Abstract

Background

The prevention of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) is recognised as a health care priority in the UK. In people living with T2DM, lifestyle changes (e.g. increasing physical activity) have been shown to slow disease progression and protect from the development of associated comorbidities. The use of digital health technologies provides a strategy to increase physical activity in patients with chronic disease. Furthermore, behaviour economics suggests that financial incentives may be a useful strategy for increasing the maintenance and effectiveness of behaviour change intervention, including physical activity intervention using digital health technologies. The Milton Keynes Activity Rewards Programme (MKARP) is a 24-month intervention which combines the use of a mobile health app, smartwatch (Fitbit or Apple watch) and financial incentives to encourage people living with T2DM to increase physical activity to improve health. Therefore, this randomised controlled trial aims to examine the long-term acceptability, health effects and cost-effectiveness of the MKARP on HbA1c in patients living with T2DM versus a waitlist usual care comparator.

Methods

A two-arm, single-centre, randomised controlled trial aiming to recruit 1018 participants with follow-up at 12 and 24 months. The primary outcome is the change in HbA1c at 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in markers of metabolic, cardiovascular, anthropometric, and psychological health along with cost-effectiveness. Recruitment will be via annual diabetes review in general practices, retinal screening services and social media. Participants aged 18 or over, with a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and a valid HbA1c measurement in the last 2 months are invited to take part in the trial. Participants will be individually randomised (1:1 ratio) to receive either the Milton Keynes Activity Rewards Programme or usual care. The intervention will last for 24 months with assessment for outcomes at baseline, 12 and 24 months.

Discussion

This study will provide new evidence of the long-term effectiveness of an activity rewards scheme focused on increasing physical activity conducted within routine care in patients living with type 2 diabetes in Milton Keynes, UK. It will also investigate the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Trial registration

ISRCTN 14925701. Registered on 30 October 2023.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13063-024-08513-y.

Keywords: Physical activity, Type 2 diabetes, Financial incentives, Routine care, mHealth, Digital health

Introduction

Physical activity and type 2 diabetes

The growing number of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a major worldwide public health concern [1]. In the UK, 3.7 million people are living with T2DM and there are a further 12 million people at high risk of developing this disease [2]. T2DM is a leading cause of preventable sight loss in people of working age [3, 4] and is a major contributor to heart attacks and strokes [5]. As well as the human cost, T2DM treatment accounts for around 10% of the annual NHS budget [6].

Modifiable factors including physical inactivity and an unhealthy diet, are thought to be major drivers for the development of T2DM [7], with 80–90% of all cases preventable or reversed through healthy lifestyle behaviours [8, 9]. Physical activity offers many health benefits for adults, including reduced risk of T2DM and other related chronic conditions such as obesity [10]. For those living with T2DM, physical activity is associated with improved secondary indicators of risk of T2DM disease progression (i.e. increases in HbA1c, blood pressure, BMI, and blood lipids) and protects against complications such as heart disease and stroke [11, 12].

Most physical activity interventions aim to achieve at least 150–300 min of moderate-intensity physical activity or 75 min of vigorous activity, and/or 2–3 sessions of resistance training per week [13, 14]. In the context of adults living with T2DM, for some outcomes (e.g. HbA1c and blood pressure) there is evidence for a stronger effect with more aerobic activity (i.e. greater benefits with more than 150 min/week compared to less than 150 min/week) [11]. However, adherence to this level of physical activity can be difficult for many adults. Individuals with T2DM are usually well below the recommended level of physical activity and are more likely to spend a large amount of time sedentary [15]. The dose–response data clearly show that adults with the lowest levels of physical activity have the most to gain from even small increases in physical activity [16, 17]. Therefore, innovative behavioural interventions targeting improvements in physical activity and sedentary behaviour in patients with T2DM are needed.

Mobile health, financial incentives to increase physical activity

Recent advances in technology provide an avenue to develop innovative behavioural interventions. Given a large proportion of the population is insufficiently physically active and reports high volumes of sedentary time [18, 19], we need interventions with wide reach and low or limited healthcare professional input; this objective can be achieved through mobile health (mHealth) interventions. Mobile health interventions include smartphone apps in conjunction with wearable technology to change behaviour. The use of technology to deliver lifestyle interventions has grown markedly over the past decade [20]. The introduction and evaluation of novel digital technologies, particularly with a focus on the promotion of healthy lifestyles, is a priority for the UK Government [21], as shown by the pilot of the Better Health: Rewards programme in the general population [22].

mHealth interventions offer some key advantages over traditional behaviour change interventions. They can reach many people at a relatively low cost and offer increased access to the public at a time and place that suits their preferences [23], including the ability to overcome the need to attend face-to-face sessions to receive the intervention [24]. As an approach with wide reach, smartphone-based interventions are very attractive as 90% of mobile phone users have it with them for the much of the day. mHealth technology can be used by people of different ages and cultural backgrounds and studies have shown that people report that electronic devices that promote physical activity are acceptable [25, 26].

Wearable activity monitors (consumer devices that provide feedback to the wearer such as ‘fitness trackers’ and activity-tracking smartwatches), can also help promote physical activity. These devices are affordable to many [27], visually appealing and user friendly [28], encourage the integration of non-structured physical activity (e.g. walking) into daily living and reduce barriers associated with structured or organised forms of physical activity [29]. Wearable activity monitors promote behaviour change techniques, such as self-monitoring and goal setting [30]. Their use has been associated with increased physical activity [23, 31] may be effective in conjunction with other behaviour change techniques to increase intervention effectiveness, for example financial incentives.

The use of financial incentives as a behaviour change technique has its basis in behavioural economics, a branch of economics complemented by insights from psychology, that has been used to promote physical activity [32]. Often referred to as ‘temporal discounting’, how an individual values a reward (e.g. better health) decreases the further away in time the reward is realised [33, 34]. Put another way, people tend to respond more to the immediate costs and benefits of their actions than to those experienced in the future. In the case of physical activity, the cost of the behaviour (e.g. time and perceived discomfort) is usually experienced in the present and thus overvalued, while the benefits (e.g. health and longevity) are often delayed and thus discounted, tipping daily decisional scales towards physical inactivity. According to behavioural economics, immediate incentives may be useful in emphasising a short-term physical activity benefit and motivating more people to be active [35, 36].

Evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials has shown that financial incentives were associated with increases in mean daily step count [37]. However, nearly all of the RCTs found in this meta-analysis were from the USA, which has a significantly different culture and healthcare system to the UK [38] and how such intervention would work in the NHS remains unclear. Furthermore, the majority of trials were short to medium-term in duration (i.e. no follow-up longer than 6 months) therefore long-term impact on behaviour change remains unknown [37].

Consequently, evidence in the UK is lacking. The RAND Corporation examined whether the uptake of the Vitality (private health insurance) Active Rewards with Apple Watch benefit is associated with increased physical activity levels for Vitality members [39]. Whilst the Active Rewards programme was associated with a 34% increase in monitored activity days per month (i.e. 4.8 days of activity per month), the use of private health insurance is for a specific population and this method of behaviour change has not been assessed in a public health setting [39], although research is ongoing [40]. Furthermore, it is unclear what the health benefits are of such a programme and whether they are cost-effective interventions.

Finally, whilst current evidence does suggest that financial incentives may be effective in increasing physical activity in North America and for those who can afford private healthcare insurance, the NICE ‘Evidence Standards framework for digital health technologies’ in the UK health and social care system requires high-quality interventional studies to support the claimed benefits for the digital health technologies, including showing improvements in relevant clinical or patient-relevant outcomes [24].

Milton Keynes activity rewards programme

The Milton Keynes Activity Rewards Programme (MKARP) is a 24-month intervention which combines the use of a mobile health app (EXI app: https://www.exi.life/), wearable technology (Fitbit or Apple watch) and financial incentives (up to £365 per year) to encourage people living with T2DM to increase participation in physical activity to improve health. Briefly, the MKARP provides users with a ‘physical activity prescription’ (weekly physical activity goals for minutes of moderate-vigorous physical activity and the number of steps). If users are successful at completing their physical activity prescription, users will earn financial rewards in the form of vouchers.

Therefore, this randomised controlled trial aims to examine the long-term (24 months) acceptability, health effects (clinical and patient-relevant outcomes) and cost-effectiveness of the MKARP on HbA1c in patients living with T2DM versus a usual care waitlist group. The trial will include an internal pilot to assess recruitment, randomisation, compliance with the primary outcome and retention rate at 3 months follow-up prior to proceeding to full trial.

Objectives

Primary objective

To determine the effectiveness of an intervention (MKARP) that includes access to a mobile health app, wearable activity monitor, and financial incentives to promote physical activity, versus usual care on HbA1c in patients living with type 2 diabetes at 12 months.

Secondary objective(s)

To determine the effect of the MKARP intervention versus usual care on health-related quality of life at 12 months.

To identify the effect of a mobile health app, linked composite endpoints of HbA1c reduction ≥ 0.5% + weight loss ≥ 1 kg and SBP reduction ≥ 3 mmHg at 12 and 24 months follow-up.

To determine the difference in the composite endpoints in the usual care (waitlist control group) pre-post intervention delivery.

To determine the effect of the intervention on key secondary outcomes including weight, total physical activity minutes, blood pressure, and blood lipids at 12 and 24 months.

To determine participants' engagement with the interventional components, and to understand which socio-demographic factors are associated with poorer engagement.

To assess the cost-effectiveness of the delivery of this digital health and financial incentive intervention to the NHS.

Methods

Overview

A 24-month two-arm randomised controlled trial with an internal pilot study comparing an intervention group with a ‘waitlist’ usual care group that will be embedded in routine diabetes care in Milton Keynes (MK), a local authority area in England, UK. The efficacy of the intervention to reduce HbA1c will be supported by an economic evaluation and a process evaluation described in more detail below. A nested qualitative study will also be included. We aim to recruit 1018 participants over a 15-month period from January 2024 to April 2025.

The study is following protocol version 5.1. Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust in England are the sponsor for this trial. This protocol adheres to the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) reporting recommendations [41] (see Supplemental material 1).

Trial design and setting

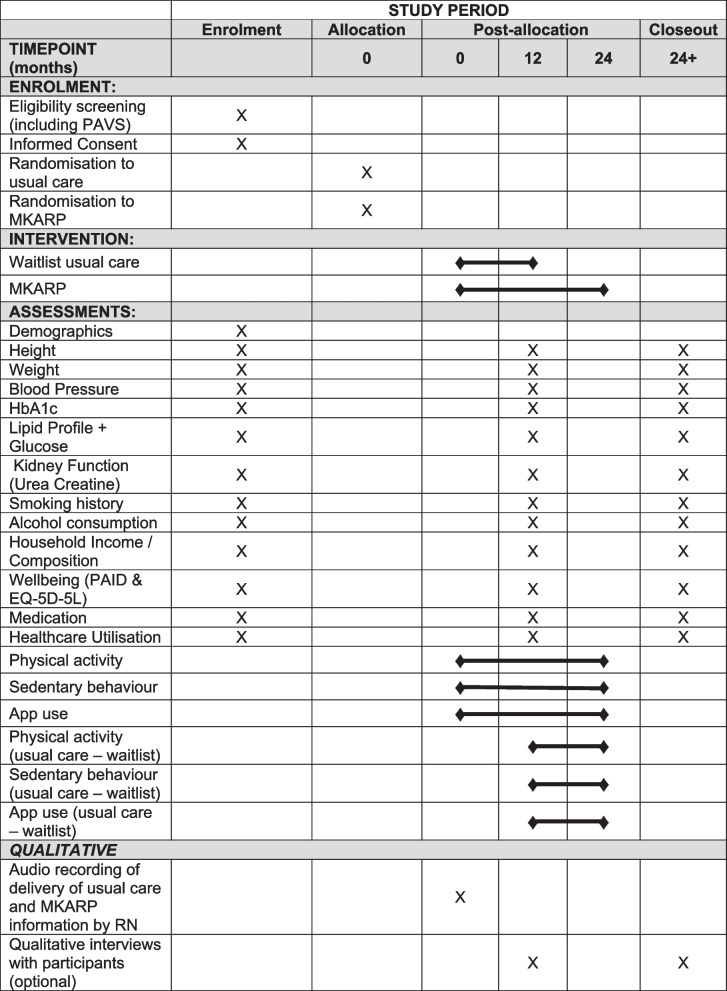

Participants will be randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the MKARP intervention or waitlist usual care. The randomisation will be stratified by age, self-reported gender, and recruitment pathway. Participants in the intervention arm will be enrolled for 24 months with the primary outcome to be assessed at 12 months. Waitlist usual care participants will be provided with the intervention at 12 months and followed up for a further 12 months. All participants will be in the study for a total of 24 months. The 24-month follow-up for the intervention arm will allow for the longer-term effects of the intervention to be processed. A flow diagram showing the trial design is given in Fig. 1. A SPIRIT figure shows the different data collection steps of the trial (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Participant flow. PAVS, physical activity vital signs; PIS, participants information sheet; EOI, expression of interest

Fig. 2.

SPIRIT figure. HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; PAVS, physical activity vital signs; PAID, problem areas in diabetes

Recruitment to the trial will be from NHS T2DM primary care services within the Milton Keynes area, with patients being recruited before their annual diabetes review (a yearly check of health outcomes such as blood pressure, cholesterol, kidney function and weight). In addition, recruitment will be through NHS retinal screening (a yearly check by a diabetic eye screening service) as well as community settings, including via social media. In MK, around 90% of patients are managed in the community, by their general practitioner (GP), i.e. most people with T2DM in MK, it is the responsibility of the GP rather than the hospital-led integrated diabetes service to undertake the annual review to determine patients’ disease progression and medication requirements.

Patient and public involvement (PPI)

PPI consists of a group of patient advocates from Milton Keynes University Hospital as well as members from Diabetes UK Milton Keynes branch. PPI input has informed the development of the study since inception. Insights and feedback gathered from group discussions with PPI members enabled the development of research questions, assessment of potential burdens on participants and informed the intervention materials to make sure they were user-friendly. Continuation of PPI involvement will inform the intervention delivery and dissemination of results to the wider community as appropriate.

Identification and recruitment of participants

There are approximately 17,000 people in MK with a recorded diagnosis of T2DM. All general practices in Milton Keynes will be invited to identify patients for this study. Participating practices choosing will search their electronic records to identify patients who are ≥ 18 years old and have had a valid HbA1c measurement in the past 3 months (blood tests for HbA1c levels closely precede annual diabetes review) or are likely to have one soon. These patients will be sent a trial invitation text message which will include a tiny URL directing patients to the participant information sheet (PIS), Expression of Interest form (EOI) and the Physical Activity Vital Signs (PAVS) questionnaire [42]. The EOI will ask patients to confirm their eligibility for participation in the study. The PAVS will be used to screen for physical activity guideline compliance (150 min of MVPA per week) as the study will only recruit those who, via self-report, do not meet current UK Physical Activity Guidelines [43]. Those interested will be asked to return their completed documents to the study team at Milton Keynes University Hospital (MKUH).

Participants will also be recruited via NHS retinal screening services. All patients with type 2 diabetes in the UK will be offered a retinal scan every year to check for diabetic retinopathy. Patients with type 2 diabetes who come through these clinics in Milton Keynes will be provided with a leaflet/business card with details about the trial and a quick-response (QR) code linking to the online PIS and EOI to assess eligibility.

Finally, potential participants can be invited to take part in the study via community settings, including through advertising on social media. Social media post will include a QR code which will direct to the online EOI to determine eligibility.

Consent

Potential participants will provide consent for all parts of the screening process described above, and if eligible consent to participate in the trial. Electronic informed consent to take part in the trial will be obtained for each participant before any measures are taken. Where electronic consent is not possible, verbal or written consent will be taken. Participants will be made aware at the beginning of the study that they can freely withdraw (discontinue participation) from the trial (or part of it) at any time without giving a reason.

Patient eligibility

Inclusion criteria

◾ Aged ≥ 18 years

◾ Diagnosis of type 2 diabetes (based on WHO criteria, e.g. HbA1c ≥ 48 mmol/mol or 6.5%)

◾ Has had an HbA1c blood measurement taken in the last 3 months

◾ Able to provide informed written consent.

◾ Own and use a smartphone capable of hosting the EXI app (i.e. Android 10 and above (usually Android phones purchased after 2019) or Apple iOS 15.0 or above (usually an iPhone purchased after 2020)).

◾ Consent to participants’ GP being notified of their participation in the trial.

◾ Self-reporting as being able to be physically active

◾ Milton Keynes resident

Exclusion criteria

◾ Unable to understand English sufficiently to complete the trial assessments.

◾ Women known to be pregnant or breastfeeding.

◾ Do not own/cannot operate a smartphone or have a smartphone that cannot be upgraded to Apple iOS 15.0 and above (usually in iPhones purchased after 2020) or Android 10 and above (usually Android phones purchased after 2019).

◾ Life-limiting condition that will affect the ability to be physically active within the period of the trial.

◾ Chronic health conditions significantly affecting mobility.

◾ Currently meeting UK physical activity guidelines of 150 min of moderate to vigorous physical activity per week as determined by the Physical Activity Vital Signs questionnaire.

◾ Participants in live-in care, residential homes or other institutional settings that will limit their ability to be active.

Randomisation

Once eligibility has been confirmed participants will be randomised at the level of the individual (1:1 ratio) to receive either the MKARP intervention or usual care. A minimisation algorithm will be used within the secure online randomisation system to ensure balance in the treatment allocation over the following variables:

◾ Route of recruitment (general practice, other community health service, other)

◾ Age group (18–45, 46 + years)

◾ Self-reported gender (male, female, non-binary)

Participants will be informed that they have been allocated to either the intervention arm (i.e. receive written information about physical activity and access to the EXi app and accompanying smartwatch, as well as financial incentives) or usual care (waitlist) when the intervention is delivered. Randomisation will be performed by the trials research nurse.

Blinding

The trial data scientist will be blinded to allocation until after the completion of the final analyses via account permission limiters on the study database. The participants will be aware that they will be randomised to either the intervention or usual care, therefore no blinding can take place.

Milton Keynes activity rewards programme

MKARP intervention consists of four components: brief consultation with a diabetes research nurse (RN), EXI mobile app, Apple Watch or Fitbit watch (hereafter referred to as smartwatch), and financial incentives.

Brief consultation

Upon randomisation, the research team will contact participants to arrange a time for a Diabetes Research Nurse (RN) from MKUH to deliver the intervention/waitlist usual care. Participants randomised to the intervention group will receive standard guidance about the importance of physical activity and will be advised on the details of the MKARP.

The intervention delivery will consist of the following:

◾ Description of the importance of physical activity in the management of type 2 diabetes through NHS consultations with an NHS health professional.

◾ Overview of three components of the MKARP (EXi app, smartwatch and financial incentives).

◾ Discussion of the EXi app and how it can help participants to increase their physical activity.

◾ The purpose of the EXi app and the smartwatch for facilitating self-monitoring and feedback on physical activity will be discussed and the use of the intervention will be specifically encouraged.

The RNs will be trained to promote the rationale for the intervention and the benefits of physical activity for health and explain implementation plans and action planning. See below for details on training.

An intervention checklist will be completed by the RN to aid delivery and provide a reminder prompt of areas that must be covered during consultations. We anticipate the delivery of the MKARP intervention to the participants will take 2–3 min per consultation and will be delivered either online or over the telephone. The role of the RN is to simply raise the topic of physical activity, to signpost participants to the EXi app for further advice and support, and to encourage participants to use their smartwatch device to facilitate their engagement with physical activity and to obtain feedback.

With the consent of participants, a sub-sample of the consultations will be audio-recorded to assess for fidelity. of delivery by nurses.

Training of research nurse to deliver the intervention

Research nurse(s) will be trained by the research team and representatives from EXI to deliver the MKARP intervention. EXI has developed a media-based training module that can be delivered face-to-face or remotely. The training will be delivered in person or online based on the preference of the RN. We will also demonstrate the functions of the EXI app during the training. The training takes no more than 1 h given the involvement of RNs is simple and brief. The training tools include information on the importance of adhering to the study protocol, the research study procedures, trial design and ways of delivering the MKARP.

A range of strategies to reinforce intervention fidelity will be used. We will:

◾ Train RNs to deliver the intervention per protocol.

◾ Audio record 10% of consultations and telephone calls with an RN using an encrypted dictaphone (or secure and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) compliant online conferencing tools) to assess whether the intervention is being delivered according to a checklist (with participant consent);

◾ Use of a standardised training resource.

◾ Check for intervention ‘receipt’.

Eximobile app and exercise prescription

EXI: Exercise Intelligence (https://www.exi.life/) is a digital therapeutic platform specialising in personalised, progressive physical activity prescriptions and remote monitoring for individuals living with, or at risk of, long-term health conditions. The platform provides an individual physical activity prescription for each user, based on their demographics, current physical activity level and health conditions. Prescriptions progress the user each week, with the goal of the user reaching and maintaining the physical activity guidelines. Prescriptions detail the frequency (times per week), intensity (low, moderate or high, based on heart rate), and duration (minutes per day) that the user should complete. The EXI platform is optimised when connected to any wearable activity monitor, e.g. Apple Watch or Fitbit. Participants can monitor their activity intensity while completing the activity via the EXI app, while the wearable activity monitor also tracks their physical activity, enabling users to view their progress towards their goals in the EXI app (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

EXI app and Apple Watch

EXi and behaviour change

Behavioural science is embedded throughout the EXI platform. The user experience and user interface have been developed with careful consideration of the evidence regarding the specific challenges to physical activity behaviour change faced by those living with chronic health conditions such as type 2 diabetes [44–46], and frameworks such as the Behaviour Change Wheel approach [47] have been applied to link app features to identified psychosocial determinants of physical activity in this population. The behaviour change techniques (BCTs) implemented within the EXI platform are underpinned by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [48]. Examples of BCTs delivered through the platform include; ‘Goal setting—behaviour’, ‘Self-monitoring of behaviour’, ‘Biofeedback’, ‘Social support’, ‘Graded tasks’, and ‘Prompts & cues’. Additionally, the platform has the capability to deliver ‘Material incentive (behaviour)’ and ‘Material reward (behaviour)’, providing financial rewards for users.

Financial reward

Participants who complete their physical activity prescription receive a financial reward. The smartwatch is used to monitor participants’ physical activity, using wrist-based heart rate sensing to ensure the physical activity is of the correct intensity. Participants can receive feedback during the activity about the intensity of the activity and whether they are in the target zone. Participants can receive up to £365 yearly (or £91.25 a quarter or £1 a day). To achieve a financial reward, participants must achieve at least 60% of their goal (e.g. goal of 10,000 steps, participants must achieve at least 6000 steps). The level of their financial reward is then dependent on their progression toward their overall activity goal (60% achieved equals 60% of max reward; 72% achieved = 72% of max reward). Rewards are earned each week and then banked and will contribute to their quarterly earnings. The rewards will be earned in the form of vouchers. This value of reward is based on previous research which has suggested that modest incentives of (approximately £1 a day) can increase physical activity for interventions in the short and long term [37].

The EXI platform ‘starts where you’re at’, creating an ability for everyone to achieve rewards, regardless of current fitness level. For example, participants’ prescriptions can start with as little as 10 min of low-intensity activity three times per week and build up gradually over time to hitting physical activity guidelines. It has been shown that aligning physical activity goals with incentives can increase the achievement of goals by as much as 200% over 24 months [49]. See Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

EXI rewards portal

Waitlist usual care comparator

The usual care group will only receive the current UK guidance for physical activity (infographic on the benefits of physical activity and physical activity recommendations) within their annual diabetes review consultation at baseline. Current UK guidance advises working towards the accumulation of at least 150-min MVPA per/week. There will be no change to standard care, therefore the waitlist usual care group will receive the normal physical activity advice. In addition and in line with standard care for patients with diabetes locally, participants in the control arm will be given information on local opportunities to be active (AMKERS: Active Milton Keynes Exercise Referral Scheme; and local options for physical activity promoted through LEAP) and signpost national resources (Sport England and This Girl Can). With the consent of participants, the delivery of the usual care information will be audio-recorded in a random 10% sample to assess fidelity and intervention contamination. The usual care group will be offered the intervention at 12 months.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome will be the difference in HbA1c (%) between the intervention and waitlist usual care groups at 12 months.

Secondary outcome

Secondary outcomes include:

◾ The mean difference in quality of life as measured by EQ-5D-5L between the intervention and waitlist usual care arms at 12 months.

◾ The efficacy endpoints of participants in the intervention group achieving the composite endpoint of HbA1c reduction > 0.5% + weight loss > 3% and SBP reduction > 3 mmHg at 12 months between the intervention and waitlist usual care group.

◾ The difference in composite endpoints pre- and post-intervention delivery in the waitlist usual care group.

◾ Physical activity trajectories (direction and rate of change in physical activity over time) in the intervention group from baseline to 12 months.

◾ The mean difference in other blood biomarkers including blood lipid panel, blood glucose, and kidney function tests between the intervention and waitlist usual care at 12 months.

◾ Changes in healthcare utilisation (visits to primary or secondary healthcare) in the intervention and waitlist usual care group at 12 months.

◾ Changes in diabetes medication used in the intervention and waitlist usual care group at 12 months.

◾ The mean difference in Problem Areas in Diabetes Score / EQ-5D-5L scores between the intervention and control group at 12 months.

Data collection

Primary outcome measures

As part of the annual diabetes review, patients are requested to attend a health check and provide a blood sample. HbA1c will be measured from this blood sample, data will be retrieved from SystmOne. Participants will not be asked or expected to have additional blood tests as part of the trial.

Secondary outcomes measures

Outcomes collected at the annual diabetes review

Other data from the annual diabetes review health check and blood sample include height, weight, blood pressure, resting pulse as well as blood lipids, and kidney function tests. This data will also be retrieved from SystmOne. Finally, current medications (name and dosage) and healthcare utilisation (total, diabetes-related) will also be collected, via SystmOne and Hospital Episode Statistics respectively.

Additional secondary outcomes

Diabetes distress (also known as diabetes-specific distress or diabetes-related distress) is an emotional response to living with diabetes, the burden of continual daily self-management and (the prospect of) its long-term complications. The Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) is a 20-item questionnaire, widely used to assess diabetes distress [50]. Health-related quality of life is measured using The EuroQol (EQ-5D 5L) and includes questions on mobility, hygiene, daily activities, pain/ discomfort and anxiety/depression [51]. Physical activity self-efficacy will also be measured using a validated questionnaire [52]. To determine cost-effectiveness, questionnaire items will be used to assess healthcare resource use in terms of patients attending primary and secondary care facilities. All questionnaire instruments will be delivered in digital format as standard. Paper copies are made available to participants upon request.

Physical activity throughout the intervention will be measured by the smartwatch. Metrics collected will include sedentary time, participation in light-moderate and vigorous physical activity (mins), as well as heart rate (bpm), steps and fitness (as determined by the self-guided 6-min walk test).

Cost-effectiveness evaluation

The economic evaluation will assess whether the MKARP, compared to waitlist usual care will likely be cost-effective at commonly used threshold values. The economic analysis consisted of a cost-consequences analysis which will be based on observed results with the trial and a cost-effectiveness analysis in which the difference between groups in the trial will be extrapolated to the longer term. To facilitate this, resource use estimates will be collected during each assessment point using a health-related resource use questionnaire. The questionnaire is based on a variant of the Client Services Receipt Inventory and includes services that this population are likely to use, such as GPs and practice nurse appointments, occupational health visitors and counsellors. Additionally, data on healthcare utilisation will be retrieved from SystmOne. A range of trial outcomes will be assessed as part of this economic evaluation, including HRQoL as measured by the EQ-5D-5L.

Process measures

The process evaluation aims to examine any discrepancies between expected and observed outcomes, increase our understanding of the influence of each intervention component and context on the observed outcomes, and provide insight for any further intervention development and implementation. Throughout the trial, the implementation fidelity, dose, attrition, adaptation, contamination, barriers and facilitators, using the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework [53] will be monitored.

Furthermore, engagement with the intervention and, examine the demographic profile of the participants will be examined. Engagement with the EXi app will also be collected as a measure of intervention adherence and as a process measure. Data will be collected on the number of times users open the app, what aspects of the app they use and for how long.

Engagement by the participants with the EXI app and smartwatch will be examined and assessed via several process measures that may influence or explain the effectiveness of the app. For example, this may include the number of times participants access the app and the frequency of use of specific app features. Furthermore, the proportion of people who are continuing to use the app and smartwatch at 3, 6, 9, 12 and 24 months will be examined.

In addition, the participants that take part/enrol in the trial will be described in terms of age, sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES), and compared this to the eligible population, since there is preliminary evidence to suggest that digital health tools tend to be more frequently available and used by those in mid to high SES (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Summary of the process evaluation measures to be used

| Process evaluation | Definition | Data source | Time point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Context of the intervention | Contextual factors which affect the implementation | Initial discussion with GPs in MK | Pre-study |

| Focus groups with patients and HCPs | 12 month follow up | ||

| Fidelity | The extent to which the intervention was delivered as planned | Audio recording of the proportion of intervention delivery | Continuous |

| Internal monitoring of appointment attendance records | Post-study | ||

| Dose delivered/received | Dose delivered: the amount of the intervention that was provided by the app | EXi data reporting | Continuous |

| The dose received: How frequently participants engaged with the intervention | Follow-up questionnaires | 12 months | |

| Mechanism of impact | How does the intervention facilitate behaviour change | Follow-up questionnaires and interviews | 12 months |

| Contamination | Usual care receiving intervention-related information | Audio-recorded intervention delivery | Continuous |

| Sample vs population | How well the sample matches the general population of people living with type 2 diabetes in MK | Participant characteristics and patient characteristics of Milton Keynes | 12 months |

All participant data collected will be confidential and stored on secured servers.

Internal pilot

The trial will incorporate an internal pilot to examine issues surrounding participant recruitment, randomisation, compliance with the primary outcome and retention rate at 3 months follow-up.

Progression criteria

The following progression criteria will be reviewed by the independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) on the completion of the measurements collected from the participants (n = 255) who have been randomised within 3 months of the opening of recruitment. The trial will be considered eligible to progress to the main trial phase if the following internal pilot stop–go criteria are confirmed. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Progression criteria—traffic light

Adverse event reporting

Adverse events

There is no reason to assume that this trial will lead to an excess of adverse events. The intervention consists of RNs promoting physical activity within everyday life and the use of a digital health incentive platform with a smartwatch to monitor activity, along with financial incentives, none of which are likely to create harm. Furthermore, the promotion of physical activity by health professionals is already part of standard care and has been demonstrated as being low risk for all citizens in England as per the NHS Making Every Contact Count Campaign [40] without specific follow-up for adverse events. That said, information on adverse events will be collected from the participants. An adverse event will be defined as an untoward medical occurrence that does not necessarily have to be causally related to the study or intervention. Participants will be asked to inform us of any adverse events by email or phone.

Serious adverse events (SAE)

The research team at the site will report SAEs that are not defined as protocol-exempt in an expedited manner. The following are ‘protocol exempt’ SAEs: events related to the participant's pre-existing condition(s) (pre-existing conditions are medical conditions that existed before entering the trial, or for which they have already consulted medical advice, as identified on the baseline questionnaire (as per the diseases/conditions specified in Table 3)); and hospital visits for any elective procedures. Musculoskeletal and bone injuries/fractures, and trips and fall injuries are regarded as expected SAEs and are recorded on the follow-up case report forms.

Table 3.

Protocol exempts serious adverse event-related conditions

| ➢Cancer | ➢Sarcopenia (loss of muscle strength) | |

| ➢High blood pressure (hypertension) | ➢COPD/emphysema (Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) | |

| ➢Heart disease, heart attack, angina, aneurysm (cardiovascular disease) | ➢Kidney disease | |

| ➢Stroke | ➢Back pain resulting in time off work | |

| ➢Depression or anxiety | ➢Rheumatoid arthritis | |

| ➢Dementia or Alzheimer’s disease | ➢Osteoarthritis | |

| ➢Osteoporosis (thinning of the bones) | ➢Neurological condition (e.g. epilepsy, ME or MS) | |

| ➢Obesity | ➢COVID-19 | |

| ➢Asthma | ➢Foot/ankle problem affecting patient’s mobility |

Statistical consideration

The results of this trial will be reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement [54]. A full analysis plan will be prepared and finalised before any data analysis, and the trial registered with the ISRCTN registry of clinical trials (ISRCTN Number: 14925701).

Level of statistical significance

The results from the trial will be prepared as comparative summary statistics (differences in proportions or means) with 95% confidence intervals. All the inferential tests will be conducted using a 5% two-sided significance level.

Sample size

Physical activity programmes have been shown to lower HbA1c by 0.8% [55]. To detect a treatment difference of 0.25%, a clinically meaningful reduction, in HbA1c at 12 months, with a standard deviation for %HbA1c change of 1.1%, a sample size of 407 per arm would be required with a statistical power of 90%. This will allow for a comparison between the intervention arm and the usual care arm, maintaining an overall type one error rate of 5%. Five hundred nine participants will be randomised per arm to allow for a 20% dropout rate at 12 months follow-up.

Analysis of outcome measures

The primary statistical analysis of efficacy outcome (% change in HbA1c) will be carried out based on intention-to-treat (ITT). Full follow-up data on every participant will be sought to allow full ITT analysis, but missing data due to withdrawal and loss of follow-up will inevitably occur. Baseline data will be summarised by arm using descriptive statistics.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome is a change in %HbA1c at 12 months. The mean change in %HbA1c at 12 months between the intervention arm and control arm will be compared using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) adjusting for baseline %HbA1c and stratification variables (recruitment route, age group, gender). This will be the primary analysis for the trial. A pre-specified sub-group analysis will examine the effect of sex, age groups, ethnic group, deprivation quintile (score derived from postcode) and BMI.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome of the percentage achieving the following composite outcome of HbA1c reduction > 0.5% + weight loss > 3% and SBP reduction > 3 mmHg at 12 months. The composite outcome will be analysed using logistic regression, with the dependent variable defined as the number of participants achieving all endpoint targets for the composite outcome. The regression modelling will include adjustments for stratification variables. Other secondary outcomes including health-related quality of life, and blood lipid outcomes, will be analysed in the same ways as the primary outcome (ANCOVA).

Physical activity time-series analysis

Missing data will be inspected visually for patterns in the missing data. If missing data appears random then imputing data using appropriate techniques will be considered. Furthermore, autocorrelation may be present in time series datasets, where a measurement point is correlated with previous measurement points. We will utilise Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Averages with exogenous variable (ARIMAX) which will account for autocorrelation, as well as modelling the time-series data allowing for the assessment of the impact of the intervention over time whilst also accounting for covariates such as age, weight, SES.

Interview study

Qualitative interviews (participants)

To gain further insight into the processes involved in the intervention, we will invite participants to complete semi-structured interviews about their experiences at the end of the intervention. After participants have provided consent for this interview, questions asked informed by self-regulation and habit formation will focus on how easily they found the MKARP, barriers to being physically active, formation of habits and implementation strategies used, and the acceptability and usability of the technology. We expect to complete 20–25 interviews which should allow for saturation to be reached, as recommended for this type of trial [56]. Purposive sampling will enable the inclusion of participants who reflect as many socio-demographic characteristics of the possible eligible population (e.g. age, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, general PA behaviour), and display different levels of engagement and participation with MKARP to capture the range of views. Interviews will be audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using a framework approach [57].

As well as documenting individual and overall themes, theme comparisons will be carried out as appropriate, for example across socio-demographic characteristics and engagement levels. Findings will be interpreted against and combined with other study data. This will help to understand the intervention process and the participants’ experiences, allowing us to further refine the intervention as necessary [50].

Withdrawals

All study participants are informed verbally and in writing that they can withdraw their participant from the study at any time, without any need to justify their reason for doing so. The other criteria for discontinuation in the trial will be a change in the clinical status of the participants such that it might affect the outcomes of the study (e.g. for example pregnancy or cancer diagnosis and treatment).

Criteria for discontinuing intervention

As previously stated, there is no reason to suspect that this trial will lead to adverse events, serious or otherwise to participants. That said, if actual or potential harms are identified, the trial management group (see below) will report them to the Independent Trial Steering Committee, which will decide to consider suspending or terminating the trial.

Trial oversight and management

The Trial Management Group (TMG) will meet approximately once a month to ensure the successful implementation and delivery of the trial. The TMG consist of the PI, Clinical Lead (GP), evaluation lead, trial manager, and research governance officer. This group will monitor participant recruitment; any departure from the expected recruitment rate will be dealt with according to specific issues that arise. Day-to-day trial operation is led by the trial manager and research governance officer with assistance from the diabetes nurse and research administrator. This ‘day-to-day’ operations team will meet weekly. A joint independent Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring Committee (TSC/DMC) has been created for the trial. The TSC/DMC will meet at least twice a year or as required depending on the needs of the trial. The joint TSC/DMC will provide overall oversight of the trial, including the practical aspects of the trial as well as ensure that the trial is conducted in a way which is both safe for the participants and provides appropriate trial data to the sponsor and investigators. The joint TSC/DMC will consist of a consultant in diabetes, health economist, medical statistician, epidemiologist and a PPIE representative.

Trial status

The trial is currently registered to ISRCTN (14,925,701) and opened to recruitment in January 2024, and is expected to complete recruitment in April 2025. Black Country Research Ethics Committee have granted favourable ethical approval 23/WM/0167. The study is following protocol version 5.1. The company that provide the EXI app went in to administration in October 2024, forcing the study to pause recruitment.

Dissemination policy

We plan to publish the trial results in a peer-reviewed journal. Preliminary results may also be presented at international conferences, when appropriate. A summary of the results will also be made available for relevant stakeholders. Anonymised datasets will be made available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Discussion

There is strong evidence that insufficient levels of physical activity are associated with poorer health outcomes in patients living with type 2 diabetes [8, 9]. Previous evidence suggests that the combination of digital health tools and financial incentives can increase levels of physical activity in the short to medium term [39]. This RCT aims to implement a brief intervention along with digital health financial incentive intervention in patients living with type 2 diabetes in Milton Keynes, UK and to evaluate its long-term effectiveness (patient-relevant and clinical outcomes) and cost-effectiveness in reducing HbA1c. It is anticipated that if shown to be effective, the Milton Keynes Activity Rewards Programme could be scalable as a treatment resource by health organisations for patients living with type 2 diabetes.

The use of financial incentives to support behaviour change is unusual in UK healthcare settings Higher standards of evidence, i.e. randomised controlled trials, are needed to support their use. Financial incentives have been used in the UK healthcare system to encourage smoking cessation in pregnancy, following RCTs showing their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this approach [58–60].

To our knowledge, this is the first RCT to examine the impact of a multicomponent intervention (brief consultation plus digital health tool utilises personalised physical activity prescription and accompanying financial incentives) in patients with type 2 diabetes.

There are several strengths and limitations associated with the current protocol. Strengths of this study include the robust RCT design, and the randomisation protocol to reduce contamination. The large full-powered sample, objectively derived outcome measures and long-term follow-up assessment after the completion of the initial 12 months are further strengths along with the extensive process and economic evaluations. This is a single-centre study which enabled us to develop the study methodology quickly. Being locally driven and embedded in local systems (the study is a partnership between the hospital, primary care and the city council) will enhance our ability to recruit participants. However, the geography will also limit the total population we can recruit from Whilst recruiting from a discrete population may reduce generalisability, we note the population of Milton Keynes is not dissimilar from England as a whole [61]. The Milton Keynes population is slightly younger, is more ethnically diverse and has similar levels of diabetes compared to the rest of the UK [62]. Furthermore, the focus on type 2 diabetes may reduce generalisability to other groups of patients, for example, the high healthcare costs for type 2 diabetes may mean it is not straightforward to extrapolate the benefits to other patient groups.

Using clinical data from routine diabetes annual review has made for a more efficient design (reducing the need for additional clinic visits) but it may hinder recruitment (as recruitment is contingent on a recent appointment) and impact on data quality (if repeat visits are delayed, incomplete or missing). In keeping with NICE recommendations on the evaluation of digital technologies [63], we have a dual focus on patient-relevant (quality of life) and clinical (e.g. HbA1c). However, we will not be using research-grade device-based measures of physical activity in both arms at baseline and follow-up. Changes in physical activity are at an earlier stage in the causal pathway between the intervention and the desired outcomes, so might be considered a more sensitive measure of the intervention’s effects, as well as being a good proxy from which health outcomes and cost-effectiveness could be modelled. However, the use of the Apple Watch/Fitbit will provide longitudinal physical activity data which can be used to model changes over time in behaviour which would otherwise not be possible with a research grade device. Technology like this is rarely static. The app software is constantly evolving; nevertheless, the fundamental components of the intervention (incentives, activity monitoring and a mobile phone app) are fixed.

Our primary aim in designing the study has been to evaluate the overall effectiveness of the intervention, leading us to have only two arms. In part, this reflects the intervention being delivered as an integrated package, and it reflects that there is already strong evidence based around the use of devices (wearables) to promote physical activity [31, 64]. Consequently, the study will have no ability to measure which elements (brief consultation, smartwatch or financial incentives) of the intervention are effective or to make direct comparisons between the intervention and a cheaper version (e.g. app only or pedometers).

There is an urgent need for effective and scalable physical activity interventions for patients with diabetes which can be delivered in routine primary care [65]. If shown to be effective, both in terms of cost and health outcomes, the intervention could be implemented as part of standard primary care for patients with type 2 diabetes.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to the Milton Keynes University Hospital patient and public involvement and engagement group for their input into the trial.

Abbreviations

- AE

Adverse events

- ANCOVA

Analysis of covariance

- ARIMAX

Autoregressive Integrated Moving Averages with exogenous variables

- BMI

Body mass index

- COVID

Coronavirus disease

- EQ-5D-5L

EuroQol five dimension five levels

- HbA1c

Glycated haemoglobin

- ITT

Intention to treat

- MK

Milton Keynes

- MKARP

Milton Keynes Activity Rewards Programme

- NHS

National Health Service

- OS

Operating system

- PAID

Problem areas in diabetes

- PAVS

Physical activity vital signs

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- RN

Research nurse

- SAE

Serious adverse events

- SBP

Systolic blood pressure

- SES

Socio-economic status

- T2DM

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TSC/DMC

Trial Steering Committee/Data Monitoring Committee

- UK

United Kingdom

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

OM conceived of the intervention. JS and OM were involved in the design of the study and the development of the intervention materials. AD, DE, AC, JT, SH, AH, IS, IR, and AP contributed to the review of the study design and materials as well as the implementation of the programme and critically viewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. JS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. OM edited and revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Authors’ information

Centre for Lifestyle Medicine and Behaviour, School of Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences, Loughborough University, Loughborough, UK

James P. Sanders, Amanda J. Daley, Dale W. Esliger & Andrea Roalfe

NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, Leicester General Hospital, Gwendolen Road, Leicester UK

Dale W. Esliger

Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Standing Way, Eaglestone, Milton Keynes, UK

Antoanela Colda, Joanne Turner, Soma Hajdu, Ian Reckless, Asif M. Humayun, & Ioannis Spiliotis, Oliver Mytton

Whaddon Healthcare, 25 Witham Ct, Bletchley, Milton Keynes, UK

Andrew Potter

UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health, London, UK, Milton Keynes City Council, Milton Keynes, UK

Oliver Mytton

Trial registration

The trial is currently registered to ISRCTN (14925701. Registered 30th October 2023. https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN14925701

Funding

The ACTIVATE trial and Milton Keynes Activity Rewards Programme is funded by Milton Keynes City Council with support from Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. The ACTIVATE trial received 100 Apple Watch SE via the Apple Investigator Support Programme. OM is supported by a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/T041226/1)). AJD is supported by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Professorship award.

The study sponsor and funders were not involved in study design, data collection, management, analysis, writing of the report or the decision to submit this report for publication.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Black Country Research Ethics Committee have granted favourable ethical approval 23/WM/0167.

Consent for publication

N/a.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diab Res Clin Pract. 2022;183: 109119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diabetes UK. Number of people living with diabetes doubles in twenty years. 2018. Available from: https://www.diabetes.org.uk/about_us/news/number-people-living-diabetes-doubles-twenty-years. Cited 2023 Apr 26.

- 3.Bourne RRA, Jonas JB, Bron AM, Cicinelli MV, Das A, Flaxman SR, et al. Prevalence and causes of vision loss in high-income countries and in Eastern and Central Europe in 2015: magnitude, temporal trends and projections. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102(5):575–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Avogaro A, Fadini GP. Microvascular complications in diabetes: A growing concern for cardiologists. Int J Cardiol. 2019;291:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martín-Timón I, Sevillano-Collantes C, Segura-Galindo A, del Cañizo-Gómez FJ. Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: have all risk factors the same strength? World J Diab. 2014;5(4):444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHS England. NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme (NHS DPP). Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/diabetes/diabetes-prevention/. Cited 2024 Jan 3.

- 7.Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):88–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford ES, Bergmann MM, Kröger J, Schienkiewitz A, Weikert C, Boeing H. Healthy living is the best revenge: findings from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition-Potsdam study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1355–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mozaffarian D, Kamineni A, Carnethon M, Djoussé L, Mukamal KJ, Siscovick D. Lifestyle risk factors and new-onset diabetes mellitus in older adults: the cardiovascular health study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(8):798–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(24):1451–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

- 12.Liu Y, Ye W, Chen Q, Zhang Y, Kuo CH, Korivi M. Resistance exercise intensity is correlated with attenuation of HbA1c and insulin in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(1):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chase JAD. Interventions to increase physical activity among older adults: a meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2015;55(4):706–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conn VS, Hafdahl AR, Mehr DR. Interventions to increase physical activity among healthy adults: meta-analysis of outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(4):751–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2010.194381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrato EH, Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Ghushchyan V, Sullivan PW. Physical activity in US adults with diabetes and at risk for developing diabetes, 2003. Diab Care. 2007;30(2):203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kodama S, Tanaka S, Heianza Y, Fujihara K, Horikawa C, Shimano H, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diab Care. 2013;36(2):471–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadarangani KP, Hamer M, Mindell JS, Coombs NA, Stamatakis E. Physical activity and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in diabetic adults from Great Britain: pooled analysis of 10 population-based cohorts. Diab Care. 2014;37(4):1016–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowlands AV, Sherar LB, Fairclough SJ, Yates T, Edwardson CL, Harrington DM, et al. A data-driven, meaningful, easy to interpret, standardised accelerometer outcome variable for global surveillance. J Sci Med Sport. 2019;22(10):1132–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zenko Z, Willis EA, White DA. Proportion of adults meeting the 2018 physical activity guidelines for Americans according to accelerometers. Front Public Health. 2019;7(JUN):135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Romeo A, Edney S, Plotnikoff R, Curtis R, Ryan J, Sanders I, et al. Can smartphone apps increase physical activity? Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(3): e12053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department of Health and Social Care. New obesity treatments and technology to save the NHS billions. 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/new-obesity-treatments-and-technology-to-save-the-nhs-billions. Cited 2023 Jun 24.

- 22.Department of Health and Social Care. Government backs new scheme to improve people’s health in Wolverhampton. 2023. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/government-backs-new-scheme-to-improve-peoples-health-in-wolverhampton.

- 23.Mönninghoff A, Kramer JN, Hess AJ, Ismailova K, Teepe GW, Car LT, et al. Long-term effectiveness of mHealth physical activity interventions: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e26699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W, Bray NA, Williams SL, Duncan MJ, et al. Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: a systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Mercer K, Giangregorio L, Schneider E, Chilana P, Li M, Grindrod K. Acceptance of commercially available wearable activity trackers among adults aged over 50 and with chronic illness: a mixed-methods evaluation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2016;4(1): e4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang JB, Cataldo JK, Ayala GX, Natarajan L, Cadmus-Bertram LA, White MM, et al. Mobile and wearable device features that matter in promoting physical activity. J Mob Technol Med. 2016;5(2):2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Degroote L, Hamerlinck G, Poels K, Maher C, Crombez G, De BI, et al. Low-cost consumer-based trackers to measure physical activity and sleep duration among adults in free-living conditions: validation study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8(5):e16674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maher C, Ryan J, Ambrosi C, Edney S. Users’ experiences of wearable activity trackers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaddha A, Jackson EA, Richardson CR, Franklin BA. Technology to help promote physical activity. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119(1):149–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eckerstorfer LV, Tanzer NK, Vogrincic-Haselbacher C, Kedia G, Brohmer H, Dinslaken I, et al. Key elements of mhealth interventions to successfully increase physical activity: meta-regression. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(11):e10076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferguson T, Olds T, Curtis R, Blake H, Crozier AJ, Dankiw K, et al. Effectiveness of wearable activity trackers to increase physical activity and improve health: a systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4(8):e615–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Penguin; 2009.

- 33.Critchfield TS, Kollins SH. Temporal discounting: basic research and the analysis of socially important behavior. J Appl Behav Anal. 2001;34(1):101–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barlow P, Reeves A, McKee M, Galea G, Stuckler D. Unhealthy diets, obesity and time discounting: a systematic literature review and network analysis. Obes Rev. 2016;17(9):810–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loewenstein G, Asch DA, Volpp KG. Behavioral economics holds potential to deliver better results for patients, insurers. And Employers Health Aff. 2017;32(7):1244–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams MA, Hurley JC, Todd M, Bhuiyan N, Jarrett CL, Tucker WJ, et al. Adaptive goal setting and financial incentives: a 2 × 2 factorial randomized controlled trial to increase adults’ physical activity. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mitchell MS, Orstad SL, Biswas A, Oh PI, Jay M, Pakosh MT, et al. Financial incentives for physical activity in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54(21):1259–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Desai M, Rachet B, Coleman MP, McKee M. Two countries divided by a common language: health systems in the UK and USA. J R Soc Med. 2010;103(7):283–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hafner M, Pollard J, Van Stolk C. Incentives and physical activity an assessment of the association between Vitality’s Active Rewards with Apple Watch benefit and sustained physical activity improvements. 2018. Available from: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2870.html. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.H Wright, H Behrendt, G Tagliaferri. Evaluating a financial incentives scheme intervention to promote healthy eating and physical activity. Available from: https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN10465935. Cited 2024 Feb 20.

- 41.Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, Laupacis A, Gøtzsche PC, Krleža-Jerić K, et al. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):200–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenwood JLJ, Joy EA, Stanford JB. The physical activity vital sign: a primary care tool to guide counseling for obesity. J Phys Act Health. 2010;7(5):571–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.UK Chief Medical Officer. UK chief medical officers’ physical activity guidelines. Department of Health and Social Care. 2019.

- 44.Kang HJ, Wang JCK, Burns SF, Leow MKS. Is Self-Determined Motivation a Useful Agent to Overcome Perceived Exercise Barriers in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus? Front Psychol. 2021;12:627815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Thielen SC, Reusch JEB, Regensteiner JG. A narrative review of exercise participation among adults with prediabetes or type 2 diabetes: barriers and solutions. Front Clin Diab Healthcare. 2023;4:1218692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vilafranca Cartagena M, Tort-Nasarre G, Rubinat AE. Barriers and facilitators for physical activity in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(10):5359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hafner M, Pollard J, Van Stolk C. Incentives and physical activity An assessment of the association between Vitality’s Active Rewards with Apple Watch benefit and sustained physical activity improvements. Rand Health Q. 2018;9(1). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, Welch G, Jacobson AM, Aponte JE, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diab Care. 1995;18(6):754–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen MF, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20(10):1727–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Rossi JS. Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1992;63(1):60–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;19:350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Group the C. CONSORT 2010 Statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Trials. 2010;11(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marwick TH, Hordern MD, Miller T, Chyun DA, Bertoni AG, Blumenthal RS, et al. Exercise training for type 2 diabetes mellitus: impact on cardiovascular risk: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2009;119(25):3244–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morse J. Determining sample size. Qual Health Res. 2000;10:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tariq S, Woodman J. Using mixed methods in health research. J R Soc Med: Short Reports. 2013;4(6):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tappin D, Sinclair L, Kee F, McFadden M, Robinson-Smith L, Mitchell A, et al. Effect of financial voucher incentives provided with UK stop smoking services on the cessation of smoking in pregnant women (CPIT III): pragmatic, multicentre, single blinded, phase 3, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2022;19(379):e071522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tappin D, Bauld L, Purves D, Boyd K, Sinclair L, MacAskill S, et al. Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ : Brit Med J. 2015;27(350):h134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berlin I, Berlin N, Malecot M, Breton M, Jusot F, Goldzahl L. Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021;1(375):e065217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Office of National Statistics. How life has changed in Milton Keynes: Census 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/visualisations/censusareachanges/E06000042/. Cited 2024 Jan 4.

- 62.Office of Health Improvement & Disparities. Fingertips - public health data - local authority health profiles - milton keynes. Available from: https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/health-profiles/data#page/1/gid/1938132695/pat/6/par/E12000008/ati/302/are/E06000042/yrr/3/cid/4/tbm/1/page-options/car-do-0. Cited 2024 Jan 4.

- 63.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Evidence standards framework for digital health technologies. NICE London; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 64.Marcolino MS, Oliveira JAQ, D’Agostino M, Ribeiro AL, Alkmim MBM, Novillo-Ortiz D. The impact of mhealth interventions: systematic review of systematic reviews. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6(1):e23 2018 Jan 17;6(1):e8873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Luoma KA, Leavitt IM, Marrs JC, Nederveld AL, Regensteiner JG, Dunn AL, et al. How can clinical practices pragmatically increase physical activity for patients with type 2 diabetes? A systematic review. Transl Behav Med. 2017;7(4):751–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.