ABSTRACT

Background: Emergency service personnel perform roles associated with high levels of trauma exposure and stress, and not surprisingly experience greater risk for poor mental health including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and substance use relative to the general population. Although programs exist to minimise the risk of developing mental health problems, their efficacy to date has been limited or untested. We will test the efficacy of the three programs which form PEREI: Protecting Emergency Responders with Evidence-Based Interventions. PEREI consists of modified versions of internet-delivered cognitive training in resilience (iCT-R) for early career first responders, PEREI-S for supervisors, and Be Well for Significant Others (BW-SO).

Method: Up to 450 members in their first 5 years of service across multiple agencies will be recruited, with their adult supports (significant others, friends) invited to participate. Up to 180 supervisors in the agencies will be recruited. Participants will be randomized to their respective program or to receive the standard practice for mental health offered by the service (or usual mental health support for significant others). Assessments will be conducted pre- and post-program, and at 6- and 12-month follow-up. Primary outcome is PTSD and depression severity and probable-diagnosis. Secondary measures will index hypothesized mediators and moderators of outcome and determine whether the programs are cost-effective.

Conclusions: The results will provide evidence as to efficacious methods for reducing risk of mental health problems in high-risk occupations, a better understanding of how such interventions may work, and whether they are good value for money.

Trial registration: www.anzctr.org.au (ACTRN12622001267741)

KEYWORDS: First responder, prevention, resilience, wellbeing, training, posttraumatic stress, depression

HIGHLIGHTS

Reducing the risk of mental health problems in first responders is critical given the frequent exposure to trauma as well as the occupational and organisational stress inherent in the role.

This study will test a program for early career first responders aimed at maintaining resilience and preventing mental health problems, such as posttraumatic stress disorder and depression.

The study is unique in examining the effectiveness of programs for three relevant groups: early career first responders, significant others, and supervisors within the emergency services.

Abstract

Antecedentes: El personal de los servicios de emergencia realiza funciones asociadas con altos niveles de exposición a traumas y estrés y, como no es de extrañar, experimenta un mayor riesgo de sufrir problemas de salud mental, tales como trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT), depresión, ansiedad y uso de sustancias, en comparación con la población general. Aunque existen programas diseñados para minimizar el riesgo de desarrollar problemas de salud mental, su eficacia hasta la fecha ha sido limitada o no probada. Evaluaremos la eficacia de tres programas que forman PEREI (por sus siglas en ingles): Protegiendo a los Respondedores de Emergencias con Intervenciones Basadas en Evidencia. PEREI consiste en versiones modificadas de un entrenamiento cognitivo en resiliencia entregado por internet (iCT-R) para primeros respondedores en las primeras etapas de su carrera, PEREI-S para supervisores, y Be Well para personas significativas (BW-SO).

Método: Se reclutarán hasta 450 miembros en sus primeros 5 años de servicio en múltiples agencias, junto con sus apoyos adultos (parejas significativas, amigos) invitados a participar. Se reclutarán hasta 180 supervisores en las agencias. Los participantes serán asignados aleatoriamente a sus respectivos programas o a recibir la práctica estándar de apoyo para la salud mental ofrecida por el servicio (o el apoyo habitual para las personas significativas). Las evaluaciones se realizarán antes y después del programa, así como a los 6 y 12 meses de seguimiento. El resultado principal es la gravedad y el diagnóstico probable de TEPT y depresión. Las medidas secundarias evaluarán mediadores y moderadores hipotéticos del resultado y determinarán si los programas son rentables.

Conclusiones: Los resultados proporcionarán evidencia sobre métodos eficaces para reducir el riesgo de problemas de salud mental en ocupaciones de alto riesgo, una mejor comprensión de cómo funcionan estas intervenciones y si son rentables.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Primer respondedor, prevención, resiliencia, bienestar, entrenamiento, estrés postraumático, depresión

1. Introduction

Emergency service personnel (also referred to as first responders, public safety officers, or emergency responders) are at significant risk for psychological distress including suicidal thoughts, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety, with rates of PTSD and psychological distress twice that seen in the general population (Beyond Blue, 2018; Wild et al., 2016). The mental health and wellbeing of family members and close social networks can similarly be impacted. This can be via vicarious traumatization, concern about the safety and emotional wellbeing of the significant other, or due to the operational impacts of the role on family life (Garmezy, 2020; Karaffa et al., 2015).

Despite the known impacts and the growing number of programs aimed at preventing mental health issues, evidence suggests that many of the programs fail to address modifiable risk factors that increase vulnerability to mental health problems among emergency service workers (Wild et al., 2020). The situation is further compounded by the delivery method and content of the interventions. Stand-alone workshops on mental health, psychoeducational programs, or interventions that are only conducted over several days with significant gaps between them are generally suboptimal methods to facilitate long-term change in mental health outcomes for the general community and for first responders (Carleton et al., 2018; McCreary, 2019; Skeffington et al., 2016; Tan et al., 2020; Wild et al., 2020; Wild & Tyson, 2017; World Health Organization, 2022).

With respect to prevention efforts, attention should be given to first responders who are early in their career. In the general population, up to half of mental health disorders including mood, PTSD, and substance use develop by the age of 25 (Solmi et al., 2022). In first responders, rates of mental health problems and stress typically become higher the longer individuals are in service (Beyond Blue, 2018; Centre for Traumatic Stress Studies, 2017; Goh et al., 2021). The early period in a first responder’s career therefore appears to be a valuable window to provide skills and strategies to reduce the potential risk of later mental health problems. These skills could mitigate the psychological impact of stressors associated with their roles, whether that be potentially traumatic incidents, or operational and organisational stressors (e.g. shift work, resource issues, unsocial work hours) (Huddleston et al., 2007; Larsson et al., 2016; Lawn et al., 2020; Ricciardelli et al., 2020).

Accordingly, the Protecting Emergency Responders with Evidence-Based Interventions (PEREI) project comprises three programs to address these issues. The first program for early career members and volunteers is a modified version of internet-delivered cognitive training in resilience (iCT-R) (Wild et al., 2018). iCT-R targets modifiable risk factors for PTSD and depression, first identified in prospective research with first responders (Wild et al., 2016). iCT-R utilizes tools drawn from cognitive therapy for PTSD (Ehlers et al., 2005), depression (Watkins et al., 2011), and social anxiety disorder (Clark et al., 2023), and assists members in practicing skills for modifying risk factors, such as rumination, unhelpful resilience appraisals, unwanted memories, self-focused attention, worry, and negative imagery. Organizational support and culture, mental health stigma, and supervisor relationships has a significant influence on first responders’ wellbeing (Boag-Munroe et al., 2016; Carleton et al., 2020; Haugen et al., 2017; Larsson et al., 2016; Lawn et al., 2020; Lawrence et al., 2018; Ménard et al., 2016). Thus, the second program, for supervisors (PEREI-S), equips supervisors within the services with skills to identify and provide appropriate levels of support for members, as well as strategies in building workplaces and relationships that buffer their teams from the stressors of the role. Finally, given the impact of the first responder role on their social networks and the critical role social support might confer in protecting individuals from mental health challenges (Guilaran et al., 2018; Vig et al., 2020), a universal mental health promotion program, the Be Well Plan (van Agteren et al., 2021b), will be adapted for the first responder context and offered to early career members’ significant others and support people (BW-SO).

2. Research aims and hypotheses

Our primary aim is to test the efficacy of modified iCT-R for members, which we predict will result in fewer cases of probable-PTSD and depression and less severe symptomatology relative to Standard Practice (SP). We hypothesise that participants with PTSD and depression symptoms at baseline allocated to iCT-R will demonstrate a significant reduction in symptoms post-program relative to individuals allocated to SP, with gains maintained at follow-ups. We predict that iCT-R will result in improvement at post-program and follow-up relative to SP on a range of secondary measures This includes resilience, trauma-related beliefs, symptoms of anxiety, sleep difficulties, alcohol use, wellbeing, anger, work satisfaction, stress, quality of life, and healthcare use. A second aim is to evaluate the efficacy of the supervisor program (PEREI-S). We hypothesise that supervisors in PEREI-S will show improved knowledge of mental health, managerial confidence and competence, and will report behaviours associated with creating effective working environments relative to those in the SP group. The third aim is to utilize an extensive assessment battery to improve our understanding of moderating and mediating factors associated with outcomes. For example, we will test whether modified iCT-R results in lower symptom scores at post-program and follow-up than SP for those at greater risk (e.g. higher levels of early childhood and other trauma, low social support). We will examine whether improvements in unhelpful trauma-related cognitions and emotion regulation mediate symptom levels immediately after iCT-R and at follow-up. Undertaking a program focused on improving managerial skills around mental health may confer benefits to supervisors in PEREI-S. Accordingly, improvements in their own wellbeing (and symptom reduction, for those with elevated symptoms) will be documented. We will also examine whether program dose, participation level and practice, and reported helpfulness of content influences outcomes. Our fourth aim is to pilot the feasibility of the significant other program (BW-SO). Assuming sufficient numbers for analysis, relative to SP (controls) we predict that BW-SO participants will show significant improvements in wellbeing and quality of life over time. We expect improvements relative to controls on secondary measures, such as symptoms of PTSD, depression, anxiety, and sleep difficulties.

3. Design and methods

3.1. Overview

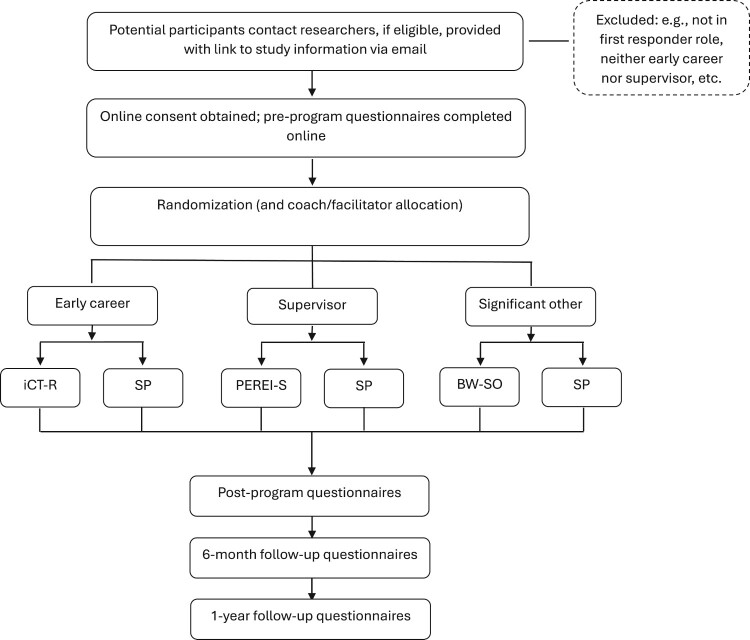

The study is a pragmatic RCT with two arms (intervention, standard practice) and three participant groups of focus. The protocol follows CONSORT guidelines for reporting randomized trials, and the design aims to minimize risk of bias in such a trial. The first target group will comprise early career members (N = 380–450) from emergency services within the state of South Australia who will be randomized to modified iCT-R or SP (Figure 1). The second target group will consist of supervisors (N = 150–180) in the emergency services, to be randomized to PEREI-S or SP. The third group is exploratory and will consist of significant others of early career members who will be randomized to BW-SO or SP (control). All participants complete measures prior to their respective program, during, and at 1-week post-program (or on drop out), and at 6- and 12-months follow-up. Participants allocated to SP will be asked to wait one year before being offered the intervention. The study runs from December 2022 to June 2025.

Figure 1.

Study overview and timeline. iCT-R = modified internet-delivered Cognitive Training in Resilience program; PEREI-S = Supervisor program; BW-SW = Be Well Plan – Significant Other program; SP = Standard Practice.

3.2. Participants, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

Participants will be recruited from emergency services in South Australia. Participants (early career) will be eligible if they are active-duty members within their first 5 years of service, which includes trainees. They will come from services including police, firefighters, and paramedics. Significant others/family members will be eligible if over 18 years of age and have a first responder participating in the member program. Supervisors are eligible if working in a service partnered with the project and have some portion of their role associated with line-management/supervisor duties. Supervisors can participate regardless of whether they supervise a first responder who is part of the members program. Participants will be excluded if they are experiencing mental health issues or serious social difficulties for which they prefer treatment.

3.3. Sample size calculation

Between 380 and 450 early career recruits (190–225 per group) will be randomized across the two conditions for the evaluation of iCT-R. This sample size is sufficient to detect a risk reduction of probable PTSD and depression by 50% between iCT-R and standard practice with an OR of 0.52 and with between 80% and 85% power (allowing for 20% attrition, α = .05). The study has at least 85% power to detect 0.30 standard deviation (SD) difference between groups on symptom measures (i.e. PCL-5 [Weathers et al., 2013b], PHQ-9 [Kroenke et al., 2001]). We anticipate larger differences in supervisor managerial variables based on prior work (Gayed et al., 2019) and have 80% power to detect a 0.45 SD difference between groups with 20% attrition (N = 150–180 required). Sample sizes for early career and supervisor groups are sufficient to detect small between-within effects over time (power = .80, α = .05, across four assessment points).

3.4. Randomization and blinding

Due to the pragmatic nature of the trial and services to be involved, randomization considers the operational context of different emergency services. Where members and supervisors operate out of fixed units/stations across the state, balanced (1:1) randomization of sites will occur within the service-defined region. For example, the volunteer fire service operates in six regions across the state, with separate brigades (stations) ‘grouped’ within a region. These brigades will be recognised as discrete units of analysis and randomly allocated to PEREI or SP. Where members do not operate out of defined co-located sites or unit (e.g. paramedic trainees), simple parallel assignment (1:1 ratio) using block randomization will be used. Significant others will be allocated to the member’s condition. Randomization sequences are computerized and created by an individual independently of the research team. Participants complete pre-program questionnaires and will be informed of their allocation after questionnaire completion. Participants and researchers cannot be unaware of their allocation following randomization due to the study design (intervention vs. SP). Assessments at each measurement point will be completed online independently of the research team and procedures for contacting participants will be the same, ensuring some mitigation of bias.

3.5. Interventions

3.5.1. Modified internet-delivered Cognitive Training in Resilience (iCT-R) for members

The member program consists of an Australian adaptation of internet-delivered cognitive training in resilience (iCT-R) (Wild et al., 2018). For the Australian context, the modules were updated to local vernacular and some video material recreated to include Australian first responders. Information is delivered in seven modules. Modules focus on upskilling participants with practice of how to modify cognitive processes related to risk for PTSD and depression in their line of work (see Table 1 for module titles). Thus, the modules target self-focused attention, rumination, unhelpful resilience appraisals, unwanted memories, suppression, worry, avoidance, and negative imagery. Modules include information, questions to answer, experiential exercises, whiteboard videos to explain concepts, audio files, and video testimonies. The Australian modification comprises an additional module focussing on skills for improved communication, effective use of social support, time-management, and positive health behaviours (e.g. optimising sleep around shift work).

Table 1.

Program summaries.

| iCT-R | BW-SO | PEREI-S |

|---|---|---|

| 1. It Matters What You Focus On: Helpful and Unhelpful Attention | 1. A Foundation to Start Your Be Well Plan | 1. What is Mental Health and Common Issues in First Responders |

| 2. Get Out of Your Head with Helpful Thinking | 2. Using Your Mental Health Profile to Tailor Your Plan | 2. Conversations about Mental Health |

| 3. Habits and Overthinking: How to Change Them | 3. Resources and Challenges for Your Mental Health and Wellbeing | 3. Creating Healthy and Resilient Workplaces |

| 4. Dealing with Unwanted Memories: Then versus Now. | 4. Coping and Resilience During Tough Times | 4. Helping Those You’re Concerned About |

| 5. Transforming Worries and Improving Performance | 5. Living your Be Well Plan | |

| 6. Work and Your Health a | 6. Living with and Supporting a First Responder a | |

| 7. Beating Stress and Trauma: My Blueprint |

Note: iCT-R = modified internet-delivered Cognitive Training in Resilience program; BW-SO = Significant Other program; PEREI-S = Supervisor program.

Module added for the current study.

Members will receive one module per week that they will complete independently (∼25–40 min to complete). They will receive support from a wellbeing coach who provides asynchronous email feedback and prompts based on members’ responses during the course. After the program, the coach continues this check-in monthly for six months with a brief reminder to practice a core skill. Wellbeing coaches will be independent of the service, possess at least undergraduate qualifications in a mental health field, attend one day of training, and will receive regular supervision.

3.5.2. PEREI-Supervisor program (PEREI-S)

The supervisor program involves four weekly 1-hour seminars (see Table 1). Topics addressed will include domains that preliminary research suggests can influence supervisor behaviours, with possible impacts on wellbeing and mental health of employees, including first responders (Beyond Blue, 2018; Gayed et al., 2018b; World Health Organization, 2022). The program covers a range of topics including (a) information regarding the content and rationale of the early career program, (b) identification of poor mental health and how to have conversations around wellbeing (c), tips to manage the consequences of critical incidents, (d) factors supervisors can influence in the workplace that promote wellbeing and minimise stress and burnout, (e) methods to reduce stigma and promote help-seeking, and (f) general strategies in communicating and supporting members around mental health. Seminars will involve information sharing, brief exercises, and group discussions. Supervisors will be asked to practice a skill or undertake relevant exercises between sessions. Supervisors can also complete the modified iCT-R if they wish.

Supervisor sessions will be delivered live via videoconferencing in small groups (≤10) and can include a mix of participants from different emergency services. The seminars will ensure consistency of messaging and ongoing promotion of a wellbeing framework from an organisational context. Seminars will be conducted by experienced registered mental health professionals with an understanding of emergency service organisational frameworks and culture.

3.5.3. Be Well Plan Significant Other program (BW-SO)

Significant supports (i.e. family members, partners) of early career members will have access to a mental health promotion program. This program has been modified from an existing five-session live-facilitated group-based program (the Be Well Plan [Fassnacht et al., 2022; van Agteren et al., 2021b; 2021c]) to a six-session online module program. It will be delivered in a similar fashion to modified iCT-R (i.e. with asynchronous coaching, see Table 1). The BW-SO program is a tailored approach that allows a person to identify their wellbeing goals and choose from several evidence-based strategies and skills to foster resilience to stress and mental wellbeing. The modules cover a range of topics including mindfulness, self-compassion, adaptive coping, resilience skills, increasing social support, adaptive thinking or reframing, and consideration of values. An additional module is added to (a) provide information of signs of mental health issues relevant to first responder roles, and (b) the ways that people can interact and support individuals in these roles to assist in buffering them from the impact of this work. Modules have interactive components and exercises, short videos, and informative text. Participants can assess their current wellbeing status via a web app (Be Well Tracker), used in conjunction with the program. Participants receive coaching and follow-up in the same manner as those in iCT-R; this coach will be different from that provided to the member.

3.5.4. Standard Practice (Control)

For the early career and supervisor groups, this condition involves standard practice and support within the service. All service staff and volunteers have access to wellbeing and mental health initiatives (e.g. web-based information), as well as informal (e.g. peer) and formal support. The organizations offer some training for supervisors around mental health in varying degrees (e.g. mental health aid first training). Significant others are free to engage in any support they seek. All participants in the SP group will be offered the respective program after the final follow-up.

3.6. Fidelity and monitoring

Coaches will be trained by the developers of the respective programs and will receive weekly supervision. Participant adherence and online module completion will be monitored through the software platform (Qualtrics). Supervisor attendance and task completion will be recorded. Independent raters will assess the content of a random sample of email feedbacks to members and significant others, to ensure fidelity to program components. Delivery of the supervisor program follows a standardized set of slide content and exercises. For confidentiality and organizational reasons, and to ensure openness of discussions, supervisor sessions will not be recorded.

3.6.1. Primary outcome measures

Our primary outcome for early career members will be indexed using established measures: probable-PTSD (PCL-5) (Bovin et al., 2016; Weathers et al., 2013b) and depression (PHQ-9) (Kroenke et al., 2001). The PCL-5 and PHQ-9 will be used with clinical cut-offs (≥ 31 and ≥10 respectively) to determine probable-PTSD and depression caseness with continuous scores used to index symptom severity. Supervisor and significant other primary outcomes are listed in Table 2 reflecting, broadly, supervisory competence and wellbeing.

Table 2.

Outcomes, measures, and assessment schedule.

| Primary outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain | M | S | SO | Measure | Time point* |

| PTSD | √ | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (Weathers et al., 2013b) | Pre, Mid, Post, FUs | ||

| MDD | √ | Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (Kroenke et al., 2001) | Pre, Mid, Post, FUs | ||

| Wellbeing and resilience | √ | Brief Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (Tennant et al., 2007) | Pre, Post, FUs | ||

| √ | Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985) | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| Brief Resilience Scale (Smith et al., 2008) | Pre, Mid, Post, FUs | ||||

| Wagnild Resilience Scale (Wagnild & Young, 1993) | Pre, Post, FUs | ||||

| Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale-10 (Campbell-Sills & Stein, 2007) | Pre, Post, FUs | ||||

| Anxiety | Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (Spitzer et al., 2006) | Pre, Mid, Post, FUs | |||

| Anger | Dimensions of Anger Reactions (Forbes et al., 2014) | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| Depression | Male Depression Risk Scale (Herreen et al., 2022) | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| Health | Insomnia Severity Index (Bastien et al., 2001) | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Saunders et al., 1993) | Pre, Post, FUs | ||||

| Smoking items from ASSIST (Humeniuk et al., 2008) | Pre, Post, FUs | ||||

| Cognitions | Posttraumatic Cognitions Inventory (Foa et al., 1999) | Pre, Mid, Post, FUs | |||

| Emotional regulation | Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale-18 (Victor & Klonsky, 2016) | Pre, Mid, Post, FUs | |||

| Quality of life, health economics | Australian Quality of Life-4-D (Hawthorne et al., 1999) | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| ICEpop CAPability measure for Adults (Al-Janabi et al., 2012) | Pre, Post, FUs | ||||

| Treatment Inventory of Costs/iMTA Questionnaire (Bouwmans and et al. 2013) | Pre, Post, FUs | ||||

| Absence, sick days, compensation claims b | Pre, Post, FUs | ||||

| Social support | Two-way Social Support Scale (Shakespeare-Finch & Obst, 2011) | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| Perception of supervisor/organisation support | Psychosocial Safety Climate Scale (Hall et al., 2010) b | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| Health and Safety Executive Management Standards Indicator Tool – adapted member version (Toderi & Sarchielli, 2016) a | Pre, Post, FUs | ||||

| Organisational and operational stress | Organizational and Operational Police Stress Questionnaires (McCreary & Thompson, 2006) b, c | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| Job satisfaction | Job Satisfaction Scale (Cooper et al., 1989) b | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| Supervisor response to mental health and knowledge | √ | Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Management Standards Indicator Tool – adapted version (Toderi & Sarchielli, 2016) d | Pre, Post, FUs | ||

| √ | Supervisor confidence and stigma questionnaires (Gayed et al., 2018a) d | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| √ | Mental Health Knowledge Schedule (Evans-Lacko et al., 2010) d | Pre, Post, FUs | |||

| Trauma exposures | Adverse Childhood Experiences (Felitti et al., 1998) | Pre | |||

| Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (Weathers et al., 2013a) | Pre, Post, FUs | ||||

| Traumatic incidents**, a | Weekly | ||||

| General adjustment | Outcome Rating Scale (Miller & Duncan, 2000) **, a, e | Weekly | |||

| Demographics | Study-specific measure | Pre | |||

Note. Completed by all participants unless specified. M = Member; S = Supervisor; SO = Significant other.

*Pre = prior to randomization; Mid = mid-program; Post = 1-week post-program; FUs = 6 & 12-month follow-ups.

**Weekly during program (immediately prior to program module).

Completed by members.

Completed by / relevant to members and supervisors.

Appropriate for use with all first responder professions.

Completed by supervisors.

Completed by significant others.

3.6.2. Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes include resilience, wellbeing, social support, trauma-related beliefs, symptoms of anxiety, sleep difficulties, alcohol use, anger, and work satisfaction (see Table 2). General adjustment will be indexed weekly during the program (early career members, significant others) and early career members will report on weekly trauma exposure. Potential moderators include demographic factors, social support, trauma history, and whether supervisor or significant other also completed a program (for early career members, subject to data availability). Trauma cognitions and emotion regulation will be examined as potential mediators.

3.7. Stakeholder engagement

An Advisory Group consisting of representatives of the service organisations, including management and wellbeing staff will be formed. It will provide advice on all aspects of the study from design, implementation, interpretation of results, and dissemination of findings. The group will meet every two months during the active phase of the project (lead-up, recruitment, program delivery) and at least three times in the following year. In addition, end-users (members, supervisors, and significant others) will provide guidance and feedback on draft program materials. Prior iterations of iCT-R and BW-SO programs have received rigorous input from stakeholders in their development (Fassnacht et al., 2022; van Agteren et al., 2021b; Wild et al., 2018; Wild & Tyson, 2017).

3.8. Procedure

Potential participants will be informed of the study through information sessions by the researchers, via internal communications with the services, social media, and the study website. Interested participants contact the researchers, and if eligible (confirmed via email or phone), are sent a link to access the full participation information materials online and complete informed consent. Participants can request further information via email or telephone before consenting. Following informed consent, participants will complete pre-program questionnaires online (via Qualtrics platform), with the platform automatically randomizing them to condition. Those eligible for the iCT-R or BW-SO program will be automatically sent their first module and allocated a wellbeing coach. SP participants will be sent an email informing them of their allocation and a reminder of the subsequent assessment schedule. Supervisors will be automatically informed of their allocation. Those randomized to receive the supervisor program immediately are contacted to allocate them to the next available group, with SP participants informed via email of the assessment schedule. Following respective program completion, participants complete the assessment questionnaires 1-week post-program, and at 6- and 12-months follow-up. SP participants complete questionnaires at matching assessment time-points. We will record where possible reasons for program withdrawal and/or assessment noncompletion.

3.9. Data and risk management

All participation information and questionnaire data will be captured online via the Qualtrics platform. Participants will be assigned a unique ID. Access to systems containing sensitive information will be restricted to key study staff. Study-related adverse events are not anticipated. If participant risk or clinical concerns are identified, participants will be assessed via telephone and appropriate referrals made. Serious adverse events (SAE) that could be potentially study-related will be documented and reported to the research ethics committee and service partners.

3.10. Statistical analyses and costs

In line with CONSORT guidelines, data analysis will be intent-to-treat (ITT). All participants will be included in analyses including those who drop out. Program non-completers will be invited to participate in all subsequent assessments to minimise missing data. Differences in rates of probable-PTSD and MDD diagnoses at post-intervention, 6, and 12 months follow-up will be tested with logistic mixed effects models. Multilevel models (MLM) will be used to assess the longitudinal data (primary and secondary outcomes), including relevant factors (e.g. individuals in metropolitan vs. regional locations). MLM approaches are an appropriate method for analysing intervention-type outcome trials, with robust methods of handling missing data (Schafer & Graham, 2002) and accounting for non-independence of observations attributable to hierarchies within the data (e.g. assessments nested within first-responders, sites) (Bosker & Snijders, 2011). To assess the clinical significance of change, specific cut-off scores are used (reported under Measures). Chi-squared tests will be used where only single follow-up data are collected (e.g. dropout rate).

Potential moderating effects of baseline predictors (e.g. early childhood and other trauma exposure, social support) will be examined on main outcomes of interest (PTSD and depression severity) within models. Proposed mediators will examine whether changes in unhelpful trauma-related cognitions, emotion regulation, practice of skills, and compliance with the program mediate PTSD and depression symptom levels post-program and at follow-ups. In line with reporting standards and to minimize Type 1 error when documenting a range of secondary outcome measures, effect sizes will be reported throughout. These are more clinically meaningful than p values, are unaffected by the number of outcome measures, and when replicated, even small effects can have important real-world implications (Funder & Ozer, 2019).

The base case economic evaluation will be presented from a health system perspective and include intervention costs, healthcare costs and change in Quality-Adjusted Life-Years (QALYs) based on utilities derived from the AQoL-4D (Hawthorne et al., 1999). We will also present the cost per capability QALY based on the ICECAP-A (Al-Janabi et al., 2012) and include a broader societal perspective. Health care utilization will be captured from the TiC-P questionnaire (Bouwmans & et al, 2013), with items associated with a public health care cost (e.g. general practitioner) included in the health system perspective. For the societal perspective, costs will additionally include other services accessed identified in the TiC-P (e.g. social worker) and loss of productivity from absenteeism and compensation claims. Costs will be presented in AUD 2021–2 prices. Probabilistic sensitivity analyses will be conducted. This will be presented in table form and with cost-effectiveness acceptability curves to consider the mean and the distribution of outputs based on adjusted analyses to indicate the probability of cost-effectiveness against the estimated opportunity cost for Australia (Edney et al., 2018) and for a range of plausible thresholds up to $75,000 per additional QALY.

4. Discussion

We have described the rationale, methods, and importance of a RCT that will test the efficacy of programs to protect first responders from the potential mental health challenges posed by their role. Our focus on early career emergency service workers and volunteers is important. This career stage represents a critical time where members can learn effective techniques to mitigate the risk of significant stressors and impacts of trauma inherent in their roles. A key goal is to provide a buffer for members from the cumulative effects of operational stress and trauma that can occur over their careers. The responsibility for first responders’ well-being should not rest solely on the individual (McCreary, 2019), with services having both an ethical and, in Australia, a legislative duty to reduce the psycho-social risks employees face in their workplace (Work Health and Safety, 2023). Supervisors play a highly influential role in fostering wellbeing and resilience in their teams. They therefore represent an important mechanism through which organizations can support their staff and volunteers in what are rewarding, yet demanding roles.

Our project is novel in that it seeks to achieve its aims through three arms, working with early career members, service supervisors, and those who are significant supports to the member. Our study has considerable strengths in its approach and methodology, with a holistic lens, offering programs to multiple stakeholders impacted directly and indirectly by first responders’ work. All the programs being tested are built on the latest evidence-base of what we know improves wellbeing and resilience to mental ill health. They address modifiable factors that substantial research has shown to influence wellbeing and mental health challenges such as anxiety, depression, and PTSD (Gayed et al., 2018b; van Agteren et al., 2021a; Wild et al., 2016; 2018; World Health Organization, 2022). As we have done in the past, refinement of programs will continue in close collaboration with stakeholders and end-users, to ensure their acceptability and ease of use. The randomized design, coupled with significant follow-up (one-year post-program) adds to the strength of the study. This is essential since our target group is generally quite healthy, thus shorter follow-up periods may not detect true preventive effects for problems that can take time to develop. Our assessment battery is comprehensive, indexing psychopathological outcomes, wellbeing, resilience, functional outcome, as well as quality of life, social support, and health care costs. Although our primary hypotheses focus on efficacy questions (do the programs work?), we have deliberately adopted an assessment battery to answer questions around influential moderating and mediating factors on outcomes and the value of the program. In our consultations to date, our users and stakeholders have raised these very questions, underscoring their importance: for whom will these programs be most effective, what factors might enhance or impede their effectiveness, and what processes may underlie their effectiveness? Answers to these questions offer a data-driven approach to making such interventions more precise and effective. Economic evaluation will consider whether the programs offer value for money to inform policy and potential funding models. In a time when service budgets are stretched, economic evaluation of services should be used to support funding prioritisation.

We acknowledge limitations to the study design. For resource and practical reasons, we will not index psychopathology with standardized clinical interviews. Participants will self-report health and mental health service utilization; due to limited organization capacity, we cannot access records on the range and intensity of use of service-provided wellbeing initiatives. Participation is voluntary; thus, it is possible those who engage are not representative of the broader target group. Relatedly, although the individual programs will be rigorously evaluated, we are unlikely to be able to compare outcomes where members had both a supervisor and significant other participate versus when this did not occur. We will aim to obtain basic demographic and work characteristics from the services on their staff (e.g. age, gender, length of service) to enable broad judgements on representativeness of our sample but will not have fine-grained or other potentially relevant information of non-participants (e.g. baseline wellbeing or psychopathology levels).

The PEREI project represents a large and methodologically rigorous mixed-service study of a prevention program designed to improve resilience to mental ill health for early career emergency service personnel and volunteers. With its inclusion of service supervisors and significant others, the undertaking of extensive stakeholder engagement, coupled with a methodologically rigorous design, the project will advance our understanding of optimal methods to improve resilience to the development of mental health problems in emergency services personnel.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable advice and contributions of our Advisory Group Committee and others (alphabetically): Jane Abdilla; Andrew Chandler; Karla Chou; Jane Cooper; Shane Johnson; Brett Loughlin; Tammy Moffat; Carol Snellgrove; Lucas Stubing; Alex Turnbull. We thank the participating services for their collaboration: South Australian Country Fire Service, South Australian Metropolitan Fire Service, and the South Australia Police Service. Internet-delivered cognitive training in resilience (iCT-R) was developed by Jennifer Wild, Gabriella Tyson and Anke Ehlers at the University of Oxford and funded by MQ, the Wellcome Trust, and the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre. The Be Well Plan was developed by Joep van Agteren, Daniel B Fassnacht, Matthew Iasiello, Kathina Ali and Gareth Furber and a wider group of academic and professional collaborators, supported by the South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute (SAHMRI) Be Well Co, Flinders University and a philanthropic grant by the James and Diana Ramsay Foundation. The authors wish to thank Dr Gabriella Tyson, King’s College London, for her assistance in making the iCT-R materials available for use in Australia. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not represent the views of the funder or the services partnered with the research.

Funding Statement

The research is funded by the Movember and The Distinguished Gentleman’s Ride Veterans and First Responders Mental Health Grant Program, Breakthrough Mental Health Research Foundation, and Flinders University.

Disclosure statement

JvA is a director of Be Well Co., which generates revenue from the Be Well Plan. The remaining authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Al-Janabi, H., Flynn, T. N., & Coast, J. (2012). Development of a self-report measure of capability wellbeing for adults: The ICECAP-A. Quality of Life Research, 21(1), 167–176. 10.1007/s11136-011-9927-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien, C. H., Vallières, A., & Morin, C. M. (2001). Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Medicine, 2(4), 297–307. 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyond Blue . (2018). Answering the call Beyond Blue’s National Mental Health and wellbeing study of police and emergency services – final report.

- Boag-Munroe, F., Donnelly, J., van Mechelen, D., & Elliott-Davies, M. (2016). Police officers’ promotion prospects and intention to leave the police. Policing (Bradford, England), 11(2), paw033–paw145. 10.1093/police/paw033 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosker, R., & Snijders, T. A. (2011). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modelling. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwmans, C., De Jong, K., Timman, R., Zijlstra-Vlasveld, M., Van der Feltz-Cornelis, C., Tan, S. S., & Hakkaart-van Roijen, L. (2013). Feasibility, reliability, and validity of a questionnaire on healthcare consumption and productivity loss in patients with a psychiatric disorder (TiC-P). BMC Health Services Research, 13(1), 217. 10.1186/1472-6963-13-217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovin, M. J., Marx, B. P., Weathers, F. W., Gallagher, M. W., Rodriguez, P., Schnurr, P. P., & Keane, T. M. (2016). Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1379–1391. 10.1037/pas0000254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Sills, L., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Psychometric analysis and refinement of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC): Validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(6), 1019–1028. 10.1002/jts.20271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R. N., Korol, S., Mason, J. E., Hozempa, K., Anderson, G. S., Jones, N. A., Dobson, K. S., Szeto, A., & Bailey, S. (2018). A longitudinal assessment of the road to mental readiness training among municipal police. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 47(6), 508–528. 10.1080/16506073.2018.1475504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R. N., Afifi, T. O., Turner, S., Taillieu, T., Vaughan, A. D., Anderson, G. S., Ricciardelli, R., MacPhee, R. S., Cramm, H. A., Czarnuch, S., Hozempa, K., & Camp, R. D. (2020). Mental health training, attitudes toward support, and screening positive for mental disorders. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 49(1), 55–73. 10.1080/16506073.2019.1575900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centre for Traumatic Stress Studies . (2017). MFS health & wellbeing study. University of Adelaide.

- Clark, D. M., Wild, J., Warnock-Parkes, E., Stott, R., Grey, N., Thew, G., & Ehlers, A. (2023). More than doubling the clinical benefit of each hour of therapist time: A randomised controlled trial of internet cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder. Psychological Medicine, 53(11), 5022–5032. 10.1017/S0033291722002008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C. L., Rout, U., & Faragher, B. (1989). Mental health, job satisfaction, and job stress among general practitioners. BMJ, 298(6670), 366–370. 10.1136/bmj.298.6670.366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edney, L. C., Haji Ali Afzali, H., Cheng, T. C., & Karnon, J. (2018). Estimating the reference incremental cost-effectiveness ratio for the Australian health system. Pharmacoeconomics, 36(2), 239–252. 10.1007/s40273-017-0585-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Hackmann, A., McManus, F., & Fennell, M. (2005). Cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: Development and evaluation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(4), 413–431. 10.1016/j.brat.2004.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko, S., Little, K., Meltzer, H., Rose, D., Rhydderch, D., Henderson, C., & Thornicroft, G. (2010). Development and psychometric properties of the mental health knowledge schedule. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(7), 440–448. 10.1177/070674371005500707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassnacht, D. B., Ali, K., van Agteren, J., Iasiello, M., Mavrangelos, T., Furber, G., & Kyrios, M. (2022). A Group-facilitated, internet-based intervention to promote mental health and well-being in a vulnerable population of university students: Randomized controlled trial of the be well plan program. JMIR Mental Health, 9 (5), e37292. 10.2196/37292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., Koss, M. P., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00017-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Tolin, D. F., & Orsillo, S. M. (1999). The posttraumatic cognitions inventory (PTCI): Development and validation. Psychological Assessment, 35(3), 140–151. 10.1037/pas0001190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, D., Alkemade, N., Mitchell, D., Elhai, J. D., McHugh, T., Bates, G., Novaco, R. W., Bryant, R., & Lewis, V. (2014). Utility of the dimensions of anger reactions-5 (DAR-5) scale as a brief anger measure. Depression and Anxiety, 31(2), 166–173. 10.1002/da.22148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. 10.1177/2515245919847202 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy, L. B. (2020). Swimming upstream: The first responder’s marriage. In Mental health intervention and treatment of first responders and emergency workers (pp. 16–31). IGI Global. 10.4018/978-1-5225-9803-9.ch002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gayed, A., et al. (2019). A cluster randomized controlled trial to evaluate HeadCoach: An online mental health training program for managers. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 61(7), 545–551. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayed, A., Bryan, B. T., Petrie, K., Deady, M., Milner, A., LaMontagne, A. D., Calvo, R. A., Mackinnon, A., Christensen, H., Mykletun, A., Glozier, N., & Harvey, S. B. (2018a). A protocol for the HeadCoach trial: The development and evaluation of an online mental health training program for workplace managers. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), article 25. 10.1186/s12888-018-1603-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayed, A., Milligan-Saville, J. S., Nicholas, J., Bryan, B. T, LaMontagne, A. D, Milner, A., Madan, I., Calvo, R. A., Christensen, H., Mykletun, A., Glozier, N., & Harvey, S. B. (2018b). Effectiveness of training workplace managers to understand and support the mental health needs of employees: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 75(6), 462–470. 10.1136/oemed-2017-104789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh, K. K., Jou, S., Lu, M. L., Yeh, L. C., Kao, Y. F., Liu, C. M., & Kan, B. L. (2021). Younger, more senior, and most vulnerable? Age and job seniority on psychological distress and quality of life among firefighters. Psychological Trauma, 13(1), 56–65. 10.1037/tra0000662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilaran, J., de Terte, I., Kaniasty, K., & Stephens, C. (2018). Psychological outcomes in disaster responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of social support. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science, 9(3), 344–358. 10.1007/s13753-018-0184-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, G. B., Dollard, M. F., & Coward, J. (2010). Psychosocial safety climate: Development of the PSC-12. International Journal of Stress Management, 17(4), 353–383. 10.1037/a0021320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haugen, P. T., McCrillis, A. M., Smid, G. E., & Nijdam, M. J. (2017). Mental health stigma and barriers to mental health care for first responders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 94, 218–229. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawthorne, G., Richardson, J., & Osborne, R. (1999). The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instrument: A psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Quality of Life Research, 8(3), 209–224. 10.1023/a:1008815005736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herreen, D., Rice, S., & Zajac, I. (2022). Brief assessment of male depression in clinical care: Validation of the Male Depression Risk Scale short form in a cross-sectional study of Australian men. BMJ Open, 12(3), e053650. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-053650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston, L., Stephens, C., & Paton, D. (2007). An evaluation of traumatic and organizational experiences on the psychological health of New Zealand police recruits. Work, 28, 199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humeniuk, R., Ali, R., Babor, T. F., Farrell, M., Formigoni, M. L., Jittiwutikarn, J., & Simon, S. (2008). Validation of the alcohol, smoking and substance involvement screening test (ASSIST). Addiction, 103(6), 1039–1047. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02114.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaffa, K., Openshaw, L., Koch, J., Clark, H., Harr, C., & Stewart, C. (2015). Impact of Police Work on Relationships. The Family Journal, 23(2), 120–131. 10.1177/1066480714564381 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., & Williams, R. L. (2001). The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 16(9), 606–613. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson, G., Berglund, A. K., & Ohlsson, A. (2016). Daily hassles, their antecedents and outcomes among professional first responders: A systematic literature review. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(4), 359–367. 10.1111/sjop.12303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn, S., Roberts, L., Willis, E., Couzner, L., Mohammadi, L., & Goble, E. (2020). The effects of emergency medical service work on the psychological, physical, and social well-being of ambulance personnel. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s12888-020-02752-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D., Kyron, M., Rikkers, W., Bartlett, J., Hafekost, K., Goodsell, B., & Cunneen, R. (2018). Answering the call: National survey of the mental health and wellbeing of police and emergency services. Detailed report. Graduate School of Education, The University of Western Australia.

- McCreary, D. R. (2019). Veteran and first responder mental ill health and suicide prevention scoping review: Programs in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, & United Kingdom.

- McCreary, D. R., & Thompson, M. M. (2006). Development of two reliable and valid measures of stressors in policing: The operational and organizational police stress questionnaires. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(4), 494–518. 10.1037/1072-5245.13.4.494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ménard, K. S., Arter, M. L., & Khan, C. (2016). Critical incidents, alcohol and trauma problems, and service utilization among police officers from five countries. International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 40(1), 25–42. 10.1080/01924036.2015.1028950 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S. D., & Duncan, B. L. (2000). The outcome rating scale. [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardelli, R., Czarnuch, S., Carleton, R. N., Gacek, J., & Shewmake, J. (2020). Canadian public safety personnel and occupational stressors: How PSP Interpret stressors on duty. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4736–4716. 10.3390/ijerph17134736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, J. B., Aasland, O. G., Babor, T. F., De La Fuente, T. R., & Grant, M. (1993). Development of the alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction, 88(6), 791–804. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147–177. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Obst, P. L. (2011). The development of the 2-way social support scale: A measure of giving and receiving emotional and instrumental support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(5), 483–490. 10.1080/00223891.2011.594124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeffington, P. M., Rees, C. S., Mazzucchelli, T. G., & Kane, R. T. (2016). The primary prevention of PTSD in firefighters: Preliminary results of an RCT with 12-month follow-up. PLoS One, 11(7), e0155873–22. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. 10.1080/10705500802222972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solmi, M., Radua, J., Olivola, M., Croce, E., Soardo, L., de Pablo Salazar, G., Shin, J. I., Kirkbride, J. B., Jones, P., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. Y., Carvalho, A. F., Seeman, M. V., Correll, C. U., & Fusar-Poli, P. (2022). Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Molecular Psychiatry, 27(1), 281–295. 10.1038/s41380-021-01161-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L., Harvey, S. B., Deady, M., Dobson, M., Donohoe, A., Suk, C., Paterson, H., & Bryant, R. (2020). Workplace mental health awareness training: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine, 63(4), 311–316. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2007). The Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(1), 1–13. 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toderi, S., & Sarchielli, G. (2016). Psychometric properties of a 36-Item version of the stress management competency indicator tool. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(11), 1086. 10.3390/ijerph13111086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Agteren, J., Iasiello, M., Lo, L., Bartholomaeus, J., Kopsaftis, Z., Carey, M., & Kyrios, M. (2021a). A systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological interventions to improve mental wellbeing. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(5), 631–652. 10.1038/s41562-021-01093-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Agteren, J., Ali, K., Fassnacht, D. B, Iasiello, M., Furber, G., Howard, A., Woodyatt, L., Musker, M., & Kyrios, M. (2021b). Testing the differential impact of an internet-based mental health intervention on outcomes of wellbeing and psychological distress in COVID-19. JMIR Mental Health, 8(9), e28044. 10.2196/28044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Agteren, J., Iasiello, M., Ali, K., Fassnacht, D. B., Furber, G., Woodyatt, L., Howard, A., & Kyrios, M. (2021c). Using the intervention mapping approach to develop a mental health intervention: A case study on improving the reporting standards for developing psychological interventions. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648678. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor, S. E., & Klonsky, E. D. (2016). Validation of a brief version of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS-18) in five samples. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(4), 582–589. 10.1007/s10862-016-9547-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vig, K. D., Mason, J. E., Carleton, R. N., Asmundson, G. J. G., Anderson, G. S., & Groll, D. (2020). Mental health and social support among public safety personnel. Occupational Medicine, 70(6), 427–433. 10.1093/occmed/kqaa129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and Psychometric Evaluation of the Resilience Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1(2), 165–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, E. R., Mullan, E., Wingrove, J., Rimes, K., Steiner, H., Bathurst, N., Eastman, R., & Scott, J. (2011). Rumination-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy for residual depression: Phase II randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(4), 317–322. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.090282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers, F. W., Blake, D. D., Schnurr, P. P., Kaloupek, D. G., Marx, B. P., & Keane, T. M. (2013a). The Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5), 2013, www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013b). The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). www.ptsd.va.gov.

- Wild, J., El-Salahi, S., Tyson, G., Lorenz, H., Pariante, C. M., Danese, A., Tsiachristas, A., Watkins, E., Middleton, B., Blaber, A., & Ehlers, A. (2018). Preventing PTSD, depression and health problems in student paramedics: protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open, 8(12), bmjopen-2018-022292–10. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild, J., El-Salahi, S., & Esposti, M. D. (2020). The effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving well-being and resilience to stress in first responders. European Psychologist, 25(4), 252–271. 10.1027/1016-9040/a000402 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wild, J., Smith, K. V., Thompson, E., Béar, F., Lommen, M. J. J., & Ehlers, A. (2016). A prospective study of pre-trauma risk factors for post-traumatic stress disorder and depression. Psychological Medicine, 46(12), 2571–2582. 10.1017/S0033291716000532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild, J., & Tyson, G. (2017). Evaluation of a new resilience intervention for emergency service workers.

- Work Health and Safety . (2023). Work Health and Safety (Psychosocial Risks) Amendment Regul., (SA)

- World Health Organization . (2022). World Health Organization guidelines on mental health at work. [Google Scholar]