby ripples are nested in the excitatory troughs of spindles, and spindles are nested in the excitatory troughs (“up-states”) of slow waves28. Slow wave-spindle (SW-SP) coupling has previously been associated with memory consolidation in both young and older adults, and is considered an index of neural plasticity29–32. Recent results from our group have identified dissociable patterns of brain activation when comparing slow wave-coupled spindles, uncoupled spindles, and, uncoupled slow waves33. Importantly, these differences in spindle coupling not only manifest at a physiological level but also correlate with specific cognitive functions. For example, we have found that the relationship between Fluid Intelligence (i.e., reasoning abilities) and sleep spindles22,24,34 is dependent on the coupling status (i.e., coupled vs. uncoupled) of the spindles35. However, it remains to be investigated how brain activations associated with SW-coupled spindle complexes relate to motor skills memory consolidation. Specifically, the functional significance of activations time-locked to SW-coupled spindle complexes, as well as those specific to uncoupled spindles, in this context is still unknown, and is the main aim of the current study.

In line with previous studies using simultaneous EEG-fMRI recordings, we expect to observe a relationship between SW-SP complexes and motor skills memory consolidation using a unimanual MSL task, wherein participants exclusively use their left hand. We hypothesize that brain activations time-locked to SW-SP complexes will be primarily associated to motor skills memory consolidation, especially in areas within the striato-cerebello-cortical network36,37, including the striatum, hippocampus, parietal cortex, cerebellum, and motor cortical regions, as well as areas important for spindle generation, such as the thalamus. Finally, we expect to observe higher activations in a regionally-specific manner; greater in the trained hemisphere (i.e., contralateral to the left hand) as compared to the untrained one.

Results

Performance and offline gains in MSL

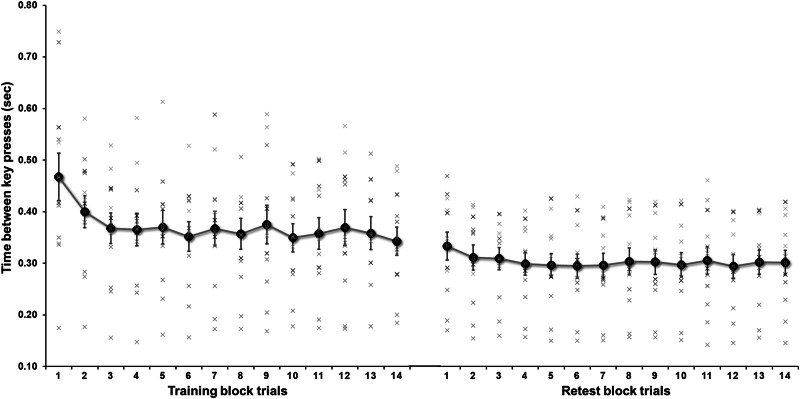

A one-way repeated measures ANOVA (Dataset 1, N = 12), revealed a significant improvement in performance over blocks of trials (F(13,143) = 6.48, p < 0.001). Follow-up paired samples t-tests revealed a dynamic progression in MSL performance measured as the time between key presses over the course of the training session. Follow-up tests showed that performance between the first and second blocks showed a pronounced enhancement (t(11) = 2.667, p = 0.022) as well as from the second to the third block (t(11) = 2.853, p = 0.016), suggesting rapid skill acquisition at the early stages (first four blocks of trails). The overall data depict a sterotypical non-linear learning curve characterized by early, rapid improvement followed by asymptotic performance (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mean (±SEM) performance speed (inter-key press interval) during training session (left) and retest session (right) for the explicit motor sequence learning (MSL) task (Dataset 1; N = 12).

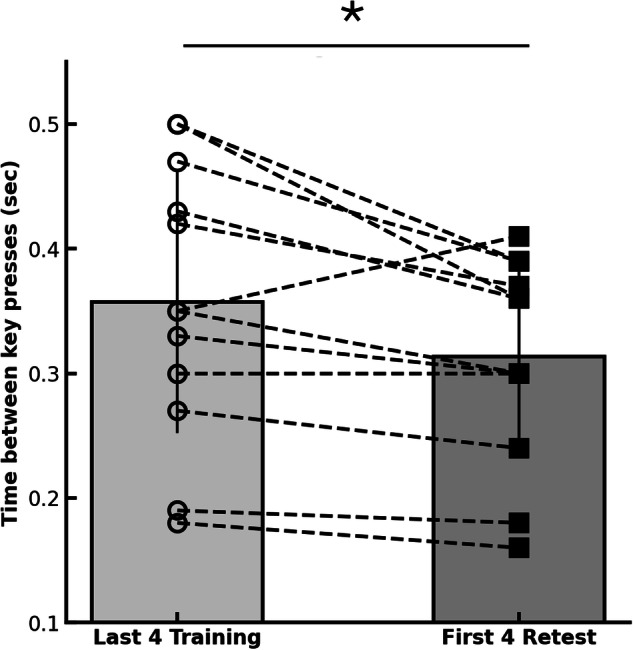

Further analysis compared the average performance of the last four blocks of training to the average performance during the first four blocks at retest, the next day. There was a significant difference in performance gains on the MSL task from training to retest ((t(11) = 2.91, p = 0.014), but not for the CTRL task (t(11) = −1.31, p = 0.214) suggesting that sequence memory was consolidated overnight (Fig. 2). The CTRL task average interval between key presses was 0.30 ms (SEM = 0.01) during the last four blocks of training and 0.31 ms (SEM = 0.001) during the first 4 blocks of retest. Performance was flat from block to block.

Fig. 2.

Gains in performance (reflecting consolidation) were measured using the mean (±SEM) inter-key-press interval in the last 4 blocks of the training vs. the first 4 blocks of retest (Dataset 1; N = 12). (* indicates p < 0.05).

Coupled SW-SP events on MSL night

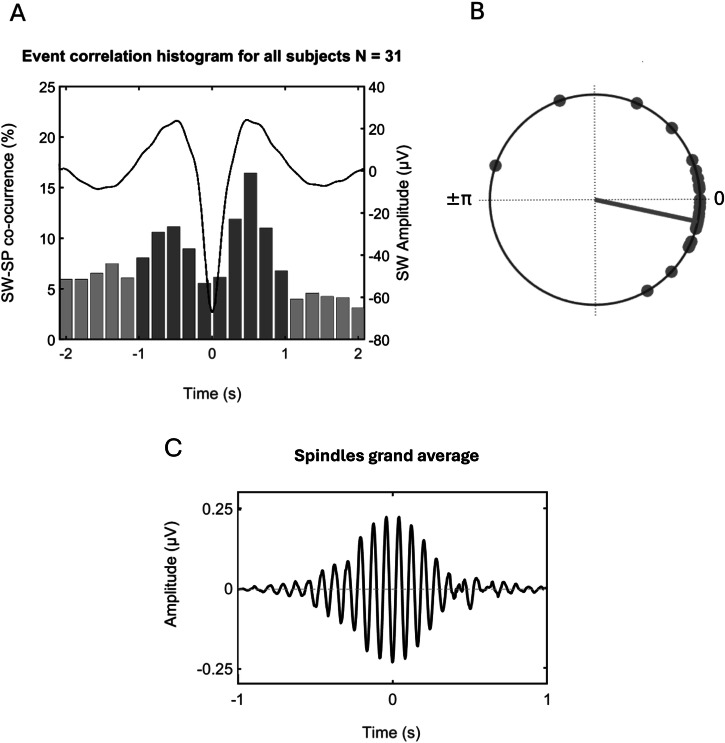

On average, 366 coupled spindles (SEM = 56) and 893 uncoupled spindles (SEM = 95) per participant were identified and included in the analyses. The percentage of coupled spindles across all participants (Combined Dataset, N = 31) is shown in Fig. 3A. Detailed characteristics of the coupled SW-SP and uncoupled spindles are reported in Supplementary Table 2 and Table 3. To investigate the phase relationship between spindles and slow waves, the slow wave phase at the spindle maximum for each SW-SP event was extracted and mean phase angle per individual was computed (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Slow wave-spindle coupling detection summary.

A Coupled spindles percentage histogram for all participants (Combined dataset; N = 31) at all channels of interest (Fz, Cz, Pz, C3, and C4). Each bar represents the number of coupled spindles detected in an interval of 200 ms divided by the total number of spindles averaged across all participants. Average slow wave coupling window for all participants is superimposed in black. B Circular plot of preferred phase for each individual (slow wave phase at spindle amplitude maximum). Dots denote an individual preferred phase (0o slow wave upstate peak, ±180o slow wave downstate peak). The direction of the line indicates the preferred direction of the grand average. Most individuals exhibit spindles adjacent to or immediately following the positive slow wave peak at 0o. C Grand average of spindle events across participants and channels of interest.

To investigate the phase relationship between spindles and slow waves, the slow wave phase at the spindle maximum for each SW-SP event was extracted and mean phase angle per individual was computed. As expected, coupling of spindle events within the slow wave cycle was maximal, shortly before the down-to-up state peak in 26 out of 31 participants (0o; p < 0.001, V-test). Further individual-level analyses revealed a non-uniform distribution (p < 0.05, Rayleigh test) of the preferred phases of SW-SP in 26 out of 31 participants, suggesting that spindles were coupled to slow waves preferentially adjacent to, or immediately following the positive slow wave peak, during the down-to-up state. Phase relationship between spindles and slow waves on the CTRL night (Dataset 1; N = 12) is included in the supplementary material.

Cerebral activations of SW-spindle coupling

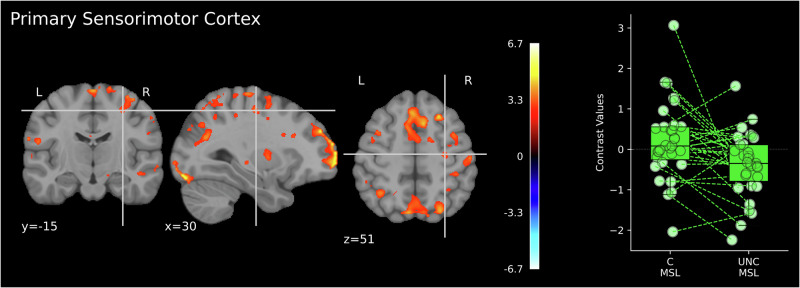

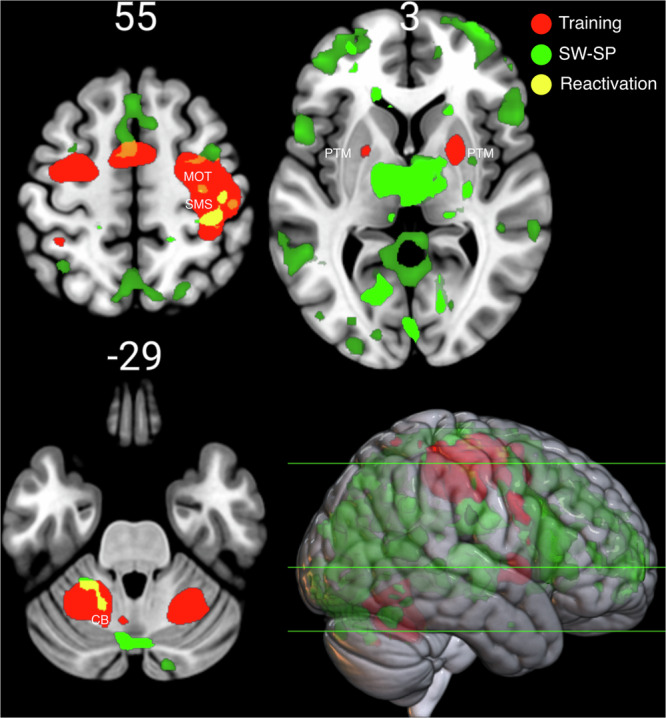

Cerebral activations time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes at Pz (scalp location where fast spindles are maximal) revealed distinct spatial activity patterns as a function of coupling (combined dataset; N = 31). Significant effects were widespread across motor cortical regions including the primary motor cortex, premotor cortex and the supplementary motor area. Notably, these regions were also activated during the MSL training task, indicating reactivation. Brain areas activated during SW-SP complexes and the MSL training task are shown in Fig. 4. Brain regions activated during the MSL training task are reported in Supplementary Table 8. In addition, the increased BOLD signal during coupled SW-SP complexes in the primary motor cortex was lateralized to the “trained” (right) hemisphere, corresponding to the area involved in the execution of hand movements (Figs. 4 and 5). In addition, increased activation during coupled SW-SP complexes was observed in the right thalamus and bilaterally in the medial temporal lobe. In contrast, no regions showed significantly stronger activation during uncoupled SWs. Brain regions with stronger activity time-locked to SWs coupled with spindles compared to uncoupled SWs are reported in Supplementary Table 4.

Fig. 4.

Brain activations during the MSL training task (red) and during coupled SW-SP complexes (green). Overlapping areas indicating reactivation are marked in yellow. These include the motor cortex (MOT), supplementary motor area (SMA), sensorimotor strip (SMS), cerebellum (CB), and putamen (PTM). Numbers indicate the position along the Z-axis, green lines correspond to the locations of each cross-sectional cut shown.

Fig. 5.

Differences in brain activations between coupled SW-SP complexes (C) compared to uncoupled slow waves (UNC) for the primary motor cortex (Combined dataset; N = 31). Statistical maps were thresholded at 0.005 level with k = 30 (the minimum cluster size in voxels) The XYZ coordinates (in millimeters) represent the position in MNI space. Vertical and horizontal lines (crosshairs) indicate the exact location of the peak activation across the coronal, sagittal, and axial planes. The color bar indicates statistically significant t-values corresponding to the contrast with positive values (warm colors) reflecting C>UNC. Whiskers in the boxplots denote 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) beyond the first quartile (Q1) and third quartile (Q3), representing the highest and lowest contrast values, excluding outliers.

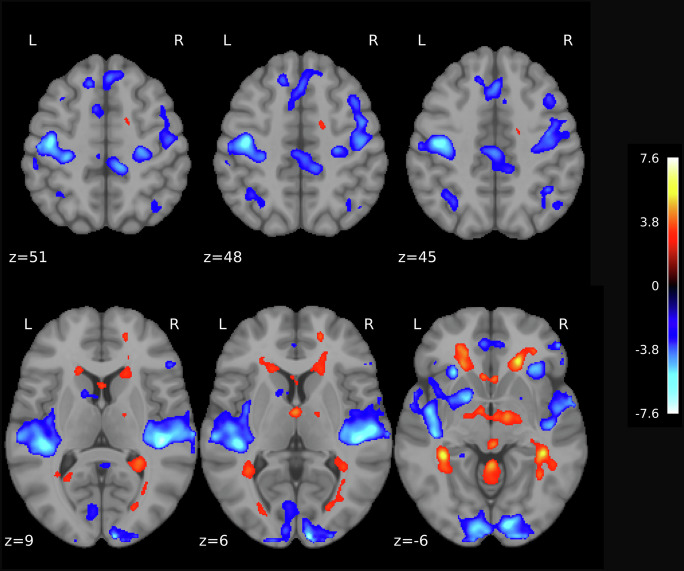

This however, begs the question of what brain regions are specifically activated during uncoupled spindles and what function might they serve? Comparison analyses between SW-SP complexes and isolated spindles are summarized in Fig. 6. Briefly, sensory regions including the primary auditory, primary visual cortex, and somatosensory cortex showed an increased level of activity time-locked to isolated spindle events in comparison to SW-SP complexes. Brain regions with stronger activity time-locked to uncoupled spindles compared to coupled SW-SP complexes are reported in Supplementary Table 5.

Fig. 6.

Differences in brain activations between coupled SW-SP complexes compared to isolated spindles (Combined dataset; N = 31). Cool colors indicate areas where the BOLD activation was higher for isolated spindles compared to SW-SP complexes. Notably, somatosensory cortex (top row), primary auditory and primary visual cortex (bottom row) showed an increased level of activity time-locked to isolated spindle events in comparison to SW-SP complexes. Statistical maps were thresholded at 0.005 level with k = 30 (the minimum cluster size in voxels) The Z coordinates (in millimeters) represent the position in MNI space.

Taken together, these results suggest that coupled SW-SP events recruit brain regions involved in motor skills learning, in a regionally-specific manner. This is consistent with the reactivation hypotheses of spindles for memory consolidation4,38. On the other hand, we observed a double-dissociation, whereby uncoupled spindles actively recruit sensory brain areas in contrast to SW-SP complexes, which is consistent with the sleep maintenance hypothesis of spindles39–42. These complimentary functions of spindles are well-established, and until now have not been disentangled in a single study. The present results suggest a functional dissociation for coupled spindles (e.g., for memory consolidation, via memory trace reactivation) as compared to uncoupled spindles (e.g., for sleep protection via active recruitment of sensory regions).

Regional specificity to a new motor learning experience

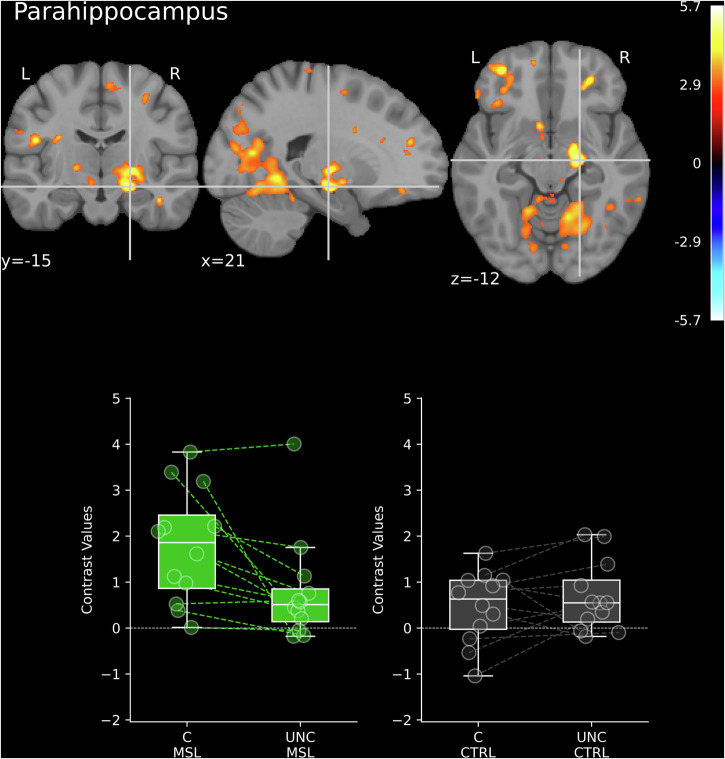

To further examine the effect of SW-SP coupling, specific to new motor learning, we analyzed data from participants who completed both motor sequence learning (MSL) and control tasks (CTRL) (Dataset 1; N = 12). Task-related differences were evident bilaterally in the thalamus, right parahippocampus (Fig. 7), and superior anterior cerebellum (lobules 4 and 5). Post-hoc analysis confirmed that increased activity in these areas was specific to post-MSL sleep and coupled SW-SP complexes. Clusters maximal in the cerebellum also extended to the occipital and medial parietal lobes, with peaks in the calcarine, occipital superior, cuneus, and precuneus. Additional clusters were identified in the medial superior parietal lobe and the superior and lateral prefrontal cortex, bilaterally. Notably, there were no regions that showed significantly stronger signals associated with coupled SW-SP complexes during post-CTRL sleep compared to post-MSL sleep. Learning on the MSL task had no significant impact on activity levels associated with uncoupled SWs, indicating learning-related specificity to coupled SW-SP complexes on the post-MSL night. Activation patterns time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes during sleep after the MSL and CTRL tasks are reported in Supplementary Table 6.

Fig. 7.

Differences in brain activations time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes (C) vs. uncoupled spindles (UNC) after MSL and CRTL task for the right parahippocampus (Dataset 1; N = 12). Statistical maps were thresholded at 0.005 level with k = 30 (the minimum cluster size in voxels). The XYZ coordinates (in millimeters) represent the position in MNI space. Vertical and horizontal lines (crosshairs) indicate the exact location of the peak activation across the coronal, sagittal, and axial planes. The color bar indicates significant t-values corresponding to the contrast with positive values (warm colors) reflecting C>UNC. Whiskers in the boxplots denote 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) beyond the first quartile (Q1) and third quartile (Q3), representing the highest and lowest contrast values, excluding outliers.

Hemisphere-specific effects: contralateral activation patterns

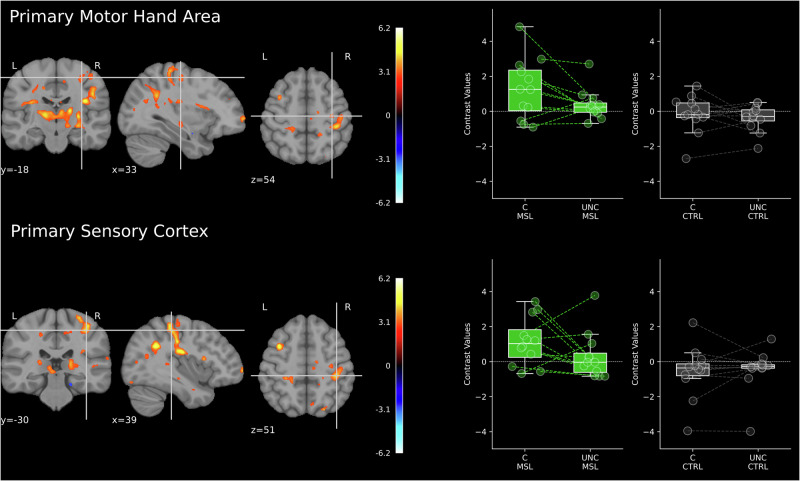

Given the unimanual nature of the MSL task, which required the use of only the left hand, we investigated the extent of regionally-specific lateralization in signal increase during coupled SW-SP complexes (Dataset 1; N = 12). This involved comparing changes in BOLD signal associated with coupled SW-SP complexes at C4 (right motor cortex, contralateral to the trained hand) and C3 (ipsilateral motor cortex). Analysis of activity time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes in the “trained” hemisphere (C4) demonstrated both learning-related effects and task specificity. Post-MSL sleep showed significantly stronger activity, especially lateralized to the “trained” motor cortex. Remarkably, this lateralization was regionally specific and particularly evident in clusters around the precentral and postcentral regions of the hand knob (Fig. 8). The bilateral thalamus also showed increased activity following the MSL task. Additional clusters were identified in the cerebellum, occipital, and parietal lobes. No regions exhibited decreased activity time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes during post-MSL sleep compared to post-CTRL sleep. Furthermore, no significant changes in activity were observed for uncoupled SWs, suggesting that these effects are specific to spindles and to coupled SW-SP complexes. Detailed results are reported in Supplementary Table 7.

Fig. 8.

Differences in brain activations time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes (C) vs. uncoupled spindles (UNC) after MSL and CRTL task for the right precentral gyrus (top) and right postcentral gyrus (bottom) (Dataset 1; N = 12). Statistical maps were thresholded at 0.005 level with k = 30 (the minimum cluster size in voxels) The XYZ coordinates (in millimeters) represent the position in MNI space. Vertical and horizontal lines (crosshairs) indicate the exact location of the peak activation across the coronal, sagittal, and axial planes. The color bar indicates significant t-values corresponding to the contrast with positive values (warm colors) reflecting C>UNC. Whiskers in the boxplots denote 1.5 times the interquartile range (IQR) beyond the first quartile (Q1) and third quartile (Q3), representing the highest and lowest contrast values, excluding outliers.

By contrast, activity time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes at the ipsilateral motor cortex (C3) showed a different pattern. The only ipsilateral brain area with significantly stronger activity during sleep following the MSL task, as compared to post-CTRL sleep, was in the medial parietal lobe, peaking in the precuneus. Instead of increases in activity following the MSL task, regions within the task-related network showed decreases, particularly in the precentral gyrus and insular cortex in the hemisphere ipsilateral to the used hand. Thus, suggesting that the ipsilateral hemisphere is perhaps actively inhibited during SW-SP events, providing further support for highly specific regional recruitment and transformation of the memory trace.

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate how brain activations associated with SW-coupled spindle complexes relate to offline motor skills memory consolidation. The results of this study revealed that when accounting for the coupling status of spindles and slow waves: 1) There was increased activation during coupled SW-SP complexes in the primary motor cortex lateralized to the “trained” (right) hemisphere, corresponding to the area involved in hand movements needed for motor sequence learning, 2) post-MSL sleep showed increased activity in the bilateral thalamus and right parahippocampus specific to coupled SW-SP complexes in comparison to post-CTRL sleep, and, 3) most importantly, post-MSL sleep showed regionally-specific significantly stronger activity especially lateralized to the “trained” motor cortex, and specifically in the hand area. Finally, 4) when spindles are uncoupled (i.e., isolated) they specifically recruited primary sensory areas, including motor, visual and auditory regions, unlike coupled SW-SP complexes. Thus, suggesting distinct roles of coupled and uncoupled spindles for memory consolidation and in protecting sleep from incoming environmental stimuli, respectively. Altogether, these results highlight SW-SP coupling as the key electrophysiological signature related to regionally-specific motor memory consolidation via offline reactivation during sleep, which are functionally dissociable from uncoupled spindles.

Sleep plays a crucial role in the optimal consolidation of newly acquired memories through the reactivation of memory traces. Numerous studies have shown that sleep spindle characteristics, such as amplitude and density, increase in response to motor skill learning12,13,15,38,43–47. More recently3,8, we established a direct connection between sleep spindles and the offline reactivation of key brain regions supporting motor sequence memory consolidation. Critically, converging evidence11,48 suggests that this reactivation, time-locked to sleep spindles is regionally-specific to the motor regions of the trained hemisphere. The brain regions that are uniquely activated by isolated spindles, coupled SW-SP complexes and uncoupled slow waves have been investigated33,35. However, the functional significance of (re)activations time-locked to SW-SP complexes in relation to motor skills memory consolidation has remained to be investigated.

Previous neuroimaging studies in humans have identified sleep-dependent increased activation in the hippocampus following motor sequence learning49–51. Interestingly, recent EEG-fMRI studies suggest that that hippocampal responses are more pronounced during SW-SP complexes specifically, with a diminished response observed during uncoupled (i.e., isolated) spindle events33. Moreover, hippocampal reactivation time-locked to spindles has been observed for both motor skills3 and declarative memory4,27. However, it is important to note that spindles were not divided according to coupling status in these studies, thus the role of coupled and uncoupled spindles for memory reactivation remained ambiguous. Our results suggest that SW-SP coupling is the main component behind the hippocampal responses. In addition, these findings show a regionally specific, hemispheric-dependent reactivation after motor sequence learning.

In addition to the hippocampus, the putamen plays a critical role in sleep-dependent motor memory consolidation52. Previous studies have shown a functional reorganization within the putamen, where activity shifts from associative regions (rostrodorsal) to sensorimotor regions (caudoventral) during memory consolidation3,53,54. Here, we observe significant activation of the putamen during training and again in adjacent regions, time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes. Importantly, these results suggest that these SW-SP complexes are electrophysiological markers of this transformation/reorganization of the memory trace. Specifically, our findings suggest that the pattern of brain activations time-locked to coupled SW-SP complexes are consistent with the shift from associative to sensorimotor regions. This transformation of the memory trace reflects the brain’s transition from consciously controlled, goal-directed movements to more automatic, refined motor actions. Furthermore, this reorganization may help transition motor memory representation from the putamen to adjacent somatosensory regions, reinforcing the automatization of motor skills34,54. While it is tempting to speculate that the pattern of results suggest that SW-SP complexes may be mechanisticlly involved in this transformation, additional repeated measures studies would be required to verify this claim in future studies.

Our findings also shed light on the regionally-specific hemispheric lateralization of memory reactivation, a phenomenon initially identified by Nishida and Walker11. In their study, Nishida and Walker observed that an enhancement in offline motor memory was closely correlated with increased sleep spindle activity, particularly in the motor cortical regions of the hemisphere that was actively engaged during learning. However, this regional specificity remained to be further explored using whole-brain techniques such as fMRI, nor was coupling status investigated at the time. In line with their results, when directly comparing the brain activations time locked to SW-SP complexes in the ipsilateral and contralateral hemisphere to the hand performing the MSL task, only the contralateral activations showed an learning-related increase. Critically, the areas activated in the contralateral hemisphere included the motor cortex, and in particular clusters around the precentral and postcentral regions of the hand knob. Moreover, the motor cortex in the ipsilateral hemisphere showed a decrease in activity following the MSL task in the precentral gyrus and insular cortex. Thus, suggesting that the previous lateralization effect reported by Nishida and Walker could be primarily driven by SW-SP complexes, but also via deactivation of the analogous regions of the contralateral hemisphere.

In addition, to our knowledge, no studies have shown dissociable patterns of brain activation to indicate the functional significance of coupled vs. uncoupled spindles in a single study/dataset. Given that there is accumulating evidence that SW-SP coupling supports memory consolidation, this might beg the question: “then, what are isolated spindles for?” Here, we show higher activation in the motor sensory areas, primary auditory and primary visual cortex time-locked to isolated spindle events when compared to SW-SP complexes. Aside from memory consolidation, one of the complimentary functions of spindles is their role in the maintenance of sleep39–42. However, it is important to note that previous studies did not differentiate and compare coupled and uncoupled spindles. The results of the current study suggest that coupled spindles support memory functions, and uncoupled spindles support sleep maintenance. However, the latter part of this interpretation should be taken with caution, as protocols explicitly designed to test this hypothesis would be better suited to provide more direct evidence.

There are several limitations worth mentioning in the present study. Due to limited sleep duration—an inherent and unavoidable challenge common to all EEG-fMRI investigations of sleep – it was not possible to sub-categorize spindles into slow spindles and fast spindles, nor was it possible to categorize spindles according to NREM2 and SWS due to the limited number of events. We did mitigate this somewhat by including spindles from Pz in the analyses, where fast spindles predominate, which are also most consistently associated with motor memory consolidation55,56. However, further replication of these results would provide additional support for the role of SW-SP complexes in the reactivation and transformation of motor skill memory. Similarly, we cannot rule out the potential presence of K-complexes accompanying slow oscillations during periods of N2 sleep. Another limitation of the current study, due to the more limited number of events inherent in binning spindles into coupled and uncoupled categories was a reduction in statistical power. We were able to mitigate this issue by including data from two complimentary datasets, however, this was not possible for all analyses. In addition to replicating several robust findings from previous studies, we identified significant activation of the putamen related to SW-SP coupling. Although the cluster size was below our rather conservative cutoff for cluster size (K = 30), there is strong a priori justification to include this region in the analyses, despite the cluster size. Finally, correlation analyses between the activity maps time-locked to coupled events and behavioral improvements were conducted. None of the correlations were statistically significant. This was likely due to the limited number of participants, particularly in Dataset 2. The lack of sufficient retest measures in Dataset 1 in the combined dataset may have also contributed to these null findings. However, and importantly, we would like to stress that the SW-spindle coupled activations are difference maps between post-MSL learning and the non-learning control night, providing support that the SW-spindle coupled activations are specific to MSL learning, even in the absence of parametric correlation between the strength of that activation and the magnitude of the offline changes in memory.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that the previous link between sleep spindles and the offline reactivation of key brain regions involved in motor sequence memory performance is dependent on spindle coupling status. SW-SP coupling represents a putative electrophysiological mechanism for the hippocampal-neocortical dialog and transfer of information into long-term storage, via reactivation of brain areas directly involved in motor sequence learning. Remarkably, here we show highly localized regional specificity of spindle-related reactivations in terms of hemisphere and subregions of the motor cortical areas, which are entirely distinct from uncoupled spindles, that by contrast, appear to be actively involved in sleep maintenance. This supports and strengthens the hypothesis that sleep-dependent memory consolidation takes place via the reactivation of brain regions recruited during initial learning in a task-dependent and regionally specific manner that is specific to coupled SW-SP complexes.

Methods

Participants

All participants had normal, consistent sleep schedules, were right-handed, had normal body weight (18.5 < BMI ≤ 25), and no history of psychiatric, neurological disorders, or other conditions like chronic pain, seizures, or head injury. Participants were not eligible to participate if they were smokers, consumed an excess of caffeinated beverages (3-4 caffeinated beverages/day), consumed >7 alcoholic beverages/week, had engaged in shift work or used medications known to affect sleep. Participants did not have extensive training as a typist or musician ( < 1 year of formal training), nor were they experienced video game players. Participants completed the Beck Depression57 and Anxiety Inventories58 as well as the Sleep Disorders Questionnaire59 to exclude participants with signs of depression or anxiety and ensure normal sleep-wake patterns; all participants scored ≤8 on both Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Additionally, participants did not exhibit signs of excessive daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale ≤9)60 and reported normal sleep as per the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI < 5)61. Those categorized as extreme morning or evening types (Horne Ostberg Morningness-Eveningness Scale)62, working night shifts, or having traveled across time zones within three months prior to the experiment were also excluded. Actigraphy and sleep logs confirmed adherence to sleep and activity cycles throughout the study.

As the experiment involved simultaneous EEG-fMRI recordings during sleep, all participants completed a mandatory acclimatization night in a mock scanner, identical to conditions of the actual MR scanner located at the Functional Neuroimaging Unit, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. A minimum of 5 min of consolidated NREM sleep during a 2-h period was required for inclusion in the actual MRI scanning sessions. Participants then continued to sleep in a nearby sleep laboratory until 07h30.

Data for this study was acquired from two separate studies. Dataset 1, included N = 12 participants and included both control and experimental nights (Fogel et al.3 for details). Dataset 2, included N = 19 participants, and included one experimental night (see Boutin et al.43 for details). These sample sizes are consistent with previous EEG-fMRI studies on sleep spindles, slow waves, and memory4,18,27,63, ensuring adequate statistical power for MRI and behavioral analyses. Due to the congruent nature of the study designs in these two datasets, where appropriate and possible, we opted to merge them, resulting in a combined dataset of N = 31 participants. This allowed for certain analyses to be more robust analysis due to the increased sample size.

Ethical and scientific approval for each study was granted for both studies by the Research Ethics Board at the Institut Universitaire de Gériatrie de Montréal (IUGM), and all participants provided informed written consent before participation. All ethical regulations relevant to human research participants were followed.

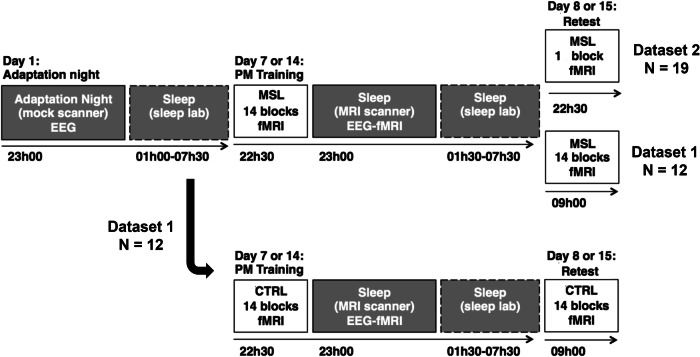

Dataset 1

Experimental design

We assessed the brain activations associated with the consolidation of a newly acquired 5-item motor sequence learning (MSL) task relative to a motor control (CTRL) task in a within-subjects design. These tasks were administered one week apart in a counterbalanced order (1-week after screening/acclimatization, on either day 7 or day 14; Fig. 9). MSL/CTRL training and retest sessions were scheduled at 22 h30 and 09 h00, respectively. Post-training, participants underwent simultaneous EEG-fMRI recordings during sleep inside the MRI scanner, where sleep spindles and slow waves were identified offline following EEG preprocessing and sleep stage scoring. The sleep session was terminated upon reaching the maximum data acquisition limit of the MRI system (Siemens 3.0T TIM TRIO), equivalent to ~2.25 h (i.e., 4000 volumes), or if participants chose to voluntarily end the session prematurely. Following this, EEG equipment was removed, and participants were permitted to continue to sleep in the adjacent sleep laboratory without polysomnographic monitoring. The retest session was conducted in the MRI scanner at 09 h00, ensuring a minimum time of 1.5 h to pass, post-awakening at 07 h30 to allow any residual effects of sleep inertia to dissipate.

Fig. 9.

Common aspects of the experimental design between both datasets. All participants went through an adaptation night in the mock scanner followed by an acclimation night. Twelve of the 31 participants (Dataset 1) completed both an MSL (top row) and CTRL session (bottom row). The remaining 19 participants (Dataset 2) completed the MSL session with just one block of the task at retest.

Motor sequence learning task

In preparation for the fMRI scanning session, participants were first familiarized with the motor sequence learning (MSL) task through a slide show demonstration and detailed instructions provided by the experimenter. The MSL task was a modified version of the sequential finger-tapping paradigm developed by Karni et al.64 coded in Psychtoolbox (http://psychtoolbox.org) and implemented using MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Sherborn, MA). To operate the task, subjects utilized a custom-designed MR-compatible ergonomic response pad equipped with four horizontally aligned buttons. Following these preparatory steps, and before entering the scanner, participants underwent a pre-training phase. During this stage, they were instructed to perform a predetermined 5-item finger movement sequence at a comfortable pace (notated as 4-1-3-2-4, corresponding from the little finger to the index finger) with their non-dominant hand. The goal was to accurately replicate the sequence three times in a row without error. This pre-training phase was conducted without fMRI scanning and was excluded from the analyses. Its purpose was purely instructional, ensuring that subjects could correctly place their hand on the response pad, had a clear understanding of the task requirements, could explicitly recall the sequence of finger movements, and was able to perform the sequence without errors.

For the training portion of the MSL task used in subsequent data analyses, participants were asked to perform the previously memorized 5-item finger sequence as “quickly and accurately as possible” during successive practice blocks. Upon making a mistake, participants were instructed to restart the sequence from the first item to maintain a seamless flow of practice within each block.

The training and follow-up retest sessions included 14 blocks of practice. The start of each block was indicated by the appearance of a green cross on the screen, and terminated by the appearance of a red cross after 60 key presses—equivalent to twelve repetitions of the 5-item sequence. A 15-s rest interval separated each block that was indicated by a red cross, during which participants were instructed to keep their fingers still. Execution of the sequence was self-paced without external cues or any feedback about accuracy. Owing to the sequence’s simplicity and the explicit instruction, participants achieved a very high accuracy rate, with an overall average of 83% or higher, corresponding to at least 10 out of 12 correctly completed sequences per block. The main performance measure of interest was inter-keypress interval (i.e., the time between correct key presses), in line with previous studies13,16,52,65. Also consistent with previous studies, offline gains in performance from the initial training to the retest session was measured and taken as an indicator of offline memory consolidation. This was done by comparing the average speed of the final four practice blocks in the initial session against the first four blocks of the retest session.

Motor performance control task

The twelve participants (Dataset 1) also completed training on a control task in a separate session, on a different night (Fig. 9). The control (CTRL) task employed the identical four-button, magnetic resonance (MR)-safe response box as the MSL task. Unlike the MSL task, the CTRL task involved pressing all four buttons simultaneously at a rhythm matching the average pace of the MSL task (3 Hz ± 0.25 Hz). This design maintained the same motor execution characteristics, such as the number of finger flexions and the average time between presses, but without any sequence learning element. As in the MSL task, the motor movements for the CTRL task were performed using the left hand and were self-paced.

The CTRL task unfolded in two stages, mirroring the MSL task preparations. Before entering the scanner, participants were introduced to the task via a slide show and verbal instructions from the experimenter. The session commenced with a pre-training phase outside the scanner, where subjects synchronized their simultaneous four-key presses to a monotonic 3 Hz auditory tone, indicated by a green cross displayed on screen. This initial pre-training involved three practice blocks, concluding after 60 four-key presses, with 15-s rest periods in between, indicated by a red cross.

This pre-training was designed to accustom participants to the natural 3 Hz tempo typically seen in the MSL task66. The same protocol was repeated for the second part of the pre-training, but without the auditory cues, urging participants to internalize and replicate the learned rhythm. During the rest periods, the performance speed was shown in red text on the screen, offering feedback on their self-initiated pacing. Unbeknownst to the subjects, this part of the pre-training concluded once they consistently hit the target rhythm of 3 Hz (with a margin of ±0.25 Hz) across three blocks. This approach guaranteed that participants could reliably perform simultaneous presses at the predetermined tempo. As with the MSL task, this pre-training was not included in subsequent analyses.

During the CTRL task practice sessions, participants were directed to maintain the rhythm they had established in the pretraining phase and to take a rest during the display of the red cross. Each session consisted of 14 practice blocks, with each block ending after 60 simultaneous four-key presses and was interspersed with 15-s rest intervals. The structure of the CTRL task practice sessions in the evening and the retest sessions the following morning also mirrored that of the MSL task. In alignment with the MSL task procedures, performance on the CTRL was quantified by measuring the inter-response interval; the time between consecutive simultaneous key presses of all four fingers. If the fingers did not press the keys at the same moment, the onset of the first finger press was captured and included in the analysis. This method ensured that the CTRL task was assessed in the same manner as the MSL task.

Dataset 2

Experimental design

The design for Dataset 2 was identical to that of Dataset 1, with a few notable differences (Fig. 9). Dataset 2 included the 5-item motor sequence learning (MSL) task, but did not include a motor control (CTRL) task for comparison. The structure of administering the MSL task, including the training and retest sessions, followed the same within-subjects design as Dataset 1. Both sessions were scheduled one week apart in a counterbalanced order. However, the retest session in Dataset 2 differed by comprising only a single block of practice instead of 14 blocks, and was administered 24 h after the training session. Importantly, the focus of the current study was on the post-learning brain activations during the EEG-fMRI sleep session, and in this regard, Dataset 1 and Dataset 2 were identical in all respects.

Motor Sequence Learning Task

The motor sequence learning task in Dataset 2 was identical to that of Dataset 1. Participants were familiarized with the 5-item finger sequence (notated as 4-1-3-2-4) and utilized the same MR-compatible ergonomic response pad. The pre-training, training, and method of data analysis also remained consistent with Dataset 1.

However, for the retest session in Dataset 2, participants completed just one block of practice 24 h after the training session. As in Dataset 1, the main performance measure was the inter-keypress interval. Offline gains were evaluated by comparing the average speed of the final four practice blocks in the training session against the only block of the retest session. Given the procedural differences from Datatset 1, the behavioral data from Dataset 2 were collected and analyzed but are not presented here.

Statistics and reproducibility

Polysomnographic Acquisition and Analysis (Datasets 1 and 2).

Polysomnographic recording parameters

A 64-channel magnetic resonance (MR) compatible EEG cap, including an integrated electrocardiogram (ECG) lead (Braincap MR, Easycap), was used to capture polysomnographic (PSG) data in the MRI scanner. This setup used dual MR-compatible 32-channel amplifiers (Brainamp MR Plus, Brain Products GmbH) for a total of 64 EEG channels. The EEG signals were referenced to FCz, with a digitization rate of 5000 samples per second and a resolution of 500-nv. To enhance the visibility of the r-peak within the QRS complex, for optimal offline ballistocardiographic (BCG) artifact correction, three additional bipolar ECG channels were recorded using another MR-compatible amplifier (Brainamp ExG MR, Brain Products GmbH). We adjusted participant placement in the MRI scanner so that they were shifted away from the isocenter of the magnetic field by 40 mm to minimize the BCG artifacts by an estimated 40%67. These steps improve the subsequent BCG correction process. Analog filtering of the data was performed utilizing a 500 Hz low-pass filter to limit the bandwidth and a 0.0159 Hz high-pass filter with a 10-s time constant. Data was recorded with Brain Products Recorder Software, Version 1.x and transferred to the recording computer via fiber-optic cable and hardware synchronized to the scanner clock using the Brain Products “Sync Box” (Brain Products GmbH). Conforming to best practices suggested in the literature68, MRI sequence parameters were selected to ensure time stability of the gradient artifact, and that the lowest harmonic of this artifact (18.52 Hz) would occur above the spindle frequency band (11–16 Hz). Consequently, the optimal MR scan repetition time was set to 2160 ms.

EEG preprocessing

Artifacts in the EEG recordings were removed through a well-established multi-step process. First, an adaptive average template subtraction technique69 implemented in Brain Products Analyzer Software, Version 2.x was used to remove gradient artifacts on the EEG, and data was downsampled to 250 Hz.

Then, the r-peaks from the ECG traces were identified through a semi-automated process. Each r-peak was visually inspected, and the timing manually corrected if necessary. When necessary, both false-positive and false-negative r-peak detections were corrected, thus enhancing the precision of the subsequent BCG artifact correction. Following this, adaptive template subtraction70 was used to remove BCG artifacts that were synchronized with the r-peak within the QRS complex. After MRI-related artifact correction, the data was subjected to a thorough visual examination. Any recordings with residual artifacts exceeding 3 μV during the QRS complex interval (e.g., 0–600 ms) were corrected using independent component analysis (ICA)71,72 to subtract out the residual BCG artifacts.

Lastly, the EEG was re-referenced to the averaged mastoids and a low-pass filter of 60 Hz was applied. Following preprocessing, sleep stages were scored by an expert polysomnographic technologist following established guidelines73. The classification was performed using the EEGLAB-compatible74 Counting Sheep PSG toolbox (https://github.com/stuartfogel/CountingSheepPSG)75. The sleep architecture is reported in Supplementary Table 1.

Slow wave detection

Slow waves were automatically detected from Fz, Cz, Pz, C3, and C4 during movement artifact-free NREM sleep (N2 and SWS) via a period amplitude analysis detection algorithm (https://github.com/stuartfogel/Period-Amplitude-Analysis) based on established methods76, adapted for EEGLAB74 and written for MATLAB R2019b (The MathWorks Inc.). First, the EEG signal was band-pass filtered (32nd-order Chebyshev Type 2 low-pass filter, 80 dB stopband attenuation, 2.15 Hz frequency cut-off; 64th-order Chebyshev type 2 high-pass filter, 80 dB stopband attenuation, 0.46 Hz frequency cut-off). The cut-off frequencies were selected to achieve minimal attenuation in the band of interest (0.5-2.0 Hz) while keeping a good attenuation of the neighboring frequencies. The filters were applied in the forward and reverse directions to achieve zero-phase distortion. Next, half-waves were determined as negative or positive deflections between two consecutive zero crossings in the band-pass filtered signal for frequencies between 0.5 and 2 Hz. Only adjacent half-waves with a peak-to-peak amplitude higher than 75 μV and longer than 0.25 s were considered for the analysis. The latency of the negative peak of each slow wave was extracted for further analyses.

Spindle detection

Sleep spindles were also automatically detected from Fz, Cz, Pz, C3 and C4 during movement artifact-free NREM sleep (N2 and SWS) using an established22,34,38,53 and validated77 method employing EEGlab-compatible74 software (https://github.com/stuartfogel/detect_spindles) written for MATLAB R2019b (The MathWorks Inc.). Detailed processing steps, procedures, and method validation are reported elsewhere77. Briefly, the spindle data were extracted from movement artifact-free, NREM epochs. The detection method77 used a complex demodulation transformation of the EEG signal with a bandwidth of 5 Hz centered about a carrier frequency of 13.5 Hz (i.e., 11–16 Hz). The method employs an adaptive amplitude threshold at the 99th percentile on the transformed signal. Spindles were visually verified by a single expert scorer after automatic detection. The variables of interest extracted from this method include spindle integrated amplitude, duration, and density (number of spindles/min of NREM sleep) for each participant. From the spindle data, the onset and peak of each spindle event was extracted for further analyses.

Slow wave-spindle coupling

Using the slow wave negative peak latencies and the spindle peak latencies from Fz, Cz, Pz, C3, and C4, we performed coupling detection procedures using the approach developed by Mölle and colleagues78 and adapted by our group33,35 employing EEGLAB-compatible74 software written for MATLAB R2019b (The MathWorks Inc.). The spindles were marked as coupled SW-SP complexes when the spindle peak onset occurred within a 4-s time window (to encompass 1 full cycle of a 0.5 Hz slow wave about a spindle event) built around the slow wave negative peak. Due to data limitations, it was not possible to further subdivide events into slow and fast spindle subcategories. However, we selected Pz a priori as the site of interest used in subsequent fMRI analyses, as this is where fast spindles are maximal on the scalp, and fast spindles are most-often associated with offline memory consolidation12,14,78. In addition, C3 and C4 were selected a priori for the fMRI analyses to investigate regionally-specific interhemispheric differences. Lag was measured as the distance between the slow wave negative peak and the spindle peak latency. Coupling strength was measured as the mean vector length (MVL) for each participant. Paired sampled t-tests were used for the comparison of the SW-SP complexes, measured in time bins of 200 ms along the 4 s window. Percentage of coupled spindles relative to total number of spindles was calculated.

Additionally, the phase of the bandpass-filtered slow-wave signal in radians at the spindle onset location was computed. The mean direction of the phase angles for all coupled spindle events were determined using the CircStat toolbox79. Preferred phase of SW-SP coupling for each participant was computed by averaging all individual event preferred phases. Finally, we performed uniformity tests (Rayleigh test) and uniformity using positive slow wave peaks as the predefined mean direction (V-test).

MRI acquisition and analysis (Datasets 1 and 2)

fMRI data acquisition

Functional MRI series were acquired using a 3.0 T TIM TRIO MR system (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany), equipped with a 12-channel head coil. Specifically, we obtained T2*-weighted images with a gradient echo-planar sequence using interleaved acquisition mode in ascending direction with complete cortical and cerebellum coverage (40 axial slices, TR = 2160 ms, TE = 30 ms, FA = 90°, FoV = 220 × 220 × 132 mm, matrix size = 64 × 64 × 43, voxel size = 3.44 × 3.44 × 3.0 mm, GRAPPA = 2, 10% inter-slice gap). In addition, we obtained structural whole-brain T1-weighted images employing a rapid gradient-echo (MPRAGE) protocol (TR = 2530 ms, TE = 1.64, 3.6, 5.36, 7.22 ms, TI = 1200 ms, FA = 7°, FoV= 256 × 256 × 176 mm, voxel size =1 × 1 × 1 mm).

fMRI data preprocessing

Preprocessing and statistical analysis of the data were carried out with SPM12 (http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/; Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging, London, UK) for MATLAB (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). All the images were converted to Neuroimaging Informatics Technology Initiative (NIfTI) format. Structural images were then segmented using diffeomorphic anatomical registration through exponential lie algebra (DARTEL) procedure80 and skull stripped. Functional images were realigned using a least squares approach with a six-parameter (rigid body) spatial transformation, correcting for movement-related variance. They were then aligned to structural images and transformed into Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using the parameters obtained from the segmentation procedure. The normalized functional images were subsequently resampled to voxel dimensions of 3 mm3 and underwent spatial smoothing using an isotropic Gaussian kernel with a full-width at half-maximum of 6 mm.

fMRI data analysis

Our primary focus was on the imaging data acquired during sleep after the initial training on the motor sequence learning (MSL) task, or, in the case of Dataset 1, in comparison to sleep after performing the control (CTRL) task. Only volumes corresponding to motion-free epochs during NREM2 and SWS sleep were included in the analysis. The fMRI time series were subjected to statistical analyses using a two-stage statistical approach81, described here.

First-level analyses

BOLD signal changes associated with sleep events (isolated spindles and SW-SP events) were estimated for each participant, each night (post-MSL and post-CTRL) and each EEG channel of interest (Pz, C4, and C3) independently using a fixed-effect general linear modeling (GLM). Volumes corresponding to each uninterrupted period of NREM sleep (NREM2 and/or SWS) were entered into the model as a separate session. Activity changes related to slow waves and spindles were assessed using an event-related design. Each individual statistical model modeled coupled and uncoupled slow waves (aligned to negative peaks) or coupled and uncoupled spindles (aligned to onsets) represented as stick functions (zero duration). The stick function is particularly suitable for capturing neural changes time-locked to discrete events and is less influenced by variations in activity due to differences in event duration82. Therefore, this approach enabled us to assess changes in neural activity associated with coupled and uncoupled events (either slow waves or spindles) while minimizing potential biases arising from the inherent variability in their length. All covariates were convolved with a hemodynamic response function (HRF).

The nuisance regressors included in the model comprised six movement parameters derived from the realignment procedure. Additionally, we employed the component-based method (CompCor)81 implemented in Translational Algorithms for Psychiatry-Advancing Science (TAPAS) software package83 (code available on https://www.translationalneuromodeling.org/tapas) to extract the first five components from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). These CSF components were also incorporated in the model to mitigate the effects of physiological noise. To account for low-frequency noise, a high-pass filter with a cut-off of 128 s was applied. Serial correlations in the fMRI signal were estimated using a restricted maximum likelihood (ReML) algorithm, employing a first-order autoregressive plus white noise model.

We utilized linear contrasts to examine the main effects of each type of events (i.e., SW-SP complexes, uncoupled slow waves and uncoupled spindles) and the distinction between them to obtain statistical maps (t-maps) representing the observed differences in brain activity.

Second-level analyses

The resulting t-maps from the first-level analyses were carried forward to the random effects analyses to assess the consistency of effects across participants (group-level analyses). The inferences were done for each contrast image using a one-sample t-test. Differences in the activation patterns between slow waves and spindles within and across experimental nights were assessed using one-way repeated measure analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Visualization and statistical inferences were performed using the Nilearn toolbox—a Python package for visualization and statistical learning techniques applied to neuroimaging data84. Activation maps were overlaid on the mean structural image of all participants oriented according to the neurological convention (i.e., the left side of the image corresponds to the left side of the brain). Statistical inferences were performed using a two-step inference procedure that comprised voxel-level thresholding (p < 0.005, two-sided tests), followed by cluster-extent-based inference while controlling the family-wise error rate (FWE) over the entire brain. Inferences within the above-mentioned predefined regions of interest were performed using small volume correction. Clusters of brain activation were labeled according to anatomical automatic labeling85. Parameter estimates and contrast values of parameter estimates were extracted from sphered ROIs centered at the local maxima of thresholded maps resulting from group-level analyses using MarsBar toolbox for SPM86. When appropriate, the extracted values were subjected to further statistical analysis using the statsmodels package written in Python87 with small volume correction applied.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary File

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grants (PJT 173533 to J.D.). The Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) Discovery grant (RGPIN/2017–04328 to S.F.).

Author contributions

D.B.: Manuscript writing, EEG signal processing and analysis, behavioral analysis, figure composition. E.G.: Manuscript writing, MRI signal processing and analysis, data acquisition, figure composition. L.R.: Sleep scoring, EEG data quality assurance. J.D.: Study conceptualization and design, manuscript writing supervision. S.F.: Study conceptualization and design, manuscript writing supervision, data acquisition. First authorship is equally shared between D.B. and E.G. Senior authorship is equally shared between J.D. and S.F.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Makoto Uji and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Jasmine Pan. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Reasonable requests to access the related data will be considered on a case-by-case basis and should be made to the corresponding author. Ethical approval for data sharing agreements is required to share data, in order to protect participant confidentiality. The behavioral data from the motor sequence learning task are included as supplementary data.

Code availability

Code or batch functions used in these analyses are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Several toolkits are available in open-source for download at: https://github.com/stuartfogel.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Daniel Baena, Ella Gabitov.

These authors jointly supervised this work: Julien Doyon, Stuart M. Fogel.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-024-07197-z.

References

- 1.Frankland, P. W. & Bontempi, B. The organization of recent and remote memories. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.6, 119–130 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diekelmann, S. & Born, J. The memory function of sleep. Nat. Rev. Neurosci.11, 114–126 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fogel, S. et al. Reactivation or transformation? Motor memory consolidation associated with cerebral activation time-locked to sleep spindles. PLOS ONE12, e0174755 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jegou, A. et al. Cortical reactivations during sleep spindles following declarative learning. NeuroImage195, 104–112 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamminen, J., Payne, J. D., Stickgold, R., Wamsley, E. J. & Gaskell, M. G. Sleep spindle activity is associated with the integration of new memories and existing knowledge. J. Neurosci. J. Soc. Neurosci.30, 14356–14360 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Debas, K. et al. Off-line consolidation of motor sequence learning results in greater integration within a cortico-striatal functional network. Neuroimage99, 50–58 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ngo, H. V. & Staresina, B. P. Shifting memories. eLife6, e30774 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Vahdat, S., Fogel, S., Benali, H. & Doyon, J. Network-wide reorganization of procedural memory during NREM sleep revealed by fMRI. eLife6, e24987 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Noack, H., Doeller, C. F. & Born, J. Sleep strengthens integration of spatial memory systems. Learn. Mem. Cold Spring Harb. N.28, 162–170 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fogel, S. M. & Smith, C. T. Learning-dependent changes in sleep spindles and Stage 2 sleep. J. Sleep Res.15, 250–255 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishida, M. & Walker, M. P. Daytime naps, motor memory consolidation and regionally specific sleep spindles. PLoS ONE2, e341 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morin, A. et al. Motor sequence learning increases sleep spindles and fast frequencies in post-training sleep. Sleep31, 1149–1156 (2008). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doyon, J. et al. Contribution of night and day sleep vs. simple passage of time to the consolidation of motor sequence and visuomotor adaptation learning. Exp. Brain Res.195, 15–26 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barakat, M. et al. Fast and slow spindle involvement in the consolidation of a new motor sequence. Behav. Brain Res.217, 117–121 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barakat, M. et al. Sleep spindles predict neural and behavioral changes in motor sequence consolidation. Hum. Brain Mapp.34, 2918–2928 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fogel, S. M. et al. fMRI and sleep correlates of the age‐related impairment in motor memory consolidation. Hum. Brain Mapp.35, 3625–3645 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laufs, H., Walker, M. C. & Lund, T. E. ’ Brain activation and hypothalamic functional connectivity during human non-rapid eye movement sleep: An EEG/fMRI study’-its limitations and an alternative approach. Brain J. Neurol.130, e75–e75 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schabus, M. et al. Hemodynamic cerebral correlates of sleep spindles during human non-rapid eye movement sleep. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.104, 13164–13169 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyvaert, L., LeVan, P., Grova, C., Dubeau, F. & Gotman, J. Effects of fluctuating physiological rhythms during prolonged EEG-fMRI studies. Clin. Neurophysiol.119, 2762–2774 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrade, K. C. et al. Sleep spindles and hippocampal functional connectivity in human NREM sleep. J. Neurosci.31, 10331–10339 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caporro, M. et al. Functional MRI of sleep spindles and K-complexes. Clin. Neurophysiol.123, 303–309 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fang, Z., Ray, L. B. B., Owen, A. M. M. & Fogel, S. M. Brain activation time-locked to sleep spindles associated with human cognitive abilities. Front. Neurosci.13, 46 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaufmann, C. et al. Brain activation and hypothalamic functional connectivity during human non-rapid eye movement sleep: an EEG/fMRI study. Brain129, 655–667 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fang, Z. et al. Sleep spindle-dependent functional connectivity correlates with cognitive abilities. J. Cogn. Neurosci.32, 446–466 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrade, K. C. et al. Behavioral/systems/cognitive sleep spindles and hippocampal functional connectivity in human NREM sleep. J. Neurosci.31, 10331–10339 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fogel, S. M. et al. Sleep spindles: a physiological marker of age-related changes in grey matter in brain regions supporting motor skill memory consolidation. Neurobiol. Aging49, 154–164 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bergmann, T. O., Mölle, M., Diedrichs, J., Born, J. & Siebner, H. R. Sleep spindle-related reactivation of category-specific cortical regions after learning face-scene associations. NeuroImage59, 2733–2742 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helfrich, R. F. et al. Bidirectional prefrontal-hippocampal dynamics organize information transfer during sleep in humans. Nat. Commun.10, 3572 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bergmann, T. O. & Born, J. Phase-amplitude coupling: a general mechanism for memory processing and synaptic plasticity? Neuron97, 10–13 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Helfrich, R. F., Mander, B. A., Jagust, W. J., Knight, R. T. & Walker, M. Old brains come uncoupled in sleep: Slow wave-spindle synchrony, brain atrophy, and forgetting. Neuron97, 221–230 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maingret, N., Girardeau, G., Todorova, R., Goutierre, M. & Zugaro, M. Hippocampo-cortical coupling mediates memory consolidation during sleep. Nat. Neurosci.19, 959–966 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ngo, H. V. et al. Sleep spindles mediate hippocampal-neocortical coupling during long-duration ripples. eLife9, 1–18 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baena, D. et al. Functional differences in cerebral activation between slow wave-coupled and uncoupled sleep spindles. Front. Neurosci.16, 1090045 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang, Z. et al. Sleep spindles and intellectual ability: epiphenomenon or directly related? J. Cogn. Neurosci.29, 167–182 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baena, D., Fang, Z., Ray, L. B., Owen, A. M. & Fogel, S. Brain activations time locked to slow wave-coupled sleep spindles correlates with intellectual abilities. Cereb. Cortex33, 5409–5419 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doyon, J. et al. Contributions of the basal ganglia and functionally related brain structures to motor learning. Behav. Brain Res.199, 61–75 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doyon, J., Gabitov, E., Vahdat, S., Lungu, O. & Boutin, A. Current issues related to motor sequence learning in humans. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci.20, 89–97 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fogel, S. M. et al. Motor memory consolidation depends upon reactivation driven by the action of sleep spindles. J. Sleep. Res.23, 47 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jankel, W. R. & Niedermeyer, E. Sleep spindles. J. Clin. Neurophysiol.2, 1–35 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Steriade, M., McCormick, D. A. & Sejnowski, T. J. Thalamocortical oscillations in the sleeping and aroused brain. Science262, 679 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dang-Vu, T. T., McKinney, S. M., Buxton, O. M., Solet, J. M. & Ellenbogen, J. M. Spontaneous brain rhythms predict sleep stability in the face of noise. Curr. Biol.20, R626–R627 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thanh Dang-Vu, T. et al. Human neuroscience sleep spindles predict stress-related increases in sleep disturbances. 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00068 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Boutin, A. et al. Temporal cluster-based organization of sleep spindles underlies motor memory consolidation. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci.291, 20231408 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gais, S., Mölle, M., Helms, K. & Born, J. Learning-dependent increases in sleep spindle density. J. Neurosci.22, 6830–6834 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fogel, S. M., Smith, C. T. & Cote, K. A. Dissociable learning-dependent changes in REM and non-REM sleep in declarative and procedural memory systems. Behav. Brain Res.180, 48–61 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peters, K. R., Ray, L. B., Smith, V. & Smith, C. T. Changes in the density of stage 2 sleep spindles following motor learning in young and older adults. J. Sleep. Res.17, 23–33 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Astill, R. G. et al. Sleep spindle and slow wave frequency reflect motor skill performance in primary school-age children. Front. Hum. Neurosci.8, 910 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boutin, A. et al. Transient synchronization of hippocampo-striato-thalamo-cortical networks during sleep spindle oscillations induces motor memory consolidation. NeuroImage169, 419–430 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walker, M., Stickgold, R., Alsop, D., Gaab, N. & Schlaug, G. Sleep-dependent motor memory plasticity in the human brain. Neuroscience133, 911–917 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Albouy, G. et al. Both the hippocampus and striatum are involved in consolidation of motor sequence memory. Neuron58, 261–272 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albouy, G., King, B. R., Maquet, P. & Doyon, J. Hippocampus and striatum: dynamics and interaction during acquisition and sleep-related motor sequence memory consolidation. Hippocampus23, 985–1004 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Debas, K. et al. Brain plasticity related to the consolidation of motor sequence learning and motor adaptation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA107, 17839–17844 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Albouy, G. et al. Maintaining vs. enhancing motor sequence memories: respective roles of striatal and hippocampal systems. NeuroImage108, 423–434 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Doyon, J., Penhune, V. B. & Ungerleider, L. G. Distinct contribution of the cortico-striatal and cortico-cerebellar systems to motor skill learning. Neuropsychologia41, 252–262 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Laventure, S. et al. NREM2 and sleep spindles are instrumental to the consolidation of motor sequence memories. PLOS Biol.14, e1002429 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Solano, A., Riquelme, L. A., Perez-Chada, D. & Della-Maggiore, V. Motor learning promotes the coupling between fast spindles and slow oscillations locally over the contralateral motor network. Cereb. Cortex32, 2493–2507 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A. & Carbin, M. G. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin. Psychol. Rev.8, 77–100 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G. & Steer, R. A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J. Consult Clin. Psychol.56, 893–897 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Douglass, A. B. et al. The Sleep Disorders Questionnaire. I: creation and multivariate structure of SDQ. Sleep17, 160 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Johns, M. W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep14, 540–545 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R. & Kupfer, D. J. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res.28, 193–213 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Horne, J. A. & Ostberg, O. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int. J. Chronobiol.4, 97–110 (1976). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dang-Vu, T. T. et al. Spontaneous neural activity during human slow wave sleep. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.105, 15160 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Karni, A. et al. Functional MRI evidence for adult motor cortex plasticity during motor skill learning. Nature377, 155–158 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kuriyama, K., Stickgold, R. & Walker, M. P. Sleep-dependent learning and motor-skill complexity. Learn. Mem.11, 705–713 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Orban, P. et al. The multifaceted nature of the relationship between performance and brain activity in motor sequence learning. Neuroimage49, 694–702 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mullinger, K. J., Yan, W. X. & Bowtell, R. Reducing the gradient artefact in simultaneous EEG-fMRI by adjusting the subject’s axial position. NeuroImage54, 1942–1950 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mulert, C. & Lemieux, L. EEG-fMRI: Physiological Basis, Technique and Applications (Springer, 2010).

- 69.Allen, P. J., Josephs, O. & Turner, R. A method for removing imaging artifact from continuous EEG recorded during functional MRI. Neuroimage12, 230–239 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Allen, P. J., Polizzi, G., Krakow, K., Fish, D. R. & Lemieux, L. Identification of EEG events in the MR scanner: the problem of pulse artifact and a method for its subtraction. NeuroImage8, 229–239 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Srivastava, G., Crottaz-Herbette, S., Lau, K. M., Glover, G. H. & Menon, V. ICA-based procedures for removing ballistocardiogram artifacts from EEG data acquired in the MRI scanner. NeuroImage24, 50–60 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mantini, D. et al. Complete artifact removal for EEG recorded during continuous fMRI using independent component analysis. Neuroimage34, 598–607 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iber, C., Ancoli-Israel, S., Chesson, A. L. & Quan, S. F. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications (American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007).

- 74.Delorme, A. & Makeig, S. EEGLAB: An open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J. Neurosci. Methods134, 9–21 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ray, L. B., Baena, D. & Fogel, S. M. “Counting sheep PSG”: EEGLAB-compatible open-source matlab software for signal processing, visualization, event marking and staging of polysomnographic data. J. Neurosci. Methods407, 110162 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bersagliere, A. & Achermann, P. Slow oscillations in human non-rapid eye movement sleep electroencephalogram: effects of increased sleep pressure. J. Sleep. Res.19, 228–237 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ray, L. B. et al. Expert and crowd-sourced validation of an individualized sleep spindle detection method employing complex demodulation and individualized normalization. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 9, 507 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Mölle, M., Bergmann, T. O., Marshall, L. & Born, J. Fast and slow spindles during the sleep slow oscillation: disparate coalescence and engagement in memory processing. Sleep34, 1411–1421 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Berens, P. CircStat: a MATLAB toolbox for circular statistics. J. Stat. Softw.31, 1–21 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ashburner, J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. NeuroImage38, 95–113 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Friston, K., Josephs, O., Rees, G. & Turner, R. Nonlinear event-related responses in fMRI. Magn. Reson. Med.39, 41–52 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Grinband, J., Wager, T. D., Lindquist, M., Ferrera, V. P. & Hirsch, J. Detection of time-varying signals in event-related fMRI designs. NeuroImage43, 509–520 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Frässle, S. et al. TAPAS: an open-source software package for translational neuromodeling and computational psychiatry. Front. Psychiatry12, 680811 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Abraham, A. et al. Machine learning for neuroimaging with scikit-learn. Front. Neuroinform.8, 71792 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Tzourio-Mazoyer, N. et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. NeuroImage15, 273–289 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brett, M., Anton, J., Valabrègue, R. & Poline, J. B. Region of interest analysis using an SPM toolbox. Presented at the 8th International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain, June 2–6, 2002, Sendai, Japan. Available on CD-ROM in NeuroImage, Vol 16, No 2, abstract 497 (2010).

- 87.Seabold, S. & Perktold, J. Statsmodels: Econometric and Statistical Modeling with Python. In: Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SCIPY 2010) 92–96 (2010). 10.25080/Majora-92bf1922-011.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary File

Data Availability Statement

Reasonable requests to access the related data will be considered on a case-by-case basis and should be made to the corresponding author. Ethical approval for data sharing agreements is required to share data, in order to protect participant confidentiality. The behavioral data from the motor sequence learning task are included as supplementary data.

Code or batch functions used in these analyses are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Several toolkits are available in open-source for download at: https://github.com/stuartfogel.