Abstract

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies are characterized by chronic inflammation of skeletal muscle. The main subtypes of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies include dermatomyositis, polymyositis, and necrotizing autoimmune myopathies. Dermatomyositis is characterized by symmetrical proximal muscle weakness, distinctive skin lesions, and systemic manifestations. Dermatomyositis commonly presents with elevated creatinine kinase levels. However, we report a case of a 19-year-old female presenting with dermatomyositis positive for anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibodies presenting with classic signs and symptoms like progressive proximal muscle weakness, dysphagia, hyperpigmented rash, and Gottron’s papules but had severe inflammatory myopathy on muscle biopsy and normal creatinine kinase levels. This case emphasizes an atypical presentation of dermatomyositis where she did not have amyopathic dermatomyositis despite having a positive anti-melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody and normal creatinine kinase. This underscores the importance of history and physical examination despite contradictory laboratory results.

Keywords: Dermatomyositis, creatinine kinase, myositis-specific antibodies, autoimmune myopathies

Introduction

Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies (IIMs) encompass a diverse group of autoimmune disorders marked by chronic inflammation of skeletal muscles and present with a range of clinical manifestations. 1 The main subtypes of IIMs include dermatomyositis (DM), polymyositis, inclusion-body myositis (IBM), anti-synthetase syndrome, and immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy. 1 DM is a rare disorder with a prevalence of 13 per 1000,000 people. 2 It is typically characterized by symmetrical weakness in proximal muscles, skin manifestations, and various other systemic manifestations, such as interstitial lung disease (ILD), dysphagia, and cardiac abnormalities. 3 Patients with DM usually present with elevated muscle enzymes such as creatinine kinase (CK), but in 10%–26% of patients, they can also present with normal CK.4–6 In this report, we describe a patient with normal CK and otherwise typical clinical and histopathological features of DM. In this report, we describe an atypical presentation of histopathologically classified severe DM with positive anti-small ubiquitin-like modifier 1 (anti-SAE1) and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 antibody (MDA5 antibody), found to have normal CK levels despite severe disease progression.

Case presentation

A 19-year-old Hispanic female with no significant past medical history presented with a 4-month history of proximal muscle weakness and an associated hyperpigmented rash on the sun-exposed areas of the face, neck, and upper chest. Muscle weakness progressively worsened, ultimately affecting the oropharyngeal muscles and causing dysphagia.

Physical examination revealed a hyperpigmented rash to the forehead, chin, and upper chest consistent with the shawl sign and Gottron’s papules on the dorsal aspect of the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints bilaterally. The patient was noted to have decreased motor strength of 3/5 symmetrically in proximal muscle groups of the upper and lower extremities and neck flexors and had decreased 1 + reflexes.

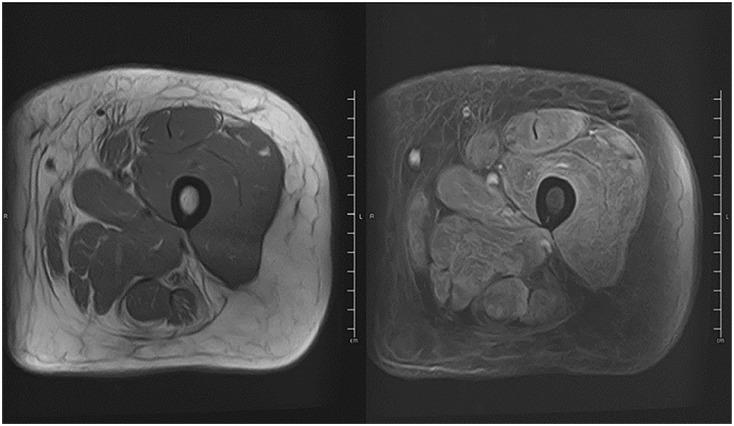

Laboratory tests revealed mildly elevated inflammatory markers like erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 39 mm (Reference range: 0–20 mm), C-reactive protein: 8.9 mg/L (0–3 mg/L), and elevated muscle enzymes like AST 212 U/L (8–40 U/L), ALT 65 U/L (7–3 U/L), LDH 622 U/L (100–230 U/L), and aldolase 21.8 U/L (<8 U/L). However, her CK and myoglobin levels were normal. Anti-nuclear antibody was positive, with a 1:320 titer and nuclear, speckled pattern. Electromyography (EMG) of the upper and lower extremities revealed active denervation of motor nerves, suggesting acute inflammatory myopathy with no evidence of polyneuropathy. A modified barium swallow test was performed, which revealed delayed oral transit with solids and moderate dysphagia. MRI of the thigh muscles revealed diffuse muscle edema and enhancement compatible with inflammatory myositis (Figure 1). The myositis panel was positive for SAE 1 and MDA 5 antibodies (Table 1). CT chest shows no lymphadenopathy or nodules, and no signs of interstitial pneumonitis. The patient underwent a muscle biopsy, which revealed severe inflammatory myopathy with perifascicular pathology (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

MRI femur.

Diffuse muscle edema as well as enhancement after contrast (right) compatible with myositis on T2-weighted sequences.

Table 1.

Extended myositis panel results.

| Extended myositis panel | Result |

|---|---|

| SAE1 (SUMO activating enzyme) Ab | Positive |

| MDA5 (melanoma differentiating protein) Ab | Positive |

| TIF-1 gamma Ab | Negative |

| NXP2 (nuclear matrix protein-2) Ab | Negative |

| Mi-2 (nuclear helicase protein) Ab | Negative |

| Jo-1 (histidyl-tRNA synthetase) Ab | Negative |

| SSA (anti-Sjӧgren’s syndrome-related antigen) Ab | Negative |

| SRP (signal recognition particle) Ab | Negative |

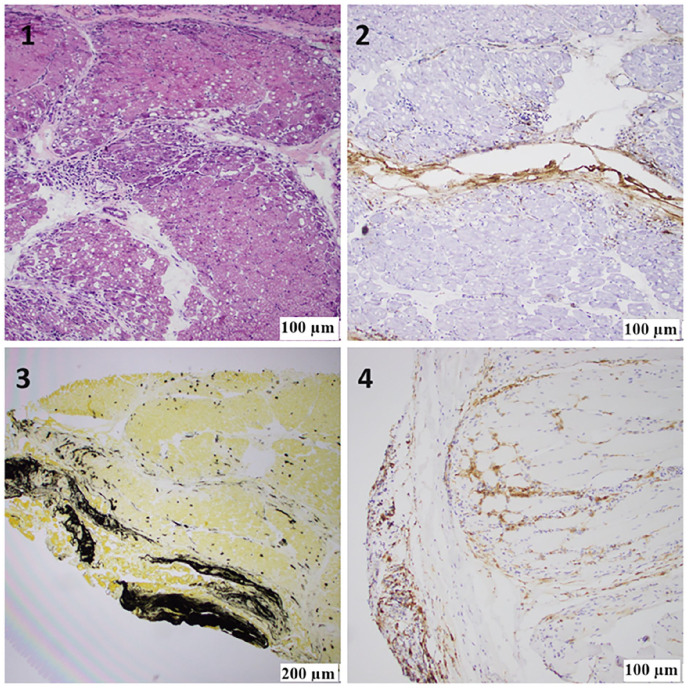

Figure 2.

(1) H&E staining of the frozen skeletal muscle block showing extensive areas of perifascicular atrophy, fiber damage, and perimysial mononuclear inflammation. (2) Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining of the frozen skeletal muscle block showing peripheral connective tissue reactivity adjacent to the areas of perifascicular abnormality and a significant increase in capillary uptake. (3) An anti-membrane attack complex c5b9 antibody frozen skeletal muscle block showing abnormal immunoreactivity of the perifascicular connective tissue adjacent to the areas of perifascicular abnormality and capillary uptake. (4) Anti-CD4 antibody, FFPE tissue block showing abundant T-helper lymphocytes in perifascicular areas of abnormality.

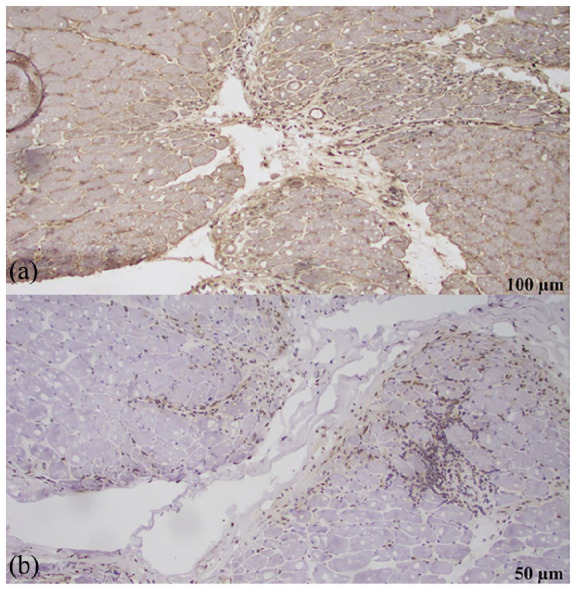

Figure 3.

(a) MHC-I block showing loss of microvasculature. (b) Myxovirus resistance A (MXA) frozen skeletal muscle block was negative for cytoplasmic staining in the areas of PF damage.

The patient was started on pulse–dose IV methylprednisolone and two doses of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIGs). The patient was then started on disease-modifying antirheumatic drug therapy with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), but due to worsening transaminitis, she was switched to azathioprine. The patient was evaluated and worked with speech-language pathology and physical therapy (PT) inpatient with continued slow, gradual improvement in her strength and dysphagia. The patient’s subsequent course was uneventful. Currently, she continues to follow rheumatology and is using azathioprine and receiving monthly IVIG. She is going to follow up with her primary care physician for malignancy screening.

Discussion

DM is an idiopathic immune-mediated myopathy characterized by proximal skeletal muscle weakness and skin manifestations. 7 In 1975, Bohan and Peter proposed the following criteria, with three out of four needed, for diagnosing DM: symmetrical weakness of proximal muscles, findings of myositis on muscle biopsy, elevated levels of serum muscle enzymes, abnormal EMG findings, and accompanying skin lesions. 8 In our case, the patient satisfied three criteria: rash, symmetrical weakness of the proximal muscles, and typical myositis findings on muscle biopsy. However, the utility of our case is to highlight the patient had positive MDA5 and anti-SAE 1 antibody and normal CK but severe myositis on muscle biopsy.

Elevated CK levels are seen in most cases of inflammatory myopathy. 9 Still, CK levels may be minimally elevated or even normal in IBM, 10 myositis associated with neoplasia, clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis (CADM), 11 and long-standing polymyositis and DM where significant muscle atrophy has developed.11,12 CK is known to be more specific for muscle damage than other labs, such as aldolase, which is expressed in other cases, such as liver disease as well. 13 There are also several imaging tests that can help diagnose inflammatory myositis, such as positron emission tomography, which shows uptake in the affected muscle and is more localized than MRI.14,15

In 2005, Sato et al. 16 identified the anti-MDA5 antibody, a DM-specific immune response targeting the MDA5 protein. 17 This antibody is present in a significant proportion (19%–35%) of individuals with DM. 18 Approximately 80% of MDA5-positive individuals present with a CADM phenotype in which skin manifestations such as Gottron’s papules, heliotrope rash, the shawl sign, the V sign, and arthritis are observed. 19 The presence of anti-MDA5 antibodies is linked to a greater likelihood of developing rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease (RP-ILD), a severe condition with a poor prognosis. 20 The mortality rate among individuals with MDA5-positive DM can reach 66%, with RP-ILD being the leading cause of death in almost 80% of these patients. 20

Similarly, anti-SAE1 antibodies have a low prevalence in DM and have been identified in approximately 1.5—8% of patients, with patient presentation with severe skin disease and mild muscle involvement. 21 Typical findings in anti-SAE1 positive patients are heliotrope rash and Gottron’s papules, but interestingly, the majority of these patients present with clinically amyopathic DM. 22 The disease has a tendency to progress to have severe systemic features of myositis, including severe dysphagia and ILD, in which cases biopsy shows perifascicular atrophy and scarce lymphocytic infiltrates. 23 However, the ILD associated with anti-SAE1 antibodies tends to be less severe. 24 Ge et al. 21 conducted a prospective cohort study that showed that anti-SAE1+ DM is also associated with dysphagia in 53% of patients and cancer in 23% of patients.

It is interesting to note that our patient presented with 4 months of progressive weakness with presentation of severe oropharyngeal involvement and muscle biopsy showing severe inflammatory myopathy and not substantial muscle atrophy; despite having positive anti-MD5 antibody, she did not have presentation of amyopathic DM. This underscores the importance of a comprehensive diagnostic approach, as the absence of an increased CK level can lead to DM being overlooked. Although there are other causes of normal CK levels, such as early disease, they do not seem to fit this case. This is due to the presentation of muscle weakness over the past 4 months, which has progressively worsened. In addition, advanced disease with muscle atrophy can have normal CK, which is ruled out, as no muscle atrophy is present in the biopsy. Rarely does myositis have muscular involvement beyond the limbs; the atypical presentation of dysphagia is thought to be due to inflammatory involvement of the pharyngeal skeletal muscles. 25 Although this patient was positive for anti-SAE1 and anti-MDA5 antibodies, it is essential to understand that only 50%–70% of patients with DM and CADM have myositis-specific antibodies, 26 and the rest are seronegative. This highlights the complexity of DM diagnosis and the need for a thorough understanding of its various presentations.

The treatment strategy for patients with DM involving anti-MDA5 and anti-SAE1 antibodies is similar to that used for patients with other DM subtypes. Initial therapy includes systemic glucocorticoids and a conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug. The use of MMF has become increasingly common, particularly for patients with DM who also have significant skin disease. A single-center cohort study demonstrated that MMF monotherapy was associated with increased odds of achieving clinical cutaneous disease remission (OR 6.00) compared to other therapies. 27 In severe disease, initial treatment with IVIG and intravenous methylprednisolone is given, as exemplified by our patient.28,29

Conclusion

DM is a multisystem disorder with a wide range of clinical manifestations. DM can present with significant muscle weakness and atrophy, accompanied by characteristic skin manifestations, despite normal levels of CK. DM-specific antibody screening, including SAE1 or anti-MDA5 antibodies, is often important because it may aid in the diagnosis of patients with normal CK levels. This case also highlights the importance of the history and physical examination in the face of contradictory laboratory results, as DM may not be included in differentials due to the absence of increased CK. Treatment consists of corticosteroids and immunosuppressive agents in combination with supportive therapy.

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

Author contributions: All authors contributed equally to the conception, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval: Our institution does not require ethical approval for reporting individual cases or case series.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for their anonymized information to be published in this article.

ORCID iDs: Srikar Sama  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1972-5787

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1972-5787

Nidaa Rasheed  https://orcid.org/0009-0006-1791-0504

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-1791-0504

References

- 1. Lundberg IE, Fujimoto M, Vencovsky J, et al. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Nat Rev Dis Primer 2021; 7(1): 1–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kronzer VL, Davis JM, Crowson CS, et al. Incidence, prevalence, and mortality of dermatomyositis: a population-based cohort study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2023; 75(2): 348–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Findlay AR, Goyal NA, Mozaffar T. An overview of polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Muscle Nerve 2015; 51(5): 638–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fudman EJ, Schnitzer TJ. Dermatomyositis without creatine kinase elevation. A poor prognostic sign. Am J Med 1986; 80(2): 329–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mathur T, Manadan AM, Thiagarajan S, et al. The utility of serum aldolase in normal creatine kinase dermatomyositis. J Clin Rheumatol 2014; 20(1): 47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sizemore TC. In the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, how significant is creatine kinase levels in diagnosis and prognosis? A case study and review of the literature. J Rheum Dis Treat 2015; 1: 025. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Iaccarino L, Ghirardello A, Bettio S, et al. The clinical features, diagnosis and classification of dermatomyositis. J Autoimmun 2014; 48–49: 122–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bohan A, Peter JB. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis (first of two parts). N Engl J Med 1975; 292: 344–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Malik A, Hayat G, Kalia JS, et al. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: clinical approach and management. Front Neurol 2016; 7: 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dalakas MC. Inflammatory muscle diseases. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1734–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sato S, Kuwana M. Clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2010; 22(6): 639–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dimachkie MM, Barohn RJ. Inclusion body myositis. Semin Neurol 2012; 32(3): 237–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nozaki K, Pestronk A. High aldolase with normal creatine kinase in serum predicts a myopathy with perimysial pathology. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2009; 80: 904–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tateyama M, Fujihara K, Misu T, et al. Clinical values of FDG PET in polymyositis and dermatomyositis syndromes: imaging of skeletal muscle inflammation. BMJ Open 2015; 5: e006763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cantwell C, Ryan M, O’Connell M, et al. A comparison of inflammatory myopathies at whole-body turbo STIR MRI. Clin Radiol 2005; 60: 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sato S, Hirakata M, Kuwana M, et al. Autoantibodies to a 140-kd polypeptide, CADM-140, in Japanese patients with clinically amyopathic dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum 2005; 52(5): 1571–1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fiorentino D, Chung L, Zwerner J, et al. The mucocutaneous and systemic phenotype of dermatomyositis patients with antibodies to MDA5 (CADM-140): a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011; 65(1): 25–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nakashima R, Imura Y, Kobayashi S, et al. The RIG-I-like receptor IFIH1/MDA5 is a dermatomyositis-specific autoantigen identified by the anti-CADM-140 antibody. Rheumatology 2010; 49(3): 433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gómez GN, Pérez N, Braillard Poccard A, et al. Myositis-specific antibodies and clinical characteristics in patients with autoimmune inflammatory myopathies: reported by the Argentine Registry of Inflammatory Myopathies of the Argentine Society of Rheumatology. Clin Rheumatol 2021; 40(11): 4473–4483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xie H, Zhang D, Wang Y, et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients with anti-MDA5 antibody-positive dermatomyositis: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2023; 62: 152231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ge Y, Lu X, Shu X, et al. Clinical characteristics of anti-SAE antibodies in Chinese patients with dermatomyositis in comparison with different patient cohorts. Sci Rep 2017; 7(1): 188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. de Vries M, Schreurs MWJ, Ahsmann EJM, et al. A case of anti-SAE1 dermatomyositis. Case Rep Immunol 2022; 2022: 9000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Allenbach Y, Benveniste O, Goebel HH, et al. Integrated classification of inflammatory myopathies. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2017; 43: 62–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gono T, Tanino Y, Nishikawa A, et al. Two cases with autoantibodies to small ubiquitin-like modifier activating enzyme: a potential unique subset of dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. Int J Rheum Dis 2019; 22(8): 1582–1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Labeit B, Pawlitzki M, Ruck T, et al. The impact of dysphagia in myositis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2020; 9(7): 2150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kwan C, Milosevic S, Benham H, Scott IA. A rare form of dermatomyositis associated with muscle weakness and normal creatine kinase level. BMJ Case Rep 2020; 13(2): e232260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wolstencroft PW, Chung L, Li S, et al. Factors associated with clinical remission of skin disease in dermatomyositis. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Jan 1;154(1):44-51. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3758. Erratum JAMA Dermatol 2018; 154(1): 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kamperman RG, van der Kooi AJ, de Visser M, et al. Pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment of dermatomyositis and immune mediated necrotizing myopathies: a focused review. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23(8): 4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nombel A, Fabien N, Coutant F, et al. Dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibodies: bioclinical features, pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Front Immunol 2021; 12: 773352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]