Abstract

The traditional approach of open-sun drying is facing contemporary challenges arising from the widespread adoption of energy-intensive methods and the quality of drying. In response, solar dryers have emerged as a sustainable alternative, utilizing solar thermal energy to effectively dehydrate vegetables. This study investigates the performance of a single-basin, double-slope solar dryer utilizing natural convection for drying bottle gourds and tomatoes, presenting a sustainable alternative to traditional open-sun drying. The solar dryer exhibited superior moisture removal efficiency, achieving a 94.42% reduction in tomatoes and 83.87% in bottle gourds, compared to open-sun drying. Drying rates were significantly enhanced, with maximum air and plate temperatures reaching 54.42 °C and 63.38 °C, respectively, accelerating the dehydration process. Moisture diffusivity analysis revealed a marked improvement in drying behavior under solar drying, with values ranging from 3.12 × 10−11 to 4.31 × 10−11 m2/s for bottle gourds, and 4.65 × 10−11 to 2.31 × 10−11 m2/s for tomatoes. Energy efficiency assessments highlighted the solar dryer’s advantage, with exergy efficiency peaking at 61.78% for bottle gourds and 68.5% for tomatoes. Furthermore, the activation energy required for drying was significantly lower in the solar dryer (29.14–46.41 kJ/mol for bottle gourds and 27.16–55.42 kJ/mol for tomatoes) compared to open-sun drying, enhancing energy conservation. Visual inspections confirmed the superior quality of the solar-dried vegetables, free from dust and impurities. An economic analysis underscored the system’s viability, with payback periods of 2 years for bottle gourds and 1.6 years for tomatoes. Overall, this study demonstrates the efficacy of solar dryers in optimizing vegetable preservation while promoting energy efficiency, aligning with global sustainability goals by reducing post-harvest losses and supporting eco-friendly practices.

Keywords: Double slope solar dryer; Natural convection; Vegetable drying; Moisture content; Economic analysis, thermal expansion

Subject terms: Chemistry, Energy science and technology, Engineering

Introduction

Traditionally, food items have been preserved by drying or removing moisture using solar energy1–3. Despite its widespread use, the traditional method of drying vegetables depends on the kind of vegetables being dried and the local climate4–6. A wide range of designs are currently under development, and numerous studies have examined ways to increase the moisture removal rate of solar dryers hence increasing their efficacy7–9. This initiative encompasses improvements in design, enhanced efficiency, and a more comprehensive comprehension of the dehydrating process. Consequently, the field of solar drying continues to develop and contribute to the invention of sustainable food preservation methods10,11.

In this regard, Ekechukwu et al. carried out an exhaustive investigation into the myriad of solar dryer designs that are currently available. This comprehensive review sheds light on the various approaches and procedures that have been put into place to make efficient use of solar energy for drying purposes12. Theoretical modelling and practical implementation have been the focus of the researchers’ significant efforts13–15. It is important to note that a mathematical model was created to clarify the mechanisms responsible for solar drying in a cabinet dryer under forced convection conditions. This model offers a comprehensive understanding of the complex processes that are involved in solar drying16,17.

Additionally, practical applications of solar collectors for drying have been examined. The efficacy of a solar collector with a vertical chimney for paddy drying was observed in a study. The results indicated that a 1 m2 collector area desiccated 20 kg of paddy with a grain depth of 7 cm in 9 h, resulting in a moisture content reduction from 31 to 13% on a dry basis18. Additionally, performance comparisons have been implemented to evaluate numerous components of solar dryers. A comparison of the thermal efficiency of semi-cylindrical solar tunnel dryers based on forced convection and natural convection was performed. This investigation underscored the critical role that collector tilt plays in the organization of natural circulation flow and, as a result, the efficacy of the system19. The significance of design factors in optimizing solar drying systems is highlighted by these results.

Research into the thermal behaviour of agricultural products during solar drying has primarily focused on this topic. Researchers observed the thermodynamics of sun-dried cabbage and lentils using two different methods: open sun drying and solar drying with a combination of natural and forced convection. By combining mathematical simulations with experimental results, this investigation increased the reliability of its conclusions20. The researchers set out to make a portable solar dryer with multiple shelves for farmers. Providing options for drying crops on-site and improving the efficiency of crop preservation were the goals of this idea. The stagnation temperature was used to measure the system’s performance, which highlights its operational capabilities and potential benefits for agricultural practitioners21. In addition, the research looked at forced convection solar dryers with desiccants. Empirical research examining its application across diverse agricultural products showcased this unique methodology22. This extensive examination emphasized the complex characteristics of solar drying processes and their importance in preserving crops and optimizing resources. Eltief et al.23 conducted a study on a V-groove forced convective solar dryer to assess its drying chamber efficiency and quantify the heat losses from the chamber. Gbaha et al.24 experimented to study the thermal characteristics of a direct sun drier that utilizes natural convection for drying various foods, including cassava, bananas, and mangoes. The thermal performance was assessed by evaluating elements such as incident radiation, drying air mass flow, and overall system effectiveness. Shanmugam and Natarajan25 conducted a study on a regenerative desiccant-integrated solar dryer, examining its performance both with and without the use of a reflective mirror. Their study, which entailed dehydrating 20 kg of green peas and pineapple slices, demonstrated that the incorporation of the mirror considerably accelerated the process of desiccant regeneration.

Sreekumar et al.26 assessed the effectiveness of an indirect solar cabinet drier for the dehydration of fruits and vegetables. The researchers discovered that 4 kg of bitter gourd reached a moisture content of 5% after 6 h without any alteration in colour, in contrast to the 11 h required for open sun drying. Sethi and Arora27 investigated the improvement of greenhouse sun drying by utilizing inclined north wall reflection in both natural and forced convection modes. This led to time reductions of 13.13% and 16.67%, respectively. Amer et al.28 evaluated the functionality of a hybrid dryer developed for the exclusive purpose of banana drying. The components of this system included a drying chamber, heat exchanger, reflector, heat storage unit, and solar collector. Thirty kilogrammes of banana slices reduced their moisture content from 82 to 18% (wb) in just 8 h, according to their results. On the other hand, open sun drying was only successful in reducing the moisture content to 62%. (wb). Montero et al.29 developed a prototype of a solar dryer that could work in several different ways, including indirect, mixed, passive, active, and hybrid. They did this to study how quickly agro-industrial waste can dry. According to the researchers, drying olive pomace is more effective when put through hybrid and mixed modes. In their study, Bal et al.30 researched agricultural product drying systems that use solar energy and phase change material (PCM). Slama and Combarnous31 studied the rate of drying of orange peels using a solar dryer with forced convection. The drying rate is influenced by variables like air velocity, temperature, and the drying rate itself, according to their study. Maiti et al.32 investigated the effectiveness of a solar dryer that uses indirect natural convection in a batch-type configuration. The papad was dried in the dryer, which had north-south reflectors installed. Gupta et al.33 assessed the efficiency of a solar dryer that dried tomatoes using a solar air heater. They compared the efficiency of natural and forced convection methods. Singh and Kumar34 established convective heat transfer correlations for conventional solar dryer systems, considering both natural and forced convection. Kushwah et al.35 investigated the drying characteristics of mushrooms and the effectiveness of a solar dryer. They achieved an impressive R2 value of 0.99 using artificial neural networks (ANN) to predict drying behaviour. Singh and Kumar provided a generalized drying characteristics curve that is based on experimental data. This curve relates the moisture content ratio to the drying time. Additionally, they introduced the “dryer performance index” (DPI) as a metric to quantify the efficiency of the dryer36. Şevik37 studied the effectiveness of a double-pass solar collector dryer that used PID control to maintain a constant drying air temperature while drying carrot slices. The carrot slices were dried in 220 min according to the experiment. Mustayen et al.38 performed an extensive evaluation of commonly utilized solar dryers. Chan et al.39 conducted a study on a recirculation-type integrated collector drying chamber solar dryer to examine and analyze its effectiveness in drying two different samples of rough rice. The system, comprising a feed hopper, centrifugal blower, pneumatic conveyor, and transparent drying chamber, demonstrated efficiency values of 22.4% and 31.7% for the respective samples. Dhanushkodi et al.40 investigated the drying characteristics of cashew nuts by employing a solar biomass hybrid drier and used different empirical drying models. Castillo-Téllez et al.41 provided a comprehensive explanation of the dehydration procedure for red chilli utilizing an indirect-type forced convection solar dryer. In contrast, Nabnean et al.42 assessed a novel sun dryer design specifically for osmotically dehydrated cherry tomatoes. Chauhan and Kumar43 conducted a heat transfer analysis on a greenhouse dryer with insulation on its north wall. The analysis included both scenarios with and without a solar air heating collector. Sekyere et al.44 conducted an experimental study on the drying properties of recently processed pineapple slices. They used a solar crop dryer with mixed-mode natural convection and a backup heater. Kumar et al.45 conducted a thorough examination of several sun dryers, including direct, indirect, and hybrid types, and their uses in drying processes. Tiwari et al.46 provided valuable information on the latest advancements and patterns in greenhouse dryer technology. Kabeel and Abdelgaied47 conducted a numerical analysis of the thermal efficiency of a solar dryer that was fitted with a rotational desiccant wheel. They observed a substantial enhancement in the amount of useful heat gained compared to a dryer that did not have this feature.

Tuncer et al.48 designed, analyzed, and tested a novel solar drying system featuring a modified photovoltaic-thermal (PVT) collector. The modified collector, with a grooved absorber, spherical turbulators, and baffle configurations, achieved a 15.77% higher outlet temperature than the standard collector. The hybrid system’s thermal and exergy efficiencies ranged from 61.32 to 77.49% and 10.65–11.17%, respectively, while the drying chamber’s exergy efficiency ranged from 59.16 to 68.31%. Sustainability index values for the collector and chamber were 1.12–1.14 and 3.74–5.82, respectively, with a payback period of 2.98–3.51 years. Kaur et al.49 compared drying methods for coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) using solar and open sun drying. Pre-treated coriander was dried with PAU advanced domestic solar dryer (ADSD), PAU domestic solar dryer, and open sun drying. The ADSD exhibited the highest thermal efficiency (18.56%) and the lowest solar energy input (12.56 MJ/kg) while preserving superior quality with maximum flavonoid (1.23 mg/100 g), chlorophyll (24.14 mg/100 g), and ascorbic acid content (24.29 mg/100 g). Singh et al.50 developed an advanced active-mode indirect solar dryer using a high-efficiency evacuated tube collector and DC fan, achieving thermal efficiencies of 34.1% and 23.6% for fenugreek and turmeric, respectively. Compared to open sun drying, which had efficiencies of 5.7% and 5.4%, the dryer not only enhanced product quality but also demonstrated significant economic advantages with a negligible capital cost of 50,000 INR against life cycle savings of 211,262 INR and 229,152 INR for fenugreek and turmeric, respectively. Borse et al.51 compared an indirect solar drying system with skewers to a conventional tray-based cabinet for drying bitter gourd slices. Their findings highlighted that the skewer system significantly shortened drying time and enhanced product quality due to superior air circulation.

Novelty of the current work

This research addresses a notable gap in the current literature regarding the drying characteristics of tomatoes and bottle gourds. The primary objective of this study is to evaluate and quantify the drying times of these vegetables using a double-slope solar dryer. The investigation delves into the nuanced thermal behavior of the dryer, focusing on moisture reduction trends, exergy analysis, and the activation energy of the vegetables under study. These areas represent significant voids in the existing body of research, making this study a pioneering contribution to the field.

The experimental methodology involves exposing tomatoes and bottle gourds to the specific conditions of a double-slope solar dryer. The research aims to unravel the complex interactions between the drying process and the environmental factors inherent in solar drying systems, through detailed observation and data collection. This comprehensive approach includes analyzing the moisture reduction trend specific to these vegetables. In addition to examining moisture reduction, this study incorporates an analysis of exergy—a thermodynamic property that measures the quality of energy within the system. This holistic view not only assesses the energy efficiency of the drying system but also introduces a novel perspective to the study of solar drying processes for tomatoes and bottle gourds. By integrating exergy analysis, the research distinguishes itself from existing literature and enhances its scholarly value.

Furthermore, the investigation evaluates the activation energy associated with the drying process of the selected vegetables. Understanding activation energy is crucial for elucidating the kinetics of drying, particularly the energy required for the transition from liquid to vapour. This aspect of the research fills a critical gap in the current knowledge base, enriching the discourse on solar drying techniques. Overall, this research article represents a groundbreaking effort to explore the drying characteristics of tomatoes and bottle gourds using a double-slope solar dryer. By integrating analyses of moisture reduction, exergy, and activation energy, this study offers a unique and valuable contribution to the advancing field of solar drying research.

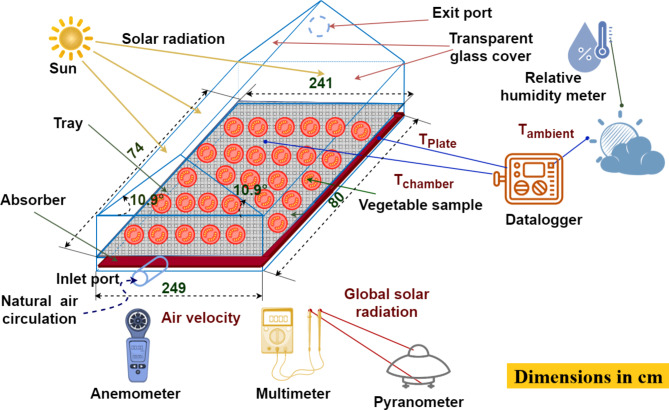

Development of double slope solar dryer

The setup for experimental analysis is comprised of a double-slope solar dryer based on natural convection compared with a selected tray for open sun drying. The construction of the double-slope solar dryer involves the utilization of a galvanized iron (GI) sheet encased in a 2.5 cm thick waterproof plywood configuration. This enveloping structure elegantly encompasses the bottom, two shorter sides, and two longer sides of the drying chamber. The GI sheet seamlessly covers the interior and exterior surfaces of the waterproof plywood, ensuring durability and thermal efficiency. The upper section of the solar dryer is adorned with two flat glass panels, each measuring 4 mm in thickness and characterized by a low iron content. The glass panels are ingeniously inclined at an angle of 10.9°, mirroring the geographical latitude of the location (Karaikal: 10.9°N 79.8°E) to optimize solar exposure. The overall dimensions of the dryer’s base are 249 cm × 80 cm. An interior aluminium mesh measuring 241 cm × 74 cm is meticulously positioned within the drying chamber to accommodate vegetable items during the drying process. Including a thoughtful mechanism for loading and unloading the inner mesh enhances operational convenience. The secure attachment of the glass surface to the waterproof plywood is ensured through the implementation of L clamps. Innovatively designed hollow pipes are strategically incorporated into the system to facilitate the ingress of atmospheric air from both the right and left edges of the chamber. Simultaneously, a separate channel is dedicated to the egress of hot air at an elevated position, ensuring an efficient and controlled drying process. Four vertical mild steel L-angle plates provide the foundational support of the chamber, each measuring 2.5 cm. Expanding beyond the spatial constraints of the desiccation chamber, an ingeniously designed, collapsible mild steel L-angle plate has been seamlessly affixed to the exterior, purposefully engineered to facilitate the integration of a supplementary aluminium mesh for open sun drying. This outwardly mounted mesh, boasting 241 cm × 74 cm dimensions, augments the experimental framework, bestowing a heightened degree of adaptability to the overall configuration. The schematic with dimensions and a real photograph of the experimental setup is illustrated in Figs. 1 and 2, capturing the frontal and rear views of the double-slope solar dryer with precision, thereby providing a comprehensive and visually enriched representation.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of experimental setup with dimensions.

Fig. 2.

Photograph of the double slope solar dryer (a) front view (b) back view.

Temperature and global radiation measurements

An arrangement comprising eight T-type thermocouples has been meticulously implemented to monitor temperature fluctuations within a solar drying chamber. Three of these thermocouples are exclusively dedicated to gauging the temperature of the hot air circulating within the chamber. Two of these strategically positioned thermocouples are at the chamber’s central edges. At the same time, the third is centrally located within the chamber, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of temperature distribution. The remaining five thermocouples serve the purpose of measuring the surface temperature of the drying chamber. Furthermore, one additional T-type thermocouple has been strategically employed to ascertain the ambient temperature surrounding the solar drying chamber. A high-precision Hukseflux Pyranometer (SR20-T1) has been incorporated into the system, adhering to the stringent standards set by ISO 9060 as a secondary standard to ensure precise global radiation measurements. All thermocouples are integrated with the Data Acquisition Unit to facilitate continuous data acquisition of temperature and radiation parameters. The Hukseflux Pyranometer and the Agilent 34,972 A Data Acquisition Unit can be observed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Photograph of (a) Hukseflux pyranometer; (b) Agilent data acquisition unit.

Uncertainty analysis

In the analysis of the solar drying system, the investigation of uncertainties in measured quantities is crucial for achieving accurate results. Errors in this context are classified into two primary categories: random errors and systematic errors. Given the specific conditions of the study, systematic errors are not present. Therefore, the focus is on random errors, which can be quantified through statistical methods and directly derived from the data provided by the measuring instruments. Random errors, being inherently unpredictable and varying with each measurement, require thorough statistical analysis to understand their impact on the overall results and to ensure the reliability of the findings.

The uncertainties in measuring instruments are estimated using the following relation52–54:

|

1 |

In the analysis of the solar drying process, the anticipated margin of uncertainty regarding both moisture reduction and drying rate was initially estimated at 1%. This estimate considered potential inaccuracies inherent to the measuring instruments employed. A meticulous examination of the daily output revealed that the variations in the measurements fell within a more refined range of ± 0.5%.

Furthermore, the study addressed the potential errors related to the measurement of temperature and solar radiation, which were quantified at 0.1% and 0.05%, respectively. Incorporating these factors into the overall assessment, the cumulative imprecision in evaluating the efficiency of the solar dryer was projected to be approximately ± 2%. This comprehensive error margin underscores the reliability of the solar drying system while acknowledging the inevitable limitations in measurement precision.

Experimental studies

Bottle gourds and tomatoes were chosen for the solar drying investigation due to their distinct moisture content characteristics and widespread agricultural relevance. Bottle gourds, with their high water content, present a significant challenge for effective drying and preservation, making them ideal for evaluating the efficiency of solar drying systems. Tomatoes, on the other hand, are a common, high-value crop prone to spoilage if not properly dried, offering a practical application for assessing the economic viability and effectiveness of solar drying methods. Together, these vegetables provide a diverse and representative sample for exploring the impact of solar drying on moisture reduction, preservation quality, and potential economic benefits.

The vegetables used in this study are obtained from the vegetable market at Karaikal, India. The thermal dynamics of the system underwent meticulous scrutiny through a comprehensive series of experimental investigations directed explicitly towards ascertaining the drying time required for distinct vegetables, namely bottle gourd, and tomatoes. These vegetables’ wet-basis moisture content was precisely quantified, serving as a fundamental parameter in the analyses. The experimental procedures were conducted on July 19, 2023, for bottle gourd and on July 23, 2023, for tomatoes. Each vegetable was sliced into 5 mm thick sections, allowing for a thorough and temporally distinct analysis of each variant. Throughout the experimental study, equivalent quantities of the selected vegetables were strategically positioned on the inner and outer aluminium mesh within the solar dryer setup and the open sun drying arrangement. The weight of the vegetables was meticulously determined utilizing an SF-400 A Electronic Compact Scale, thereby ensuring a high degree of precision in the measurements. To visually elucidate the experimental configuration, Figs. 4 and 5 vividly depict the distinctive double slope solar dryer setup, intricately showcasing the spatial arrangement of both the bottle gourd and tomatoes before the commencement of the drying process. These visual representations are invaluable complements to the detailed investigation, offering a clear and illustrative insight into the experimental apparatus and the initial disposition of the vegetables under scrutiny.

Fig. 4.

Experimentation of the double slope solar dryer with bottle gourd.

Fig. 5.

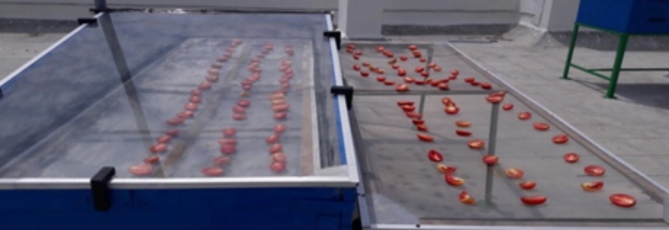

Experimentation of the double slope solar dryer with tomato.

Throughout the experimental timeline, spanning from the early hours of the morning to the evening twilight, meticulous records were maintained concerning several critical variables: the hot air temperatures, the condition of the drying plate, and the ambient environment surrounding the experimental setup. Hourly documentation of these parameters provided a thorough understanding of the dynamic interactions between the drying apparatus and its environmental context. Concurrently, the weight of the vegetables under study exhibited a noticeable decrease, signifying the progressive and ongoing drying process. In addition to tracking these variables, the global radiation levels for the day were carefully measured, adding a crucial layer of environmental context to the experiment. This comprehensive approach was designed to capture the complex relationship between solar exposure and the resulting desiccation of the vegetables. As the day drew to a close, the experimental protocol transitioned into the retrieval phase. During this phase, the dried specimens were systematically extracted from both the inner and outer mesh placements within the double-slope solar dryer. This strategic positioning facilitated a detailed assessment of drying efficacy across different regions of the apparatus. The final stage involved precise weighing of the desiccated vegetables, which provided quantifiable insights into the extent of moisture removal achieved through the solar drying process.

Figures 6 and 7 offer visual documentation of the experimental setup and the observable changes occurring before and after the drying process. These figures serve as graphical representations of the variables under investigation, specifically illustrating the dehydration of bottle gourd and tomatoes, and highlighting the rigor applied in the experimental design.

Fig. 6.

Experimentation of the double slope solar dryer with bottle gourd after drying.

Fig. 7.

Experimentation of the double slope solar dryer with tomato after drying.

Exergy analysis and activation energy

Exergy analysis

Exergy, which is the greatest amount of energy that may be used in a thermodynamic system, is essential to comprehending energy dissipation and offers important information for increasing productivity, decreasing irreversible losses, and minimizing environmental effects. Exergy assessments of solar drying processes have been the subject of numerous academic studies aimed at improving their efficiency. Researchers can determine the main locations where energy losses occur by looking at the energy inflows and outflows. When analyzing a drying apparatus’s efficiency from the standpoint of energy, variables like the product’s mass, the drying temperature, and the thermophysical characteristics of the drying air all play a role55,56.

The formula for estimating the exergy of a dryer is as follows:

|

2 |

Exergy inflow and outflow

and outflow  of the dryer are represented as follows:

of the dryer are represented as follows:

|

3 |

|

4 |

The temperatures of the drying chamber’s inlet (Tdci), outlet (Tdco), and ambient air (To).

The dryer’s exergetic efficiency (ηex) and exergy loss (Eloss) are as follows:

|

5 |

|

6 |

Effective moisture diffusivity and activation energy

Equation (7) is the basic formula for Fick’s unstable state of effective moisture diffusivity2,57.

|

7 |

The equation uses the following variables: MR for the moisture ratio, L is thickness, t is drying time, n is a positive integer, and Deff is moisture diffusivity.

An analysis of the activation energy was conducted using the Arrhenius equation. The relation between drying air temperature and moisture diffusivity is given by Eq. (8)58,59.

|

8 |

Economic analysis

The annualized cost and the payback period were the subjects of economic evaluations in this work. This procedure is based on four distinct cash flows: the machine’s purchase price, the machine’s resale value, the annual recurring maintenance and repair expenditures, and the interest paid on funds. The Eq. (9) provides the annual cost Ac, which was computed in the current study by adding the solar dryer’s operating cost60,61.

|

9 |

|

10 |

is solar dryer incurring material and labour costs.

is solar dryer incurring material and labour costs.

is maintenance cost of solar dryer per year.

is maintenance cost of solar dryer per year.

is operational cost of solar dryer per year.

is operational cost of solar dryer per year.

is years the solar dryer is owned.

is years the solar dryer is owned.

is rate of inflation.

is rate of inflation.

is rate of interest.

is rate of interest.

The payback period is the time required to recover the cost of the solar dryer while accounting for inflation and interest rates. Another way to describe the payback period is the time it takes for the cumulative savings to equal the whole initial investment62. Equation (11) is utilized to determine the payback period ( ).

).

|

11 |

where  is annual cost of dried sample.

is annual cost of dried sample.  is annual cost of fresh samples.

is annual cost of fresh samples.  is annual cost

is annual cost

Result and discussion

Bottle gourd

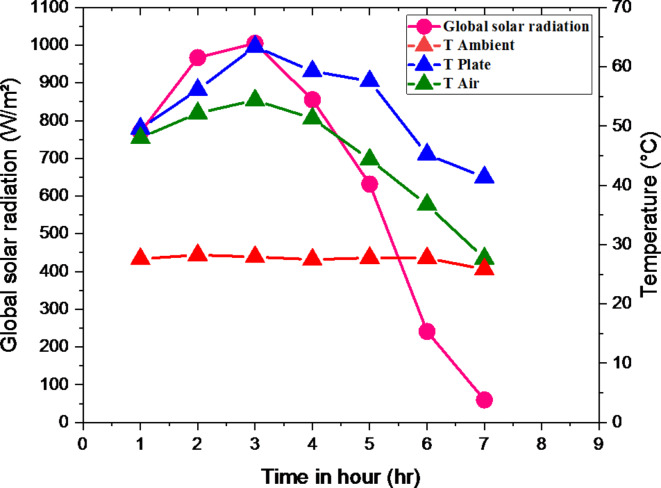

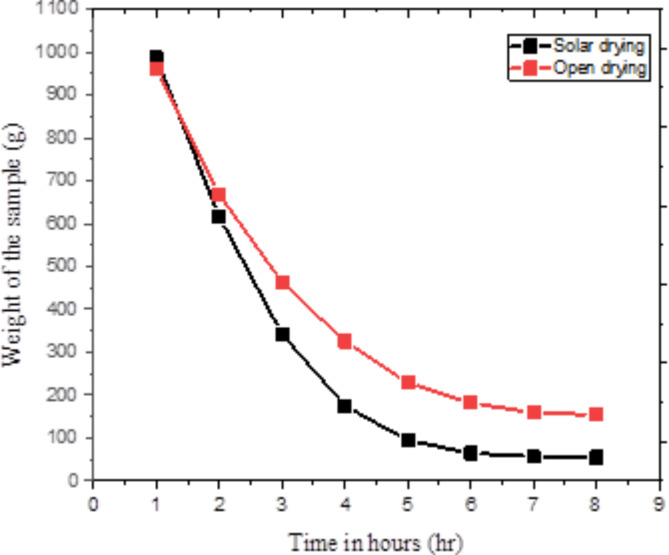

In the experimental study, a double-slope solar dryer was employed to evaluate its effectiveness in drying bottle gourd specimens. Initially, two identical quantities of bottle gourd, each weighing approximately 1166 g, were selected for the experiment. One batch was placed within the solar dryer’s mesh, while the other batch was exposed to natural drying conditions outside. Throughout the study, a range of parameters associated with the solar dryer were meticulously monitored and recorded on an hourly basis. These parameters included global radiation levels, ambient temperatures, air temperatures along the central axis of the dryer, and temperatures of the plates at various points. Concurrently, the reduction in moisture content was assessed by periodically measuring the weight of the bottle gourd specimens. At the start of the experiment, each specimen weighed 1166 g. By the conclusion of the drying process, the weight of the specimens had decreased to 188 g. The results, as illustrated in Fig. 8, highlight the pronounced differences in moisture reduction between the solar drying method and natural convection drying. The results demonstrate the superior efficiency of the solar dryer in accelerating the drying process and achieving a more significant reduction in moisture content compared to conventional open-sun drying methods. The pronounced difference observed underscores the effectiveness of the solar drying technique in enhancing the efficiency of moisture removal, thereby offering a more effective alternative to natural drying practices. This comparative analysis confirms that the double-slope solar dryer significantly outperforms traditional drying methods in terms of drying efficiency and overall effectiveness.

Fig. 8.

Variation of weight loss of the bottle gourd with time.

The results of the six-hour solar drying experiment, as illustrated in Fig. 8, reveal a significant improvement in moisture reduction achieved through the solar dryer compared to open sun drying. Specifically, the solar drying method resulted in an impressive 83.87% reduction in moisture content on a wet basis, whereas open sun drying achieved a reduction of 77.87% over the same period. This outcome highlights the superior efficiency of solar drying techniques for agricultural products, aligning with sustainable practices and contributing meaningfully to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

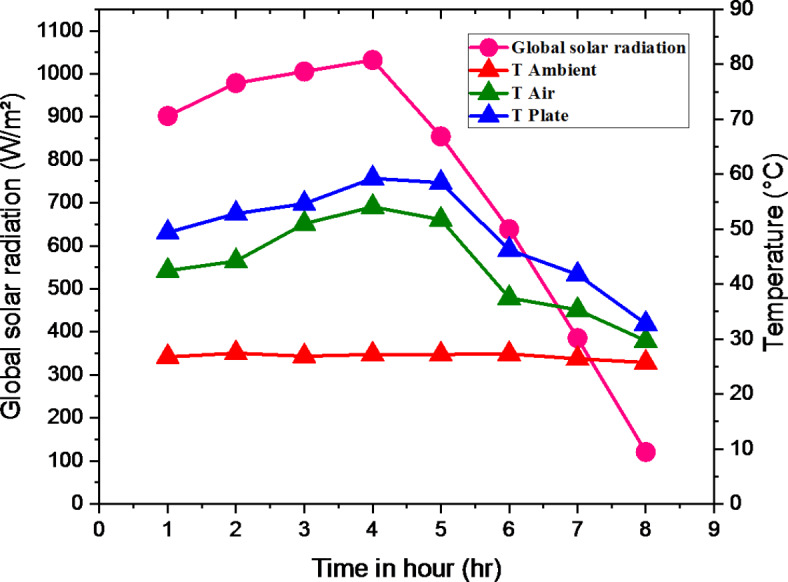

The natural convection-based double slope solar dryer demonstrated a notable 6% greater reduction in moisture content relative to open sun drying. This enhanced performance underscores the effectiveness of the solar dryer in accelerating the drying process, thereby improving the preservation quality of the dried products. The meticulous monitoring of critical variables, including average air temperature, plate temperature, ambient temperature, and solar radiation, provided valuable insights into the thermal dynamics of the drying system.

Figure 9 illustrates the thermal behaviour of the system, showing a peak air temperature of 54.12 °C and a maximum plate temperature of 63.38 °C. These temperature metrics, along with the incident solar flux, were found to be closely correlated, indicating a strong dependence of the drying system’s efficiency on the intensity of solar radiation. The observed temperature variations confirm the high sensitivity of the drying process to solar input, affirming the practical feasibility and efficacy of the solar dryer system.

Fig. 9.

Variation of air temperature, plate temperature, ambient temperature, and global solar radiation with time for bottle gourd drying.

The data from this experiment corroborate the advantages of solar drying over traditional methods, emphasizing the potential for optimizing drying processes through advanced solar drying technologies. The observed improvements not only validate the effectiveness of the solar dryer in enhancing drying efficiency but also underscore its contribution to sustainable agricultural practices and environmental conservation.

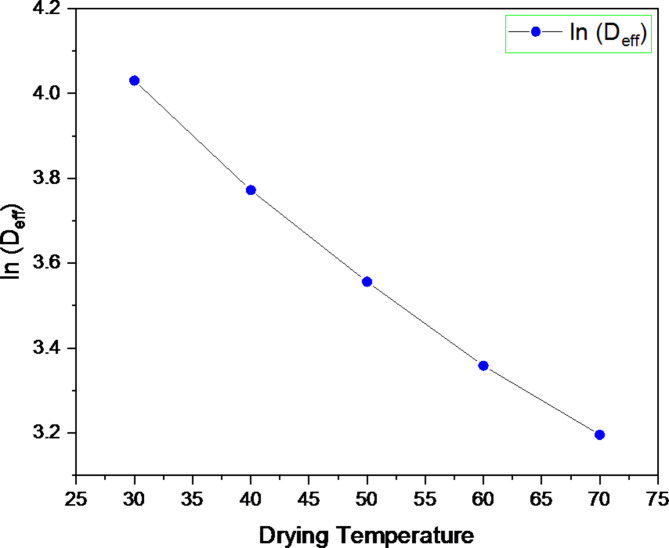

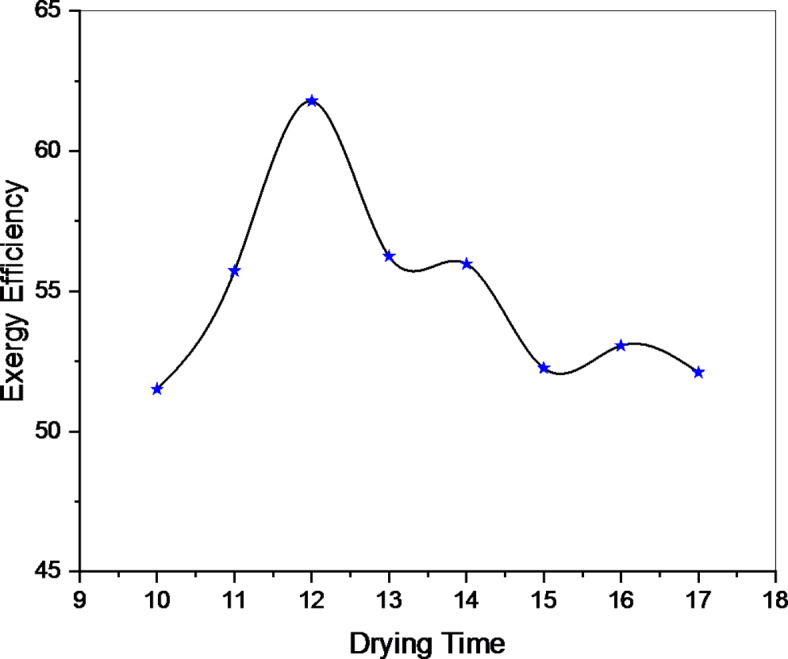

The natural convection dryer, illustrated in Fig. 10, achieved an impressive exergy efficiency of 61.78%. This efficiency is notably high, especially when compared to the typical range observed for natural convection drying processes, which spans from 51.50% to the reported peak. This substantial variation underscores the effectiveness and adaptability of natural convection drying, highlighting its potential for diverse applications. Further elucidation is provided by Fig. 11, which charts the moisture diffusivity of the Bottle Gourd throughout the drying process. The natural convection method demonstrated moisture diffusivity rates ranging from 3.12 × 10−11 to 4.08 × 10−11 m2/s. In contrast, open sun drying exhibited a markedly different range, from 9.34 × 10−11 m2/s to 1.83 × 10−11. These results delineate the intricate dynamics of moisture movement under different drying conditions, with natural convection drying generally facilitating more efficient moisture removal compared to open sun drying. The effective moisture diffusivity of dried locust beans and cucumber was found to be similar to current research63,64.

Fig. 10.

Variation of exergy efficiency with the drying time of bottle gourd.

Fig. 11.

Variation of ln (Deff) with temperature of bottle gourd.

Additionally, the determination of activation energy for dried Bottle Gourd provided further insights into the energy requirements across various drying techniques. For the natural convection dryer, activation energy values fluctuated between 29.14 kJ/mol to 46.41 kJ/mol, reflecting the energy demands encountered at different stages of the drying process. Conversely, open sun drying demonstrated a range of activation energy from 30.52 kJ/mol to 54.59 kJ/mol. Although the energy requirements for both methods are comparable, the observed differences in activation energy underscore the varying energy demands associated with each drying approach. The range of moisture diffusivity and activation energy for the Bottle gourd is in close agreement with other vegetable samples reported in the literature65.

Overall, these findings highlight the efficiency and versatility of natural convection drying compared to open sun drying. The significant variation in exergy efficiency, moisture diffusivity, and activation energy further illustrates the complex interplay of factors influencing the performance of different drying technologies.

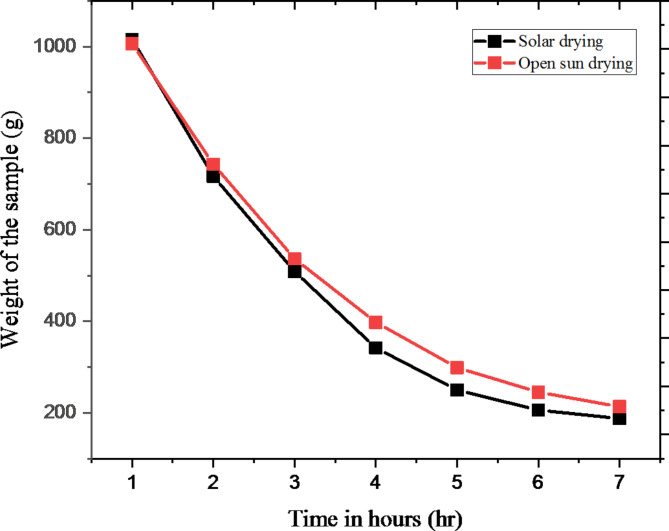

Tomato

The experimentation involving tomatoes with the double-slope solar drier followed a methodology akin to that employed for bottle gourds. Two batches of tomatoes, each weighing 986 g, were subjected to both solar drying and open drying conditions. Systematic observations were carried out at regular intervals following established protocols, focusing on critical metrics such as weight loss and moisture content. The objective was to assess the efficacy of the solar drier utilizing natural convection and to compare its performance against traditional open sun drying methods.

Figure 12 provides a comprehensive depiction of the variations in moisture content of tomatoes subjected to both drying methods. The data delineates the differences in drying efficiency between the solar dryer and the conventional open sun drying, illustrating how each method influences the drying process. As demonstrated, the solar drier achieved a notable reduction in moisture content, with a remarkable 94.42% decrease on a wet basis. In contrast, the open sun drying method yielded a slightly lower moisture removal rate of 92.82%. This results in a measurable difference of approximately 1.6% in moisture extraction between the two techniques. This disparity, though relatively small, underscores the superior performance of the solar drier in enhancing moisture removal from tomatoes. Interestingly, in comparison to the drying trials conducted with bottle gourds, both drying methods exhibited improved moisture removal in tomatoes. This can be attributed to the increased intensity of solar radiation during the tomato drying trials. Analysis of the temperature data presented in Fig. 13 reveals that the solar drier achieved a peak plate temperature of 59.25 °C and a maximum air temperature of 54.42 °C. This elevated temperature range likely contributed to the enhanced moisture loss observed in tomatoes.

Fig. 12.

Variation of weight loss of the tomato with time.

Fig. 13.

Variation of air temperature, plate temperature, ambient temperature, and global solar radiation with time for tomato drying.

It is noteworthy that the higher moisture content of tomatoes compared to bottle gourds may have played a role in the increased efficiency of moisture removal. The greater water content in tomatoes may facilitate a more pronounced reduction in moisture during the drying process, thereby explaining the improved drying performance observed. Overall, the results underscore the efficacy of the solar drier in achieving superior moisture removal compared to traditional methods. The increased solar radiation intensity and elevated temperatures experienced during the drying process are significant factors contributing to the enhanced performance of the solar drier in reducing tomato moisture content.

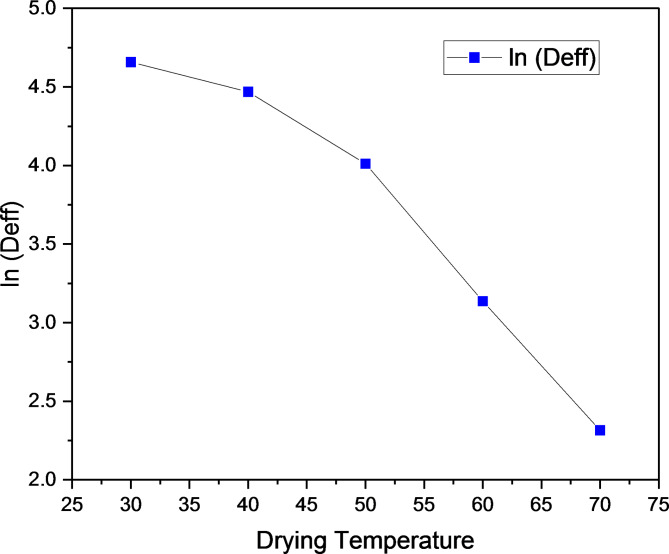

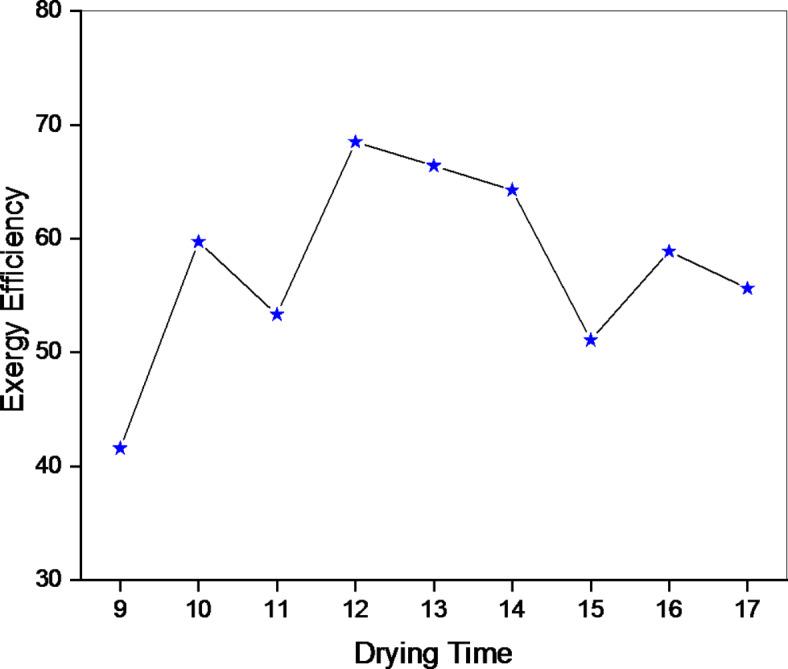

In evaluating the performance of the natural convection dryer, it is noteworthy that the system achieved an impressive exergy efficiency of 68.50%, as illustrated in Fig. 14. The exergy efficiency for natural convection drying exhibited a broad spectrum, ranging from a minimum of 41.58% to the aforementioned peak of 68.50%. This wide range underscores the inherent adaptability of the drying process to varying operational settings and environmental conditions, emphasizing the process’s dynamic responsiveness and flexibility. Figure 15 provides a comprehensive depiction of activation energy requirements, offering a nuanced understanding of the energy demands associated with different drying techniques. For Open Sun Drying, the activation energy varied between 27.16 and 55.42 kJ/mol. In contrast, Natural Convection Drying demonstrated a slightly narrower range, from 23.32 to 42.02 kJ/mol. This comparative analysis reveals the diverse energy requirements inherent in various drying methods and highlights the fundamental thermodynamic principles that govern the drying process. The dried tomato activation energy of solar dryer was found similar to the red banana and poovan banana66,67.

Fig. 14.

Variation of exergy efficiency with the drying time of Tomato.

Fig. 15.

Variation of ln(Deff) with temperature for tomato.

Furthermore, the study of moisture diffusivity has yielded significant insights into the drying kinetics. The moisture during solar drying ranged from 4.65 × 10−11 to 2.31 × 10−11 m2/s, while Natural Convection Drying exhibited a broader range of 9.56 × 10−11 to 2.13 × 10−11 m2/s. These findings illustrate the distinct rates at which moisture diffuses under different drying conditions, pointing to the critical moisture transport pathways necessary for achieving optimal drying efficiency. The data underline the importance of understanding these transport mechanisms to enhance the performance and efficacy of drying processes. Similar results have been observed by dried red dacca and banana66,68.

The cost of labor and materials to construct the solar dryer represents the project’s initial investment ( ). The primary components of the dryer include the galvanized iron sheet, waterproof plywood, aluminum drying chamber, steel frame, two flat transparent glass, and aluminum mesh, all of which are included in the initial cost for a double-slope solar dryer. The fresh sliced tomato and bottle gourd weighed 1 kg, and they took approximately a day to dry, yielding 0.06 and 0.160 kg of dried tomato and bottle gourd, respectively. The solar dryer’s running expenses include the cost of preparing fresh vegetables and compensating the laborers for their work. Based on the price from a nearby supermarket and after accounting for the cost of packaging and delivery by the farmer or merchant providing the dried sample, the projected selling price of the dried sample is ₹500/kg and ₹400/kg. In January 2024, Trading Economics (2024) projects 3.2% inflation and 12% interest rates for India.

). The primary components of the dryer include the galvanized iron sheet, waterproof plywood, aluminum drying chamber, steel frame, two flat transparent glass, and aluminum mesh, all of which are included in the initial cost for a double-slope solar dryer. The fresh sliced tomato and bottle gourd weighed 1 kg, and they took approximately a day to dry, yielding 0.06 and 0.160 kg of dried tomato and bottle gourd, respectively. The solar dryer’s running expenses include the cost of preparing fresh vegetables and compensating the laborers for their work. Based on the price from a nearby supermarket and after accounting for the cost of packaging and delivery by the farmer or merchant providing the dried sample, the projected selling price of the dried sample is ₹500/kg and ₹400/kg. In January 2024, Trading Economics (2024) projects 3.2% inflation and 12% interest rates for India.

The annual cost of a solar dryer is ₹42,037.45, according to Table 1’s economic factors. Combining the dryer’s revenue of ₹52,865 for bottle gourds and ₹63,791.00 for tomatoes results in a payback period of 1.6 and 2 years, respectively. Mukanema and Simate69 found a two-year payback period in their economic analysis of a natural convection solar tunnel dryer for banana slices. In another study, Philip et al.70 investigated a greenhouse solar dryer with a 100 kg capacity to produce high-quality dried items. Researchers discovered that the dryer’s payback period varied from 1.5 to 2.1 years. Previous investigations reported payback periods similar to those identified in the current investigation.

Table 1.

Parameters used in the economic analyses.

| S. no. | Parameter | Amount (tomato) | Amount (bottle gourd) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fresh sample processed per year | ₹3,015.00 | ₹1,253.00 |

| 2 | Dried sample produced per year | ₹211.63 | ₹152.12 |

| 3 | Solar dryer investment | ₹29,640 | ₹29,640 |

| 4 | Revenue from sale of dried sample from dryer per year | ₹63,791.00 | ₹52,865.00 |

| 5 | Operations and maintenance | ₹9,697.29 | ₹9,697.29 |

| 6 | Interest rate, % | 12 | 12 |

| 7 | Inflation rate, % | 3.2 | 3.2 |

| 8 | Years of ownership | 10 | 10 |

| 9 | Annual cost of dryer | ₹42,037.45 | ₹42,037.45 |

| 10 | Payback period, years | 1.6 | 2 |

Conclusions

Solar dryers, designed for vegetable drying, emerged as sustainable alternatives, countering the challenges posed by energy-intensive methods like open sun drying deeply rooted in cultural traditions. Developing a double-slope solar dryer showcased significant advancements in vegetable dehydration technology, focusing on bottle gourds and tomatoes. The choice of bottle gourd and tomatoes, with varying water content, added a dynamic element to the study, influencing the drying process and highlighting the solar dryer’s adaptability. The conclusions are as follows:

The comparative analysis between the solar dryer and traditional open sun drying methods has demonstrated the solar dryer’s superior performance in reducing moisture content, with an impressive 94.42% reduction in tomatoes and 83.87% in bottle gourds. These results underscore the solar dryer’s potential as a more efficient alternative to conventional drying techniques.

The experimental findings indicate that the drying rate of bottle gourd and tomatoes in the solar dryer significantly exceeds that of traditional open sun drying methods.

During the drying of bottle gourds, the solar dryer reached peak air and plate temperatures of 54.12 °C and 63.38 °C, respectively. Similarly, during tomato drying, peak air and plate temperatures of 54.42 °C and 59.25 °C were recorded. These elevated temperatures contributed to the enhanced drying process, leading to faster and more effective moisture removal.

Exergy efficiency analysis further affirmed the solar dryer’s advantage, with the maximum efficiency for bottle gourd reaching 61.78% and for tomato 68.5%, both notably higher than those achieved through open sun drying.

In terms of moisture diffusivity, the outcomes of study revealed a range of 3.12 × 10–11 to 4.31 × 10–11 m2/s for bottle gourd during natural convection drying, and 9.34 × 10–11 to 1.83 × 10–11 m2/s for open sun drying. For tomato, moisture diffusivity ranged from 4.65 × 10–11 to 2.31 × 10–11 m2/s under natural convection, compared to 9.56 × 10–11 to 2.13 × 10–11 m2/s for open sun drying.

The activation energy required for drying was also found to be lower for the solar dryer, with a favorable range of 29.14–46.41 kJ/mol for bottle gourd and 27.16–55.42 kJ/mol for tomato, both of which surpassed the energy demands of open sun drying.

The visual assessments of the dried samples from the solar dryer showed them to be free from dust and contaminants, indicating the system’s potential for producing clean, high-quality dried vegetables with reduced spoilage and waste.

Furthermore, the economic analysis reveals a payback period of 2 years for bottle gourd and 1.6 years for tomatoes, highlighting the financial viability of the solar dryer system for vegetable preservation.

This study highlights the role of solar dryers as a sustainable and eco-friendly solution, contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by promoting energy-efficient practices, reducing food waste, and enhancing environmental resilience.

In conclusion, this study emphasizes the significant role of solar dryers as an effective and sustainable solution for vegetable preservation, aligning with global efforts towards sustainable development. The ability of solar drying technologies to leverage renewable energy not only mitigates post-harvest losses but also reduces dependence on conventional energy sources, thereby contributing to environmental sustainability and resilience in food systems. The integration of solar dryers into preservation practices holds substantial potential for enhancing food security, particularly in regions vulnerable to energy and food shortages.

Future recommendations

Nevertheless, despite the promising outcomes observed, there remains ample opportunity for further exploration. Future research could delve deeper into assessing the physicochemical properties of vegetables post-drying, including nutritional content, texture retention, and overall quality, to gain a holistic understanding of the process’s impact. In addition, advancing the design and optimizing the environmental footprint of solar dryers will be crucial to foster greater adoption across varying climates and regions. Continuous innovation in these areas, alongside comprehensive life-cycle assessments, can accelerate the implementation of solar drying technology. Moreover, for further advancements, exploring drying kinetics and the application of forced convection in similar contexts is recommended. Such investigations would offer a more nuanced understanding of the drying mechanisms and enhance overall system performance. Thus, the pursuit of innovative designs and deeper scientific inquiry will be essential to fully unlock the potential of solar dryers as a pivotal technology in sustainable food preservation.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to Universiti Malaysia Pahang Al-Sultan Abdullah (UMPSA) and the Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia, for their invaluable financial support provided through the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme: FRGS/1/2021/STG05/UMP/02/5 (RDU210126). “Dr. Subbarama Kousik Suraparaju” is the recipient of the UMPSA Post-Doctoral Fellowship. The authors thank the Researchers Supporting Project number (RSPD2025R698), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research. The authors would like to acknowledge the Solar Energy Laboratory, Department of Mechanical Engineering, Sri Vasavi Engineering College (A), Tadepalligudem, Andhra Pradesh, and Department of Mechanical Engineering, Mepco Schlenk Engineering College, Sivakasi, Tamil Nadu INDIA for providing experimental facilities and research support.

Abbreviations

- PCM

Phase change material

- ANN

Artificial neural network

- DPI

Dryer performance index

- PID

Proportional-integral-derivative

- PVT

Photovoltaic-thermal

- PAU

Preheated air unit

- ADSD

Advanced domestic solar dryer

- DC

Direct current

- INR, ₹

Indian rupees

- GI

Galvanized iron

- Tdci

Drying chamber inlet temperature

- Tdco

Drying chamber outlet temperature

- TO

Ambient air temperature

- ηex

Dryer’s exergetic efficiency

- Eloss

Dryer’s exergy loss

- MR

Moisture ratio

- Ac

Annual cost

- SDG

Sustainable development goals

Author contributions

S.K.S, E.E, G.M, M.S and E.P.V developed the idea and conducted the experiments, S.K.N, S.K.S, R.K.R. wrote the manuscript, D.B, Y.F, M.E.M.S, ZM, edited the manuscript, all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this Article was revised: The original version of this Article contained errors in the References. References 70, 72, and 73 were provided in the Reference List but not cited in the body of the text. As a result of the changes, the References were deleted and renumbered accordingly. Additionally, Reference 71 was omitted and now is listed as Reference 17.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

12/16/2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41598-024-82852-3

Contributor Information

Mahendran Samykano, Email: mahendran@umpsa.edu.my.

Sendhil Kumar Natarajan, Email: sendhil80@nitpy.ac.in.

Krishna Moorthy Sivalingam, Email: drkrishna.micro@wsu.edu.et.

References

- 1.Natarajan, S. K., Elangovan, E., Elavarasan, R. M., Balaraman, A. & Sundaram, S. Review on solar dryers for drying fish, fruits, and vegetables. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.29, 40478–40506. 10.1007/s11356-022-19714-w (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar, S., Muthuvairavan, G. & Kousik, S. Innovative insights into solar drying of Kola Fish. 59, 858–873. 10.3103/S0003701X23601369 (2023).

- 3.Muthuvairavan, G., Manikandan, S., Elangovan, E. & Natarajan, S. K. Assessment of Solar Dryer performance for drying different food materials: a Comprehensive Review. Dry. Sci. Technol.10.5772/INTECHOPEN.112945 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fudholi, A. et al. Review of solar drying systems with air based solar collectors in Malaysia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.51, 1191–1204. 10.1016/J.RSER.2015.07.026 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes, L. & Tavares, P. B. A review on solar drying devices: heat transfer, air movement and type of chambers. Solar4, 15–42. 10.3390/SOLAR4010002 (2024).

- 6.Thakur, A. K. et al. Advancements in solar technologies for sustainable development of agricultural sector in India: a comprehensive review on challenges and opportunities. Environ. Sci. Pollution Res. 2022. 29, 29. 10.1007/S11356-022-20133-0 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elangovan, E. & Natarajan, S. K. Experimental study on Drying kinetics of Ivy gourd using solar dryer. J. Food Process Eng.44, 1–39. 10.1111/jfpe.13714 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madhankumar, S., Viswanathan, K., Taipabu, M. I. & Wu, W. A review on the latest developments in solar dryer technologies for food drying process. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess.58, 103298. 10.1016/J.SETA.2023.103298 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Natarajan, S. K., Elavarasan, E. & A Review on Computational Fluid Dynamics Analysis on Greenhouse Dryer. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. ;312:012033. (2019). 10.1088/1755-1315/312/1/012033

- 10.Singh, P. & Gaur, M. K. A review on thermal analysis of hybrid greenhouse solar dryer (HGSD). J. Therm. Eng.8, 103–119. 10.18186/thermal.1067047 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimpy, K. M., Kumar, A. & Designs Performance and economic feasibility of domestic solar dryers. Food Eng. Rev.15, 156–186. 10.1007/S12393-022-09323-1/METRICS (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ekechukwu, O. V. & Norton, B. Review of solar-energy drying systems II: an overview of solar drying technology. Energy. Conv. Manag.40, 615–655. 10.1016/S0196-8904(98)00093-4 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muthuvairavan, G. & Kumar Natarajan, S. Experimental study on drying kinetics and thermal modeling of drying Kohlrabi under different solar drying methods. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progress. 44, 102074. 10.1016/j.tsep.2023.102074 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prakash, O., Laguri, V., Pandey, A., Kumar, A. & Kumar, A. Review on various modelling techniques for the solar dryers. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.62, 396–417. 10.1016/j.rser.2016.04.028 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manikandan, S., Muthuvairavan, G., Samykano, M. & Natarajan, S. K. Numerical simulation of various PCM container configurations for solar dryer application. J. Energy Storage. 86, 111294. 10.1016/J.EST.2024.111294 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chirarattananon, S. & Chinporncharoenpong, C. A steady-state model for the forced Convection Solar Cabinet Dryer. Sol. Energy. 41, 349–360 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tripathi et al. Advancing solar PV panel power prediction: A comparative machine learning approach in fluctuating environmental conditions. Case Stud. Thermal Eng.59, 104459. 10.1016/j.csite.2024.104459 (2024).

- 18.Das, S. & Kumar, Y. Design and performance of a Solar Dryer with Vertical Collector Chimney suitable for rural application. Energy. Conv. Manag.29, 129–135 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garg, H. P. & Kumar, R. Studies on semi-cylindrical solar tunnel dryers: estimation of solar irradiance. Renew. Energy. 13, 393–400. 10.1016/S0960-1481(98)00002-0 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain, D. & Tiwari, G. N. Effect of greenhouse on crop drying under natural and forced convection II. Thermal modeling and experimental validation. Energy. Conv. Manag.45, 2777–2793. 10.1016/j.enconman.2003.12.011 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh, S., Singh, P. P. & Dhaliwal, S. S. Multi-shelf portable solar dryer. Renew. Energy. 29, 753–765. 10.1016/j.renene.2003.09.010 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shanmugam, V. & Natarajan, E. Experimental investigation of forced convection and desiccant integrated solar dryer. Renew. Energy. 31, 1239–1251. 10.1016/j.renene.2005.05.019 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eltief, S. A., Ruslan, M. H. & Yatim, B. Drying chamber performance of V-groove forced convective solar dryer. Desalination. 209, 151–155. 10.1016/j.desal.2007.04.024 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gbaha, P., Yobouet Andoh, H., Kouassi Saraka, J., Kaménan Koua, B. & Touré, S. Experimental investigation of a solar dryer with natural convective heat flow. Renew. Energy. 32, 1817–1829. 10.1016/j.renene.2006.10.011 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shanmugam, V. & Natarajan, E. Experimental study of regenerative desiccant integrated solar dryer with and without reflective mirror. Appl. Therm. Eng.27, 1543–1551. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2006.09.018 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sreekumar, A., Manikantan, P. E. & Vijayakumar, K. P. Performance of indirect solar cabinet dryer. Energy. Conv. Manag.49, 1388–1395. 10.1016/j.enconman.2008.01.005 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sethi, V. P. & Arora, S. Improvement in greenhouse solar drying using inclined north wall reflection. Sol. Energy. 83, 1472–1484. 10.1016/j.solener.2009.04.001 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amer, B. M. A., Hossain, M. A. & Gottschalk, K. Design and performance evaluation of a new hybrid solar dryer for banana. Energy. Conv. Manag.51, 813–820. 10.1016/j.enconman.2009.11.016 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Montero, I., Blanco, J., Miranda, T., Rojas, S. & Celma, A. R. Design, construction and performance testing of a solar dryer for agroindustrial by-products. Energy. Conv. Manag.51, 1510–1521. 10.1016/j.enconman.2010.02.009 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bal, L. M., Satya, S., Naik, S. N. & Meda, V. Review of solar dryers with latent heat storage systems for agricultural products. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.15, 876–880. 10.1016/j.rser.2010.09.006 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slama, R. & Ben, Combarnous, M. Study of orange peels dryings kinetics and development of a solar dryer by forced convection. Sol. Energy. 85, 570–578. 10.1016/j.solener.2011.01.001 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maiti, S., Patel, P., Vyas, K., Eswaran, K. & Ghosh, P. K. Performance evaluation of a small scale indirect solar dryer with static reflectors during non-summer months in the Saurashtra region of western India. Sol. Energy. 85, 2686–2696. 10.1016/j.solener.2011.08.007 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gupta, V., Sunil, L., Sharma, A. & Sharma, N. Construction and performance analysis of an indirect solar dryer integrated with solar air heater. Procedia Eng.38, 3260–3269. 10.1016/j.proeng.2012.06.377 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh, S. & Kumar, S. Development of convective heat transfer correlations for common designs of solar dryer. Energy. Conv. Manag.64, 403–414. 10.1016/j.enconman.2012.06.017 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kushwah, A., Gaur, M. K., Kumar, A. & Singh, P. Application of ANN and Prediction of Drying Behavior of Mushroom Drying in side hybrid greenhouse solar dryer: an experimental validation. J. Therm. Eng.8, 221–234. 10.14744/jten.2021.0006 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh, S. & Kumar, S. New approach for thermal testing of solar dryer: development of generalized drying characteristic curve. Sol. Energy. 86, 1981–1991. 10.1016/j.solener.2012.04.001 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Şevik, S. Design, experimental investigation and analysis of a solar drying system. Energy. Conv. Manag.68, 227–234. 10.1016/j.enconman.2013.01.013 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mustayen, A. G. M. B., Mekhilef, S. & Saidur, R. Performance study of different solar dryers: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.34, 463–470. 10.1016/j.rser.2014.03.020 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan, Y., Dyah, N. & Abdullah, K. Performance of a recirculation type integrated collector drying chamber (ICDC) solar dryer. Energy Procedia. 68, 53–59. 10.1016/j.egypro.2015.03.232 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dhanushkodi, S., Wilson, V. H. & Sudhakar, K. Mathematical modeling of drying behavior of cashew in a solar biomass hybrid dryer. Resource-Efficient Technol.3, 359–364. 10.1016/j.reffit.2016.12.002 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Castillo-Téllez, M., Pilatowsky-Figueroa, I., López-Vidaña, E. C., Sarracino-Martínez, O. & Hernández-Galvez, G. Dehydration of the red Chilli (Capsicum annuum L., costeño) using an indirect-type forced convection solar dryer. Appl. Therm. Eng.114, 1137–1144. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2016.08.114 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nabnean, S. et al. Experimental performance of a new design of solar dryer for drying osmotically dehydrated cherry tomatoes. Renew. Energy. 94, 147–156. 10.1016/j.renene.2016.03.013 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chauhan, P. S. & Kumar, A. Heat transfer analysis of north wall insulated greenhouse dryer under natural convection mode. Energy. 118, 1264–1274. 10.1016/j.energy.2016.11.006 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sekyere, C. K. K., Forson, F. K. & Adam, F. W. Experimental investigation of the drying characteristics of a mixed mode natural convection solar crop dryer with back up heater. Renew. Energy. 92, 532–542. 10.1016/j.renene.2016.02.020 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar, M., Sansaniwal, S. K. & Khatak, P. Progress in solar dryers for drying various commodities. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.55, 346–360. 10.1016/j.rser.2015.10.158 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tiwari, S., Tiwari, G. N. & Al-Helal, I. M. Development and recent trends in greenhouse dryer: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev.65, 1048–1064. 10.1016/j.rser.2016.07.070 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kabeel, A. E. & Abdelgaied, M. Performance of novel solar dryer. Process Saf. Environ. Prot.102, 183–189. 10.1016/j.psep.2016.03.009 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tuncer, A. D. et al. Experimental and numerical analysis of a grooved hybrid photovoltaic-thermal solar drying system. Appl. Therm. Eng. 218. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2022.119288 (2023).

- 49.Kaur, S., Singh, M., Zalpouri, R. & Kaur, K. Potential application of domestic solar dryers for coriander leaves: drying kinetics, thermal efficiency, and quality assessment. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy. 42, e14092. 10.1002/EP.14092 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh, S., Gill, R. S., Hans, V. S. & Singh, M. A novel active-mode indirect solar dryer for agricultural products: experimental evaluation and economic feasibility. Energy. 222, 119956. 10.1016/j.energy.2021.119956 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Borse, S. M., Singh, M., Kaur, P., Singh, S. & Zalpouri, R. Drying behavior and nutritional quality of bitter-gourd slices dried in a solar dryer with tray and skewer arrangement. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy. e14445. 10.1002/EP.14445 (2024).

- 52.J. P. Holman. Experimental Methods for Engineers (The McGraw-Hill Companies, 2007).

- 53.Peddojula, M. K. et al. Synergetic integration of machining metal scrap for enhanced evaporation in solar stills: a sustainable novel solution for potable water production. Therm. Sci. Eng. Progress. 51, 102647. 10.1016/j.tsep.2024.102647 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suraparaju, S. K. et al. Enhancing the productivity of pyramid solar still utilizing repurposed finishing pads as cost-effective porous material. Desalination Water Treat.320, 100733. 10.1016/J.DWT.2024.100733 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elangovan, E. & Natarajan, S. K. Effects of pretreatments on quality attributes, moisture diffusivity, and activation energy of solar dried ivy gourd. J. Food Process Eng.44, e13653. 10.1111/JFPE.13653 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elangovan, E. & Natarajan, S. K. Convective and evaporative heat transfer coefficients during drying of ivy gourd under natural and forced convection solar dryer. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.30, 10469–10483. 10.1007/s11356-022-22865-5 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doymaz, I. Air-drying characteristics of tomatoes. J. Food Eng.78, 1291–1297. 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.12.047 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Eleiwi, M. A., Mohammed, M. F. & Kamil, K. T. Experimental analysis of Thermal Performance of a Solar Air Heater with a flat plate and metallic Fiber. J. Eng. Sci. Technol.17, 2049–2066 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mohammed, M. F., Eleiwi, M. A., Kamil, K. T. & Recovery, A. Experimental investigation of thermal performance of improvement a solar air heater with metallic fiber. Energy Sources, Part Utilization Environ. Eff.. 43, 2319–2338. 10.1080/15567036.2020.1833110 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Audsley, E. & Wheeler, J. The annual cost of machinery calculated using actual cash flows. J. Agric. Eng. Res.23, 189–201. 10.1016/0021-8634(78)90048-3 (1978). [Google Scholar]

- 61.EL khadraoui, A., Hamdi, I., Kooli, S. & Guizani, A. Drying of red pepper slices in a solar greenhouse dryer and under open sun: experimental and mathematical investigations. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol.52, 262–270. 10.1016/J.IFSET.2019.01.001 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shrivastava, V. & Kumar, A. Embodied energy analysis of the indirect solar drying unit. Int. J. Ambient Energy. 38, 280–285. 10.1080/01430750.2015.1092471 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 63.Komolafe, C. A. et al. Modelling of moisture diffusivity during solar drying of Locust beans with thermal storage material under forced and natural convection mode. Case Stud. Therm. Eng.15, 100542. 10.1016/J.CSITE.2019.100542 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Elavarasan, E., Natarajan, S. K., Bhanu, A. S., Anandu, A. & Senin, M. H. Experimental Investigation of Drying Cucumber in a double slope solar dryer under natural convection and Open Sun Drying. Lecture Notes Mech. Eng.PartF1, 41–52. 10.1007/978-981-16-4489-4_5 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elangovan, E. & Natarajan, S. K. Study of activation energy and moisture diffusivity of various dipping solutions of ivy gourd using solar dryer. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res.30, 996–1010. 10.1007/S11356-022-22248-W (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elangovan, E. & Natarajan, S. K. Experimental research of drying characteristic of red banana in a single slope direct solar dryer based on natural and forced convection. Food Technol. Biotechnol.59, 137–146. 10.17113/FTB.59.02.21.6876 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Anagh, S., Bhanu, E. E. & Sendhil Kumar Natarajan, A. A. Experimental investigation of Drying Kinetics of Poovan Banana under forced Convection Solar drying. Curr. Adv. Mech. Eng. 621–631. 10.1007/978-981-33-4795-3_56 (2021).

- 68.Elangovan, E. & Natarajan, S. K. Effect of pretreatments on drying of red dacca in a single slope solar dryer. J. Food Process Eng. 44. 10.1111/jfpe.13823 (2021).

- 69.Mukanema, M., Simate, I. N. & Energy Exergy and Economic Analysis of a mixed-mode natural convection solar tunnel dryer for Banana slices. SSRN Electron. J.10.2139/SSRN.4733986 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 70.Philip, N., Duraipandi, S. & Sreekumar, A. Techno-economic analysis of greenhouse solar dryer for drying agricultural produce. Renew. Energy. 199, 613–627. 10.1016/J.RENENE.2022.08.148 (2022). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.