Abstract

Online resources play a vital role in patient education, yet the readability of alopecia areata-related materials remained understudied. A thorough analysis of online alopecia areata-related materials across 5 languages was conducted using Google search. Search terms “alopecia areata” and “alopecia areata treatment” were translated and queried, generating search result lists. The first 50 articles from each list were evaluated for suitability. The materials were categorized into 2 main groups: those focusing on alopecia areata itself and those addressing its treatment. Treatment materials were further divided into subgroups, including Janus kinase inhibitors and other treatment options. Readability was evaluated using the Lix score. The analysis included 251 articles in English, German, French, Italian, and Spanish. The overall mean Lix score was 52 ± 8, which classified them as very hard to comprehend. Articles on alopecia areata treatment had a mean Lix score of 55 ± 8, which was significantly higher (p < 0.001) than those on alopecia areata itself, 50 ± 8. alopecia areata-treatment articles dedicated to JAK inhibitors had an average Lix score of 57 ± 10 and it was significantly higher (p = 0.043) than those on other treatment, 53 ± 6. Online resources on alopecia areata and its treatments remained challenging to comprehend, particularly regarding JAK inhibitors. Improving clarity in patient education materials is crucial for informed decision-making and therapeutic relationships.

Key words: readability, alopecia areata, JAK inhibitors

SIGNIFICANCE

This study highlights a critical issue for patients seeking information on alopecia areata and its treatments: the readability of online materials. Articles on alopecia areata treatments are generally harder to understand than those concerning alopecia areata itself, posing challenges for patients. This complexity is partly due to the evolving nature of alopecia areata treatments, with experts themselves grappling with complete understanding. The introduction of new therapies, such as JAK inhibitors, emphasizes the need for clear, accessible patient education to ensure informed decision-making and effective doctor–patient communication. Improving the readability of alopecia areata-related materials is essential to empower patients and support their treatment journey.

Alopecia areata (AA) is a condition in which the immune system attacks hair follicles, causing hair loss on the scalp and other areas of the body (1). In most cases, this condition is characterized by the development of circular or patchy bald patches that do not result in scarring (1). Although hair regrowth is common in the early stages of the disease, it is rare for patients with extensive and chronic hair loss (1). Spontaneous hair regrowth differs between the AA subgroups (2–4). Patchy AA is the most common and mildest form of AA (2–4). It was demonstrated that 80–90% of patients who suffer from patchy AA experience spontaneous regrowth within a year, often without any treatment (2–4). Alopecia totalis (AT) and alopecia universalis (AU) are more severe forms of AA (2–4). Spontaneous hair regrowth is observed in 10–25% of AT patients and in fewer than 10% of AU patients (2–4). Patchy AA has a better prognosis for regrowth (2–4). However, factors like the extent of hair loss, duration of the disease, and family history can influence recovery rates (2–4). The condition may also manifest in the nails, leading to brittleness or pitting (1). AA is relatively common with an approximate global prevalence of 0.1% and 2% lifetime incidence (5). The exact cause of AA remains unknown, but it is theorized to be connected to external factors, genetics, and dysfunction of the immune system (1). Patients could experience depression, anxiety, social difficulties, and low self-esteem, all of which could damage their quality of life (1). Additionally, the affected areas are at a higher risk of exposure to ultraviolet radiation due to the lack of hair protection, potentially causing sunburn or sunspots on the scalp (1). Therefore, AA can have adverse effects on how a person looks, feels, and is perceived by others, emphasizing the critical role of early diagnosis and treatment.

Until 2022, physicians primarily utilized off-label medications for AA due to the lack of approved systemic treatments by prominent regulatory bodies like the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) or European Medicines Agency (EMA) (6, 7). There were a variety of guidelines and a consensus among experts on the topic, but a universally accepted approach to managing AA was not established (6, 8, 9). The EMA and FDA recently approved baricitinib and ritlecitinib, an oral selective Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor for the treatment of AA (10–13). Recent real-world studies demonstrated that baricitinib is effective in treating patients with AA, particularly for the patchy phenotype (14–16). Baricitinib also demonstrated a favourable safety profile, with minimal adverse events reported (14–16). Although targeting the JAK signalling pathway holds great potential for restoring hair regrowth in AA, nowadays these drugs remain in many countries unavailable for patients in routine clinical practice (2, 6).

All of these motivate AA patients to search on Internet websites for information on their condition, clinical symptoms, and available treatment, which gives the opportunity to obtain disease-specific information privately and quickly. The Internet is increasingly used for making personal health decisions, as evidenced by survey results showing that 70% of American adult Internet users consider it their primary diagnostic resource (18–20). This positions personal health as the third most popular online activity, emphasizing the importance of reliable sources (17–19).

To date, there has been no study that has assessed the readability of the AA-related online materials. The main aim of this study was to assess comprehensiveness of online AA-related materials across multiple languages. The secondary aim was to compare the readability of articles dedicated to AA treatment and AA in general. How the readability of articles dedicated to JAK inhibitors differed from other forms of treatment was also examined. Finally, correlations between readability and abundance of articles were investigated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search method

In this investigation, the terms “alopecia areata” and “alopecia areata treatment” were utilized. Each was translated into the 5 most used languages in the European Union (EU). Google Translate and Wikipedia were employed to produce translations for these terms. Google Translate was employed as an alternative when the desired language did not have the searched term in a Wikipedia article. Through the years, Google has gained over 90% of market share across all devices and remains the most popular Internet search engine (20). As a result, other engines were not included in the study. “Sponsored” articles are displayed by Google at the top of the search list. These articles were not included in the analysis. To uphold the validity of the findings, the private mode of the web browser was utilized and the language for Google Services was adjusted to match the searched term (21). To ensure that the generated list of results was only in the desired language, a “Results Language Filter” was applied for each new session (21). This methodology was in accordance with Google guidelines on searching for information in different languages (21). Google search results could be influenced by the time and location. All searches in this study were conducted in Wroclaw, Poland between 4 and 12 March 2024. The authors evaluated every included article for its primary content focus. Any article that primarily addressed the treatment of alopecia areata was classified as AA treatment. Similarly, any articles that focused primarily on alopecia areata in general were categorized as AA. Every article on alopecia areata treatment was assessed based on its content. In cases where the focus was on JAK inhibitors, they were specifically classified as JAK inhibitors. If not, they were categorized as other treatment. If the search results were identical for both search terms, duplicated results were excluded from the analysis. The first 50 search results for each term in each language were examined. Previous research established that most internet users do not read past the initial 50 hits (22, 23). Articles concerning AA and its treatment, designed to educate patients and available to the public at no cost, were incorporated in the analysis. The analysis did not consider results that were not in the language of the searched term, or those that were restricted by a password or paywall. Furthermore, the research did not involve any scientific articles, videos, personal blogs, online forums, or advertisements. Any website that mainly featured promotional content for a specific drug, medical centre, or physician and did not prioritize patient education was considered an advertisement (23). Articles related to veterinary medicine, issued by the regulatory body, and dedicated to physicians were ruled out from the analysis. Five of the most prevalent EU languages by the number of speakers as a percentage of EU population were included: English, German, French, Italian, and Spanish (24).

Readability assessment

All included materials were evaluated using the Lix readability measure, a verified instrument (25, 26). It assesses text complexity by measuring 2 factors: average sentence length and the percentage of long words (those with more than 6 characters) (26). It is the product of dividing the number of words by the number of sentences and adding the percentage of long words (26). A higher Lix score indicates a more difficult text (26). In multiple languages, including English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish, Lix was found to be a trustworthy measure, unlike other readability measures such as the Gunning Fogg Index (23, 25, 26). After being transferred to Microsoft Word, the text underwent a thorough review, eliminating any unnecessary components such as affiliations, hyperlinks, figures, legends, disclaimers, ads, author information, and copyright notices. The feature “Save as Plain Text” was employed. The appropriate language was selected in Microsoft Word to review and correct any spelling or grammar issues. Each article was stored as a separate file and then transferred to the Lix calculator through https://haubergs.com/rix. The data that were recorded consisted of the Lix score, total amount of sentences, words, and average words per sentence. To interpret the Lix score, the Anderson scale was utilized (26). Texts scoring lower than 20 were identified as very easy, those below 30 were labelled as easy to understand, and texts scoring below 40 were deemed a little hard to comprehend (26). Any score below 50 was considered hard, and below 60 was classified as very hard to comprehend (26).

Statistical analysis

The Shapiro–Wilk test was utilized to determine the normality of the data. Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test were employed to assess the disparities between articles on AA and AA treatment, and those within AA treatment on JAK inhibitors and other treatment. The study utilized ANOVA or the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare differences among labels and languages. Univariate linear regression analysis was employed to examine the correlation between the mean Lix score of the articles analysed and the number of hits. A p-value equal to or less than 0.05 was statistically significant. Microsoft Word and Excel (version 16.59, Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA, USA) were employed to gather the data. Version 16.59 of JASP (https://jasp-stats.org/), developed by the JASP Team at the University of Amsterdam, was used to calculate the statistics.

RESULTS

Prevalence

In overall, 251 articles in English (61, 24%), German (49, 20%), French (49, 20 %), Italian (43, 17%), and Spanish (47, 19%) were included. There were more articles dedicated to AA in general (154, 61%) than focused on treatment (97, 39%). Articles dedicated to AA were more prevalent than those on AA treatment across all included languages. Detailed prevalence results and number of hits are presented in Table I.

Table I.

Number of included online articles and hits

| Language | Search term | Total # hits | Included websites n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| English | alopecia areata | 23,700,000 | 39 (78) |

| alopecia areata treatment | 9810000 | 22 (44) | |

| German | alopecia areata | 20200000 | 29 (58) |

| alopecia areata behandlung | 53800 | 22 (44) | |

| Italian | alopecia areata | 18500000 | 22 (44) |

| alopecia areata cura | 207000 | 21 (42) | |

| French | pelade | 461000 | 30 (60) |

| pelade traitement | 92200 | 19 (38) | |

| Spanish | alopecia areata | 19300000 | 34 (68) |

| alopecia areata tratamiento | 581000 | 13 (26) |

#number of; %: percent of articles included from top 50 articles in the results list.

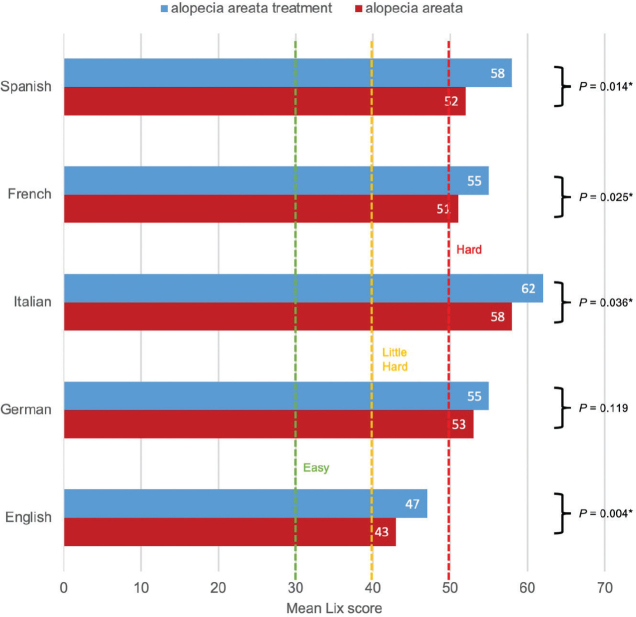

Among the articles that discussed treatment options, those pertaining to JAK inhibitors (48, 49%) were slightly less common compared with those covering alternative forms of treatment (49, 51%). JAK inhibitors were more prevalent than other treatment in English (12; 54% vs 10; 46%), French (10; 53% vs 9; 47%), and Spanish (7; 54% vs 6; 46%). The opposite was observed for articles in German (10; 45% vs 12; 55%) and Italian (9; 43% vs 12; 57%). These data are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of articles dedicated to JAK inhibitors. Percentage share of articles dedicated to JAK inhibitors and other treatment forms within all included articles dedicated to treatment.

Readability

Overall mean values for analysed articles were 52 ± 8 for Lix score, 55 ± 45 for number of sentences, 950 ± 711 for number of words, and 18 ± 6 for number of words per sentence. This classified the included articles as very hard to comprehend. In general, articles in English had a mean Lix score of 44 ± 8, were the most comprehensible, and were classified as hard to comprehend. Articles in French (53 ± 6), Spanish (53 ± 8), German (54 ± 5), and Italian (60 ± 6) were classified as very hard to comprehend. Differences in mean Lix scores across all languages were statistically significant (p < 0.001).

Articles on AA had a significantly higher mean number of sentences (62 ± 48 vs 44 ± 35) and number of words (1029 ± 748 vs 824 ± 630) than those on AA treatment. AA-treatment articles had a higher mean number of words per sentence (20 ± 7 vs 17 ± 4) than those on AA. All differences were statistically significant (all p < 0.001). Detailed data are presented in Table II.

Table II.

Readability of alopecia areata online materials in 5 European languages

| Language | Search term | Lix | #sentences | #words | w/s | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | alopecia areata | 43 ± 9 | 69 ± 43 | 1,097 ± 649 | 17 ± 6 | 0.004* |

| alopecia areata treatment | 47 ± 5 | 61 ± 41 | 1,003 ± 590 | 17 ± 3 | ||

| German | alopecia areata | 53 ± 5 | 74 ± 65 | 940 ± 678 | 14 ± 3 | 0.119 |

| alopecia areata behandlung | 55 ± 5 | 44 ± 25 | 657 ± 379 | 15 ± 2 | ||

| Italian | alopecia areata | 58 ± 6 | 70 ± 63 | 1,340 ± 1200 | 20 ± 3 | 0.036* |

| alopecia areata cura | 62 ± 6 | 42 ± 49 | 970 ± 1028 | 25 ± 6 | ||

| French | pelade | 51 ± 4 | 61 ± 42 | 1,083 ± 794 | 22 ± 7 | 0.025* |

| pelade traitement | 55 ± 7 | 34 ± 24 | 710 ± 456 | 18 ± 2 | ||

| Spanish | alopecia areata | 52 ± 5 | 41 ± 16 | 780 ± 325 | 19 ± 3 | 0.014* |

| alopecia areata tratamiento | 58 ± 11 | 34 ± 18 | 732 ± 260 | 24 ± 10 |

#: number of; w/s: words/sentence ratio;

statistically significant; p: p-value of difference between AA and AA-treatment Lix score for given language. Data were presented as mean±standard deviation; fifferences across all languages in mean Lix score, number of sentences, words, and words/sentence ratio were all statistically significant (all p < 0.05).

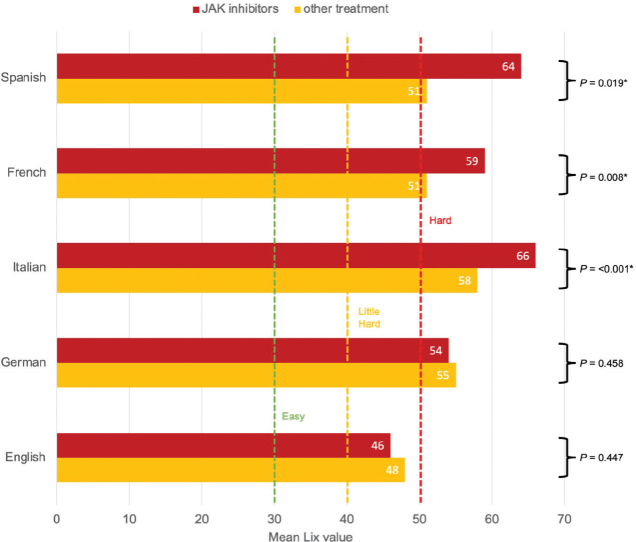

Articles on AA had a mean value of Lix score of 50 ± 8. This was lower than mean value revealed for AA-treatment articles, which was 55 ± 8. The difference was statistically significant (p < 0.001). Overall, articles in both groups were classified as very hard to comprehend. Across all included languages, articles on AA treatment had higher mean Lix scores than those dedicated to AA itself. Except for German (p = 0.119), for all languages individual differences between articles on AA and AA treatment were statistically significant (all p < 0.05). English articles in both groups were hard to comprehend. Articles in remaining languages were in both groups classified as very hard to comprehend. Details are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Readability of alopecia areata and alopecia areata treatment online materials in 5 European languages. Data were presented as mean values. * = statistically significant; p refers to p-value of difference between alopecia areata and alopecia areata treatment Lix score in given language. Difference across all languages in overall mean Lix score was statistically significant (p < 0.001) Easy refers to Lix score < 30 and classifies text as easy to comprehend. Little hard refers to Lix score < 40 and classifies text as s little hard to comprehend. Hard refers to Lix score < 50 and classifies text as hard to comprehend.

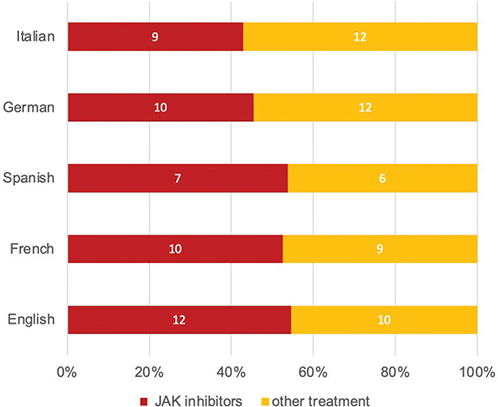

When comparing articles dedicated to treatment, JAK inhibitors had a mean Lix score of 57 ± 10, significantly higher (p = 0.043) than the mean score of 53 ± 6 for articles focusing on other treatment methods. In general, both groups were classified as very hard to comprehend. JAK-inhibitor articles in Spanish, French, and Italian showed a significantly higher (all p < 0.05) mean Lix value than articles on other treatment. Articles in English for both groups were classified as hard to comprehend. The articles in both groups were classified as very hard to comprehend when written in other languages. German and English articles on other treatment had higher average Lix scores compared with those focused on JAK inhibitors. However, these differences were not statistically significant (p = 0.458 and p = 0.447, respectively). Details are presented in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Readability of articles focused on JAK inhibitors and other treatment in 5 European languages. Data were presented as mean values. * = statistically significant; p refers to p-value of difference between JAK inhibitors and other treatment Lix score in given language. Differences across all languages in overall mean Lix score were statistically significant (p < 0.001). Easy refers to Lix score < 30 and classifies text as easy to comprehend. Little hard refers to Lix score < 40 and classifies text as a little hard to comprehend. Hard refers to Lix score < 50 and classifies text as hard to comprehend.

Prevalence and readability

The correlation between the readability of online materials and the number of Google search hits was investigated through univariate linear regression. No significant correlation was observed between the number of hits and the readability of AA articles (R 2 = 0.028, p = 0.787). Similarly, there was no significant correlation between the readability of AA-treatment articles and number of hits (R 2 = 0.711, p = 0.073).

DISCUSSION

Although there were fewer AA-treatment articles compared with those on AA, they posed a greater challenge for potential patients to understand. In all included languages, the readability of AA-treatment articles was lower than those that focused on AA. This can be accounted for by the fact that experts lacked a complete understanding of AA treatment for a considerable amount of time (27, 28). In the past, some authors recommended a “wait and see” approach, but it was rare for patients not receiving active treatment to see hair regrowth (29). Different treatment options for AA showed varying levels of effectiveness and tolerance (27). Treatment options encompassed systemic therapies such as corticosteroids, cyclosporine, methotrexate, and azathioprine, as well as topical remedies like phototherapy and topical immunotherapy (28). The indications, contraindications, mechanisms of action, and possible side effects varied for each of these options (28). It could be assumed that what dermatologists may find challenging to comprehend, an individual without specialized knowledge may find even more daunting. While there were some practice guidelines available, the usual care therapies showed differences as well (27). The author’s individual treatment consensus may be reflected in the materials published on the Internet. Undoubtedly, an article written based on one’s personal comprehension of AA treatment may prove difficult for readers to grasp. The abundance of disorganized information and the poor readability of AA-treatment materials may have contributed to significant misinformation among patients.

Ensuring accurate and current patient information is crucial, especially with the introduction of new and effective JAK inhibitors in clinical practice (10–13, 29). The most recent European guidelines advise the use of baricitinib or ritlecitinib as the first line of treatment for non-acute AA in adults (both above-mentioned JAK inhibitors) and individuals aged 12 years or older (ritlecitinib) (29). On the other hand, it was determined that there was a limited amount of online educational material solely dedicated to JAK inhibitors. Articles discussing JAK inhibitors in English, French, and Spanish were equally represented compared with those centred on other treatments. The number of articles on JAK inhibitors in German and Italian was lower compared with those on other therapies. The recent approval of baricitinib, the first JAK inhibitor for AA, by the FDA and EMA in 2022 is the reason behind this (10, 13). Due to the recent introduction of JAK inhibitors in clinical practice, it could be expected that there is still a plethora of online articles in 2024 debating older treatment methods that may not be as effective. Nevertheless, these options may not be the first ones recommended for patients and could impact their treatment decisions.

Compared with articles discussing alternative treatment options, those focused on JAK inhibitors generally had a lower level of readability. Despite the higher level of comprehensibility in articles concerning other treatments in English and German, there was no significant statistical difference compared with those exclusively discussing JAK inhibitors. This suggests that patient education materials related to JAK inhibitors were not adequately understandable. It is reasonable to assume that the lack of clarity in patient-oriented information could originate from uncertainties about JAK inhibitors expressed by physicians. Long-term effectiveness, relapse rate after discontinuation and very long-term toxicity are still unknown to physicians (2, 30). As medical knowledge advances, physicians could provide more reliable information, improving the readability of articles aimed at the general audience. Despite being recommended by European guidelines as the non-acute first-line treatment for AA, JAK inhibitors should be used with caution in certain populations (29). Patients must be aware of the potential side effects, as well as the potential for significant therapeutic benefits. It is a regular practice for physicians to clarify information obtained from the Internet, underscoring the significance of providing easily comprehensible information on potential life-threatening adverse effects (31). Correspondingly, materials that are difficult to understand may potentially give rise to unattainable hopes in patients, consequently leading to a strain on the therapeutic bond between the physician and the patient, requiring clarification from the physician (31).

Overall, it was determined that all the articles included were very hard to comprehend. The observed level of readability was consistent across all subgroups of articles analysed. This corresponded to college-grade level (32). Only 31.8% of citizens in the EU attained tertiary education (33). Considering this, less than a third of the EU population had a thorough understanding of online materials dedicated to AA and AA treatment.

The results also indicated that quantity did not necessarily equate to readability. In line with another study (23), there were no notable correlations between the frequency of hits and the average Lix scores.

Selection of Google as the search engine could bias the results. The commercial interests of Google influence the promotion of certain materials. The top spots for articles may not necessarily align with the user’s interests. Including the initial 50 articles could potentially create bias. The Google results can vary dynamically depending on the time and location of the search. The research was carried out in Poland. During the period of 4–12 March 2024, the Google search results were generated and examined. There is a chance that conducting data collection in another country could lead to different outcomes. A compilation of articles in the top 5 EU languages may not encompass the full range of online resources focused on the EU public. Inclusion of more languages could produce different results. Lix was originally created to evaluate the readability of Swedish newspaper articles (26). This measure of readability was verified and shown to be accurate in multiple languages (25, 26, 34). Despite its widespread recognition as a reliable indicator of readability within the scientific community (25, 26), the potential need for distinct readability thresholds for each language cannot be disregarded. Assessment of the articles’ quality was not conducted. Although not within the intended scope of this study, this presents an opportunity for future investigation.

In conclusion, this analysis shed light on the obstacles patients confront when trying to make sense of information concerning AA and its treatments. While medical technology has advanced, online materials still fall short in terms of readability, making it difficult for patients to educate themselves and make informed decisions. The introduction of novel therapies like JAK inhibitors underscores the need for accessible patient education on benefits and risks. Presented findings emphasize the importance of ensuring information clarity to bridge the gap between medical expertise and patient comprehension. Simply adding more information is not enough if the readability remains low. The key to empowering patients and strengthening the therapeutic relationship lies in prioritizing the improvement of comprehension of AA-related materials.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding Statement

Funding sources This research was founded by Wroclaw University of Science and Technology, Wroclaw, Poland.

Conflict of interest disclosures

JCS has served as an adviser for AbbVie, LEO Pharma, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Pierre Fabre, Sienna Biopharmaceuticals, and Trevi; has received speaker honoraria from AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, Sun Pharma, and Berlin-Chemie Mennarini; has served as an investigator; and has received funding from AbbVie, Amgen, Galapagos, Holm, Incyte Corporation, InflaRX, Janssen, Menlo Therapeutics, Merck, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Trevi, and UCB. Other authors report no conflicts of interest.

IRB approval status

Human participants and their materials and data were not involved in this study. The study did not involve any animals or animal-based materials. The utilization of Internet data alone rendered ethical approval unnecessary.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ho CY, Wu CY, Chen JYF, Wu CY. Clinical and genetic aspects of alopecia areata: a cutting edge review. Genes (Basel) 2023; 14: 1362. 10.3390/genes14071362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Husein-ElAhmed H, Husein-ElAhmed S. Comparative efficacy of oral Janus kinase inhibitors and biologics in adult alopecia areata: a systematic review and Bayesian network meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024; 38: 835–843. 10.1111/jdv.19797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strazzulla LC, Wang EHC, Avila L, Sicco K Lo, Brinster N, Christiano AM, et al. Alopecia areata: disease characteristics, clinical evaluation, and new perspectives on pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018; 78: 1–12. 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villasante Fricke AC, Miteva M. Epidemiology and burden of alopecia areata: a systematic review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2015; 8: 397–403. 10.2147/CCID.S53985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mostaghimi A, Gao W, Ray M, Bartolome L, Wang T, Carley C, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of alopecia areata, alopecia totalis, and alopecia universalis among adults and children in a US employer-sponsored insured population. JAMA Dermatol 2023; 159: 411–418. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egeberg A, Linsell L, Johansson E, Durand F, Yu G, Vañó-Galván S. Treatments for moderate-to-severe alopecia areata: a systematic narrative review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023; 13: 2951–2991. 10.1007/s13555-023-01044-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Delamere FM, Sladden MJ, Dobbins HM, Leonardi-Bee J. Interventions for alopecia areata. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008: CD004413. 10.1002/14651858.CD004413.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukuyama M, Ito T, Ohyama M. Alopecia areata: current understanding of the pathophysiology and update on therapeutic approaches, featuring the Japanese Dermatological Association guidelines. J Dermatol 2022; 49: 19–36. 10.1111/1346-8138.16207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meah N, Wall D, York K, Bhoyrul B, Bokhari L, Sigall DA, et al. The Alopecia Areata Consensus of Experts (ACE) study: results of an international expert opinion on treatments for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: 123–130. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.European Medicines Agency . Olumiant [cited 2024 Mar 12]. Available from: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/olumiant.

- 11.Pfizer . European Commission approves Pfizer’s LITFULOTM for adolescents and adults with severe alopecia areata. 2023. [cited 2024 Mar 12]. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/european-commission-approves-pfizers-litfulotm-adolescents.

- 12.Pfizer . FDA approves Pfizer’s LITFULOTM (ritlecitinib) for adults and adolescents with severe alopecia areata. 2023. [cited 2024 Mar 12]. Available from: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/fda-approves-pfizers-litfulotm-ritlecitinib-adults-and.

- 13.Lilly . FDA approves Lilly and Incyte’s OLUMIANT® (baricitinib) as first and only systemic medicine for adults with severe alopecia areata. 2022. [cited 2024 Mar 12]. Available from: https://investor.lilly.com/news-releases/news-release-details/fda-approves-lilly-and-incytes-olumiantr-baricitinib-first-and.

- 14.Numata T, Irisawa R, Mori M, Uchiyama M, Harada K. Baricitinib therapy for moderate to severe alopecia areata: a retrospective review of 95 Japanese patients. Acta Derm Venereol 2024; 104: adv18348. 10.2340/actadv.v104.18348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moreno-Vílchez C, Bonfill-Ortí M, Bauer-Alonso A, Notario J, Figueras-Nart I. Baricitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata in adults: real-world analysis of 36 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 2024; 90: 1059–1061. 10.1016/j.jaad.2023.09.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.De Greef A, Thirion R, Ghislain PD, Baeck M. Real-life effectiveness and tolerance of baricitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata with 1-year follow-up data. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2023; 13: 2869–2877. 10.1007/s13555-023-01030-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borgmann H, Mager R, Salem J, Bruendl J, Kunath F, Thomas C, et al. Robotic prostatectomy on the web: a cross-sectional qualitative assessment. Clin Genitourin Cancer 2016; 14: e355–e362. 10.1016/j.clgc.2015.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borgmann H, Wölm JH, Vallo S, Mager R, Huber J, Breyer J, et al. Prostate cancer on the web: expedient tool for patients’ decision-making? J Cancer Educ 2017; 32: 135–140. 10.1007/s13187-015-0891-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prestin A, Vieux SN, Chou Wying S. Is online health activity alive and well or flatlining? Findings from 10 years of the Health Information National Trends Survey. J Health Commun 2015; 20: 790–798. 10.1080/10810730.2015.1018590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.statistica.com . Market share of leading search engines worldwide from January 2015 to January 2024 [Internet]. 2024. [cited 2024 Mar 6]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1381664/worldwide-all-devices-market-share-of-search-engines/

- 21.Google Inc . How Google determines the language of search results [Internet] [cited 2024 Mar 6]. Available from: https://support.google.com/websearch/answer/13511324?hl=en-PL&visit_id=638453336335039611-245544975&p=language_search_results&rd=1#zippy=%2Cdisplay-language-setting.

- 22.Cuan-Baltazar JY, Muñoz-Perez MJ, Robledo-Vega C, Pérez-Zepeda MF, Soto-Vega E. Misinformation of COVID-19 on the Internet: Infodemiology Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020; 6: e18444. 10.2196/18444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beauharnais CC, Aulet T, Rodriguez-Silva J, Konen J, Sturrock PR, Alavi K, et al. Assessing the quality of online health information and trend data for colorectal malignancies. J Surg Res 2023; 283: 923–928. 10.1016/j.jss.2022.10.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keating D. Despite Brexit, English remains the EU’s most spoken language by far. Forbes Retrieved 2020; 7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Calafato R, Gudim F. Literature in contemporary foreign language school textbooks in Russia: content, approaches, and readability. Language Teach Res 2022; 26: 826–846. 10.1177/1362168820917909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson J. Lix and rix: variations on a little-known readability index. J Reading 1983; 26: 490–496. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee H, Huang KP, Mostaghimi A, Choudhry NK. Treatment patterns for alopecia areata in the US. JAMA Dermatol 2023; 159: 1253–1257. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meah N, Wall D, York K, Bhoyrul B, Bokhari L, Sigall DA, et al. The Alopecia Areata Consensus of Experts (ACE) study: results of an international expert opinion on treatments for alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020; 83: 123–130. 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rudnicka L, Arenbergerova M, Grimalt R, Ioannides D, Katoulis AC, Lazaridou E, et al. European expert consensus statement on the systemic treatment of alopecia areata. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2024; 38: 687–694. 10.1111/jdv.19768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dainichi T, Iwata M, Kaku Y. Alopecia areata: what’s new in the diagnosis and treatment with JAK inhibitors? J Dermatol 2024; 51: 196–209. 10.1111/1346-8138.17064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan SSL, Goonawardene N. Internet health information seeking and the patient-physician relationship: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 2017; 19: e9. 10.2196/jmir.5729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.readable.com [cited 2023 Mar 19]. Available from: https://readable.com/blog/the-lix-and-rix-readability-formulas/

- 33.eurostat . Educational attainment statistics [cited 2023 Mar 19]. Available from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Educational_attainment_statistics#Educational_attainment_levels_vary_between_age_groups.

- 34.Björnsson CH. Readability of newspapers in 11 languages. Read Res Q 1983; 480–497. 10.2307/747382 [DOI] [Google Scholar]