Abstract

Aligned with the increasing importance of bioorthogonal chemistry has been an increasing demand for more potent, affordable, multifunctional, and programmable bioorthogonal reagents. More advanced synthetic chemistry techniques, including transition-metal catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, C-H activation, photo-induced chemistry, and continuous flow chemistry have been employed in synthesizing novel bioorthogonal reagents for universal purposes. In this chapter, we will discuss recent developments of the synthesis of popular bioorthogonal reagents, with a focus on s-tetrazines, 1,2,4-triazines, trans-cyclooctenes, cyclooctynes and hetero-cycloheptynes and -trans-cycloheptenes. This review aims to summarize and discuss the most representative synthetic approaches of these reagents and their derivatives that are useful in bioorthogonal chemistry. The preparation of these molecules and their derivatives utilizes both classic approaches as well as the latest organic chemistry methodologies.

Keywords: synthesis, tetrazine, trans-cyclooctene, triazine, cyclooctyne, bioorthogonal

Introduction

Design and synthesis of new bioorthogonal reagents or modification of existing chemistry tools plays a pivotal role in the realm of bioorthogonal chemistry. Different from the chemistry used in reaction vessels, the chemistry that is suitable for use in a biological environment needs to meet unique requirements. Ideally, the reaction must be rapid at low concentrations. The reagents should be small, stable, and selective enough to refrain from interfering with native biochemical processes. In some circumstances, specific bioorthogonal reactions or reagents have to be mutually orthogonal in order to simultaneously monitor multiple biological processes. In addition, cytotoxicity is another important concern. In the past two decades, efforts have been made to construct more powerful, inexpensive, multifunctional, and tunable bioorthogonal reagents. More advanced synthetic chemistry techniques, including transition-metal catalyzed cross-coupling reactions, C-H activation, photo-induced chemistry, continuous flow chemistry, and enzyme-catalyzed reactions have been employed in synthesizing novel bioorthogonal reagents for universal purposes. In this chapter, we discuss recent developments of the synthesis of popular bioorthogonal reagents, with a focus on s-tetrazines, 1,2,4-triazines, trans-cyclooctenes, cyclooctynes and hetero-cycloheptynes and -trans-cycloheptenes. These reagents factor prominently in strain promoted azide-alkyne cyclooaddition (SPAAC) and inverse electron demand Diels-Alder (IEDDA) reactions, which are two of the most important classes of bioorthogonal reactions. SPAAC reactions remain incredibly popular due their ability to proceed efficiently without cytotoxic catalysts. SPAAC also benefits from the versatility of using azide reagents, which are most readily accessed and incorpated into biological systems. iEDDA reactions are especially notable for their rapid kinetics without the need for catalysis. This is especially for the tetrazine ligation which functions rapidly at low concentrations in living systems. Efficiently accessing the reagents needed for SPAAC and IEDDA has presented some of the greatest synthetic challenges in the field, and consequently has led to a range of interesting new methodologies. This review aims to summarize and discuss the most representative synthetic approaches of these reagents and their derivatives that are useful in bioorthogonal chemistry. The preparation of these molecules and their derivatives typically involves multiple step synthesis using both classic approaches as well as the latest organic chemistry methodologies.

3.1. Synthesis of s-tetrazines from nitriles

Tetrazine derivatives were first synthesized via the condensation of iminoether salts with excess hydrazine, followed by oxidation as reported by Pinner in 1893.[1–2] With hesitation, Pinner suggested the name tetrazine (“ich keinen besseren vorzuschlagen habe”) to describe monocyclic aromatics containing four nitrogens.[1] Pinner’s method represented a two-step synthesis of symmetrical tetrazines from nitriles, as Pinner had previously shown that iminoether salts can be prepared via the partial solvolysis of nitriles under acidic conditions.[3–5] Early in the 20th century, methods for directly preparing tetrazines from the direct condensation of nitriles with hydrazine were introduced by Hofmann[6] and Müller.[7] Over a century later, these methods, along with more recent variants that employ catalysts, remain the most widely used ways to prepare tetrazines. (Scheme 3.1.1)

Scheme 3.1.1.

Early methods of tetrazine syntheses

As activated carboxylic acid derivatives, formamidines have been used in s-tetrazine synthesis to prepare monofunctionalized tetrazines. For example, 3-phenyl-s-tetrazine was synthesized via a one-pot procedure using methyl benzimidate hydrochloride and formamidine acetate (1: 3 molar ratio) with hydrazine hydrate in 85% yield.[8] Additionally, substituted amidines have also been employed in the preparation of 3,6-disubstituted unsymmetrical tetrazines (s-tetrazines).[9]

The parent s-tetrazine can be prepared through the reaction of formamidine acetate with hydrazine[10–12] (Scheme 3.1.2). Due to its low molecular weight, the parent s-tetrazine is extremely volatile, subliming at atmospheric pressure. While multigram preparations of this compound have been reported, it should be handled with caution as the safety profile of the compound has not been evaluated. Heterocycle nitriles, such as 2-cyanopyridine derivatives, have been demonstrated to react with formamidine acetate, producing monosubstituted tetrazines with moderate yields.[13–14]

Scheme 3.1.2.

Sauer’s synthesis of s-tetrazine from formamidine acetate

A number of additives and catalysts have been developed to promote the condensation of nitriles with hydrazine towards dihydrotetrazines. Sulfur has been reported to enhance the synthesis of a series of symmetrical 3,6-diaryl-s-tetrazines from aromatic nitriles and hydrazine hydrate in ethanol, resulting in excellent yields.[15–17] This method is predominately suited for aromatic nitriles and gives unsatisfactory yields when aliphatic nitriles are employed.[18–19] In 2004, a mechanism for the sulfur-induced condensation reaction involving the intermediacy of mercaptohydrazine was proposed.[20] Heterogenous metals, such as Raney nickel, were reported to promote tetrazine formation;[21] however, in subsequent studies, the effect of Raney nickel was disputed.[22–23] Meanwhile, a Cu-Zn catalyst was found to be effective in synthesizing symmetrical tetrazines from hydrazine hydrate and aryl/benzyl nitriles.[18]

In 2012, Devaraj and coworkers reported the Lewis acid-catalyzed, one-pot synthesis of tetrazines from nitriles and anhydrous hydrazine (Scheme 3.1.3).[24] With the presence of catalytic nickel (II) triflate or zinc (II) triflate, otherwise poorly reactive aliphatic nitriles were activated for nucleophilic addition of hydrazine. This nucleophilic addition of hydrazine is speculated as the first step in tetrazine formation. Using this approach, a variety of both symmetrical and unsymmetrical s-tetrazines were synthesized. It was also demonstrated that these Lewis acids effectively catalyzed reactions with aromatic nitriles and formamidine, producing monosubstituted tetrazines in good yields. Under similar conditions, condensation reactions between nitriles and excess acetonitrile resulted in unsymmetrical 3-methyl-6-substituted tetrazines.

Scheme 3.1.3.

Lewis-acid catalyzed synthesis of (A) disubstituted and (B) monosubstituted tetrazines.

The Lewis-acid catalyzed method for synthesizing tetrazines has since become widely adopted.[25–31] This method has facilitated the creation of tetrazines furnished with various functional groups, including trifluoromethyl, aniline, and diethylamide groups.[13, 15] This approach has also been employed in the preparation of fluorophore-tetrazine conjugates. For example, a series of coumarin conjugated tetrazines were synthesized from cyano-coumarin derivatives and anhydrous hydrazine, in the presence of zinc (II) triflate using either acetonitrile or formamidine acetate (Scheme 3.1.4A).[32] In general, the yields for 6-methyl-s-tetrazine coumarin dyes (from MeCN) were typically higher than those for monosubstituted analogs (from formamidine acetate). BODIPY-conjugated tetrazines were synthesized from a BODIPY functionalized benzonitrile derivative and anhydrous hydrazine in the present of zinc (II) triflate (Scheme 3.1.4B).[32] Interestingly, both the 6-methyl and monosubstituted derivatives were formed in this reaction with acetonitrile as solvent. Moreover, this Lewis-acid catalyzed method for tetrazine synthesis was applied in synthesizing tetrazine groups on the side chains of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-and poly(ethylene glycol)-based polymers.[33]

Scheme 3.1.4.

(A) Tetrazine-conjugated coumarin dyes prepared by Lewis-acid catalyzed formation of tetrazines from nitrile precursors. (B) Tetrazine-conjugated BODIPY prepared by Lewis-acid catalyzed formation of tetrazines from nitrile precursors.

More recently, it was discovered that thiol-containing reagents can facilitate the formation of tetrazines from nitriles and hydrazine hydrate (Scheme 3.1.5).[34] It was proposed that the thiols serve as nucleophilic catalysts, activating the nitriles into hydrazine-reactive thioimidate ester intermediates. A notable advantage of this method over metal-catalyzed nitrile/hydrazine condensation is the use of hydrazine hydrate instead of anhydrous hydrazine, as the latter is more tightly regulated and might not be commercially available in many regions, including China and Europe. Additionally, the safety profile of the thiol-catalyzed method is further enhanced by its milder conditions (conducted at room temperature) and the use of a solvent (ethanol). Both symmetrical and unsymmetrical tetrazine were synthesized in good yields using this method (Scheme 3.1.5A). A tetrazine phosphate was also successfully synthesized on gram scale, serving as a precursor in a subsequent Horner–Wadsworth–Emmons (HWE) reaction with aldehydes for additional derivatization (Scheme 3.1.5B).

Scheme 3.1.5.

(A) Thiol-catalyzed tetrazine synthesis (B) applied to the creation of a tetrazine-substrate for HWE-reactions.

Alternatively, gem-1,1-dihalo compounds can also act as precursors to tetrazines. In 1958, Carboni and Lindsey demonstrated that fluoroolefins can be converted into symmetrical 3,6-disubstituted tetrazines by reacting with hydrazine hydrate in hydroxylic solvent followed by an oxidation reaction with concentrated nitric acid.[35] More recently, this chemistry was further explored by Hu and coworkers,[36] demonstrating that both symmetrical and unsymmerical tetrazines can be prepared from gem-difluoroalkenes at room temperature, using ambient air as the terminal oxidant.

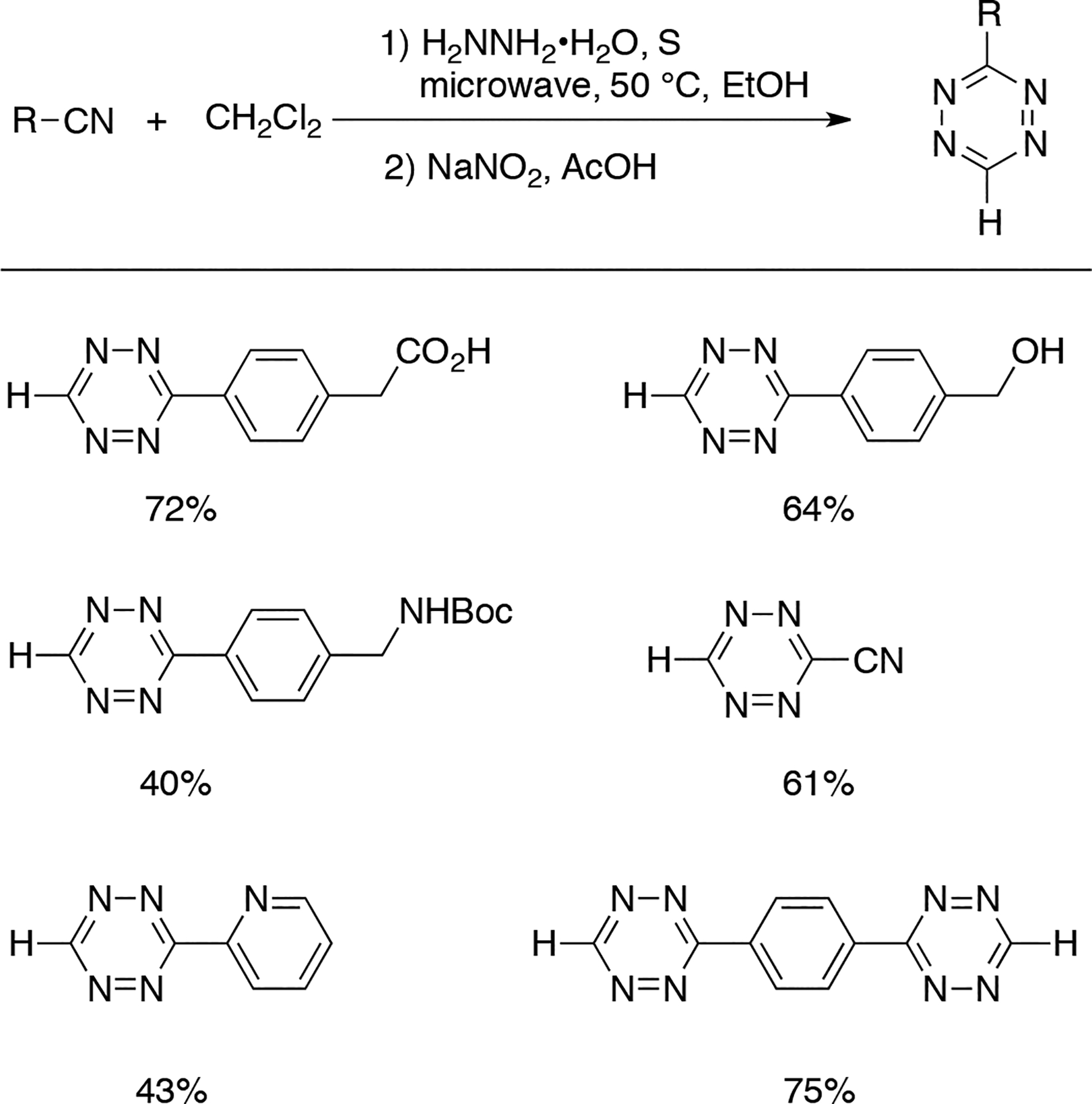

In 2018, Audebert reported a method for the synthesizing mono-substituted tetrazines using nitriles and hydrazine hydrates in the presence of dichloromethane. Uniquely, dichloromethane was used as the counter-electrophile instead of formamidine. Sulfur and microwave irradiation were also employed to promote the reaction. The involvement of dichloromethane in the reaction was confirmed by an NMR study, in which 13C-labeled dichloromethane was used as the reactant. The authors speculated that the addition of sulfur may facilitate a substitution reaction between dichloromethane and one equivalent of sulfur-activated hydrazine, followed by an addition reaction involving another equivalent of hydrazine. Ultimately, the initially formed dihydrotetrazines were oxidized by NaNO2 to yield the desired tetrazine products (Scheme 3.1.6).[37]

Scheme 3.1.6.

Selected examples of mono-substituted tetrazines synthesized using dichloromethane as a reagent.

3.2. Synthesis from Bischlorimidates

In 1905, Stollé first described a stepwise synthesis of s-tetrazines via bischlorimidate intermediates(Scheme 3.2.1).[38] A variety of functional groups including halogen, nitro, CF3, and phenolic groups, are tolerated under the reaction conditions.[39–41] This method has been used in the synthesis of tetrazine-based insecticides,[42] corranulene derivatives[43] 3,6-bis(trifluoromethyl)-1,4-dihydro-s-tetrazine,[44] bis-s-tetrazines,[45] and [3.3]paracyclophanes.[46] Compounds such as 3,6-diaryl-s-tetrazines, dipyridyl-s-tetrazines, dibenzyl-s-tetrazines, and a select group of dialkyl-s-tetrazines can be prepared using this approach. A notable advantage of this method is its capability to produce unsymmetrical tetrazines. However, functional group tolerance islimited due to the extremely acidic and basic conditions required.

Scheme 3.2.1.

s-Tetrazine synthesis from bischlorimidates.

Bischlorimidates have been used as precursors for 1,4-dihydro-s-tetrazine as reported by Neugebauer et al..[47] In this study, it was demonstrated that the 1,4-dihydro-s-tetrazine isomer is more stable than the corresponding 1,2-dihydro-tetrazine tautomer. The bischlorimidate approach was also employed to synthesize and investigate the antitumor activity of a series of 3,6-disubstituted-1,4-dihydro-s-tetrazine derivatives.[36] In 2012, Ting and coworkers used bischlorimidate as the key intermediate in synthesizing 3-(3-nitrophenyl)-6-(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)-s-tetrazine, a probe for cellular labeling study.[48] In 2013, Wang et al. described the synthesis of unsymmetrical s-tetrazines from the corresponding N,N ′-diacylhydrazines and bischlorimidates.[39] In a subsequent study, they also demonstrated that microwave irradiation can expedite tetrazine formation.[40]

3.3. Synthesis from diazo dimerization

Dimethyl s-tetrazine-3,6-dicarboxylate can be prepared in good yield via the dimerization[49–55] of ethyl diazoacetate under basic conditions, followed by esterification and oxidation (Scheme 3.3.1).[56] In the presence of amines, the dimerization of ethyl diazoacetate proceeds with concomitant amidation, yielding 1,4-dihydro-s-tetrazine-3,6-dicarboxamides. Dimethyl s-tetrazine-3,6-dicarboxylate can be desymmetrized either through transesterification[57] or by reaction with AlMe3.[58] Both 3,6-bisphosphinyl and 3,6-bisphosphanyl-s-tetrazine derivatives can be synthesized from the corresponding diazo compounds.[59] While tetrazine-dicarboxylates are useful in natural products synthesis, their application in bioorthogonal chemistry has been limited due to their instability in aqueous conditions.

Scheme 3.3.1.

Synthesis of Dimethyl s-tetrazine-3,6-dicarboxylate

3.4. Synthesis from condensation of bis(carboxymethyl)trithiocarbonates and orthoesters

Another method for the synthesis of s-tetrazines involves the condensation reactions of thiocarbohydrazide. When reacted with bis(carboxymethyl)trithiocarbonate,[60] thiocarbohydrazide undergoes a condensation to produce s-tetrazinane-3,6-dithione. This compound was then alkylated to yield a dihydrotetrazine species, which was readily oxidized to form 3,6-bis(methylthio)-s-tetrazine. (Scheme 3.4.1). Further modification of 3,6-bis(methylthio)-s-tetrazine can be achieved via nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) reactions, as is commonly used with 3,6-dichloro-s-tetrazine[61] and 3,6-(3,5-dimethylpyrazolyl)-s-tetrazine.[62–64]

Scheme 3.4.1.

Preparation of bis(methylthio)-s-tetrazine

Unsymmetrical 3-thioalkyltetrazines can be prepared from the reaction of S-alkylthiocarbohydrazide salts with alkyl- or aryl orthoesters.[65–66] Apart from orthoesters, amide acetals and Vilsmeier-type salts can serve as suitable electrophiles in this condensation reaction with thiocarbohydrazide.[66] In 2019, the Fox lab reported that the reagent 3-((p-biphenyl-4-ylmethyl)thio)-6-methyltetrazine (b-Tz) could be readily prepared via a one-pot method on a decagram scale using orthoesters.[65] This method avoids the handling of hydrazine and eliminates the formation of volatile, high-nitrogen containing tetrazine byproducts (Scheme 3.4.2). A new Cu(OAc)2-catalyzed procedure was developed to promote the oxidation of the dihydrotetrazine precursor under ambient air conditions. The DSC profile indicates that b-Tz has an onset temperature of 170 °C and a transition enthalpy of 900 J/g. Therefore b-Tz is not flagged as potentially shock sensitive or explosive according to the Pfizer-modified Yoshida correlation. As discussed in section 3.5, b-Tz serves as a reagent for introducing the 6-methyltetrazin-3-yl group via Ag-mediated Liebeskind-Srogl cross-coupling reactions. [65]

Scheme 3.4.2.

Large scale preparation of a thioalkyltetrazine with applications in cross-coupling chemistry

Initial procedures for preparing thioalkyltetrazines were limited to trimethyl- and triethylorthoesters. These orthoesters cannot be prepared directly from esters but instead require nitrile precursors and harshly acidic conditions.[66] In 2020, the Fox lab described a general, one-pot procedure for converting (3-methyloxetan-3-yl)methyl carboxylic esters to unsymmetrical 3-thiomethyltetrazines via condensation of oxabicyclo[2.2.2] octyl (OBO)[67] intermediates with S- methylisothiocarbonohydrazidium iodide, followed by an oxidation reaction (Scheme 3.4.3).[68] The activated esters can be efficiently prepared from the corresponding carboxylic acids and inexpensive 3-methyl-3-oxetanemethanol. The obtained thioalkyltetrazines serve as valuable reagents for unsymmetrical and monosubstituted tetrazine synthesis via Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions.

Scheme 3.4.3.

One-pot synthesis of thiomethyltetrazines from ester precursors.

3.5. Transition metal catalyzed cross-coupling reactions

Transition metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions have been recognized as one of the most powerful methods for constructing carbon-carbon bonds.[69] To expand access to unsymmetrical s-tetrazine derivatives, transition metal-catalyzed coupling reactions have recently been employed to directly functionalize the s-tetrazine core ring or modify various substituents on tetrazines.

3.5.1. Coupling reactions to form direct bonds to a tetrazine ring

The first cross-coupling reaction involving s-tetrazines was reported by Kotschy and coworkers in 2013.[70] In this study, amino-functionalized chlorotetrazines were shown to undergo palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction with various terminal alkynes under either Sonogashira or Negishi conditions, furnishing amino-alkynyl-s-tetrazines in good yields (Scheme 3.5.1).

Scheme 3.5.1.

Palladium catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of chlorotetrazines and different terminal alkynes.

Guillaumet and coworkers prepared 3-methylthio-6-(morpholin-4-yl)-s-tetrazine and successfully used it as a starting material in Liebeskind-Srogl couplings. With microwave heating, the coupling reaction with either arylboronic acids or arylstannanes delivered unsymmetrical s-tetrazine in moderate to good yields (Scheme 3.5.2).[71]

Scheme 3.5.2.

Liebeskind-Srogl couplings of 3-methylthio-6-(morpholin-4-yl)-s-tetrazine with arylboronic acids or arylstannanes.

In 2017, Lindsley and coworkers developed a general method for the cross couplings of 3-amino-6-chloro-s-tetrazines with aryl- or heteroaryl boronic acids. Under mild conditions and using the BrettPhos Pd G3 precatalyst, they synthesized a panel of new unsymmetrical s-tetrazines in moderate to high yields (Scheme 3.5.3).[61]

Scheme 3.5.3.

Palladium catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of chlorotetrazines and different boronic acids.

The Buchwald–Hartwig amination reactions have been used to convert symmetrical 3,6-dimethylsulfanyl-1,2,4,5-tetrazine into 3-amino-s-tetrazine derivatives.[72] All of the above-mentioned studies have been aimed at synthesizing 3-aminotetrazine products, which are valuable in medicinal chemistry. However, for applications in bioorthogonal chemistry, the reactivity of 3-aminotetrazines is attenuated by the deactivating amino substituents.[27, 73]

In 2019, the Fox lab developed a general synthesis of 3-aryl-6-methyl s-tetrazine derivatives via the first example of silver-mediated Liebeskind–Srogl cross-coupling (Scheme 3.5.4).[65]. In this study, the coupling partner b-Tz was readily synthesized on large scale in one-pot, resulting from a condensation reaction of methyl orthoester followed by an oxidation reaction (Scheme 3.4.2). After performing the silver-mediated Liebeskind–Srogl cross-coupling reaction with boronic acids, various aromatic functional groups were readily installed directly onto the 6-methyl s-tetrazine core ring, affording 6-methyl s-tetrazine derivatives with moderate to excellent yields. Since 3-aryl-6-methyltetrazines are widely recognized as some of the most attractive bioorthogonal reagents, this general method will facilitate the preparation of these bioorthogonal tetrazine probes.

Scheme 3.5.4.

Substrate scope of the palladium catalyzed silver-mediated Liebeskind–Srogl cross-coupling of b-Tz.

As discussed in Section 3.4, the Fox lab has also developed a new method for preparing thioalkyltetrazines from carboxylic ester precursors (Scheme 3.4.3). [68] These thioethers were employed as common intermediates for the synthesis of unsymmetrical tetrazines via Pd- catalyzed cross-coupling with arylboronic acids or stannylvinylethers. Moreover, the palladium-catalyzed thioether reduction provided access to the popular monosubstituted tetrazines used in bioorthogonal chemistry. This divergent method can tolerate a broad range of aliphatic and aromatic ester precursors. Heterocycles such as BODIPY fluorophores and biotin are also suitable for this tetrazine synthesis approach (Scheme 3.5.5). Additionally, a series of tetrazine probes for monoacylglycerol lipase (MAGL) were synthesized, and the most reactive one was applied in labeling of endogenous MAGL in live cells.[68]

Scheme 3.5.5.

The divergent synthesis of unsymmetrical s-tetrazines and monosubstituted tetrazines.

In 2017, Wombacher and coworkers demonstrated that 3-bromo-6-methyl-s-tetrazine was a suitable building block for the Stille coupling with a MOM protected fluorescein stannane reagent. The 3-bromo-6-methyl-s-tetrazine was prepared from 3-hydrazinyl-6-methyl-s-tetrazine. After the cross-coupling reaction, both fluorescein and Oregon Green conjugated tetrazines were synthesized in moderate yields.[74] (Scheme 3.5.6 A)

Scheme 3.5.6.

(A) Stille coupling of 3-bromo-6-methyl-s-tetrazine for the construction of a fluorescein-tetrazine conjugate. (B) Ag-mediated Suzuki couplings of 3-bromotetrazine.

Recently, Gademann and coworkers reported the use of 3-bromotetrazine in nucleophilic aromatic substitution reactions with a variety of nitrogen, sulfur, and phenol-based nucleophiles.[75] Contemporaneously, Ros and colleagues present a synthesis of 3-bromotetrazine and associated nucleophilic substitution reactions towards monosubstituted s-tetrazines.[76] In their study, they explored the utility of these new monosubstituted s-tetrazines in click-to-release reactions for prodrug activation purposes. In both cases, 3-bromo-s-tetrazine was synthesized through the bromination of 3-hydrazinyl-s-tetrazine. In 2021, the Gademann group reported a Ag-mediated Pd-catalyzed cross-coupling method for 3-bromo-1,2,4,5-tetrazine with a variety of boronic acids, targeting the synthesis of H-tetrazines.[77](Scheme 3.5.6 B)

3.5.2. Cross-coupling reactions to pendant substituents on s-tetrazines

Transition metal-catalyzed reactions have also been employed to couple functional groups to substituents already attached to s-tetrazines. In 2003, Sołoducho and coworkers reported Pd-catalyzed Stille reactions of 3,6-di(4-iodo)- and 3,6-di(4-bromophenyl)-s-tetrazine for the attachment of 2-thienyl substituents.[78] In 2010, Ding and coworkers described the synthesis of polymers using Stille couplings of 3,6-bis(5-bromothiophen-2-yl)-s-tetrazine to produce materials for solar cell applications.[79] Wombacher et al. synthesized fluorogenic s-tetrazines conjugated with fluorescein or BODIPY fluorophores via Sonogashira and Stille coupling.[80] (Scheme 3.5.7). Stille couplings of 3,6-di(4-bromo)- and 3,6-di(3-bromophenyl)-s-tetrazine were used to prepare triphenylamine/tetrazine-based π-conjugated systems for use as molecular donors in organic solar cells.[81]

Scheme 3.5.7.

Sonogashira reactions of 3-methyl-6-(4-iodophenyl)-s-tetrazine for the construction of fluorophores with extended conjugation.

A series of pi-conjugated tetrazines was synthesized by Devaraj and coworkers via the Heck reactions of in-situ generated vinyl tetrazine intermediates (Scheme 3.5.8). The ideal catalyst for the transformation was generated from Pd2DBA3 and the sterically demanding Q-Phos ligand. This method was applied to the synthesis of tetrazine conjugates of biologically relevant molecules as well as fluorophores. A series of fluorogenic tetrazine probes, which exhibit a strong fluorescence turn-on (up to 400-fold) property, were prepared and used in live-cell imaging experiments.[27]

Scheme 3.5.8.

Heck-type reactions of in situ generated vinyltetrazines with arylhalides.

In 2020, the Audebert group reported the functionalization of s-tetrazine using the Buchwald–Hartwig cross-coupling reaction, affording seven new donor–acceptor tetrazine molecules in high yields.[82] To prevent the decomposition of the tetrazine core, weak inorganic carbonate bases, such as Cs2CO3, were employed in the cross-coupling reaction.

3.5.3. C-H Functionalization to pendant substituents on s-tetrazines

The synthesis of s-tetrazines bearing ortho-functionalized aromatic rings can be challenging. One approach to preparing this class of tetrazines is through the bischlorimidate method described in section 3.2 [43] However, this multistep approach often results in a low yield of the final product. In 2016, Hierso and coworkers introduced a general method for the synthesis of aryl s-tetrazines with ortho-functionalized aromatic rings via palladium-catalyzed, ortho-directed C−H activation.[83] (Scheme 3.5.9 A). This method facilitated the introduction of reactive carbon–halogen (X=I, Br, Cl) and C−O bonds to the ortho position of the pendant aromatic rings. By tuning protocols, valuable mono-, di-, tri-, and tetra ortho-functionalized aryl tetrazines were synthesized with good yields and selectivity. Subsequently, Hierso and coworkers extended this methodology, sequentially introducing two or three selective ortho halogenation reactions, which enabled the synthesis of ortho-substituted unsymmetrical s-tetrazines.[84] Using this protocol, a rare tetrahalogenated s-aryltetrazines bearing four distinct functional groups was synthesized in 34% yield. These ortho-halogenated s-tetrazine derivatives were further converted to bis(biphenyl)tetrazines and a unique class of doubly clickable bis(tetrazines). The same group also described the selective incorporation of O, S, N, and P heteroatoms at the ortho-position of s-aryl tetrazine. [84–86] In 2020, Xu and coworkers reported an iridium-catalyzed ortho C-H amidation of s-tetrazine.(Scheme 3.5.9 B) Using this methodology, a variety of ortho C-H amidation products of s-tetrazines with diverse functional group tolerance were successfully prepared in high yields.[87] These s-tetrazines featuring ortho amino functional groups, were used as modular building blocks for DNA-encoded library synthesis. Recently, Hierso and coworkers highlighted the use of alkali halides as nucleophilic reagent sources for N-directed palladium-catalyzed ortho-C–H halogenation of s-tetrazines.[88]

Scheme 3.5.9.

C-H activation of the installation of ortho-functional groups via (A) Pd-catalyzed halogenation or acetoxylation and (B) Iridium-catalyzed amination.

3.6. Nitrile Imine Dimerization

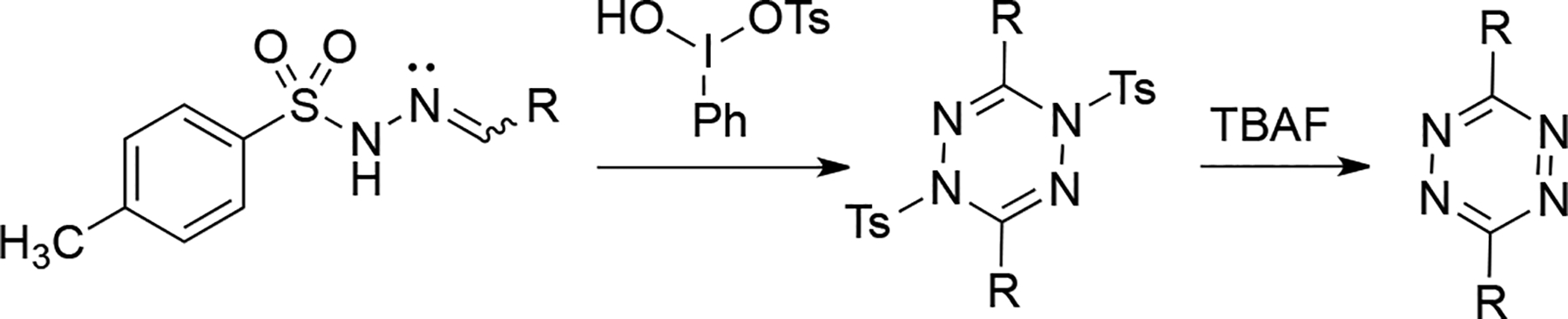

5-Phenyl-2H-tetrazole has been used as a suitable precursor to generate tetrazines via nitrile imine intermediates under photolysis[89–90] or thermolysis conditions. [91] 5-Phenyl-2-tosyl-2H-tetrazole undergoes thermolysis at40°C (just above room temperature), generating the nitrile imine intermediates with a tosyl group at the terminal nitrogen atom. This intermediate subsequently dimerizes to form 1,4-di-(p-tosyl)-3,6-diphenyl-1,4-dihydro-s-tetrazine along with the deprotected diphenyl s-tetrazine.[92] It was also described that photolysis of 4-phenyltriazole produced 3,6-diphenyltetrazine, presumably from benzonitrilimine following the photoelimination of hydrogen cyanide.[93] Hypervalent iodine reagents, such as Koser’s reagent, have also been used to trigger the formation of nitrile imine intermediates from N-tosylhydrazones. Symmetrical s-tetrazine products were produced in good yields following nitrile imine dimerization, deprotection, and oxidation.[94] (Scheme 3.6.1.)

Scheme 3.6.1.

Formation of symmetrical 3,6-disubstituted s-tetrazines via nitrile imine dimerization.

3.7. Methods of dihydrotetrazine oxidation

Many of the previously mentioned methods for s-tetrazine synthesis rely on the oxidation of dihydro-s-tetrazine precursors. Nitrous reagents (e.g., NaNO2, isoamylnitrite, nitrous acid, nitrogen (II) oxide) are commonly used to oxidize 1,4-dihydro-s-tetrazines to tetrazines. While this method proves effective with numerous dihydro-s-tetrazine substrates, the conditions are harsh and modest yields are reported in several cases.[41, 95–97] Moreover, oxidation by nitrous agents is unsuccessful for substrates with sensitive amino substituents.[98] DDQ is an alternative oxidant, [98–100] however, in certain cases, only moderate yields were obtained[101–102] and the chromatography purification can be challenging.[103] Air has been utilized as a terminal oxidant in the synthesis of 3,6-dialkyl-s-tetrazines.[104–105] m-CPBA and benzoyl peroxide were also effective in converting dihydro-s-tetrazines to s-tetrazines.[103] Inorganic oxidants, such as iron (III) chloride,[106] manganese (IV) oxide[107] and chromium (VI) oxide[108] have also been used for the oxidation of dihydro-s-tetrazines. A perfluoroalkyl analog of chloramine-T was shown to oxidize a dihydrotetrazine bearing a trialkylstannyl group to a tetrazine, while also iodinating the trialkylstannyl functional group.[109] Similar results were also achieved by using iodogen as oxidant.[110]

Cu(OAc)2 has been proven effective in catalyzing the large scale oxidation of 3-((p-biphenyl-4-ylmethyl)thio)-6-methyltetrazine in air. [65] A systematic evaluation of different oxidants for an amine-functionalized dihydro-s-tetrazine identified PhI(OAc)2 as the most efficient. This oxidant can also be used to produce a wide range of s-tetrazines from dihydro-s-tetrazine precursors, leading to 75–98% yield[103] (Scheme 3.7.1).

Scheme 3.7.1.

PhI(OAc)2 as an effective reagent for oxidation of dihydrotetrazines.

Besides chemical oxidants, both photocatalytic oxidation and enzyme oxidation (horseradish peroxidase) of dihydrotetrazine to tetrazine species has been described.[111–114] Photocatalysts for these processes include fluorescein dyes with 470 nm light, Rose Bengal with 550 nm light, and silarhodamine dyes or methylene blue with 660 nm light. The photochemical processes were shown to consume O2 and produce hydrogen peroxide. To date, the applications of these methods have been biological with demonstrations of in vivo crosslinking in live mice, spatiotemporally-controlled subcellular 3D-patterning in live cells, and intracellular uncaging inside live cells.[111–114] However, the efficiency of these processes suggests that more straightforward applications in preparative tetrazine synthesis will also be worth exploration.

3.8. 1,2,4-Triazines synthesis for Bioorthogonal Chemistry

Despite extensive study on the utilization of 1,2,4-triazines in drug development and natural products total synthesis [115] the application of 1,2,4-triazines in bioorthogonal chemistry was not emerged until Prescher’s seminal work published in 2015.[116] In this work, a monosubstituted 1,2,4-triazine was found to react smoothly with trans-cyclooctene (TCO), yet it was inert in the cycloaddition reaction with either norbornenes or cyclopropenes under biologically relevant conditions. The synthesis of functionalized 1,2,4-triazines starts from 3-amino-1,2,4-triazine, which was readily prepared from condensation reaction with glyoxal and aminoguanidine in water under basic conditions (Scheme 3.8.1 A). To introduce amino groups onto the triazine, the obtained 3-amino-1,2,4-triazine was treated with bromine, producing a bromo handle suitable for Suzuki coupling. Subsequently, isoamyl nitrite-mediated deamination produced 6-bromo-1,2,4-triazine, which was then used in the next cross-coupling reaction without isolation (Scheme 3.8.1 B). Alternatively, when using boronic acids without nucleophilic substituents, Suzuki coupling was performed after the bromination of 3-amino-1,2,4-triazine. The ensuing isoamyl nitrite mediated deamination delivered a range of triazines in moderate to good yields (Scheme 3.8.1 C). Using this strategy, a triazine amino acid derivative was synthesized and efficiently incorporated into the green fluorescent protein (GFP) after screening a set of seven Methanocaldococcus jannaschii tyrosyl tRNA synthetase (RS)/tRNACUA pairs for permissivity (Scheme 3.8.1 D). A similar 3-iodo-1,2,4-triazine was synthesized by Webb and co-workers from 3-amino-1,2,4-triazine via isopentyl nitrite-mediated diazotization in diiodomethane.[117] The resulting iodotriazine underwent Negishi-type coupling with a Fmoc-alanine zinc reagent, producing triazinylalanine. This was then converted into a fluorescence-conjugated triazine species via a solid phase peptide synthesis strategy. A significant advantage of using 1,2,4-triazines in the IEDDA reaction over other electro deficient dienes is their remarkable stability in the presence of cysteine over extended period of time. In Prescher’s study, the synthesized 1,2,4-triazines were found to be stable in a mixture of CD3CN and D2O in the presence of cysteine. In contrast, under the same conditions, monosubstituted tetrazines either hydrolyzed or reacted with cysteine rapidly. Since monosubstituted 1,2,4-triazines react selectively with TCOs and bicyclononyne (BCN) [117] over other strained alkene, a unique “orthogonal” bioorthogonal strategy can be realized.[118]

Scheme 3.8.1.

Prescher’s 1,2,4-triazines synthesis strategy.

Although monosubstituted aryl-1,2,4-triazines react smoothly with trans-cyclooctenes, there is always a need for faster kinetics in bioorthogonal chemistry. In 2017, Vrabel and collaborators synthesized a variety of mono-and bis-substituted 1,2,4-triazines, and systematically evaluated the rate constants of these 1,2,4-triazines with various trans-cyclooctenes.[119] The mono-substituted 1,2,4-triazines were prepared from commercially available 3-amino 1,2,4-triazines, using Prescher’s coupling-deamination reaction sequence.

For the synthesis of bis-substituted 1,2,4-triazines, an arylglyoxal was treated with hydroxylammonium chloride and hydrazine monohydrate. The resulting oxime was further treated with pyridyl aldehydes or pyridinium aldehydes. The intermediate then underwent a dehydration-cyclization reaction in AcOH at 100 °C, yielding the desired bis-substituted 1,2,4-triazines in moderate to good yields. Interestingly, the oxime intermediates prepared from simple benzaldehyde failed to undergo dehydration and cyclization towards the desired triazine products under the same conditions. In this manner, a new type of methyl pyridinium-substituted 1,2,4-triazine was synthesized (Scheme 3.8.2). These pyridinium triazines demonstrated excellent water solubility, stability, and reactivity towards TCO dienophiles, benefiting from the charged pyridinium functional group. In their study, sTCO was found to be the most reactive among the TCOs when reacting with 1,2,4-triazines.

Scheme 3.8.2.

Vrabel’s bis substituted 1,2,4-triazines synthesis.

Recently, the Vrabel group reported their synthesis of a new series of N-1-alkyl, 3,5-bis substituted 1,2,4-triazinium salts.[120] These salts exhibit significantly enhanced reactivity in IEDDA reactions with cyclooctynes, such as BCN. Being positively charged molecules, the N-1-alkyl,1,2,4-triazinium salts boast excellent water solubility and cell permeability. In terms of the synthesis, a range of functionalized 1,2,4-triazine methyl thioethers were produced and employed as key intermediates.[121] Palladium-catalyzed, copper-mediated Liebeskind-Srogl cross coupling reactions were utilized to introduce the second aromatic group for further derivatization. Additionally, a clean and regioselective alkylation method was developed. By introducing isobutene into a DCM solution of 1,2,4-triazine at low temperature and in the presence of triflic acid, the desired 1,2,4-triazinium salts were synthesized in good to excellent yields (Scheme 3.8.3). This variant of N-1-alkyl,1,2,4-triazinium salt was successfully used in protein labeling and intracellular imaging experiments.

Scheme 3.8.3.

Vrabel’s synthesis of N1-alkyl, 1,2,4-triazinium salt.

Apart from the application of 1,2,4-triazines in protein labeling, in 2017, Wagenknecht and coworkers described the synthesis of a 1,2,4-triazines modified 2’-deoxyuridine triphosphate for primer extension and the subsequent fluorescent labeling of the DNA products using a rhodamine-conjugated BCN.[122] The triazine modification of 2’-deoxyuridine triphosphate begins with the synthesis of the key intermediate, 3-carboxy-1,2,4-triazine. To achieve this, the commercially available starting material, ethyl oxamate, was treated with Lawesson’s regent to give an activated thioamide intermediate. This intermediate was further treated with hydrazine, yielding ethyl amino(hydrazono)acetate after recrystallization. The product underwent a standard triazine formation reaction with glyoxal. The pivotal 3-carboxy-1,2,4-triazine was obtained after hydrolysis with KOH and subsequent acidification. The standard HBTU/HOBt mediated amide formation reaction, followed by a phosphorylation reaction, delivered the desired 1,2,4-triazines modified 2’-deoxyuridine triphosphate upon reverse-phase HPLC purification (Scheme 3.8.4).

Scheme 3.8.4.

The synthesis of 1,2,4-triazines modified 2’-deoxyuridine triphosphate.

Another strategy to enhance the reactivity of 1,2,4-triazines in IEDDA reactions was introduced by Kozhevnikov et al. They synthesized an Ir(III) complex using 5-(pyridine-2-yl)-1,2,4-triazine as a ligand.[123] Unlike the previously utilized 3- or 6- substituted 1,2,4-triazine, a 5-(pyridine2-yl)-1,2,4-triazine was created specifically to accommodate the desired coordination to the Ir(III) center. This design helps prevent potential interference in the Diels-Alder reaction that could arise from undesired coordination (Scheme 3.8.5). These innovative Ir (III) complexes of 1,2,4-triazines were employed as luminogenic bioorthogonal reagents with improved reactivity, notwithstanding the potential toxicity of the metal complexes. In a related vein, coordination of 1,2,4-triazines to Re(I) was reported to facilitate the IEDDA reaction with strained alkynes.[124]

Scheme 3.8.5.

The synthesis of 1,2,4-triazine Ir(III) complexes and their reactions with BCN.

In pursuit of developing a faster 1,2,4-triazine reagent for IEDDA cycloaddition reactions, the Prescher group synthesized and examined the six-member rings with alternative substitutions.[125] Through comprehensive DFT calculations and NMR experiments, they discovered that 5-aryl substituted 1,2,4-triazine reacted smoothly with a sterically hindered dienophile—tetramethylthiacycloheptyne (TMTH). In contrast, the 3- and 6- substituted remained inert (or exhibited minimal reactivity) to the sterically encumbered TMTH. The distinctive and impressive reactivity of 5-aryl substituted 1,2,4-triazine enabled the opportunities for ‘mutual bioorthogonal’ reaction development. In this case, a 5-maleimide conjugate was synthesized and subsequently attached to Nluc using cysteine-maleimide chemistry (Scheme 3.8.6). The resulting triazine-Nluc conjugate was successfully ligated with TMTH as confirmed by mass spectrometry.

Scheme 3.8.6.

The synthesis of 5-aryl substituted 1,2,4-triazine-maleimide reagent.

Fully substituted 1,2,4-triazine have also been reported in bioorthogonal chemistry applications. In 2019, Ma and coworkers described an efficient preparation of CF3-substituted 1,2,4-triazines through a silver-catalyzed [3+3] cycloaddition reaction between trifluorodiazoethane and glycine imines, followed by DDQ oxidation (Scheme 3.8.7).[126] These trisubstituted 1,2,4-triazines were found to react rapidly with trans-cyclooctenes, highlighting their potential application in bioorthogonal chemistry. Notably, the second-order rate constant for the reaction between a 4-nitrophenyl substituted 1,2,4-triazine and sTCO reached 99.24 M−1s−1.

Scheme 3.8.7.

Silver-Catalyzed [3 + 3] Dipolar Cycloaddition of Trifluorodiazoethane and Glycine Imines towards trisubstituted 1,2,4-triazines and IEDDA reaction with sTCO.

3.9. Synthesis of Cyclooctyne Derivatives for Bioorthogonal Chemistry

Alkyne-azide cycloaddtion is of fundamental importance in bioorthogonal chemistry. However, the application of the copper-catalyzed [3+2] cycloaddtion in living system was limited due to the cytotoxic copper (I) species. Strain-promoted alkyne-azide cycloadditions (SPAAC) have emerged as more attractive reactions for in vivo imaging applications. The development of SPAAC involves the synthesis of conjugatable strained cyclic alkyne species. A previous review article[127] summarized the general synthetic approach and reactivities of the strained cycloalkynes. Many of these examples are used as precursors or currently in-use as bioorthogonal reagents. Blomquist and Liu first prepared cyclooctyne by the oxidative decomposition of 1,2-cyclooctanedione dihydrazone.[128] A classical method of constructing the cyclic cyclooctyne moiety commences with cyclic alkene starting materials, followed by bromination and two stages of dehydrohalogenation.[129–131] (Scheme 3.9.1.) Other methods like the oxidation of dihydrazones,[132] thermal decompositions of selenadiazoles[133] or the irradiation of cyclopropenones[134] were also used for cycloalkyne synthesis.

Scheme 3.9.1.

Brandsma’s improved synthesis of cyclooctyne.

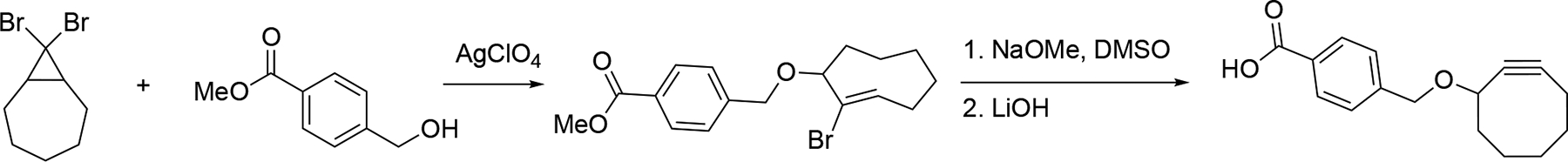

This dehydrohalogenation strategy was recognized and employed by the Bertozzi group in their seminal works on developing a catalyst-free, ring strain promoted [3+2] cycloaddition with cyclooctyne and azides.[135] In brief, a cyclooctyne ring with a conjugatable functional group installed at the propargylic position was prepared from 8,8-dibromobicyclo[5.1.0]octane, similarly as described by Reese and Shaw.[136] After a silver perchlorate triggered electrocyclic ring opening, the formed trans-allylic cation was captured with methyl 4-(hydroxymethyl)-benzoate to afford bromo-trans-cyclooctene. Dehydrohalogenation with sodium methoxide, followed by saponification with LiOH, yielded the versatile cyclooctyne derivative for further conjugation (Scheme 3.9.2). Like vinyl bromide, vinyl triflate also undergoes an elimination reaction to afford the alkyne functional group. Since vinyl triflate moiety can be readily prepared from a ketone, the introduction of an electron withdrawing fluorine atom to the cyclooctyne scaffold can be realized.[137] Alkylation of 2-fluorocyclooctanone with methyl 4-(bromomethyl)benzoate yielded a di-substituted cyclooctenone. Vinyl triflate was formed by treating this cyclooctenone with KHMDS in the presence of Tf2NPh. LDA mediated elimination and LiOH promoted hydrolysis reactions provided a highly functionalized fluoro-cyclooctyne benzoic acid derivative in 58% yield. Biotinylation of the cyclooctyne can be achieved via pentafluorophenyl ester formation, followed by standard amide synthesis (Scheme 3.9.3). In their kinetic studies, the electron-withdrawing fluorine atom on the cyclooctyne provided enhanced reactivity in reacting with azide, compared to its non-fluorinated analogues. The reactivity profile of cyclooctyne can be further enhanced by introducing two fluorine atoms adjacent to the carbon-carbon triple bond on the cyclooctyne backbone.[138–139]

Scheme 3.9.2.

Bertozzi’s synthesis of cyclooctyne.

Scheme 3.9.3.

Bertozzi’s synthesis of mono fluorinated cyclooctyne (MOFO).

The initial synthesis of DIFO started with desymmetric allylation of cis-1,5-cyclooctanediol using allyl bromide. The resulting secondary alcohol was then oxidized to a ketone using pyridinium chlorochromate (PCC). This cyclooctanone derivative was subsequently subjected to an α-fluorination reaction. After two cycles of fluorination using Selectfluor™, the pendant allyl group was oxidized to a carboxylic acid with RuCl3 and NaIO4. Ultimately, DIFO was synthesized by converting the ketone group into vinyl triflate, followed by an elimination reaction using LDA (Scheme 3.9.4).

Scheme 3.9.4.

The initial synthesis of DIFO.

Efforts have been made to improve the overall yield of the DIFO derivatives’ synthesis. In 2008, Bertozzi et al. reported the second-generation of difluorinated cyclooctynes for Copper-Free click chemistry.[139] Starting from 1,3-cyclooctanedione, difluorination proceeded efficiently under basic conditions using Selectfluor™ and cesium carbonate. To install a handle onto the cyclooctyne framework, the authors performed a desymmetric Wittig reaction, producing the mono-ketone product. Hydrogenation of the olefin to form a saturated compound, followed by the standard vinyl triflate formation, yielded the difluorinated cyclooctyne in excellent yield. The subsequent saponification reaction produced the DIFO reagent in 72% yield (Scheme 3.9.5). By changing the phosphonium salt used in the Wittig reaction, different linkers can be installed onto the difluoro cyclooctyne scaffold. Later in 2014, the same group reported a homologation approach for the synthesis of difluorinated cyclooctynes and cyclononynes (DIFN).[140] With this alternative approach, the more synthetically accessible 1,3-cycloheptadione can be employed in the synthesis of DIFO.

Scheme 3.9.5.

The synthesis of second-generation DIFO reagent.

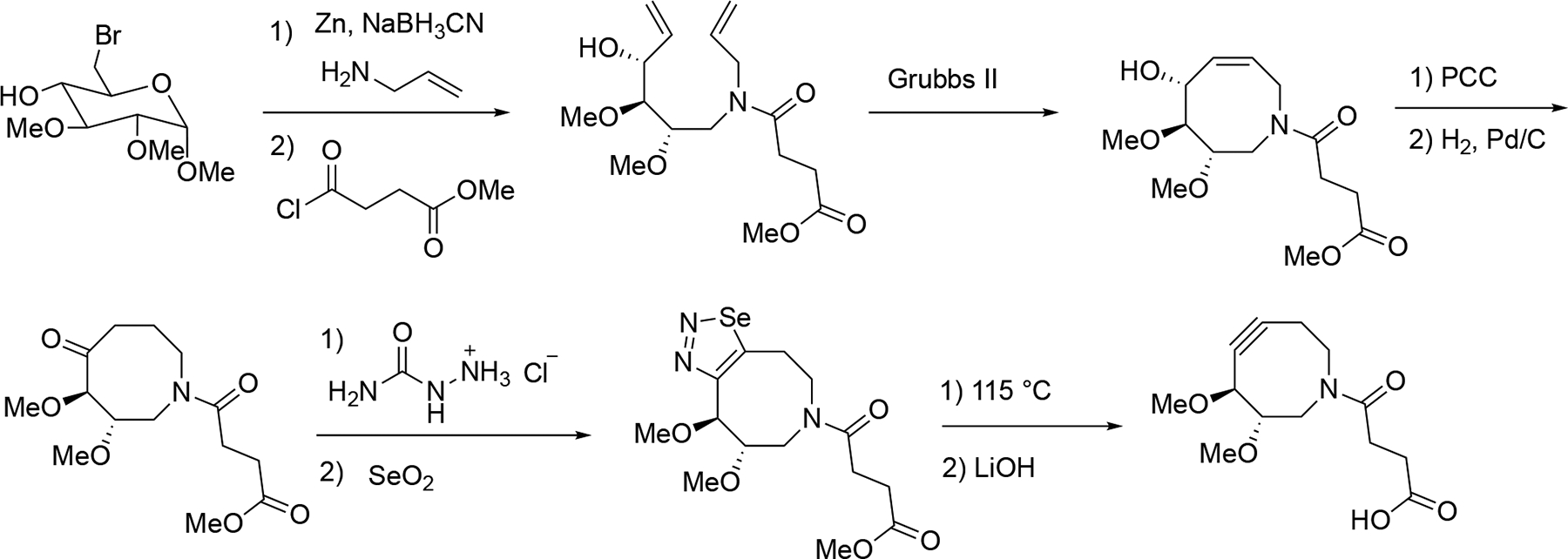

Improving reactivity is crucial, but designing a cyclooctyne with enhanced water solubility holds equal importance. In 2008, the Bertozzi group designed and synthesized a novel heterocyclic cyclooctyne named DIMAC.[141] This compound features a nitrogen atom within the eight-membered ring backbone, intentionally designed to interrupt the hydrophobic surface area. Additionally, the two methoxy groups would enhance its polarity. As shown in (Scheme 3.9.6), the synthesis of DIMAC involves 9 steps from methyl 6-bromoglucopyranoside. First, methyl 6-bromoglucopyranoside was converted to a terminal diene via a zinc reduction/reductive amination reaction, followed by amide formation reaction using methyl succinyl chloride. After that, the acyclic terminal diene underwent ring-closing olefin metathesis using Grubbs II catalyst to give the cyclooctyne intermediate. The allylic alcohol was subsequently oxidized, and the alkene group was reduced through Pd/C catalyzed hydrogenation. While the vinyl triflate approach towards the cyclooctyne was attempted, it resulted in limited success. Therefore, the obtained cyclooctanone was alternatively transformed into a selenadiazole intermediate, which was then treated under thermal decomposition condition to give the cyclooctyne product in moderate yield. The synthesis was finished with hydrolysis using LiOH, delivering DIMAC in 66% yield.

Scheme 3.9.6.

The synthesis of DIMAC.

Augmentation of strain energy through fused aryl (DIBO, DIBAC, BARAC) or cyclopropyl (BCN) rings has been employed as another rate-enhancement strategy in developing superior cyclooctyne bioorthogonal reagents. In 2008, Boons and coworkers introduced the use of 4-dibenzocyclooctynol (DIBO) derivatives as bioorthogonal reagents in cell-surface labeling experiments.[142–143] The authors envisioned that the fused aromatic rings would impose additional ring strain and conjugate with the alkyne, enhancing the reactivity of the cyclooctyne when reacting with azides in the cycloaddition reaction. As expected, the second-order rate constant of DIBO in water/acetonitrile (1:4 v/v) was measured to be 2.3 M−1s−1, approximately three orders of magnitude greater than that of the parent cyclooctyne. The synthesis of DIBO was also proven to be straightforward. Starting from the inexpensive 5H-Dibenzo[a,d]cyclohepten-5-one, the fused cyclooctenone was prepared via a ring expansion reaction using TMSCHN2. The ketone was reduced to alcohol with sodium borohydride. The secondary alcohol was subsequently protected by the tert-butyl dimethyl silyl protecting group prior to dibromination. The dibromide was then treated with LDA in THF to give the cyclooctyne product with a deprotected free hydroxyl group. (Scheme 3.9.7.) Encouraged by this result, in 2012, Boons et al. developed an efficient synthesis for the highly polar sulfated dibenzocyclooctynylamides (S-DIBO), aimed to improve the water solubility of this class of cyclooctyne derivatives.[144] In 2011, the Leeper group developed an efficient synthesis towards a new tetramethoxydibenzocyclooctyne (TMDIBO), which was successfully used in selective labeling of cell surface azidoglycans.[145] TMDIBO can be stored at room temperature for 1.5 years without detectable decomposition. Meanwhile, this new cyclooctyne reacts with azides at rates comparable to those of other commonly used cyclooctynes.

Scheme 3.9.7.

The synthesis of a DIBO derivative.

Inspired by the DIBO synthesis developed by Boons et al. and the DIMAC synthesis by Bertozzi et al, van Delft et al. reported a facile synthesis of aza-dibenzocyclooctyne (DIBAC) and its derivatives for application in the quantitative PEGylation of proteins.[146] In their synthesis (Scheme 3.9.8. A), a diaryl acetylene intermediate was prepared via Sonogashira cross-coupling reaction. Boc-protection followed by partial hydrogenation gave the cis alkene in excellent yields. Dess–Martin oxidation was then employed to convert the primary alcohol to an aldehyde, which was used as a precursor for reductive amination after the N-Boc deprotection. With the key aza-cyclooctene intermediate in hand, the nitrogen atom was first protected and then standard dibromination followed by elimination delivered the desired cyclooctyne in good yields. With a methyl ester functional group pre-installed on the aza-cyclooctyne ring, the hydrolysis reaction using LiOH yielded the functionalizable strained aza-cyclooctyne carboxylic acid probe. In the same year, Popik and co-workers reported an alternative synthesis route towards the DIBAC, wherein an oxime formation reaction and Beckman rearrangement were key reactions[147] (Scheme 3.9.8. B) Moreover, in 2019, a multigram synthesis procedure of DIBAC without chromatography was reported.[148]

Scheme 3.9.8.

(A) van Delft’s synthesis of DIBAC derivative. (B) Popik’s synthesis of DIBAC derivative (PPA = polyphosphoric acid).

In 2010, the Bertozzi group described the synthesis of the biarylazacyclooctynone (BARAC).[149] This unique cyclooctyne has an amide group within its eight-membered ring backbone and exhibited exceptional reaction kinetics. In this study, a modular and scalable synthesis towards BARAC was demonstrated. As shown in Scheme 3.9.9., the Fisher indole synthesis delivered a commercially available indole derivative. The indole nitrogen was then protected with an allyl group, which would serve as a linker for further conjugation chemistry. A TMS group was introduced after deprotonation with n-BuLi. This highly functionalized indole derivative was then oxidized with mCPBA, followed by a cascade ring-opening reaction, leading to the desired cyclic keto-amide intermediate, which was unstable upon silica-gel purification. It is worth mentioning that the terminal alkene remained intact under the reaction condition. This intermediate was treated with KHMDS and Tf2O to give the enol triflate. Subsequently, the terminal alkene was coupled with nitrile oxide, establishing a linker for conjugation to a probe molecule. In the end, a CsF induced elimination reaction introduced the strained alkyne group in 30 min at room temperature. Although Adronov et al. attempted to introduce the alkyne moiety via dibromination/elimination, a low yield (<10%) of BARAC was observed.[150] A Similar fluoride-mediated elimination of a silyl enol triflate precursor for the synthesis of strained cyclooctynes was also successfully employed in the preparation of DIFBO.[151] DIFBO is an monoaryl-fused cyclooctyne derivative with two fluorine atoms adjacent to the alkyne. While the Bertozzi team successfully synthesize this compound, they could not isolate DIFBO in its dried form as this particular cyclooctyne prone to decomposition via trimerization, resulting in its limited application in bioorthogonal chemistry.

Scheme 3.9.9.

Bertozzi’s synthesis of BARAC.

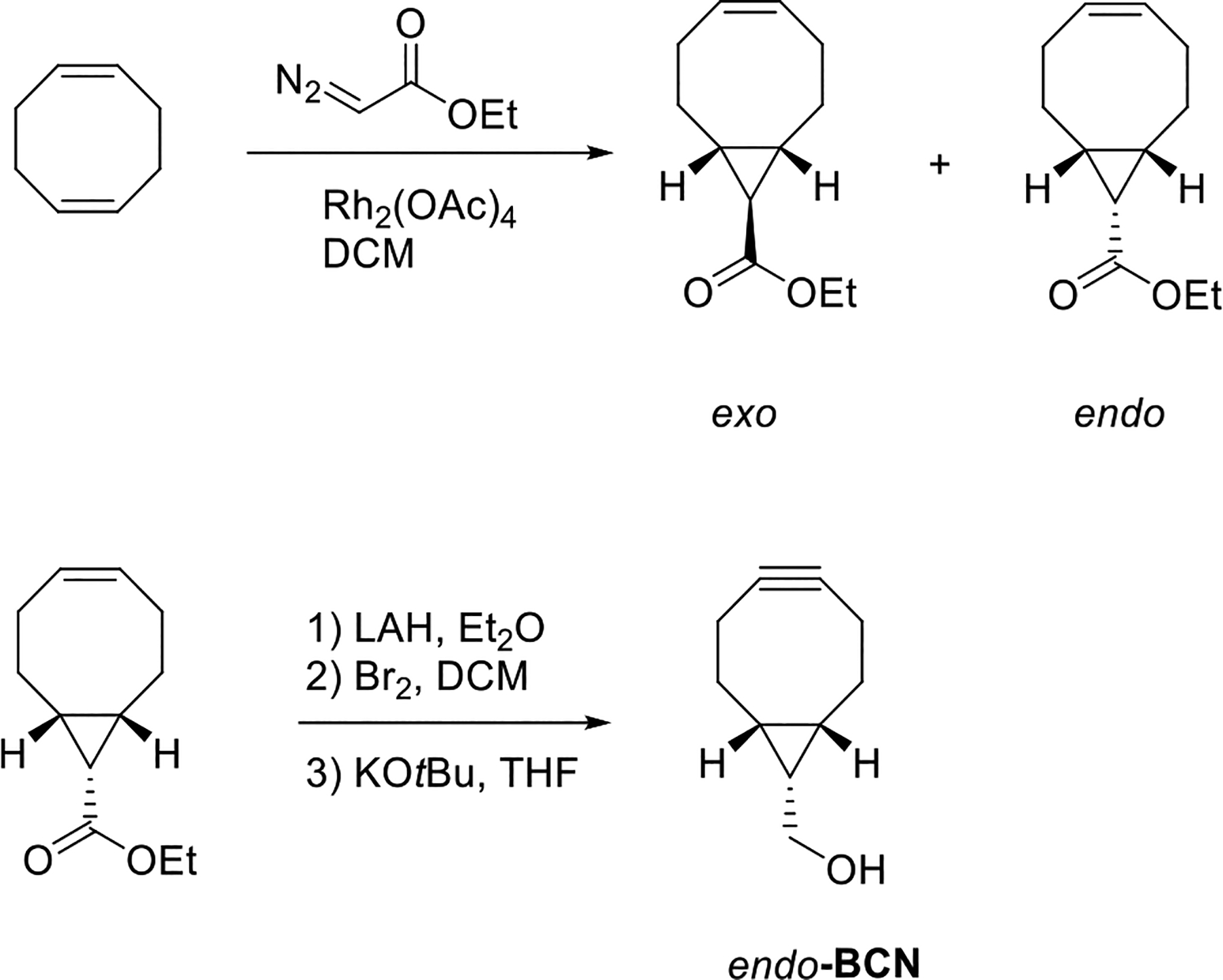

The cyclooctyne toolbox was further expanded with the introduction of bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne (BCN), which was first reported by van Delft and coworkers in 2010.[152] BCN is a cyclooctyne derivative fused with a cyclopropane. The parent bicyclo[6.1.0]nonyne was first reported in 1987 by Meier,[153] who also described the oxo-analog of BCN.[154] In Meier’s study, thermal decomposition of selenadiazole was employed as the method for the construction of the alkyne bond. In contrast, in van Delft’s work, dibromination followed by elimination reaction was used for the cyclooctyne formation. Compared to other cyclooctyne derivatives, the synthesis of a conjugatable BCN requires only 4 steps from inexpensive commercially available starting material. (Scheme 3.9.10.). A challenge involved in the BCN synthesis is the separation of two diastereomers after the cyclopropanation reaction. To overcome this hurdle, our group described a procedure that allows a mixture of exo and endo isomers to hydrolysis and epimerize, producing a BCN precursor as a single exo diastereomer.[155] In addition to the BCN derivatives shown in Scheme 3.9.10., other more functionalized BCN analogues were also synthesized.[156–157]

Scheme 3.9.10.

BCN synthesis.

Apart from aryl and cyclopropyl-fused cyclooctynes, those fused with heterocycles have also been explored. In 2015, a pyrrole fused cyclooctyne (PYRROC) was designed and synthesized to circumvent isomer formation in SPAAC.[158] To synthesize the cyclooctyne with an attached pyrrole group, 1,4-cyclooctadiene was treated with silver nitrite and TEMPO to yield the nitro-cyclooctadiene. This intermediate was subjected to the Barton–Zard reaction, leading to the formation of the key pyrrolocyclooctene. Hydrolysis, decarboxylation, and N-Boc protection afforded the symmetrical pyrrolocyclooctene in good yield. The pyrrole group was then converted into a diester functionalized pyrrole via dilithiation followed by the addition of methyl chloroformate. Bromination and deprotection gave the dibromide precursor of the cyclooctyne. The nitrogen atom was then protected again via an alkylation reaction. A two-stage elimination process afforded the desired alkyne moiety. In the last step, the TBDMS protecting group was removed using TBAF to give PYRROC in 62% yield (Scheme 3.9.11.). Later in 2019, the same research group unveiled a new type of pyrrolocyclooctyne reagent for isomer-free SPAAC with improved reactivity.[159]

Scheme 3.9.11.

PYRROC synthesis.

Diarylcyclopropenone has been widely used as another intriguing precursor for the preparation of cyclooctynes. The preparation of the first diphenylcyclopropenone was reported independently in 1959 by Breslow[160] and Vol’pin.[161] Popik has rigorously studied the synthesis, properties, and photochemistry of a series of cyclopropenones.[162] In his study, it was found that diaryl-substituted cyclopropenones can be efficiently activated with a 350 nm or longer wavelength light and underwent a decarbonylation reaction in situ generating alkyne structures in nearly quantitative yields. In 2009, this photochemical synthesis of alkynes was employed for the in situ generation of a PEGylated DIBO analogue.[134] This phototriggered click strategy for SPAAC started from the synthesis of cyclopropenone as a masked precursor of cyclooctyne. As shown in Scheme 3.9.12., a cyclopropenone fused cyclooctane was prepared by treating 3,3′-bisbutoxybibenzyl with tetrachlorocyclopropene in the presence of aluminum chloride, followed by the hydrolysis of dichlorocyclopropene. This intermediate was coupled with diethylene glycol acetate through the Mitsunobu reaction and the carbonyl group was then protected with neopentyl glycol. The acetyl ester was subsequently hydrolyzed to a primary alcohol, which was later activated and conjugated with a biotin-amine reagent. Finally, the protecting group of the carbonyl group was removed with Amberyst-15 to restore the cyclopropenone moiety. In the UV spectra study, irradiation of the cyclopropenone-biotin conjugates with 350 nm light led to the efficient decarbonylation of the starting material, along with the quantitative formation of the corresponding cyclooctyne species, which can be trapped by azides. The reagent was successfully employed in labeling living cells expressing glycoproteins containing N-azidoacetyl-sialic acid. This innovative photo-triggered copper-free click chemistry offers a new opportunity to label living organisms in a spatially and temporally controlled manner. In the following years, the photochemical generations of other cyclooctyne derivatives were explored and reported by Popik and other researchers.[144, 163–165]

Scheme 3.9.12.

Synthesis of cyclopropenone precursor for photochemical synthesis of cyclooctyne.

So far, most synthesis routes towards cyclooctynes derivatives have preferred a late-stage formation of the strained alkyne triple bond. Indeed, carrying a strained alkyne group through the entire synthesis would be challenging. Moreover, incorporation of an existing alkyne group into the eight-membered ring through SN2 ring formation reaction has been uncommonly used because building up ring strain during the ring formation is not favored. One solution is to mask the pre-existing alkyne group by forming cobalt complexes. After the SN2 ring formation reaction, the masked alkyne group can be restored under mild deprotection condition. For instance, the Bräse group synthesized cobalt complexes of 1,4-dithia-6-cyclooctyne and 1-thia-4-oxa-6-cyclooctyne from 1,4-but-2-ynediol by following a previously reported procedure[166] The obtained cobalt complexes were decomplexed under mild condition to give the corresponding heterocyclooctynes in 26% and 13% yields (over two steps) respectively.[167] (Scheme 3.9.13). Recently, a similar alkyne masking strategy was successfully employed in Hosoya’s synthesis of DIBO and DIBAC derivatives.[168] (Scheme 3.9.14)

Scheme 3.9.13.

Synthesis of heterocyclooctynes via Nicholas reaction.

Scheme 3.9.14.

DIBAC synthesis via cobalt complexes.

3.10. Synthesis of Heterocycloheptynes for Bioorthogonal Chemistry

It is known that the stability and reactivity of medium ring cycloalkynes are significantly influenced by their ring size. For instance, compared to cyclooctynes, all-carbon cycloheptynes are unstable and cannot be isolated at room temperature. On the other hand, cyclononynes are stable yet exhibit reduced reactivity with azides.[169] By substituting a carbon atom in the cycloalkyne backbone with a larger atom, such as sulfur, the ring size is effectively increased (although more conservatively than a simple expansion of ring size). This replacement serves to alleviate some of the ring strain, enhancing the overall stability of the strained molecule.

By synthesizing the sulfur-containing analog of OCT (thiaOCT), the Bertozzi lab measured the second-order rate constant for the cycloaddition reaction of thiaOCT and benzyl azide in CD3CN. They observed that the rate constant (3.2×10−4 M−1s−1) was an order of magnitude lower than that of the all-carbon OCT. Similar rate discrepancy was also noted between thiaDIFBO (a sulfur incorporated version of DIFBO) and its parent molecule, DIFBO. Encouraged by these results, the Bertozzi group envisioned that replacing a carbon atom with a sulfur atom in the cycloheptyne backbone might stabilize the otherwise unstable cycloheptyne, which had not yet been used in bioorthogonal chemistry up to that time.

In the 1970s, Krebs and Kimling first reported the discovery of a stable seven-membered heterocycloalkyne — 3,3,6,6-tetramethylthiacycloheptyne (TMTH). They demonstrated TMTH reacts rapidly with phenyl azide to yield cycloaddition products, though no rate constant was reported.[170–171] Bertozzi and coworkers synthesized TMTH (Scheme 3.10.1) in a similar fashion and investigated the kinetics of this reagent with benzyl azide. The second order rated constant of TMTH and benzyl azide in CD3CN was measured to be 4.0±0.4 M−1s−1, outpacing cyclooctyne species. This TMTH was successfully used in protein labeling studies with high selectivity.

Scheme 3.10.1.

The Synthesis of TMTH.

A derivative of TMTH, bearing a functionalizable handle, was successfully synthesized by Baati and Wagner.[172] This handle was installed through a mild alkylation reaction using a benzyl bromide derivative in the presence of LiOTf. (Scheme 3.10.2.) The electron-deficient benzyl bromide derivative facilitated the production of the desired alkylation product in good yield. The resulting 4,5-didehydro-3,3,6,6-tetramethyl-2,3,6,7-tetrahydrothiepinium (TMTI) could be purified via conventional silica gel column chromatography, exhibiting excellent stability. As a triflate salt, this novel thiacycloheptyne compound demonstrated excellent aqueous solubility, and was suitable for use in biological media.

Scheme 3.10.2.

The Synthesis of 4,5-didehydro-3,3,6,6-tetramethyl-2,3,6,7-tetrahydrothiepinium (TMTI) and its reaction with benzyl azide.

In 2020, Liskamp et al. reported the development of TMTH-SulfoxImine (TMTHSI) for use in strain-promoted azide-alkyne cycloaddition reactions.[173] TMTHSI was ingeniously designed to feature a handle on the incorporated sulfur atom, which facilitates further introduction of linker moieties or other molecules of interest. Like TMTH, the synthesis of TMTHSI begins with the preparation of a 7-membered bishydrazone using modified conditions (Scheme 3.10.3). The desired 7-member ring was formed via acyloin condensation. Swern oxidation then delivered the diketone in 70% yield. Following this, the functionalization of the bivalent sulfur and the construction of the carbon-carbon triple bond can be furnished simultaneously with PIDA and ammonium acetate. This 7-member strained cycloheptyne is highly attractive given its compact size, reactivity in cycloaddition reactions with azides, and improved aqueous solubility, making it an attractive bioorthogonal reagent.

Scheme 3.10.3.

(A) The Synthesis of TMTHSI. (B) Functionalization of TMTHSI.

To further tune the reactivity and stability of cycloheptynes, incorporation of other large heteroatoms was attempted. In 2013, the Bertozzi lab reported the preparation of a selenium containing dibenzoselenacycloheptyne reagent.[174] First, a commercially available aryl bromide was treated with n-BuLi for lithium-halogen exchange. The reaction mixture was then treated with selenium diethyldithiocarbamate (Se(dtc)2) to yield the diaryl selenide product. The diaryl selenide was subjected to a Friedel-Craft reaction with tetrachlorocyclopropene. The in situ hydrolysis of the dichlorocycloproene provided the corresponding cyclopropenone, a precursor for dibenzoselenacycloheptyne. Dibenzoselenacycloheptyne was then generated upon irradiation using a medium pressure Hg lamp. (Scheme 3.10.4) Unfortunately, attempts to isolate the desired dibenzoselenacycloheptyne were unsuccessful due to its inherent instability. Indeed, the in situ formed dibenzoselenacycloheptyne was found to be able to abstract hydrogen atoms from solvents like toluene and THF via a diradical mechanism. Despite its instability, the selenacycloheptyne can be trapped with benzyl azide and isolated in the form of a triazole cycloadduct.

Scheme 3.10.4.

The Synthesis and trap of dibenzoselenacycloheptyne.

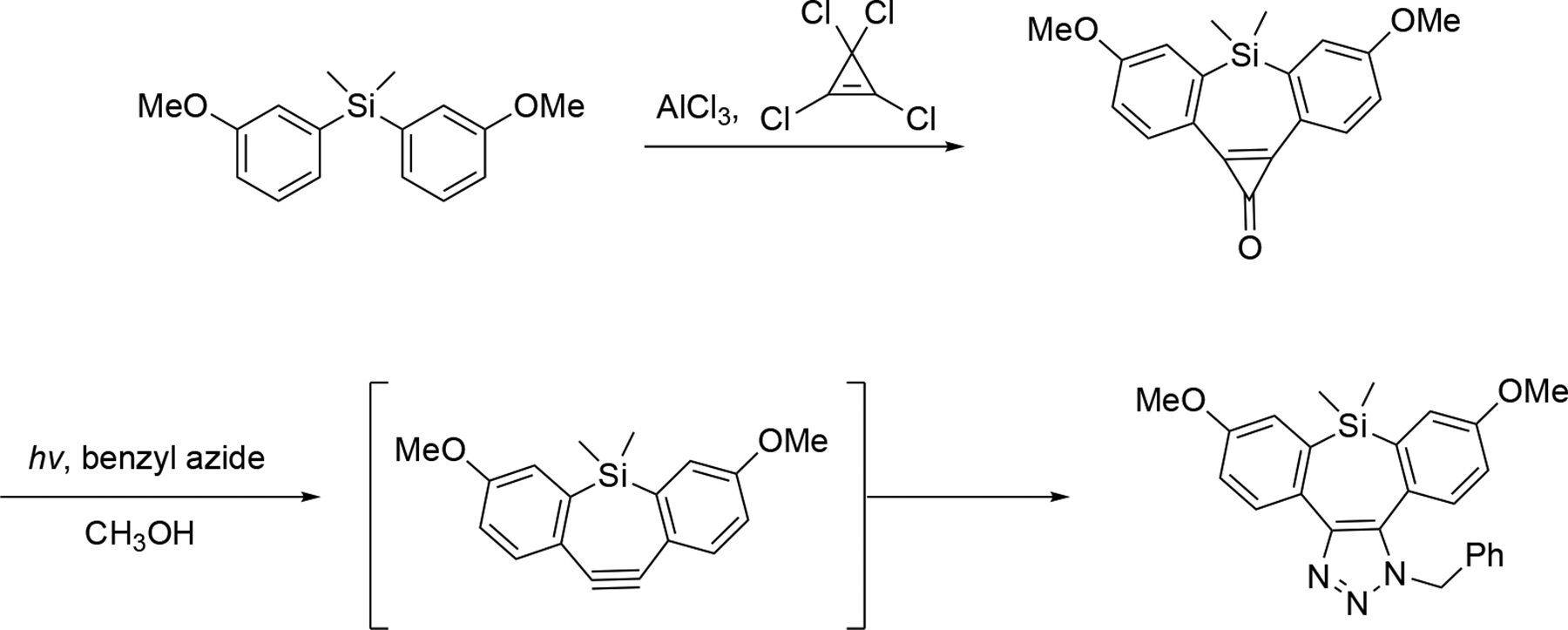

A silicon containing analogue of dibenzoselenacycloheptyne was also reported. It was generated from the corresponding cyclopropenone and underwent rapid, in situ Cu-free click reactions with azides and 1,2,4,5-tetrazines.[175] The key cyclopropenone precursor was shown to be stable in the dark in 1:1 MeOH:water, and could be photochemically converted into the benzylazide adduct in 80% yield. The cyclopropenone was synthesized via a Friedel-Craft reaction using tetrachlorocyclopropene and diaryl silane followed by in situ hydrolysis (Scheme 3.10.5).

Scheme 3.10.5.

The synthesis and trap of silacycloheptyne.

3.11. Synthesis of trans-Cycloalkenes

3.11.1. Non-photochemical syntheses of trans-Cyclooctenes

trans-Cyclooctene was first prepared in 1950 by Ziegler and Wilms as a mixture with cis-cyclooctene via Hoffman elimination of trimethylcyclooctylammonium iodide.[176] In 1953, Cope, Pike and Spencer first prepared trans-cyclooctene in pure form (Scheme 3.11.1.). trans-Cyclooctene was separated from cis-cyclooctene via complexation to give a water-soluble trans-cyclooctene•AgNO3 complex, which was subsequently treated with aq. NH4OH to provide the pure trans-alkene.[177] This procedure has been carried out on large scale.[178]

Scheme 3.11.1.

Synthesis of pure trans-Cyclooctene by Cope, Pike and Spencer.

A number of stereospecific methods for preparing trans-cyclooctene from cis-cyclooctene have also been described.[179–182] In general, these procedures start with cis-cyclooctene and invert olefin stereochemistry via a multistep sequence involving olefin oxidation, elaboration, and stereospecific elimination. Early approaches described the syn-elimination of compounds derived from anti-1,2-dihydroxy-cyclooctane, including the Corey-Winter elimination of the thionocarbonate[180] (Scheme 3.11.2 A) and lithiation/elimination of the benzaldehyde acetal (Scheme 3.11.2 B).[179] Both Vedejs[181] and Whitham[183] described methods to synthesized trans-cyclooctene via a sequence of lithium diphenylphosphide addition to cyclohexene oxide followed by stereospecific elimination (Scheme 3.11.2 C,D). Coates described that Cr-catalyzed carbonylation of cyclohexene oxide takes place to give the bicyclic trans-lactone in high yield.[182] It was further reported that careful thermolysis yielded the trans-alkene through loss of CO2, but yield was unspecified.

Scheme 3.11.2.

Stereospecific syntheses trans-cyclooctene.

trans-Cyclooctenes bearing allylic substituents have been prepared by the stereospecific ring opening reactions of 8-halobicyclo[5.1.0]octane derivatives.[184–187] Whitham demonstrated that exo-8-bromobicyclo[5,1,0]octane undergoes stereospecific solvolysis in aqueous dioxane to give diastereomers of trans-cyclooct-2-en-1-ol (Scheme 3.11.3 A). Reese and Shaw studied analogous Ag-mediated rearrangements of 8-halobicyclo[5.1.0]octanes, exemplified by the rearrangement of 8,8-dibromobicyclo[5,1,0]octane to give diastereomers of 2-bromo-trans-cyclooct-2-en-1-ol.[188] More recent studies by Schultz and coworkers showed that t-BuLi provided eq-trans-cyclooct-2-en-1-ol as the major diasteromer (Scheme 3.11.3 B), which was used to construct the equatorial diastereomer of the genetically encodable TCO*-E amino acid which demonstrates high stability and reactivity in live cell protein labeling experiments.[189] The axial diastereomer was synthesized using flow photochemistry as the key step.[189–190]

Scheme 3.11.3.

Stereospecific ring expansion to trans-cyclooctenes.

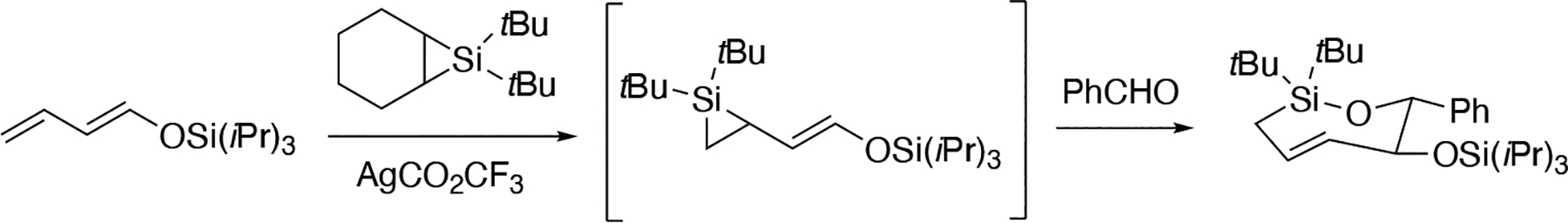

Additional approaches to trans-cyclooctenes include the work of Hsung, who showed that trans-cycloalkenes can also be prepared by 4-π electrocyclic ring opening.[191–193] Woerpel[194–202] and Tomooka[203–208] have described a number of methods for preparing oxasila-trans-cycloalkenes (e.g. Scheme 3.11.4).

Scheme 3.11.4.

Synthesis of trans-dioxasilacyclooctenes.

3.11.2. Photoisomerization Syntheses of trans-Cycloalkenes

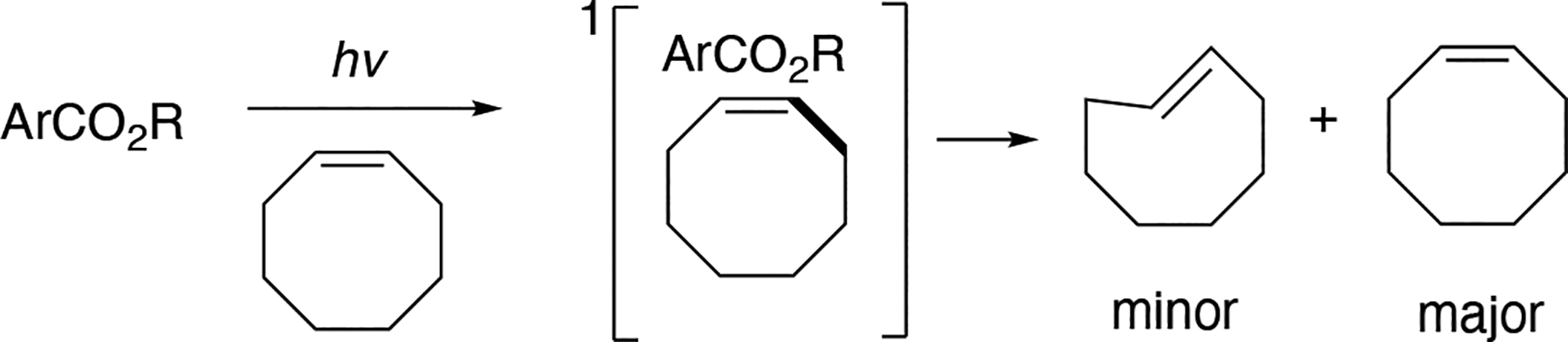

The singlet-sensitized photoisomerization of cis-cyclooctene was first described by Inoue.[209–219] This photocatalytic reaction is proposed to proceed via diastereomeric “twisted singlet”[217] exciplexes, which subsequently partition into the corresponding trans-cyclooctene as a minor product and the return of cis-cyclooctene starting material. Remarkable studies by Inoue have demonstrated useful levels of enantioselectivity in photoisomerization of cyclooctene, cycloheptene, and 1,3-cyclooctadiene to their trans-isomers using chiral aromatic esters as sensitizers with irradiation at 254 nm.[209–218] (Scheme 3.11.5)

Scheme 3.11.5.

Singlet-sensitized photoisomerization based on chiral exciplex formation.

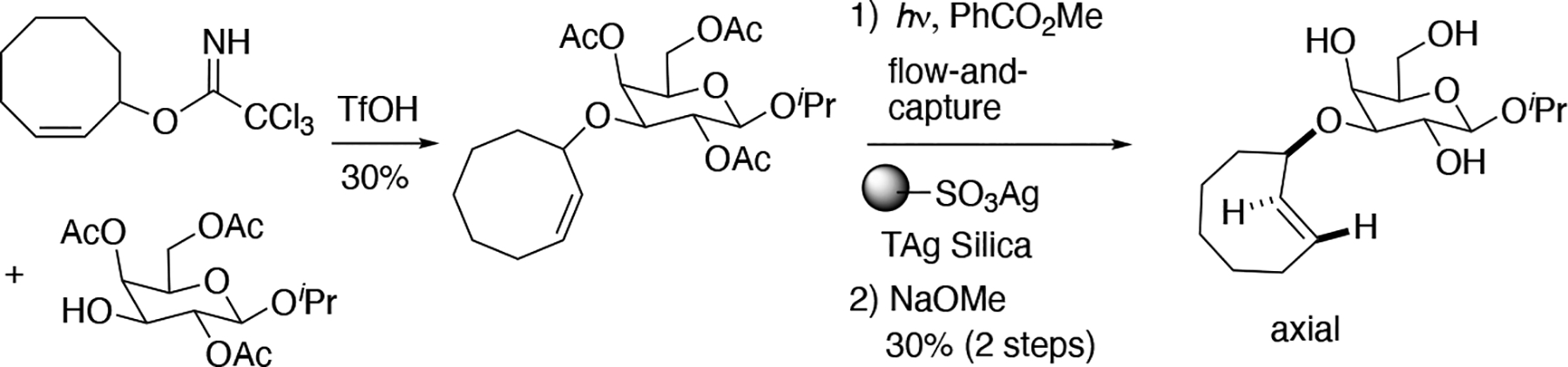

3.11.3. ‘Flow-and-capture’ Photochemical Syntheses of trans-Cyclooctenes

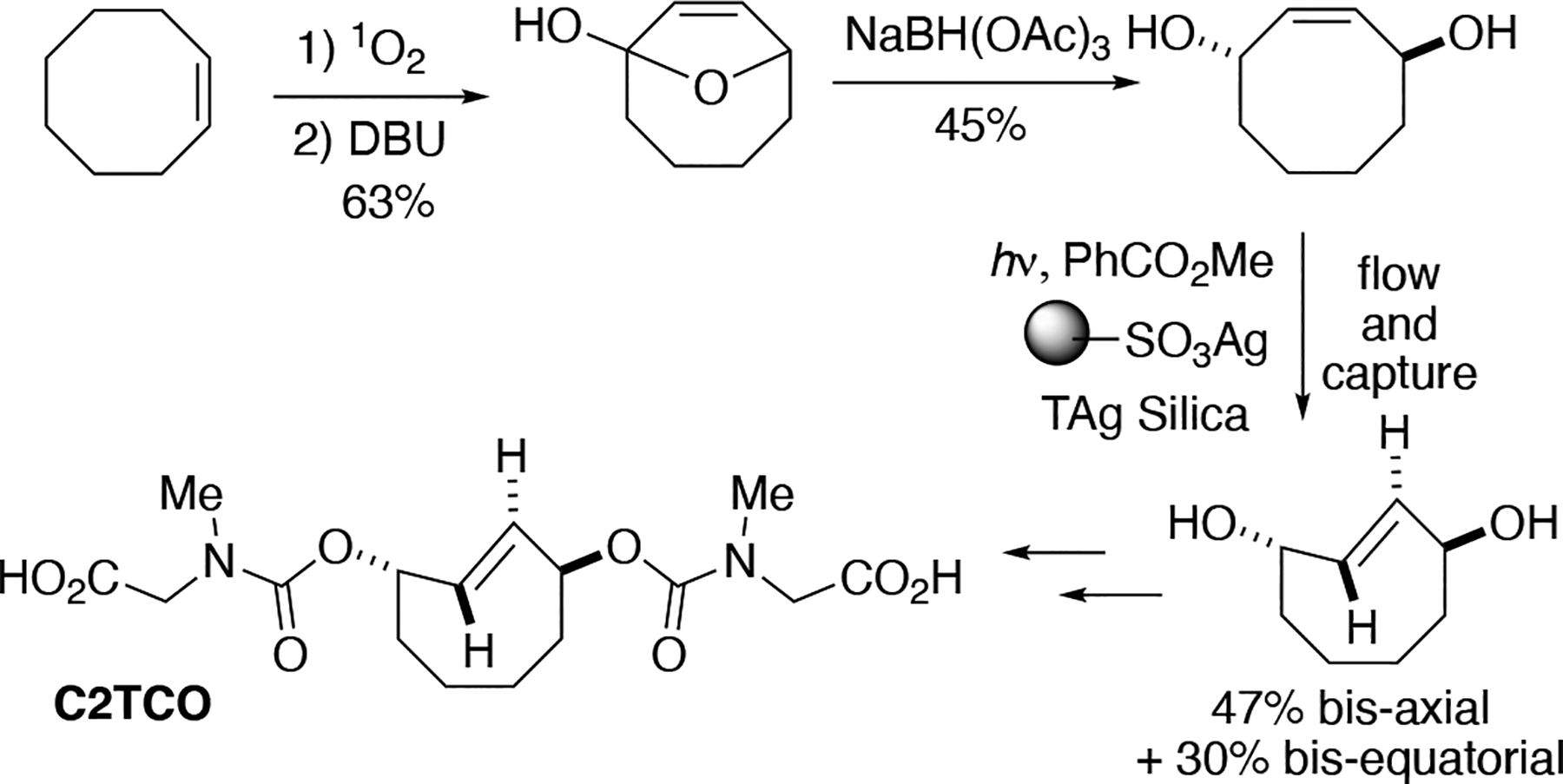

The direct photoisomerization of trans-cyclooctenes is constrained by low yields and by the photodegradation of the trans-cyclooctene upon prolonged irradiation. Classic studies on photoprotonation of cycloalkenes had shown that photochemical equilibria could be driven by selective reaction of the trans-isomer.[220–222] Driven by strain relief, trans-cyclooctenes form complexes with a number of metals.[178, 223] Unlike cis-cyclooctene, trans-cyclooctene forms strong, stable complexes with Ag(I) due to the greater relief of strain energy and minimal cost in distortion energy upon complex formation. [178, 223] To improve trans-cyclooctene synthesis, our group developed a closed-loop flow reactor that drives the formation of trans-cyclooctene product through selective complexation of Ag(I) by the trans-isomer (Fig 3.11.1 A).[190] A quartz reaction flask charged with a solution of a cis-cyclooctene derivative and singlet sensitizer (typically methyl benzoate) is irradiated at 254 nm with continual flow through a cartridge containing AgNO3 adsorbed on silica gel.[224] The AgNO3•silica selectively retains the trans-cyclooctene product, whereas the cis-isomer elutes back to the reaction flask and is again photoisomerized before being recirculated through the column. After the reaction is complete, trans-cyclooctene is released from the AgNO3 by stirring silica with NH4OH or NaCl, providing access to multigram quantities of trans-cyclooctene products. As an alternative to AgNO3, Ag(I) immobilized on tosic silica gel (Tag silica) can be especially beneficial for polar trans-cyclooctene substrates.[225] Examples of trans-cyclooctenes that have been prepared by flow photoisomerization are given in Figure 3.11.1 B. [190, 225–226] When there are stereocenters in the backbone, photoisomerization procedures produce equatorial and axial diastereomers with modest preference for the equatorial diastereomer.[190, 224] The conformational constraint of a fused trans-dioxolane increase diastereoselectivity to 11:1, as the major diastereomer in this case must adopt a high energy chair conformation.[190, 226]

Figure 3.11.1.

(A) Schematic of Apparatus for trans-Cyclooctene Synthesis. (B) Examples of trans-cyclooctene derivatives that have been prepared using flow photoisomerization.

Flow photoisomerization has been used by numerous groups to synthesize trans-cyclooctene derivatives, with uses in radiochemistry, cellular imaging, drug delivery, and materials research.[13–14, 28, 73, 104, 119, 189, 200, 227–254] A number of modifications to the flow procedure have also been described. Several groups have developed processes where the flow photoisomerization is mimicked by intermittently pausing the irradiation, trapping the trans-cyclooctene by filtering through AgNO3 on silica, and then resubmitting the filtrate to photoisomerization (254 nm). [255–256] Compared to flow chemistry protocols, these processes are more scale-limited and have poorer yields. Mikula developed a modification of the flow system that utilized a quartz tube in conjunction with a UV light.[257] In this configuration, the reaction solution was flowed from a reservior flask through a quartz tube in which the irradiation (254 nm) took place was continuously pumped with the reaction solution, which was primarily contained in a reservoir flask. This configuration made the reaction scalable without incurring the cost of buying various quartz flasks for various reaction scales. A microflow system for cyclooctene photoisomerization has been reported that utilizes exchangeable beds of AgNO3-impregnated silica and two microreactors coiled around a UV lamp.[258] Schultz and coworkers have described a large-scale photoreactor that has been used to carry out photoisomerizations on 45 gram scale.230

Reactors that utilize UV-permeable FEP tubing (fluorinated ethylene propylene) have been described by several groups.[259–261] Our group showed that the use of FEP tubing in conjunction with in-line cooling was found to be essential for trans-cycloheptene synthesis.[260] Biogen used FEP tubing in conjunction with an inexpensive germicidal lamp to synthesize trans-cyclooctenes.[259] In an important development, a liquid-liquid extraction method was developed by Rutjes.[261] Their device consists of a UV light and a continuously flowing heptane solution of cis-cyclooctene over an aqueous AgNO3 solution. The organic phase flows through UV-permeable FEP tubing (fluorinated ethylene propylene) wrapped around a UV lamp (254 nm) and into an AgNO3 aqueous solution, which captures the trans-, whereas cis-cyclooctene is released back into the organic phase. In continuous flow, this method produces up to 2.2 g/h of TCO and was employed on several of the commonly utilized trans-cyclooctenes. A consideration for the method is that polar functional groups (e.g. alcohol or acid groups) require protecting groups to make them more hydrophobic.

3.11.4. trans-Cyclooctenes in Bioorthogonal Chemistry

trans-Cyclooctenes have many uses in bioorthogonal chemistry due to their incredibly rapid reaction rates with tetrazines. Often, derivatives of 5-hydroxy-trans-cyclooctene are used for bioorthogonal chemistry applications. 5-Hydroxy-cis-cyclooctene, the photoisomerization precursor, is commercially available or can be prepared from cyclooctadiene via a sequence of epoxidation and LiAlH4 reduction.[190] The equatorial diastereomer is the major product of photoisomerization reactions, and is produced on relatively large scale using flow chemistry.[190] The minor, axial diasteromer of 5-hydroxy-trans-cyclooctene (ax-5-OH-TCO) has a second order rate constant of 8.0 × 104 M−1s−1 at 25 °C with an amido-substituted dipyridyltetrazine in water, which is 4 times faster than the equatorial diastereomer (eq-5-OH-TCO) (Fig 3.11.2). Robillard has shown that carbamate derivatives of 5-hydroxy-trans-cyclooctene exhibit an even greater rate differential, and derivatives of ax-5-OH-TCO have been developed for use in pretargeted nuclear medicine.[254] Both diastereomers of 5-hydroxy-trans-cyclooctene display good stability toward isomerization and have been applied as bioorthogonal reporters in situations where cellular or in vivo stability over an extended period of time is required. The stability properties of trans-cyclooctenes have been summarized.[262]

Figure 3.11.2.

Most commonly utilized trans-cyclooctenes in bioorthogonal chemistry applications are typically produced by flow photoisomerization.

Non-canonical amino acids bearing trans-cyclooctenes have become important tools for expanding the genetic code and subsequently labelling and visualizing proteins within living cells and organisms.[189, 241, 252, 263–264] This has led to the design and synthesis of a range of non-canonical amino acids including those shown in Fig 3.11.3. Flow- and-capture photoisomerization factors as a key step in each synthesis with the exception of TCO*-E (Scheme 3.11.3. above), which is prepared by stereospecific ring expansion as discussed above.

Figure 3.11.3.

Non-canonical amino acids bearing trans-cyclooctenes

These studies have produced a number of interesting synthetic observations. Schultz and Bergamini have described an aminomethyl substituted ‘amTCO’ derivative which can be prepared easily. Interestingly, a phthalimido protecting group served also as the sensitizer for the flow-and-capture photoisomerization reaction, eliminating the need for added benzoate sensitizer.[264] amTCO was prepared as an axial/equatorial mixture that was not separated. (Scheme 3.11.6)

Scheme 3.11.6.

amTCO synthesis.

3.11.5. Conformationally Constrained TCOs

Even faster biorthogonal chemistry can be enabled with conformationally strained trans-cyclooctene dienophiles (Figure 3.11.4).[265–266] Our group used computation to design the first members of this series, dubbed ‘s-TCO’ and ‘d-TCO’. These compounds adopt a strained half-chair conformation that introduces additional olefinic strain to the trans-cyclooctene scaffold. Consequently, cycloadditions with tetrazines can be more than 2 orders of magnitude faster than analogous reactions of eq-5-OH-TCO. With an amido-substituted dipyridyltetrazine in water, s-TCO-OH reacts with a second order rate constant of 3.3 × 106 M−1s−1. The carboxylic acid analog, s-TCO-CO2H is equally easy to access and displays similarly high reactivity. With the same tetrazine, d-TCO reacts with a rate of 3.7 × 105 M−1s−1.[266] The more recently described aza-TCO also displays rapid reactivity that is intermediate between s-TCO and d-TCO.[234] aza-TCO has been utilized in the formation of fluorescent products in tetrazine ligations that do not require attachment of an extra fluorophore moiety.

Figure 3.11.4.

Conformationally strained trans-cyclooctenes display the fastest rates in bioothogonal reactions with tetrazines.