Abstract

Background:

Endoscopy is important for the diagnosis and treatment of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB), especially acute variceal bleeding (AVB), in liver cirrhosis. However, the optimal timing of endoscopy remains controversial, primarily because the currently available evidence is of poor quality, and the definition of early endoscopy is also very heterogeneous among studies. Herein, a multicenter randomized controlled trial (RCT) is performed to explore the impact of the timing of endoscopy on the outcomes of cirrhotic patients with AVB.

Methods:

A total of 368 cirrhotic patients presenting with AUGIB who are highly suspected to be from AVB will be enrolled. They will be stratified according to the severity of liver function and clinical presentation at admission and then randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio into early (within 12 h after admission) and delayed (within 12–24 h after admission) endoscopy groups within each stratum. The primary outcomes include the rates of 5-day failure to control bleeding after admission and 6-week rebleeding. The secondary outcomes include 6-week mortality and incidence of adverse events.

Conclusion:

Considering existing evidence originates from non-randomized studies, this RCT will provide high-quality evidence to uncover whether cirrhotic patients with AVB should undergo early endoscopy to control bleeding and improve survival.

Trial registration:

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT06031402.

Keywords: endoscopy, gastrointestinal bleeding, liver cirrhosis, randomized controlled trial, survival, variceal bleeding

Introduction

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding (AUGIB), one of the most common emergency and critical conditions in our everyday clinical practice, can cause poor outcomes. 1 Among the patients with liver cirrhosis, the most common source of AUGIB is gastroesophageal varices secondary to portal hypertension, 2 which is mainly caused by increased portal blood flow resistance due to a change in the intrinsic structure of the cirrhotic liver. When the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), an indicator for the evaluation of portal pressure, 3 is >10 mmHg, varices will occur; and when the HVPG is >12 mmHg, the risk of variceal bleeding will be increased. The incidence of acute variceal bleeding (AVB) in cirrhotic patients is 25%–40%, with a 6-week mortality of 10%–20%.2,4

Endoscopy is an important approach for the diagnosis and treatment of AUGIB in cirrhotic patients.1,5 However, it is an invasive procedure and requires technical expertise. Accessibility of emergency endoscopy is often low at hospitals or remote areas that lack 24-h endoscopic service. Thus, most severely ill patients with AUGIB, especially those who fail conventional drug therapy, need to be immediately transferred to a higher-level medical center.

Until now, the optimal timing of initiating endoscopy for the management of cirrhotic patients with AUGIB is inconsistent among various practice guidelines or consensuses. The Baveno consensus, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases practice guideline, the Belgian practice guideline, and the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy practice guideline recommend that endoscopy should be performed within 12 h since the onset of AVB.4,6–8 The UK practice guideline recommends that patients with severe and hemodynamically unstable AVB should undergo endoscopy as soon as possible after basic resuscitation, while other patients should undergo endoscopy within 24 h of admission. 9 The Chinese practice guideline recommends that endoscopic examination should be preferably performed within 12–24 h after the onset of AVB. 10

On the other hand, the current evidence regarding the impact of early endoscopy on the outcomes of cirrhotic patients with AVB is also controversial among studies. Yoo et al. 11 found no significant difference in 6-week rebleeding rate or mortality between early (<12 h) and delayed (>12 h) endoscopy groups. By contrast, Hsu et al. 12 demonstrated that delayed endoscopy performed beyond 15 h after admission was an independent risk factor for in-hospital mortality. In another retrospective study, where early endoscopy was defined as endoscopy performed within 6 h after admission, the patient’s outcomes were superior in the early endoscopy group (<6 h) than the delayed endoscopy group (6–24 h). 13 Furthermore, our meta-analysis, including 9 studies with 2824 patients, systematically explored the impact of timing of endoscopy on the outcomes of cirrhotic patients with AVB. The early endoscopy group had significantly lower overall mortality than the delayed endoscopy group (odds ratio (OR) = 0.56, p = 0.03), but there was no significant difference in overall rebleeding rate between the two groups (OR = 0.88, p = 0.63). 14 However, we have to acknowledge some limitations in these studies. First, all previously published studies are retrospective, which cannot ensure the comparability of patients’ baseline characteristics between the two groups. Second, the definitions of early endoscopy and outcomes are different among them.

Recently, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) has shown no significant difference in terms of 30-day mortality between AUGIB patients who underwent emergency (<6 h) and early (6–24 h) endoscopy. However, in a majority of included patients, liver cirrhosis was not diagnosed (91.8%), and AUGIB was unrelated to variceal rupture (82.9%). 15 Thus, its findings may not be appropriate for cirrhotic patients with AUGIB, especially those with AVB, who may have a higher risk of rebleeding and mortality and requirement of endoscopic treatment.

To date, there has been no RCT exploring the impact of the timing of endoscopy on the outcomes of cirrhotic patients with AVB. Therefore, we will conduct this RCT to minimize the bias caused by various confounding factors and further clarify this issue.

Methods

Study design

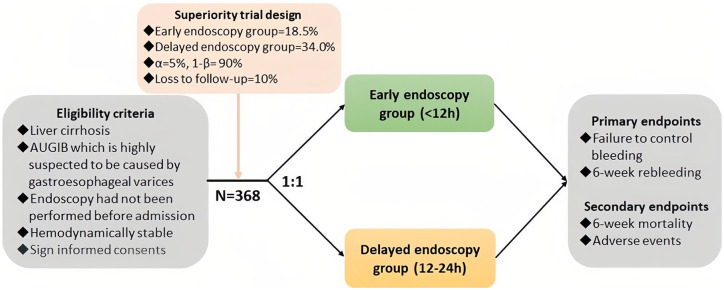

In this multicenter RCT, all cirrhotic patients with a suspected diagnosis of AVB who are consecutively admitted will be screened. All centers are experienced in treating cirrhotic patients with AUGIB. All principal investigators at each site are skilled in the endoscopic treatment of variceal bleeding. Before enrollment, all patients and/or their relatives will be informed about the study protocol and sign the written informed consent forms. Eligible patients are randomly assigned at a ratio of 1:1 to the early endoscopy group (within 12 h after admission) and delayed endoscopy group (within 12–24 h after admission) (Figure 1). Patients’ characteristics at admission, treatment options during hospitalization, and outcomes during follow-up are collected. The impact of early and delayed endoscopy on the prognosis of cirrhotic patients with AVB will be evaluated. The reporting of this study conforms to the SPIRIT statement. 16

Figure 1.

Flowchart of this trial.

Eligibility criteria

Participants should meet the following criteria: (1) patients with AUGIB which is highly suspected to be caused by gastroesophageal variceal rupture; (2) patients with a diagnosis of liver cirrhosis based on imaging and pathology; (3) patients and/or their relatives who sign informed consents; and (4) patients’ age ⩾18 years.

The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) patients who have undergone endoscopy at other hospitals before admissions; (2) patients’ hemodynamics are unstable after resuscitation; (3) patients with severe cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases or renal injury; (4) patients who have taken anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs within 2 weeks before admissions or are diagnosed with severe hematological diseases; (5) patients with human immunodeficiency virus or other acquired or congenital immune deficiency diseases; (6) patients with mental illness; and (7) pregnancy.

Randomization and blinding

Participants will be stratified according to the severity of liver dysfunction (i.e., Child-Pugh class A, B, and C) and clinical presentation (i.e., presence and absence of hematemesis) at their admissions, and randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio to early endoscopy and delayed endoscopy groups within each stratum. To ensure consistency in the number of participants assigned to the two groups in each stratum, blocked randomization will be employed with a block size of six patients. Random numbers and their corresponding groups are generated by an online central randomization system, to which all principal investigators in each site have access. Neither participants nor clinicians can be blinded because the participants’ grouping is performed in accordance with the timing of endoscopy and the interval from admission to endoscopy is different between the two groups. However, endoscopists who are responsible for performing endoscopic procedures and investigators who are responsible for follow-up are blinded to the patient’s grouping throughout the study.

General treatment

After admission, the patient’s respiratory, circulatory, and mental status will be promptly evaluated. The patient’s vital signs and laboratory indicators will be continuously and dynamically monitored. A urethra catheter will be inserted and kept in patients with consciousness disorders and/or shock. At least two peripheral venous routes will be opened in patients with massive bleeding, and a central venous catheter will be placed if necessary. If patients present with syncope, persistent hematemesis or blood in the stool, cold limbs, heart rate >100 beats/min, systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, and hemoglobin concentration <70 g/L, resuscitation will be started immediately, including restrictive volume resuscitation, blood transfusion, and vasoactive drugs.

All patients will receive intravenous administration of terlipressin, somatostatin, or somatostatin analogs in combination with high-dose proton pump inhibitors and prophylactic antibiotics for a duration of up to 7 days.10,17,18 In the absence of contraindications for anesthesia, endoscopy is preferred under general anesthesia. The selection of endotracheal intubation and anesthetic drugs during endoscopy will be determined by anesthesiologists, rather than endoscopists. Experienced endoscopists will select endoscopic treatment according to the type of bleeding, including endoscopic band ligation, sclerotherapy, and/or glue injection. Endoscopy will be repeated 4–6 weeks after the first endoscopic variceal therapy, and additional endoscopic variceal therapy will be performed if necessary.10,18

If patients assigned to the delayed endoscopy group present with persistent or massive bleeding, emergency endoscopy will be performed after evaluation by endoscopists. If bleeding cannot be controlled by the first endoscopy, repeat endoscopic treatment, radiological intervention, and/or surgery will be performed according to the patient’s specific conditions or preferences.

Potential risks

Potential risks related to the study are mainly adverse events caused by endoscopic procedures (Supplemental Table 1). They will be recorded in all enrolled participants and followed until it has been appropriately addressed and is deemed “stable” by the investigators.

Study endpoints

The primary study endpoints include failure to control bleeding after admissions and 6-week rebleeding. The secondary study endpoints include 6-week all-cause mortality and adverse events.

Sample size calculation

The sample size is calculated by testing for significant differences in the proportion between the two groups. Based on the results of a retrospective study by Chen et al., 19 the rate of 6-week rebleeding is estimated as 18.5% and 34.0% in early and delayed endoscopy groups, respectively. Under a two-sided 0.05 alpha value (type I error 5%), 90% power (type II error 10%), a ratio of 1:1 for experimental and control groups, and a drop-out rate of 10%, Pearson Chi-square test is performed using PASS software (version 15.0.5 NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA), resulting in a required sample size of 184 patients per group. Patient recruitment will be completed within 3 years.

Diagnosis and definitions

AUGIB is defined as hematemesis and/or melena occurring within 5 days prior to the admission. 4 Hematemesis is characterized as patients vomiting fresh red blood or coffee-ground-like contents. Melena is characterized as patients having black tarry stools or brown feces. Sometimes, patients with AUGIB also present with hematochezia.

The highly suspected diagnosis of variceal bleeding would be primarily dependent on the history of liver cirrhosis and clinical and imaging characteristics of portal hypertension.

Variceal bleeding would be diagnosed, if any one of the following conditions was met: (1) active bleeding from esophageal or gastric varices under endoscopy, (2) white thrombus on the surface of varices, suggesting recent variceal bleeding; or (3) only varices in the esophagus or stomach without any other sources of bleeding. 6

Non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding is characterized as gastrointestinal bleeding located above the Treitz ligament is caused by non-variceal sources, primarily including peptic ulcer, upper gastrointestinal tumors, stress ulcer, acute gastrointestinal mucosal damage, Mallory–Weiss syndrome, upper gastrointestinal vascular malformations, Dieulafoy’s lesions, periampullary tumors, pancreatic tumors, and bile duct tumors. 20

Failure to control bleeding is defined as any one of the four following conditions within 5 days of admission: (1) vomiting of fresh blood; (2) suction of more than 100 ml of fresh blood from the nasogastric tube; (3) a decrease in hemoglobin concentration of 30 g/L in the absence of blood transfusion; or (4) death. 4

Rebleeding is defined as a new onset of hematemesis or melena after successful treatment, and/or a decrease in hemoglobin concentration of 30 g/L in the absence of blood transfusion, and/or development of hypovolemic shock.

Data collection

The following data will be collected: (1) demographic data, including gender and age; (2) history of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, alcoholic liver disease, autoimmune liver disease, and other diseases that may lead to cirrhosis; (3) vital signs, including heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate; (4) clinical symptoms related to AUGIB, primarily including hematemesis and melena; (5) the time interval between the last occurrence of gastrointestinal bleeding related symptoms and admission; (6) laboratory data at admissions and during follow-up periods, including hemoglobin concentration, liver function, renal function, electrolytes, and coagulation function; (7) Child-Pugh and model for end-stage of liver disease (MELD) scores; (8) treatment, including basic resuscitation, blood transfusion, antibiotics, vasoactive agents, and other hemostatic medications; (9) time interval between admission and endoscopy; (10) location (upper, middle, and lower esophagus, gastric fundus and body, and duodenum), diameter, and risk factors (red color sign and white nipple) of gastroesophageal varices on endoscopy, which are consistent with Linghu’s classification and the recommendation of Chinese guidelines for the management of esophagogastric variceal bleeding 21 ; (11) type of endoscopic treatment; (12) interventional or surgical treatment; (13) failure to control bleeding; (14) rebleeding during hospitalizations and follow-up period; (15) adverse events during hospitalizations and follow-up period; and (16) death during hospitalizations and follow-up periods. All data collection will be completed through an online central system.

Follow-up

We will communicate with patients and their family members via WeChat and/or telephone, to remind them to undergo follow-up examinations on time, address their health issues, provide targeted health education, maintain a good doctor–patient relationship, and enhance patients’ adherence. During follow-up periods, clinical symptoms, physical examinations, rebleeding, survival status, and adverse events will be recorded every week. Routine blood and stool tests, liver and renal function, and coagulation tests will be performed every 2 weeks. Repeat endoscopy will be regularly conducted within 4–6 weeks after the first endoscopy. Patients will be followed until 6 weeks after endoscopy.

Treatment termination

Treatment termination refers to the situation where a participant stops receiving his/her assigned treatment, but does not withdraw from the trial and is still followed according to the protocol. Reasons for treatment termination may include, but are not limited to:

(1) Participants’ conditions worsen before endoscopy, such as loss of consciousness or coma related to hepatic encephalopathy, but does not include death.

(2) Participants have difficulty complying with the treatment regimen, have no confidence in the doctor or hospital, or negative attitude toward treatment.

(3) Participants request to terminate treatment but agree to continue follow-up.

(4) Participants withdraw their willingness to participate in the trial.

Major reason(s) for treatment termination should be recorded on the case report form. Regardless, we will try our best to obtain the follow-up information from the participants who withdraw from the trial.

Withdrawal

Participants can withdraw from the trial at any time. Reasons for withdrawal may include, but are not limited to (1) withdrawal of informed consents; (2) study termination or center closure; and (3) lost follow-up. Major reason(s) for withdrawal from the trial should be recorded on the case report form. Regardless, we will try our best to obtain the follow-up information from participants who withdraw from the trial.

Study schedule

During the study period, patients’ assessment and treatment plans are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study schedule.

| Procedure | Screening | Enrollment (baseline) | Follow-up | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 d | 1 w | 2 w | 3 w | 4 w | 5 w | 6 w | |||

| Informed consent | X | ||||||||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | X | ||||||||

| Demographic data | X | ||||||||

| Medical history | X | ||||||||

| Clinical symptoms | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Physical examination | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Laboratory test | |||||||||

| Routine blood test | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Routine stool test a | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Liver function | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Renal function | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Coagulation test | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Endoscopy | X | X b | |||||||

| Control of bleeding | X | ||||||||

| Rebleeding | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Survival | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Adverse events | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

Routine stool test is optional.

Repeat endoscopy should be performed 2–4 weeks after the first endoscopy.

d, days; w, weeks.

(1) According to the inclusion/exclusion criteria, eligible participants will be enrolled after signing informed consent forms and then randomized.

(2) Demographic information, medical history, clinical symptoms, physical examination, routine blood and stool tests, liver function, renal function, and coagulation tests will be completed before endoscopy.

(3) Endoscopy will be carried out in a timely manner depending on the severity of the patient’s conditions.

(4) Control of bleeding within 5 days after endoscopy will be observed.

(5) Clinical symptoms, physical examination, rebleeding, survival, and adverse events will be monitored every week after endoscopy.

(6) Routine blood and stool tests, liver function, renal function, and coagulation tests will be conducted every 2 weeks.

(7) Repeat endoscopy will be performed 4–6 weeks after the first endoscopy.

Data analysis

The intention-to-treat (ITT) set comprises all participants randomized. The per-protocol (PP) set is a subset of the ITT set, consisting of participants who complete their assigned treatments and follow up according to the study protocol without significant protocol violations. In the case where the results of the ITT set are different from those of the PP set, the ITT results will be preferred. If participants did not have a definite diagnosis of varices under endoscopy, or participants assigned to the delayed endoscopy group developed massive bleeding before endoscopy, they would be included in the ITT set, rather than the PP set. According to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement, 22 we will specify the number of participants screened, randomized, and lost to follow-up.

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation and median (range) and categorical variables as frequencies (percentages). Non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test is employed for a comparison of continuous variables between early and delayed endoscopy groups, while the Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test are employed for categorical variables. Considering the effect of the participating center on the outcomes, they will be adjusted by the center where participants were enrolled in multivariate regression analyses, and the interaction between participating centers and outcomes will also be evaluated. Specifically, failure to control bleeding and adverse events will be evaluated in multivariate logistic regression analyses, and 6-week rebleeding and 6-week all-cause mortality in multivariate Cox regression analyses. In addition, the cumulative risk of 6-week rebleeding and 6-week all-cause mortality between the two groups will be visualized by Kaplan–Meier curves, and then compared by log-rank tests. Subgroup analyses will be conducted according to the clinical manifestations of AVB (with or without hematemesis) and severity of liver disease (Child-Pugh class A/B/C). Multiple imputation will be performed to address missing data, if necessary. A two-sided p-value <0.05 is considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses are performed using IBM SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

Discussion

There is a controversy about the timing of endoscopy in cirrhotic patients with AVB, probably due to the heterogeneity in patients’ hemodynamic status and disease severity, decision to early endoscopy, and definition of early endoscopy among previous studies. More importantly, the existing evidence is from non-randomized studies. In this setting, an RCT will be required to guide clinical decisions.

At the stage of randomization, all eligible patients will be stratified according to the severity of liver dysfunction and clinical presentations. This is primarily because higher Child-Pugh and MELD scores23,24 as well as hematemesis25,26 are significantly associated with a higher mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis and AVB. In addition, patients who are still hemodynamically unstable after initial resuscitation will be excluded because they are often at a higher risk of developing complications secondary to endoscopy, of which some are accidentally fatal.27–30

As known, endoscopy is indispensable for identifying the source of AUGIB.1,5 However, it should be noted that our participants will be assigned into early and delayed endoscopy groups according to the timing of endoscopy, suggesting that randomization has to be completed before the implementation of endoscopy. Thus, it is inevitable that a proportion of participants included will not be diagnosed with AVB after randomization.

Theoretically, it should be more reasonable that the timing of endoscopy refers to the interval from the last episode of gastrointestinal bleeding to endoscopy. However, not all participants and their relatives can accurately remember the time when the last episode of gastrointestinal bleeding developed. In addition, some participants are transferred to our participating centers beyond 12 h after their last episode of gastrointestinal bleeding, which will fail their inclusion and further greatly decrease the number of participants randomized. By comparison, it should be more practical to define the timing of endoscopy as the time interval from admission to endoscopy.

The threshold for differentiating between early and delayed endoscopy is different among practice guidelines. A threshold of <12 h as early endoscopy is recommended according to the Baveno consensus 18 and American, 6 Belgian, 7 and European 8 practice guidelines, <24 h according to the UK practice guideline, 9 and <12–24 h according to the Chinese practice guideline. 10 On the other hand, the latest time when a delayed endoscopy should be performed is unclear. 12 In our trial, early and delayed endoscopy is defined as the implementation of endoscopy within 12 h and 12–24 h, respectively.

We should acknowledge some factors affecting the selection of early endoscopy in clinical practice. In resource-limited regions, endoscopy cannot be promptly performed, endoscopists are not at a 24-h call service status, and/or experienced endoscopists who can undergo endoscopic variceal treatment are not available. Our study can provide high-quality evidence about whether early endoscopy is beneficial and necessary, especially in the setting of primary care. In addition, in real-world studies, a proportion of patients with AUGIB did not undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy to identify the sources of bleeding due to various reasons.26,31 Thus, it should be unnecessary to explore the timing of endoscopy in such patients, and also unrealistic to extrapolate our findings in all cirrhotic patients with a suspected diagnosis of AVB.

In conclusion, the findings of this RCT will provide high-quality evidence for further clarifying when endoscopy should be performed in patients with liver cirrhosis with AVB.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tag-10.1177_17562848241295452 for Timing of endoscopy in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding: protocol of a multicenter randomized controlled trial by Xingshun Qi, Yiling Li, Bimin Li, Xuefeng Luo, Xiaofeng Liu, Chunqing Zhang, Mingkai Chen, Derun Kong, Yunhai Wu, Fernando Gomes Romeiro, Metin Basaranoglu, Jianzhong Zhang, Qianqian Li, Ran Wang, Xiaodong Shao, Lin Guan, Ningning Wang, Yu You, Mingyan He, Xiaoze Wang, Ju Huang, Wenming Wu, Qun Li, Mingyan Zhang, Guangchuan Wang, Chi Zhang, Du Cheng, Qianqian Zhang, Xuechan Mei, Na Sun, Yuan Ban, Mariana Barros Marcondes, Fabio da Silva Yamashiro, Emine Mutlu, Zheng Zheng, Mengyuan Peng, Wentao Xu, Zhe Li, Lu Chai and Enqiang Linghu in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology

Acknowledgments

None.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Xingshun Qi  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9448-6739

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9448-6739

Yiling Li  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3209-8105

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3209-8105

Derun Kong  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7878-8553

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7878-8553

Wentao Xu  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0156-791X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0156-791X

Enqiang Linghu  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4506-7877

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4506-7877

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Xingshun Qi, Liver Cirrhosis Study Group, Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, No. 83 Wenhua Road, Shenyang, Liaoning Province 110840, China.

Yiling Li, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China.

Bimin Li, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China.

Xuefeng Luo, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China.

Xiaofeng Liu, Department of Gastroenterology, The 960th Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, Jinan, Shandong, China.

Chunqing Zhang, Department of Gastroenterology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, China.

Mingkai Chen, Department of Gastroenterology, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China.

Derun Kong, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Yunhai Wu, Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Sixth People’s Hospital of Shenyang, Shenyang, China.

Fernando Gomes Romeiro, Internal Medicine Department, Botucatu Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil.

Metin Basaranoglu, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Bezmialem Vakif University, Istanbul, Turkey.

Jianzhong Zhang, Division of Medical Research, Unimed Scientific Inc., Wuxi, China.

Qianqian Li, Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, China.

Ran Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, China.

Xiaodong Shao, Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, China.

Lin Guan, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China.

Ningning Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University, Shenyang, China.

Yu You, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China.

Mingyan He, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University, Nanchang, China.

Xiaoze Wang, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China.

Ju Huang, Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China.

Wenming Wu, Department of Gastroenterology, The 960th Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, Jinan, Shandong, China.

Qun Li, Department of Gastroenterology, The 960th Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army, Jinan, Shandong, China.

Mingyan Zhang, Department of Gastroenterology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, China.

Guangchuan Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, Jinan, China.

Chi Zhang, Department of Gastroenterology, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China.

Du Cheng, Department of Gastroenterology, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, Wuhan, China.

Qianqian Zhang, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Xuechan Mei, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, Hefei, China.

Na Sun, Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Sixth People’s Hospital of Shenyang, Shenyang, China.

Yuan Ban, Department of Critical Care Medicine, The Sixth People’s Hospital of Shenyang, Shenyang, China.

Mariana Barros Marcondes, Internal Medicine Department, Botucatu Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil.

Fabio da Silva Yamashiro, Internal Medicine Department, Botucatu Medical School, São Paulo, Brazil.

Emine Mutlu, Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Bezmialem Vakif University, Istanbul, Turkey.

Zheng Zheng, Division of Medical Research, Unimed Scientific Inc., Wuxi, China.

Mengyuan Peng, Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, China.

Wentao Xu, Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, China.

Zhe Li, Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, China.

Lu Chai, Department of Gastroenterology, General Hospital of Northern Theater Command, Shenyang, China.

Enqiang Linghu, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Medical Center of Chinese PLA General Hospital, No. 28 Fuxing Road, Beijing 100853, China.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The study protocol has been approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command (ethical approval number Y2023-104) on June 24, 2023, as well as the ethical board of other participating centers including The First Affiliated Hospital of China Medical University (ethical approval number 2024-548), The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (ethical approval number IIT-2024-406), West China Hospital (ethical approval number 2023-2027), The 960th Hospital of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (ethical approval number 2023-030), Affiliated Provincial Hospital of Shandong First Medical University (ethical approval number SWYX: No. 2024-133), People’s Hospital of Wuhan University (ethical approval number WDRY 2024-K144), The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University (ethical approval number PJ-2023-12-19), The Sixth People’s Hospital of Shenyang (ethical approval number 2023-12-004-01), Botucatu Medical School (ethical approval number 6.430.285), and Bezmialem Vakif University (ethical approval number 2024/24). Consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Xingshun Qi: Conceptualization; Investigation; Supervision; Writing – original draft.

Yiling Li: Investigation.

Bimin Li: Investigation.

Xuefeng Luo: Investigation.

Xiaofeng Liu: Investigation.

Chunqing Zhang: Investigation.

Mingkai Chen: Investigation.

Derun Kong: Investigation.

Yunhai Wu: Investigation.

Fernando Gomes Romeiro: Investigation.

Metin Basaranoglu: Investigation.

Jianzhong Zhang: Software.

Qianqian Li: Project administration.

Ran Wang: Investigation.

Xiaodong Shao: Investigation.

Lin Guan: Investigation.

Ningning Wang: Investigation.

Yu You: Investigation.

Mingyan He: Investigation.

Xiaoze Wang: Investigation.

Ju Huang: Investigation.

Wenming Wu: Investigation.

Qun Li: Investigation.

Mingyan Zhang: Investigation.

Guangchuan Wang: Investigation.

Chi Zhang: Investigation.

Du Cheng: Investigation.

Qianqian Zhang: Investigation.

Xuechan Mei: Investigation.

Na Sun: Investigation.

Yuan Ban: Investigation.

Mariana Barros Marcondes: Investigation.

Fabio da Silva Yamashiro: Investigation.

Emine Mutlu: Investigation.

Zheng Zheng: Formal analysis.

Mengyuan Peng: Writing – original draft.

Wentao Xu: Writing – original draft.

Zhe Li: Writing – original draft.

Lu Chai: Project administration.

Enqiang Linghu: Investigation; Supervision.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Fees for establishing both patient randomization and assignment system and data-entry system for this RCT were afforded by the Outstanding Youth Foundation of Liaoning Province (2022-YQ-07). Fees for article publication were afforded by the Science and Technology plan Project of Liaoning province (2002JH2/101500032). This research is alsoi receiving the funding from the National Key R&D of China (2023YFC2507500).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials: The data and material are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

- 1. Stanley AJ, Laine L. Management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 2019; 364: l536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362(9): 823–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Veldhuijzen van Zanten D, Buganza E, Abraldes JG. The role of hepatic venous pressure gradient in the management of cirrhosis. Clin Liver Dis 2021; 25(2): 327–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. de Franchis R. Expanding consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno VI Consensus Workshop: stratifying risk and individualizing care for portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2015; 63(3): 743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Orpen-Palmer J, Stanley AJ. Update on the management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. BMJ Med 2022; 1(1): e000202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, et al. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology 2017; 65(1): 310–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Colle I, Wilmer A, Le Moine O, et al. Upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding management: Belgian guidelines for adults and children. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2011; 74(1): 45–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Karstensen JG, Ebigbo A, Bhat P, et al. Endoscopic treatment of variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Cascade Guideline. Endosc Int Open 2020; 8(7): E990–E997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tripathi D, Stanley AJ, Hayes PC, et al. U.K. guidelines on the management of variceal haemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. Gut 2015; 64(11): 1680–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chinese Society of Hepatology; Chinese Society of Gastroenterology; and Chinese Society of Digestive Endoscopology of Chinese Medical Association. [Guidelines on the management of esophagogastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic portal hypertension]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi 2022; 30(10): 1029–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yoo JJ, Chang Y, Cho EJ, et al. Timing of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy does not influence short-term outcomes in patients with acute variceal bleeding. World J Gastroenterol 2018; 24(44): 5025–5033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hsu YC, Chung CS, Tseng CH, et al. Delayed endoscopy as a risk factor for in-hospital mortality in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 24(7): 1294–1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Badave RR, Tantry V, Gopal S, et al. Very early (<6 h) endoscopic therapy affects the outcome in acute variceal bleeding: a retrospective study from Tertiary Care Hospital in South India. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2017; 7: S65. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bai Z, Wang R, Cheng G, et al. Outcomes of early versus delayed endoscopy in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 33(Suppl. 1): e868–e876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lau JYW, Yu Y, Tang RSY, et al. Timing of endoscopy for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(14): 1299–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158(3): 200–207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Qi X, Bai Z, Zhu Q, et al. Practice guidance for the use of terlipressin for liver cirrhosis-related complications. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 2022; 15: 17562848221098253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. de Franchis R, Bosch J, Garcia-Tsao G, et al. Baveno VII—renewing consensus in portal hypertension. J Hepatol 2022; 76(4): 959–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chen PH, Chen WC, Hou MC, et al. Delayed endoscopy increases re-bleeding and mortality in patients with hematemesis and active esophageal variceal bleeding: a cohort study. J Hepatol 2012; 57(6): 1207–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kim JJ, Sheibani S, Park S, et al. Causes of bleeding and outcomes in patients hospitalized with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014; 48(2): 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu X, Tang C, Linghu E, et al. Guidelines for the management of esophagogastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic portal hypertension. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2023; 11(7): 1565–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Int J Surg 2012; 10(1): 28–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peng Y, Qi X, Dai J, et al. Child-Pugh versus MELD score for predicting the in-hospital mortality of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in liver cirrhosis. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015; 8(1): 751–757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peng Y, Qi X, Guo X. Child-Pugh versus MELD score for the assessment of prognosis in liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine 2016; 95(8): e2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Li Y, Li H, Zhu Q, et al. Effect of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding manifestations at admission on the in-hospital outcomes of liver cirrhosis: hematemesis versus melena without hematemesis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019; 31(11): 1334–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Laine L, Laursen SB, Zakko L, et al. Severity and outcomes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding with bloody vs. coffee-grounds hematemesis. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113(3): 358–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. ter Laan M, Totte E, van Hulst RA, et al. Cerebral gas embolism due to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 21(7): 833–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ha JF, Allanson E, Chandraratna H. Air embolism in gastroscopy. Int J Surg (London, England) 2009; 7(5): 428–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fang Y, Wu J, Wang F, et al. Air embolism during upper endoscopy: a case report. Clin Endosc 2019; 52(4): 365–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Emir T, Denijal T. Systemic air embolism as a complication of gastroscopy. Oxf Med Case Rep 2019; 2019(7): omz057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cazacu SM, Alexandru DO, Statie RC, et al. The accuracy of pre-endoscopic scores for mortality prediction in patients with upper GI bleeding and no endoscopy performed. Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) 2023; 13(6): 1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tag-10.1177_17562848241295452 for Timing of endoscopy in cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding: protocol of a multicenter randomized controlled trial by Xingshun Qi, Yiling Li, Bimin Li, Xuefeng Luo, Xiaofeng Liu, Chunqing Zhang, Mingkai Chen, Derun Kong, Yunhai Wu, Fernando Gomes Romeiro, Metin Basaranoglu, Jianzhong Zhang, Qianqian Li, Ran Wang, Xiaodong Shao, Lin Guan, Ningning Wang, Yu You, Mingyan He, Xiaoze Wang, Ju Huang, Wenming Wu, Qun Li, Mingyan Zhang, Guangchuan Wang, Chi Zhang, Du Cheng, Qianqian Zhang, Xuechan Mei, Na Sun, Yuan Ban, Mariana Barros Marcondes, Fabio da Silva Yamashiro, Emine Mutlu, Zheng Zheng, Mengyuan Peng, Wentao Xu, Zhe Li, Lu Chai and Enqiang Linghu in Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology