Abstract

Background

Hypertension is a major risk factor for heart disease, heart failure and stroke. Lifestyle changes are recommended as first-line treatment for management of high blood pressure for young adults, when 10-year atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk score is < 10%. If lifestyle changes alone do not control blood pressure, then providers have access to four classes of first-line blood pressure lowering agents to treat hypertension, when other contra-indications are not present.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional, retrospective, secondary analysis performed of the MyHEART trial on study participants at enrollment to determine they were prescribed anti-hypertensive medication. Of those prescribed medications, we aimed to determine the frequency first-line medications including thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics, angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, and calcium channel blockers were prescribed. This analysis categorized participants into four medication status categories: no antihypertensive medication, prescribed only first-line antihypertensives, prescribed only non-first-line antihypertensives, and prescribed a combination of first-line and non-first-line antihypertensives. Participant clinical and sociodemographic factors by medication use were evaluated. Linear regression models were fit to determine the association between antihypertensive medication and blood pressure.

Results

At enrollment, 157/311 (50.5%) participants were not on antihypertensives. Of the 154 on antihypertensives, reported use included monotherapy 97/154 (63.0%), combined therapy 57/154 (37.0%), only first-line antihypertensive 111/154 (72.0%), and only non-first-line antihypertensives 21/154 (13.6%), and combination of first-line and non-first-line antihypertensives 22/154 (14.2%). Antihypertension medication use varied based on age (p < 0.001), sex (p = 0.008), race (p = 0.001), body mass index (BMI) kg/m2 (p = 0.016), anxiety and/or depression (p = 0.048), diabetes (p = 0.007), and sodium intake (p = 0.042). Participants with only first-line medications had lower in-office systolic (-4.66 mmHg, CI -8.31 to -1.02, p = 0.013) and diastolic (-3.51 mmHg, CI -6.30 to -0.71, p = 0.015), and lower ambulatory diastolic (-2.12 mmHg, CI -4.15 to -0.09, p = 0.041) blood pressure than those without antihypertensives.

Conclusions

Among MyHEART study participants, all of which had uncontrolled hypertension, 50.5% were not on an antihypertensive at enrollment. This finding supports the call to improve management of blood pressure earlier in life to potentially contribute to the reduction of long-term cardiovascular disease. Of the participants who were prescribed blood pressure medication, providers prescribed guideline-based antihypertensive therapy the majority of the time, however, this study indicates there may be an opportunity to increase the use of first-line, guideline-based antihypertensives, regardless of age, sex, or type of hypertension to lower long-term cardiovascular risk.

Trial registration

https://www.ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03158051, registered 5-15-2017. IRB approval obtained: IRB # 2017 − 0372.

Keywords: Antihypertensive medication, Uncontrolled hypertension, Young adult

Background

NHANES data from 2017 to 2020 published in the American Heart Association Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 Update reports 28.5% of young adults ages 20–44 years have high blood pressure [1]. Because high blood pressure is a risk factor for a number of adverse health outcomes, the AHA designates blood pressure control as 1 of 8 components to ideal cardiovascular health [2].

Johnson et al. studied hypertension control in young adults treated with antihypertensives, and observed only 34% of over 10,000 young adults had been started on antihypertensive therapy, or achieved hypertension control prior to receiving treatment [3]. There is an association between ambulatory visits and blood pressure control. Gooding and colleagues found 91% of their young adult patient population achieved a blood pressure goal of < 140/<90 mmHg if they received follow-up within one month of an initial visit [4]. Effective blood pressure control can reduce future risk for development of cardiovascular disease including coronary heart disease, heart failure, stroke, chronic kidney disease and tens of thousands of premature deaths each year in the US [5–7]. When lifestyle changes alone do not achieve BP control antihypertensive medications should be initiated.

US guidelines have recommended, without other contraindications present, first-line antihypertensive medications include thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics (TZD), angiotensin converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and calcium channel blockers (CCB) [8, 9]. If control is not reached with one agent, two should be prescribed for Stage 1 HTN, if Stage 2 HTN is present, consideration of two different medication classes is advised [9]. The objective of this study was to evaluate the use of guideline-directed antihypertensive medications and associated levels of blood pressure control among young adult participants with uncontrolled hypertension upon enrollment in the MyHEART study.

Methods

The MyHEART study was a multi-center randomized controlled trial that was conducted at two large Midwestern academic centers, with enrollment from October 2017 through December 2021 (NCT03158051 registered on 5-17-2017). The final sample size for trial enrollment was 316. Study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and results were previously published [10, 11]. In brief, the study population included male and non-pregnant female young adults ranging from 18 to 39 years old at enrollment with uncontrolled hypertension. At the time of study design and protocol implementation, the diagnostic office blood pressure threshold for hypertension was ≥ 140/90 mmHg [12], which was continued throughout the study. Both in-person research visit blood pressures and 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (AMBP) were obtained during the trial. Patients met criteria for uncontrolled hypertension and enrollment to this trial if their mean 24-hour AMBP was a systolic ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥ 80 mmHg and/or the mean awake AMBP was a systolic ≥ 135 mmHg and/or diastolic ≥ 85 mmHg [13, 14]. We did not explicitly exclude participants for secondary causes of hypertension, however it is assumed that the majority had essential hypertension. Specific exclusion criteria included between arm blood pressure difference ≥ 20 mmHg, white coat hypertension (confirmed with 24-hour AMBP), requiring dialysis or seeing a Nephrologist, congestive heart failure, sickle cell anemia, cystic fibrosis, stroke, myocardial infarction, coronary artery revascularization, or prior/planned organ transplant; inability to provide informed consent or read or communicate in English; residence at skilled nursing or correctional facility; prescription of warfarin, novel oral anticoagulant, planned chemotherapy, planned radiation therapy, plan to move out of area in next 6 months; pregnant or plan to become pregnant in next year; illegal drug use other than marijuana in past 30 days; incarceration; and syncope in past 12 months. Following this exclusion criteria, most if not all, of the study participants would have been candidates for first-line antihypertensive agents. This is in line with the ACC/AHA guidelines regarding comorbidities with these medications.

At enrollment, active prescribed antihypertensive medication use was acquired by self-report and confirmed by the electronic health record system (EHR). This analysis was a planned cross-sectional retrospective secondary analysis, categorizing participants into four groups based on their prescribed baseline antihypertensive medications usage: (1) no antihypertensive medications, (2) only guideline-directed first-line antihypertensive medication, (3) only non-first-line medications, and (4) a combination of first- and non-first line antihypertensives. First-line antihypertensive medications were defined as angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), calcium channel blocker (CCB), angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), and thiazide (or thiazide-like) diuretics (TZD). Non-first-line medications were, β-blocker, α/β blocker, central agonist, α-blocker, direct renin inhibitor, vasodilator, and loop diuretics.

Associations of hypertension medication status with participant demographic and health characteristics were determined using Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous variables and categorical variables with a natural ordering (highest level of education and self-perceived health status) and using chi-square tests for nominal categorical variables. If significance was found across the three categories, pairwise comparisons were conducted using chi-square tests or Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon tests and a Bonferroni correction was applied.

Four linear regression models were fit to estimate the relationship between blood pressure and medication status while adjusting for participant demographic and health characteristics. Outcomes for each model were 24- hour AMBP and office systolic and diastolic blood pressures. Estimated differences (mmHg), confidence intervals, and p-values of these adjusted models were reported.

Significance was assessed at the alpha = 0.05 level. All statistical analysis was conducted using R version 4.3.1 (2023-06-16).

Results

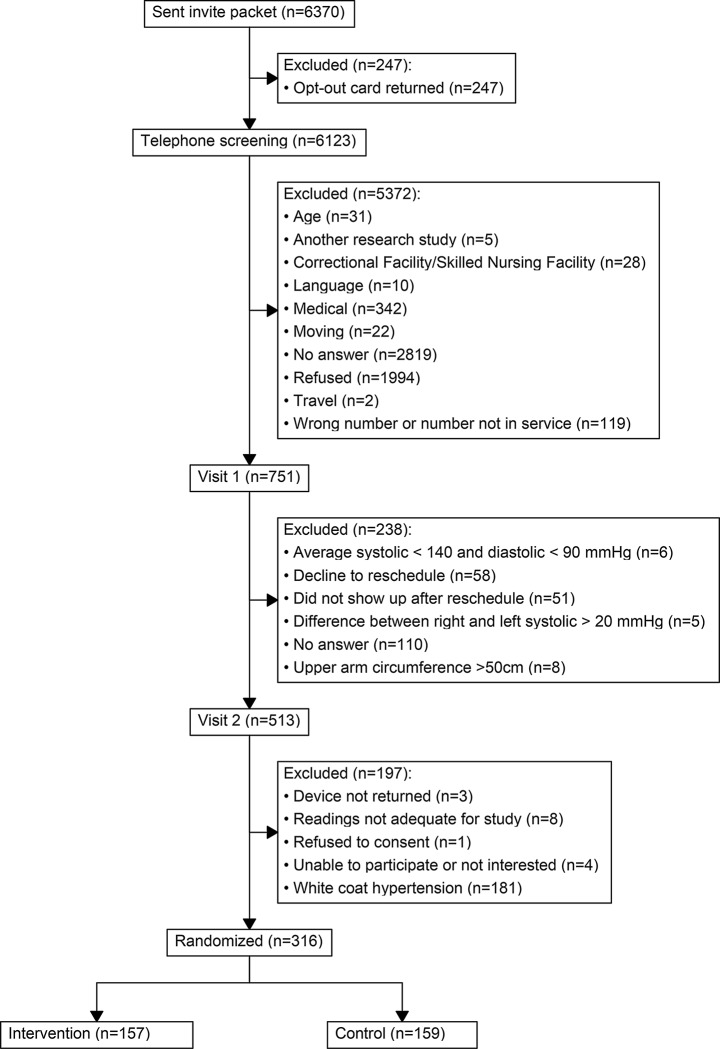

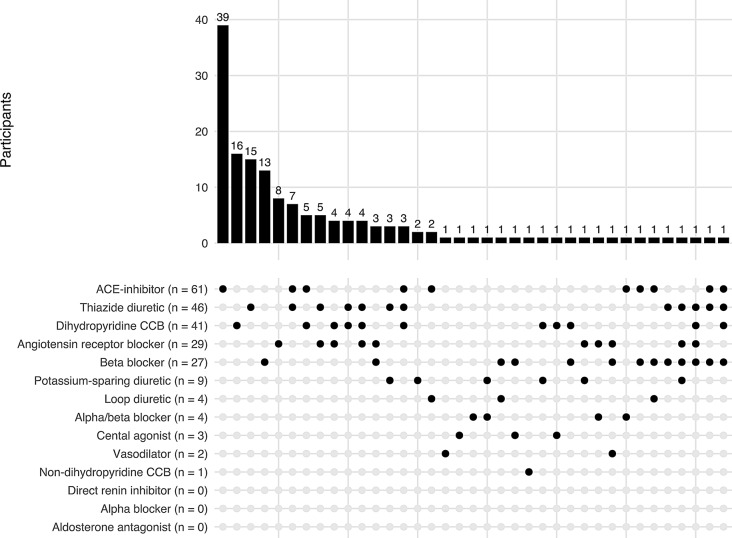

Three hundred and eleven of the 316 enrolled participants were included in this analysis. Baseline demographics and characteristics have been previously published [11]. The five participants excluded from this analysis were due to the participant withdrawing from the study before medication status was collected (Fig. 1). Among study participants, 157/311 (50.5%) were not on any antihypertensive therapy at the time of enrollment, 97/311(31.2%) used monotherapy and 57/311 (18.3%) combined therapy. Figure 2 displays the distribution of all mono- and combined antihypertensive therapy regimens participants were using at the baseline study evaluation. Specifically, of those on antihypertensive therapy (n = 154), 111 (72.0%) were on first-line antihypertensives only, which most commonly was an ACEi followed by TZD, DHP- CCB and ARBs. Twenty-one (13.6%) were on non-first line antihypertensives only, most commonly β-blockers. The remaining 22 (14.2%) were on both first- and non-first line antihypertensives.

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram: MyHEART study

Fig. 2.

Distribution of all antihypertensive medication use among MyHEART study participants at baseline

In our initial analysis we evaluated associations of hypertension medication status with participant demographic and health characteristics. Antihypertension medication use varied based on age (p < 0.001), sex (p = 0.008), race (p = 0.001), body mass index (BMI) kg/m2 (p = 0.016), anxiety and/or depression (p = 0.048), diabetes (p = 0.007), and sodium intake (p = 0.042) (Table 1). The detailed number of participants by sex (Table 2) and race (Table 3) for each medication category along with the counts of specific medications are provided. Some participants were taking multiple medications so the count of individual medications may be larger than the number of participants within that group. Given the significant differences in sex and race in our initial analysis, pairwise tests were conducted and demonstrated a lower proportion of male participants in the only non-first line group (23.8%) compared to those without any medications (58.6%, p = 0.016). A higher proportion of white participants was found in the group without medications (78.3%) compared to those on only first-line (59.5%, p = 0.005) or combination (45.5%, p = 0.0057). No other significant findings were demonstrated for sex and race in any of the pairwise analyses after the Bonferroni adjustment was performed.

Table 1.

Comparison of participants by status of antihypertensive medication use; no antihypertension medications, only first-line medications, and only non-first-line medications, or combination of first-line and non-first-line medications

| Antihypertensive medication status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No meds | Only first-line meds | Only non-first-line meds | Combination meds | p-value | |

| Variable | N = 157 | N = 111 | N = 21 | N = 22 | |

| Age (mean (SD)) | 33.04 (4.97) | 34.90 (3.91) | 32.19 (5.10) | 35.09 (4.70) | 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.008 | ||||

| Male (%) | 92 (58.6) | 61 (55.0) | 5 (23.8) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Female (%) | 65 (41.4) | 50 (45.0) | 16 (76.2) | 14 (63.6) | |

| Race (%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Black | 22 (14.0) | 36 (32.4) | 4 (19.0) | 10 (45.5) | |

| Other | 12 (7.6) | 9 (8.1) | 4 (19.0) | 2 (9.1) | |

| White non-Hispanic | 123 (78.3) | 66 (59.5) | 13 (61.9) | 10 (45.5) | |

| Marital status (%) | 0.144 | ||||

| Single | 42 (26.8) | 42 (37.8) | 8 (38.1) | 12 (54.5) | |

| Married/partnered | 111 (70.7) | 66 (59.5) | 13 (61.9) | 10 (45.5) | |

| Divorced/widower | 4 (2.5) | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Highest level of education (%) | 0.940 | ||||

| I have not finished high school | 6 (3.8) | 6 (5.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (13.6) | |

| I have completed high school | 22 (14.0) | 15 (13.5) | 3 (14.3) | 2 (9.1) | |

| I have not finished college or vocation school | 24 (15.3) | 16 (14.4) | 7 (33.3) | 5 (22.7) | |

| I finished college or vocational school | 73 (46.5) | 53 (47.7) | 7 (33.3) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Some/completed Graduate or Professional School | 32 (20.4) | 21 (18.9) | 4 (19.0) | 8 (36.4) | |

| Number of children at home (mean (SD)) | 0.95 (1.38) | 1.08 (1.43) | 1.24 (1.41) | 0.95 (1.12) | 0.674 |

| Ever been on Medicaid (%) | 30 (19.1) | 27 (24.3) | 5 (23.8) | 5 (22.7) | 0.767 |

| Weight (kg) (mean (SD)) | 101.87 (30.75) | 104.39 (25.08) | 96.52 (26.37) | 110.41 (26.12) | 0.149 |

| Waist circumference (cm) (mean (SD)) | 107.42 (20.65) | 111.21 (18.45) | 107.67 (20.86) | 116.45 (17.93) | 0.091 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (mean (SD)) | 33.61 (9.37) | 35.15 (8.41) | 34.32 (8.16) | 37.42 (6.81) | 0.016 |

| Office systolic BP (mmHg) (mean (SD)) | 139.15 (13.99) | 137.41 (13.98) | 136.16 (16.20) | 138.76 (16.86) | 0.579 |

| Office diastolic BP (mmHg) (mean (SD)) | 91.42 (11.35) | 90.57 (11.49) | 93.16 (12.43) | 94.14 (9.79) | 0.230 |

| Ambulatory systolic BP (mmHg) (mean (SD)) | 133.10 (12.44) | 132.79 (12.42) | 129.86 (10.13) | 134.86 (9.37) | 0.368 |

| Ambulatory diastolic BP (mmHg) (mean (SD)) | 87.08 (8.45) | 86.28 (7.89) | 87.86 (6.46) | 87.05 (6.26) | 0.554 |

| e-cigarette/vaping use in past 6 months (%) | 15 (9.6) | 9 (8.1) | 2 (9.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.504 |

| Cigarette tobacco status (%) | 0.929 | ||||

| I currently smoke cigarettes | 19 (12.1) | 15 (13.5) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (18.2) | |

| I have never smoked cigarettes | 105 (66.9) | 77 (69.4) | 16 (76.2) | 14 (63.6) | |

| I used to smoke cigarettes | 33 (21.0) | 19 (17.1) | 3 (14.3) | 4 (18.2) | |

| Alcohol beverages/week (mean (SD)) | 5.52 (6.22) | 5.51 (6.26) | 3.86 (4.29) | 4.23 (6.55) | 0.376 |

| Anxiety and/or depression (%) | 87 (55.4) | 46 (41.4) | 14 (66.7) | 13 (59.1) | 0.048 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 38 (24.2) | 28 (25.2) | 1 (4.8) | 6 (27.3) | 0.212 |

| Chronic kidney disease (%) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.703 |

| Diabetes (%) | 3 (1.9) | 9 (8.1) | 2 (9.5) | 4 (18.2) | 0.007 |

| Other chronic comorbidity (%) | 57 (36.3) | 46 (41.4) | 7 (33.3) | 11 (50.0) | 0.540 |

| Family history of heart disease or stroke (%) | 48 (30.6) | 49 (44.1) | 6 (28.6) | 10 (45.5) | 0.089 |

| Self-perceived health status (%) | 0.133 | ||||

| Excellent | 6 (3.8) | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Very good or good | 79 (50.3) | 59 (53.2) | 6 (28.6) | 9 (42.9) | |

| Fair | 52 (33.1) | 40 (36.0) | 13 (61.9) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Poor or no response | 20 (12.7) | 11 (9.9) | 2 (9.5) | 6 (28.6) | |

| Financial status: inadequate income (%) | 130 (82.8) | 81 (73.0) | 17 (81.0) | 15 (68.2) | 0.164 |

| Godin-Shephard Physical Activity, Insufficiently active (%) | 80 (51.0) | 56 (50.5) | 14 (66.7) | 12 (54.5) | 0.564 |

| Sodium intake (mg/day) (mean (SD)) | 3897.25 (2067.46) | 3384.44 (1436.45) | 3002.62 (973.85) | 3083.73 (1512.78) | 0.042 |

Comparisons of nominal categorical variables were made using chi-square tests; continuous variables and categorical variables with a natural ordering (highest level of education and self-perceived health status) were tested using Kruskal-Wallis tests. Bold values are significant at the alpha = 0.05 level

Percent is calculated using the denominator at the top of each column

P-values show overall associations between medication category and each characteristic

Table 2.

Number of participants by sex for each medication category along with the counts of specific medications. Some participants were taking multiple medications so the count of individual medications may be larger than the number of participants within that group

| No meds | Only first-line | Only non-first-line | Combination | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | N = 157 | N = 111 | N = 21 | N = 22 |

| Female, (N,%) | 65 (41.4) | 50 (45.0) | N = 16 (80.0) | N = 14 (63.6) |

| ACE-inhibitor (17), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (10), Dihydropyridine CCB (21), Thiazide diuretic (18) | Alpha/beta blocker (2), Beta Blocker (10), Central agonist (2), Loop diuretic (1), Potassium-sparing diuretic (3), Vasodilator (1) | ACE-inhibitor (3), Alpha/beta blocker (1), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (5), Beta Blocker (8), Dihydropyridine CCB (3), Loop diuretic (1), Potassium-sparing diuretic (5), Thiazide diuretic (5), Vasodilator (1) | ||

| Male, (N,%) | 92 (58.5) | 61 (55.0) | N = 5 (24.0) | N = 5 (22.7) |

| ACE-inhibitor (37), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (11), Dihydropyridine CCB (15), Non-dihydropyridine CCB (1), Thiazide diuretic (20) | Beta Blocker (5) | ACE-inhibitor (4), Alpha/beta blocker (1), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (3), Beta Blocker (4), Central agonist (1), Dihydropyridine CCB (2), Loop diuretic (2), Potassium-sparing diuretic (1), Thiazide diuretic (3) |

Table 3.

Number of participants by race for each medication category along with the counts of specific medications. Some participants were taking multiple medications so the count of individual medications may be larger than the number of participants within that group

| No meds | Only first-line | Only non-first-line | Combination | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | N = 157 | N = 111 | N = 21 | N = 22 |

| Black | N = 22 | N = 36 | N = 4 | N = 10 |

| ACE-inhibitor (14), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (9), Dihydropyridine CCB (22), Thiazide diuretic (17) | Alpha/beta blocker (1), Beta Blocker (1), Potassium-sparing diuretic (1), Vasodilator (1) | ACE-inhibitor (3), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (3), Beta Blocker (7), Dihydropyridine CCB (4), Loop diuretic (2), Potassium-sparing diuretic (3), Thiazide diuretic (5), Vasodilator (1) | ||

| Other | N = 12 | N = 9 | N = 4 | N = 2 |

| ACE-inhibitor (5), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (1), Dihydropyridine CCB (2), Non-dihydropyridine CCB (1), Thiazide diuretic (3) | Beta Blocker (4), Central agonist (1) | Alpha/beta blocker (1), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (2), Beta Blocker (1) | ||

| White non-Hispanic | N = 123 | N = 66 | N = 13 | N = 10 |

| ACE-inhibitor (35), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (11), Dihydropyridine CCB (12), Thiazide diuretic (18) | Alpha/beta blocker (1), Beta Blocker (10), Central agonist (1), Loop diuretic (1), Potassium-sparing diuretic (2) | ACE-inhibitor (4), Alpha/beta blocker (1), Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (3), Beta Blocker (4), Central agonist (1), Dihydropyridine CCB (1), Loop diuretic (1), Potassium-sparing diuretic (3), Thiazide diuretic (3) |

More specifically, we report the prespecified categorical assignment of prescribed antihypertensive use in comparison to the reference of no prescribed antihypertensive use. Participants not prescribed antihypertensives were younger (p = 0.001), had lower BMI (p = 0.027), varied by race/ethnicity (p = 0.001), had higher rates of anxiety or depression (p = 0.024), and had lower rates of diabetes (p = 0.016) compared to participants on only first-line antihypertensives. Participants not prescribed antihypertensives had lower rates of diabetes (p = 0.047) and higher sodium intake (p = 0.046) compared to participants on only non-first-line antihypertensives. Participants not prescribed antihypertensives were younger (p = 0.020), had lower BMI (p = 0.006), varied by race/ethnicity (p = 0.001), had lower rates of diabetes (p < 0.001), and higher sodium intake (p = 0.046) compared to participants on combination antihypertensives.

Participants with only non-first-line antihypertensives were younger than those on only first-line (p = 0.019) or combination medications (p = 0.037) and had higher rates of anxiety (p = 0.033) than those on only first-line.

Blood pressure model results by medication use

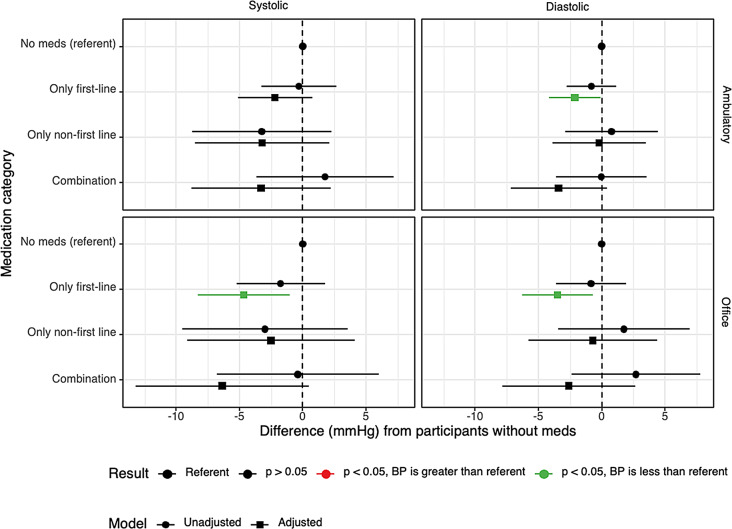

No significant differences were found in office or 24-hour AMBP in unadjusted models (Fig. 3). After adjusting for participant characteristics, participants with only first-line medications had lower in-office systolic (-4.66 mmHg, CI -8.31 to -1.02, p = 0.013) and diastolic (-3.51 mmHg, CI -6.30 to -0.71, p = 0.015), and lower 24-hour ambulatory diastolic (-2.12 mmHg, CI -4.15 to -0.09, p = 0.041) blood pressure than those without medications. Although the estimated ambulatory systolic blood pressure was lower in participants with only first-line medications than those without medications, this result was not significant (-2.19mmHg, CI -5.12 to 0.74, p = 0.144). Additionally, participants with only first line vs. only non-first line in office or 24-hour AMBP comparisons were not significant, p > 0.05.

Fig. 3.

Unadjusted and adjusted results summary of blood pressure by medication use

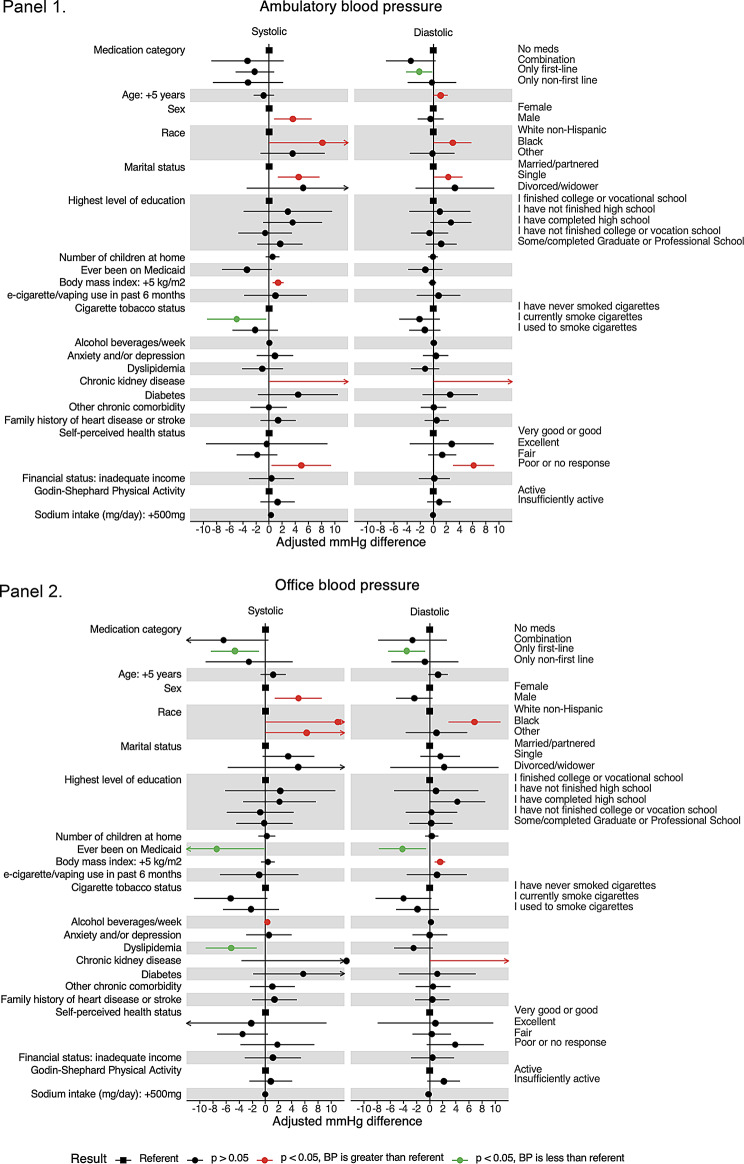

The remaining adjusted model covariates are shown in Fig. 4 for ambulatory (Panel 1) and office (Panel 2) blood pressures.

Fig. 4.

Adjusted linear models for ambulatory (panel 1) and office (panel 2) blood pressure results. Unadjusted and adjusted coefficients of medication use for each blood pressure outcome.Panel 1 Adjusted linear model results with ambulatory blood pressure as outcomes. Weight and waist circumference were excluded from the adjusted model due to collinearity with BMI. Green and red dots are significant at the alpha = 0.05 level. Panel 2 Adjusted linear model results with office blood pressure as outcomes. Weight and waist circumference were excluded from the adjusted model due to collinearity with BMI. Green and red dots are significant at the alpha = 0.05 level

Discussion

Overall, 50.5% of the young adults with uncontrolled hypertension at the time of enrollment in the MyHEART study were not prescribed antihypertensive medication. Of the participants who were prescribed blood pressure medication, 86.4% of the time, guideline recommended medications were prescribed. Non-guideline-directed antihypertensive medications were prescribed to 13.6% of participants. This raises concerns about delays in antihypertensive medication initiation among young adults with uncontrolled hypertension. Additionally, all study participants were uncontrolled on the antihypertensive regimen they were prescribed. This study was unable to assess non-adherence to antihypertensive treatment as an indication for uncontrolled hypertension. Additionally, our analysis demonstrated significant sociodemographic and clinical characteristics that predicted use of guideline-directed antihypertensive therapy. Participants who were older, Black, had diabetes mellitus, and lower self-reported sodium intake were more likely to be prescribed any antihypertensive medication versus no antihypertensive medication. Participants with higher diastolic blood pressure were more likely to be prescribed only non-first-line antihypertensive medications instead of at least one first-line medication. The remainder of clinical and sociodemographic factors available for this analysis were not significantly different by status of antihypertensive use.

The ACC/AHA 2017 guidelines support treatment of stage 2 hypertension regardless of 10-year ASCVD cardiovascular risk [9]. All participants had stage 2 hypertension at enrollment, and despite the ACC/AHA recommendations, only 49.5% of participants who met criteria for chronic hypertension treatment at enrollment into this study were using pharmacotherapy. Notably, 63% of participants who were on pharmacotherapy, were prescribed just one agent. Despite clear recommendations for initiating therapy with 2 agents of different classes in individuals with stage 2 hypertension, monotherapy remains the dominant treatment modality in this population. Thus, our focus in this discussion is solely on the initial choice of medication classes rather than on the use of mono- versus combo therapy.

The MyHEART data shows underutilization of antihypertensive therapy when indicated among young adults with uncontrolled hypertension. This may be a reflection of lifestyle modifications commonly being the initial treatment for hypertension rather than initiation of antihypertensive medications in young adults [9]. A meta-analysis conducted by Long and colleagues found isolated diastolic hypertension to be significantly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality, and stroke, especially when diagnosed in young adults and Asian patients [15]. Diastolic blood pressure has also been linked to increased risks of cardiovascular disease before 45 years of age and coronary heart disease in men [16]. The specific recommendations for antihypertensive medication treatment are the same for isolated systolic or combined systolic/diastolic hypertension. Treatment directed at diastolic hypertension will inadvertently also lower systolic values. This study and the volume of available literature is limited in the ability to determine why we identified more participants using non-first line antihypertensive agents with isolated diastolic hypertension. It has been reported in the literature that isolated diastolic hypertension is underdiagnosed [17]. This is an area of needed future research and an opportunity to recommend treatment of this type of hypertension with the same first-line agents to optimize the long-term cardiovascular event risk reduction [9, 15, 16].

The guidelines recommend that monotherapy in patients of Black race include CCBs and TZDs over ACEi/ARBs. Thus, this will have an impact on the racial interpretations. However, our findings do fit with the current shift away from race-based prescribing of medications [18].

. The number of participants in this study using only non-first-line antihypertension medications were small; however, it is worth noting there was a higher number of women using non-first line medications. This may be explained by the fact that young women of child birthing age are often prescribed recommended antihypertensive agents that are deemed safe in pregnancy: labetalol, nifedipine, or methyldopa [9, 19, 20]. Therefore, women may be more likely prescribed non-guideline based first-line therapy for non-pregnant adults, specifically β-blockers. Compared to first-line antihypertensive agents in the treatment of primary chronic hypertension, β-blockers have been associated with less protection against stroke risk and all-cause mortality and have been associated with an increased risk of impaired glucose tolerance and development of diabetes mellitus [21–28]. Limited data has suggested women respond more favorably to diuretics, ACE inhibitors and β-blockers, however, more research is needed to understand sex differences in response to treatment [29]. It is well understood that women should discontinue the use of ACEis and ARBs prior to becoming pregnant [6]. However, our data suggests there may be an opportunity to increase the use of guideline based first-line agents in women not planning to become pregnant or transitioning back to these agents outside the immediate postpartum period and more selectively use β-blockers in the preconception/pregnancy periods. Lastly, the study exclusion criteria excluded the majority of patients with secondary causes of hypertension; however, it is possible that people prescribed non-first line antihypertensives may have had a secondary cause of hypertension (e.g.; primary aldosteronism) that we were unaware of and may have influenced the prescribed treatment choice.

Limitations

This was a planned analysis of the MyHEART Trial; however, the authors acknowledge it was a cross-sectional evaluation of enrollment data. Enrollment inclusion criteria specified inclusion of patients with a confirmed medical diagnosis of elevated blood pressure or hypertension and was confirmed to have uncontrolled hypertension at the time of enrollment. Study exclusion criteria eliminated the majority of people with secondary hypertension, however, cannot rule out that a minority could have had an undiagnosed secondary hypertension. A strength was that each participant’s medication prescription was confirmed by each participant and verified in the EHR. Study staff did not evaluate the decision as to why antihypertensive medications were or were not prescribed prior to study enrollment. For those participants who were prescribed antihypertensives, this study did not collect details on medication adherence and/or why the participant’s blood pressure was uncontrolled on the regimen at enrollment. An additional limitation of this analysis is the small sample size hinders the ability to assess true practice differences by sex and race. Additionally, it is possible this study was underpowered to detect significant differences among other clinical or sociodemographic variables and is an opportunity for future research. Future research should collect more of these details to shed light on provider and patient practices that may also contribute to suboptimal control of hypertension among adults.

Conclusion

Globally, lack of hypertension control is a public health problem and is more commonly underdiagnosed and uncontrolled in young adults [30, 31]. All study participants in this study had uncontrolled hypertension upon study enrollment and only half were on antihypertensive therapy at the time of enrollment. Of those taking antihypertensive medication, key demographic and clinical variables were identified that influenced the use of guideline-directed antihypertensive medication. An additional emphasis should be placed on initiating pharmacotherapy in young adults, especially if they have stage two hypertension, to reduce the long-term damage that high blood pressure exerts on blood vessels over more life years. There is a call to improve management of blood pressure earlier in life [32]. In addition to pharmacotherapy, increased healthcare contact and BP monitoring, including home BP monitoring, can increase hypertension detection, more timely initiation of antihypertensive therapy and adjustments of medications to achieve adequate BP control [31, 33]. These findings may help to address potential areas of future investigation as well as more effective treatment strategies and interventions.

Providers are prescribing guideline-based antihypertensive therapy the majority of the time, however, there may be an opportunity to increase the use of first-line, guideline-based antihypertensives, regardless of age, sex, or type of hypertension to lower long-term cardiovascular risk.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the participants who participated in the MyHEART Trial. We also thank the research coordinators who made the data collection possible for this study; Jamie LaMantia, Laura Zeller, Steven Jarrett, Jenni Yefchak, Matthew Swenson, Narmin Muktarova, Lexy Richardson, Erin Barwick, Abby Tran, Mary Briggs-Sedlachek, and Elizabeth Collins.

Abbreviations

- AMBP

Ambulatory Blood Pressure Monitoring

- ACEi

Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

- CCB

Calcium channel blocker

- ARB

Angiotensin receptor blocker

- TZD

Thiazide diuretic

Author contributions

M.R.KS made contributions to manuscript writing. K.K.H. made contributions to the study design, interpretation of data, manuscript writing and revisions. J.Z. and K.K provided data analysis and created tables and figures. H.M.J., P.M., D.R.L., J.P., A.H., A.J., revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and provided expert consultation.

Funding

This work was funded in part by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01HL132148). The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript. Please contact Megan Knutson Sinaise, mknutson2@wisc.edu with any data related inqueries.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Participants gave their voluntary, informed consent to participate in the MyHEART Trial. They were reimbursed up to $150 for their participation. This study followed the Declaration of Helsinki principles and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2023 update: a Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation Feb. 2023;21(8):e93–621. 10.1161/cir.0000000000001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association AH. Life’s Essential 8™. Accessed 9/20/2022, https://www.heart.org/en/healthy-living/healthy-lifestyle/lifes-essential-8

- 3.Johnson HM, Thorpe CT, Bartels CM, et al. Antihypertensive medication initiation among young adults with regular primary care use. J Gen Intern Med. May 2014;29(5):723–31. 10.1007/s11606-014-2790-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gooding HC, Brown CA, Wisk LE. Investing in our future: the importance of ambulatory visits to achieving blood pressure control in young adults. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) Dec. 2017;19(12):1298–300. 10.1111/jch.13100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farley TA, Dalal MA, Mostashari F, Frieden TR. Deaths preventable in the U.S. by improvements in use of clinical preventive services. Am J Prev Med Jun. 2010;38(6):600–9. 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabi DM, McBrien KA, Sapir-Pichhadze R, et al. Hypertension Canada’s 2020 Comprehensive guidelines for the Prevention, diagnosis, Risk Assessment, and treatment of hypertension in adults and children. Can J Cardiol May. 2020;36(5):596–624. 10.1016/j.cjca.2020.02.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carey RM, Moran AE, Whelton PK. Treatment of hypertension: a review. Jama Nov. 2022;8(18):1849–61. 10.1001/jama.2022.19590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suchard MA, Schuemie MJ, Krumholz HM, et al. Comprehensive comparative effectiveness and safety of first-line antihypertensive drug classes: a systematic, multinational, large-scale analysis. Lancet Nov. 2019;16(10211):1816–26. 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)32317-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention. Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. May 2018;15(19):e127–248. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006http://ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Johnson HM, Sullivan-Vedder L, Kim K, et al. Rationale and study design of the MyHEART study: a young adult hypertension self-management randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials Mar. 2019;78:88–100. 10.1016/j.cct.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoppe KK, Smith M, Birstler J, et al. Effect of a Telephone Health Coaching Intervention on Hypertension Control in Young adults: the MyHEART Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open Feb. 2023;1(2):e2255618. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.55618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). Jama. Feb 5. 2014;311(5):507 – 20. 10.1001/jama.2013.284427 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Pickering TG, Shimbo D, Haas D. Ambulatory blood-pressure monitoring. N Engl J Med Jun. 2006;1(22):2368–74. https://doi.org/10.101056/NEJMra060433/354/22/2368[pii].. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement: High Blood Pressure in Adults: Screening. Accessed March 23. 2017. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/high-blood-pressure-in-adults-screening

- 15.Huang M, Long L, Tan L, et al. Isolated diastolic hypertension and risk of Cardiovascular events: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies with 489,814 participants. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:810105. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.810105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bulpitt CJ. Is systolic pressure more important than diastolic pressure? J Hum Hypertens Oct. 1990;4(5):471–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conell C, Flint AC, Ren X, et al. Underdiagnosis of isolated systolic and isolated diastolic hypertension. Am J Cardiol Feb. 2021;15:141:56–61. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2020.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Flack JM, Bitner S, Buhnerkempe M. Evolving the role of Black Race in Hypertension therapeutics. Am J Hypertens. 2024;37(10):739–44. 10.1093/ajh/hpae093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.ACOG Practice Bulletin No. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Jan. 2019;203(1):e26–50. 10.1097/aog.0000000000003020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guidelines. Hypertension in pregnancy: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Copyright © NICE 2019.; 2019.

- 21.Wiysonge CS, Bradley HA, Volmink J, Mayosi BM, Opie LH. Beta-blockers for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev Jan. 2017;20(1):Cd002003. 10.1002/14651858.CD002003.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomopoulos C, Bazoukis G, Tsioufis C, Mancia G. Beta-blockers in hypertension: overview and meta-analysis of randomized outcome trials. J Hypertens Sep. 2020;38(9):1669–81. 10.1097/hjh.0000000000002523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lindholm LH, Carlberg B, Samuelsson O. Should beta blockers remain first choice in the treatment of primary hypertension? A meta-analysis. Lancet Oct 29-Nov. 2005;4(9496):1545–53. 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)67573-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta A, Mackay J, Whitehouse A, et al. Long-term mortality after blood pressure-lowering and lipid-lowering treatment in patients with hypertension in the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac outcomes Trial (ASCOT) Legacy study: 16-year follow-up results of a randomised factorial trial. Lancet Sep. 2018;29(10153):1127–37. 10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31776-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlberg B, Samuelsson O, Lindholm LH. Atenolol in hypertension: is it a wise choice? Lancet. Nov 6–12. 2004;364(9446):1684-9. 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)17355-8 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Messerli FH, Bangalore S, Julius S. Risk/benefit assessment of beta-blockers and diuretics precludes their use for first-line therapy in hypertension. Circulation May. 2008;20(20):2706–15. 10.1161/circulationaha.107.695007. discussion 2715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bakris GL, Fonseca V, Katholi RE, et al. Metabolic effects of carvedilol vs metoprolol in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Jama Nov. 2004;10(18):2227–36. 10.1001/jama.292.18.2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sarafidis PA, Bakris GL. Antihypertensive treatment with beta-blockers and the spectrum of glycaemic control. Qjm Jul. 2006;99(7):431–6. 10.1093/qjmed/hcl059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wenger NK, Arnold A, Bairey Merz CN, et al. Hypertension across a woman’s life cycle. J Am Coll Cardiol. Apr 2018;24(16):1797–813. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lu J, Lu Y, Wang X, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in China: data from 1·7 million adults in a population-based screening study (China PEACE million persons project). Lancet Dec. 2017;9(10112):2549–58. 10.1016/s0140-6736(17)32478-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Worldwide trends in. Hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: a pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet Sep. 2021;11(10304):957–80. 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)01330-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vasan RS. High blood pressure in Young Adulthood and risk of premature Cardiovascular Disease: calibrating treatment benefits to potential harm. Jama Nov. 2018;6(17):1760–3. 10.1001/jama.2018.16068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wall HK, Streeter TE, Wright JS. An opportunity to Better Address Hypertension in women: self-measured blood pressure monitoring. J Womens Health (Larchmt). Sep 2022;26. 10.1089/jwh.2022.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention. Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. May 2018;15(19):e127–248. 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006http://ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC. [DOI] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

Data is provided within the manuscript. Please contact Megan Knutson Sinaise, mknutson2@wisc.edu with any data related inqueries.