Abstract

Aim

To synthesize the evidence considering effects of pre-operative patient expectations on the post-operative outcomes in patients with total shoulder arthroplasty.

Methods

PubMed, Web of Science and Cochrane were searched for relevant studies. Studies before 2000 were excluded. Studies examining effects of pre-operative patient expectations on post-operative outcome in adults who had undergone total shoulder arthroplasty were included if at least one of the following treatment outcomes should have been measured: shoulder function, range of motion, shoulder pain, activities of daily living, muscle strength, patient satisfaction, or quality of life. After screening 875 studies four studies were included. Relevant data was extracted in a standardized way. Quality assessment was performed through QUIPS and EBRO methods. Both were performed by two independent reviewers.

Results

All 4 studies had a high risk of bias and level of evidence B. Moderate evidence was found regarding the absence of an association between greater pre-operative patient expectations and numerous outcome measures. All other associations yielded conflicting or preliminary evidence.

Discussion

Informing patients about what can be expected can be of great importance. Evidence lacking. To confirm or reject the findings of this systematic review, future research should focus on high-quality research with validated research protocols.

Keywords: Arthroplasty, shoulder, replacement, expectations, physical therapy

Introduction

Shoulder arthroplasty (SA) is a well-known and often performed surgical procedure.1,2 The number of SA performed is increasing rapidly1–5 and the demand is expected to rise to a 755% increase by 2030. 6 Despite the overall good outcomes after SA procedures, several patients (up to 25%) still are dissatisfied. 7 Swarup et al., systematically summarized different factors that were associated with post-operative satisfaction in shoulder surgery, in general. They found that meeting pre-operative expectations, functional improvement, improved general health status, being married, and being employed were significantly associated with post-operative satisfaction. 8 There is a growing body of evidence that pre-operative patient expectations, referred to as future-directed beliefs that focus on the incidence or no-incidence of a specific event of experience 9 and other psychosocial factors, could influence outcomes and satisfaction, in different pathologies.8,10–20 The value of pre-operative expectations has well been established in the rehabilitation of total knee and total hip arthroplasty10–15,21 low back pain, 16 as well as in rotator cuff repair.17,18 Most of these studies showed an association between greater pre-operative patient expectations or better fulfilment of pre-operative expectations and improved post-operative outcomes.11–13,17,18

The psychosocial nature of each individual patient, with patients’ expectations as an intrinsic part, could be of influence in the treatment plan and eventually impact the outcome of post-operative rehabilitation. Doctors and physiotherapists could have a huge impact and change imprecise beliefs about a problem or pathology, reduce anxiety, and thereby increase self-efficacy, and fighting depression. If physiotherapists could recognize these opportunities and develop the skills to change these psychosocial issues, both therapists and patients could benefit. 22

In this context, pre-operative expectations of patients undergoing shoulder surgery could also affect both the decision in therapy plan and how patients perceive their post-operative status. 23 Identifying the effect of these pre-operative expectations in SA is of great value in preparing the patient for surgery and improving satisfaction with outcomes.10–16,21 To improve patient satisfaction, straightforward and well-considered clinician-patient communication might help to set the expectations to the right terms. 21

Despite the literature considering pre-operative expectations and their effects on the post-operative outcome in other pathologies and its great importance, to our knowledge, no systematic reviews exist in the SA population. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review was to summarize the available evidence regarding the effects of pre-operative patient expectations on post-operative outcome such as: shoulder function, range of motion, shoulder pain, ADL, muscle strength, patient satisfaction, or QOL in patients with SA.

Materials and methods

This systematic review is conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Checklist (PRISMA) 24 and is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020140594).

Information sources and search

The search strategy was based on a Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, and Study design (PICOS) design. A systematic search was performed within PubMed, Web of Science (WOS), and Cochrane Trials Library to identify relevant articles concerning pre-operative expectations, attitudes, perceptions, or beliefs (I) and its effect on the post-operative outcome (O) in patients with a SA (P). Free-text words and MeSH-terms were both used to conduct an exhaustive search. The search strategy can be found in the Supplemental Appendix. The last search was carried out on 13 November 2023. The same search query was used for all databases and no limits were set. Reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews were checked for additional relevant articles.

Eligibility criteria

To be included in this systematic review, studies had to be original research assessing pre-operative expectations, attitudes, perceptions, or beliefs (I) and its influence on treatment outcome (O) in human adults of whom at least 80% had undergone a SA (P). At least one of the following treatment outcomes should have been measured: shoulder function, pain, muscle strength, range of motion, proprioception, satisfaction, QOL or ADL. Systematic reviews, meta-analysis, case reports and series, expert opinions, clinical protocols, letters to the editor, short communications, congress abstracts and proceedings, and books were excluded. Studies were also excluded if no full text was available or when it was written in another language than English, Dutch, French, and German. Studies published before 2000 were also excluded to avoid including studies with outdated implant types. The hierarchical order of the eligibility criteria was as follows: 1) language; 2) study design; 3) patients (P); 4) intervention (I); 5) outcome (O).

Study selection

All articles identified in this systematic search were imported in EndNote X9 and duplicates were removed. The retrieved articles were transferred into Rayyan 25 for two screening phases, on title and abstract. The results of the systematic search were screened for relevant publications by two independent, blinded researchers (ADM and AC). If title and abstract were unclear regarding eligibility criteria, the full text was retrieved, and screened together with the remaining articles. The second screening phase, based on full text, followed the same procedure. When consensus could not be reached, the last author (FS) was contacted for final decision.

Methodological quality

Risk of bias assessment of all included studies was performed using the Quality In Prognosis Studies (QUIPS) tool. 26 The tool consists of signaling questions to determine the risk of bias in studies concerning prognostic factors. The different domains being assessed are: 1) study participation; 2) study attrition; 3) prognostic factor measurement; 4) outcome measurement; 5) study confounding; 6) statistical analysis and reporting. Each domain is rated as low, moderate, or high risk of bias. The overall score is based on the risk of bias for each of those domains and based on the method in other tools.27,28 A study is considered to have a high risk of bias if at least one domain is at high risk of bias. A study is at moderate risk of bias if at least one domain is at moderate risk, but none is at high risk, and a study is at low risk of bias if all domains are at low risk.

Level of evidence of each study was determined based on the Evidence Based Richtlijn Ontwikkeling (EBRO) checklist. 29 Five different levels ranging from A1 (highest) to D (lowest) could be applied.

Finally, results were analyzed and existing evidence regarding the influence of pre-operative expectations on post-operative outcome was summarized. All effects were provided with a final level of conclusion, again, based on the EBRO method. 29 To facilitate readability of results, these levels of conclusion were converted. Outcomes were provided with a level 1 of conclusion if one A1 or at least two A2 articles agreed on the results, this was converted into strong evidence. Level 2 of conclusion was provided if one A2 or at least two B articles agreed on the results, which was named moderate evidence. Level 3 of conclusion was awarded if one B article (converted to preliminary evidence) or at least two C articles agreed on the results (converted to low evidence). An outcome was provided level 4 of conclusion if one C article agreed on the results (converted to preliminary evidence) or more than one higher level article did not support each other's findings (converted to conflicting evidence). 29

Methodological quality assessment was carried out by the same two independent reviewers (ADM and AC) and results were compared. In case of disagreement, the last author (FS) was contacted.

Data extraction

Two independent reviewers (ADM and AC) extracted the data using a standardized data-extraction file. Information regarding study design, characteristics of participants, inclusion and exclusion criteria, outcome measures, timing, pre-operative factors (expectations, attitudes, perceptions, or beliefs), and their effects were collected.

No meta-analysis was planned due to the heterogeneity of the outcome measures in the included studies. Only a qualitative analysis will be done.

Results

Selection of studies

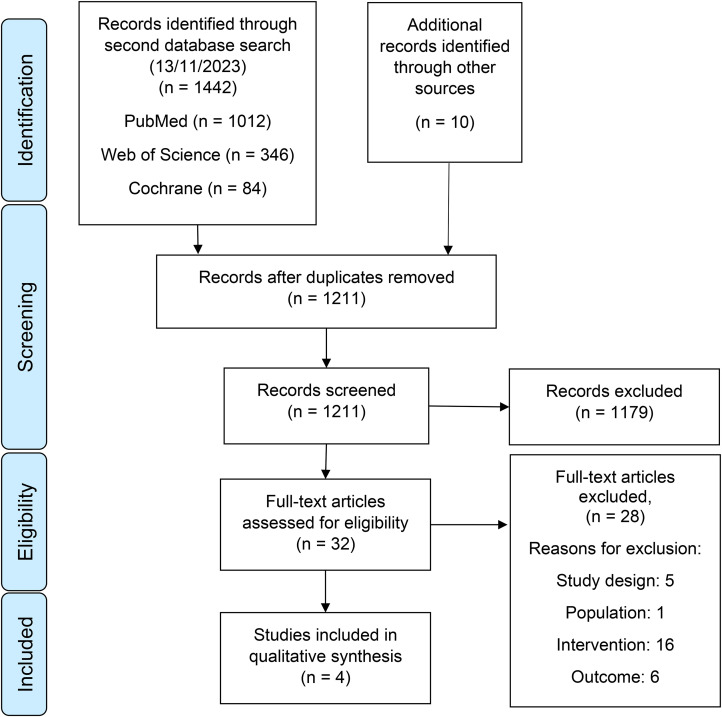

The selection process of this systematic review can be found in Figure 1. In the end, four articles were included in this systematic review, two of them were retrospective cohort studies,30,31 and two were prospective cohort studies.32,33 Characteristics of included studies are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of systematic literature review. FT: full text.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the studies investigating the effect of pre-operative expectations, attitudes, and beliefs on treatment outcome after shoulder arthroplasty.

| Participants | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Study design | Group composition and patient characteristics | Inclusion | Exclusion | Pre-op expectations | Outcome measures | Timing/follow up | Results |

| Lawrence et al. 2021 33 | Prospective cohort | ATSA N = 64 ♀ 22 (34%) ♂ 42 (66%) 65,7y (36,6y-86,3y) RTSA N = 64 ♀ 41 (64%) ♂ 23 (36%) 71,4y (51,1y-91,4y) |

Patients undergoing primary ATSA for a diagnosis of OA and RTSA for the diagnosis of CTA | Patients undergoing revision surgery, a history of prior shoulder arthroplasty, and other diagnoses, such as avascular necrosis, proximal humerus fracture, or inflammatory arthropathy | HSS-ES |

|

|

Greater expectations forability to exercise:

No association between pre-op expectations and any of the other improvement or outcome scores in patients with ATSA or RTSA |

| Rauck et al. 2018 30 | Retrospective cohort | RTSA N = 135 (137 RTSA's) ♀ 88 (65%) ♂ 47 (35%) 71,4y |

None reported | None reported | HSS-ES |

|

|

Greater number of “very important” expectations showed statistically significant

A greater number of “very important” expectations was not an independent predictor of ASES, SAS, or VAS scores |

| Styron et al. 2015 34 | Prospective cohort | Primary TSA N = 436 ♀ 194 (45%) ♂ 242 (55%) 66,6y |

Patients undergoing a primary unilateral TSA between January 2008 and December 2010 | Patients having another surgery within 3 m before or after the index shoulder arthroplasty procedure Patients not having completed a baseline questionnaire within 6 months before the index shoulder arthroplasty Patients not completing a single FU questionnaire post-operative |

Patients were asked the level of functional activity they expected to achieve after their TSA on an ordinal scale of 5 items: perform self-care, work outside the house, perform light exercise, perform heavy exercise, or participate in sports. Patients were asked on a scale of 1 to 10 to rate their level of confidence in their ability to attain their desired level of postoperative functionality. |

|

|

Patients’ confidence scores were significantly associated with the amount of impr in their post-op functionality:

|

| Swarup et al. 2017 31 | Retrospective cohort | ATSA N = 98 (67 included) ♀ 57 (58%) ♂ 41 (42%) 67,6y (30y-86y) |

|

None reported | HSS-ES |

|

|

Greater number of “very important” expectations):

Greater expectations for relieving daytime pain:

Greater number of “very important” expectations was an independent predictor of:

|

ATSA: Anatomic Total Shoulder; N: total; ♀: women; ♂: men; y: year; RTSA: reverse total shoulder arthroplasty; OA: osteoarthritis; CTA: cuff tear arthropathy; HSS-ES: Hospital Special Surgery Shoulder-Expectation Survey; ASES: American Shoulder and Elbow Score; SANE: Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation; SST: Simple Shoulder Test; VAS: Visual Analogue Scale; VR-12: Veteran RAND 12-item Health Survey; aROM; FF: forward flexion; pre-op: pre-operative; FU: follow-up; impr: improvement; SAS: Shoulder Activity Score; QOL: quality of life; SF-36: Short Form 36; SF-12: Short Form 12; TSA: Total Shoulder Arthroplasty; PSS: Penn Shoulder Score; m: month; PCS: Physical Component Score.

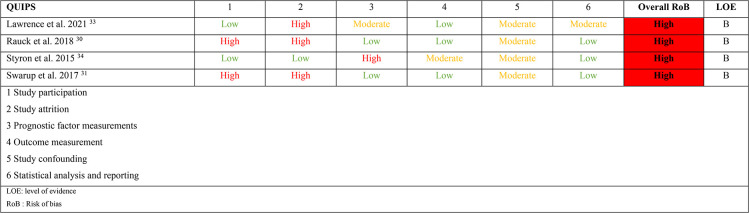

Methodological quality

The methodological quality of included studies is presented in Table 2. The overall risk of bias of the included studies was high in all four studies. This was mainly due to study attrition. The initial agreement between the 2 reviewers for risk of bias assessment was 83%, which reached full agreement after discussing the differences. The last author did not need to be consulted. The level of evidence was at level B for all studies. Levels of conclusion are presented in Table 3 and 4.

Table 2.

Risk of bias and level of evidence of the included studies.

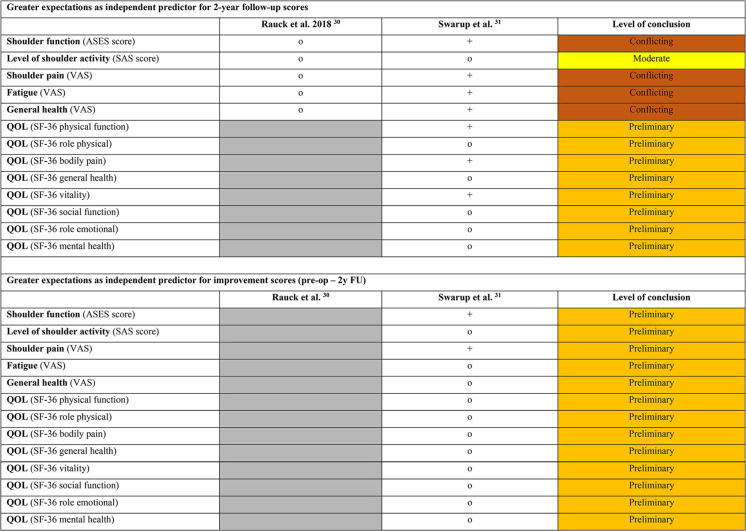

Table 3.

Associations between pre-operative patient expectations and better 2y follow-up outcome scores, pre-operative patient expectations and improvement outcome scores (pre-op – 2y fu), and their evidence.

Table 4.

Greater expectations as independent predictor for 2-year follow-up scores and improvement scores (pre-op – 2y fu), and their evidence.

Study population

All patients in the included studies had undergone a TSA (N = 797), either an ATSA (N = 162),31,33 or a RTSA (N = 199),30,33 and in 436 patients it was unclear whether they had undergone an ATSA or a RTSA. 34 The average age of the included patients was 68,5 years old, ranging from 30 to 91,4 years old. The number of women in the included studies varied from 57 to 194 (45–65%), while the number of men varied from 41 to 242 (35–56%). Different indications for surgery were seen. In patients with ATSA, the indication was primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis with failure of non-operative management.31–33 In patients with RTSA, indications were arthropathic cuff tears, degenerative arthritis, post-traumatic arthritis or glenohumeral osteoarthritis.30,32,33

Pre-operative expectations

Three of the four studies used the validated Hospital for Special Surgery's Shoulder Expectations Survey (HSS-ES) to assess pre-operative expectations.30,31,33 This survey includes 19 expectations related to the shoulder of the patient and the outcome after surgery. The main question is: “How important are these expectations in the treatment of your shoulder?”. Each expectation has five possible answers on an ordinal scale: “very important”, “somewhat important”, “a little important”, “I do not expect this”, and “this does not apply to me”. For each question, certain responses were extracted: the “very important” responses, were seen as a high level of expectation or greater expectations. For each patient the total number of questions marked as “very important” were summed.30,31,33 Greater expectations in general, were a greater number of “very important” responses. In other words, a patient with greater expectations is a patient who expects more of the post-operative outcome. All three of these studies also analyzed the separate expectation questions and their responses.30,31,33 At last, two of the three studies also analyzed the role of pre-operative patient expectations as an independent predictor for outcome measures.30,31

The fourth included study used a different method to measure patient's pre-operative expectations. Patients were asked the level of functional activity they expected to be able to perform after their SA on an ordinal scale of five items: perform self-care, work outside the house, perform light exercise, perform heavy exercise, or participate in sports. After choosing one functional activity, patients were asked to rate their level of confidence in their ability to attain their previously stated desired level of post-operative functionality on a scale from 0 (no confidence) to 10 (very confident). 34

Outcome measures

Outcome measures used in the included studies varied substantially. To measure shoulder function the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Score (ASES),30,31,33 which measures the functional limitations of the affected shoulder, the Simple Shoulder Test (SST) 33 for functional limitations of the effected shoulder, the Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE) 33 for functionality of the affected shoulder, and the Penn Shoulder Score (PSS) 34 which assesses patient self-reported levels of pain, function and satisfaction were used. Health related QOL was measured by the Short Form-36 (SF-36),30,31 the Short Form-12 (SF-12), 34 and the Veterans RAND 12-Item Health Survey (VR-12). 33 To measure level of shoulder activity (how often a patient engages in activity with the shoulder) the Shoulder Activity Scale (SAS)30,31 was used. Pain, fatigue, and general health were assessed through the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS).30,31,33 To measure satisfaction, satisfaction was first rated considering five domains (overall, pain, work, activities, QOL) with five possible answers: “very satisfied”, “somewhat satisfied”, “neither satisfied, nor dissatisfied”, “somewhat dissatisfied” and “very dissatisfied”. For analysis, these responses were dichotomized, “very satisfied” responses versus all other responses called “not very satisfied” responses. Secondly, three yes or no questions were asked: “Would you choose to undergo the surgery again?”, “Would you recommend the surgery to a friend?”, and “Do you wish you had undergone the surgery earlier?”31,33

Effects of pre-operative expectations on outcome

Greater pre-operative patient expectations, defined as a greater number of “very important” responses on the HSS-ES, showed some associations, which can be found, together with their evidence, in Table 3. Associations were awarded as + (positive association), o (no association), and – (negative association).

Moderate evidence was found for no association between greater pre-operative patient expectations or, a greater number of “very important” responses on the HSS-ES, and better 2-year follow-up scores, and improvement scores in patients with both ATSA and RTSA.30,31,33 Conflicting evidence was found for the association between greater pre-operative patient expectations and the 2-year follow-up score for quality-of-life general health, the improvement scores for quality-of-life physical function, quality of live role physical in patients with RTSA, and the improvement score for shoulder function in patients with ATSA. Where one study found a positive association,30,31 another study did not find any association.30,31 At last, preliminary evidence was found for no association between greater pre-operative patient expectations and the follow-up scores or improvement scores for different outcome measures.32,33

Considering the fourth study, which is awarded preliminary evidence, higher confidence in achieving physical activities postoperatively showed larger improvements in function and pain scores, measured with PSS. No significant associations were found between confidence and health related QOL. 34 However, this study did not directly assess patient's expectations except for asking the level of activity the patient hoped to achieve. This was weakly but significantly associated with the patient's confidence levels in the univariate model, but not in the multivariate model.

Moderate evidence was found for greater expectations or, a greater number of “very important” responses on the HSS-ES, not to be an independent predictor for level of shoulder activity.30,31 In patients with ATSA, greater pre-operative expectations, was an independent predictor for different outcome measures, such as: better outcome scores at 2-year follow-up for QOL physical function, bodily pain, and SF-36 vitality and greater improvements in shoulder function and shoulder pain, which was all rewarded with preliminary evidence. 31 Conflicting evidence exists for greater pre-operative expectations to be an independent predictor for shoulder function, shoulder pain, fatigue, and general health at 2-year follow-up.30,31 These predictors, with details, can be found in Table 4. A positive predictor was awarded +, a negative predictor was awarded –, and if greater expectations were found to be no predictor for a particular outcome measure it was awarded o.

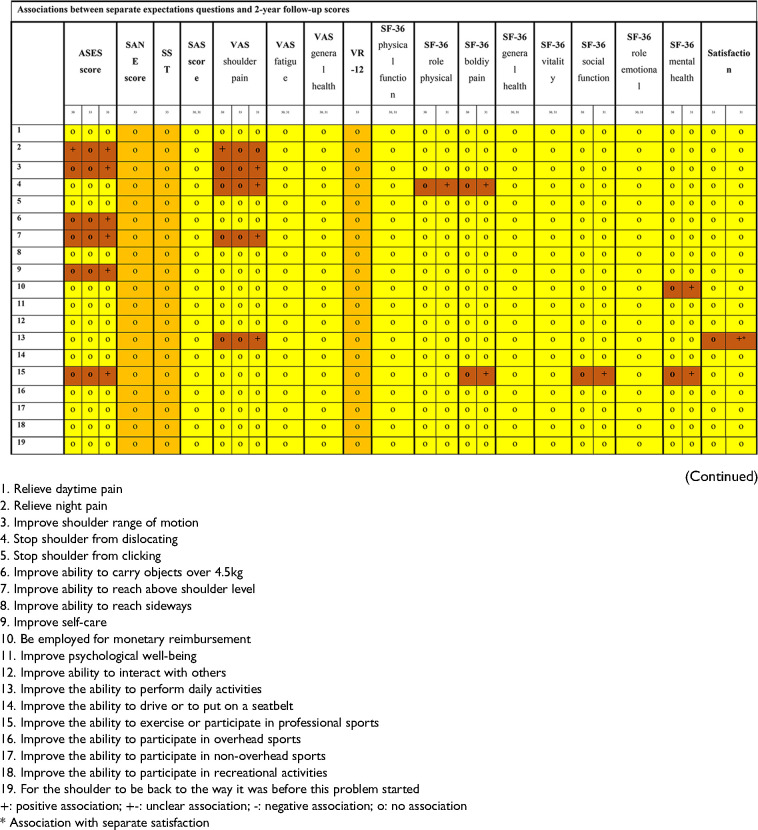

Considering the analysis of separate questions of the HSS-ES and their responses, different associations were found. A detailed overview of the evidence can be found in Table 5. Evidence for an association was awarded a + (positive association), o (no association), and – (negative association). Moderate evidence was found only for the lack of association between the separate questions and the two-year follow-up scores, and the improvement scores. Associations that were found were awarded only preliminary or conflicting evidence.

Table 5.

Associations between separate expectations questions and 2-year follow-up scores, and improvement scores.

Discussion

After screening almost 1000 studies for this systematic review, only four studies met the inclusion criteria. This demonstrates the high need for qualitative research regarding this topic.

In general, moderate evidence was found for only the absence of associations between pre-operative patient expectations and post-operative outcomes in patients with either an ATSA or a RTSA. A few studies showed preliminary evidence of improved outcomes in patients with greater expectations, or patients who expected more; however, some results were conflicting.30,31 The predictive character of pre-operative patient expectations and its influence on post-operative outcomes was analyzed in the included studies, which mainly yielded preliminary or conflicting evidence. Considering the separate expectation questions analyzed, only moderate evidence was found for the absence of associations. Separate expectations questions analyzed with a positive association were only awarded preliminary and conflicting evidence for their effect on post-operative outcomes. Finally, preliminary evidence was found regarding the effects of confidence on post-operative function. 34 Patients who were more confident in achieving physical activities postoperatively showed larger improvements in function and pain scores. The measurement method to measure patient confidence is not validated to our knowledge. This study also did not directly assess pre-operative patient expectations. They asked for the level of activity they hoped to achieve. These results, thus, should be interpreted with caution.

Different reasons can be given for the conflicting evidence in this systematic review. First, the studies that analyzed these associations included different types of SA. Different types of SA are associated with different indications and different functional outcomes. For example, RTSA has been shown to have good outcomes for pain relief,35,36 but due to the change in biomechanics of the shoulder, there might be a ceiling effect in improving the functional outcome scores, 30 which could be a reason for the conflicting evidence. When looking at the differences in pre-operative expectations between ATSA and RTSA in these included studies, greater pre-operative expectations were seen in patients with ATSA, and these patients expected better outcomes.30,31 Another possible reason for this conflicting evidence is that RTSA is typically used in the elderly,1,5,37 and these patients tend to have lower expectations regarding SA outcomes than younger patients.23,38 However, these findings cannot be generalized because the differences in pre-operative patients’ expectations were not part of the scope of this systematic review. The next possible reason for this conflicting evidence is the variability in measurement methods. Different methods are used to measure shoulder function, which makes generalizability difficult.30–33 Yet another possible reason for this conflicting evidence is the amount of missing data in the study of Rauck et al.; only 10 of 135 patients filled out the SF-36 form at baseline, and at the 2-year follow-up, only 59 SF-36 scores were available. 30 These results may thus overrate outcomes. Another note that should be made is the subjectivity of the term “greater expectations”. Included articles defined “greater expectations” as a higher number of questions rated “very important” in the HSS-ES. While, in these articles, this number of questions is not objectively defined. Thus, results need to be interpreted with caution.

The main reason for the preliminary evidence found in this systematic review is the lack of qualitative research regarding the effects of pre-operative patient expectations on post-operative outcomes. Different implant types and different research protocols were used, which makes it difficult to generalize findings. The number of included studies was low, and studies regarding this topic are lacking. This points out the great need for high-quality research concerning the pre-operative patient expectations in SA patients and the effects thereof. Future research should focus on high-quality research with validated research protocols. Measurement methods should be used in a standardized manner and confounding factors should be considered carefully.

When the literature found is compared to the literature that exists about the effects of pre-operative expectations in patients with hip and knee arthroplasties a few important notes can be made. The biggest difference is the amount of available evidence. Systematic reviews written about this topic in hip and knee arthroplasties included between eight and twenty-two studies, while we could only include four articles.15,39,40 This is in line with the amount of hip and knee arthroplasties performed annually, compared to the amount of shoulder arthroplasties. 2 When we look more into the included articles we also see a lot of heterogeneity in the studies about pre-operative expectations in patients with hip and knee arthroplasties. 15 It seems that standardized measurement methods and validated research protocols are also needed in research in hip and knee arthroplasties and the expectations of these patients.

This systematic review has multiple strengths. First, an extensive literature search was performed within three different databases. Additionally, the reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews within the topic were checked to ensure that no evidence was missed. Second, the screening of articles in two phases and the scoring of the methodology were performed by two independent reviewers to ensure that no evidence was missed, and the quality of the included studies was determined objectively. The level of evidence was rather low, and risk of bias of included studies was high, which reinforces the need for further research as previously stated. Additionally, data extraction was performed by two independent reviewers to guarantee that the data was extracted objectively and correctly.

Lastly, the primary aim of all included studies was to investigate the effects of pre-operative expectations or their predictive strength. This emphasis reinforces the importance and relevance of the results of this systematic review.

In conclusion, this systematic review demonstrates the urgent need for high-quality research to determine the effect of pre-operative expectations on the post-operative outcomes. Few eligible studies were found, and the levels of evidence were rather low, while the risk of bias was high. This review found mainly moderate evidence for the absence of associations between greater pre-operative expectations and better post-operative outcomes, and any associations that were found had conflicting or preliminary evidence. Informing patients about what can be expected can be of great importance. To confirm or reject the findings of this systematic review, future research should focus on high-quality research with validated research protocol.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sel-10.1177_17585732241282021 for Effects of pre-operative patient expectations on the outcome after total shoulder arthroplasty: A systematic review by Anke Claes, Annelien De Mesel, Olivier Verborgt and Filip Struyf in Shoulder & Elbow

Abbreviations

- SA

Shoulder Arthroplasty

- TSA

Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

- QOL

quality of life

- ADL

activities of daily living

- ATSA

Anatomic Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

- RTSA

Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Checklist

- PICOS

Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Study design

- WOS

Web of Science

- QUIPS

Quality in Prognosis Studies

- EBRO

Evidence Based Richtlijn Ontwikkeling

- HSS-ES

Hospital Special Shoulder Surgery Expectation Survey

- ASES

American Shoulder and Elbow Score

- SST

Simple Shoulder Test

- SANE

Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation

- PSS

Penn Shoulder Score

- SF-36

Short Form 36

- SF-12

Short Form 12

- VR-12

Veteran RAND 12-item Health Survey

- SAS

Shoulder Activity Score

- VAS

Visual Analogue ScoreNo funding received.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Anke Claes https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7874-2325

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. Annual Report 2018, https://aoanjrr.sahmri.com/annual-reports2018 . 2018.

- 2.Dutch Arthroplasty Register (LROI). LROI Annual Report 2020, https://magazine2020.lroi.nl/lroi-magazine-2020/cover (accessed 2021 August 2). 2020.

- 3.Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, et al. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93: 2249–2254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deore VT, Griffiths E, Monga P. Shoulder arthroplasty—Past, present and future. J Arthrosc Jt Surg 2018; 5: 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schairer WW, Nwachukwu BU, Lyman S, et al. National utilization of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 91–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Padegimas EM, Maltenfort M, Lazarus MD, et al. Future patient demand for shoulder arthroplasty by younger patients: national projections. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015; 473: 1860–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobs CA, Morris BJ, Sciascia AD, et al. Comparison of satisfied and dissatisfied patients 2 to 5 years after anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2016; 25: 1128–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swarup I, Henn CM, Gulotta LV, et al. Patient expectations and satisfaction in orthopaedic surgery: a review of the literature. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2019; 10: 755–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kube T, D'Astolfo L, Glombiewski JA, et al. Focusing on situation-specific expectations in major depression as basis for behavioural experiments - development of the depressive expectations scale. Psychol Psychother 2017; 90: 336–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cross M, Lapsley H, Barcenilla A, et al. Patient expectations of hip and knee joint replacement surgery and postoperative health status. Patient 2009; 2: 51–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyck BA, Zywiel MG, Mahomed A, et al. Associations between patient expectations of joint arthroplasty surgery and pre- and post-operative clinical status. Expert Rev Med Devices 2014; 11: 403–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gandhi R, Davey JR, Mahomed N. Patient expectations predict greater pain relief with joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2009; 24: 716–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Judge A, Cooper C, Arden NK, et al. Pre-operative expectation predicts 12-month post-operative outcome among patients undergoing primary total hip replacement in European orthopaedic centres. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2011; 19: 659–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahomed NN, Liang MH, Cook EF, et al. The importance of patient expectations in predicting functional outcomes after total joint arthroplasty. J Rheumatol 2002; 29: 1273–1279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haanstra TM, van den Berg T, Ostelo RW, et al. Systematic review: do patient expectations influence treatment outcomes in total knee and total hip arthroplasty? Health Qual Life Outcomes 2012; 10: 52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iles RA, Davidson M, Taylor NF, et al. Systematic review of the ability of recovery expectations to predict outcomes in non-chronic non-specific low back pain. J Occup Rehabil 2009; 19: 25–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henn RF, 3rd, Kang L, Tashjian RZ, et al. Patients’ preoperative expectations predict the outcome of rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007; 89: 1913–1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tashjian RZ, Bradley MP, Tocci S, et al. Factors influencing patient satisfaction after rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16: 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Puzzitiello RN, Nwachukwu BU, Agarwalla A, et al. Patient satisfaction after total shoulder arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2020; 43: e492–e497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vajapey SP, Cvetanovich GL, Bishop JY, et al. Psychosocial factors affecting outcomes after shoulder arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2020; 29: e175–e184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koenen P, Bäthis H, Schneider MM, et al. How do we face patients’ expectations in joint arthroplasty? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014; 134: 925–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barron CJ, Moffett JA, Potter M. Patient expectations of physiotherapy: definitions, concepts, and theories. Physiother Theory Pract 2007; 23: 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mancuso CA, Altchek DW, Craig EV, et al. Patients’ expectations of shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11: 541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Br Med J 2009; 339: b2535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev 2016; 5: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, et al. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158: 280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sterne JAC, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Br Med J 2016; 355: i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JP, Sterne JA, Savovic J, et al. A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomized trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; 10: 29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 29.CBO KvdG. Evidence-based Richtlijnontwikkeling. Handleiding voor werkgroepleden. november 2007. 2007.

- 30.Rauck RC, Swarup I, Chang B, et al. Effect of preoperative patient expectations on outcomes after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2018; 27: e323–e329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Swarup I, Henn CM, Nguyen JT, et al. Effect of pre-operative expectations on the outcomes following total shoulder arthroplasty. Bone Joint J 2017; 99: 1190–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Styron JF, Higuera CA, Strnad G, et al. Greater patient confidence yields greater functional outcomes after primary total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 1263–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawrence C, Lazarus M, Abboud J, et al. Prospective comparative study of preoperative expectations and postoperative outcomes in anatomic and reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Joints 2019; 7: 159–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Styron JF, Higuera CA, Strnad G, et al. Greater patient confidence yields greater functional outcomes after primary total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 1263–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello D, et al. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87: 1697–1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, et al. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004; 86: 388–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dutch Arthroplasty Register (LROI). LROI Annual Report 2019. 2019.

- 38.Henn RF, 3rd, Ghomrawi H, Rutledge JR, et al. Preoperative patient expectations of total shoulder arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011; 93: 2110–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Duivenvoorden T, Verburg H, Verhaar JA, et al. Patient expectations and satisfaction concerning total knee arthroplasty. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2017; 160: D534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hafkamp FJ, Gosens T, de Vries J, et al. Do dissatisfied patients have unrealistic expectations? A systematic review and best-evidence synthesis in knee and hip arthroplasty patients. EFORT Open Rev 2020; 5: 226–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-sel-10.1177_17585732241282021 for Effects of pre-operative patient expectations on the outcome after total shoulder arthroplasty: A systematic review by Anke Claes, Annelien De Mesel, Olivier Verborgt and Filip Struyf in Shoulder & Elbow