Abstract

Activation of the sympathetic nervous system is observed in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients. This study investigates whether inhibiting the conversion of dopamine into noradrenaline by dopamine β‐hydroxylase (DβH) inhibition with BIA 21‐5337 improved right ventricular (RV) function or remodeling in pressure overload‐induced RV failure. RV failure was induced in male Wistar rats by pulmonary trunk banding (PTB). Two weeks after the procedure, PTB rats were randomized to vehicle (n = 8) or BIA 21‐5337 (n = 11) treatment. An additional PTB group treated with ivabradine (n = 11) was included to control for the potential heart rate‐reducing effects of BIA 21‐5337. A sham group (n = 6) received vehicle treatment. After 5 weeks of treatment, RV function was assessed by echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and invasive pressure–volume measurements before rats were euthanized. RV myocardium was analyzed to evaluate RV remodeling. PTB caused a fourfold increase in RV afterload which led to RV dysfunction, remodeling, and failure. Treatment with BIA 21‐5337 reduced adrenal gland DβH activity and 24‐h urinary noradrenaline levels confirming relevant physiological response to the treatment. At end‐of‐study, there were no differences in RV function or RV remodeling between BIA 21‐5337 and vehicle‐treated rats. In conclusion, treatment with BIA 21‐5337 did not have any beneficial—nor adverse—effects on the development of RV failure after PTB despite reduced adrenal gland DβH activity.

Keywords: animal study, dopamine β‐hydroxylase, noradrenaline, right heart failure, sympathetic nervous system

INTRODUCTION

Development of congestive heart failure is accentuated by an overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). Accordingly, β‐adrenoceptor blockade is a keystone in left heart failure treatment. 1 Multiple studies have confirmed increased sympathetic nerve activity in right heart failure caused, for example, by pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) or congenital heart disease. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 Additionally, chamber‐specific changes in β‐adrenergic receptor signaling occur in the failing right ventricle (RV) of PAH patients. 7 , 8 Based on PAH patients having a relatively fixed stroke volume and therefore being highly heart rate (HR) dependent to increase cardiac output (CO), 9 modulation of the SNS by β‐blockade is not recommended in the treatment of PAH and RV failure. However, the exact role of SNS activation in the development of right heart failure and the potential SNS modulation as treatment strategy in patients with right heart failure patients, still remain to be further clarified.

Dopamine β‐hydroxylase (DβH), the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of dopamine into noradrenaline, is an attractive target to modulate catecholaminergic signaling. 10 BIA 21‐5337 is a potent, noncompetitive, reversible inhibitor of human DβH under development by BIAL‐Portela & Cª, S.A. By attenuating the activity of the SNS, this approach could be an effective adjunctive therapy for adults with PAH (World Health Organization Pulmonary Hypertension Group I), potentially improving RV function, delaying disease progression and reducing the risk of PAH‐related hospitalizations.

Previous studies have shown reduced arrhythmogenicity and improved survival with DβH inhibition in rat with pulmonary hypertension and RV failure after monocrotaline intoxication. 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of long‐term therapeutic oral treatment with BIA 21‐5337 in rats with pressure overload‐induced RV failure caused by pulmonary trunk banding (PTB).

METHODS

Animals

Male Wistar rats from Janvier (France) were used for this study. Rats were housed in pairs and had free access to tap water and standard rat chow (Altromin). They were kept in a room with a 12‐h light‐dark cycle and a temperature of 23°C. All rats received humane care and were treated according to Danish national guidelines.

PTB

Rats were anesthetized, intubated, and ventilated. Chest was opened through a lateral thoracotomy, and carefully the pulmonary trunk was separated from the ascending aorta. The banding was made with a titanium clip, that was compressed around the pulmonary trunk to an inner diameter of 0.6 mm, and the thorax was then closed. To relieve postoperative pain, the rats were treated with buprenorphine (0.12 mg/kg) and carprofen (5 mg/kg) subcutaneously and additional buprenorphine in the drinking water (7.4 µg/mL) for 3 days. The same procedure was performed in sham rats except for the compression of the clip around the pulmonary trunk. 15

Study design

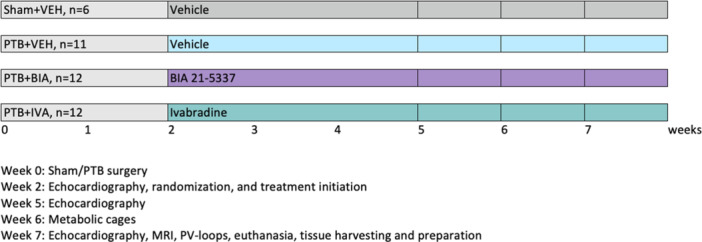

Rats were randomized to sham or PTB surgery. Two weeks after the procedure all rats underwent echocardiography, and PTB rats were randomized to vehicle treatment (PTB + VEH, n = 11) or BIA 21‐5337 treatment (PTB + BIA, n = 12). To control for effects due to HR reduction, a PTB group receiving ivabradine, which is an inhibitor of If, the so‐called “funny” ionic current that regulates pacemaker activity in the sinoatrial node, was also included (PTB + IVA, n = 12). Randomization was done by simple draw. Sham rats received vehicle treatment (Sham + VEH, n = 6). At week 5, a second echocardiography was performed, and at week 6, all rats were placed in individual metabolic cages for 48 h for urine collection; 24 h for adaptation and 24 h for urine sampling for subsequent evaluation of urinary catecholamines. At week 7, hemodynamic effects of PTB and the pharmacological interventions were evaluated over 3 consecutive days with echocardiography on the 1st day, MRI scan on the 2nd day, and invasive pressure‐volume measurements, euthanasia, and tissue samples collection on the 3rd day (Figure 1). To assess SNS activation in the PTB model over time, 24‐h urinary catecholamine levels were evaluated before PTB/sham surgery and 1, 5, and 7 weeks postsurgery in a small satellite study (sham, n = 6 and PTB, n = 5).

Figure 1.

Study design. Rats were randomized to sham or pulmonary trunk banding (PTB) surgery. After 2 weeks, PTB rats were further randomized to vehicle or active treatment with either BIA 21‐5337 or ivabradine. After additional 5 weeks, right ventricular function was evaluated and the rats were euthanized. The numbers of rats stated in the figure represent the number of rats randomized to the different experimental groups at week 2.

Pharmacological treatment

After baseline echocardiography (i.e., week 2), PTB animals were randomized to the different treatment groups. Vehicle (0.2% hydroxypropyl‐methyl cellulose), BIA 21‐5337, and ivabradine were administered by oral gavage once daily until the end of the study. The dosages of BIA 21‐5337 and ivabradine were 10 mg/kg/day. Compounds were administered at a volume of 2 mL/kg. Rats were weighed twice per week throughout the study period, and the dosage adjusted according to the most recent body weight. The last dosage was administered on the last day of evaluation approximately 2 h before euthanasia.

A detailed method section on echocardiography, metabolic cages, MRI, invasive pressure‐volume measurements, euthanasia, and samples collection, as well as histology, western blot analysis, and analyses of plasma, urine and adrenal gland samples is provided in the Supplementary material.

Statistical methods

Data was tested for normal distribution using QQ plots and/or histograms as well as Shapiro–Wilk normality test. Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as mean with (95% confidence intervals) and nonnormally distributed continuous variables as median with (interquartile range). For normally distributed data, an unpaired Student's t test was used for evaluation of statistical significance of differences between Sham + VEH and PTB + VEH using a significance level alpha equal to 0.05. Only if such test was rejected, additional one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to compare PTB groups was conducted with Dunnett post hoc multiplicity adjustment (PTB + BIA vs. PTB + VEH and PTB + IVA vs. PTB + VEH). For nonnormally distributed data, nonparametric tests corresponding to the approach described above were applied, that is, Mann–Whitney test for differences between Sham + VEH and PTB + VEH, and if rejected Kruskal–Wallis test with post hoc Dunn was used to evaluate effects of the treatments comparing each treatment group with the PTB + VEH group. For HR‐related readouts, a one‐way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis was applied for all four groups with post hoc Dunnett/Dunn using PTB + VEH as reference group. The Robust regression and Outlier removal method with Q = 1% was used for identification of possible outliers.

For urinary catecholamines and echocardiographic parameters additional two‐way ANOVAs were applied to consider the time effect within the statistical evaluation.

Categorical data were compared between treatment groups using Fisher's exact test following the same sequence described above: PTB + VEH versus Sham + VEH and if rejected, PTB + BIA versus PTB + VEH and PTB + IVA versus PTB + VEH with corresponding multiplicity adjustment.

All statistical analyses were performed with the use of Graphpad Prism 6 (Graphpad Software). p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Number of rats and mortality

In total, 44 rats were included in the study. Six rats underwent sham surgery and 38 rats underwent PTB surgery. One rat died during the PTB procedure, and two rats were found dead in the cage the day after the procedure, giving a peri‐operative mortality of 8% for the PTB procedure, and leaving 35 PTB rats for subsequent randomization to treatment. At randomization 2 weeks after the PTB/sham procedure, PTB rats had developed RV dysfunction evident by decreased tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) and CO. Increased RV end‐systolic area confirmed RV dilatation. There were no differences in CO, TAPSE, RV end‐systolic area, or body weight between rats subsequently randomized to vehicle, BIA 21‐5337, and ivabradine treatment, respectively (Supplementary material, Figure S1).

During the 5‐weeks treatment period, five PTB rats died; three from the vehicle‐treated group and one from each of the remaining treatment groups with no statistically significant difference in survival between the groups (p = 0.353). The rats were found dead in their cages, and all deaths were unexpected and sudden deaths with no preceding signs of cardiopulmonary deterioration. The dead rats were thoroughly examined, and signs of liver congestion were found in all, but no ascites or pleural effusion was seen. At end‐of‐study, six Sham + VEH rats, eight PTB + VEH rats, 11 PTB + BIA, and 11 PTB + IVA underwent hemodynamic evaluation and tissue harvesting. The mortality rates were similar to what has previously been reported with the same PTB method. 16

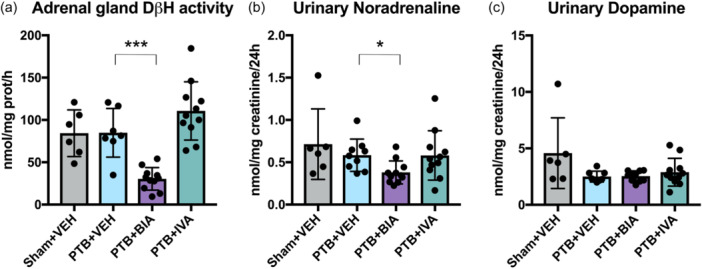

BIA 21‐5337 decreased DβH activity and urinary noradrenaline levels

Rats treated with BIA 21‐5337 and ivabradine depicted plasma concentrations of BIA 21‐5337 and ivabradine, respectively, confirming relevant exposure (Supplementary material, Table S1). In PTB rats, treatment with BIA 21‐5337 significantly decreased DβH activity in adrenal glands and 24‐h urinary noradrenaline compared with vehicle, confirming physiological response to the treatment (Figure 2). The PTB procedure itself had no effect on DβH activity in adrenal glands when compared with sham. Urinary noradrenaline and dopamine levels did not differ between sham and PTB‐operated animals at evaluation nor over time (Supplementary material, Figure S2). There were no differences in 24‐h urine creatinine levels between any of the groups.

Figure 2.

Adrenal gland dopamine β‐hydroxylase activity and urinary catecholamine levels. (a) Adrenal gland dopamine β‐hydroxylase activity in nmol octopamine/mg protein/h. (b) Noradrenaline levels (one outlier removed from the PTB + VEH group) and (c) Dopamine levels (two outliers removed from the PTB + VEH group and one outlier removed from the PTB + BIA group) from 24‐h urine corrected for creatinine levels. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

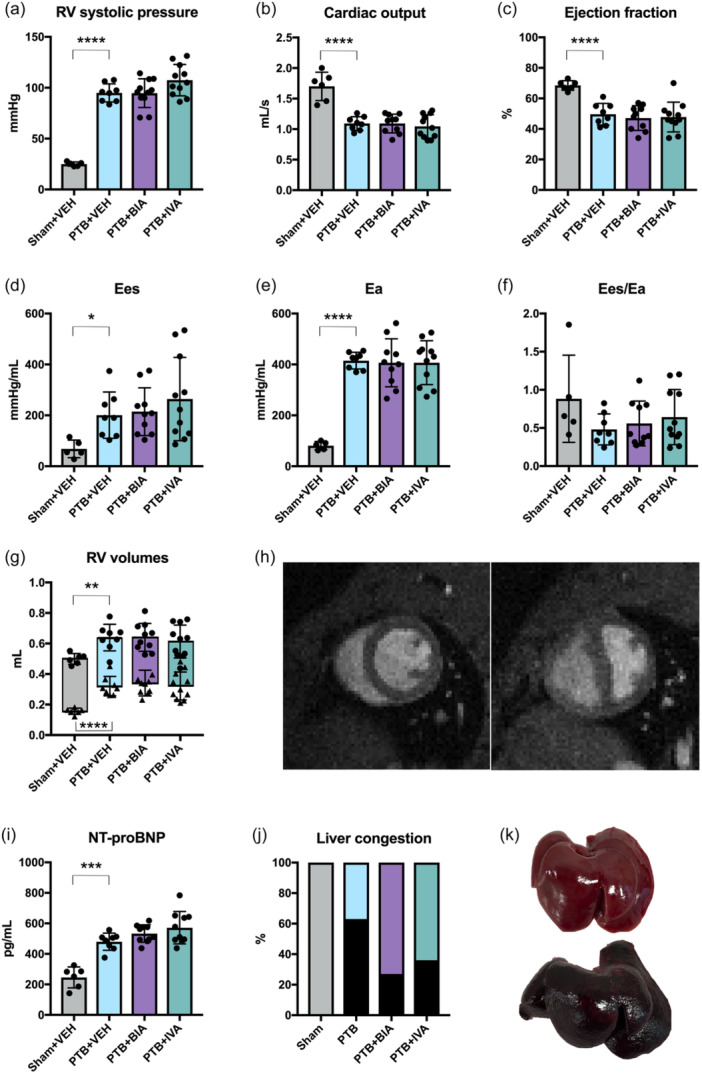

PTB caused RV failure that was unaltered with BIA 21‐5337 and ivabradine

At end‐of‐study, RV failure was evident in all rats subjected to the PTB procedure (Figure 3, Table 1). PTB rats showed an approximately fourfold increase in RV afterload assessed by RV systolic pressure and arterial elastance compared with sham‐operated rats. PTB also caused RV dilatation with increased RV end‐diastolic volume and end‐systolic volume. RV systolic dysfunction was evident by decreased CO, RV ejection fraction, and TAPSE. Despite increased contractility in PTB rats, there was a trend toward ventriculo‐arterial uncoupling (Ees/Ea) (p = 0.09). Furthermore, PTB increased RV end‐diastolic pressure and caused RV diastolic dysfunction. RV failure was further confirmed by increased plasma NT‐proBNP levels in the PTB rats compared with sham rats, and autopsy revealed signs of cardiac decompensation and backward failure including liver congestion in PTB rats. Supplementary autopsy data are listed in Table S2 in the supplement.

Figure 3.

Pulmonary trunk banding (PTB) caused right ventricular (RV) failure, that was not altered by treatment with BIA 21‐5337 or ivabradine. (a) RV systolic pressure. (b) RV cardiac outputb and (c) RV ejection fractionb measured by magnetic resonance imaging. (d) RV end‐systolic elastance (Ees)a,b. (e) Arterial elastance (Ea),a,b that is, RV afterload. (f) RV ventriculo‐pulmonary arterial coupling (Ees/Ea)a,b. (g) RV end‐diastolic (dots) and end‐systolic (triangles) volumes. (h) Representative short‐axis images of a sham rat (left) and a PTB rat (right). (i) Plasma NT‐proBNP levels were increased in PTB rats compared with sham rats. (j) Liver congestion (black bars) was observed only in PTB rats. (k) Example of a normal and healthy liver from a sham rat (upper) and a severely congested liver (nutmeg liver) from a PTB rat (lower). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. aData missing for one sham rat. bData missing for one PTB + BIA rat.

Table 1.

Hemodynamics and anatomical data.

| Sham + VEH (n = 6) | PTB + VEH (n = 8) | PTB + BIA (n = 11) | PTB + IVA (n = 11) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemodynamics | ||||

| Heart rate (bpm) a | 322 (299;346) | 306 (288;325) | 289 (272;306) | 256 (240;272)^^^ |

| MAP (mmHg) b , c | 130 (118;142) | 124 (112;137) | 124 (112;136) | 120 (110;129) |

| TAPSE (mm) | 2.8 (2.1;3.4) | 1.7 (1.4;1.9)*** | 1.8 (1.5;2.1) | 1.5 (1.3;1.6) |

| Tricuspid regurgitation, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (75) | 9 (82) | 5 (45) |

| RV stroke volume (mL) a | 0.33 (0.26;0.40) | 0.23 (0.21;0.24)** | 0.25 (0.22;0.27) | 0.27 (0.24;0.30)† |

| RV dP/dt maximum (mmHg/s) b | 1255 (1080;1430) | 3896 (3312;4480)**** | 3880 (3395;4364) | 4457 (3873;5041) |

| RV dP/dt minimum (mmHg/s) b | −1033 (−1299;−767) | −3223 (−3510;−2935)**** | −3347 (−3813;−2882) | −3608 (−4222;−2993) |

| RV end‐diastolic pressure (mmHg) b | 2.6 (0.7;4.6) | 5.5 (3.4;7.6)* | 5.4 (4.1;6.6) | 6.5 (5.0;7.9) |

| RV Eed (mmHg/mL) a , b , c | 3.6 (1.8;6.2) | 8.1 (6.6;11.0)* | 9.5 (5.6;14.6) | 8.6 (8.2;13.1) |

| RV E/Éd | 6 (1;11) | 19 (13;25)** | 17 (14;21) | 19 (15;22) |

| Anatomical data | ||||

| Body weight (g) | 368 (348;389) | 365 (341;388) | 354 (330;379) | 363 (342;383) |

| RV weight (g) | 0.21 (0.18;0.24) | 0.51 (0.46;0.56)**** | 0.51 (0.48;0.54) | 0.49 (0.45;0.53) |

| LV + S weight (g) | 0.78 (0.74;0.82) | 0.84 (0.73;0.95) | 0.87 (0.79;0.96) | 0.85 (0.81;0.89) |

| RV weight/tibia length (mg/mm) | 4.9 (4.3;5.5) | 11.9 (10.7;13.1)**** | 11.9 (11.2;12.6) | 11.5 (10.6;12.5) |

| Ascites and pleural effusion, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (37) | 1 (9) | 1 (9) |

Abbreviations: ANOVA, analysis of variance; dP/dt, delta pressure/delta time; Eed, end‐diastolic elastance; LV + S, left ventricle plus septum; MAP, mean systemic arterial blood pressure; PTB, pulmonary trunk banding; RV, right ventricle/ventricular; TAPSE, tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion.

Data missing for one PTB + BIA rat.

Data missing for one Sham + VEH rat.

Data missing for one PTB + VEH rat.

Data missing for two Sham + VEH rats.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

p < 0.0001 versus Sham + VEH.

p < 0.001 versus PTB + VEH.

One‐way ANOVA (PTB groups), p = 0.054. Adjusted p value PTB + IVA versus PTB + VEH, p = 0.03.

There were no effects of BIA 21‐5337 or ivabradine treatment on RV afterload, although there was a trend toward increased RV systolic pressure in the PTB + IVA group (adjusted p = 0.0976). Likewise, neither of the pharmacological treatments had any effects on plasma NT‐proBNP, RV dilatation, or RV systolic function at end‐of‐study (Figure 3). Development of RV failure over time was also unaltered with the treatments (Supplementary material, Figure S3). Liver congestion was less frequent in rats treated with BIA 21‐5337 or ivabradine as was ascites and pleural effusions, although these results did not reach statistical significance (Table 1, Figure 3). Treatment with ivabradine decreased HR compared with vehicle. Due to an increase in RV stroke volume (strong trend), PTB + IVA rats were able to maintain CO. BIA 21‐5337 treatment did not have a significant effect on HR in the PTB model (Table 1).

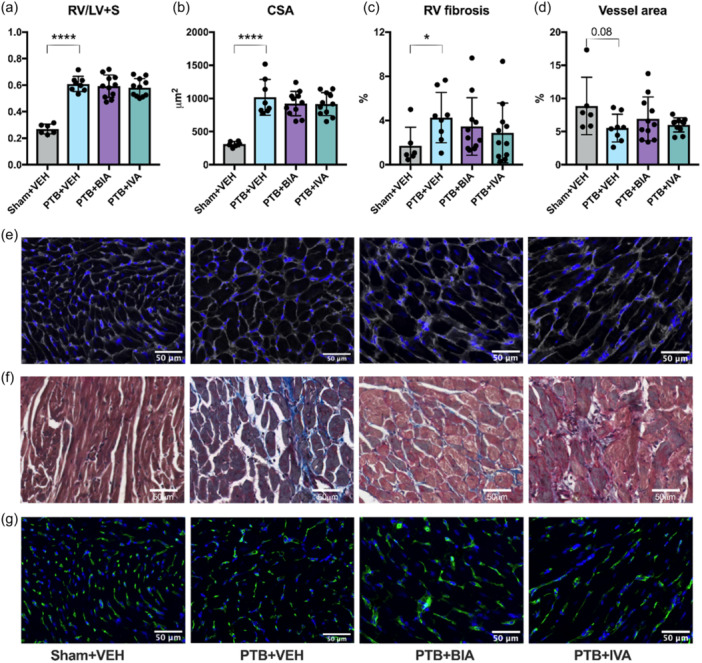

Effects on RV remodeling

The increased afterload in PTB rats caused RV hypertrophy, here assessed as the weight of the RV corrected for the weight of the LV plus the septum (Fulton index) (Figure 4). RV cardiomyocyte cross‐sectional area was also increased in PTB rats compared with sham‐operated rats, and the RV of PTB rats had a higher fraction of fibrosis. The hypertrophied RV also showed some degree of capillary rarefaction (reduced vessel density) in PTB rats compared with sham‐operated rats, although not statistically significant. Treatment with BIA 21‐5337 and ivabradine had no effects on RV remodeling after PTB.

Figure 4.

Pulmonary trunk banding (PTB) caused right ventricular (RV) hypertrophy and fibrosis. (a) RV weight divided by the weight of the left ventricle (LV) plus the septum (LV + S). (b) RV cardiomyocyte cross‐sectional area (CSA). (c) RV fibrosis. (d) Capillary density. (e) Representative images of wheat germ agglutinin stained samples from each the four experimental groups used for CSA measurements. (f) Representative images of Masson's trichrome stained samples used for quantification of fibrosis. (g) Representative images of Lectin‐stained samples used for assessment of capillary rarefaction. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001.

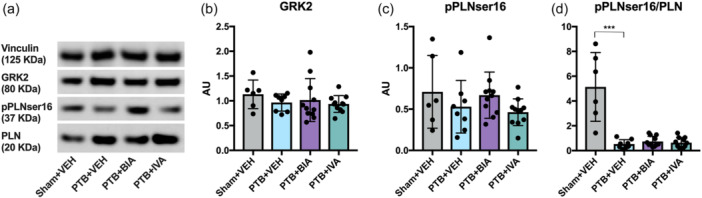

β‐adrenergic receptor signaling

Protein expression of G‐protein‐coupled receptor kinase 2 and phospholamban phosphorylated at the protein kinase A site Ser16 was not changed in PTB rats compared with sham, but an increase in total phospholamban led to a decrease in the phosphorylated phospholamban to total phospholamban ratio (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

β‐adrenergic receptor signaling. (a) Representative Western Blots of the house‐keeping gene vinculin, G‐protein‐coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2), phospholamban (PLN) phosphorylated at the protein kinase A site Ser16 (pPLNser16), and total PLN. (b) Quantification of GRK2 protein expression in right ventricular cardiomyocytes normalized to vinculin. (c) Quantification of pPLNser16 normalized to vinculin. (d) pPLNser16 normalized to total PLN. ***p < 0.001.

Despite impeded noradrenaline production in the BIA 21‐5337 treated PTB rats (Figure 2), expression of hallmark proteins of β‐adrenergic signaling did not change with the treatment (Figure 5). This lack of further downstream effects on β‐adrenergic receptor signaling may explain why no beneficial effects of treatment with BIA 21‐5337 on the development of RV failure were observed despite lower noradrenaline production.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the effects of treatment with BIA 21‐5337 and ivabradine in a rat model of pressure overload‐induced RV failure. We show that:

-

−

Treatment with BIA 21‐5337 reduced adrenal gland DβH activity and 24‐h urinary noradrenaline levels, but did not affect the development of RV failure after PTB.

-

−

Treatment with ivabradine significantly lowered HR compared with vehicle, nevertheless CO was maintained due to an increase in RV stroke volume. These changes had no impact on the development of RV failure after PTB.

-

−

None of the treatments showed adverse effects.

RV failure in an experimental set‐up

Many different animal models can be used to investigate RV failure. 17 With the PTB model used in this study, we were able to create a consistent phenotype of sustained pressure overload‐induced RV failure with decreased CO and clinical signs of RV failure. These included signs of backward failure with increased liver weight and liver congestion as well as ascites and pleural effusions. Thus, the development of RV failure in the PTB model showed many and important common characteristics with clinical RV failure. 18 , 19 The PTB rats also showed decreased CO and RV dilatation consistent with the maladaptive stage of RV failure in patients with pulmonary hypertension. 20 We did not observe increased levels of 24‐h urinary noradrenaline in the PTB model. In the monocrotaline rat model of pulmonary hypertension and RV failure, plasma noradrenaline is higher compared with sham 21 but with no difference in phosphorylation of main target proteins of protein kinase A. 22 Similarly, we see no difference in phosphorylated phospholamban between vehicle‐treated PTB rats and the sham group. We do, however, see a decrease in the phosphorylated phospholamban normalized to total phospholamban ratio, that may indicate a downregulation of β‐adrenergic receptor density and signaling due to sympathetic overdrive. 23 In contrast to our findings, total phospholamban expression is decreased in the monocrotaline model, 24 but inherent differences in disease mechanisms between the models likely explain this discrepancy.

Effects of DβH inhibition

DβH catalyzes the conversion of dopamine to noradrenaline and is expressed in adrenal glands but also in the heart. 25 Importantly, DβH activity is the rate‐limiting step in noradrenaline formation in general. In this study, DβH inhibition decreased adrenal gland DβH activity by approximately 73% and urinary noradrenaline excretion by approximately 39%, while there was no change in urinary dopamine excretion. In previous studies, the DβH inhibitor etamicastat has been shown to reduce adrenal gland DβH activity by a similar 62%–83%, 10 , 26 which led to a decrease in urinary noradrenaline excretion of 80% in spontaneously hypertensive rats. 26 This congruence with previous data confirms adequate dosing in present study.

Previous studies with BIA 21‐5337 have shown a HR‐reducing potential of the compound (unpublished data). This was not reproduced in the PTB model, where there was no effect of BIA 21‐5337 on HR. These results are consistent with what have been observed with DβH inhibition in spontaneously hypertensive rats in some studies, 10 , 27 although not consistent across all studies. 26 The discrepancy may relate to the animal model used as well as the technique used for the measurement of HR (i.e., conscious telemetry vs. anaesthetized invasive measurements).

In previous studies, pharmacological DβH inhibition‐driven sympathetic downregulation, although not altering high RV pressure, yielded a lower proarrhythmic cardiac tissue decreasing the incidence of cardiac arrhythmias and improved survival in the monocrotaline rat model. 11 , 13 , 14 These results were not reproduced in the PTB model, where DβH inhibition did not lead to a statistically significant improvement in survival. The discrepancy may be explained by DβH inhibition possibly interacting with the myocarditis component of the monocrotaline model. Electrophysiological properties were not evaluated in the present study.

Other strategies to modulate SNS activation in pulmonary hypertension include traditional β‐adrenoceptor blockade but also the emerging field of neuroinflammation manipulation. While preclinical studies investigating the effects of β‐blockade in various animal models of pulmonary hypertension and RV failure have shown contradictory results, 21 , 22 , 28 , 29 , 30 treatment with bisoprolol failed to improve RV ejection fraction in patients with stable idiopathic PAH. 31 There is an increased awareness of how the deleterious effects of SNS overdrive in pulmonary hypertension result from imbalances in a complex CNS‐cardio‐pulmonary interplay. Changes in brain areas that control for example autonomic functions have been demonstrated in patients with PAH, 32 and the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus plays a central role in regulating SNS activity. 33 Neuroinflammation in the brain and thoracic spinal cord and activation of afferent cardiopulmonary signaling exaggerating SNS stress on the RV have been demonstrated in preclinical models of pulmonary hypertension, 34 , 35 and human PAH. 35 Targeting these central neuronal pathways and neuroinflammatory processes represents an interesting additional strategy of SNS modulation in pulmonary hypertension and RV failure. 35 , 36 , 37

Effects of ivabradine

A PTB group treated with ivabradine was included in the study to control for the potential HR‐reducing effects of BIA 21‐5337. Ivabradine reduced HR by the expected 20% similar to previous studies using the same dosage. 38 Due to an increase in stroke volume, CO was maintained in ivabradine‐treated animals. Contrary to other studies, 38 ivabradine did not show any beneficial effects on RV function or the development of RV failure in our study. This discrepancy may be explained by several factors including differences in treatment duration, different rat strains, and different banding severities.

HR reduction by ivabradine has shown beneficial effects in patients with Group I and Group III pulmonary hypertension. 39 , 40 However, these patients presented with sinus tachycardia as opposed to the most commonly used animal models of pulmonary hypertension and RV failure that usually show unchanged or even reduced HR compared with sham. 38 , 41 This physiological difference may limit the translatability of effects of HR‐reducing interventions to the clinical setting.

Extra‐cardiac manifestations of RV failure

RV failure predispose to hepatic congestion through a backward failure effect. Accordingly, congestive hepatopathy is observed in both animal models of RV failure 42 , 43 , 44 and patients with severe heart failure. 45 Other extra‐cardiac manifestations of RV failure include ascites and pleural effusions. Although not significant, we did observe less liver congestion, ascites, and pleural effusions as well as fewer unexpected deaths in PTB rats treated with BIA 21‐5337 and ivabradine compared with vehicle‐treated PTB rats. However, the sample sizes do not allow to draw conclusions from these results.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths. First, we used a robust and highly reproducible model of pressure overload‐induced RV failure. The PTB model is a model of isolated RV failure that, contrary to, for example, the Sugen‐Hypoxia or Monocrotaline models of pulmonary hypertension and secondary RV failure, allows for investigation of direct effects of an intervention on the failing RV. Second, we used a broad range of clinically relevant methods to evaluate RV function including MRI, which is considered gold standard for evaluation of RV volumes, and PV loops to obtain load‐independent measures of RV function. Third, treatment was initiated after RV dysfunction had developed, thus mimicking the clinical setting of patients presenting with RV failure. Conversely, another group of patients may present with early pulmonary hypertension and only little affection of the RV. Future studies investigating SNS modulation as a preventive strategy could add to our understanding of the therapeutic potential of SNS‐targeted therapies in this early phase of the disease.

Despite relevant development of RV failure with several phenotypic characteristics similar to those seen in RV failure of, for example, PAH patients, we did not observe an increase in urinary noradrenaline. Urinary catecholamines is a measure of whole‐body SNS. However, the heterogeneity of regional sympathetic nervous activity patterns must be considered since the SNS outflow to individual organs is not uniform in different disease states. This general measurement of overall sympathetic nervous activity is therefore unspecific and may not represent the real end‐organ effects of the SNS. 46 , 47 Future studies may include noninvasive cardiac imaging techniques with norepinephrine analogs for evaluation of SNS hyperactivation in RV failure and pulmonary hypertension and assessment of possible effects of therapeutic interventions targeting the sympathetic overdrive. 48

We only included male Wistar rats in this study. Ideally, both male and female rats should be included in a study like ours. However, the hormonal fluctuations in female rats and the differences in body size between male and female rats would necessitate the inclusion of more rats. Accordingly, only male rats were used for this explorative study. It has previously been shown that the hemodynamic response to the PTB surgery is similar between male and female Wistar rats, but that male rats develop more RV hypertrophy and express a different gene pattern compared with females. 49 Accordingly, sex differences do play a role in the development of RV failure, and future studies should address these sex‐specific effects.

Hemodynamic assessments were performed in anaesthetized rats. To minimize the influence of the anesthesia on the measurements, a strict and well‐tested protocol was followed in all rats. Finally, interspecies variations should be taken into considerations when interpreting our results and may limit translation of our findings.

Future perspectives

RV failure remains a sign of poor prognosis regardless of its underlying cause. So far, no treatment has shown to directly improve or protect the failing RV, and current strategies aim at treating the primary disease. However, the RV may continue to deteriorate despite reductions in afterload, 50 emphasizing the need for direct RV protective treatment options. Modulating the SNS remains an intriguing strategy, that should be investigated further in future studies.

DβH inhibition by BIA 21‐5337 treatment reduced enzyme activity in rats with RV failure after PTB. The reduction in noradrenaline production, however, did not lead to an improvement in RV function or remodeling, possibly due to the lack of downstream effects on the β‐adrenergic signaling pathways. Neither did HR reduction by ivabradine alter the development of RV failure after PTB. We did not observe any adverse effects of the treatments, and the potential role of SNS modulation as an RV failure treatment strategy should be investigated further by future research.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Stine Andersen: Methodology; formal analysis; investigation; data curation; writing—original draft; project administration. Julie Sørensen Axelsen: Methodology; investigation; writing—review and editing. Anders Hammer Nielsen‐Kudsk: Investigation; writing—review and editing. Janne Schwab: Investigation; writing—review and editing. Caroline Damsgaard Jensen: Investigation; writing—review and editing. Steffen Ringgaard: Software; methodology; writing—review and editing. Asger Andersen: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing; supervision. Rowan Smal: Methodology; formal analysis; investigation; writing—review and editing. Aida Llucià‐Valldeperas: Methodology; formal analysis; investigation; writing—review and editing. Frances Handoko de Man: Conceptualization; writing—review and editing; supervision; project administration. Bruno Igreja: Conceptualization; methodology; formal analysis; resources; writing—review and editing; supervision; project administration; funding acquisition. Nuno Pires: Conceptualization; methodology; formal analysis; resources; writing—review and editing; supervision; project administration; funding acquisition.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

B. I. and N. P were employees of BIAL‐Portela & Cª, S.A. (the sponsor of the study) at the time of the study. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

ETHICS STATEMENT

All parts of the protocol involving animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Ethics Review Board and conducted in accordance with Danish law for animal research (authorization number 2021‐15‐0201‐00928, Danish Ministry of Justice).

Supporting information

Supporting information.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by BIAL‐Portela & Cª, S.A. The authors would like to thank Ana Dias, MSc, Cátia Aires, PhD, Carlos Lopes, MSc, and Diana Ribeiro, PhD for their technical contribution.

Andersen S, Axelsen JS, Nielsen‐Kudsk AH, Schwab J, Jensen CD, Ringgaard S, Anderse n A, Smal R, Llucià‐Valldeperas A, Handoko de Man F, Igreja B, Pires N. Effects of dopamine β‐hydroxylase inhibition in pressure overload‐induced right ventricular failure. Pulm Circ. 2024;14:e70008. 10.1002/pul2.70008

REFERENCES

- 1. McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, Böhm M, Burri H, Butler J, Čelutkienė J, Chioncel O, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Crespo‐Leiro MG, Farmakis D, Gilard M, Heymans S, Hoes AW, Jaarsma T, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lam CSP, Lyon AR, McMurray JJV, Mebazaa A, Mindham R, Muneretto C, Piepoli MF, Price S, Rosano GMC, Ruschitzka F, Skibelund AK. 2021 ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: developed by the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). With the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur J Heart Fail. 2022;24(1):4–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bristow MR, Minobe W, Rasmussen R, Larrabee P, Skerl L, Klein JW, Anderson FL, Murray J, Mestroni L, Karwande SV. Beta‐adrenergic neuroeffector abnormalities in the failing human heart are produced by local rather than systemic mechanisms. J Clin Invest. 1992;89(3):803–815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nootens M, Kaufmann E, Rector T, Toher C, Judd D, Francis GS, Rich S. Neurohormonal activation in patients with right ventricular failure from pulmonary hypertension: relation to hemodynamic variables and endothelin levels. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26(7):1581–1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Velez‐Roa S, Ciarka A, Najem B, Vachiery JL, Naeije R, van de Borne P. Increased sympathetic nerve activity in pulmonary artery hypertension. Circulation. 2004;110(10):1308–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ciarka A, Doan V, Velez‐Roa S, Naeije R, van de Borne P. Prognostic significance of sympathetic nervous system activation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(11):1269–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bolger AP, Sharma R, Li W, Leenarts M, Kalra PR, Kemp M, Coats AJS, Anker SD, Gatzoulis MA. Neurohormonal activation and the chronic heart failure syndrome in adults with congenital heart disease. Circulation. 2002;106(1):92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rain S, Handoko ML, Trip P, Gan CTJ, Westerhof N, Stienen GJ, Paulus WJ, Ottenheijm CAC, Marcus JT, Dorfmüller P, Guignabert C, Humbert M, MacDonald P, dos Remedios C, Postmus PE, Saripalli C, Hidalgo CG, Granzier HL, Vonk‐Noordegraaf A, van der Velden J, de Man FS. Right ventricular diastolic impairment in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation. 2013;128(18):2016–2025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bristow MR, Ginsburg R, Umans V, Fowler M, Minobe W, Rasmussen R, Zera P, Menlove R, Shah P, Jamieson S. Beta 1‐ and beta 2‐adrenergic‐receptor subpopulations in nonfailing and failing human ventricular myocardium: coupling of both receptor subtypes to muscle contraction and selective beta 1‐receptor down‐regulation in heart failure. Circ Res. 1986;59(3):297–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Provencher S, Chemla D, Hervé P, Sitbon O, Humbert M, Simonneau G. Heart rate responses during the 6‐minute walk test in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(1):114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bonifacio MJ, Sousa F, Neves M, Palma N, Igreja B, Pires NM, Wright LC, Soares‐da‐Silva P. Characterization of the interaction of the novel antihypertensive etamicastat with human dopamine‐beta‐hydroxylase: comparison with nepicastat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;751:50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pires N, Igreja B, Magalhaes L, Bonifácio MJ, Chevalier E, Soares‐da‐Silva P. Zamicastat decreases cardiac arrhythmias in a rat model of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(suppl 64):1483. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Igreja B, Pires N, Moser P, Soares‐da‐Silva P. Effect of chronic treatment with zamicastat on right ventricle pressure overload in the rat monocrotaline lung injury model of pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J. 2017;31(S1):1070.7. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Moura E, Costa C, Igreja B, Pires P, Batalha V, Bonifácio M, Soares‐da‐Silva P. Effect of zamicastat, a dopamine beta‐hydroxylase inhibitor, on the monocrotaline rat model of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(suppl 64):3560. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pires NIB, Magalhães L, Bonifácio MJ, Chevalier C, Soares‐da‐Silva P. Sympathetic down‐regulation with zamicastat reduces arrhythmogenicity in isolated hearts from rats with pulmonary hypertension 2020.

- 15. Andersen S, Schultz JG, Holmboe S, Axelsen JB, Hansen MS, Lyhne MD, Nielsen‐Kudsk JE, Andersen A. A pulmonary trunk banding model of pressure overload induced right ventricular hypertrophy and failure. J Vis Exp. 2018;(141). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Axelsen JS, Nielsen‐Kudsk AH, Schwab J, Ringgaard S, Nielsen‐Kudsk JE, de Man FS, Andersen A, Andersen S. Effects of empagliflozin on right ventricular adaptation to pressure overload. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023;10:1302265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Andersen A, van der Feen DE, Andersen S, Schultz JG, Hansmann G, Bogaard HJ. Animal models of right heart failure. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2020;10(5):1561–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Borgdorff MAJ, Dickinson MG, Berger RMF, Bartelds B. Right ventricular failure due to chronic pressure load: what have we learned in animal models since the NIH working group statement? Heart Fail Rev. 2015;20(4):475–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vonk‐Noordegraaf A, Haddad F, Chin KM, Forfia PR, Kawut SM, Lumens J, Naeije R, Newman J, Oudiz RJ, Provencher S, Torbicki A, Voelkel NF, Hassoun PM. Right heart adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25):D22–D33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vonk Noordegraaf A, Chin KM, Haddad F, Hassoun PM, Hemnes AR, Hopkins SR, Kawut SM, Langleben D, Lumens J, Naeije R. Pathophysiology of the right ventricle and of the pulmonary circulation in pulmonary hypertension: an update. Eur Respir J. 2018;53(1):1801900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Usui S, Yao A, Hatano M, Kohmoto O, Takahashi T, Nagai R, Kinugawa K. Upregulated neurohumoral factors are associated with left ventricular remodeling and poor prognosis in rats with monocrotaline‐induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circ J. 2006;70(9):1208–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Man FS, Handoko ML, van Ballegoij JJM, Schalij I, Bogaards SJP, Postmus PE, van der Velden J, Westerhof N, Paulus WJ, Vonk‐Noordegraaf A. Bisoprolol delays progression towards right heart failure in experimental pulmonary hypertension. Circ Heart Fail. 2012;5(1):97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bristow MR, Ginsburg R, Minobe W, Cubicciotti RS, Sageman WS, Lurie K, Billingham ME, Harrison DC, Stinson EB. Decreased catecholamine sensitivity and β‐adrenergic‐receptor density in failing human hearts. N Engl J Med. 1982;307(4):205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fowler ED, Drinkhill MJ, Norman R, Pervolaraki E, Stones R, Steer E, Benoist D, Steele DS, Calaghan SC, White E. Beta1‐adrenoceptor antagonist, metoprolol attenuates cardiac myocyte Ca(2+) handling dysfunction in rats with pulmonary artery hypertension. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2018;120:74–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neumann J, Hofmann B, Dhein S, Gergs U. Role of dopamine in the heart in health and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):5042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pires NM, Igreja B, Moura E, Wright LC, Serrão MP, Soares‐da‐Silva P. Blood pressure decrease in spontaneously hypertensive rats folowing renal denervation or dopamine β‐hydroxylase inhibition with etamicastat. Hypertension Res. 2015;38(9):605–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Igreja B, Pires NM, Bonifácio MJ, Loureiro AI, Fernandes‐Lopes C, Wright LC, Soares‐da‐Silva P. Blood pressure‐decreasing effect of etamicastat alone and in combination with antihypertensive drugs in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension Res. 2015;38(1):30–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andersen S, Schultz JG, Andersen A, Ringgaard S, Nielsen JM, Holmboe S, Vildbrad MD, de Man FS, Bogaard HJ, Vonk‐Noordegraaf A, Nielsen‐Kudsk JE. Effects of bisoprolol and losartan treatment in the hypertrophic and failing right heart. J Card Fail. 2014;20(11):864–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bogaard HJ, Natarajan R, Mizuno S, Abbate A, Chang PJ, Chau VQ, Hoke NN, Kraskauskas D, Kasper M, Salloum FN, Voelkel NF. Adrenergic receptor blockade reverses right heart remodeling and dysfunction in pulmonary hypertensive rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(5):652–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ishikawa M, Sato N, Asai K, Takano T, Mizuno K. Effects of a pure alpha/beta‐adrenergic receptor blocker on monocrotaline‐induced pulmonary arterial hypertension with right ventricular hypertrophy in rats. Circ J. 2009;73(12):2337–2341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Campen JSJA, de Boer K, van de Veerdonk MC, van der Bruggen CEE, Allaart CP, Raijmakers PG, Heymans MW, Marcus JT, Harms HJ, Handoko ML, de Man FS, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Bogaard HJ. Bisoprolol in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: an explorative study. Eur Respir J. 2016;48(3):787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Roy B, Vacas S, Ehlert L, McCloy K, Saggar R, Kumar R. Brain structural changes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Neuroimaging. 2021;31(3):524–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Patel KP. Role of paraventricular nucleus in mediating sympathetic outflow in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2000;5(1):73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Vaillancourt M, Chia P, Medzikovic L, Cao N, Ruffenach G, Younessi D, Umar S. Experimental pulmonary hypertension is associated with neuroinflammation in the spinal cord. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Razee A, Banerjee S, Hong J, Magaki S, Fishbein G, Ajijola OA, Umar S. Thoracic spinal cord neuroinflammation as a novel therapeutic target in pulmonary hypertension. Hypertension. 2023;80(6):1297–1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sharma RK, Oliveira AC, Kim S, Rigatto K, Zubcevic J, Rathinasabapathy A, Kumar A, Lebowitz JJ, Khoshbouei H, Lobaton G, Aquino V, Richards EM, Katovich MJ, Shenoy V, Raizada MK. Involvement of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of monocrotaline‐induced pulmonary hypertension. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1156–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oliveira AC, Karas MM, Alves M, He J, de Kloet AD, Krause EG, Richards EM, Bryant AJ, Raizada MK. ACE2 overexpression in corticotropin‐releasing‐hormone cells offers protection against pulmonary hypertension. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1223733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ishii R, Okumura K, Akazawa Y, Malhi M, Ebata R, Sun M, Fujioka T, Kato H, Honjo O, Kabir G, Kuebler WM, Connelly K, Maynes JT, Friedberg MK. Heart rate reduction improves right ventricular function and fibrosis in pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2020;63(6):843–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Correale M, Brunetti ND, Montrone D, Totaro A, Ferraretti A, Ieva R, di Biase M. Functional improvement in pulmonary arterial hypertension patients treated with ivabradine. J Card Fail. 2014;20(5):373–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rossi R, Coppi F, Sgura FA, Monopoli DE, Arrotti S, Talarico M, Boriani G. Effects of ivabradine on right ventricular systolic function in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cor pulmonale. Am J Cardiol. 2023;207:179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Andersen S, Axelsen JB, Ringgaard S, Nyengaard JR, Hyldebrandt JA, Bogaard HJ, de Man FS, Nielsen‐Kudsk JE, Andersen A. Effects of combined angiotensin II receptor antagonism and neprilysin inhibition in experimental pulmonary hypertension and right ventricular failure. Int J Cardiol. 2019;293:203–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Axelsen JS, Andersen S, Ringgaard S, Smal R, Lluciá‐Valldeperas A, Nielsen‐Kudsk JE, de Man FS, Andersen A. Right ventricular diastolic adaptation to pressure overload in different rat strains. Physiol Rep. 2024;12(13):e16132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gewehr DM, Giovanini AF, Mattar BA, Agulham AP, Bertoldi AS, Nagashima S, Kubrusly FB, Kubrusly LF. Congestive hepatopathy secondary to right ventricular hypertrophy related to monocrotaline‐induced pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(21):11891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Hamberger F, Legchenko E, Chouvarine P, Mederacke YS, Taubert R, Meier M, Jonigk D, Hansmann G, Mederacke I. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and consecutive right heart failure lead to liver fibrosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:862330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Xanthopoulos A, Starling RC, Kitai T, Triposkiadis F. Heart failure and liver disease. JACC Heart Fail. 2019;7(2):87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Vaz M, Jennings G, Turner A, Cox H, Lambert G, Esler M. Regional sympathetic nervous activity and oxygen consumption in obese normotensive human subjects. Circulation. 1997;96(10):3423–3429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Esler M, Jennings G, Leonard P, Sacharias N, Burke F, Johns J, Blombery P. Contribution of individual organs to total noradrenaline release in humans. Acta Physiol Scand, Suppl. 1984;527:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zelt JGE, deKemp RA, Rotstein BH, Nair GM, Narula J, Ahmadi A, Beanlands RS, Mielniczuk LM. Nuclear imaging of the cardiac sympathetic nervous system. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13(4):1036–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Labazi H, Axelsen JB, Hillyard D, Nilsen M, Andersen A, MacLean MR. Sex‐dependent changes in right ventricular gene expression in response to pressure overload in a rat model of pulmonary trunk banding. Biomedicines. 2020;8(10):430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van de Veerdonk MC, Kind T, Marcus JT, Mauritz GJ, Heymans MW, Bogaard HJ, Boonstra A, Marques KMJ, Westerhof N, Vonk‐Noordegraaf A. Progressive right ventricular dysfunction in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension responding to therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(24):2511–2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information.